Migraine herbal supplements

Dietary Supplements for Headaches: What the Science Says

Skip to main contentJune 2021

Clinical Guidelines, Scientific Literature, Info for Patients:

Dietary Supplements for Headaches

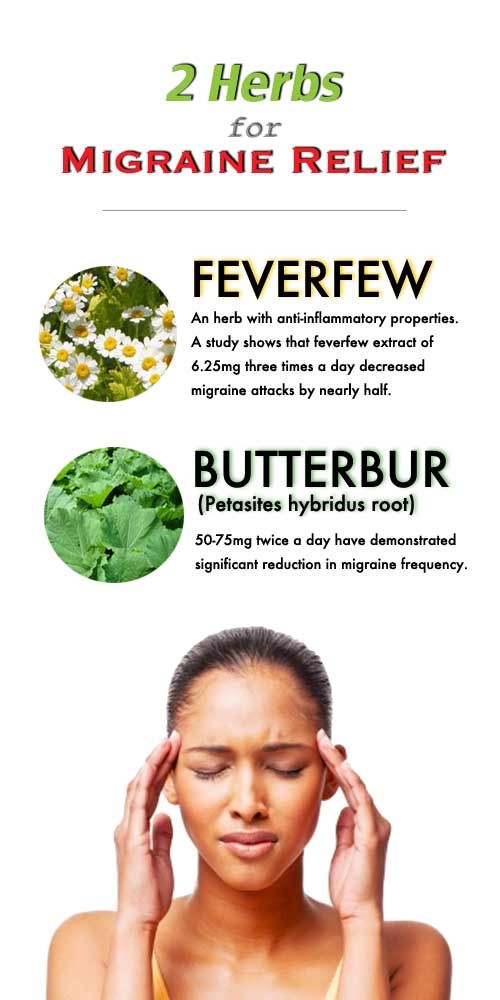

Several dietary supplements, including riboflavin, coenzyme Q10, and the herbs butterbur and feverfew, have been studied for headaches and migraine, with some promising results in preliminary studies. However, more rigorous studies are needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn.

Butterbur

Butterbur appears to help reduce the frequency of migraines in adults and children; however, there are serious safety concerns.

What Does the Research Show?

- In 2012, the American Academy of Neurology recommended its use for preventing migraines. However, the Academy stopped recommending it in 2015 because of serious concerns about possible liver toxicity.

Safety

- Some butterbur products contain pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs), which can damage the liver, lungs, and blood circulation, and possibly cause cancer.

Only butterbur products that have been processed to remove PAs and are labeled or certified as PA-free should be considered for use.

- Several studies, including a few studies of children and adolescents, have reported that PA-free butterbur products seem to be safe when taken by mouth in recommended doses for up to 16 weeks. However, some products claiming to be PA-free may not in fact be. A 2019 review found that recent cases of clinically apparent liver injury have been reported with use of several commercial preparations of butterbur, suspected to be due to residual PA contamination.

- Butterbur products with PAs should not be used during pregnancy or while breastfeeding because they may cause birth defects or liver damage. Little is known about whether it’s safe to use PA-free butterbur during pregnancy or while breastfeeding.

- PA-free butterbur is generally well tolerated but can cause side effects such as belching, headache, itchy eyes, diarrhea, breathing difficulties, fatigue, upset stomach, and drowsiness.

- Butterbur may cause allergic reactions in people who are sensitive to plants such as ragweed, chrysanthemums, marigolds, and daisies.

Coenzyme Q10

There is some limited evidence that coenzyme Q10 may help reduce the duration and frequency of migraines.

What Does the Research Show?

- A 2019 meta-analysis of five studies involving 346 patients (120 pediatric and 226 adult participants) found that coenzyme Q10 was comparable with placebo with respect to migraine attacks per month and migraine severity per day. However, coenzyme Q10 was shown to be more effective than placebo in reducing the number of migraine days per month and migraine duration.

- Another 2019 meta-analysis of 6 studies involving a total of 371 participants found that coenzyme Q10 supplementation appeared to have beneficial effects in reducing duration and frequency of migraine attack.

Safety

- No serious side effects of CoQ10 have been reported.

Mild side effects such as insomnia or digestive upsets may occur.

Mild side effects such as insomnia or digestive upsets may occur. - Coenzyme Q10 may interact with anticoagulants as well as insulin, and it may not be compatible with some types of chemotherapeutic agents.

Feverfew

Some research suggests that feverfew may help prevent migraine headaches, but results have been mixed. Some studies have suggested that feverfew may reduce migraine headache frequency, as well as some symptoms, such as pain, nausea/vomiting, and light sensitivity.

What Does the Research Show?

- A 2020 Cochrane review (an update to a previous Cochrane review, which added one larger rigorous study) of 6 studies involving 561 participants found a difference in effect between feverfew and placebo of 0.6 migraine attacks per month. However, the reviewers noted that this constitutes low quality evidence, which needs to be confirmed in larger rigorous trials with stable feverfew extracts and clearly defined migraine populations before firm conclusions can be drawn.

- A 2019 review on migraine headache prophylaxis found that feverfew is probably effective.

Safety

- No serious side effects have been reported from feverfew use. Side effects can include nausea, digestive problems, and bloating; if the fresh leaves are chewed, sores and irritation of the mouth may occur.

- People who are sensitive to ragweed and related plants may experience allergic reactions to feverfew.

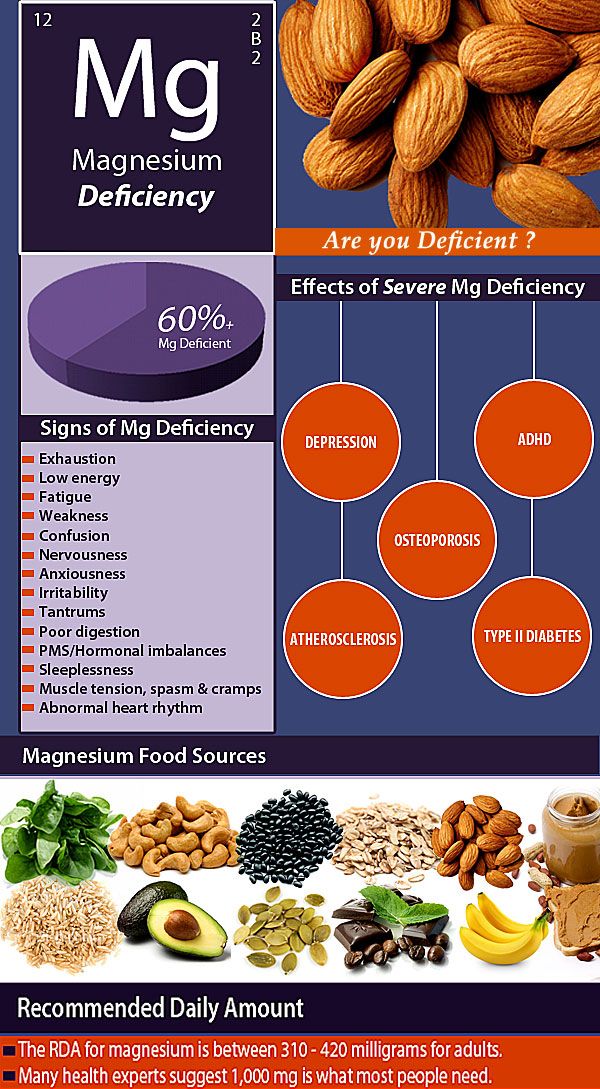

Magnesium

Research on the use of magnesium supplements to prevent or reduce symptoms of migraine headaches is limited. There is some evidence that magnesium supplementation may provide modest reductions in the frequency of migraines.

What Does the Research Show?

- A 2018 systematic review of five studies found Grade C (possibly effective) evidence for prevention of migraine with magnesium. However, a 2021 review concluded that even if the preliminary results are very promising, more rigorous studies have to be designed to confirm the efficacy of magnesium for headache.

- A 2009 review found that three of four small, short-term, placebo-controlled trials showed modest reductions in the frequency of migraines in patients given up to 600 mg/day magnesium. Because the typical dose of magnesium used for migraine prevention exceeds the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL), this treatment should be used only under the direction and supervision of a healthcare provider.

Safety

- High doses of magnesium from dietary supplements or medications often result in diarrhea that can be accompanied by nausea and abdominal cramping. Forms of magnesium most commonly reported to cause diarrhea include magnesium carbonate, chloride, gluconate, and oxide.

- Very large doses of magnesium-containing laxatives and antacids (typically providing more than 5,000 mg/day of magnesium) have been associated with magnesium toxicity, including fatal hypermagnesemia. Symptoms of magnesium toxicity, which usually develop after serum concentrations exceed 1.

74–2.61 mmol/L, can include hypotension, nausea, vomiting, facial flushing, retention of urine, ileus, depression, and lethargy before progressing to muscle weakness, difficulty breathing, extreme hypotension, irregular heartbeat, and cardiac arrest. The risk of magnesium toxicity increases with impaired renal function or kidney failure because the ability to remove excess magnesium is reduced or lost.

74–2.61 mmol/L, can include hypotension, nausea, vomiting, facial flushing, retention of urine, ileus, depression, and lethargy before progressing to muscle weakness, difficulty breathing, extreme hypotension, irregular heartbeat, and cardiac arrest. The risk of magnesium toxicity increases with impaired renal function or kidney failure because the ability to remove excess magnesium is reduced or lost.

Riboflavin

Some, but not all, of the few small studies conducted to date have found evidence of a beneficial effect of riboflavin supplements on migraine headaches in adults and children.

What Does the Research Show?

- A 1998 randomized controlled trial of 55 participants with migraines compared treatment with 400 mg riboflavin daily with placebo for 12 weeks. The results, 4 months after the trial, showed that the reduction in migraine attacks per month was greater for patients treated with riboflavin (56 percent) compared to the placebo group (19 percent).

- A 2020 review concluded that overall, studies to date report that riboflavin has similar efficacy to valproate for migraine prophylaxis, but has a more tolerable side effect profile.

Safety

- Adverse effects from high riboflavin intakes from foods or supplements (400 mg/day for at least 3 months) have not been reported. A 2021 review found that in all of the studies included in the review, riboflavin was well tolerated without major side effects or safety concerns.

References

- Barmherzig R, Rajapakse T. Nutraceuticals and behavioral therapy for headache. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 2021;21(7):33.

- Butterbur. LiverTox: clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012–. Accessed at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31643176/ on June 28, 2021.

- Grazzie L, Toppo C, D’Amico D, et al. Non-pharmacological approaches to headaches: non-invasive neuromodulation, nutraceuticals, and behavioral approaches.

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(4):1503.

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(4):1503. - Ha H, Gonzalez A. Migraine headache prophylaxis. American Family Physician. 2019;99(1):17-24.

- Sazali S, Badrin S, Norhayati MN, et al. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation for prophylaxis in adult patients with migraine—a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e039358.

- Schoenen J, Jacquy J, Lenaerts M. Effectiveness of high-dose riboflavin in migraine prophylaxis. A randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 1998;50(2):466-470.

- Stubberud A, Varkey E, McCrory DC, et al. Biofeedback as prophylaxis for pediatric migraine: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20160675.

- Sun-Edelstein C, Mauskop A. Role of magnesium in the pathogenesis and treatment of migraine. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2009;9(3):369-379.

- Thompson AP, Thompson DS, Jou H, et al. Relaxation training for management of paediatric headache: a rapid review.

Paediatrics & Child Health. 2019;24(2):103-114.

Paediatrics & Child Health. 2019;24(2):103-114. - Urits I, Gress K, Charipova K, et al. Pharmacological options for the treatment of chronic migraine pain. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Anaesthesiology. 2020;34(3):383-407.

- von Luckner A, Riederer F. Magnesium in migraine prophylaxis—is there an evidence-based rationale? A systematic review. Headache. 2018;58(2):199-209.

- Wider B, Pittler MH, Ernst E. Feverfew for preventing migraine. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;4(4):CD002286.

- Youssef PE, Mack KJ. Episodic and chronic migraine in children. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2020;62(1):34-41.

- Zeng Z, Li Y, Lu S, et al. Efficacy of CoQ10 as supplementation for migraine: a meta-analysis. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2019;139(3):284-293.

NCCIH Clinical Digest is a service of the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, NIH, DHHS. NCCIH Clinical Digest, a monthly e-newsletter, offers evidence-based information on complementary health approaches, including scientific literature searches, summaries of NCCIH-funded research, fact sheets for patients, and more.

NCCIH Clinical Digest, a monthly e-newsletter, offers evidence-based information on complementary health approaches, including scientific literature searches, summaries of NCCIH-funded research, fact sheets for patients, and more.

The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health is dedicated to exploring complementary health products and practices in the context of rigorous science, training complementary health researchers, and disseminating authoritative information to the public and professionals. For additional information, call NCCIH’s Clearinghouse toll-free at 1-888-644-6226, or visit the NCCIH website at nccih.nih.gov. NCCIH is 1 of 27 institutes and centers at the National Institutes of Health, the Federal focal point for medical research in the United States.

Copyright

Content is in the public domain and may be reprinted, except if marked as copyrighted (©). Please credit the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health as the source. All copyrighted material is the property of its respective owners and may not be reprinted without their permission.

All copyrighted material is the property of its respective owners and may not be reprinted without their permission.

The Efficacy of Herbal Supplements and Nutraceuticals for Prevention of Migraine: Can They Help?

Cureus. 2021 May; 13(5): e14868.

Published online 2021 May 6. doi: 10.7759/cureus.14868

Monitoring Editor: Alexander Muacevic and John R Adler

,1,1,2,2,3,4,5,6 and 7

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Migraine is a common neurological disorder associated with or without aura. Although the pathophysiology of migraine is not very well understood, pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress biomarkers are found to be increased in migraine. Multiple studies have been done to see if alternative medicine such as herbal supplements and nutraceuticals are effective in the prevention and treatment of migraine headaches. This review aimed to evaluate the effect of supplements like coenzyme Q10, riboflavin (vitamin B2), feverfew, and magnesium on the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks.

This review aimed to evaluate the effect of supplements like coenzyme Q10, riboflavin (vitamin B2), feverfew, and magnesium on the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks.

We performed a thorough literature search using mainly PubMed. We included studies published in the last 10 years, those conducted among adult human participants 18-65 years of age, and those published in the English language. Based on the articles selected for the final review, we concluded that herbal supplements and nutraceuticals help reduce the frequency of migraine headaches; however, mixed results were seen regarding the severity and duration of headaches. Moreover, there were no concerning side effects with these supplements. Therefore, physicians can suggest herbal supplements to patients who experience adverse effects from pharmaceutical drugs and desire a more natural treatment.

Keywords: migraine, headache, nutraceuticals, antioxidants, coenzyme q10, herbal supplements, prevention, riboflavin

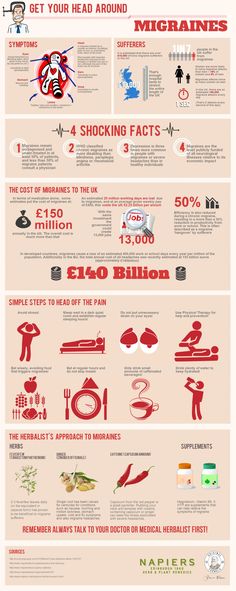

Migraine is characterized by moderate-to-severe episodic, throbbing, unilateral headaches usually accompanied by nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia [1]. According to the Global Burden of Disease report from the World Health Organization, it is the third most prevalent and the sixth most debilitating disease globally. Migraine is three times more common in females than in males with a worldwide prevalence of 14.7% [2]. Overall, 2% of the world’s population and, on average, one in seven Americans suffer from migraines [3,4].

According to the Global Burden of Disease report from the World Health Organization, it is the third most prevalent and the sixth most debilitating disease globally. Migraine is three times more common in females than in males with a worldwide prevalence of 14.7% [2]. Overall, 2% of the world’s population and, on average, one in seven Americans suffer from migraines [3,4].

The pathophysiology of migraine is unclear. Studies with phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P-MRS) show altered energy metabolism in the brain. These abnormalities in energy metabolism seem to have a genetic component and a neurovascular component. Migraine is associated with a mutation in genes coding for metabolic enzymes in both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA [5-7]. The neuronal and vascular dysfunction observed can be explained by impaired oxygen metabolism resulting from mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation resulting in changes in vascular tone [8,9]. Migraine is associated with other disorders such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, asthma, epilepsy, allergies, and sleep disorders [10]. It is usually triggered by fasting, skipping meals, stress, and lack of sleep [11,12].

It is usually triggered by fasting, skipping meals, stress, and lack of sleep [11,12].

Migraine is a chronic debilitating condition impacting daily life. Proper treatment and prevention can reduce the burden on healthcare and improve the quality of life of patients. Acute attacks are treated with analgesics or triptans. Drugs used for prophylaxis include anti-depressants (amitriptyline), anti-epileptics (topiramate, valproic acid), beta-blockers (propranolol), and calcium-channel blockers.

Recently, the use of herbal supplements and nutraceuticals such as coenzyme Q10, vitamin B2 (riboflavin), feverfew, and magnesium seem to be gaining popularity for the prevention of migraine. One of the reasons for their rising popularity is fewer side effects in comparison to pharmacological drug therapy. With this review article, we intend to explore the effectiveness of nutraceuticals and herbal supplements for the prevention of migraine attacks. We expect that this article will help guide physicians to decide which preventive treatment suit a patient better and thus help with future migraine attacks.

We performed a thorough literature search using PubMed to identify relevant studies. Studies published in the last 10 years, performed among human adult populations 18-65 years of age, and published in the English language were included. The search was done using keywords “migraine,” “nutraceuticals,” “supplements,” “Coenzyme Q10 ubiquinone,” and “prevention and control.”

The initial search yielded 106 articles, but after careful screening, applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, and excluding duplicate articles, 36 were shortlisted for abstract and full-text review. These included randomized controlled trials, observational studies, cohort studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analysis. Animal studies, case reports, and studies on pediatric and adolescent populations were excluded.

A total of 36 studies selected for the final review included two systematic reviews with meta-analysis, four randomized placebo-controlled double-blinded trials, three open-label pilot studies, one observational study, one cohort study, and review articles. Table presents the studies and their findings.

Table presents the studies and their findings.

Table 1

Effect of nutraceuticals on migraine headache.

TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; CGRP: calcitonin gene-related peptide; IL-6: interleukin-6; IL-10: interleukin-10; HIT-6: headache impact test; HDR: headache diary results

| Author/Year | Type of study | No. of patients | Purpose of study | Conclusion/Result |

| Dahri et al. 2018 [13] | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial | 52 | Effect of coenzyme Q10 on the clinical features of migraine and inflammatory markers | Significant reduction in TNF-α and CGRP, no significant difference in serum IL-6 and IL-10 levels |

Gaul et al. 2015 [14] 2015 [14] | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial | 130 | Effect of coenzyme Q10, riboflavin, and magnesium on the clinical features of migraine | Significant reduction in the intensity of migraine pain (p = 0.03) and score of the HIT-6 questionnaire (p = 0.01) |

| Shoeibi et al. 2016 [15] | Open-label parallel add-on, controlled trial | 80 | Effect of coenzyme Q10 in the prevention of migraine | Significant reduction in the frequency and intensity of migraine (p < 0.001) |

| Guilbot et al. 2017 [16] | Prospective observational | 132 | Effect of coenzyme Q10, magnesium, and feverfew in the prevention of migraine | Significant reduction in the frequency of migraine attacks (1. 3 days ±1.5 vs. 4.9 days ±2.6; p < 0.0001) 3 days ±1.5 vs. 4.9 days ±2.6; p < 0.0001) |

| Parohan et al. 2019 [17] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 221 | Effect of coenzyme Q10 in the prevention of migraine | Significant reduction in the frequency of migraine attacks (p < 0.0001), no significant reduction in severity and duration |

| Hajihashemi et al. 2019 [18] | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial | 56 | Effect of coenzyme Q10 and L-carnitine supplementation in the prevention of migraine | Significant reduction in serum lactate level (p < 0.0001), frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks (p < 0.0001) |

Volta et al. 2015 [19] 2015 [19] | Pilot study | 40 | Effect of coenzyme Q10 on episodic migraine without aura | Reduction in both frequency and intensity were seen in 25 patients, reduction in intensity but not in frequency in 10 patients, and no reduction in either in 5 patients |

| Sazali et al. 2021 [20] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 371 | Effect of coenzyme Q10 in the prevention of migraine | Significant reduction in the frequency and duration of migraine attacks (p < 0.0001), no significant reduction in severity |

| Parohan et al. 2019 [21] | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial | 100 | Effect of nano-curcumin and coenzyme Q10 supplementation in the prevention of migraine | Significant reduction in the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks and HDR (for all p < 0. 001) 001) |

| Vikelis et al. 2020 [22] | Pilot single-arm open-label | 113 | Effect of coenzyme Q10, riboflavin, magnesium, feverfew, and panniculata on the clinical features of migraine | Significant reduction in frequency, days with peak intensity headache, and HIT-6 scores (p < 0.001) |

| Pucci et al. 2015 [23] | Cohort | 20 | Effect of coenzyme Q10 in the prevention of migraine | Significant reduction in the frequency of migraine attacks |

Open in a separate window

Discussion

Migraine is considered to occur due to disturbances in brain homeostasis. The pathophysiology of migraine is unclear but seems to include a genetic component and a neurovascular component. Mutations in chromosome 19 are seen to be linked with familial migraine. Mutations involving Cav2.1 (P/Q)-type voltage-gated calcium channel CACNA1A gene are seen in about 50% cases of familial migraine [24]. One consequence of this mutation may be increased glutamate release. Mutations in the ATP1A2 gene have been identified to be responsible for about 20% of familial cases. ATP1A2 gene codes for a Na+/K+ ATPase. Mutation in this gene leads to decreased activity of astrocytic glutamate transporters and eventually build-up of synaptic glutamate. The increased glutamate seems to cause migraine headaches [25]. Figure shows the various triggers and pathophysiology of migraine headache.

Mutations in chromosome 19 are seen to be linked with familial migraine. Mutations involving Cav2.1 (P/Q)-type voltage-gated calcium channel CACNA1A gene are seen in about 50% cases of familial migraine [24]. One consequence of this mutation may be increased glutamate release. Mutations in the ATP1A2 gene have been identified to be responsible for about 20% of familial cases. ATP1A2 gene codes for a Na+/K+ ATPase. Mutation in this gene leads to decreased activity of astrocytic glutamate transporters and eventually build-up of synaptic glutamate. The increased glutamate seems to cause migraine headaches [25]. Figure shows the various triggers and pathophysiology of migraine headache.

Figure 1

Open in a separate window

Pathophysiology of migraine headache.

CGRP: calcitonin gene-related peptide

The occurrence of migraine is associated with cortical hyperactivity. The trigeminal ganglion is hypothesized to be involved in this hyperactivity [26]. Activation of trigeminal sensory nerve fibers, in turn, causes brainstem activation and induces the release of vasoactive peptides such as substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). This causes platelet and endothelial activation and, consequently, an increase in nitric oxide synthesis, vasodilation, leakage of blood vessels, and degranulation of mast cells [27]. This further activates sensory trigeminal fibers, increasing the release of substance P and CGRP, and transmits pain impulses throughout the brain [28].

Activation of trigeminal sensory nerve fibers, in turn, causes brainstem activation and induces the release of vasoactive peptides such as substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). This causes platelet and endothelial activation and, consequently, an increase in nitric oxide synthesis, vasodilation, leakage of blood vessels, and degranulation of mast cells [27]. This further activates sensory trigeminal fibers, increasing the release of substance P and CGRP, and transmits pain impulses throughout the brain [28].

Migraine with aura is associated with sensory, visual, or motor disturbances. These include increased sensitivity to light or sound, zig-zag flashes of light, and numbness or tingling in one hand or face. It is seen in about 30% of patients. Aura is considered to occur due to the slow wave of depolarization spreading across the cortex. This leads to stimulation of the trigeminovascular system, cerebral vessels nociceptors, and regions of the brain responsible for triggering pain and other neurological symptoms [29].

Studies with 31P-MRS have shown altered energy metabolism in the brain during acute migraine attacks. Hence, migraine can be triggered by fasting, physical exertion, excess sleep or sleep deprivation, intense aromas, or photosensitivity, which cause impaired oxygen metabolism due to mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation [8,9]. Several oxidative stress biomarkers are found to have increased plasma levels in patients with migraine. Table presents studies showing the association of migraine with inflammation and oxidative stress.

Table 2

Association of migraine with inflammation and oxidative stress.

TAS: total antioxidant status; TOS, total oxidant status; OSI: oxidative stress index; 8-OHdG: 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine; MDA: malondialdehyde; UTS2R: urotensin 2 receptor; CAT: catalase; WHM: white matter hyperintensities

| Author | No. of patients of patients | Migraine type | Results |

| Alp et al. [30] | 75 | Without aura | Decrease in TAS; increase in TOS; increase in OSI during the attack-free period |

| Geyik et al. [31] | 50 | With and without aura | No differences in TOS, TAS, and OSI in migraine patients with and without aura. Increase in 8-OHdG in migraine patients without aura versus with aura |

| Yigit et al. [32] | 40 | Without aura | Increase in lymphocyte DNA damage. Elevated values of TOS, OSI, and MDA and decreased value of TAS in migraineurs. Decreased plasma UTS2R in migraineurs. Decreased CAT activity in migraineurs Decreased CAT activity in migraineurs |

| Aytaç et al. [33] | 32 (18 with WHM and 14 without WHM-type lesions) | With and without WHM | Decreased CAT activity and increased MDA level in migraine patients with WHM-type lesions versus without WHM-type lesions |

| Tozzi-Ciancarelli et al. [34] | 23 | With aura | Increase in concentration of substances reacting with thio-barbituric acid during attack-free periods |

Open in a separate window

Due to their antioxidant properties and involvement in the mitochondrial electron transport chain, many nutraceuticals and herbal supplements such as coenzyme Q10, vitamin B2 (riboflavin), magnesium, alpha-lipoic acid, vitamin C, curcumin, and feverfew are considered for prophylaxis of migraine.

Coenzyme Q10, or ubiquinone, is a natural lipophilic substance needed for all cellular processes requiring energy. It acts as the complex III component of the electron transport chain and freely moves throughout the inner mitochondrial membrane transferring electrons from complex I and complex II (NADH dehydrogenase and succinate-Q-reductase, respectively) to cytochrome C. Coenzyme Q10 has been hypothesized to be useful in migraine prevention because of its vital role in sustaining mitochondrial energy stores [35]. In addition to its actions as an electron carrier, it also exerts an anti-inflammatory effect via nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathway inhibition preventing excessive reactive oxygen species production and inhibiting lipid membrane peroxidation and nucleic acid oxidation [35,36]. This helps with the inflammatory component of migraine. Recently, it is seen that coenzyme Q10 administered to migraine patients results in a decrease of CGRP, which is an important vasoactive peptide involved in the pathogenesis of migraine [13].

Curcumin has also been studied for the treatment of migraine. It is a lipophilic substance and acts as an anti-oxidant. It decreases the production of reactive oxygen species and inflammatory mediators such as interleukins (IL-1, IL-6) and cyclooxygenase [21].

Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) is a precursor for flavin-mononucleotide and flavin adenine-dinucleotide involved in the electron transport chain in the mitochondrial membrane. It is considered useful in migraine prevention due to its role in maintaining the energy stores of the body.

Magnesium (Mg) is involved in various biological processes. It acts as a cofactor for ATP-synthase which is involved in the production of ATP. Furthermore, it also regulates neuronal excitability and plays an important role in the regulation of vascular tone [37].

Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium) is also thought to be helpful in migraine [38,39]. Since ancient days, it has been used for pain, inflammation, nausea, and vomiting [40]. It is largely found in South America. Its main active component is parthenolide which inhibits aldose reductase activity and causes relaxation of vascular smooth muscle. It also exhibits anti-inflammatory effects [41,42], all of which contribute to its anti-migraine effects.

It is largely found in South America. Its main active component is parthenolide which inhibits aldose reductase activity and causes relaxation of vascular smooth muscle. It also exhibits anti-inflammatory effects [41,42], all of which contribute to its anti-migraine effects.

The most common side-effects of magnesium and feverfew are limited to the gastrointestinal system and include nausea, diarrhea, appetite suppression, heartburn, and epigastric discomfort with an incidence of less than 1% [43,44].

Guilbot et al. conducted a prospective observational study on 132 adults, mainly women (91.2%), in 2017 on the effect of a combination of coenzyme Q10, feverfew, and magnesium on the prevention of migraine. Supplementation significantly reduced the frequency of migraine attacks by the third month without any significant reduction in intensity. Overall, 75% of patients showed a reduction of at least 50% in the number of days with migraine headache per month [16].

Another study conducted by Gaul et al. in 2015 on the effect of coenzyme Q10, riboflavin, and magnesium supplementation on the clinical features of migraine included 130 adult migraineurs (age 18-65 years) with more than three migraine attacks per month. Patients were randomized in the treatment group and placebo group in a double-blinded manner and followed for three months. The frequency of headaches was reduced in the treatment group. The intensity of headache was also significantly reduced in the treatment group (p = 0.03). The sum score of the HIT-6 (headache impact test) questionnaire was reduced in the treatment group [14].

in 2015 on the effect of coenzyme Q10, riboflavin, and magnesium supplementation on the clinical features of migraine included 130 adult migraineurs (age 18-65 years) with more than three migraine attacks per month. Patients were randomized in the treatment group and placebo group in a double-blinded manner and followed for three months. The frequency of headaches was reduced in the treatment group. The intensity of headache was also significantly reduced in the treatment group (p = 0.03). The sum score of the HIT-6 (headache impact test) questionnaire was reduced in the treatment group [14].

Dahri et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 2018 among 45 women aged 18-50 years to assess the effect of coenzyme Q10 on the clinical features and inflammatory markers of migraine. The treatment group received 400 mg/day coenzyme Q10 for three months. Significant reduction in CGRP and TNF-α levels was seen (p = 0.011 and p = 0.044, respectively), but no significant difference in serum IL-6 and IL-10 was reported. A significant increase in coenzyme Q10 level (P < 0.001) and reduction in the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks was reported in the treatment group [13].

A significant increase in coenzyme Q10 level (P < 0.001) and reduction in the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks was reported in the treatment group [13].

Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the effect of coenzyme Q10 in the prevention of migraine included 592 patients. Both studies concluded a significant reduction in the frequency of migraine attacks (p < 0.0001) but no significant reduction in severity [17,20].

A cohort study among 20 patients, aged 22-49 years, with a male/female ratio of 1:5 by Pucci et al. showed a significant reduction in the frequency of migraine attacks on supplementation of coenzyme Q10 [23].

Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials including 156 patients showed a significant reduction in the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks (p < 0.001) when coenzyme Q10 was supplemented with other supplements such as L-carnitine and nano-curcumin [18,21].

Shoeibi et al. conducted an open-label, parallel, add-on, controlled trial on the effect of coenzyme Q10 in the prevention of migraine. A total of 80 patients were allocated to receiving only their current preventive drugs or their current preventive drugs plus 100 mg coenzyme Q10 daily for three months. A significant reduction was evident in the frequency (1.6 vs. 0.5; p < 0.001) and severity of headaches (2.3 vs. 0.6; p < 0.001) among coenzyme Q10 and control groups [15]. Other pilot studies also showed a reduction in the frequency of migraine attacks with coenzyme Q10 supplementation [19,22].

A total of 80 patients were allocated to receiving only their current preventive drugs or their current preventive drugs plus 100 mg coenzyme Q10 daily for three months. A significant reduction was evident in the frequency (1.6 vs. 0.5; p < 0.001) and severity of headaches (2.3 vs. 0.6; p < 0.001) among coenzyme Q10 and control groups [15]. Other pilot studies also showed a reduction in the frequency of migraine attacks with coenzyme Q10 supplementation [19,22].

Limitations

We did not include any animal studies, case reports, and studies on the pediatric and adolescent populations. Moreover, we excluded studies published in other than the English language which may have impacted the study findings.

Studies discussed in this review confirm the involvement of oxidative stress in migraine, and therefore, antioxidants seem to be helpful in its prevention. Based on our research, several studies showed that vitamins and minerals including coenzyme Q10, magnesium, riboflavin, and feverfew reduced the number of days of migraine attacks in patients. Few studies also showed a decrease in the intensity and duration of migraine headaches. However, more research is needed to conclude the effects of herbal supplements on the prevention of migraine headaches. Because many migraine triggers are our day-to-day activities, physicians should educate their patients about lifestyle modification and suggest herbal supplements, vitamins, and minerals to patients who experience side effects from pharmaceutical drugs and desire a more natural treatment.

Few studies also showed a decrease in the intensity and duration of migraine headaches. However, more research is needed to conclude the effects of herbal supplements on the prevention of migraine headaches. Because many migraine triggers are our day-to-day activities, physicians should educate their patients about lifestyle modification and suggest herbal supplements, vitamins, and minerals to patients who experience side effects from pharmaceutical drugs and desire a more natural treatment.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1. Endothelial function in migraine with aura - a systematic review. Butt JH, Franzmann U, Kruuse C. Headache. 2015;55:35–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Lancet. 2015;386:743–800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Migraine: epidemiology, burden, and comorbidity. Burch RC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Neurol Clin. 2019;37:631–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, Smitherman TA. Headache. 2015;55:21–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Two common mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms are highly associated with migraine headache and cyclic vomiting syndrome. Zaki EA, Freilinger T, Klopstock T, et al. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:719–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zaki EA, Freilinger T, Klopstock T, et al. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:719–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Pearls and pitfalls in genetic studies of migraine. Eising E, de Vries B, Ferrari MD, Terwindt GM, van den Maagdenberg AM. Cephalalgia. 2013;33:614–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Gene co-expression analysis identifies brain regions and cell types involved in migraine pathophysiology: a GWAS-based study using the Allen Human Brain Atlas. Eising E, Huisman SMH, Mahfouz A, et al. Hum Genet. 2016;135:425–439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Carnitine palmityltransferase II (CPT2) deficiency and migraine headache: two case reports. Kabbouche MA, Powers SW, Vockell AL, LeCates SL, Hershey AD. Headache. 2003;43:490–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. A possible role for mitochondrial dysfunction in migraine. Stuart S, Griffiths LR. Mol Genet Genomics. 2012;287:837–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Physical comorbidity of migraine and other headaches in US adolescents. Lateef TM, Cui L, Nelson KB, Nakamura EF, Merikangas KR. J Pediatr. 2012;161:308–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lateef TM, Cui L, Nelson KB, Nakamura EF, Merikangas KR. J Pediatr. 2012;161:308–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Trigger factors and premonitory features of migraine attacks: summary of studies. Pavlovic JM, Buse DC, Sollars CM, Haut S, Lipton RB. Headache. 2014;54:1670–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. What turns on a migraine? A systematic review of migraine precipitating factors. Peroutka SJ. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18:454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Oral coenzyme Q10 supplementation in patients with migraine: effects on clinical features and inflammatory markers. Dahri M, Tarighat-Esfanjani A, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Hashemilar M. Nutr Neurosci. 2019;22:607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Improvement of migraine symptoms with a proprietary supplement containing riboflavin, magnesium and Q10: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial. Gaul C, Diener HC, Danesch U. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:516. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Effectiveness of coenzyme Q10 in prophylactic treatment of migraine headache: an open-label, add-on, controlled trial. Shoeibi A, Olfati N, Soltani Sabi M, Salehi M, Mali S, Akbari Oryani M. Acta Neurol Belg. 2017;117:103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Effectiveness of coenzyme Q10 in prophylactic treatment of migraine headache: an open-label, add-on, controlled trial. Shoeibi A, Olfati N, Soltani Sabi M, Salehi M, Mali S, Akbari Oryani M. Acta Neurol Belg. 2017;117:103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. A combination of coenzyme Q10, feverfew and magnesium for migraine prophylaxis: a prospective observational study. Guilbot A, Bangratz M, Ait Abdellah S, Lucas C. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17:433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Effect of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on clinical features of migraine: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Parohan M, Sarraf P, Javanbakht MH, Ranji-Burachaloo S, Djalali M. Nutr Neurosci. 2020;23:868–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. The effects of concurrent coenzyme Q10, L-carnitine supplementation in migraine prophylaxis: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Hajihashemi P, Askari G, Khorvash F, Reza Maracy M, Nourian M. Cephalalgia. 2019;39:648–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cephalalgia. 2019;39:648–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. P026. Pilot study on the use of coenzyme Q10 in a group of patients with episodic migraine without aura. Dalla Volta G, Carli D, Zavarise P, Ngonga G, Vollaro S. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:0. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation for prophylaxis in adult patients with migraine-a meta-analysis. Sazali S, Badrin S, Norhayati MN, Idris NS. BMJ Open. 2021;11:0. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. The synergistic effects of nano-curcumin and coenzyme Q10 supplementation in migraine prophylaxis: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Parohan M, Sarraf P, Javanbakht MH, Foroushani AR, Ranji-Burachaloo S, Djalali M. Nutr Neurosci. 2021;24:317–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Open label prospective experience of supplementation with a fixed combination of magnesium, vitamin B2, feverfew, Andrographis paniculata and coenzyme Q10 for episodic migraine prophylaxis. Vikelis M, Dermitzakis EV, Vlachos GS, et al. J Clin Med. 2020;10:67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vikelis M, Dermitzakis EV, Vlachos GS, et al. J Clin Med. 2020;10:67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. P032. Coenzyme Q-10 and migraine: a lovable relationship. The experience of a tertiary headache center. Pucci E, Diamanti L, Cristina S, Antonaci F, Costa A. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:0. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Familial hemiplegic migraine and episodic ataxia type-2 are caused by mutations in the Ca2+ channel gene CACNL1A4. Ophoff RA, Terwindt GM, Vergouwe MN, et al. Cell. 1996;87:543–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Haploinsufficiency of ATP1A2 encoding the Na+/K+ pump alpha2 subunit associated with familial hemiplegic migraine type 2. De Fusco M, Marconi R, Silvestri L, et al. Nat Genet. 2003;33:192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Typical lateral interactions, but increased contrast sensitivity, in migraine-with-aura. Asher JM, O'Hare L, Romei V, Hibbard PB. Vision (Basel) 2018;2:7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. CGRP-receptor antagonists--a fresh approach to migraine therapy? Durham PL. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1073–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CGRP-receptor antagonists--a fresh approach to migraine therapy? Durham PL. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1073–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. GABA and glutamate in migraine. D’Andrea G, Granella F, Cataldini M, Verdelli F, Balbi T. J Headache Pain. 2001;2:0–60. [Google Scholar]

29. Advances in genetics of migraine. Sutherland HG, Albury CL, Griffiths LR. J Headache Pain. 2019;20:72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Oxidative and antioxidative balance in patients of migraine. Alp R, Selek S, Alp SI, Taşkin A, Koçyiğit A. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21222375/ Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14:877–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Oxidative stress and DNA damage in patients with migraine. Geyik S, Altunısık E, Neyal AM, Taysi S. J Headache Pain. 2016;17:10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Oxidative/antioxidative status, lymphocyte DNA damage, and urotensin-2 receptor level in patients with migraine attacks. Yigit M, Sogut O, Tataroglu Ö, et al. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:367–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:367–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Decreased antioxidant status in migraine patients with brain white matter hyperintensities. Aytaç B, Coşkun Ö, Alioğlu B, et al. Neurol Sci. 2014;35:1925–1929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Oxidative stress and platelet responsiveness in migraine. Tozzi-Ciancarelli MG, De Matteis G, Di Massimo C, Marini C, Ciancarelli I, Carolei A. Cephalalgia. 1997;17:580–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Current experience in testing mitochondrial nutrients in disorders featuring oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction: rational design of chemoprevention trials. Pagano G, Aiello Talamanca A, Castello G, et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:20169–20208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Coenzyme q10 therapy. Garrido-Maraver J, Cordero MD, Oropesa-Ávila M, et al. Mol Syndromol. 2014;5:187–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Nutraceuticals in acute and prophylactic treatment of migraine. Daniel O, Mauskop A. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2016;18:14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Daniel O, Mauskop A. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2016;18:14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Ginkgolide B suppresses intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression via blocking nuclear factor-kappaB activation in human vascular endothelial cells stimulated by oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Li R, Chen B, Wu W, Bao L, Li J, Qi R. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;110:362–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Antioxidant constituents in feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium) extract and their chromatographic quantification. Wu C, Chen F, Wang X, et al. Food Chem. 2006;96:220–227. [Google Scholar]

40. Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium L.): a systematic review. Pareek A, Suthar M, Rathore GS, Bansal V. Pharmacogn Rev. 2011;5:103–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Nutraceuticals in migraine: a summary of existing guidelines for use. Rajapakse T, Pringsheim T. Headache. 2016;56:808–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Nutraceuticals in acute and prophylactic treatment of migraine. Daniel O, Mauskop A. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2016;18:14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Daniel O, Mauskop A. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2016;18:14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Current prophylactic medications for migraine and their potential mechanisms of action. Sprenger T, Viana M, Tassorelli C. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15:313–323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Breastfeeding--evidence based guidelines for the use of medicines. Amir LH, Pirotta MV, Raval M. https://search.informit.org/doi/epdf/10.3316/informit.343177360057414. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40:684–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7 Natural Headache Remedies That Really Work

Headache can be caused by a variety of causes: fatigue, stress, nutrient deficiencies and many others. natural remedies for this disease are not only effective in relieving symptoms headache, but are also able to eliminate the causes of its occurrence and do not have side effects.

1. Water

Surprisingly, often this is all we need. To Unfortunately, many of us suffer from chronic dehydration. And the use coffee, alcohol and sugary drinks only exacerbate the situation. As soon as you feel the symptoms of a coming headache, drink one large glass water. And continue to drink a lot throughout the day. Also increase the amount Water in the body can be eaten by eating vegetables and fruits with a high content of it. Add in your daily diet fresh cucumbers, celery, cabbage, zucchini, spinach, watermelon, grapefruit and orange.

And the use coffee, alcohol and sugary drinks only exacerbate the situation. As soon as you feel the symptoms of a coming headache, drink one large glass water. And continue to drink a lot throughout the day. Also increase the amount Water in the body can be eaten by eating vegetables and fruits with a high content of it. Add in your daily diet fresh cucumbers, celery, cabbage, zucchini, spinach, watermelon, grapefruit and orange.

2. Magnesium

One of the common problems of migraines and headaches is a low level of magnesium in the body. Taking 400-600 mg of magnesium will enhance blood flow to the brain and relieve spasms that cause discomfort. Magnesium can be taken on an ongoing basis - this will reduce the general tendency of the body to occurrence of migraines and headaches. For a quick effect, use liquid nutritional supplements. You can also increase your magnesium levels by adding to your diet. plant foods high in it, such as nuts and seeds, legumes, cereals, avocados, broccoli and bananas.

3. B vitamins

Deficiency of B vitamins - another possible and frequent cause of headache. According to one of the theories about the causes of its occurrence, in there are too many tasks for nerve cells, and sometimes the energy to complete them simply does not enough. So, vitamin B12 plays one of the most important roles in the development of the very energy. Often, patients with migraines are prescribed the entire complex of vitamins of the group B, including 8 vitamins: thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folic acid, vitamin B12, biotin and pantothenic acid. Benefits of B vitamins B is great: they not only relieve headache symptoms, but also improve state of brain cells, blood circulation, as well as the work of the cardiovascular and immune systems.

4. Essential oils of lavender and pepper mint

The natural properties of these essential oils make them very effective in relieving headaches. When applied to the skin, Peppermint Oil stimulates blood flow to the affected areas, which relieves spasms. and relieves pain. Lavender oil works as a sedative and stabilizer moods. Applying oils to relieve headaches is very simple. mix a few drops of both oils in the palms, and then with gentle massaging movements Apply to forehead, temples and back of neck. If the scent is too strong for you, just dilute the mixture with a little almond or coconut oils. It would be ideal to find a quiet place where you can relax, consciously and take a deep breath and wait until the headache starts to let go.

and relieves pain. Lavender oil works as a sedative and stabilizer moods. Applying oils to relieve headaches is very simple. mix a few drops of both oils in the palms, and then with gentle massaging movements Apply to forehead, temples and back of neck. If the scent is too strong for you, just dilute the mixture with a little almond or coconut oils. It would be ideal to find a quiet place where you can relax, consciously and take a deep breath and wait until the headache starts to let go.

5. Herbs

pain. Among them is feverfew (feverfew). It has a relaxing effect on constricted blood vessels of the head. This herb has another ability to suppress inflammation and other types of pain. Action feverfew is akin to aspirin, only this remedy is natural and therefore does not have side effects.

Decoctions of chamomile and collection of spring primrose, lavender, rosemary, mint and valerian.

6. Ginger

Ginger is able to reduce inflammation, including number in blood vessels. For headache relief, prepare hot ginger drink. Pour 3 small pieces of fresh ginger into 2 cups water, bring everything together to a boil and let it brew. In the finished drink for add a slice of lemon and honey to taste. Be sure to inhale when using ginger couples - all together will have a pleasant sedative effect and facilitate headache.

For headache relief, prepare hot ginger drink. Pour 3 small pieces of fresh ginger into 2 cups water, bring everything together to a boil and let it brew. In the finished drink for add a slice of lemon and honey to taste. Be sure to inhale when using ginger couples - all together will have a pleasant sedative effect and facilitate headache.

7. Relaxing bath

cleansing of unnecessary toxins. Try taking a regular detox bath such a recipe. Pour hot water into the bath; temperature should be high enough to stimulate the movement of toxins to the surface of the skin. As the water cools, your body will gradually get rid of harmful substances. toxins. Take this bath once every 7-10 days. Add to water:

1 cup baking soda - it kills bacteria, reduces inflammation and softens the skin,

· essential oils, such as peppermint oil or lavender,

and 2 cups of apple cider vinegar - it is also known for its healing properties, including the ability to relieve headaches, tone the skin and have a beneficial effect on the joints.

Such a variety of natural remedies successfully fight against headache. In general, try to listen to yourself, analyze what could be the cause of the malaise - perhaps this is a changed diet, and the headache is caused by an allergic reaction. Or maybe your body is just dehydrated, or you skipped a meal and your head hurts from low levels blood sugar.

12 Natural Ways to Fight Migraines

The information in this blog has not been verified by your country's public health authority and is not intended as a diagnosis, treatment, or medical advice. Read more

Often manifested as an excruciating, throbbing headache, sometimes causing nausea and photosensitivity, migraine affects 1 billion people worldwide. Some research suggests that at some point in their lives, one in seven people will experience this severe headache—nearly one in five women and one in fifteen men. In the United States of America, migraine treatment costs the healthcare system $78 billion a year.

Migraine is the number one reason patients visit their primary care physicians and emergency departments, where they are often exposed to the radiation that is inevitable during head CT scans. However, sometimes a CT scan is needed to make sure there is no blood in the brain, which is a rare cause of a severe headache.

Cause of migraine

Apparently, migraine is caused by "interruptions" of nerves and blood vessels in the brain, which are associated with incorrect activation of the trigemino-cervical system. Although scientifically challenging, understanding how migraines begin allows doctors to successfully prevent and treat them. In addition, there appears to be a genetic component to migraine, as the condition often affects mothers and daughters.

Migraine headache symptoms:

- Severe headache, usually on one side

- Throbbing sensation

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Presence of a special condition preceding migraine attacks or visualization of zigzag lines

- Light sensitivity

- Sound sensitivity

- Significant disability and missed work days

When a person is diagnosed with a migraine, it is important to try to find the triggers so that they can be eliminated from the diet and prevent a migraine attack.

Some commonly recognized triggers of migraine:

- Cheeses (due to the content of the amino acid tyramine)

- Wine (due to the presence of sulfites)

- Food additives such as MSG and food coloring

- Past head injury and concussion

- Lack of sleep

- Sleep Apnea

- Chronic stress

- Menstruation

- Caffeine may cause migraine attacks in some people and prevent others

- Dehydration

- Common contributors include artificial sweeteners such as aspartame (NutraSweet) found in virtually all diet or zero-calorie sodas.

Drug treatment of acute headaches

Drugs commonly used to treat migraine headaches include the following drugs: additional load on the liver and lower the level of glutathione. When taking these drugs, I recommend an N-acetylcysteine (NAC) supplement for liver protection.

- NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) - ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil), naproxen (Aliv, Naprosyn), diclofenac, indomethacin, and celecoxib (Celebrex) are useful in the short term.

However, according to the Federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which oversees drug safety in the United States, these drugs increase the risk of kidney disease, heart attacks, and strokes. Use them with care.

However, according to the Federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which oversees drug safety in the United States, these drugs increase the risk of kidney disease, heart attacks, and strokes. Use them with care. - Triptans are a class of drugs used at the first sign of a migraine headache. These include sumatriptan (Imitrex), zolmitriptan (Zomig), and rizatriptan (Maxalt). Their action is based on the activation of vascular 5-HT1 receptors. Patients taking antidepressants should exercise caution. However, not everyone tolerates these drugs. According to the Epocrates drug database, some patients experience numbness, redness, chest pain, dizziness, and occasionally heart attacks and strokes.

- Narcotics (codeine, tramadol, hydrocodone, morphine, oxycodone)—commonly used to treat migraine but are usually not as effective as triptans. Produced from the opium poppy. Drug overuse and abuse has become epidemic in the United States, Europe, Russia and Asia. They can be useful for short term use.

Prolonged use can increase the level of pain and even increase the risk that the person stops breathing.

Prolonged use can increase the level of pain and even increase the risk that the person stops breathing.

Other drugs used during acute migraine include anti-nausea drugs such as chlorpromazine, ondansetron, and promethazine. CGRP receptor antagonists are being studied and may become more common in the future. In addition, ergot alkaloids such as ergotamine are sometimes used. In some cases, caffeine helps.

Migraine prevention pharmaceuticals

Prescription drugs are also sometimes used to prevent migraine headaches. An estimated 38 percent of people with migraine are candidates for preventive therapy, but only 3 to 13 percent are taking medication to prevent migraine. These drugs include propranolol, amitriptyline (Elavil), valproic acid, and topiramate (Topamax). The effectiveness of these drugs varies from person to person.

Natural approaches to migraine prevention

Prevention is indeed the best medicine, and trying to stop a migraine from starting is indeed the best strategy. Usually, before prescribing pharmaceutical drugs for migraine prevention, I recommend that my patients make dietary and lifestyle changes, as well as try natural supplements, as a first step. In most cases, this approach is effective.

Usually, before prescribing pharmaceutical drugs for migraine prevention, I recommend that my patients make dietary and lifestyle changes, as well as try natural supplements, as a first step. In most cases, this approach is effective.

Detox your body

Over the past 100 years, thousands of chemicals have been created and released into water, air and even home environments by companies. Yet we still know next to nothing about how most of these chemicals affect us. However, we do know for sure that many of them have negative health effects, including migraine headaches. Toxic chemicals accumulate in the body of every person, and it is impossible to completely avoid this. But you can try to minimize the long-term effects of their exposure. Detoxifying the body is critical to its healing. Learn more about detoxifying your body and fixing leaky gut.

Get your diet in order

It is important for migraine sufferers to avoid highly processed foods. Processed foods contain chemicals that are foreign to the human body (xenobiotics) and have a negative impact on our physiology. These substances include food preservatives and food colorings. Many migraine sufferers do well when they avoid dairy and grains, including gluten. Other migraine patients are sensitive to corn and soy.

These substances include food preservatives and food colorings. Many migraine sufferers do well when they avoid dairy and grains, including gluten. Other migraine patients are sensitive to corn and soy.

A good start is to switch to a diet high in fruits and vegetables. If possible, buy pesticide-free (organic) fruits and vegetables. Check out the list of "clean thirteen" foods that are safer to eat in the traditional version, and the "dirty dozen" - a list of fruits that should only be bought in the organic version. Also, if you are a meat eater, buy grass-fed meat that is free of antibiotics and hormones. Although such meat will be more expensive, there is potential for cost savings if it helps prevent chronic diseases and improve quality of life.

In addition to proper diet, adequate fluid intake, daily exercise and sleep optimization, there are several natural treatments that have been shown in scientific studies to be effective in preventing migraine headaches.

Dietary Supplements

Over the past few decades, research has shown that many dietary supplements are beneficial in preventing migraine headaches. As more people seek non-drug approaches, supplements are becoming a popular alternative.

As more people seek non-drug approaches, supplements are becoming a popular alternative.

Riboflavin - also known as vitamin B2. This vitamin has been shown to be effective in preventing migraine headaches. A 2017 study in the Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics , which evaluated eleven studies, concluded: "Riboflavin is well tolerated, inexpensive, and has been shown to be effective in reducing headache frequency in a sick adult patient." Research published in 2014 in Almanac Canadian Family Physician also demonstrated the usefulness of riboflavin in the treatment of children with migraine headaches. Recommended dose: Adults - 400 mg of riboflavin per day. Pediatrics - 100-400 mg of riboflavin per day.

Magnesium - I have been recommending magnesium to migraine patients for over a decade. In my experience, it helps prevent headaches in four out of five people. Scientific research supports my medical experience. A 2017 study published in the journal The Journal of Head and Face Pain, showed that migraine headaches could be prevented with magnesium. Other studies show similar results. Suggested dose: Magnesium chelate 125-500 mg daily to help prevent migraines. Start with a small dose and increase as needed.

A 2017 study published in the journal The Journal of Head and Face Pain, showed that migraine headaches could be prevented with magnesium. Other studies show similar results. Suggested dose: Magnesium chelate 125-500 mg daily to help prevent migraines. Start with a small dose and increase as needed.

Ginger - prevents nausea, but also useful in the treatment of migraine. It is used in Ayurvedic medicine. Study 1990 years demonstrated knowledge of the effectiveness of ginger in treating migraines, and a 2014 study proved that ginger is as effective in treating migraines as the pharmaceutical drug sumatriptan. In addition, ginger tea helps to reduce the symptoms of nausea. Recommended dose: 250-500 mg of ginger once or twice a day.

Omega-3 Fish Oil - A study published in 2017 in Nutritional Neuroscience, found that omega-3 fish oil helped reduce the duration of migraine headaches. A 2012 study compared fish oil plus valproic acid versus valproic acid alone for migraine prevention. The combination of fish oil and valproic acid appeared to be more effective in preventing headaches. Finally, a 2017 study in which subjects took fish oil and curcumin (turmeric) showed a reduction in migraines. Recommended dose: 2000-4000 mg of omega-3 fish oil per day. The daily dose should be divided into two doses.

The combination of fish oil and valproic acid appeared to be more effective in preventing headaches. Finally, a 2017 study in which subjects took fish oil and curcumin (turmeric) showed a reduction in migraines. Recommended dose: 2000-4000 mg of omega-3 fish oil per day. The daily dose should be divided into two doses.

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) - Research indicates that CoQ10 may help prevent migraines. A 2017 study found that "...CoQ10 is able to reduce the frequency of headaches, as well as make them shorter in duration and less severe, with a favorable safety profile." Another 2017 study and a 2011 study also showed the benefits of supplementing with CoQ10 for migraine prevention. Recommended dose: 100-300 mg of CoQ10 per day.

Alpha Lipoic Acid - A 2017 study published in the Journal of Medicinal Food found that, when taken at a dose of 400 mg twice daily, this powerful antioxidant helps prevent the frequency and duration of migraine headaches. A 2007 study showed similar results. Recommended dose: 600-800 mg of alpha lipoic acid per day to prevent migraines; you can divide the dose into several parts.

A 2007 study showed similar results. Recommended dose: 600-800 mg of alpha lipoic acid per day to prevent migraines; you can divide the dose into several parts.

Melatonin - Melatonin, the "sleep vitamin", has been proven to be effective in preventing migraine headaches. A 2017 study compared the results of 3mg melatonin and prescription valproic acid. Melatonin has demonstrated higher efficacy with no side effects. Another study from the same year proved the role of melatonin in lowering CGRP levels and preventing migraines. Finally, another study from 2017, the results of which were published in the journal Journal of Family Practice found melatonin to be as effective in migraine prevention as the prescription drug amitriptyline. Recommended dose: 3-10 mg of melatonin every evening 1-2 hours before bedtime.

Feverfew Feverfew ( Tanacetum parthenium ) is a perennial herb well known for its medicinal properties. It is often used as an aid in migraine prevention, and studies show some benefit from this herb. A 2017 study found that when taken in combination with magnesium and Coenzyme Q10, feverfew was effective in preventing migraines. Recommended dose: 250 mg of feverfew once or twice a day.

A 2017 study found that when taken in combination with magnesium and Coenzyme Q10, feverfew was effective in preventing migraines. Recommended dose: 250 mg of feverfew once or twice a day.

Butterbur - This supplement also helps prevent migraines. However, it should only be taken in the absence of pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PA) as this substance can cause liver problems. Recommended dose: 75 mg of butterbur one to three times a day.

Other useful preventive measures

- Regular aerobic exercise

- Yoga

- Acupuncture

- Meditation

- Chamomile essential oil has shown benefit when applied to the upper lip or when used with a diffuser

- Lavender essential oil has shown benefit when applied to the upper lip or when used with a diffuser

Migraine relief possible

Migraine headaches are the number one reason people miss work and seek medical attention. An estimated 1 billion people worldwide suffer from severe headaches. Remember that a healthy diet can play an important role in migraine prevention. Eliminating migraine triggers is also critical, and in many cases this includes dairy and gluten. Pharmaceuticals can also be very effective, but concerns about side effects keep people looking for alternatives. Fortunately, those exist. As a first step, many people start with riboflavin. The addition of magnesium chelate and ginger should also be considered. If these three additives are not sufficient, the use of additional additives may be considered. Be patient, finding the right combination can take months.

An estimated 1 billion people worldwide suffer from severe headaches. Remember that a healthy diet can play an important role in migraine prevention. Eliminating migraine triggers is also critical, and in many cases this includes dairy and gluten. Pharmaceuticals can also be very effective, but concerns about side effects keep people looking for alternatives. Fortunately, those exist. As a first step, many people start with riboflavin. The addition of magnesium chelate and ginger should also be considered. If these three additives are not sufficient, the use of additional additives may be considered. Be patient, finding the right combination can take months.

Eat healthy, think healthy and be healthy.

Reference information:

- Epocrates drug database, accessed December 9, 2017

- Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al; The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy.

Neurology. 2007;68:343–349.

Neurology. 2007;68:343–349. - Silberstein, S. D., Lipton, et. Al. Efficacy and Safety of Topiramate for the Treatment of Chronic Migraine: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 47: 170–180. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00684.x

- Neurol Sci. 2017 May;38(Suppl 1):117-120. doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-2901-1.

- Thompson DF, Saluja HS. Prophylaxis of migraine headaches with riboflavin: A systematic review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;42:394–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12548

- Sherwood M, Goldman R.D. Effectiveness of riboflavin in pediatric migraine prevention. Canadian Family Physician. 2014;60(3):244-246.

- J Ethnopharmacol. 1990 Jul;29(3):267-73.

- Maghbooli, M., Golipour, F., Moghimi Esfandabadi, A. and Yousefi, M. (2014), Comparison Between the Efficacy of Ginger and Sumatriptan in the Ablative Treatment of the Common Migraine. Phytother. Res., 28: 412–415. doi:10.

1002/ptr.4996

1002/ptr.4996 - Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials Leila Maghsoumi-Norouzabad, Anahita Mansoori, Reza Abed & Farideh Shishehbor Nutritional Neuroscience Vol. 0 , Iss. 0.0

- Tajmirriahi M, Sohelipour M, Basiri K, Shaygannejad V, Ghorbani A, Saadatnia M. The effects of sodium valproate with fish oil supplementation or alone in migraine prevention: A randomized single-blind clinical trial. Iranian Journal of Neurology. 2012;11(1):21-24.

- Immunogenetics. 2017 Jun;69(6):371-378. doi: 10.1007/s00251-017-0992-8. Epub 2017 May 6.

- Acta Neurol Belg. Mar 2017;117(1):103-109. doi: 10.1007/s13760-016-0697-z. Epub 2016 Sep 26.

- Neurol Sci. 2017 May;38(Suppl 1):117-120. doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-2901-1.

- Cephalalgia. 2011 Jun;31(8):897-905. doi: 10.1177/0333102411406755. Epub 2011 May 17.

- Cavestro Cinzia, Bedogni Giorgio, Molinari Filippo, Mandrino Silvia, Rota Eugenia, and Frigeri Maria Cristina.

Learn more