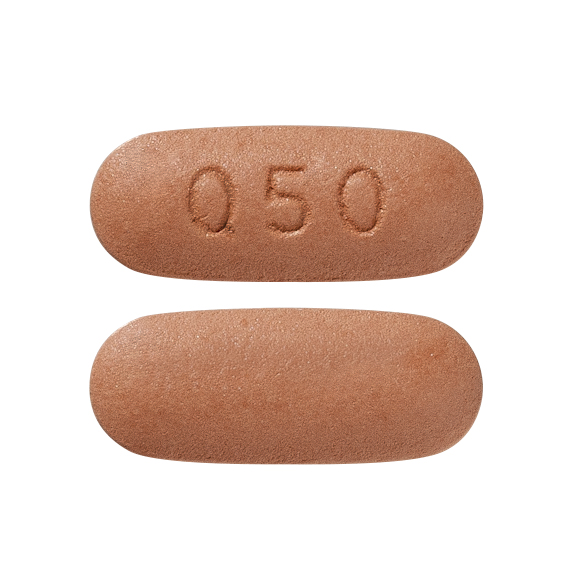

Quetiapine 25mg sleep

Safety of low doses of quetiapine when used for insomnia

Save citation to file

Format: Summary (text)PubMedPMIDAbstract (text)CSV

Add to Collections

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Name your collection:

Name must be less than 100 characters

Choose a collection:

Unable to load your collection due to an error

Please try again

Add to My Bibliography

- My Bibliography

Unable to load your delegates due to an error

Please try again

Your saved search

Name of saved search:

Search terms:

Test search terms

Email: (change)

Which day? The first SundayThe first MondayThe first TuesdayThe first WednesdayThe first ThursdayThe first FridayThe first SaturdayThe first dayThe first weekday

Which day? SundayMondayTuesdayWednesdayThursdayFridaySaturday

Report format: SummarySummary (text)AbstractAbstract (text)PubMed

Send at most: 1 item5 items10 items20 items50 items100 items200 items

Send even when there aren't any new results

Optional text in email:

Create a file for external citation management software

Full text links

Atypon

Full text links

Review

. 2012 May;46(5):718-22.

doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q697. Epub 2012 Apr 17.

Holly V Coe 1 , Irene S Hong

Affiliations

Affiliation

- 1 School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, State University of New York at Buffalo, NY, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 22510671

- DOI: 10.1345/aph.1Q697

Review

Holly V Coe et al. Ann Pharmacother. 2012 May.

. 2012 May;46(5):718-22.

doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q697. Epub 2012 Apr 17.

Authors

Holly V Coe 1 , Irene S Hong

Affiliation

- 1 School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, State University of New York at Buffalo, NY, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 22510671

- DOI: 10.1345/aph.1Q697

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the safety of low doses of quetiapine when used for insomnia.

Data sources: A literature search was performed using PubMed and EMBASE (January 1990-November 2011) using the terms quetiapine, insomnia, sleep, low-dose, subtherapeutic, safety, and weight gain.

Study selection and data extraction: Two prospective trials were identified that evaluated the effect of quetiapine in primary insomnia. In addition, 2 retrospective cohort studies were identified that evaluated the safety of low doses of quetiapine when used for insomnia. Several case reports on adverse effects with low doses of the drug were also included.

Data synthesis: Quetiapine is commonly used off-label for treatment of insomnia. When used for sleep, doses typically seen are less than the Food and Drug Administration-recommended dosage of 150-800 mg/day; those evaluated in the studies reviewed here were 25-200 mg/day). At recommended doses, atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine are associated with metabolic adverse events (diabetes, obesity, hyperlipidemia). Adverse effects in the prospective trials were patient-reported and were minor, including drowsiness and dry mouth; however, the trials were limited by their small sample size and short duration. The retrospective cohort studies found that quetiapine was associated with significant increases in weight compared to baseline. Serious adverse events identified from case reports included fatal hepatotoxicity, restless legs syndrome, akathisia, and weight gain.

At recommended doses, atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine are associated with metabolic adverse events (diabetes, obesity, hyperlipidemia). Adverse effects in the prospective trials were patient-reported and were minor, including drowsiness and dry mouth; however, the trials were limited by their small sample size and short duration. The retrospective cohort studies found that quetiapine was associated with significant increases in weight compared to baseline. Serious adverse events identified from case reports included fatal hepatotoxicity, restless legs syndrome, akathisia, and weight gain.

Conclusions: There are potential safety concerns when using low-dose quetiapine for treatment of insomnia. These concerns should be evaluated in further prospective studies. Based on limited data and potential safety concerns, use of low-dose quetiapine for insomnia is not recommended.

Similar articles

-

[No quetiapine for sleeping disorders].

Tak LM, van Berlo-van de Laar IR, Doornbos B. Tak LM, et al. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2013;157(4):A5740. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2013. PMID: 23343742 Dutch.

-

Effects of quetiapine on sleep in nonpsychiatric and psychiatric conditions.

Wine JN, Sanda C, Caballero J. Wine JN, et al. Ann Pharmacother. 2009 Apr;43(4):707-13. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L320. Epub 2009 Mar 18. Ann Pharmacother. 2009. PMID: 19299326 Review.

-

Quetiapine for insomnia associated with refractory depression exacerbated by phenelzine.

Sokolski KN, Brown BJ. Sokolski KN, et al. Ann Pharmacother. 2006 Mar;40(3):567-70. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G416. Epub 2006 Feb 14. Ann Pharmacother. 2006. PMID: 16478812

-

Quetiapine for insomnia: A review of the literature.

Anderson SL, Vande Griend JP. Anderson SL, et al. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014 Mar 1;71(5):394-402. doi: 10.2146/ajhp130221. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014. PMID: 24534594 Review.

-

Quetiapine for primary insomnia: a double blind, randomized controlled trial.

Tassniyom K, Paholpak S, Tassniyom S, Kiewyoo J. Tassniyom K, et al. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010 Jun;93(6):729-34. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010. PMID: 20572379 Clinical Trial.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

Efficacy of quetiapine for delirium prevention in hospitalized older medical patients: a randomized double-blind controlled trial.

Thanapluetiwong S, Ruangritchankul S, Sriwannopas O, Chansirikarnjana S, Ittasakul P, Ngamkala T, Sukumalin L, Charernwat P, Saranburut K, Assavapokee T.

Thanapluetiwong S, et al. BMC Geriatr. 2021 Mar 31;21(1):215. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02160-7. BMC Geriatr. 2021. PMID: 33789580 Free PMC article. Clinical Trial.

Thanapluetiwong S, et al. BMC Geriatr. 2021 Mar 31;21(1):215. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02160-7. BMC Geriatr. 2021. PMID: 33789580 Free PMC article. Clinical Trial. -

Comparative effectiveness and safety of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for insomnia: an overview of reviews.

Rios P, Cardoso R, Morra D, Nincic V, Goodarzi Z, Farah B, Harricharan S, Morin CM, Leech J, Straus SE, Tricco AC. Rios P, et al. Syst Rev. 2019 Nov 15;8(1):281. doi: 10.1186/s13643-019-1163-9. Syst Rev. 2019. PMID: 31730011 Free PMC article. Review.

-

Prescribing Practices of Quetiapine for Insomnia at a Tertiary Care Inpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Unit: A Continuous Quality Improvement Project.

Chow ES, Zangeneh-Kazemi A, Akintan O, Chow-Tung E, Eppel A, Boylan K.

Chow ES, et al. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017 Jul;26(2):98-103. Epub 2017 Jul 1. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017. PMID: 28747932 Free PMC article.

Chow ES, et al. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017 Jul;26(2):98-103. Epub 2017 Jul 1. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017. PMID: 28747932 Free PMC article. -

Perils of Pragmatic Psychiatry: How We Can Do Better.

Koola MM, Sebastian J. Koola MM, et al. HSOA J Psychiatry Depress Anxiety. 2016;2(1):002. doi: 10.24966/pda-0150/100002. Epub 2016 Feb 23. HSOA J Psychiatry Depress Anxiety. 2016. PMID: 26998529 Free PMC article.

-

Dispensed prescriptions for quetiapine and other second-generation antipsychotics in Canada from 2005 to 2012: a descriptive study.

Pringsheim T, Gardner DM. Pringsheim T, et al. CMAJ Open. 2014 Oct 1;2(4):E225-32. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20140009. eCollection 2014 Oct.

CMAJ Open. 2014. PMID: 25485247 Free PMC article.

CMAJ Open. 2014. PMID: 25485247 Free PMC article.

See all "Cited by" articles

Publication types

MeSH terms

Substances

Full text links

Atypon

Cite

Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Name your collection:

Name must be less than 100 characters

Choose a collection:

Unable to load your collection due to an error

Please try again

Send To

Will it work for you?

Many doctors are unwilling to prescribe traditional sleeping tablets because of concerns that they can lead to addiction and tolerance. GPs often turn to other types of drugs that display sedative side effects and instead prescribe these to help people sleep.

GPs often turn to other types of drugs that display sedative side effects and instead prescribe these to help people sleep.

These drugs are used ‘off label’: they’re not licensed to treat certain conditions but can be effective, nevertheless. Quetiapine is one such off label drug used to treat insomnia. You can find more information about quetiapine from NICE on their website.

Quetiapine is an antipsychotic medication

In the UK quetiapine is licensed for the following indications:

- schizophrenia

- treatment of mania in bipolar disorder

- treatment of depression in bipolar disorder

- prevention of mania and depression in bipolar disorder

- in addition to primary medication to treat major depression.

In the USA quetiapine is commonly sold under the brand name Seroquel.

Quetiapine as a treatment for primary insomnia

Despite a lack of evidence pointing to its effectiveness in helping improve sleep, quetiapine is increasingly prescribed at low doses to manage sleep disorders.

For instance, between 2005 and 2012, prescriptions of quetiapine for sleep disturbances increased by 300% in Canada.1

In addition, data from a wide-ranging US survey found that between 1999 and 2010, quetiapine was the fourth most common drug prescribed for insomnia (11%).2

Neither of these countries had approved the drug as a licensed alternative to treating insomnia.3

People with sleeping issues often turn to medication first. Many people don’t know that there are more effective treatments without side effects. Sleepstation’s online CBTi programme can significantly improve sleep in just four sessions.

Sleepstation is:

clinically validated and accredited by the NHS

proven to be more effective than medication

delivered entirely online

uniquely personal to your situation

fully supported by sleep experts.

Is quetiapine useful as a treatment for insomnia?

Quetiapine can improve symptoms that may interfere with sleep, such as reducing feelings of anxiety and depression. So it’s difficult to evaluate its effects as a sleep medication when the drug is designed to improve symptoms that, in themselves, also affect sleep.

To establish whether the drug has a direct effect on sleep, we can look at trials with healthy volunteers who do not show any signs of psychiatric illness. These studies allow the drug’s influence on sleep to be accurately assessed.

However, where quetiapine is concerned, there have been very few studies that have evaluated its effect on sleep in patients who were not also experiencing a psychiatric illness.

One study evaluated 14 healthy males who were given placebo or quetiapine at 25mg and 100mg doses for three consecutive nights.4

Both doses of quetiapine produced statistically significant improvements in objective and subjective ratings of sleep including:

- total sleep time

- sleep efficiency

- sleep latency

- duration of stage N2 sleep.

Despite these positive effects, the 100mg dose was found to decrease the amount of REM sleep, which is a stage of sleep important for our emotional wellbeing.

The 100mg dose also increased the number of periodic leg movements and two subjects taking quetiapine experienced orthostatic hypotension, which is a drop in blood pressure when a person moves from sitting to standing.

In a study of people with primary insomnia, 25 participants received either 25mg of quetiapine or a placebo. No significant improvements were seen in how long people slept for, how quickly they fell asleep, their daytime alertness or sleep satisfaction.5

A more recent study replicated insomnia by using traffic noise to keep people awake. They found that 50mg quetiapine increased sleep continuity and total sleep time when compared to placebo.

However, there was evidence of hangover effects in the morning with quetiapine causing daytime sleepiness and difficulty concentrating. 6

6

How quetiapine could disrupt your sleep

Quetiapine has a long list of side effects and a large number of these are potentially disruptive to your sleep. It’s hardly ideal for a drug that’s meant to help you sleep!

Side effects that could disrupt your sleep — and that occur in at least one in 10 people taking quetiapine — include:

- dizziness, weakness and shortness of breath

- feeling sleepy

- headaches, fever, shortness of breath

- a dry mouth

- weight gain and increased appetite

- a rapid or irregular heartbeat

- constipation, upset stomach, indigestion, vomiting

- swelling of arms or legs

- sleep disorders

- feeling irritated

- thoughts of suicide.

In the clinical trials of quetiapine there have been other reports of side effects that could potentially disturb sleep.

Two patients, on low dose quetiapine for insomnia, discontinued the drug due to akathisia — a movement disorder characterised by a feeling of inner restlessness and an inability to stay still. 7

7

In another study of low dose quetiapine for insomnia in people diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, two out of 13 participants stopped using the drug due to an exacerbation of restless leg symptoms.8

Quetiapine or sleeping tablets?

One of the most cited reasons for avoiding the use of using traditional sleeping tablets to treat insomnia is a concern that they’re addictive. This is why GPs look to prescribe alternatives that are not associated with addiction.

However repeated studies have shown that quetiapine has abuse potential. 910111213 This raises serious questions concerning its suitability as a replacement for either benzodiazepines or so-called ‘Z’ drugs.

Does the evidence warrant use of quetiapine for insomnia?

While there’s some evidence that quetiapine can improve sleep in healthy participants, only minor improvements in sleep are seen in patients with insomnia.

The unclear results seen in the few trials described above provide little evidence to justify prescribing quetiapine for insomnia. 121314 The general consensus amongst studies is that quetiapine should be avoided as a drug for insomnia.

The results are reinforced by a review of quetiapine for use in insomnia which concluded that any benefit in the treatment of insomnia has not been proven to outweigh potential risks. 15

This is true even in patients who require treatment for a condition for which quetiapine is approved, such as schizophrenia.

The general consensus amongst studies is that quetiapine should be not be used as a drug for insomnia.

So it’s difficult to understand how a drug hardly renowned for improving insomnia — and associated with such a broad range of side-effects and a potential for addiction and abuse — can be so widely prescribed.

Should you question quetiapine?

If you’re prescribed quetiapine by your GP or psychiatrist then you have a legitimate case for asking why they’re using this drug rather than the benzodiazepines and the ‘Z’ drugs that have proven effectiveness in the treatment of insomnia.

Remember this is about your health and your sleep, not theirs. You have every right to discuss the most appropriate treatment for your condition.

The best starting point for treating insomnia that has lasted for more than four weeks (chronic insomnia) is well-recogised to be cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi).

Unlike sleeping pills, CBTi helps you overcome the underlying causes of your sleep problems rather than just alleviating the symptoms. It’s the method we use at Sleepstation and it’s incredibly effective.

The first step in treating insomnia with CBTi is to identify the causes of the insomnia. At Sleepstation, we guide you through this, then help you to address the causes of your sleep problem and provide you with the tools you need to rebuild your sleep.

With help from our sleep experts and sleep coaches, you’ll better understand your sleep and learn ways to combat your sleep problems and stop them reoccuring. Most people see an improvement their sleep after just three sessions.

Sleepstation’s programme works if you’re currently taking sleeping tablets and can help to reduce the amount you’re taking, or stop altogether. You can get started in just a couple of clicks, here.

Summary

- Quetiapine is neither approved nor recommended for primary insomnia although the drug is often prescribed off-label as a sleep aid.

- There is evidence of addiction to quetiapine.

- Side effects associated with quetiapine — such as next morning hangover symptoms and daytime fatigue — means that patients should be cautious.

- Drugs such as quetiapine cannot treat a sleep problem, they will only mask them.

- Sleepstation is a clinically-validated, drug-free alternative that is proven to improve sleep.

References

-

Pringsheim T, Gardner DM. Dispensed prescriptions for quetiapine and other second-generation antipsychotics in Canada from 2005 to 2012: a descriptive study.

↑ CMAJ Open 2014;2:E225-32.

CMAJ Open 2014;2:E225-32. -

Bertisch SM, Herzig SJ, Winkelman JW, Buettner C. National use of prescription medications for insomnia: NHANES 1999-2010. Sleep 2014;37:343–9.

↑ -

Marston L, Nazareth I, Petersen I, Walters K, Osborn DPJ. Prescribing of antipsychotics in UK primary care: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006135.

↑ -

Cohrs S, Rodenbeck A, Guan Z, Pohlmann K, Jordan W, Meier A, et al. Sleep-promoting properties of quetiapine in healthy subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:421–9.

↑ -

Tassniyom K, Paholpak S, Tassniyom S, Kiewyoo J. Quetiapine for primary insomnia: a double blind, randomized controlled trial.

↑ J Med Assoc Thai 2010;93:729–34.

J Med Assoc Thai 2010;93:729–34. -

Karsten J, Hagenauw LA, Kamphuis J, Lancel M. Low doses of mirtazapine or quetiapine for transient insomnia: A randomised, double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol 2017;31:327–37.

↑ -

Catalano G, Grace JW, Catalano MC, Morales MJ, Cruse LM. Acute akathisia associated with quetiapine use. Psychosomatics 2005;46:291–301.

↑ -

Juri C, Chaná P, Tapia J, Kunstmann C, Parrao T. Quetiapine for insomnia in Parkinson disease: Results from an open-label trial. Clin Neuropharmacol 2005;28:185–7.

↑ -

Waters BM, Joshi KG. Intravenous quetiapine-cocaine use (“Q-ball”).

↑ Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:173–4.

Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:173–4. -

Hussain MZ, Waheed W, Hussain S. Intravenous quetiapine abuse. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1755–6.

↑ -

Pinta ER, Taylor RE. Quetiapine addiction? Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:174–5.

↑ -

Pierre JM, Shnayder I, Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC. Intranasal quetiapine abuse. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1718.

↑ -

Erdoğan S. Quetiapine in substance use disorders, abuse and dependence possibility: a review. Turk Psikiyatri Derg 2010;21:167–75.

↑ -

Wine JN, Sanda C, Caballero J. Effects of quetiapine on sleep in nonpsychiatric and psychiatric conditions.

↑ Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:707–13.

Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:707–13. -

Pigeon WR. Diagnosis, prevalence, pathways, consequences & treatment of insomnia. Indian J Med Res 2010;131:321–32.

↑

Quetiapine and its place in the treatment of various diseases among atypical apsychotics :: DIFFICULT PATIENT

V.I. Maksimov

Psychoneurological Dispensary No. 21, Moscow

Currently, atypical apsychotics (AA) are becoming increasingly important in the treatment of mental illness, differing from typical neuroleptics (TN) by a number of properties, among which the foreground is, according to the definition of H.Y. Meltzer (1996), an effective effect on both productive and negative symptoms, in the absence of adverse neurological events.

The emergence of new powerful antipsychotics, such as clozapine, risperidone and olanzapine, has led to a significant improvement in the quality of life of patients, primarily with chronic, severe and drug-resistant psychopathological conditions [1-4].

However, the absence or almost complete absence of neurological side effects from the use of strong AAs did not mean the absence of adverse events at all. Along with a pronounced reduction in the symptoms of both poles (positive and negative), there was a dramatic emergence of a new class of adverse events and complications [5-9].

We are talking about the syndrome of neuroendocrine dysfunction (NED), the structure of which includes three symptom complexes: hyperprolactinemia syndrome (HP), metabolic syndrome (MS) and dysthyroidism (DT). In turn, each symptom complex includes a number of rather serious disorders. HP is characterized by menstrual irregularities, gynecomastia (in men), galactorrhea (in both sexes), decreased libido (in both sexes). MS is characterized by: weight gain, eating disorders, hyperglycemia, increased thirst and polyuria, the risk of developing type II diabetes mellitus. With DT, the following are observed: neurasthenic symptoms, heart rhythm disturbances, disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, hyperkeratosis and brittle hair [10-14].

Responsibility for the development of NED lies with hormonal imbalance in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal and hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axes, which is associated with disorders of the histaminergic and dopaminergic systems, in particular blockade of H1 and D receptors. The latter, and especially the second type (D2), are the main AA target locus, the strength of which correlates with the intensity of D-receptor blockade. The bulk of the observations on the development of VLED just falls in descending order on the cases of the use of olanzapine, risperidone and clozapine [15-18].

An attempt to use less active AAs, such as ziprasidone, aripiprazole, sulpiride, revealed an insufficient drug effect, primarily on productive symptoms, and then the absence of reliable signs of an effect on deficient disorders. At the same time, the severity of NED not only remained quite significant, but in the case of sulpiride even exceeded that of the most powerful AAs [18-21].

In light of this, it is interesting to use drugs of moderate activity, with a distinct therapeutic effect and unexpressed side effects, in particular, quetiapine. Comparative trials have shown that quetiapine is not inferior to TN (haloperidol, chlorpromazine) in terms of the effect on the severity of mental disorders, productive symptoms, and the likelihood of achieving a therapeutic response, which was confirmed by the results of a meta-analysis of these trials [22-27].

Comparative trials have shown that quetiapine is not inferior to TN (haloperidol, chlorpromazine) in terms of the effect on the severity of mental disorders, productive symptoms, and the likelihood of achieving a therapeutic response, which was confirmed by the results of a meta-analysis of these trials [22-27].

Quetiapine is rapidly and completely absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, 83% binds to blood proteins. The maximum concentration occurs after 1.5 hours. 95% of the drug is biotransformed to inactive metabolites, of which 73% is excreted by the kidneys, 21% through the intestines. The half-life (T1 / 2) is about 7 hours. The pharmacokinetics of quetiapine is linear and does not depend on gender. In elderly patients, there is a decrease in metabolic clearance (Cl) by 30-50% compared with that in patients aged 18-50 years. In severe disorders of the liver and kidneys, Cl is 25% lower (creatinine clearance less than 30 ml/min) [28, 29].

This means high biological digestibility regardless of gender and age, rapid onset of a therapeutic effect, no cumulation, the possibility of using doses adequate to the somatic state in the elderly and diseases of the parenchymal organs of mild and moderate severity.

The mechanism of action of quetiapine is based on the blockade of serotonergic (5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C), dopaminergic (D1, D2, D3, D4), adrenergic (α1, α2), antihistamine (H1) receptors. It has almost no affinity for muscarinic cholinergic receptors (M1) and is intact for benzodiazepine and GABA receptors. Quetiapine affinity, based on the sum of opinions, is ranked in descending order as follows: H1>α1>5-HT2A>α2>D2>5-HT1A>D1>5-HT2C>D3>D4>M1, where H1 and group α (especially α1 ) are responsible for the nonspecific sedative effect, the 5-HT group (especially 5-HT2A) - for the effect on negative symptoms, D (especially D2) - for the antipsychotic neuroleptic and, accordingly, extrapyramidal action. In accordance with the results of positron emission tomography, the effect of quetiapine on serotonin 5HT2 and dopamine D2 receptors lasts up to 12 hours [29-33].

Quetiapine is started at 50 mg titrated in 50 mg increments on the same day until a positive effect is achieved, ranging from 300 mg to 800 mg or more. However, the upper, lethal threshold of the dosage of the drug is not known. For example, a case of a single dose of 3000 mg of the drug was described, without irreversible consequences, and side effects in this case - hypotension, tachycardia, somnolence disappeared after a day [1, 32].

However, the upper, lethal threshold of the dosage of the drug is not known. For example, a case of a single dose of 3000 mg of the drug was described, without irreversible consequences, and side effects in this case - hypotension, tachycardia, somnolence disappeared after a day [1, 32].

Quetiapine finds its place in the treatment of the widest range of psychopathological conditions with varying degrees of severity, stage of the disease, age, nosology, poles of disorders.

In acute conditions (schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum diseases), the use of quetiapine significantly showed, based on PANSS and CGI scores, a pronounced reduction in psychotic disorders, not inferior to the effect of TN. At the same time, it is characteristic that during the first week an antipsychotic effect occurred with the leveling of arousal, aggression, hostility, during the 2-8th week the hallucinatory-paranoid and affective symptoms weakened, and starting from the 8th week, there was a remission or a significant relaxation process flow. A feature of the impact on paranoid symptoms was the predominant reduction of delusional components, while hallucinatory disorders, especially verbal hallucinosis, were reduced to a lesser extent. At the final stages, a regulating, “socializing” effect was noted. Compared with other AAs (olanzapine, risperidone), quetiapine showed an anticipatory initial antipsychotic effect, later on the effect of the compared AAs either became statistically indistinguishable, or other AAs showed greater activity in the treatment of paranoid symptoms. The administration of quetiapine occurred either in the recommended way with a dose increase of 50 mg per day, or in the most acute cases, a rapid increase in dosages over 3-4 days: 200-400-600-800 mg or 300-600-900 mg [34-41].

A feature of the impact on paranoid symptoms was the predominant reduction of delusional components, while hallucinatory disorders, especially verbal hallucinosis, were reduced to a lesser extent. At the final stages, a regulating, “socializing” effect was noted. Compared with other AAs (olanzapine, risperidone), quetiapine showed an anticipatory initial antipsychotic effect, later on the effect of the compared AAs either became statistically indistinguishable, or other AAs showed greater activity in the treatment of paranoid symptoms. The administration of quetiapine occurred either in the recommended way with a dose increase of 50 mg per day, or in the most acute cases, a rapid increase in dosages over 3-4 days: 200-400-600-800 mg or 300-600-900 mg [34-41].

The antipsychotic effect of quetiapine is due not only to a selective effect on D (D2 > D1 > D3 > D4) and 5-HT (5-HT2a > 5-HT1a > 5-HT2c) receptors, but also by the ratio of the degree of blockade between group D and group 5 -NT. The value of the coefficient of this ratio is the subject of dispute among scientists, and thus the direction of further research.

The value of the coefficient of this ratio is the subject of dispute among scientists, and thus the direction of further research.

Quetiapine is also used in the treatment of borderline mental disorders. We are talking about panic attacks, obsessive-phobic, anxious, senesto-hypochondriac, subdepressive, personality disorders. In doses from 50 mg to 300 mg, the drug has, first of all, a sedative effect, then in decreasing order: anti-aggressive, anxiolytic, antidepressant, anti-obsessive action. As in psychotic cases, quetiapine showed an outstripping effect compared to TN and strong AAs, with a record speed of onset of a therapeutic effect [42–45].

As can be seen from the text, the leading effect can be explained by the rapid blockade of H1 and the α group (α1 > α2), which have a powerful sedative effect, as well as the 5-HT system, which is responsible for a pronounced anxiolytic effect.

The effectiveness of long-term use of quetiapine in remission, according to randomized trials, at maintenance doses of an average of 250 mg, is quite reliable. Moreover, a comparison with the effect of olanzapine prescribed for the same conditions showed no differences in all points, with the exception of a more pronounced antidepressant effect of quetiapine [46].

Moreover, a comparison with the effect of olanzapine prescribed for the same conditions showed no differences in all points, with the exception of a more pronounced antidepressant effect of quetiapine [46].

From this it can be concluded that quetiapine is in a more active relationship with 5-HT receptors than other AAs.

Has no restrictions on the use of quetiapine and on an age scale. Thus, the use of the drug in pediatric practice at a dose of 25 mg to 400 mg and a daily increase in dose from 25 mg to 100 mg showed, with confirmation on the CPRS, CGI and TESS scales, a significant decrease in anxiety, abnormal use of objects, on the 2nd week of therapy. 3rd week - hyperactivity and depressive affect, by the 4th week - obsessive-compulsive disorders and tics, by the 6th week - the hostility factor was reduced. With regard to psychotic symptoms (paranoid disorders, catatonic inclusions), they showed signs of regression, starting from the 2nd week, and were significantly weakened by the 6th week of therapy. At the same time, quetiapine turned out to be preferable among TN and other AAs (risperidone, olanzapine) due to fewer side effects, especially in the endocrine system [47-54].

At the same time, quetiapine turned out to be preferable among TN and other AAs (risperidone, olanzapine) due to fewer side effects, especially in the endocrine system [47-54].

Treatment of elderly patients with quetiapine has also proven to be justified. Studies have shown that AAs, especially quetiapine 25–100 mg, can be used in elderly patients with psychosis and agitation. The latter does not cause significant neurological disorders and endocrine changes, but its use is limited and should be controlled by indications of the state of the cardiovascular system [55, 56].

Of particular interest is the use of quetiapine in conditions that are not usually the subject of the systematic use of neuroleptics as a main or essential component of treatment. Among these conditions, one can list mild to moderate depressive states, alcoholism, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease.

Double-blind, placebo-controlled studies have shown significant efficacy in more than 60% of cases of quetiapine use in patients with depressive conditions of various etiologies and severity. The results of assessments on the PANSS and CGI scales reliably registered a reduction in depressive disorders not only in the structure of polypharmacological treatment, but also in monotherapy. Moreover, the results indicate that patients with a predominance of depressive disorders over others are more curable, the best response to the drug is given by primary patients, and not those who have been treated with other psychotropic drugs. If the disorders are polymorphic, then patients with congruent depression positive factors (combination of depression with ideas of self-blame and somatic fixation) are treated more successfully than those with a violation of congruent relationships (combination of depression with delusions of grandeur), depressions of mild and moderate registers respond faster to relief than severe ones. . The dosage of quetiapine is 50-300 mg, less often up to 700 mg. The effect occurs on the 2nd week and develops over the next 6-8 weeks. Positive results were also achieved after previous monotherapy with olanzapine and risperidone.

The results of assessments on the PANSS and CGI scales reliably registered a reduction in depressive disorders not only in the structure of polypharmacological treatment, but also in monotherapy. Moreover, the results indicate that patients with a predominance of depressive disorders over others are more curable, the best response to the drug is given by primary patients, and not those who have been treated with other psychotropic drugs. If the disorders are polymorphic, then patients with congruent depression positive factors (combination of depression with ideas of self-blame and somatic fixation) are treated more successfully than those with a violation of congruent relationships (combination of depression with delusions of grandeur), depressions of mild and moderate registers respond faster to relief than severe ones. . The dosage of quetiapine is 50-300 mg, less often up to 700 mg. The effect occurs on the 2nd week and develops over the next 6-8 weeks. Positive results were also achieved after previous monotherapy with olanzapine and risperidone. Compared to, for example, olanzapine, quetiapine had a more pronounced therapeutic effect on depressive states with an acute onset and had a superior anti-relapse effect [57-64].

Compared to, for example, olanzapine, quetiapine had a more pronounced therapeutic effect on depressive states with an acute onset and had a superior anti-relapse effect [57-64].

Influence of taking quetiapine on the cognitive functions of socially dangerous patients with paranoid schizophrenia - Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy named after. P.B. Gannushkin №04 2006

The need for simultaneous correction of productive and negative psychopathological manifestations in patients with schizophrenia, the severity of side effects when taking traditional antipsychotic drugs (dyskinesia, akathisia, perioral tremor, parkinsonian and neuroleptic malignant syndromes), as well as the urgency of the problem of overcoming pharmacotherapeutic resistance lead to the fact that psychiatrists all often used antipsychotics with an atypical mechanism of antipsychotic action. According to the definition given by Meltzer (1996), atypical neuroleptics can be considered such antipsychotic drugs that affect not only productive (hallucinatory-delusional), but also negative (deficiency) symptoms, do not cause extrapyramidal side effects and do not lead to hyperprolactinemia.

Quetiapine belongs to the group of atypical antipsychotics, the pronounced antipsychotic activity of which is based on the ability to block dopamine receptors (D1, D2), especially in the limbic system of the brain (the limbic system is involved in the regulation of sleep and wakefulness phases, autonomic functions of the body, in the control of instinctive and emotional behavior, memory functioning), as well as 5-HT2-serotonergic receptors (blockade of this type of receptor has an anti-anxiety effect, reduces the level of aggression, reduces negative symptoms - aboulia, apathy, autism, reduces depression, improves cognitive functions of the brain, primarily memory) . In our country, studies of the clinical efficacy and safety of quetiapine began at 1998. To date, domestic psychiatrists have obtained and published the results of studies of the efficacy and safety of this drug in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia of various forms and types (paranoid - F20.0, catatonic - F20. 2, undifferentiated - F20.3, residual - F20.5 occurring with a predominance of senesto-hypochondriac disorders - F20.8, including childhood schizophrenia - F20.83), as well as persons suffering from schizotypal disorders (F21), chronic delusional psychoses (F22), schizoaffective disorders (F25), illness Alzheimer's (F00), bipolar disorder (F31).

2, undifferentiated - F20.3, residual - F20.5 occurring with a predominance of senesto-hypochondriac disorders - F20.8, including childhood schizophrenia - F20.83), as well as persons suffering from schizotypal disorders (F21), chronic delusional psychoses (F22), schizoaffective disorders (F25), illness Alzheimer's (F00), bipolar disorder (F31).

It was found that quetiapine does not cause neurological side effects caused by taking most classical antipsychotics, and does not lead to an increase in the level of prolactin and thyroxin in the blood. Already with a short-term (within 6 weeks) use of quetiapine in patients with schizophrenia of various forms (paranoid, catatonic, undifferentiated, residual, occurring with a predominance of senesto-hypochondriac disorders, including childhood schizophrenia), as well as patients with schizotypal and schizoaffective disorders, the drug causes a statistically significant reduction in the severity of psychotic symptoms, both productive and negative. The reduction of productive (hallucinatory-delusional) symptoms in this case is more pronounced and occurs at an earlier date compared to the negative one (a pattern characteristic of all antipsychotics). The results obtained by domestic researchers are in full accordance with the results of international studies on the effectiveness of quetiapine. In addition to the fact that quetiapine is effective in the treatment of schizophrenia, schizotypal and schizoaffective disorders (including children, the elderly and senile), it has also proven effective in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (hallucinatory-delusional, anxiety-phobic symptoms) and bipolar disorder (manic period).

The reduction of productive (hallucinatory-delusional) symptoms in this case is more pronounced and occurs at an earlier date compared to the negative one (a pattern characteristic of all antipsychotics). The results obtained by domestic researchers are in full accordance with the results of international studies on the effectiveness of quetiapine. In addition to the fact that quetiapine is effective in the treatment of schizophrenia, schizotypal and schizoaffective disorders (including children, the elderly and senile), it has also proven effective in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (hallucinatory-delusional, anxiety-phobic symptoms) and bipolar disorder (manic period).

Receiving quetiapine has a significant impact on the emotional-volitional sphere of the personality of patients. From the first days of its use by patients with schizophrenia and persons suffering from schizotypal and schizoaffective disorders, there is a reduction in tension, affective instability, psychomotor agitation, by the 4-6th week of use, there is an increase in the mental activity of patients, a decrease in autism and emotional isolation, weakening of depressive symptoms. The positive effect of quetiapine therapy is found in patients with anxiety-phobic symptoms (quetiapine proved to be the most effective in the treatment of panic disorder; at the same time, manifestations of agora and social phobia, obsessive-compulsive symptom complexes are less affected by quetiapine). The intake of quetiapine causes the extinction of anxiety, tension, agitation, malice and suspicion, a decrease in the level of aggressiveness and emotional isolation in elderly and senile people suffering from demented delusional and hallucinatory psychoses, as well as in people suffering from Alzheimer's disease. Quetiapine is able to stop the manic state within the framework of bipolar disorder, characterized by high spirits, ideational and motor excitement.

The positive effect of quetiapine therapy is found in patients with anxiety-phobic symptoms (quetiapine proved to be the most effective in the treatment of panic disorder; at the same time, manifestations of agora and social phobia, obsessive-compulsive symptom complexes are less affected by quetiapine). The intake of quetiapine causes the extinction of anxiety, tension, agitation, malice and suspicion, a decrease in the level of aggressiveness and emotional isolation in elderly and senile people suffering from demented delusional and hallucinatory psychoses, as well as in people suffering from Alzheimer's disease. Quetiapine is able to stop the manic state within the framework of bipolar disorder, characterized by high spirits, ideational and motor excitement.

There are some scattered data in the literature regarding the effect of taking quetiapine on the cognitive functions of patients. It is known that during therapy with quetiapine in the dose range of 25-100 mg, patients with sluggish neurosis-like schizophrenia show a pronounced improvement in sensorimotor functions (reduction of the latent period of the sensorimotor reaction of choice) and attention functions (increase in volume, productivity) in the absence of improvements in memory functions. With monotherapy with quetiapine at doses of 150-300 mg, the time of a simple sensorimotor reaction also decreases, but the volume and productivity of attention and memory decrease. Thus, the tranquilizing effect of low doses of quetiapine characterizes it as a selective anxiolytic, medium doses - as a sedative anxiolytic. Quetiapine administration reduces cognitive impairment (attention and verbal memory) in elderly and senile patients with schizophrenia, schizotypal and chronic delusional disorders. A positive effect of taking quetiapine on cognitive function has also been noted in individuals suffering from Alzheimer's disease. From foreign sources (M. Riedal, N. Muller, M. Strassnig et al., 2004) it is known that quetiapine has a positive effect on the working memory of patients with schizophrenia, ahead of risperidone in this. At the same time, quetipin does not change the reaction time (does not increase, but does not decrease).

With monotherapy with quetiapine at doses of 150-300 mg, the time of a simple sensorimotor reaction also decreases, but the volume and productivity of attention and memory decrease. Thus, the tranquilizing effect of low doses of quetiapine characterizes it as a selective anxiolytic, medium doses - as a sedative anxiolytic. Quetiapine administration reduces cognitive impairment (attention and verbal memory) in elderly and senile patients with schizophrenia, schizotypal and chronic delusional disorders. A positive effect of taking quetiapine on cognitive function has also been noted in individuals suffering from Alzheimer's disease. From foreign sources (M. Riedal, N. Muller, M. Strassnig et al., 2004) it is known that quetiapine has a positive effect on the working memory of patients with schizophrenia, ahead of risperidone in this. At the same time, quetipin does not change the reaction time (does not increase, but does not decrease).

It is known that the improvement of cognitive functions is one of the factors contributing to the reduction of the social danger of patients. This fact makes it relevant to study the effect of therapy with the atypical neuroleptic seroquel on the cognitive functions of patients with paranoid schizophrenia who have committed socially dangerous acts (SOD) and are under compulsory treatment. In order to clarify the information available in the literature on the effect of quetiapine on the cognitive functions of patients with schizophrenia, the following study was conducted.

This fact makes it relevant to study the effect of therapy with the atypical neuroleptic seroquel on the cognitive functions of patients with paranoid schizophrenia who have committed socially dangerous acts (SOD) and are under compulsory treatment. In order to clarify the information available in the literature on the effect of quetiapine on the cognitive functions of patients with schizophrenia, the following study was conducted.

Research goals and objectives

The aim of the work was to study the effect of taking quetiapine on the cognitive functions of patients with schizophrenia. This goal was specified in the tasks: 1) to investigate the effect of taking quetiapine on the functioning of attention; 2) investigate the effect of taking quetiapine on memory functioning; 3) to investigate the effect of taking quetiapine on the functioning of thinking in patients with paranoid schizophrenia.

Sample characteristic

The study involved 32 people suffering from paranoid schizophrenia with continuous (23 people), episodic with a progressive defect (5 people) and episodic with a stable defect (4 people) types of course (according to ICD-10 F20. 00, F20.01 and F20.02 respectively). All patients are males who have committed OOD and are undergoing compulsory treatment in a specialized psychiatric hospital with intensive supervision. The mechanisms for committing OOD are productive-psychotic (42% of patients) and negative-personal (58%). The age of the subjects at the beginning of quetiapine therapy was 22-49years (average 32.7±5.4 years), the average age of manifestation of schizophrenia was 23.8±4.7 years, the average duration of the disease at the start of quetiapine therapy was 8.6±1.7 years). The length of their stay in a specialized psychiatric hospital with intensive follow-up by the beginning of quetiapine therapy was on average 3.2 ± 0.8 years.

00, F20.01 and F20.02 respectively). All patients are males who have committed OOD and are undergoing compulsory treatment in a specialized psychiatric hospital with intensive supervision. The mechanisms for committing OOD are productive-psychotic (42% of patients) and negative-personal (58%). The age of the subjects at the beginning of quetiapine therapy was 22-49years (average 32.7±5.4 years), the average age of manifestation of schizophrenia was 23.8±4.7 years, the average duration of the disease at the start of quetiapine therapy was 8.6±1.7 years). The length of their stay in a specialized psychiatric hospital with intensive follow-up by the beginning of quetiapine therapy was on average 3.2 ± 0.8 years.

Prior to the appointment of quetiapine, all patients were taking conventional antipsychotics; The main reasons for switching to quetiapine therapy were the lack of efficacy of previous pharmacotherapy and the severity of side effects when taking traditional antipsychotic drugs. Transfer to therapy with quetiapine was carried out by a cross method (within 1 week) or by the method of complete cessation of taking the previous antipsychotic. For each individual patient, the optimal therapeutic dose was selected; the range of therapeutic doses of quetiapine (by the 2nd week of therapy) was from 600 to 800 mg/day; in the future, in 40% of patients, due to the improvement in the state of the dose, they were reduced to maintenance - 150-200 mg / day.

Transfer to therapy with quetiapine was carried out by a cross method (within 1 week) or by the method of complete cessation of taking the previous antipsychotic. For each individual patient, the optimal therapeutic dose was selected; the range of therapeutic doses of quetiapine (by the 2nd week of therapy) was from 600 to 800 mg/day; in the future, in 40% of patients, due to the improvement in the state of the dose, they were reduced to maintenance - 150-200 mg / day.

Methods, procedure for conducting and methods of processing research results

The study of the effect of taking quetiapine on the cognitive functions of patients with paranoid schizophrenia was carried out by measuring shifts under the influence of controlled influences in three main stages: 1) studying the characteristics of the cognitive sphere of patients immediately before quetiapine therapy; 2) study of the features of the cognitive sphere of patients 6-8 months later (on average 7. 2±0.6 months) after the start of quetiapine therapy; 3) comparison of indicators of the cognitive sphere before and after therapy. In order to study the effect of taking quetiapine on the functioning of attention, memory and thinking in patients with paranoid schizophrenia, the following pathopsychological methods were used:

2±0.6 months) after the start of quetiapine therapy; 3) comparison of indicators of the cognitive sphere before and after therapy. In order to study the effect of taking quetiapine on the functioning of attention, memory and thinking in patients with paranoid schizophrenia, the following pathopsychological methods were used:

- Correction test with interference (to study selectivity and stability of attention). A quantitative indicator of selectivity - attention productivity as the speed of choosing a certain stimulus from a set - was calculated using the conditional formula: S=T/m, where S is attention productivity, T is the total time for completing the task, m is the number of allocated stimuli. A qualitative indicator of selectivity - the accuracy of attention as the degree of compliance of the selection results with the initial stimulus material - was calculated using the Whipple formula: A=(N-r)/(N+p), where A is the accuracy of attention, N is the total number of detected stimuli, r is the number of incorrectly detected stimuli, p is the number of missed stimuli.

Attention stability was determined by comparing the indicators of attention selectivity in the conditions of the technique without interference with similar indicators obtained in the conditions of the technique with interference created by the experimenter (listening to the story by the subjects simultaneously with the correction test).

Attention stability was determined by comparing the indicators of attention selectivity in the conditions of the technique without interference with similar indicators obtained in the conditions of the technique with interference created by the experimenter (listening to the story by the subjects simultaneously with the correction test). - Schulte-Gorbov tables (for the study of attention switching). Attention switching coefficients were calculated according to the formula of Yu.G.Stepanov: K=2t 1 /t 2 F.D.Gorbova.

- Memory test 10 words (to determine the volume and effectiveness of short-term and long-term mechanical memory). The indicator of the volume of short-term mechanical memory was the number of words reproduced by the subject in the first trial; an indicator of the effectiveness of short-term mechanical memory - the number of samples required for the subject to fully memorize the series; an indicator of the effectiveness of long-term mechanical memory is the number of words reproduced by the subject 30 minutes after memorizing the series.

- Score with build-up according to V.D. Shadrikov (for the study of RAM). The parameters of RAM efficiency were considered to be the task execution time and the number of errors made.

- "Pictograms" (to study the effectiveness of logical memory, the features of the associative process, the process of abstraction). The parameters of the efficiency of logical memory (mediated memorization) were the number of correctly reproduced and the number of inserted words when reproducing words from pictures 1 hour after the mediation procedure. As parameters of mental activity, indicators of the number of pictograms of various categories were considered - overly abstract associations according to latent features (to identify distortions in the level of generalization), attributive, specific situational (to identify a decrease in the level of generalization) and emotionally saturated (to identify emotional emasculation).

- "Exception" (to determine the level of generalization and abstraction).

As parameters of mental activity, indicators of the number of exceptions (generalization) of different types were considered - according to latent signs (to identify distortions in the level of generalization), according to specific situational signs (to identify a decrease in the level of generalization) and adequate.

As parameters of mental activity, indicators of the number of exceptions (generalization) of different types were considered - according to latent signs (to identify distortions in the level of generalization), according to specific situational signs (to identify a decrease in the level of generalization) and adequate.

Comparison of indicators of cognitive functions of the subjects before and after quetiapine therapy was performed using the Wilcoxon T-test. The results of the pathopsychological examination were supplemented by the results of the observation of the attending psychiatrists, psychotherapists and psychologists working with patients participating in the study.

Description and discussion of results

The data obtained during the study suggest that quetiapine administration has a significant effect on the functioning of the attention of patients with paranoid schizophrenia, improving its properties such as selectivity and switching. Under the influence of quetiapine therapy, the selectivity of attention increases statistically significantly (pJ0.01) both in terms of productivity and accuracy (Table 1).

Under the influence of quetiapine therapy, the selectivity of attention increases statistically significantly (pJ0.01) both in terms of productivity and accuracy (Table 1).

The ability of patients with schizophrenia to switch attention after quetiapine therapy was significantly more developed compared to the pre-therapeutic level (mean coefficients of attention switching were 0.87 and 0.76, respectively; the shift in indicators was significant at pJ0.01). The positive effect of quetiapine therapy on attention functions has already been mentioned by individual researchers (A.S. Avedisova, S.A. Spasova, A.F. Fayzulloev, 2003; V.A. Kontsevoi, A.V. , 2003). At the same time, according to the results of our study, taking quetiapine does not affect the stability of attention in patients with paranoid schizophrenia (Table 2).

Under the influence of quetiapine therapy, the volume (pJ0.01) and efficiency (pJ0.01) of short-term mechanical memory, the efficiency of long-term mechanical memory (pJ0. 05; Table 3), as well as the efficiency of working memory (pJ0.05; Table 4) significantly increase. ). The results of our study of the effect of quetiapine therapy on the functioning of mechanical and operational memory are consistent with the data of some other researchers (V.A. Kontsevoi, A.V. Medvedev, T.P. Safarova, 2003; M. Riedal, N. Muller, M. Strassnig et al., 2004).

05; Table 3), as well as the efficiency of working memory (pJ0.05; Table 4) significantly increase. ). The results of our study of the effect of quetiapine therapy on the functioning of mechanical and operational memory are consistent with the data of some other researchers (V.A. Kontsevoi, A.V. Medvedev, T.P. Safarova, 2003; M. Riedal, N. Muller, M. Strassnig et al., 2004).

The performance indicators of logical memory in patients with paranoid schizophrenia did not change as a result of quetiapine therapy (Table 5).

Logical memory, as is known, is closely connected with the peculiarities of the thought process (primarily the process of abstraction). Our study of the processes of generalization and distraction as the main components of mental activity suggests that taking quetiapine does not significantly affect the analytical and synthetic abilities of patients with paranoid schizophrenia. Thus, the ratio of the number of inadequate (overly abstract in terms of latent features or overly specific in terms of situational features) solutions in the "Pictogram" and "Exclusion" methods did not significantly change as a result of quetiapine therapy (Tables 6, 7).

At the same time, the number of individual emotionally saturated images obtained from patients using the "Pictogram" technique before the start of quetiapine therapy is significantly less than the number of similar images obtained after 6-8 months of therapy (see Table 6). Such changes, apparently, are associated with an increase in the general level of emotionality of patients with schizophrenia under the influence of quetiapine, which is repeatedly mentioned in the literature (I.A. Kozlova, S.N. Masikhina, O.L. Savostyanova, 2003; V.A. Kontsevoi, A.V. Medvedev, T.P. Safarova, 2003). The absence of pronounced changes in the course of thought processes in the presence of distinct changes in the emotional sphere of patients with paranoid schizophrenia is noted by their attending psychiatrists.

Table 2. Change in the mean indicators of attention stability in patients with paranoid schizophrenia during therapy with quetiapine

Productivity

88

88 Table 3. Change in the average indicators of mechanical memory in patients with paranoid schizophrenia during therapy with quetiapine

| Indicator | 3.75 | 5.15 | J0.05 |

Table 4. Change in the average efficiency of working memory in patients with paranoid schizophrenia during quetiapine therapy

| Index | By the beginning of therapy | After 6-8 months of therapy | Significance of shift, p 112 | No |

| Emotionally rich | 20. 0 0 | 32.81 | J0.05 |

Table 7. The ratio of the average percentages of the number of exclusions (generalization) of various categories made in patients with paranoid schizophrenia at the beginning and after 6-8 months of quetiapine therapy

| Exceptions (generalizations) | by the beginning of therapy (verbal version of the methodology) | through 6-8 months of therapy (subject version of the methodology) | The reliability of the shift, p |

| adequate 10 9 | No | ||

| Latent features | 26.60 | 24.62 | No |

| Specific situational features | 38. 80 80 | 36.5 | No The results of the study confirm the information available in the specialized literature on the selectivity of the effect of quetiapine on the cognitive functions of patients with schizophrenia. The study found that taking quetiapine significantly improved selectivity and attention switching; No significant effect on attention span was found. Therapy with quetiapine helps to increase the volume and increase the efficiency of working memory; short-term and long-term mechanical. The data obtained during the study of the effect of taking quetiapine on the functioning of thinking and the logical memory closely related to it suggest that the analytical and synthetic abilities of patients with paranoid schizophrenia are poorly amenable to correction with quetiapine. Nevertheless, the generalization of the data available in the literature on the spectrum of action of quetiapine (good tolerance, the ability to correct both productive and negative psychopathological manifestations, in particular the growth of an emotional defect), analysis of the results of our study of the effect of taking quetiapine on the cognitive functions of patients with schizophrenia allows us to attribute quetiapine among the most effective antipsychotic drugs.  |