Traumatic experience as a child

Recognizing and Treating Child Traumatic Stress

Learn about the signs of traumatic stress, its impact on children, treatment options, and how families and caregivers can help.- Types of Traumatic Events

- Signs of Child Traumatic Stress

- Impact of Child Traumatic Stress

- What Families and Caregivers Can Do to Help

- Treatment for Child Traumatic Stress

- More Ways to Find Help

Types of Traumatic Events

Childhood traumatic stress occurs when violent or dangerous events overwhelm a child’s or adolescent’s ability to cope.

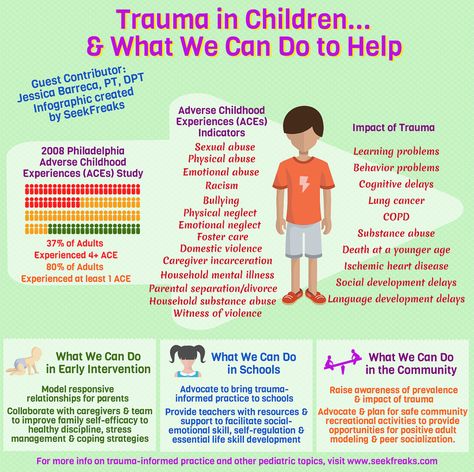

Traumatic events may include:

- Neglect and psychological, physical, or sexual abuse

- Natural disasters, terrorism, and community and school violence

- Witnessing or experiencing intimate partner violence

- Commercial sexual exploitation

- Serious accidents, life-threatening illness, or sudden or violent loss of a loved one

- Refugee and war experiences

- Military family-related stressors, such as parental deployment, loss, or injury

In one nationally representative sample of young people ages 12 to 17:

- 8% reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault

- 17% reported physical assault

- 39% reported witnessing violence

Also, many reported experiencing multiple and repeated traumatic events.

It is important to learn how traumatic events affect children. The more you know, the more you will understand the reasons for certain behaviors and emotions and be better prepared to help children and their families cope. Learn more about the types of trauma and violence and types of disasters.

Signs of Child Traumatic Stress

The signs of traumatic stress are different in each child. Young children react differently than older children.

Preschool Children

- Fearing separation from parents or caregivers

- Crying and/or screaming a lot

- Eating poorly and losing weight

- Having nightmares

Elementary School Children

- Becoming anxious or fearful

- Feeling guilt or shame

- Having a hard time concentrating

- Having difficulty sleeping

Middle and High School Children

- Feeling depressed or alone

- Developing eating disorders and self-harming behaviors

- Beginning to abuse alcohol or drugs

- Becoming sexually active

For some children, these reactions can interfere with daily life and their ability to function and interact with others.

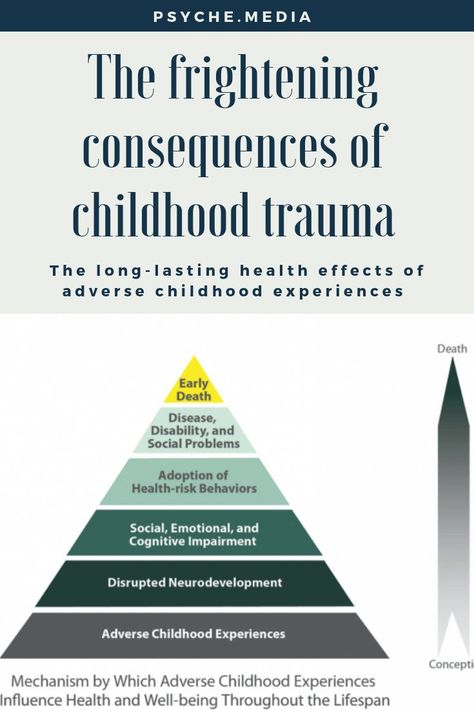

Impact of Child Traumatic Stress

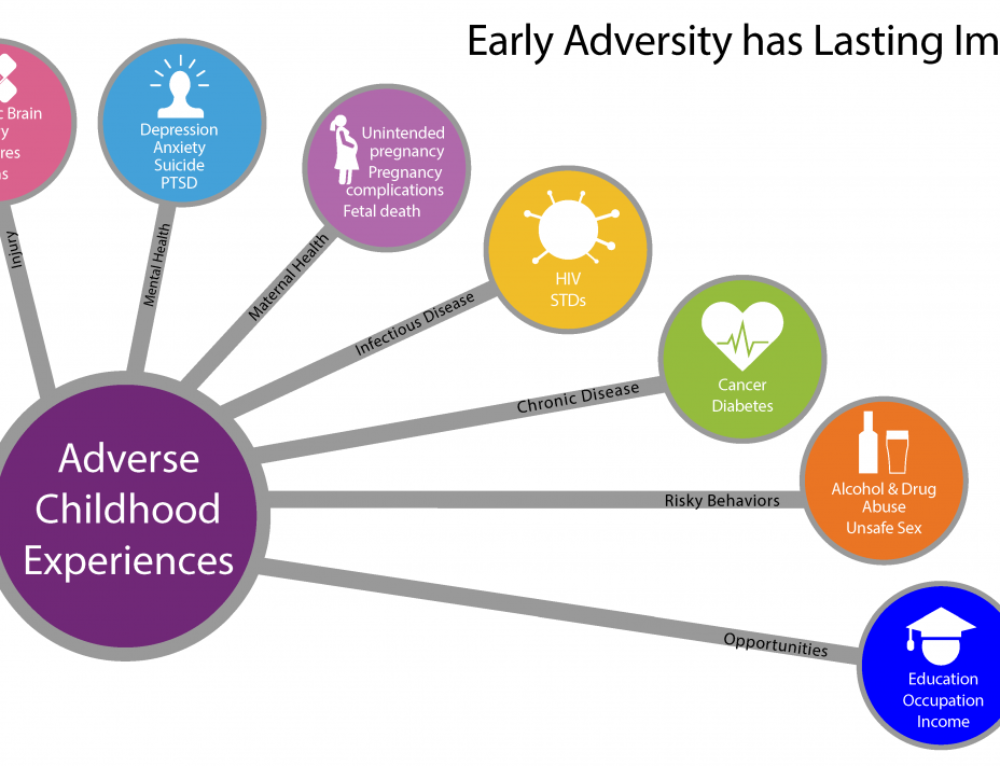

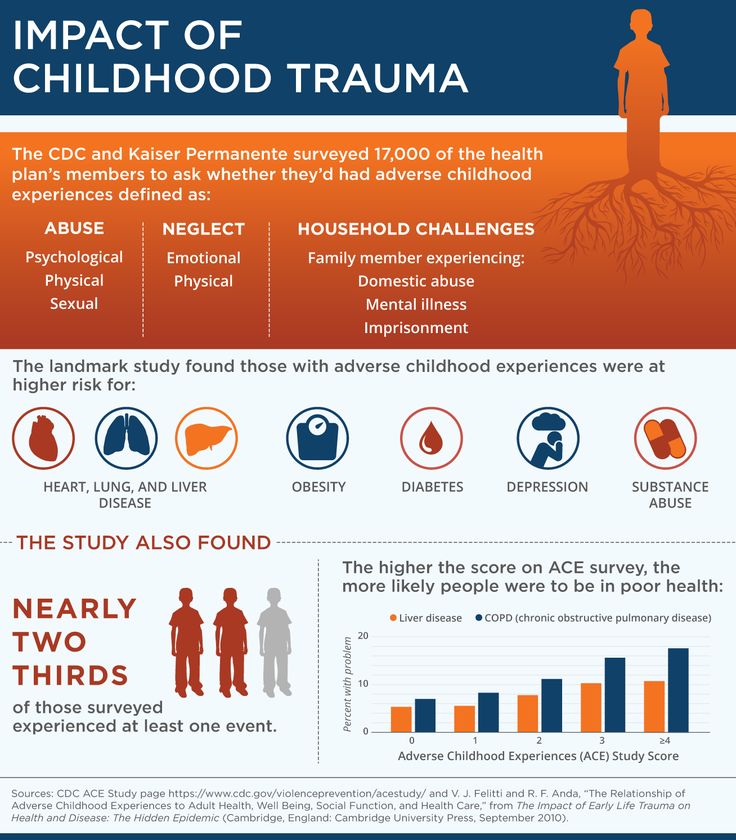

The impact of child traumatic stress can last well beyond childhood. In fact, research shows that child trauma survivors are more likely to have:

- Learning problems, including lower grades and more suspensions and expulsions

- Increased use of health services, including mental health services

- Increased involvement with the child welfare and juvenile justice systems

- Long term health problems, such as diabetes and heart disease

Trauma is a risk factor for nearly all behavioral health and substance use disorders.

What Families and Caregivers Can Do to Help

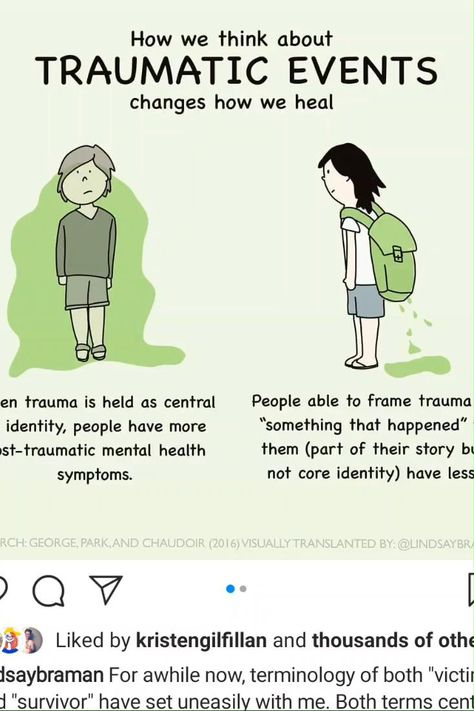

Not all children experience child traumatic stress after experiencing a traumatic event, but those who do can recover. With proper support, many children are able to adapt to and overcome such experiences.

As a family member or other caring adult, you can play an important role. Remember to:

- Assure the child that he or she is safe.

Talk about the measures you are taking to get the child help and keep him or her safe at home and school.

Talk about the measures you are taking to get the child help and keep him or her safe at home and school. - Explain to the child that he or she is not responsible for what happened. Children often blame themselves for events, even those events that are completely out of their control.

- Be patient. There is no correct timetable for healing. Some children will recover quickly. Others recover more slowly. Try to be supportive and reassure the child that he or she does not need to feel guilty or bad about any feelings or thoughts.

Review NCTSI’s learning materials for parents and caregivers, educators and school personnel, health professionals, and others.

Treatment for Child Traumatic Stress

Even with the support of family members and others, some children do not recover on their own. When needed, a mental health professional trained in evidence-based trauma treatment can help children and families cope with the impact of traumatic events and move toward recovery.

Effective treatments like trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapies are available. There are a number of evidence-based and promising practices to address child traumatic stress.

Each child’s treatment depends on the nature, timing, and amount of exposure to a trauma.

Review Effective Treatments for Youth Trauma – 2004 (PDF | 55 KB) at the National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

Families and caregivers should ask their pediatrician, family physician, school counselor, or clergy member for a referral to a mental health professional and discuss available treatment options.

More Ways to Find Help

Many U.S. agencies and other groups offer research and support related to child traumatic stress.

Government Websites

- Division of Violence Prevention and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study at CDC

- Office for Victims of Crime at the Department of Justice

- National Center for PTSD at the Department of Veterans Affairs

- Pediatric Trauma and Critical Illness Branch at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- Coping With Traumatic Events at the National Institute of Mental Health

Other Organizations

- American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children

- Children’s Mental Health Report at the Child Mind Institute

- HealTorture.

org

org - International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies

- National Children's Advocacy Center

- Sidran Institute

About Child Trauma | The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

What Is a Traumatic Event?

A traumatic event is a frightening, dangerous, or violent event that poses a threat to a child’s life or bodily integrity. Witnessing a traumatic event that threatens life or physical security of a loved one can also be traumatic. This is particularly important for young children as their sense of safety depends on the perceived safety of their attachment figures.

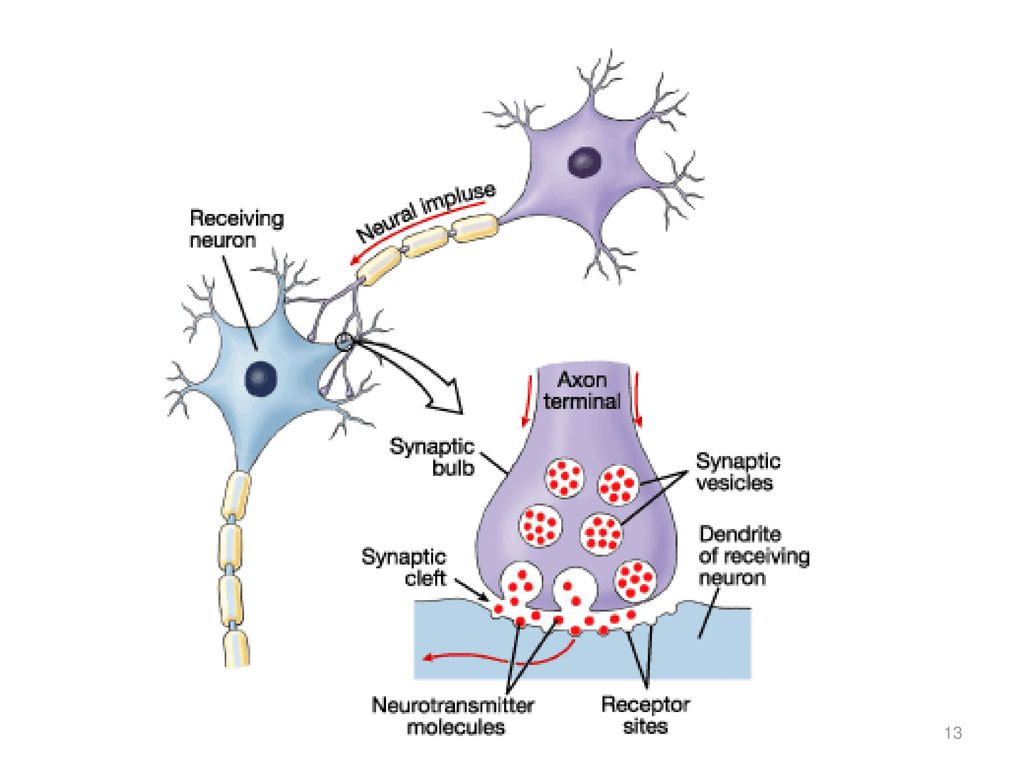

Traumatic experiences can initiate strong emotions and physical reactions that can persist long after the event. Children may feel terror, helplessness, or fear, as well as physiological reactions such as heart pounding, vomiting, or loss of bowel or bladder control. Children who experience an inability to protect themselves or who lacked protection from others to avoid the consequences of the traumatic experience may also feel overwhelmed by the intensity of physical and emotional responses.

Even though adults work hard to keep children safe, dangerous events still happen. This danger can come from outside of the family (such as a natural disaster, car accident, school shooting, or community violence) or from within the family, such as domestic violence, physical or sexual abuse, or the unexpected death of a loved one.

What Experiences Might Be Traumatic?

- Physical, sexual, or psychological abuse and neglect (including trafficking)

- Natural and technological disasters or terrorism

- Family or community violence

- Sudden or violent loss of a loved one

- Substance use disorder (personal or familial)

- Refugee and war experiences (including torture)

- Serious accidents or life-threatening illness

- Military family-related stressors (e.g., deployment, parental loss or injury)

When children have been in situations where they feared for their lives, believed that they would be injured, witnessed violence, or tragically lost a loved one, they may show signs of child traumatic stress.

What Is Child Traumatic Stress?

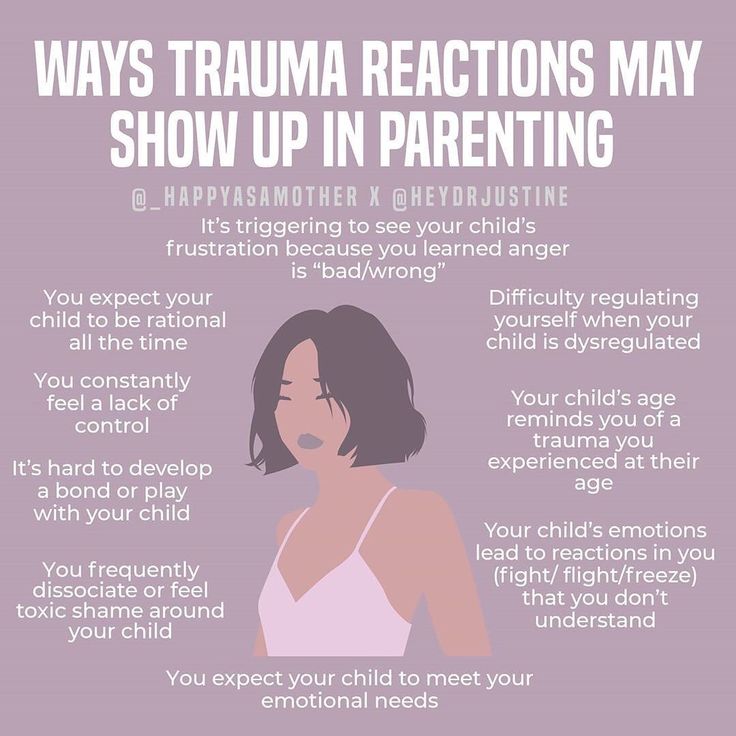

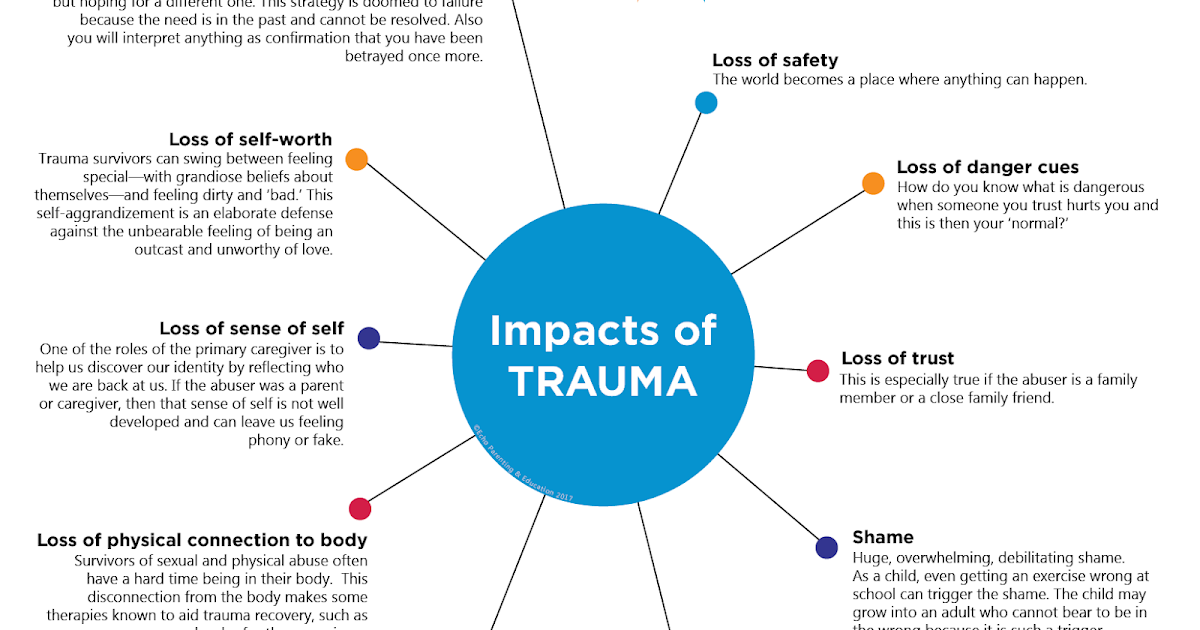

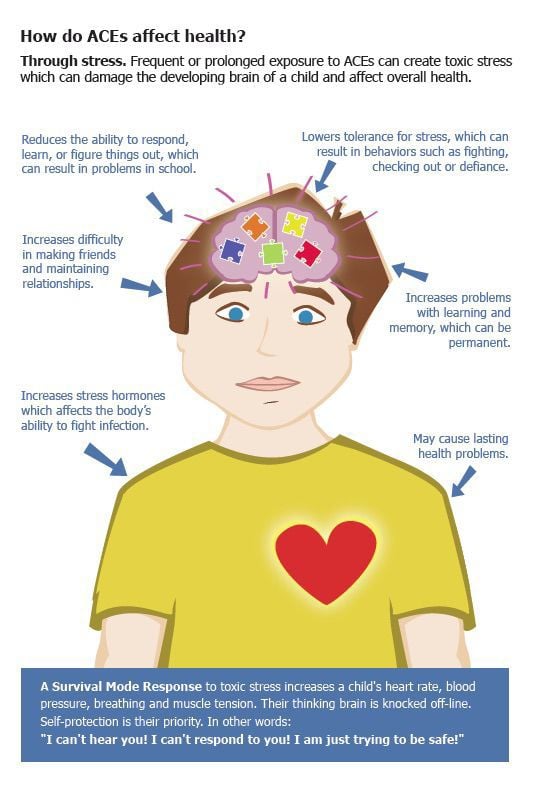

Children who suffer from child traumatic stress are those who have been exposed to one or more traumas over the course of their lives and develop reactions that persist and affect their daily lives after the events have ended. Traumatic reactions can include a variety of responses, such as intense and ongoing emotional upset, depressive symptoms or anxiety, behavioral changes, difficulties with self-regulation, problems relating to others or forming attachments, regression or loss of previously acquired skills, attention and academic difficulties, nightmares, difficulty sleeping and eating, and physical symptoms, such as aches and pains. Older children may use drugs or alcohol, behave in risky ways, or engage in unhealthy sexual activity.

Children who suffer from traumatic stress often have these types of symptoms when reminded in some way of the traumatic event. Although many of us may experience reactions to stress from time to time, when a child is experiencing traumatic stress, these reactions interfere with the child’s daily life and ability to function and interact with others. At no age are children immune to the effects of traumatic experiences. Even infants and toddlers can experience traumatic stress. The way that traumatic stress manifests will vary from child to child and will depend on the child’s age and developmental level.

At no age are children immune to the effects of traumatic experiences. Even infants and toddlers can experience traumatic stress. The way that traumatic stress manifests will vary from child to child and will depend on the child’s age and developmental level.

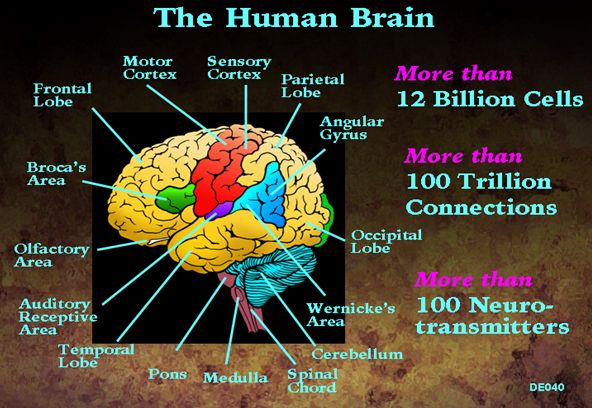

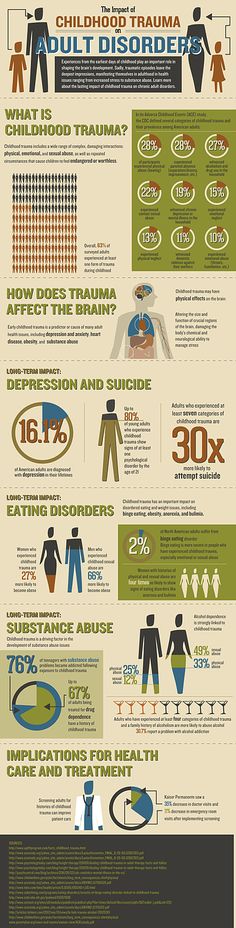

Without treatment, repeated childhood exposure to traumatic events can affect the brain and nervous system and increase health-risk behaviors (e.g., smoking, eating disorders, substance use, and high-risk activities). Research shows that child trauma survivors can be more likely to have long-term health problems (e.g., diabetes and heart disease) or to die at an earlier age. Traumatic stress can also lead to increased use of health and mental health services and increased involvement with the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. Adult survivors of traumatic events may also have difficulty in establishing fulfilling relationships and maintaining employment.

Reminders and Adversities

Traumatic experiences can set in motion a cascade of changes in children’s lives that can be challenging and difficult. These can include changes in where they live, where they attend school, who they’re living with, and their daily routines. They may now be living with injury or disability to themselves or others. There may be ongoing criminal or civil proceedings.

These can include changes in where they live, where they attend school, who they’re living with, and their daily routines. They may now be living with injury or disability to themselves or others. There may be ongoing criminal or civil proceedings.

Traumatic experiences leave a legacy of reminders that may persist for years. These reminders are linked to aspects of the traumatic experience, its circumstances, and its aftermath. Children may be reminded by persons, places, things, situations, anniversaries, or by feelings such as renewed fear or sadness. Physical reactions can also serve as reminders, for example, increased heart rate or bodily sensations. Identifying children’s responses to trauma and loss reminders is an important tool for understanding how and why children’s distress, behavior, and functioning often fluctuate over time. Trauma and loss reminders can reverberate within families, among friends, in schools, and across communities in ways that can powerfully influence the ability of children, families, and communities to recover. Addressing trauma and loss reminders is critical to enhancing ongoing adjustment.

Addressing trauma and loss reminders is critical to enhancing ongoing adjustment.

Risk and Protective Factors

Fortunately, even when children experience a traumatic event, they don’t always develop traumatic stress. Many factors contribute to symptoms, including whether the child has experienced trauma in the past, and protective factors at the child, family, and community levels can reduce the adverse impact of trauma. Some factors to consider include:

- Severity of the event. How serious was the event? How badly was the child or someone she loves physically hurt? Did they or someone they love need to go to the hospital? Were the police involved? Were children separated from their caregivers? Were they interviewed by a principal, police officer, or counselor? Did a friend or family member die?

- Proximity to the event. Was the child actually at the place where the event occurred? Did they see the event happen to someone else or were they a victim? Did the child watch the event on television? Did they hear a loved one talk about what happened?

- Caregivers’ reactions.

Did the child’s family believe that he or she was telling the truth? Did caregivers take the child’s reactions seriously? How did caregivers respond to the child’s needs, and how did they cope with the event themselves?

Did the child’s family believe that he or she was telling the truth? Did caregivers take the child’s reactions seriously? How did caregivers respond to the child’s needs, and how did they cope with the event themselves? - Prior history of trauma. Children continually exposed to traumatic events are more likely to develop traumatic stress reactions.

- Family and community factors. The culture, race, and ethnicity of children, their families, and their communities can be a protective factor, meaning that children and families have qualities and or resources that help buffer against the harmful effects of traumatic experiences and their aftermath. One of these protective factors can be the child’s cultural identity. Culture often has a positive impact on how children, their families, and their communities respond, recover, and heal from a traumatic experience. However, experiences of racism and discrimination can increase a child’s risk for traumatic stress symptoms.

How childhood trauma affects health in old age

A study released July 7 in Aging and Health Research shows that older people who were physically abused as children are twice as likely to others suffer from mood disorders and anxiety disorders. In addition, they are much more likely to suffer from psychosomatic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, diseases of the joints and the cardiovascular system, and cancer.

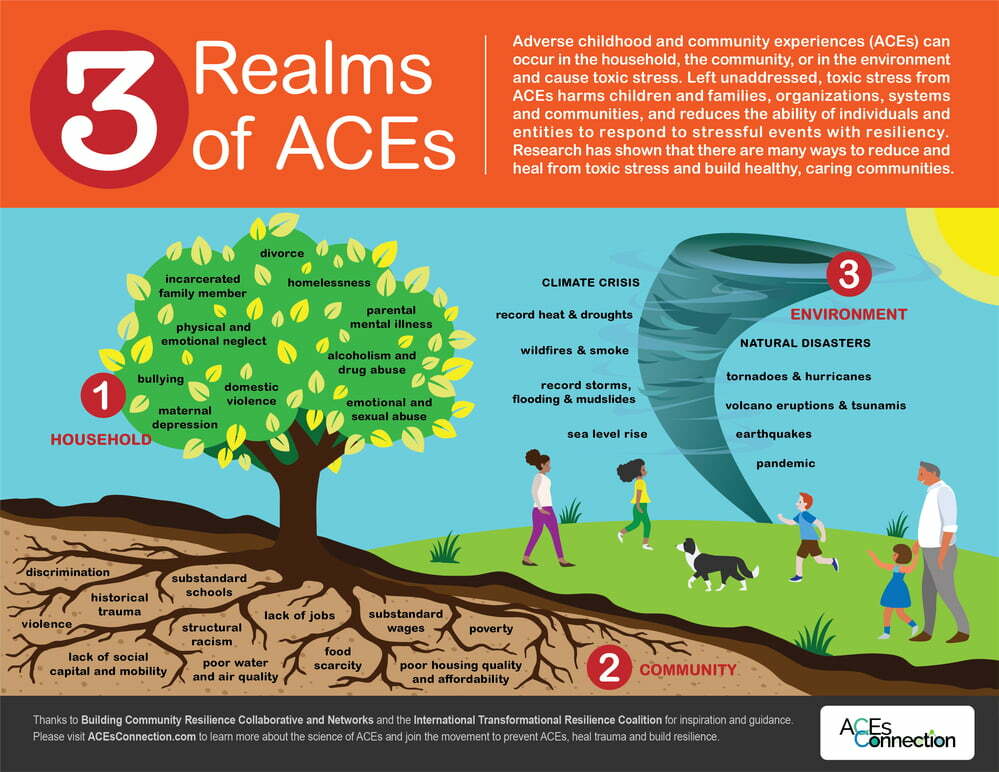

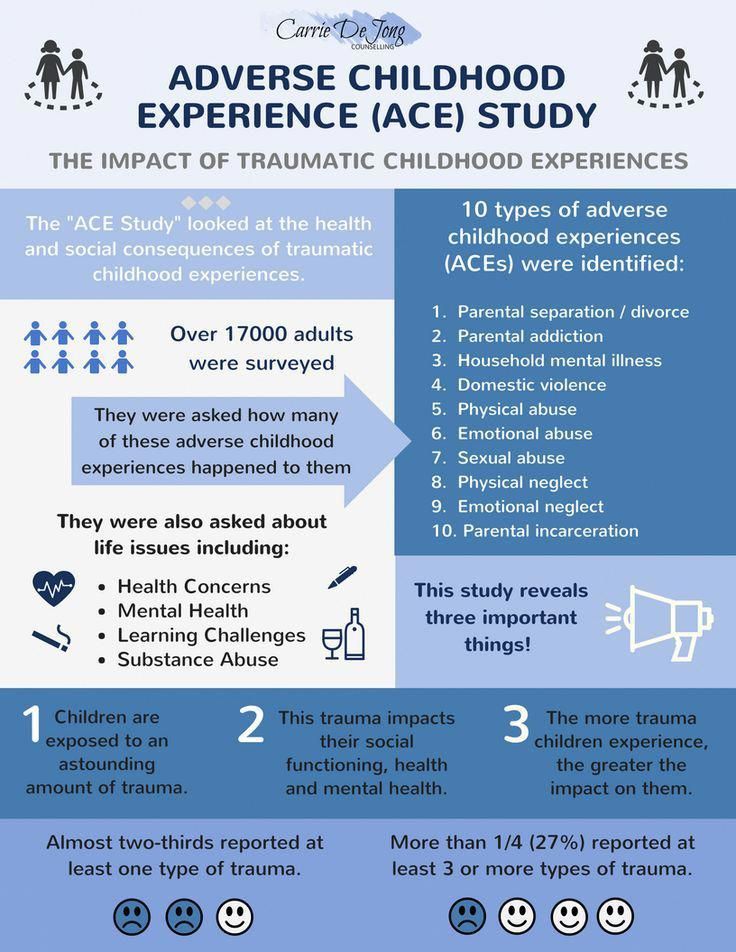

Adverse (traumatic) childhood experiences have been studied since the 1990s as a predictor of ill health throughout life. Most often, traumatic experiences are experienced as parental neglect, rejection, or abuse of an emotional, physical, or sexual nature. Children can also have traumatic life experiences indirectly through their environment, including parental scandals and fights, economic and social difficulties, substance addictions of loved ones, or the presence of a family member with a mental disorder. These negative life experiences have been associated with poor physical and mental health outcomes in adulthood, including stroke, chronic pain, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), migraines, increased levels of anger, suicidal ideation, and completed suicides.

This study included a study of childhood traumatic experiences (primarily physical abuse) and the health status of more than 400 older adults in Canada (British Columbia) to find out if Canadians aged 60+ who experienced childhood physical abuse had worse physical and mental health than their peers. The control group included data from 4,700 elderly Canadians with no negative childhood experiences.

According to statistics, about 7% of adults in Canada suffered physical abuse in childhood. Most conditions associated with childhood abuse have a long latency period (many decades) before they reach the level of a diagnosable disease. Childhood abuse alters the body's ability to recover from stress. Notably, there is a dose-response relationship between the number of episodes of physical abuse in childhood and the likelihood of adverse health outcomes later in life. In turn, the experience of traumatic events can lead to the fact that a person develops coping mechanisms that are harmful to his health. For example, childhood abuse is directly linked to obesity due to overeating and lack of physical activity, tobaccoism and alcoholism. These factors are directly related to health conditions such as cancer, diabetes, and heart disease. In addition, CVD survivors are more likely to experience a decline in socioeconomic status from childhood. Victims of abuse are less likely to successfully complete high school or go to college or university, which limits their future employment opportunities. Thus, the well-established association between lower socioeconomic status and poor health may help explain the prevalence of poor health outcomes among CVD survivors. Moreover, higher divorce rates among survivors of childhood abuse may contribute to poorer health outcomes, as divorce and separation are associated with poorer health in older age. It is also important to note that depression and anxiety often accompany somatic diseases, being somatopsychic disorders. Since these conditions are often present in those who experienced childhood physical abuse, their presence may play a role in the greater likelihood of poor physical health among survivors of adverse cardiovascular events.

For example, childhood abuse is directly linked to obesity due to overeating and lack of physical activity, tobaccoism and alcoholism. These factors are directly related to health conditions such as cancer, diabetes, and heart disease. In addition, CVD survivors are more likely to experience a decline in socioeconomic status from childhood. Victims of abuse are less likely to successfully complete high school or go to college or university, which limits their future employment opportunities. Thus, the well-established association between lower socioeconomic status and poor health may help explain the prevalence of poor health outcomes among CVD survivors. Moreover, higher divorce rates among survivors of childhood abuse may contribute to poorer health outcomes, as divorce and separation are associated with poorer health in older age. It is also important to note that depression and anxiety often accompany somatic diseases, being somatopsychic disorders. Since these conditions are often present in those who experienced childhood physical abuse, their presence may play a role in the greater likelihood of poor physical health among survivors of adverse cardiovascular events.

University of Toronto Life Cycle and Aging Institute researcher Anna Burmann stresses the need to account for traumatic childhood experiences in patients of all ages in order to more accurately predict the course and outcome of physical and mental illness. Given the high prevalence of physical abuse against children, supporting survivors of childhood trauma is an important priority for governments and health systems working to ensure the well-being of older people. The high rates of mental illness that have been found in older survivors of childhood abuse further highlight the importance of timely mental health interventions for this population, such as providing counseling or other psychological care related to child abuse. Victim-focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (AF-CBT) has been shown to improve behavioral and emotional outcomes in child victims of abuse and is the recommended treatment for this population. Similarly, cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to reduce symptom severity and improve social, cognitive, and emotional functioning in CVD survivors. Trauma-focused psychological interventions, cognitive behavioral therapy, and others are also effective in treating symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults who experienced childhood physical and sexual abuse. Because CBT interventions remain widely unavailable to older people, expanding access to these treatments could help improve their mental health outcomes and survival from medical illnesses.

Trauma-focused psychological interventions, cognitive behavioral therapy, and others are also effective in treating symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults who experienced childhood physical and sexual abuse. Because CBT interventions remain widely unavailable to older people, expanding access to these treatments could help improve their mental health outcomes and survival from medical illnesses.

More research is needed to determine whether timely and effective psychological interventions to address the mental health consequences of childhood abuse will reduce physical health problems in adulthood and old age.

Adapted from Health Day.com

Impact of early childhood trauma on adult life

Author: Claudia M. Elsig, MD

The trauma that a child receives in the first years of life is often underestimated and completely ignored: after all, if a child cannot describe an event or series of events, or remember them, do they have meaning? The answer is, of course, yes.

About half of children experience some form of trauma at an early age. For some, the traumatic event goes unnoticed, but for others, it can have lifelong consequences. Stress, which even newborns experience, can subsequently affect mental and physical health.

What does childhood trauma mean?

It can start during pregnancy. When an expectant mother encounters stress or trauma, it is imprinted in the child's memory in a pathological way, in addition to physiological problems and low birth weight. Combined with an epigenetic predisposition to emotional and physiological abnormalities, stress during pregnancy can be an additional piece of the puzzle in unraveling the roots of problems.

In addition, various types of events that can be traumatic in early childhood are referred to as adverse childhood experiences (ACH). They include 1 :

- Physical abuse

- Psychological abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Parental abandonment of a child or loss of parents due to suicide

- Neglect

- Domestic drug or alcohol abuse

- Natural disaster or accident

- Constant stress (bullying, life in a dangerous situation)

- Near death experience

Why does it affect some and not others?

Stress is subjective: if the child is surrounded by love and caress, feels protected and generally supported, the effects of stress can be countered by positive factors.

Children also differ in their perception: what hurts one does not necessarily hurt another. Several factors are involved, including genetic predisposition, family support, and previous trauma experience. 2 .

Moreover, some tolerable stress is needed at an early stage for the child to learn to cope with it. However, a prolonged period of stress can lead to disruption of the architecture of the brain and cause long-term harm if left untreated.

What are the consequences of neonatal stress in adulthood?

Some injuries can leave scars on a person, especially if left untreated in childhood. Excess NDP can lead to toxic stress, a body reaction that alters the human brain and nervous system, metabolism, immune and cardiovascular systems.

Physical effects

Some of the physical effects of exposure to early life stress include increased risk of heart and lung disease, diabetes 3 , liver disease and cancer. Autoimmune disorders and stroke, as well as high stress levels in general, are more likely in adults who experienced prolonged childhood stress or trauma. 4 .

4 .

Emotional consequences

Mental health is also affected by prolonged stress or traumatic events, and some of the consequences for adults who have experienced early childhood trauma may include:

- Anger problems

- Depression or anxiety

- Increased stress level

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Psychosis

- High risk of suicide attempts

- Alcohol abuse or other addictions

- Self-destructive behavior

Consequences of childhood stress and trauma

The consequences of trauma, even if the adult does not remember it, can be detrimental. People who have experienced trauma at an early age are less likely to have satisfying relationships as adults. They are reluctant to trust others and have difficulty forming deep relationships. Many of the difficulties they face, such as low self-esteem, difficulty solving problems, disturbed sleep, inability to plan, or heightened anger, go back deep into childhood. They affect both our interpersonal relationships and career success.

They affect both our interpersonal relationships and career success.

Moreover, adults who have untreated negative childhood experiences are sometimes reluctant to form families because they are more likely to expose their children to NDP.

Attachment styles and attitudes

When an infant is not properly cared for, the child may develop an attachment disorder that persists into adulthood.

In fact, some research has shown that the type of attachment a toddler has for his caregiver, that is, how responsive his caregiver is to his needs, is one of the most important indicators of the relationship style a child will have in adulthood.

For example, a securely attached child will have a healthy and secure relationship. At the same time, a child who is often ignored or neglected is likely to have difficulty establishing close relationships and is likely to avoid emotional intimacy. 3 . A child who has been rejected by a caregiver with a nervous attachment type will constantly be afraid that the partner will leave him, and will spend his time analyzing his relationship instead of participating in it.

Exposure to early trauma in adulthood

It is not uncommon to experience the consequences of LPT in later life. Trauma can manifest through anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder. In cases of child abandonment and neglect, physical or sexual abuse, mental illness or substance abuse in the family, if childhood trauma affects your adult life - this needs to be worked on, even if you do not have specific memories of this period.

Good sleep and healthy eating, and avoiding smoking and drinking, together with lifestyle choices such as exercise, meditation, and participation in support groups, can be helpful. However, nothing gives such an effect as complex treatment by qualified specialists.

… with the help of the CALDA Clinic

For years, childhood trauma can lurk in the depths of your psyche, sometimes manifesting itself in your psychological and physiological reactions. We provide a personalized approach based on your experience and history while addressing your physical and emotional needs, using the best practices of both Eastern and Western medicine. Regardless of the severity of your early childhood trauma, our goal is to help you heal as quickly as possible.

Regardless of the severity of your early childhood trauma, our goal is to help you heal as quickly as possible.

It's never too late to get help, and if you're looking for help, you're well on your way to getting answers to your questions.

Reference books

- State Child Traumatic Stress Network. “Early childhood trauma.”/The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. “Early Childhood Trauma.” https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-types/early-childhood-trauma

- American Academy of Pediatrics. "Adverse Childhood Experiences and Traumatic Consequences"/American Academy of Pediatrics. “Adverse childhood experiences and the lifelong consequences of trauma.” 2014. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.ncpeds.org/resource/collection/69DEAA33-A258-493B-A63F-E0BFAB6BD2CB/ttb_aces_consequences.pdf

- Van der Kolk, Bessel A. The Body Keeps the Record: Brain, Mind and Body in Healing Trauma. /The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma .