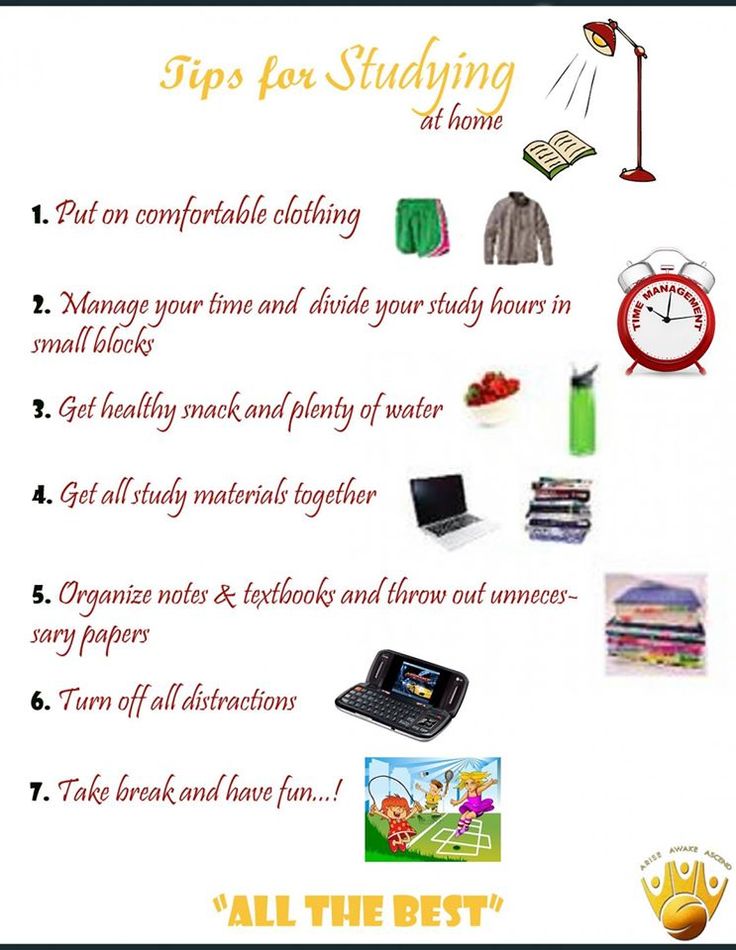

Good study tips

Study Smarter Not Harder – Learning Center

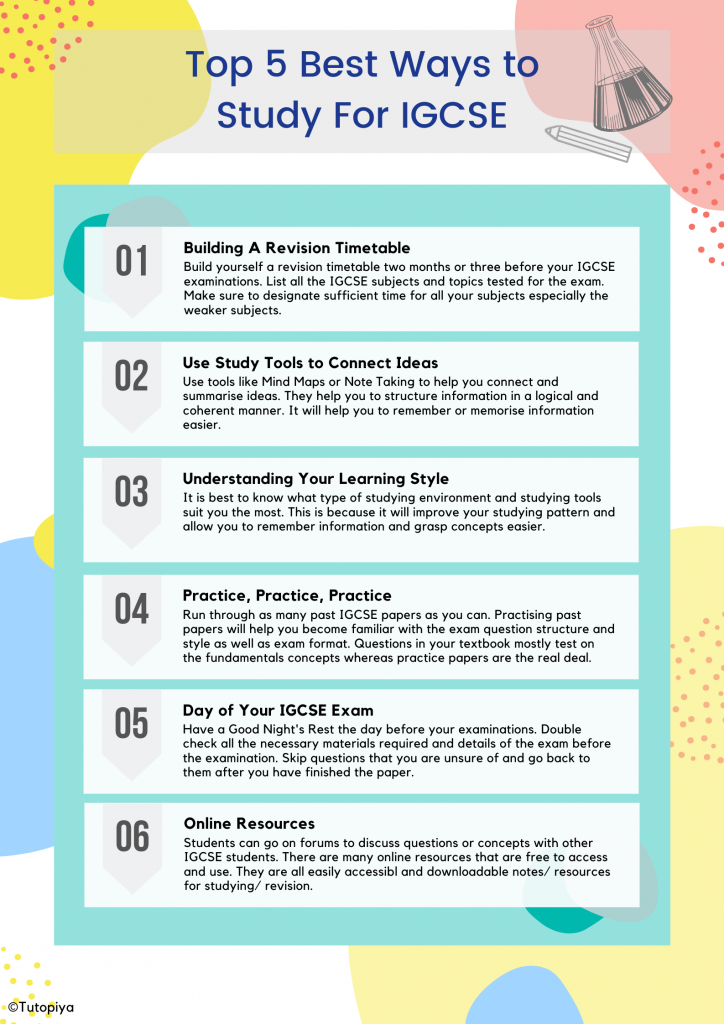

Do you ever feel like your study habits simply aren’t cutting it? Do you wonder what you could be doing to perform better in class and on exams? Many students realize that their high school study habits aren’t very effective in college. This is understandable, as college is quite different from high school. The professors are less personally involved, classes are bigger, exams are worth more, reading is more intense, and classes are much more rigorous. That doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with you; it just means you need to learn some more effective study skills. Fortunately, there are many active, effective study strategies that are shown to be effective in college classes.

This handout offers several tips on effective studying. Implementing these tips into your regular study routine will help you to efficiently and effectively learn course material. Experiment with them and find some that work for you.

Reading is not studying

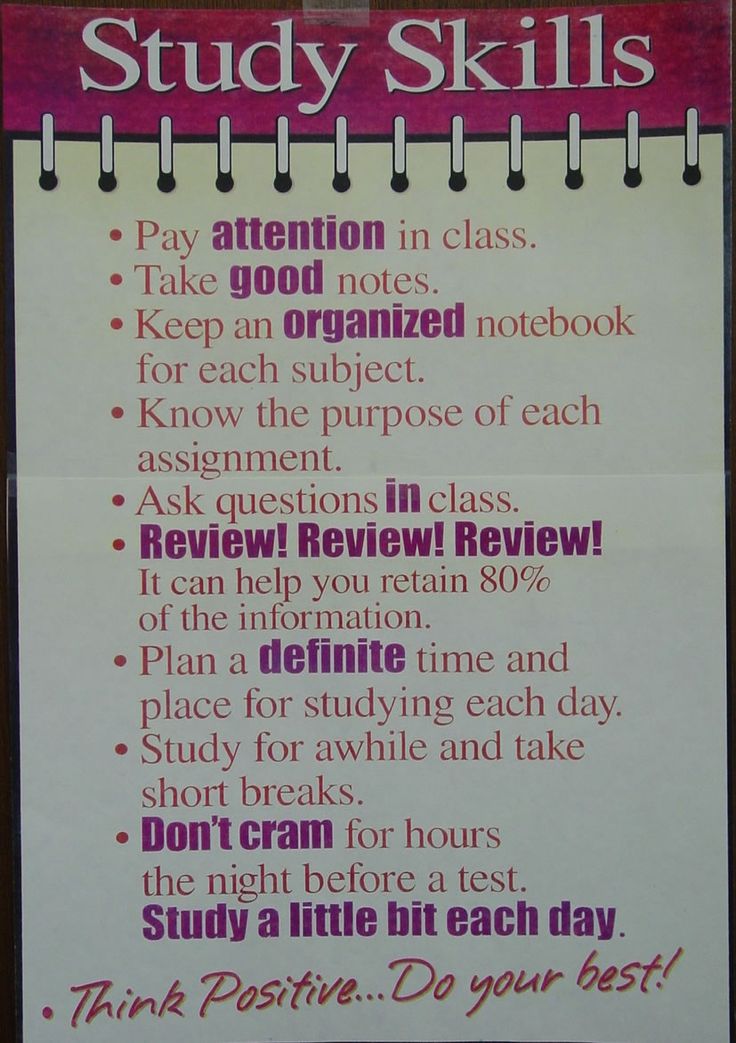

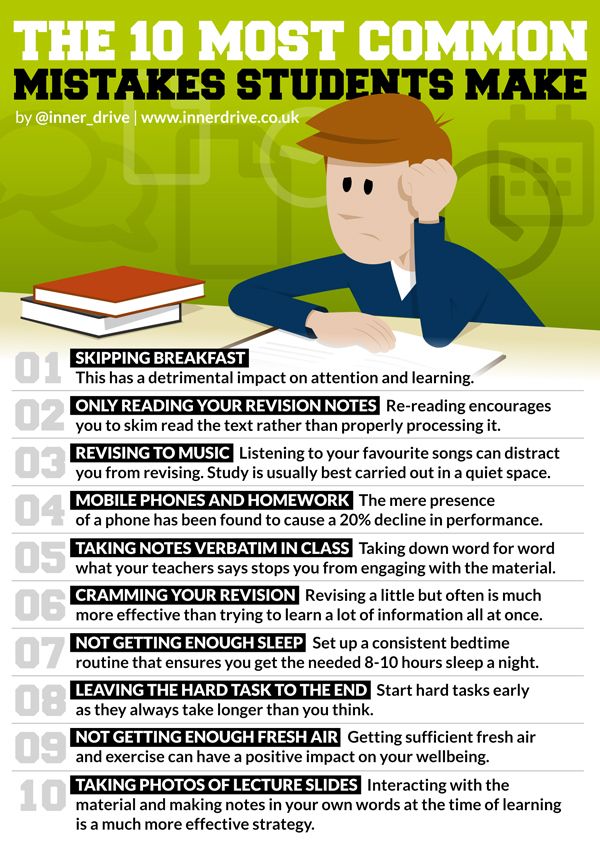

Simply reading and re-reading texts or notes is not actively engaging in the material. It is simply re-reading your notes. Only ‘doing’ the readings for class is not studying. It is simply doing the reading for class. Re-reading leads to quick forgetting.

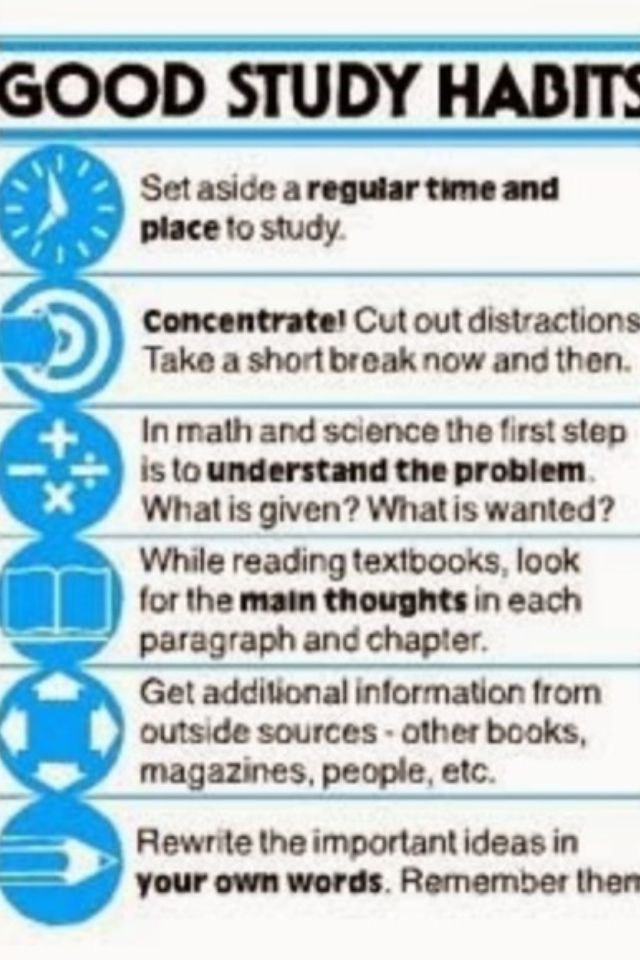

Think of reading as an important part of pre-studying, but learning information requires actively engaging in the material (Edwards, 2014). Active engagement is the process of constructing meaning from text that involves making connections to lectures, forming examples, and regulating your own learning (Davis, 2007). Active studying does not mean highlighting or underlining text, re-reading, or rote memorization. Though these activities may help to keep you engaged in the task, they are not considered active studying techniques and are weakly related to improved learning (Mackenzie, 1994).

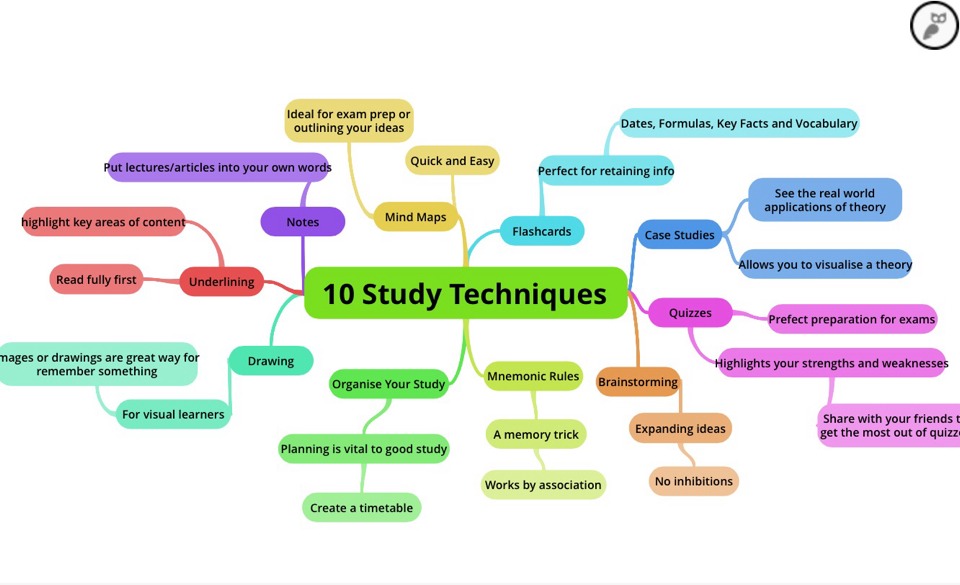

Ideas for active studying include:

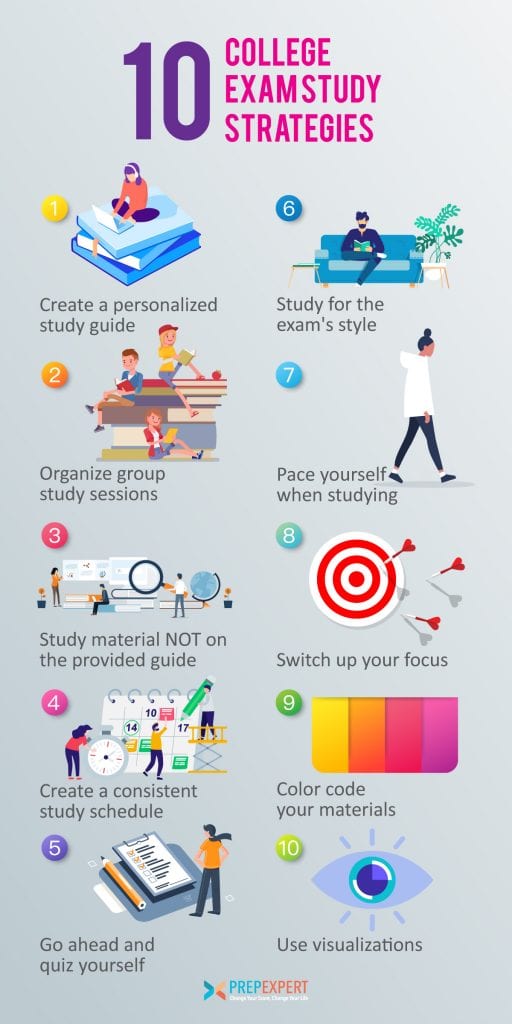

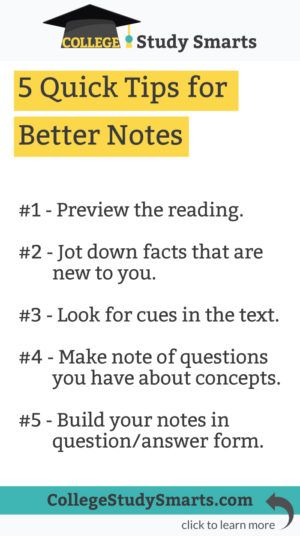

- Create a study guide by topic. Formulate questions and problems and write complete answers. Create your own quiz.

- Become a teacher. Say the information aloud in your own words as if you are the instructor and teaching the concepts to a class.

- Derive examples that relate to your own experiences.

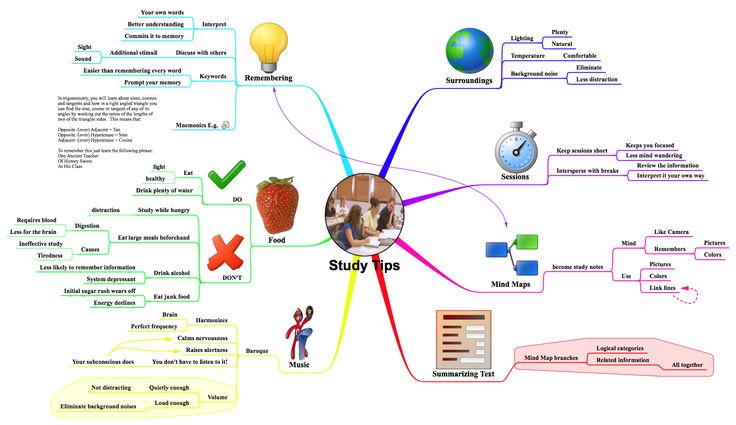

- Create concept maps or diagrams that explain the material.

- Develop symbols that represent concepts.

- For non-technical classes (e.g., English, History, Psychology), figure out the big ideas so you can explain, contrast, and re-evaluate them.

- For technical classes, work the problems and explain the steps and why they work.

- Study in terms of question, evidence, and conclusion: What is the question posed by the instructor/author? What is the evidence that they present? What is the conclusion?

Organization and planning will help you to actively study for your courses. When studying for a test, organize your materials first and then begin your active reviewing by topic (Newport, 2007). Often professors provide subtopics on the syllabi. Use them as a guide to help organize your materials. For example, gather all of the materials for one topic (e.g., PowerPoint notes, text book notes, articles, homework, etc. ) and put them together in a pile. Label each pile with the topic and study by topics.

) and put them together in a pile. Label each pile with the topic and study by topics.

For more information on the principle behind active studying, check out our tipsheet on metacognition.

Understand the Study Cycle

The Study Cycle, developed by Frank Christ, breaks down the different parts of studying: previewing, attending class, reviewing, studying, and checking your understanding. Although each step may seem obvious at a glance, all too often students try to take shortcuts and miss opportunities for good learning. For example, you may skip a reading before class because the professor covers the same material in class; doing so misses a key opportunity to learn in different modes (reading and listening) and to benefit from the repetition and distributed practice (see #3 below) that you’ll get from both reading ahead and attending class. Understanding the importance of all stages of this cycle will help make sure you don’t miss opportunities to learn effectively.

Spacing out is good

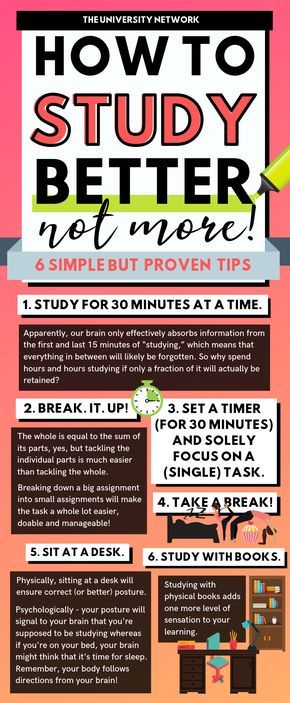

One of the most impactful learning strategies is “distributed practice”—spacing out your studying over several short periods of time over several days and weeks (Newport, 2007). The most effective practice is to work a short time on each class every day. The total amount of time spent studying will be the same (or less) than one or two marathon library sessions, but you will learn the information more deeply and retain much more for the long term—which will help get you an A on the final. The important thing is how you use your study time, not how long you study. Long study sessions lead to a lack of concentration and thus a lack of learning and retention.

In order to spread out studying over short periods of time across several days and weeks, you need control over your schedule. Keeping a list of tasks to complete on a daily basis will help you to include regular active studying sessions for each class. Try to do something for each class each day. Be specific and realistic regarding how long you plan to spend on each task—you should not have more tasks on your list than you can reasonably complete during the day.

Be specific and realistic regarding how long you plan to spend on each task—you should not have more tasks on your list than you can reasonably complete during the day.

For example, you may do a few problems per day in math rather than all of them the hour before class. In history, you can spend 15-20 minutes each day actively studying your class notes. Thus, your studying time may still be the same length, but rather than only preparing for one class, you will be preparing for all of your classes in short stretches. This will help focus, stay on top of your work, and retain information.

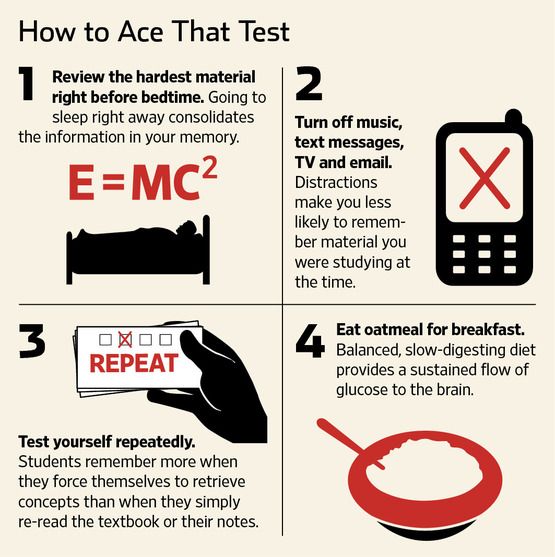

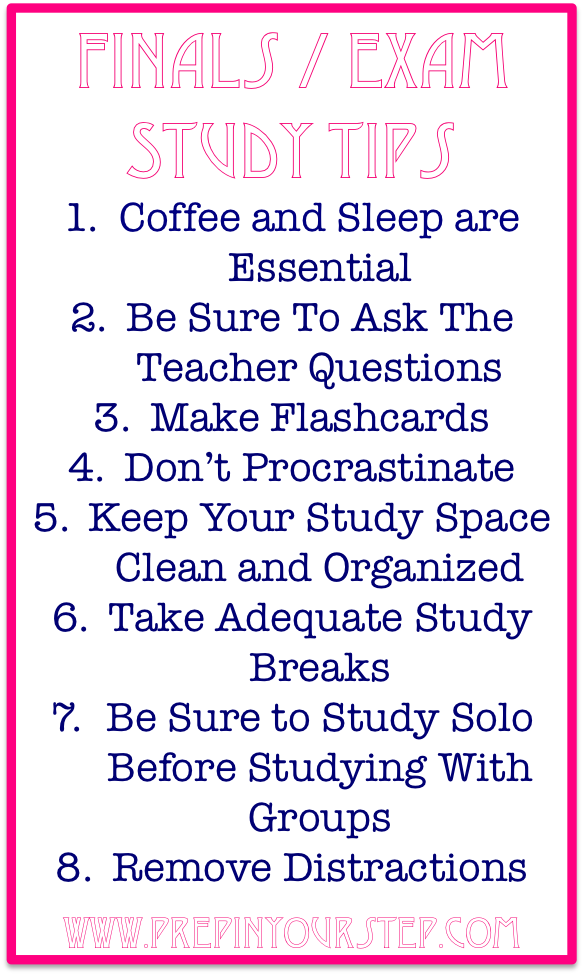

In addition to learning the material more deeply, spacing out your work helps stave off procrastination. Rather than having to face the dreaded project for four hours on Monday, you can face the dreaded project for 30 minutes each day. The shorter, more consistent time to work on a dreaded project is likely to be more acceptable and less likely to be delayed to the last minute. Finally, if you have to memorize material for class (names, dates, formulas), it is best to make flashcards for this material and review periodically throughout the day rather than one long, memorization session (Wissman and Rawson, 2012). See our handout on memorization strategies to learn more.

See our handout on memorization strategies to learn more.

It’s good to be intense

Not all studying is equal. You will accomplish more if you study intensively. Intensive study sessions are short and will allow you to get work done with minimal wasted effort. Shorter, intensive study times are more effective than drawn out studying.

In fact, one of the most impactful study strategies is distributing studying over multiple sessions (Newport, 2007). Intensive study sessions can last 30 or 45-minute sessions and include active studying strategies. For example, self-testing is an active study strategy that improves the intensity of studying and efficiency of learning. However, planning to spend hours on end self-testing is likely to cause you to become distracted and lose your attention.

On the other hand, if you plan to quiz yourself on the course material for 45 minutes and then take a break, you are much more likely to maintain your attention and retain the information. Furthermore, the shorter, more intense sessions will likely put the pressure on that is needed to prevent procrastination.

Furthermore, the shorter, more intense sessions will likely put the pressure on that is needed to prevent procrastination.

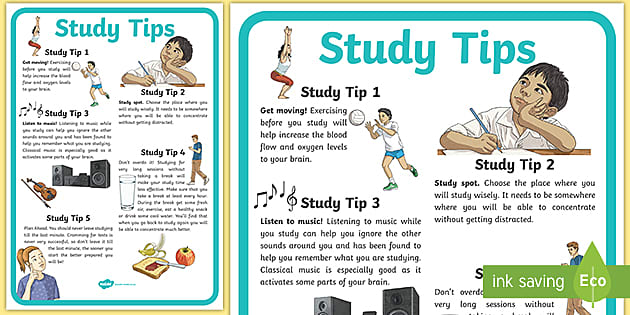

Silence isn’t golden

Know where you study best. The silence of a library may not be the best place for you. It’s important to consider what noise environment works best for you. You might find that you concentrate better with some background noise. Some people find that listening to classical music while studying helps them concentrate, while others find this highly distracting. The point is that the silence of the library may be just as distracting (or more) than the noise of a gymnasium. Thus, if silence is distracting, but you prefer to study in the library, try the first or second floors where there is more background ‘buzz.’

Keep in mind that active studying is rarely silent as it often requires saying the material aloud.

Problems are your friend

Working and re-working problems is important for technical courses (e.g., math, economics). Be able to explain the steps of the problems and why they work.

Be able to explain the steps of the problems and why they work.

In technical courses, it is usually more important to work problems than read the text (Newport, 2007). In class, write down in detail the practice problems demonstrated by the professor. Annotate each step and ask questions if you are confused. At the very least, record the question and the answer (even if you miss the steps).

When preparing for tests, put together a large list of problems from the course materials and lectures. Work the problems and explain the steps and why they work (Carrier, 2003).

Reconsider multitasking

A significant amount of research indicates that multi-tasking does not improve efficiency and actually negatively affects results (Junco, 2012).

In order to study smarter, not harder, you will need to eliminate distractions during your study sessions. Social media, web browsing, game playing, texting, etc. will severely affect the intensity of your study sessions if you allow them! Research is clear that multi-tasking (e. g., responding to texts, while studying), increases the amount of time needed to learn material and decreases the quality of the learning (Junco, 2012).

g., responding to texts, while studying), increases the amount of time needed to learn material and decreases the quality of the learning (Junco, 2012).

Eliminating the distractions will allow you to fully engage during your study sessions. If you don’t need your computer for homework, then don’t use it. Use apps to help you set limits on the amount of time you can spend at certain sites during the day. Turn your phone off. Reward intensive studying with a social-media break (but make sure you time your break!) See our handout on managing technology for more tips and strategies.

Switch up your setting

Find several places to study in and around campus and change up your space if you find that it is no longer a working space for you.

Know when and where you study best. It may be that your focus at 10:00 PM. is not as sharp as at 10:00 AM. Perhaps you are more productive at a coffee shop with background noise, or in the study lounge in your residence hall. Perhaps when you study on your bed, you fall asleep.

Have a variety of places in and around campus that are good study environments for you. That way wherever you are, you can find your perfect study spot. After a while, you might find that your spot is too comfortable and no longer is a good place to study, so it’s time to hop to a new spot!

Become a teacher

Try to explain the material in your own words, as if you are the teacher. You can do this in a study group, with a study partner, or on your own. Saying the material aloud will point out where you are confused and need more information and will help you retain the information. As you are explaining the material, use examples and make connections between concepts (just as a teacher does). It is okay (even encouraged) to do this with your notes in your hands. At first you may need to rely on your notes to explain the material, but eventually you’ll be able to teach it without your notes.

Creating a quiz for yourself will help you to think like your professor. What does your professor want you to know? Quizzing yourself is a highly effective study technique. Make a study guide and carry it with you so you can review the questions and answers periodically throughout the day and across several days. Identify the questions that you don’t know and quiz yourself on only those questions. Say your answers aloud. This will help you to retain the information and make corrections where they are needed. For technical courses, do the sample problems and explain how you got from the question to the answer. Re-do the problems that give you trouble. Learning the material in this way actively engages your brain and will significantly improve your memory (Craik, 1975).

What does your professor want you to know? Quizzing yourself is a highly effective study technique. Make a study guide and carry it with you so you can review the questions and answers periodically throughout the day and across several days. Identify the questions that you don’t know and quiz yourself on only those questions. Say your answers aloud. This will help you to retain the information and make corrections where they are needed. For technical courses, do the sample problems and explain how you got from the question to the answer. Re-do the problems that give you trouble. Learning the material in this way actively engages your brain and will significantly improve your memory (Craik, 1975).

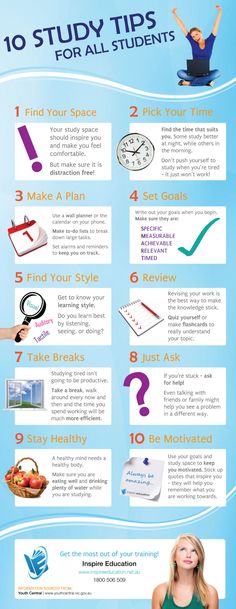

Take control of your calendar

Controlling your schedule and your distractions will help you to accomplish your goals.

If you are in control of your calendar, you will be able to complete your assignments and stay on top of your coursework. The following are steps to getting control of your calendar:

- On the same day each week, (perhaps Sunday nights or Saturday mornings) plan out your schedule for the week.

- Go through each class and write down what you’d like to get completed for each class that week.

- Look at your calendar and determine how many hours you have to complete your work.

- Determine whether your list can be completed in the amount of time that you have available. (You may want to put the amount of time expected to complete each assignment.) Make adjustments as needed. For example, if you find that it will take more hours to complete your work than you have available, you will likely need to triage your readings. Completing all of the readings is a luxury. You will need to make decisions about your readings based on what is covered in class. You should read and take notes on all of the assignments from the favored class source (the one that is used a lot in the class). This may be the textbook or a reading that directly addresses the topic for the day. You can likely skim supplemental readings.

- Pencil into your calendar when you plan to get assignments completed.

- Before going to bed each night, make your plan for the next day. Waking up with a plan will make you more productive.

See our handout on calendars and college for more tips on using calendars as time management.

Use downtime to your advantage

Beware of ‘easy’ weeks. This is the calm before the storm. Lighter work weeks are a great time to get ahead on work or to start long projects. Use the extra hours to get ahead on assignments or start big projects or papers. You should plan to work on every class every week even if you don’t have anything due. In fact, it is preferable to do some work for each of your classes every day. Spending 30 minutes per class each day will add up to three hours per week, but spreading this time out over six days is more effective than cramming it all in during one long three-hour session. If you have completed all of the work for a particular class, then use the 30 minutes to get ahead or start a longer project.

Use all your resources

Remember that you can make an appointment with an academic coach to work on implementing any of the strategies suggested in this handout.

Works consulted

Carrier, L. M. (2003). College students’ choices of study strategies. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 96(1), 54-56.

Craik, F. I., & Tulving, E. (1975). Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 104(3), 268.

Davis, S. G., & Gray, E. S. (2007). Going beyond test-taking strategies: Building self-regulated students and teachers. Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 1(1), 31-47.

Edwards, A. J., Weinstein, C. E., Goetz, E. T., & Alexander, P. A. (2014). Learning and study strategies: Issues in assessment, instruction, and evaluation. Elsevier.

Junco, R., & Cotten, S. R. (2012). No A 4 U: The relationship between multitasking and academic performance. Computers & Education, 59(2), 505-514.

Mackenzie, A. M. (1994). Examination preparation, anxiety and examination performance in a group of adult students. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 13(5), 373-388.

International Journal of Lifelong Education, 13(5), 373-388.

McGuire, S.Y. & McGuire, S. (2016). Teach Students How to Learn: Strategies You Can Incorporate in Any Course to Improve Student Metacognition, Study Skills, and Motivation. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Newport, C. (2006). How to become a straight-a student: the unconventional strategies real college students use to score high while studying less. Three Rivers Press.

Paul, K. (1996). Study smarter, not harder. Self Counsel Press.

Robinson, A. (1993). What smart students know: maximum grades, optimum learning, minimum time. Crown trade paperbacks.

Wissman, K. T., Rawson, K. A., & Pyc, M. A. (2012). How and when do students use flashcards? Memory, 20, 568-579.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Learning Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

If you enjoy using our handouts, we appreciate contributions of acknowledgement.

Make a Gift

The Study Cycle – Learning Center

Do you have trouble building study time into your schedule? Do you find yourself waiting until the last minute to study for exams? The Study Cycle, adapted from Frank Christ’s PLRS system by the LSU Center for Academic Success and discussed by Saundra McGuire in her book Teach Yourself How to Learn, is a guide to help you build effective studying into your everyday life. On the surface, each step may seem obvious, but all too often students take shortcuts and miss important opportunities to benefit from the interplay of each step of the cycle. In the Study Cycle, each step builds on the previous one and distributes your learning throughout the semester, which is much more effective than waiting until the day before the test to study.

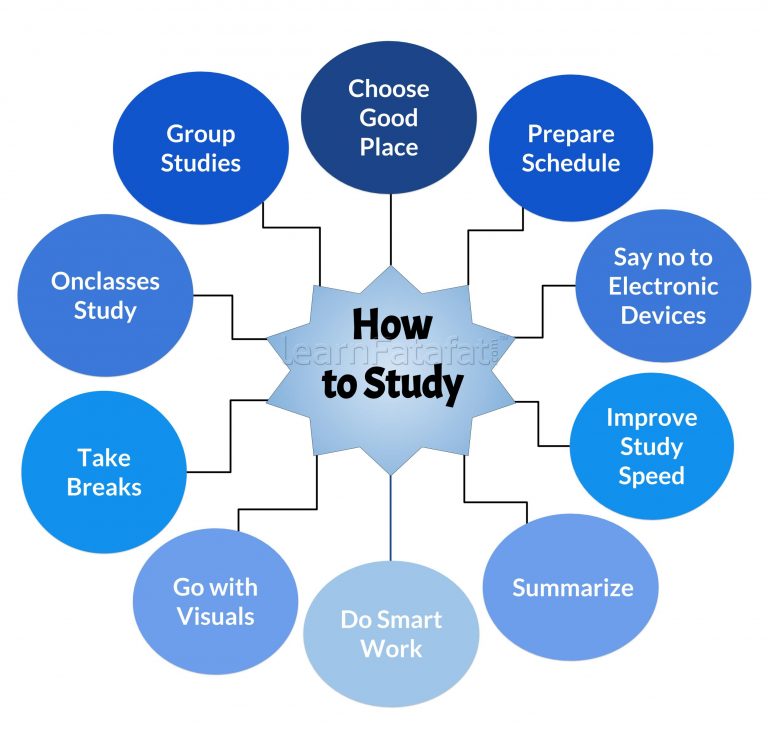

Step 1: Preview

Take a look at what you’ll be covering during lecture before you go to class. This will help you gain a sense of the big picture and anticipate how concepts fit together. You will get more out of attending the lecture (step 2) if you already have some context for what you’re about to learn, and you can come into class with questions that you expect will be answered.

You will get more out of attending the lecture (step 2) if you already have some context for what you’re about to learn, and you can come into class with questions that you expect will be answered.

Make sure to do the pre-class reading. Even if your teacher does not specifically assign reading, you can use the course schedule on the syllabus to find out what will be covered and preview the content. If you’re pressed for time, it is okay to skim—focus on headings, introductions, and summary. If your professor provides you with learning objectives or PowerPoint slides ahead of time, make sure to preview those and maybe even print them out to take notes on. The important thing to keep in mind here is that neither skimming, reading, nor attending class is incredibly effective on its own, but the combination (and sometimes repetition) of the two results in good learning. If you’ve heard a friend say “I don’t read for class because the professor covers everything in class,” they’re missing a huge opportunity to learn more from the lecture—meaning they’ll need to study more later in order to learn the material.

Step 2: Attend class

Of course, going to class is an important step in the study cycle, but just being physically present isn’t enough. Being attentive and engaged will help you get the most out of the experience. Class time is important, because this is when you get an understanding of the professor’s expectations and areas of focus (e.g., what’s going to be on the test), which will help you figure out what to focus on during your study sessions later (steps 3 and 4). It’s also a great opportunity to gain insight and intuition from your instructor and from other students in your class through asking questions and taking part in discussions.

During class, take notes in a way that will be useful to you. Taking notes by hand can help you remember the information—especially if you try to paraphrase in your own words. Try to stay off your phone/computer during class, unless you need it for an assignment. Keep track of your questions, and if you don’t get to ask them during class, make a plan to go to office hours or tutoring.

Step 3: Review

Take some time after class to go back over your notes. You don’t have to spend a long time doing this, but the sooner you do it the better. By reviewing soon after class, while the material is still fresh, you can fill in gaps and figure out what you might need help with.

When you’re reading back through your notes, make sure you’re actively engaging with the material. Passively letting your eyes scan over the material won’t actually help much. Instead, explain the material to yourself, summarize the key points, ask questions, and think about the big picture. Start to plan out how you might want to study the material you learned. If you’ve followed steps 1 and 2, this will be the third time you’re engaging with this content. Repeated exposure to the material helps you remember and understand it more effectively.

Step 4: Study

Schedule several focused study sessions per week for each of your classes. These sessions don’t have to be long; in fact, brief but intense study sessions tend to be more effective than trying to study for many hours at a time. Figure out how long you can stay focused and efficient—it may be just 20 to 30 minutes, but it will probably vary depending on the material—and then plan study sessions of this length throughout your week. By spreading your studying over time, you’re studying much more effectively (this is called “distributed practice”) and won’t have to try to do less-effective marathon study sessions before the exam (also known as “massed practice”). Distributed practice helps you learn the material at a deeper level because you have more time to process it, see connections, and ask questions.

Figure out how long you can stay focused and efficient—it may be just 20 to 30 minutes, but it will probably vary depending on the material—and then plan study sessions of this length throughout your week. By spreading your studying over time, you’re studying much more effectively (this is called “distributed practice”) and won’t have to try to do less-effective marathon study sessions before the exam (also known as “massed practice”). Distributed practice helps you learn the material at a deeper level because you have more time to process it, see connections, and ask questions.

When you are planning your study sessions, it’s important to set specific and realistic goals. Having a plan for what you’re doing during the study session will help you use your time more efficiently. For more information about how to structure your study sessions check out this handout about intense study sessions. While studying, make sure to use active learning techniques. For example, you could work problems, create a concept map, or explain concepts out loud. In between your short study sessions take a break that will refresh you. After a productive study session, reward yourself.

In between your short study sessions take a break that will refresh you. After a productive study session, reward yourself.

Step 5: Check

The last step is the one that a lot of people forget about. It’s important to check in with yourself to make sure what you’re doing is working and being open to changing your techniques if it’s not. After all, you wouldn’t want to spend a lot of time doing something that is not helping you learn. To make sure that your studying is effective, take a step back on a regular basis and ask yourself some metacognitive questions. Practice self-testing on a regular basis. Discuss what you’re learning with classmates. Check in with the learning objectives and make sure you are meeting them.

Want to learn more about the study cycle and create a plan to implement these practices? Make an appointment with an academic coach at the Learning Center to work on this or any of your other academic goals.

Works consulted

Christ, F. L (1997). “Seven steps to better management of your study time.” Clearwater, FL: H&H.

L (1997). “Seven steps to better management of your study time.” Clearwater, FL: H&H.

Louisiana State University, Center for Student Success (2015). “The Study Cycle: The Path to Improving Study Techniques.” Accessed June 9, 2020. https://www.lsu.edu/cas/earnbettergrades/vlc/CAS_VLC_StudyCycleFSS.pdf

McGuire, S.Y. (2018). Teach Yourself How to Learn: Strategies You Can Use to Ace Any Course at Any Level. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, LLC.

McGuire, S.Y. & McGuire, S. (2016). Teach Students How to Learn: Strategies You Can Incorporate in Any Course to Improve Student Metacognition, Study Skills, and Motivation. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, LLC.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Learning Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

If you enjoy using our handouts, we appreciate contributions of acknowledgement.

Make a Gift

How to study less, but better: tips on how to study easier

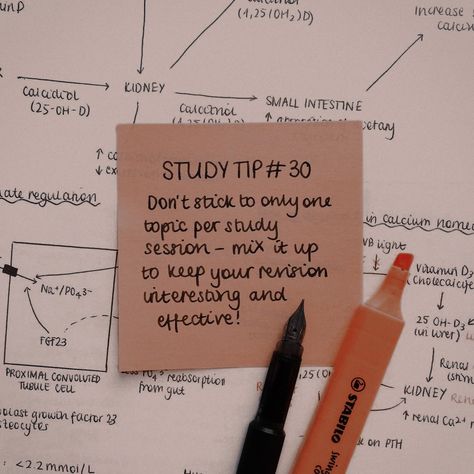

Alternate subjects and topics to make learning easier

There is nothing worse than monotony. The brain “boils” when you spend hours solving the same type of math problems or cramming dates in history. Do not do it this way.

It is more efficient to work in blocks. For example, half an hour of graphics in algebra, half an hour of equations, and the next hour - a table in social studies. It is this approach that Zina Kuznetsova, a student of the Foxford External and Home School, adheres to. She believes that if you do one subject all day, you will quickly overwork, you need to switch in order to study better.

Focus on one task

Source: freepik.com / @freepic.diller

As tempting as it may be to do your homework while watching the lesson recording, you shouldn't do it.

Such multitasking reduces productivity. Although switching attention takes a fraction of a second, the brain gets tired of it quickly.

When you take on something, give it maximum attention. Turn off notifications in instant messengers and social networks, close unnecessary browser tabs and put your phone away to make it faster and easier to study.

Train your concentration with the Pomodoro method. Foxford extern Alina Akhaeva tested its effectiveness on herself. She set intervals in which study alternates with rest: 25 minutes of active work and 15 minutes of rest. On average, it turns out six "tomatoes" per day.

<

Upgrade your self-education skills

Which is faster - walking or cycling? The answer is obvious. It is the same with studying - the process will go much better if you learn how to study. Here are our tips:

- Practice one or more note-taking techniques. Abstracts are not at all long and tedious, but easy and useful. A well-written note will help you comprehend and remember information, and it will become easier to learn.

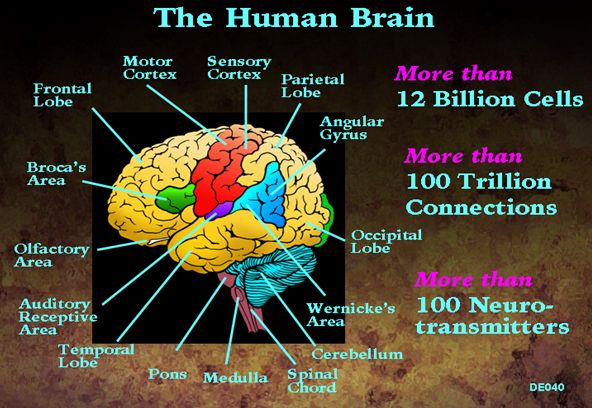

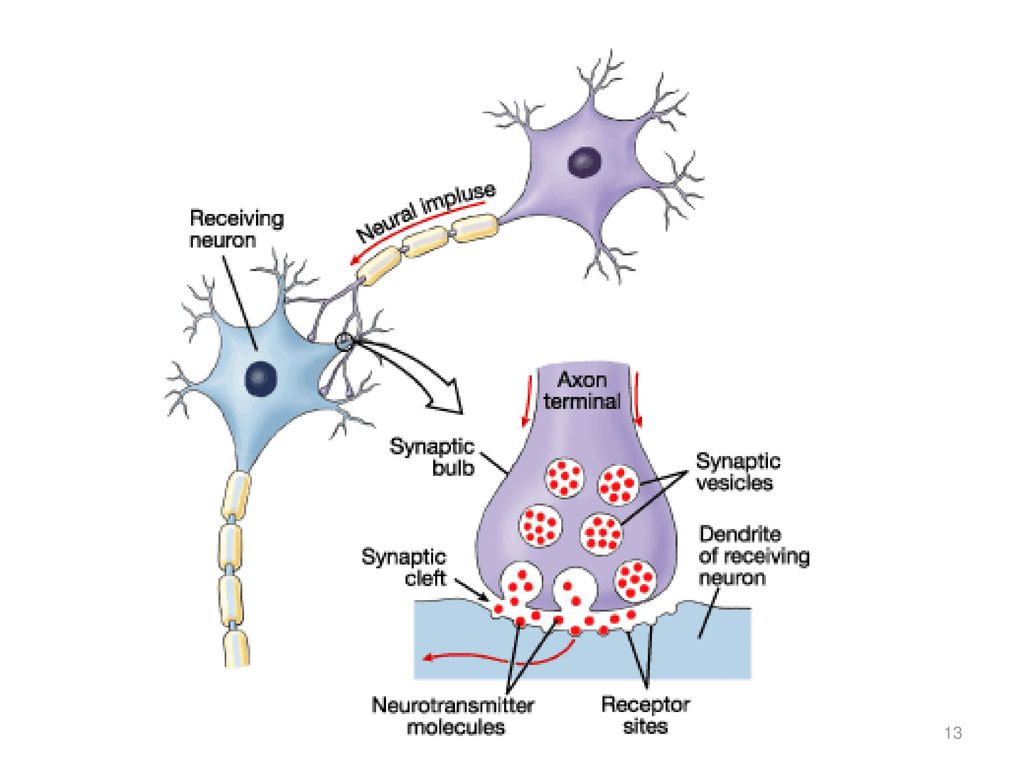

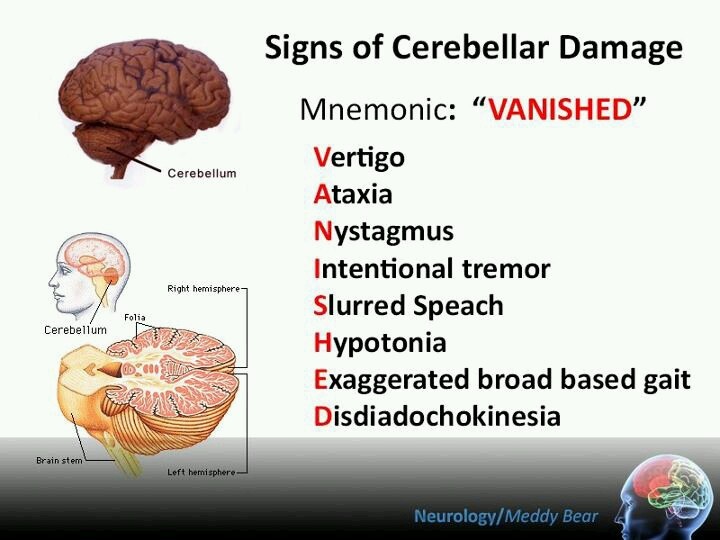

- Develop your memory. Mnemonics help. Foxford Home School even has a separate course with tricks to facilitate memory for good study.

- Practice speed reading. Slow reading leads to distractions that make you tired. And most importantly, a slow reader does not keep up with the growing amount of information.

The list is not exhaustive. Work on yourself, and then study will be a joy.

Use spaced repetition to improve your learning

Learning is not enough, you have to keep the material in your memory.

In 1932, the British psychologist Alex Mays wrote the book The Psychology of Learning. The professor suggested that it is much more productive not to cram, but to repeat the material at regular intervals. In 1939, this method was tested on 3,600 students and proved to be effective.

There is a spaced repetition formula: Y = 2X + 1.

Y is the day when information will start to be forgotten; X is the day of the last contact with the information. It is easy to calculate that the lesson that took place on Monday should be repeated by Thursday. Psychologists recommend the following scheme:

It is easy to calculate that the lesson that took place on Monday should be repeated by Thursday. Psychologists recommend the following scheme:

- the first repetition - 15-20 minutes after the lesson;

- second repetition - two hours later;

- third repetition - the next day or a day later;

- fourth repetition - three days later;

- 5th repetition - in a week.

Spaced repetition really helps you learn better and works great with the flashcard system.

<

Watch how you feel

When the body is out of order, learning does not bear fruit. It is necessary to maintain a balance between study and rest. Our tips to make learning easier:

- Try to get up and go to bed at the same time. Sleep 7-8 hours a day.

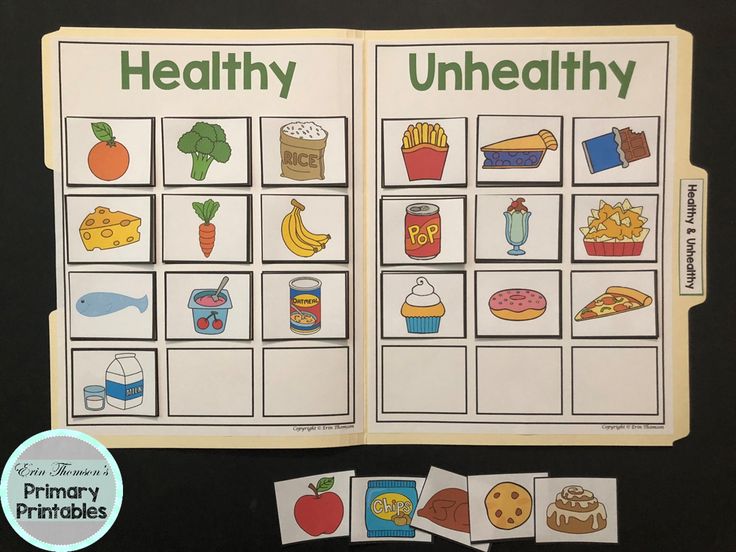

- Eat right. In your diet all year round should be vegetables and fruits.

- Exercise. Some proteins necessary for the brain are intensively produced only during physical activity.

It is not necessary to go to the gym. Simple exercise and a walk already significantly improve cognitive functions.

It is not necessary to go to the gym. Simple exercise and a walk already significantly improve cognitive functions. - Take breaks every 25-30 minutes of intense mental activity. Just do not open social networks or watch TV shows during your vacation - a new flow of information will not allow you to relax. It is better to drink tea or just lie down with your eyes closed.

In order to study better, it is necessary to find time for rest, says Yana Negina, a student of the Foxford Home School. Sometimes it is necessary to focus on studying, and sometimes it is more important not to sit in the lesson, but to go for a walk or draw. Online school gives you the opportunity to listen to yourself, so why not do it?

23 life hacks to study more productively

June 21, 2016 Education Adviсe

You can be a very intelligent and teachable person, but that's not enough. If the environment is distracting and overwhelming, you will most likely learn much less than you planned, and spend a lot of time. How to study productively? We have selected the best tips from Quora users for you.

How to study productively? We have selected the best tips from Quora users for you.

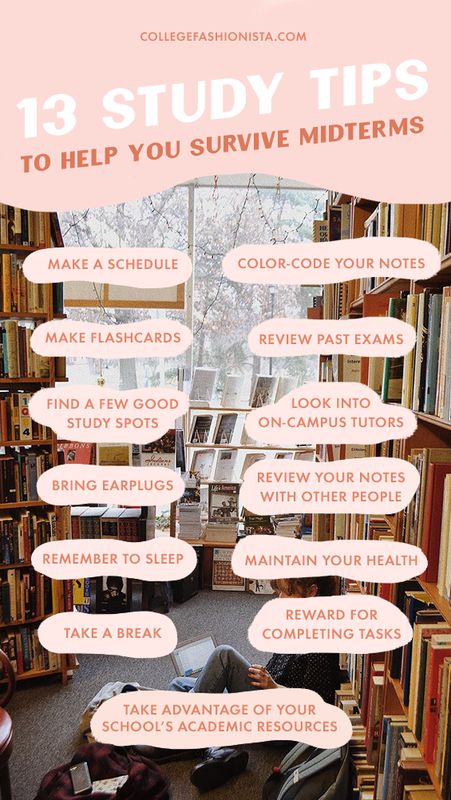

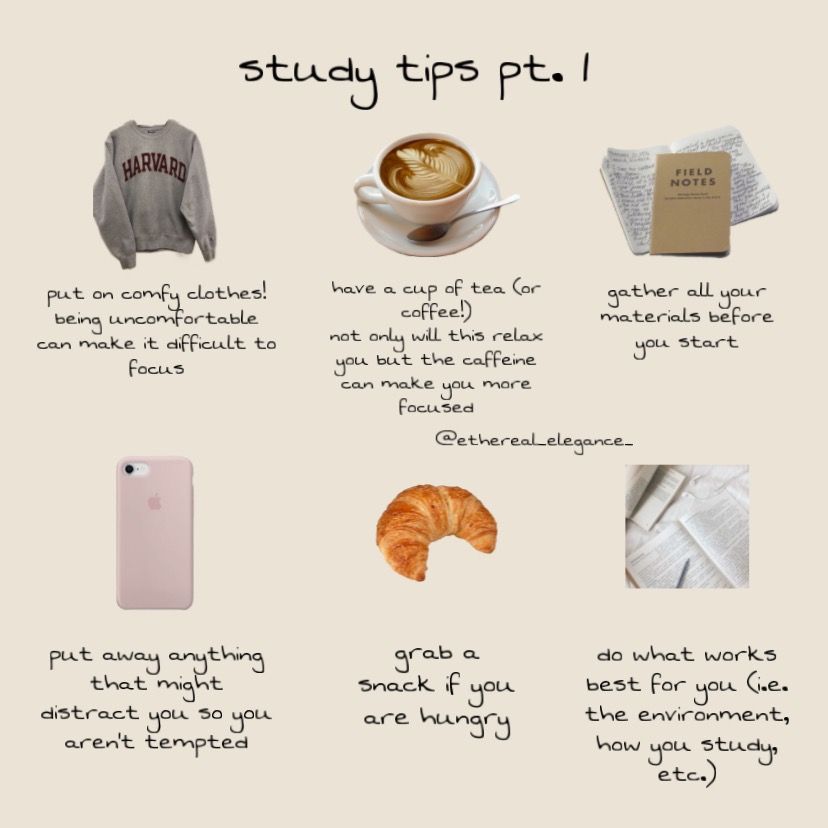

1. Get ready to study

- Choose the right place. You need to practice in a clean, bright, quiet, ventilated room. Best of all - at a desk with a bright lamp. If you don’t have such a place at home, go to the library and sit at a table at the far end of the room where other visitors will not pass you every five minutes.

- Keep all the materials you need close at hand. Textbooks, notebooks, notebook, reference materials (bookmarks in the browser or stickers on the table). Be sure to make a plan for the day: list all the tasks that you must complete.

- Always carry essential items with you. A bottle of water, a thermos of coffee or tea, a sweater if it's cool, and a snack (banana, fruit or nut mix).

- Shut off the noise. If you're exercising out of the house, bring headphones so you don't have to worry about background noise.

Choose music that promotes productivity (a win-win option is classics like Mozart, Haydn, Vivaldi, Beethoven). The main thing is that the music does not prevent you from concentrating on the material. If you find yourself focusing more on the melody than on the subject being studied, turn off the player, put on earplugs, and study in silence.

Choose music that promotes productivity (a win-win option is classics like Mozart, Haydn, Vivaldi, Beethoven). The main thing is that the music does not prevent you from concentrating on the material. If you find yourself focusing more on the melody than on the subject being studied, turn off the player, put on earplugs, and study in silence. - Get some sleep. Before training, it is better to gain strength, and not watch TV shows all night long. On the night before the exam, it is also better not to sit over textbooks, but to get enough sleep: sleep helps to consolidate information in long-term memory.

2. Eat right

- The most important thing is a balanced breakfast. To get the energy you need, approach your morning menu wisely. For example, combine proteins, fruits, and healthy fats (nuts are an essential source). It can be oatmeal or yogurt with muesli, fresh fruit, walnuts and almonds.

- Eat eggs.

Eggs are a combination of B vitamins (they help burn glucose), antioxidants (protect neurons from damage), and omega-3 fatty acids (they keep neurons functioning at optimal speed).

Eggs are a combination of B vitamins (they help burn glucose), antioxidants (protect neurons from damage), and omega-3 fatty acids (they keep neurons functioning at optimal speed). - At lunch, eat foods that support brain function. Optional sardines, spinach, lentils.

- The best snack is walnuts. They improve the ability to memorize and contribute to more productive learning. To achieve maximum effect, you need very little, no more than a handful.

- Drink vegetable and berry smoothies. Did you know that the nitrates contained in beets increase blood flow to the brain and thereby increase its efficiency? Here is a simple recipe for a tasty and healthy drink: in a blender, blend ½ cup orange juice, 1 cup fresh or frozen berries (strawberries, raspberries, blueberries), ½ cup chopped fresh or boiled beetroot pieces, 1 tablespoon muesli, 2-3 dates, ¼ cups of fat-free yogurt and 3 ice cubes.

- If you feel like falling asleep over your textbooks, drink coffee or eat some dark chocolate.

A light cappuccino or latte helps in this case much better than espresso: they not only have a powerful dose of caffeine, but also carbohydrates that fill you with energy. Energy is not the best option. But if you still drank an energy drink, then do not interfere with it with coffee.

A light cappuccino or latte helps in this case much better than espresso: they not only have a powerful dose of caffeine, but also carbohydrates that fill you with energy. Energy is not the best option. But if you still drank an energy drink, then do not interfere with it with coffee.

3. Practice time management

- When learning new information, set a timer for 30-60 minutes. When one segment passes, get up from the table and do something that is not related to study: walk around for five minutes, look out the window, warm up, go for tea or coffee. Give your head a chance to rest.

- If you are preparing for an exam, make a list of questions for yourself and use the Pomodoro technique. Try to answer each question using the shortest amount of time possible (no more than 25 minutes). You can make a list of questions yourself or choose from a textbook or manual: usually each chapter or topic in educational publications ends with a block of questions.

- Answer the questions out loud. Write a short thesis outline of the answer, and then speak aloud. This technique will help you analyze, recall and fix information in memory much better than if you just read it to yourself.

4. Get rid of everything that distracts you

- Only use the phone for business. During breaks, you can see who called and call back. You can use the timer on your phone. But no chats and funny pictures.

- Put your phone in flight mode. When the issue is complex and you need to concentrate without being distracted by anything else, this is the best solution.

- Warn family, friends, roommates and loved ones that you will be unavailable for several hours. Most likely, they will meet you halfway and will not distract you with their requests, questions and comments.

- Check email and social media no more than 2-3 times a day.