Trauma of infidelity

Recovering from the trauma of infidelity

Most people agree that a sexual affair counts as infidelity, but what about sending a flirty text? What if your partner takes out several loans and acquires a large debt without your knowledge? Does engaging in virtual sex with someone other than your partner, connecting with an ex on social media or maintaining an online dating profile even though you are already in a relationship count as betrayal? The answer depends on how the people in the relationship define infidelity.

A recent study commissioned by Deseret News found conflicting answers when 1,000 people were polled about what constitutes “cheating.” The majority of respondents (71%-76%) said that physical sexual contact with someone outside of the relationship would always meet the threshold for cheating. However, a slimmer majority thought that maintaining an online dating profile (63%) or sending flirtatious messages to someone else (51%) should always be considered cheating.

The lines on whether following an ex on social media constituted a betrayal were even more ambiguous: 16% said it was always cheating, 45% thought it was sometimes cheating, and 39% answered that it never was.

As this poll illustrates, how one defines infidelity is subjective. Thus, Talal Alsaleem, a leading expert in the field of infidelity counseling and author of Infidelity: The Best Worst Thing That Could Happen to Your Marriage: The Complete Guide on How to Heal From Affairs, stresses the importance of clearly defining infidelity in session. “A lot of therapists make the mistake of not putting enough attention into defining infidelity,” Alsaleem says. “From the first session, if we don’t agree on what to call it, we cannot go any further” because correctly identifying the problem guides which counseling interventions will be used.

If counselors set the stage poorly from the beginning, they risk alienating one or both parties, he adds. For instance, referring to infidelity as “inappropriate behavior” risks minimizing the betrayal. On the other hand, clients and counselors could exaggerate an issue if they refer to something being infidelity when it really wasn’t.

On the other hand, clients and counselors could exaggerate an issue if they refer to something being infidelity when it really wasn’t.

Alsaleem, a licensed marriage and family therapist in private practice at Happily Ever After Counseling & Coaching in Roseville, California, points out that when defining infidelity, research often relies on heteronormative values, which excludes any relationship that does not fit the “traditional” model (read: a heterosexual, married couple). To account for the various types of relationships that exist and people’s microcultures and macrocultures, Alsaleem developed a flexible definition of infidelity that can work for all of his clients, including those who are LGBTQ+ or polyamorous.

“All relationships should have a contract — whether verbal or written — that stipulates the number of the partners in the relationship … the emotional and sexual needs that are expected to be fulfilled in this relationship, and to what extent those needs are exclusive to the partners in the relationship,” Alsaleem explains. “So, infidelity is a breach of contract of exclusivity that you have with the partner(s) … and it’s outsourcing those needs to others outside the relationship without the consent of the partner(s).”

“So, infidelity is a breach of contract of exclusivity that you have with the partner(s) … and it’s outsourcing those needs to others outside the relationship without the consent of the partner(s).”

Although having a relationship contract is helpful, it is much less so if the partners maintain implicit expectations of each other that aren’t covered in the contract or if they allow the contract to become static, says Alsaleem, founder of the Infidelity Counseling Center. “It’s very crucial for people not only to have a clear contract in the beginning but also to continue to have those discussions [about their relationship expectations] on a regular basis,” he says.

Alsaleem believes his definition of infidelity not only works for clients of various backgrounds but also provides counselors with a buffer from their own biases about what infidelity is. When it comes to infidelity counseling, “therapists tend to confuse therapeutic neutrality with thinking that they don’t have a role to play,” he says. He asserts that his definition allows therapists to remain neutral without minimizing accountability.

He asserts that his definition allows therapists to remain neutral without minimizing accountability.

Cyber-infidelity

Technology has provided new frontiers in infidelity because it offers higher accessibility, greater anonymity and opportunities for cyber-infidelity, says Alsaleem, who presented on this topic at the 2020 conference of the International Association of Marriage and Family Counselors (IAMFC), a division of the American Counseling Association. In fact, technological advancements such as virtual reality pornography and teledildonics — technology that allows people to experience physical tactile sensations virtually — are adding new layers of complexity to infidelity and relationships.

People can use technology to escape real-world problems and reinvent themselves, Alsaleem notes. One of his clients suffered from erectile dysfunction. Because of the shame and stigma associated with his condition, he turned to virtual sex as a way to accommodate for the deficit rather than dealing with the issue with his wife.

“Because [technology] is a new frontier, it’s an unchartered territory. Not too many people can agree on what’s appropriate or what’s inappropriate online infidelity behavior because we don’t have a reference point for it,” Alsaleem says. “That ambiguity makes it easier for people to cross those lines because in their minds, they’re not doing anything bad.”

Alsaleem worked with another couple who were in a happy relationship, but their sexual intimacy had decreased because of common life stressors such as work and parenting. Rather than talk to his wife about it, the husband started watching pornography, which evolved into virtual sex. When the wife discovered this, she felt betrayed, but the husband didn’t think his actions constituted an affair because it wasn’t happening in the real world. He considered virtual sex to be an acceptable alternative to “real cheating.”

Situations such as this one further emphasize the need to clearly define infidelity and establish a relationship contract, says Alsaleem, who points out that the good thing about his definition of infidelity is that it applies to both real world and virtual world affairs. Using his definition, counselors could work with a couple to help a partner realize that virtual sex is a form of infidelity by asking, “Was there an agreement between you and your partner that all your sexual needs would be fulfilled by them only?” If the partner acknowledges that this agreement was in place, then the counselor could ask, “Is what you did derivative of sexual needs? If so, did you outsource this need to someone else?” This form of questioning would help the partner realize that he or she did in fact breach the contract of exclusivity.

Using his definition, counselors could work with a couple to help a partner realize that virtual sex is a form of infidelity by asking, “Was there an agreement between you and your partner that all your sexual needs would be fulfilled by them only?” If the partner acknowledges that this agreement was in place, then the counselor could ask, “Is what you did derivative of sexual needs? If so, did you outsource this need to someone else?” This form of questioning would help the partner realize that he or she did in fact breach the contract of exclusivity.

Transcending relationship dissatisfaction

Relationship dissatisfaction is a common cause of infidelity, but it is far from the only cause. Alsaleem recommends that counselors consider three categories when working with infidelity.

The first is dyadic factors, which are any relationship issues that lead to the couple not having their sexual or emotional needs met by each other.

The second category is individual factors — each partner’s personal history and overall mental health. Counselors should ask about clients’ family history and previous mental health issues, not just their relationship history, Alsaleem advises. He points out that some mental health issues, such as bipolar disorder and narcissistic, antisocial and borderline personality disorders, may increase the likelihood of infidelity.

Counselors should ask about clients’ family history and previous mental health issues, not just their relationship history, Alsaleem advises. He points out that some mental health issues, such as bipolar disorder and narcissistic, antisocial and borderline personality disorders, may increase the likelihood of infidelity.

People who experienced sexual trauma at an early age are also more likely to engage in infidelity as adults because the trauma may have affected their attachment, sexual identity and the type of relationships they have in adulthood, Alsaleem adds.

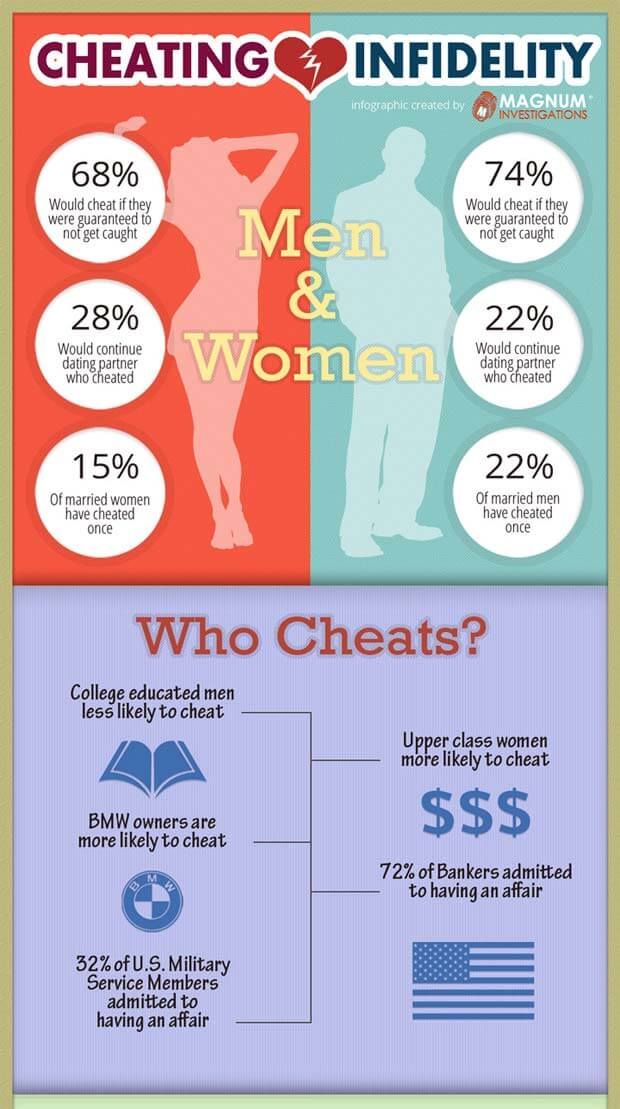

The third category is sociocultural factors, including a person’s job, culture, family, friends, lifestyle, environmental stressors, etc. Survey data taken from Ashley Madison, a website that helps married people have affairs, reveal that certain careers and occupations are more correlated with infidelity. These careers typically involve frequent travel; expose people to trauma; feature long, stressful hours; or offer unhealthy work environments (among the examples provided were military personnel, first responders, nurses, police officers and people in sales). This finding illustrates how one’s sociocultural factors can facilitate infidelity behavior, Alsaleem notes.

This finding illustrates how one’s sociocultural factors can facilitate infidelity behavior, Alsaleem notes.

Treating the trauma

Sometimes clients who experience a partner’s infidelity meet the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), says Gabrielle Usatynski, a licensed professional counselor (LPC) and founder of Power Couples Counseling in Boulder and Louisville, Colorado. In fact, because the emotional response to infidelity (e.g., ruminating thoughts, sleep problems, erratic behaviors and moods, health problems, depression) can mirror responses to other traumatic events, some therapists have started using the term post-infidelity stress disorder to describe this parallel.

“If you pull up the DSM-5 and look up the PTSD criteria and change the word traumatic event to infidelity, it’s almost going to be picture perfect in terms of the symptom criteria,” Alsaleem points out. “There will be triggers, flashbacks, hypervigilance, avoidance behavior, and manifestations related to the knowledge about the affair and everything related to the affair. ”

”

The fallout from infidelity can also spill over into other roles that people occupy, such as being a parent or a professional. This can lead to guilt and shame if they are not performing well in another area because they are preoccupied with the trauma of the betrayal, he says.

Despite having worked for a while with couples in crisis, Alsaleem found that none of the counseling tools he had acquired over the years adequately dealt with infidelity. If counselors use a generic trauma-informed approach with infidelity, they may have a strategy to handle the sensitivity of the issue, but they won’t have a clear understanding of the obstacles and the steps needed to overcome them, he says.

Alsaleem started jotting down observations of his clients dealing with infidelity and discovered several struggles that these clients shared regardless of the type of relationships they had, the length of their relationships, or their cultural or religious backgrounds. These shared struggles included defining infidelity, handling the emotional impact of infidelity, and navigating the significance of the affair narrative. Alsaleem’s observations led him to develop systematic affair recovery therapy (SART), which provides counselors with a treatment method for helping couples process and heal from the trauma of sexual and emotional infidelity.

Alsaleem’s observations led him to develop systematic affair recovery therapy (SART), which provides counselors with a treatment method for helping couples process and heal from the trauma of sexual and emotional infidelity.

SART describes seven milestones clients go through as they heal from infidelity:

- Setting the stage for healing

- Getting the story

- Acknowledging the impact

- Choosing a path

- Creating a plan of action

- Implementation and healing pains

- Sustainability

“Your role [as a counselor] is to help them process what happened, to make sense of it, so this trauma does not define the rest of their lives, whether as a dyad who are rebuilding the relationship or as individuals who have decided to separate and move on to other relationships,” Alsaleem says.

He warns that the process isn’t easy because clients often come in with knee-jerk reactions about what they want to do. Counselors must help clients resist making impulsive decisions and instead encourage them to make up their minds after completing the proper steps and understanding why they are making their decision, Alsaleem says.

With affair recovery, Jennifer Meyer, an LPC in private practice in Fort Collins, Colorado, finds it helpful to have couples write down their feelings and emotions, which can be intense. From the beginning, she asks couples to share a journal and write their feelings back and forth to each other.

After the couple has had time to identify and process the cause of the infidelity, Meyer asks the partner who has been unfaithful to write an apology letter and to read it to the injured partner in session. In this letter, the offending party conveys that they understand the pain they have caused and feel remorse for their actions. Even if the couple decides not to stay together, the letter helps repair the damage caused by the infidelity, and the partners can move forward (and, eventually, into new relationships) without carrying the pain and trauma with them, Meyer says.

Navigating the affair narrative

Some therapists avoid having clients share details about the infidelity because they fear it will create more harm or retraumatize clients, Alsaleem says. He argues that narrating the affair is a painful yet crucial part of recovery that can help facilitate healing if done with the right level of disclosure.

He argues that narrating the affair is a painful yet crucial part of recovery that can help facilitate healing if done with the right level of disclosure.

Alsaleem dedicates an entire day in his SART training program to teaching counselors how to help clients share their affair stories without retraumatizing both parties (by sharing too much or too little information) and without minimizing or exaggerating what happened. With infidelity counseling, “every mistake counts,” he says. “When people are coming in after the discovery of infidelity, whether it’s recent or from the past, they are very fragile, so that’s when you need to be strategic and adaptive and plan each intervention and how to respond to the outcome of the intervention.”

Meyer, a member of both ACA and IAMFC, often finds that clients want to ask the offending partner multiple detailed questions about the intricacies of the affair. Meyer is aware that the answers to these questions have the potential to create even more hurt and trauma for her clients, so she is honest with couples about this possibility and guides them through the process.

Alsaleem provides a brief example of how counselors can determine the appropriate level of disclosure when clients share their affair stories (but he advises clinicians to seek further training before trying this approach). He first asks the offending partner to be proactively transparent when sharing the affair story. They shouldn’t hide anything, he says, and they should go out of their way to show the injured partner(s) the unpleasant truths that led to the affair. This is done not to traumatize, he emphasizes, but to show the offending partner’s capacity to be open and honest.

Alsaleem also tells injured clients that they can ask anything they want about the affair. But before they ask, he helps them determine whether the question will help them understand what type of affair it was or why the affair happened. If so, then it is a fair question, he says.

For example, a client dealing with a partner’s sexual infidelity may want to ask, “What specific sexual activities did you engage in?” If the partner who was unfaithful is dealing with a sexual addiction (an individual issue), then the specific sexual activity is not important to understanding the motivation or what went wrong in the relationship, Alsaleem says. However, if the infidelity occurred because of a compatibility issue (a dyadic issue), then that would be a fair question because the betrayed would discover in what ways they are no longer fulfilling their partner’s sexual needs, he explains.

However, if the infidelity occurred because of a compatibility issue (a dyadic issue), then that would be a fair question because the betrayed would discover in what ways they are no longer fulfilling their partner’s sexual needs, he explains.

“The need behind the question [can be] healthy and appropriate, but sometimes [clients are] not asking the right question because they don’t know how to address that need,” Alsaleem adds. He advises counselors to ask clients what they are trying to learn about the story with their questions and help them figure out if these questions are the best way to obtain that information while avoiding further traumatization.

Affairs can evoke intense emotions in session, especially when discussing the affair story. To ensure that emotions don’t escalate to an unproductive level, Meyer uses a preframe such as “You seem calm at the moment, but this is difficult, and I want to ensure you can both talk without being interrupted. If things get out of hand, I’m going to ask for a timeout. You can both ask for a timeout as well.”

You can both ask for a timeout as well.”

Meyer also uses her own body language — such as scooting up in her chair or standing up — if clients start yelling uncontrollably, or she physically separates them for a few minutes by having them take turns going to the restroom or getting a glass of water. These subtle changes help clients calm down and not get stuck in fighting, she explains.

Creating an imbalance to facilitate healing

Usatynski, an ACA member who specializes in couples therapy, approaches infidelity counseling differently from couples therapy where betrayal is not the presenting issue. In ordinary couples therapy, she strives to keep therapy as balanced as possible, focusing equally on the complaints of both partners and the unresolved issues that each brings to the relationship. But when infidelity is involved, she intentionally creates an imbalance of power and initially allows the injured party to have all of the power. The offending party, on the other hand, does not get to bring any of their complaints about their partner or their relationship to the table until they have successfully addressed the injured partner’s distress. This treatment works only if the offending party expresses true regret for the harm they have caused their partner and expresses a genuine desire to rebuild the relationship, Usatynski adds.

This treatment works only if the offending party expresses true regret for the harm they have caused their partner and expresses a genuine desire to rebuild the relationship, Usatynski adds.

Usatynski’s approach comes from a psychobiological approach to couple therapy (PACT), which is a fusion of attachment theory, developmental neuroscience and arousal regulation developed by Stan Tatkin. When betrayal is the presenting issue, this method requires that clients move through three phases as they process and attempt to repair their relationship.

The first phase addresses the trauma the injured client has experienced by allowing them to express all of their emotions about the betrayal. “It’s when people feel like they have to hold back [emotions] or they can’t get angry or there’s nobody there to listen to them that actually creates trauma or at least makes it worse,” Usatynski says.

The partner who was betrayed can also ask any question they want about the affair during this phase, and the offending partner has to answer honestly. Many therapists who work with betrayal are concerned about the injured partner being traumatized by finding out the truth, Usatynski says. She admits this is a valid concern, so therapists should support the injured partner throughout the process. However, she advises that therapists not shy away from the truth coming out because, as she explains, the only way to repair the relationship or build something new is with total transparency.

Many therapists who work with betrayal are concerned about the injured partner being traumatized by finding out the truth, Usatynski says. She admits this is a valid concern, so therapists should support the injured partner throughout the process. However, she advises that therapists not shy away from the truth coming out because, as she explains, the only way to repair the relationship or build something new is with total transparency.

If clients are hesitant to ask about the affair, therapists need to explore this hesitation with them. The injured partner may say that they don’t want to know what happened out of an inability to deal with feelings of loss and the practical implications of the relationship ending, Usatynski adds.

During this initial phase, the offending partner has no power to negotiate. They must simply sit and endure the rage and inquiry of the person whom they betrayed, Usatynski explains.

The second phase of PACT involves the offending partner providing the betrayed with whatever support is needed to correct the injury to the attachment bond between them, Usatynski says. This phase could involve declarations of commitment, appreciation or praise, as well as loving actions on the part of the offending partner. However, only the injured partner can decide what behaviors are reparative, she explains. The goal of this phase is resolution.

This phase could involve declarations of commitment, appreciation or praise, as well as loving actions on the part of the offending partner. However, only the injured partner can decide what behaviors are reparative, she explains. The goal of this phase is resolution.

During the third phase, the injured partner lets the offending partner out of the “doghouse” and, together, the couple decide the new rules and new relationship contract they will have going forward, Usatynski says.

According to PACT, the dysregulation of one’s nervous system (such as during states of hyperarousal or hypoarousal) may lead to discord between the couple, Usatynski says. Thus, counselors should not only track clients for signs of dysregulation but also teach couples how to track each other’s nervous systems.

When Usatynski notices a client showing signs of dysregulation (e.g., changes in skin color, posture or vocal tone), she will ask the other partner if they recognize the change. For example, she might say, “Did you see how your partner’s skin color just changed when he or she said that? What do you think is going on with him or her right now?”

The goal is interactive regulation — the couple learning the specific strategies that soothe, regulate and excite each other, Usatynski notes. “These tracking skills are particularly important in the aftermath of betrayal because … [they help the offending partner] develop a greater awareness of how their behavior affects their partner. These skills also boost sensitivity and empathy,” she explains.

“These tracking skills are particularly important in the aftermath of betrayal because … [they help the offending partner] develop a greater awareness of how their behavior affects their partner. These skills also boost sensitivity and empathy,” she explains.

A silver lining?

Alsaleem compares infidelity to a heart attack for the relationship. “It’s a critical wake-up call,” he explains. “It forces [clients] to really lay all the cards on the table and make an informed decision.” Do they commit to fixing all of the deficits and work toward having a better, stronger relationship, or do they end their relationship and find new, healthier relationships?

Alsaleem says several of his clients began therapy devastated by the trauma of infidelity, but by the end, they admitted they were almost glad it had happened because it ultimately led them to having the relationship they always wanted with their partner. For some people, infidelity is the catalyst that ultimately allows them to get unstuck, he explains.

When clients decide to repair their relationship, Meyer helps them develop a new, explicitly stated contract regarding the rules in their relationship moving forward. She asks them to write down their agreement about these new relationship rules (including how quickly they would inform their partner that they experienced a compromising situation and what constitutes infidelity going forward) and ways they could be vulnerable to future affairs.

“As counselors, we can’t assume every couple wants or needs strict monogamy,” Meyer adds. So, this new agreement can take many forms depending on the relationship. For example, partners in a committed relationship may agree that being involved with another person sexually is OK as long as they discuss it first with their partner or keep everything in the open.

Of course, clients in infidelity counseling may also decide to end their relationship. Even so, by showing up to counseling, clients have taken the first step toward ensuring that infidelity does not define the rest of their lives, Alsaleem notes.

“Infidelity is an awful event, but it doesn’t have to be devastating. It actually has a silver lining. Infidelity — as awful as it is to experience, as awful as it is to happen — can actually be a good thing to help people change their lives,” Alsaleem says. “If treated appropriately, it can actually enrich people’s lives and make them more resilient and make them better in the long run.”

****

Related reading: An online companion article to this feature, “Helping clients rebuild after separation or divorce,” provides strategies for helping clients to process their grief and start over.

****

Lindsey Phillips is a contributing writer to Counseling Today and a UX content strategist. Contact her at [email protected] or through her website at lindseynphillips.com.

****

Opinions expressed and statements made in articles appearing on CT Online should not be assumed to represent the opinions of the editors or policies of the American Counseling Association.

How Infidelity Causes Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Of all of the threats to a committed relationship I have treated in four decades of working with couples, the most difficult to heal is infidelity. When a trusted partner in a committed relationship betrays the sacred trust of the other, the relationship will undergo severe instability.

The partner who has been betrayed is emotionally tortured and humiliated when knowledge of the infidelity emerges. They are clearly in trauma and experience the same array of symptoms that professionals now describe as post-traumatic stress disorder. Similar to any others who have suffered threats to their physical or emotional well-being and security, they are disoriented and confused by what has happened.

Similar to the classical symptoms of PTSD, relationship partners of both genders may experience:

- Repeated intrusive thoughts.

- Unstable emotional regulation.

- Out-of-body experiences.

- Alternating between feeling numb and striking out in retaliation.

- Inability to stop scanning for any new data that might cause more distress.

- Feeling overwhelmingly powerless and broken.

- A need to regain self-worth by assigning blame.

- Confusion and disorientation.

“Ever since I found out about the affair, I can’t stop thinking about what happened. I have repeated nightmares. My faith in trust and love is demolished. The person I believed in most in the world betrayed me without seeming to care. If I’d known something was wrong, maybe I could have stopped it before it got going. I spin between being devastated and being enraged. I can’t seem to find any peace, knowing that there is probably more than I will ever be told. I feel like a goddamn fool, humiliated and broken. How could my partner do this to me?”

The trauma of betrayal can also trigger memories of buried or unresolved emotional and spiritual damage from the past. When those prior traumatic experiences are triggered and re-emerge, they significantly complicate the healing process.

For there to be any chance that the couple undergoing this situation can ever transcend the distress of broken trust, they must deal with two simultaneous challenges: The first is to understand and work through the combination of both current and re-emerging trauma responses of the betrayed partner. The second is for both partners to commit to specific roles in the healing of their mutual distress.

The 5 Most Common Re-Emerging Issues

1. History of Prior Trauma

When people experience a life-threatening event earlier in life, they create defenses that allow them to survive those traumas. Those defenses can be either barricades to future pain or unconscious seduction to recreate what is familiar.

If a relationship partner has been harmed by threats of loss or harm in the past, he or she will have a stronger and more persistent trauma response to a partner’s current betrayal. Dependent on how much they appear similar to what is happening in the present, they will mesh with the current pain and make recovery that much harder.

2. Emotional and Physical Resilience

Whether born into a person or learned throughout life, resilience is the conqueror of prolonged sorrow. Though grief must not be denied, those who are lucky enough to be more resilient can endure it without falling prey to extended emotional heartbreak.

Resilience after a betrayal is also buoyed up by the kind of social support a person has access to. When infidelity is discovered, it is easy for traumatized partners to lose sight of their own worth. Authentic, caring, and responsive others are able to remind them of who they were before the trauma and help them to regain emotional stability.

Sadly, the most common excuse many unfaithful partners give when they stray is that they were unable to get their needs met in the relationship. Those accusations increase the anguish of the betrayed partner.

3. The Strength of the Primary Relationship

When people have a strong bond, both partners openly talk about their needs and disappointments as they occur in their relationship. They know that outside temptations are always possible, but they are committed to making their relationship stronger if they arise.

They know that outside temptations are always possible, but they are committed to making their relationship stronger if they arise.

If a relationship is wavering and the people within it are no longer as bonded as they once were, one or both of the partners may be searching for meaning outside the relationship. If those yearnings are not shared and the relationship goes unresolved, they are more likely to transform into actions.

Some relationships feel more okay to one partner than they do to the other. If those feelings are not shared and an affair happens, the unknowing partner has had no opportunity to intervene. They feel they are doing everything right, that their love is intact, and that trust will never be broken. That partner is understandably more demolished when an affair emerges.

4. Double Betrayal: When the Infidelity Is With a Known Party

Besides the experiences of humiliation and anguish, an even more destructive heartbreak occurs when the third member of the triangle is a close and trusted friend or a family member.

When the betrayed partner discovers that two deeply trusted people could collectively collude behind his or her back is almost unfathomable. In these cases, there are often others who know what is going on causing even more potential loss of relationships when the affair emerges. Those who have remained silent may then pull away for fear of being seen as accomplices.

5. How Long the Infidelity Has Been Going On

An affair that is quickly confessed along with true remorse and the desire to do whatever is necessary to help the betrayed partner heal, has the best chance of success if it never happens again.

On the other hand, a partner who finds out that the betrayal has been going on for weeks or months, or even that it is still active, is fundamentally more damaged and finds it much harder to heal. For most women, it is not just a passing affair anymore. It is a fully developed relationship of secrecy, passion, and emotional connection, stealing love and commitment from the existing partnership. For most men, it is the sabotage of being cuckolded by another male who has taken his woman from under his eyes and sold him out as a “brother.”

For most men, it is the sabotage of being cuckolded by another male who has taken his woman from under his eyes and sold him out as a “brother.”

The person outside of the primary relationship, who has been willing to be a co-betrayer, often feels that he or she has claimed possession of the infidel. That individual may not be willing to be dismissed and can become a deterrent to a relationship’s potential healing.

Given the seriousness of these potential emerging issues and the ways they may combine, it is understandable how much influence they may have on whether or not the relationship can heal and over what period of time.

How do two people who do not want to lose their relationship navigate the process of broken trust to a possibility of reconciliation?

How does a betrayed partner ever learn to believe the other again?

How does the partner who chose to act this way get past his or her guilt and remorse?

What must happen for recovery and recommitment to even be possible?

Once both partners understand how likely it is that a betrayed partner will evidence the symptoms of PTSD, they realize that the healing process is the same for all traumas. The betraying partner must simultaneously play the dual roles of an ally to his or her partner’s healing and a seeker of absolution from the very person they have carelessly wounded. The other must survive the trauma and learn to love again.

The betraying partner must simultaneously play the dual roles of an ally to his or her partner’s healing and a seeker of absolution from the very person they have carelessly wounded. The other must survive the trauma and learn to love again.

The Role of the Betraying Partner as an Ally in Healing the Trauma

Most betraying partners truly want to heal their relationship but have difficulty not blaming their other partner in some why they chose to stray. Gender responses are often different. For instance, more men than women justify that decision by stating that their sexual needs weren’t being met, that their partners didn’t pay enough attention to them in general, or that they felt exploited in the relationship. More women than men traditionally cite their reasons for an affair as lacking an emotional connection with their primary partner, a lack of availability in general, or inadequate romantic support.

In order to expedite healing, the betraying partner has to recognize that they must put aside anything they felt that drove them to give in to an affair until they recognize and feel remorse for the act of betrayal, itself. They are legitimately on trial for invalidating the worth of their primary relationship, succumbing to a self-serving motivation, and the willingness to risk severely wounding the other partner.

They are legitimately on trial for invalidating the worth of their primary relationship, succumbing to a self-serving motivation, and the willingness to risk severely wounding the other partner.

As now allies in healing the relationship, they must be prepared to encourage and weather whatever frustration, anguish, or retaliation their betrayed partner needs to express. They must be willing to stay in the game for however reasonable time it may take, to put their own needs and underlying grievances aside, and to fully commit to the healing of their partner’s rage and grief. The more committed the betrayer is to the process, the sooner his or her partner will be able to heal.

The Role of the Traumatized Partner

Feeling devastated, humiliated, and broken are hard experiences to survive. Though the traumatized partner has every reason to be upset, he or she must work through those responses in a sincere and committed way, alongside the other partner’s commitment to do whatever is mutually needed for healing.

The partner experiencing PTSD will most likely have wildly swinging mood changes, emerging experiences of underlying, unresolved issues, and agonizing waves of grief. While simultaneously feeling the need to strike back, run away, or feel immobilized, they must learn to self-soothe, create resilience, seek outside support, and commit to a renewed faith in a better future.

If, additionally, they’ve been the object of previous trauma, they must also sort out what is happening in the present from what they may have endured in the past, so as not to blame their partner’s current betrayal for something they did not cause.

Building a Future Relationship

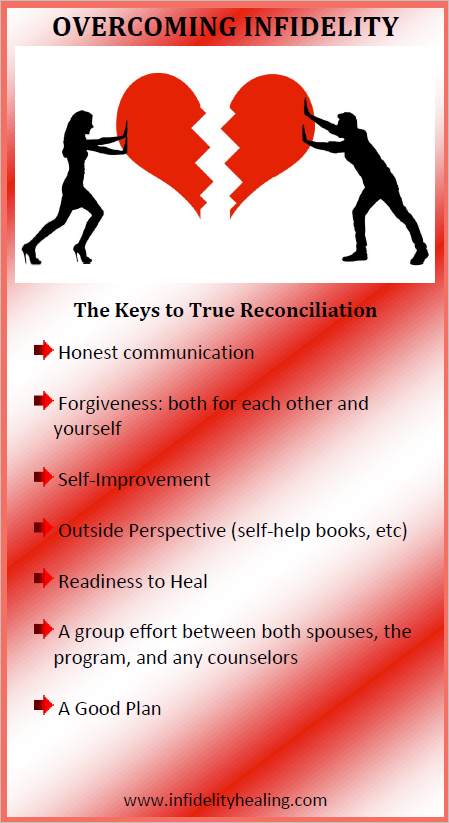

Both partners must realize that their past relationship is over and that their goal is to build a new one that will withstand challenges in the future. When the partner who is the ally in healing merges with the partner who is ready to move on, they can create a new kind of sacred trust that can be significantly stronger by virtue of what they’ve been through together.

This process is not for those who want a quick fix, nor for those who hold fast to the past. Superficializing a true betrayal can create unresolvable pain. Similarly, carrying mistrust, anger, and pain forever will eventually destroy any hope of true healing. The betraying partner must take seriously what he or she has done. The partner who has been betrayed must truly want to rebuild the relationship and ultimately learn to trust that person again.

Yes, I have seen partners do this kind of healing, and do it beautifully. They take the lessons from the past, learn to communicate courageously and honestly, and build something neither has known before. Their relationship Phoenix can emerge from the ashes of their mutual sorrow.

Facebook image: Cat Box/Shutterstock

6 mandatory steps that psychologists advise

Cheating is a hard blow. You can’t just get an apology from the one who deceived, and continue to live as if nothing had happened. Psychologists tell you what actions to take, regardless of whether you decide to give the relationship a second chance or are going to break up.

Psychologists tell you what actions to take, regardless of whether you decide to give the relationship a second chance or are going to break up.

Website editor

Tags:

Marriage and relationships

Love and relationships

adultery

Cheating on his wife

Health

Getty Images

Betrayal is a constant background of our lives. We read news about divorces of stars who caught the faithful with their mistresses. We watch series where infidelity is the cornerstone of the plot, from Big Little Lies to Unscrupulous. But just because deception is being normalized in the media doesn't mean it should be taken lightly. Cheating has long-term consequences for self-esteem, ability to trust, and feelings of security.

Marriage and family therapist Cindy Grajkowski says the most common consequence of betrayal is a traumatic reaction. “People seem to be going through a car accident. They no longer feel safe, cannot sleep, and overreact to everything,” Grajkowski says.

Of course, the behavior of each person who is faced with betrayal is individual. But it is important to understand what effect a partner’s infidelity has on us and what will help us get through what happened, regardless of whether you want to stay together or intend to break the union.

Dr. Carla Marie Manley, a clinical psychologist who specializes in trauma and relationship problems, also believes that cheating is not to be taken lightly. "It's cruel and undermines the foundation of marriage - trust," she says. You should not believe that this is “just sex” - a very important connection has been broken that allows people to stay with each other.

This does not mean that the couple is doomed to part. But very often people ask themselves only one question: “Stay or leave?” But there is another, much more important one: “How can I be healed after what happened?” Several experts have shared what needs to be done before moving forward, whether together or alone.

But very often people ask themselves only one question: “Stay or leave?” But there is another, much more important one: “How can I be healed after what happened?” Several experts have shared what needs to be done before moving forward, whether together or alone.

Step One: Acknowledge Your Past

Grajkowski explains that the trauma a person gets after cheating can bring back the emotions they experienced in the past. If you've been cheated on in the past, if you've been in an abusive or abusive relationship, this can affect how you perceive infidelity and the pain it causes. It is important to consider all this in order to understand what problems may arise in the course of healing.

Dating and relationship expert Cheryl Muir explains that identifying the source of resentment can sometimes be difficult, as cheating affects trust and self-esteem at the same time. “If they are already on shaky ground, then infidelity can trigger an emotional avalanche,” she says. “It is very difficult to navigate in the muddy pool of pain and shame.” But it is important not to push feelings aside - this is the only way to deal with them.

“It is very difficult to navigate in the muddy pool of pain and shame.” But it is important not to push feelings aside - this is the only way to deal with them.

Step Two: Process Your Emotions

Muir says the healthiest way to deal with infidelity is to process all of your emotions. “You have to give yourself time to feel and label them,” she explains. It will sound like this: "I'm sad", "I feel betrayed and angry", "It's hard for me to trust this person." Encountering emotions, we go through them - just like, for example, through the process of mourning.

Step three: avoid self-flagellation

Everything is simple and clear here: if you have been cheated on, it is not your fault. No, it's not that you've gained weight, you don't want to deepthroat, you're too busy with your career or having a baby. “In all the years of my work, I have not met a single person who would have cheated and was not 100% to blame for this,” says Dr. Manley.

Manley.

This does not mean that there were no other problems in the relationship that both parties could contribute to. But the responsibility for infidelity lies solely with the one who decided to go left.

So don't blame yourself: if you get stuck in a cycle of self-blame, you won't be able to get to the root of the pain and truly heal from it. And even more so, don’t let other people shame you: boldly ask everyone who starts to hint that you should be more attentive to your husband, wear lacy lingerie more often, go to 138 Thai oral techniques courses, lose ten kilograms or get rid of mimic wrinkles.

Step Four: Analyze Your Behavior Patterns

If you consistently choose a partner who cheats or mistreats you, then Muir advises being "radically honest" and admitting it. “In such cases, you need to work on self-esteem and increase it to the understanding that you are worthy of a person who treats you well,” she says.

Dr. Manley explains that low self-esteem has a negative effect on the ability to test a potential soul mate. Instead of noticing the warning signals, we ignore them, stepping on the same rake again. “If someone from childhood believes that they do not deserve much, then they will subconsciously look for people who will prove that these beliefs are true,” Muir said.

Step Five: Work on Yourself

To heal from betrayal, Dr. Manley explains, you need to slow down and consciously work on yourself. It's not enough to just say, "It's not my fault!" Self-reflection and self-confidence-building efforts will be required. And this requires strength, time and, possibly, help. First of all, people with low self-esteem will need it - and it doesn’t matter if these are childhood problems or the result of a recent toxic relationship.

Step Six: Practice Trust in Other Relationships

It may be impossible to bring him back to his partner. But just living and building a marriage without trust is very difficult, and therefore you should work to bring it back, not to this person, but to people in general. Muir says friendship is a great place to start doing that. “Practice openness with close friends, share experiences with them, and ask for their support,” she says.

But just living and building a marriage without trust is very difficult, and therefore you should work to bring it back, not to this person, but to people in general. Muir says friendship is a great place to start doing that. “Practice openness with close friends, share experiences with them, and ask for their support,” she says.

You can't let one traitor spoil your years of life. Train trust in platonic relationships - then you will more easily and naturally bring it into love. This does not mean that you have to throw out all the details of life to the first person you meet. But you need to regain confidence that there are people nearby who will not let you down, and then they will really appear. And that's what we need, right?

Have you ever been cheated on?

7 questions about infidelity - about loyalty, pain and childhood trauma. Clinical psychologist answers

Olesya Akhmedzhanova

After 43 years of working with clients and couples, clinical psychologist Janice Spring has collected the most frequently asked questions and answered them in her book Cheating. We publish several answers of Dr. Spring - they will help in recovery after the crisis and tell you what to do next.

We publish several answers of Dr. Spring - they will help in recovery after the crisis and tell you what to do next.

1. “I am the abuser—the one who cheated—but in fact, I am the injured partner too. It hurts me too.”

Affected partners often find it helpful to understand and acknowledge that they, too, have torn their partner's heart apart by their actions and made him more vulnerable to the other person's attention. I am not saying cheating is justified or that hurt partners force their partners to cheat on them. I'm just arguing that infidelity is inherently often the result of an inability to cope with pain and sometimes there is no innocent side in the conflict.

Anatomy of Cheating Course

Paul's infidelity brought him and his wife to my office. His wife, an injured partner, vented anger and resentment. Paul sat, soaking up her pain. But during the next individual session, he told me, “I know I did a bad thing. I don't make excuses. But, with your permission, my wife drinks. And when she drinks, she becomes angry. She speaks to me in such a way that I feel disgusted with myself - in the same way my mother verbally humiliated me.

And when she drinks, she becomes angry. She speaks to me in such a way that I feel disgusted with myself - in the same way my mother verbally humiliated me.

Source

He paused and then said something I will never forget: “I could build the Taj Mahal for my wife, but she would only see bird shit on the roof. I contacted another woman with whom I felt good, I felt that I was appreciated. I know that I did wrong. I know that I hurt my wife terribly, but she is not an innocent sheep: she also hurt me.”

In order to earn forgiveness and possibly get closer again, both partners must be ready to listen to each other's pain with an open heart and without argument and let their partner feel that he is heard and understood. They must accept their share of responsibility for allowing a third person to come between them. Sometimes this share of responsibility is zero, sometimes it is significant.

2. “My husband had sex with his mistress in our house: in the shower, on the bed, in the nursery.

I cannot enter a house without being disgusted. It pisses me off how he poisoned my personal space. Should we move?"

I cannot enter a house without being disgusted. It pisses me off how he poisoned my personal space. Should we move?" Maybe. Some couples, some partners need to start from scratch. Moving doesn't necessarily solve the problem, but sometimes the abuser's willingness to do what I call high-cost trust-building activities can help heal the hurt partner.

There is another way, which I call rewriting traumatic memories. It consists in the fact that during recovery, the injured partner (namely the victim) takes the initiative and offers the wrong partner to help him rewrite traumatic memories and create new, more pleasant associations. For example, an injured partner might say, “You took her to Paris; I want you to take ME to Paris (or wherever I have always wanted to go)." Or an injured partner decides to renovate the bathroom to remodel and transform the space of the house. Of course, the couple should deal with what caused the betrayal and work out weaknesses, but new associations can also be beneficial.

Source

Another way to rewrite traumatic memories is to burn all letters, photos, and gifts from a lover. The wrong partner must organize this, although the injured partner can also help, participate and contribute.

3. “I am from Egypt. My father had two wives and several children from each of them. I am the first daughter from my first marriage. I always felt that he loved his second family - the children from that marriage - more than me. When my husband cheated on me, all my past sadness and anxiety resurfaced - there was a feeling that I was replaced and I was not worthy of love. This not normal?"

Not only is this not abnormal, it is completely natural. This is how trauma works in relationships. I call it your vulnerability channel. It helps to understand what is normal. Trauma from early childhood usually never fully heals and remains sensitive and open. When something subsequently happens that rips off the crust and opens the wound, you may feel that you are fully living all the pain that you have accumulated in this channel. Your mind remembers and resurrects past relationship traumas and the meanings you attach to them with the same pain and horror as when you first experienced them.

Your mind remembers and resurrects past relationship traumas and the meanings you attach to them with the same pain and horror as when you first experienced them.

Source

You may find it helpful to know that your belief that your father loved you less than other children may be false. Maybe you are right and your reaction is understandable. I will allow myself to hope that you can show the same sympathy for yourself as for any other person, if he tells you the same story.

Sometimes family wounds affect not only the reaction of the injured partner, but also the reason why the second partner cheated.

When Henry was four years old, his mother got angry with him and left him in a large shopping mall. This childhood trauma formed the basis of his persistent belief that the people you love will leave you and that in order to protect yourself, you should not get close to anyone. A year after his 24th birthday and marriage, Henry began dating women he found online. He did not wonder why he was doing this, but later, in the sessions, reflecting on his behavioral patterns and choices, he realized what an unspoken contract he had made with himself at an early age: “To love means to lose. Never again allow yourself to get close to anyone."

He did not wonder why he was doing this, but later, in the sessions, reflecting on his behavioral patterns and choices, he realized what an unspoken contract he had made with himself at an early age: “To love means to lose. Never again allow yourself to get close to anyone."

Knowing your childhood traumas and how they affected you will protect you from past patterns of behavior that you needed at some point in your life, but now only get in the way.

4. “My husband cheated on me. He says that it's all over and that woman means nothing to him. How can I trust him? I want to meet her and ask a few questions about their relationship. Is this a good idea?

Affected partners often want to meet their lover for many reasons: from a simple desire to know what this person looks like, to the intention to tell him everything that boils over. It is important that you clearly understand what exactly you want to achieve from a personal meeting and that you are behaving in accordance with your intentions.

One woman, whose husband cheated on her with a secretary, rushed into his office with a baby in her arms, threw it on her mistress's table and shouted at the whole office: “You ruined this family! You vile bitch! I hope you're proud of yourself!" The injured wife vented her resentment and anger in front of all her husband's colleagues - an act that she later bitterly regretted.

Source

Yes, I know other cases where the meeting of the injured partner with the lover was very helpful.

When Tammy found out that her husband Tom had cheated on her with Susan, he wrote Susan a farewell message and sent it over the phone in Tammy's presence. But one day, when Tom was in the shower, Tammy took his phone and wrote a message to Susan on his behalf, offering to meet the next day at her favorite bar. When Susan came and saw Tammy, she initially wanted to run away, but Tammy politely asked her to stay. “I have no desire to harm you,” Tammy assured her. “Just the opposite: maybe you can help me. ” Susan agreed to answer a few questions.

” Susan agreed to answer a few questions.

It was a strange meeting. The injured wife shared hidden fears with her mistress (her new best friend), and the mistress comforted the injured partner. Susan said to Tammy, “Listen. I have no other reason to tell you this than the truth: your husband loves you and your children in a way that he never loved me. He hooked up with me because he was lonely. And he was in pain. He felt that you needed him only for the sake of money in the account, and nothing else interested you in him. Both of you should work on your marriage. I pose no threat to you." It was good advice—advice that the injured partner could believe—helped her let go of her lover worries and start working on rebuilding her marriage.

5. “I am what you call an unfaithful partner. I am thinking of leaving my wife and family for the love of my life, Joanna. We have a lot in common in bed, and we also go to the same wine tasting club. My wife does not drink alcohol and does not like sex.

Am I missing something in this case? Any reason to stay in a bad marriage and give up a chance at happiness?"

Am I missing something in this case? Any reason to stay in a bad marriage and give up a chance at happiness?" Who am I to tell you that you should not live your only life with someone who brings you joy? However, in your case, you can make two fatal mistakes.

- First, alcohol and other drugs can cloud your perception.

Today they unite you with your girlfriend, but over time, when you are in a permanent relationship, they can ignite conflicts between you and make it impossible to put up with each other's differences.

- Second: romantic love blinds the eyes.

Because we know from a study by psychologists John and Julia Gutman that the happiest couples in America never decide 69% of my conflicts, I would suggest that before proceeding to take action, make a list of the qualities of your mistress that annoy you. If you can't write it down, just keep in mind that you don't know the person well enough yet to get an answer to your question.

There is a divisive tendency in romantic attraction: exaggerating the negative qualities of your legitimate partner and idealizing your illegitimate partner.

I am not saying that one person cannot be better for you than another. But remember that romantic love sometimes distorts vision. Add to this alcohol and other substances, and your eyes will become even more cloudy.

After 15 years of marriage, Mark and Paley came to my office asking if it makes sense for them to stay together. By that time, Mark was living with another woman with whom he shared many addictions, including alcohol. Paley was unhappy and admitted that she was a bad wife - she only thinks about children and does not respond to Mark's sexual needs. She asked him to give her one more chance, but he decided to divorce and live with his girlfriend. Paley hired a lawyer, received a substantial alimony, and went to Canada with her children, closer to her parents.

Four months passed and I met Mark. He drank a lot and, finding himself in a normal relationship with his girlfriend, he realized that he was mired in quarrels with her. Moral of the story: Are some relationships better than others? No, just marriage is hard. Throw in alcohol and cheating and it gets even more difficult.

He drank a lot and, finding himself in a normal relationship with his girlfriend, he realized that he was mired in quarrels with her. Moral of the story: Are some relationships better than others? No, just marriage is hard. Throw in alcohol and cheating and it gets even more difficult.

6. “My husband cheated on me while we were undergoing fertility treatment. It's enough that he has low sperm motility, but if I endure extremely painful, excruciating procedures in order for us to have a child, he could at least be faithful. Are we hopeless?"

After cheating, there is little that an unfaithful partner can do to make amends, but one of the most important steps is to make a list of what I call contributing factors. They do not excuse or justify adultery or even share the blame for it.

Source

Usually, such a list helps to identify why the unfaithful partner has become vulnerable to the attention of another person. Abuse of alcohol and other drugs, failure to understand or resolve relationship problems, avoidance of intimacy are the most common reasons for cheating.

Together partners should explore: why did the betrayal happen? What does she say about you, about me, about us? How did each of us create space between us?

One of the newest contributory factors that I have encountered in my private practice is infertility treatment. Physicians often do not warn clients of the intense inner tension and tension they will face in trying to conceive. It's not just unfun and unpleasant, it can be painful and uncomfortable. The process may be accompanied by flashes of deep despair, silent or not silent accusations, or sudden and violent mood swings fueled by endogenous chemical releases. Couples must prepare for this emotional roller coaster of not riding each other up and coping with the deep sense of loss, worthlessness, and resentment that comes when expensive treatments don't pay off. Under these conditions, it is easy to become attached to someone else.

You should know that often in such situations an unfaithful partner is attracted not to a mistress, but to how he feels next to this person: alive, strong, sexy, desirable, that is, he experiences everything that he does not feel when , often to no avail, tries to please a partner and create a new life.

7. “My fiancee wants us to visit a family psychologist before the wedding. We do not have any problems, and it seems to me that in this case we will just ask for trouble. I do not understand something?"

I will never forget an incident from my early practice as a clinical psychologist. At that time, I had two offices: one at home, the other in the clinic. One day while I was at home with my teenage sons and their friend Jonathan, I got a call from a mother whose son was about to get married. She asked: “I would like to know if I can pay for ten family sessions for him and his fiancee? Many years ago, my husband and I went to counseling, and it helped us a lot.”

After discussing all the details with this woman, I hung up and saw Jonathan laughing hysterically on my kitchen floor. “Oh my God,” he yelled. - Well, a couple! They are not yet married, but already go to family counseling. Here is a scream!

All I had time to think was, "Jonathan, you're an idiot.