Out of body experience depression

Mental Health: Depersonalization Disorder

Written by WebMD Editorial Contributors

In this Article

- What Are the Symptoms of Depersonalization Disorder?

- What Causes Depersonalization Disorder?

- How Common Is Depersonalization Disorder?

- How Is Depersonalization Disorder Diagnosed?

- How Is Depersonalization Disorder Treated?

- What Is the Outlook for People With Depersonalization Disorder?

- Can Depersonalization Disorder Be Prevented?

Depersonalization disorder is marked by periods of feeling disconnected or detached from one's body and thoughts (depersonalization). The disorder is sometimes described as feeling like you are observing yourself from outside your body or like being in a dream. However, people with this disorder do not lose contact with reality; they realize that things are not as they appear. An episode of depersonalization can last anywhere from a few minutes to (rarely) many years.

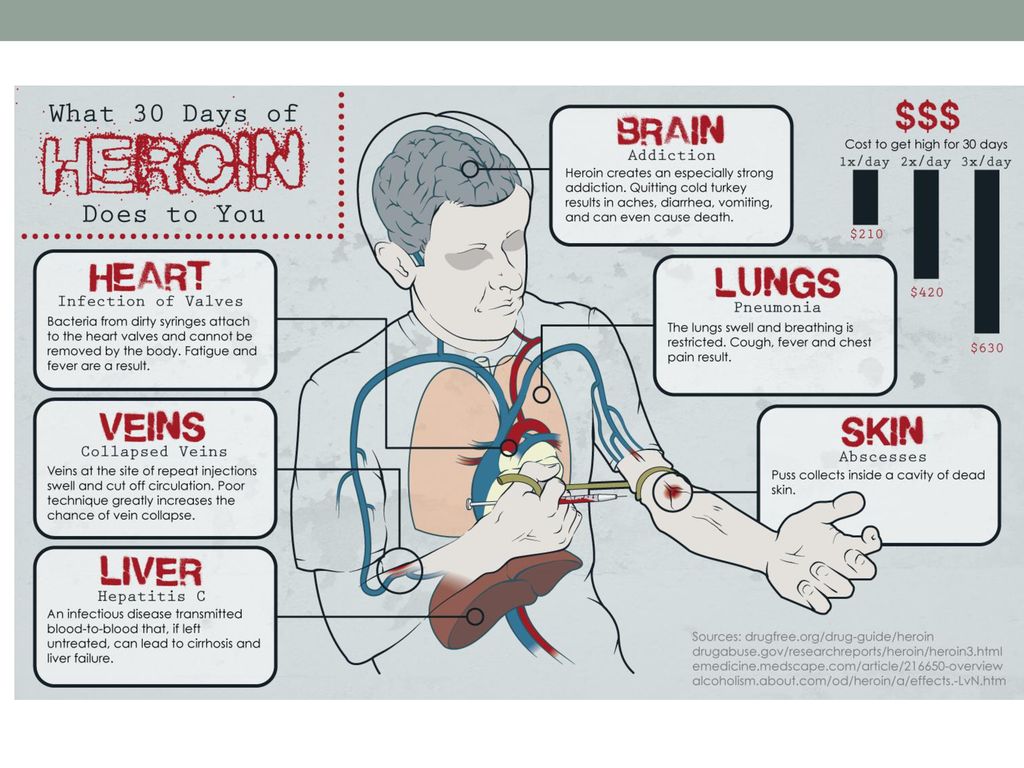

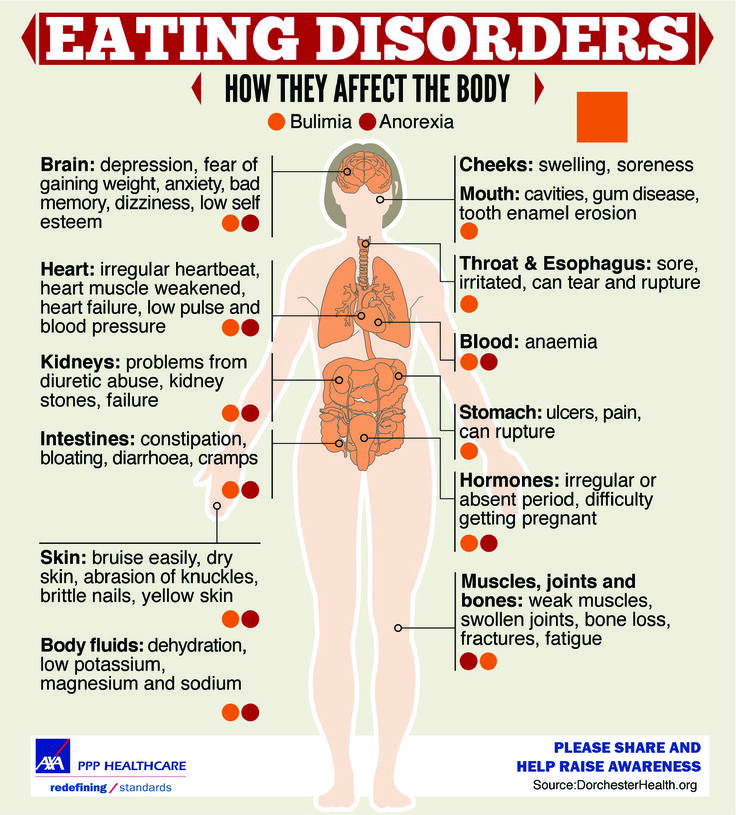

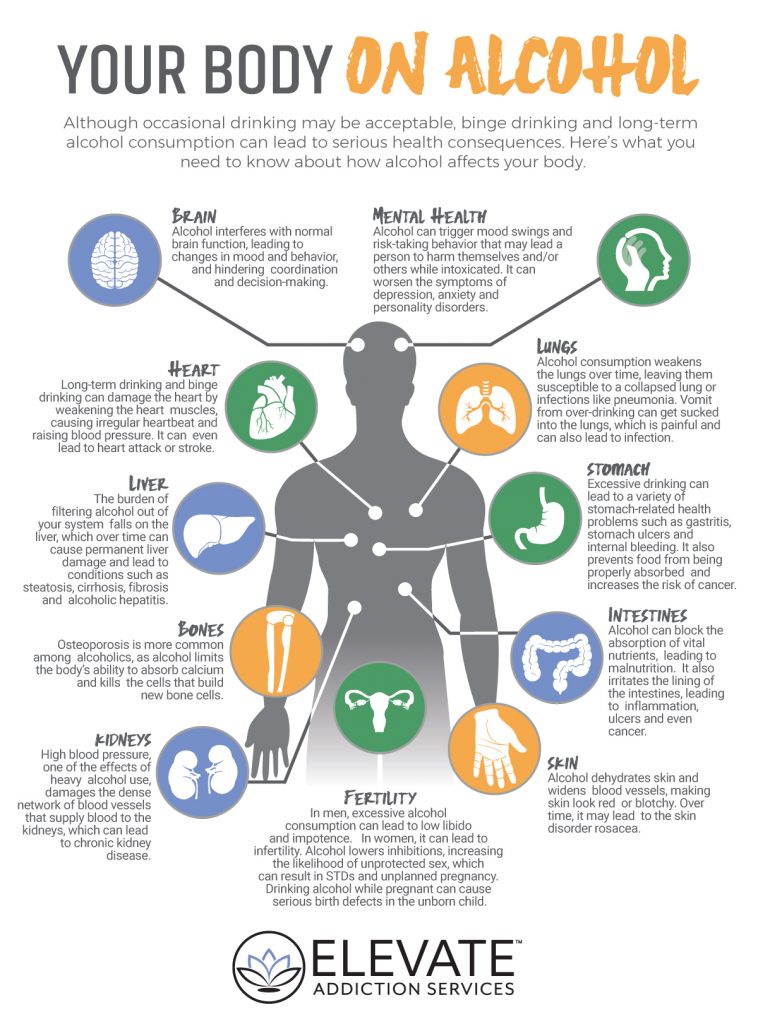

Depersonalization also might be a symptom of other disorders, including some forms of substance abuse, certain personality disorders, seizure disorders, and certain other brain diseases.

Depersonalization disorder is one of a group of conditions called dissociative disorders. Dissociative disorders are mental illnesses that involve disruptions or breakdowns of memory, consciousness, awareness, identity, and/or perception. When one or more of these functions is disrupted, symptoms can result. These symptoms can interfere with a person's general functioning, including social and work activities and relationships.

What Are the Symptoms of Depersonalization Disorder?

The primary symptom of depersonalization disorder is a distorted perception of the body. The person might feel like they are a robot or in a dream. Some people might fear they are going crazy and might become depressed, anxious, or panicky. For some people, the symptoms are mild and last for just a short time. For others, however, symptoms can be chronic (ongoing) and last or recur for many years, leading to problems with daily functioning or even to disability.

For others, however, symptoms can be chronic (ongoing) and last or recur for many years, leading to problems with daily functioning or even to disability.

What Causes Depersonalization Disorder?

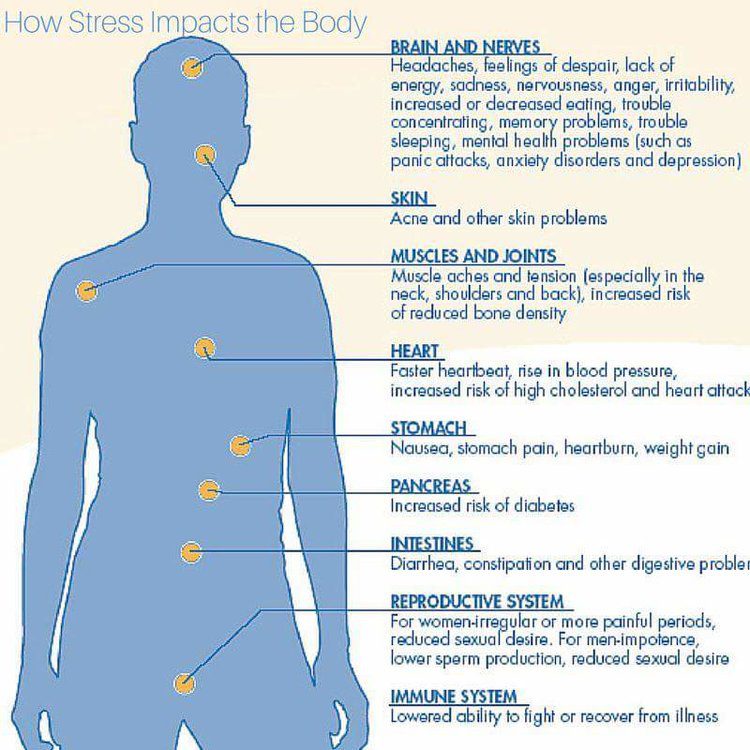

Little is known about the causes of depersonalization disorder, but biological, psychological, and environmental factors might play a role. Like other dissociative disorders, depersonalization disorder often is triggered by intense stress or a traumatic event -- such as war, abuse, accidents, disasters, or extreme violence -- that the person has experienced or witnessed.

How Common Is Depersonalization Disorder?

Depersonalization can be a rare symptom in several psychiatric disorders and sometimes occurs after experiencing a dangerous situation, such as an assault, accident, or serious illness. Depersonalization as a separate disorder is quite rare.

How Is Depersonalization Disorder Diagnosed?

If symptoms of depersonalization disorder are present, the doctor will begin an evaluation by performing a complete medical history and physical exam. Although there are no lab tests to specifically diagnose dissociative disorders, the doctor might use various diagnostic tests, such as imaging studies and blood tests, to rule out physical illness or medication side effects as the cause of the symptoms.

Although there are no lab tests to specifically diagnose dissociative disorders, the doctor might use various diagnostic tests, such as imaging studies and blood tests, to rule out physical illness or medication side effects as the cause of the symptoms.

If no physical illness is found, the person might be referred to a psychiatrist or psychologist, health care professionals who are specially trained to diagnose and treat mental illnesses. Psychiatrists and psychologists use specially designed interviews and assessment tools to evaluate a person for a dissociative disorder.

How Is Depersonalization Disorder Treated?

Most people with depersonalization disorder who seek treatment are concerned about symptoms such as depression or anxiety, rather than the disorder itself. In many cases, the symptoms will go away over time. Treatment usually is needed only when the disorder is lasting or recurrent, or if the symptoms are particularly distressing to the person.

The goal of treatment, when needed, is to address all stresses associated with the onset of the disorder. The best treatment approach depends on the individual and the severity of their symptoms. Psychotherapy, or talk therapy, is usually the treatment of choice for depersonalization disorder. Treatment approaches for depersonalization disorder may include the following:

The best treatment approach depends on the individual and the severity of their symptoms. Psychotherapy, or talk therapy, is usually the treatment of choice for depersonalization disorder. Treatment approaches for depersonalization disorder may include the following:

- Psychotherapy: This kind of therapy for mental and emotional disorders uses psychological techniques designed to help a person better recognize and communicate their thoughts and feelings about psychological conflicts that could lead to depersonalization experiences. Cognitive therapy is a specific type of psychotherapy that focuses on changing dysfunctional thinking patterns.

- Medication: Medications are generally not used to treat dissociative disorders. However, if a person with a dissociative disorder also suffers from depression or anxiety, they might benefit from an antidepressant or anti-anxiety drug. Antipsychotic medications are also sometimes used to help with disordered thinking and perception related to depersonalization.

- Family therapy: This kind of therapy helps to educate the family about the disorder and its causes, as well as to help family members recognize symptoms of a recurrence.

- Creative therapies (art therapy, music therapy): These therapies allow the patient to explore and express their thoughts and feelings in a safe and creative way.

- Clinical hypnosis: This is a treatment technique that uses intense relaxation, concentration, and focused attention to achieve an altered state of consciousness or awareness, allowing people to explore thoughts, feelings, and memories they might have hidden from their conscious minds.

What Is the Outlook for People With Depersonalization Disorder?

Complete recovery from depersonalization disorder is possible for many patients. The symptoms associated with this disorder often go away on their own or after treatment that help the person deal with the stress or trauma that triggered the symptoms. However, without treatment, additional episodes of depersonalization can occur.

However, without treatment, additional episodes of depersonalization can occur.

Can Depersonalization Disorder Be Prevented?

Although it might not be possible to prevent depersonalization disorder, it might be helpful to begin treatment in people as soon as they begin to show symptoms. Furthermore, quick intervention following a traumatic event or emotionally distressing experience might help reduce the risk of developing dissociative disorders.

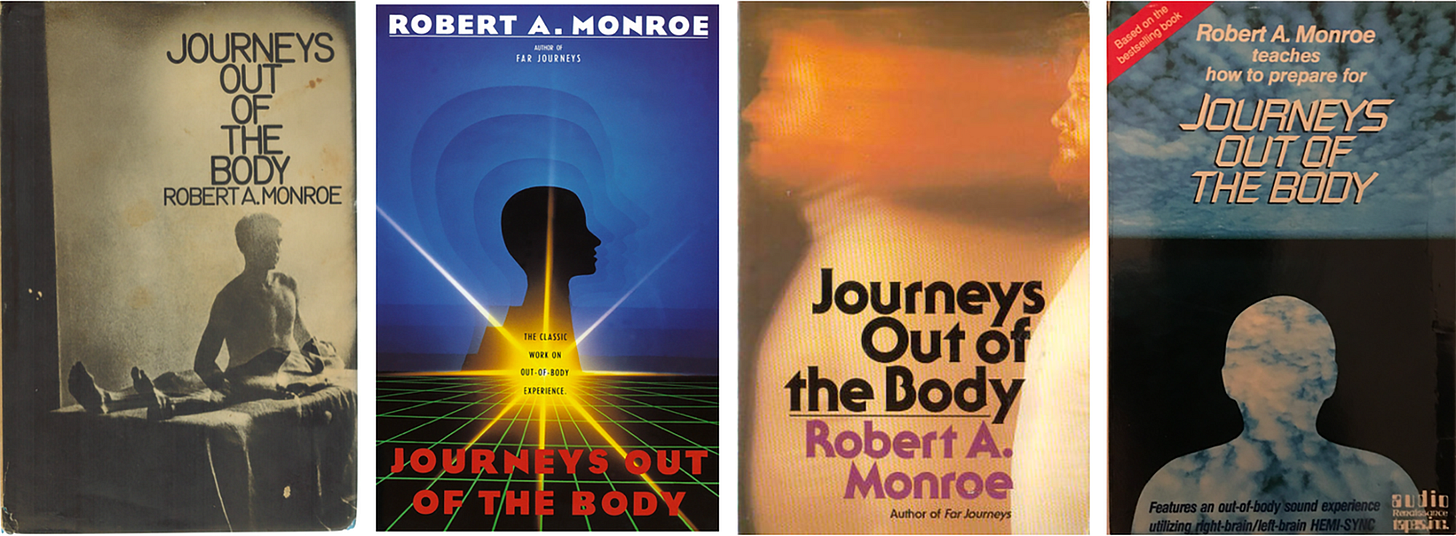

Depersonalization Disorder: An Out of Body Experience

Natasha Tracy

Depersonalization disorder may be described as an out of body experience as the main symptom of depersonalization is a feeling of detachment or a feeling that one is an observer of one's thoughts, feelings or body. While most people do experience symptoms of depersonalization in their lives at some time, depersonalization becomes a dissociative disorder when it begins to interrupt daily living and becomes very upsetting. Living with depersonalization disorder may feel like you're watching a movie of your own life, like you're in a dream or that the whole world is "unreal."

Living with depersonalization disorder may feel like you're watching a movie of your own life, like you're in a dream or that the whole world is "unreal."

Derealisation is associated with depersonalization and it is where a person feels like the objects in his or her environment are changing shape or size, like their surroundings aren't real or that people are inhuman or automated. Derealisation is not a diagnosis in its own right but, rather, is considered part of depersonalization.

People living with depersonalization or derealisation symptoms may feel like they're "going crazy" and may try to check to see if things are actually real.

Define Depersonalisation Disorder

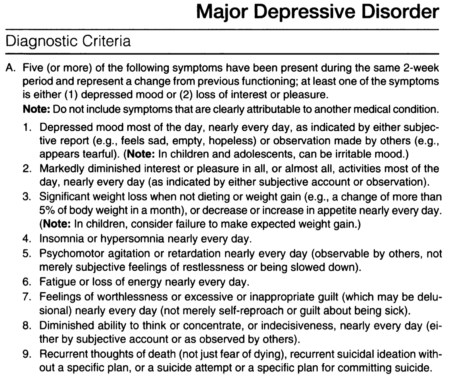

The Diagnostic and Statistical Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) defines depersonalization disorder as the occurrence of persistent or recurrent episodes of depersonalization and/or derealisation that are not associated with another illness and cause significant distress. Depersonalization symptoms must not be attributable to substance use.

Depersonalization symptoms must not be attributable to substance use.

According to Medscape, the signs of depersonalization disorder also include:

- Alertness and orientation in some areas (but not others)

- Limited relatedness and eye contact

- Preoccupation and irritability

- Distressed facial expression with constricted emotion

- Limited to fair reasoning and judgment

A person with depersonalization disorder may feel like a robot like his or her body is distorted or like he or she can't control his or her own actions.

What Causes Depersonalisation Disorder?

What causes depersonalization disorder is not fully understood, but it is thought that it is linked to a chemical imbalance in the neurotransmitters of the brain. This imbalance may make the brain vulnerable to depersonalization disorder when in states of extreme stress.

According to the Mayo Clinic, causes of depersonalization disorder may include:

- Childhood trauma such as witnessing domestic violence or being abused

- Growing up with a significantly impaired parent, such as by mental illness

- Suicide or unexpected death of a loved one

- Severe stress such as relationship, financial or work-related pressures

- Severe trauma such as a car accident

Depersonalization Disorder Treatment

Treatment for depersonalization disorder typically consists of psychotherapy (sometimes called "talk" therapy) but may also include medication to treat some of the depersonalization disorder symptoms. Therapy aims to help an individual understand why he or she experiences depersonalization symptoms in the first place and helps the individual gain control over his or her symptoms. According to the Mayo Clinic, two types of psychotherapy that can treat depersonalization disorder include cognitive behavioral therapy and psychodynamic therapy, although some sources say that psychotherapy is not beneficial.

Therapy aims to help an individual understand why he or she experiences depersonalization symptoms in the first place and helps the individual gain control over his or her symptoms. According to the Mayo Clinic, two types of psychotherapy that can treat depersonalization disorder include cognitive behavioral therapy and psychodynamic therapy, although some sources say that psychotherapy is not beneficial.

No medications are Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of depersonalization or derealisation symptoms, but some medications have been shown to help. Typically, medications include antidepressants and tranquilizers.

article references

APA Reference

Tracy, N. (2022, January 4). Depersonalization Disorder: An Out of Body Experience, HealthyPlace. Retrieved on 2023, April 21 from https://www.healthyplace.com/abuse/dissociative-identity-disorder/depersonalization-disorder-an-out-of-body-experience

Last Updated: January 12, 2022

Medically reviewed by Harry Croft, MD

More Info

10 Ways People Self-Harm, Self-Injure

Diagnostic Codes for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Date Rape Victims and the Effect of Date Rape

Emotionally Abusive Men and Women: Who Are They?

Considering Suicide? STOP!

Signs of Domestic Violence, Domestic Abuse

Why Do Battered Women Stay in Abusive Relationships?

the problem of typology and constitutional predisposition

Anxious depression is one of the key problems of modern clinical psychiatry in pathogenetic and methodological aspects. Its scale and relevance is evidenced by the fact that the very phenomenon of anxious depression goes beyond the status of a medical problem, affecting the deepest aspects of human existence associated with the saturation of modern life with stressful events and other negative social trends, which leads to an exponential increase in the frequency of depressions (including anxiety disorders). ).

Its scale and relevance is evidenced by the fact that the very phenomenon of anxious depression goes beyond the status of a medical problem, affecting the deepest aspects of human existence associated with the saturation of modern life with stressful events and other negative social trends, which leads to an exponential increase in the frequency of depressions (including anxiety disorders). ).

Clinical observations are of particular importance in modern conditions, indicating a modification of the psychopathological manifestations of depression: typical phenomena can be relegated to the background or completely replaced by anxious equivalents [17, 21, 25, 29, 59, 136].

The multiplicity of links between anxiety and depression raises a number of questions about the nature, boundaries and clinical unity of anxious depression as an independent psychopathological entity (cohesive entity), the legitimacy of including both autochthonous conditions and reactions to stressful influences in this group. In this series, the questions of assessing the relationship between anxiety-depressive disorder and the personality of the patient in whom this disorder is formed remain the least studied (the ratio of anxiety depression - personality disorders is covered in the second part of this review).

In this series, the questions of assessing the relationship between anxiety-depressive disorder and the personality of the patient in whom this disorder is formed remain the least studied (the ratio of anxiety depression - personality disorders is covered in the second part of this review).

In existing classifications (ICD-10, DSM-IV-TR), depressive disorders are separated from anxiety disorders as independent categories. Within the latter, coexisting depressive and anxiety disorders can be presented not only in the form of developed psychopathologically completed syndromes, but also in subthreshold, subsyndromal, masked forms.

A significant contribution of anxiety to the structure of depression, judging by the data of Russian [15, 19] and foreign [164, 196, 213] authors, seems indisputable, but the existence of anxious depression as an independent clinical (and taxonomic) unit is the subject of discussion. This problem is considered in this review in two sections, the first of which is devoted to the question of the unity/heterogeneity of anxious depression, and the second - to its relationship with personality disorders.

Anxious depression - etiopathogenetic and clinical unity or a heterogeneous disorder?

The development of the problem in the title of this section is carried out in different research traditions, which can be reduced to two main directions: one of them is based on the concept of psychogenesis (psychoanalysis, psychodynamic psychiatry, behavioral, cognitive psychology), the other - on the natural science paradigm of depression (epidemiology, genetics, neurobiology, clinic).

In the studies of the first direction, the authors [54, 71, 80, 114], who adhere to the psychoanalytic [90], behavioral [185], and psychological [58] interpretations of mental disorders, qualify anxiety and depression as closely related phenomena. The latter are determined by universal mechanisms existing initially or acquired in the process of modeling learned behavioral patterns and/or cognitive schemes. This provides protection from suppressed unconscious impulses and / or stressful influences that pose a threat and reduce adaptive resources and the ability to control the situation. From here the consciousness of helplessness and hopelessness is derived (in these terms, researchers describe the picture of depression) [1] .

From here the consciousness of helplessness and hopelessness is derived (in these terms, researchers describe the picture of depression) [1] .

Let us now turn to the work based on the medical model of depression.

The results of epidemiological studies based on the principles of modern evidence-based medicine suggest that there are statistically significant positive correlations between the categories "depression" and "anxiety" [83].

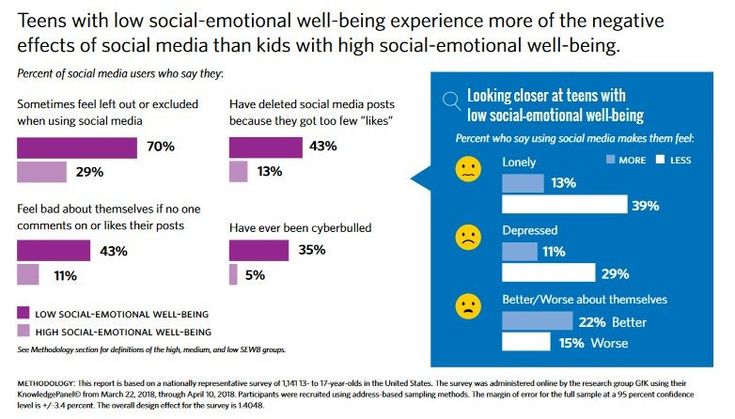

Since the late 80s - early 90s of the last century, high rates of comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders have been established. The prevalence of conditions in the structure of which a combination of typical depressive (low mood, lethargy, pessimism) and anxiety (tension, insomnia, irritability) symptoms are detected exceeds the frequency of “pure” depressions in the ratio of 7:1 in the UK population [157]. According to L. Andrade et al. [50], the combination of major depression and panic disorder occurs 11 times more often than each of these forms of pathology, and the role of the comorbidity factor is manifested by the aggravation of both syndromes, and, in particular, by an increase (almost 3-fold [109, 126]) hospitalization rates, risk of relapse and suicide attempts, and reduced psychosocial functioning and quality of life [50, 202, 211]. At the same time, the values of comorbidity indicators vary widely - from 22 to 91% [73, 76, 153, 195].

At the same time, the values of comorbidity indicators vary widely - from 22 to 91% [73, 76, 153, 195].

In later works, the average value of the discussed indicator is 58% [109, 126]. The fact of a high comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders is confirmed by the results of a large-scale epidemiological study (7076 observations) performed by R. de Graaf et al. [81] in the framework of the national program for the study of mental health of the population of the Netherlands. Anxiety disorders are detected in 46% of men and 57% of women (aged 18 to 64 years) with an affective pathology diagnosed during their lifetime (lifetime prevalence). Similar results are reported in a US epidemiological series (NESARC, NCS-R) [2] , performed using the method of sequential analysis of time series (time-series analyzes) and allowing to estimate the prevalence of the studied comorbid disorders during life (lifetime prevalence) [97-99, 126-131] [3] .

As assessed by D. Hasin et al. [102] (NESARC program) the proportion of generalized anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder - GAD), comorbid major depression is 71%, and in the reverse assessment (from anxiety to depression) - 90% [97]. According to another longitudinal American project - NCS-R (9982 English-speaking respondents aged 18 years and older, examined using the WHO structured diagnostic interview - CIDI) [126, 130, 212], the comorbidity of depression with various subtypes of anxiety disorders - social phobias, simple phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, panic attacks are respectively 28, 25, 17, 16 and 10%. The comorbidity rate of generalized anxiety with major depression is estimated at 62%; in panic disorder, 35% of patients develop major depression, and another 10% develop dysthymia.

Hasin et al. [102] (NESARC program) the proportion of generalized anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder - GAD), comorbid major depression is 71%, and in the reverse assessment (from anxiety to depression) - 90% [97]. According to another longitudinal American project - NCS-R (9982 English-speaking respondents aged 18 years and older, examined using the WHO structured diagnostic interview - CIDI) [126, 130, 212], the comorbidity of depression with various subtypes of anxiety disorders - social phobias, simple phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, panic attacks are respectively 28, 25, 17, 16 and 10%. The comorbidity rate of generalized anxiety with major depression is estimated at 62%; in panic disorder, 35% of patients develop major depression, and another 10% develop dysthymia.

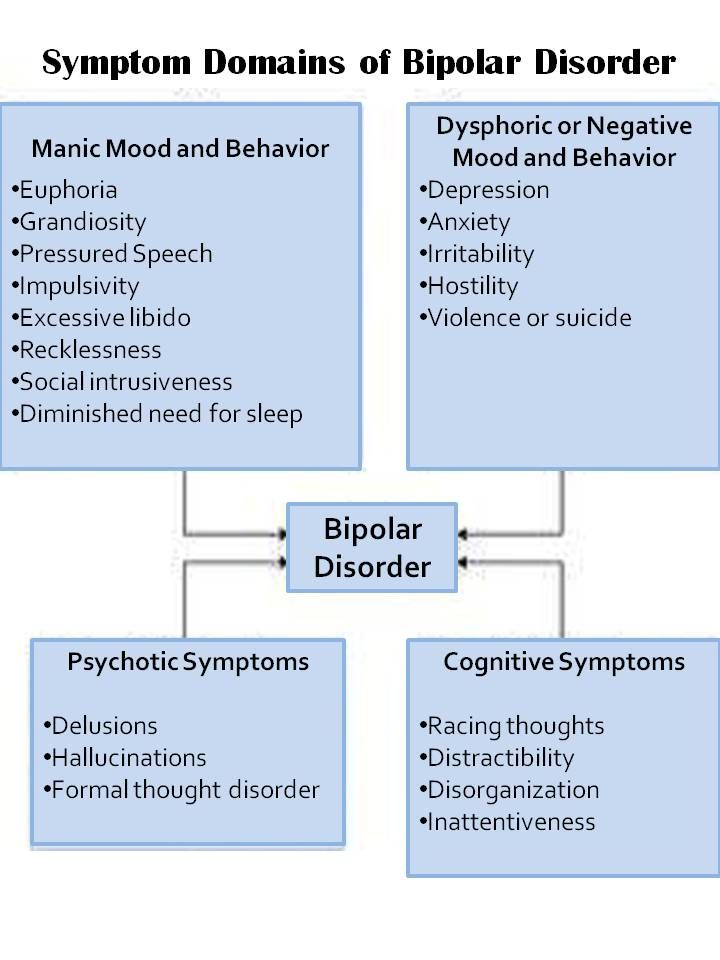

Analysis of data from the Zurich study from 1979-1999 allowed J. Angst et al. [52] state that GAD is statistically significantly associated (odds ratio - OR [4] - is 2. 6 - 7.4; mean 4.3) with bipolar affective disorder (BAD) [5] - GAD overlaps with BAD type II in 32.4% of cases. In a later work performed with the participation of J. Angst [158], this representation is extrapolated to the relationship of GAD with BAD type I: in these cases, the OR averages 9.4 with a spread of values of this indicator 6.2-14.2. A. Ruscio et al. [179, 180] (NCS-R project) specify the shares of BAD in patients with other subtypes of anxiety disorders: obsessive-compulsive - 23.4%, sociophobic - 13.8%.

6 - 7.4; mean 4.3) with bipolar affective disorder (BAD) [5] - GAD overlaps with BAD type II in 32.4% of cases. In a later work performed with the participation of J. Angst [158], this representation is extrapolated to the relationship of GAD with BAD type I: in these cases, the OR averages 9.4 with a spread of values of this indicator 6.2-14.2. A. Ruscio et al. [179, 180] (NCS-R project) specify the shares of BAD in patients with other subtypes of anxiety disorders: obsessive-compulsive - 23.4%, sociophobic - 13.8%.

The results of the epidemiological studies discussed above extend to empirical experience both in the psychiatric hospital and in primary care settings. According to a special study assessing the prevalence of depression with anxiety disorders in hospitalized patients (429observations) [209], this figure is estimated at 49%, which reflects the significant contribution of such forms to the structure of affective disorders. In general medicine, rates of comorbidity between depression and anxiety exceed those estimated for a specialized network: more than 75% of patients in this cohort diagnosed with major depression also have a current anxiety disorder [167, 182].

Analysis of depression and anxiety disorders in the context of chronological comorbidity [77, 82] has led to the concept that anxiety is considered as a predictive validator [6] major depression. In accordance with this concept, the formation of anxiety precedes and increases the risk of developing depression, acquiring special significance when exposed to stressful events [105, 107].

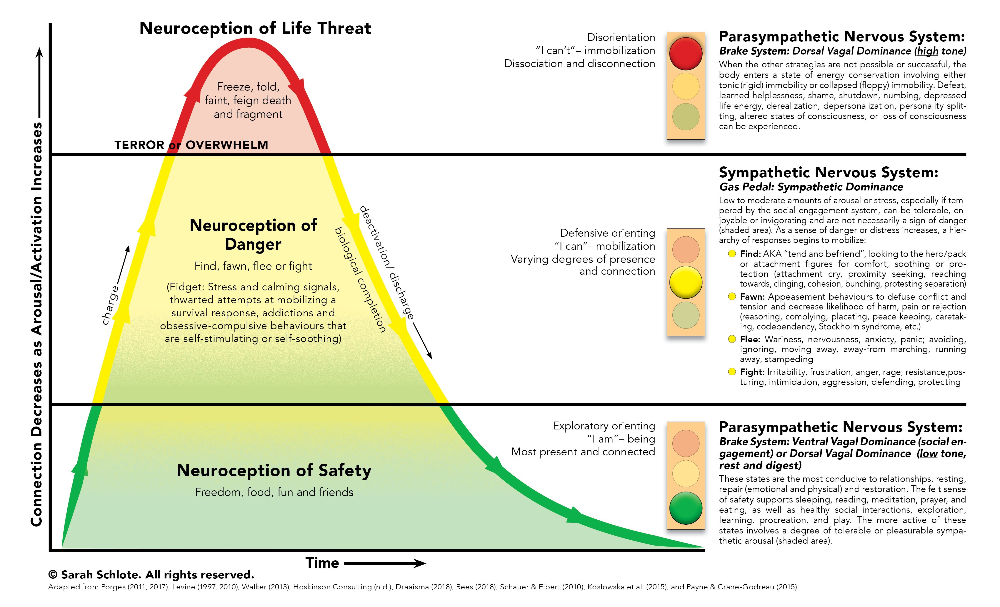

There is also a point of view about the existence of a common neurotic factor between depression and anxiety (“general distress factor” [200, 201]), the impact of which is provided by common mechanisms responsible for vulnerability to stress. This universal factor, represented in the dimensional model [75, 204] as a deficit of positive emotionality and anxiety with an increased readiness to respond to stress (hyperarousal), becomes the driving force that triggers negative affect. Under such conditions, the role of significant stressors (interpersonal conflict, some forms of loss, and other life shocks) is reduced to identifying anxiety that manifests itself at the clinical level [70, 79, 87, 174]. Anxiety itself, in turn, can act as an additional decompensating stressor that aggravates (especially in patients with a genetic/family predisposition) the manifestations of major depression.

Anxiety itself, in turn, can act as an additional decompensating stressor that aggravates (especially in patients with a genetic/family predisposition) the manifestations of major depression.

The results of etiopathogenetic studies on the analysis of hereditary biological relationships between anxiety and depression (genealogical, familial, twin, population, molecular genetic) allow us to put forward the concept of general genetic diathesis. This concept is supported by comparative data on a high aggregation of anxiety and depressive disorders among first-degree relatives (parents, non-twin siblings) in samples of probands diagnosed with depression or anxiety disorder [121, 193] [7] . Such a relationship is revealed within several generations. A unique series of clinical genetic studies was carried out by K. Kendler [117, 119, 120, 124] based on the Virginia population register. Its genealogical section included 5,877 probands and 10,331 parents, which revealed familial aggregation rates for major depression and generalized anxiety and statistically significant correlations ( p <0. 001; OR=1.88) between the studied traits.

001; OR=1.88) between the studied traits.

The discussed genealogical concept is supported by the authors of works performed by the twin method [107, 155, 175]. In particular, in the twin section of the Virginia program by K. Kendler in [117, 118, 122, 123, 125], performed using modern statistical approaches (multivariate twin modeling, etc.), genetic correlations for such factors as participation of additive genes (the contribution of the latter is 2 times higher in monozygotic pairs), the role of environmental factors and conditions of individual development (their effect is equivalent). The position of the authors is to confirm the existence of an internal, environmentally independent genetic risk that determines the correlation of hereditary mechanisms of major depression and “anxious misery” [106, 107, 125], which makes it possible to assess anxious depression as a clinically significant phenotype. [155, 160] [8] .

The fact that the comorbidity of major depression with anxiety disorders is based on the existence of proven precursor/antecedent validators reflecting the hereditary affinity of anxiety and depression allows geneticists and authors of basic research in other areas of neuroscience [9] to join the proposal to distinguish anxiety depression in as a separate category [96, 107, 155], put forward in the preparation of the draft DSM -V [10] .

Turning to the discussion of the problem of the unity of anxiety and depression in the clinical aspect, it must be emphasized that the difficulties associated with the analysis of the problem in this aspect are largely due to the uncertainty in the definitions of anxiety as a psychophysiological mechanism of adaptive response to external stimuli, anxiety as a characterological feature and disorganizing the general emotional-sensory tone and behavior of pathological anxiety, considered as a psychopathological formation.

According to researchers [22, 31], this kind of difficulty is associated with differences in understanding the boundaries and relationships between anxiety and depression. The interpretation of the relationship between these categories allows the following two possibilities.

As heterogeneous disorders, anxiety and depression can only be considered at the level of the borderline psychopathological register. Under these conditions, the existence of anxiety disorders (panic attacks, generalized anxiety, social phobias, etc. ) as an independent psychopathological formation seems to be an indisputable fact, but such independence is realized exclusively within the reactive (adaptive) states and dynamics of personality disorders (PD). When it comes to disorders of a more severe - affective register (recurrent, bipolar depression, dysthymia), anxiety and depression act in clinical unity.

) as an independent psychopathological formation seems to be an indisputable fact, but such independence is realized exclusively within the reactive (adaptive) states and dynamics of personality disorders (PD). When it comes to disorders of a more severe - affective register (recurrent, bipolar depression, dysthymia), anxiety and depression act in clinical unity.

The idea of such unity, “when difficulties arise, and sometimes the impossibility of distinguishing pure melancholy from pure anxiety at the psychopathological level” [23], is put forward by both Russian [3, 5, 16, 17, 22] and foreign [101, 140 -143, 146, 213] authors [11] . Accordingly, clinicians (Russian and foreign), recognizing the artificiality of the boundaries separating depressive and anxiety disorders into discrete categories, postulate the coexistence of two hypothymic (“cotymic” in the terminology of P. Tyrer [200]) affects - anxiety and depression within the psychopathological unity - anxious depression .

The developers of the latest version of the DSM recommended the introduction of the diagnostic rubric D05 "Mixed anxiety/depression". The presence of 3 or 4 symptoms of major depression (mandatory signs of low mood and/or anhedonia), combined with symptoms of anxiety distress, is singled out as verification criteria. The latter is defined as having two or more of the following symptoms: irrational (unmotivated) anxiety, preoccupation with painful thoughts, inability to relax, motor tension, fear or anticipation of a terrible event. The duration of symptoms is at least 2 weeks. Additional criterion: "The disorder cannot be diagnosed by the DSM as anxiety or depression, since both symptom complexes are realized simultaneously in its structure."

An attempt to revise the systematics of affective disorders with the integration of anxiety and depression within a single disorder, “panic-depressive illness” in the formulation of H. Akiskal [46], presented in the DSM-V project, is primarily based on the results of clinical studies.

Turning to the clinical characteristics of anxious depression, it should be noted a series of works performed by Australian researchers [69, 168, 169], which present the qualification of this form within the framework of non-melancholic depression. Among domestic authors V.N. Krasnov [17], based on the clinical characteristics and patterns of the course of anxiety-depressive states, argues that most of them can be attributed to non-melancholic depressions.

It should be emphasized that the publication of the article by M. Shimoda [187] laid the foundations for the activities of the Japanese National Psychiatric School [108, 189]. In the works of its representatives, a special type of anxious non-melancholic depressions is distinguished. In the description of M. Shimoda, in patients with such depressions, the mediation of depression and anxious symptoms is impaired - they, despite the appearance of neurasthenic (fatigue, insomnia) and affective disorders proper, continue to work until the depression reaches a complete psychopathological end. According to H. Hirasawa [108], along with “idle” activity, signs of somatized anxiety (a vegetative symptom complex including a feeling of lightheadedness, sleep disturbances), a feeling of self-doubt, guilt and shame towards others due to the inability to work are formed.

According to H. Hirasawa [108], along with “idle” activity, signs of somatized anxiety (a vegetative symptom complex including a feeling of lightheadedness, sleep disturbances), a feeling of self-doubt, guilt and shame towards others due to the inability to work are formed.

In German psychiatry, similar conditions were designated by K. Leonhard [144] as “self-torturing”, “hunted” depression, the clinical picture of which is dominated by phenomena of unmotivated (floating) anxiety up to agitation, obsessive fears, ideas of guilt (patients constantly condemn themselves for all kinds of misdemeanors).

As markers of non-melancholic depressions, the state corresponds to the subpsychotic register in the absence of distinct signs of vitality (loss of appetite and body weight, late insomnia, circadian rhythm), as well as anergy, unreactivity, anhedonia and psychomotor disorders. Non-melancholic depressions are associated with symptoms of reactive lability, personality disorders, and proceed with anxious anxiety (generalized/phobic anxiety, panic attacks, and other anxious disorders). Such conditions show an insufficient response to therapy and a tendency to chronicity (transformation into dysthymia).

Such conditions show an insufficient response to therapy and a tendency to chronicity (transformation into dysthymia).

As significant psychopathological features of anxiety depression occurring with panic attacks, phobias, generalized anxiety [49], the characteristics of anxiotic manifestations proper are considered. P. Kielholz [133] considered the vitalization of anxiety in the structure of anxious depression as a differentiating clinical sign that allows one to distinguish anxious disorders of an affective nature from psychogenic anxiety (associated with an object, arising as a result of real shocks and threats; existential - associated with a feeling of threat to existence due to circumstances, inability to cope with the test and - more broadly - life's problems). The author, and after him other researchers, trace the modification of anxiety in the course of the dynamics of anxious depressions, when specific fears or reactions to objective stimuli turn into “free floating” / floating anxiety, where objects are already random and multiple, and then - objectless, generalized anxiety, akin to depressive melancholy due to the vitalization of a pathologically reduced affect.

In Russian psychiatry O.P. Vertogradova et al. [2, 4], who put forward the concept of “affective pathoplasty of depressive symptoms and their correspondence to the nature of the dominant affect”, also emphasize the dynamism and tendency to vitalization of the anxious affect.

However, the data of a number of publications by domestic and foreign authors show that in the space of anxious depression, along with non-melancholic (self-torturing) anxiety-melancholic syndromes can be distinguished [12] .

It is necessary to note the historically established tradition in which such conditions are considered in the context of the nosological paradigm.

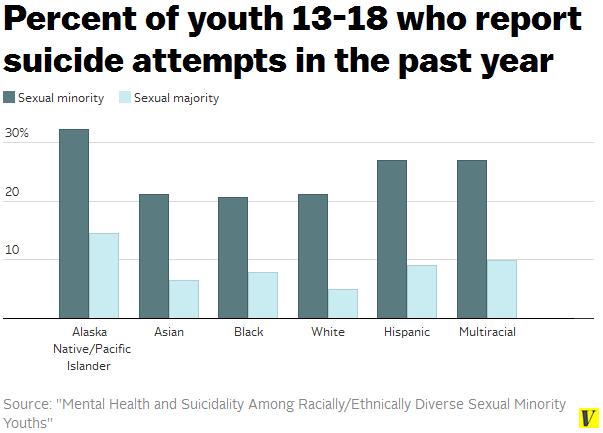

If E. Kraepelin [134], defining anxiety as “the most common form of unpleasant mental movements”, notes that this disorder is most often observed during the depressive phases of circular psychosis [13] , then E. Bleuler [64] gives a detailed description anxious depression. He singles out in the structure of depression, understood in the light of the teachings of E. Kraepelin, a distinctive phenomenon - dreary fear (schwermütig Angst), which, when anxiotic symptoms deepen to the level of agitation, can transform into delusional ideas. At the same time, E. Bleuler, referring to S. Freud, brings his term "floating anxiety" closer to his own - "free melancholy" (free-floating anxiety) - and emphasizes that depression with dreary fear is a relatively milder form of melancholia and can manifest itself not only a psychosis, but also a "neurotic anxiety neurosis." Yu.V. Cannabih [13]. At the same time, the author, and after him modern researchers [1, 8, 26, 33, 36, 41, 42, 49, 137] emphasize the connection between anxiety and suicidal risk - "the affect of fear ... often contributes to a sudden weakening and even the disappearance of lethargy, giving the patient the opportunity to implement a long-cherished thought of suicide."

Kraepelin, a distinctive phenomenon - dreary fear (schwermütig Angst), which, when anxiotic symptoms deepen to the level of agitation, can transform into delusional ideas. At the same time, E. Bleuler, referring to S. Freud, brings his term "floating anxiety" closer to his own - "free melancholy" (free-floating anxiety) - and emphasizes that depression with dreary fear is a relatively milder form of melancholia and can manifest itself not only a psychosis, but also a "neurotic anxiety neurosis." Yu.V. Cannabih [13]. At the same time, the author, and after him modern researchers [1, 8, 26, 33, 36, 41, 42, 49, 137] emphasize the connection between anxiety and suicidal risk - "the affect of fear ... often contributes to a sudden weakening and even the disappearance of lethargy, giving the patient the opportunity to implement a long-cherished thought of suicide."

An increase in anxious symptoms with a tense expectation of all sorts of misfortunes is accompanied by agitation, ideomotor agitation. Motor agitation with anxious verbigerations, aggravated by any change in the situation (symptom of adaptation disorder), may be manifested by partial phenomena of ideational retardation (wringing of fingers, restless hand movements with general immobility) - a symptom of adaptation disorder (Charpentier's phenomenon), or "anxious numbness" (" anxious retardation”, “silent anxiety” [1, 20]).

Motor agitation with anxious verbigerations, aggravated by any change in the situation (symptom of adaptation disorder), may be manifested by partial phenomena of ideational retardation (wringing of fingers, restless hand movements with general immobility) - a symptom of adaptation disorder (Charpentier's phenomenon), or "anxious numbness" (" anxious retardation”, “silent anxiety” [1, 20]).

Thus, as evidenced by the literature data and the own clinical experience of the authors of this review [31, 32, 38], there are two main types of anxiety depressions - non-melancholic/self-torturing and anxiety-melancholic.

If we try to generalize the relevant clinical descriptions, then the structure of each type of anxious depression, including pathologically altered affect, meaningful symptom complex, and comorbid anxiety-phobic formations, can be represented schematically (table) :

An analysis of the above studies allows us to conclude that there is a psychopathological (typological) heterogeneity of anxious non-melancholic depressions. These data provide a basis for raising the question of the genesis of such clinical heterogeneity. The information given in the literature allows us to suggest that the heterogeneity of the constitutional "soil" predisposing to one or another modus of affective response can be considered as a significant factor. In search of an answer to this question, let us turn to the analysis of the literature data presented in the second section of this review. At the same time, it is necessary to take into account changes in the initial theoretical positions on the basis of which the construction of diagnostic systems is carried out (at least in modern Western psychiatry) [14] .

These data provide a basis for raising the question of the genesis of such clinical heterogeneity. The information given in the literature allows us to suggest that the heterogeneity of the constitutional "soil" predisposing to one or another modus of affective response can be considered as a significant factor. In search of an answer to this question, let us turn to the analysis of the literature data presented in the second section of this review. At the same time, it is necessary to take into account changes in the initial theoretical positions on the basis of which the construction of diagnostic systems is carried out (at least in modern Western psychiatry) [14] .

Anxious depression - personality disorders (PD). Judging by the information given in the literature, the assessment of the ratio of depression, including anxiety (axis I in the DSM), with PD is carried out mainly in terms of affinity for deviations of the circle of the same name (in the DSM, along axis II, they are combined into an anxious-fearful cluster - cluster C, including anancaste / obsessive-compulsive, anxious / avoidant and dependent PD, which are assigned codes F60. 5 - F60.7 in the ICD-10, respectively).

5 - F60.7 in the ICD-10, respectively).

The existence of such an affinity is confirmed by epidemiological data, according to which, for anomalies of the anxiety-fearful cluster, the index of comorbidity with depression [15] reaches maximum values [176, 181, 186]. This conclusion follows from a comparison of the data given in other studies carried out in the late 80s of the last century. When studying samples of outpatients suffering from depressive disorders, the proportion of PD was estimated (according to DSM-III criteria) [176]. It turned out that the PD of cluster C (or traits of such a warehouse) make up a total of 67% versus 16% for cluster A (schizotypal, paranoid, schizoid) and 24% for cluster B (dissocial, borderline, narcissistic, histrionic PD). Some researchers [181, 186] cite lower, but comparable figures, according to which the RL of cluster A and B together make up 13–16%, the RL of cluster C, 32–36%, respectively.

The fact that depression predominates among persons with PD allocated within cluster C is also confirmed by the results obtained in recent years [156, 183, 192]. So, according to A. Skodol et al. [192], in a sample of 668 patients with depression, the proportion of PD ranked by categories of cluster C was 54.5% versus 15% for cluster A and 30.5% for B.

So, according to A. Skodol et al. [192], in a sample of 668 patients with depression, the proportion of PD ranked by categories of cluster C was 54.5% versus 15% for cluster A and 30.5% for B.

High personal anxiety, low self-esteem with hypersensitivity to rejection and the need for approval, conservatism, limited lifestyle and social activity - social phobia associated with evasion from potential dangers are distinguished as general diagnostic criteria for PD in this cluster.

Most of the works (they are more often made in the psychodynamic tradition using psychometric techniques) provide descriptions that, according to P. Chodoff [74], outline the features of the obsessive, anxious and dependent features of an abnormal personality predisposing to depression. The complex of these properties is distinguished by similarity with the common for all PD cluster C prototype - "obsessional neurotics" [44] [16] . This commonality is reflected by the following properties: meticulousness, adherence to routine, combined with caution, tension, and also "neurasthenicity". Similar features in the psychological concept of P. Janet [112] are interpreted as the result of a decrease in the intention (tension) of mental activity with a feeling of incompleteness, incompleteness of most thought processes. According to A.B. Smulevich [30, 31], the consciousness of such a flaw that gives rise to doubts is compensated by excessive conscientiousness with the desire to flawlessly perform any business, scrupulousness, exactingness. P. Matussek et al. [154] add to these characteristics the desire to avoid open conflicts, as well as emotional narrowness. M. Metcalfe [159] indicates a combination of such contrasting features as anxiety and tension, on the one hand, and rigidity, lack of imagination, sense of humor, adherence to habits, patterns [17] , on the other.

Similar features in the psychological concept of P. Janet [112] are interpreted as the result of a decrease in the intention (tension) of mental activity with a feeling of incompleteness, incompleteness of most thought processes. According to A.B. Smulevich [30, 31], the consciousness of such a flaw that gives rise to doubts is compensated by excessive conscientiousness with the desire to flawlessly perform any business, scrupulousness, exactingness. P. Matussek et al. [154] add to these characteristics the desire to avoid open conflicts, as well as emotional narrowness. M. Metcalfe [159] indicates a combination of such contrasting features as anxiety and tension, on the one hand, and rigidity, lack of imagination, sense of humor, adherence to habits, patterns [17] , on the other.

It should be emphasized that although a number of studies [92, 93, 203] have shown that anankastic (anxiety) depression occurring with obsessive-phobic disorders is preferably formed “on the basis of a compulsive temperament” (terminology of H. Akiskal et al. [ 45]), the ratio of anxiety depression - constitutional warehouse is considered outside the typological differentiation presented above (in the first section of this review). Accordingly, the clinical argumentation of the position according to which the PD of cluster C is assessed as a predictor of anxiety-related depression that will form in the future, and a depressive episode as a direct continuation of the abnormal premorbid warehouse, is based on the general characteristics of all personality anomalies attributed to the anxious-fearful cluster. However, from our point of view, this approach does not provide the possibility of a comprehensive analysis of the relationship under discussion, since it does not take into account the dichotomous subdivision of anxious depressions into anxiety-melancholic and self-torturing types.

Akiskal et al. [ 45]), the ratio of anxiety depression - constitutional warehouse is considered outside the typological differentiation presented above (in the first section of this review). Accordingly, the clinical argumentation of the position according to which the PD of cluster C is assessed as a predictor of anxiety-related depression that will form in the future, and a depressive episode as a direct continuation of the abnormal premorbid warehouse, is based on the general characteristics of all personality anomalies attributed to the anxious-fearful cluster. However, from our point of view, this approach does not provide the possibility of a comprehensive analysis of the relationship under discussion, since it does not take into account the dichotomous subdivision of anxious depressions into anxiety-melancholic and self-torturing types.

If we proceed from the opposite position, then, in accordance with the typology of anxious depressions, it is possible to single out two corresponding variants of the constitutional predisposition to the development of each of them.

The first of these types corresponds to P. Janet [111, 112] variant of psychasthenia traditionally identified in Russian psychiatry [9, 10, 28, 39, 43] as polar to psychasthenics (anancasts) - an anxious and suspicious character, first presented in the classic description of S.A. Sukhanov [35].

Evaluating the selected type of PD as one of the variants of psychasthenia (ie, a separate disease not associated with cyclothymia - psychoneurosis), the author at the same time considers the possibility of forming cyclothymic - mainly melancholic - phases on this "soil". Moreover, S.A. Sukhanov, as Yu.V. Kannabih [13], emphasizes the affinity of an anxious and suspicious nature with affective spectrum disorders. Interpreting the fact of exacerbation during the period of cyclothymic/melancholic depression of the main features of the psychasthenic mental state, the author points to "the homogeneity of the emotional tone of psychasthenia with the main emotional tone characteristic of cyclothymic depression" [13].

According to a number of characteristics, this variant overlaps with other cluster C anomalies and is combined with anxious/avoidant RL in modern taxonomy.

However, such a combination, as evidenced by our own clinical experience [32], results in the leveling of the anxious and suspicious warehouse as a special variant of avoiding PD, predisposing to the manifestation of depression, comparable to the picture of circular melancholia.

Observations by V.V. Chitlova [38], which made it possible to confirm the working hypothesis, according to which the contribution of PD of a non-affective circle (and, in particular, of an anxious and suspicious nature) to susceptibility to depression is not limited to the formation of vulnerability to certain pathogenic factors triggering an affective disorder (endogenous, psychogenic, somatogenic) or pathoplastic influences, as the concepts of the same name postulate (spectrum [48, 51, 135, 138, 171, 210], vulnerability [60, 63, 90, 104, 116, 166]). Being a heterogeneous affective RL anomaly, this warehouse includes (like affective RL), albeit in an unexpanded form, dimensions - harbingers of a future depression. Accordingly, with an anxious and suspicious character, there is a hidden / latent stigmatization, reflecting the affinity of this constitutional warehouse with the RL of the affective cluster [18] .

Being a heterogeneous affective RL anomaly, this warehouse includes (like affective RL), albeit in an unexpanded form, dimensions - harbingers of a future depression. Accordingly, with an anxious and suspicious character, there is a hidden / latent stigmatization, reflecting the affinity of this constitutional warehouse with the RL of the affective cluster [18] .

The stigmatization of the affective type appears most clearly in the analysis of the trajectory of psychasthenic pathocharacterological properties.

In this regard, it is necessary to emphasize such features of the dynamics of the discussed variant of RL as reactive lability, associated with the instability of the affective and vegetative background and, according to P.B. Gannushkin [10], one of the important components of vulnerability to depression. Already from childhood or adolescence, there is a tendency to develop blurred hypothymic episodes occurring at the subclinical level (subthreshold affective disorders H. Helmchen and M. Linden [103]). The latter are considered as "nuclear" manifestations of affective (cyclothymic) diathesis [47, 172]. At the same time, like “affective” PD, in which E. Kretschmer [138] singles out the hypothymic radical as a “characterological link between the hyperthymic and melancholic halves of the cycloid warehouse”, this affective deposit also appears in the considered variant. The latter in the structure of an anxious and suspicious character is manifested (albeit in the form of latent, optional features) by responsiveness to someone else's grief, the ability to take everything “close to heart”, and easily respond to sad events.

Helmchen and M. Linden [103]). The latter are considered as "nuclear" manifestations of affective (cyclothymic) diathesis [47, 172]. At the same time, like “affective” PD, in which E. Kretschmer [138] singles out the hypothymic radical as a “characterological link between the hyperthymic and melancholic halves of the cycloid warehouse”, this affective deposit also appears in the considered variant. The latter in the structure of an anxious and suspicious character is manifested (albeit in the form of latent, optional features) by responsiveness to someone else's grief, the ability to take everything “close to heart”, and easily respond to sad events.

This constitutional deposit is realized during periods of exacerbation of pathocharacterological symptom complexes, inseparable from the tendency of "anxious-suspicious" personalities to dramatize key experiences. In critical situations (examinations, preparation for the wedding, "work rush" at work) there is a sharpening of their inherent anxiety properties (self-doubt, tendency to doubt, timidity) [19] , reaching the level of clinically outlined anxiety symptom complexes - panic attacks and /or vital (generalized) anxiety that determines the picture of the reaction. Accordingly, the clinical space of affective disorders, the main manifestations of which are combined with the anxious component, is narrowing. Hypothymia loses its vitality and acts at the level of optional elements of the syndrome. However, in this "narrowed" space, even before the formation of a manifest depressive episode, a constitutional affective radical is realized. Manifestations of such hypothymia masked by anxious phenomena (somatic anxiety, psychovegetative, organoneurotic symptoms) [148] include signs-predictors (outpost-symptoms) of future melancholic depression [20] . Among them, the most informative are erased anhedonia (“insipid life with sadness” in the self-description of patients), anticipating the formation of melancholy, a pessimistic attitude with a decrease in self-esteem - a harbinger of ideas of insolvency, weight loss / insomnia - a “lightning bolt” of somatic depression syndrome.

Accordingly, the clinical space of affective disorders, the main manifestations of which are combined with the anxious component, is narrowing. Hypothymia loses its vitality and acts at the level of optional elements of the syndrome. However, in this "narrowed" space, even before the formation of a manifest depressive episode, a constitutional affective radical is realized. Manifestations of such hypothymia masked by anxious phenomena (somatic anxiety, psychovegetative, organoneurotic symptoms) [148] include signs-predictors (outpost-symptoms) of future melancholic depression [20] . Among them, the most informative are erased anhedonia (“insipid life with sadness” in the self-description of patients), anticipating the formation of melancholy, a pessimistic attitude with a decrease in self-esteem - a harbinger of ideas of insolvency, weight loss / insomnia - a “lightning bolt” of somatic depression syndrome.

Even more obvious is the affective stigmatization of the anxious and suspicious warehouse in the formation of disorders of the hyperthymic circle. Hyperthymia in these observations takes on more distinct clinical forms and develops (compared to hypothymia) according to other clinical mechanisms. If the manifestation and reverse development of depressive disorders are closely related to exacerbation and the subsequent dynamics of anxiety-phobic symptom complexes, which are pushed to the level of facultative symptom complexes, then the manifestations of hyperthymia, previously latent, during periods of compensation inherent in the anxious-suspectoral nature of pathocharacterological manifestations, are accentuated to the level of obligate personality dimensions. The latter are correlated with the characteristics of “balanced” [184], “passive” [173] hyperthymics, which are characterized by a “flat line” of increased affect [85]. Being energetic, productive enough, patients do not commit reckless acts. Their restless activity (in a self-description - the ability to "turn like a top") is predictable and is realized within a narrow circle of official duties and everyday concerns.

Hyperthymia in these observations takes on more distinct clinical forms and develops (compared to hypothymia) according to other clinical mechanisms. If the manifestation and reverse development of depressive disorders are closely related to exacerbation and the subsequent dynamics of anxiety-phobic symptom complexes, which are pushed to the level of facultative symptom complexes, then the manifestations of hyperthymia, previously latent, during periods of compensation inherent in the anxious-suspectoral nature of pathocharacterological manifestations, are accentuated to the level of obligate personality dimensions. The latter are correlated with the characteristics of “balanced” [184], “passive” [173] hyperthymics, which are characterized by a “flat line” of increased affect [85]. Being energetic, productive enough, patients do not commit reckless acts. Their restless activity (in a self-description - the ability to "turn like a top") is predictable and is realized within a narrow circle of official duties and everyday concerns. Accordingly, we are talking about erased, masked hypomanias [65], in some cases situationally provoked (happy romance, childbirth, promotion).

Accordingly, we are talking about erased, masked hypomanias [65], in some cases situationally provoked (happy romance, childbirth, promotion).

As shown by our own clinical observations [38], the compensation of anxious and suspicious PD is accompanied by a transposition (re-accentuation) of pathocharacterological properties - psychasthenic features, although they persist, but constitutional characteristics related to the RL spectrum of the affective (hyperthymic) circle come to the fore. During this period, patients act in a different "hypostasis" - the opposite of hypothymia - as active, cheerful people who love pleasure, who do not shy away from parties, feasts, and cheerful companies.

Thus, an anxious and suspicious character, in the structure of which affective stigmatization was revealed, can be combined with affective PD on the basis of a single complex of abnormal personality traits that determines the predisposition to the manifestation of melancholic depression and be considered as a factor of comorbidity with affective spectrum disorders.

A similar approach to combining personality characteristics detected in PD of various clusters, in terms of connection with affective pathology, can also be traced in studies performed in accordance with the concept of cyclothymic diathesis [47, 115, 172].

Another variant of the constitutional make-up (according to the data obtained by the authors of this review [32, 38] and the information given in the literature [69, 169]) determines the predisposition to non-melancholic - self-torturing depression. We are talking about a clinical community (perfectionism, workaholism, narcissism), which distinguishes a special abnormal warehouse - statothymia/immodhymia [188, 189] or typus melancholicus [198]. The structure of this constitutional warehouse is designated by Japanese authors as "statothymia" ( Greek - statikos - motionless; thymo's -nast

Depersonalization: a syndrome that interferes with feeling - BBC News Context”: it will help you to understand the events.

Image caption,

Image caption, Sarah says that because of her illness, familiar places seem like scenery

People with depersonalization syndrome see the world as unreal, two-dimensional, as if in a fog. Every hundredth suffers from this disorder, but despite this, British doctors are not taught to work with such patients, experts say.

"The connections that you consider valuable lose their original meaning. You know that you love your family. But the fact is that you are more aware of it with your mind than you feel," Sarah says on the Victoria Derbyshire program on B -bc.

Sarah is an actress, she constantly tries on different images and reproduces other people's emotions. But in reality, for most of her conscious life, she is emotionally paralyzed and unable to experience any feelings.

The reason for this is a little-studied mental disorder called depersonalization.

Sarah had the syndrome three times. The first time it happened was when she was preparing for her final exams.

The first time it happened was when she was preparing for her final exams.

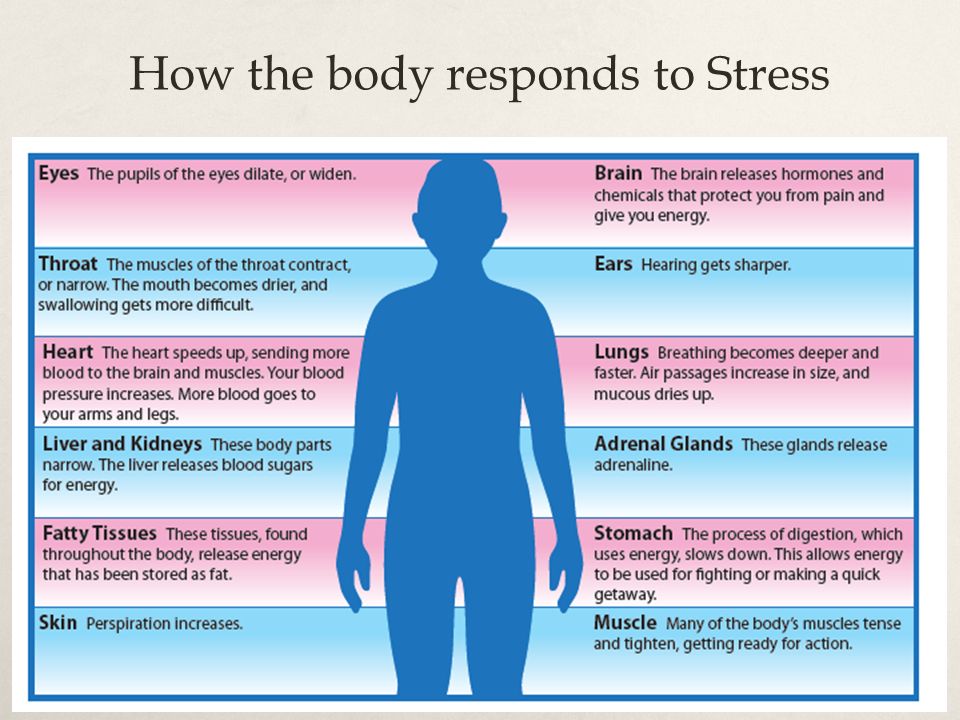

The main sign of depersonalization is the feeling that a person is losing physical connection with the world around him and his own body.

It is believed that this is how a defense mechanism manifests when, during stress or a serious shock, consciousness is disconnected from reality. Some drugs, such as marijuana, can cause the same effect.

- Depression: a breakthrough in understanding the nature of the disease and its

- What your selfies say about you

- Google helps users recognize depression

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

End of Story Podcast

For people with depersonalization syndrome, the world can change in a second.

"It was an unexpected switch. Everything around seemed alien and even intimidating. Suddenly, the apartment and other places where you used to be become a film set for you, and all your things become scenery," says Sarah.

Other patients report feeling that they are outside their body, that it does not belong to them, and that the world around them seems two-dimensional and flat.

This happened to Sarah during the second episode.

"I was reading, I had a book in my hands. And suddenly my hands began to look like a picture on which two hands were drawn. There was a feeling that the real world and my perception of it did not coincide."

Sarah's disorder is not uncommon. Three independent studies have proven that it occurs in one person out of a hundred.

Experts say the disorder has long been recognized as a medical condition. It is as common as obsessive-compulsive disorder or schizophrenia.

Some untreated patients may suffer lifelong depersonalization symptoms. And yet, not all doctors know what it is.

A doctor who recently graduated and suffers from this disorder himself stated that depersonalization was not taught in medical school or in continuing education courses for therapists.

He admitted that he had misdiagnosed his patients at least twice. According to him, he will be very surprised if it turns out that at least one of his colleagues has heard about this syndrome.

Sarah says that in her life she encountered at least 20 professionals who had no idea what she was talking about. Among them are consultants, therapists, district psychiatrists and doctors.

The Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) in London said that mental health was a key element of an expanded curriculum for physicians.

The institute added that the study of more complex psychological problems is still in development.

The Royal College of Psychiatry stressed the need to ensure that these disorders are properly understood.

Image caption,Dr Elaine Hunter runs the only referral center in the UK that treats patients with depersonalization

Poor diagnosis is only part of the problem, access to treatment is another complication.

There is only one specialized clinic in the UK. Its resources are limited, it can only accept 80 patients a year. Despite the fact that 650 thousand people can potentially suffer from this disease.

To access this health center free of charge, a referral from a local doctor is required. And even if the patient is diagnosed with depersonalization, treatment will have to wait several months or longer.

After a year of waiting in line, Sarah decided that the only way out was to pay for the treatment herself.

"I used to have panic attacks all the time. It's really scary. I knew it was a crisis," she says.

A specialist center for patients with depersonalization syndrome operates at the Maudsley Hospital in south London. However, there are restrictions for patients under 18 years of age; the center only treats adults.

Often the disease occurs in adolescence. Dr. Elaine Hunter, who heads the center, is concerned that she has to withhold care for children and adolescents.

"Sometimes 15-year-old patients come to us deeply depressed and frightened, but we have nothing to offer them," she says.

One of the adult patients of the center developed the syndrome at the age of 13. For two years she could not leave the house, she experienced ten panic attacks a day caused by the disorder.

At the beginning of the treatment, she did not even recognize her own parents.

Dr. Hunter hopes that over time, the right treatment will be available to underage patients.

She believes that treatment should be organized in every district. Physicians in local centers for psychological assistance should undergo special training, then disseminate information among other specialists.

Image caption,Sarah Ashley couldn't eat or sleep until she was treated by Dr. Hunter

Hunter developed Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) specifically for patients with depersonalization. She believes that she will be easily mastered by doctors who already have experience in talking therapy.

Sarah Ashley, a patient of Dr. Hunter, says she was initially skeptical about the technique, but after a while she felt a huge difference.

"[Before CBT] I looked at my own hands or other body parts and felt like they weren't mine. I looked at myself in the mirror and didn't realize it was me," explains Sarah.

"I couldn't eat or sleep, and due to stress I lost 42 kg. I still have some symptoms now, but I can get over them quickly," she continues.