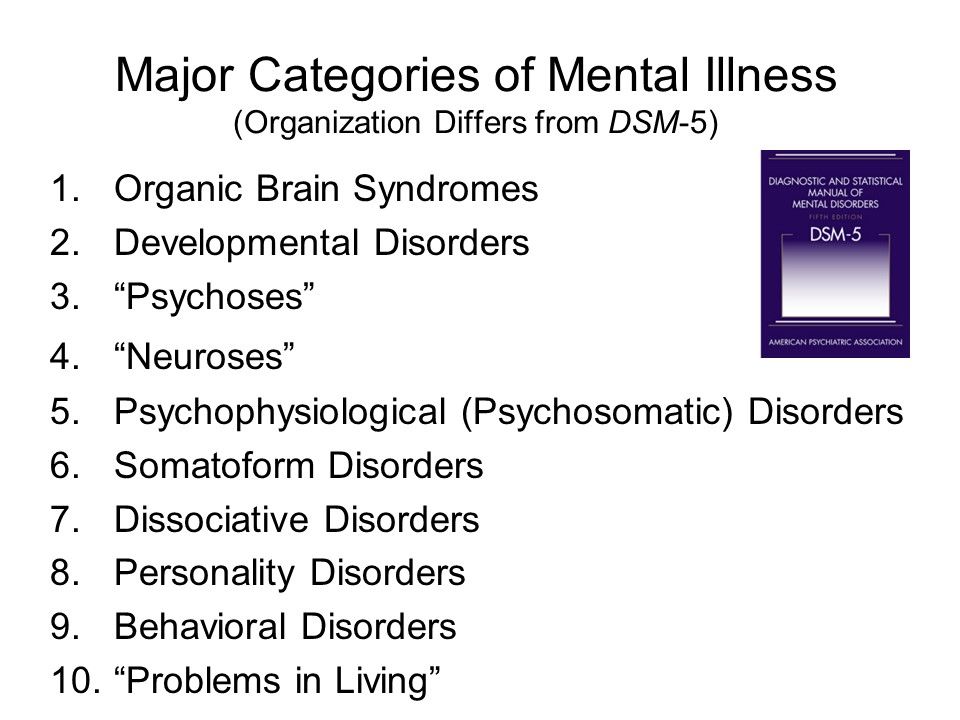

Manual for mental disorders

What is the DSM?

The DSM is a reference handbook that most U.S. mental health professionals use to reach an accurate diagnosis. The latest version of the manual is the DSM-5-TR.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) was released on March 18, 2022 by the American Psychiatric Association (APA).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a formal classification of mental health disorders, featuring symptoms, diagnostic criteria, culture and gender-related features, and other important diagnostic information. The DSM does not include treatment guidelines.

In other words, the DSM is a tool and reference guide for mental health clinicians to diagnose, classify, and identify mental health conditions.

The DSM also includes “specifiers.” These are extensions to the formal diagnoses that specify one or more particular features, like onset or severity. A diagnosis can have one or more specifiers to make it more precise.

In other words, because a mental health condition doesn’t always present itself in the same way, a DSM specifier can better describe particular scenarios.

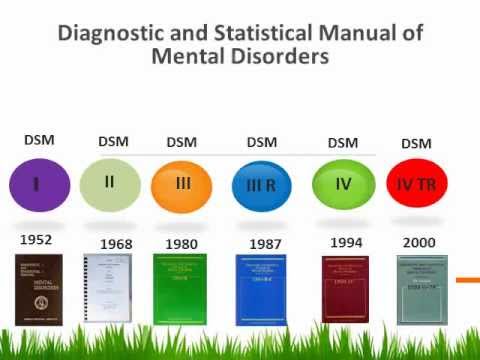

The DSM has had many revisions, to clarify, add, or remove mental health diagnoses according to the latest research and clinical consensus.

It took more than 13 years to update and finalize the book’s fifth edition and about 10 years to release the current text revision.

The DSM-5 was released in 2013 and the current version released in 2022 is the DSM-5-TR.

The difference between a new edition and a text revision is that the first one is released when new research supports the need to create, remove, or significantly revise key aspects of existing diagnoses.

A text revision, on the other hand, refers to editing the existing text to clarify some concepts, introduce inclusive language, or update statistics and references. Sometimes, like it’s the case with the DSM-5-TR, a new diagnosis might be introduced.

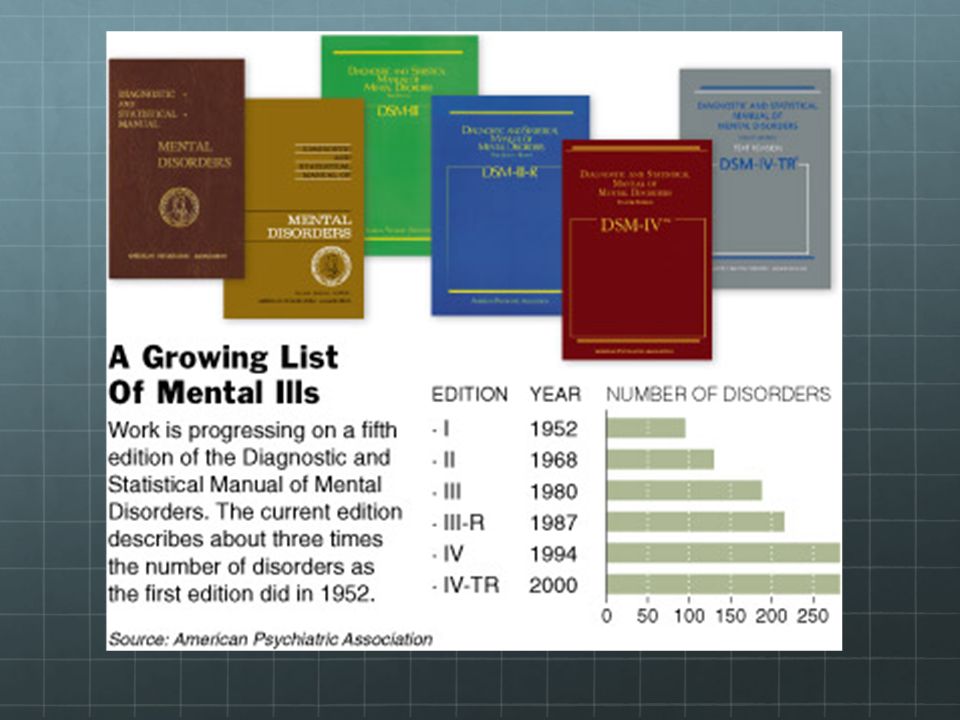

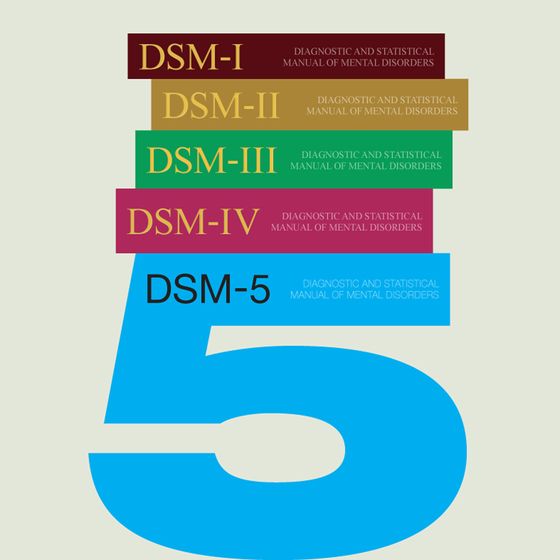

The first edition of the DSM was published in 1952 following an increased need to classify and define mental conditions, especially in veterans returning home after World War II.

The DSM was created to catalog mental health conditions similar to its counterpart, the International Classification of Disease (ICD).

The ICD is published by the World Health Organization (WHO) and catalogs both physical and mental conditions.

The DSM-II was released in 1968 and focused on broadening terms and definitions from the original DSM to diagnose mental health conditions better.

The biggest shift in the history of the DSM came as a result of the DSM-III, published in 1980.

This edition listed 265 categories — a big increase from 182 in the previous edition. This jump was due to an expansion of disorder subtypes, which allowed for more accurate classifications and options for a diagnosis.

The DSM-III also saw the removal of “homosexuality” as a mental condition category.

The DSM-III would later receive an update and be revised and renamed in 1987 as the DSM-III-R.

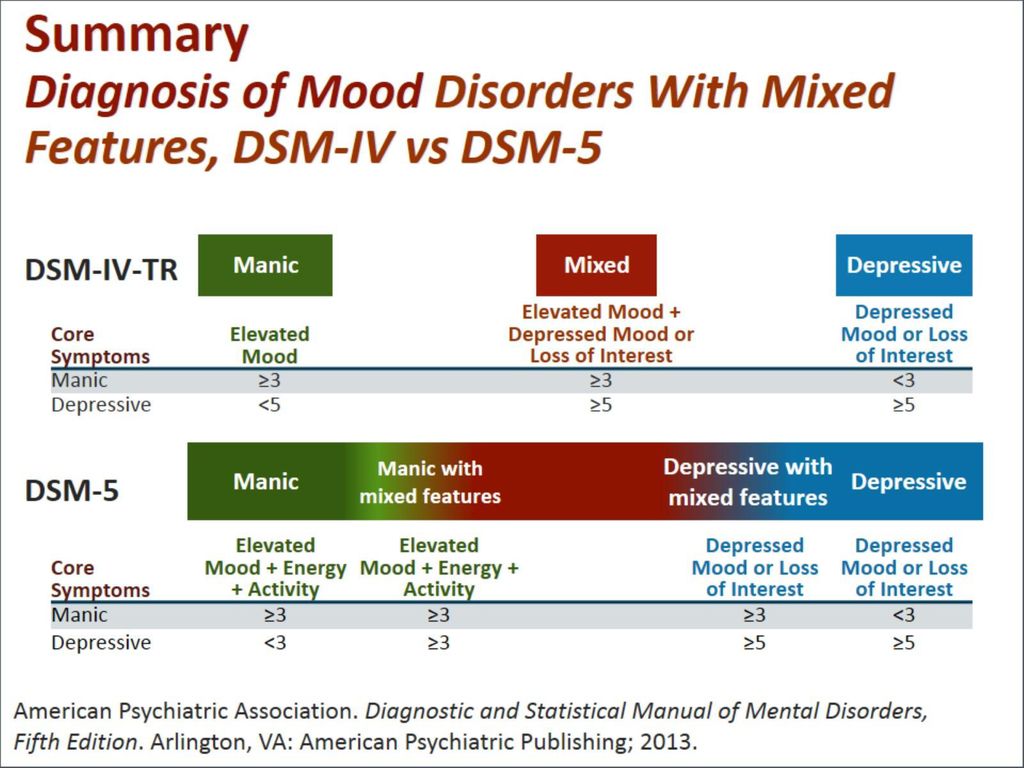

The next edition, the DSM-IV, was published in 1994 and was created alongside the WHO’s International Classification of Disease, 10th edition. This aimed to decrease inconsistencies in terminology between the two manuals.

The DSM-IV would see one final revision in 2000, named the DSM-IV-TR before the DSM-5 was released in 2013.

The latest text revision of the DSM-5 was released in 2022.

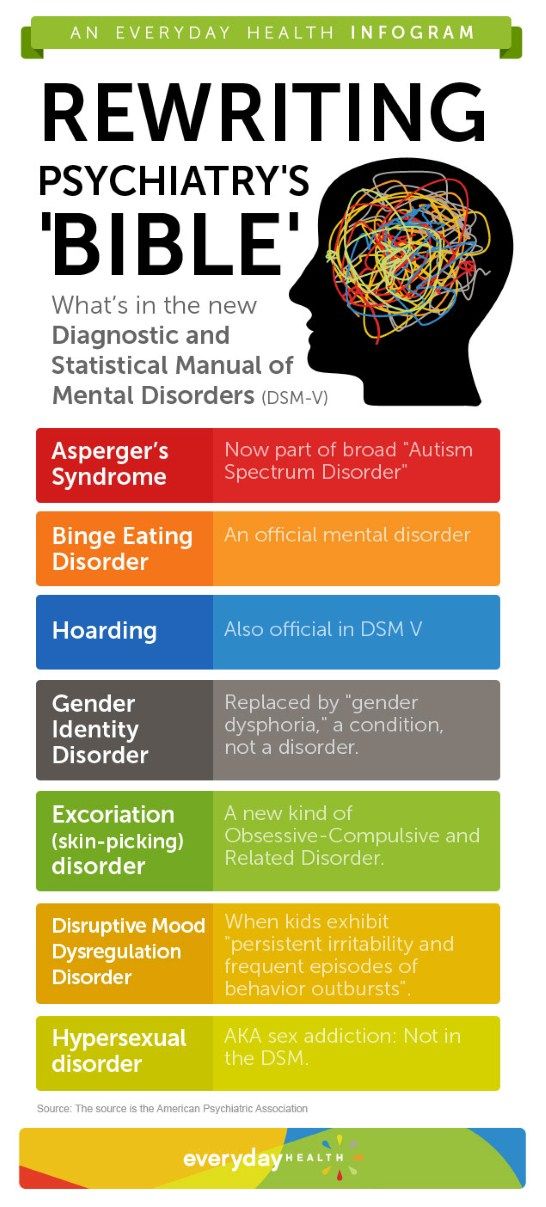

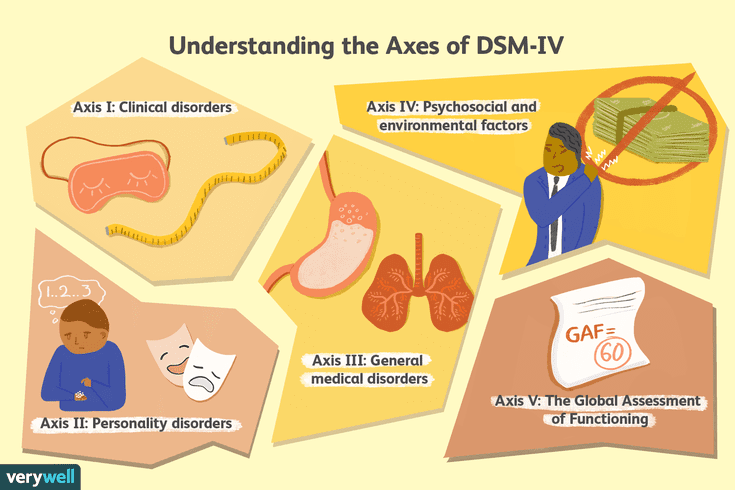

One of the biggest changes in the DSM-5 is the removal of the multiaxial assessment system to categorize diagnoses.

This evaluation method was based on multiple factors, specifically five “axes”:

- clinical disorders

- personality disorders

- general medical disorders

- psychosocial and environmental factors

- global assessment of functioning

The system was removed and replaced with a streamlined diagnostic method that combines axes I, II, and III into 1.

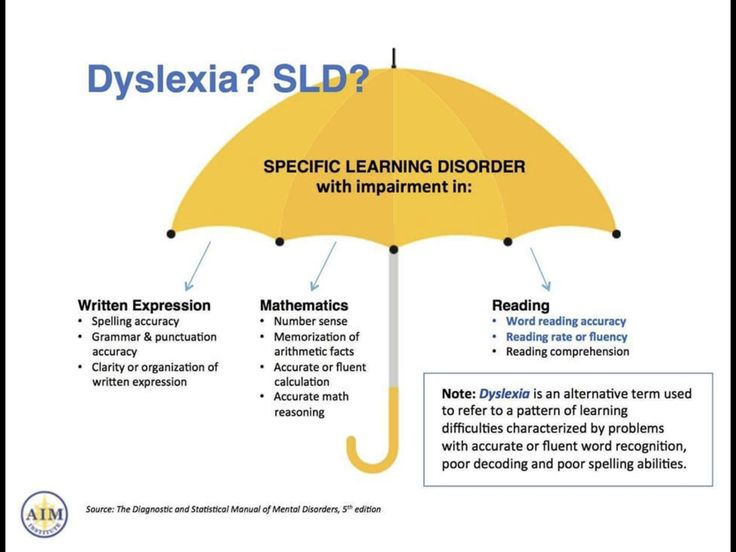

Additional changes in the DSM-5 include broadening the definitions to clarify certain conditions.

For example, the diagnostic label autism spectrum disorder now comprises four previously separate conditions:

- autistic disorder

- Asperger’s disorder

- childhood disintegrative disorder

- pervasive developmental disorder

The DSM-5 is organized into three sections and an appendix.

Section II of the DSM-5 is the lengthiest because it lists all of the mental health disorders.

Here are the DSM sections:

Section I: DSM-5 Basics

This section includes an “Introduction” and “Use of the Manual” chapters, as well as a “Cautionary Statement for Forensic Use of DSM-5” chapter.

Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes

This section includes classifications and definitions of mental health disorders.

These conditions are organized alphabetically and developmentally, with all childhood conditions listed before adult on-set conditions.

Section III: Emerging Measures and Models

This section comprises chapters that discuss applying the newest mental health information — for example, assessment measures and how to account for cultural influences.

It also includes newer conditions that require further study before entering the general diagnostic classification — for example, caffeine use disorder and internet gaming disorder.

Appendix

The final section contains supplemental information such as a list of changes from the DSM-4 to the DSM-5, a glossary of technical terms, and a list of DSM-5 advisors.

Major changes in the DSM-5 from the DSM-IV

Below are links to explore additional updates and changes to the DSM-5:

- DSM-5 Released: The Big Changes

- DSM-5 Changes: Depression & Depressive Disorders

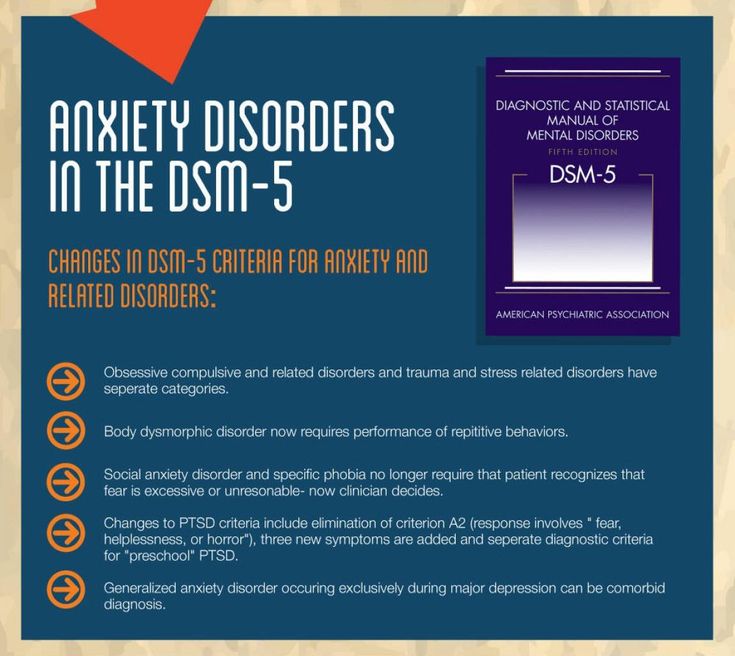

- DSM-5 Changes: Anxiety Disorders & Phobias

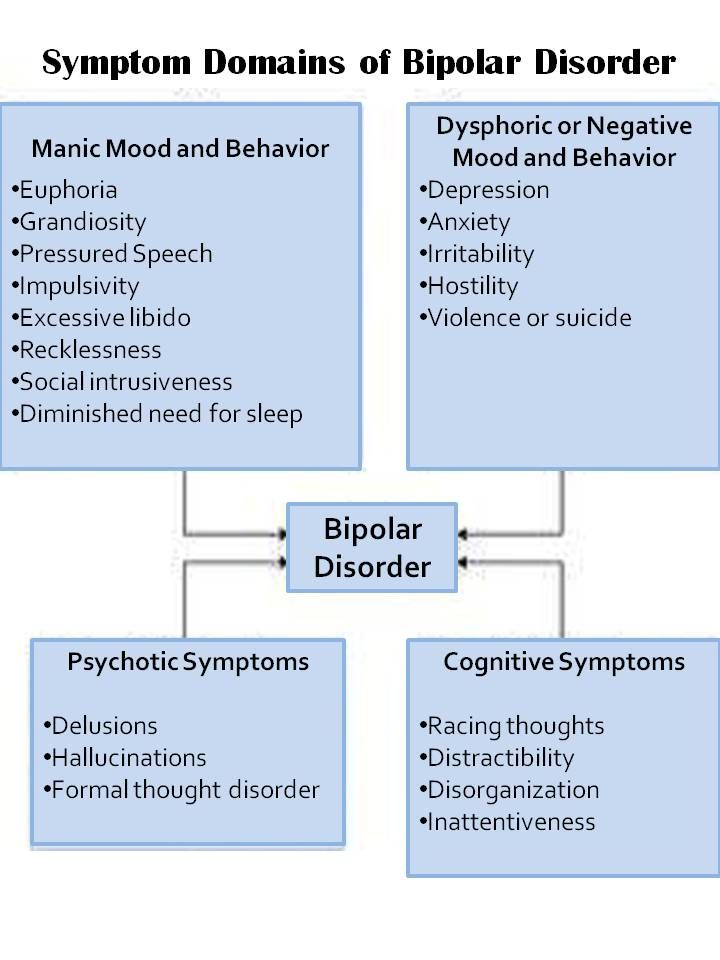

- DSM-5 Changes: Bipolar & Related Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Schizophrenia & Psychotic Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- DSM-5 Changes: Addiction, Substance-Related Disorders & Alcoholism

- DSM-5 Changes: PTSD, Trauma & Stress-Related Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Feeding & Eating Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Dissociative Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Personality Disorders (Axis II)

- DSM-5 Changes: Sleep-Wake Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Neurocognitive Disorders

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) is an edit of the DSM-5 that includes:

- a revision of the original descriptive text in the DSM-5, specifically under these headings:

- recording procedures

- specifiers

- diagnostic features

- associated features

- prevalence

- development and course

- risk and prognostic factors

- culture-related diagnostic issues

- sex and gender-related diagnostic issues

- association with suicidal thoughts or behavior

- functional consequences

- differential diagnosis

- comorbidity

- new and updated references to include more recent literature

- new text regarding the impact of discrimination and racism on mental health diagnoses

- a list of updated diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, clinical modification (ICD-10-CM), including codes related to suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-harm

- one new diagnosis (prolonged grief disorder) in section II, under trauma- and stressor-related disorders

- changes in language in the gender dysphoria chapter, going from “desired gender” to “experienced gender”

- changes in language to refer to gender-related procedures, going from “cross-sex medical procedure” to “gender-affirming medical procedure”

- changes in language in sex-related assignments, going from “natal male” or “natal female” to “individual assigned male at birth” and “individual assigned female at birth”

This is how the DSM-5-TR is indexed:

- DSM-5-TR Classification

- Preface

- Section I: DSM-5-TR Basics

- Introduction

- Use of the Manual

- Cautionary Statement for Forensic Use of DSM-5-TR

- Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes

- Neurodevelopmental Disorders

- Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

- Bipolar and Related Disorders

- Depressive Disorders

- Anxiety Disorders

- Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

- Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

- Dissociative Disorders

- Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders

- Feeding and Eating Disorders

- Elimination Disorders

- Sleep-Wake Disorders

- Sexual Dysfunctions

- Gender Dysphoria

- Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Neurocognitive Disorders

- Personality Disorders

- Paraphilic Disorders

- Other Mental Disorders and Additional Codes

- Medication-Induced Movement Disorders and Other Adverse Effects of Medication

- Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention

- Section III: Emerging Measures and Models

- Assessment Measures

- Culture and Psychiatric Diagnoses

- Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personality Disorders

- Conditions for Further Study

- Appendix

- Alphabetical Listing of DSM-5-TR Diagnoses and Codes (ICD-10-CM)

- Numerical Listing of DSM-5-TR Diagnoses and Codes (ICD-10-CM)

- DSM-5 Advisors and Other Contributors

- Index

More than 200 mental health experts contributed to the DSM-5-TR.

The DSM-5 offers an extensive list of conditions and symptoms that can aid mental health professionals in reaching accurate diagnoses. The latest version is the DSM-5-TR.

The manual has come a long way since its first edition and now provides diagnostic criteria for 193 mental health conditions.

The DSM is a living document that continues to change over time as we learn more about human cognition and behavior.

DSM | Psychology Today

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a guidebook widely used by mental health professionals—especially those in the United States—in the diagnosis of many mental health conditions. The DSM is published by the American Psychiatric Association and has been revised multiple times since it was first introduced in 1952. The most recent edition is the fifth, or the DSM-5. It was published in 2013.

The most recent edition is the fifth, or the DSM-5. It was published in 2013.

The DSM coexists with various alternative diagnostic tools, although these other guides are generally less commonly used in the U.S. The most widely consulted counterpart of the DSM, the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD), covers mental health disorders along with a vast number of other health conditions. The ICD is the primary diagnostic tool for mental health professionals outside the U.S.

Contents

- How the DSM Is Used

- How the DSM Has Changed Over Time

How the DSM Is Used

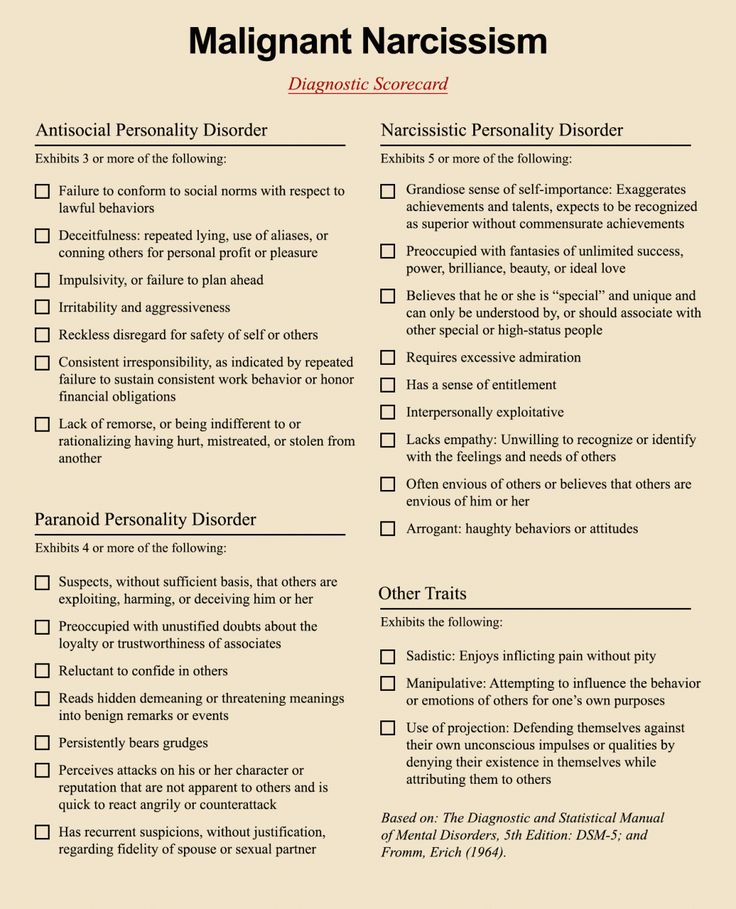

The DSM features descriptions of mental health conditions ranging from anxiety and mood disorders to substance-related and personality disorders, dividing them into categories such as major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and narcissistic personality disorder. These disorders are grouped into chapters based on shared features, e.g., Feeding and Eating Disorders; Depressive Disorders; Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders.

These disorders are grouped into chapters based on shared features, e.g., Feeding and Eating Disorders; Depressive Disorders; Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders.

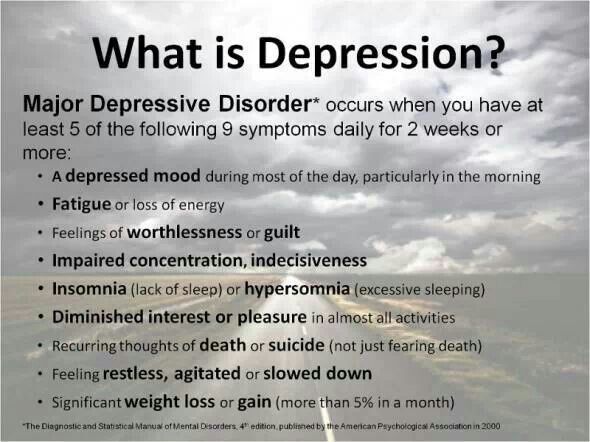

For each disorder category, the manual includes a set of diagnostic criteria—lists of symptoms and guidelines that psychiatrists, psychotherapists, and other health professionals use to determine whether a patient or client meets the criteria for one or more diagnostic categories. For diagnosis of major depressive disorder, for example, the current DSM states that a person shows at least five of a list of nine symptoms (including depressed mood, diminished pleasure, and others) within the same two-week period. It also requires that the symptoms cause “clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning,” along with other stipulations.

Updates to these diagnostic categories and criteria are made through a years-long research and revision process that involves groups of experts focusing on distinct areas of the manual.

What are the benefits of DSM?

The DSM is important for several reasons. First, it creates a common language to describe mental disorders; developing consistency is key because diagnoses are primarily based on symptoms and family history rather than more objective measures like blood tests or brain scans.

Second, diagnosis makes it possible to study treatments for mental illnesses. When people present to mental health services, professionals need to have some guide as to which treatments will best address particular collections of symptoms. Third, diagnosis facilitates research into the causes of mental disorders. If research in Peru links depression with poverty, a common concept of depression is necessary to investigate similar links in Canada.

Is the DSM helpful for clinicians?

Diagnostic criteria help students and early-career professionals build templates of mental disorders that go beyond a layperson’s impressions—for instance that bipolar disorder describes abnormal moods sustained over weeks or months, not moods that shift over an hour or a day. The DSM establishes a common language for professional communication and research, not to mention insurance codes.

The DSM establishes a common language for professional communication and research, not to mention insurance codes.

However, there are also ways in which mental health professionals don’t view the DSM as clinically useful. After seeing many patients, clinicians gradually form their own mental models of common diagnoses that might differ from the DSM, for example that the published criteria for a particular diagnosis is a little too wide or too narrow. In the end, clinicians may privilege the nosology of their own experience over the official manual that approximates it.

Is the DSM helpful for researchers?

The criterion-based diagnoses listed in the DSM have improved consistency and reliability in classifying mental health conditions over time; clinicians around the world can now largely agree whether a particular patient “meets DSM criteria.” This shift in the DSM has been useful for research, in which the homogeneity of study groups is crucial.

What are some criticisms of the DSM?

Some believe that the failure to develop effective treatments for mental health disorders can in part be traced to a failure of classification, embodied by the long-standing reliance on the DSM. The DSM labels clusters of co-occurring symptoms and sorts them into disorder categories, but there is little evidence that these categories correspond to distinct biological realities. DSM categories may thereby hamper rather than facilitate psychology’s understanding of mental disorders.

How the DSM Has Changed Over Time

The DSM has always been a lightning rod for debate about psychiatric diagnosis and classification. Since the 1950s, various categories of disorders have been added to the manual, altered, or removed altogether based on evolving clinical expertise and research and changes in the field of psychiatry, including a pivot away from psychoanalysis.

As the DSM is the dominant text for making mental health diagnoses in America, many of these changes are considered historically significant, such as when the DSM ceased to classify homosexuality as a form of mental illness in 1973. Other shifts have been controversial, including the omission of Asperger’s disorder from the DSM-5 in favor of a broader autism spectrum disorder category.

What are the current disorder categories in the DSM-5?

The DSM-5 organizes mental disorders into the following chapters: Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders, Bipolar and Related Disorders, Depressive Disorders, Anxiety Disorders, Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders, Dissociative Disorders, Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders, Feeding and Eating Disorders, Elimination Disorders, Sleep-Wake Disorders, Sexual Dysfunctions, Gender Dysphoria, Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders, Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders, Neurocognitive Disorders, Personality Disorders, Paraphilic Disorders, Other Mental Disorders, Medication-Induced Movement Disorders and Other Adverse Effects of Medication, and Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention.

What changes were incorporated into the DSM-5?

The DSM-5 departed from the previous version in several ways. A few of the key changes include:

• Eliminating the multi-axial diagnostic system that required clinicians to rate each client according to criteria other than their main psychological disorder.

• Replacing the diagnoses “Autistic Disorder” and “Asperger’s Disorder” with the overarching label “Autism Spectrum Disorder.”

• Establishing “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders” as its own group of disorders rather than an anxiety disorder.

• Establishing PTSD as a “Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorder” rather than an anxiety disorder.

• Replacing the diagnoses "Alcohol Abuse" and "Alcohol Dependence" with the overarching label "Alcohol Use Disorder," characterized as mild, moderate, or severe based on the number of symptoms present. The same goes for other diagnoses related to addiction.

• Changing diagnoses with stigmatizing terminology, such as replacing the diagnosis “Mental Retardation” with “Intellectual Disability. ”

”

• Removing the exception of bereavement for the diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder.

• Adding the diagnosis “Mild Neurocognitive Impairment” to categorize cognition problems in old age.

• Reclassifying childhood disorders such as ADHD as neurodevelopmental disorders.

• Adding the diagnosis of “Binge-Eating Disorder.”

What are some criticisms of the changes made to the DSM-5?

Some psychiatrists believe that elements of the DSM-5 are deeply flawed. “Excessive ambition combined with disorganized execution led inevitably to many ill-conceived and risky proposals,” writes Allen Frances, chair of the DSM-IV Task Force and a professor emeritus at Duke, which could lead to misdiagnosis and overprescribing, especially for children.

The most concerning changes of the DSM-5, Frances believed, include incorporating grief into major depressive disorder, diagnosing typical forgetting in old age as Minor Neurocognitive Disorder, and introducing the concept of behavioral addictions.

Are there alternative diagnostic manuals to the DSM?

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD), published by the World Health Organization, is the best known and most popular alternative to the DSM. It contains diagnostic codes used for tracking incidence and prevalence rates, as well as for health insurance reimbursement, for mental and physical disease diagnoses.

Other alternatives to the DSM include the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual (PDM), Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP), Research Domain Criteria (RDoC), and Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF).

What is HiTOP?

The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP)—accounts for mental illness at multiple conceptual levels. It covers specific symptoms (such as avoidance, social anxiety, and suicidality) and traits (callousness, distractibility), but also more general factors with names such as Distress and Fear. The DSM, by contrast, tends to be categorical and binary.

The DSM, by contrast, tends to be categorical and binary.

The HiTOP model is dimensional: A person can score low, high, or somewhere in between on various measures. These severity scores can apply to the more general factors of psychopathology as well as to the narrower ones. As proponents of the model note, evidence suggests that most kinds of psychopathology lie on a continuum with normality.

Essential Reads

Recent Posts

Article 5. Rights of persons suffering from mental disorders \ ConsultantPlus

Article 5. Rights of persons suffering from mental disorders

(1) Persons suffering from mental disorders have all the rights and freedoms of citizens provided for by the Constitution of the Russian Federation and federal laws. Restriction of the rights and freedoms of citizens associated with a mental disorder is permissible only in cases provided for by the laws of the Russian Federation.

(as amended by Federal Law No. 122-FZ of August 22, 2004)

122-FZ of August 22, 2004)

(see the text in the previous edition)

(2) All persons suffering from mental disorders, in the provision of psychiatric care, are entitled to:

respectful and humane treatment, excluding humiliation of human dignity;

receive information about their rights, as well as in a form accessible to them and taking into account their mental state, information about the nature of their mental disorders and the methods of treatment used;

psychiatric care in the least restrictive conditions, if possible at the place of residence;

stay in a medical organization providing psychiatric care in inpatient settings, only for the period necessary to provide psychiatric care in such conditions;

(as amended by Federal Law No. 317-FZ of November 25, 2013)

(see the text in the previous edition)

all types of treatment (including spa treatment) for medical reasons;

providing psychiatric care in conditions that meet sanitary and hygienic requirements;

prior consent and refusal at any stage to use as an object of testing methods of prevention, diagnosis, treatment and medical rehabilitation, medicinal products for medical use, specialized medical foods and medical devices, scientific research or education, from photo, video, or filming;

(as amended by Federal Laws No. 185-FZ of 02.07.2013, No. 317-FZ of 25.11.2013)

185-FZ of 02.07.2013, No. 317-FZ of 25.11.2013)

(see the text in the previous version)

invitation, at their request, of any specialist involved in the provision of psychiatric care, with the consent of the latter, to work in a medical commission on matters regulated by this Law;

assistance of a lawyer, legal representative or other person in the manner prescribed by law.

(3) Restriction of the rights and freedoms of persons suffering from mental disorders only on the basis of a psychiatric diagnosis, facts of being under dispensary observation or stay in a medical organization providing psychiatric care in inpatient conditions, as well as in an inpatient social service organization intended for persons those suffering from mental disorders are not allowed. Officials guilty of such violations are liable in accordance with the legislation of the Russian Federation and the constituent entities of the Russian Federation.

(as amended by Federal Laws No. 122-FZ of 22.08.2004, No. 185-FZ of 02.07.2013, No. 317-FZ of 25.11.2013, No. 358-FZ of 28.11.2015)

122-FZ of 22.08.2004, No. 185-FZ of 02.07.2013, No. 317-FZ of 25.11.2013, No. 358-FZ of 28.11.2015)

(see text) previous version)

What is a mental disability? How to communicate with such people and are they dangerous? Shameful Questions About Mental Disorders - Meduza

JR Korpa / Unsplash

The lack of information about people with mental disorders breeds wariness: it is not clear what to expect from such a person and how not to offend by accident. At the request of Meduza, the creators of the Pinel Case project, dedicated to the legal side of psychiatric care, answer embarrassing questions about mental disorders and mental disabilities.

You are reading an article published as part of our MeduzaCare charity support program. In November 2019, it is dedicated to people with disabilities. All program materials are on a special screen.

What is a mental disability? Is that a polite name for mental retardation?

Mental disability is a disability caused by a mental disorder.

Mental disorder in itself does not necessarily lead to disability. Mental disorders differ from each other: some do not last long and do not have serious consequences for the patient's life, while others become chronic and significantly change a person's life.

Disability is a social concept. It is assigned if, due to illness or injury, a person cannot (or can, but with difficulty) independently move, study, work and communicate. Panic attacks, depression, and in some cases schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder (BAD) may not affect the above abilities - in such cases there will be no basis for establishing disability.

Disability can be obtained by patients with severe chronic mental disorders: for example, people with schizophrenia, mental retardation, the consequences of traumatic brain injuries, strokes and brain hemorrhages, people with dementia. Severe bipolar disorder or recurring episodes of depression can also lead to disability. It is important that the cause of disability will not be the disorder itself, but the inability to do without help in daily life. In official documents, this is called life restriction.

In official documents, this is called life restriction.

In order for a person to be granted a disability, it is necessary to confirm officially that he needs social assistance. In Russia, this is done by the Bureau of Medical and Social Expertise (ITU).

Doctors work in them, but the institutions themselves do not belong to the Ministry of Health, but to the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection. Employees of the ITU bureau establish a disability group, decide whether a person needs rehabilitation and care equipment (canes, wheelchairs, diapers, and much more, including guide dogs). Disability due to a mental disorder is established by specialized ITU bureaus, where psychiatrists work. Patients with mental disorders can be assigned the third, second or first disability group (arranged in ascending order of the degree of disability), and a child under 18 years of age will be assigned the status of a "disabled child".

The disability certificate issued by the ITU does not include a diagnosis. In the column "Cause of disability" there may be the wording "general disease" - it is most often found in mental disorders.

In the column "Cause of disability" there may be the wording "general disease" - it is most often found in mental disorders.

Do people with mental disabilities understand that they have a mental disability?

Most people with a mental disability understand that they have been assigned a disability group. Some people with mental disorders do not understand that they are people with disabilities. But, as a rule, these are patients with a markedly reduced memory and intelligence (for example, with dementia), and in their case, a lack of understanding of their social status is the least of the problems.

How should you behave when dealing with such a person?

Mental disorder will not necessarily be noticeable when communicating with a person. The same applies to disability. But if you know about the disability of the interlocutor or his relative, it is better to postpone inquiries about this until a closer acquaintance, so as not to create a situation in which everyone will be embarrassed.

It is also not worth asking why a healthy-looking person with a disability does not work. Chronic mental disorders often develop in people at a young or adult age. A person may appear to be physically healthy, but the decreased willpower and thought disturbances of schizophrenia, for example, impair the ability to work just like any other serious illness or injury.

What are the public policy options in the world towards such people? What is the best approach?

It may seem that pensions and free medicines are enough to provide social support for people with disabilities, but this is not the case.

Firstly, the size of the disability pension (and it is less than the labor pension) does not allow us to talk about the possibility of a decent life. The pension is supplemented by benefits for travel and medicines that a person can dispose of independently - for example, refuse them in favor of monetary compensation. But with any choice, he will remain in a vulnerable position: on the one hand, monetary compensation is small, on the other hand, there are interruptions in the purchases of drugs that are carried out by the regional ministries of health with federal budget money.

Secondly, the life of a person with a disability, like other people, is not limited to payments and medicines. A good option for government assistance is assisted living programs. They allow a person with a disability to live independently, provided that they receive regular visits from a social worker. For example, in Finland, such support is mainly provided by non-profit organizations (NPOs). Now this practice is coming to other countries, including Russia.

Another option for social assistance is supported employment. Disability is not always associated with a complete loss of the ability to study or work. A person with a severe or chronic mental disorder involved in the labor process simultaneously trains social skills and experiences a sense of his own need, inclusion in society, which is important for the well-being of any person. In Russia, there are already the first attempts to introduce such employment, but it is still far from widespread practice.

In general, assistance to people with disabilities should cover different aspects of life and at the same time be tailored to individual needs. This can be achieved with the help of a state program, different parts of which are carried out by different NGOs specializing in certain narrow tasks.

This can be achieved with the help of a state program, different parts of which are carried out by different NGOs specializing in certain narrow tasks.

This requires not only money and trained specialists, but two more factors: the will of the state for such changes and the readiness of society to see people with disabilities as part of its usual environment.

A separate problem is people with mental and central nervous system disorders who are not capable of even minimal personal care. In Russia, there are no exact statistics for this group, but, most likely, we are talking about hundreds and thousands of people across the country. Such people need constant professional care, and it is almost impossible to provide it at home. As a rule, sooner or later they end up in psycho-neurological boarding schools (PNI) - places with notoriety. It would be strange to completely close the PNI without having an alternative - but it is necessary to reform them in the direction of greater humanity.

Can people with mental disabilities get married and raise children?

People with mental disabilities start relationships, get married and have children. Not everyone does this, and the reason here is not only the disease itself, but also its stigmatization.

Any prohibition based on social status is discrimination. By itself, disability and the inability to work does not mean that a person should be deprived of life in society and the chance to start a family. Health and success in family relationships are not directly related. In the end, there are a lot of healthy and able-bodied people who do not cope with the upbringing of their children and even harm them.

A person with a disability does not stop being a person. Even if it seems ridiculous or ridiculous to us that such people also want relationships and sex, such a reaction characterizes us rather than people with disabilities.

People with severe mental disorders have the right to have sex like everyone else if they want to. Sex is an important source of positive emotions and a way to strengthen relationships, including for people with disabilities.

Sex is an important source of positive emotions and a way to strengthen relationships, including for people with disabilities.

Sex education for children and adolescents with mental problems plays a separate role. It is not only about contraceptive skills, but more about learning about your body and the rules of sexual safety. A child or teenager with an intellectual disability can easily become a victim of sexual assault, and education can help reduce the risk.

JR Korpa / Unsplash

Is inclusive education for people with mental disabilities a good thing? Will mentally healthy children not suffer?

The key to the success of inclusive education is the acceptance of a different student or student by the group and teachers. Without this, education will not bring any benefit and may even harm.

Parents of other children may fear that a child with disabilities will draw all the attention of teachers to himself or violate discipline in the classroom - and this will affect the progress of everyone else. There are two answers to this.

There are two answers to this.

First, even a mentally healthy student can violate discipline and interfere with others. Secondly, inclusive education requires good preparation not only for teachers and the class, but also for the child himself. Not every child with a mental disorder can attend a regular school. Special educational programs have been developed for such children, including individual and home-based ones.

On the other hand, if inclusive education is properly organized, students of this class get a unique social experience, improve communication skills and emotional response. After all, study is a source of not only knowledge, but also social skills, and it is difficult to say which is more important.

The benefits for students with mental disabilities are also clear—they receive an education with good prospects and are better prepared for life in society.

Does mental disability mean total disability?

No, it doesn't. Incapacity is a legal category that means the inability of a person to direct his actions or understand their meaning. It requires proof in a special order - through a court session and a forensic psychiatric examination.

It requires proof in a special order - through a court session and a forensic psychiatric examination.

In itself, a disability due to a mental disorder, even the first group, does not mean automatic deprivation of legal capacity. And not every person with a mental disability can be deprived of legal capacity.

Why does this happen to people at all?

As we have said, mental disorders do not always lead to disability. As a rule, chronic diseases that lead to irreversible changes in the structure and functioning of the brain become the cause of disability.

For example, some of the symptoms of schizophrenia—hallucinations and delusions—can be managed with medication. But for other symptoms - specific disturbances in thinking and loss of impulses and brightness of emotions - antipsychotics have little or no effect at all. The cause of disability in schizophrenia is often problems with the performance of normal work tasks and a violation of purposeful activities.

Alzheimer's dementia and vascular dementia cause memory problems and loss of self-care skills. Because of this, an elderly person needs constant help and can be assigned a disability.

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) also identifies a group of mental disorders in which normal brain development does not occur. Their cause can be injuries, diseases of the nervous system (epilepsy), metabolic disorders (phenylketonuria), chromosomal disorders (Down syndrome) and much more. Patients with these disorders often have difficulty learning the knowledge and skills needed to live and work independently. This also becomes a reason for establishing disability, usually from childhood.

There is an opinion that people with bipolar disorder and depression do not get disabled, but this is not true. A severe degree of bipolar disorder or frequently recurring depressive episodes can deprive a person of the opportunity to work, and this is already the basis for obtaining a disability.

Are people with mental disabilities dangerous?

There are no studies that confirm that people with a mental disability are more dangerous than people without it. At the same time, studies show that patients suffering from mental disorders are more likely to become victims of crime than criminals. Patients with mental disorders and those who have received a disability are a vulnerable social group that needs the protection and support of society, and not additional control of law enforcement agencies.

How to offer help to a person with a mental disability or their loved one, so that it is not intrusive and does not question their abilities?

As with other people, it is important to show your willingness to help. Not all people with a mental disorder and disability need constant help. Many of them cope with everyday activities, but need help with more complex tasks - just like healthy people. It will be enough to clearly indicate your readiness to help if this help is needed.