Manic depression cycle

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

HomeWelcome to the Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator, a confidential and anonymous source of information for persons seeking treatment facilities in the United States or U.S. Territories for substance use/addiction and/or mental health problems.

PLEASE NOTE: Your personal information and the search criteria you enter into the Locator is secure and anonymous. SAMHSA does not collect or maintain any information you provide.

Please enter a valid location.

please type your address

-

FindTreatment.

gov

gov Millions of Americans have a substance use disorder. Find a treatment facility near you.

-

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

Call or text 988

Free and confidential support for people in distress, 24/7.

-

National Helpline

1-800-662-HELP (4357)

Treatment referral and information, 24/7.

-

Disaster Distress Helpline

1-800-985-5990

Immediate crisis counseling related to disasters, 24/7.

- Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Finding Treatment

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Facility Directors

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Other Locator Functionalities

- Download Search ResultsDownload Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Print Search ResultsPrint Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). - Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). Find programs providing methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

The Locator is authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act (Public Law 114-255, Section 9006; 42 U.S.C. 290bb-36d). SAMHSA endeavors to keep the Locator current. All information in the Locator is updated annually from facility responses to SAMHSA’s National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (N-SUMHSS). New facilities that have completed an abbreviated survey and met all the qualifications are added monthly. Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Bipolar Disorder | Symptoms, complications, diagnosis and treatment

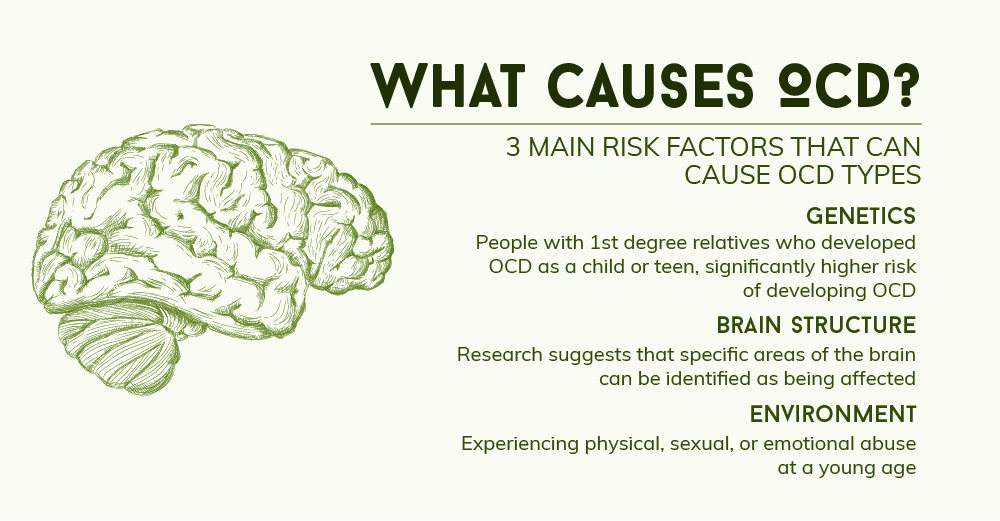

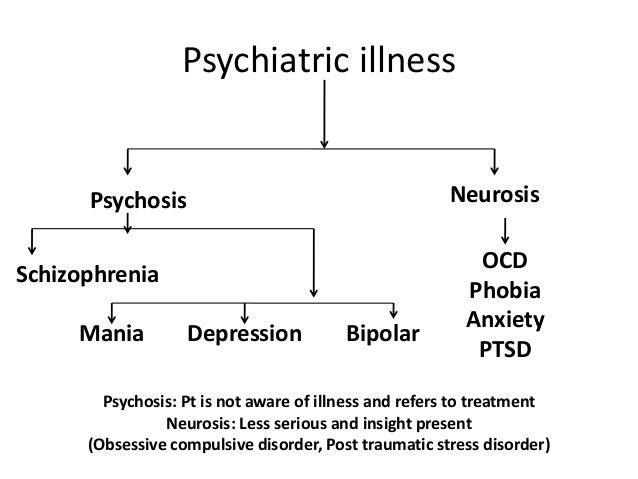

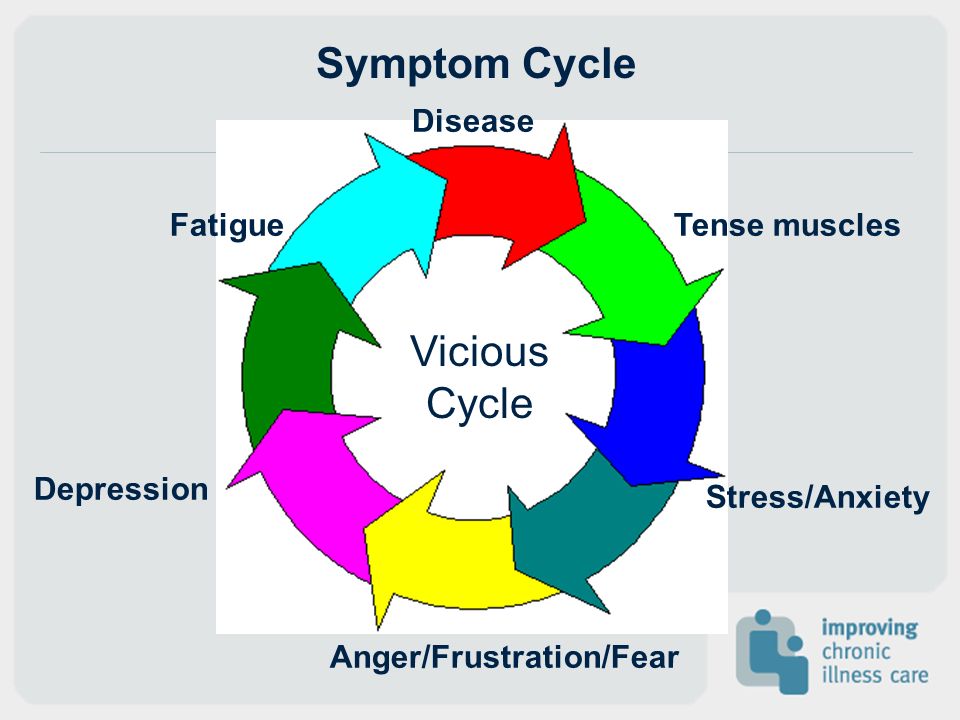

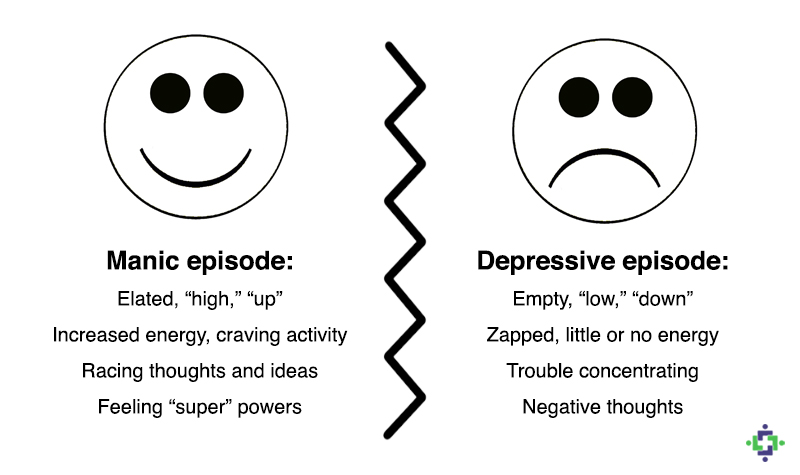

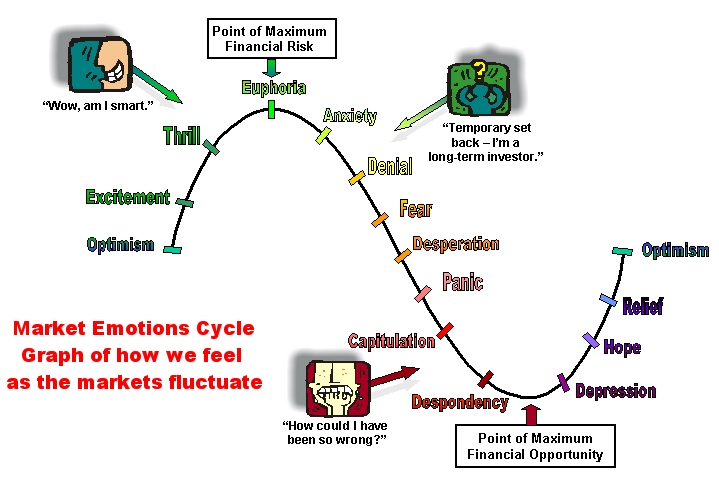

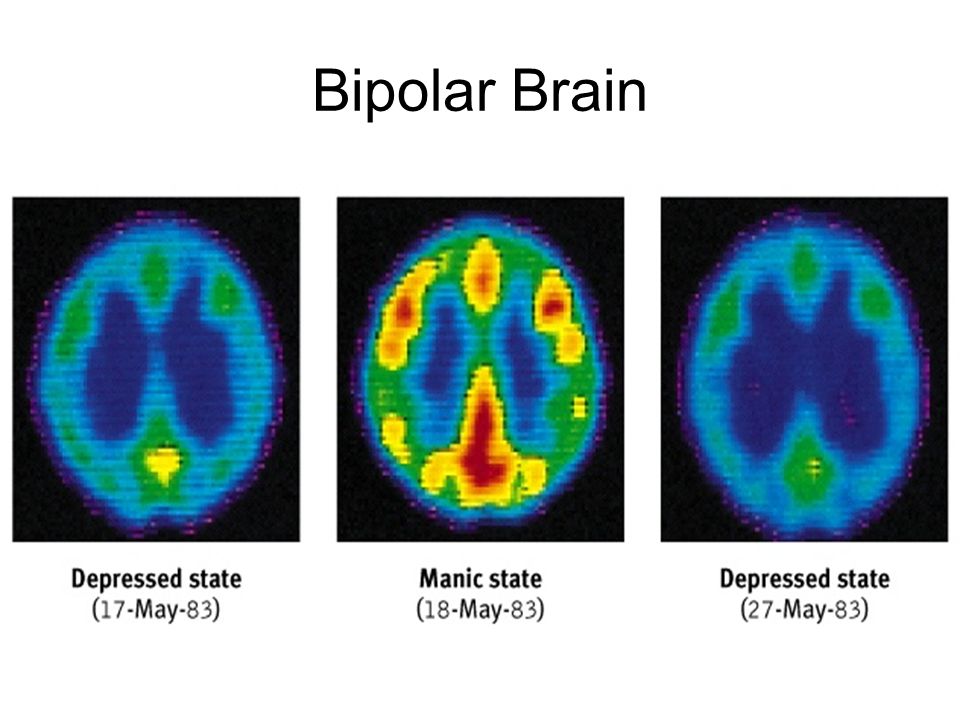

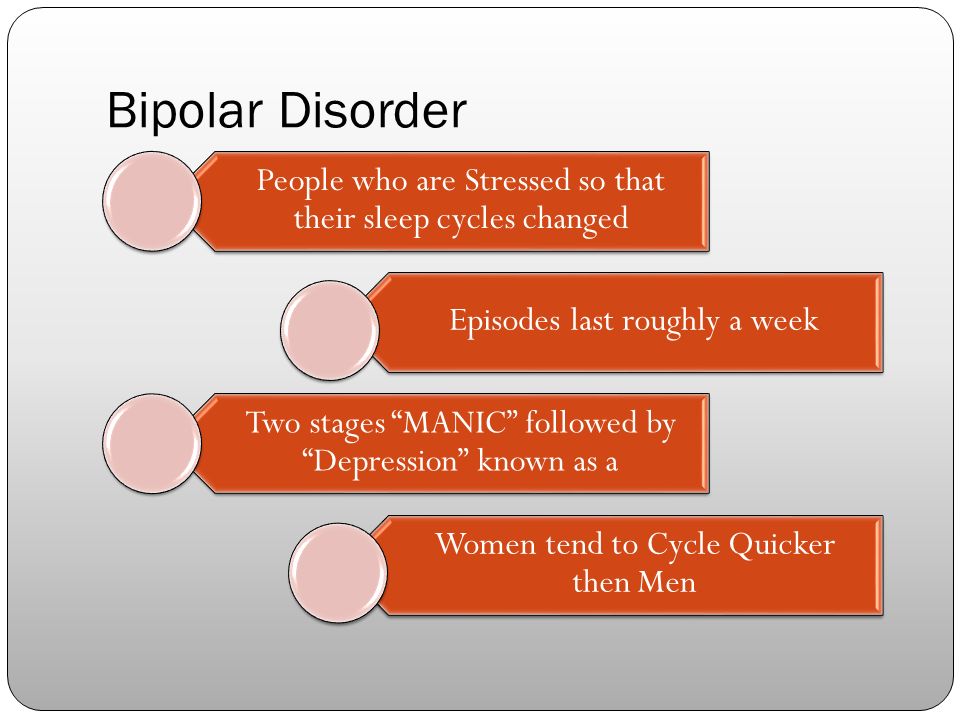

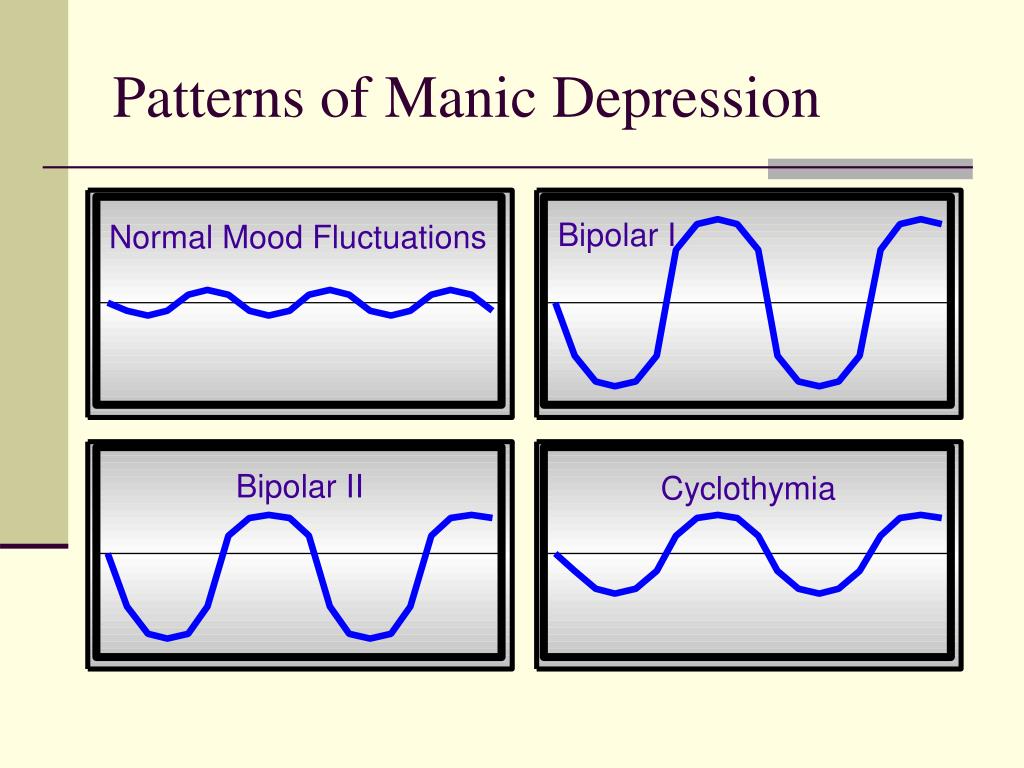

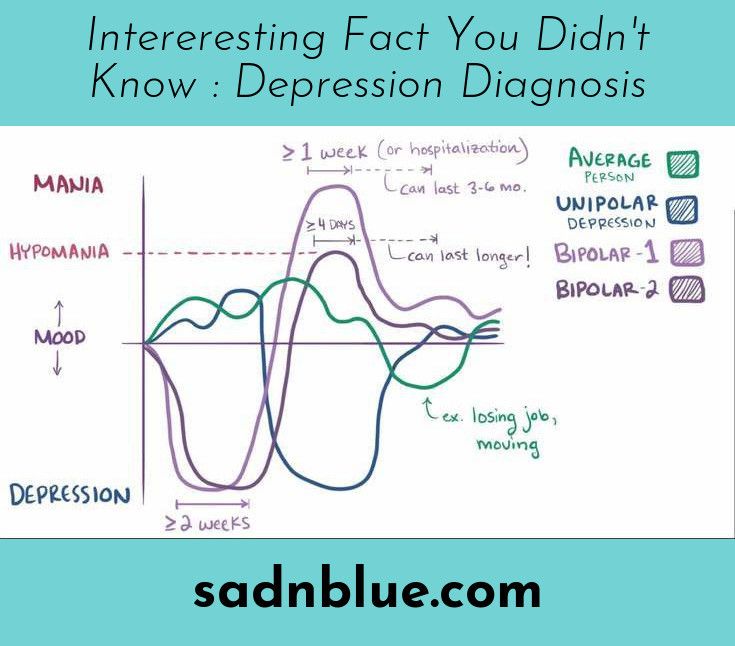

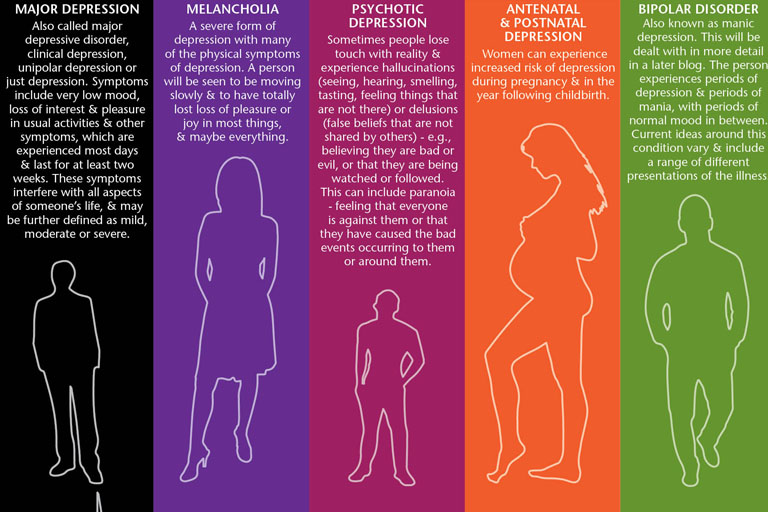

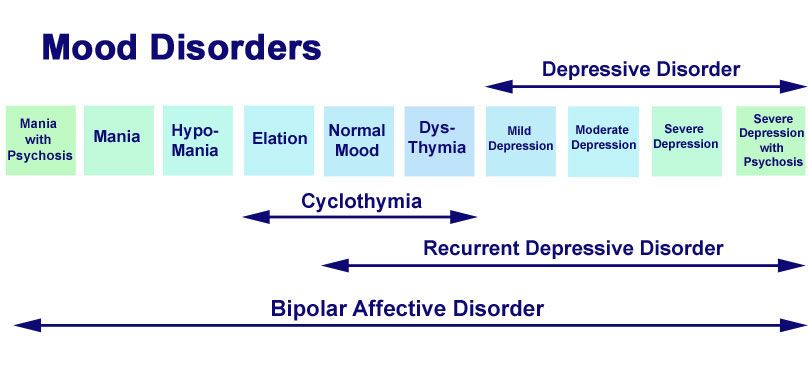

Bipolar disorder, formerly called manic depression, is a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings that include emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression). Episodes of mood swings may occur infrequently or several times a year.

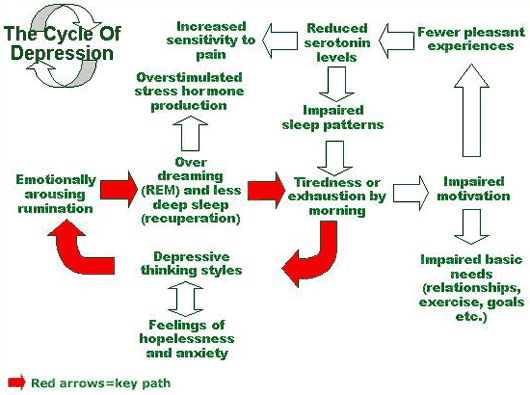

When you become depressed, you may feel sad or hopeless and lose interest or pleasure in most activities. When the mood shifts to mania or hypomania (less extreme than mania), you may feel euphoric, full of energy or unusually irritable. These mood swings can affect sleep, energy, alertness, judgment, behavior, and the ability to think clearly.

These mood swings can affect sleep, energy, alertness, judgment, behavior, and the ability to think clearly.

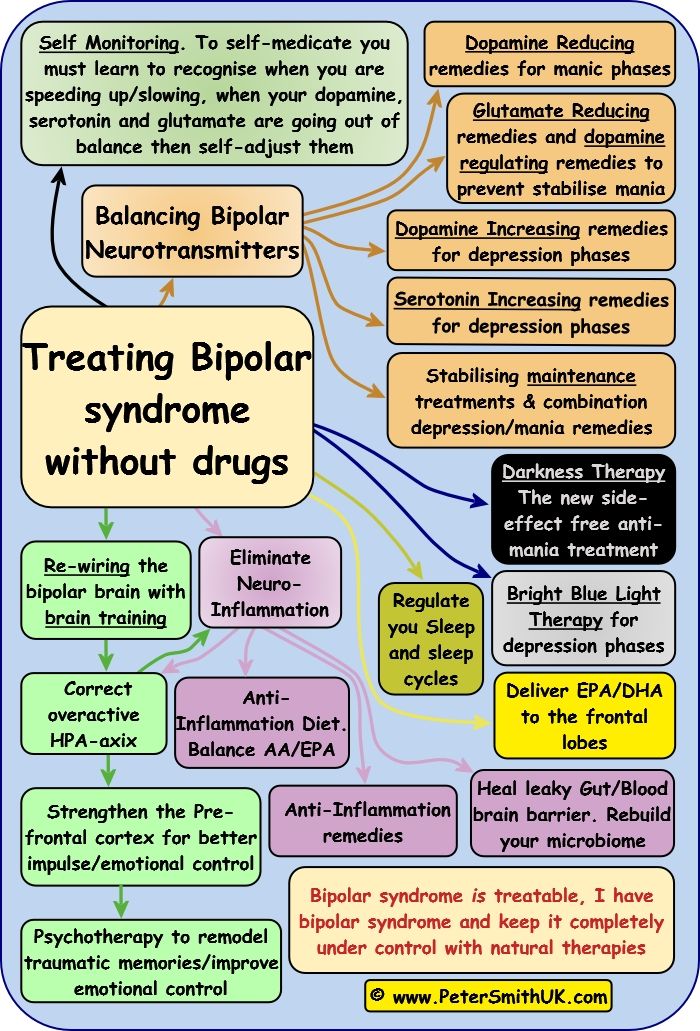

Although bipolar disorder is a lifelong condition, you can manage your mood swings and other symptoms by following a treatment plan. In most cases, bipolar disorder is treated with medication and psychological counseling (psychotherapy).

Symptoms

There are several types of bipolar and related disorders. These may include mania, hypomania, and depression. The symptoms can lead to unpredictable changes in mood and behavior, leading to significant stress and difficulty in life.

- Bipolar disorder I. You have had at least one manic episode, which may be preceded or accompanied by hypomanic or major depressive episodes. In some cases, mania can cause a break with reality (psychosis).

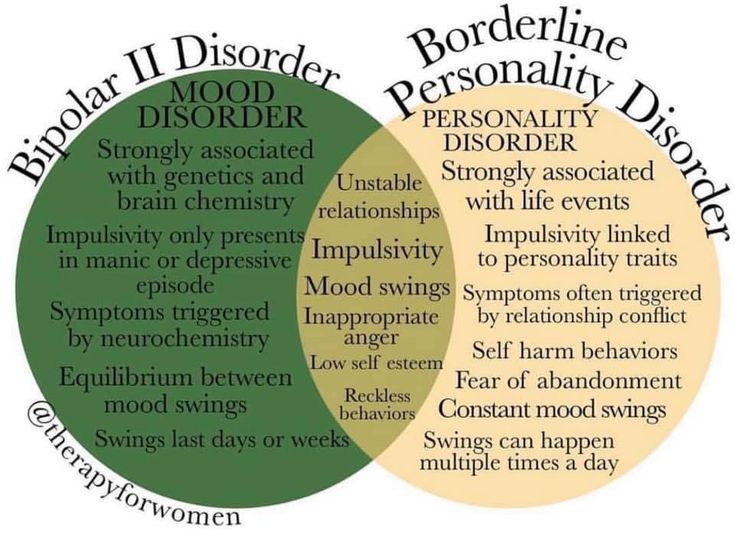

- Bipolar disorder II. You have had at least one major depressive episode and at least one hypomanic episode, but never had a manic episode.

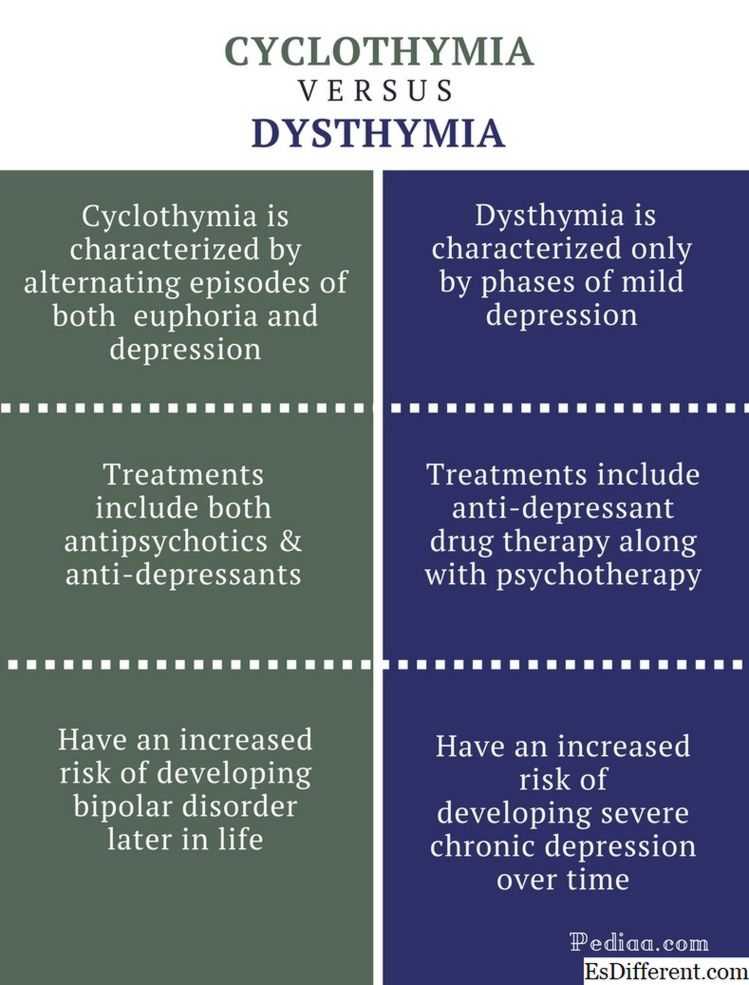

- Cyclothymic disorder. You have had at least two years - or one year in children and adolescents - many periods of hypomanic symptoms and periods of depressive symptoms (though less severe than major depression).

- Other types. These include, for example, bipolar and related disorders caused by certain drugs or alcohol, or due to health conditions such as Cushing's disease, multiple sclerosis, or stroke.

Bipolar II is not a milder form of Bipolar I but is a separate diagnosis. Although bipolar I manic episodes can be severe and dangerous, people with bipolar II can be depressed for longer periods of time, which can cause significant impairment.

Although bipolar disorder can occur at any age, it is usually diagnosed in adolescence or early twenties. Symptoms can vary from person to person, and symptoms can change over time.

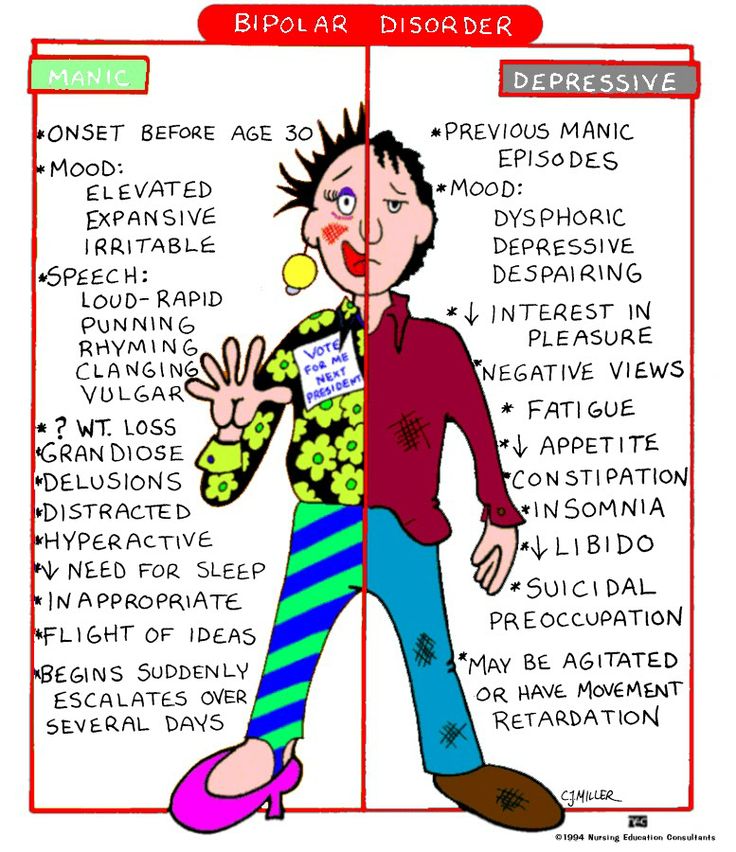

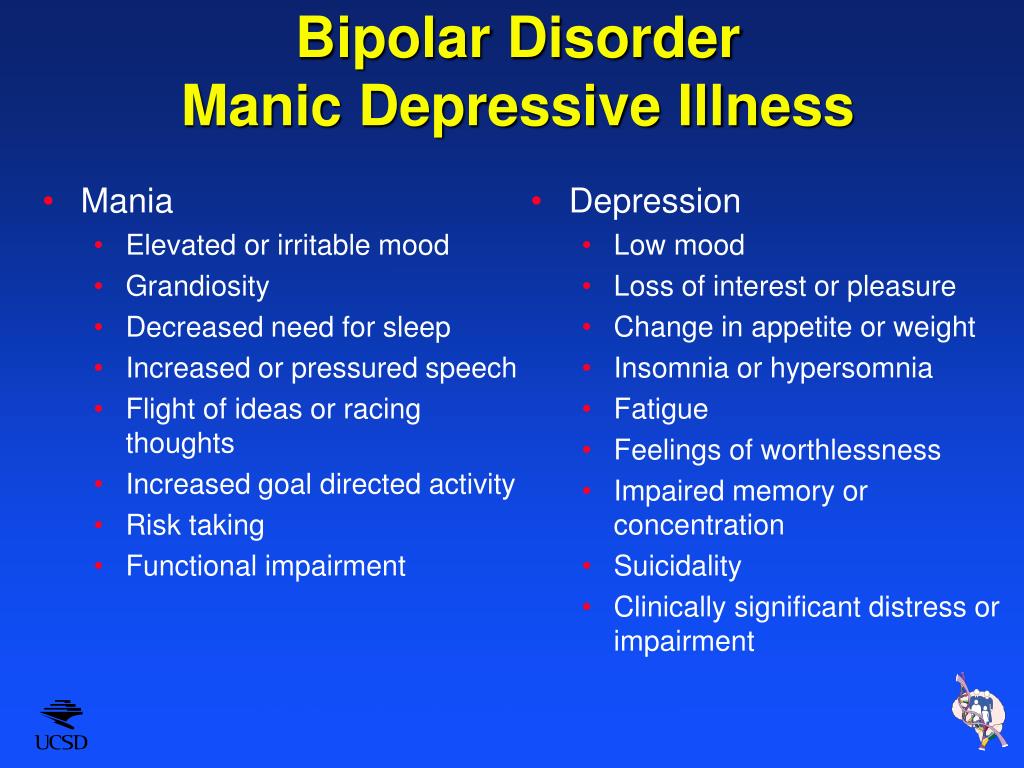

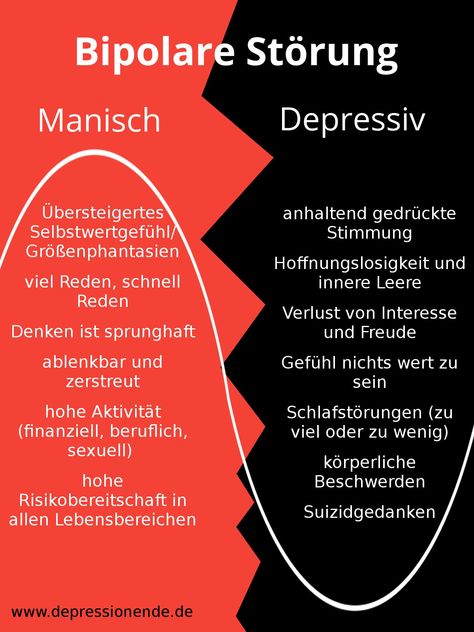

Mania and hypomania

Mania and hypomania are two different types of episodes, but they share the same symptoms. Mania is more pronounced than hypomania and causes more noticeable problems at work, school, and social activities, as well as relationship difficulties. Mania can also cause a break with reality (psychosis) and require hospitalization.

Mania is more pronounced than hypomania and causes more noticeable problems at work, school, and social activities, as well as relationship difficulties. Mania can also cause a break with reality (psychosis) and require hospitalization.

Both a manic episode and a hypomanic episode include three or more of these symptoms:

- Abnormally optimistic or nervous

- Increased activity, energy or excitement

- Exaggerated sense of well-being and self-confidence (euphoria)

- Reduced need for sleep

- Unusual talkativeness

- Distractibility

- Poor decision-making - for example, in speculation, in sexual encounters or in irrational investments

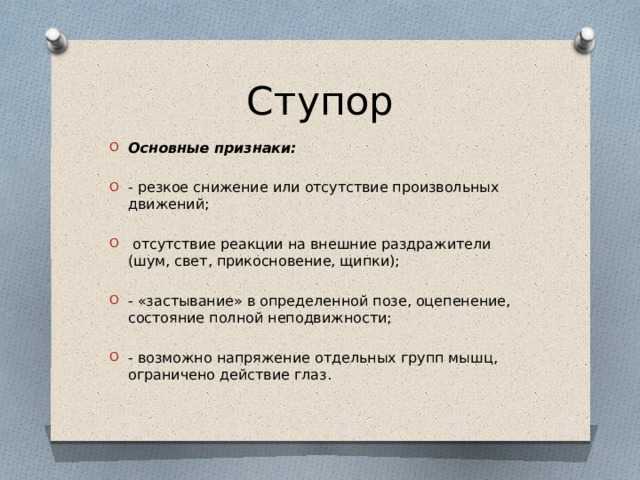

Major depressive episode

Major depressive episode includes symptoms that are severe enough to cause noticeable difficulty in daily activities such as work, school, social activities, or relationships. Episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

- Depressed mood, such as feeling sad, empty, hopeless, or tearful (in children and adolescents, depressed mood may manifest as irritability)

- Marked loss of interest or feeling of displeasure in all (or nearly all) activities

- Significant weight loss with no diet, weight gain, or decreased or increased appetite (in children, failure to gain weight as expected may be a sign of depression)

- Either insomnia or sleeping too much

- Either anxiety or slow behavior

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Decreased ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness

- Thinking, planning or attempting suicide

Other features of bipolar disorder

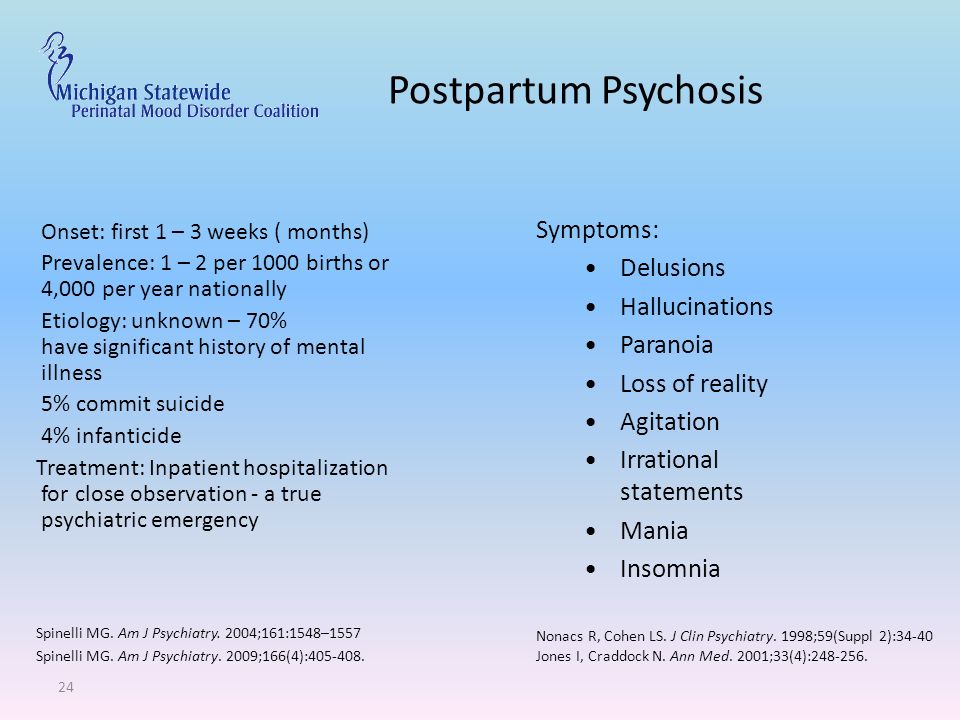

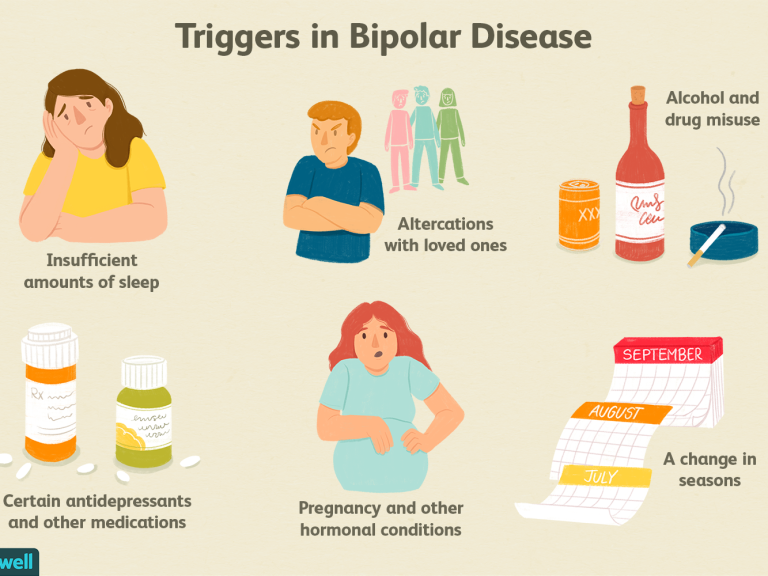

Signs and symptoms of bipolar I and bipolar II disorder may include other signs such as anxiety disorder, melancholia, psychosis, or others. The timing of symptoms may include diagnostic markers such as mixed or fast cycling. In addition, bipolar symptoms may occur during pregnancy or with the change of seasons.

The timing of symptoms may include diagnostic markers such as mixed or fast cycling. In addition, bipolar symptoms may occur during pregnancy or with the change of seasons.

When to see a doctor

Despite extreme moods, people with bipolar disorder often do not realize how much their emotional instability disrupts their lives and the lives of their loved ones and do not receive the necessary treatment.

And if you are like people with bipolar disorder, you can enjoy feelings of euphoria and be more productive. However, this euphoria is always accompanied by an emotional disaster that can leave you depressed and possibly in financial, legal, or other bad relationships.

If you have symptoms of depression or mania, see your doctor or mental health professional. Bipolar disorder does not improve on its own. Getting mental health treatment with a history of bipolar disorder can help control your symptoms.

FGBNU NTsPZ.

‹‹Depression and depersonalization››

‹‹Depression and depersonalization›› There are very few data on the course of MDP. Even Kraepelin (1904) pointed out that it is irregular and unpredictable at the present level of knowledge. He only noted that the frequency and duration of the phases increase with time and that the first intermission, as a rule, turns out to be the longest. Later M. Kinkelin (1954) confirmed these observations, showing that the average duration of depressive states increases from the 1st to the 5th phase, and this trend is associated with hereditary burden.

Subsequently, a number of studies confirmed the general tendency of MDP to lengthen seizures and reduce interictal intervals as the disease progresses.

A number of parameters to a certain extent characterize the course in each particular case. This is the age at which psychosis debuted (early - late onset), regularity - irregularity of seizures. One of the options for a regular course is seasonality, since depressive states, like manic states, often occur in spring and then in autumn. Recently, great importance has been attached to the polarity of psychosis: in the presence of only depressive phases - monopolar, in depressive and manic - bipolar. Monopolar mania is very rare. There are several variants of the bipolar course: sometimes the bipolar rhythm is established after the very first attacks of psychosis, and in this course the phases - manic and depressive - are usually separated by intermissions. In other cases, especially with prolonged and intensive use of antidepressants, unipolar depression gradually passes to a bipolar course: first, after the end of the next depression, a short (sometimes several hours) hypomanic episode occurs, after the next depression it lasts 12 hours or 1 day, then - several days , and typical double phases gradually form. With a sufficiently long course, the dual phases tend to move into a continuously circular course without remissions. The course of MDP is also characterized by the duration of the phases, gradual or acute onset and regression of symptoms, the duration and purity of the intermissions (sometimes short subclinical depressive or depressive and manic episodes occur during the intermission period), the structure of the phase: prolonged depression can proceed monotonously or be undulating, and sometimes the phase consists, as it were, of packs of short depressions.

Recently, great importance has been attached to the polarity of psychosis: in the presence of only depressive phases - monopolar, in depressive and manic - bipolar. Monopolar mania is very rare. There are several variants of the bipolar course: sometimes the bipolar rhythm is established after the very first attacks of psychosis, and in this course the phases - manic and depressive - are usually separated by intermissions. In other cases, especially with prolonged and intensive use of antidepressants, unipolar depression gradually passes to a bipolar course: first, after the end of the next depression, a short (sometimes several hours) hypomanic episode occurs, after the next depression it lasts 12 hours or 1 day, then - several days , and typical double phases gradually form. With a sufficiently long course, the dual phases tend to move into a continuously circular course without remissions. The course of MDP is also characterized by the duration of the phases, gradual or acute onset and regression of symptoms, the duration and purity of the intermissions (sometimes short subclinical depressive or depressive and manic episodes occur during the intermission period), the structure of the phase: prolonged depression can proceed monotonously or be undulating, and sometimes the phase consists, as it were, of packs of short depressions.

As indicated, in each case the individual course is determined by a combination of these parameters.

In order to identify the interaction of these trends and their possible relationship with certain etiopathogenetic factors, we undertook to study the course of TIR using factor analysis, the possibilities and advantages of which were described earlier.

The material of the study was data on the course of psychosis, hereditary burden, exogenous hazards and character traits of 75 patients with manic-depressive psychosis. They were selected from more than 300 patients with "typical" manic-depressive psychosis, who were under our supervision for 10 years.

The criterion for the selection of these 75 patients, in addition to the "typical" psychosis, was the duration of the disease (at least 10 years) and the number of attacks (at least 4 phases). Most of them were observed by us during several attacks of psychosis and in light intervals. Among the patients there were 37 women and 38 men. Of these, 49 had both manic and depressive states, 26 had only depressive states. The age of onset of the disease ranged from 9 to 55 years (mean 27.7 years), the duration of the disease was from 10 to 51 years (mean 21.8 years). Hereditary burden was detected in 62% of patients. Neither in attacks, nor in light intervals in patients, symptoms heterogeneous for MDP were found.

Of these, 49 had both manic and depressive states, 26 had only depressive states. The age of onset of the disease ranged from 9 to 55 years (mean 27.7 years), the duration of the disease was from 10 to 51 years (mean 21.8 years). Hereditary burden was detected in 62% of patients. Neither in attacks, nor in light intervals in patients, symptoms heterogeneous for MDP were found.

For processing by the method of factor analysis (Programs for factor analysis were compiled by T. P. Kister. Processing was carried out on the BESM-4 computer) 28 signs were selected: the first 13 characterized the patient's heredity and premorbidity, the remaining 15 - the course of the process. The following is a list of these signs:

1. Homogeneous heredity 1.

2. Heterogeneous heredity (schizophrenia and other delusional psychoses).

3. Heterogeneous "organic" heredity (epilepsy, oligophrenia, gross organic psychoses).

4. Hereditary burden of diabetes.

5. Malaria.

6. Severe infections in childhood (with hyperpyrexia, convulsive seizures, impaired consciousness, infectious delirium, etc.).

7. Rheumatism.

8. Tuberculosis.

9. Head trauma with loss of consciousness.

10. Prolonged psychogenic stress (only extremely severe and prolonged psycho-traumatic situations were taken into account).

11. The index of the sum of exogenous hazards (all serious illnesses, injuries, contusions, alimentary dystrophy, etc., transferred in the premorbid),

12. Hyperthymic character.

13. Anxious and suspicious nature.

14. Age of onset.

15. Duration of the disease.

16. Age of the patient at the last registration of his condition.

17. Provocation of the first phase.

18. Duration of the first intermission.

19. Average number of months of illness (manic and depressive) per 1 year of illness.

20. The indicator of the increase in the total duration of the phases (quotient from dividing the total duration of all phases of the 2nd half of the disease by the sum of the duration of all phases of the 1st half).

21. Average number of phases per 1 year of illness.

22. The indicator of the increase in the frequency of phases (private separation of the number of phases of the 2nd half of the disease by the number of phases of the 1st half, the 1st phase was not taken into account, as in sign 20).

23. The average duration of depressive phases, starting from the 3rd phase.

24. Index of elongation of depressive phases (quotient from dividing the total duration of the last phases by the sum of the duration of an equal number of the first phases, starting from the 3rd). If the number of phases was odd, the middle phase was not taken into account. So, if the patient underwent 9 phases, then the total duration of the last 3 phases was divided by the total duration of the 3rd, 4th and 5th phases; The first 2 phases and the 6th (middle) phase were not taken into account.

25. The average duration of cycles - the intervals between the onset of subsequent depressive phases, counting from the beginning of the 3rd phase.

26. Cycle shortening indicator (determined similarly to indicator 24 from the beginning of the 3rd cycle).

27. Presence of manic episodes.

28. The ratio of the total duration of manic and depressive phases.

1 Features 1-10, 12, 13, 17, 27 were evaluated alternatively ("0" or "1").

For the reasons given below, the 1st phase was not taken into account; the disease period from the beginning of the 2nd phase to the end was divided in half, and in each half the sum of the duration of the phases in months was calculated). In signs 20 and 22, the dynamics of seizures was taken into account, starting from the 2nd phase. This was due to the fact that during the preliminary analysis of the material it turned out that in some patients the 1st intermission was disproportionately large compared to subsequent light intervals (in some patients up to 20-30 years). Such a long 1st light interval usually covered the entire first half of the disease, as a result of which the severity of the course was very high, regardless of the nature of the further dynamics of the disease. In characters 23, 24, 25, 26, readings began from the 3rd phase, since the first 2 phases and 2 intermissions often differed significantly from the subsequent ones in duration. Indicator 27 was introduced due to the fact that some patients had very short manic episodes (sometimes measured in hours), which are difficult to quantify and express in indicator 28.

Such a long 1st light interval usually covered the entire first half of the disease, as a result of which the severity of the course was very high, regardless of the nature of the further dynamics of the disease. In characters 23, 24, 25, 26, readings began from the 3rd phase, since the first 2 phases and 2 intermissions often differed significantly from the subsequent ones in duration. Indicator 27 was introduced due to the fact that some patients had very short manic episodes (sometimes measured in hours), which are difficult to quantify and express in indicator 28.

The results of the factor analysis of these features are presented in Table. eleven.

TABLE #11

| Results of factor analysis of signs characterizing the course of TIR | |||||

| Factor 1, wt. | Factor 2, factor weight 8% | ||||

| No. | sign | Factor loads | No. | sign | Factor loads |

| Positive | Positive | ||||

| fifteen | Duration of diseases | +0. | twenty | Increase in the total duration of seizures | +0.60 |

| 16 | Patient's age at last follow-up | +0.61 | 24 | Prolongation of depressive phases | +0.54 |

| 25 | The average duration of cycles - intervals between the onset of depressive phases | +0. | 23 | Average duration of depressive phases | +0.47 |

| 23 | Average duration of depressive phases | +0.51 | 19 | Number of months of disease state for 1 year | +0.35 |

| one | Homogeneous heredity | +0. | |||

| Negative | Negative | ||||

| 19 | Number of months of disease state for 1 year | -0.59 | eighteen | Duration of the 1st intermission | -0.41 |

| 21 | Number of phases for 1 year | -0. | eleven | Exogeny | -0.59 |

| 27 | The presence of mania | -0.52 | |||

| 7 | Rheumatism | -0.31 | |||

APPENDIX

| Results of factor analysis of signs characterizing the course of TIR | |||||

| Factor 3, weight. | Factor 4, factor weight 6.8% | ||||

| No. | sign | Factor loads | No. | sign | Factor loads |

| Positive | Positive | ||||

| twenty | Increase in the total duration of seizures | +0. | fourteen | Age of onset | +0.52 |

| 22 | Increasing seizure frequency | +0.54 | 19 | Number of months of disease state for 1 year | +0.40 |

| 16 | Patient's age at last follow-up | +0. | Negative | ||

| 6 | Severe infection in childhood | +0.44 | fifteen | Disease duration | -0.36 |

| eighteen | Duration of the 1st intermission | -0. | |||

| 27 | Presence of mania | -0.33 | |||

| eighteen | The ratio of the total duration of manic and depressive phases | -0.37 | |||

| one | Homogeneous heredity | -0. | |||

The 1st factor was interpreted as a bipolar factor of “saturation of the entire period of the disease with periods of affective disorders”: with a small proportion of periods of affective disorders compared to light intervals at one pole and with a large proportion of these periods (high “saturation” with them) - at the other end of the factor. A favorable trend was characterized by rare, but relatively long depressive phases without manic states, the opposite trend was characterized by frequent, relatively short depressive and manic phases with a predominance of depressive states. This trend correlates with a history of rheumatism. Probably, its extreme expression is a continuous circular type of flow. When looking at the correlations between individual features combined in factor 1, rheumatism was found to be relatively more associated with the presence of mania (+0.27) and early onset psychosis (+0.26).

The 2nd factor was identified as "a factor of increase in severity due to prolongation of seizures". This trend was associated with a homogeneous hereditary burden and negatively correlated with exogenies.

This trend was associated with a homogeneous hereditary burden and negatively correlated with exogenies.

The 3rd factor was interpreted as "a factor of increasing severity due to more frequent seizures." The trend towards an increase in the frequency of seizures was associated with severe infections during childhood, and apparently increased in later life.

4th factor — “late onset factor” — characterizes the tendency towards late onset of psychosis and unipolar course (only depression). This trend was negatively correlated with homogeneous hereditary burden.

Although the selected factors can be easily identified (which indicates that they do reflect clinical reality), their insignificant factor weights still attract attention. Possible explanations for this include the fact that most of the first 13 features are practically independent of each other, as shown by the study of their correlations, and they were evaluated only alternatively ("0" - "1"). Indeed, with separate processing of the last 15 signs describing the course of psychosis, similar factors were identified, but with greater weights of the factors: the 1st factor (“saturation”) had a weight of 21.7%. The coincidence of factors in the processing of all and only part of the features is proof of their stability and reproducibility.

Indeed, with separate processing of the last 15 signs describing the course of psychosis, similar factors were identified, but with greater weights of the factors: the 1st factor (“saturation”) had a weight of 21.7%. The coincidence of factors in the processing of all and only part of the features is proof of their stability and reproducibility.

Thus, the data obtained made it possible to highlight some trends in the course of TIR. Confirmation - that we are really talking about tendencies, and not about independent, isolated variants of the course, are cases when large values of several factors are found in the same patient.

An individual's course of becoming ill is the result of these several tendencies:

1. Tendency to elongation of the phases associated with a homogeneous hereditary burden.

2. Tendency to more frequent phases associated with severe infections in childhood.

3. Tendency to a severe bipolar course with a large number of short phases, weakly associated with rheumatism.

As mentioned above, a large tendency to phase lengthening in hereditarily burdened patients was described earlier (Kinkelin M., 1954). The trend towards an increase in affective seizures is obviously the dominant one in the one described by T. Ya. Khvilivitsky (1959) delayed organic affective psychosis, associated mainly with organic lesions of the central nervous system acquired in early childhood. However, in patients with this form of affective psychosis, the first attacks are grossly atypical, which is how they differ from our patients who did not have symptoms heterogeneous for MDP in the past.

An increase in the frequency of seizures and a disproportionately large (compared with subsequent ones) first light gap are indicators of the arrhythmia of the course of the disease. In the 2nd factor, the long duration of the first intermission negatively correlated with the tendency towards a relatively uniform (by phase frequency) course of MDP associated with homogeneous heredity. In addition, a large first intermission was positively correlated with ex environmental influences.

In addition, a large first intermission was positively correlated with ex environmental influences.

To clarify the role of exogenous hazards during TIR, we conducted an additional study of 368 patients. In 47 patients, the duration of the first intermission exceeded 10 years, and 21 of them (44.7%) had severe infections with cerebral symptoms in childhood. In TIR patients with the first intermission shorter than 10 years, severe infections were found only in 21.3% of cases (in 47 out of 221 patients).

These differences were statistically significant (p<0.05). One of the possible explanations for the association of severe infections accompanied by disorders of the central nervous system with the irregularity of the course of TIR is that, as a result of these diseases, the threshold of resistance to external hazards was lowered. Therefore, in such patients, the occurrence of individual attacks largely depends on random external factors, which is the reason for their irregularity, while in some patients with a homogeneous hereditary burden, the course of the disease is largely determined by its inherent internal patterns, "endogenous rhythm". If so, then in patients with an irregular course of TIR, one would expect a greater purity of provoking factors before the first phase.In the same group of 268 patients with TIR, provoking factors (acute psychotraumatic situations, difficult labor, etc.) occurred in 36, 2% of patients with a large first intermission (over 10 years) and in 23% of patients with shorter first light gaps. Since these differences do not reach a significant level (0.05 < p < 0.1), the questions raised require further research.

If so, then in patients with an irregular course of TIR, one would expect a greater purity of provoking factors before the first phase.In the same group of 268 patients with TIR, provoking factors (acute psychotraumatic situations, difficult labor, etc.) occurred in 36, 2% of patients with a large first intermission (over 10 years) and in 23% of patients with shorter first light gaps. Since these differences do not reach a significant level (0.05 < p < 0.1), the questions raised require further research.

An alternative explanation may also be that the severe reactions that accompanied infectious diseases in childhood and the course of TIR are a consequence of the excessive reactivity of the central nervous system inherent in these patients. It is interesting that the prophylactic effect of lithium, as will be shown below, affects earlier and to a greater extent the duration of depressive phases and less on their frequency. This indirectly points to various pathogenetic mechanisms underlying the two current trends described by the 2nd and 3rd factors.

The relationship of rheumatism with a bipolar course, characterized by frequent short phases, is unclear. It is interesting to note that when only the first 12 signs were processed by factor analysis (the 11th sign was also excluded), rheumatism found a correlation with heterogeneous heredity (involutional, "somatogenic" and other delusional psychoses). It is possible that both rheumatism and the nature of the course of TIR are due to some kind of genetic inferiority of adaptive mechanisms. In any case, this issue requires special study.

As mentioned above, the identified factors do not characterize individual forms of psychosis, but only tendencies in its course. However, factor analysis can contribute to the grouping of patients and the identification of individual variants of the disease.

We selected 5 patients with the highest value of each of the factors. It turned out that three of them simultaneously had the highest values of the first 2 factors. Comparison of these patients showed that they were united by the presence of long-term depressive phases (from 2.5 to 6 years) and the tendency and their lengthening during the course of the disease. In addition, these patients had other common features that were not included in the number of signs studied. These are women with a kind of descending heredity: among their daughters there were patients who were diagnosed with "atypical MDP" in different hospitals. In the 3rd generation, cases of oligophrenia and early schizophrenia were found. The genetic tree of one of these patients is shown in Fig. 1 in ch. 1. All these patients had similar character traits - they were energetic, sthenic, domineering people. The symptomatology of individual phases was typical for MDP and did not contain heterogeneous inclusions. It is interesting that, despite the advanced age (more than 70 years), none of the patients showed pronounced age-related changes in the psyche.

Comparison of these patients showed that they were united by the presence of long-term depressive phases (from 2.5 to 6 years) and the tendency and their lengthening during the course of the disease. In addition, these patients had other common features that were not included in the number of signs studied. These are women with a kind of descending heredity: among their daughters there were patients who were diagnosed with "atypical MDP" in different hospitals. In the 3rd generation, cases of oligophrenia and early schizophrenia were found. The genetic tree of one of these patients is shown in Fig. 1 in ch. 1. All these patients had similar character traits - they were energetic, sthenic, domineering people. The symptomatology of individual phases was typical for MDP and did not contain heterogeneous inclusions. It is interesting that, despite the advanced age (more than 70 years), none of the patients showed pronounced age-related changes in the psyche.

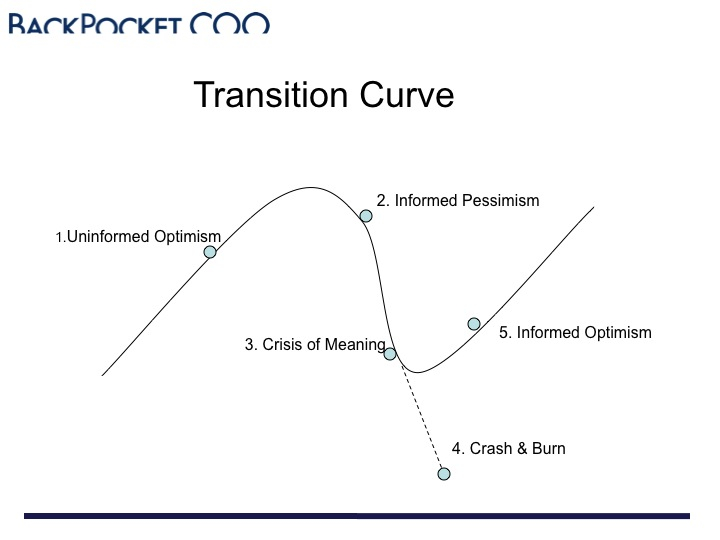

As mentioned above, in almost all cases of MDP there is a tendency for the course of the disease to worsen over time: an increase in and lengthening of the phases, the addition of mania to the previously monopolar course, the formation of dual phases, etc. It can be conditionally imagined that if the duration of the disease were unlimited, then after one or another period of time, all patients would have formed a continuous circular type of flow, which, thus, is, as it were, the logical conclusion of the process.

It can be conditionally imagined that if the duration of the disease were unlimited, then after one or another period of time, all patients would have formed a continuous circular type of flow, which, thus, is, as it were, the logical conclusion of the process.

Just as syndromes reflect the most frequent and persistent combinations of symptoms, individual forms of the course obviously reflect the most frequent and persistent combinations of a number of current trends.

As indicated, a homogeneous hereditary burden is to a greater extent associated with a more or less ordered course, in which there is a gradual increase and lengthening of the phases. On the contrary, organic hazards, more often severe infections with hyperergic reactions transferred in early childhood, are associated with a tendency to an irregular course, with frequent and often short attacks. Characteristic for such patients is the presence of an "extra-long" first intermission and a relatively high frequency of precipitating (provocative) phase of exogenous influences.

It is much more difficult to assess the role of heterogeneous hereditary burden: some patients with hereditary burden of epilepsy have a bipolar course with relatively long depressive and manic phases, and mania usually proceeds in the form of "angry".

It seemed that in the presence of organic psychoses, alcoholic psychosis and schizophrenia along the ascending line, the course of TIR is also characterized by irregularity, frequent short phases, and bipolarity. However, these observations are few. With schizophrenia or "schizoaffective" psychoses in the descending line, patients relatively often experience protracted (1 year or more) phases.

It should be recalled once again that the data obtained by us using factor analysis, as well as the results of this method, are more qualitative than quantitative. They only reveal the interrelationships within the process under study. These results show that there are practically no hard-coded types of course for certain forms of TIR: in each individual case of the disease there are several coexisting trends in the course, each of which, apparently, is associated with certain mechanisms. A set of tendencies subsided, their severity and interaction determine the nature of the course of psychosis in this patient. In other words, there is a kind of layering of various tendencies, the resultant of which is a curve reflecting the course of the disease.

A set of tendencies subsided, their severity and interaction determine the nature of the course of psychosis in this patient. In other words, there is a kind of layering of various tendencies, the resultant of which is a curve reflecting the course of the disease.

Currently, much attention is paid to the polarity of the course of MDP, and a number of authors consider bipolar MDP and unipolar recurrent depression as two independent diseases. There are a number of objections against such a categorical division, and first of all, that a significant part of patients, after a large number of depressive phases, begin to join manic episodes, and then dual phases form. Treatment with some antidepressants seems to reinforce this trend. Nevertheless, the differences between the two types of flow are very distinct (see Table 15).

Very significant differences are found in the onset of the disease: in patients with bipolar MDP, most often the phases of the disease begin quickly, sometimes suddenly, as if “something turned on”, sometimes they are preceded by a short prodrome: insomnia, severe awakenings, sometimes before each phase the patient makes some - certain actions.

factor 13%

factor 13%  71

71  69

69  35

35  50

50  factor 7.8%

factor 7.8%  59

59  50

50  43

43  37

37