Lamictal suicidal thoughts

About Us - San Francisco Suicide Prevention (SFSP)

On October 23, 2014, Bernard Mayes, multi-talented journalist, Episcopal priest, and community activist, passed away in San Francisco. He was the founding force behind the Suicide Prevention movement in America, launching in San Francisco the first of what would eventually become a network of over 500 community crisis centers. He went on to become a pioneer in public broadcasting as a founder of KQED and as chair of the founding board of National Public Radio (NPR). At his side at the end were his friends and former housemates, Will Scott and Matthew Chayt, reading Shakespeare’s Sonnet CXVI, Let me not to the marriage of true minds…

Mayes arrived in San Francisco in 1960 at the age of 31 as a correspondent for the BBC. Handsome, energetic, cultivated, and rebellious, he took on a massive and highly preventable tragedy that no one else would discuss — suicide. In a city that was known for the highest suicide rate in the western world, he founded a simple volunteer hotline using the code name “Bruce” and distributing matchbooks with the phone number in Tenderloin bars.

He had a flair for publicity and was able to maintain constant visibility of the fledgling organization and its efforts to reach people who found themselves wanting to end their lives. He trained its first volunteers and went with them to secure the first office in the basement of a Tenderloin apartment building whose manager initially believed them to be an escort service.

By 1970, he was elected to chair the founding board of NPR, helping to organize public radio and television not only in San Francisco but also for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, then in its infancy. In 1984 he was invited by the University of Virginia to chair their Department of Rhetoric and Communication for which he organized the Program in Media Studies. Later, he was appointed an academic dean and received several awards for mentoring and advising.

He wrote many published articles and a selection of his lighter broadcast pieces, “This is Bernard Mayes in San Francisco,” even appeared in Australia. After his retirement in 1999, he published his autobiography, Escaping God’s Closet: The Revelations of a Queer Priest, which in 2000 won the national Lambda Literary Award for religion and spirituality. He has scripted and recorded dramatic works for radio, including Homer’s Odyssey and award-winning audio of The Lord of the Rings, in which he played Gandalf.

After his retirement in 1999, he published his autobiography, Escaping God’s Closet: The Revelations of a Queer Priest, which in 2000 won the national Lambda Literary Award for religion and spirituality. He has scripted and recorded dramatic works for radio, including Homer’s Odyssey and award-winning audio of The Lord of the Rings, in which he played Gandalf.

Bernard never lost his concern for people considering suicide. For the final years of his life, he returned to San Francisco to live, consistently visiting to the agency he began fifty years earlier. He was a dedicated donor, leader, and historical legacy. Bernard celebrated his 85th birthday on October 10th at San Francisco Suicide Prevention’s “Heroes of Mental Health” Luncheon. He is survived by his many close friends, his former colleagues, and the unknown thousands of people who are alive today because of his work.

We are all better people having had Bernard Mayes in our lives. May he rest in peace.

Written by: Eve Meyer and Meghan Free-beck

To learn more about Bernard‘s legacy, please enjoy the following articles:

- Bernard Mayes to be Honored as Lifeline to Suicidal

- America’s First Suicide Prevention hotline celebrates 50 years

Increased Anxiety, Akathisia, and Suicidal Thoughts in Patients with Mood Disorder on Aripiprazole and Lamotrigine

Case Rep Psychiatry. 2015; 2015: 419746.

Published online 2015 Oct 5. doi: 10.1155/2015/419746

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Introduction. Akathisia affects around 18% of patients with bipolar disorder treated with aripiprazole and may worsen when aripiprazole is combined with lamotrigine and antidepressants. Case. This paper reports on two clinical cases involving patients with a diagnosis of mood disorder who developed severe akathisia, anxiety, and suicidal ideation while using a combination of aripiprazole, antidepressants, and lamotrigine. Discussion. We recommend that patients with a mood disorder taking multiple drugs should begin aripiprazole therapy with low doses and be monitored for the development of akathisia, increased anxiety, or suicidal thoughts. The appearance of these limiting side effects requires discontinuation of the drug.

Discussion. We recommend that patients with a mood disorder taking multiple drugs should begin aripiprazole therapy with low doses and be monitored for the development of akathisia, increased anxiety, or suicidal thoughts. The appearance of these limiting side effects requires discontinuation of the drug.

Aripiprazole is the first antipsychotic drug of a group of new drugs with a peculiar pharmacodynamic profile. It is a dopamine D2 receptor partial agonist, as well as a 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist and a 5-HT2A receptor antagonist [1]. The partial agonistic effect of aripiprazole on 5-HT1A receptors may be associated with improvements in anxiety, depression, and negative symptoms and a reduction in extrapyramidal symptoms [2]. Aripiprazole is widely used to treat patients with bipolar disorder and is indicated for the treatment of depressive symptoms and as a mood stabilizer, with the advantage of having no negative effect on patients' metabolic profile. Aripiprazole is approved in the US and in Europe for the treatment of the acute manic and mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder. Clinical trials have shown aripiprazole to be clinically effective in terms of response and remission rates and in preventing relapses both when used for managing acute mania and as a long-term maintenance treatment. The lack of any sedative effect does not affect the efficacy of aripiprazole in controlling mania and restlessness [3]. Aripiprazole monotherapy resulted in some improvements in core depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar I disorder who had more severe depression; however, the difference in relation to the placebo group was not statistically significant [4]. Adjunctive aripiprazole treatment in patients with depression and a history of an inadequate response to antidepressants was associated with a reduced suicidality rate in a group of subjects at no significant risk [5]. The association of aripiprazole for depressive patients with anxiety or atypical characteristics resulted in a statistically significant improvement in depressive symptoms compared to placebo, the adverse effects being comparable in the patients with anxious and nonanxious depression and with typical and atypical depression.

Clinical trials have shown aripiprazole to be clinically effective in terms of response and remission rates and in preventing relapses both when used for managing acute mania and as a long-term maintenance treatment. The lack of any sedative effect does not affect the efficacy of aripiprazole in controlling mania and restlessness [3]. Aripiprazole monotherapy resulted in some improvements in core depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar I disorder who had more severe depression; however, the difference in relation to the placebo group was not statistically significant [4]. Adjunctive aripiprazole treatment in patients with depression and a history of an inadequate response to antidepressants was associated with a reduced suicidality rate in a group of subjects at no significant risk [5]. The association of aripiprazole for depressive patients with anxiety or atypical characteristics resulted in a statistically significant improvement in depressive symptoms compared to placebo, the adverse effects being comparable in the patients with anxious and nonanxious depression and with typical and atypical depression. The rates of akathisia and weight gain in patients on aripiprazole treatment did not differ between subgroups, leading Trivedi et al. to conclude that adjunctive aripiprazole is an effective treatment for patients with major depression presenting with either anxiety or atypical features [6].

The rates of akathisia and weight gain in patients on aripiprazole treatment did not differ between subgroups, leading Trivedi et al. to conclude that adjunctive aripiprazole is an effective treatment for patients with major depression presenting with either anxiety or atypical features [6].

Akathisia is a known side effect of aripiprazole that worsens when the drug is associated with lamotrigine or antidepressants. Akathisia is the most common of all the extrapyramidal side effects in the population using antipsychotics [7]. It consists of a subjective feeling of restlessness or nervousness, a need to move about, and an inability to relax that may be accompanied by signs of restlessness such as leg swinging while sitting, rocking from foot to foot, or swaying back and forth [7]. Symptoms generally appear 5–10 days after initiating use of a traditional antipsychotic drug or after an increase in its dose [7]. The prevalence of akathisia was 18% in patients with bipolar I disorder using aripiprazole and led to discontinuation of the drug in 2. 3% of patients, which was greater than the discontinuation rate for akathisia in a group of patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (1.2%) [8]. A study conducted to test the combination of lamotrigine and aripiprazole for patients with bipolar I disorder reported akathisia to be the most common side effect, with a prevalence of 10.8% in the group using aripiprazole and lamotrigine compared to 6.1% in the lamotrigine and placebo group [9]. A good response has been found with the association of low doses of aripiprazole (a mean of 4.2 mg/day) with antidepressants for treatment-resistant depression, with a prevalence of akathisia of around 22% [10].

3% of patients, which was greater than the discontinuation rate for akathisia in a group of patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (1.2%) [8]. A study conducted to test the combination of lamotrigine and aripiprazole for patients with bipolar I disorder reported akathisia to be the most common side effect, with a prevalence of 10.8% in the group using aripiprazole and lamotrigine compared to 6.1% in the lamotrigine and placebo group [9]. A good response has been found with the association of low doses of aripiprazole (a mean of 4.2 mg/day) with antidepressants for treatment-resistant depression, with a prevalence of akathisia of around 22% [10].

Recent case reports have suggested that akathisia constitutes a limiting factor to the use of aripiprazole. Saddichha et al. reported a case in which the use of aripiprazole was associated with acute dystonia, akathisia, and parkinsonism in a single patient [11]. Primeau et al. reported serotonin toxicity in aripiprazole augmentation, highlighting the risk of combining aripiprazole with antidepressants [12]. One case report described the development of aripiprazole-induced agitation following discontinuation of clozapine [13], while another reported aripiprazole-associated bruxism, akathisia, and parkinsonism in a bipolar patient [14]. Chem and Liou reported acute aripiprazole-associated dystonia, akathisia, and parkinsonism in a patient with bipolar I disorder [10].

One case report described the development of aripiprazole-induced agitation following discontinuation of clozapine [13], while another reported aripiprazole-associated bruxism, akathisia, and parkinsonism in a bipolar patient [14]. Chem and Liou reported acute aripiprazole-associated dystonia, akathisia, and parkinsonism in a patient with bipolar I disorder [10].

JSM, a 29-year-old female business manager, was extremely reserved and shy as a child living in a difficult family environment with a verbally abusive father. At 19 years of age she began analysis to cope with the stress of studying for her university entrance exams. At 21, she was prescribed fluvoxamine because of prominent obsessive symptoms. These symptoms disappeared, and she felt well, cheerful, and more energetic than usual for around 10 days. However, two months later she attempted suicide by taking benzodiazepines because of extreme anguish. Her family reported that at that time the patient had been very irritable, verbally abusive, and complaining of anguish that led her to suicidal thoughts and some suicide attempts. At 23, her progress at university was mediocre since she was unable to concentrate and would spend an entire week lying in bed, haunted with suicidal thoughts. In addition, since adolescence she has had dissociative seizures during which she cries a lot, shouts, contorts her hands and feet, and is unable to walk. At 26, after the end of a relationship, she became extremely apathetic and prostrate and had suicidal thoughts for about two months. She initiated use of venlafaxine but there was no significant improvement. The dissociative seizures intensified. Suspecting epilepsy, a neurologist prescribed lamotrigine. Nevertheless, an electroencephalogram (EEG) and video EEG monitoring failed to confirm the diagnosis of epilepsy. Symptoms of psychosis developed and her depression deepened. The antidepressant was switched to duloxetine (60 mg), which was then combined with mirtazapine (30 mg), and the dose of lamotrigine was increased to 400 mg/day. The psychotic symptoms worsened and she began to have suicidal thoughts and to self-mutilate.

At 23, her progress at university was mediocre since she was unable to concentrate and would spend an entire week lying in bed, haunted with suicidal thoughts. In addition, since adolescence she has had dissociative seizures during which she cries a lot, shouts, contorts her hands and feet, and is unable to walk. At 26, after the end of a relationship, she became extremely apathetic and prostrate and had suicidal thoughts for about two months. She initiated use of venlafaxine but there was no significant improvement. The dissociative seizures intensified. Suspecting epilepsy, a neurologist prescribed lamotrigine. Nevertheless, an electroencephalogram (EEG) and video EEG monitoring failed to confirm the diagnosis of epilepsy. Symptoms of psychosis developed and her depression deepened. The antidepressant was switched to duloxetine (60 mg), which was then combined with mirtazapine (30 mg), and the dose of lamotrigine was increased to 400 mg/day. The psychotic symptoms worsened and she began to have suicidal thoughts and to self-mutilate. Aripiprazole (5 mg) was added but there was no improvement; instead the symptoms of psychosis, anxiety, insomnia, and anguish worsened and akathisia developed. After about 20 days, the dose of the drug was adjusted to 10 mg; however, the aforementioned symptoms worsened and the psychotic experiences intensified. The dose was then increased to 15 mg and the patient was now no longer able to keep still for more than five minutes at a time. She continued to self-mutilate, the suicidal thoughts intensified, and she attempted defenestration. The symptoms began to improve gradually when all the medication was stopped and clozapine was introduced. Clozapine was gradually increased up to a maximum dose of 125 mg/day and resulted in remission of the acute symptoms after 15 days. The patient has remained stable for around 20 months, with relapses of mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms for periods of 10 days or less. The diagnostic hypothesis in the case of this patient is recurrent depression or type II bipolar disorder in view of the suspected episode of hypomania at the age of 21 years.

Aripiprazole (5 mg) was added but there was no improvement; instead the symptoms of psychosis, anxiety, insomnia, and anguish worsened and akathisia developed. After about 20 days, the dose of the drug was adjusted to 10 mg; however, the aforementioned symptoms worsened and the psychotic experiences intensified. The dose was then increased to 15 mg and the patient was now no longer able to keep still for more than five minutes at a time. She continued to self-mutilate, the suicidal thoughts intensified, and she attempted defenestration. The symptoms began to improve gradually when all the medication was stopped and clozapine was introduced. Clozapine was gradually increased up to a maximum dose of 125 mg/day and resulted in remission of the acute symptoms after 15 days. The patient has remained stable for around 20 months, with relapses of mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms for periods of 10 days or less. The diagnostic hypothesis in the case of this patient is recurrent depression or type II bipolar disorder in view of the suspected episode of hypomania at the age of 21 years.

OLP, a 56-year-old male fashion designer, had a very unhappy childhood, with few friends and many arguments at home. At university, he underwent a substantial change, becoming extroverted, making a lot of friends, and travelling extensively. As a professional, he was very creative, had many friends, and enjoyed going out. His father, an alcoholic who was extremely verbally abusive, committed suicide at 60 years of age. A nephew was diagnosed with depression. About 13 years ago, OLP began to isolate himself from his friends and to become very nervous whenever he was with a lot of people. He had difficulty concentrating, lost his enthusiasm for work and his creativity, and seemed to have lost his love for life. During that same period, he felt irritated and was bothered by noise, often getting into arguments with his neighbors for that reason. At work, he would also argue with colleagues, becoming angry easily and later regretting his outbursts. Since that time he has been undergoing psychotherapy and for the past eight years has undergone psychiatric treatment. He has used venlafaxine, mirtazapine, these two drugs together, and bupropion; however, there has been no remission of the depressive symptoms. After two months on bupropion (300 mg/day) and lamotrigine (100 mg/day) without any satisfactory improvement, aripiprazole (10 mg/day) was added. After five days of this combination, he developed major psychomotor agitation, accompanied by increased anxiety and restlessness, and akathisia that did not allow him to sit still for even three minutes at a time. He was sleepless at night even when taking 120 mg of flurazepam and complained of marked tiredness and muscle pain. In addition, his suicidal thoughts intensified and he experienced extreme anguish. He was given 50 mg of clozapine and all the other drugs were discontinued. After 10 days there was a significant improvement in his sleeping, allowing him to return to work. In addition, his psychomotor agitation decreased and there was a partial improvement in his feelings of anguish. Nevertheless, depressive symptoms remained: negative thoughts, extreme apathy, indisposition, and poor concentration.

He has used venlafaxine, mirtazapine, these two drugs together, and bupropion; however, there has been no remission of the depressive symptoms. After two months on bupropion (300 mg/day) and lamotrigine (100 mg/day) without any satisfactory improvement, aripiprazole (10 mg/day) was added. After five days of this combination, he developed major psychomotor agitation, accompanied by increased anxiety and restlessness, and akathisia that did not allow him to sit still for even three minutes at a time. He was sleepless at night even when taking 120 mg of flurazepam and complained of marked tiredness and muscle pain. In addition, his suicidal thoughts intensified and he experienced extreme anguish. He was given 50 mg of clozapine and all the other drugs were discontinued. After 10 days there was a significant improvement in his sleeping, allowing him to return to work. In addition, his psychomotor agitation decreased and there was a partial improvement in his feelings of anguish. Nevertheless, depressive symptoms remained: negative thoughts, extreme apathy, indisposition, and poor concentration. He was prescribed imipramine 150 mg and lithium 450 mg. He remained stable, with mild depressive symptoms after nine months. In the case of this patient, there is no clear evidence of hypomanic episodes; however, there is a report of unusual moods during his time at university. Since there are no relatives available to provide further details, the suspected diagnosis is dysthymia and double depression or type II bipolar disorder.

He was prescribed imipramine 150 mg and lithium 450 mg. He remained stable, with mild depressive symptoms after nine months. In the case of this patient, there is no clear evidence of hypomanic episodes; however, there is a report of unusual moods during his time at university. Since there are no relatives available to provide further details, the suspected diagnosis is dysthymia and double depression or type II bipolar disorder.

Aripiprazole is a drug approved for use in mania and as a maintenance therapy for the management of bipolar mood disorder. Studies have shown the drug to be useful for the treatment of depression when combined with antidepressants; however, cases have been described in the literature in which significant akathisia developed. In the two cases described here, aripiprazole was associated with lamotrigine and other antidepressants. In the first case, the patient was taking a high dose of lamotrigine (400 mg), while the second patient was using a low dose (100 mg). The prevalence of akathisia in patients with bipolar mood disorder in use of aripiprazole is high, and association of aripiprazole with lamotrigine appears to increase the prevalence of akathisia [8, 9]. In the clinical cases reported here both patients were in use of aripiprazole in combination with lamotrigine and antidepressants, in one case duloxetine and mirtazapine and in the other bupropion. The incidence of akathisia reported in patients with treatment-resistant depression using antidepressants and aripiprazole, even at a low dose, was high [15]. The combination of aripiprazole, the antipsychotic most associated with akathisia, with lamotrigine and antidepressants may have increased the risk of akathisia, thus resulting in the clinical conditions observed in these two cases.

The prevalence of akathisia in patients with bipolar mood disorder in use of aripiprazole is high, and association of aripiprazole with lamotrigine appears to increase the prevalence of akathisia [8, 9]. In the clinical cases reported here both patients were in use of aripiprazole in combination with lamotrigine and antidepressants, in one case duloxetine and mirtazapine and in the other bupropion. The incidence of akathisia reported in patients with treatment-resistant depression using antidepressants and aripiprazole, even at a low dose, was high [15]. The combination of aripiprazole, the antipsychotic most associated with akathisia, with lamotrigine and antidepressants may have increased the risk of akathisia, thus resulting in the clinical conditions observed in these two cases.

In addition to akathisia, the patients reported a significant worsening of anxiety and the onset of suicidal thoughts, with one attempting defenestration when the dose of aripiprazole was increased to 15 mg. There have been three case reports of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts after patients began using aripiprazole [16–18]. There have also been reports of worsening positive symptoms and disinhibition [19]. With respect to anxiety, we were unable to find any reference to aripiprazole worsening or provoking symptoms of anxiety. The sensation of restlessness and lack of motor control generated by akathisia may alone account for the increased subjective feeling of anxiety. However, in the cases described in this report, anxiety may be associated with deterioration in the patient's general clinical status or may even be one more side effect of the pharmacological association.

There have been three case reports of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts after patients began using aripiprazole [16–18]. There have also been reports of worsening positive symptoms and disinhibition [19]. With respect to anxiety, we were unable to find any reference to aripiprazole worsening or provoking symptoms of anxiety. The sensation of restlessness and lack of motor control generated by akathisia may alone account for the increased subjective feeling of anxiety. However, in the cases described in this report, anxiety may be associated with deterioration in the patient's general clinical status or may even be one more side effect of the pharmacological association.

Although double-blind controlled studies have been conducted on the use of aripiprazole for the treatment of patients with mood disorder, it may be prudent to exercise caution when prescribing this drug for use in that particular population. Monitoring for the onset of akathisia, increased anxiety, and suicidal thoughts is relevant, particularly in those patients taking multiple drugs.

In daily practice, physicians must decide how to best manage the treatment of individual cases, which may differ from those encountered in clinical trial settings. When using aripiprazole to treat a patient with mood disorder, adding lamotrigine could be risky. If unavoidable, patients should be closely monitored for the possible development of akathisia, agitation, unbearable anguish and, most importantly, suicidality.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

1. Jordan S., Koprivica V., Dunn R., Tottori K., Kikuchi T., Altar C. A. In vivo effects of aripiprazole on cortical and striatal dopaminergic and serotonergic function. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2004;483(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.10.025. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Winans E. Aripiprazole. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2003;60:2437–2445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. De Fazio P., Girardi P. , Maina G., et al. Aripiprazole in acute mania and long-term treatment of bipolar disorder: a critical review by an Italian working group. Clinical Drug Investigation. 2010;30(12):827–841. doi: 10.2165/11584270-000000000-00000. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Maina G., et al. Aripiprazole in acute mania and long-term treatment of bipolar disorder: a critical review by an Italian working group. Clinical Drug Investigation. 2010;30(12):827–841. doi: 10.2165/11584270-000000000-00000. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Thase M. E., Bowden C. L., Nashat M., et al. Aripiprazole in bipolar depression: a pooled, post-hoc analysis by severity of core depressive symptoms. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2012;16(2):121–131. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2011.632680. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Weisler R. H., Khan A., Trivedi M. H., et al. Analysis of suicidality in pooled data from 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled aripiprazole adjunctive therapy trials in major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2011;72(4):548–555. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05495gre. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Trivedi M. H., Thase M. E., Fava M., et al. Adjunctive aripiprazole in major depressive disorder: analysis of efficacy and safety in patients with anxious and atypical features. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1928–1936. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1211. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1928–1936. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1211. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Dag E., Gokce B., Buturak S. V., Tiryaki D., Erdemoglu A. K. Pregabalin-Induced Akathisia. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2013;47(4):592–593. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R699. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Kane J. M., Barnes T. R., Correll C. U., et al. Evaluation of akathisia in patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar i disorder: a post hoc analysis of pooled data from short- and long-term aripiprazole trials. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2010;24(7):1019–1029. doi: 10.1177/0269881109348157. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Carlson B. X., Ketter T. A., Sun W., et al. Aripiprazole in combination with lamotrigine for the long-term treatment of patients with bipolar I disorder (manic or mixed): a randomized, multicenter, double-blind study (CN138-392) Bipolar Disorders. 2012;14(1):41–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00974.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00974.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Chen M.-H., Liou Y.-J. Aripiprazole-associated acute dystonia, akathisia, and parkinsonism in a patient with bipolar i disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2013;33(2):269–270. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e3182856826. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Saddichha S., Kumar R., Babu G. N., Chandra P. Aripiprazole associated with acute dystonia, akathisia, and parkinsonism in a single patient. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2012;52(9):1448–1449. doi: 10.1177/0091270011414573. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Primeau M., Pomeraniec F., Wallace D. M. Serotonin toxicity in aripiprazole augmentation. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2012;24(1):E36–E37. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11020051. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Cho D. Y., Lindenmayer J.-P. Aripiprazole-induced agitation after clozapine discontinuation: a case report. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70(1):141–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70(1):141–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Caykoylu A., Ekinci O., Ugurlu G. K., Albayrak Y. Aripiprazole-associated bruxism, akathisia, and parkinsonism in a bipolar patient. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2011;31(1):134–135. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182048cce. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Chen S.-J., Hsiao Y.-L., Shen T.-W., Chen S.-T. The effectiveness and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole in taiwanese patients with antidepressant-refractory major depressive disorder: a prospective, open-label trial. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2012;32(1):56–60. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e31823f6c7f. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Beers E., Loonen A. J. M., Van Grootheest A. C. Suicidal ideations and suicide attempts after starting on aripiprazole, a new antipsychotic drug. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. 2006;150(7):401–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Slooff C. J., Arends J. Suicidal ideations and suicide attempts after starting on aripiprazole, a new antipsychotic drug. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. 2006;150(7):400–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J., Arends J. Suicidal ideations and suicide attempts after starting on aripiprazole, a new antipsychotic drug. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. 2006;150(7):400–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Scholten M. R. M., Selten J. P. Suicidal ideations and suicide attempts after starting with aripiprazole, a new antipsychotic drug. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. 2005;149(41):2296–2298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Pondé M. P., Novaes C. M. Aripiprazole worsening positive symptoms and memantine reducing negative symptoms in a patient with paranoid schizophrenia. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 2007;29(1) doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462007000100028. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

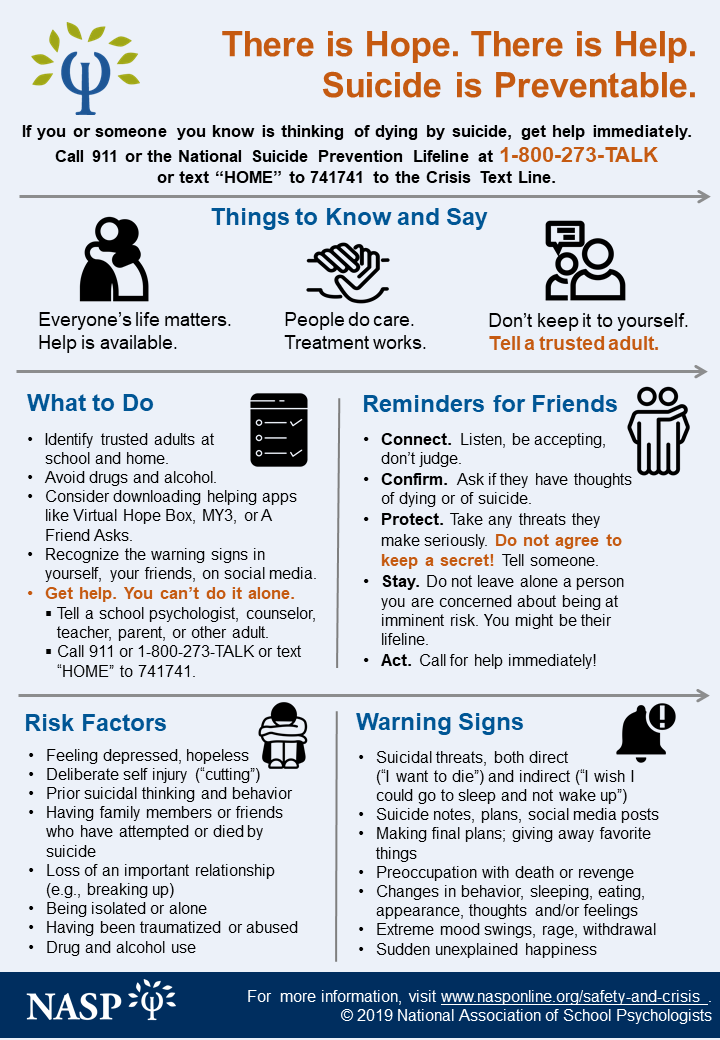

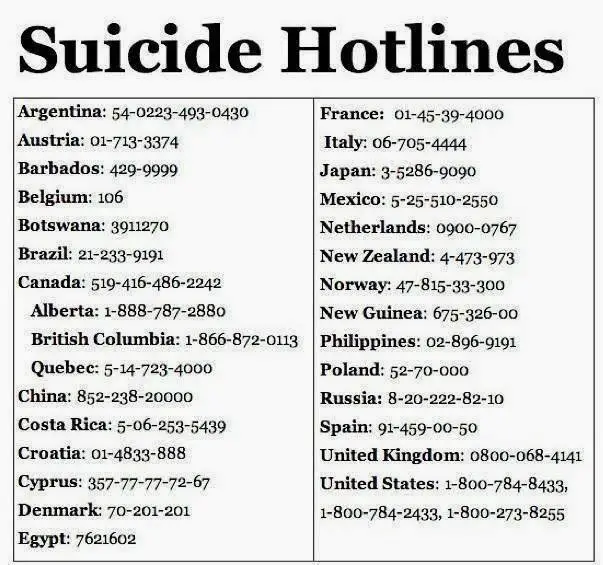

Get help & support for suicide

If you’re in emotional distress or suicidal crisis, find help in your area with Find a helpline.

If you believe that someone else is in danger of suicide and you have their contact information, contact your local law enforcement for immediate help. You can also encourage the person to contact a suicide prevention hotline using the information above.

You can also encourage the person to contact a suicide prevention hotline using the information above.

Learn more about personal crisis information with Google Search.

Google’s crisis information comes from high-quality websites, partnerships, medical professionals, and search results.

Important: Partnerships vary by country and region.

| Country | Hotline organization | Website | Phone number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Centro de Asistencia al Suicida | www.asistenciaalsuicida.org | (011) 5275-1135 |

| Australia | Lifeline Australia | www.lifeline.org | 13 11 14 |

| Austria | Telefon Seelsorge Osterreich | www. telefonseelsorge.at telefonseelsorge.at | 142 |

| Belgium | Center de Prevention du Suicide | www.preventionsuicide.be | 0800 32 123 |

| Belgium | CHS Helpline | www.chsbelgium.org | 02 648 40 14 |

| Belgium | Zelfmoord 1813 | www.zelfmoord1813.be | 1813 |

| Brazil | Centro de Valorização da Vida | www.cvv.org | 188 |

| Canada | Crisis Services Canada | crisisservicescanada.ca | 833-456-4566 |

| Chile | Ministry of Health of Chile | www.hospitaldigital.gob | 6003607777 |

| China | Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center | www. crisis.org crisis.org | 800-810-1117 |

| Costa Rica | Colegio de Profesionales en Psicologia de Costa Rica | psicologiacr.com/aqui-estoy | 2272-3774 |

| France | SOS Amitié | www.sos-amitie.org | 09 72 39 40 50 |

| Germany | Telefon Seelsorge Deutschland | www.telefonseelsorge.de | 0800 1110111 |

| Hong Kong | Suicide Prevention Services | www.sps.org | 2382 0000 |

| India | iCall Helpline | icallhelpline.org | 9152987821 |

| Ireland | Samaritans Ireland | www.samaritans.org/how-we-can-help | 116 123 |

| Israel | [Eran] ער"ן | www. eran.org eran.org | 1201 |

| Italy | Samaritans Onlus | www.samaritansonlus.org | 06 77208977 |

| Japan | Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology | www.mext.go.jp | 81-0120-0-78310 |

| Japan | Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan | www.mhlw.go | 0570-064-556 |

| Malaysia | Befrienders KL | www.befrienders.org | 03-76272929 |

| Netherlands | 113Online | www.113.nl | 0800-0113 |

| New Zealand | Lifeline Aotearoa Incorporated | www.lifeline.org | 0800 543 354 |

| Norway | Mental Helse | mentalhelse. no no | 116 123 |

| Pakistan | Umang Pakistan | www.umang.com.pk/ | 0311-7786264 |

| Peru | Linea 113 Salud | www.gob.pe/555-recibir-informacion-y-orientacion-en-salud | 113 |

| Philippines | Department of Health - Republic of the Philippines | doh.gov.ph/NCMH-Crisis-Hotline | 0966-351-4518 |

| Portugal | SOS Voz Amiga | www.sosvozamiga.org | 213 544 545 963 524 660 912 802 669 |

| Russia | Fund to Support Children in Difficult Life Situations | www.ya-parent.ru | 8-800-2000-122 |

| Singapore | Samaritans of Singapore | www. sos.org sos.org | 1-767 |

| South Africa | South African Depression and Anxiety Group | www.sadag.org | 0800 567 567 |

| South Korea | Korea Suicide Prevention Center중앙자살예방센터 | www.spckorea.or | 1393 |

| Spain | Telefono de la Esperanza | www.telefonodelaesperanza.org | 717 003 717 |

| Switzerland | Die Dargebotene Hand | www.143.ch | 143 |

| Taiwan | 国际生命线台湾总会 [International Lifeline Taiwan Association] | www.life1995.org | 1995 |

| Ukraine | Lifeline Ukraine | lifelineukraine.com | 7333 |

| United Kingdom | Samaritans | www. samaritans.org/how-we-can-help samaritans.org/how-we-can-help | 116 123 |

| United States | 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline | 988lifeline.org | 988 |

How can we improve it?

Ask the Help Community

Get answers from community expertsTransfers

home

Parents

Helpline

Information about the unified all-Russian children’s helpline

0446 8-800-2000-122 .

When calling this number in any locality of the Russian Federation from fixed or mobile phones, children in difficult life situations, adolescents and their parents, other citizens can receive emergency psychological assistance, which is provided by specialists of services already operating in the constituent entities of the Russian Federation that provide services for telephone counseling and connected to a single all-Russian number of children's helpline.

Confidentiality and free of charge are the two main principles of the children's helpline. This means that every child and parent can anonymously and free of charge receive psychological assistance and the secrecy of his call to the helpline is guaranteed.

Working hours of the children's helpline in the constituent entities of the Russian Federation

(as of October 1, 2013)

| Name of the subject of the Russian Federation 9Arkhangelsk region 09.00-22.00 | |||

| 22 | with Nenets Autonomous Okrug | daily 09.00-17.30 | |

| 23 | Vologda region | around the clock | |

| 24 | Kaliningrad region | daily0039 | around the clock |

| 35 | Chechen Republic 08.30-20.00 | ||

| South Federal District | |||

| 37 | Republic of Adygea | ||

| Kalmykia | Pon-Pip. 8.00-17.00 8.00-17.00 | ||

| 3 | |||

| 80 | Magadan region | Pon.-Pon. 10.00.22.00 | |

| 81 | Sakhalin Region | ||

| 900 | |||

| 83 | Chukotka AO | Mon-Fri 09.00-22.00, closed 16.00-22.00 | |

Infographics. The principle of operation of a single federal helpline number for children, adolescents and their parents

Information from the regions about the work of the children's helpline

12/28/2016

What to do when there is a problem, but there is no one to tell about it?

12/28/2016

Online psychologists are ready to save children from bullying

12/28/2016

What problems do residents of the Irkutsk region call the helpline

09.1 for children1.2016

3

3

09.