Development of prosocial behavior in children

IBE — Science of learning portal — Development of prosocial behavior

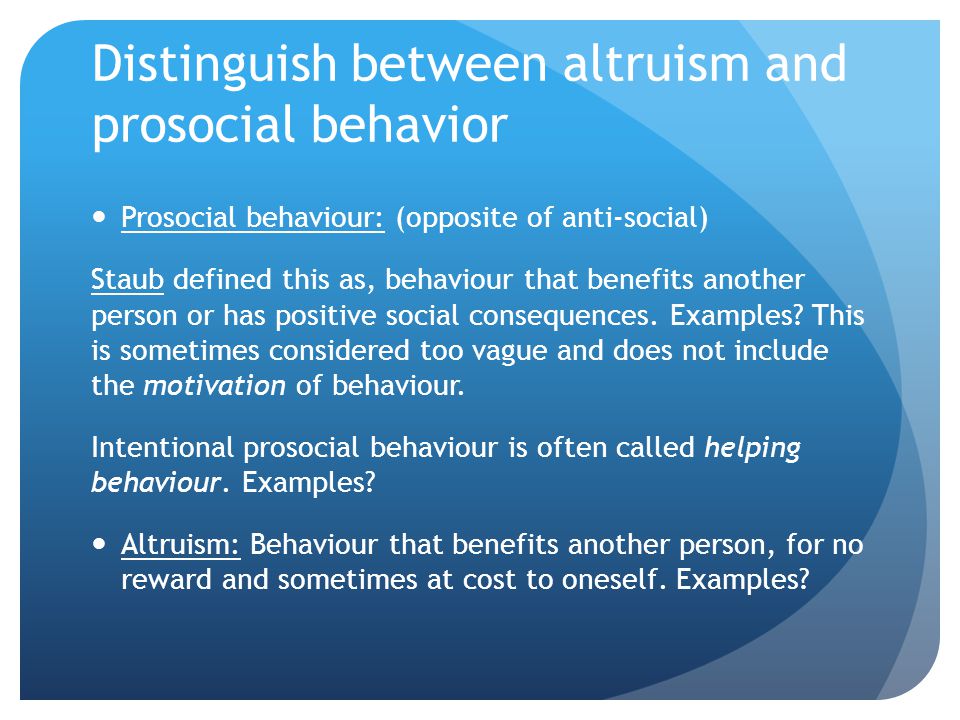

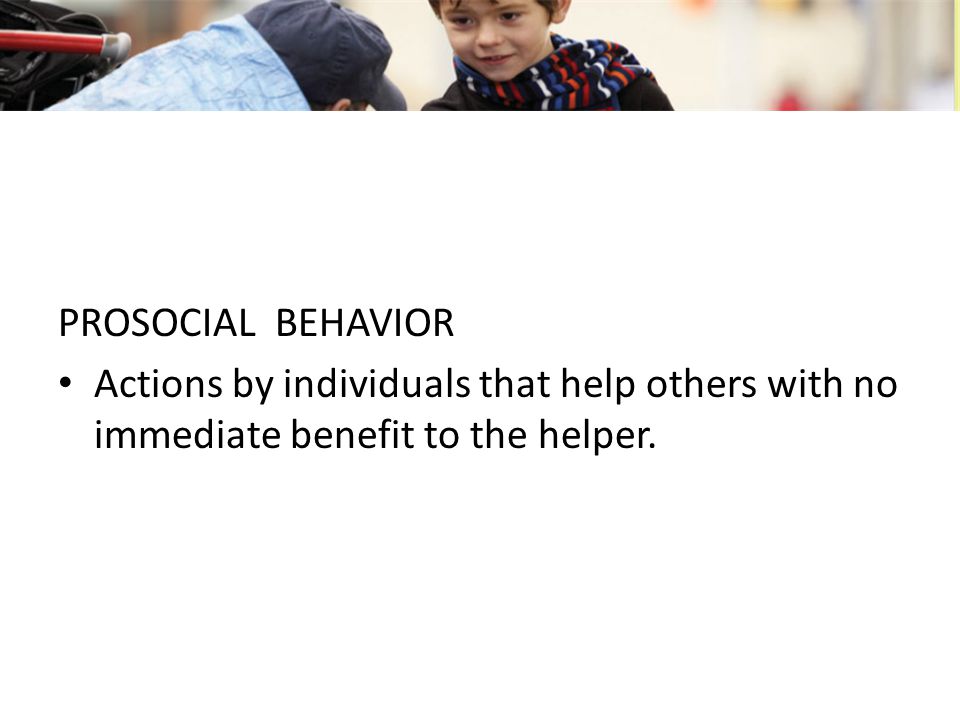

Prosocial behaviors are voluntary behaviors that are intended to benefit others, such as helping, sharing, caring, and comforting. They are a hallmark of social competence in children of all ages. Prosocial behaviors correlate with social adjustment in later life.

This report arises from Science of Learning Fellowships funded by the International Brain Research Organization (IBRO) in partnership with the International Bureau of Education (IBE) of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The IBRO/IBE-UNESCO Science of Learning Fellowship aims to support and translate key neuroscience research on learning and the brain to educators, policy makers, and governments.

Executive summary

- There are two main types of prosocial behavior which develop in infancy and gradually increase in early childhood: sharing and helping.

- Maturation of prefrontal cortical circuitry improves behavioral control and supports the development of sharing behavior during childhood, producing a shift from the immediate desires of reward maximization to complying with the social norms of sharing.

- Helping behavior emerges as early as 14 months and functional changes in brain development support the linkage between prosocial behaviors in early childhood and effortful control at a later age.

- Prosocial behavior and its psychological foundations are critical not only for the context of individual but also for social and global contexts. Therefore, a global preschool curriculum specifically designed to foster prosocial behavior is needed for preparing young children with competencies critical for the future.

Introduction

Prosocial behaviors are voluntary behaviors that are intended to benefit others, such as helping, sharing, caring, and comforting (Eisenberg & Mussen, 1989; N. Steinbeis, 2018). They are a hallmark of social competence in children of all ages. Prosocial behaviors correlate with social adjustment in later life (Jones, Greenberg, & Crowley, 2015). Importantly, prosocial behaviors and cooperative behaviors are conceptually associated (Eisenberg & Miller, 1987). There are two main types of prosocial behavior which develop in infancy and gradually increase in early childhood: sharing and helping (Dunfield, Kuhlmeier, O’Connell, & Kelley, 2011).

There are two main types of prosocial behavior which develop in infancy and gradually increase in early childhood: sharing and helping (Dunfield, Kuhlmeier, O’Connell, & Kelley, 2011).

Dunfield et al. (2011) suggests that prosocial behaviors are crucial for harmonious in-group relationships, cooperation, and working together to fulfill a goal (Eisenberg & Mussen, 1989). Therefore, fostering prosocial behaviors in young children may have long-term benefits not only for individual competencies but also for group harmony and a peaceful society.

Why is prosocial behavior important?

The 21st century demands people communicate and negotiate with others for novel solutions. Prosocial behaviors in young children are an essential foundation for future competencies such as collaboration, social cohesion, harmony, and peaceful society. Importantly, prosocial behaviors during childhood predict adaptive functioning at a later age. For example, highly aggressive children with low prosocial behaviors predict behavioral adjustment problems at a later age (Gresham, Elliott, & Kettler, 2010). Therefore, building and maintaining positive relationships with others is crucial for work and life success in the future. The neurocognitive basis of prosociality arises very early in young children and needs guidance from adults to enable strengthening of the neural circuits for helping and sharing which are crucial for future competencies.

Therefore, building and maintaining positive relationships with others is crucial for work and life success in the future. The neurocognitive basis of prosociality arises very early in young children and needs guidance from adults to enable strengthening of the neural circuits for helping and sharing which are crucial for future competencies.

A neural system for development of prosociality

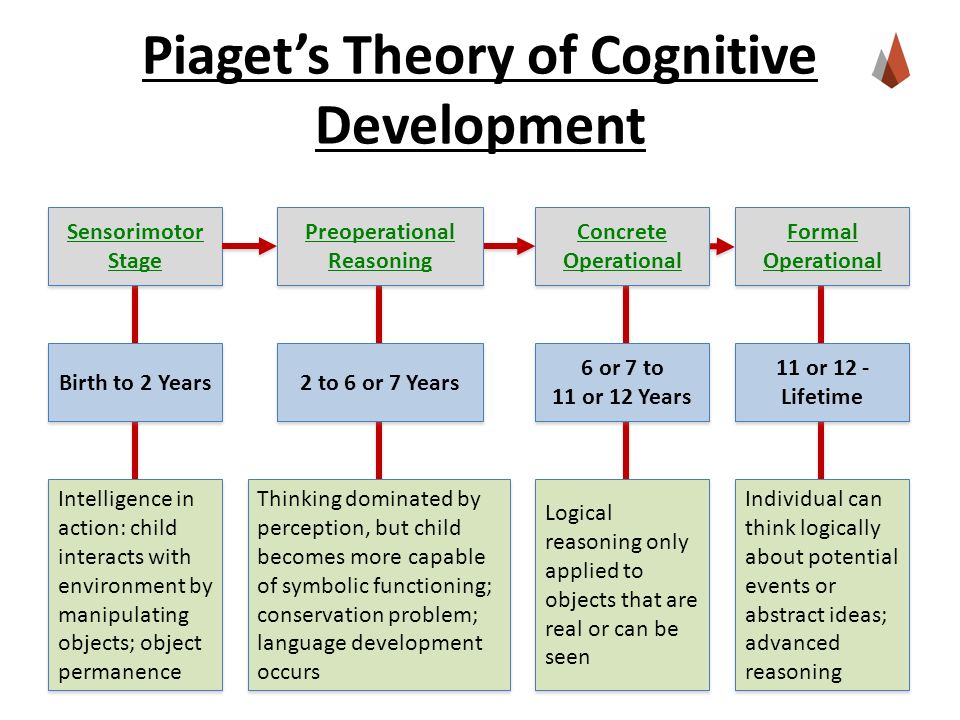

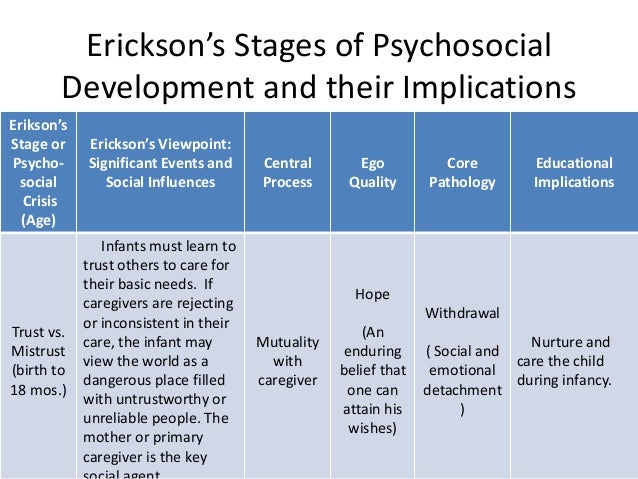

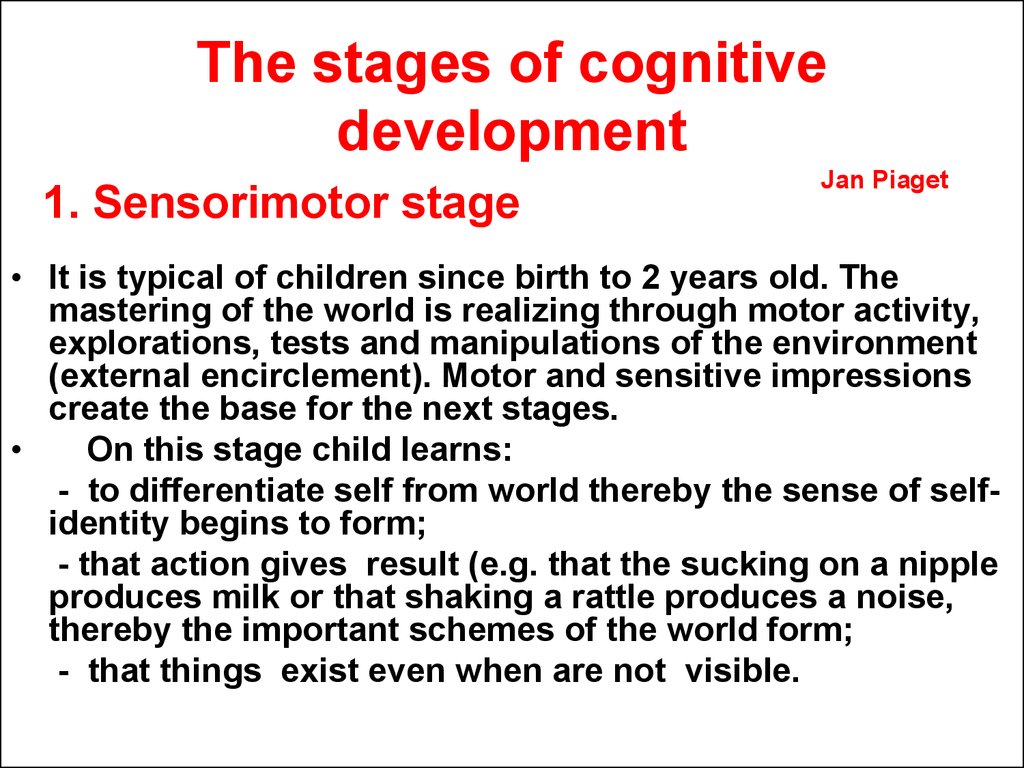

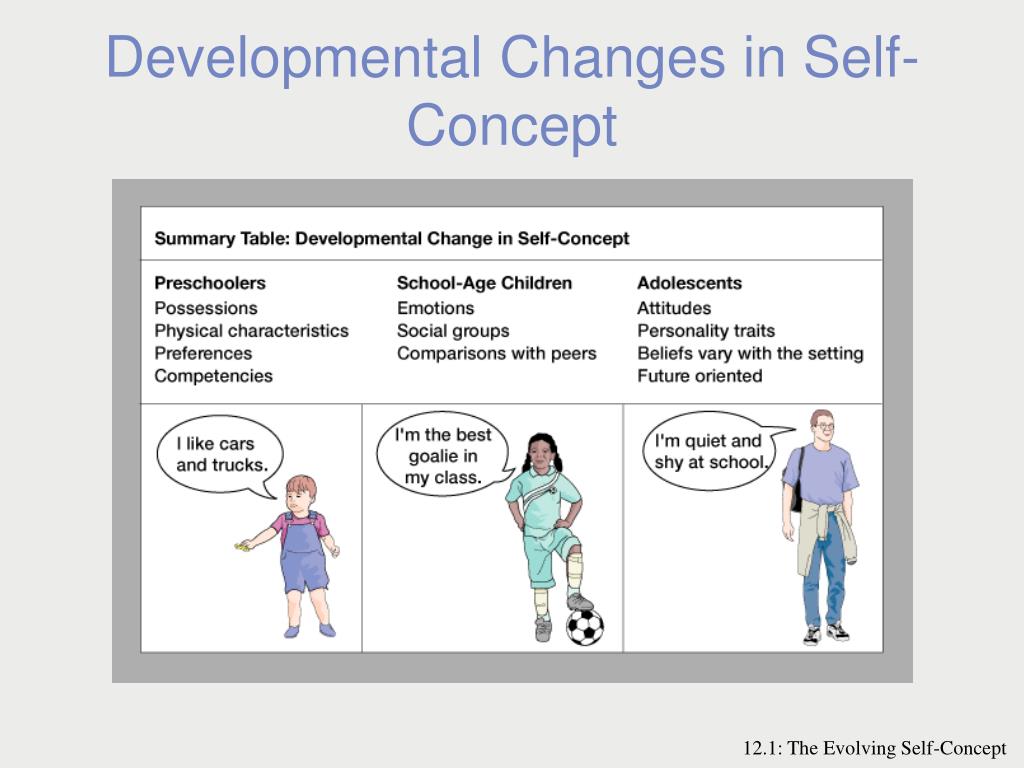

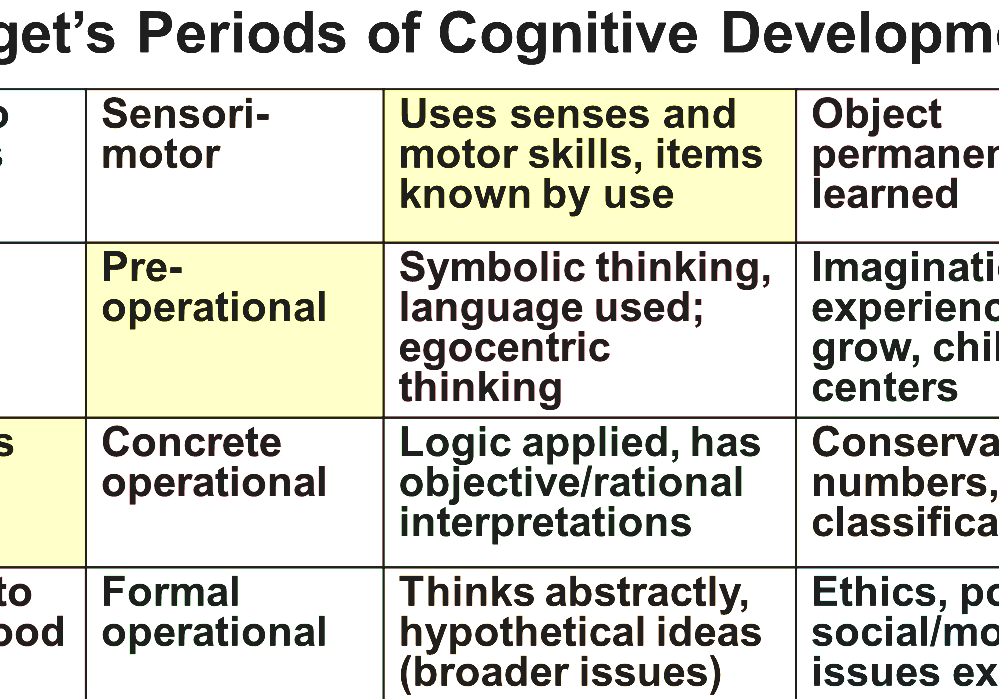

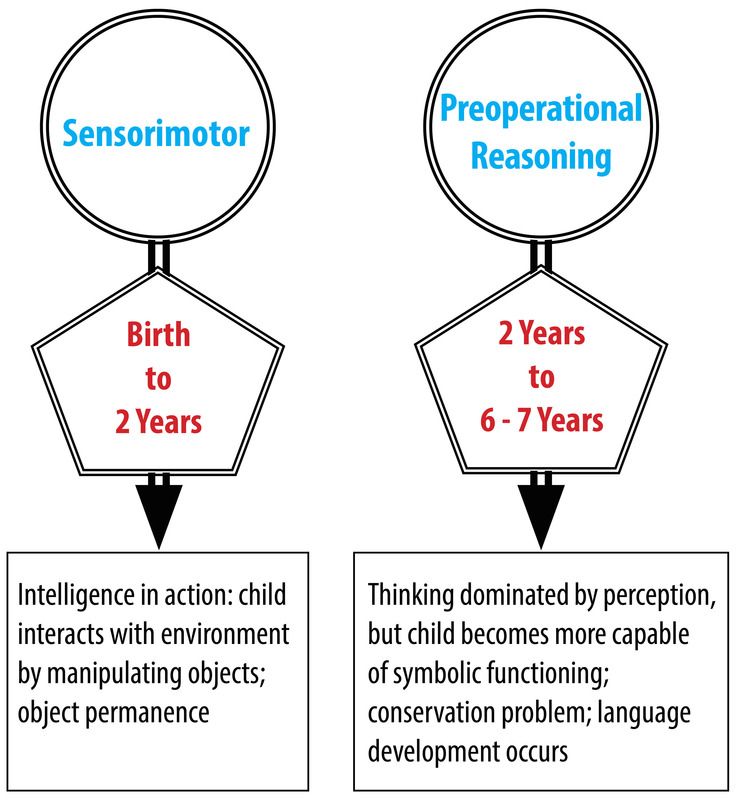

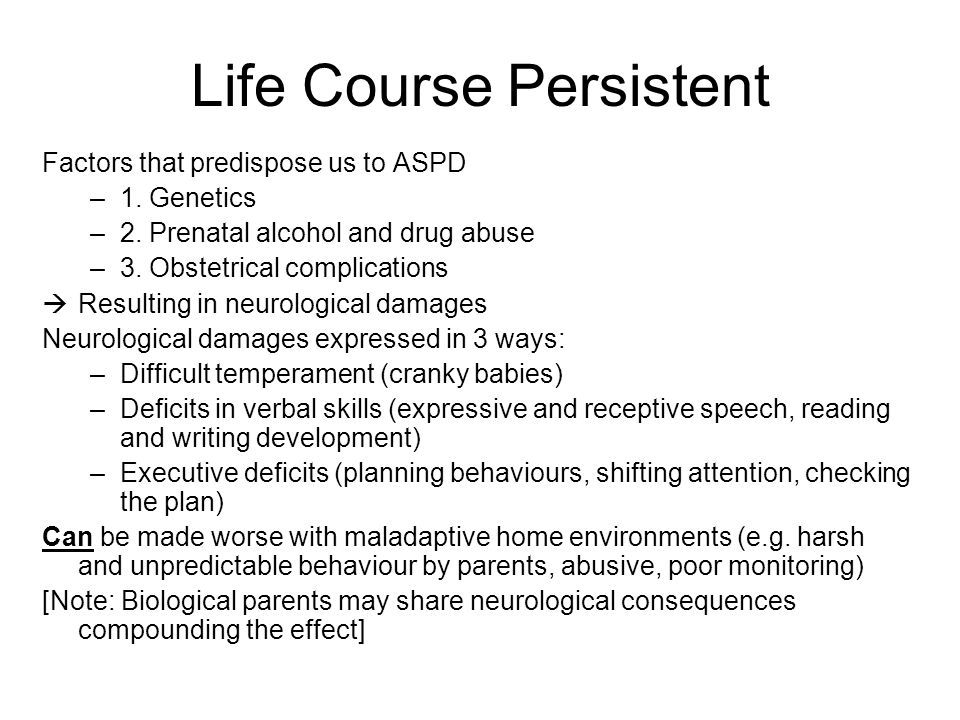

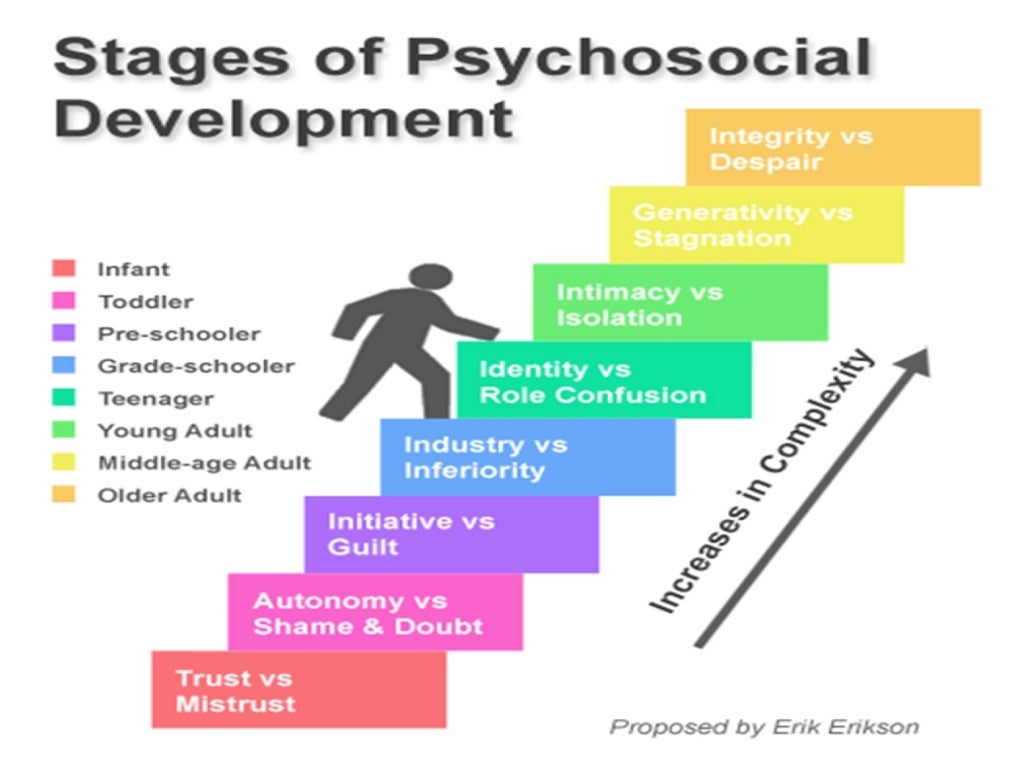

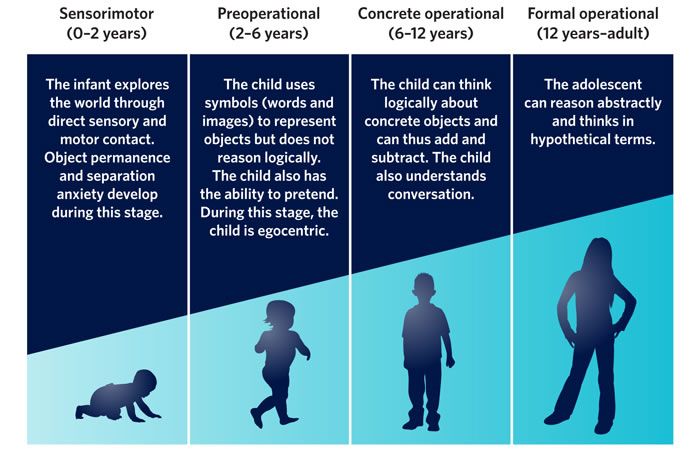

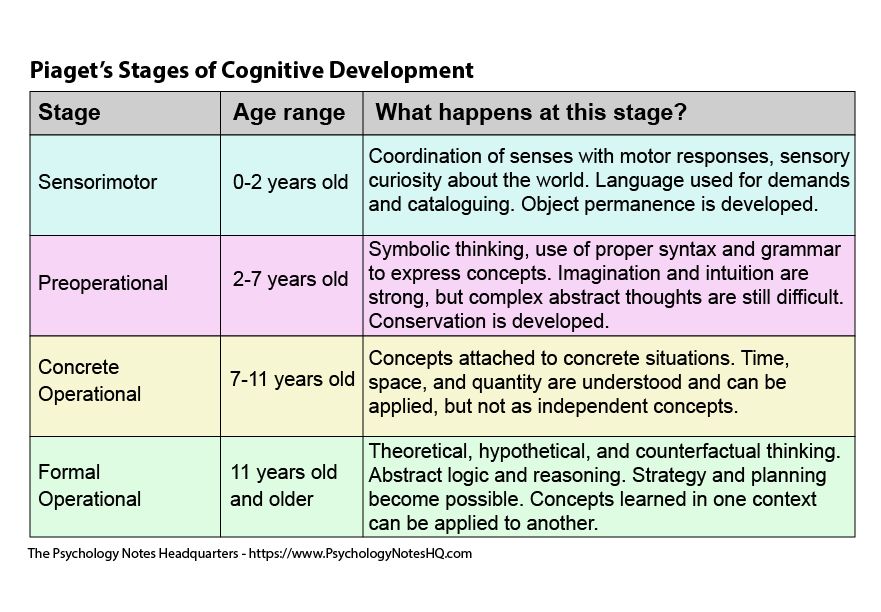

According to Piaget’s theory, preschool children exhibit egocentrism or inability to differentiate between their perspective and another’s (Piaget, 1954). Children at this stage are self-centered and have difficulty sharing with others. It has been proposed that sharing behavior in the first three years of life may not occur due to empathy but could be due to children’s tendency towards imitation and social play (Damon, Lerner, & Eisenberg, 2006). However, from the age of three, empathetic awareness and encouragement from an adult can enhance children’s helping and sharing behavior.

While some theories claim that prosocial behavior in young children is automatic and spontaneous, others propose it requires cognitive control (Eisenberg-Berg, Haake, Hand, & Sadalla, 1979; Svetlova, Nichols, & Brownell, 2010). The nature of sharing and helping can involve conflicts of interest—i.e., between what is best for oneself (egoism) and what is best for others (sociality). Performing prosocial behavior is not always easy—i.e., sharing means less for oneself while helping others can require time and effort. Therefore, cognitive control might be crucial for deciding to share or to help others. Steinbeis (2018) proposes that the prefrontal cortical circuitry plays an essential role in the decision to favor prosocial behavior. Also, advances in neuroscience research have shed light on the role of value-based decision-making in the development of prosocial behavior during childhood. For example, there is strong evidence that the maturation of prefrontal cortical circuitry supports the development of prosocial behavior during childhood and adolescence. In this view, the neural mechanisms underlying prosociality may undergo protracted development.

In this view, the neural mechanisms underlying prosociality may undergo protracted development.

Sharing

There are two brain areas involved in sharing behavior: the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), which plays a role in cognitive and behavioral control, and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), which plays a role in decision-making, self-control, and the cognitive evaluation of morality. It is likely that increased functional coupling between DLPFC and VMPFC helps to compute the value signal and to make a decision to share. Moreover, sharing is correlated with increased activity in the DLPFC (Spitzer, Fischbacher, Herrnberger, Grön, & Fehr, 2007) while disrupting activity in the DLPFC can reduce sharing behavior (Ruff, Ugazio, & Fehr, 2013). A recent study showed that sharing in children increased between the ages of 6–13 years and this correlated positively with activity in the left DLPFC and behavioral motor control (Steinbeis, Bernhardt, & Singer, 2012). In addition, there is evidence showing that behavioral inhibition is positively correlated with sharing in preschool and school-aged children (Aguilar-Pardo, Martínez-Arias, & Colmenares, 2013). In summary, maturation of function and connectivity of the prefrontal cortical circuitry improves behavioral control and supports the development of sharing behavior throughout childhood. DLPFC is also the key brain area that supports the decision to favor long-term goals in both children and adults (Steinbeis, Haushofer, Fehr, & Singer, 2014). Such a mechanism scaffolds the shift away from the immediate desires of reward maximization towards complying with the social norms of equal sharing.

In addition, there is evidence showing that behavioral inhibition is positively correlated with sharing in preschool and school-aged children (Aguilar-Pardo, Martínez-Arias, & Colmenares, 2013). In summary, maturation of function and connectivity of the prefrontal cortical circuitry improves behavioral control and supports the development of sharing behavior throughout childhood. DLPFC is also the key brain area that supports the decision to favor long-term goals in both children and adults (Steinbeis, Haushofer, Fehr, & Singer, 2014). Such a mechanism scaffolds the shift away from the immediate desires of reward maximization towards complying with the social norms of equal sharing.

Helping

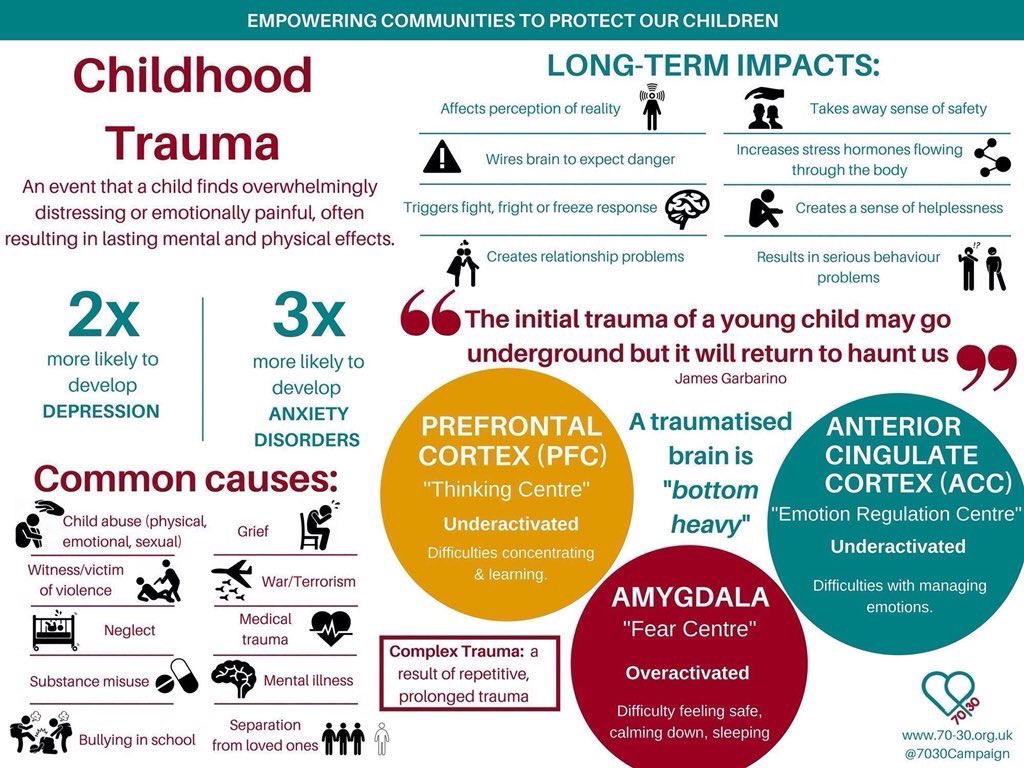

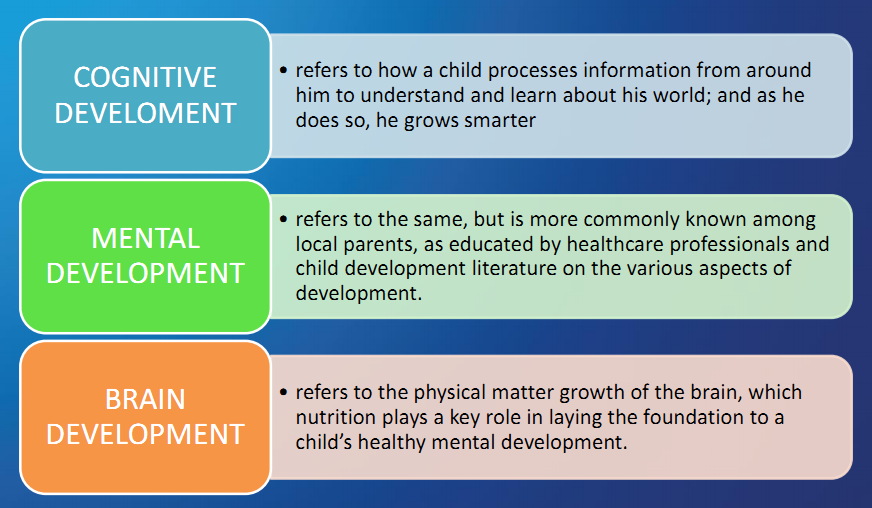

Helping behavior emerges as early as 14 months, suggesting that the brain circuitry for prosocial behavior begins to develop from early childhood (Warneken & Tomasello, 2007). Many skills can help scaffold helping behavior in young children. For example, children with higher emotional response and emotional regulation are more likely to help others than those with low emotional response and regulation. Another contributing skill is the empathic concern or the ability to understand another’s feeling (e.g., understand other’s feeling of pain) which can also predict helping behavior in young children. The brain areas that activate when we are observing someone feeling pain are the bilateral anterior insular cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (see Figure 1) (Lamm, Decety, & Singer, 2011). Increased activity in the anterior insular cortex positively correlates with empathic concern and helping behavior (Hein, Silani, Preuschoff, Batson, & Singer, 2010).

Another contributing skill is the empathic concern or the ability to understand another’s feeling (e.g., understand other’s feeling of pain) which can also predict helping behavior in young children. The brain areas that activate when we are observing someone feeling pain are the bilateral anterior insular cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (see Figure 1) (Lamm, Decety, & Singer, 2011). Increased activity in the anterior insular cortex positively correlates with empathic concern and helping behavior (Hein, Silani, Preuschoff, Batson, & Singer, 2010).

Moreover, the connectivity between the anterior insular cortex and the ACC correlates with prosocial behavior (Hare, Camerer, Knoepfle, Doherty, & Rangel, 2010). The ACC plays a role in the processing of emotional conflict that leads to empathic concern and later induces prosocial behaviors such as helping and sharing (Etkin, Egner, & Kalisch, 2011). Additionally, activation in the anterior insular cortex and the ACC correlating with empathic concern can be observed as early as four years old (Etkin, Egner, & Kalisch, 2011; Michalska, Kinzler, & Decety, 2013). Importantly, empathic concern at a young age predicts the activation of inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) at a later age (Decety & Michalska, 2010). The IFG is a brain area which plays a role in effortful control. Therefore, these lines of evidence provide linkage between prosocial behavior in early childhood and effortful control at a later age (Steinbeis, 2018).

Importantly, empathic concern at a young age predicts the activation of inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) at a later age (Decety & Michalska, 2010). The IFG is a brain area which plays a role in effortful control. Therefore, these lines of evidence provide linkage between prosocial behavior in early childhood and effortful control at a later age (Steinbeis, 2018).

What can be done?

Figure 1. Brain regions involved in prosocial behavior during childhood. (A) Lateral view showing anterior insula (red) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (purple). (B) Medial view showing anterior cingulate (red) and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (blue) (Steinbeis, 2018).

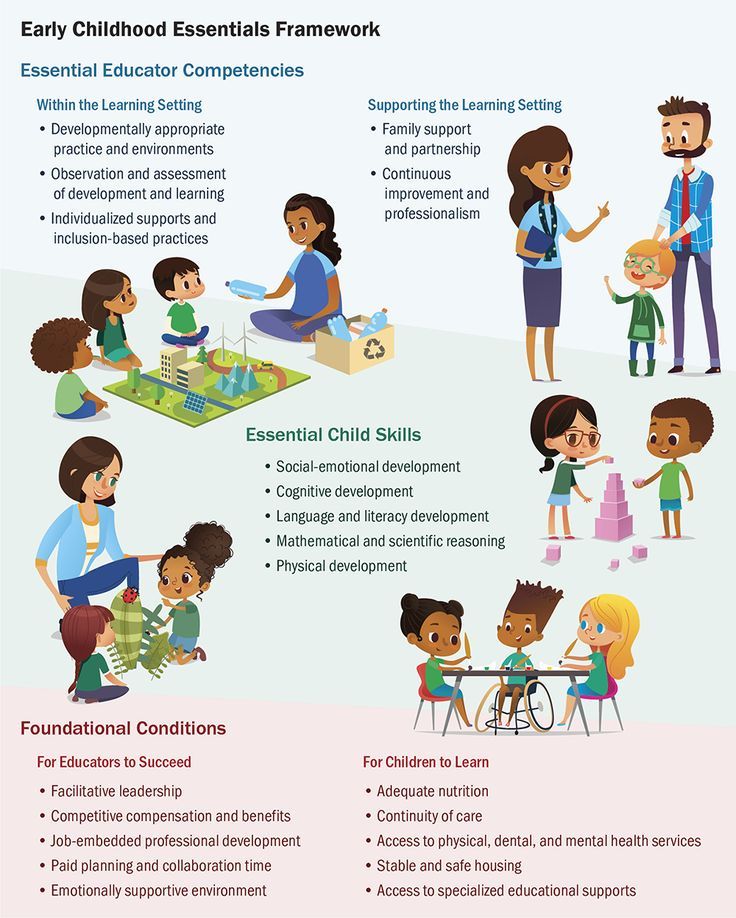

Social skills, such as emotion recognition, empathy, generosity, helping, and sharing with others, are critical competencies that enable an individual to build and maintain positive relationships and avoid negative interactions with others (Greesham and Elliott, 1990). These skills are increasingly being recognized as a critical foundation for school readiness and academic success, as well as for work and life success in the long term (Gresham, 2014; Kathryn, 2015; McClelland & Morrison, 2003). Research findings suggest that children internalize the prosocial and moral behaviors they observe from others. Thus, teachers and friends have the potential to promote the development of prosocial behavior in young children. Classroom environments that allow children to share and help each other, or work in groups, might also help scaffold prosocial skills in young children. In conclusion, prosocial skills and their psychological foundations are critical not only for the context of individual but also social and global contexts. Therefore, a global preschool curriculum specifically designed to foster prosocial behavior is needed for preparing young children with competencies that are critical for their future.

Research findings suggest that children internalize the prosocial and moral behaviors they observe from others. Thus, teachers and friends have the potential to promote the development of prosocial behavior in young children. Classroom environments that allow children to share and help each other, or work in groups, might also help scaffold prosocial skills in young children. In conclusion, prosocial skills and their psychological foundations are critical not only for the context of individual but also social and global contexts. Therefore, a global preschool curriculum specifically designed to foster prosocial behavior is needed for preparing young children with competencies that are critical for their future.

References

- Aguilar-Pardo, D., Martínez-Arias, R., & Colmenares, F. (2013). The role of inhibition in young children’s altruistic behaviour. Cognitive Processing, 14(3), 301-307. doi:10.1007/s10339-013-0552-6

- Damon, W., Lerner, R.

M., & Eisenberg, N. (2006). Handbook of Child Psychology, Social, Emotional, and Personality Development

: Wiley.

M., & Eisenberg, N. (2006). Handbook of Child Psychology, Social, Emotional, and Personality Development

: Wiley. - Decety, J., & Michalska, K. J. (2010). Neurodevelopmental changes in the circuits underlying empathy and sympathy from childhood to adulthood. Dev Sci, 13(6), 886-899. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00940.x

- Dunfield, K., Kuhlmeier, V. A., O’Connell, L., & Kelley, E. (2011). Examining the Diversity of Prosocial Behavior: Helping, Sharing, and Comforting in Infancy. Infancy, 16(3), 227-247. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7078.2010.00041.x

- Eisenberg-Berg, N., Haake, R., Hand, M., & Sadalla, E. (1979). Effects of instructions concerning ownership of a toy on preschoolers’ sharing and defensive behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 15(4), 460-461. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.15.4.460

- Eisenberg, N., & Miller, P. A. (1987). The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychological Bulletin, 101(1), 91-119.

- Eisenberg, N., & Mussen, P. H. (1989). The Roots of Prosocial Behavior in Children. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Etkin, A., Egner, T., & Kalisch, R. (2011). Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(2), 85-93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.11.004

- Gresham, F. (2014). Evidence-Based Social Skills Interventions for Students at Risk for EBD. Remedial and Special Education, 36(2), 100-104. doi:10.1177/0741932514556183

- Gresham, F. M., Elliott, S. N. (1990). Social skills rating system manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

- Gresham, F. M., Elliott, S. N., & Kettler, R. J. (2010). Base rates of social skills acquisition/performance deficits, strengths, and problem behaviors: an analysis of the Social Skills Improvement System–Rating Scales. Psychological Assessment, 22(4), 809-815. doi:10.1037/a0020255

- Hare, T.

A., Camerer, C. F., Knoepfle, D. T., Doherty, J. P., & Rangel, A. (2010). Value Computations in Ventral Medial Prefrontal Cortex during Charitable Decision Making Incorporate Input from Regions Involved in Social Cognition. The Journal of Neuroscience, 30(2), 583. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4089-09.2010

A., Camerer, C. F., Knoepfle, D. T., Doherty, J. P., & Rangel, A. (2010). Value Computations in Ventral Medial Prefrontal Cortex during Charitable Decision Making Incorporate Input from Regions Involved in Social Cognition. The Journal of Neuroscience, 30(2), 583. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4089-09.2010 - Hein, G., Silani, G., Preuschoff, K., Batson, C. D., & Singer, T. (2010). Neural Responses to Ingroup and Outgroup Members’ Suffering Predict Individual Differences in Costly Helping. Neuron, 68(1), 149-160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.003

- Jones, D. E., Greenberg, M., & Crowley, M. (2015). Early Social-Emotional Functioning and Public Health: The Relationship Between Kindergarten Social Competence and Future Wellness. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), 2283-2290. doi:10.2105/ajph.2015.302630

- Kathryn, W. (2015). Prosocial Behaviour and Schooling. In R. E. Tremblay, B. M, P. RDeV, & A. Knafo-Noam (Eds.

), Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/prosocial-behaviour/according-experts/prosocial-behaviour-and-schooling.

), Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/prosocial-behaviour/according-experts/prosocial-behaviour-and-schooling. - Lamm, C., Decety, J., & Singer, T. (2011). Meta-analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for pain. Neuroimage, 54(3), 2492-2502. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.014

- McClelland, M. M., & Morrison, F. J. (2003). The emergence of learning-related social skills in preschool children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 18(2), 206-224. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(03)00026-7

- Michalska, K. J., Kinzler, K. D., & Decety, J. (2013). Age-related sex differences in explicit measures of empathy do not predict brain responses across childhood and adolescence. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 3, 22-32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2012.08.001

- Piaget, J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child.

New York, NY, US: Basic Books.

New York, NY, US: Basic Books. - Ruff, C. C., Ugazio, G., & Fehr, E. (2013). Changing Social Norm Compliance with Noninvasive Brain Stimulation. Science, 342(6157), 482. doi:10.1126/science.1241399

- Spitzer, M., Fischbacher, U., Herrnberger, B., Grön, G., & Fehr, E. (2007). The Neural Signature of Social Norm Compliance. Neuron, 56(1), 185-196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.011

- Steinbeis, N. (2018). Neurocognitive mechanisms of prosociality in childhood. Curr Opin Psychol, 20, 30-34. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.08.012

- Steinbeis, N., Bernhardt, Boris C., & Singer, T. (2012). Impulse Control and Underlying Functions of the Left DLPFC Mediate Age-Related and Age-Independent Individual Differences in Strategic Social Behavior. Neuron, 73(5), 1040-1051. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.027

- Steinbeis, N., Haushofer, J., Fehr, E., & Singer, T. (2014). Development of Behavioral Control and Associated vmPFC–DLPFC Connectivity Explains Children’s Increased Resistance to Temptation in Intertemporal Choice.

Cerebral Cortex, 26(1), 32-42. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhu167

Cerebral Cortex, 26(1), 32-42. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhu167 - Svetlova, M., Nichols, S. R., & Brownell, C. A. (2010). Toddlers’ Prosocial Behavior: From Instrumental to Empathic to Altruistic Helping. Child Development, 81(6), 1814-1827. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01512.x

- Warneken, F., & Tomasello, M. (2007). Helping and Cooperation at 14 Months of Age. Infancy, 11(3), 271-294. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7078.2007.tb00227.x

Prosocial behaviour | Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development

Prosocial behaviour has its roots in infancy and early childhood. To fully capture its importance it is essential to understand how it develops across ages, the factors that contribute to individual differences, its moral and value bases, the clinical aspects of low and excessive prosocial behaviour, and its relevance for schooling.

Synthesis PDF Complete topic PDFInformation sheets

Download the free PDF version here or purchase hardcopy prints from our online store.

Synthesis

Topic Editor: Prof. Ariel Knafo-Noam, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel

Topic funded by:

Why is it important?

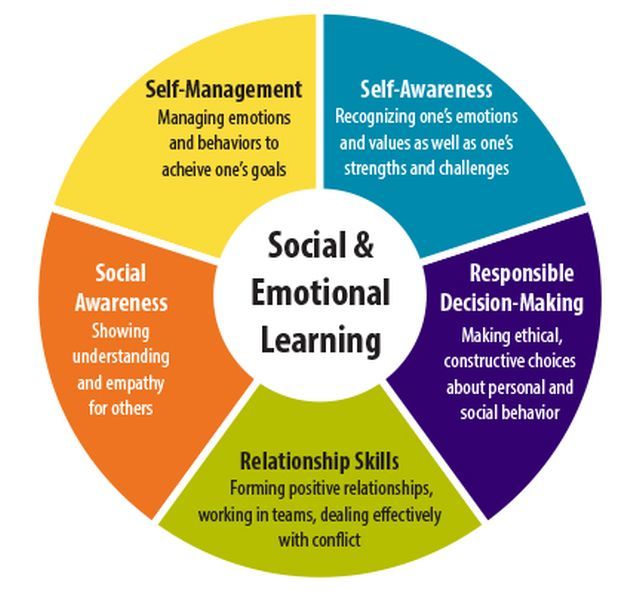

Prosocial behaviours refer to voluntary actions specifically intended to benefit or improve the well-being of another individual or group of individuals. Examples of such behaviours include helping, sharing, consoling, comforting, cooperating, and protecting someone from any potential harm. From an evolutionary perspective, prosocial behaviours may have evolved from a biological adaptation to living in society. The development of prosocial behaviours is important during the early years as these actions are associated with social and emotional competence throughout childhood (e. g., peer acceptance, empathy, self-confidence, and emotion-regulation skills). Furthermore, prosocial behaviours are associated with academic performance, and the development of cognitive competencies, such as problem-solving and moral reasoning, all of which are contributing to a positive school adjustment.

g., peer acceptance, empathy, self-confidence, and emotion-regulation skills). Furthermore, prosocial behaviours are associated with academic performance, and the development of cognitive competencies, such as problem-solving and moral reasoning, all of which are contributing to a positive school adjustment.

What do we know?

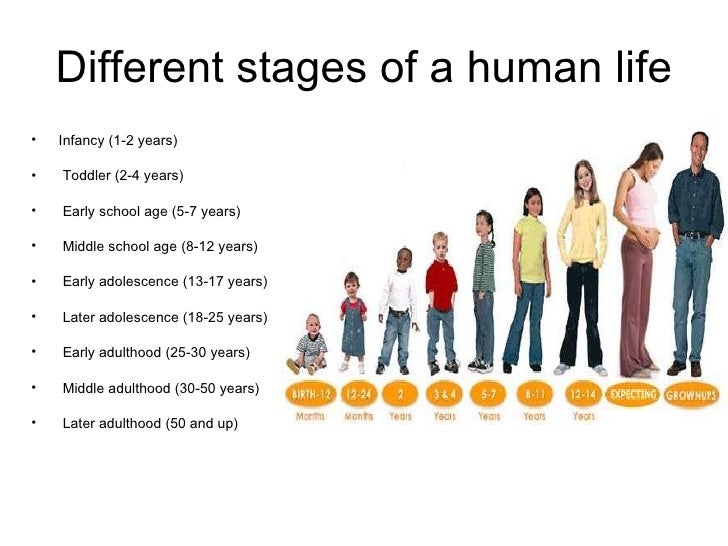

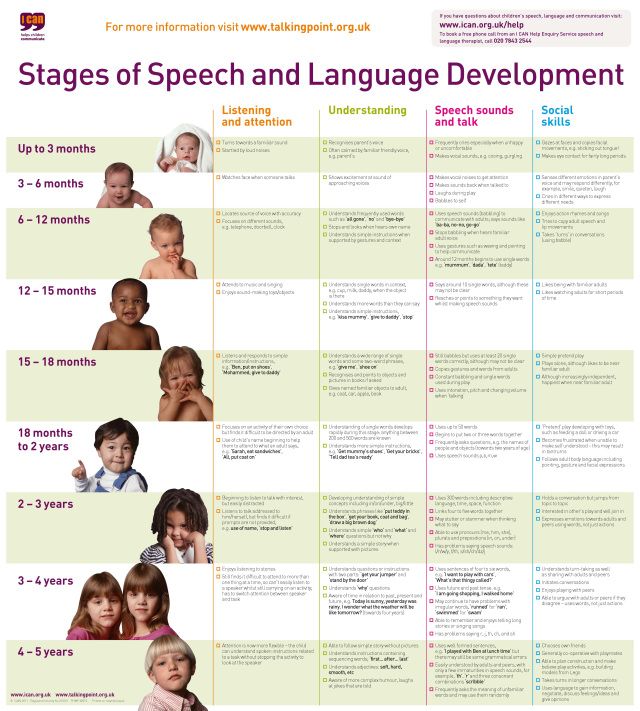

Manifestations of prosocial behaviours emerge at a young age, and the same basic forms are found across cultures. Even 18-month-old infants demonstrate early forms of prosocial behaviours (e.g., when they point an out-of-reach object or an unseen event to an adult). Around the ages of 3 and 4, children’s prosocial behaviours increase in complexity. They respond more readily to others’ negative emotional state with appropriate sharing, helping, and/or comforting. During this developmental period, children also start to demonstrate in-group favouritism, which is manifested by a tendency to exhibit more prosocial behaviours towards individuals who belong to the same group (e. g., based on perceived similarity, such as race and gender) than members of the out-group. Yet, as children develop more advanced socio-cognitive skills and spend more time interacting with their peers, they become increasingly aware of the reasons why it is important to help others, which in turn motivate them to engage in prosocial behaviours.

g., based on perceived similarity, such as race and gender) than members of the out-group. Yet, as children develop more advanced socio-cognitive skills and spend more time interacting with their peers, they become increasingly aware of the reasons why it is important to help others, which in turn motivate them to engage in prosocial behaviours.

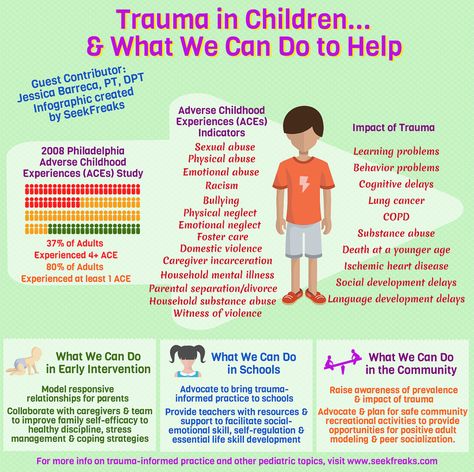

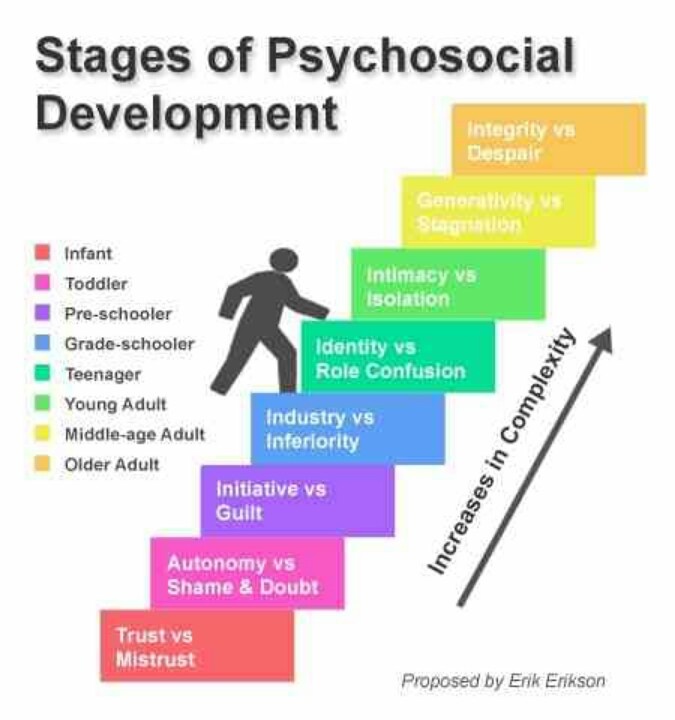

Several factors predict and/or reinforce prosocial behaviours in young children, in addition to genetic differences that account in part for individual differences. Early moral development during the first five years of life is an important foundation for prosocial behaviours. For instance, children who experience guilt following transgressions are more likely to engage in prosocial behaviours relative to those who do not, as they are increasingly aware of the consequences of their actions for the self and for others. Children’s prosocial behaviours are also influenced by feelings of empathy and the desire to help others. While there is a general consensus that empathy is an important predictor of children’s prosocial behaviours, extremes forms of empathy - either surfeits or deficits - may increase the risk of developing psychological problems later on. For example, young children who express extreme concerns for their parents’ well-being (e.g., due to marital conflicts or health problems) have been found to be at increased risk of developing anxiety or depression as they grow up. In contrast, young children’s absence of reaction and/or inappropriate reactions to someone’s distress (laughter, enjoyment) may be a precursor of behavioural difficulties. However, it is important to keep in mind that the expression of empathy falls on a continuum and is influenced not only by the child’s characteristics but also by the environment he/she is exposed to. Finally, parent and peer socialization play an important role in the development of prosocial behaviours. Parents who model prosocial behaviours and encourage children to understand the perspective of others promote the internalization of prosocial values in their children. Similarly, educators who promote collaborative peer interactions motivate the development of cognitive skills that support prosocial forms of behaviour.

For example, young children who express extreme concerns for their parents’ well-being (e.g., due to marital conflicts or health problems) have been found to be at increased risk of developing anxiety or depression as they grow up. In contrast, young children’s absence of reaction and/or inappropriate reactions to someone’s distress (laughter, enjoyment) may be a precursor of behavioural difficulties. However, it is important to keep in mind that the expression of empathy falls on a continuum and is influenced not only by the child’s characteristics but also by the environment he/she is exposed to. Finally, parent and peer socialization play an important role in the development of prosocial behaviours. Parents who model prosocial behaviours and encourage children to understand the perspective of others promote the internalization of prosocial values in their children. Similarly, educators who promote collaborative peer interactions motivate the development of cognitive skills that support prosocial forms of behaviour.

What can be done?

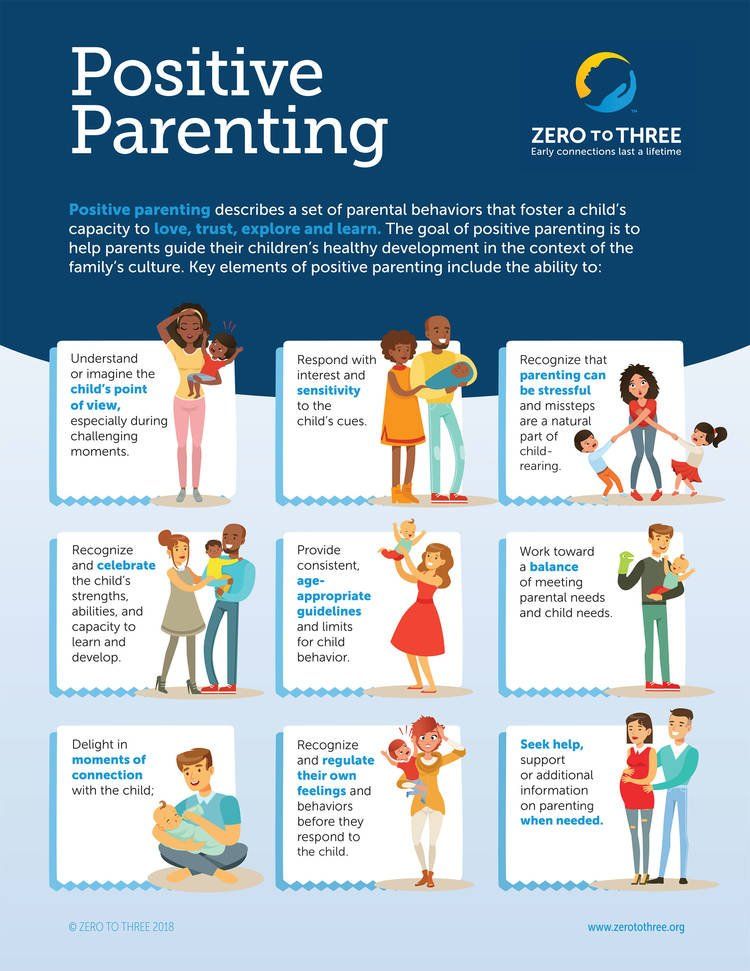

Prosocial education needs to start early at home and extend throughout the preschool years. Parents who model prosocial behaviours, exhibit warm and responsive parenting, and emphasize emotional states of others can help the development of prosocial behaviours in children. Parents are also encouraged to explain to children what they did wrong following a transgression, and how their actions may have affected the other person-–as opposed to simply punishing them. Early childhood educators can also play an important role in the development of children’s morality and prosocial behaviours by implementing instructional and intervention programs. Although more research is needed to establish a set of practical guidelines and practices that foster prosocial behaviours in young children, early interventions should emphasize:

- caring relationships with adults and peers;

- adults modelling of prosocial characteristics;

- training in empathy and perspective taking;

- active learning approaches such as cooperative learning.

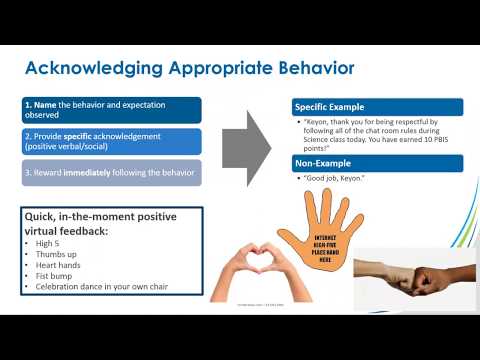

Early childhood educators can also play an active role by curbing children’s predisposed biases and by structuring collaborative interactions with peers from diverse groups (e.g., gender, cultures, religions, socio-economic backgrounds). These opportunities would have consequences on children’s beliefs about others (e.g., us versus them), and prosocial behaviours across groups. Lastly, and most importantly, parents and educators are encouraged to positively reinforce children’s prosocial tendencies, rather than to negatively reinforce their antisocial tendencies (by punishing them, for example). By putting a greater emphasis on their good actions rather than on their bad ones, children’s prosocial behaviours are more likely to be manifested.

Read moreAdditional reading

How can parents, teachers and peers facilitate moral and prosocial tendencies?

Resources and bulletins

The Encyclopedia also recommends.

..

..The Motivational Foundations of Prosocial Behavior From A Developmental Perspective–Evolutionary Roots and Key Psychological Mechanisms: Introduction to the Special Section

Child Development, Maayan Davidov, Amrisha Vaish, Ariel Knafo-Noam, Paul D. Hastings, Volume 87, Issue 6, November/December 2016, Pages 1655–1667

Article "Pedagogical conditions for the development of prosocial behavior in children of the fourth year of life" | Article (younger group) on the topic:

Pedagogical conditions for the development of prosocial behavior in children of the fourth year of life

Ekaterina Prokopyevna Ohremchuk

Educator of MKDOU No. 12 "Sunshine"

Shelekhov

The attitude to other people is the main fabric of human life and is the center of the spiritual and moral formation of the individual, which largely determines its moral value. It is these relationships that give rise to the most powerful experiences and actions.

Since in our time society requires the education of a socialized child: independent, owning the rules of interaction and the morality of the society in which he lives, the problem of the formation and development of prosocial relations of preschool children, and, in particular, children of the fourth year of life, today is relevant, since relationships with other people are born and develop most intensively at this age. In the same period, the foundations of the personality of the baby are laid, therefore, increased requirements are placed on the skill, personality, level of spiritual development of the teacher in kindergarten.

Prosocial behavior is usually understood as any action aimed at the well-being of other people. These actions are often very diverse. Their range can extend from manifestations of kindness, charitable activities to helping a person who is in danger, in a difficult or distressed situation, and even up to his salvation at the cost of his own [1].

Representatives of behaviorism (E. Thorndike, J.B. Watson, E.C. Tolman, B.F. Skinner) consider prosocial behavior as behavior caused by negative or positive empathic reinforcement (i.e., the disappearance of an unpleasant feeling that occurs when the sight of the suffering of another person or the appearance of a pleasant feeling at the sight of the liberation of a person from this suffering).

In psychoanalysis, prosocial behavior is seen as a desire to reduce a person's inherent guilt towards another by a selfless act (S. Freud, A. Adler, C. G. Jung, C. Horney, E. Berne).

In the pedagogical dictionary, the following definition of prosocial behavior is given - this is the behavior of an individual that is focused on the benefit of social groups and is the opposite of antisocial behavior, when a person tries to harm others or commits aggressive acts [2].

The concept of "pro-social relations" is considered from two theoretical approaches. In the first one (S. G. Yakobson, W. Damon), it is considered as a reflection of the attitude towards oneself, but not towards another, since it is directed not at a person, but at self-affirmation. In the second approach to prosocial behavior based on empathy (G.P. Lavrentyeva, T.V. Antonova, Hoffman, Feshbach, Staub), people are not a means of exercising their own moral qualities, but the direct goal of actions.

G. Yakobson, W. Damon), it is considered as a reflection of the attitude towards oneself, but not towards another, since it is directed not at a person, but at self-affirmation. In the second approach to prosocial behavior based on empathy (G.P. Lavrentyeva, T.V. Antonova, Hoffman, Feshbach, Staub), people are not a means of exercising their own moral qualities, but the direct goal of actions.

Prosocial behavior attracts special attention of researchers (V.S. Mukhina, T.A. Repina, etc.) as a form of interaction among children of primary preschool age. At preschool age, and, in particular, in children of the fourth year of life, prosocial behavior is expressed in the child's ability to help a peer, yield to him, share with him objects that are important for the child himself (toys, things, sweets). However, when studying the prosocial behavior of children of the fourth year of life, it is necessary to find out what is behind this or that act of the child's behavior, what is the motivation for this or that prosocial act.

Since the children of the fourth year of life, according to J. Piaget and L. Kohlberg, are on a pre-moral level, they tend to judge actions more by their consequences than by people's intentions.

In contrast to the studies of J. Piaget and L. Kohlberg, the results of the study by V.M. Kholmogorova showed that already at the age of three or four, all children demonstrate correct moral judgments and assessments - they know that sharing is good, and taking everything for themselves is bad. However, in a real life situation, only a few are able to share with a peer.

Lebedev AA considers the age period from three to four years, firstly, to be immoral. The author explains his point of view by the fact that during this period the child only acquires different habits, learns to fulfill requests and instructions. Secondly, this is the pre-moral period, which is characterized by the development of sympathetic feelings in children.

In an empathy-based approach to prosocial behavior, research by G. P. Lavrentieva, T.V. Antonova and other researchers, peers for children of the fourth year of life are not a means of exercising their own moral qualities, but the direct goal of the child's actions [3].

P. Lavrentieva, T.V. Antonova and other researchers, peers for children of the fourth year of life are not a means of exercising their own moral qualities, but the direct goal of the child's actions [3].

The early preschool age is the best soil for the formation of prosocial behavior, since during this period the child undergoes those significant changes that can be influenced from a positive position: - the formation of the simplest moral judgments, - the assimilation of moral norms of behavior, - the manifestation of attempts to empathize with another, empathy.

To organize effective work on the formation of prosocial behavior in children of this age, it is important to study the pedagogical conditions for their development.

Obviously, the prosocial attitude towards others is based on the ability to empathize, to sympathy, which manifests itself in a variety of life situations and, therefore, in order for the child not only to understand the objective meaning of norms and requirements, but also to imbue them with an appropriate emotional attitude in order for them to become criteria for his emotional assessments of his own and other people's actions, explanations and instructions from the educator and other adults are not enough. These explanations must find support in the child's own practical experience, in the experience of his activity. Moreover, the decisive role here is played by the inclusion of a preschooler in meaningful, joint activities with other children and adults. It allows him to directly experience, feel the need to comply with certain norms and rules in order to achieve important and interesting goals.

These explanations must find support in the child's own practical experience, in the experience of his activity. Moreover, the decisive role here is played by the inclusion of a preschooler in meaningful, joint activities with other children and adults. It allows him to directly experience, feel the need to comply with certain norms and rules in order to achieve important and interesting goals.

E.O. Smirnova, V.M. Kholmogorova believe that the main condition for the formation of prosocial behavior in younger preschoolers should not be the development of children's ability to reflect on their experiences and not strengthen their self-esteem, but, on the contrary, the removal of fixation on their own "I" due to the development of attention to the other, a sense of community and ownership with him [5].

Another condition for the development of prosocial behavior in younger preschoolers is the organization of joint activities - playful or productive. In such joint activities, younger preschoolers learn to coordinate their actions, cooperate, and develop prosocial communication skills. Under the influence of collective activity, as A.V. Zaporozhets, children develop the ability to "sympathize with other people, experience other people's needs and needs as their own."

Under the influence of collective activity, as A.V. Zaporozhets, children develop the ability to "sympathize with other people, experience other people's needs and needs as their own."

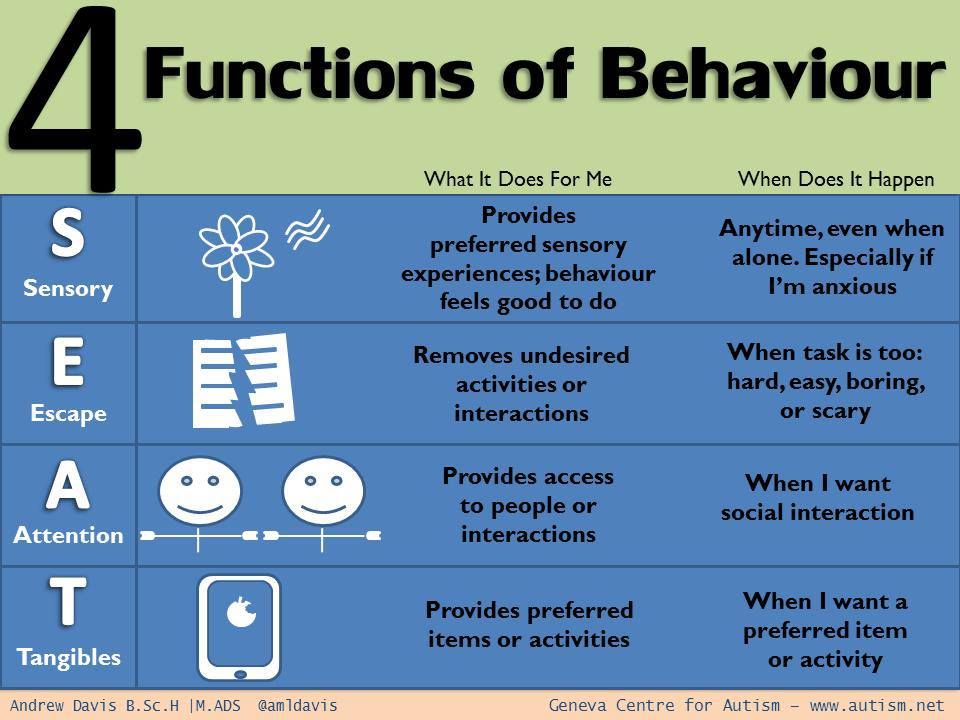

Staub E. identifies the following two pedagogical conditions that influence the development of prosocial behavior in younger preschoolers - this is role playing and induction. In the first case, children act out roles in order to see things from the other person's point of view. In the second case, adults communicate their thoughts about this or that behavior to children: for example, children can be told about what consequences their actions will have for others.

The effect of observational learning on prosocial behavior has been demonstrated in a number of studies, which have shown that modeling prosocial behavior is more effective when the model is perceived to be caring or has a special relationship with the child. However, it must be remembered that often the models are examples from films and television programs.

Particular attention should be paid to the leading activity of children of this age - play activity for the formation of their prosocial relations. Preschoolers often play role-playing games that require participants to interpret and share each other's fantasies, as well as to act in an imaginary situation defined by special rules.

According to L.S. Vygotsky, it is in the role-playing game that children learn cooperation and master other prosocial skills, as well as develop the ability to think about their behavior and manage it.

A variety of dramatization game techniques, in which children seem to come closer to the characters of the work, allow not only to reveal the emotional response of each child, but also to create conditions for the formation of emotional responsiveness in him, both in relation to his peers and in relation to adults . Through games, the educator can not only reveal the content of prosocial behavior in a fun way, but also connect this content with the specific actions of the child, this makes it possible to consolidate a positive attitude towards their implementation in everyday life.

Thus, the prosocial behavior of children of the fourth year of life, which contains the upbringing of good feelings, positive relationships, and the simplest moral manifestations, occurs in everyday everyday activities, in play, and is associated with the formation of these activities. At the same time, the main pedagogical conditions for the development of prosocial relations in children of the fourth year of life are:

- creation of conditions for the inclusion of a younger preschooler in meaningful, joint activities with other children and adults;

- removal of fixation on one's own "I" due to the development of attention to another, a sense of community and belonging with him through the creation of a subject-developing environment that stimulates the manifestations of a prosocial attitude;

- selection of socially oriented plots of role-playing games;

- organization of learning, through the observation of prosocial forms of behavior, its modeling.

References

- Furmanov, I.A. Socio-psychological problems of behavior [Text]: A course of lectures for students of the department of psychology / I.A. Furmanov. - Minsk: BSU, 2001. - 91s.

- Polonsky, V. M. Dictionary of education and pedagogy [Text] / V. M. Polonsky - M .: Higher school, 2004. - 569 p.

- Grebennikova O.V. Psychological and pedagogical conditions for the development of voluntary behavior of preschool children [Electronic resource] // Psikhologicheskie issledovaniya: elektron. scientific magazine 2009. - No. 1(3).

- Kasatkina, Yu.V., Klyueva N.V. We teach children to communicate [Text] / Yu. V. Kasatkina, N.V. Klyuev. - Yaroslavl: Academy of Development, 1997. - 240 p.

- Interpersonal relations of a child from birth to 7 years [Text] / ed. E.O. Smirnova. – M.: Voronezh, 2000. – 235 p.

Prosocial skills in children contribute to better adaptation in adult life

What are the differences between children in risk group for developing mental health problems and behavior and those who are most likely to be able in their adult life is easy to cope with any difficulties? According to experts, it's all about in skills acquired in childhood, or competencies that ensure the good quality of our entire life: these are decision-making skills, self-control, healthy self-esteem and all those skills which we can call prosocial competencies. The latter may not be as intuitive as the rest. The importance of decision making or self-control is obvious for success in life, but aren't social skills only additional, less significant?

The latter may not be as intuitive as the rest. The importance of decision making or self-control is obvious for success in life, but aren't social skills only additional, less significant?

Healthy interpersonal relationships are the foundation of all social, political and economic structure of society. Like a healthy brain consists of neurons that are interconnected and form a complex and efficient system, so a healthy society is the result of interactions between individuals.

It cannot be said that all social ties are the same. People, prone to manipulative behavior and, above all, putting their own goals, can learn quite a lot of strategies of prosocial behavior, that will allow them to communicate effectively with others, but still continue to negatively affect the mental state of others and, consequently, on the functioning of the entire social system. Such people are usually are called antisocial, and if their behavior goes beyond norms - psychopaths or sociopaths. Studying the behavior of such people allows identify ways to overcome social problems that it can generate.

Studying the behavior of such people allows identify ways to overcome social problems that it can generate.

It is necessary to understand how the concepts differ antisocial, asocial and prosocial behavior. antisocial behavior involves avoiding interactions with other people, while antisocial is active aggression towards society. Prosocial behavior, on the contrary, involves an active desire to cooperate with others, and also active empathy for them. Prosocial behavior includes for example, protecting the weaker and helping them, caring for others, sympathy.

Children with developed prosocial behavior skills better, turn out to be more adapted in almost all areas of life. They take fewer risks, they have fewer mental health problems because they more flexible. In addition, other important skills they also have are more advanced. high level. In general, such children devote more time to education, achieve great success in the academic field, contribute through their activities greater contribution to the development of society. Even their average life expectancy turns out to be more.

Even their average life expectancy turns out to be more.

Although there is no specific "magic number" prosocial connections necessary for the harmonious development of the child, each a person in childhood needs a unique experience of communicating with a variety of different people, including both adults and peers. Parents, grandparents, other older relatives provide the child with the so-called "vertical" interactions with more experienced, authoritative people. Friends, brothers and sisters, classmates enter with the child into "horizontal" interactions in which all parties occupy equal positions.

Like almost all important life skills, the ability to to establish prosocial connections is based on the processes of self-regulation. IN In particular, for the development of prosocial skills, these two basic resource as the child's ability to regulate their negative emotions (she begins to form already from birth) and developing later age, the ability to accurately determine the emotions of others (it is included in so called "theory of mind", or Theory of mind) and correctly on them to react. This ability is fundamental to the resolution potential conflicts. Thus, helping children learn social skills - not just teaching the rules of good behavior, but also developing them emotional self-regulation. The first step on this path is to create a strong and secure emotional attachment between children and parents.

This ability is fundamental to the resolution potential conflicts. Thus, helping children learn social skills - not just teaching the rules of good behavior, but also developing them emotional self-regulation. The first step on this path is to create a strong and secure emotional attachment between children and parents.

Parents who are emotionally "attuned" to experiences their child, are well able to understand his emotional states and their causes, and answer them correctly. Attachment style is formed in the first years of a child's life. Attachment as defined by a University psychologist Maryland Jude Cassidy, considered "reliable if the child feels in security, and unreliable, if he does not have such a feeling - defining here is the desire for the experience of security."

Children who have not developed a secure type of attachment, growing up, have less psychological stability than their peers, and are less able to regulate their own emotions and understand the emotions of others. As a result, they are also more prone to stress, depression and other emotional disorders.

As a result, they are also more prone to stress, depression and other emotional disorders.

Researchers Joan Grusek and Amanda Sherman from the University Toronto notes that "the child's need for care and protection is present from the very first minutes of life, and the way his parents respond to it plays important role in shaping empathy and prosocial behavior." Grusek s role peers describe parents in meeting these needs child through five interconnected areas. The first one is the need to ensure protection child because when thanks parental support reduces the stressful state of the child, their own The child's capacity for empathy develops and strengthens. According to Grusek and Sherman, when parents understand how best to support their children, children develop coping strategies more successfully, and teachers evaluate such children as more prosocially oriented. Even teenagers who turn to parents for emotional support and get help from them, demonstrate the manifestations of those moral qualities that are important for prosocial behavior.

Second feature - reciprocity positive emotional manifestations. Children need to understand what parents like spend time with them and help them with their reasonable requests. Then children will project such relationships onto other people - peers, teachers, etc., gladly fulfilling their reasonable requests.

The third sphere of interaction between children and parents includes reasonable parental control providing a sufficient level independence of children so that they can recognize the connection between their decisions and their consequences. If prosocial patterns of behavior are included in the awareness of the child's own identity, he will adhere to them even in difficult social situations. Achieving this level of internalization It begins with the fact that parents themselves show their children examples of the behavior that what they want to see in children.

Fourth sphere - directed emotional learning that can take place at school, at home, with friends and during many other social contexts. According to research, young children whose mothers try to explain what emotions they experience as they grow up, make more attempts to understand the emotions of others, and are also more interested in them emotional state.

According to research, young children whose mothers try to explain what emotions they experience as they grow up, make more attempts to understand the emotions of others, and are also more interested in them emotional state.

At the age of about 13 months, children, according to scientists, acquire the ability to understand what intentions belong to individuals, and which are shared by whole groups of people. The fifth important factor in the formation prosocial - belonging to group . According to the group, which the child relates himself to, he also forms the norms of behavior adopted in this group.

Literature:

-

Monica Y. Bartlett and David DeSteno, Gratitude and Prosocial Behavior: Helping When It Costs You. in Association for Psychological Science (2006).

-

Jude Cassidy, The Nature of the Child's Ties. in Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications, edited by Jude Cassidy and P.