Anxiety cause itchy skin

What You Can Do When They Happen Together

Often anxiety and itchy skin can occur as separate conditions. Other times, they may cause one another. Treatment can depend on the cause.

If you have anxiety and itchy skin, it’s possible that you’re dealing with two distinct issues. It’s also possible that these conditions are closely linked.

Anxiety disorders can cause some people to experience itchy skin and itchy skin conditions can lead to anxiety. One can exacerbate the other.

Each can be effectively treated, but it’s important to determine whether the anxiety and itching are connected. Itching due to anxiety is no less real than itching from other causes, but it may take a different approach to treatment.

According to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, anxiety disorders affect 40 million adults in the United States every year. More than 1 in 5 people experience chronic itch at some point in their lifetime.

It’s difficult to know how many people have anxiety-related itching, or psychogenic itch.

Continue reading to learn more about the association between anxiety and itching, and what you can expect of treatment.

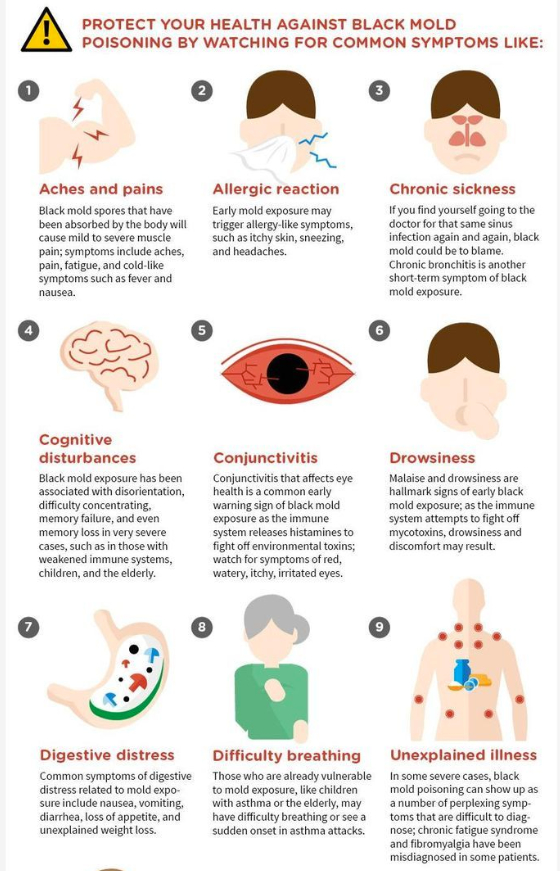

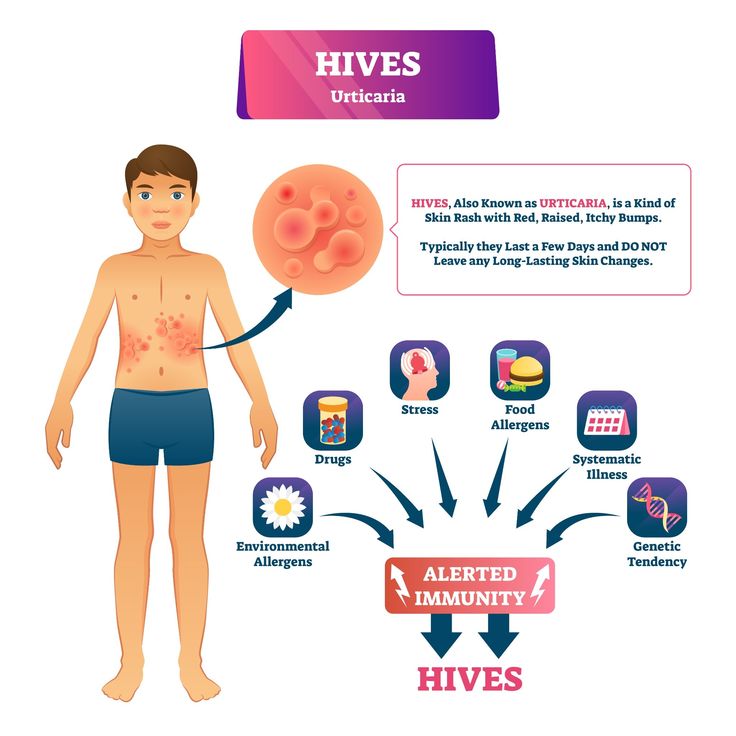

Anxiety, especially if it’s chronic, can affect your health in many ways. Anxiety is related to a number of skin problems. Just think about how a brief moment of embarrassment can cause you to blush or how being nervous can make some people break out in hives.

The weight of mental or emotional stress can also lead to some serious itching.

Your brain is always communicating with nerve endings in your skin. When anxiety kicks in, your body’s stress response can go into overdrive. This can affect your nervous system and cause sensory symptoms like burning or itching of the skin, with or without visible signs.

You can experience this sensation anywhere on your skin, including your arms, legs, face, and scalp. You might feel it only intermittently or it could be quite persistent. The itch can happen at the same time as symptoms of anxiety or it can occur separately.

Even if the cause of your itching is anxiety, serious skin problems can develop if you scratch too much or too vigorously. This can leave you with irritated, broken, or bleeding skin. It can also lead to infection. Not only that, but the scratching probably won’t do much to relieve the itch.

On the other hand, the skin condition and relentless itching may have come first, prompting the anxiety.

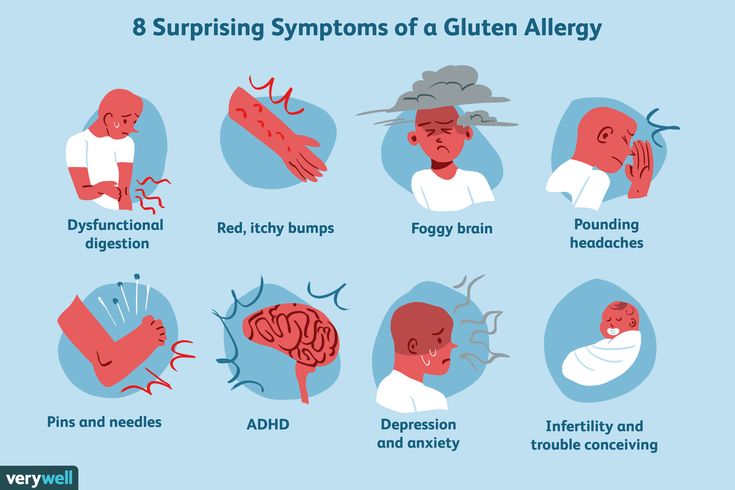

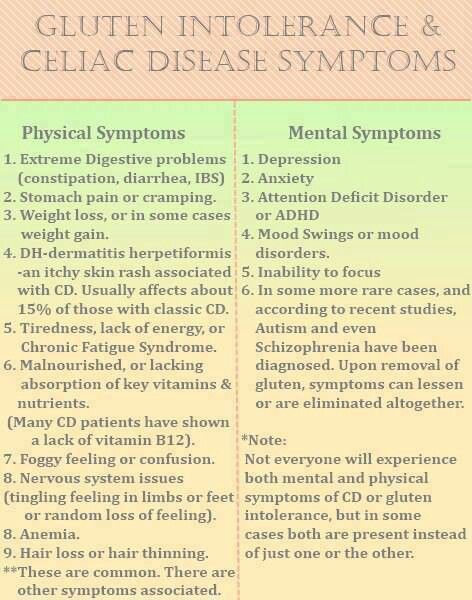

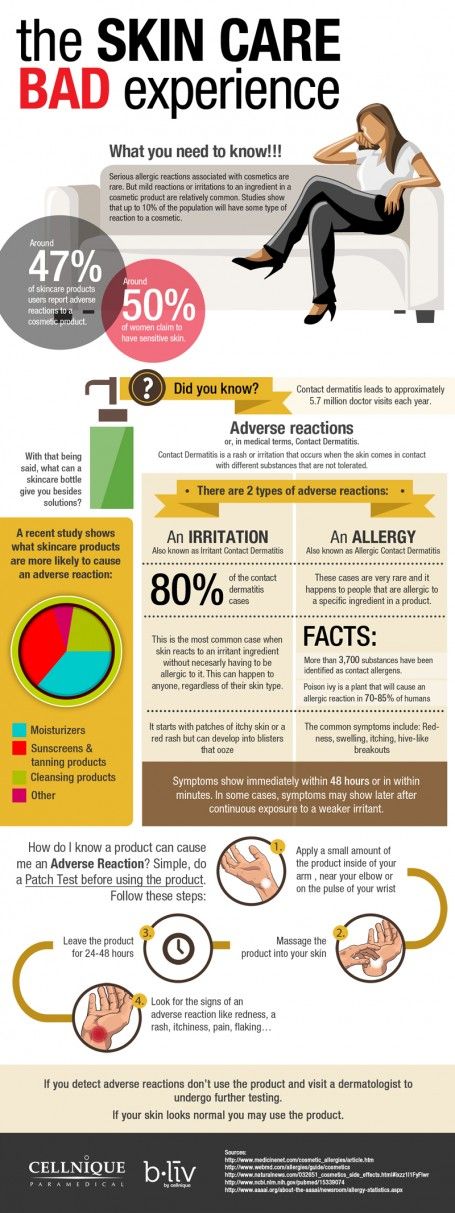

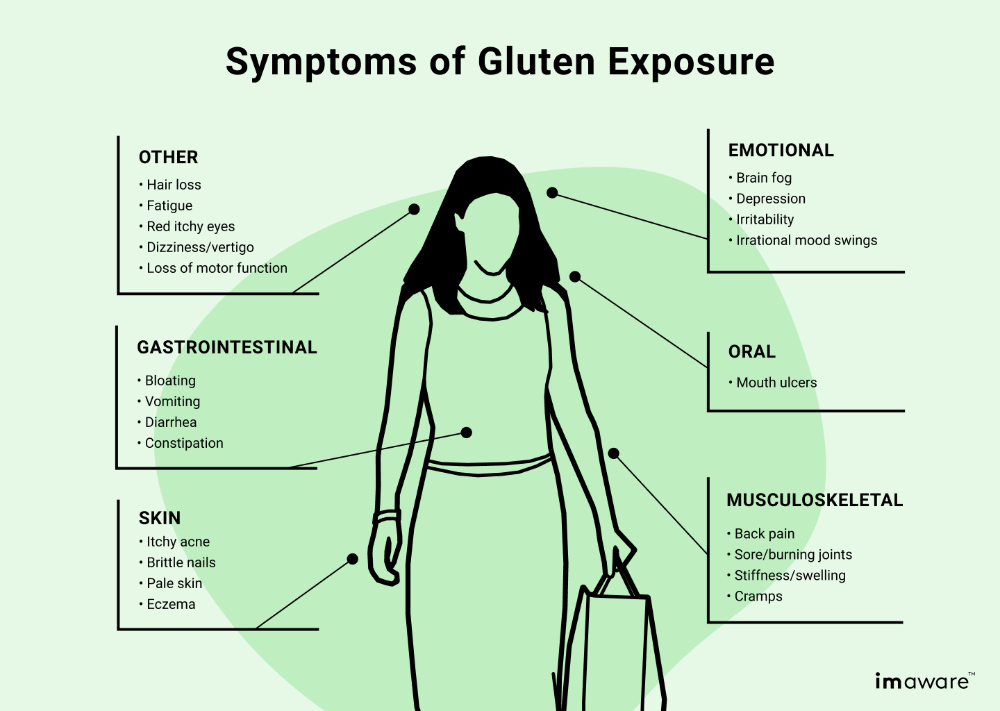

You may indeed have two unrelated problems — anxiety plus an itch caused by something else entirely. Depending on your specific symptoms, your doctor may want to investigate some other causes of itchy skin, such as:

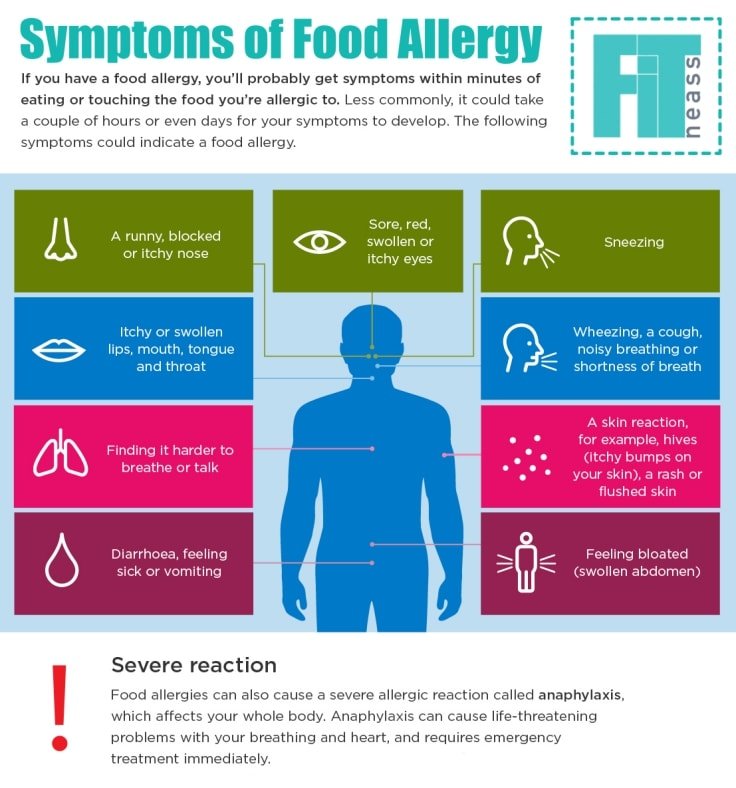

- allergic reaction

- dry skin

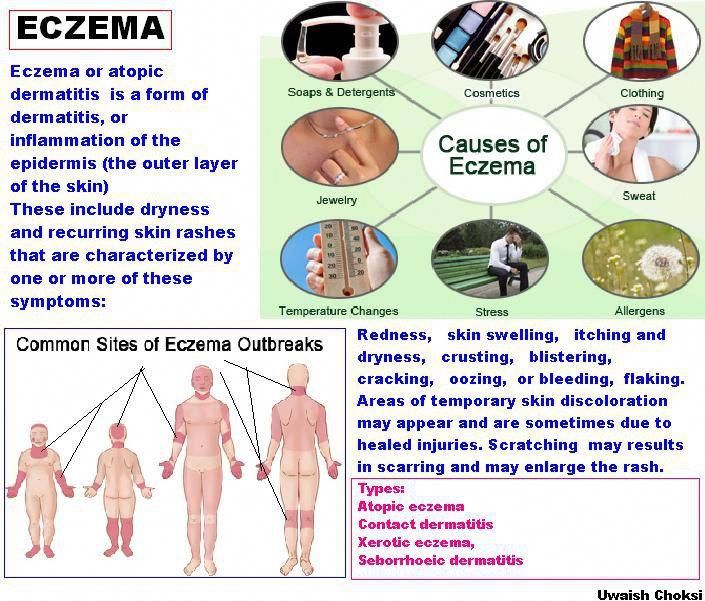

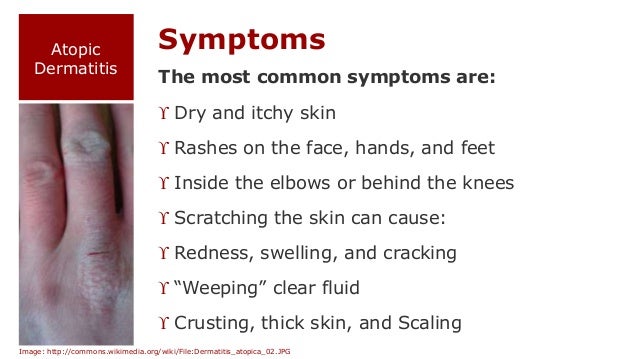

- eczema

- insect bites and stings

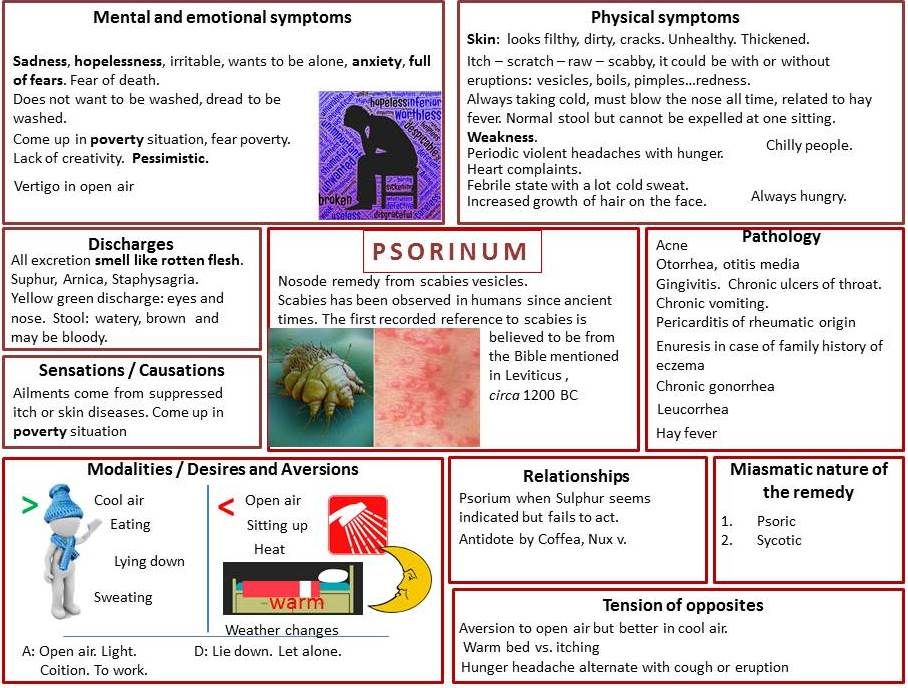

- psoriasis

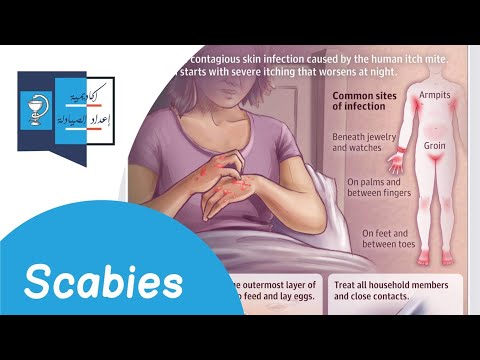

- scabies

- shingles

Most of these conditions can be identified upon physical examination. Itchy skin can also be a symptom of less visible conditions such as:

- anemia

- cancers such as lymphoma and multiple myeloma

- diabetes

- kidney failure

- liver disease

- multiple sclerosis

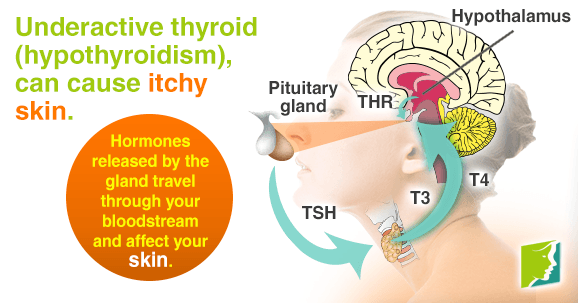

- thyroid problems

That’s why it’s so important to talk to your doctor about:

- your medical history, including pre-existing conditions, allergies, and medications

- symptoms of anxiety or depression

- any other physical symptoms you may have, even if they seem unrelated

This information will help guide the diagnosis.

Treatment depends on the specific causes of anxiety and itching. No matter the cause, unrelenting itching can have a negative impact on your overall quality of life. So, it’s worth seeking treatment.

Aside from your primary care physician, you might benefit from seeing a specialist or perhaps two. A mental health professional can help you learn to manage anxiety, which can alleviate that aggravating itch.

If your skin is seriously affected, you might also need to see a dermatologist.

Psychologists can also help with dermatological problems related to anxiety. This field is called psychodermatology.

Treatment for the itch may include:

- corticosteroids or other soothing creams or ointments

- oral selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, a type of antidepressant that may ease chronic itching in some people

- light therapy sessions may help get itching under control

Here are some things you can do on your own to help relieve itching:

- Use hypoallergenic, fragrance-free moisturizer every day.

- Run a humidifier to help keep your skin moist.

- Avoid rough clothing, hot baths, harsh sunlight, or anything else that contributes to itchiness.

- Try over-the-counter products such as corticosteroid cream, calamine lotion, or topical anesthetics.

- When itching is impossible to ignore, put on some gloves or cover your skin to prevent yourself from scratching.

- Keep your fingernails trimmed so that if you do scratch, you’re less likely to break the skin.

Since stress can aggravate the itch, you’ll also need to take steps to lower your stress levels. Here are a few things you can try:

- acupuncture

- deep breathing exercises

- meditation

- yoga

A therapist can provide behavior modification therapy and other strategies to lessen anxiety. It’s also important to maintain a healthy diet, get plenty of sleep every night, and exercise regularly.

Any underlying medical conditions should also be addressed.

Anxiety and itching are both things that can come and go. If they’re fleeting and not causing any major problems, you may not need to see a doctor. If that’s the case, it’s still a good idea to mention it at your next appointment.

If anxiety and itching are interfering with your ability to function or causing visible skin damage or infection, see your primary care doctor as soon as possible. If necessary, you can get a referral to the appropriate specialist.

Untreated, the cycle of anxiety and itching can repeat over and over, ratcheting up your anxiety level. Frequent scratching can also lead to serious skin issues.

Anxiety and itching can be effectively treated, though. It may take some time, but with professional guidance, you can learn to manage anxiety, ultimately resolving the itch.

Regardless of which came first, anxiety and itching can be connected. With a combination of anxiety management and a good skincare routine, you can break the cycle and potentially rid yourself of persistent itch.

Why it happens and what to do

Anxiety is a mental health issue, but physical symptoms, such as itching, can also occur. This, in turn can cause further irritation and anxiety.

Anxiety and itching can also lead to a vicious circle in some people.

This cycle of anxiety and itchiness can be hard to break. In some people, anxiety may also cause underlying skin conditions to flare up, causing more itchiness.

Keep reading to learn more about the link between itching and anxiety.

Although it is not always the case, anxiety and itching can sometimes share a very close relationship.

An anxiety disorder may cause the sensation of itching. If this happens, the itching is not due to an underlying skin condition or irritant, but instead, appears as a symptom of anxiety.

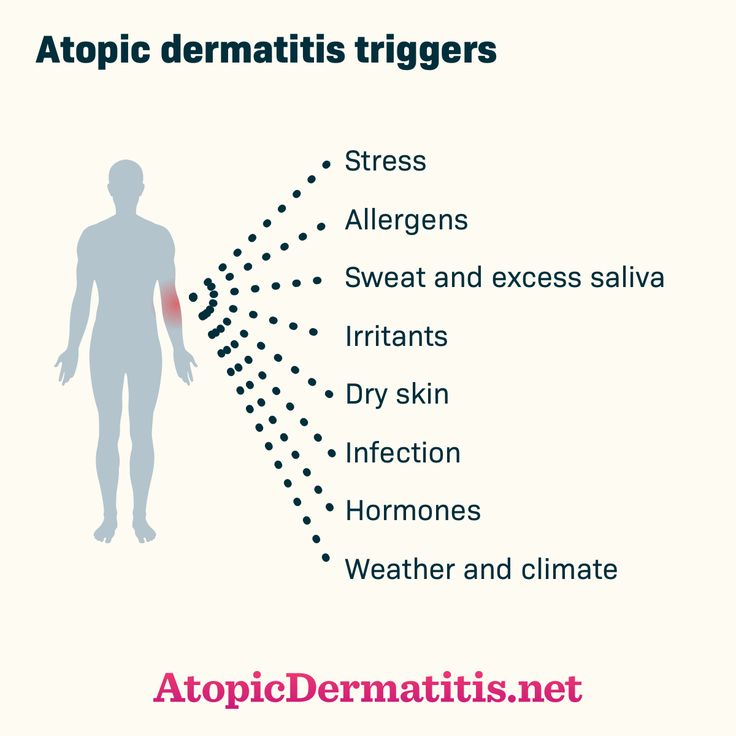

For example, a 2016 study found that skin conditions, including itching and flaky scalps, are common in people experiencing high-stress situations, having psychological conditions, or going through a major life event.

Stress causes several changes in the body, such as hormonal fluctuations and changes in the nervous system, which could lead to unpleasant sensations along one or more nerves. These sensations can cause a burning or itching feeling anywhere on the skin.

Anxiety and skin conditions

A person with an underlying skin condition may also experience increased itchiness relating to their preexisting condition. In these people, symptoms of stress may exacerbate their symptoms or trigger flare-ups.

People living with chronic skin conditions that cause itchiness often report that psychological stress is an aggravating factor for their symptoms.

Skin conditions that may worsen with anxiety include:

- psoriasis

- eczema

- lichen planus

Can itching cause anxiety?

While anxiety may cause or worsen itching, the reverse is also true. Itching, and conditions that cause persistent itching, can be a source of anxiety.

Research shows there is an association between chronic itch conditions and higher levels of stress and anxiety.

People with a skin condition, such as eczema or psoriasis, may find the condition itself a source of stress and anxiety. Symptoms can disrupt daily life, and a flare-up can be distracting and irritating.

The physical itch is not the only source of anxiety for people with these conditions. People with skin conditions that cause visible damage or marks to the skin may deal with social stress or anxiety when interacting with others.

Learn more about the link between psoriasis and social anxiety here.

Treatment will vary based on the underlying condition and the root cause of the itchiness or anxiety.

Treatments for skin conditions may include medicated creams to help stop itching, as well as targeted medications for the individual symptoms or condition itself.

A therapist or psychologist can also help people with anxiety disorders manage their anxiety levels through behavioral therapy. This therapy can help people change the thought patterns that lead to anxiety. In some people, medications may be necessary.

In some people, medications may be necessary.

It is also important to find ways to reduce stress, as it can trigger symptoms. Practices that may help reduce stress include:

- acupuncture

- massage therapy

- movement activities, such as tai chi or yoga

- breathing exercises

- meditation

- regular exercise

Learn more about managing stress here.

The first step toward treatment for anxiety and itching is to identify the root cause and break the cycle of symptoms.

Diagnosing anxiety

A full physical and mental assessment is necessary for an anxiety diagnosis. An initial treatment provider may also refer people to a mental health specialist to help identify any underlying causes of anxiety.

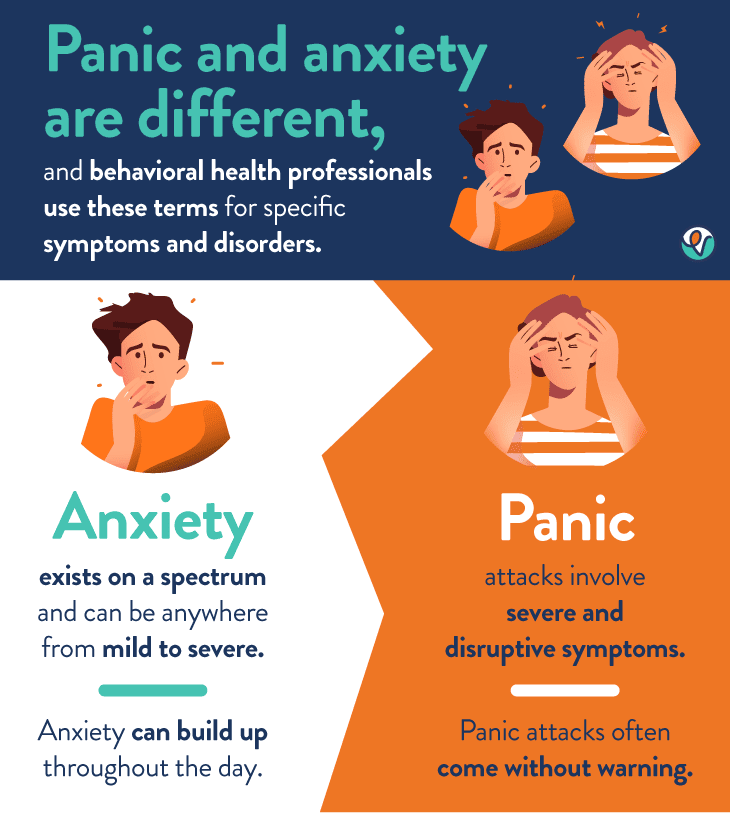

There are many types of anxiety disorders, including:

- generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

- social anxiety disorder

- panic disorder

- separation anxiety disorder

- phobias

Each type of anxiety disorder will have different symptoms and diagnostic criteria. For example, for a diagnosis of GAD, a person must exhibit excessive anxiety and worry most days for at least 6 months.

For example, for a diagnosis of GAD, a person must exhibit excessive anxiety and worry most days for at least 6 months.

Learn more about the different types of anxiety and their diagnoses in our dedicated hub.

Diagnosing skin conditions

Doctors can help diagnose underlying skin conditions or refer the person to a dermatologist for additional testing. They may ask the person to take medical tests, such as blood tests, to screen for other problematic conditions that may influence itching.

Once the person receives a diagnosis, a doctor can begin treatment.

As part of a diagnosis for itching skin, doctors will check for other potential causes. Several different conditions and factors can cause itching, including:

- neurological conditions, such as multiple sclerosis, diabetic neuropathy, and shingles

- other psychiatric conditions, such as depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder

- diseases involving the internal organs, such as liver or kidney failure, anemia, and even some types of cancer

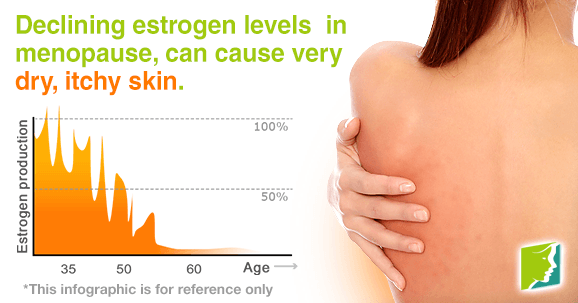

- pregnancy and hormonal changes

- side effects from some medications

In some people, the itching is idiopathic, meaning it has no known cause. The person will need to work closely with their doctor to find ways to manage this symptom.

The person will need to work closely with their doctor to find ways to manage this symptom.

Anyone experiencing itchiness or anxiety that affects their daily life should contact a doctor. A doctor may refer the person to a dermatologist to test for skin conditions or to a mental health specialist for therapy for an anxiety disorder.

Anyone who notices additional or worsening symptoms after starting a new treatment may also wish to speak with a doctor to modify their treatment.

Although it is not true in every person, anxiety and itchiness often have a close relationship.

People with skin conditions, such as psoriasis and eczema, may notice symptoms flare up during periods of high stress or anxiety. Anxiety disorders may also cause itchiness.

Additionally, chronic itching can be a source of irritation, stress, and anxiety for many people, potentially leading to a cycle of symptoms that can greatly reduce a person’s quality of life.

How the itch arises and what does the philosophy have to do with it

The unbearable itch is perhaps the worst form of torture.

The desire to scratch cannot be overcome, but it causes disgust among others: a person who itches seems not only mangy, but also weak-willed. Neurology professor David Linden devoted a chapter of his book Touch. The feeling that makes us human." T&P publish it with abbreviations.

The desire to scratch cannot be overcome, but it causes disgust among others: a person who itches seems not only mangy, but also weak-willed. Neurology professor David Linden devoted a chapter of his book Touch. The feeling that makes us human." T&P publish it with abbreviations.

Touch. Feeling that makes us human

David Linden

Sinbad. 2018

The sensation of itching is greatly influenced by cognitive and emotional factors. Once, in a camp in the Amazonian jungle, I was already falling asleep, when I suddenly felt that my arm was itching. I grabbed a flashlight and glasses, saw that the cause of the itching was a huge centipede, and threw it away. From that moment on, I had to forget about sleep. I gained unprecedented vigilance: every breath of the breeze, every movement of the muscles caused itching - and so on all night, and this concerned not only the same hand, but also the whole body. I mentally wrestled with centipedes until dawn.

The terrible, painful nature of itching and scabies is well known. In Dante's hell, ordinary deceivers (alchemists, impostors and counterfeiters) are thrown into the eighth circle of hell, where they suffer from an eternal itch. Only those who committed treachery - deceived the trust of people whose love and devotion they enjoyed (for example, Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus Christ) - will face a more severe punishment in the ninth circle, where they are frozen into the ice. A question arises that lies at the intersection of biology and philosophy: is itching really a unique form of tactile sensations that is qualitatively different from the rest, or is it just another type of stimulation that is based on one or more tactile sensations? To draw an analogy: can it be said that itching and other tactile sensations are different from each other in the same way that a saxophone is different from a piano? Both instruments produce sound, but these sounds are qualitatively different. Or is it rather a correspondence between piano-played bebop jazz and classical music of the Romantic era? They also differ significantly from each other in musical structure and context, but are performed on the same musical instrument. Previously, such questions were at the mercy of philosophers. Today, biologists can also intervene in the discussion.

Or is it rather a correspondence between piano-played bebop jazz and classical music of the Romantic era? They also differ significantly from each other in musical structure and context, but are performed on the same musical instrument. Previously, such questions were at the mercy of philosophers. Today, biologists can also intervene in the discussion.

In this 1827 illustration by William Blake, deceivers are tormented by an eternal itch in the eighth circle of Dante's Hell (Canto 29). The eighth circle is subdivided into ten concentric slits, each subsequent one probably worse than the last. Deceivers occupy the last and, apparently, the most terrible slot. For comparison: the first slot is intended for pimps and seducers, who are constantly scourged by demons on the go. Used by permission of the Fogg Museum at Harvard University (anonymous donation in honor of Jacob Rosenberg, 63.1979.1).

Those who believe that itching is not one of the types of tactile sensations, but simply another way of their occurrence, point out that this is only a special case of pain - weak and muffled. They quite rightly note that itching and pain have a number of the same properties. Both are responses to a variety of stimuli: mechanical, chemical, and sometimes thermal. In particular, it is worth noting that both pain and itching can be caused by chemical products of inflammation, and are eliminated by anti-inflammatory drugs. Both are highly dependent on cognitive and emotional factors, including attention, anxiety, and expectations. Both signal an intrusion into our environment of what should be avoided: these are sensations that motivate certain actions. Pain leads to reflex avoidance of its source; itching causes reflex scratching. Scratching itchy places, as well as avoiding pain in order to avoid tissue damage, is considered a protective measure. It allows you to expel poisonous arthropods (spiders, wasps, scorpions) or animals that carry pathogens (malarial mosquitoes or plague-carrying flies).

They quite rightly note that itching and pain have a number of the same properties. Both are responses to a variety of stimuli: mechanical, chemical, and sometimes thermal. In particular, it is worth noting that both pain and itching can be caused by chemical products of inflammation, and are eliminated by anti-inflammatory drugs. Both are highly dependent on cognitive and emotional factors, including attention, anxiety, and expectations. Both signal an intrusion into our environment of what should be avoided: these are sensations that motivate certain actions. Pain leads to reflex avoidance of its source; itching causes reflex scratching. Scratching itchy places, as well as avoiding pain in order to avoid tissue damage, is considered a protective measure. It allows you to expel poisonous arthropods (spiders, wasps, scorpions) or animals that carry pathogens (malarial mosquitoes or plague-carrying flies).

If itching were just a mild or intermittent form of pain, one might assume that an increase in the intensity or frequency of itch-producing stimuli would lead to its transition to pain, and a corresponding decrease in painful stimuli would turn pain into itching, but thorough laboratory studies have shown that this never happens.

Mild pain is just mild pain and intense itching is intense itching. Another key difference between itching and pain concerns their localization in the body.

If pain is felt in the skin, muscles, ligaments and internal organs, then itching is limited only to the outer layer of the skin (both hairy and smooth) and the adjacent mucous membranes that surround, for example, the mouth, throat, eyes, nose, labia minora and anus. The intestines may hurt, but not itch.

If itch is a unique form of touch, then one would expect that there would be sensory neuron fibers in the skin that only fire in response to itch stimuli and that, when stimulated electrically in the laboratory, produce itching rather than pain. This is the so-called specialization theory, which opposes the theory of structure decoding, according to which the same sensory neurons can signal both itching and pain, depending on the structure of electrical impulses. […]

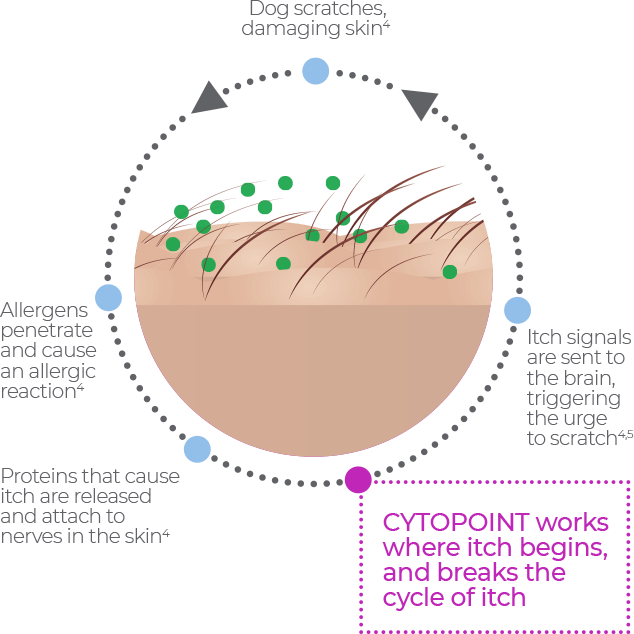

Itching can be caused by many different types of skin stimulation. In many cases, we do not even yet have an understanding of the molecular effects that cause itching. For most itch stimuli, the path to the brain is indirect. For example, if the skin is heavily rubbed or shows a local reaction to an allergen, an inflammatory cascade is activated. Molecules secreted by immune cells (such as histamine from mast cells) can reach histamine receptors located at the free ends of sensory neurons in the epidermis and induce them to emit electrical impulses.

In many cases, we do not even yet have an understanding of the molecular effects that cause itching. For most itch stimuli, the path to the brain is indirect. For example, if the skin is heavily rubbed or shows a local reaction to an allergen, an inflammatory cascade is activated. Molecules secreted by immune cells (such as histamine from mast cells) can reach histamine receptors located at the free ends of sensory neurons in the epidermis and induce them to emit electrical impulses.

Two different C-fiber pathways in itch versus pain. The neurotransmitter NPPB appears to be specific for itch neurons. On the contrary, pain neurons release glutamate, thereby sending a signal to the neurons of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. These neurons contain NPPB receptors and in turn release the rare neurotransmitter GRP, signaling it to the next neurons in the chain. Deletion of neurons with GRP receptors blocks the sensation of itching, but not the sensation of pain or light touch, suggesting that these two synaptic connections are specific to itching. Pruritus neurons can be divided into at least two categories: those that contain the chloroquine receptor MrgprA3 and primarily transmit non-histamine pruritus, and those that possess only a histamine receptor and are responsible for histamine pruritus. Histamine receptors excite nerve endings by opening the TRPV1 ion channel, while chloroquine and BAM8-22 receptors open the TRPA1 ion channel. This diagram only provides a general outline. It is likely that there are other populations of itch neurons than those shown here. In addition, the synaptic interactions between information flows in the spinal cord are currently not well understood.

Pruritus neurons can be divided into at least two categories: those that contain the chloroquine receptor MrgprA3 and primarily transmit non-histamine pruritus, and those that possess only a histamine receptor and are responsible for histamine pruritus. Histamine receptors excite nerve endings by opening the TRPV1 ion channel, while chloroquine and BAM8-22 receptors open the TRPA1 ion channel. This diagram only provides a general outline. It is likely that there are other populations of itch neurons than those shown here. In addition, the synaptic interactions between information flows in the spinal cord are currently not well understood.

In another example, a fragment of the naturally occurring protein BAM8-22 enters another receptor on the itch nerve endings in the skin, called MrgprC11 in mice and hMrgprX1 in humans. Sometimes there is a direct activation of the itch receptor in the environment. For example, the antimalarial drug chloroquine is well known to cause itching. Chloroquine goes directly to another sensory neuron receptor called MrgprA3. Note that there are at least three molecular sensors that activate the neurons responsible for itch recognition. And if some are activated directly by environmental signals, then most react to a chemical intermediary signal in the body itself.

Note that there are at least three molecular sensors that activate the neurons responsible for itch recognition. And if some are activated directly by environmental signals, then most react to a chemical intermediary signal in the body itself.

If there really are special neurons responsible for itching, then the following statements are also true: 1) we can destroy or suppress these neurons and block the sensation of itching, while other tactile sensations - pain and temperature - remain unchanged; 2) the selective activation of these specialized itch neurons should cause the sensation of itching, but not pain or other tactile sensations; 3) the anatomical distribution of nerve endings reflects the known distribution of the sensation of itching: they must be present in the epidermis and in the outer mucous membranes, but absent in the muscles, ligaments, internal organs, etc. […]

In general, the manipulations with mouse NPPB* and MrgprA3 that we have discussed show that there seems to be at least one set of neurons specifically responsible for itching: these are cells with NPPB and MrgprA3. Perhaps there are other specialized neurons. It is also very likely that there are at least a few neurons that transmit information about both pain and itching, and these sensations are encoded using a different structure of electrical signals. In general, studies show the presence of at least one pathway specialized in the transmission of pruritus, but the role of structural differences in the coding of pruritus cannot be ruled out.

Perhaps there are other specialized neurons. It is also very likely that there are at least a few neurons that transmit information about both pain and itching, and these sensations are encoded using a different structure of electrical signals. In general, studies show the presence of at least one pathway specialized in the transmission of pruritus, but the role of structural differences in the coding of pruritus cannot be ruled out.

What do these results mean for our basic neurophilosophical question? Confirmation of the presence of a specific channel for itching corresponds to the concept of itching as a unique and qualitatively different sensation from all others. At the same time, it should be noted that we do not yet know what happens in the flow of information about itching on the way to the brain. It almost certainly mixes with other tactile sensations to some extent and probably loses specificity. Perhaps, however, experience is the best judge here: almost all the languages studied so far have a single word for itching. […]

Perhaps, however, experience is the best judge here: almost all the languages studied so far have a single word for itching. […]

It is very pleasant to scratch where it itches. Although we know that itching will get even worse when we stop scratching, most of us can't help ourselves and continue to scratch our skin.

Scabies is so irresistible, and relief from itching brings such pleasure that the word "itch" (itch?) is already used in the sense of "strongly wanting." Woody Guthrie's "Hesitating Beauty" contains the lyrics: "Well, I know that you are itching to get married, Nora Lee" (Well, I know that you are itching to get married, Nora Lee / And I know I am twitching for the same thing, Nora Lee). We understand well what this means: itching is a good metaphor for unsatisfied desire.

In one unpleasant experiment, volunteers were pricked with hairs of the Mucuna sting plant, which causes intense itching. They were applied to the forearm, back and ankles, after which the experimenter scratched the affected areas with a small brush.![]() Every thirty seconds, participants rated the intensity of itching and the pleasant sensation of scratching. It turned out that scratching the back was the most effective in relieving itching, but scratching the ankle caused the most pleasant sensations.

Every thirty seconds, participants rated the intensity of itching and the pleasant sensation of scratching. It turned out that scratching the back was the most effective in relieving itching, but scratching the ankle caused the most pleasant sensations.

Why does scratching temporarily relieve itching? We don't know for sure. One theory states that our perception of itching depends on a balance of pain and itching signals that converge somewhere in the spinal cord; when we scratch, it causes mild pain that competes with the itching sensation and thereby relieves it.

Pain from needle sticks, electric shocks, and painful heat or cold can also relieve itching.

However, in some cases even the slightest scratching, which has a lower pain threshold, eliminates it.

One version of this theory states that the appearance of a very finely localized stimulus on the skin, such as the legs of a small insect, can activate itch-specific neurons, and this sensation travels intact through the spinal cord to the brain, causing a feeling of itching. And when this area is scratched, activating tactile receptors in a wider area, then inhibitory circuits of the spinal cord are involved, which prevent the sensation of itching in the brain. It is possible that evolution provided for the sensation of itching from small, localized touches on the skin in order to turn on reflex scratching and thereby be less at risk from insect-borne toxins and infections.

And when this area is scratched, activating tactile receptors in a wider area, then inhibitory circuits of the spinal cord are involved, which prevent the sensation of itching in the brain. It is possible that evolution provided for the sensation of itching from small, localized touches on the skin in order to turn on reflex scratching and thereby be less at risk from insect-borne toxins and infections.

It is well known that opiates such as heroin and oxycodone can lead to actual bouts of scabies. Heroin addicts value a particularly "itchy" dose of the drug, based on the correct notion that there is a connection between itching and psychoactivity. Narcologists and drug enforcement officers are especially vigilant with scabies sufferers, as this may be indicative of chronic opiate use. Opiate pruritus is also common in clinical settings: about 80% of patients prescribed opiates as painkillers experience itching, which occurs even when the opiate is injected directly into the cerebrospinal fluid, minimizing its direct effects on the brain and sensory nerves. […]

[…]

As in the case of pain, there is no single area in the brain responsible for the perception of itching. If you do not understand in detail, then with pain and itching, almost the same parts of the brain are activated. Itching activates both meaningful sensory areas, such as the thalamus, primary and secondary somatosensory cortex, and affective-emotional-cognitive areas - the cerebellar amygdala, the central lobe, the anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortex. Both pain and itching indirectly excite the zones responsible for movement planning and coordination, causing and changing the corresponding reactions. […]

After recovering from herpes zoster, this 39-year-old woman began to suffer from a terrible and incurable itch on the right side of her forehead. Due to deprivation, the skin in this area became numb, so that she did not feel pain, scratching her skin and skull, and eventually got to the brain. Bottom: CT scan showing a hole in the skull, a protruding right anterior lobe of the brain, and damage to brain tissue. Reproduced from: Oaklander A.L., Cohen S.P., Raju S.V.Y. Intractable postherpetic itch and cutaneous deafferentation after facial shingles. Pain 96. 2002. 9–12; by permission of Elsevier.

Reproduced from: Oaklander A.L., Cohen S.P., Raju S.V.Y. Intractable postherpetic itch and cutaneous deafferentation after facial shingles. Pain 96. 2002. 9–12; by permission of Elsevier.

Those who came to a free public lecture at the German university town of Gießen did not know that they would be part of an unusual experiment. The title of the lecture, prepared in collaboration with one of the TV channels, read: "Itching: what lies behind it?" Video cameras in the hall were aimed not only at the lecturer, but also at the audience. The purpose of the experiment was to find out if it was possible to make listeners feel itchy by showing them pictures of fleas, ticks, scabs, and skin rashes. Photographs of bathers and mothers with newborn babies (i.e., people with soft, moist skin and apparently not itching) were also shown as controls. It is not surprising that the audience began to scratch intensively at the sight of photographs suggestive of itching. Subsequent lab experiments, in which participants watched similar videos, confirmed this suggestion and showed that one did not have to suffer from some form of itching to experience such social contagion with itch. An interesting explanation for this phenomenon is that people who are more empathic are more likely to itch when they see others scratching. But when the participants of the experiment filled out the corresponding questionnaires, there was no correlation between social itch and empathy. It turned out that

An interesting explanation for this phenomenon is that people who are more empathic are more likely to itch when they see others scratching. But when the participants of the experiment filled out the corresponding questionnaires, there was no correlation between social itch and empathy. It turned out that

social itch is most typical for people who are most prone to negative emotions (with high neuroticism).

Why, when we see someone bruise their finger with a hammer, we usually do not remove our own fingers, but when we see others itching, we ourselves begin to itch and itch? So far, the best explanation is that for most of human history, we have been constantly threatened by parasites that carry diseases and toxins. And if someone started scratching next to a person, there were good reasons to believe that he himself was threatened by the same dangerous insect, a worm, etc. Therefore, feeling itchy and starting to itch, minimizing the risk, was an adaptive advantage. On the contrary, pain is not contagious because it is not transmitted from person to person.

On the contrary, pain is not contagious because it is not transmitted from person to person.

Imagine that you are riding the subway and the person in front of you suddenly starts itching furiously. The itch is obviously excruciating, but answer honestly: what will you feel first of all - compassion or disgust? André Gide is considering this question:

The itch that I have been suffering from for several months ... has recently become unbearable. For several nights now I have not closed my eyes. I remember Job looking for shingles to scrape himself with, and Flaubert whose letters towards the end of his life tell of similar scabies. I tell myself that we all suffer in our own way and that it is highly unreasonable to wish to change our suffering; but I am sure that real pain would attract my attention less and would be much easier to bear. In addition, on the scale of suffering, true pain looks nobler and more regal; itching is a low, ridiculous disease, in which it is impossible to admit; they pity a suffering person - they laugh at a person who itches.

In the "Open Reading" section, we publish excerpts from books in the form in which they are provided by the publishers. Minor abbreviations are indicated by ellipsis in square brackets. The opinion of the author may not coincide with the opinion of the editors.

Pruritus: the current state of the problem | Bobko S.I., Tsykin A.A.

Introduction

The relevance of the phenomenon of itching is determined by its high prevalence and the associated socio-economic losses. Currently, the mechanisms of the pathogenesis of itching are not fully understood, there are difficulties in diagnosis. In addition, the number of therapeutic and prophylactic agents, the effectiveness of which has been confirmed in clinical trials, is limited. The first definition of itching as an unpleasant sensation, accompanied by a desire to scratch the skin, was proposed by S. Hafenreffer in 1660. Currently, the interpretation of itching has acquired additional features.

Epidemiology of pruritus

Itching is one of the most common subjective symptoms in dermatology, second in prevalence only to complaints of cosmetic defects. According to a number of authors, the prevalence of pruritus in the general population at the time of examination ranges from 8.8 to 13.9% [1-3]. According to the clinical and epidemiological data of H. Alexander [4], 35% of outpatient skin clinic patients suffer from itching caused by dermatological diseases such as nodular pruritus, lichen planus, atopic dermatitis, eczema, xerosis, etc. With psoriasis, up to 87% of patients complain of itching [5, 6], and patients with atopic dermatitis and urticaria - in 100% of cases [7]. In other studies, the prevalence of pruritus in atopic dermatitis ranged from 81 to 87%, in psoriasis - from 41 to 96% [8–10].

Itching for 6 weeks. and more, according to the conclusion of the International Forum for Study of Itch (IFSI), are classified as chronic. Itching can occur in various nosologies, presenting significant difficulties for diagnosis and treatment, and significantly affect the quality of life of patients (Table 1).

The incidence of chronic pruritus in the general population ranges from 8.4% in a cohort study of 40,000 adults in Norway [11] to 13.9% in a small pilot study in Germany involving 200 adults [12], according to other sources, up to 18.7% [13], 20–30% [1]. According to B. Yalcin and E. Tramer [14], itching was the cause of hospitalizations in elderly patients in 11.5% of cases. In a study by R.A. Norman [15], itching was present in 2/3 of cases in elderly patients, according to H. Van Os-Medendorp [10] - in 29% of patients older than 50 years. In a study of patients in a dermatological outpatient clinic, itching was observed in 60% of cases [16].

In some patients, chronification and amplification of itching on the background of stress are noted. Chronic itching often reveals comorbid relationships with depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorders [17-19].

Itching classification

Itching performs a vital protective function in the body along with pain, being a signal for the effective removal of damaging substances from the skin. Normally, itching is a component of a protective reflex aimed at removing potentially dangerous irritating substances/objects that have fallen on the surface or deep into the skin. Under the conditions of the pathological process, itching can act as: 1) a symptom of the disease, becoming part of the clinical picture in a particular nosology; 2) symptom complex - a syndrome observed in various nosologies; 3) a monosymptom that actually corresponds to an independent dermatological diagnosis of "pruritus" - L.29in ICD-10. In the third case, itching is the most difficult diagnostic and therapeutic problem, since it is assumed that all possible objective dermatological and somatic/neurological causes of its occurrence are excluded. According to J. Rechenberger (1976), itching can be provoked not only by mechanical, electrical or chemical stimuli, but also by emotional stimuli.

Normally, itching is a component of a protective reflex aimed at removing potentially dangerous irritating substances/objects that have fallen on the surface or deep into the skin. Under the conditions of the pathological process, itching can act as: 1) a symptom of the disease, becoming part of the clinical picture in a particular nosology; 2) symptom complex - a syndrome observed in various nosologies; 3) a monosymptom that actually corresponds to an independent dermatological diagnosis of "pruritus" - L.29in ICD-10. In the third case, itching is the most difficult diagnostic and therapeutic problem, since it is assumed that all possible objective dermatological and somatic/neurological causes of its occurrence are excluded. According to J. Rechenberger (1976), itching can be provoked not only by mechanical, electrical or chemical stimuli, but also by emotional stimuli.

In modern studies, the classification of pruritus has been adopted depending on the mechanisms of occurrence: pruritic pruritus [30] (in skin diseases - atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, etc. ), systemic (in the pathology of internal organs - primary biliary cirrhosis, chronic renal failure, Hodgkin's disease, etc.). .), neurological/neuropathic (with compression, injury of the nerve trunks), psychogenic [31], functional [32], idiopathic [33, 34], somatoform [35] (with mental disorders) and multifactorial (with a combination of two or more of the above reasons) [30, 36, 37]. In addition, there are other classifications of itching (Table 2).

), systemic (in the pathology of internal organs - primary biliary cirrhosis, chronic renal failure, Hodgkin's disease, etc.). .), neurological/neuropathic (with compression, injury of the nerve trunks), psychogenic [31], functional [32], idiopathic [33, 34], somatoform [35] (with mental disorders) and multifactorial (with a combination of two or more of the above reasons) [30, 36, 37]. In addition, there are other classifications of itching (Table 2).

Pruritus pathogenesis

The mechanisms of pathogenesis of pruritus are currently not well understood. At the present stage of scientific development, there is evidence of the existence of central neuronal pathways that are not associated with nociceptive analyzers, as well as itch-specific receptors [38, 39] and mediators that mediate the perception of itch. When examining the skin of patients with atopic dermatitis, an increase in neurogenic growth factor was noted [40]. In addition, the role of interleukin-31 and its increase in patients with atopic dermatitis, who often complain of itching, are currently being actively discussed [41, 42]. The use of antibodies to interleukin-31 in a mouse model of atopic dermatitis significantly reduced the level of pruritus [43]. Currently, the role of mediators such as vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), substance P, and endothelin-1 is actively discussed in the pathogenesis of pruritus.

The use of antibodies to interleukin-31 in a mouse model of atopic dermatitis significantly reduced the level of pruritus [43]. Currently, the role of mediators such as vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), substance P, and endothelin-1 is actively discussed in the pathogenesis of pruritus.

An imbalance in the mu-(μ) and kappa-(k) opioid receptor systems in the skin or in the central nervous system is currently suspected as one of the causes of chronic pruritus. Studies have demonstrated the positive effect of systemic kappa-opioid receptor agonists in the treatment of nodular pruritus, paraneoplastic, uremic and cholestatic pruritus [44, 45].

In the brain, sensory, motor, and affective regions are activated at the same time that itching occurs [46].

Therefore, the definition of pruritus can be formulated as follows: a feeling that is accompanied by contralateral activation of the anterior cortex and predominantly unilateral activation of additional motor areas and the lower parietal lobe and which causes scratching of the corresponding skin areas [47] – reflecting the fact that “it is not the skin that itches, and itching occurs in the brain” (Fig. 1) [48].

1) [48].

The involvement of the brain in the pathogenesis of pruritus is obvious, given that a psychological component may be present in each case of pruritus and that a specific psychogenic pruritus is possible, i.e. itching may be psychogenic induced. Opioids and other neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine are involved in this phenomenon (Table 3).

Patients with functional or other pruritus constantly scratch the skin, causing hyperplasia and more intense itching. Scratching temporarily suppresses the sensation of itching; then peripheral and central sensitization occurs [44]. The release of inflammatory mediators during scratching increases the sensitivity of itch receptors (peripheral sensitization), while chronic skin inflammation promotes the process of itching signals in the spinal cord and brain, which leads, respectively, to the sensation of itching of the skin (central sensitization) [30].

At the molecular level, the two-way relationship between the central nervous system and the peripheral pruritic process, caused by stress, has been widely studied [49]. For example, dermal neuropeptides are found in myelinated A-fibers and small unmyelinated C-fibers, including sensory and autonomic fibers. The skin is innervated not only by primary afferent sensory nerves, but also by postganglionic cholinergic, and parasympathetic, and adrenergic, and cholinergic sympathetic nerves. The latter serve not only to conduct stimuli from the skin to the central nervous system, but also participate in efferent "neurosecretion". Thus, emotional stress-induced release of neuropeptides may be pruritic and act on the immune system through humoral factors such as cytokines and antibodies, which regulates neuroendocrine function. Neuropeptides also exert their multiple effects on central regulatory centers that alternately regulate autonomic and behavioral responses.

For example, dermal neuropeptides are found in myelinated A-fibers and small unmyelinated C-fibers, including sensory and autonomic fibers. The skin is innervated not only by primary afferent sensory nerves, but also by postganglionic cholinergic, and parasympathetic, and adrenergic, and cholinergic sympathetic nerves. The latter serve not only to conduct stimuli from the skin to the central nervous system, but also participate in efferent "neurosecretion". Thus, emotional stress-induced release of neuropeptides may be pruritic and act on the immune system through humoral factors such as cytokines and antibodies, which regulates neuroendocrine function. Neuropeptides also exert their multiple effects on central regulatory centers that alternately regulate autonomic and behavioral responses.

In this regard, it is worth mentioning the vicious circle, or the cycle of "itching - scratching - itching." Damage to the skin barrier and subsequent inflammation lead to the development of itching. In the skin, inflammatory cells activate sensory nerves, mast cells, fibroblasts, macrophages (all of which express kappa-opioid receptors). These cells release itch mediators, which further increase inflammation. Along with the activation of sensory fibers, the itch signal is transmitted to the brain; nerves release neuropeptides that increase inflammation (called neurogenic inflammation). The itch signal is transmitted to the brain, causing the scratch reflex. Scratching leads to damage to the skin barrier (excoriations), which further increases inflammation. T-lymphocytes and eosinophils migrate into the skin, releasing pruritogen mediators. Ultimately, sensitization of sensitive nerve fibers and a decrease in the activation threshold occur. Growth factors released by eosinophils lead to the proliferation of nerve fibers. These changes increase the sensitivity of the skin, which becomes even more vulnerable to endo- and exogenous factors. This cycle is difficult to break. The cycle of “itching – scratching – itching” leads to sleep disorders, concentration of attention and perception processes, and interferes with labor activity [30] (Tables 3–5).

In the skin, inflammatory cells activate sensory nerves, mast cells, fibroblasts, macrophages (all of which express kappa-opioid receptors). These cells release itch mediators, which further increase inflammation. Along with the activation of sensory fibers, the itch signal is transmitted to the brain; nerves release neuropeptides that increase inflammation (called neurogenic inflammation). The itch signal is transmitted to the brain, causing the scratch reflex. Scratching leads to damage to the skin barrier (excoriations), which further increases inflammation. T-lymphocytes and eosinophils migrate into the skin, releasing pruritogen mediators. Ultimately, sensitization of sensitive nerve fibers and a decrease in the activation threshold occur. Growth factors released by eosinophils lead to the proliferation of nerve fibers. These changes increase the sensitivity of the skin, which becomes even more vulnerable to endo- and exogenous factors. This cycle is difficult to break. The cycle of “itching – scratching – itching” leads to sleep disorders, concentration of attention and perception processes, and interferes with labor activity [30] (Tables 3–5).

In relation to psychopathology, a depressive clinical state, which has been shown to be associated with elevated levels of corticotropin-releasing hormone, has been suggested to amplify (amplify) the perception of pruritus due to an increase in central neurogenic endogenous opioid levels [19]. This theory is given the main place in the latest study of psychoneuroimmunological connections. For example, acute immobilization stress initiates mast cell degranulation via corticotropin-releasing factor, neurotensin, and substance P in rats [50]. Thus, a common mediator of pruritus, in particular corticotropin-releasing factor, may be involved in stress and depression.

Itching therapy

In the diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for chronic pruritus of the German Dermatological Society, published in 2006 [51], the following drugs are distinguished to reduce the intensity of pruritus: antihistamines, mast cell inhibitors, systemic glucocorticosteroids, opioid receptor agonists, gabapentin, antidepressants, serotonin receptor antagonists , cyclosporine A. Local agents include local anesthetics, topical glucocorticosteroids, capsaicin, cannabinoid receptor antagonists, tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, acetylsalicylic acid, doxepin, zinc, menthol and camphor, mast cell inhibitors.

Local agents include local anesthetics, topical glucocorticosteroids, capsaicin, cannabinoid receptor antagonists, tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, acetylsalicylic acid, doxepin, zinc, menthol and camphor, mast cell inhibitors.

To date, a number of works have been published on the study of modern experimental drugs that have a central antipruritic effect (antagonists and selective agonists of kappa-opioid receptors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)) [52-55] and local antipruritic effects (agonists of vanilloid, cannabinoid receptors, protease inhibitors, and proteinase-activating receptor antagonists) [56, 57]. In particular, palmitoylethanolamine is a selective cannabinoid type 2 receptor agonist and is available in the form of some drugs that are used in the treatment of atopic dermatitis, pruritus of unknown origin, and prurigo. According to research by S. Ständer et. al. [58, 59], there was a reduction in itching up to 60% according to the visual analogue scale. However, complete relief of itching was not achieved.

At the same time, there are reports of regression of psychogenic itching after 2 weeks. against the background of taking antidepressants from the SSRI group, in particular, paroxetine at a dose of 20 mg [60].

According to the literature, the use of selective opioid receptor agonists or SSRIs can achieve a significant (more than 50%) reduction in pruritus in only 32–55% and complete elimination of it in approximately 20% of patients [55]. The study showed a slight difference in the effectiveness of the treatment of chronic itching with antidepressants of the SSRI group (paroxetine, fluvoxamine) in 2 groups of patients, regardless of the presence of mental pathology. Group 1 included patients without mental disorders (n=37), group 2 included patients with various mental pathologies (n=35): depressive disorders, adjustment disorders, anxiety, neurotic, somatoform and dissociative disorders. In the group of patients with mental disorders, the effect of treatment in the form of regression of itching was observed in 71. 4% of cases, in the group of patients without mental disorders - in 64.9%. The differences were not statistically significant, and there was no statistically significant difference between the treatment effects of fluvoxamine and paroxetine in the treatment groups (p=0.206). The mean duration of treatment with paroxetine was 26.3 weeks and with fluvoxamine 21.5 weeks. [55].

4% of cases, in the group of patients without mental disorders - in 64.9%. The differences were not statistically significant, and there was no statistically significant difference between the treatment effects of fluvoxamine and paroxetine in the treatment groups (p=0.206). The mean duration of treatment with paroxetine was 26.3 weeks and with fluvoxamine 21.5 weeks. [55].

Capsaicin, the pungent component of red pepper, is seen as an effective treatment for a variety of pruritic conditions: activation of afferent C-fibers and subsequent reduction of neuropeptides (such as substance P) lowers the threshold for pruritic stimulation [61] – this has been demonstrated in relation to notalgia paresthetica [62, 63] brachioradial pruritus [64, 65] and prurigo nodosum [66]. Cream with local anesthetics (lidocaine, prilocaine) can play an auxiliary role along with other local agents in the treatment of pruritus. G. Yosipovitch [67] demonstrated that the preliminary use of an ointment with local anesthetics (lidocaine, prilocaine) significantly reduced the side effects of capsaicin, such as burning and hyperalgia.

Many non-specific therapeutic agents are used in addition to specific treatments. In all cases of itching, the fundamental importance of supportive care in the form of cold compresses with abundant moisture (topical moisturizing therapy with urea) cannot be ignored. This supportive therapy softens, provides hydration, facilitates the processing of crusts and reduces xerosis, which helps to reduce itching. Menthol products are also useful for relieving itching. If there is a secondary bacterial infection, additional treatment with antibacterial drugs is necessary. Occlusive dressings are recommended to help reduce excoriations. Itchy eruptions, such as prurigo due to chronic itching, can be removed with a laser, cryotherapy, injections of triamcinolone locally into the area of \u200b\u200bthe lesions. Means that play an important role in the treatment of pruritus include phototherapy, ultraviolet radiation - UVB and PUVA therapy (Fig. 2).

The traditional therapeutic approach to the treatment of pruritus is the use of antihistamines, both systemic and local. According to the EAACI (European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology) classification, antihistamines of the 1st generation with sedative action (diphenhydramine, clemastine, chloropyramine, hifenadine) and 2nd generation (non-sedative) antihistamines are distinguished, among which there are metabolized (loratadine, ebastine) and active metabolites - drugs, which enter the body immediately in the form of an active substance (cetirizine, levocetirizine, desloratadine, fexofenadine). There is an opinion that in antihistamines of the 1st generation, the sedative side effect has a positive effect in the treatment of pruritic dermatosis in patients with sleep disorders, however, sedatives (except doxylamine) inhibit the REM sleep phase (rapid eye movement - the phase of rapid eye movements), which leads to to an increase in the duration and intensity of this phase, as a result, sleep becomes intermittent. Antihistamines of the first generation can cause headache, weakness, atropine-like effects: urinary retention, dry mouth, impaired vision and gastrointestinal function.

According to the EAACI (European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology) classification, antihistamines of the 1st generation with sedative action (diphenhydramine, clemastine, chloropyramine, hifenadine) and 2nd generation (non-sedative) antihistamines are distinguished, among which there are metabolized (loratadine, ebastine) and active metabolites - drugs, which enter the body immediately in the form of an active substance (cetirizine, levocetirizine, desloratadine, fexofenadine). There is an opinion that in antihistamines of the 1st generation, the sedative side effect has a positive effect in the treatment of pruritic dermatosis in patients with sleep disorders, however, sedatives (except doxylamine) inhibit the REM sleep phase (rapid eye movement - the phase of rapid eye movements), which leads to to an increase in the duration and intensity of this phase, as a result, sleep becomes intermittent. Antihistamines of the first generation can cause headache, weakness, atropine-like effects: urinary retention, dry mouth, impaired vision and gastrointestinal function. Despite these shortcomings, I generation antihistamines have an advantage in the form of injectable forms. In addition, a number of drugs (for example, hydroxyzine) have anti-anxiety effects. Chloropyramine has an additional anticholinergic effect, which is taken into account in the complex treatment of atopic dermatitis. Cyproheptadine and clemastine also have antiserotonin activity. The question of the lower cost of first generation antihistamines is controversial due to the fact that they act for a short time [68].

Despite these shortcomings, I generation antihistamines have an advantage in the form of injectable forms. In addition, a number of drugs (for example, hydroxyzine) have anti-anxiety effects. Chloropyramine has an additional anticholinergic effect, which is taken into account in the complex treatment of atopic dermatitis. Cyproheptadine and clemastine also have antiserotonin activity. The question of the lower cost of first generation antihistamines is controversial due to the fact that they act for a short time [68].

Antihistamines of the second generation (non-sedative) have a higher affinity for h2-receptors and high specificity, rapid onset of action and duration of effect up to 24 hours, high selectivity of action. Due to the fact that these drugs do not penetrate the blood-brain barrier, they do not cause drowsiness.

Clinical observation

A 42-year-old patient complained of high-intensity itching on the skin of the trunk, which appeared after the use of a combined drug tolperisone containing vitamins of group B. For treatment for 2 days without effect, he independently used antihistamines, topical glucocorticosteroids. A similar episode was observed in a patient six months ago after eating red fish. Heredity is not burdened. Allergy testing has not been done before. Among the concomitant diseases - chronic gastritis, chronic pancreatitis. The skin process is represented by numerous linear excoriations, erythema on the skin of the back, severe skin itching, leading to sleep disturbances. Dermographism red (Fig. 3).

For treatment for 2 days without effect, he independently used antihistamines, topical glucocorticosteroids. A similar episode was observed in a patient six months ago after eating red fish. Heredity is not burdened. Allergy testing has not been done before. Among the concomitant diseases - chronic gastritis, chronic pancreatitis. The skin process is represented by numerous linear excoriations, erythema on the skin of the back, severe skin itching, leading to sleep disturbances. Dermographism red (Fig. 3).

According to laboratory tests, blood counts are within normal limits, total IgE 9.3 IU/ml. In terms of differential diagnosis, the diagnoses of acute urticaria and toxicoderma for vitamins of group B were discussed. After consulting an allergist, the patient was recommended therapy with enterosorbents, antihistamines, 3 injections of dexamethasone were performed (8 mg intramuscularly on the 1st day, 2nd and 3rd days - 4 mg), which stopped the severity of the skin process. To clarify the sensitization, an allergic examination was carried out with the identification of food allergies.

To clarify the sensitization, an allergic examination was carried out with the identification of food allergies.

Among the products that most often cause the development of urticaria and angioedema, it is important to note nuts, fish, seafood, eggs, milk, and soy products. Acute urticaria can also be a manifestation of fruit-latex syndrome (this is a cross-food allergy to some fruits - bananas, pineapples, strawberries, kiwi, mangoes, passion fruit, etc. with sensitization to latex). Latex proteins are similar in structure to many other plant proteins, so a cross-reaction develops. Acute urticaria can also manifest itself as a cross-food allergy with hay fever. Among the drugs that contribute to the development of urticaria and angioedema, there are antibacterial, protein drugs, acetylsalicylic acid, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, muscle relaxants (the patient used a centrally acting muscle relaxant), narcotic analgesics, radiopaque substances, plasma substitutes, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.