Why do brothers fight so much

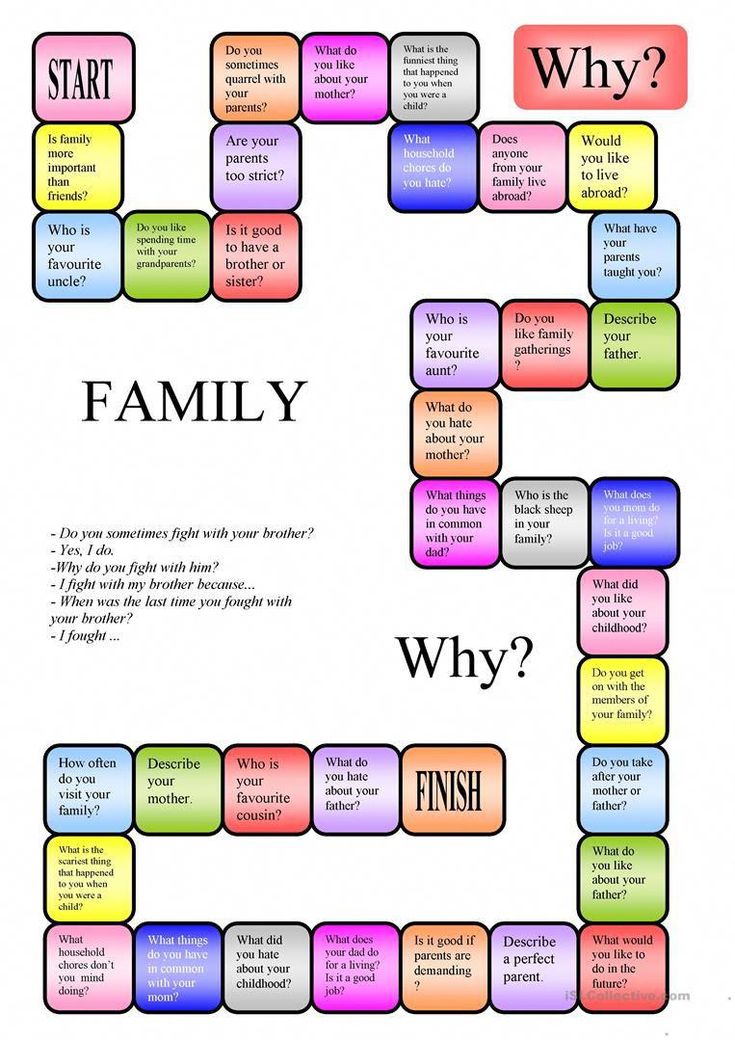

Why siblings fight and what to do about it

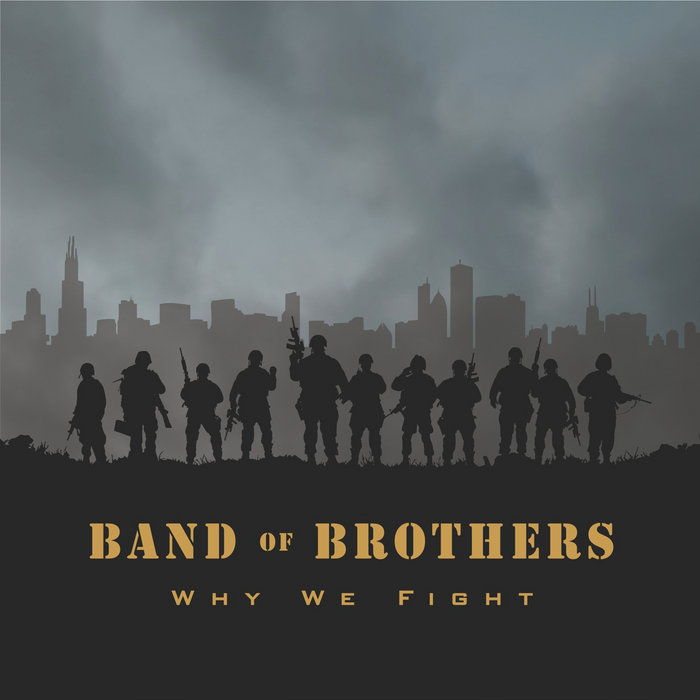

Anyone who grew up with a sibling knows that fighting comes with the territory, but when our own kids get into it, it can be worrying. We wonder, “Are they creating lasting damage to each other?” or “Will they ever get along?” You’ll be relieved to know that, in the vast majority of families, there is no lasting psychological damage caused by sibling fights. Here is some information on why siblings fight with each other and how you can help everyone deal with it more effectively.

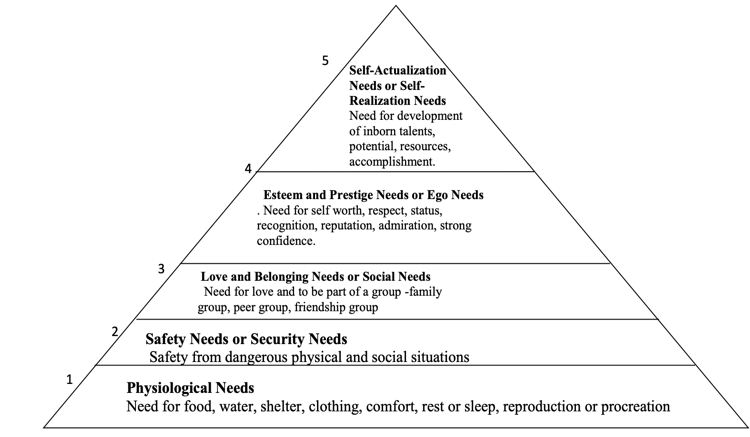

Why siblings fightThe number 1 reason for sibling squabbles is competition for parental attention. Kids need attention from you, and they will do everything (good and bad) in their power to get it. You can shape a lot of behavior by what you pay attention to and how you praise your children. That’s why it is important to give adequate attention to all children, especially for positive behavior.

The more positive behavior is noticed and specifically praised, the less often children will need to act out to get your attention.

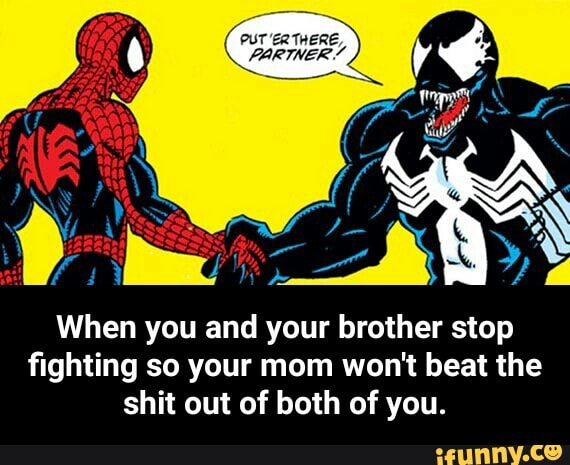

Is it stressful, annoying and exhausting when kids fight? Yes. Yes, it is. But is it important for their development as relational human beings? Also, yes. Through the fine art of fighting, siblings teach each other important concepts like conflict resolution and problem-solving. They also give each other plenty of practice with forgiveness. They might be furious with each other 1 minute and playing nicely the next. That’s a good thing, preparing them for healthy relationships throughout their lifetime. The next time a sibling fight breaks out between your kids, maybe you can say to yourself not, “What’s wrong with them?” but, “Wow! They’re learning so much!” It’s worth a shot, anyway.

How to reduce fightingAs much as we would love to wave a magic wand and prevent all fights, that wishful thinking may not bring us the peace we’re seeking. There are, however, things we can do to lessen the likelihood of fights at predictable times or in predictable circumstances.

There are, however, things we can do to lessen the likelihood of fights at predictable times or in predictable circumstances.

- Notice hunger cues. When kids are tired or hungry, they are more likely to take it out on each other. That’s why it’s always a good idea to have snacks ready to go. Before dinner is a very common time for kids to fight because they are not only hungry, but they are not getting adult attention if you are preparing the meal. You can deal with this by offering satisfying snacks, giving kids tasks to help with dinner or distracting them with something they love, like a show or game.

- Let them know where you are. If you’ve ever been on the phone or in a work meeting at home, you know that kids are never more interested in your whereabouts than when you’re trying to have a conversation with other adults. If possible, check in with kids before calls or meetings to make sure they have everything they need. Let them know when you’ll check in with them again so they don’t feel desperate to reach you in the middle of your important meeting.

- Understand change is stressful. Transitions of any kind can create more tension between siblings, so have some extra grace during changes in school format, activities, seasons, etc., and model and encourage open communication about feelings. Prolonged stressors like the COVID-19 pandemic, a long-term illness or family difficulties can result in kids fighting more with siblings. Encourage kids to come to you with whatever they are facing and actively listen to their concerns.

Remember when we said kids fight for parental attention? Well, if siblings pull you into their dispute, your presence perpetuates the fighting. That’s why you should never assume the role of referee. Instead, try these tips:

- If the kids fighting are fairly well matched, you can call in, “Do you need me to come address the problem?”

- If they say yes, don’t ask who did what, who started it or who ended it.

You are only stepping in to give the kids a break from each other. You can say something like, “You don’t get to play together if you can’t resolve your differences without fighting or getting physical. For the next 10-20 minutes, you’re on your own. No playing together.”

You are only stepping in to give the kids a break from each other. You can say something like, “You don’t get to play together if you can’t resolve your differences without fighting or getting physical. For the next 10-20 minutes, you’re on your own. No playing together.” - If they are squabbling over a toy or an activity, the toy goes in timeout or the activity gets suspended.

- The next time they fight and you ask, “Do you need me to come resolve this?” they will likely look at each other and decide “No!” they can handle it on their own.

- For the most part, you don’t need to teach conflict resolution directly. You can encourage kids to figure it out on their own or face a consequence like lost playtime or lost access to a toy.

It is not uncommon for older siblings to take the blame for all fights with younger siblings. It is natural for you to want to protect young ones, but you need to be mindful of not creating resentment in the older child by making them responsible for every conflict. Often, there is a dynamic to which both kids contribute.

Often, there is a dynamic to which both kids contribute.

- If a younger sibling is always getting into the older sibling’s stuff, precious belongings need to be kept out of reach of the younger sibling.

- If siblings share a room and the younger is messy or destructive, do not make the older one responsible for keeping the room clean.

- Do not reflexively come to the rescue of the younger sibling in arguments.

- Early on, facilitate positive interactions between siblings by having the older child get involved in activities with the younger that are beneficial to the older (e.g., outings, treats, entertainment).

In blended families, adoptive families and foster families, there is a higher risk that kids will complain about favoritism. It is only natural they will be competing for parental attention. Staying calm, consistent and compassionate is the key to building healthy sibling dynamics.

- Don’t take sides or referee. Be a united front as parents.

- Establish together certain things each kid doesn’t have to share.

- In families with stepchildren, consequences should be communicated to each child by their biological parent if the children are older than toddler age.

- Remain calm and dispassionate in addressing expectations and consequences.

- When you give a gift of an electronic, set up the expectation it still belongs to you as a parent, but it is available for the kids to use. That way, you are still in charge of how and when it gets used.

Timeout is called by an adult to address fighting that can’t be resolved by kids.

- Kids and objects can be put in timeout. For example, kids can have a timeout from playing with each other if they can’t get along. If they are arguing over something like a video game, the game can be put in a timeout.

- Timeout ends as soon as a child settles down. The child should be praised for settling. Timeout is not a punishment and it shouldn’t go too long.

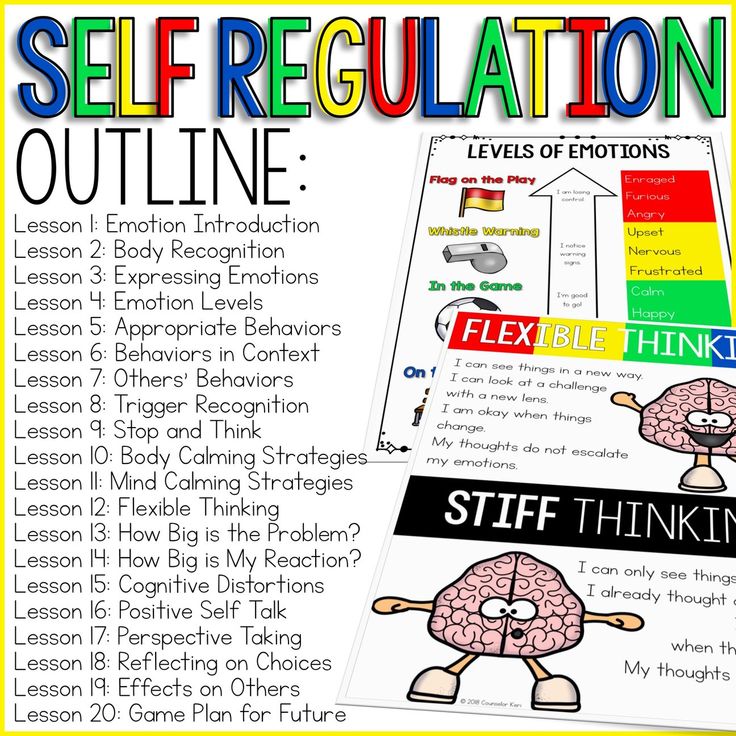

- Kids that have more emotional dysregulation will need more practice (e.g. more timeouts) to learn to settle themselves.

- Cooldown is an opportunity to settle so everyone can think more clearly and is more in control of their actions and words.

- If anyone (kid or adult) needs a cooldown time, they are allowed to call it for themselves. No one can call it for anyone else (e.g., “You need a cooldown!”).

- You can model the behavior to encourage kids to do it (e.g., “I think I need a minute to cool down and I’ll come back when I am thinking more clearly.”).

- Taking a cooldown doesn’t diminish your authority. In fact, you are more likely to lose authority if you get swept up in a heated interaction or if you are trying to reason with emotionally out of control kids.

- Check back in after the cooldown to see how everyone wants to handle the situation. It might be decided that the issue doesn’t need to be rehashed and everyone can move on. It might just be that everyone is in a better place to talk out the conflict more calmly.

If you’ve ever dealt with a meltdown because “He got more fruit snacks than I did!” you know that kids are big on fairness. They will not rest until justice is served in their favor. That is why, very early on, it is good to communicate to children that your family responds to each other based on what each person needs, not based on perceived fairness. Everyone is different and everyone has different needs.

- If there is constant bickering over who gets to sit in a certain seat, who has to do what chores or who gets to pick the meal, you can use even and odd days as an easy way to keep track.

- Another tactic is to give kids who can write a notebook to write down their complaints.

You can set a time to review it if you want or they can just treat it as a journal. Writing down complaints reduces kids’ out-loud whining and eventually, they’ll get tired of even writing down their own complaints.

You can set a time to review it if you want or they can just treat it as a journal. Writing down complaints reduces kids’ out-loud whining and eventually, they’ll get tired of even writing down their own complaints.

If older kids (too old for a babysitter) are home together without parental supervision, do not put one of them in charge of the other. Instead, try this:

- Say “I am going to pay both of you for making sure you are safe and getting along. When I come home, I’m going to ask each of you, did things work well between you.” If either kid complains it didn’t go well, neither gets paid. If they both make it work, they both get paid. It’s a way of putting them in alignment to do what’s best.

The book Siblings without Rivalry is a classic for a reason. It has been republished several times because it continues to offer parents helpful tips and encouragement.

If you have tried everything and there is still constant conflict and stress, then it may be wise to seek professional help from your child’s doctor. Emotional dysregulation is present in a number of childhood health conditions, and your doctor can help determine if there is an underlying health issue that might be affecting behaviors and symptoms.

Contributing Authors

Related Posts

Tips for talking to your kids about sexual orientation

Hitting and biting: what parents need to know

The great cover-up

Food allergies: are more kids allergic to food or are we just more aware?

Bedwetting: What causes it and when to be concerned?

What every parent should know about preventing child trafficking

Constipation: every parent’s favorite topic

What the heck is social jet lag and why it’s harmful to your teen

Anxiety and depression red flags while social distancing

What you should know about elderberry remedies

Sibling Rivalry (for Parents) - Nemours KidsHealth

About Sibling Rivalry

While many kids are lucky enough to become the best of friends with their siblings, it's common for brothers and sisters to fight. (It's also common for them to swing back and forth between adoring and detesting one other!)

(It's also common for them to swing back and forth between adoring and detesting one other!)

Often, sibling rivalry starts even before the second child is born, and continues as the kids grow and compete for everything from toys to attention. As kids reach different stages of development, their evolving needs can significantly affect how they relate to one another.

It can be frustrating and upsetting to watch — and hear — your kids fight with one another. A household that's full of conflict is stressful for everyone. Yet often it's hard to know how to stop the fighting, and or even whether you should get involved at all. But you can take steps to promote peace in your household and help your kids get along.

Why Kids Fight

Many different things can cause siblings to fight. Most brothers and sisters experience some degree of jealousy or competition, and this can flare into squabbles and bickering. But other factors also might influence how often kids fight and how severe the fighting gets. These include:

These include:

- Evolving needs. It's natural for kids' changing needs, anxieties, and identities to affect how they relate to one another. For example, toddlers are naturally protective of their toys and belongings, and are learning to assert their will, which they'll do at every turn. So if a baby brother or sister picks up the toddler's toy, the older child may react aggressively. School-age kids often have a strong concept of fairness and equality, so might not understand why siblings of other ages are treated differently or feel like one child gets preferential treatment. Teenagers, on the other hand, are developing a sense of individuality and independence, and might resent helping with household responsibilities, taking care of younger siblings, or even having to spend time together. All of these differences can influence the way kids fight with one another.

- Individual temperaments. Your kids' individual temperaments — including mood, disposition, and adaptability — and their unique personalities play a large role in how well they get along.

For example, if one child is laid back and another is easily rattled, they may often get into it. Similarly, a child who is especially clingy and drawn to parents for comfort and love might be resented by siblings who see this and want the same amount of attention.

For example, if one child is laid back and another is easily rattled, they may often get into it. Similarly, a child who is especially clingy and drawn to parents for comfort and love might be resented by siblings who see this and want the same amount of attention. - Special needs/sick kids. Sometimes, a child's special needs due to illness or learning/emotional issues may require more parental time. Other kids may pick up on this disparity and act out to get attention or out of fear of what's happening to the other child.

- Role models. The way that parents resolve problems and disagreements sets a strong example for kids. So if you and your spouse work through conflicts in a way that's respectful, productive, and not aggressive, you increase the chances that your children will adopt those tactics when they run into problems with one another. If your kids see you routinely shout, slam doors, and loudly argue when you have problems, they're likely to pick up those bad habits themselves.

Page 1

What to Do When the Fighting Starts

While it may be common for brothers and sisters to fight, it's certainly not pleasant for anyone in the house. And a family can only tolerate a certain amount of conflict. So what should you do when the fighting starts?

Whenever possible, don't get involved. Step in only if there's a danger of physical harm. If you always intervene, you risk creating other problems. The kids may start expecting your help and wait for you to come to the rescue rather than learning to work out the problems on their own. There's also the risk that you — inadvertently — make it appear to one child that another is always being "protected," which could foster even more resentment. By the same token, rescued kids may feel that they can get away with more because they're always being "saved" by a parent.

If you're concerned by the language used or name-calling, it's appropriate to "coach" kids through what they're feeling by using appropriate words. This is different from intervening or stepping in and separating the kids.

This is different from intervening or stepping in and separating the kids.

Even then, encourage them to resolve the crisis themselves. If you do step in, try to resolve problems with your kids, not for them.

When getting involved, here are some steps to consider:

- Separate kids until they're calm. Sometimes it's best just to give them space for a little while and not immediately rehash the conflict. Otherwise, the fight can escalate again. If you want to make this a learning experience, wait until the emotions have died down.

- Don't put too much focus on figuring out which child is to blame. It takes two to fight — anyone who is involved is partly responsible.

- Next, try to set up a "win-win" situation so that each child gains something. When they both want the same toy, perhaps there's a game they could play together instead.

Remember, as kids cope with disputes, they also learn important skills that will serve them for life — like how to value another person's perspective, how to compromise and negotiate, and how to control aggressive impulses.

Page 3

Helping Kids Get Along

Simple things you can do every day to prevent fighting include:

- Set ground rules for acceptable behavior. Tell the kids to keep their hands to themselves and that there's no cursing, no name-calling, no yelling, no door slamming. Solicit their input on the rules — as well as the consequences when they break them. This teaches kids that they're responsible for their own actions, regardless of the situation or how provoked they felt, and discourages any attempts to negotiate regarding who was "right" or "wrong."

- Don't let kids make you think that everything always has to be "fair" and "equal" — sometimes one kid needs more than the other.

- Be proactive in giving your kids one-on-one attention directed to their interests and needs. For example, if one likes to go outdoors, take a walk or go to the park. If another child likes to sit and read, make time for that too.

- Make sure kids have their own space and time to do their own thing — to play with toys by themselves, to play with friends without a sibling tagging along, or to enjoy activities without having to share 50-50.

- Show and tell your kids that, for you, love is not something that comes with limits.

- Let them know that they are safe, important, and loved, and that their needs will be met.

- Have fun together as a family. Whether you're watching a movie, throwing a ball, or playing a board game, you're establishing a peaceful way for your kids to spend time together and relate to each other. This can help ease tensions between them and also keeps you involved. Since parental attention is something many kids fight over, fun family activities can help reduce conflict.

- If your children frequently squabble over the same things (such as video games or dibs on the TV remote), post a schedule showing which child "owns" that item at what times during the week. (But if they keep fighting about it, take the "prize" away altogether.)

- If fights between your school-age kids are frequent, hold weekly family meetings in which you repeat the rules about fighting and review past successes in reducing conflicts.

Consider establishing a program where the kids earn points toward a fun family-oriented activity when they work together to stop battling.

Consider establishing a program where the kids earn points toward a fun family-oriented activity when they work together to stop battling. - Recognize when kids just need time apart from each other and the family dynamics. Try arranging separate play dates or activities for each kid occasionally. And when one child is on a play date, you can spend one-on-one time with another.

Keep in mind that sometimes kids fight to get a parent's attention. In that case, consider taking a time-out of your own. When you leave, the incentive for fighting is gone. Also, when your own fuse is getting short, consider handing the reins over to the other parent, whose patience may be greater at that moment.

Page 4

Getting Professional Help

In a small percentage of families, the conflict between brothers and sisters is so severe that it disrupts daily functioning, or particularly affects kids emotionally or psychologically. In those cases, it's wise to get help from a mental health professional. Seek help for sibling conflict if it:

Seek help for sibling conflict if it:

- is so severe that it's leading to marital problems

- creates a real danger of physical harm to any family member

- is damaging to the self-esteem or psychological well-being of any family member

- may be related to other significant concerns, such as depression

If you have questions about your kids' fighting, talk with your doctor, who can help you determine whether your family might benefit from professional help and refer you to local behavioral health resources.

Quarrels between siblings

Maria Afonina, a child and family psychologist at the National Research Center for Children's Health of the Russian Ministry of Health, tells why quarrels arise between siblings, how to deal with them, and what parents should do.

Growing up next to a brother or sister means having a close person with whom you can play, walk, invent stories, create, share your difficulties and successes, consult, know that you are not alone. However, before truly deep warm feelings appear between children in the same family and they begin to treat each other as a source of joy and support, their relationship will go a long way, on which disputes, reproaches, misunderstandings, mutual insults, rivalry, competition are inevitable. . Sometimes quarrels occur so often that they become a real test of strength for the whole family.

However, before truly deep warm feelings appear between children in the same family and they begin to treat each other as a source of joy and support, their relationship will go a long way, on which disputes, reproaches, misunderstandings, mutual insults, rivalry, competition are inevitable. . Sometimes quarrels occur so often that they become a real test of strength for the whole family.

Why do brothers and sisters quarrel?

1. A common cause of quarrels is competition for the attention of parents : every child wants to be the only one, to receive all the love of mom and dad. Children are jealous, envy, offended, angry, upset, and parents are faced with the difficult task of showing all children in the family that each of them is special and loved.

To do this, it is very important to notice the individual needs and characteristics of each child. For example, you can buy pencils and an album for a drawing lover, and give a connoisseur of fashionable hairstyles a new hairpin and comb. A successful athlete will be happy to hear how he deftly handles the ball, and a future mathematician should be praised for a non-standard or quick solution to a problem.

A successful athlete will be happy to hear how he deftly handles the ball, and a future mathematician should be praised for a non-standard or quick solution to a problem.

It is good to have the opportunity to spend time alone with each child, apart from a brother or sister, in activities that are interesting and necessary for him.

This time does not have to be equal in terms of the total number of minutes or hours, but it must be filled with things that are important for the child. So, you can spend 1.5 hours preparing for a test with your eldest daughter and spend 40 minutes supporting your youngest daughter after a quarrel with a friend.

It is also useful to show children that each member of the family sometimes needs more attention and care in different life periods. For example, a daughter - when she passes exams and moves to a new school, a son - at the stage of preparation for competitions, mom - because she is sick now, dad - he has trouble at work, grandmother - her birthday is coming soon.

2. Parents and other adults themselves can provoke and intensify rivalry by comparing siblings. Sometimes this happens against the background of irritation, fatigue and discontent: “Look at your sister, she has an order on the table, not like you!” But in some cases, comparisons are used as a way of praise: “Your brother spent the whole evening on homework, and you do it in half an hour!”

In communicating with each child in the family, it is important to pay attention only to his personal actions - positive or negative, to remind himself that the behavior of a brother or sister has nothing to do with another child, because each of them is unique. The unifying factor (instead of rivalry) can be common activities that are attractive to all children in the family: preparation for the holidays, travel, joint board games, walks in the park, family dinners on weekends, etc.

3. Conflicts often occur because of violations of personal boundaries . For example, the younger brother is given the older brother's toys without his approval; one sister takes another's clothes without permission, because they suit her very well; the brother eats all the candy from his New Year's present and demands that his sister share it with him. All this causes a feeling of injustice, a desire to defend their territory, to take revenge on a brother or sister, to prove to their parents that they are right.

All this causes a feeling of injustice, a desire to defend their territory, to take revenge on a brother or sister, to prove to their parents that they are right.

Respect for the personal space of everyone in the family will help prevent such disputes.

It is useful to establish a rule: everyone decides how he wants to dispose of his things, when and under what conditions he is ready to share his property with others (or perhaps not), and this choice must be respected.

Signs with inscriptions and symbols (“Do not enter!”, “Private property!”) will help to mark the rules and remind about the borders. You can sometimes involve children in the process of sharing something in common, show the benefits of being willing to share, demonstrate this by example. But in no case should you rush or force - the ability to understand and protect your boundaries will definitely come in handy in adulthood.

4. Conflicts and quarrels between brothers and sisters are one of the ways show their superiority in relations with each other, cope with feelings of inferiority, take revenge, settle scores, try to take a different position in the family. Children (at any age) are just learning to understand their needs and emotions, they cannot always find ways to express them on their own. They are overwhelmed with conflicting feelings - irritation, indignation, anger, resentment at certain actions of other family members side by side with tenderness, sympathy, interest.

Children (at any age) are just learning to understand their needs and emotions, they cannot always find ways to express them on their own. They are overwhelmed with conflicting feelings - irritation, indignation, anger, resentment at certain actions of other family members side by side with tenderness, sympathy, interest.

It is important to recognize the right of children to have ambivalent feelings towards a brother or sister, to give them the opportunity to express them in words and in creativity, to show how emotions can be expressed in socially acceptable and safe ways. Invite a preschooler to draw a picture that depicts his feelings during a quarrel with other family members, and a schoolchild or teenager to write a letter to a sister or brother and express in it all that was unpleasant. Show how you can express feelings and desires in words (“I don’t want you to take my notebooks without permission”).

If a quarrel has already occurred: how to react?

Parents often ask themselves the question: in what cases is adult intervention in a child's conflict necessary, and what controversial situations can brothers and sisters handle on their own? Parents should definitely intervene when quarrels and conflicts are accompanied by violence (physical and / or verbal) or one of the children abuses his power over another.

When helping children to resolve a dispute, it is important to take on the role of a mediator and peacemaker instead of the role of a judge (finding the guilty and imposing punishments) (helping the children calm down, understand what happened, find an acceptable solution together).

In order to stabilize their emotional state after an argument, children can be encouraged to take deep breaths, count to 10 (or 100), beat a pillow, exercise, draw, listen to music, drink water, wash their faces, and go to different rooms. After that, you can start a conversation.

- Invite the participants in the quarrel to express their opinion, express their feelings in words without insults and accusations of the opposite side, and listen to them respectfully.

- Remind everyone that everyone is entitled to all feelings, but not all ways of expressing them in behavior are acceptable.

- Share your vision of the situation (constantly reminding yourself of the mediator's role and remaining neutral), show confidence that the problem can be solved.

- Try not only to resolve a momentary dispute, but also to think about what will help prevent it in the future. As an effective method, you can use brainstorming - invite the children to name as many ways as possible to solve the problem (even the most unusual and fabulous ones are welcome), write them down, choose the most useful and interesting ones together, and put them into practice.

It is important to remember that children can cope with light quarrels without the help of adults if they know for sure that their parents have noticed the conflict and are fully confident in their ability to resolve it on their own. Simple phrases will help to remind you of this: “I hear that you do not want to give in to each other. I suggest you find a solution that suits everyone", "I remember that you used to be able to agree. So, now everything will definitely work out", "I'll be in the next room. Tell me later what you came up with, I'm very interested."

Quarrels are not always bad

There are positive aspects to sibling rivalry. Any quarrel means that there is a connection, interaction between children in the family. In conflict, each time they choose not to break contact with each other and make an effort to stay together.

Any quarrel means that there is a connection, interaction between children in the family. In conflict, each time they choose not to break contact with each other and make an effort to stay together.

Conflicts and disputes teach to formulate, argue, defend and defend one's opinion, express one's feelings, listen to the point of view and feelings of the interlocutor and respect them. They show how to solve problems, find a compromise and negotiate, make children (and adults too) more resilient and stress-resistant.

Photo: Collection/iStock

Brothers and sisters often quarrel and quarrel: why and what to do

Postutopia

August 16, 2021

Follow us on Telegram

IN THE OPINION OF ROSCOMNADZOR, "UTOPIA" IS A PROJECT OF THE CENTER "NO TO VIOLENCE", WHICH, IN THE OPINION OF THE MINISTRY OF JUSTICE, FUNCTIONS OF FOREIGN AGENT

Why not?

Briefly

Children growing up in the same family are often in conflict with each other. They may fight, argue, ruin each other's things, or show aggression. To a certain extent, this is normal and even inevitable - as conflicts between people with different needs and views on life are inevitable. "Utopia" figured out where the line between conflicts and violence between brothers and sisters, how to behave to parents and how to perceive the aggression of children.

They may fight, argue, ruin each other's things, or show aggression. To a certain extent, this is normal and even inevitable - as conflicts between people with different needs and views on life are inevitable. "Utopia" figured out where the line between conflicts and violence between brothers and sisters, how to behave to parents and how to perceive the aggression of children.

Brothers and sisters of common parents are brought together by the family with its public and unspoken rules and the same or similar age. This makes it easier to understand each other, but at the same time envy, competition and jealousy arise, explains psychologist Margarita Kononova.

After the birth of a brother or sister, the eldest child loses the exclusive attention of the parents. For objective reasons, they often spend more time with the baby, which can offend and hurt the older child, especially if he was not prepared for changes in the family.

Relationships between children are also affected by life in the same territory. To reduce stress, it is not so much the presence of separate rooms that is important, but the distribution of space. Each member of the family, whether it be an adult or a small one, should have its own inviolable place, for example, a toy box, the psychologist adds.

To reduce stress, it is not so much the presence of separate rooms that is important, but the distribution of space. Each member of the family, whether it be an adult or a small one, should have its own inviolable place, for example, a toy box, the psychologist adds.

In 2007, Professor Sofia Nartova-Bochaver conducted an expert survey among practicing psychologists. She asked them what typical conflict situations arise in children at different ages. Mental Health Center psychologist and conflict psychology researcher Natalya Gorlova highlighted in this work the features of the relationship between brothers and sisters.

In kindergarten, they compete for parental attention and possession of things, such as toys or other entertainment. In the lower grades, conflicts begin on the basis of interests and opinions and the struggle for the attention of other significant adults - grandparents, aunts and uncles. Adolescents, in addition to this, have everyday requirements for each other: the distribution of household duties and their own rules of conduct. For example, if one wants to be quiet and the other is constantly playing music, this can cause constant arguments.

For example, if one wants to be quiet and the other is constantly playing music, this can cause constant arguments.

“Aggressiveness is basically normal. It doesn't even matter if you're a brother or a sister. We will always be dissatisfied with something, we will want different things or claim the same thing, we will always dislike something in another person, ”Kononova notes. At the same time, with growing up, brothers and sisters often have expectations of support and help to each other.

When forced to be parents

Parents can stir up conflicts, consciously or unconsciously, by pushing children against each other. If one of them is constantly accused or humiliated, the first one will repeat after adults, even if he did not initially experience aggression towards his brother or sister.

Sometimes the older one is made responsible for the younger one and asked to be a parent or babysitter. At the same time, the elder himself remains a child and may not want or know what to do. Because of the inability to refuse a parent, irritation accumulates, which can be taken out on a younger brother or sister.

Because of the inability to refuse a parent, irritation accumulates, which can be taken out on a younger brother or sister.

“There is such a psychological mechanism – substitution. When I cannot express aggression against the one who causes it, I find another object on which I can express this aggression. The sibling bias happens because I'm actually angry at my parents. They demand something from me,” explains Kononova. “Younger children may lack the attention of their parents.”

Evgenia Shatunova recalls that the birth of her younger sister aroused her curiosity and at the same time she didn't know what to expect. Almost immediately, they began to leave her with the baby for a short time. For example, when mom was doing something in another room or she needed to go to the store. One of these duties was the need to keep her sister a bottle of water.

“I was 10 and I did it because I couldn't refuse. It was long and very boring. And I hit my sister on the gums with a bottle so that she would cry. Then my mother came back, and I could leave, ”says Evgenia. This happened regularly, although she had no desire to harm a small child.

And I hit my sister on the gums with a bottle so that she would cry. Then my mother came back, and I could leave, ”says Evgenia. This happened regularly, although she had no desire to harm a small child.

When the younger sister was three years old, Eugenia was regularly left with her. Mom tried to go to work and returned late, so the children spent most of the time with each other. The younger sister wanted attention, and she often pestered Evgenia. She showed that she could behave as she liked and she would not get anything for it: her mother was still at work.

Sister painted Eugenia's notebooks, followed her on her heels, pestered her with conversations, scandals, whims. It was impossible to calmly read a book, because it was taken away, or go about your business, because they immediately began to interfere. From time to time, Evgenia locked herself in the bathroom, but this did not really help, because her sister began to scream and knock on the door.

It was pointless to say something to mother - she did not want to deal with conflicts between children, and the eldest was always considered guilty. “Once I tried to show my sister that her behavior was wrong and pretended to cry. She didn't react at all and just watched in silence. At that moment, my mother came and saw [what had happened]. Because I mock my sister, I was punished.”

“Once I tried to show my sister that her behavior was wrong and pretended to cry. She didn't react at all and just watched in silence. At that moment, my mother came and saw [what had happened]. Because I mock my sister, I was punished.”

At the age of 16, Evgenia left home, and this had a positive effect on the relationship between the sisters. They began to see each other less often, and the meetings were rather festive. Evgenia took her sister to the rides, she could give a toy. Since they were further physically, all sorts of conflicts ceased, over time, their communication became quite close.

A strong desire to hurt

Conflicts themselves are a neutral concept. What matters is how they are resolved: through aggression, violence or constructive dialogue. The first two concepts differ in intentions. An aggressive reaction occurs spontaneously, it is uncontrollable and has no purpose to harm another. Violence - pursues a specific goal: to hurt the offender, make him suffer or take revenge on him.

Regarding brothers and sisters, according to Natalia Gorlova, it is appropriate to talk not about violence, but about conflicts and ways to resolve them. She clarifies that it is wrong to assume that brothers and sisters always use violence by default in conflict. If one child manipulates another, uses him for his own purposes, then this is an escalation, an increase in contradictions between the parties.

Young children have no intention to harm, and what we adults perceive as aggression is the child's way of getting what he wants. If a child cannot get something, does not know how to explain something in words, lacks experience and skills, and does not know how to cope with the situation, then there is a natural impulse for him to show aggression.

A still from the film "Brother" The peculiarities of the course of conflicts between brothers and sisters and, in general, the relationship between them depend on the culture of the family. If adults resolve conflicts by violent means, then this will become the norm for children. In the same way, they will resort to insults, physical aggression, they may shout at each other. Conversely, if it is customary in the family to calmly discuss problems and seek compromises, then children will learn similar patterns of behavior.

In the same way, they will resort to insults, physical aggression, they may shout at each other. Conversely, if it is customary in the family to calmly discuss problems and seek compromises, then children will learn similar patterns of behavior.

Psychologist Kononova believes that the main responsibility for violence and aggression between brothers and sisters lies with the parents. A child differs from an adult in that he is not always able to track his feelings and acts immediately. “When a child begins to show violence with words, deeds, hands, it is important to say “stop”. Stop him and help him realize what is happening, what he really wants. Why is this already moving to the brink of violence, Kononova adds. - An isolated case is not yet a cause for concern, but a reason for conversation, explanations. It is worth sounding the alarm when violence occurs regularly and affects the well-being of children, their productivity and interaction with society.

Enemies (not) for life

Even if violence between brothers and sisters occurs spontaneously and is not due to events occurring within the family, it is the parents who should understand this, psychologists are convinced. The injured child needs protection, while the attacker needs help to learn to behave differently. If you cannot solve the problem on your own, you will need to contact specialists (psychologists, psychiatrists). But this is also the responsibility of adults.

The injured child needs protection, while the attacker needs help to learn to behave differently. If you cannot solve the problem on your own, you will need to contact specialists (psychologists, psychiatrists). But this is also the responsibility of adults.

“Until a certain age, parents can intervene, and then it is worth giving children the opportunity to resolve conflicts themselves. Of course, it’s good to show how to do it and introduce a cultural norm,” continues Gorlova.

By themselves, children will not learn to compromise and negotiate, they will not learn why it is wrong to insult or beat a brother or sister. Models of behavior are transmitted to them by adults, who, in a good way, should also have developed conflict competence. Children can learn this not only from their parents, but also from other relatives or, for example, from school teachers.

The consequences of violence experienced by a brother or sister are very individual and depend on many factors: what exactly happened to the child, for how long, whether there was a supportive environment.