Cognitive distortion activities

22 Examples & Worksheets (& PDF)

We tend to trust what goes on in our brains. After all, if you can’t trust your own brain, what can you trust?

Generally, this is a good thing—our brain has been wired to alert us to danger, attract us to potential mates, and find solutions to the problems we encounter every day.

However, there are some occasions when you may want to second guess what your brain is telling you. It’s not that your brain is purposely lying to you, it’s just that it may have developed some faulty or non-helpful connections over time.

It can be surprisingly easy to create faulty connections in the brain. Our brains are predisposed to making connections between thoughts, ideas, actions, and consequences, whether they are truly connected or not.

This tendency to make connections where there is no true relationship is the basis of a common problem when it comes to interpreting research: the assumption that because two variables are correlated, one causes or leads to the other. The refrain “correlation does not equal causation!” is a familiar one to any student of psychology or the social sciences.

It is all too easy to view a coincidence or a complicated relationship and make false or overly simplistic assumptions in research—just as it is easy to connect two events or thoughts that occur around the same time when there are no real ties between them.

There are many terms for this kind of mistake in social science research, complete with academic jargon and overly complicated phrasing. In the context of our thoughts and beliefs, these mistakes are referred to as “cognitive distortions.”

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will provide you with a detailed insight into Positive CBT and will give you additional tools to address cognitive distortions in your therapy or coaching.

This Article Contains:

- What are Cognitive Distortions?

- Experts in Cognitive Distortions: Aaron Beck and David Burns

- A List of the Most Common Cognitive Distortions

- Changing Your Thinking: Examples of Techniques to Combat Cognitive Distortions

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What are Cognitive Distortions?

Cognitive distortions are biased perspectives we take on ourselves and the world around us. They are irrational thoughts and beliefs that we unknowingly reinforce over time.

They are irrational thoughts and beliefs that we unknowingly reinforce over time.

These patterns and systems of thought are often subtle–it’s difficult to recognize them when they are a regular feature of your day-to-day thoughts. That is why they can be so damaging since it’s hard to change what you don’t recognize as something that needs to change!

Cognitive distortions come in many forms (which we’ll cover later in this piece), but they all have some things in common.

All cognitive distortions are:

- Tendencies or patterns of thinking or believing;

- That are false or inaccurate;

- And have the potential to cause psychological damage.

It can be scary to admit that you may fall prey to distorted thinking. You might be thinking, “There’s no way I am holding on to any blatantly false beliefs!” While most people don’t suffer in their daily lives from these kinds of cognitive distortions, it seems that no one can completely escape these distortions.

If you’re human, you have likely fallen for a few of the numerous cognitive distortions at one time or another. The difference between those who occasionally stumble into a cognitive distortion and those who struggle with them on a more long-term basis is the ability to identify and modify or correct these faulty patterns of thinking.

As with many skills and abilities in life, some are far better at this than others–but with practice, you can improve your ability to recognize and respond to these distortions.

These distortions have been shown to relate positively to symptoms of depression, meaning that where cognitive distortions abound, symptoms of depression are likely to occur as well (Burns, Shaw, & Croker, 1987).

In the words of the renowned psychiatrist and researcher David Burns:

“I suspect you will find that a great many of your negative feelings are in fact based on such thinking errors.”

Errors in thinking, or cognitive distortions, are particularly effective at provoking or exacerbating symptoms of depression. It is still a bit ambiguous as to whether these distortions cause depression or depression brings out these distortions (after all, correlation does not equal causation!) but it is clear that they frequently go hand-in-hand.

It is still a bit ambiguous as to whether these distortions cause depression or depression brings out these distortions (after all, correlation does not equal causation!) but it is clear that they frequently go hand-in-hand.

Much of the knowledge around cognitive distortions come from research by two experts: Aaron Beck and David Burns. Both are prominent in the fields of psychiatry and psychotherapy.

Experts in Cognitive Distortions: Aaron Beck and David Burns

If you dig any deeper into cognitive distortions and their role in depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues, you will find two names over and over again: Aaron Beck and David Burns.

These two psychologists literally wrote the book(s) on depression, cognitive distortions, and the treatment of these problems.

Aaron Beck

Aaron Beck. Image Retrieved by URL.

Aaron Beck began his career at Yale Medical School, where he graduated in 1946 (GoodTherapy, 2015). His required rotations in psychiatry during his residency ignited his passion for research on depression, suicide, and effective treatment.

In 1954, he joined the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Psychiatry, where he still holds the position of Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry.

In addition to his prodigious catalog of publications, Beck founded the Beck Initiative to teach therapists how to conduct cognitive therapy with their patients–an endeavor that has helped cognitive therapy grow into the therapy juggernaut that it is today.

Beck also applied his knowledge as a member or consultant for the National Institute of Mental Health, an editor for several peer-reviewed journals, and lectures and visiting professorships at various academic institutions throughout the world (GoodTherapy, 2015).

While there are clearly many honors, awards, and achievements Beck may be known for, perhaps his greatest contribution to the field of psychology is his role in the development of cognitive therapy.

Beck developed the basis for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, or CBT, when he noticed that many of his patients struggling with depression were operating on false assumptions and distorted thinking (GoodTherapy, 2015). He connected these distorted thinking patterns with his patients’ symptoms and hypothesized that changing their thinking could change their symptoms.

He connected these distorted thinking patterns with his patients’ symptoms and hypothesized that changing their thinking could change their symptoms.

This is the foundation of CBT – the idea that our thought patterns and deeply held beliefs about ourselves and the world around us drive our experiences. This can lead to mental health disorders when they are distorted but can be modified or changed to eliminate troublesome symptoms.

In line with his general research focus, Beck also developed two important scales that are among some of the most used scales in psychology: the Beck Depression Inventory and the Beck Hopelessness Scale. These scales are used to evaluate symptoms of depression and risk of suicide and are still applied decades after their original development (GoodTherapy, 2015).

David Burns

Another big name in depression and treatment research, Dr. David Burns, also spent some time learning and developing his skills at the University of Pennsylvania – it seems that UPenn is particularly good at producing future leaders in psychology!

Burns graduated from Stanford University School of Medicine and moved on to the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, where he completed his psychiatry residency and cemented his interest in the treatment of mental health disorders (Feeling Good, n. d.).

d.).

He is currently serving as a Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Stanford University School of Medicine, in addition to continuing his research on treating depression and training therapists to conduct effective psychotherapy sessions (Feeling Good, n.d.). Much of his work is based on Beck’s research revealing the potential impacts of distorted thinking and suggesting ways to correct this thinking.

He is perhaps most well known outside of strictly academic circles for his worldwide best-selling book Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy. This book has sold more than 4 million copies within the United States alone and is often recommended by therapists to their patients struggling with depression (Summit for Clinical Excellence, n.d.).

This book outlines Burns’ approach to treating depression, which mostly focuses on identifying, correcting, and replacing distorted systems and patterns of thinking. If you are interested in learning more about this book, you can find it on Amazon with over 1,400 reviews to help you evaluate its effectiveness.

To hear more about Burns’ work in the treatment of depression, check out his TED talk on the subject below.

As Burns discusses in the above video, his studies of depression have also influenced the studies around joy and self-esteem. The most researched form of psychotherapy right now is covered by his book, Feeling Good, aimed at providing tools to the general public.

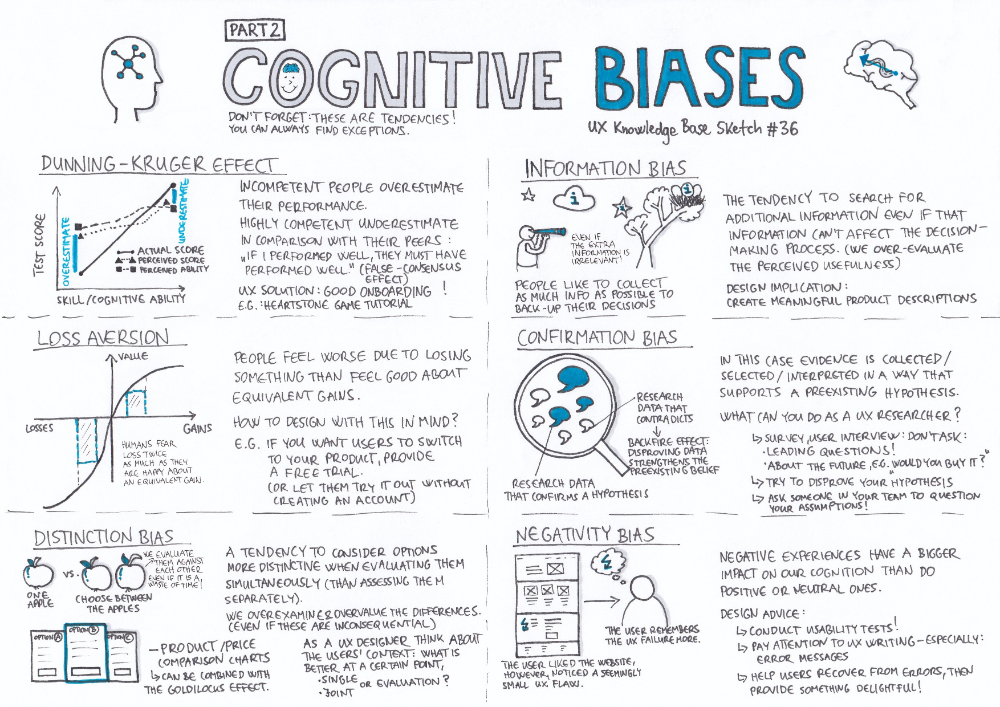

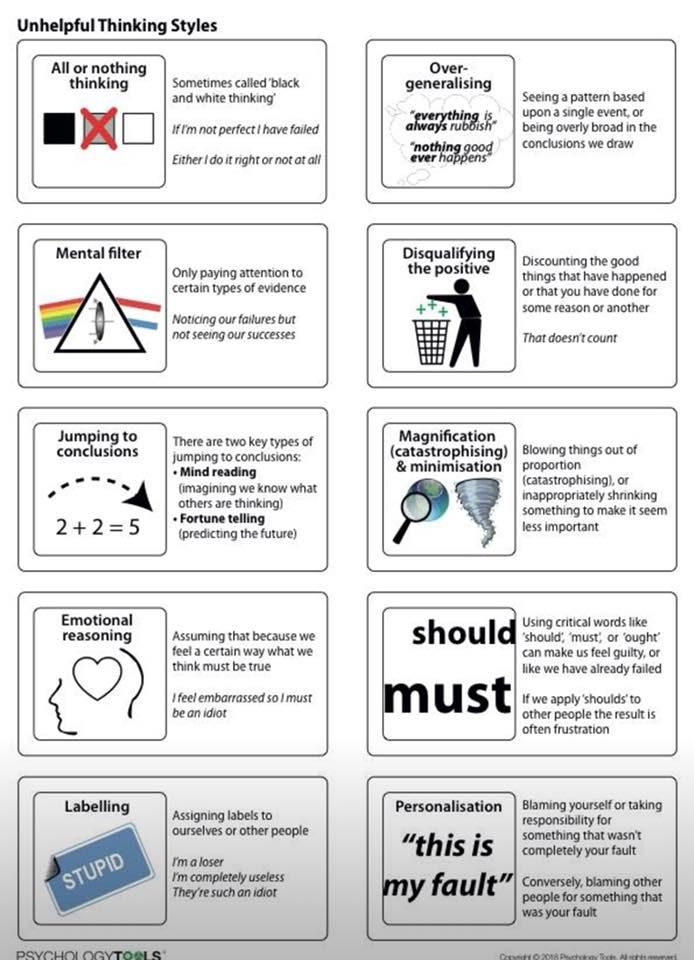

A List of the Most Common Cognitive Distortions

Beck and Burns are not the only two researchers who have dedicated their careers to learn more about depression, cognitive distortions, and treatment for these conditions.

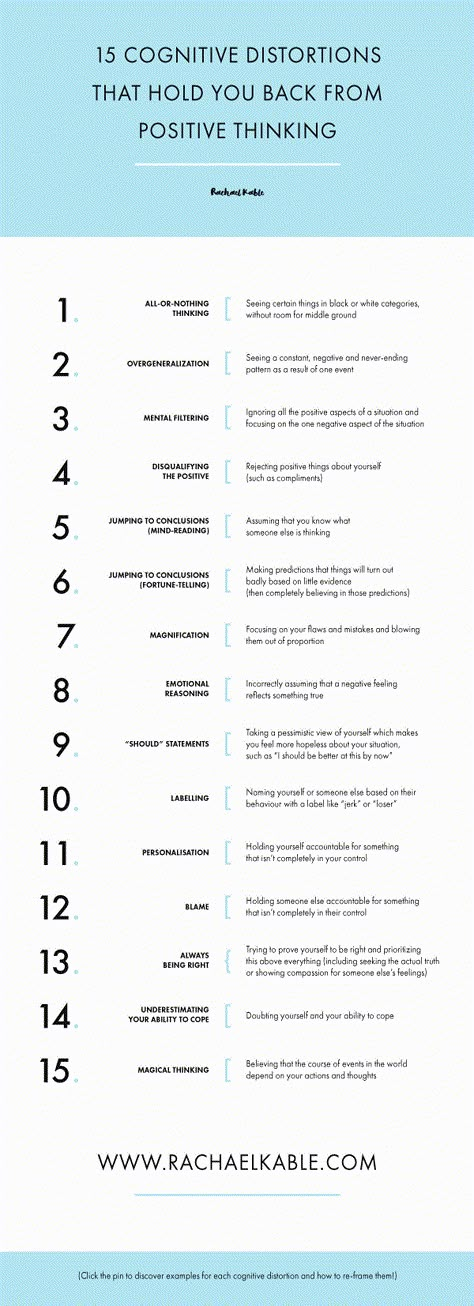

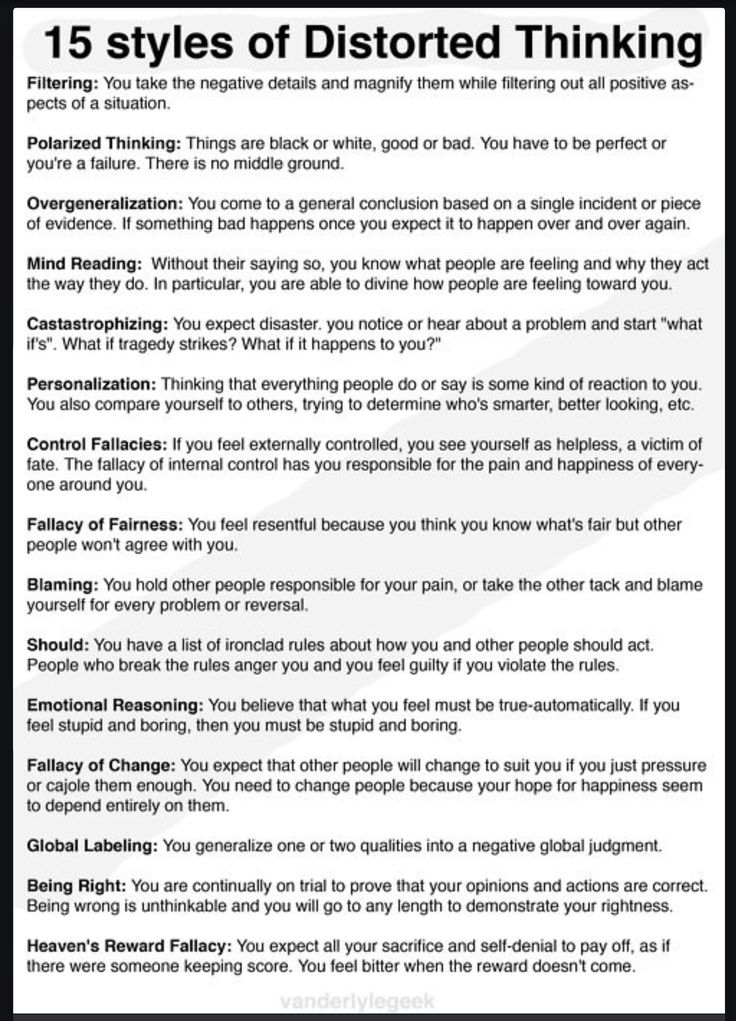

There are many others who have picked up the torch for this research, often with their own take on cognitive distortions. As such, there are numerous cognitive distortions floating around in the literature, but we’ll limit this list to the most common sixteen.

As such, there are numerous cognitive distortions floating around in the literature, but we’ll limit this list to the most common sixteen.

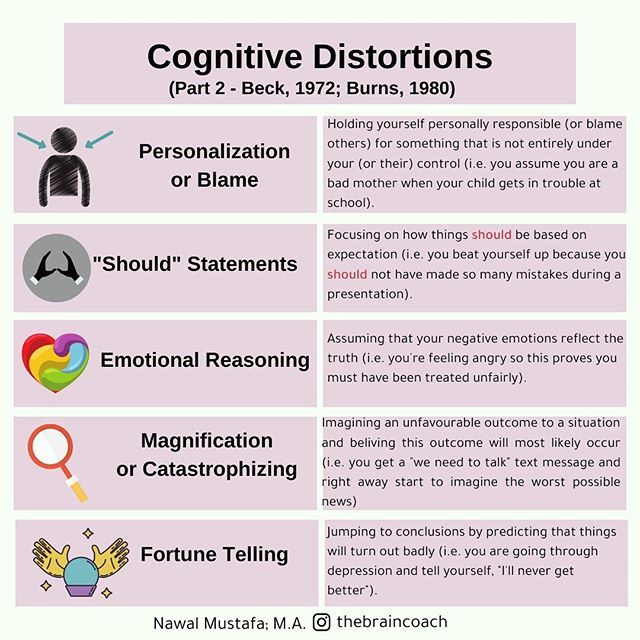

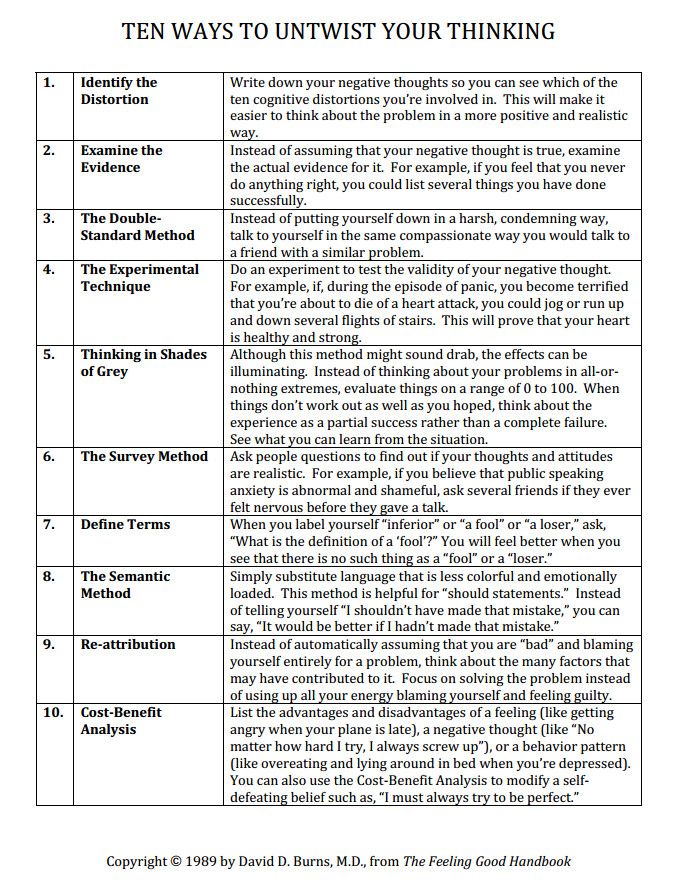

The first eleven distortions come straight from Burns’ Feeling Good Handbook (1989).

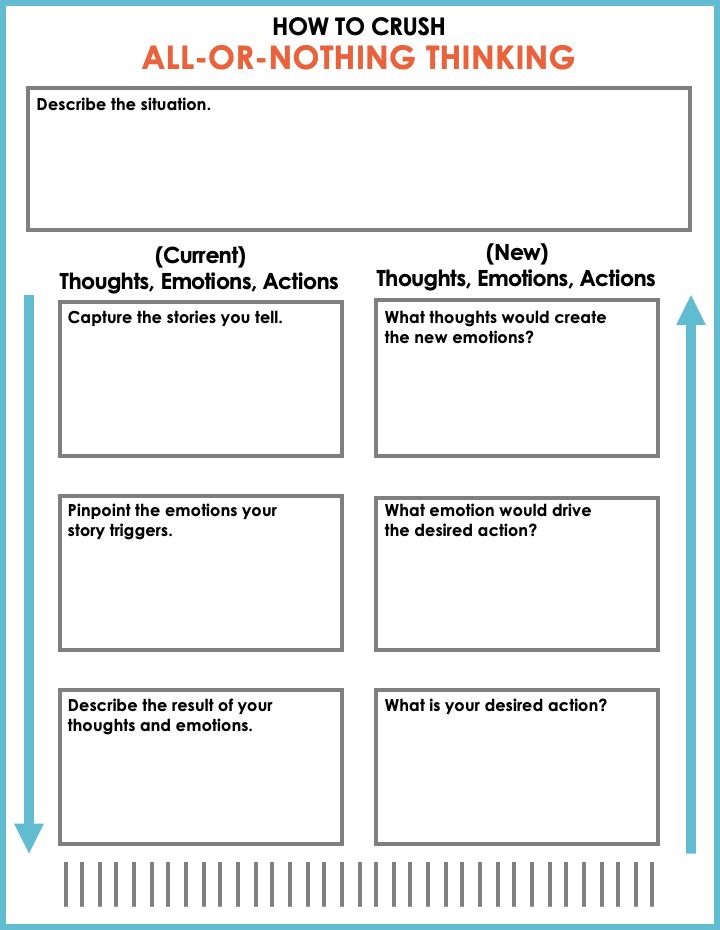

1. All-or-Nothing Thinking / Polarized Thinking

Also known as “Black-and-White Thinking,” this distortion manifests as an inability or unwillingness to see shades of gray. In other words, you see things in terms of extremes – something is either fantastic or awful, you believe you are either perfect or a total failure.

2. Overgeneralization

This sneaky distortion takes one instance or example and generalizes it to an overall pattern. For example, a student may receive a C on one test and conclude that she is stupid and a failure. Overgeneralizing can lead to overly negative thoughts about yourself and your environment based on only one or two experiences.

3. Mental Filter

Similar to overgeneralization, the mental filter distortion focuses on a single negative piece of information and excludes all the positive ones. An example of this distortion is one partner in a romantic relationship dwelling on a single negative comment made by the other partner and viewing the relationship as hopelessly lost, while ignoring the years of positive comments and experiences.

An example of this distortion is one partner in a romantic relationship dwelling on a single negative comment made by the other partner and viewing the relationship as hopelessly lost, while ignoring the years of positive comments and experiences.

The mental filter can foster a decidedly pessimistic view of everything around you by focusing only on the negative.

4. Disqualifying the Positive

On the flip side, the “Disqualifying the Positive” distortion acknowledges positive experiences but rejects them instead of embracing them.

For example, a person who receives a positive review at work might reject the idea that they are a competent employee and attribute the positive review to political correctness, or to their boss simply not wanting to talk about their employee’s performance problems.

This is an especially malignant distortion since it can facilitate the continuation of negative thought patterns even in the face of strong evidence to the contrary.

5.

Jumping to Conclusions – Mind Reading

Jumping to Conclusions – Mind ReadingThis “Jumping to Conclusions” distortion manifests as the inaccurate belief that we know what another person is thinking. Of course, it is possible to have an idea of what other people are thinking, but this distortion refers to the negative interpretations that we jump to.

Seeing a stranger with an unpleasant expression and jumping to the conclusion that they are thinking something negative about you is an example of this distortion.

6. Jumping to Conclusions – Fortune Telling

A sister distortion to mind reading, fortune telling refers to the tendency to make conclusions and predictions based on little to no evidence and holding them as gospel truth.

One example of fortune-telling is a young, single woman predicting that she will never find love or have a committed and happy relationship based only on the fact that she has not found it yet. There is simply no way for her to know how her life will turn out, but she sees this prediction as fact rather than one of several possible outcomes.

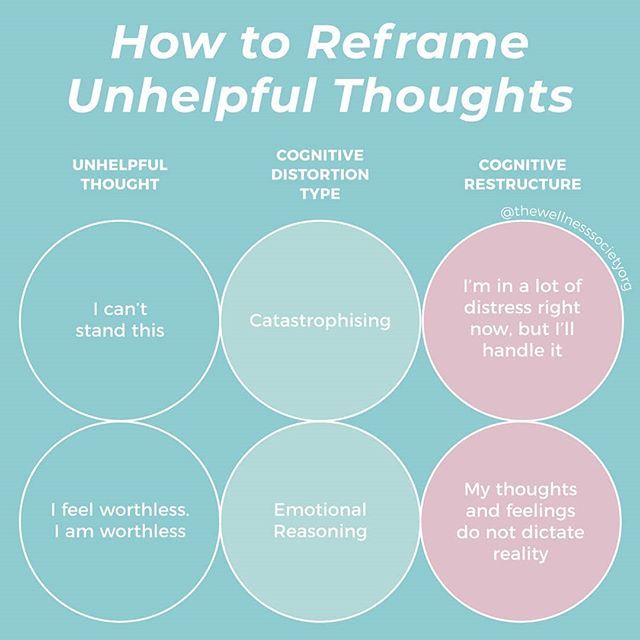

7. Magnification (Catastrophizing) or Minimization

Also known as the “Binocular Trick” for its stealthy skewing of your perspective, this distortion involves exaggerating or minimizing the meaning, importance, or likelihood of things.

An athlete who is generally a good player but makes a mistake may magnify the importance of that mistake and believe that he is a terrible teammate, while an athlete who wins a coveted award in her sport may minimize the importance of the award and continue believing that she is only a mediocre player.

8. Emotional Reasoning

This may be one of the most surprising distortions to many readers, and it is also one of the most important to identify and address. The logic behind this distortion is not surprising to most people; rather, it is the realization that virtually all of us have bought into this distortion at one time or another.

Emotional reasoning refers to the acceptance of one’s emotions as fact. It can be described as “I feel it, therefore it must be true. ” Just because we feel something doesn’t mean it is true; for example, we may become jealous and think our partner has feelings for someone else, but that doesn’t make it true. Of course, we know it isn’t reasonable to take our feelings as fact, but it is a common distortion nonetheless.

” Just because we feel something doesn’t mean it is true; for example, we may become jealous and think our partner has feelings for someone else, but that doesn’t make it true. Of course, we know it isn’t reasonable to take our feelings as fact, but it is a common distortion nonetheless.

Relevant: What is Emotional Intelligence? + 18 Ways to Improve It

9. Should Statements

Another particularly damaging distortion is the tendency to make “should” statements. Should statements are statements that you make to yourself about what you “should” do, what you “ought” to do, or what you “must” do. They can also be applied to others, imposing a set of expectations that will likely not be met.

When we hang on too tightly to our “should” statements about ourselves, the result is often guilt that we cannot live up to them. When we cling to our “should” statements about others, we are generally disappointed by their failure to meet our expectations, leading to anger and resentment.

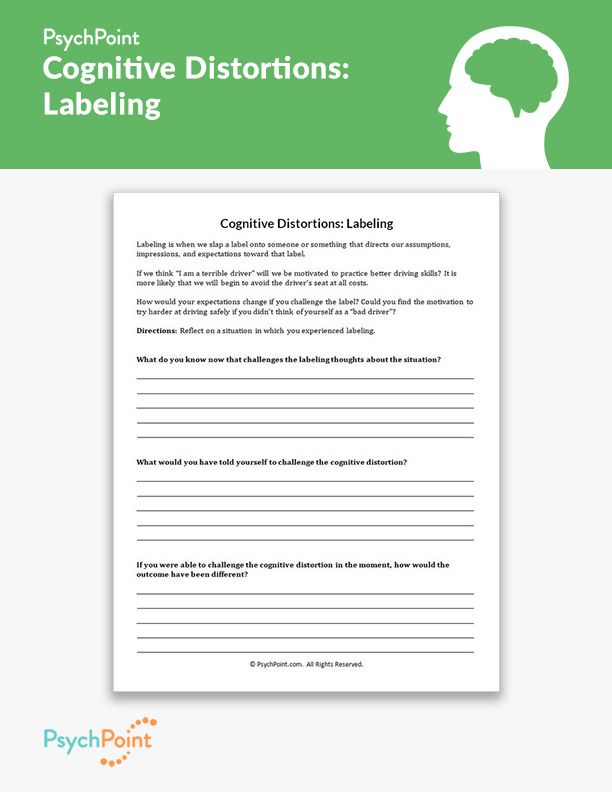

10. Labeling and Mislabeling

These tendencies are basically extreme forms of overgeneralization, in which we assign judgments of value to ourselves or to others based on one instance or experience.

For example, a student who labels herself as “an utter fool” for failing an assignment is engaging in this distortion, as is the waiter who labels a customer “a grumpy old miser” if he fails to thank the waiter for bringing his food. Mislabeling refers to the application of highly emotional, loaded, and inaccurate or unreasonable language when labeling.

11. Personalization

As the name implies, this distortion involves taking everything personally or assigning blame to yourself without any logical reason to believe you are to blame.

This distortion covers a wide range of situations, from assuming you are the reason a friend did not enjoy the girls’ night out, to the more severe examples of believing that you are the cause for every instance of moodiness or irritation in those around you.

In addition to these basic cognitive distortions, Beck and Burns have mentioned a few others (Beck, 1976; Burns, 1980):

12. Control Fallacies

A control fallacy manifests as one of two beliefs: (1) that we have no control over our lives and are helpless victims of fate, or (2) that we are in complete control of ourselves and our surroundings, giving us responsibility for the feelings of those around us. Both beliefs are damaging, and both are equally inaccurate.

No one is in complete control of what happens to them, and no one has absolutely no control over their situation. Even in extreme situations where an individual seemingly has no choice in what they do or where they go, they still have a certain amount of control over how they approach their situation mentally.

13. Fallacy of Fairness

While we would all probably prefer to operate in a world that is fair, the assumption of an inherently fair world is not based in reality and can foster negative feelings when we are faced with proof of life’s unfairness.

A person who judges every experience by its perceived fairness has fallen for this fallacy, and will likely feel anger, resentment, and hopelessness when they inevitably encounter a situation that is not fair.

14. Fallacy of Change

Another ‘fallacy’ distortion involves expecting others to change if we pressure or encourage them enough. This distortion is usually accompanied by a belief that our happiness and success rests on other people, leading us to believe that forcing those around us to change is the only way to get what we want.

A man who thinks “If I just encourage my wife to stop doing the things that irritate me, I can be a better husband and a happier person” is exhibiting the fallacy of change.

15. Always Being Right

Perfectionists and those struggling with Imposter Syndrome will recognize this distortion – it is the belief that we must always be right. For those struggling with this distortion, the idea that we could be wrong is absolutely unacceptable, and we will fight to the metaphorical death to prove that we are right.

For example, the internet commenters who spend hours arguing with each other over an opinion or political issue far beyond the point where reasonable individuals would conclude that they should “agree to disagree” are engaging in the “Always Being Right” distortion. To them, it is not simply a matter of a difference of opinion, it is an intellectual battle that must be won at all costs.

16. Heaven’s Reward Fallacy

This distortion is a popular one, and it’s easy to see myriad examples of this fallacy playing out on big and small screens across the world. The “Heaven’s Reward Fallacy” manifests as a belief that one’s struggles, one’s suffering, and one’s hard work will result in a just reward.

It is obvious why this type of thinking is a distortion – how many examples can you think of, just within the realm of your personal acquaintances, where hard work and sacrifice did not pay off?

Sometimes no matter how hard we work or how much we sacrifice, we will not achieve what we hope to achieve. To think otherwise is a potentially damaging pattern of thought that can result in disappointment, frustration, anger, and even depression when the awaited reward does not materialize.

To think otherwise is a potentially damaging pattern of thought that can result in disappointment, frustration, anger, and even depression when the awaited reward does not materialize.

Changing Your Thinking: Examples of Techniques to Combat Cognitive Distortions

These distortions, while common and potentially extremely damaging, are not something we must simply resign ourselves to living with.

Beck, Burns, and other researchers in this area have developed numerous ways to identify, challenge, minimize, or erase these distortions from our thinking.

Some of the most effective and evidence-based techniques and resources are listed below.

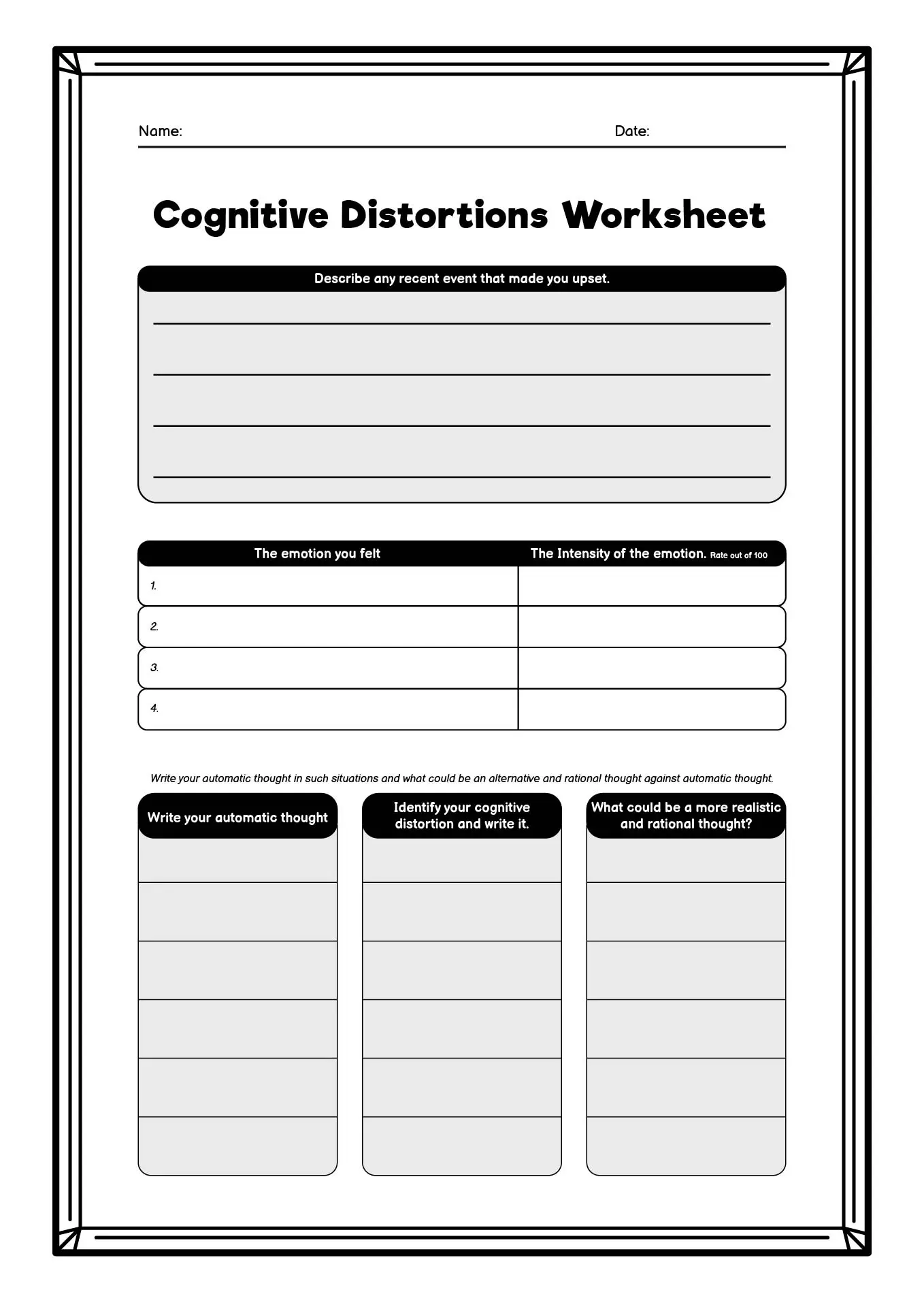

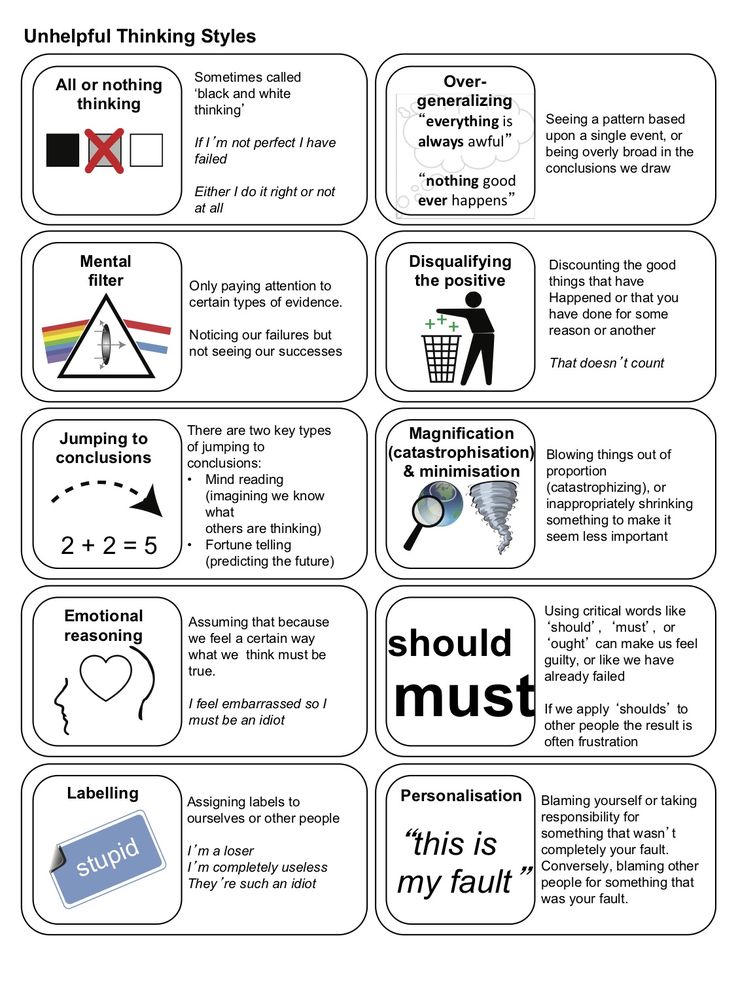

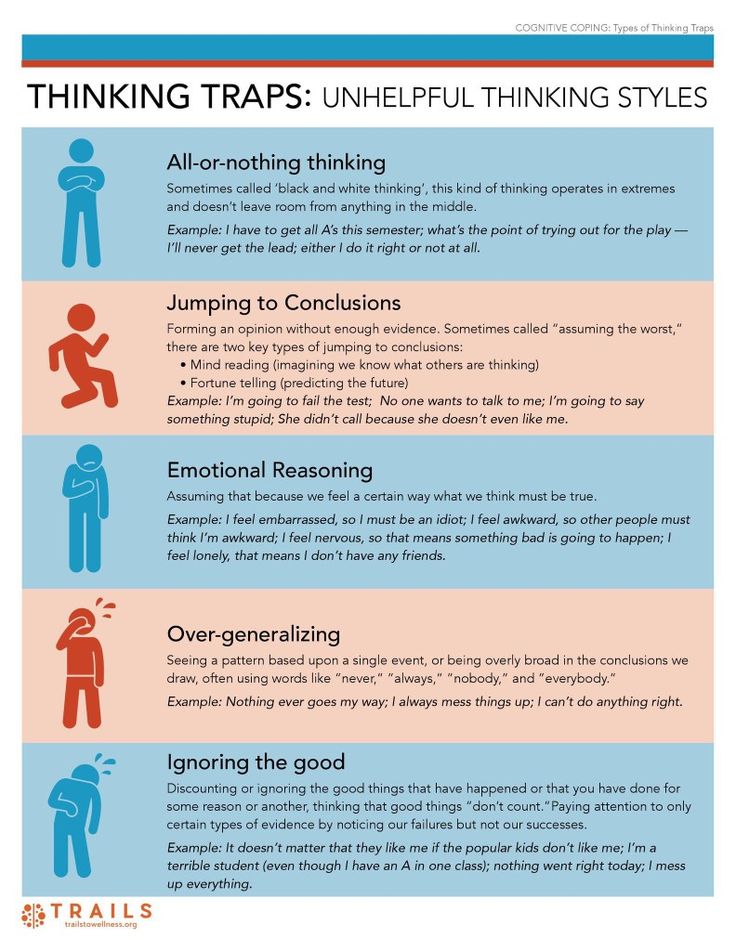

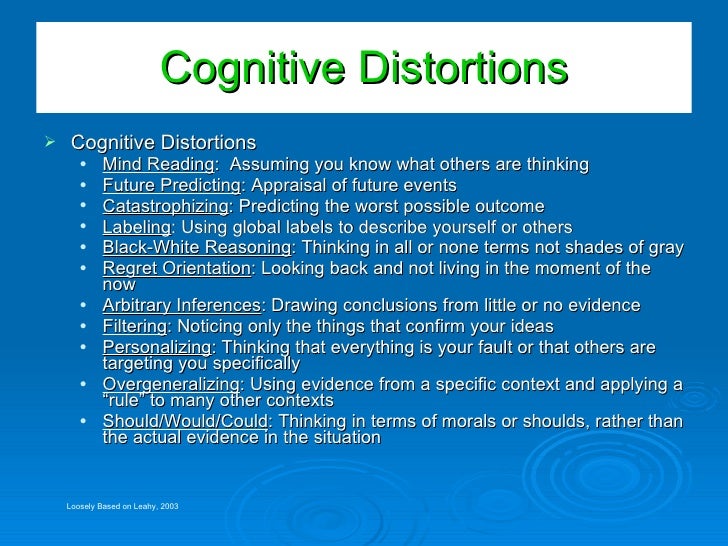

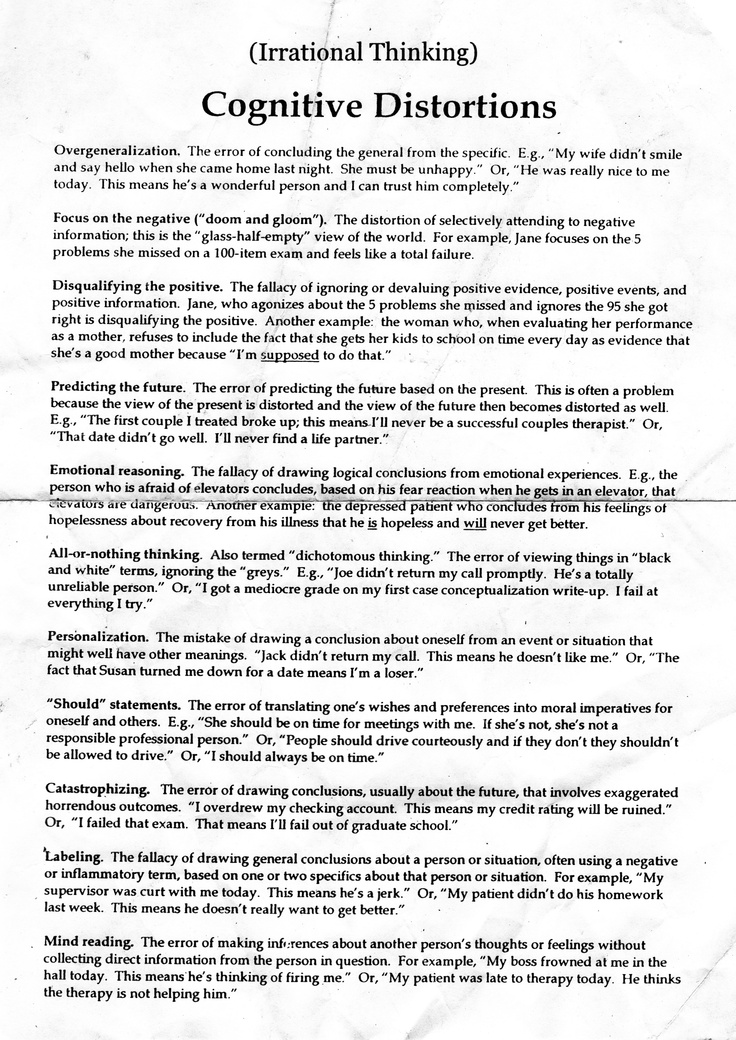

Cognitive Distortions Handout

Since you must first identify the distortions you struggle with before you can effectively challenge them, this resource is a must-have.

The Cognitive Distortions handout lists and describes several types of cognitive distortions to help you figure out which ones you might be dealing with.

The distortions listed include:

- All-or-Nothing Thinking;

- Overgeneralizing;

- Discounting the Positive;

- Jumping to Conclusions;

- Mind Reading;

- Fortune Telling;

- Magnification (Catastrophizing) and Minimizing;

- Emotional Reasoning;

- Should Statements;

- Labeling and Mislabeling;

- Personalization.

The descriptions are accompanied by helpful descriptions and a couple of examples.

This information can be found in the Increasing Awareness of Cognitive Distortions exercise in the Positive Psychology Toolkit©.

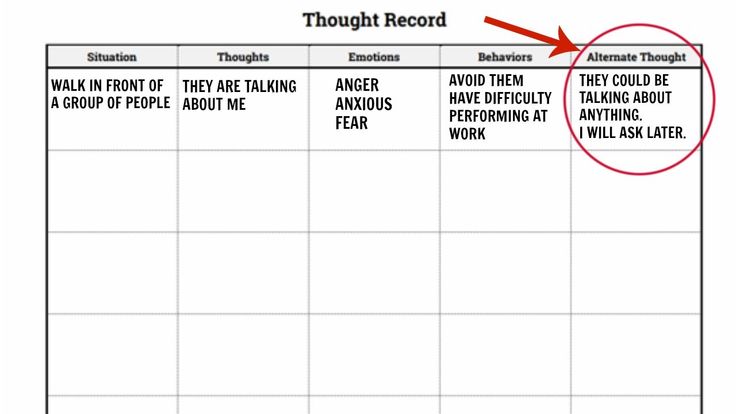

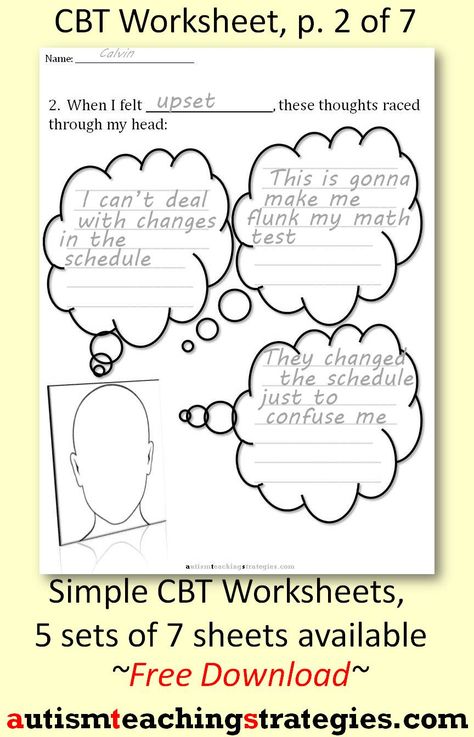

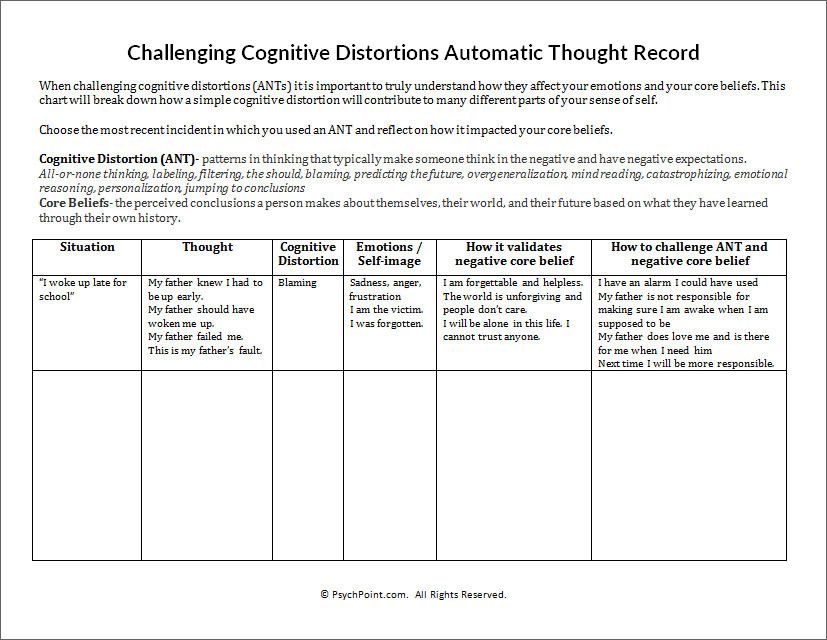

Automatic Thought Record

This worksheet is an excellent tool for identifying and understanding your cognitive distortions. Our automatic, negative thoughts are often related to a distortion that we may or may not realize we have. Completing this exercise can help you to figure out where you are making inaccurate assumptions or jumping to false conclusions.

The worksheet is split into six columns:

- Date/Time

- Situation

- Automatic Thoughts (ATs)

- Emotion/s

- Your Response

- A More Adaptive Response

First, you note the date and time of the thought.

In the second column, you will write down the situation. Ask yourself:

- What led to this event?

- What caused the unpleasant feelings I am experiencing?

The third component of the worksheet directs you to write down the negative automatic thought, including any images or feelings that accompanied the thought. You will consider the thoughts and images that went through your mind, write them down, and determine how much you believed these thoughts.

After you have identified the thought, the worksheet instructs you to note the emotions that ran through your mind along with the thoughts and images identified. Ask yourself what emotions you felt at the time and how intense the emotions were on a scale from 1 (barely felt it) to 10 (completely overwhelming).

Next, you have an opportunity to come up with an adaptive response to those thoughts. This is where the real work happens, where you identify the distortions that are cropping up and challenge them.

Ask yourself these questions:

- Which cognitive distortions were you employing?

- What is the evidence that the automatic thought(s) is true, and what evidence is there that it is not true?

- You’ve thought about the worst that can happen, but what’s the best that could happen? What’s the most realistic scenario?

- How likely are the best-case and most realistic scenarios?

Finally, you will consider the outcome of this event. Think about how much you believe the automatic thought now that you’ve come up with an adaptive response, and rate your belief. Determine what emotion(s) you are feeling now and at what intensity you are experiencing them.

You can access the Automatic Thought Record Worksheet here.

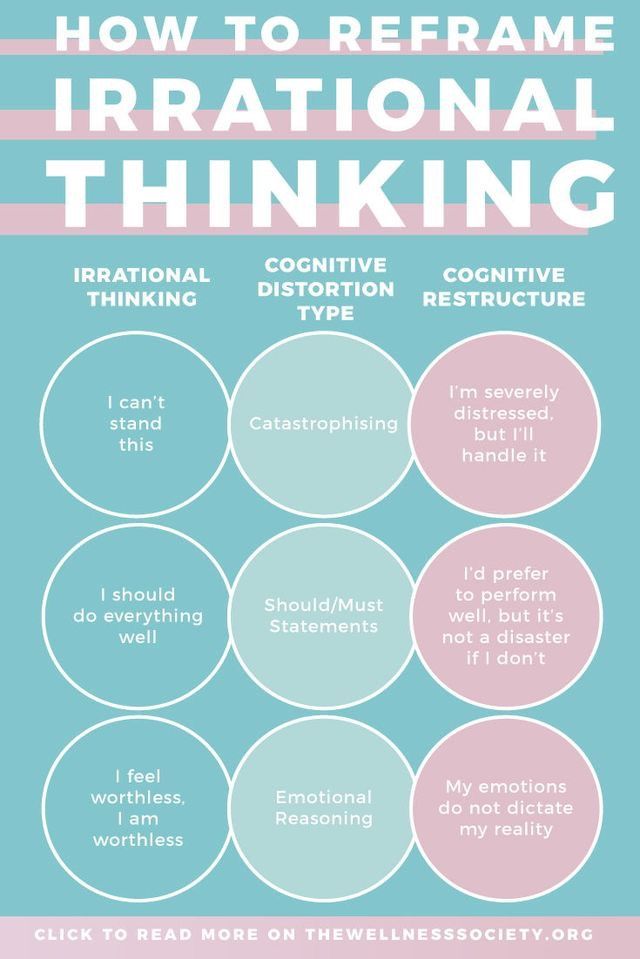

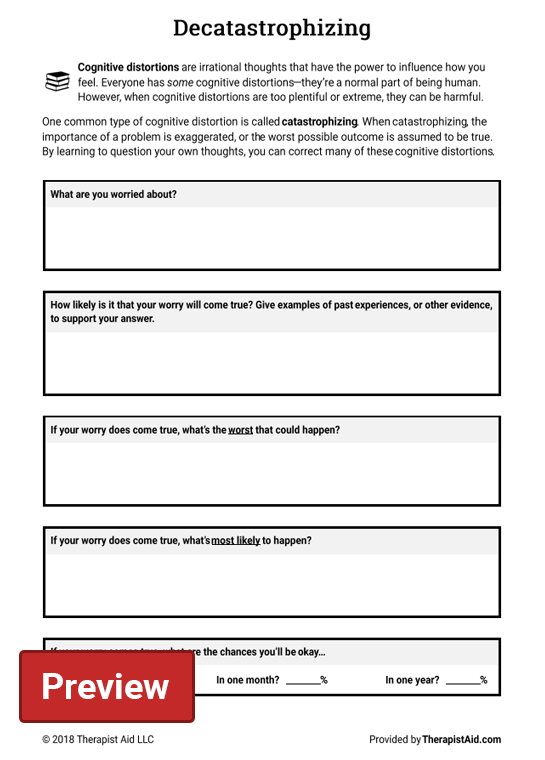

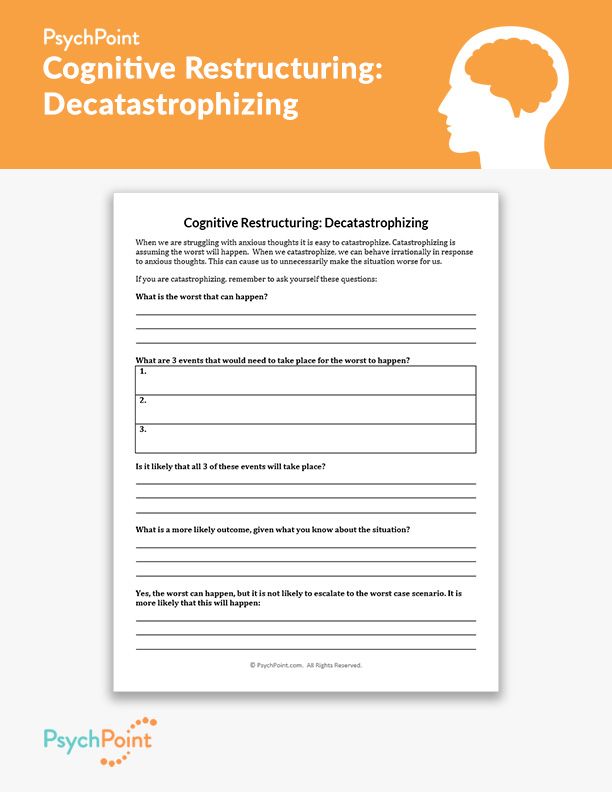

Decatastrophizing

This is a particularly good tool for talking yourself out of catastrophizing a situation.

The worksheet begins with a description of cognitive distortions in general and catastrophizing in particular; catastrophizing is when you distort the importance or meaning of a problem to be much worse than it is, or you assume that the worst possible scenario is going to come to pass. It’s a reinforcing distortion, as you get more and more anxious the more you think about it, but there are ways to combat it.

First, write down your worry. Identify the issue you are catastrophizing by answering the question, “What are you worried about?”

Once you have articulated the issue that is worrying you, you can move on to thinking about how this issue will turn out.

Think about how terrible it would be if the catastrophe actually came to pass. What is the worst-case scenario? Consider whether a similar event has occurred in your past and, if so, how often it occurred. With the frequency of this catastrophe in mind, make an educated guess of how likely the worst-case scenario is to happen.

After this, think about what is most likely to happen–not the best possible outcome, not the worst possible outcome, but the most likely. Consider this scenario in detail and write it down. Note how likely you think this scenario is to happen as well.

Next, think about your chances of surviving in one piece. How likely is it that you’ll be okay one week from now if your fear comes true? How likely is it that you’ll be okay in one month? How about one year? For all three, write down “Yes” if you think you’d be okay and “No” if you don’t think you’d be okay.

Finally, come back to the present and think about how you feel right now. Are you still just as worried, or did the exercise help you think a little more realistically? Write down how you’re feeling about it.

This worksheet can be an excellent resource for anyone who is worrying excessively about a potentially negative event.

You can download the Decatastrophizing Worksheet here.

Cataloging Your Inner Rules

Cognitive distortions include assumptions and rules that we hold dearly or have decided we must live by. Sometimes these rules or assumptions help us to stick to our values or our moral code, but often they can limit and frustrate us.

This exercise can help you to think more critically about an assumption or rule that may be harmful.

First, think about a recent scenario where you felt bad about your thoughts or behavior afterward. Write down a description of the scenario and the infraction (what you did to break the rule).

Next, based on your infraction, identify the rule or assumption that was broken. What are the parameters of the rule? How does it compel you to think or act?

Once you have described the rule or assumption, think about where it came from. Consider when you acquired this rule, how you learned about it, and what was happening in your life that encouraged you to adopt it. What makes you think it’s a good rule to have?

Now that you have outlined a definition of the rule or assumption and its origins and impact on your life, you can move on to comparing its advantages and disadvantages. Every rule or assumption we follow will likely have both advantages and disadvantages.

Every rule or assumption we follow will likely have both advantages and disadvantages.

The presence of one advantage does not mean the rule or assumption is necessarily a good one, just as the presence of one disadvantage does not automatically make the rule or assumption a bad one. This is where you must think critically about how the rule or assumption helps and/or hurts you.

Finally, you have an opportunity to think about everything you have listed and decide to either accept the rule as it is, throw it out entirely and create a new one, or modify it into a rule that would suit you better. This may be a small change or a big modification.

If you decide to change the rule or assumption, the new version should maximize the advantages of the rule, minimize or limit the disadvantages, or both. Write down this new and improved rule and consider how you can put it into practice in your daily life.

You can download the Cataloging Your Inner Rules Worksheet.

Facts or Opinions?

This is one of the first lessons that participants in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) learn – that facts are not opinions. As obvious as this seems, it can be difficult to remember and adhere to this fact in your day to day life.

As obvious as this seems, it can be difficult to remember and adhere to this fact in your day to day life.

This exercise can help you learn the difference between fact and opinion, and prepare you to distinguish between your own opinions and facts.

The worksheet lists the following fifteen statements and asks the reader to decide whether they are fact or opinion:

- I am a failure.

- I’m uglier than him/her.

- I said “no” to a friend in need.

- A friend in need said “no” to me.

- I suck at everything.

- I yelled at my partner.

- I can’t do anything right.

- He said some hurtful things to me.

- She didn’t care about hurting me.

- This will be an absolute disaster.

- I’m a bad person.

- I said things I regret.

- I’m shorter than him.

- I am not loveable.

- I’m selfish and uncaring.

- Everyone is a way better person than I am.

- Nobody could ever love me.

- I am overweight for my height.

- I ruined the evening.

- I failed my exam.

Practicing making this distinction between fact and opinion can improve your ability to quickly differentiate between the two when they pop up in your own thoughts.

Here is the Facts or Opinions Worksheet.

In case you’re wondering which is which, here is the key:

- I am a failure. False

- I’m uglier than him/her. False

- I said “no” to a friend in need. True

- A friend in need said “no” to me. True

- I suck at everything. False

- I yelled at my partner. True

- I can’t do anything right. False

- He said some hurtful things to me. True

- She didn’t care about hurting me. False

- This will be an absolute disaster. False

- I’m a bad person. False

- I said things I regret. True

- I’m shorter than him. True

- I am not loveable.

False

False - I’m selfish and uncaring. False

- Everyone is a way better person than I am. False

- Nobody could ever love me. False

- I am overweight for my height. True

- I ruined the evening. False

- I failed my exam. True

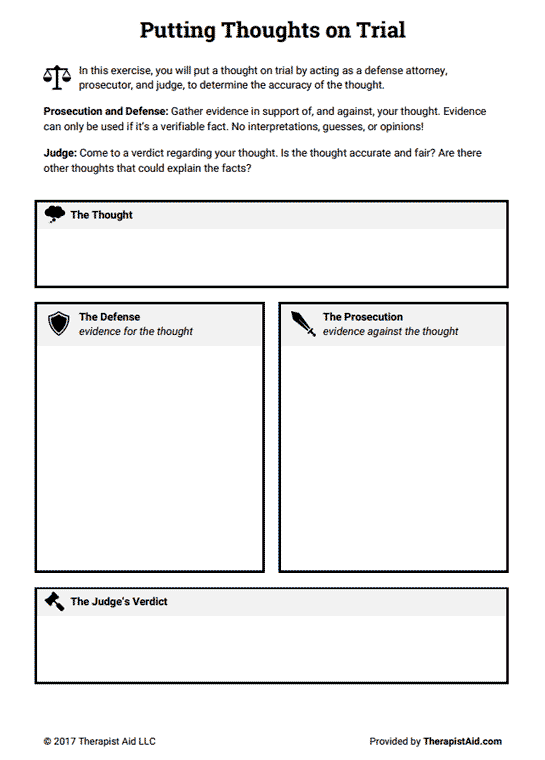

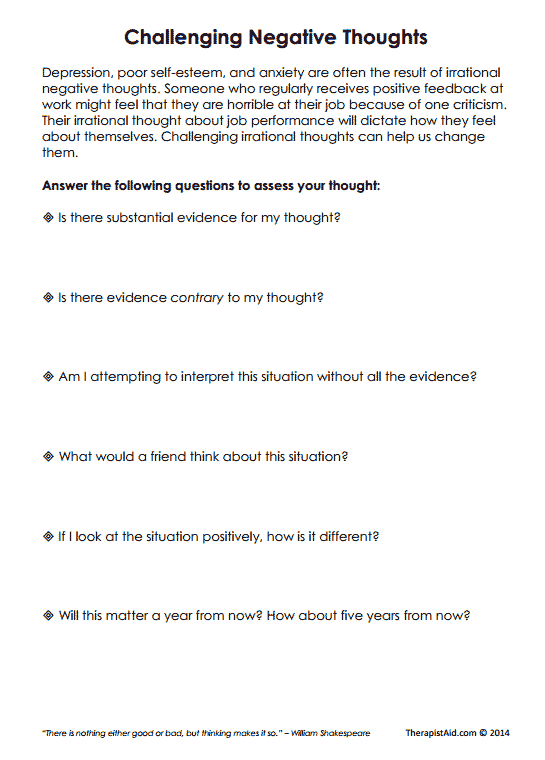

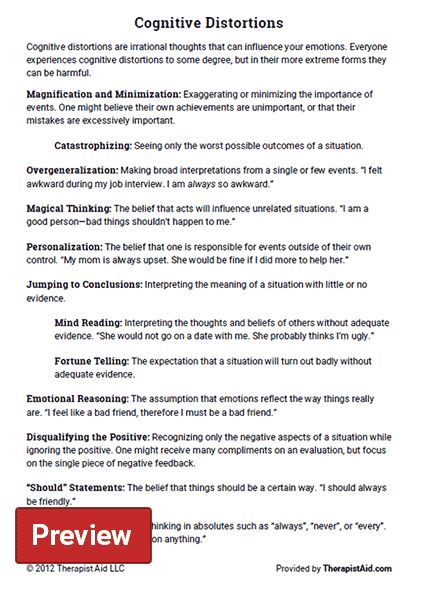

Putting Thoughts on Trial

This exercise uses CBT theory and techniques to help you examine your irrational thoughts. You will act as the defense attorney, prosecutor, and judge all at once, providing evidence for and against the irrational thought and evaluating the merit of the thought based on this evidence.

The worksheet begins with an explanation of the exercise and a description of the roles you will be playing.

The first box to be completed is “The Thought.” This is where you write down the irrational thought that is being put on trial.

Next, you fill out “The Defense” box with evidence that corroborates or supports the thought. Once you have listed all of the defense’s evidence, do the same for “The Prosecution” box. Write down all of the evidence calling the thought into question or instilling doubt in its accuracy.

Once you have listed all of the defense’s evidence, do the same for “The Prosecution” box. Write down all of the evidence calling the thought into question or instilling doubt in its accuracy.

When you have listed all of the evidence you can think of, both for and against the thought, evaluate the evidence and write down the results of your evaluation in “The Judge’s Verdict” box.

This worksheet is a fun and engaging way to think critically about your negative or irrational thoughts and make good decisions about which thoughts to modify and which to embrace.

Click here to see this worksheet for yourself (TherapistAid).

A Take-Home Message

Hopefully, this piece has given you a good understanding of cognitive distortions. These sneaky, inaccurate patterns of thinking and believing are common, but their potential impact should not be underestimated.

Even if you are not struggling with depression, anxiety, or another serious mental health issue, it doesn’t hurt to evaluate your own thoughts every now and then. The sooner you catch a cognitive distortion and mount a defense against it, the less likely it is to make a negative impact on your life.

The sooner you catch a cognitive distortion and mount a defense against it, the less likely it is to make a negative impact on your life.

What is your experience with cognitive distortions? Which ones do you struggle with? Do you think we missed any important ones? How have you tackled them, whether in CBT or on your own?

Let us know in the comments below. We love hearing from you.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. For more information, don’t forget to download our 3 Positive CBT Exercises for free.

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapies and emotional disorders. New York, NY: New American Library.

- Burns, D. D. (1980). Feeling good: The new mood therapy. New York, NY: New American Library.

- Burns, D. D. (1989). The feeling good handbook. New York, NY: Morrow.

- Burns, D. D., Shaw, B. F., & Croker, W. (1987). Thinking styles and coping strategies of depressed women: An empirical investigation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 25, 223-225.

- Feeling Good. (n.d.). About. Feeling Good. Retrieved from https://feelinggood.com/about/

- GoodTherapy. (2015). Aaron Beck. GoodTherapy LLC. Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/famous-psychologists/aaron-beck.html

- Summit for Clinical Excellence. (n.d.). David Burns, MD. Summit for clinical excellence faculty page. Retrieved from https://summitforclinicalexcellence.com/partners/faculty/david-burns/

- TherapistAid. (n.d.). Cognitive restructuring: Thoughts on trial. Retrieved from https://www.therapistaid.com/worksheets/putting-thoughts-on-trial.pdf

Cognitive Restructuring (Guide) | Therapist Aid

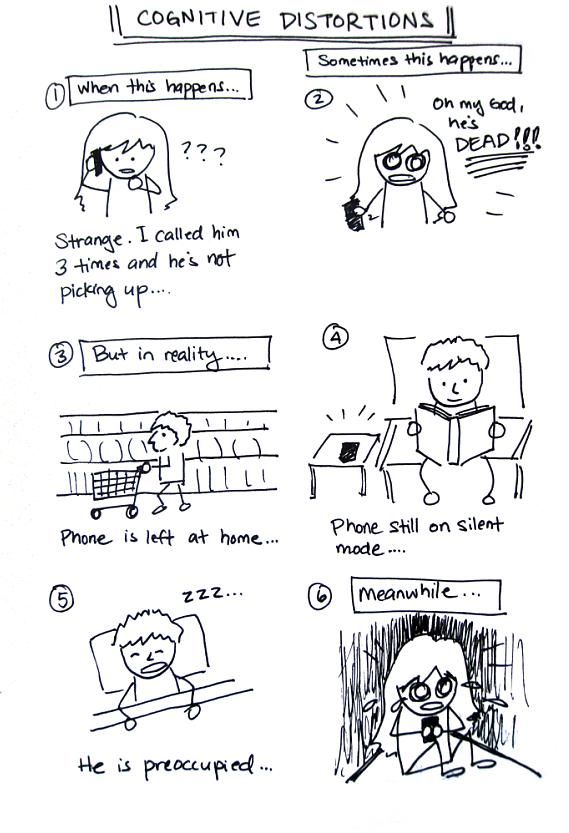

Imagine it’s your birthday. You’re expecting a phone call from a close friend, but it never comes. You called them on their birthday, so why didn’t they call you? Do they not care enough to remember your birthday? You feel hurt.

Where did this feeling of hurt come from? It wasn’t the lack of a phone call that caused the hurt. It was the thoughts about the lack of a phone call that hurt. What if, instead of taking the missing phone call personally, you had thought:

It was the thoughts about the lack of a phone call that hurt. What if, instead of taking the missing phone call personally, you had thought:

- “My friend is so forgetful! I bet they don’t know anyone’s birthday.”

- “Maybe something came up unexpectedly, and they’re busy.”

- “We did talk earlier in the week, so I guess it isn’t a big deal.”

Thoughts play a powerful role in determining how people feel and how they act. If someone thinks positively about something, they’ll probably feel positively about it. Conversely, if they think negatively about something—whether or not that thought is supported by evidence—they will feel negatively.

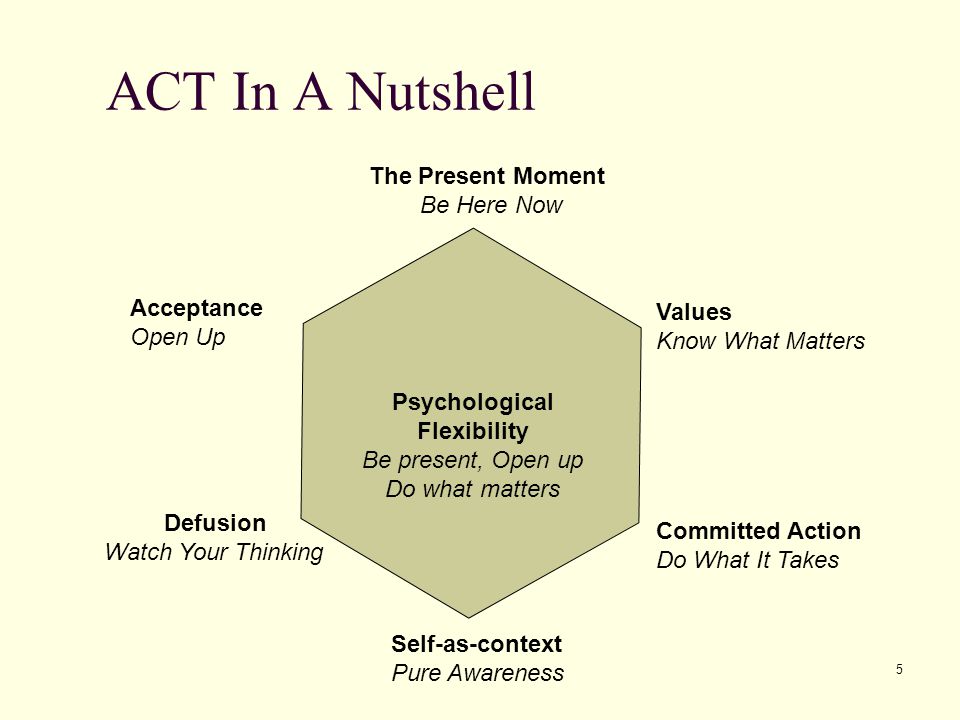

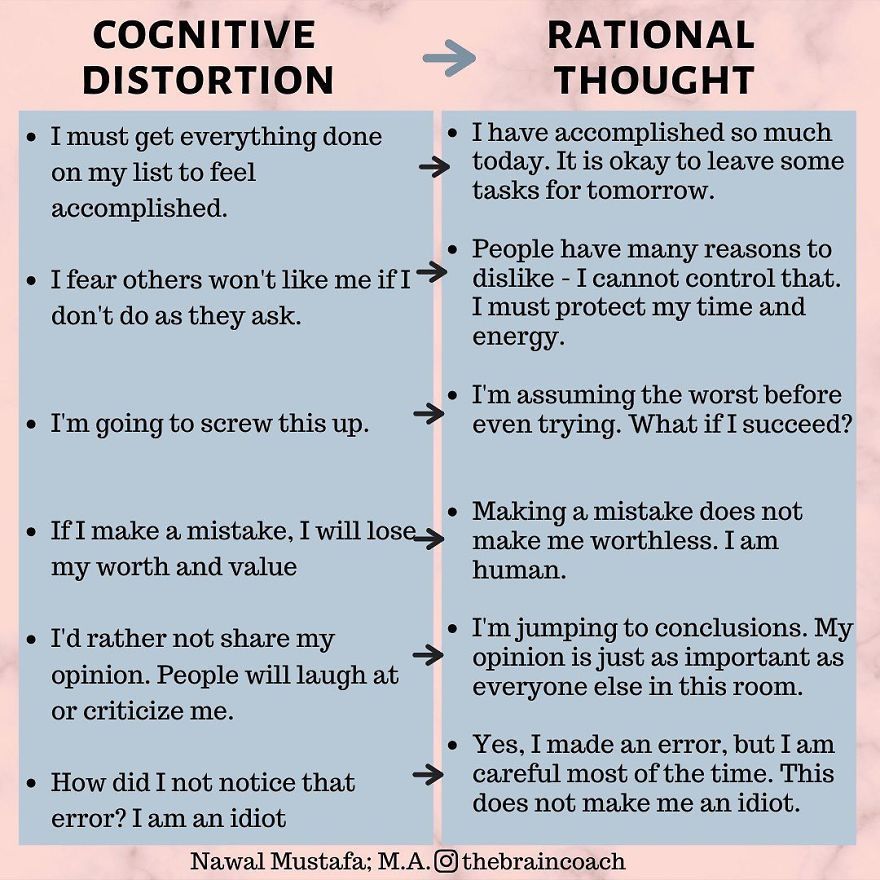

Cognitive restructuring is the therapeutic process of identifying and challenging negative and irrational thoughts, such as those described in the birthday example. These sort of thoughts are called cognitive distortions. Although everyone has some cognitive distortions, having too many is closely linked to mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and several other approaches to psychotherapy, make heavy use of cognitive restructuring. Each of these therapies leverages the powerful link between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to treat mental illness.

The thought-feeling-behavior link is a big topic in itself, and beyond the scope of this guide. If you want to learn more, check out our CBT Psychoeducation guide and worksheet.

Remember, cognitive restructuring refers to the process of challenging thoughts—it isn’t a single technique. There are many techniques that fall under the umbrella of cognitive restructuring, which we will describe (alongside several therapy tools) throughout this guide.

Identifying Negative Thoughts / Cognitive Distortions

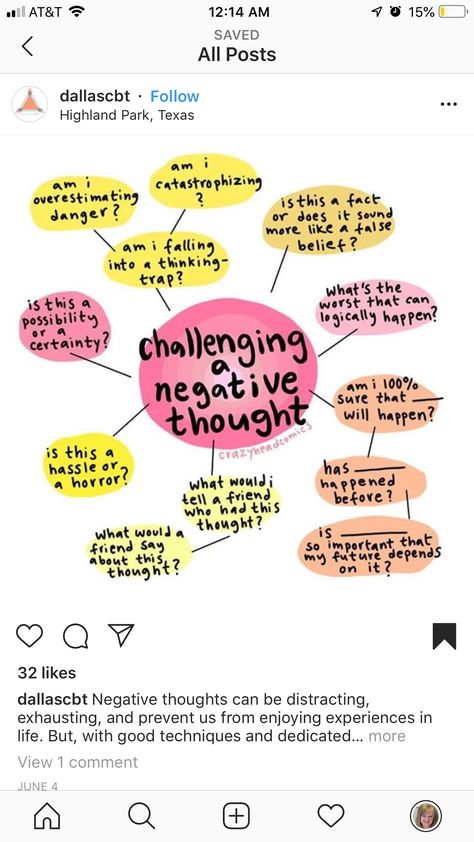

Cognitive restructuring starts with the identification of irrational negative thoughts (cognitive distortions). This is trickier than it sounds. Cognitive distortions can happen so quickly that they come and go before we’ve noticed them. They’re more like a reflex than an intentional behavior. Below, we’ll discuss how to help your clients identify their cognitive distortions.

They’re more like a reflex than an intentional behavior. Below, we’ll discuss how to help your clients identify their cognitive distortions.

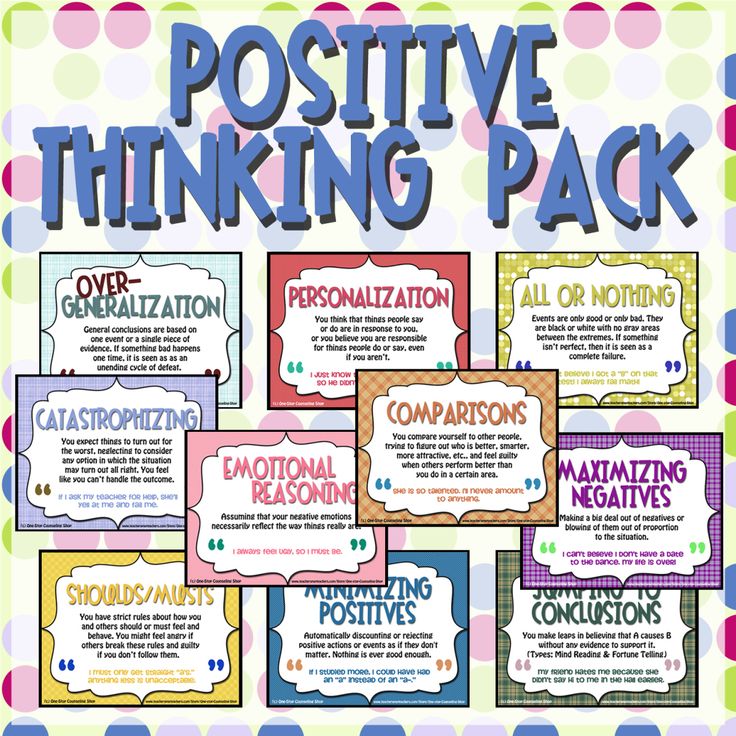

Step 1: Psychoeducation

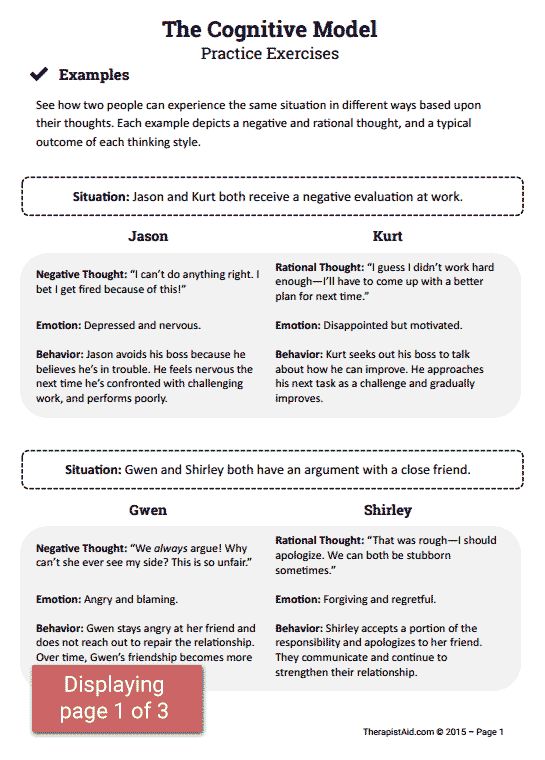

Before jumping into the “doing” part of cognitive restructuring, it’s important for clients to understand what cognitive distortions are, and how powerful they are in influencing one’s mood. Start with psychoeducation about the cognitive model and cognitive distortions, using plenty of examples.

CBT Psychoeducation

worksheet

The CBT Model: Psychoeducation

worksheet

Cognitive Distortions

worksheet

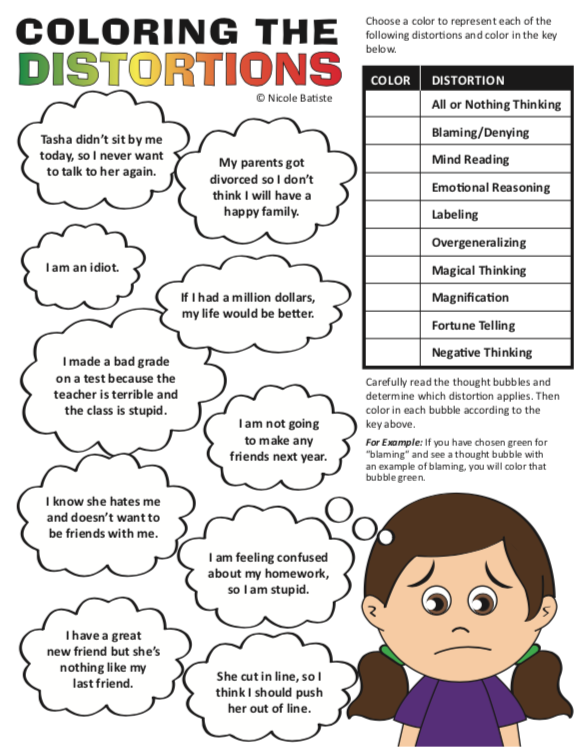

Tip: Share a list of common cognitive distortions with your clients to start a discussion about how our thoughts impact emotions, whether or not they’re accurate. Most clients will identify with at least a few of the cognitive distortions, and easily connect them with their own experiences. In a group, ask participants to circle the cognitive distortions they’ve fallen victim to, and share stories.

In a group, ask participants to circle the cognitive distortions they’ve fallen victim to, and share stories.

Step 2: Increase Awareness of Thoughts

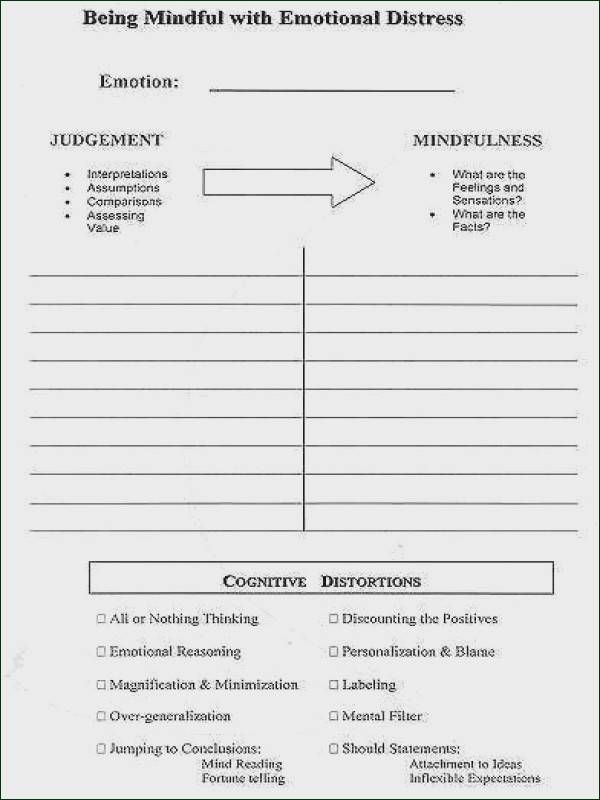

After building a general understanding of the cognitive model, your clients will learn to identify their own cognitive distortions. This takes practice. It’s not natural, during a fit of rage, to stop and wonder: “What thoughts led me to this moment?”

To hone in on the most important cognitive distortions, start by looking for negative emotions. When are symptoms of depression, anger, or anxiety at their worst? If your client has difficulty identifying their emotions, focus on behaviors. What behaviors do they want to change? What triggers those behaviors? Think of these situations like alarms, alerting you that cognitive distortions are nearby.

This discussion is intended to improve your client’s awareness of situations where cognitive distortions are impacting their mood and behavior. The more specific triggers or situations they can identify, the easier it will be to recognize them in the moment.

Tip: When emotions seem to sneak up on your client, or if they have a hard time identifying their emotions, have a discussion about warning signs. How do they feel or behave differently immediately before the situation occurs? For example, someone struggling with anger might notice that their face feels hot, or their voice trembles, before they “snap”.

Anger Warning Signs

worksheet

With the completion of step 2, your client has laid the foundation for a core tool of cognitive restructuring: thought records.

Step 3: Thought Records

A thought record (also called a thought log) is a tool for recording experiences, along with the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that accompany them. This exercise will help your clients become aware of cognitive distortions that previously went unnoticed, and unquestioned. With practice, they will learn to identify cognitive distortions in the moment, and immediately challenge them.

Each row of a thought record represents a unique situation. The headings for each column will differ slightly between thought records, but generally they include “situation”, “thoughts”, “feelings”, “consequences”, and sometimes, “alternate thought”. Ideally, each row is filled in shortly after a situation ends.

Tip: When a client has a hard time remembering to complete their thought record, ask them to set a regular time to fill it out each day. Encourage them to set a reminder on their phone, or to complete it at a time that’s easy to remember (e.g. right before bed).

Thought Record

worksheet

Thought Record (with example)

worksheet

Tip: When generating alternate thoughts, the goal isn’t to be ultra-positive, but rather, to be fair. It’s fine to acknowledge when a bad situation exists. The exaggeration of a bad situation is what we want to avoid.

Sometimes, the mere awareness of a cognitive distortion will be enough to eliminate it. Other cognitive distortions are more deeply ingrained, and require extra work. This is where cognitive restructuring techniques, which make up the rest of this guide, will come in handy.

Cognitive Restructuring Techniques

When looking at other people’s cognitive distortions, they seem easy to dispute. No matter how much your friend believes that they’re the “worst person ever”, you know that to be untrue. But when it comes to a person’s own cognitive distortions, they can be much more difficult to overcome. That’s why they persist. We believe in our own cognitive distortions, no matter how inaccurate they may be.

For these difficult cognitive distortions, we have several techniques to help tear them down. These techniques should be used again and again, whenever cognitive distortions are identified. With enough repetition, the cognitive distortions will be extinguished and replaced with new, balanced thoughts. Here are the techniques.

Here are the techniques.

Socratic Questioning

Socrates was a Greek philosopher who emphasized the importance of questioning as a way to explore complex ideas and uncover assumptions. This philosophy has been adopted as a way to challenge cognitive distortions.

Once a cognitive distortion has been identified, this technique is simple. The cognitive distortion will be assessed by asking a series of questions. Therapists can set an example by asking these questions of their clients, but ultimately, the client should learn to question their own thoughts.

Socratic Questioning

worksheet

Tip: Anyone can quickly spit out answers, just to have the exercise done. However, the value of Socratic questioning comes from the thought behind each answer. Spend at least 1-3 minutes on each question to get the most out of this exercise.

Decatastrophizing

Oftentimes, cognitive distortions are just an exaggerated view of reality. Before a first date, a person might find themselves overwhelmed with anxiety, thinking of all the things that might go wrong. Maybe their date won’t like how they look, or maybe they’ll make a fool of themselves.

Before a first date, a person might find themselves overwhelmed with anxiety, thinking of all the things that might go wrong. Maybe their date won’t like how they look, or maybe they’ll make a fool of themselves.

With the decatastrophizing technique, we ask very simple questions: “What if?” or “What’s the worst that could happen?”

Client: I always worry that my date won’t like how I look, or I’ll make a fool of myself. This leads to me getting so nervous that I do make a fool of myself.

Therapist: So, what if those things come true? What if your date doesn’t like how you look, or you make a fool of yourself?

Client: Well, we probably won’t have a second date…

Therapist: What if you don’t have a second date? What happens then?

Client: I guess nothing. I just won’t see them again.

This sequence of questioning helps to reduce the irrational level of anxiety associated with cognitive distortions. It highlights the fact that even the worst-case scenario is manageable.

Note: Decatastrophizing is sometimes called the “what if” technique because of the style of questioning.

Putting Thoughts on Trial

In this exercise, your client will act as a defense attorney, a prosecutor, and a judge.

First, your client will act as a defense attorney by defending their negative thought. Ask them to make an argument for why the thought is true. Remember to stick to verifiable facts. Interpretation, guesses, and opinions aren’t allowed!

Next, ask your client to act as the prosecutor. Now they will present evidence against the negative thought. Just like in the previous step, require that they stick to facts, while excluding opinions.

Finally, ask your client to act as the judge. They will review the evidence, and deliver a verdict. The verdict should come in the form of a rational thought.

Putting Thoughts on Trial

worksheet

If you would like to continue learning about cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive distortions, and cognitive restructuring, check out these additional resources:

CBT Practice Exercises

worksheet

Change How You Feel by Changing the Way You Think

book

What is CBT?

video

1. Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clinical psychology review, 26(1), 17-31.

Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clinical psychology review, 26(1), 17-31.

2. Carey, T. A., & Mullan, R. J. (2004). What is socratic questioning? Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 41(3), 217.

3. McManus, F., Van Doorn, K., & Yiend, J. (2012). Examining the effects of thought records and behavioral experiments in instigating belief change. Journal of behavior therapy and experimental psychiatry, 43(1), 540-547.

Top 15 cognitive biases | PSYCHOLOGIES

119,021

Knowing Yourself A Human Among Humans

Generally, our mind uses cognitive distortions to reinforce some negative emotion or negative line of reasoning. The voice in our head sounds rational and authentic, but in reality only reinforces our poor opinion of ourselves.

For example, we say to ourselves, "I always fail when I try to do something new. " This is an example of "black and white" thinking - with this cognitive distortion, we perceive the situation only in absolute categories: if we fail in one thing, then we are doomed to endure it in the future, in everything and always.

" This is an example of "black and white" thinking - with this cognitive distortion, we perceive the situation only in absolute categories: if we fail in one thing, then we are doomed to endure it in the future, in everything and always.

If we add “I must be a complete loser” to these thoughts, this is an example of overgeneralization - such a cognitive distortion generalizes ordinary failure to the scale of our entire personality, we make it our essence.

Here are the main examples of cognitive distortions that are worth remembering and practicing, tracking them and responding to each in a more calm and measured way.

1. Filtering

We focus on the negative while filtering out all the positive aspects of the situation. Obsessed with an unpleasant detail, we lose objectivity, and reality is blurred and distorted.

2. Black and white thinking

With black and white thinking, we see everything either in black or in white, there can be no other shades. We must do everything perfectly or we will fail - there is no middle ground. We rush from one extreme to another, not allowing the idea that most situations and characters are complex, composite, with many shades.

We must do everything perfectly or we will fail - there is no middle ground. We rush from one extreme to another, not allowing the idea that most situations and characters are complex, composite, with many shades.

3. Overgeneralization

With this cognitive distortion, we come to a conclusion based on a single aspect, a "piece" of what happened. If something bad happens once, we convince ourselves that it will happen again and again. We begin to see a single unpleasant event as part of an endless chain of defeats.

4. Jumping to conclusions

The other person hasn't said a word yet, and we already know exactly what he feels and why he behaves the way he does. In particular, we are confident that we can determine how people feel about us.

For example, we may conclude that someone does not love us, but we will not lift a finger to find out if this is true. Another example: we convince ourselves that things will go wrong, as if it were a fait accompli.

5. Injection

We live in anticipation of a catastrophe that is about to break out, ignoring the objective reality. The same can be said about the habit of minimizing and exaggerating. When we hear about a problem, we immediately turn on “what if? ..”: “If this happens to me? What if tragedy happens?

We exaggerate the importance of minor events (say, our own mistake or someone else's achievement) or, conversely, mentally reduce an important event until it seems tiny (for example, our own desired qualities or the shortcomings of others).

6. Personification

With this cognitive distortion, we believe that the actions and words of others are a personal reaction to us, our words and actions. We also constantly compare ourselves to others, trying to figure out who is smarter, better looking, and so on.

In addition, we can consider ourselves the cause of some unpleasant event, for which we objectively do not bear any responsibility. For example, a skewed chain of reasoning might be: “We were late for dinner, so the hostess dried the meat. If only I had hurried my husband, this would not have happened.

If only I had hurried my husband, this would not have happened.

7. False conclusion about control

If we feel that we are controlled from the outside, then we feel like a helpless victim of fate. The fallacy of control makes us responsible for the pain and happiness of everyone around us. "Why are not you happy? Is it because I did something wrong?

8. False conclusion about fairness

We feel offended that we have been treated unfairly, but others may have a different point of view on this matter. Remember, as children, when things didn't go the way we wanted them to, adults would say, "Life isn't always fair."

Those of us who judge every situation "fairly" often end up feeling bad. Because life is sometimes "unfair" - not everything and not always develops in our favor, no matter how much we would like it.

9. Blame

We believe that other people are responsible for our pain, or vice versa, we blame ourselves for every problem. An example of such a cognitive distortion is expressed in the phrase: “You keep making me feel bad about myself, stop it!” No one can "make you think" or make you feel - we ourselves control our emotions and emotional reactions.

An example of such a cognitive distortion is expressed in the phrase: “You keep making me feel bad about myself, stop it!” No one can "make you think" or make you feel - we ourselves control our emotions and emotional reactions.

10. "I (shouldn't)"

We have a list of ironclad rules about how we and the people around us should behave. Anyone who breaks one of the rules causes our anger, and we get angry at ourselves when we break them ourselves. We often try to motivate ourselves with what we should or should not, as if we are doomed to receive punishment before we do anything.

For example: “I have to go in for sports. I shouldn't be so lazy." “Must”, “must”, “should” are from the same series. The emotional consequence of this cognitive distortion is guilt. And when we take a "should" approach to other people, we often feel anger, impotent rage, frustration, and resentment.

11. Emotional arguments

We believe that what we feel must automatically be true. If we feel stupid or boring, then we really are. We take for granted how our unhealthy emotions reflect reality. "That's how I feel, so it must be true."

If we feel stupid or boring, then we really are. We take for granted how our unhealthy emotions reflect reality. "That's how I feel, so it must be true."

12. False conclusion about change

We tend to expect others to change to suit our desires and demands. You just need to press or cajole properly. The drive to change others is so persistent because we feel like our hopes and happiness depend entirely on those around us.

13. Labeling

We generalize one or two qualities to a global judgment, we take the generalization to the extreme. This cognitive bias is also called labeling. Instead of analyzing the error in the context of a particular situation, we attach an unhealthy label to ourselves. For example, we say “I am a loser” after failing in some business.

Faced with the unpleasant consequences of someone's behavior, we can attach a label to the person who behaved in such a way

“He/she constantly throws his children at strangers” - about a parent whose children spend every day in kindergarten. Such a label is usually charged with negative emotions.

Such a label is usually charged with negative emotions.

14. Desire to always be right

All our life we try to prove that our opinions and actions are the most correct. Being wrong is unthinkable, so we go to great lengths to demonstrate that we are right. “I don’t care if my words hurt you, I will still prove to you that I am right and win this argument.” The consciousness of being right for many is more important than the feelings of people around, including even those closest to them.

15. False conclusion about the reward in heaven

We are sure that our sacrifices and caring for others to the detriment of our own interests will surely pay off - as if someone invisible is keeping score. And we feel bitter disappointment when we do not receive the long-awaited reward.

Text: Ksenia Tatarnikova Photo source: Unsplash

New on the site

6 signs that you are truly in love

“The girl said that we would not have sex before the wedding: what should I do with the desire to change?”

“The man stopped seeing me because he was busy. Is it worth waiting for it?

Is it worth waiting for it?

Giving birth at the age of 18 or 45: what disease does it threaten the child with?

Why we like unapproachable men: 7 reasons - find out the secret of their attractiveness

Is there a gender psychology? A short course on the differences between men and women

"How to find out if my husband is cheating on me or not?"

“I am in a toxic relationship and I constantly think about the guy’s friend”

20 cognitive biases: how they affect our lives

113 257

Know yourselfA man among peoplePractices how to

- Photo

- Unsplash

Worldview is not determined by circumstances. We ourselves choose our attitude to everything that happens around us. What is the difference between someone who remains optimistic despite many adversities and someone who is angry at the whole world for pinching his finger? It's all about different patterns of thinking.

In psychology, the term "cognitive distortion" is used, which means an illogical, preconceived conclusion or belief that distorts the perception of reality, usually in a negative way. The phenomenon is quite common, but if you do not know what it is expressed in, it is not easy to recognize it. In most cases, this is the result of automatic thoughts. They are so natural that a person does not even realize that he can change them. It is not surprising that many take a fleeting assessment for an indisputable truth.

Cognitive distortions cause serious harm to mental health and often lead to stress, depression and anxiety. Anyone who wants to maintain a healthy psyche will do well to understand how cognitive distortions work and how they affect our worldview.

Common cognitive distortions

1. Black and white thinking

A person with dichotomous thinking perceives the world from the position of “either/or”, there is no third way.

Good or bad, right or wrong, all or nothing. He does not admit that between black and white one can almost always find at least a few shades of gray. Anyone who sees people and events from only two sides refuses to accept intermediate (and most often the most objective) assessments.

2. Personalization

People with this type of thinking tend to overestimate their importance and take many things personally. Other people's behavior is usually seen as a consequence of their own actions or deeds. As a result, those who are prone to personalization take responsibility for external circumstances, although nothing really depended on them.

3. Hypertrophied sense of duty

Attitudes like “should”, “must”, “should” are almost always associated with cognitive distortions. For example: "I had to come to the meeting early", "I have to lose weight to become more attractive." Such thoughts cause feelings of shame or guilt.

We treat others no less categorically and say something like: “he should have called yesterday”, “she is forever indebted to me for this help”.

People with such beliefs are often upset, offended and angry at those who did not justify their hopes. But with all our desire, we are not able to influence someone else's behavior, and it is definitely not worth thinking that someone “should” do something.

4. Catastrophization

The habit of perceiving any minor annoyance as an inevitable disaster. Let's say a person fails one exam and immediately imagines that he won't finish the course at all. Or the exam is still ahead, and he "knows" in advance that he will certainly fail, because he always expects the worst - so to speak, "advance" catastrophization.

5. Exaggeration

With such a cognitive distortion, everything that happens is inflated to a colossal scale. The case resembles a catastrophe, but not so severe. It is best described by the saying "make an elephant out of a fly."

6. Understatement

Those inclined to exaggerate everything easily underestimate the significance of pleasant events.

Two opposite distortions often end up in the same bunch. People think something like this: “Yes, I was promoted, but just a little - it means that they don’t appreciate me at work.”

7. Telepathy

People with this mindset ascribe extrasensory abilities to themselves and believe they can read others like an open book. They are confident that they know what the interlocutor is thinking, although guesses are rarely true.

8. Clairvoyance

The so-called "clairvoyants" try to predict the future, usually in a black light. For example, without any reason they say that everything will end badly. Before a concert or a movie show, they usually say: “We don’t have to go anywhere, I have a presentiment that the tickets will run out in front of our noses.”

9. Generalization

The tendency to generalize means the habit of drawing conclusions from one or two cases and denying that life is too complicated for hasty conclusions. If a friend does not come to a meeting, this does not mean that he is not able to fulfill the promise at all.

In the vocabulary of a person prone to make such a cognitive error, the words “always”, “never”, “always”, “every time” are often found.

10. Devaluation

An extreme form of “all or nothing” thinking, which manifests itself in a tendency to devalue any achievements, events, experiences (including one's own) and to see everything as negative. A person with such stereotypes usually neglects compliments and praise.

11. Selective perception

Cognitive distortion, similar to the previous one, is expressed in the habit of filtering any information and choosing the “appropriate” statement. For example, a person reads his/her school testimonial or employer's recommendation, excludes all the good ones and fixates on a single critical remark.

- Photo

- Unsplash

12. Labeling

A more rigid kind of generalization means that a person evaluates himself and others on the basis of a single case.

It is easier for him to automatically label himself as a loser than to recognize someone's right to make a mistake.

13. The habit of blaming

The other side of personalization. Instead of blaming yourself for mistakes, it is more convenient to shift the blame to others or an unforeseen situation.

14. Emotional conditioning

This is the name of the erroneous sensory perception of reality. If I'm scared, then there's a real threat. If I think I'm stupid, then I am. Such thinking can indicate serious mental disorders - including pointing to obsessive-compulsive disorder. For example, a person feels dirty even though they have showered twice in the last hour.

15. The illusion of one's own rightness

A cognitive error turns a private point of view into an indisputable fact and allows one to disregard the opinions and feelings of others. This makes it very difficult to create and maintain healthy relationships.

16. Self-seeking attribution

The tendency to attribute exclusively positive qualities to oneself and deny one's involvement in any unpleasant or undesirable events.

A person with such a mindset refuses to admit his shortcomings and is absolutely confident in his own infallibility.

17. Waiting for a “divine reward”

It is a delusion that higher powers will sooner or later appreciate our sacrifices. Under its influence, people neglect their interests and needs in the hope that someday they will be rewarded for their dedication. And since this never happens, they are overcome by anger and resentment.

18. The illusion of change

The belief that others must change in order to be happy. This is the mindset of an egomaniac who insists that others fit into his schedule, or demands that a partner not wear their favorite T-shirt because they don't like it.

19. Belief in justice

The phenomenon is expressed in the idea of a just world in which everyone gets what they deserve, although in reality this rarely happens. An example of such a thinking trap is to think that a person deserved everything that happened to him.

20. Illusion of control

Someone who thinks that everything in the world can be controlled is pissed off by other people's behavior - for the simple reason that he cannot be influenced in any way. A person obsessed with the desire to control everything may blame the boss for the poor performance of the company, although the real problem may lie elsewhere.

HOW TO CORRECT THOUGHT PATTERNS?

Most likely, you have discovered at least one of the listed cognitive distortions. Perhaps you or someone you know has fallen into similar traps more than once. The good news is that we are not bound to them forever.

Patterned thinking can be changed: this process is called cognitive restructuring

Its essence is that we can influence our own emotions and actions by correcting our automatic thoughts. Many popular forms of therapy are based on this concept, including cognitive behavioral therapy and rational emotive behavior therapy.

If you have one or more cognitive distortions and feel that they cause anxiety, depression or other psychological problems, be sure to see a psychotherapist. An experienced specialist will help transform negative attitudes into more constructive and inspiring beliefs.

Arthur Freeman, Rose DeWulf "Mistakes of thinking, or how to live without regrets"

Look, make no mistake! Look, don't be sorry! Everyone has heard such phrases addressed to them many times in their lives. Is life possible without mistakes and regrets? Arthur Freeman and Rose DeWulf, recognized experts in the field of mental health, say: "Yes, it is possible!" How to learn how to make decisions right the first time, you will learn from this wonderful book, which has long become a bestseller in more than twenty countries around the world.

Advertising. www.chitai-gorod.ru

Text: Elena Anisimova Photo source: Unsplash

New on the site

6 signs that you are truly in love

be willing to change?

“The man stopped seeing me because he was busy.