Why can i read in my dreams

Can You Read In Your Dreams? Sleep Science for Readers

This post contains affiliate links. If you click and buy we may make a commission, at no additional charge to you. Please see our disclosure policy for more details.

120shares

Dreams are funny things. Pretty much anything can happen while you’re dreaming. You might grow wings and fly. All of your teeth might suddenly fall out. You might even find yourself in bed with your celebrity crush. But one thing that almost never happens in dreams is reading.

When you really think about it, when was the last time you actually ‘read’ something in a dream? You might dream of reading a text message, a street sign, a newspaper, or even a book, but did you really?

Chances are, you didn’t actually see any letters. We might not notice at the time, but our reading comprehension is usually more of a ‘telepathic’ style when we dream. Rather than reading by recognizing letters, as we do in waking life, we absorb the information through our subconscious.

In fact, the inability to read or write something is often a telltale sign that you are dreaming. Have you ever tried to read the time on a clock, but the numbers were all jumbled up? Or have you tried writing something down on a piece of paper, but your hand won’t move the right way to form the letters?

These strange things happen because our neurological processors aren’t reacting the same way they do in our waking life. When this happens, we sometimes realize that we’re dreaming and wake ourselves up.

Table of Contents

What’s Really Happening in Our Brains When We Dream?

When we fall into a REM sleep stage, the logic and language processing parts of our brain slows down. This affects not only our capacity to read but also our general language functions too.

Think about the last conversation you had in a dream. Did you really hear the words annunciated from someone’s mouth? Or was it the ‘telepathic’ communication style I mentioned above? Usually, meaning is conveyed, but not in the normal listening and speaking sense.

Language and Logic Shuts Down

The regions that process language and logic are found in the middle and backs of our brains. To understand a bit more about what happens while we’re dreaming, we have to look at two crucial parts of these brain regions called the Broca’s area and the Warnicke’s area.

The Broca’s area of the brain is responsible for verbal language output. The Warnicke’s area is responsible for comprehension, grammar, syntax, and structure.

In our waking life, these two brain areas work in partnership with each other, ensuring that we communicate effectively through reading, writing, and speech. But when we are asleep, the back and forth between these two regions is disrupted.

It seems that it’s the Warnicke’s area that is temporarily disabled as we dream, which directly affects how the Broca’s area functions. This is why people sometimes report saying and hearing strange, incomprehensible things in their dreams.

“Why has Sam left the chimney door open? We’ll lose all of the radishes if we’re not careful!” It’s as if the grammar and sentence structure work just fine, but the context of the words and their meanings is all mixed up

Despite scientists’ best efforts, the Broca’s and the Warnicke’s brain areas are still somewhat of a mystery. A lot more research needs to be done before they can conclusively determine what exactly is happening while we dream.

A lot more research needs to be done before they can conclusively determine what exactly is happening while we dream.

The One Percent

Interestingly, although the vast majority of people can’t read or process language during a dream, some can.

Studies show there’s a small section of the population, around just one percent, who do read in their dreams. And surprisingly, the majority of people in this group share a single profession; they’re writers.

Scientists believe this is because writers spend much more time thinking about words and language during their waking life than other people do.

And as we know, it’s the things we think about during the day that often appear in our dreams at night, even if they’re in our subconscious.

Lucid Dreaming

So we know that the vast majority of us cannot read during a regular dream state. But, there is another type of dream state in which it might just be possible; lucid dreaming.

Lucid dreaming is essentially being aware that you’re dreaming. But instead of immediately waking up, you stay in your dream state and can even control the things that happen within the dream.

But instead of immediately waking up, you stay in your dream state and can even control the things that happen within the dream.

During lucid dreaming, your language processing areas of the brain are not fully awake, but they are much more active. That means that reading while you’re dreaming is actually possible.

How to Practice Lucid Dreaming

There’s no sure-fire way to train your brain into lucid dreaming, but there are some tried and tested methods that can help.

Some sleep scientists suggest the Dream Test method. Essentially, this involves checking in with yourself regularly during your waking hours to ask one question: Am I dreaming right now?

To check if you are, try the following:

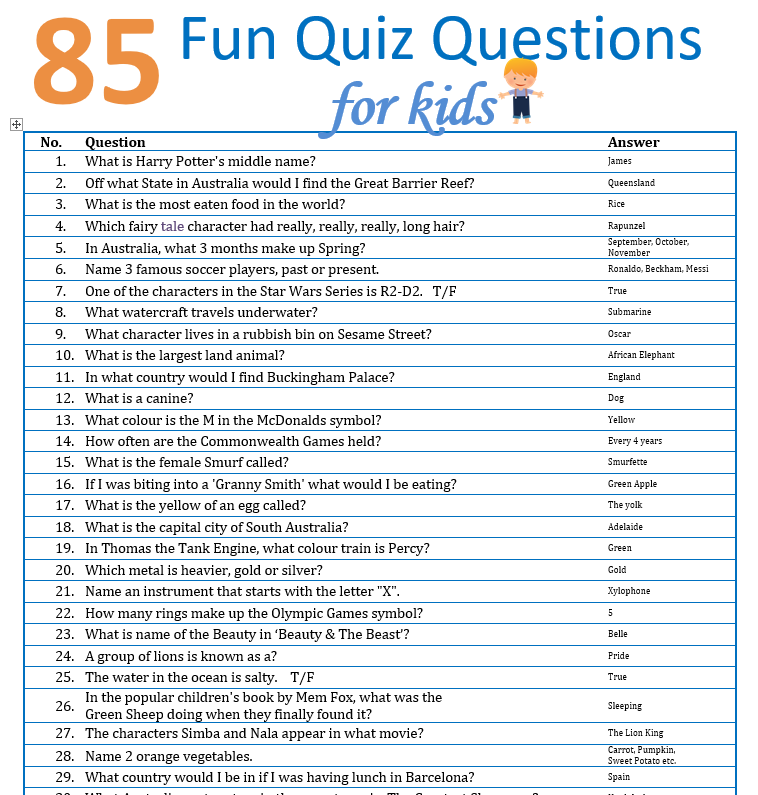

Read something: As we’ve discovered, most of us won’t be able to read words while we’re dreaming. Pick up a book, newspaper, or magazine. If you can read normally, you’re awake. If the words appear jumbled or they’re not there at all, you’re dreaming.

Look in the mirror: Most people will struggle to see their reflection in a dream. If you have an empty mirror staring back at your, or your face is blurred, you’re dreaming.

Look at your palms: This is another easy test to see if you’re in the waking world or the dreaming one. If your palms are smooth, or they look unfamiliar to you, you’re dreaming.

While these simple tests might seem a bit silly when you already know for certain that you’re awake, the point is to train yourself into a habit. If you do this on a daily basis for a few weeks or months, you may find that sooner or later, you’ll do it in a dream too.

Once you’re dreaming and you actually know you’re dreaming, that’s where the fun begins. You can choose to do whatever you want to in the dream, knowing that, since you’re definitely dreaming, there are no consequences.

And, strangely enough, you might find that you can dream read in this lucid state, at least a little bit. You have partially woken up, so your language processors are firing up enough to comprehend language, but you’re still not back in the waking world yet.

You have partially woken up, so your language processors are firing up enough to comprehend language, but you’re still not back in the waking world yet.

It’s unlikely you’ll be able to read anything substantial, and the words may always behave strangely, but lucid dream reading is still easier than reading in a regular dream state.

Conclusion: Can You Read in Your Dreams?

Of course, when we’re dreaming, our eyes are closed, which makes reading real-life books impossible. But scientists have found that only around 1% of people can even read imaginary ‘dream text’ while they’re in a regular dream state.

The closest chance we have of reading in our dreams is through the power of lucid dreaming. But if you manage to master the art of knowing you’re dreaming while you’re dreaming, you might choose to do something other than sit down with a good book.

120shares

Can you read in your dreams? Science reveals why most people can't

There’s a famous episode of Batman: The Animated Series where Bruce Wayne becomes trapped in a dream in which he’s no longer Batman. Something’s clearly wrong, but he can’t prove it — until he opens a newspaper and sees nothing but random symbols.

Something’s clearly wrong, but he can’t prove it — until he opens a newspaper and sees nothing but random symbols.

As Batman eloquently puts it at the end of that episode, “reading is a function of the right side of the brain, while dreams come from the left side.” In other words, the part of your brain used for reading can’t be reached when you’re dreaming. Batman’s reasoning isn’t perfect, but it’s pretty good for a kids’ cartoon. Harvard University dream expert and Assistant Professor of Psychology Deirdre Barrett, Ph.D. tells Inverse that dream research really does confirm that most of us can’t read in our dreams.

In fact, Barrett says most dreamers lose not just the ability to read but the capacity for language altogether.

“Most of it seems to have to do with our whole language area being much less active,” she says. “Even though people describe things where they’re with a group of friends, talking about something, if you really ask whether they heard voices and specific phrasings or sentences, the vast majority of people will say no. ”

”

When pressed to think about it, people will use the concept of “telepathy” to describe communication in those dreams.

Why can’t you read in your dreams?

Read or sleep, you can’t do both.Shutterstock

When we sleep, the entire language area of the brain is less active, making reading, writing, and even speaking very rare in dreams.

Wayne was right about the language-processing parts of the brain being mostly concentrated in the left hemisphere, but that isn’t a hard and fast rule. Some people share language-processing ability across both hemispheres, and in some people, it’s even concentrated on the right side. Furthermore, reading, in particular, involves the optic nerve, which processes the words you see, and, for people who read in Braille, even the touch-processing sensory cortex.

Nevertheless, the many parts of the brain that have to do with interpreting language are toward the back and middle of your brain and, in general, are much less active while we are asleep.

“Last night, I had a dream that my friend handed me a porcupine, and told me, ‘Don’t let him get away. He wants to run.’”

They include, crucially, two regions known as Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area. These two regions, named for the scientists who discovered them, have been crucial to determining what goes on in the brain’s language center when we are dreaming, says Barrett.

Broca’s area is the part of the brain that deals with forming and expressing language — that is, connecting meaning to words. Meanwhile, Wernicke’s area deals with grammar and syntax, allowing us to put words together in meaningful ways. Normally, they work together, allowing us to communicate in sentences. But in the rare few who manage to remember either reading, hearing, or speaking language in their dreams, the sentences that come out always suggest that Wernicke’s area is defective, says Barrett.

Broca's Area and Wernicke's area work in tandem to allow meaningful communication. PlayLingual

PlayLingual

In a talk she gave in 2014, she presented snippets of language that college students claimed to remember verbatim from their dreams. They make total sense grammatically, but they involve groups of words that don’t quite fit with each other — an observation that’s often made in people with a condition known as Wernicke’s aphasia:

“Last night, I had a dream that my friend handed me a porcupine, and told me, “Don’t let him get away. He wants to run.”

“I was hearing someone talking. I realized it was Adam West’s voice! [TV Batman]. The voice was saying ‘Lola was the guloff [God only knows what a “guloff” is, says Barrett] and Jeannie was his wife.’”

Weird statements like these suggest that Wernicke’s area, in particular, is the part of the brain’s language center that doesn’t function too well during sleep. However, Barrett says, scientists don’t know for sure, as there have not been any studies looking very carefully at whether there is more or less activity in Wernicke’s versus Broca’s areas.

Besides, she points out, “there’s a lot of variation between individuals, on average, and between one dream period and another.” She’s referring to the different dream states, which include deep sleep as well as REM sleep, the type associated with the most vivid types of dreams. Because so few studies wake people up during REM sleep to ask them what they remember, she says, there’s plenty left to learn about what role, if any, language plays in those dreams.

Why some people

can read in their dreamsArtwork paying homage to 'Kubla Khan', which Coleridge says came to him, verbatim, in a dream.

Nevertheless, it’s safe to say that most people don’t use language in an especially meaningful way when they sleep. But that’s what makes the people who do so extraordinary: This small class of people, Barrett says, overwhelmingly tends to be made up of writers — especially poets.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, she points out, famously wrote his classic poem Kubla Khan after seeing it in a dream (the poem’s subtitle, after all, is A Vision in a Dream: A Fragment). “There are a number of other poets who say they’ve dreamed one long stanza or three long stanzas — way more than most of us ever read in our dreams,” says Barrett.

“There are a number of other poets who say they’ve dreamed one long stanza or three long stanzas — way more than most of us ever read in our dreams,” says Barrett.

Part of the reason this is the case is because writers and poets think about language more than most people, and holding these thoughts in the mind immediately before sleep can influence the content of their dreams, she explains. But poets, in particular, may find the language contained in their dreams more useful than others.

“My belief about why poets seem so much likelier to dream usable things at any length is back to that Wernicke’s aphasia issue — poetry doesn’t need to make as tight logical sense,” says Barrett.

“There’s a lot of leeway in meaning.”

Most of us are unlikely to ever experience dream language in the same way. In 1996, a well-respected dream researcher Ernest Hartmann, Ph.D., published a seminal paper on what we do and don’t experience in our dreams, entitled “We Do Not Dream of the Three Rs. ” He was referring to reading, writing, and arithmetic — energy-intensive actions that overwhelm our day-to-day lives — and found that less than one percent of the people he surveyed experience them in their dreams.

” He was referring to reading, writing, and arithmetic — energy-intensive actions that overwhelm our day-to-day lives — and found that less than one percent of the people he surveyed experience them in their dreams.

For the 99 percent of us who don’t, there’s nothing left to do but appreciate the time off.

90,000 10 new scientific facts about dreams- William Park

- BBC Future

Author photo, Thinkstock

PIDSIS to the photo,Sleep still remains a mysterious phenomenon for scientists

SPA still remains one of the least studied phenomena in psychology and physiology. Correspondent William Park talks about some intriguing facts that have recently become known to scientists.

The science of sleep is a mysterious territory. Researchers are still not sure what happens in our brains during sleep that makes us dream, and what they mean. But in recent years, science has uncovered a few things about what happens to our brains in the arms of Morpheus.

But in recent years, science has uncovered a few things about what happens to our brains in the arms of Morpheus.

10 surprising facts about why we need a good night's sleep:

1. Familiar smells help form memories in the brain during sleep, improving your learning performance.

2. Starting of the body when we fall asleep is a very common phenomenon. It is completely harmless and is called "hypnotic jerks".

Image copyright, Thinkstock

Image caption,Playing wind instruments improves sleep

0033 Rev. ) promotes better sleep because it strengthens the muscles that are involved in the breathing process.

4. An analysis of human circadian biorhythms shows that the most natural time for daytime sleep is between 14:00 and 16:00. While naps in the afternoon are more conducive to recovery, a little rest around noon boosts creativity.

Skip the podcast and continue

podcast

What did it cost

The main story of today, how our journalists explain

Issues

End of the podcast

5. Research has shown that a mutation in the DEC2 gene allows some people to get a full four hours of sleep a night. No side effects on the body from such a short sleep were found in them.

Research has shown that a mutation in the DEC2 gene allows some people to get a full four hours of sleep a night. No side effects on the body from such a short sleep were found in them.

6. However, you are unlikely to belong to this group of people. Those who were lucky enough to get enough sleep in a few hours, no more than 5% on Earth. Most people need 8 hours of sleep. But about 30% do not allow themselves to sleep more than six hours a night.

7. One of the theories about why we need to sleep is that during sleep our brain organizes the memories and impressions it has received during the day. It seems that in dreams we can deal with memories of unpleasant or traumatic events.

8. Some researchers have been able to reconstruct the videos that people watch during the day on YouTube using the analysis of brain activity. Scientists are sure that the day when such a technique will help decipher dreams is not far off.

Image copyright, Thinkstock

Photo caption,12 nights of not getting enough sleep equals being drunk

so heavy.