Where does negative self talk come from

Causes of Negative Self Talk and How to Overcome It

Do you ever find yourself asking this question; why am I so negative about myself? You are not alone; research has found that of the thoughts we think throughout the day, 80 percent of them are negative.

This negativity impacts not only mental health but also physical health. Do you have a desire to learn how to overcome negative self-talk?

Are you wondering what is negative self-talk? Keep reading and learn everything you need to know about negative self-talk.

What Is Negative Self-Talk?

Do you ever hear the little voice in your head telling you that you are not good enough? Or that you will never get what you want or reach your goals?

That is negative self-talk. Take all the bad thoughts you have about yourself, and they all fall into this category.

What Causes Negative Self-Talk?

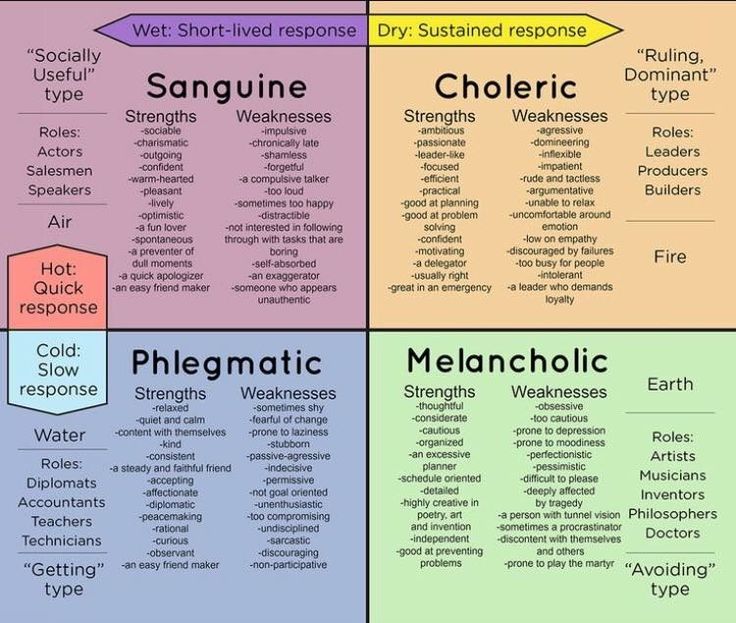

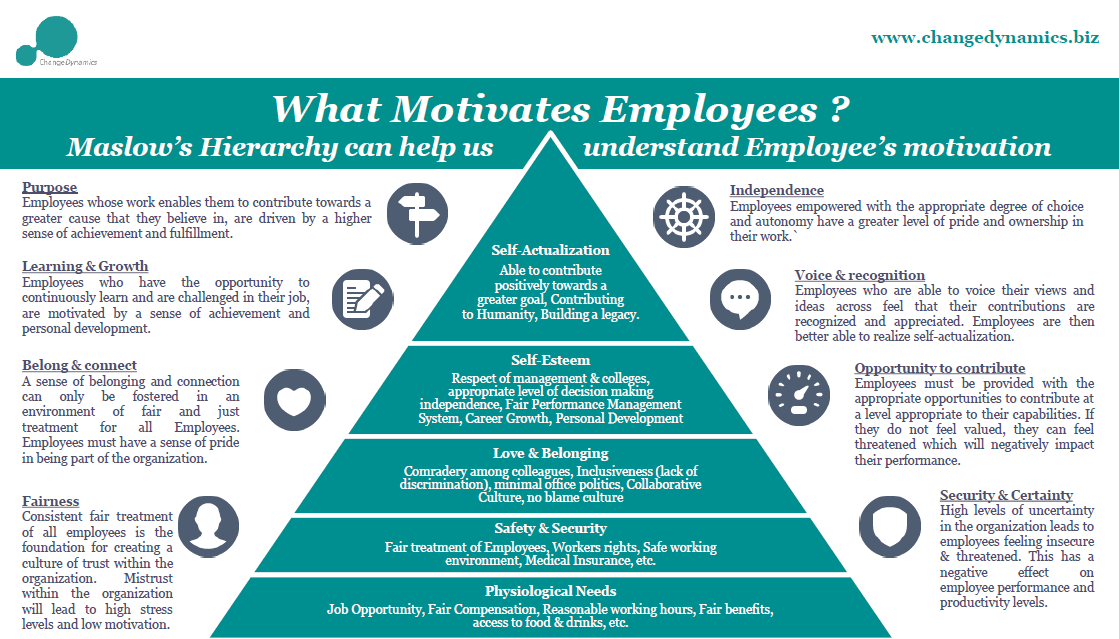

Negative self-talk can come from a place of depression, low self-confidence, and anxiety and be part of a more significant mental health concern. However, you may also have habits that are causing negative self-talk.

Some of these habits include:

- Not addressing relationship problems

- Poor health habits

- Too much time alone

- Not asking for help

- Failing to practice self-care

- Denying your negative self-talk experience

- Surrounding yourself with negative people

If you are regularly engaging in any of the above habits, they can cause negative self-talk.

Effects of Negative Self-Talk

Everyone gets down on themselves sometimes. So, what's the big deal about negative self-talk?

Constant negative self-talk can have many effects that go beyond the thoughts in your head.

Perfectionism

One of the effects of negative self-talk is perfectionism. In this instance, it's no longer good enough to be good or great. You must be perfect.

This need for perfection can have a significant impact on your life and cause additional stress.

Limited Thinking

How often is that little voice in your head telling you that you are not good enough or that you can't do it? Eventually, you will start believing the thoughts that are persistent within your head.

Physical Symptoms

The thoughts in your head can lead to changes in your hormones and biochemistry. This can begin to cause you to have physical symptoms.

Some of the physical symptoms you could experience include gastrointestinal or digestive problems.

Impact on Relationships

Negative self-talk can impact your relationships with others. These thoughts can make you seem needy or insecure.

In addition, these thoughts can cause you to shut yourself off and communicate poorly. If you have children, this can impact your relationship with them as well.

If your child sees you constantly criticizing yourself, they will learn that behavior as well. Part of helping a child with negative self-talk is learning how to help yourself.

Depressed Feelings

Negative self-talk can cause feelings of depression. These feelings can encourage even more negative self-talk, which creates a vicious circle.

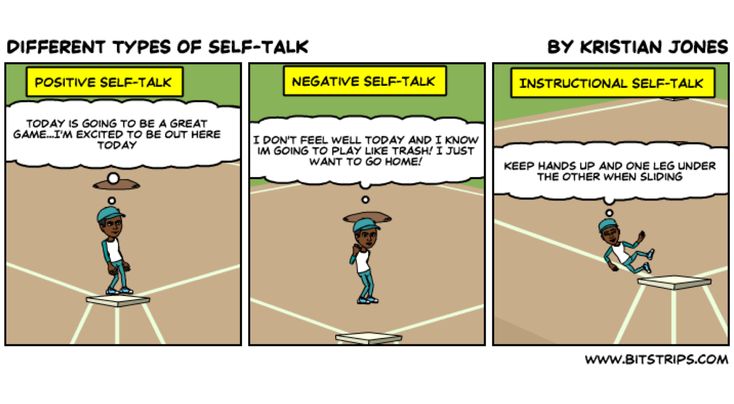

Positive and Negative Self-Talk Examples

How do you combat negativity and bad self-talk? One of the ways you can combat negative self-talk is through counseling.

In addition, learning what negative self-talk phrases look like can help.

This helps you learn to first identify them; you can then begin to replace talking bad about yourself with positive self-talk. The best way to combat negative self-talk is by fighting it with positive affirmations and taking away the power the negative thoughts have.

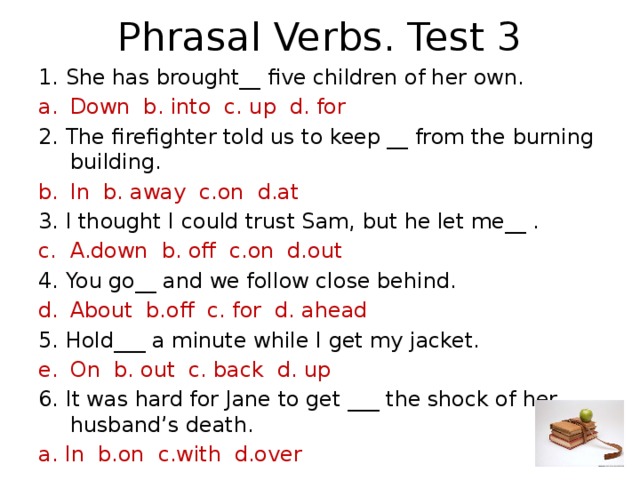

Negative Absolutes

"I always screw up" or "I will never get this right," are great examples of using absolutes in thinking. These thoughts are perfect examples of negative self-talk.

So how do you replace those thoughts? Once you recognize and notice these thoughts, tell yourself the opposite.

If your thought is that, "I always screw up," replace that thought with, "sometimes I make mistakes, but that's okay, I will learn and grow from those mistakes."

If your thought is, "I will never get this right," change that thought with this, "I am struggling with this, but I will get it."

Focusing on Negative Thoughts

"I'm fat." "I'm too tall."

"I'm a horrible athlete." "I'm dumb."

These are all examples of things you can tell yourself that are negative. These thoughts will chip away at you.

It can be hard to replace these thoughts when you believe them to be true. However, you can do it.

Try replacing these thoughts with positive thoughts. Anytime you catch yourself saying something negative about yourself, say five positives about yourself.

"I am smart." "I am loving."

"I am fun." "I am talented."

If needed, you can even surround yourself with these positives. Try writing affirmations on sticky notes and putting them places you will see throughout the day.

Personalizing

"Sally is upset. I must have done something to make her feel this way."

"No one wants to hang out. They must not want to spend time with me."

Personalizing can also be called mind reading. You believe you know what others are thinking about you.

Not only do you know what they are thinking, but it is negative. This form of negative self-talk is sneaky. It is also more difficult to combat and recognize.

However, you can not only recognize it but learn to combat it.

"Sally is upset. I wonder if something happened at work?"

"No one wants to hang out. They probably made plans already; I will call and ask about doing something another day."

Catastrophic Predicting

"I am going to fail." "I will not get the job."

In this type of negative self-talk, you convince yourself of a bad outcome. Even if there is no reason to believe that the worst will happen, you do.

When you catch yourself doing this, you can replace those thoughts as well.

"I might not be successful right away, but I will learn and succeed."

"I will put forth my best foot and do my best. I will get the job."

The worst part of catastrophic predicting is that it can cause you to create a self-fulfilling prophecy. Negative self-talk in this form can undercut your confidence. You believe you will fail, so you do.

Guilt

"I hurt Susan by doing this."

"I was late to work too many times, and I got fired."

When you reflect too much on feelings of guilt, it is negative self-talk. These feelings of guilt can influence you negatively.

Learning to replace these thoughts with positive self-talk is difficult. In part, because in this instance, you need to learn how to forgive yourself.

"I hurt Susan, but I learned from this mistake and grew. I need to forgive myself."

"I got fired for constantly being late to work. But I forgive myself and will use this experience to help me be better."

Stop Negative Self-Talk Today

What is negative self-talk? Negative self-talk is thoughts that interfere with who you are and have a huge impact. Start learning to replace those thoughts with positive self-talk.

Start learning to replace those thoughts with positive self-talk.

Write off 100% of your medical expenses

Are you an incorporated business owner with no employees? Learn how to use a Health Spending Account to pay for your medical expenses through your corporation:

Do you own a corporation with employees? Discover a tax deductible health and dental plan that has no premiums:

The Origin Of Your Negative Self-Talk

Our internal dialogue is running constantly. Much of it we keep up with, a lot of it we feel we have no control over.

The big question:

Is your self-talk serving you or sabotaging you?

Most of us are sabotaging ourselves a majority of the time. The voices in our head are judging us with a play-by-play on what we did wrong, the people we offended, and/or the opportunities we missed. The negative self-talk (inner critic) is either focused on painfully rehashing the past or fearfully rehearsing the future. (I will guarantee that it’s never in the here-and-now.)

(I will guarantee that it’s never in the here-and-now.)

So what’s the deal? Why does it feel so normal and common to be so hard on ourselves?

Here’s what I think it comes down to:

Deep within we hold a secret fear that we’re terrified of being confirmed. We’re unconsciously desperate to keep it from showing up; much of what we say and do are acts to convince ourselves and others that this fear is not true.

What’s your fear?

Want to know what’s motivating almost all of your negative self-talk? Simply answer yourself this:

What are you most afraid other people are going to FIND OUT or DECIDE about you?

Really give some thought to this and list it out. You might have a couple that pop out right away, things like: imposter, dumb, not good enough, lazy, weird…

Whatever comes up will feel familiar, and whatever stings or hits you in the gut are the ones to really pay attention to.

Now here’s the catch. Because you’ve come pretty far and are quite intelligent, your logic tells you that these fears aren’t true. You’ve probably become good at convincing yourself that these are silly untruths. Or your logic might be SO good, that you’re convinced you don’t even have these fears – that you can’t even answer this question because there is nothing to answer it with.

Chances are you’ve only convinced part of yourself. The conscious logical part of you knows these fears aren’t true and that maybe you don’t even have them, but sadly the conscious logical part of you isn’t running the show most of the time. The habitual running thought patterns in the background get a lot more airtime than you think. And it’s in those habitual running thought patterns where these fears reside.

Want to know how? Answer this:

What do you DO so that people don’t find out or decide you are those things you listed?

How do you show up in the world so that people don’t come to this conclusion about you?

Your answers could vary greatly. Some examples are: I distract myself with work, I accomplish a lot, I get others to like me, I’m a hard-ass, I procrastinate, I argue everything, I keep quiet, I never let myself rest…

Some examples are: I distract myself with work, I accomplish a lot, I get others to like me, I’m a hard-ass, I procrastinate, I argue everything, I keep quiet, I never let myself rest…

These things you DO are called survival mechanisms. They can also be considered your strong suits. These are the things you do in order to survive the fears you’re trying to keep hidden from yourself and others.

The fears you hold and the things you do to compensate for these false beliefs/fears are the origin of your negative self-talk.

The things you falsely decided about yourself a long time ago are propagating exactly the talk that’s frustratingly sabotaging you.

Calming and transforming the negative self-talk is a journey that doesn’t happen overnight. Beginning (or persisting in) this journey requires inquiry into this biggest fear you hide within.

Look and see what you find. See if uncovering these false beliefs can give you some awareness and insight into the sabotaging self-talk that’s keeping you from living the life of you desire. Only when you wake up and own what you’re falsely believing can you begin to make steps to change it. And when that starts to happen your entire world opens up to more possibility and joy!

Only when you wake up and own what you’re falsely believing can you begin to make steps to change it. And when that starts to happen your entire world opens up to more possibility and joy!

Leave me a comment and let me know what you think. Are you in touch with your biggest limiting beliefs? How does your negative self-talk sabotage your greatest efforts in living a life you love? Leave your thoughts and offer your experiences. And please feel free to share with those you know who strive to live purposefully. 🙂

Sign up here for my newsletter and get these articles in your inbox every other week.

Amy Eliza Wong is a life coach, writer, and speaker in the Sacramento, CA area committed to helping people figure out what makes them tick so they can finally live with joy and real purpose. Learn more about working with her.

« Previous Article Next Article »

why dialogue with oneself is dangerous - T&P

In psychology, internal dialogue is one of the forms of thinking, the process of a person communicating with himself.

It becomes the result of the interaction of different ego states: "child", "adult" and "parent". The inner voice often criticizes us, gives advice, appeals to common sense. But is he right? T&P asked several people from different fields what their inner voices sound like and asked a psychologist to comment on this.

It becomes the result of the interaction of different ego states: "child", "adult" and "parent". The inner voice often criticizes us, gives advice, appeals to common sense. But is he right? T&P asked several people from different fields what their inner voices sound like and asked a psychologist to comment on this. Internal dialogue has nothing to do with schizophrenia. Everyone has voices in their heads: it is we ourselves (our personality, character, experience) who speak to ourselves, because our Self consists of several parts, and the psyche is very complex. Thinking and reflection are impossible without an internal dialogue. Not always, however, it is framed as a conversation, and not always some of the remarks seem to be uttered by the voices of other people - as a rule, relatives. The “voice in the head” can also sound like one’s own, or it can “belong” to a completely stranger: a classic of literature, a favorite singer.

From the point of view of psychology, internal dialogue is a problem only if it develops so actively that it begins to interfere with a person in everyday life: it distracts him, confuses him. But more often this silent conversation "with oneself" becomes material for analysis, a field for finding sore spots and a testing ground for developing a rare and valuable ability to understand and support oneself.

But more often this silent conversation "with oneself" becomes material for analysis, a field for finding sore spots and a testing ground for developing a rare and valuable ability to understand and support oneself.

Roman

sociologist, marketer

It is difficult for me to distinguish any characteristics of the inner voice: shades, timbre, intonations. I understand that this is my voice, but I hear it in a completely different way, not like the others: it is more booming, low, rough. Usually in the internal dialogue, I imagine the acting role model of some situation, hidden direct speech. For example, what would I say to this or that public (despite the fact that the public can be very different: from casual passers-by to clients of my company). I need to convince them, to convey my idea to them. Usually I also play intonations, emotions and expression.

At the same time, there is no discussion as such: there is an internal monologue with reflections like: “What if?”. Does it happen that I myself call myself an idiot? It happens. But this is not a condemnation, but rather something between annoyance and a statement of fact.

Does it happen that I myself call myself an idiot? It happens. But this is not a condemnation, but rather something between annoyance and a statement of fact.

If I need an outside opinion, I change the prism: for example, I try to imagine what one of the classics of sociology would say. In terms of sound, the voices of the classics are no different from mine: I remember exactly logic and "optics". I can clearly distinguish alien voices only in a dream, and they are accurately modeled by real counterparts.

Anastasia

prepress specialist

In my case, the inner voice sounds like my own. Basically, he says: "Nastya, stop it", "Nastya, don't be stupid" and "Nastya, you're a fool!". This voice appears infrequently: when I feel uncollected, when my own actions make me dissatisfied. The voice is not angry - rather irritated.

I have never heard in my thoughts either my mother's, or my grandmother's, or anyone else's voice: only my own. He can scold me, but within certain limits: without humiliation. This voice is more like my coach: it presses the buttons that encourage me to take action.

This voice is more like my coach: it presses the buttons that encourage me to take action.

Ivan

screenwriter

What I hear in my mind is not formed as a voice, but I recognize this person by the structure of my thoughts: she looks like my mother. And even more precisely: it is an "internal editor" that explains how to make the mother like it. For me, as a hereditary filmmaker, this is an unflattering name, because in the Soviet years for a creative person (director, writer, playwright) an editor is a stupid protege of the regime, a not very educated censor who revels in his own power. It is unpleasant to realize that this type in you censors thoughts and clips the wings of creativity in all areas.

The "internal editor" gives many of his comments on the case. However, the question lies in the purpose of this "case". To summarize, he says: "Be like everyone else and don't stick your head out." He feeds the inner coward. “You need to be an excellent student,” because it eliminates problems. Everyone likes it. He makes it difficult to understand what I myself want, whispers that comfort is good, and the rest later. This editor doesn't really let me be an adult in the good sense of the word. Not in the sense of dullness and lack of play space, but in the sense of the maturity of the individual.

Everyone likes it. He makes it difficult to understand what I myself want, whispers that comfort is good, and the rest later. This editor doesn't really let me be an adult in the good sense of the word. Not in the sense of dullness and lack of play space, but in the sense of the maturity of the individual.

I hear my inner voice mostly in situations that remind me of my childhood, or when a direct display of creativity and fantasy is needed. Sometimes I succumb to the "editor" and sometimes I don't. The most important thing is to recognize his intervention in time. Because he disguises himself well, hiding behind pseudological conclusions that do not really make sense. If I recognized him, then I try to understand what the problem is, what I myself want and where the truth really is. When this voice, for example, interferes with my creativity, I try to stop and go into the space of "complete emptiness", starting all over again. The difficulty lies in the fact that the "editor" can be difficult to distinguish from simple common sense. To do this, you need to listen to your intuition, move away from the meaning of words and concepts. Often this helps.

To do this, you need to listen to your intuition, move away from the meaning of words and concepts. Often this helps.

Irina

translator

My internal dialogue is designed as the voices of my grandmother and Masha's friend. These are people whom I considered close and important: I lived with my grandmother in my childhood, and Masha was there at a difficult time for me. Grandma's voice says that I have crooked hands and that I'm clumsy. And Masha's voice repeats different things: that I again got in touch with the wrong people, I lead the wrong lifestyle and do the wrong things. They both always judge me. At the same time, voices appear at different moments: when something doesn’t work out for me, my grandmother “says”, and when everything works out for me and I feel good, Masha.

I react aggressively to these voices: I try to silence them, I argue with them mentally. I tell them back that I know better what and how to do with my life. Most often, I manage to argue with my inner voice. But if not, I feel guilty and feel bad.

But if not, I feel guilty and feel bad.

Kira

prose editor

In my mind I sometimes hear my mother's voice, which condemns me and devalues my achievements, doubts me. This voice is always dissatisfied with me and says: “What are you talking about! Are you out of your mind? Do better profitable business: you have to earn. Or: "You must live like everyone else." Or: "You will not succeed: you are nobody." It appears if I have to take a bold step or take a risk. In such situations, the inner voice, as it were, tries to manipulate me (“mom is upset”) to persuade me to the safest and most unremarkable course of action. To make him happy, I must be inconspicuous, diligent, and everyone likes me.

I also hear my own voice: he calls me not by my name, but by a nickname that my friends have come up with. He usually sounds a bit annoyed but friendly and says, “So. Stop”, “Well, what are you, baby” or “Everything, come on.” It encourages me to focus or take action.

Ilya Shabshin

counseling psychologist, leading specialist of the Psychological Center on Volkhonka

This whole selection speaks of what psychologists are well aware of: most of us have a very strong inner critic. We communicate with ourselves mainly in the language of negativity and rude words, using the whip method, and we have practically no self-support skills.

In Roman's commentary, I liked the technique, which I would even call psychotechnics: "If I need an outside opinion, I try to imagine what one of the classics of sociology would say." This technique can be used by people of different professions. In Eastern practices, there is even the concept of an "inner teacher" - a deep wise inner knowledge that you can turn to when it's hard for you. A professional usually has one or another school or authoritative figures behind him. Imagine one of them and ask what he would say or do is a productive approach.

An illustrative illustration of the general theme is Anastasia's commentary. A voice that sounds like your own and says: “Nastya, you are a fool! Don't be dumb. Stop it,” is, of course, according to Eric Berne, the Critical Parent. It is especially bad that the voice appears when she feels "uncollected", if her own actions cause dissatisfaction - that is, when, in theory, the person just needs to be supported. And instead, the voice tramples into the ground... And although Anastasia writes that he acts without humiliation, this is a small consolation. Maybe, as a “coach”, he presses the wrong buttons, and it’s not worth kicking, not reproaching, not insulting him to encourage himself to action? But, I repeat, such interaction with oneself is, unfortunately, typical.

A voice that sounds like your own and says: “Nastya, you are a fool! Don't be dumb. Stop it,” is, of course, according to Eric Berne, the Critical Parent. It is especially bad that the voice appears when she feels "uncollected", if her own actions cause dissatisfaction - that is, when, in theory, the person just needs to be supported. And instead, the voice tramples into the ground... And although Anastasia writes that he acts without humiliation, this is a small consolation. Maybe, as a “coach”, he presses the wrong buttons, and it’s not worth kicking, not reproaching, not insulting him to encourage himself to action? But, I repeat, such interaction with oneself is, unfortunately, typical.

You can induce yourself to action by first removing your fears by saying to yourself: “Nastya, everything is fine. It's okay, we'll figure it out." Or: "Here, look: it turned out well." "Yes, well done, you can do it!". “Do you remember how you did everything great then?” This method is suitable for any person who tends to criticize himself.

The last paragraph in Ivan's text is important: it describes the psychological algorithm for dealing with the inner critic. Point one: "Recognize interference." This problem often arises: something negative is disguised under the guise of useful statements, penetrates a person’s soul and establishes its own rules there. Then the analyst turns on, trying to understand what the problem is. According to Eric Berne, this is the adult part of the psyche, the rational one. Ivan even has author's tricks: "go out into the space of complete emptiness", "listen to intuition", "depart from the meaning of words and understand everything". Great, that's how it's supposed to be! Based on general rules and a common understanding of what is happening, it is necessary to find your own approach to what is happening. As a psychologist, I applaud Ivan: he has learned to talk to himself well. Well, what he fights is a classic: the internal editor is still the same critic.

“At school we are taught to extract square roots and carry out chemical reactions, but they don’t teach us to communicate normally with ourselves anywhere”

Ivan has another interesting observation: “You need to keep a low profile and be an excellent student. ” Kira notes the same. Her inner voice also says that she should be invisible and everyone should like her. But this voice introduces its own, alternative logic, because you can either be the best or keep a low profile. However, such statements are not taken from reality: these are all internal programs, psychological attitudes from various sources.

” Kira notes the same. Her inner voice also says that she should be invisible and everyone should like her. But this voice introduces its own, alternative logic, because you can either be the best or keep a low profile. However, such statements are not taken from reality: these are all internal programs, psychological attitudes from various sources.

The “keep your head down” attitude (like most others) comes from upbringing: in childhood and adolescence, a person draws conclusions about how to live, gives himself instructions based on what he hears from parents, educators, and teachers.

In this regard, the example of Irina looks sad. Close and important people - a grandmother and a friend - tell her: "You have crooked hands, and you are clumsy", "you live wrong." A vicious circle arises: her grandmother condemns her when something does not work out, and her friend when everything is fine. Total criticism! Neither when it is good, nor when it is bad, there is no support and consolation. Always a minus, always a negative: either you are clumsy, or something else is wrong with you.

Always a minus, always a negative: either you are clumsy, or something else is wrong with you.

But Irina is doing well, she behaves like a fighter: she silences voices or argues with them. This is how it should be done: the power of the critic, whoever he may be, must be weakened. Irina says that most often she gets votes over an argument - this phrase suggests that the opponent is strong. And in this regard, I would suggest that she try other ways: firstly (since she hears it as a voice), imagine that it comes from the radio, and she turns the volume knob towards the minimum, so that the voice fades, it gets worse heard. Then, probably, his power will weaken, and it will become easier to outguess him - or even just brush him off. After all, such an internal struggle creates quite a lot of tension. Moreover, Irina writes at the end that she feels guilty if she fails to argue.

Negative ideas penetrate deeply into our psyche in the early stages of its development, especially easily in childhood, when they come from big authoritative figures with whom, in fact, it is impossible to argue. The child is small, and around him are huge, important, strong masters of this world - adults on whom his life depends. You can't really argue here.

The child is small, and around him are huge, important, strong masters of this world - adults on whom his life depends. You can't really argue here.

In adolescence, we also solve difficult problems: we want to show ourselves and others that you are already an adult, and not a little one, although in fact, in the depths of your soul, you understand that this is not entirely true. Many teenagers become vulnerable, although outwardly they look prickly. At this time, statements about yourself, about your appearance, about who you are and what you are, sink into the soul and later become dissatisfied with inner voices that scold and criticize. We talk to ourselves so badly, so nastily, as we would never talk to other people. You would never say anything like that to a friend - and in your head your voices towards you easily allow yourself to do so.

To correct them, first of all, you need to realize: “The things that sound in my head are not always good thoughts. There may be opinions and judgments that were simply learned once. They don’t help me, it’s not useful for me, and their advice doesn’t lead to anything good.” You need to learn to recognize them and deal with them: to refute, muffle or otherwise remove the inner critic from yourself, replacing it with an inner friend who provides support, especially when it’s bad or difficult.

They don’t help me, it’s not useful for me, and their advice doesn’t lead to anything good.” You need to learn to recognize them and deal with them: to refute, muffle or otherwise remove the inner critic from yourself, replacing it with an inner friend who provides support, especially when it’s bad or difficult.

At school, we are taught to extract square roots and carry out chemical reactions, but nowhere is it taught to communicate normally with oneself. And you need to cultivate healthy self-support instead of self-criticism. Of course, you do not need to draw a halo of holiness around your own head. When it is difficult, you need to be able to cheer yourself up, support, praise, remind yourself of successes, achievements and strengths. Do not humiliate yourself as a person. Say to yourself: “In a specific area, at a specific moment, I can make a mistake. But this has nothing to do with my human dignity. My dignity, my positive attitude towards myself as a person is an unshakable foundation. And mistakes are normal and even good: I will learn from them, I will develop and move on.”

And mistakes are normal and even good: I will learn from them, I will develop and move on.”

Icons: Justin Alexander from the Noun Project

Why it's okay to talk to yourself and how this habit can make you more effective

Everyone does it: they have an internal monologue. It is part of the constant stream of consciousness that cannot be absent when we are awake. How to learn to talk to yourself correctly, our friends from the Reminder project tell.

“Okay, romantic moment, tell her something. Tell me how you crushed a pony. No, she likes ponies, I guess... Ask how long ago she had tests. What the hell is in my head? Lord, what a huge leg she has, tell her about it. No, don't talk, shut up! So, the pause dragged on, we must at least say something. Approximately such internal monologues were scrolled in the head by the protagonist of "Clinic", one of the most believable medical series.

Like him, many talk to themselves or hear an inner voice—when they are alone in a car, when they get bored in line, when they try to sleep, and so on. I sometimes talk to myself out loud - most often these are sarcastic comments if I did something ridiculous, or voicing what I should do, for example: "Now I'll do the dishes, and then I have to get dressed and go to the store." Sometimes all this makes you wonder: is it okay to talk to yourself if we invented speech to communicate with others?

I sometimes talk to myself out loud - most often these are sarcastic comments if I did something ridiculous, or voicing what I should do, for example: "Now I'll do the dishes, and then I have to get dressed and go to the store." Sometimes all this makes you wonder: is it okay to talk to yourself if we invented speech to communicate with others?

This is embarrassing for many people to admit, but talking to yourself is completely normal and very common, psychotherapist Laura Dabney reassures. This is not something you “need to grow out of” and certainly not a sign of psychological problems. Moreover, psychiatrists call internal (or voiced) monologues a healthy practice. Firstly, they can be a way to get rid of negative emotions, such as fear, nervousness, anger or guilt. And secondly, they help organize thoughts, plan actions and consolidate memory.

The “inner voice” has been studied since the beginning of psychology. The Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky made the observation that young children begin to talk to themselves at the same time that they learn to talk to others, and first they do it out loud and then to themselves. Such behavior - an internal monologue that sometimes breaks into speech - we retain for life.

Such behavior - an internal monologue that sometimes breaks into speech - we retain for life.

Over the past few decades, we have learned that when talking to yourself, a person makes the smallest movements with the muscles of the larynx, and Broca's center is activated in the brain - the area responsible for the motor organization of speech. If the work of Broca's center is disturbed, the ability to conduct an internal monologue is also violated. That is, the same tools in the brain are used for internal conversation and articulated speech.

Another confirmation of this is the operation of the efferent copy mechanism. This is a signal that helps the body to distinguish the processes that we cause ourselves from external stimuli. A prime example is tickling: if we try to tickle ourselves, the brain “predicts” that the touch is due to our own movements, and the tickling sensation is extinguished.

The same signal operates when we talk to ourselves. Experiments have shown that the brain "mutes" the effect of other external sounds when we speak aloud.

Another interesting experiment found that the inner voice seems to help us to cope better with everyday tasks. Animals performing tasks to correlate two stimuli (the so-called matching tasks - tasks when the subject is shown an object and then asked to choose the same one from those in front of it) activate different parts of the brain depending on whether the stimulus was visual or auditory . We, humans, “turn on” several areas of the brain, regardless of the stimulus perception system.

But if a person is asked to mumble some meaningless word under his breath, for example, "blah blah blah" - and therefore deprive him of the opportunity to use his inner voice - he will behave (in a sense) as animal. That is, when performing tasks with visual or auditory stimuli, zones in his brain are activated that are responsible for either vision or hearing.

Interestingly, speaking thoughts out loud may have a different effect than speaking them silently. In one small experiment, psychologists at Bangor University in the UK asked one group of volunteers to read instructions for a task to themselves while another group read aloud. Those who read the instructions aloud performed better than the participants who sat in silence.

Those who read the instructions aloud performed better than the participants who sat in silence.

This is why it is not surprising that many people use self-talk to get things done. For example, this is what athletes do (very often tennis players), who, at critical moments, cheer themselves up with motivating (“Come on, you can!”) Or instructing phrases.

Unfortunately, although the inner voice can help us control our behavior and improve results, it can be a problem. For example, it can interfere with sleep just when it is needed. And self-digging, rumination (constant scrolling in the head of the same thought) and negative words about oneself are associated with the development of depression. In addition, people suffering from depression cannot stop the flow of thoughts in their head, even when they need to focus on something else.

It turns out that, on the one hand, we need conversations with ourselves, and on the other hand, the ability to use them to our advantage is important here — that is, to get rid of useless thoughts and include those related to current tasks. It takes time to learn how to do this, but the goal is quite achievable. Here are some tips that psychologists give. More precisely, not even advice, but ideas that should be remembered.

It takes time to learn how to do this, but the goal is quite achievable. Here are some tips that psychologists give. More precisely, not even advice, but ideas that should be remembered.

- Talking to yourself is normal. The internal monologue is part of a constant stream of consciousness that cannot be absent when we are awake. According to some estimates, the speed of internal speech is up to 4000 words per minute, 10 times faster than oral speech. If a person really has serious psychological disorders, for example, schizophrenia, he can also talk to himself, but there is a difference: he is talking with voices that he perceives as outsiders, while in a normal internal monologue we know for sure that the author is this is us.

- Negative self-talk is also normal, but up to certain limits. Usually psychologists call to get rid of negativity in conversations with oneself, to eradicate thoughts like “I can’t do it”, “I don’t deserve this”, and so on. But some experts point out that in principle there is nothing wrong with thoughts with a negative coloring, because evolution taught us to do so.

“Two-thirds of our daily thoughts are negative,” says Sherry Benton, a former professor emeritus at the University of Florida. “They warn us of danger, help us analyze past actions, and help us understand who we are. All this gave us a chance to survive when we were hunters and gatherers. If 1/3 of the internal dialogue can be called positive and self-affirming, then you are doing a great job.

“Two-thirds of our daily thoughts are negative,” says Sherry Benton, a former professor emeritus at the University of Florida. “They warn us of danger, help us analyze past actions, and help us understand who we are. All this gave us a chance to survive when we were hunters and gatherers. If 1/3 of the internal dialogue can be called positive and self-affirming, then you are doing a great job. - However, an excessive amount of self-criticism and reproaches in the internal monologue is an alarming sign. The internal narrative is connected with emotions, and if it is gloomy, it can lead to anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts.

- The internal monologue will be useful if it is neutral. If he relies on facts, if mistakes are perceived not as a disaster, but as something that can be avoided next time, if the feeling of guilt for small misconduct passes relatively quickly. This is not the same as positive thinking. It is better to replace negative phrases in a conversation with yourself not with positive statements, but with neutral and “applied” ones.

Learn more