10 brain myths

Top Ten Myths About the Brain | Science

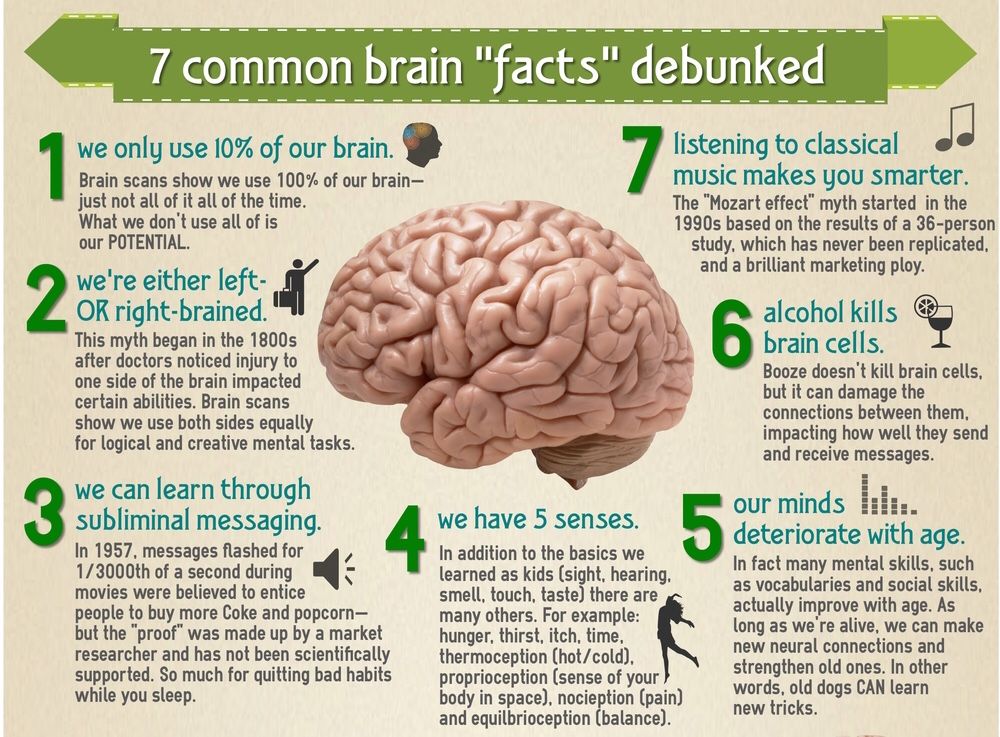

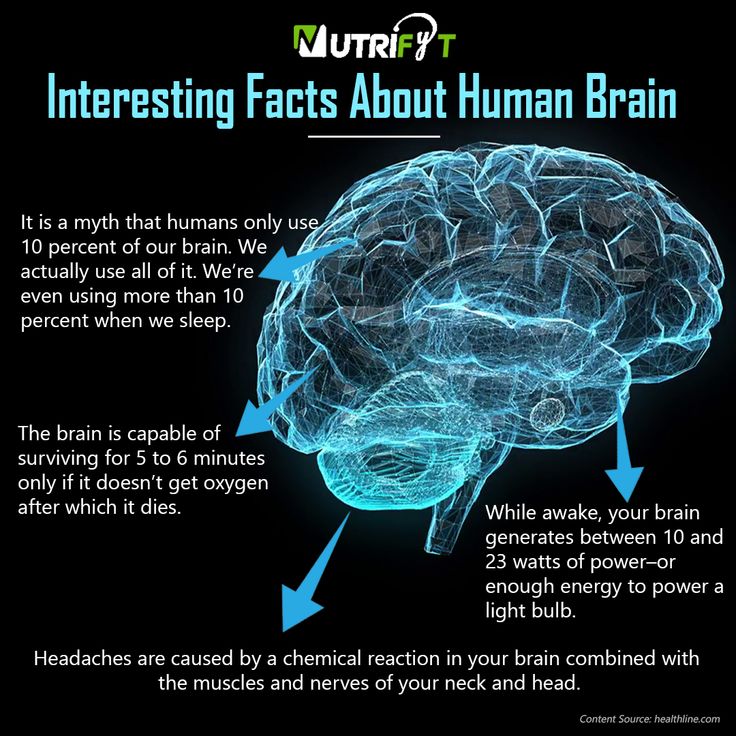

Repeated in pop culture for a century, the notion that humans only use 10 percent of our brains is false. Scans have shown that much of the brain is engaged even during simple tasks. Allen Bell / Corbis1. We use only 10 percent of our brains.

This one sounds so compelling—a precise number, repeated in pop culture for a century, implying that we have huge reserves of untapped mental powers. But the supposedly unused 90 percent of the brain is not some vestigial appendix. Brains are expensive—it takes a lot of energy to build brains during fetal and childhood development and maintain them in adults. Evolutionarily, it would make no sense to carry around surplus brain tissue. Experiments using PET or fMRI scans show that much of the brain is engaged even during simple tasks, and injury to even a small bit of brain can have profound consequences for language, sensory perception, movement or emotion.

True, we have some brain reserves. Autopsy studies show that many people have physical signs of Alzheimer’s disease (such as amyloid plaques among neurons) in their brains even though they were not impaired. Apparently we can lose some brain tissue and still function pretty well. And people score higher on IQ tests if they’re highly motivated, suggesting that we don’t always exercise our minds at 100 percent capacity.

2. “Flashbulb memories” are precise, detailed and persistent.

We all have memories that feel as vivid and accurate as a snapshot, usually of some shocking, dramatic event—the assassination of President Kennedy, the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger, the attacks of September 11, 2001. People remember exactly where they were, what they were doing, who they were with, what they saw or heard. But several clever experiments have tested people’s memory immediately after a tragedy and again several months or years later. The test subjects tend to be confident that their memories are accurate and say the flashbulb memories are more vivid than other memories. Vivid they may be, but the memories decay over time just as other memories do. People forget important details and add incorrect ones, with no awareness that they’re recreating a muddled scene in their minds rather than calling up a perfect, photographic reproduction.

Vivid they may be, but the memories decay over time just as other memories do. People forget important details and add incorrect ones, with no awareness that they’re recreating a muddled scene in their minds rather than calling up a perfect, photographic reproduction.

3. It’s all downhill after 40 (or 50 or 60 or 70).

It’s true, some cognitive skills do decline as you get older. Children are better at learning new languages than adults—and never play a game of concentration against a 10-year-old unless you’re prepared to be humiliated. Young adults are faster than older adults to judge whether two objects are the same or different; they can more easily memorize a list of random words, and they are faster to count backward by sevens.

But plenty of mental skills improve with age. Vocabulary, for instance—older people know more words and understand subtle linguistic distinctions. Given a biographical sketch of a stranger, they’re better judges of character. They score higher on tests of social wisdom, such as how to settle a conflict. And people get better and better over time at regulating their own emotions and finding meaning in their lives.

They score higher on tests of social wisdom, such as how to settle a conflict. And people get better and better over time at regulating their own emotions and finding meaning in their lives.

4. We have five senses.

Sure, sight, smell, hearing, taste and touch are the big ones. But we have many other ways of sensing the world and our place in it. Proprioception is a sense of how our bodies are positioned. Nociception is a sense of pain. We also have a sense of balance—the inner ear is to this sense as the eye is to vision—as well as a sense of body temperature, acceleration and the passage of time.

Compared with other species, though, humans are missing out. Bats and dolphins use sonar to find prey; some birds and insects see ultraviolet light; snakes detect the heat of warmblooded prey; rats, cats, seals and other whiskered creatures use their “vibrissae” to judge spatial relations or detect movements; sharks sense electrical fields in the water; birds, turtles and even bacteria orient to the earth’s magnetic field lines.

By the way, have you seen the taste map of the tongue, the diagram showing that different regions are sensitive to salty, sweet, sour or bitter flavors? Also a myth.

5. Brains are like computers.

We speak of the brain’s processing speed, its storage capacity, its parallel circuits, inputs and outputs. The metaphor fails at pretty much every level: the brain doesn’t have a set memory capacity that is waiting to be filled up; it doesn’t perform computations in the way a computer does; and even basic visual perception isn’t a passive receiving of inputs because we actively interpret, anticipate and pay attention to different elements of the visual world.

There’s a long history of likening the brain to whatever technology is the most advanced, impressive and vaguely mysterious. Descartes compared the brain to a hydraulic machine. Freud likened emotions to pressure building up in a steam engine. The brain later resembled a telephone switchboard and then an electrical circuit before evolving into a computer; lately it’s turning into a Web browser or the Internet. These metaphors linger in clichés: emotions put the brain “under pressure” and some behaviors are thought to be “hard-wired.” Speaking of which...

These metaphors linger in clichés: emotions put the brain “under pressure” and some behaviors are thought to be “hard-wired.” Speaking of which...

6. The brain is hard-wired.

This is one of the most enduring legacies of the old “brains are electrical circuits” metaphor. There’s some truth to it, as with many metaphors: the brain is organized in a standard way, with certain bits specialized to take on certain tasks, and those bits are connected along predictable neural pathways (sort of like wires) and communicate in part by releasing ions (pulses of electricity).

But one of the biggest discoveries in neuroscience in the past few decades is that the brain is remarkably plastic. In blind people, parts of the brain that normally process sight are instead devoted to hearing. Someone practicing a new skill, like learning to play the violin, “rewires” parts of the brain that are responsible for fine motor control. People with brain injuries can recruit other parts of the brain to compensate for the lost tissue.

People with brain injuries can recruit other parts of the brain to compensate for the lost tissue.

7. A conk on the head can cause amnesia.

Next to babies switched at birth, this is a favorite trope of soap operas: Someone is in a tragic accident and wakes up in the hospital unable to recognize loved ones or remember his or her own name or history. (The only cure for this form of amnesia, of course, is another conk on the head.)

In the real world, there are two main forms of amnesia: anterograde (the inability to form new memories) and retrograde (the inability to recall past events). Science’s most famous amnesia patient, H.M., was unable to remember anything that happened after a 1953 surgery that removed most of his hippocampus. He remembered earlier events, however, and was able to learn new skills and vocabulary, showing that encoding “episodic” memories of new experiences relies on different brain regions than other types of learning and memory do. Retrograde amnesia can be caused by Alzheimer’s disease, traumatic brain injury (ask an NFL player), thiamine deficiency or other insults. But a brain injury doesn’t selectively impair autobiographical memory—much less bring it back.

Retrograde amnesia can be caused by Alzheimer’s disease, traumatic brain injury (ask an NFL player), thiamine deficiency or other insults. But a brain injury doesn’t selectively impair autobiographical memory—much less bring it back.

8. We know what will make us happy.

In some cases we haven’t a clue. We routinely overestimate how happy something will make us, whether it’s a birthday, free pizza, a new car, a victory for our favorite sports team or political candidate, winning the lottery or raising children. Money does make people happier, but only to a point—poor people are less happy than the middle class, but the middle class are just as happy as the rich. We overestimate the pleasures of solitude and leisure and underestimate how much happiness we get from social relationships.

On the flip side, the things we dread don’t make us as unhappy as expected. Monday mornings aren’t as unpleasant as people predict. Seemingly unendurable tragedies—paralysis, the death of a loved one—cause grief and despair, but the unhappiness doesn’t last as long as people think it will.![]() People are remarkably resilient.

People are remarkably resilient.

9. We see the world as it is.

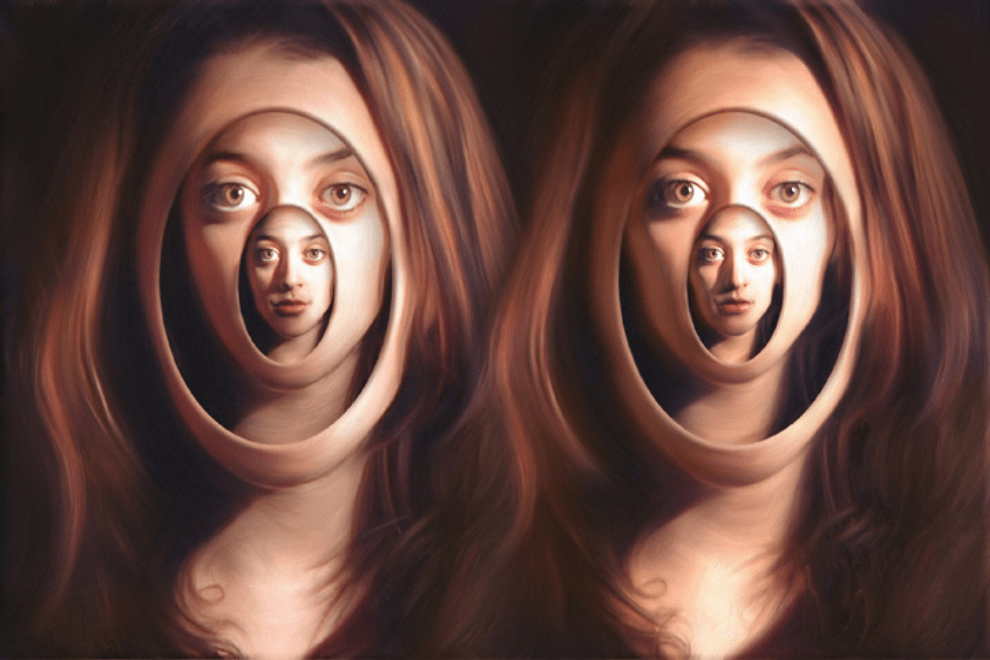

We are not passive recipients of external information that enters our brain through our sensory organs. Instead, we actively search for patterns (like a Dalmatian dog that suddenly appears in a field of black and white dots), turn ambiguous scenes into ones that fit our expectations (it’s a vase; it’s a face) and completely miss details we aren’t expecting. In one famous psychology experiment, about half of all viewers told to count the number of times a group of people pass a basketball do not notice that a guy in a gorilla suit is hulking around among the ball-throwers.

We have a limited ability to pay attention (which is why talking on a cellphone while driving can be as dangerous as drunk driving), and plenty of biases about what we expect or want to see. Our perception of the world isn’t just “bottom-up”—built of objective observations layered together in a logical way. It’s “top-down,” driven by expectations and interpretations.

10. Men are from Mars, women are from Venus.

Some of the sloppiest, shoddiest, most biased, least reproducible, worst designed and most overinterpreted research in the history of science purports to provide biological explanations for differences between men and women. Eminent neuroscientists once claimed that head size, spinal ganglia or brain stem structures were responsible for women’s inability to think creatively, vote logically or practice medicine. Today the theories are a bit more sophisticated: men supposedly have more specialized brain hemispheres, women more elaborate emotion circuits. Though there are some differences (minor and uncorrelated with any particular ability) between male and female brains, the main problem with looking for correlations with behavior is that sex differences in cognition are massively exaggerated.

Women are thought to outperform men on tests of empathy. They do—unless test subjects are told that men are particularly good at the test, in which case men perform as well as or better than women. The same pattern holds in reverse for tests of spatial reasoning. Whenever stereotypes are brought to mind, even by something as simple as asking test subjects to check a box next to their gender, sex differences are exaggerated. Women college students told that a test is something women usually do poorly on, do poorly. Women college students told that a test is something college students usually do well on, do well. Across countries—and across time—the more prevalent the belief is that men are better than women in math, the greater the difference in girls’ and boys’ math scores. And that’s not because girls in Iceland have more specialized brain hemispheres than do girls in Italy.

The same pattern holds in reverse for tests of spatial reasoning. Whenever stereotypes are brought to mind, even by something as simple as asking test subjects to check a box next to their gender, sex differences are exaggerated. Women college students told that a test is something women usually do poorly on, do poorly. Women college students told that a test is something college students usually do well on, do well. Across countries—and across time—the more prevalent the belief is that men are better than women in math, the greater the difference in girls’ and boys’ math scores. And that’s not because girls in Iceland have more specialized brain hemispheres than do girls in Italy.

Certain sex differences are enormously important to us when we’re looking for a mate, but when it comes to most of what our brains do most of the time—perceive the world, direct attention, learn new skills, encode memories, communicate (no, women don’t speak more than men do), judge other people’s emotions (no, men aren’t inept at this)—men and women have almost entirely overlapping and fully Earth-bound abilities.

Recommended Videos

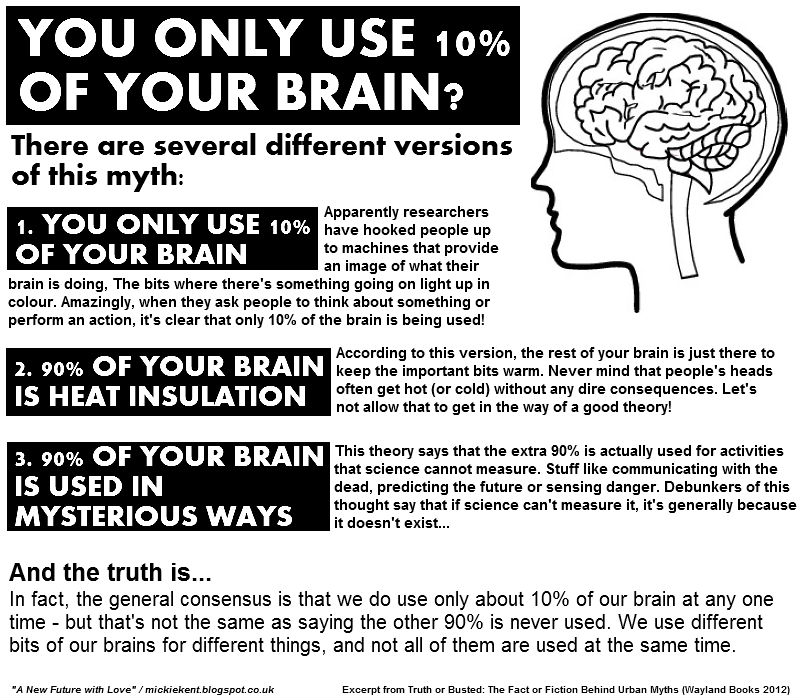

Neuroscience For Kids - 10% of the Brain Myth

Let me state this very clearly:

There is no scientific evidence to suggest that we use only 10% of our brains.

Let's look at the possible origins of this "10% brain use" statement and the evidence that we use all of our brain.

Where Did the 10% Myth Begin?

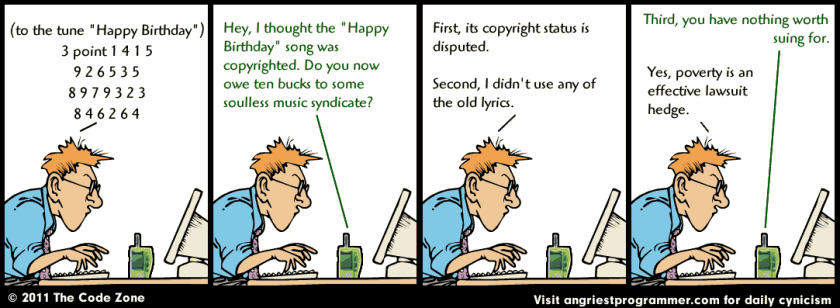

The 10% statement may have been started with a misquote of Albert Einstein or the misinterpretation of the work of Pierre Flourens in the 1800s. It may have been William James who wrote in 1908: "We are making use of only a small part of our possible mental and physical resources" (from The Energies of Men, p. 12). Perhaps it was the work of Karl Lashley in the 1920s and 1930s that started it. Lashley removed large areas of the cerebral cortex in rats and found that these animals could still relearn specific tasks. We now know that destruction of even small areas of the human brain can have devastating effects on behavior. That is one reason why neurosurgeons must carefully map the brain before removing brain tissue during operations for epilepsy or brain tumors: they want to make sure that essential areas of the brain are not damaged.

That is one reason why neurosurgeons must carefully map the brain before removing brain tissue during operations for epilepsy or brain tumors: they want to make sure that essential areas of the brain are not damaged.

| Advertisement for satellite TV. Text of the ad reads: "You only use 11% of its potential. Ditto. Now there's a way to get the most of both." --------------- Advertisement for Hard Disk --------------- Advertisement for an Airline Text of the ad reads: "It's been said that we use a mere 10% of our brain capacity. If, however, you're flying **** from **** Airlines, you're using considerably more." | Why Does the Myth Continue?Somehow, somewhere, someone started this myth and the popular media keep on repeating this false statement (see the figures). Soon, everyone believes the statement regardless of the evidence. I have not been able to track down the exact source of this myth, and I have never seen any scientific data to support it. What Does it Mean to Use Only 10% of Your Brain?What data were used to come up with the number - 10%? Does this mean that you would be just fine if 90% of your brain was removed? If the average human brain weighs 1,400 grams (about 3 lb) and 90% of it was removed, that would leave 140 grams (about 0.3 lb) of brain tissue. That's about the size of a sheep's brain. It is well known that damage to a relatively small area of the brain, such as that caused by a stroke, may cause devastating disabilities. Certain neurological disorders, such as Parkinson's Disease, also affect only specific areas of the brain. The damage caused by these conditions is far less than damage to 90% of the brain.

|

The Evidence (or lack of it)

Perhaps when people use the 10% brain statement, they mean that only one out of every ten nerve cells is essential or used at any one time? How would such a measurement be made? Even if neurons are not firing action potentials, they may still be receiving signals from other neurons.

Furthermore, from an evolutionary point of view, it is unlikely that larger brains would have developed if there was not an advantage. Certainly there are several pathways that serve similar functions. For example, there are several central pathways that are used for vision. This concept is called "redundancy" and is found throughout the nervous system. Multiple pathways for the same function may be a type of safety mechanism should one of the pathways fail. Still, functional brain imaging studies show that all parts of the brain function. Even during sleep, the brain is active. The brain is still being "used," it is just in a different active state.

Finally, the saying "Use it or Lose It" seems to apply to the nervous system. During development many new synapses are formed. In fact, some synapses are eliminated later on in development. This period of synaptic development and elimination goes on to "fine tune" the wiring of the nervous system. Many studies have shown that if the input to a particular neural system is eliminated, then neurons in this system will not function properly. This has been shown quite dramatically in the visual system: complete loss of vision will occur if visual information is prevented from stimulating the eyes (and brain) early in development. It seems reasonable to suggest that if 90% of the brain was not used, then many neural pathways would degenerate. However, this does not seem to be the case. On the other hand, the brains of young children are quite adaptable. The function of a damaged brain area in a young brain can be taken over by remaining brain tissue. There are incredible examples of such recovery in young children who have had large portions of their brains removed to control seizures. Such miraculous recovery after extensive brain surgery is very unusual in adults.

Such miraculous recovery after extensive brain surgery is very unusual in adults.

So next time you hear someone say that they only use 10% of their brain, you can set them straight. Tell them:

"We use 100% of our brains."

Several people have mentioned that the movie Lucy (2014) promotes the 10% of the brain myth. If you find any news articles or advertisements using the 10% myth, please send them to me: Dr. Eric H. Chudler.

For a continuing discussion of this topic, please see:

- Ten Percent and Counting - BrainConnection.com

- The Ten-Percent Myth from the Skeptical Inquirer

- The Ten-Percent Myth

- Do People Use 10 Percent of Their Brains? - Scientific American

- The Life and Times of the 10% Neuromyth

- Humans use 100 percent of their brains--despite the popular myth - Ask a Scientist

- Higbee, K.L. and Clay, S.L., College students' beliefs in the ten-percent myth, Journal of Psychology, 132:469-476, 1998.

- B.L. Beyerstein, Whence Cometh the Myth that We Only Use 10% of Our Brains? in Mind Myths. Exploring Popular Assumptions about the Mind and Brain edited by S. Della Sala, Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, pages 3-24, 1999. This chapter is required reading for anyone who wants more information on the 10% myth.

| Did you know? | Dr. James W. Kalat, author of the textbook Biological Psychology, has another idea for the origin of the 10% myth. Dr. Kalat points out that neuroscientists in the 1930s knew about the existence of the large number of "local" neurons in the brain, but the only thing they knew about these cells is that they were small. The misunderstanding of the function of local neurons may have led to the 10% myth. (Reference: Kalat, J.W., Biological Psychology, sixth edition, Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cole Publishing Co., 1998, p. 43.) |

| They said it! | "Myths which are believed in tend to become true. .." .."--- George Orwell (in The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell, vol. 3, edited by Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968, page 6.) "In fact, most of us use only about 10 percent of our brains, if that." --- Uri Geller (in Uri Geller's Mindpower Kit, New York: Penguin Books, 1996.) |

Copyright © 1996-2020, Eric H. Chudler All Rights Reserved.

9 myths about the human brain that you believe in absolutely nothing

April 9 Education

It's time to learn the truth about what color the contents of our skull are and how alcohol actually affects them.

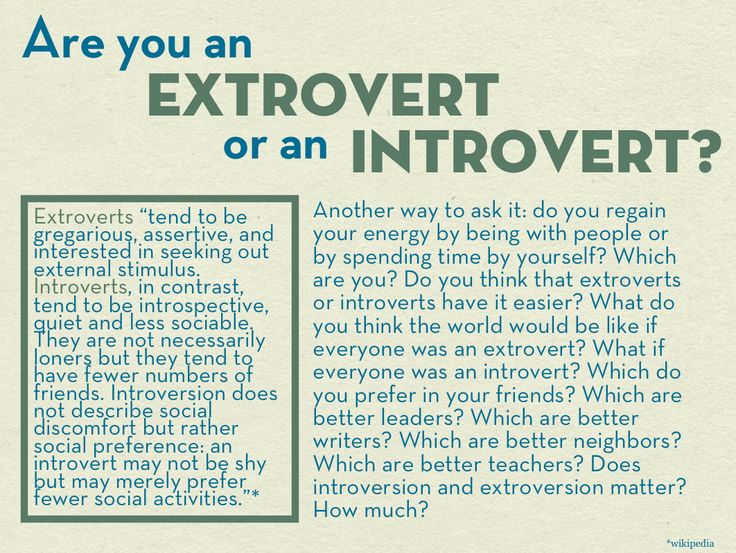

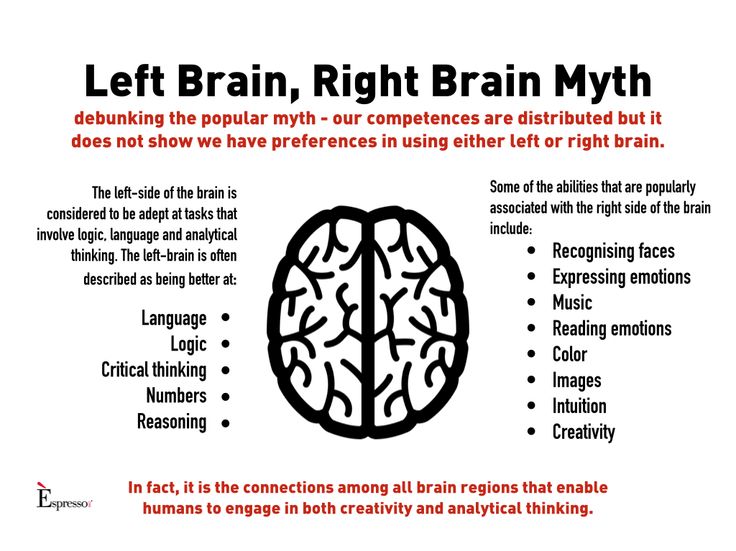

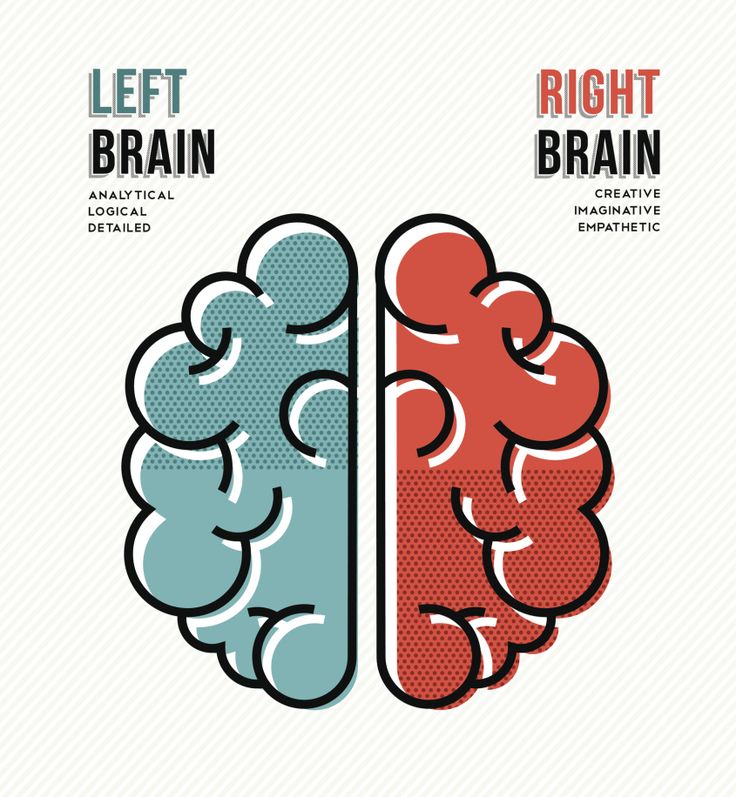

Myth 1. There is a right brain and a left brain

Image: Robina Weermeijer / UnsplashLet's start with one of the most common myths. Many people refer to themselves as "left brain" or "right brain". It's about like "techies" and "humanities", only it sounds more scientific.

It is believed that the left hemisphere is responsible for logic and rationality, and the right - for creative thinking. And in general, there is a reasonable basis for this assertion.

And in general, there is a reasonable basis for this assertion.

There is such a thing as lateralization of the functions of the brain, when its left and right halves take on different mental functions.

However, calling creative people "right hemisphere" and analysts "left hemisphere" is wrong, because each person's brain lateralization is unique. It develops differently for everyone, and the left side is quite capable of thinking creatively, while the right side is analytical.

Moreover, the fact that one half of the brain is loaded more than the other does not mean that the rest is idle. They work in tandem. For example, in most people, the left hemisphere processes the content of speech, while the right hemisphere takes into account intonation, stress, and emotional coloring of speech.

Both hemispheres work together to solve common problems, exchanging data through an area called the corpus callosum

The myth of right and left hemisphere people appeared when the neuroscientist Roger Sperry at 1981 investigated the connection of the halves of this organ in order to find a cure for epilepsy. His experiments showed that the left side is related to language, and the right side is related to the processing of spatial information. Journalists have taken Sperry's cautious assumptions and blown them up into a "brain dichotomy" theory.

His experiments showed that the left side is related to language, and the right side is related to the processing of spatial information. Journalists have taken Sperry's cautious assumptions and blown them up into a "brain dichotomy" theory.

Myth 2: Migraines hurt the brain

Image: Matteo Vistocco / UnsplashSome people explain migraines as a headache. They argue something like this: the skull consists of bone, there is nothing to hurt there, which means that it is the substance in the skull that suffers. However, this is a myth.

In fact, the brain is devoid of pain neurons, or nociceptors that transmit pain signals.

Therefore, by the way, surgeons can operate on this organ even when the patient is conscious.

In fact, a person experiences pain when pain receptors are irritated in the membranes of the brain and vessels next to it in the head, neck and spinal nerves, as well as in the periosteum (this is the connective tissue that covers the bones). So it is wrong to assume that migraines directly hurt the brain.

So it is wrong to assume that migraines directly hurt the brain.

Myth 3. The brain is gray

Image: Robina Weermeijer / UnsplashWe tend to think of the human brain as gray. This is a fairly popular misconception, which appeared, most likely, due to the signature phrase of the famous character - detective Hercule Poirot: "The gray cells did a good job!".

In addition, formalin-dissected brains may also appear colorless and sometimes yellowish.

In fact, the substance of the living tissues of this organ has a gray-brown color due to the capillaries with blood penetrating it. It also contains white fragments, as well as the so-called black substance, which is colored dark by the pigment neuromelanin. In addition, there are many red hues in the brain due to blood vessels. So actually the brain is far from pure gray.

Myth 4: After a certain age, the brain stops developing

Image: bruce mars / Unsplash Some people believe that when a person turns 40, 50, 60 - or whatever number you want - the brain stops making new cells. Accordingly, the learning ability of a person drops to zero.

Accordingly, the learning ability of a person drops to zero.

“I don’t have the same brain anymore!” - Elderly relatives joke when they are trying to teach them how to use a computer.

But this is another delusion. The human brain continues to develop throughout life, and in older people, neurogenesis, that is, the formation of new neuron cells, occurs at about the same rate as in young people.

True, with age, some of the receptors on the surface of neurons may not work as well as before, and therefore, memorization and concentration games are somewhat more difficult for older people. But the cells do not die off with age - this is a bike.

In addition, in older people, the branching of nerve processes, dendrites increases, and connections between distant areas of the brain increase. This allows you to better build logical connections. In addition, emotional control improves with age. And physical (mostly aerobic) and mental exercises allow older people to keep their brains working.

Therefore, it is absolutely wrong to say that with age people are expected to become stupid. This can be avoided if you lead a healthy lifestyle and constantly load the brain, not letting it idle.

So if your relatives refuse to learn how to use a smartphone - this is laziness, and not a natural state of the body.

Myth 5. We only use 10% of our brains

A still from the movie LucyAnother popular and long-lived myth that has been floating around in the media since at least 1998 is that people only use 10% of their brain resources. Sometimes they also talk about 5%.

But if you unlock the potential of the brain by 100%, you can become smarter than Einstein, and even start moving objects with the power of thought, like Scarlett Johansson in the movie "Lucy".

True, it is not clear why the remaining 90% is needed.

Considering that this organ absorbs more than half of the glucose in the body, even in sedentary people, it would be extremely wasteful to feed the brain when it is mostly idle. This is the most energy-consuming part of the body.

This is the most energy-consuming part of the body.

In addition, if only 10% of the brain were needed for life, damage to this organ would be much less lethal.

The whole brain actually works. And even the simplest tasks like walking and talking involve the body completely. Some parts of it may be more active than others, but there are no areas that are idle.

The 10% myth most likely originated from the work of the psychologist and philosopher William James. In his 1908 book The Energies of Men, he wrote: "We use only a small part of our mental and physical resources." And all sorts of motivational speakers and coaches picked up this slogan, took the figure of 10% from the ceiling and replicated it in the media.

Myth 6. Humans have a "reptilian" part of the brain

Image: Alex Williams / Unsplash.comYou may have heard the expression "reptilian brain". This is supposedly the oldest part that we inherited from reptiles.

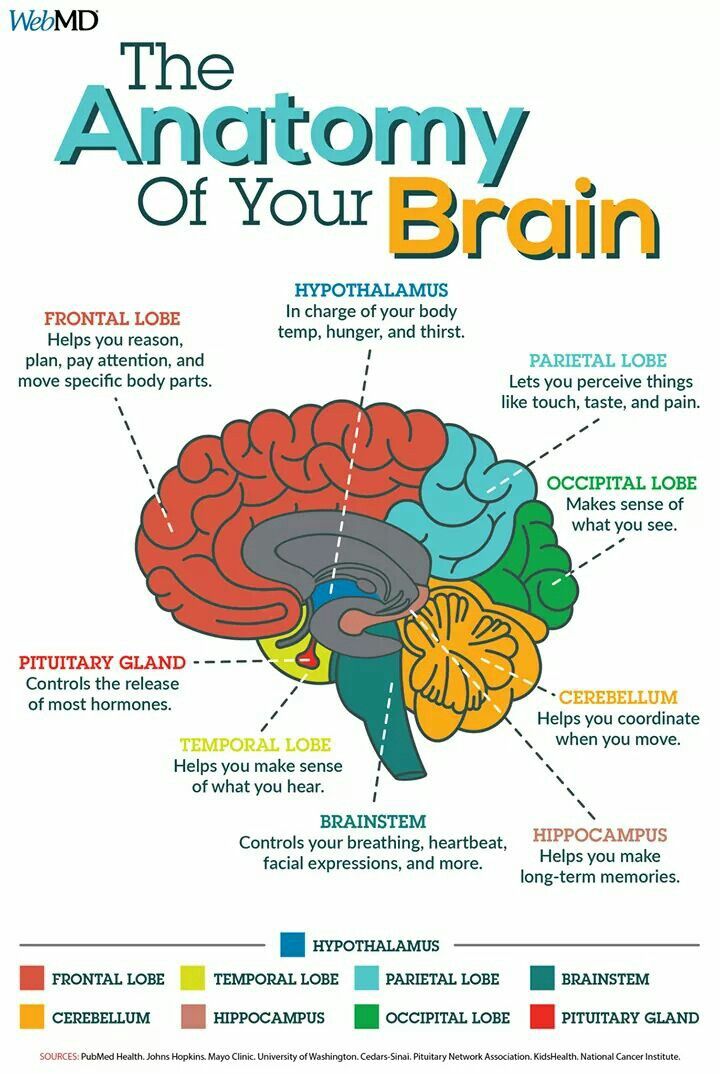

She is responsible for biological survival, reproduction, the functioning of the body, protection of the territory, the desire to control everything and dominate the hierarchy. Reptiles are called the back and central parts of the brain, as well as the brain stem and cerebellum.

Reptiles are called the back and central parts of the brain, as well as the brain stem and cerebellum.

It is in them, in theory, that the most aggressive, primitive and animal desires and instincts are born.

According to the "triune brain" theory, developed by the American physician and neuroscientist Paul D. McLean, more advanced parts of the limbic system grew over the primitive "reptilian" areas of the brain in the first mammals. She is responsible for feelings and emotions.

And the most developed mammals, primates, have a neocortex - a region of the cortex responsible for memory and thinking. She supposedly helps control animal urges and keep her "reptilian nature" in check. In primitive mammals, the neocortex is only outlined, while in humans it makes up 76% of the brain volume.

The "reptilian brain" theory was popular until the early 1970s, but then scientists criticized it and recognized it as a myth.

According to modern research, the brain develops as a whole, and not in "layers", as MacLean imagined. The so-called "reptile", or, as it is more correct to say, its basal part has undergone a huge number of evolutionary changes.

The so-called "reptile", or, as it is more correct to say, its basal part has undergone a huge number of evolutionary changes.

The cerebellum of primates is incomparably better developed than the brain of reptiles. And yes, it is now known that humans are not descended from reptiles, as was believed in the 60s. Our evolutionary branches diverged much earlier, about 320 million years ago, in the Carboniferous.

Myth 7. When the brain is separated from the body, it remains conscious for several minutes

Image: Wikimedia CommonsThere is a popular myth that when Queen Anne Boleyn was executed in 1536, her lips continued to move after being beheaded, as if she was trying something to tell.

A similar incident allegedly occurred during the French Revolution, when the guillotine was invented. On July 17, 1793, a woman named Charlotte Corday was executed with this infernal device for the murder of the radical journalist Jean Paul Marat.

After the beheading, the executioner (according to another version, the carpenter who put the guillotine) raised the girl's head and slapped her. Her face was supposedly flushed and contorted with anger.

Her face was supposedly flushed and contorted with anger.

However, modern neurophysiology claims that these cases are greatly exaggerated.

Some insects, such as cockroaches, can live without a head for a while and starve to death. And snakes, turtles, chickens and some other animals are able to temporarily continue to move after decapitation. But in humans, the nervous system is much more complicated and will not work without the control of the brain.

Reactions such as blinking and twitching of the lips on the severed head are reflex muscle twitches, not conscious actions. Separation of the brain from the spinal cord and from the circulatory system after 2-3 seconds causes a coma, and then death. So heads trying to transmit signals with their eyes or say something are fiction.

Myth 8. Classical music helps the brain develop

Image: Josh Hild / Unsplash There is a popular misconception that regular listening to Mozart, Bach and Beethoven has a beneficial effect on the mental and physical state of the body, no matter what species it belongs to.

Classical music makes children become geniuses, adults increase their working capacity, and in general, neural connections in the brain become stronger and IQ grows. And also under Paganini, the beets begin to sprout and cows' milk yields increase.

But those who listen to hard rock will begin to die brain cells. Metalheads, tremble!

This is a myth that appeared in the 90s due to research by scientists at the University of California at Irvine. They gave students to listen to music of different genres, and then they conducted IQ tests. And those who enjoyed Mozart scored an average of 8 points more.

Baby Einstein, a manufacturer of educational DVDs for toddlers, jumped at the idea and started churning out classical music CDs. And parents who want to raise geeks from offspring began to buy them in tons.

Some even began to listen to classical music during pregnancy, because it supposedly had a good effect on the developing fetus. As a result, thanks to the Baby Einstein advertising campaign, the so-called “Mozart Effect” appeared in the mass consciousness.

As a result, thanks to the Baby Einstein advertising campaign, the so-called “Mozart Effect” appeared in the mass consciousness.

However, there is no real evidence that listening to classical music develops the brain. Subsequent studies have not recorded any effect of music on intellectual abilities. So you can listen to any genre you like and don't force your ears with the classics if you don't like them.

Myth 9. Alcohol kills brain cells

Image: Gerrie van der Walt / UnsplashHealth fans often claim that alcohol kills brain cells, causing the head organ to shrink. Some particularly impressionable individuals even add that dead cells "leak out with urine."

It's not uncommon to find quotes on the Internet that say, "Three pints of beer kill 10,000 brain cells."

But in fact it is not so. Ethyl alcohol can destroy living cells on direct contact, making it an antiseptic. But you just can't drink enough ethanol to sterilize your brain—banal poisoning will knock you off your feet sooner.

Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis found that alcohol does not kill neurons, even when injected directly into them. It only blocks the communication between them, preventing the transfer of information, which makes drunks clumsy. But if you do not drink for a while, this effect disappears and connections are restored.

Therefore, it is wrong to say that alcohol kills brain cells. However, drinking is bad for vascular health, which increases the risk of stroke. In addition, large doses of alcohol also interfere with neurogenesis, that is, the formation of new brain cells. Heavy drinking can literally make you dumb.

Read also 🧐

- 10 non-obvious facts about human nature

- 10 facts about the human body that seem fantastic

- 7 misconceptions of doctors of the past about the human body and health

“We use only 10% of the brain” and 5 more myths about our main organ

One of the first myths about the brain appeared more than four thousand years ago: then it was believed that the brain, unlike the heart, it does not participate in the formation of thoughts and emotions. And although no one now believes in thoughts of the heart, many myths about the brain still live on. We refute the most common of them.

And although no one now believes in thoughts of the heart, many myths about the brain still live on. We refute the most common of them.

😱 Nerve cells do not regenerate

In fact, the process of formation of new nerve cells - neurogenesis - continues throughout life. This was proved in 1988 by Swedish neuroscientists.

They examined the post-mortem brain tissue of people who agreed to take bromodeoxyuridine during their lifetime. This is a substance that is incorporated into the DNA of new cells. At autopsy, bromodeoxyuridine molecules were found in the hippocampus of volunteers. Therefore, these cells appeared after they started taking the substance.

Neurogenesis can be influenced by comfortable living conditions, positive emotions and physical activity. And depression, alcohol and excess weight can interfere with it

🌎 The left hemisphere of the brain is responsible for logic, the right - for creativity

One of the most important studies on this topic was conducted in 2012 by scientists from the University of Utah. They studied the results of MRI of the brain of more than a thousand people and refuted the theory of the dominance of the right or left hemisphere, depending on the field of activity. It turned out that both mathematicians and artists equally use both hemispheres.

They studied the results of MRI of the brain of more than a thousand people and refuted the theory of the dominance of the right or left hemisphere, depending on the field of activity. It turned out that both mathematicians and artists equally use both hemispheres.

But there is a sound grain in this fiction: certain parts of the left hemisphere are involved in speech activity and performing mathematical tasks, and in the right hemisphere there are more areas responsible for attention

🧮 We use only 10% of the brain

This myth is over a hundred years old, and thanks to books, movies and memes, it remains one of the most common. In fact, we use the entire brain as a whole, we just use different parts of it for different tasks, just like we need different muscle groups for different movements.

In addition, the brain constantly monitors unconscious processes such as heartbeat and breathing. Scientists have not found any evidence that some parts of a healthy brain may not work at all

neurons.

London taxi drivers taking part in the experiment memorized information about the city, and scientists tracked whether the brain changes. It turned out that the more new knowledge the subject learned, the larger his hippocampus became.

London taxi drivers taking part in the experiment memorized information about the city, and scientists tracked whether the brain changes. It turned out that the more new knowledge the subject learned, the larger his hippocampus became. In another experiment, adult participants had to learn foreign languages. As it turned out, they are quite capable of reaching almost the level of the host and keeping it for a long time

👫 Male and female brains work differently

any other organ in the human body, be it the liver or the kidneys.

There may be anatomical differences between male and female brains due to body size, but they do not affect mental and creative abilities. For their formation, experience, interests, profession, lifestyle and even physical activity are much more important

⚖️ The larger the brain, the smarter the person

There is a possibility that this is not entirely a delusion: there is a slight connection between intelligence and brain size.

According to the believers of this myth, if we used more of our brain, then we could perform super memory feats and have other fantastic mental abilities - maybe we could even move objects with a single thought. Again, I do not know of any data that would support any of this.

According to the believers of this myth, if we used more of our brain, then we could perform super memory feats and have other fantastic mental abilities - maybe we could even move objects with a single thought. Again, I do not know of any data that would support any of this.