Mental disorder that causes anger

Intermittent Explosive Disorder: Symptoms & Treatment

Overview

What is intermittent explosive disorder?

Intermittent explosive disorder (IED) is a mental health condition marked by frequent impulsive anger outbursts or aggression. The episodes are out of proportion to the situation that triggered them and cause significant distress.

People with intermittent explosive disorder have a low tolerance for frustration and adversity. Outside of the anger outbursts, they have normal, appropriate behavior. The episodes could be temper tantrums, verbal arguments or physical fights or aggression.

Intermittent explosive disorder is one of several impulse control disorders.

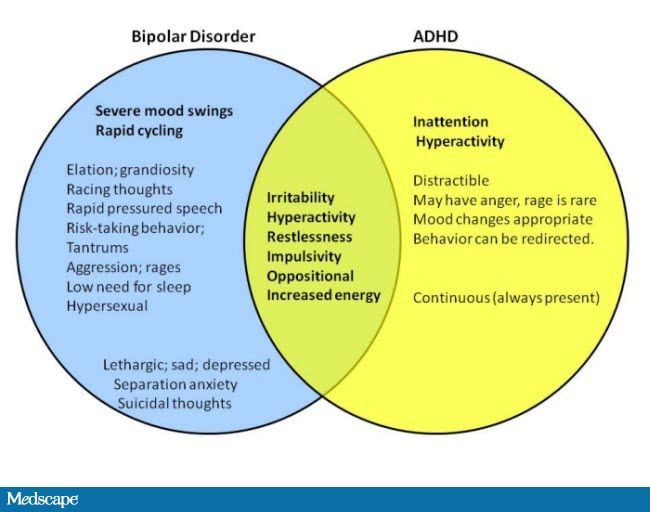

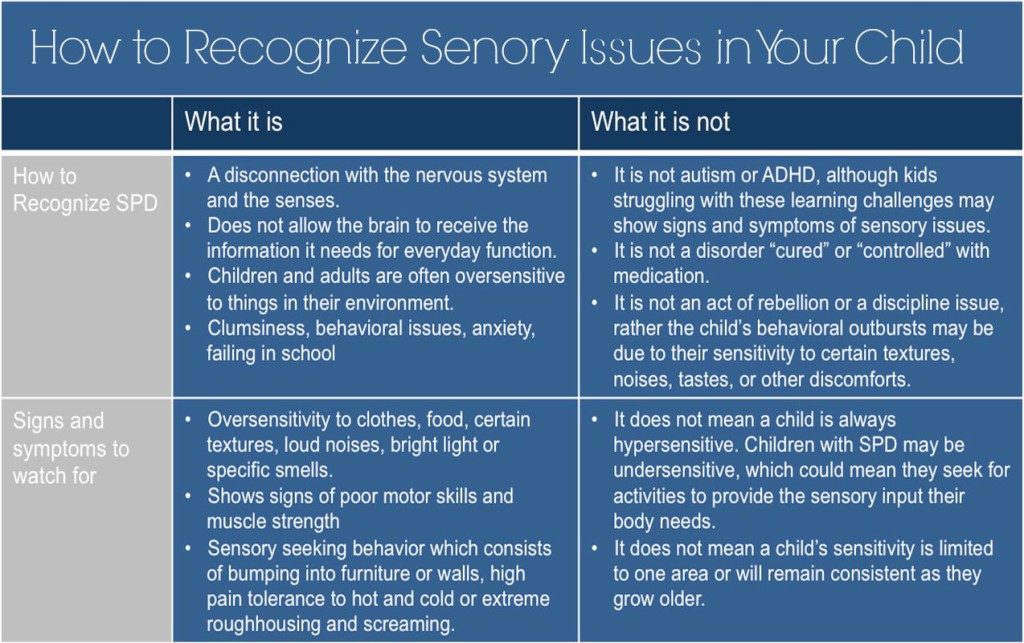

Approximately 80% of people with IED have another mental health condition, with anxiety disorders, externalizing disorder, intellectual disabilities, autism and bipolar disorder being the most common.

Who does intermittent explosive disorder affect?

Intermittent explosive disorder (IED) can affect children aged 6 years and older and adults. Adults diagnosed with IED are usually younger than 40 years old.

IED more commonly affects people assigned male at birth (AMAB) than people assigned female at birth (AFAB).

How common is intermittent explosive disorder?

Researchers estimate that approximately 1.4% to 7% of people have intermittent explosive disorder.

Symptoms and Causes

What are the signs and symptoms of intermittent explosive disorder?

The main sign of intermittent explosive disorder is a pattern of outbursts of anger that are out of proportion to the situation or event that caused them. People with IED are aware that their anger outbursts are inappropriate but feel like they can’t control their actions during the episodes.

The aggressive outbursts:

- Are impulsive (not planned).

- Happen rapidly after being provoked.

- Last no longer than 30 minutes.

- Cause significant distress.

- Cause problems at school, work and/or home.

Examples of how the anger manifests include:

- Temper tantrums.

- Verbal arguments, which may include shouting and/or threatening others.

- Physically assaulting people or animals, such as shoving, slapping, punching or using a weapon to cause harm.

- Property/object damage, such as throwing, kicking or breaking objects and slamming doors.

- Domestic violence.

- Road rage.

The anger episodes can be mild or severe. They may involve hurting someone badly enough to require medical attention or even cause death.

If you have IED, right before an anger outburst, you may experience:

- Rage.

- Irritability.

- An increasing sense of tension.

- Racing thoughts.

- Poor communication.

- Increased energy.

- Tremors.

- Heart palpitations.

- Chest tightness.

After an outburst, you may feel a sense of relief, followed by regret and embarrassment.

What causes intermittent explosive disorder?

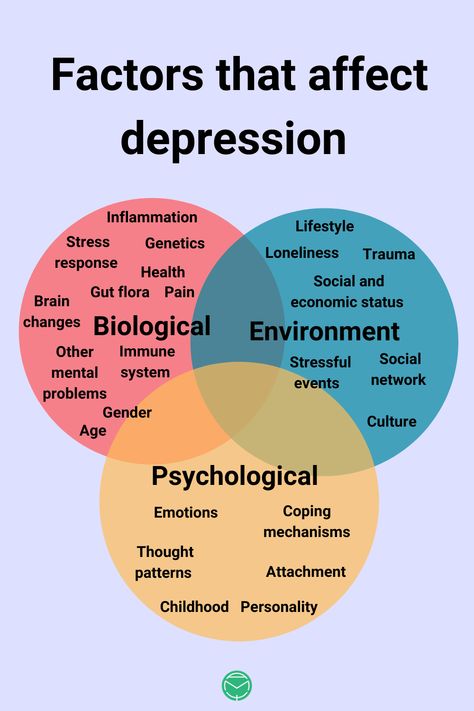

Researchers are still trying to discover the exact cause of intermittent explosive disorder, but they think genetic, biological and environmental factors contribute to its development:

- Genetic factors: IED more commonly runs in biological families.

Studies suggest that 44% to 72% of the likelihood of developing impulsive aggressive behavior is genetic.

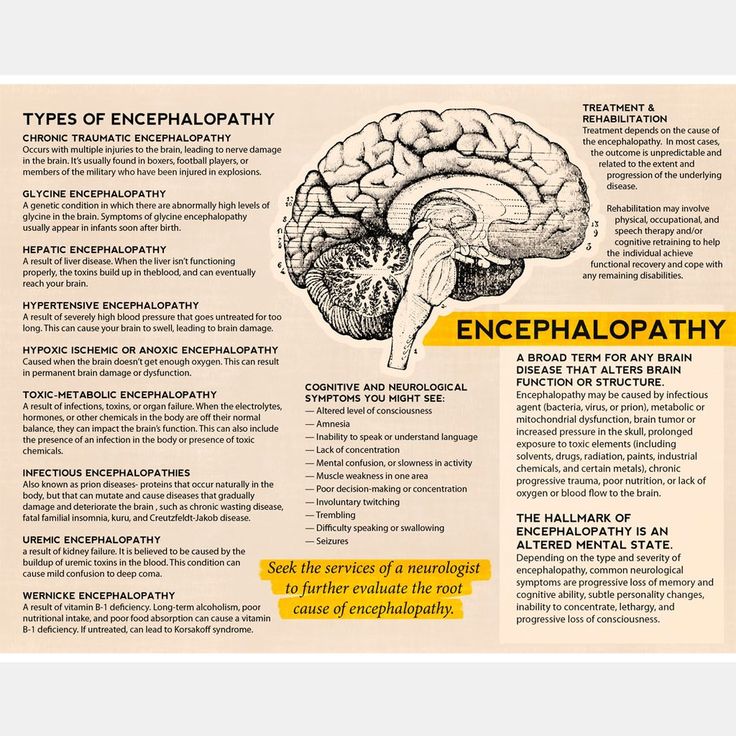

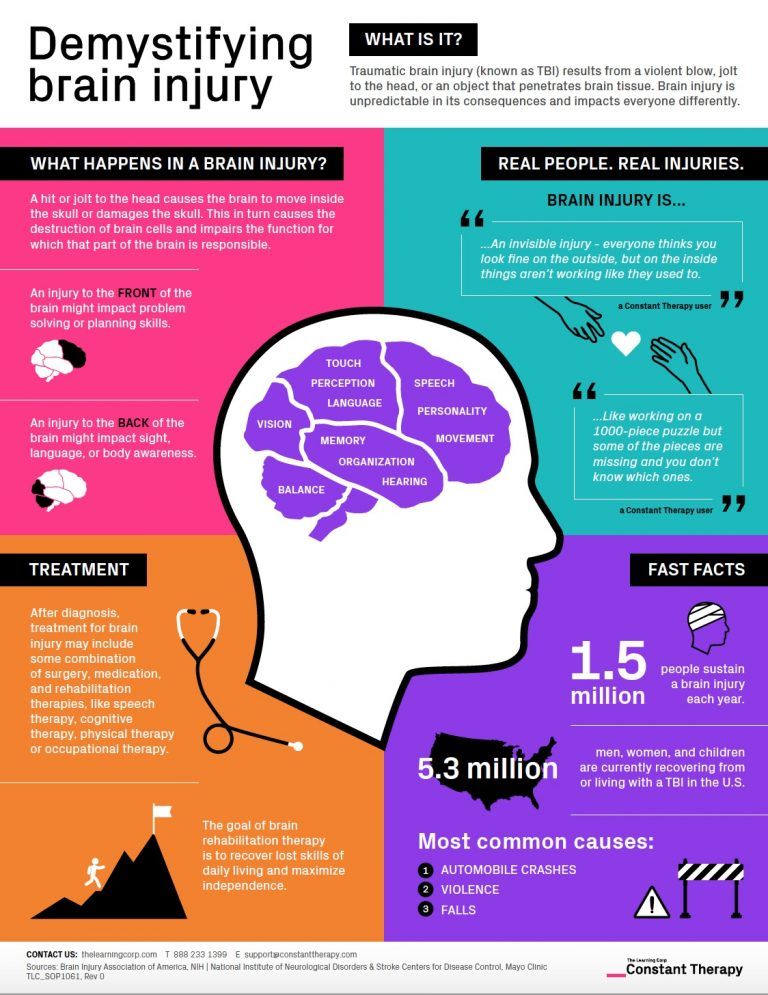

Studies suggest that 44% to 72% of the likelihood of developing impulsive aggressive behavior is genetic. - Biological factors: Studies show that brain structure and function are altered in IED. For example, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies suggest that it affects the amygdala, which is the part of your brain involved in emotional functioning. In addition, studies show that the level of serotonin (a neurotransmitter and hormone) is lower than normal in people with IED.

- Environmental factors: Experiencing verbal and physical abuse in childhood and/or witnessing abuse during childhood appears to play a role in the development of IED. Having experienced one or more traumatic events in childhood also seems to play a role.

Diagnosis and Tests

How is intermittent explosive disorder diagnosed?

If you think you or your child may have intermittent explosive disorder, it’s important to talk to your healthcare provider. They’ll likely refer you to a mental health professional who’s experienced in diagnosing IED.

They’ll likely refer you to a mental health professional who’s experienced in diagnosing IED.

A licensed mental health professional — such as a psychiatrist, psychologist or clinical social worker — can diagnose IED based on the diagnostic criteria for it in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

They do so by performing a thorough interview and having conversations about symptoms. They ask questions that’ll shed light on:

- Personal medical history and biological family medical history, especially histories of mental health conditions.

- Relationship history.

- School or work history.

- Impulse control.

Your mental health professional may also work with your family and friends to collect more insight into your behaviors and history.

To receive an intermittent explosive disorder diagnosis, you must display a failure to control aggressive impulses as defined by either of the following:

-

High frequency/low intensity episodes: Verbal aggression (temper tantrums, verbal arguments or fights) or physical aggression toward property, animals or people, occurring twice weekly, on average, for three months.

The aggression doesn’t result in physical harm to people or animals or the destruction of property.

The aggression doesn’t result in physical harm to people or animals or the destruction of property. - Low frequency/high intensity episodes: Three episodes involving damage or destruction of property and/or physical assault involving physical injury against animals or other people occurring within a 12-month period.

The degree of aggression displayed during the outbursts must be greatly out of proportion to the situation. In addition, the outbursts aren’t pre-planned. They’re impulse- and/or anger-based. Your mental health professional will also make sure that the outbursts aren’t better explained by another mental health condition, medical condition or substance use disorder.

People must be at least 6 years old to get an IED diagnosis, but it’s usually first observed in late childhood or adolescence.

Management and Treatment

How is intermittent explosive disorder treated?

Treatment for intermittent explosive disorder typically involves psychotherapy (talk therapy) focused on changing thoughts related to anger and aggression. Treatment may also include medication, depending on your age and symptoms.

Treatment may also include medication, depending on your age and symptoms.

The goal of treatment for IED is remission, which means that your symptoms (anger outbursts) go away or you experience improvement to the point that only one or two symptoms of mild intensity persist. For people who don’t achieve remission, a reasonable goal is stabilizing the safety of the person and others, as well as a substantial improvement in the number, intensity and frequency of anger outbursts.

Psychotherapy for IED

Psychotherapy (talk therapy) is usually the main treatment for intermittent explosive disorder, especially cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

CBT is a structured, goal-oriented type of therapy. A therapist or psychologist helps you take a close look at your thoughts and emotions. You’ll come to understand how your thoughts affect your actions. Through CBT, you can unlearn negative thoughts and behaviors and learn to adopt healthier thinking patterns and habits.

CBT teaches people with IED how to manage negative situations in day-to-day life and may thus prevent aggressive impulses that can trigger explosive outbursts.

Specific techniques mental health professionals use in CBT for intermittent explosive disorder include:

- Cognitive restructuring: This involves changing faulty assumptions and unhelpful thoughts about frustrating situations and perceived threats.

- Relaxation training: Relaxing techniques like deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation (tensing and relaxing different muscle groups while imagining situations that provoke anger) can help minimize your response to triggering situations.

- Coping skills training: This involves role-playing situations that may cause an explosive episode and practicing healthy responses like walking away.

- Relapse prevention: This involves educating people with IED that recurrence of impulsive aggressive behavior is common and should be viewed as a lapse or “slip” rather than a failure.

Medications for IED

Certain medications may increase the threshold (level) at which a situation triggers an angry outburst for people with intermittent explosive disorder.

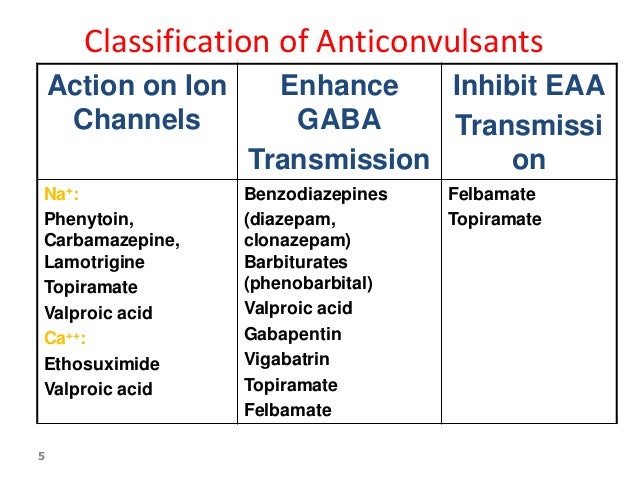

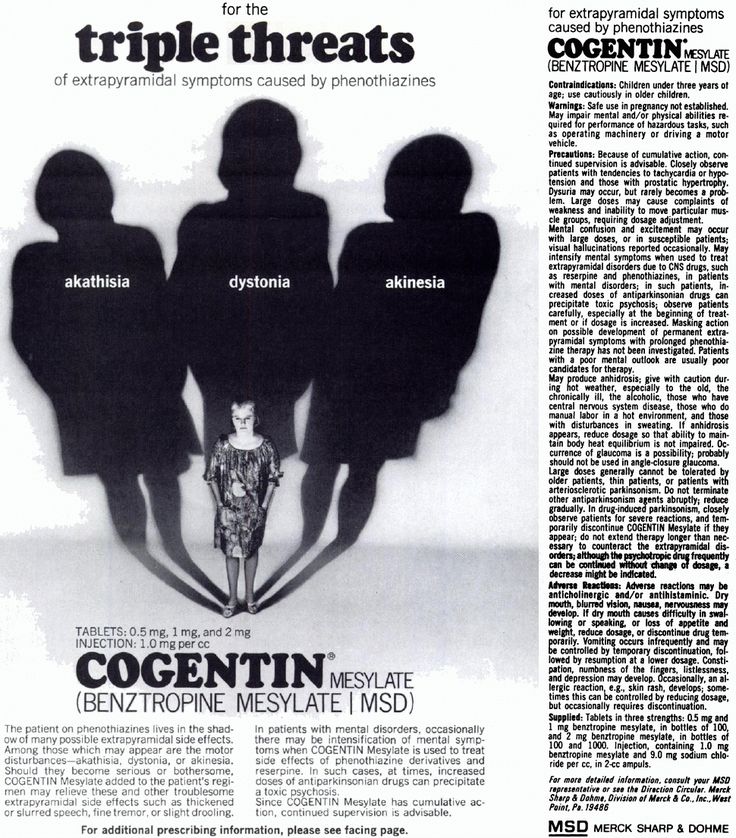

Fluoxetine (a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, or SSRI) is the most studied medication for treating intermittent explosive disorder. Other medications that have been studied for IED include phenytoin, lithium, oxcarbazepine and carbamazepine.

In general, healthcare providers typically prescribe the following classes of medications for IED:

- Antidepressants.

- Antipsychotics.

- Anticonvulsants.

- Antianxiety medications.

- Mood regulators.

Prevention

What are the risk factors for developing intermittent explosive disorder?

Risk factors for intermittent explosive disorder include:

- Being a young person AMAB.

- Being unemployed.

- Being single (unmarried).

- Having lower levels of education.

- Experiencing physical or sexual violence, especially as a child.

- Having biological family members with intermittent explosive disorder.

If you’re concerned about your child’s risk of developing intermittent explosive disorder, talk to your healthcare provider.

Outlook / Prognosis

What is the prognosis (outlook) for intermittent explosive disorder?

People with intermittent explosive disorder tend to have poor life satisfaction and lower quality of life. It can have a very negative impact on your health and can lead to severe personal and relationship problems.

Cognitive therapy and medication can successfully manage IED. However, according to studies, IED appears to be a long-term condition, lasting from 12 to 20 years or even a lifetime.

Having intermittent explosive disorder makes it more likely that you’ll develop the following conditions:

- Depression.

- Anxiety.

- Alcohol use disorder.

- Substance use disorder.

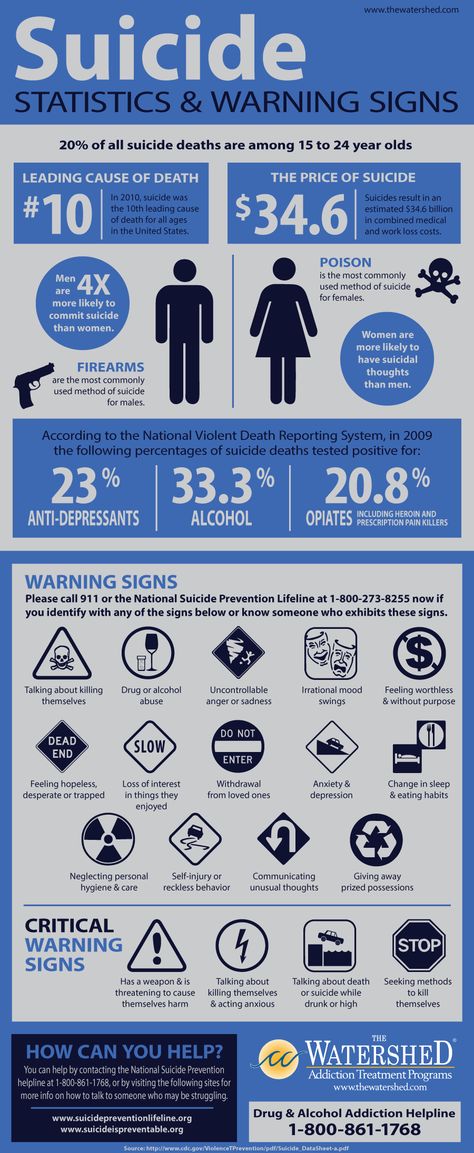

In addition, people with IED are at an increased risk for self-harm (self-injury) and suicide. Because of this, it’s essential to seek medical help as soon as possible if you feel you or a family member has intermittent explosive disorder.

Living With

How do I take care of myself if I have intermittent explosive disorder?

If you have intermittent explosive disorder, it’s essential to seek professional, medical treatment. You’ll learn a variety of coping techniques in therapy. These can help prevent anger episodes. They include:

You’ll learn a variety of coping techniques in therapy. These can help prevent anger episodes. They include:

- Relaxation techniques.

- Changing the ways you think (cognitive restructuring).

- Communication skills.

- Learning to change your environment and leaving stressful situations when possible.

It’s also very important to avoid alcohol and recreational drugs. These substances can increase the risk of violent behavior.

When should I see my healthcare provider for intermittent explosive disorder?

If you or your child has been diagnosed with intermittent explosive disorder, you’ll need to see your healthcare team regularly to make sure your treatment (talk therapy and/or medication) is working.

If you or your child displays behavior that harms or endangers others, such as other people or animals, it’s important to find immediate care.

People with intermittent explosive disorder who are thinking of harming themselves or attempting suicide need help right away.

If you or someone you know is in immediate distress or is thinking about hurting themselves, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline toll-free at 1.800.273.TALK (8255).

A note from Cleveland Clinic

It’s important to remember that intermittent explosive disorder (IED) is a mental health condition. As with all mental health conditions, seeking help as soon as symptoms appear can help decrease the disruptions to your life. Mental health professionals can offer treatment plans that can help you manage your thoughts and behaviors.

The family members and loved ones of people with IED often experience stress, depression and isolation. It’s important to take care of your mental health and seek help if you’re experiencing these symptoms. If you’re in a relationship with someone who has intermittent explosive disorder, take steps to protect yourself and your children.

Signs, Symptoms & Effects of IED

Understanding Intermittent Explosive Disorder

Learn About Intermittent Explosive Disorder

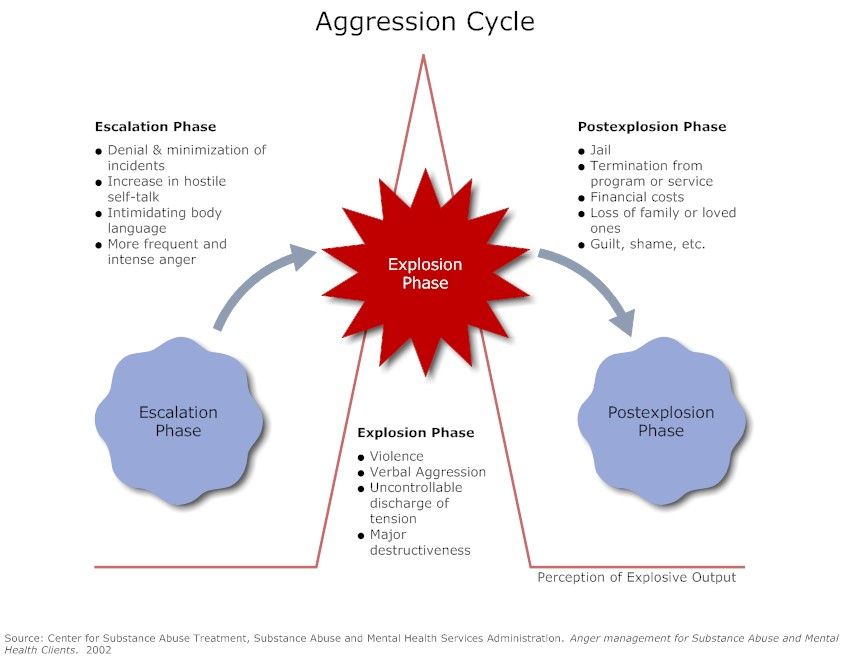

Intermittent explosive disorder (IED) is an impulse-control disorder characterized by sudden episodes of unwarranted anger. The disorder is typified by hostility, impulsivity, and recurrent aggressive outbursts. People with IED essentially “explode” into a rage despite a lack of apparent provocation or reason. Individuals suffering from intermittent explosive disorder have described feeling as though they lose control of their emotions and become overcome with anger. People with IED may threaten to or actually attack objects, animals, and/or other humans. IED is said to typically begin during the early teen years and evidence has suggested that it has the potential of predisposing individuals to depression, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders. Intermittent explosive disorder is not diagnosed unless a person has displayed at least three episodes of impulsive aggressiveness.

The disorder is typified by hostility, impulsivity, and recurrent aggressive outbursts. People with IED essentially “explode” into a rage despite a lack of apparent provocation or reason. Individuals suffering from intermittent explosive disorder have described feeling as though they lose control of their emotions and become overcome with anger. People with IED may threaten to or actually attack objects, animals, and/or other humans. IED is said to typically begin during the early teen years and evidence has suggested that it has the potential of predisposing individuals to depression, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders. Intermittent explosive disorder is not diagnosed unless a person has displayed at least three episodes of impulsive aggressiveness.

Individuals with IED have reported that once they have released the tension that built up as a result of their rage, they feel a sense of relief. Once the relief wears off, however, some people report experiencing feelings of remorse or embarrassment. While IED can be extremely disruptive to an individual’s life, as well as to the lives of those around him or her, IED can be managed through proper treatment, through education about anger management, and possibly through the use of medication.

While IED can be extremely disruptive to an individual’s life, as well as to the lives of those around him or her, IED can be managed through proper treatment, through education about anger management, and possibly through the use of medication.

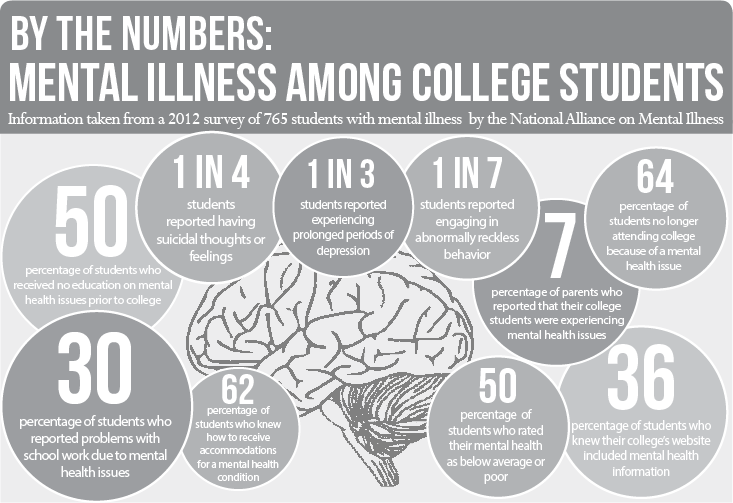

Statistics

Intermittent Explosive Disorder Statistics

Intermittent explosive disorder is said to affect around 7.3% of adults at some point throughout their lifetimes. This equates to around 11.5-16 million Americans. Of the individuals in the U.S. who were diagnosed with IED, 67.8% had engaged in direct aggression against another person(s), 20.9% had threatened aggression against another person(s), and 11.4% had engaged in direct aggression against objects.

Causes and Risk Factors

Causes and Risk Factors for Intermittent Explosive Disorder

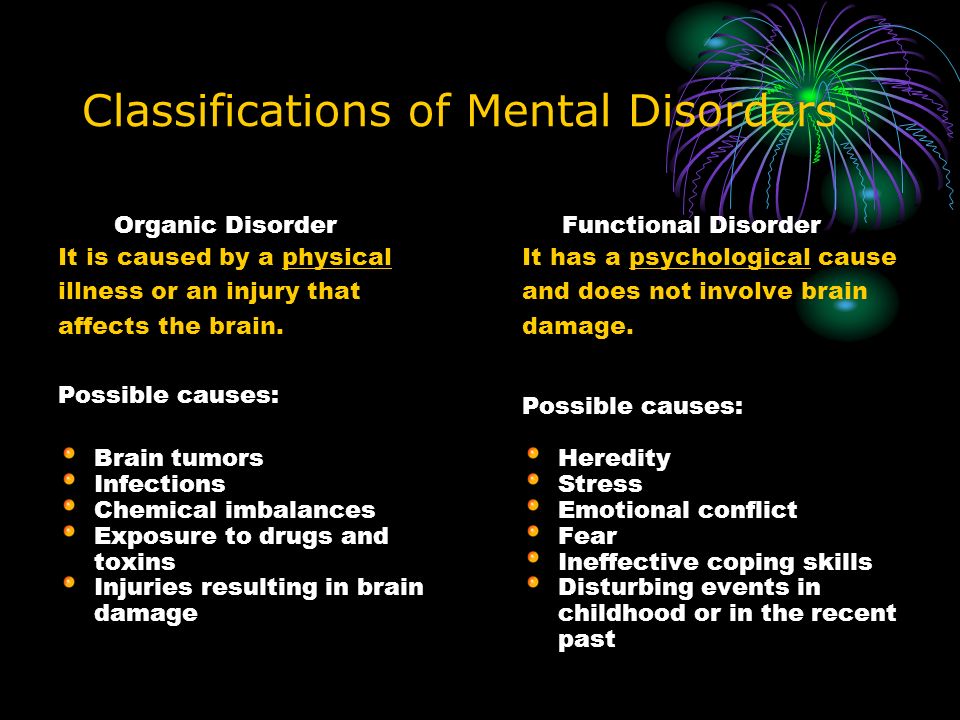

The cause of intermittent explosive disorder is said to be a combination of multiple components, including genetic factors, physical factors, and environmental factors. The following are some examples of these varying factors:

The following are some examples of these varying factors:

Genetic: It has been hypothesized that the traits that this disorder is composed of are passed down from parents to children; however, there is presently not any specific gene identified as having a prominent impact in the development of IED.

Physical: Research has suggested that intermittent explosive disorder may occur as the result of abnormalities in the areas of the brain that regulate arousal and inhibition. Impulsive aggression may be related to abnormal mechanisms in the part of the brain that inhibits or prohibits muscular activity through the neurotransmitter serotonin. Serotonin, which works to send chemical messages throughout the brain, may be composed differently in people with intermittent explosive disorder.

Environmental: The environment in which a person grows up can have a large impact on whether or not he or she develops symptoms of IED. It has been hypothesized that people who grow up in homes in which they were subjected to harsh punishments are more likely to develop IED. The belief is that these children will follow the example set by their parents and will act out aggressively – their initial reaction to something negative that they encounter. Another theory is that if children endured harsh physical punishments, they may find a sense of redemption in putting others through the same form of physical pain.

The belief is that these children will follow the example set by their parents and will act out aggressively – their initial reaction to something negative that they encounter. Another theory is that if children endured harsh physical punishments, they may find a sense of redemption in putting others through the same form of physical pain.

Risk Factors:

- Being male

- Exposure to violence at an early age

- Exposure to explosive behaviors at home (e.g. angry outbursts from parents or siblings)

- Having experienced physical trauma

- Having experienced emotional trauma

- History of substance abuse

- Certain medical conditions

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and Symptoms of Intermittent Explosive Disorder

There are a variety of symptoms that people who have intermittent explosive disorder will display based upon individual genetic makeup, development of social skills, coping strategies, presence of co-occurring disorders, and use or addiction to drugs or alcohol. The following are some examples of various signs and symptoms that a person suffering from IED may exhibit:

The following are some examples of various signs and symptoms that a person suffering from IED may exhibit:

Behavioral symptoms:

- Physical aggressiveness

- Verbal aggressiveness

- Angry outbursts

- Physically attacking people and/or objects

- Damaging property

- Road rage

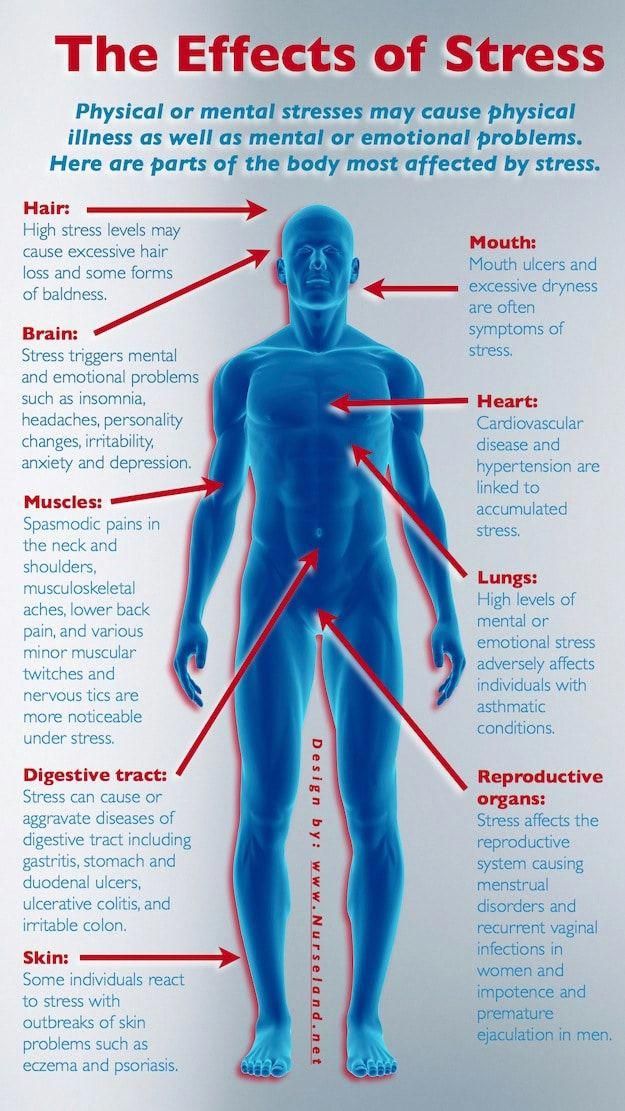

Physical symptoms:

- Headaches

- Muscle tension

- Chest tightness

- Palpitations

- Tingling

- Feelings of pressure in the head

- Tremors

Cognitive symptoms:

- Low frustration tolerance

- Feeling a loss of control over one’s thoughts

- Racing thoughts

Psychosocial symptoms:

- Feelings of rage

- Uncontrollable irritability

- Brief periods of emotional detachment

Effects

Effects of Intermittent Explosive Disorder

IED can lead to devastating consequences for those with the disorder, but this depends upon the specific symptoms and behaviors the person exhibits. The following are examples of effects that untreated intermittent explosive disorder can have on individuals:

The following are examples of effects that untreated intermittent explosive disorder can have on individuals:

- Impaired interpersonal relationships

- Domestic or child abuse

- Legal problems

- Incarceration

- Drug or alcohol addiction

- Trouble at work, home, or school

- Low self-esteem and self-loathing

- Self-harm

- Suicidal thoughts and behaviors

Co-Occurring Disorders

Intermittent Explosive Disorder and Co-Occurring Disorders

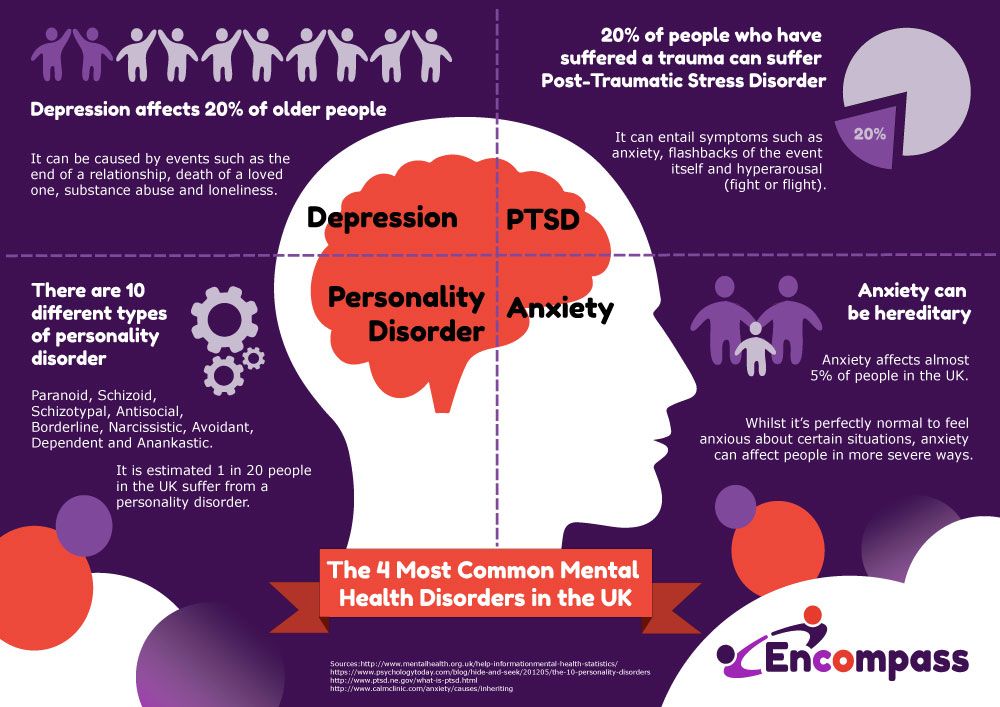

The symptoms of intermittent explosive disorder oftentimes directly mirror symptoms of various other disorders. Some of the most common mental disorders that co-occur with IED can include:

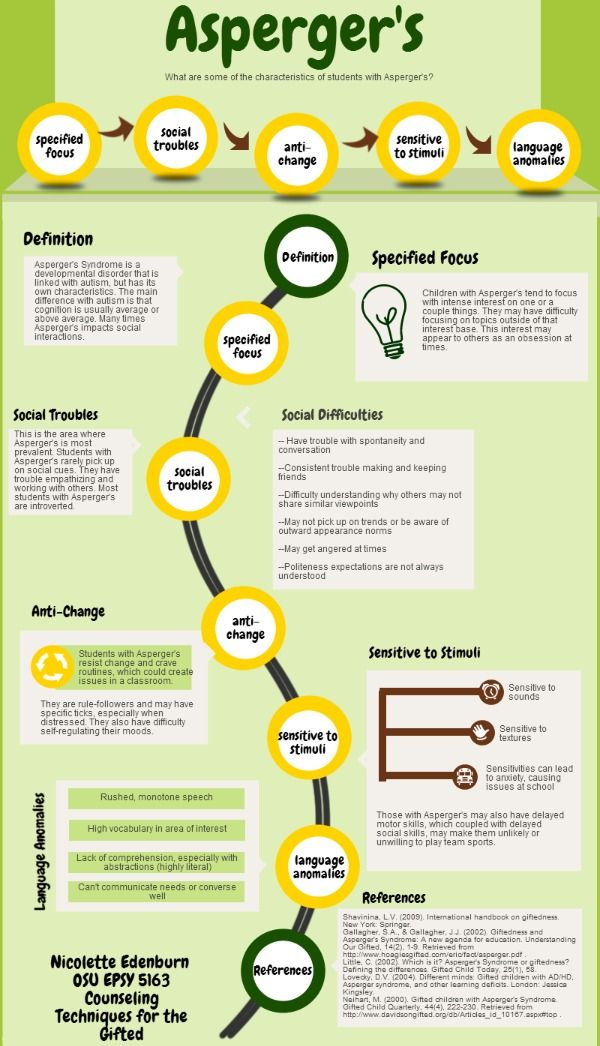

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Conduct disorder

- Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)

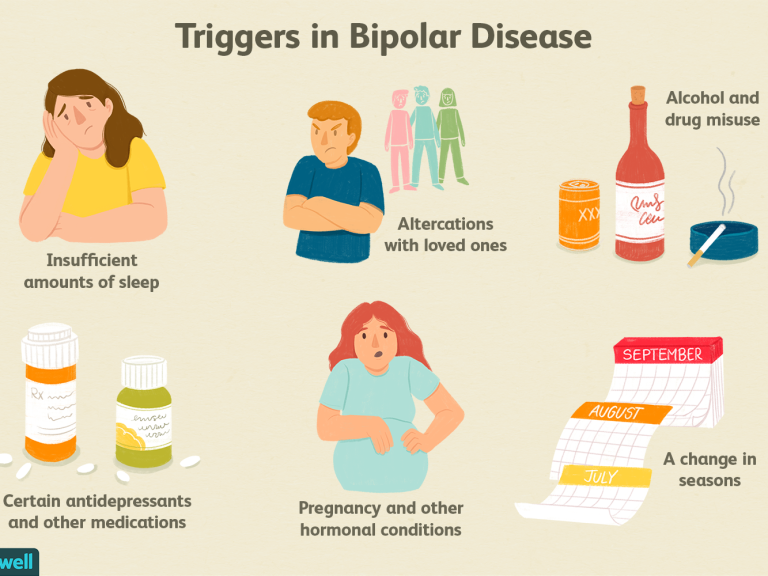

- Bipolar disorder

- Anxiety disorders

- Depressive disorders

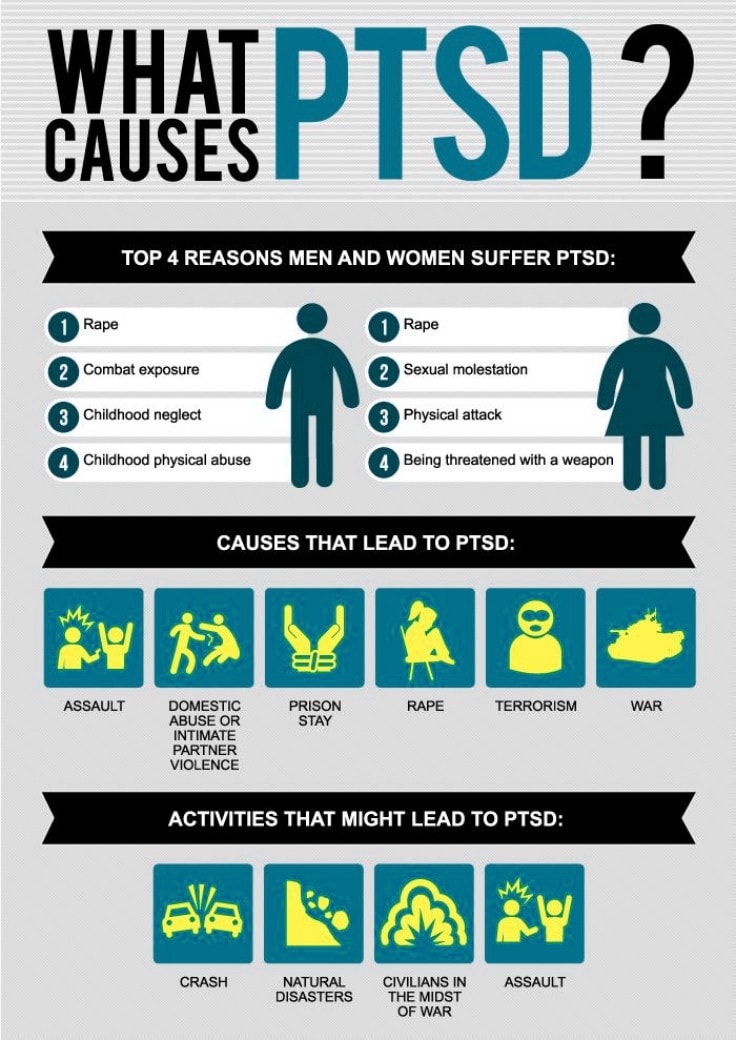

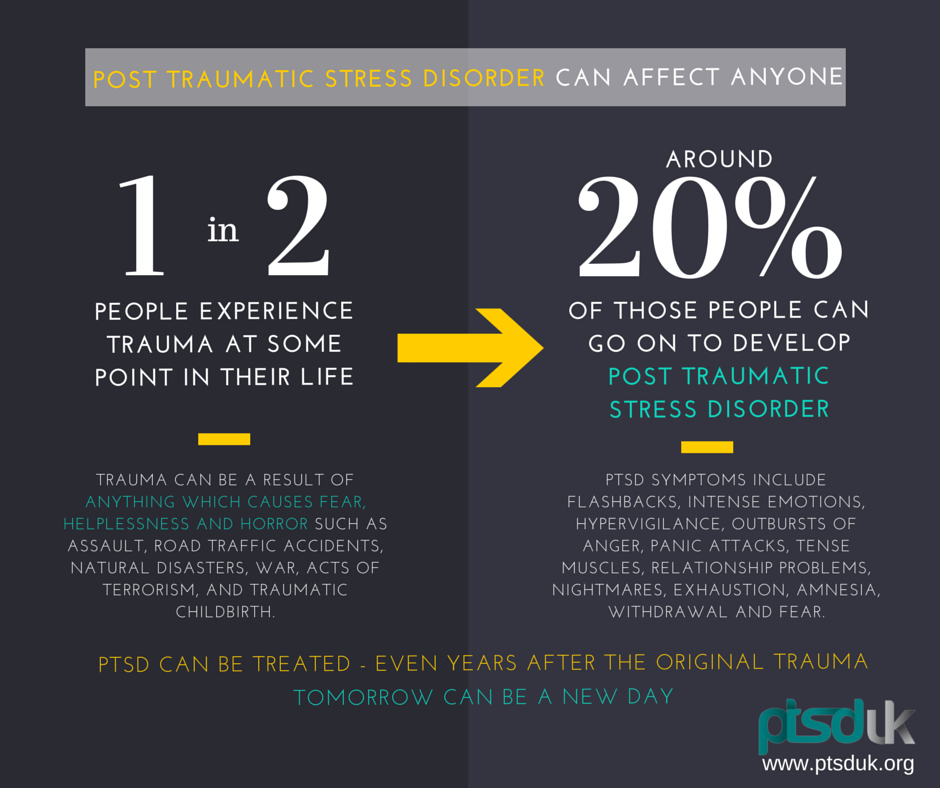

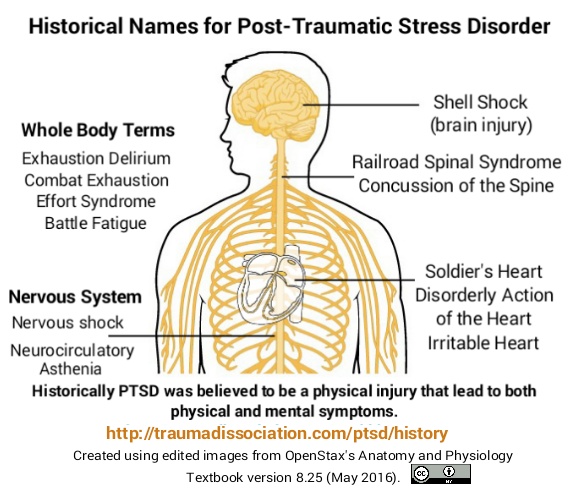

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

a new look at emotional dysregulation and treatment recommendations

People with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder often experience emotions with greater intensity than people who do not have this disorder. Moreover, comorbid conditions such as impulsive aggression and oppositional defiant disorder, as well as the side effects of medications, can make a person more likely to feel short-tempered, aggressive, impatient, and angry.

Moreover, comorbid conditions such as impulsive aggression and oppositional defiant disorder, as well as the side effects of medications, can make a person more likely to feel short-tempered, aggressive, impatient, and angry.

Natalya Chebakova

legion-media

Irritability, anger and emotional dysregulation in general have a strong impact on the psychosocial well-being of children and adults with attention deficit disorder (ADHD). Recent studies show that these problems may require special treatment. What is ADHD? It manifests itself with symptoms such as difficulty concentrating, hyperactivity, and poorly controlled impulsivity.

What is anger

Anger is an emotion, often of an aggressive nature, directed towards something or someone with the aim of destroying, suppressing, subjugating (often inanimate objects). Often the reaction of this negative emotion is short-lived.

Anger can literally burst a person from the inside. During an emotional outburst, a person’s facial muscles tense up, the body becomes like a stretched string, teeth and fists clench, the face begins to burn, there is a feeling that something is “boiling” inside, while there is no control over the mind.

During an emotional outburst, a person’s facial muscles tense up, the body becomes like a stretched string, teeth and fists clench, the face begins to burn, there is a feeling that something is “boiling” inside, while there is no control over the mind.

What is emotional dysregulation

Emotional dysregulation is the inability, even with considerable effort, to effectively influence and manage one's emotional experiences (anger, guilt, shame, rage, resentment), actions, verbal and non-verbal reactions and manage them. Emotional dysregulation manifests itself in many different life situations and leads to suffering and maladjustment of a person.

Ultimately, emotional dysregulation is one of the main reasons why ADHD is subjectively difficult to treat and why this disorder leads to a high risk of other problems such as depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorders.

In general, attention to anger and emotionality issues in ADHD patients is critical to successful treatment and symptom management in the long term.

Anger problems and ADHD

Emotional dysregulation and anger have been associated with ADHD since the mid-20th century, before modern diagnostic standards were established.

The most important aspect to consider is the nature of ADHD as a disorder of self-regulation of behavior, attention and emotions. In other words, any difficulty in regulating our thoughts, emotions, and actions—which is characteristic of ADHD—may explain the irritability, tantrums, and anger regulation problems that these people experience.

About 70% of adults with ADHD report problems with emotional dysregulation, and among children with ADHD this rises to 80%.

These problems include:

- Irritability: anger dysregulation problems - episodes of "tantrums" and chronic or generally negative feelings between episodes.

- Lability: frequent, reactive mood swings during the day.

- Recognition is the ability to accurately recognize the feelings of others. People with ADHD may tend not to notice other people's emotions until they are pointed out.

- Affective intensity: people with ADHD tend to experience emotions very strongly.

- Emotional dysregulation: inability to control emotions.

The genetic basis of ADHD and anger

From a genetic point of view, emotional dysregulation is closely related to ADHD. Such people often have irritability, anger, tantrums, and excessive pursuit of sensations, and more often than excessive impulsivity and arousal.

Anger problems and destructive mood dysregulation disorder

What is Destructive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD)

DMDD is a psychiatric disorder predominantly found in children and adolescents characterized by persistent irritable moods and frequent outbursts of anger that are disproportionate to the situation and significantly more severe than typical human responses the same age. Symptoms of ADHD resemble those of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), anxiety disorders, and bipolar disorder.

Symptoms of ADHD resemble those of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), anxiety disorders, and bipolar disorder.

Characteristics of ADDD

- Severe and recurring temper tantrums three or more times per week. These outbursts can be verbal or behavioral. Verbal outbursts are often described by observers as rage, fits, or tantrums. Children may scream, yell and cry for excessively long periods of time, sometimes without much provocation. Physical flashes can be directed at people or property. Children can throw objects; hitting, spanking or biting others; destroy toys or furniture; or otherwise act in a harmful or destructive manner.

- Constant irritable or angry mood. Parents, teachers, and classmates describe these children as usually angry, resentful, grumpy, or easily excitable. Unlike irritability, which can be a symptom of other disorders such as ODD, anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, irritability and anger in children with DDDD is not episodic or situational.

They are very pronounced and appear most of the day, almost every day in various conditions, and continue for one or several years.

They are very pronounced and appear most of the day, almost every day in various conditions, and continue for one or several years.

Problems with anger and bipolar disorder

What is bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder (previously manic -depressive psychosis) -endogenous mental disorder, manifested in the form of affective conditions: manic and depressive, and nervous state . Bipolar disorder is highly genetic and usually presents in late adolescence or early adulthood. The average age of onset of bipolar disorder is 18 to 20 years.

Mania means a marked change from normal in which a child or adult has an unusually high level of energy, less need for sleep, and an elated mood that lasts for at least a couple of days.

ADHD, ADHD, and bipolar disorder are all associated with anger and irritability in different ways. Understanding how they are related (and not related) is critical to ensuring proper diagnosis and targeted treatment of anger problems in patients.

Anger and ADHD Treatment Approaches

Behavior Therapy

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

when in fact there is no threat (for example, someone accidentally pushed in line). For such people, cognitive behavioral therapy helps them understand that something ambiguous is not necessarily a threat.

Internal regulation

Refers to what people can do to themselves to deal with uncontrollable anger. The key element here is the study of coping skills, their development and discussion with a specialist.

Here are some examples of coping skills:

- coping proactively or developing a plan to get out of a trigger situation: “I know that the next time this happens, I will be angry. What should I do to avoid this situation?”

- self-assessment and self-talk to keep yourself in check: "It was an accident" or "This person is just having a bad day and I don't react to it";

- shifting attention to something other than the upsetting situation.

Patient Counseling

Problems with anger can also be caused by difficulties with the transfer of frustration - this is a typical reaction to disappointment, the unfulfillment of hopes, the impossibility of self-realization. Counseling can help people with ADHD learn to tolerate common frustrations and develop better coping mechanisms.

Parent counseling

Parents of children with ADHD play a role in the child's anger. An angry reaction from parents can lead to a negative and mutual escalation, so that both parents and children begin to lose control of their emotions. By consulting with specialists, parents can learn how to respond differently to their child's tantrums, which will help reduce them over time.

Medications

Typical ADHD medications help with major symptoms but have modest results for anger problems.

Vitamins, minerals and trace elements

High doses of micronutrients can help adults with emotional attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Omega-3 supplementation has been shown to improve emotional control in children with ADHD.

youtube

Click and watch

Do you often get angry?

Help for a loved one with a mental disorder

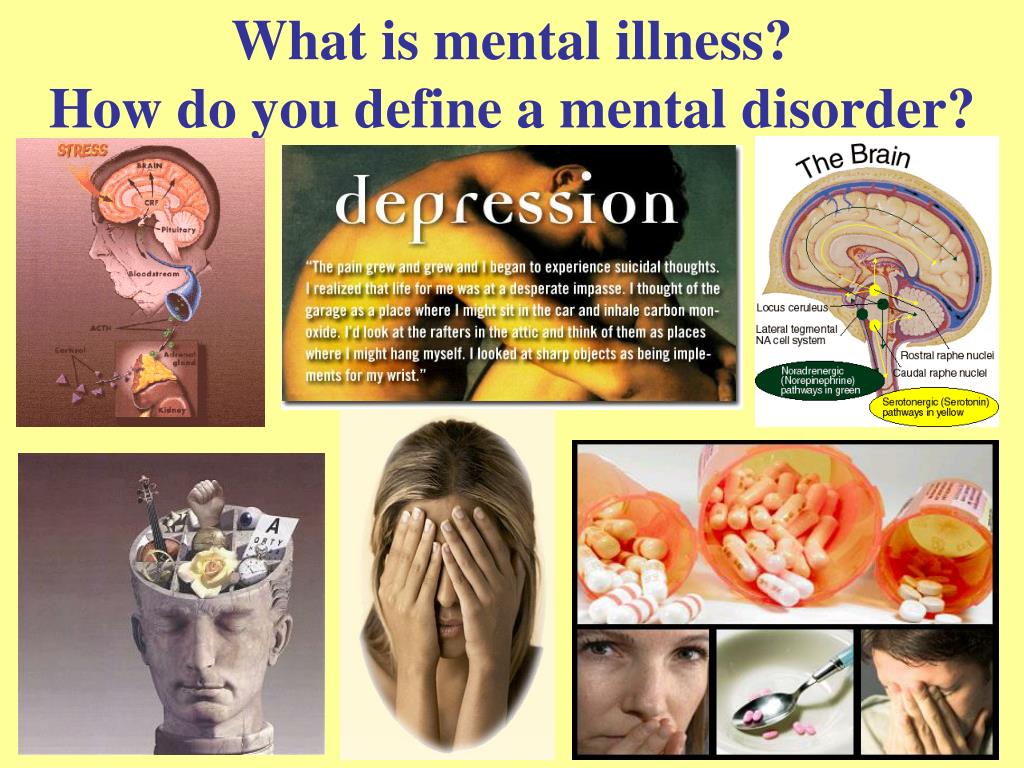

Basic concepts

There is a lot of talk these days about the rise in the number of mental disorders in society, but many people have very vague ideas about this very vague concept. Despite the fact that now psychiatrists are doing everything possible to inform the population as best as possible about stress, depression, anxiety, neuroses, more severe mental disorders, there is very little literature written by experts for the average layman, and on the Internet there is an abundance of information written either difficult language, or simply illiterate. All this ultimately leads to the fact that such information is not only contrary to reality, but also harmful.

All this ultimately leads to the fact that such information is not only contrary to reality, but also harmful.

It is impossible to sort everything out in one article and give clear instructions on the relationship between the patient and his relatives, but it is possible to bring to a holistic picture the idea of this complex group of diseases (the terms "disease" and "disorder" from a medical point of view are largely close, but not identical*). Therefore, my task is to acquaint the reader with this complex problem, primarily related to relationships and assistance to those suffering from severe mental illnesses.

* It is desirable to know the most basic terms, then it will be easier for the doctor to help both the patient himself and his relatives. In addition, you should not use terms that are not well known to you, it is better to describe the situation or condition as you understand it.

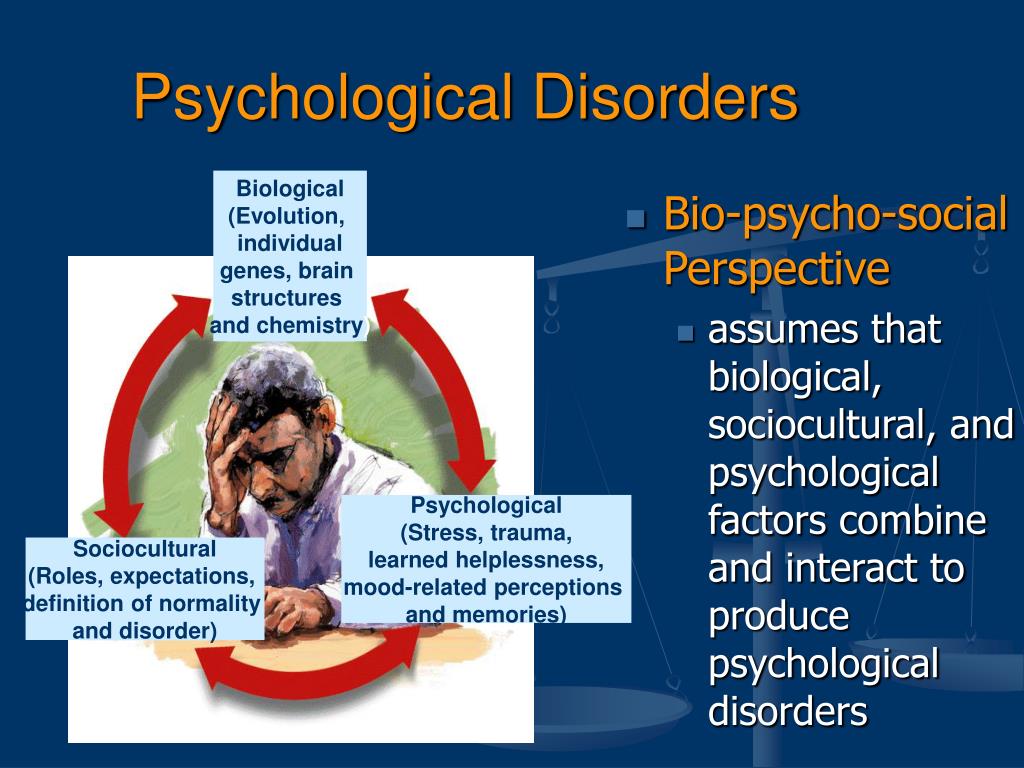

So, mental (or mental, because psyche - translated from Greek means the soul ) disorders - are painful conditions of a person with psychopathological (i. e., with mental disorders) and behavioral (i.e., they do not always appear, for example, in case of neurosis, when a person by willpower keeps himself within the limits of cultural society up to a certain point) manifestations due to the influence of biological, psychological, social and other factors.

e., with mental disorders) and behavioral (i.e., they do not always appear, for example, in case of neurosis, when a person by willpower keeps himself within the limits of cultural society up to a certain point) manifestations due to the influence of biological, psychological, social and other factors.

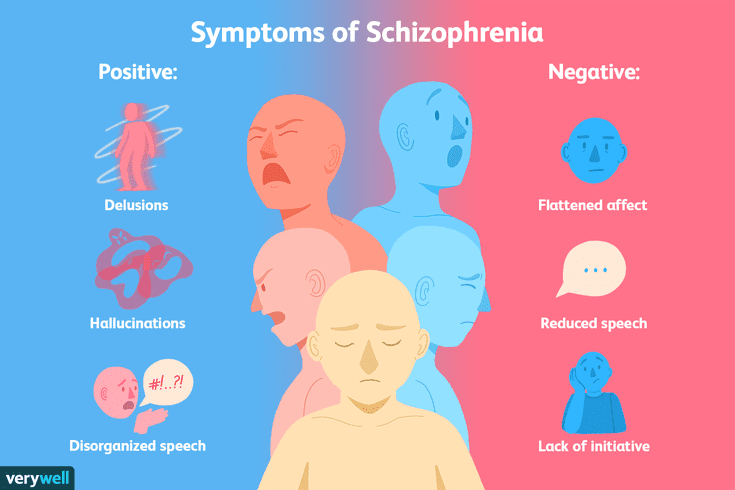

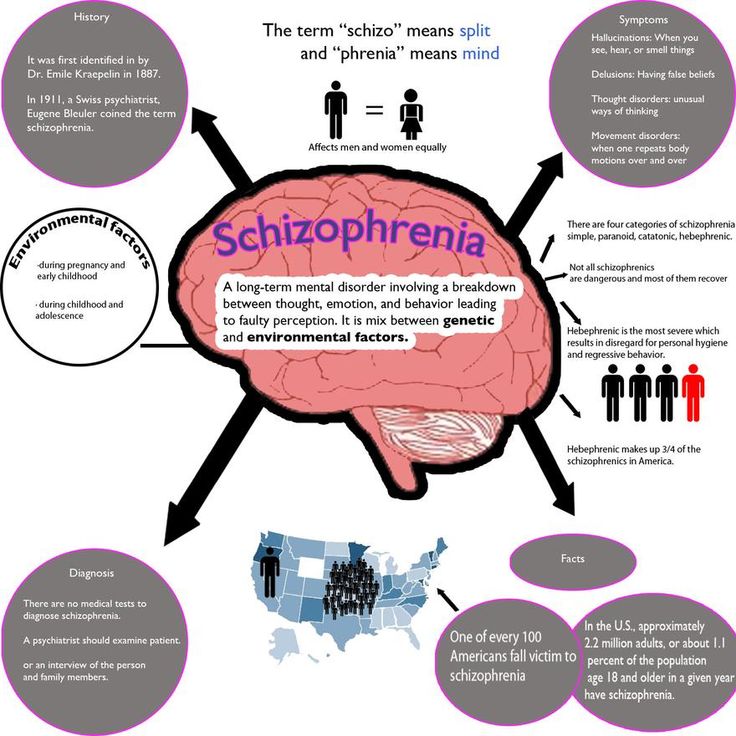

Let's not confuse with psychosis (or psychotic) disorders, which are characterized by gross and contradictory environmental disorders of thinking, perception and behavior (delusions, in a medical, not philistine view; hallucinations; psychomotor agitation; suicidal behavior, etc.).

It is important to note that the problem of mental disorders is interdisciplinary and even interdepartmental, social. Rehabilitation is needed, not just treatment.

As for the diagnosis. Diagnosis - definition and recognition, an indication of the disease. In medicine, and especially in psychiatry, diagnosis does not always mean treatment in strict accordance with the diagnosis. Diagnosis is often a statistical category needed to understand, roughly speaking, how the condition of one patient is similar to another.

Diagnosis is often a statistical category needed to understand, roughly speaking, how the condition of one patient is similar to another.

I am sometimes puzzled by the desire of a person to look at the records of a doctor. After all, a special interpretation, justification of the diagnosis, terminology can not only frighten and offend an unprepared person, but cause unreasonable distrust of a specialist and, even worse, aggravate disturbed mental balance, upset not only the patient, but also relatives.

It is much more important to trust each other (the doctor, the patient, his relatives), to ask questions of interest. It is on trust that the desired result is achieved - a cure or a stable remission, if the disorder is chronic.

I will not decipher concepts and terms much in this article. Let's talk about the topic corresponding to the title. We will talk about such diseases as schizophrenia, dementia, severe depression, drug addiction (alcoholism, drug addiction), etc. I will try to give basic, a kind of "universal" recommendations.

I will try to give basic, a kind of "universal" recommendations.

Recommendations

1 situation: a relative (both a 16-year-old child and an old grandfather, a researcher in the past or present) became “somehow not like that”, began to withdraw, get annoyed for no apparent reason, although “he had never been aggressive before ', to talk, to talk to oneself.

Usually, such behavior is first perceived as a joke, then surprise, then a discussion with a sick person begins, which can lead to serious conflicts and distrust. If you suspect that a person close to you has a mental disorder (we do not take emergency situations, for example, in case of severe aggression, the police and medical workers are already intervening here), you cannot argue.

It is also desirable not to support the painful delusions of a person, to try to be patient and caring, to persuade a loved one to seek medical help. Unfortunately, in our society, when it comes to psychiatry, in most cases it causes a smile, fear, surprise, but not sympathy and a desire to help a sick person, especially if it refers to a relative. Only later, when a sick person can feel and even understand that the help of a psychiatrist is for his benefit, will he himself reach out to her.

Only later, when a sick person can feel and even understand that the help of a psychiatrist is for his benefit, will he himself reach out to her.

At the initial stage, it is worth trying to persuade a person to calm down, assess his degree of adequacy (if he used to trust you, but now he doesn’t groundlessly, whether he understands you or is completely in his experiences, etc.), to understand whether there are threats to him and surrounding.

It is impossible to forcibly help a person (involuntary hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital is carried out only by a court decision), but everything possible must be done: to involve relatives who will correctly understand and support people who are authoritative for the patient, consult a doctor.

Situation 2: patients were brought to a psychiatrist. There can be 2 ways here. The doctor will help to understand the situation, make a diagnosis, prescribe treatment, give recommendations. Everything here is very individual. But it may also be that the doctor gives a recommendation, but not only the patient (due to inadequacy), but also a relative does not want to follow it.

But it may also be that the doctor gives a recommendation, but not only the patient (due to inadequacy), but also a relative does not want to follow it.

I can give an example. A mother brings her 20-year-old daughter to a psychotherapist. The daughter has painful sensations in her body: the bones, according to her, “go back and forth, fall through and hurt.” All specialists were examined, all studies were carried out, including MRI, no diseases were found, the symptoms do not correspond to the alleged physical pathology.

A mental illness was diagnosed, drugs were prescribed, and after a couple of months there was a significant improvement. The patient stops taking the medicine, after a while she comes to the doctor with her mother, complains about the deterioration, assures that the medicines do not help, refuses help, runs out of the office, rushes about, says that she does not want to live. Hospitalization is proposed, since adequate dosages of drugs can only be prescribed in a hospital, in response - a categorical refusal.

With difficulty he manages to calm down, persuade him to give an injection, agrees to resume taking medications. The doctor suggests that the mother call a psychiatric team to resolve the issue of hospitalization, in connection with the suicidal risk, to which he receives the answer: “Well, she will kill herself, then this is her fate, I will not put her in a psychiatric hospital.” On receipt released home. The mother calls the next day, the daughter gets a little better, then disappears for six months. Another call to the doctor's personal phone: the daughter lies in bed, does not want to get up, complains about "movements in the body of some creatures" that cause severe pain.

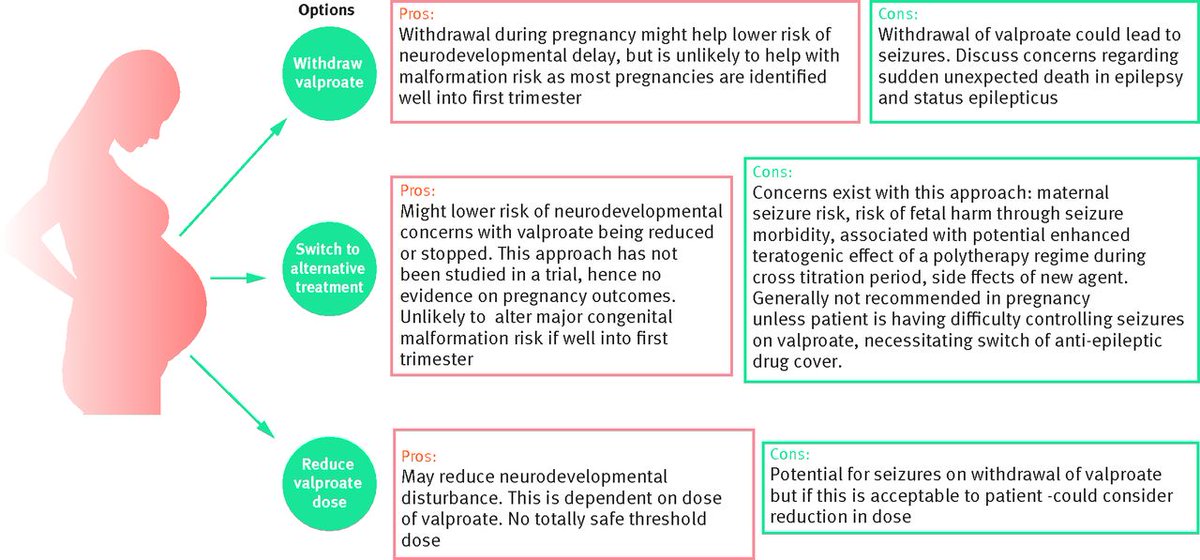

Recommendations were given, the patient was finally hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital with schizophrenia. She was discharged with improvement, criticism of her condition appeared, adequate therapy was selected.

Bottom line: fortunately, this story ended happily, but the patient suffered for several months, while the mother believed in the need for hospitalization; I had to prescribe heavier drugs, the treatment was delayed.

There is nothing wrong if the patient refuses this doctor (for example, the patient has included the doctor in his delusional system) or the doctor himself understands that he will not be able to provide adequate assistance. Then it is necessary to attract colleagues, send them to a hospital, together with relatives, think over options for assistance and choose the best one. It happens that the patient returns after treatment, apologizes for his behavior, because he did not understand the pain and inadequacy at that time.

You should not change specialists (sometimes people come to me with dozens of recommendations from different doctors of the same specialty, which is puzzling). Well, 2-3 opinions is understandable, but more than 10!? The most common reason is that medications do not immediately help, side effects.

Some patients soon stop taking their medications, and many diseases are chronic and require many months or even years of maintenance therapy. A natural deterioration sets in, the new doctor does not yet know the specifics of the course of the disorder in this patient, experiments with treatment begin, a new selection of medicines begins, resistance to treatment is formed, and previously effective drugs cease to work.

A natural deterioration sets in, the new doctor does not yet know the specifics of the course of the disorder in this patient, experiments with treatment begin, a new selection of medicines begins, resistance to treatment is formed, and previously effective drugs cease to work.

And one more thing: it is desirable, at the initial visit to the doctor, to bring, if not all, then the main examinations, extracts, and tests. A psychiatrist is a doctor like everyone else, and the more information about the patient, the easier it is to understand the diagnosis. For example, if a person has a pathology of the thyroid gland, it is advisable to bring the last tests for hormones, since when the hormonal background changes, the state of mind also changes (irritability, sleep disturbances, mood swings, etc.).

In some cases, antidepressants are not only not needed, but can be harmful, it may be worth limiting yourself to the appointments of an endocrinologist and psychotherapy. Elderly people with diabetes can confuse events and even behave inappropriately with an increase in blood glucose, here prescribed antipsychotics are also not always necessary.

Elderly people with diabetes can confuse events and even behave inappropriately with an increase in blood glucose, here prescribed antipsychotics are also not always necessary.

3 situation: the patient has been examined for a long time, the diagnosis is known, but the disease is progressing. Relatives begin to "look for a miracle": consult the patient with leading specialists, go to the main scientific centers, someone is looking for help abroad.

I have had a number of cases where patients have returned from the US, Europe, Israel, etc. with complaints that the prescription of drugs selected in Russia was refused, or that the treatment was simply ineffective, worsened. Here I would advise you to find a specialist you trust and coordinate your actions with him. Only together can we help sick people provide adequate assistance and, if not cured, then improve the quality of life as much as possible.

4 situation: terminally ill patient in the final stage. There is an opinion, or rather another myth, that one does not die from mental illness, however, mental illness is the same as somatic (i.e. body diseases), only the brain is sick, regardless there is a visible focus there (for example, as a result of a craniocerebral injury to the damaged part of the brain) or not. For example, severe progressive dementia, the final stage of alcoholism with multiple organ disorders, the terminal stage in malignant forms of schizophrenia, and others. Here it is necessary to decide individually, depending on the specific case.

There is an opinion, or rather another myth, that one does not die from mental illness, however, mental illness is the same as somatic (i.e. body diseases), only the brain is sick, regardless there is a visible focus there (for example, as a result of a craniocerebral injury to the damaged part of the brain) or not. For example, severe progressive dementia, the final stage of alcoholism with multiple organ disorders, the terminal stage in malignant forms of schizophrenia, and others. Here it is necessary to decide individually, depending on the specific case.

“If a person cannot be cured, this does not mean that he cannot be helped.”

If you are destined to die, it is easier to do this among loving relatives on your bed, even if a person does not understand anything and does not recognize anyone. But he FEELS the attitude towards him. How a small child feels the caress of his mother, smiles or cries when his mother is gone. You will say - there is no comparison, children are our future, and here is a dying person who does not understand anything. Yes, this is true, but we must understand that any of us can, God forbid, be in the place of this person ...

Yes, this is true, but we must understand that any of us can, God forbid, be in the place of this person ...

Nursing staff

Well, a few words about help for those who care for the sick. It is difficult to give specific recommendations here, only one thing is clear: you cannot take the position of either a rescuer or a victim, you just need to fulfill your human duty to the best of your ability and ability. Don't forget yourself.

Any person who lives with a sick person, and even more so caring for him, experiences enormous personal and emotional stress. Therefore, you should think about how you will cope with the disease in the future. By understanding your own emotions properly, you will be able to deal more effectively with both the patient's problems and your own problems. You may have to experience emotions such as grief, shame, anger, embarrassment, loneliness and others.

For some people who care for the sick, the family is the best helper, for others it brings only grief. It is important not to reject the help of other family members if they have enough time, and not to try to bear the sometimes difficult burden of caring for the sick alone.

It is important not to reject the help of other family members if they have enough time, and not to try to bear the sometimes difficult burden of caring for the sick alone.

If family members upset you with their unwillingness to help, or criticize your work because of the lack of information about this disorder, you can form a family council to discuss care problems. In particular, make a decision to involve an employee, at least for the period of time necessary for your rest and recuperation, and, if necessary, treatment.

And the last. Don't keep problems to yourself. Feeling that your emotions are a natural reaction in your position, it will be easier for you to cope with your problems. Don't reject the help and support of others, even if you feel like you're making it difficult. Even psychotherapists themselves (seemingly knowing how to minimize stress as much as possible) often have their own psychotherapist, and it is bad for the doctor who neglects the help of his colleagues.