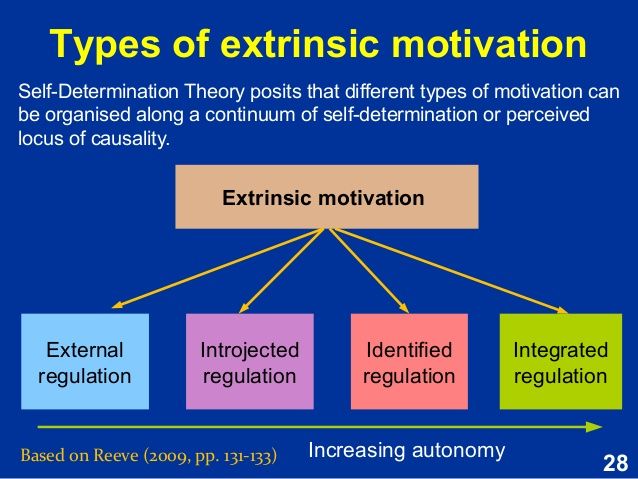

What is extrinsic motivation in psychology

What Is It and How Does It Work?

Definition

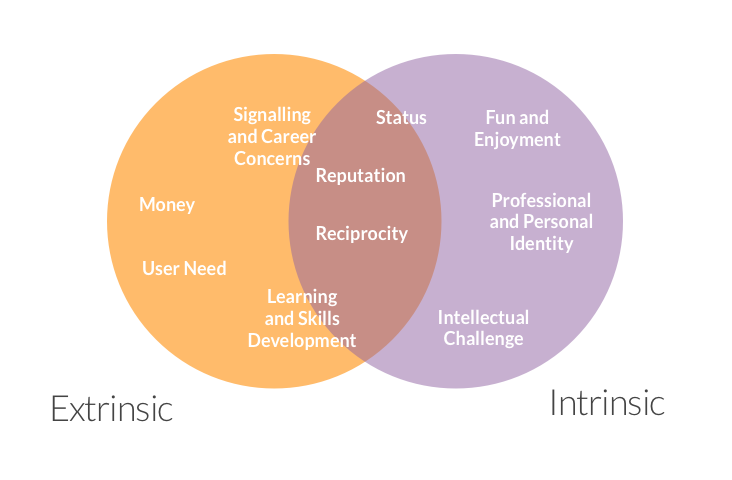

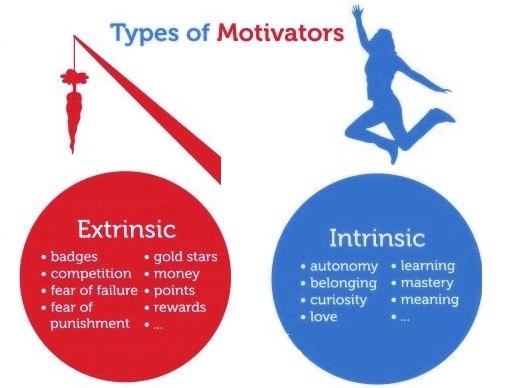

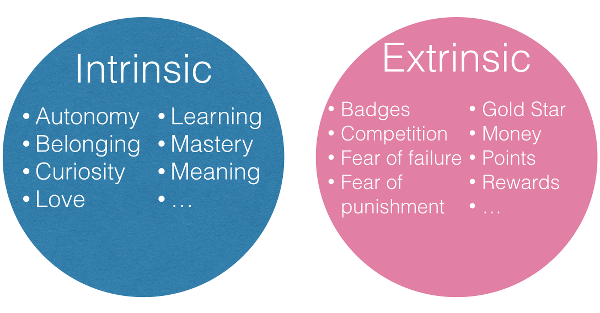

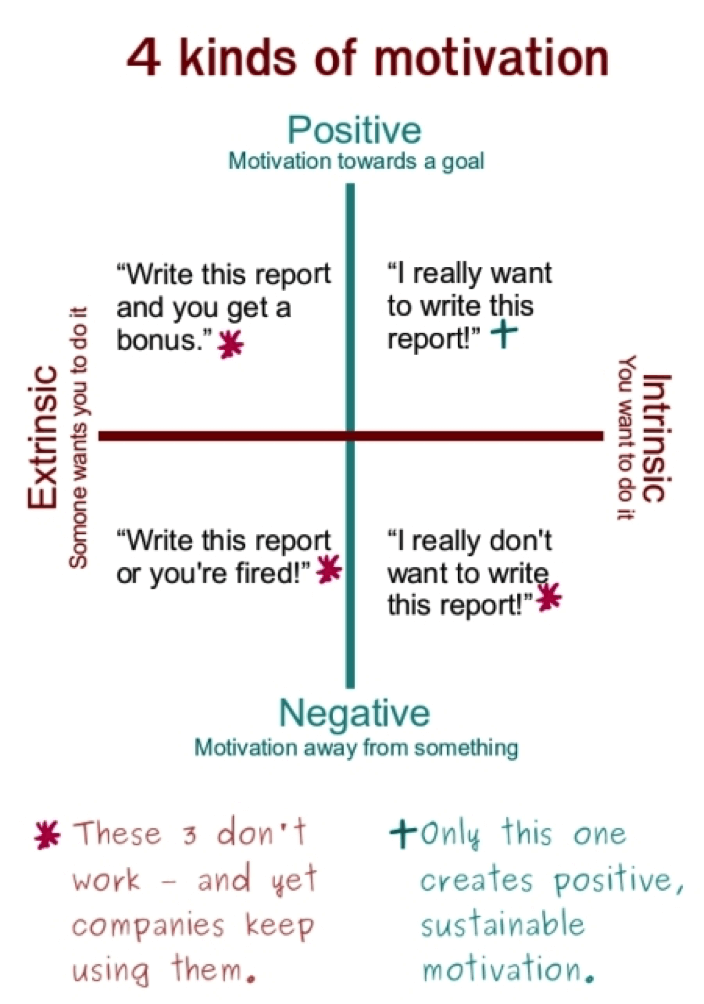

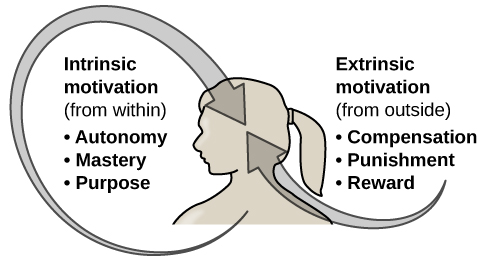

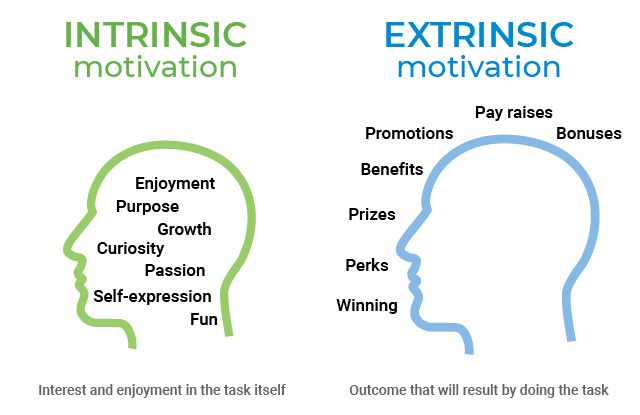

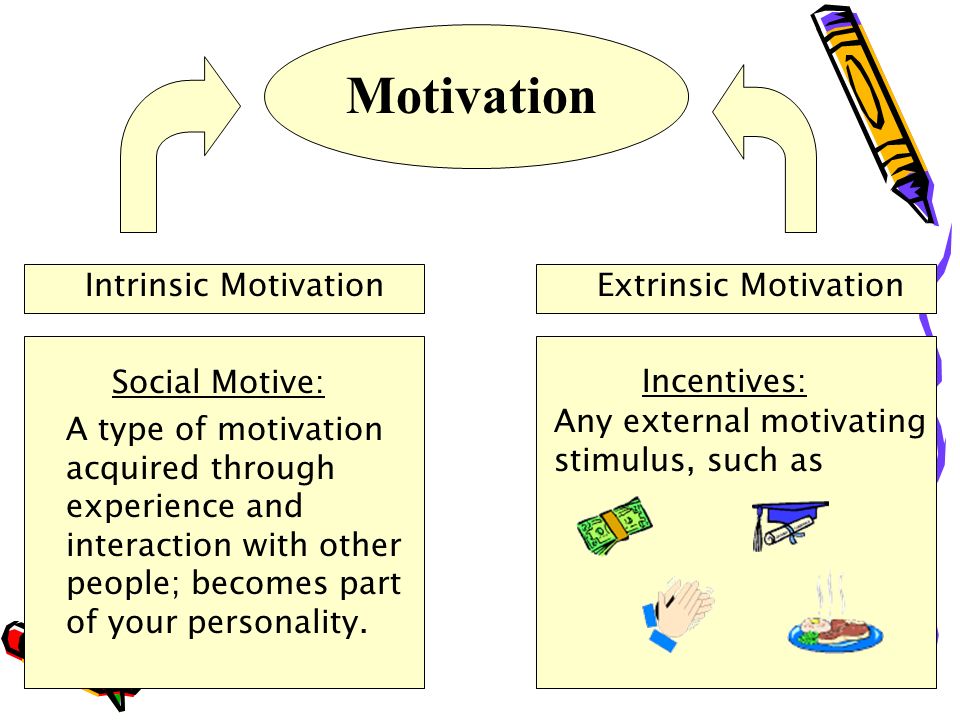

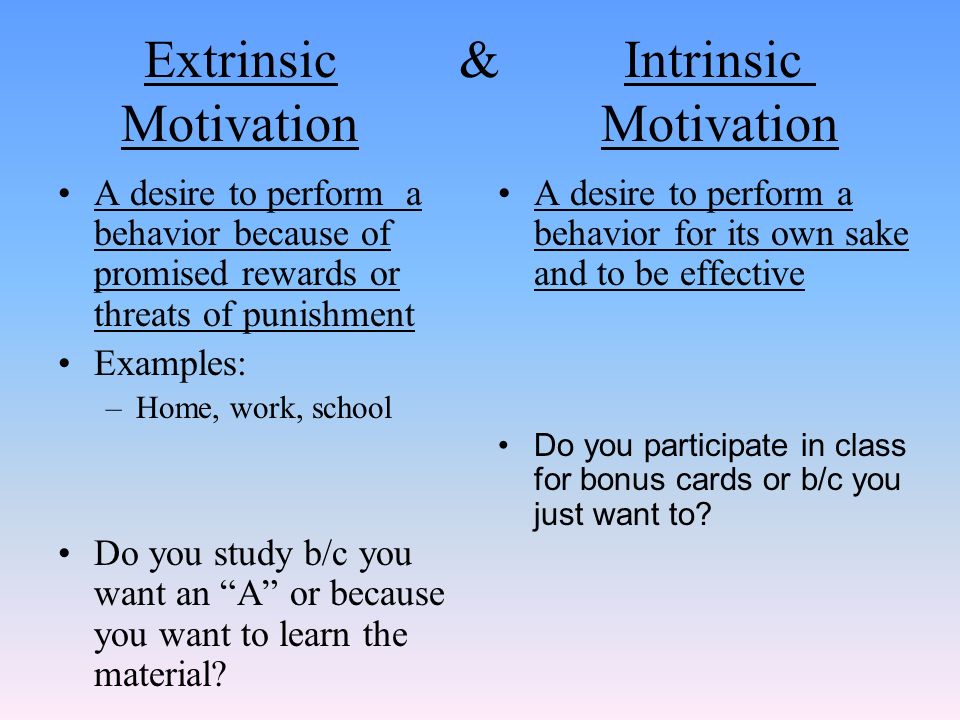

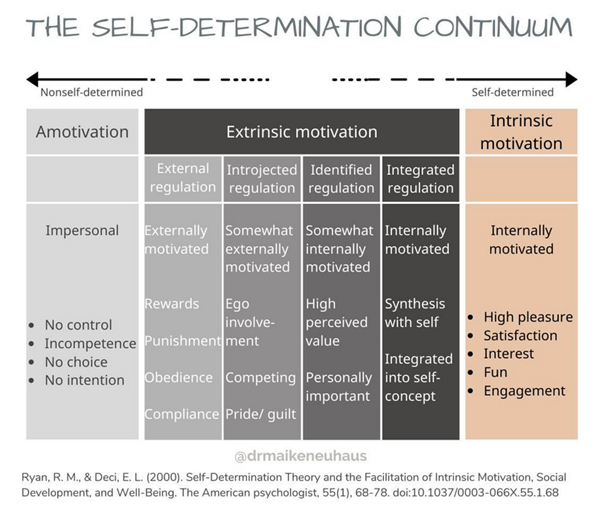

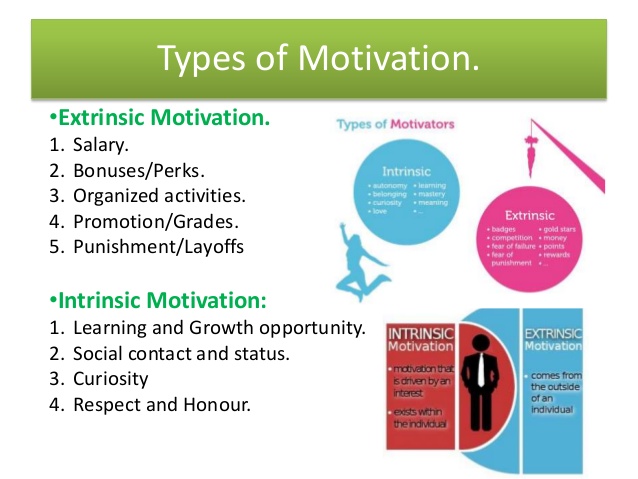

Extrinsic motivation is reward-driven behavior. It’s a type of operant conditioning. Operant conditioning is a form of behavior modification that uses rewards or punishments to increase or decrease the likelihood that specific behaviors will recur.

In extrinsic motivation, rewards or other incentives — like praise, fame, or money — are used as motivation for specific activities. Unlike intrinsic motivation, external factors drive this form of motivation.

Being paid to do a job is an example of extrinsic motivation. You may enjoy spending your day doing something other than work, but you’re motivated to go to work because you need a paycheck to pay your bills. In this example, you’re extrinsically motivated by the ability to afford your daily expenses. In return, you work a set number of hours a week to receive pay.

Extrinsic motivation doesn’t always have a tangible reward. It can also be done through abstract rewards, like praise and fame.

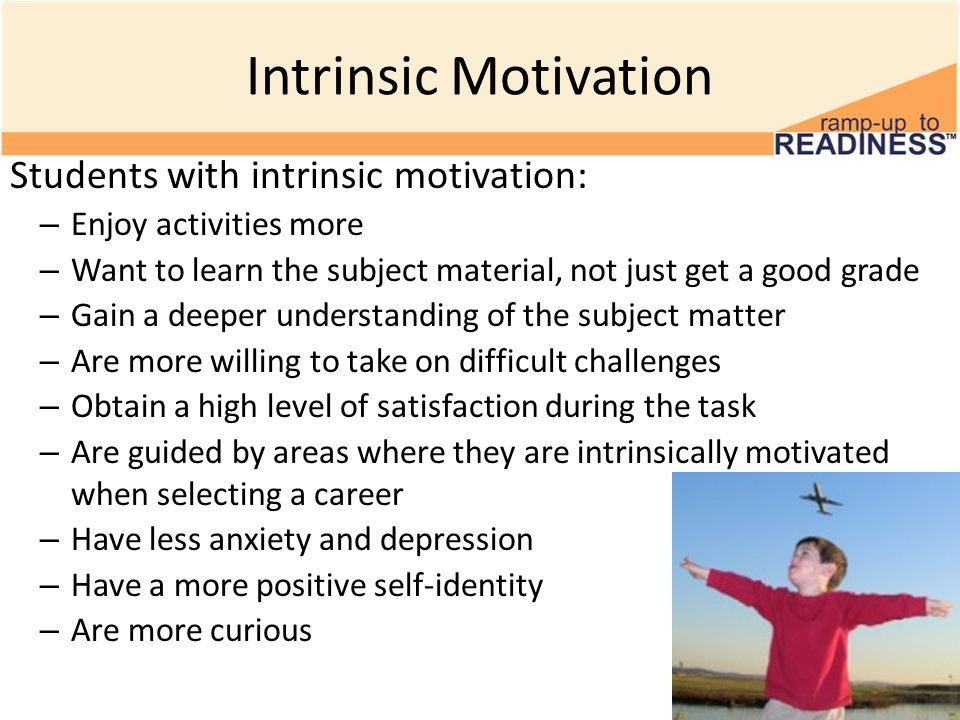

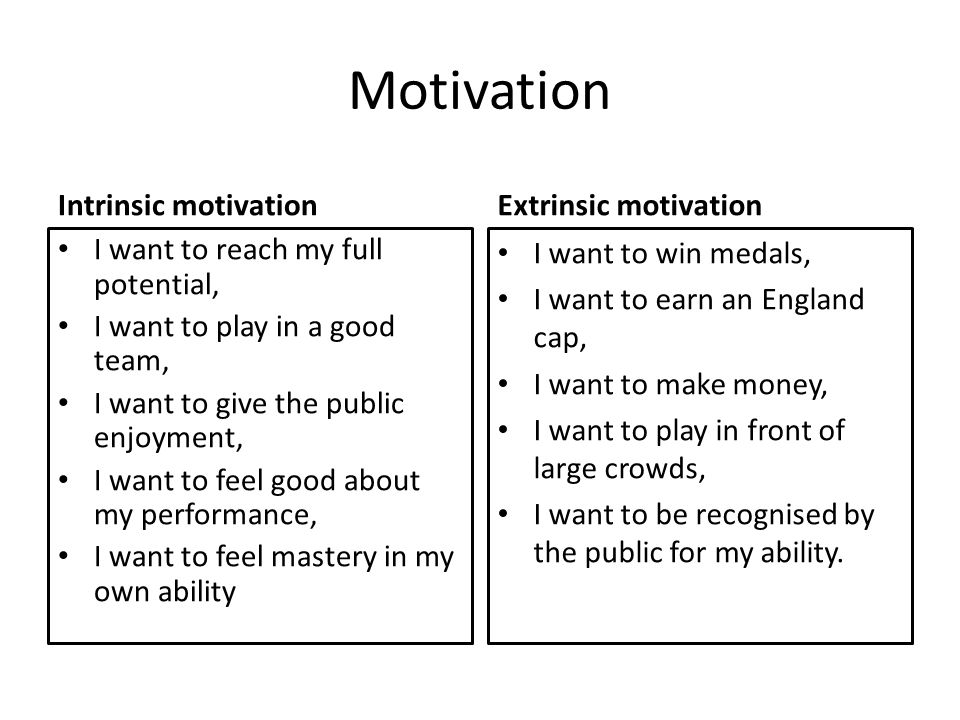

In contrast, intrinsic motivation is when internal forces like personal growth or a desire to succeed fuel your drive to complete a task. Intrinsic motivation is typically seen as a more powerful incentive for behaviors that require long-term execution.

Extrinsic motivation can be used to motivate you to do various different things. If there’s a known reward tied to the task or outcome, you may be extrinsically motivated to complete the task.

Examples of external extrinsic rewards include:

- competing in sports for trophies

- completing work for money

- customer loyalty discounts

- buy one, get one free sales

- frequent flyer rewards

Examples of psychological extrinsic rewards include:

- helping people for praise from friends or family

- doing work for attention, either positive or negative

- doing tasks for public acclaim or fame

- doing tasks to avoid judgment

- completing coursework for grades

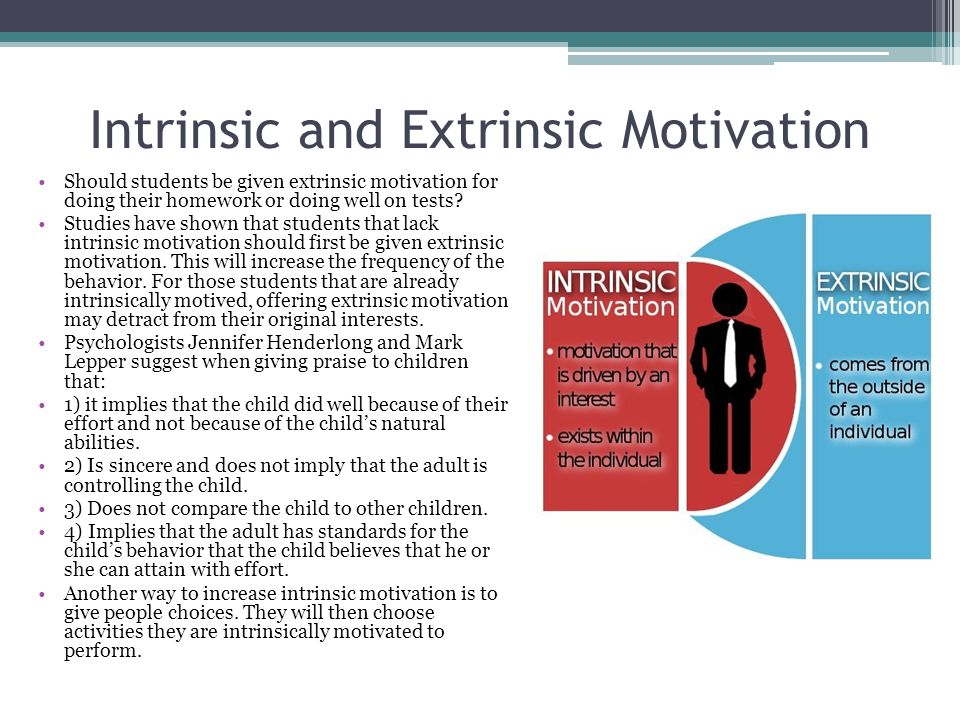

Extrinsic motivation may be more effective for some people than it is for others. Certain situations may also be better suited for this form of motivation. For some people, the benefits of external rewards are enough to motivate high-quality continuous work. For others, value-based benefits are more motivating.

Certain situations may also be better suited for this form of motivation. For some people, the benefits of external rewards are enough to motivate high-quality continuous work. For others, value-based benefits are more motivating.

Extrinsic motivation is best used in circumstances when the reward is used sparingly enough so it doesn’t lose its impact. The value of the reward can decrease if the reward is given too much. This is sometimes referred to as the overjustification effect.

The overjustification effect happens when an activity you already enjoy is rewarded so often that you lose interest. In one study, researchers looked at the way 20-month-olds responded to material rewards compared to their response to social praise or no reward. Researchers found that the group that received material rewards was less likely to engage in the same helpful behaviors in the future. This suggests that the overjustification effect can start at an early age.

There’s some evidence that an excessive amount of extrinsic rewards can lead to a decrease in intrinsic motivation. Not all researchers agree, however. The idea was first explored in a study published in 1973.

Not all researchers agree, however. The idea was first explored in a study published in 1973.

During the study, some children were rewarded for playing with felt-tip pens. This was an activity they already enjoyed. Other children weren’t rewarded for this activity. After continued reward, the reward group no longer wanted to play with the pens. The study participants who weren’t rewarded continued to enjoy playing with the pens.

A meta-analysis from 1994 found little evidence to support the conclusions from the 1973 study. Instead, they determined that extrinsic motivation didn’t affect long-term enjoyment of activities. However, a follow-up meta-analysis published in 2001 found evidence to support the original theory from 1973.

Finally, a more recent meta-analysis from 2014 determined that extrinsic motivation only has negative outcomes in very specific situations. But for the most part, it can be an effective form of motivation.

Depending on how it’s used, it’s possible that extrinsic motivation could have negative long-term effects. It’s likely an effective method when used in addition to other forms of motivation.

It’s likely an effective method when used in addition to other forms of motivation.

A major drawback to using extrinsic motivation is knowing what to do when the reward is gone or its value is exhausted. There’s also the possibility of dependency on the reward.

The usefulness of extrinsic motivators should be evaluated on a case-by-case and person-by-person basis.

Very few studies have explored the long-term effects of continuous extrinsic motivation use with children. Extrinsic motivation can be a useful tool for parents to teach children tasks and responsibilities.

Certain extrinsic motivators, like support and encouragement, may be healthy additions to parenting practices. Some rewards are often discouraged because it may lead to unhealthy associations with the rewards later in life. For example, using food as a reward may lead to unhealthy eating habits.

For small developmental tasks, extrinsic motivators like praise can be very helpful. For instance, using praise can help with toilet training. If you use external rewards, try phasing them out over time so that your child doesn’t become dependent on the reward.

If you use external rewards, try phasing them out over time so that your child doesn’t become dependent on the reward.

Extrinsic motivation can be useful for persuading someone to complete a task. Before assigning a reward-based task, it’s important to know if the person doing the task is motivated by the reward being offered. Extrinsic motivators may be a useful tool to help children learn new skills when used in moderation.

For some people, psychological extrinsic motivators are more appealing. For others, external rewards are more attractive. It’s important to remember, however, that extrinsic motivation isn’t always effective.

What Is It and How Does It Work?

Definition

Extrinsic motivation is reward-driven behavior. It’s a type of operant conditioning. Operant conditioning is a form of behavior modification that uses rewards or punishments to increase or decrease the likelihood that specific behaviors will recur.

In extrinsic motivation, rewards or other incentives — like praise, fame, or money — are used as motivation for specific activities. Unlike intrinsic motivation, external factors drive this form of motivation.

Unlike intrinsic motivation, external factors drive this form of motivation.

Being paid to do a job is an example of extrinsic motivation. You may enjoy spending your day doing something other than work, but you’re motivated to go to work because you need a paycheck to pay your bills. In this example, you’re extrinsically motivated by the ability to afford your daily expenses. In return, you work a set number of hours a week to receive pay.

Extrinsic motivation doesn’t always have a tangible reward. It can also be done through abstract rewards, like praise and fame.

In contrast, intrinsic motivation is when internal forces like personal growth or a desire to succeed fuel your drive to complete a task. Intrinsic motivation is typically seen as a more powerful incentive for behaviors that require long-term execution.

Extrinsic motivation can be used to motivate you to do various different things. If there’s a known reward tied to the task or outcome, you may be extrinsically motivated to complete the task.

Examples of external extrinsic rewards include:

- competing in sports for trophies

- completing work for money

- customer loyalty discounts

- buy one, get one free sales

- frequent flyer rewards

Examples of psychological extrinsic rewards include:

- helping people for praise from friends or family

- doing work for attention, either positive or negative

- doing tasks for public acclaim or fame

- doing tasks to avoid judgment

- completing coursework for grades

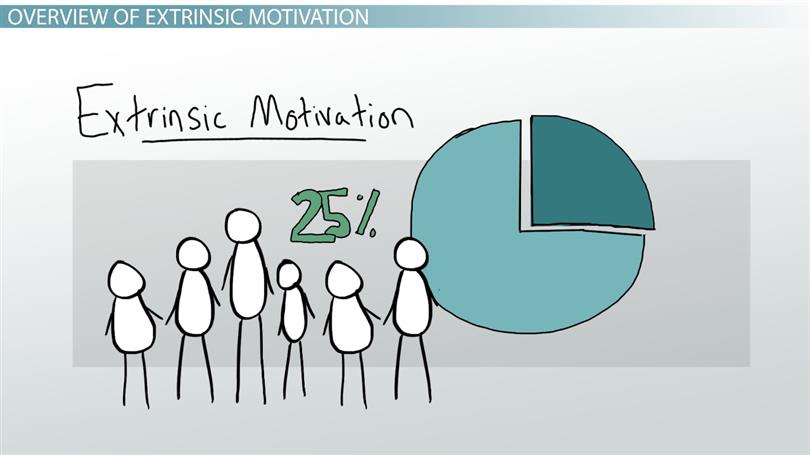

Extrinsic motivation may be more effective for some people than it is for others. Certain situations may also be better suited for this form of motivation. For some people, the benefits of external rewards are enough to motivate high-quality continuous work. For others, value-based benefits are more motivating.

Extrinsic motivation is best used in circumstances when the reward is used sparingly enough so it doesn’t lose its impact. The value of the reward can decrease if the reward is given too much. This is sometimes referred to as the overjustification effect.

The value of the reward can decrease if the reward is given too much. This is sometimes referred to as the overjustification effect.

The overjustification effect happens when an activity you already enjoy is rewarded so often that you lose interest. In one study, researchers looked at the way 20-month-olds responded to material rewards compared to their response to social praise or no reward. Researchers found that the group that received material rewards was less likely to engage in the same helpful behaviors in the future. This suggests that the overjustification effect can start at an early age.

There’s some evidence that an excessive amount of extrinsic rewards can lead to a decrease in intrinsic motivation. Not all researchers agree, however. The idea was first explored in a study published in 1973.

During the study, some children were rewarded for playing with felt-tip pens. This was an activity they already enjoyed. Other children weren’t rewarded for this activity. After continued reward, the reward group no longer wanted to play with the pens. The study participants who weren’t rewarded continued to enjoy playing with the pens.

After continued reward, the reward group no longer wanted to play with the pens. The study participants who weren’t rewarded continued to enjoy playing with the pens.

A meta-analysis from 1994 found little evidence to support the conclusions from the 1973 study. Instead, they determined that extrinsic motivation didn’t affect long-term enjoyment of activities. However, a follow-up meta-analysis published in 2001 found evidence to support the original theory from 1973.

Finally, a more recent meta-analysis from 2014 determined that extrinsic motivation only has negative outcomes in very specific situations. But for the most part, it can be an effective form of motivation.

Depending on how it’s used, it’s possible that extrinsic motivation could have negative long-term effects. It’s likely an effective method when used in addition to other forms of motivation.

A major drawback to using extrinsic motivation is knowing what to do when the reward is gone or its value is exhausted. There’s also the possibility of dependency on the reward.

There’s also the possibility of dependency on the reward.

The usefulness of extrinsic motivators should be evaluated on a case-by-case and person-by-person basis.

Very few studies have explored the long-term effects of continuous extrinsic motivation use with children. Extrinsic motivation can be a useful tool for parents to teach children tasks and responsibilities.

Certain extrinsic motivators, like support and encouragement, may be healthy additions to parenting practices. Some rewards are often discouraged because it may lead to unhealthy associations with the rewards later in life. For example, using food as a reward may lead to unhealthy eating habits.

For small developmental tasks, extrinsic motivators like praise can be very helpful. For instance, using praise can help with toilet training. If you use external rewards, try phasing them out over time so that your child doesn’t become dependent on the reward.

Extrinsic motivation can be useful for persuading someone to complete a task. Before assigning a reward-based task, it’s important to know if the person doing the task is motivated by the reward being offered. Extrinsic motivators may be a useful tool to help children learn new skills when used in moderation.

Before assigning a reward-based task, it’s important to know if the person doing the task is motivated by the reward being offered. Extrinsic motivators may be a useful tool to help children learn new skills when used in moderation.

For some people, psychological extrinsic motivators are more appealing. For others, external rewards are more attractive. It’s important to remember, however, that extrinsic motivation isn’t always effective.

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation - Psychologos

Film "Dan Pink"

External motivation is an inducement or coercion to do something by circumstances or stimuli external to a person.

A thundercloud on the horizon is very motivating to quickly run home from the forest. They promised people a bonus - they began to move faster. We wrote the rules to the employees, imposed fines - whether you like it or not, the employees began to focus on the rules. A man who suddenly appeared from the gateway pointed a gun at you and demanded a wallet from you - you will give the wallet without much hesitation.

Intrinsic motivation - motivation that a person carries within himself, regardless of the external environment.

Intrinsically motivated behavior - behavior that occurs in the absence of any explicit external reward. Or - when it is not clear what external motives and reinforcements guide a person. How different psychologists explain this phenomenon, see Intrinsic motivation in psychology

Intrinsic motivation is not associated with external circumstances, not with incentives and reinforcements, but, first of all, with the very content of activity.

A small child is always trying something, exploring everything - and it seems that this is determined not so much by the stimuli around him, but comes from himself.

Adult: "I don't work for a salary, I love my job. Here I have everything to be happy, and my reward is my activity itself!"

At the same time, it is wrong to think that internal motivation is born only inside a person and cannot be created from the outside: how else can it be! Japanese Emperor Hirohito, capitulating in World War II, gave his generals the task: "Leave the army, create the industry of Japan!" - and this became the real life work of his generals, and as a result - the source of the Japanese economic miracle. Little Paganini was forced to play the violin for 6-8 hours a day: they were forced, but as a result, the great violinist Nicolo Paganini was born.

Little Paganini was forced to play the violin for 6-8 hours a day: they were forced, but as a result, the great violinist Nicolo Paganini was born.

Comparative efficiency

When solving simple tasks where you just need not to be distracted - you just need to work and work - external motivation is more effective.

Pay more money - better results.

When solving complex, creative problems, external motivation is not only less effective, but has the opposite, negative effect.

More pay - less results.

By rewarding people for what they would have done without any reward, we undermine their intrinsic motivation. by forgoing rewards and threats, and by allowing people to find inner motives for doing good deeds, they can get them to do them on their own initiative and enjoy it.

Controversial issues

If a person wants to go to the toilet, is it extrinsic or intrinsic motivation? It seems to be internal, but in fact it is forced to go there by the bladder. If a person believes that his body is him, then YES, this is intrinsic motivation. And if a person does not identify with his body, considers himself something not reducible to the body and learns to live according to the laws of the spirit (or at least according to the rules accepted by people), and not what his body dictates to him, then pressure from the bladder for him external pressure. And if he ran to the toilet - he is driven by external motivation!

If a person believes that his body is him, then YES, this is intrinsic motivation. And if a person does not identify with his body, considers himself something not reducible to the body and learns to live according to the laws of the spirit (or at least according to the rules accepted by people), and not what his body dictates to him, then pressure from the bladder for him external pressure. And if he ran to the toilet - he is driven by external motivation!

A woman takes care of her husband - because she loves (intrinsic motivation) or because it's sour without her husband, and she can't find another? - Then it seems that this is already an external motivation ...

For a developed person, for a person in the position of the Author, any motivation, whether external or internal, sets only the background of his life. If you submit to this background, if it is not a background, but the reason for your behavior, you are in the position of the Victim. "There is motivation - I act. Motivation is over - what can I do?" If you use motivation as a sail and can create your own motivation at the right time on your own (according to the principle "Want to want!"), you are the Author of your life.

Motivation is over - what can I do?" If you use motivation as a sail and can create your own motivation at the right time on your own (according to the principle "Want to want!"), you are the Author of your life.

V.I. Chirkov. External and internal motivation: Psychology OnLine.Net

IN AND. Chirkov. External and internal motivation

Added by Psychology OnLine.Net

3.12.2007

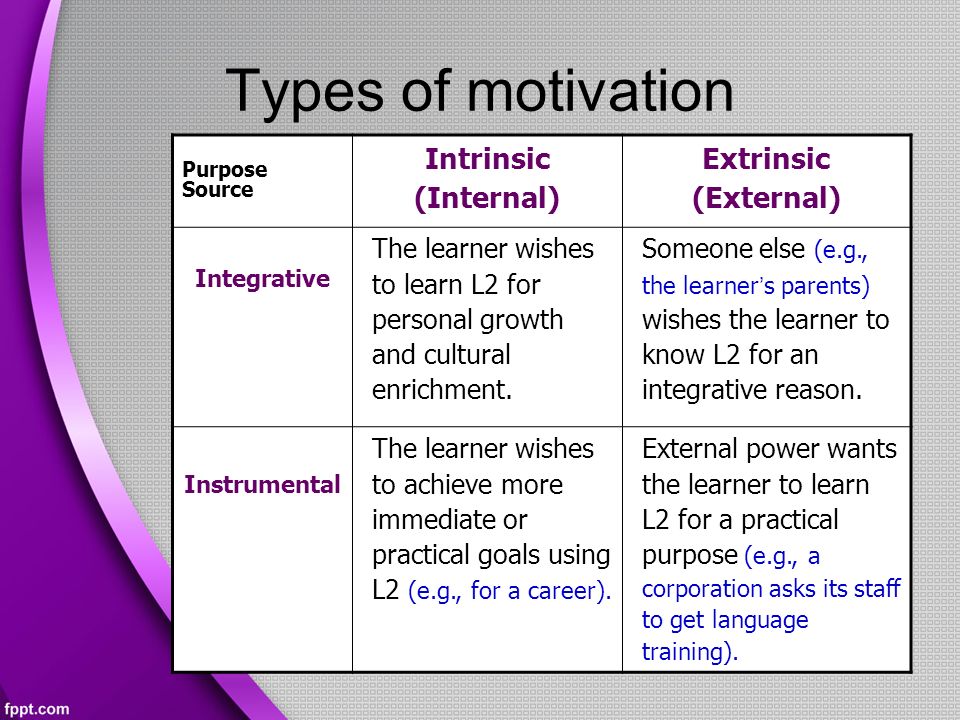

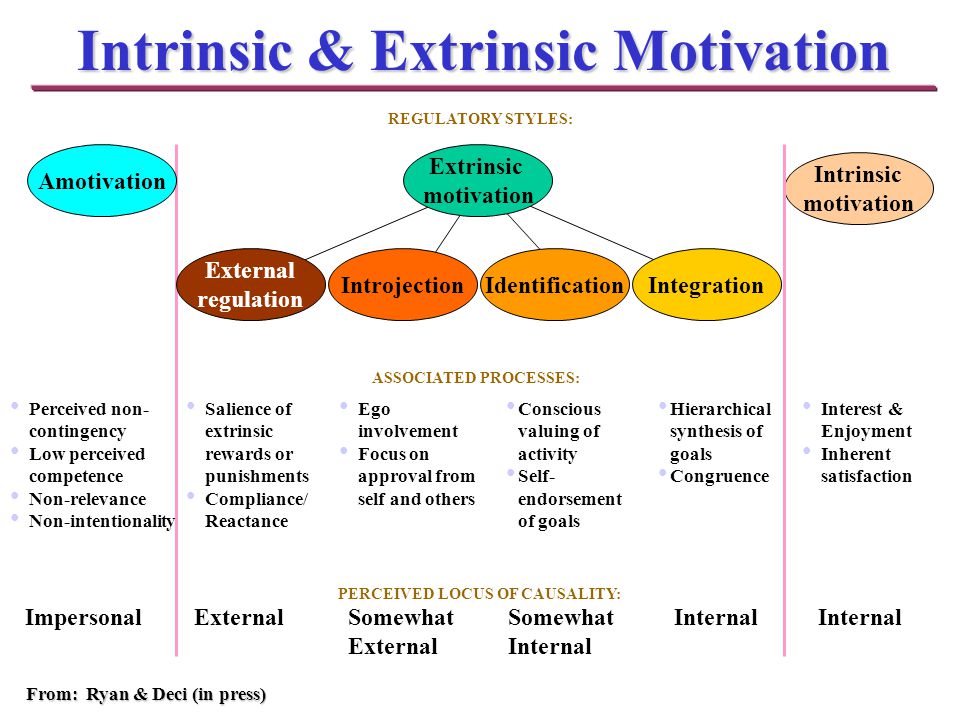

Most psychologists agree with the allocation of two types of motivation and two types of behavior corresponding to them: 1) external motivation (extrinsic motivation) and, accordingly, externally motivated behavior (extrinsic motivated behavior) and 2) internal motivation (intrinsic motivation) and, accordingly, internally motivated behavior ( inherent motivated behavior).

External motivation is a construct for describing the determination of behavior in those situations when the factors that initiate and regulate it are outside the I (self)1 of the person or outside the behavior. It is enough for the initiating and regulating factors to become external, as all motivation acquires an external character.

It is enough for the initiating and regulating factors to become external, as all motivation acquires an external character.

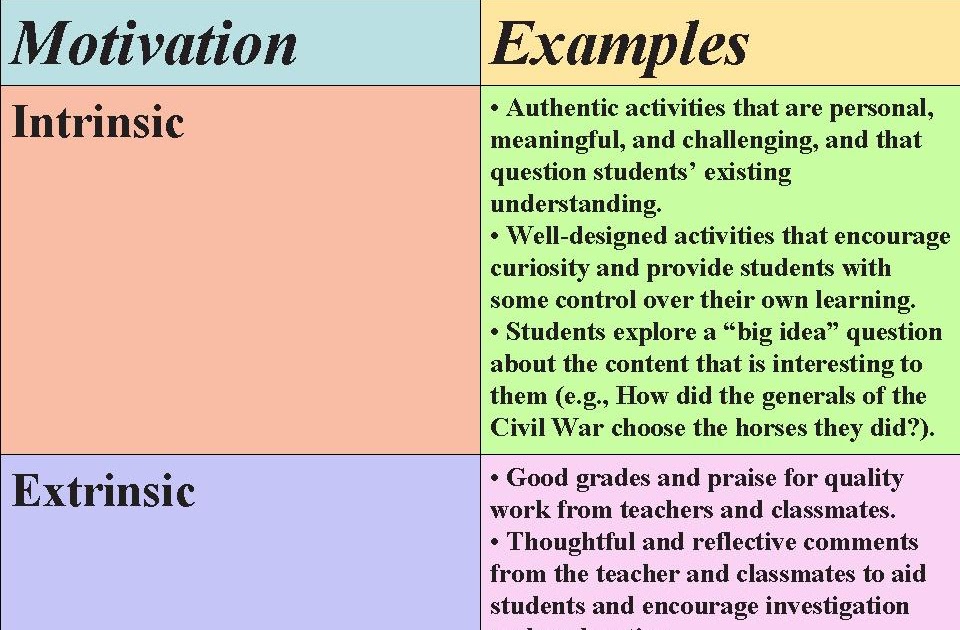

The student became more conscientious in doing all his homework after his parents promised to buy him a bicycle. Working on homework in this case is an externally motivated behavior, since the focus on lessons and intensity (in this case, conscientiousness) are set by a factor external to the study itself: the expectation of getting a bike. All the friends went to the sports section, and our student went. Going to the section for him is an externally motivated act, since his initiation and direction are completely under the control of his friends, i.e. outside the self of the student. Imagine a situation where friends stopped going to the section. Most likely, our outwardly motivated friend will also leave there. It is generally accepted that extrinsic motivation is primarily based on rewards, rewards, punishments, or other types of extrinsic stimulation that initiate and direct desirable behavior or inhibit undesirable behavior.

The most vivid conceptualization of this type of motivation is presented in behavioral theories [42], [70] and in instrumentality theories [6], [77].

Intrinsic motivation is a construct that describes this type of behavior determination, when the factors initiating and regulating it stem from within the personal Self and are completely within the behavior itself. “Intrinsically motivated activities have no rewards other than the activity itself. People engage in this activity for its own sake, not to achieve any external rewards. Such activity is an end in itself, and not a means to achieve some other end” [23; 23].

If a student comes home and enthusiastically says that there was a most interesting lesson at school and he wants to read the encyclopedia in order to participate in the discussion tomorrow, then he demonstrates an example of internally motivated behavior. In this case, the focus on the implementation of the lesson stems from the content of the lesson itself and is associated with interest and pleasure that accompany the process of learning and discovering something new. When all the friends run to enroll in the karate-do section because it has become fashionable (an example of external motivation), and our student goes to the city section because this is the only thing he is interested in, he again demonstrates internally motivated behavior.

When all the friends run to enroll in the karate-do section because it has become fashionable (an example of external motivation), and our student goes to the city section because this is the only thing he is interested in, he again demonstrates internally motivated behavior.

To explain this type of motivation, many theories have been created: the theory of competence and motivation by efficiency [78], [79], the theory of optimality of activation and stimulation [8], [17], the theory of personal causality [18], the theory of self-determination [28] , the “flow” theory [14], [15].

THEORIES OF EXTERNAL MOTIVATION

In behavioral theories, the main emphasis in the determination of behavior is on reinforcement - positive (rewards, encouragement) or negative (punishment) consequences that follow the performance of a certain behavioral act. Behavioral ideas have their origins in studies of operant conditioning by Edward L. Thorndike [73]. He discovered a pattern that later received his name and is known in psychology as the law of the Thorndike effect. This law states that the attractive and unattractive consequences of behavior affect the frequency of initiation of behavioral acts leading to these consequences. Behaviors that lead to positive consequences tend to persist and tend to be repeated, while behaviors that lead to negative consequences tend to stop. To explain the regulation of behavior, these ideas were used by C. Hull [42] and B.F. Skinner [70], [71]. The main feature of all variants of the behaviorist approach is the recognition that the main initiator and regulator of behavior is an external reinforcement in relation to it.

This law states that the attractive and unattractive consequences of behavior affect the frequency of initiation of behavioral acts leading to these consequences. Behaviors that lead to positive consequences tend to persist and tend to be repeated, while behaviors that lead to negative consequences tend to stop. To explain the regulation of behavior, these ideas were used by C. Hull [42] and B.F. Skinner [70], [71]. The main feature of all variants of the behaviorist approach is the recognition that the main initiator and regulator of behavior is an external reinforcement in relation to it.

The essence of the applied application of this model in pedagogy and in general in everyday practice lies in the systematic reinforcement of the desired behavior. At a school or at an enterprise, patterns of behavior are distinguished that are most appropriate from the point of view of a teacher or leader: high activity in the classroom, good discipline, or the absence of being late for work. When demonstrating this behavior, the student or employee is rewarded with special tokens, stars or pennants. With the accumulation of a certain number of awards of this kind, he can receive more significant prizes or incentives. A similar system exists in stores, when a customer who has made a certain number of purchases is given a reward that reinforces the behavior aimed at shopping in this particular store. It is important to note that all these systems are designed to reinforce initially uninteresting and unattractive behavior that a person will not perform of his own free will. Although they have shown their effectiveness, nevertheless, many researchers agree that a person turns out to be a puppet of reinforcements. Moreover, it has been observed that the desired behavior occurs only during the period of reinforcement (unless other motivational mechanisms come into play). No reinforcement, no motivated behavior.

When demonstrating this behavior, the student or employee is rewarded with special tokens, stars or pennants. With the accumulation of a certain number of awards of this kind, he can receive more significant prizes or incentives. A similar system exists in stores, when a customer who has made a certain number of purchases is given a reward that reinforces the behavior aimed at shopping in this particular store. It is important to note that all these systems are designed to reinforce initially uninteresting and unattractive behavior that a person will not perform of his own free will. Although they have shown their effectiveness, nevertheless, many researchers agree that a person turns out to be a puppet of reinforcements. Moreover, it has been observed that the desired behavior occurs only during the period of reinforcement (unless other motivational mechanisms come into play). No reinforcement, no motivated behavior.

Another version of theories of extrinsic motivation are theories of valence-expectation-instrumentality. This type of theories is built on two fundamental conditions of human behavior, which began to be studied in psychology after the works of K. Lewin [49]–[51] and E. Tolman [74], [75]. The first condition is as follows. In order to be motivated to a certain kind of behavior, a person must be sure that there is a direct relationship between the behavior carried out and its consequences. This subjective certainty is called “expectation! instrumentality". The second condition: the consequences of behavior must be emotionally significant for the individual, must have a certain value for her. This affective attraction is called "valence". The formula for motivated behavior in this case looks like this: behavior = valence x expectation. The product of two parameters means that if at least one of the factors is equal to zero, then the entire product will be equal to zero. If the consequences of behavior are insignificant for the individual, then she will not feel the intention to carry it out.

This type of theories is built on two fundamental conditions of human behavior, which began to be studied in psychology after the works of K. Lewin [49]–[51] and E. Tolman [74], [75]. The first condition is as follows. In order to be motivated to a certain kind of behavior, a person must be sure that there is a direct relationship between the behavior carried out and its consequences. This subjective certainty is called “expectation! instrumentality". The second condition: the consequences of behavior must be emotionally significant for the individual, must have a certain value for her. This affective attraction is called "valence". The formula for motivated behavior in this case looks like this: behavior = valence x expectation. The product of two parameters means that if at least one of the factors is equal to zero, then the entire product will be equal to zero. If the consequences of behavior are insignificant for the individual, then she will not feel the intention to carry it out. Also, if a person is sure that the behavior is in no way connected with its results, then there will be no motivation to perform. High motivation in accordance with this approach will be in the case when a person is sure that the desired consequences for him are a direct result of the behavior being undertaken. Within the framework of this paradigm, many well-known motivational theories have been created [6], [12], [77].

Also, if a person is sure that the behavior is in no way connected with its results, then there will be no motivation to perform. High motivation in accordance with this approach will be in the case when a person is sure that the desired consequences for him are a direct result of the behavior being undertaken. Within the framework of this paradigm, many well-known motivational theories have been created [6], [12], [77].

This group of theories is referred to as external, because the leading regulating factors of behavior are the valency of the consequences external to the behavior and the connection between the behavior and this consequence. When a worker assembles an assembly (behavior performed) on an assembly line (obtained result) and thus earns money for a living (attractive consequences), the motivation for this labor behavior is of a pronounced external character. Its initiation, intensity, and direction are directly related to the attractiveness of the consequences and the relationship between the behavior and these consequences. In itself, behavior has no value for a person in this case. It is valuable insofar as it serves as a reliable tool for achieving the desired consequences. Because of this, both in behavioral theories and in the theories of “valence x expectation”, behavior is considered as instrumental, performing the function of a means to obtain an attractive outcome, which is external to itself.

In itself, behavior has no value for a person in this case. It is valuable insofar as it serves as a reliable tool for achieving the desired consequences. Because of this, both in behavioral theories and in the theories of “valence x expectation”, behavior is considered as instrumental, performing the function of a means to obtain an attractive outcome, which is external to itself.

THEORIES OF INTERNAL MOTIVATION

The term "intrinsic motivation" was first introduced in 1950 [36]. By this time, the popularity of the behaviorist approach began to decline, primarily because, despite attempts to formulate universal laws of human behavior, many types of human activity did not fit into the explanatory schemes of behaviorism. At the end of the 50s. Two works appeared that seemed to sum up this dissatisfaction: the book by R. Woodworth [81] and the article by R. White [78].

In the book "Dynamics of Behavior", which was the development of ideas first set forth in 1918 [80], R. Woodworth proclaimed the principle of the primacy of behavior as opposed to the behaviorist principle of the primacy of drive (motivation). To paraphrase a well-known saying, this principle can be formulated as follows: "A person eats to carry out behavior, and does not carry out behavior in order to eat." A person, according to R. Woodworth, is born with an active tendency to master the world through behavior. Such behavior is understood as a constant flow of activity for effective interaction with the environment. Drive satisfaction interrupts this activity in order to provide the body with the energy it needs.

Woodworth proclaimed the principle of the primacy of behavior as opposed to the behaviorist principle of the primacy of drive (motivation). To paraphrase a well-known saying, this principle can be formulated as follows: "A person eats to carry out behavior, and does not carry out behavior in order to eat." A person, according to R. Woodworth, is born with an active tendency to master the world through behavior. Such behavior is understood as a constant flow of activity for effective interaction with the environment. Drive satisfaction interrupts this activity in order to provide the body with the energy it needs.

R. White, in his article “Motivation Revisited: The Concept of Competence,” proposed a conceptually more developed model on the same topic. He introduced the concept of "competence" (competence), which combines such types of behavior as palpation, inspection, manipulation, design, play, creativity. He believes that all these behaviors, in which the body does not receive any visible reinforcements, have one goal: increasing the competence and efficiency of a person.