What does it feel like to be dead

What does it feel like to die? | Death and dying

In March 2012, the Bolton Wanderers midfielder Fabrice Muamba collapsed on the field during a televised FA Cup match against Tottenham Hotspur. He had suffered a heart attack and was clinically dead, with no vital signs, for a considerable length of time. Remarkably, he survived, and has since described his impressions of what happened. At first, he said, he felt a surreal dizziness, as though he was running along inside someone else’s body. The last thing he remembers is seeing two of the Tottenham player Scott Parker. Interestingly, he reports no feeling of pain.

I can’t be the only person whose initial empathy for Muamba and his family was the starting point for a deeper reflection, above all concerning my future death. When will it come? (Hopefully, not for many years.) What will be its circumstances? (Peaceful, I hope.) And, very simply – what does it feel like to die?

In scientific literature, there are numerous reports of people who have had similar experiences to Muamba, many involving light. The oldest medical description of a near-death experience, from the 18th century, recounts the tale of a French apothecary who lost consciousness during blood-letting, a treatment believed by physicians at the time to relieve fever. He recalled “such a pure and extreme light that he thought he was in Heaven”. More recent recollections include seeing bright lights, sensations of entering an unearthly realm and occasionally the feeling of leaving the body and viewing it from above, known as an out-of-body experience.

Of course, we can’t tell how strange or unusual these memories actually are without knowing the number of people who survive clinical death without such recollections. In many cases, researchers were also asking people to recollect events that happened decades earlier, the details of which may have been changed, or lost in the mists of time. Then medical researcher Sam Parnia and his colleagues decided to take a more objective approach.

Fifteen years ago, Parnia’s team interviewed over a 12-month period 63 patients at Southampton General Hospital who were resuscitated following a heart attack. Of the 63, seven could recall thoughts from the time they were unconscious. They included coming to a point or border of no return, feelings of peace and, in one case, jumping off a mountain. So, while only a minority could remember being close to death, what could be recalled was generally positive.

Of the 63, seven could recall thoughts from the time they were unconscious. They included coming to a point or border of no return, feelings of peace and, in one case, jumping off a mountain. So, while only a minority could remember being close to death, what could be recalled was generally positive.

Surprisingly, the patients able to recall their experiences actually had the highest blood-oxygen levels – feelings such as heightened sensual awareness had previously been thought to result from brain-oxygen starvation. Yet better brain oxygenation would allow for improved cognitive function during the resuscitation, explaining more vivid experiences and the ability to commit them to memory.

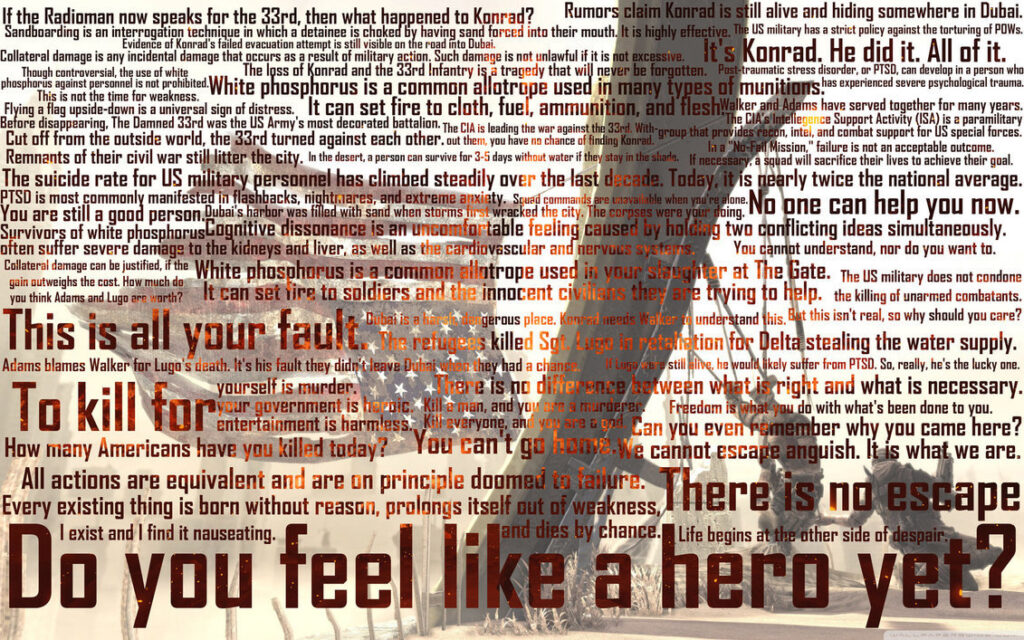

An image above a resuscitation table that patients are asked if they have seen after a near-death experience. Photograph: PRAs part of the experiment, suspended boards with painted writing and figures on their upper sides were hung from ceilings throughout the hospital. Any patients reporting an out-of-body experience could then reasonably be asked to describe what they saw on the upper sides of the boards. This would have been very troublesome for prevailing scientific understanding – certainly, a rethink of human consciousness as something entirely dependent upon the billions-strong network of neurons in our brains. These simple devices had the capability of turning conventional neuroscience on its head.

This would have been very troublesome for prevailing scientific understanding – certainly, a rethink of human consciousness as something entirely dependent upon the billions-strong network of neurons in our brains. These simple devices had the capability of turning conventional neuroscience on its head.

However, no out-of-body experiences occurred in this patient group, so this ingenious idea was not properly tested. But the researchers weren’t finished yet – and have just published a new study. This time, it encompassed 15 US and European hospitals, and, unlike the earlier research, two resuscitated patients did recollect vivid out-of-body experiences.

One became aware of a woman up in one corner of the room beckoning to him, and the next moment he was up there, looking down at himself. He recalled hearing a voice saying: “Shock the patient, shock the patient.” And he could see a nurse and a bald-headed man wearing blue scrubs that he described as “quite a chunky fella”. The other remembered being “on the ceiling looking down” and seeing a nurse pumping his chest while a doctor was “putting something down my throat”.

Unfortunately, neither patient underwent resuscitation in areas where boards were positioned. The researchers got closer this time, but once more the opportunity to verify or refute out-of-body experience was missed.

Nonetheless, while researchers couldn’t test it, they perhaps demonstrated something more important. The astronomer Edwin Hubble said: “Equipped with his five senses, man explores the universe around him and calls the adventure Science.” Scientific investigation is not all white coats, hi-tech gadgets and undecipherable equations, but rather its watchwords are fairness and objectivity. Some simple and elegant painted wooden boards illustrate this beautifully.

So, what does it feel like to die? As these studies record, death by cardiac arrest seems to feel either like nothing, or something pleasant and perhaps slightly mystical. The moments before death were not felt to be painful. We don’t know if this would extend to other causes of death, but still, it is reassuring. I take comfort from the notion that death is not necessarily something to be feared. Thanks to the stories of Fabrice Muamba, the patients of Southampton hospital and others, we can rest easier as we carry on our lives in death’s ever-present, if perhaps now slightly fainter, shadow.

I take comfort from the notion that death is not necessarily something to be feared. Thanks to the stories of Fabrice Muamba, the patients of Southampton hospital and others, we can rest easier as we carry on our lives in death’s ever-present, if perhaps now slightly fainter, shadow.

What is it Like to Die & How Does it Feel?

What is it like to die? That question has fascinated philosophers, religious leaders, and scientists alike for millennia.

WATCH BELOW: Surviving Death | Official Netflix Trailer

Death is scary because it’s a great unknown. After all, no one comes back from the dead to tell you what it’s like on the other side. But with the advent of improved medicine, a select few people have come back from the brink of death and lived to tell the tale.

So, if you want to satisfy your morbid curiosity about death, this might be the article you’ve been waiting to read.

Getty

What does it feel like to die?Based on the accounts of people who have experienced death and then were revived afterward, death has several feelings associated with it.

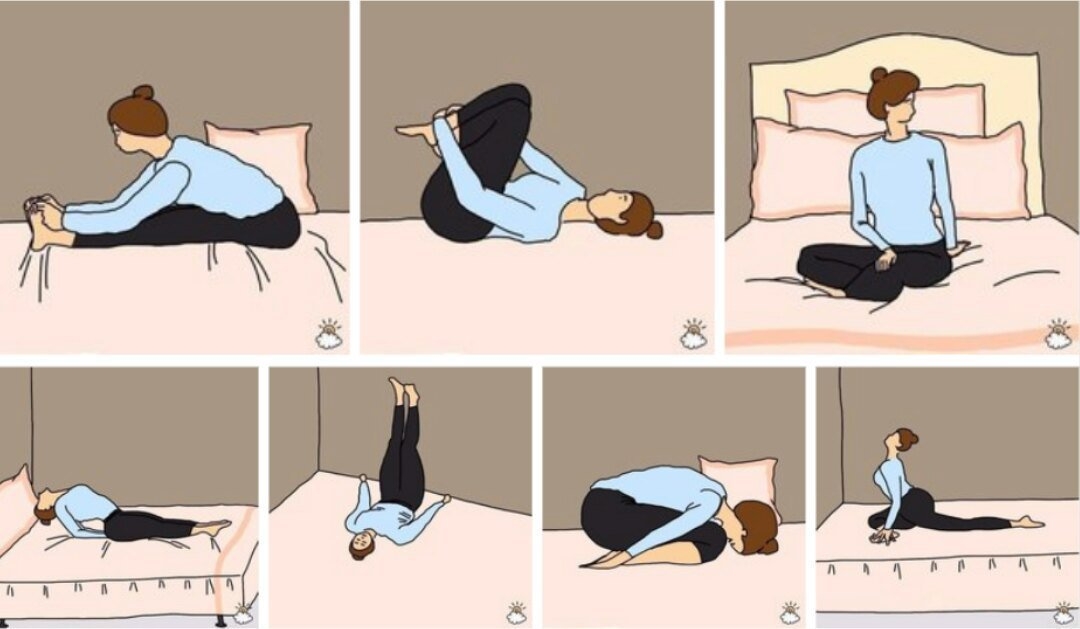

As you die, it may feel like you’re dreaming, and you may start losing your senses and natural urges such as hunger and thirst.

What is death?Death has had many meanings throughout the years across many cultures.

The ancient Egyptians believed that death was merely a temporary interruption in life rather than the total end of it, while the Greeks of Antiquity believed that the soul left the body during death in a puff of air.

Even the medical definition of death has changed over the years, with the goalposts moving further away as medical techniques improve.

In the 1600s, death occurred when someone stopped breathing. However, in 1952, an anaesthetist was able to mechanically ventilate a polio victim when they could no longer breathe on their own.

Then, in the 1800s, death became the moment someone's heart stopped beating. But in 1892, the first-ever instance of CPR was successfully performed, allowing a previously stopped heart to be restarted.

Today, clinical death can be described as the irreversible cessation of functions that are vital to life. This often follows after brain death, or irreversible damage to the brain that results in the loss of respiration and other autonomic functions. Clinical death is declared after all attempts to resuscitate a patient have failed.

What is the average life expectancy in Australia?According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, the average life expectancy in Australia is 80.9 years for men and 85.0 years for women, a figure that’s only increasing with time.

What are the most common causes of death?Across the world, the number one and two causes of death are ischaemic heart disease and stroke, which were responsible for 16 per cent and 11 per cent of the world’s total deaths respectively in 2019. Over the past two decades, these two diseases have kept their rank as the top two leading causes of death.

Over the past two decades, these two diseases have kept their rank as the top two leading causes of death.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lower respiratory conditions, neonatal conditions, and Alzheimer’s and other dementias are the next four most common causes of death. The top causes of death have changed a lot in the last four years, with road accidents being removed from the top ten.

In Australia, the top 5 leading causes of death are coronary heart disease, followed by the various kinds of dementia. In third place is cerebrovascular disease including stroke, then lung cancer, and finally chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. This was last updated in 2019.

What does death feel like at every stage?Every person experiences a different sequence of feelings when they die, but there are some common experiences among the people who’ve managed to come back from the dead.

Your senses and urges begin fadingDoes dying hurt? Interestingly, James Hallenbeck of Stanford University describes the first feelings of death as the loss of sensation. “First hunger and then thirst are lost. Speech is lost next, followed by vision. The last senses to go are usually hearing and touch.”

“First hunger and then thirst are lost. Speech is lost next, followed by vision. The last senses to go are usually hearing and touch.”

A study of 66 patients admitted to Hospice Buffalo, New York showed that many terminally ill people experience dreams or visions, especially about their deceased and living loved ones. As they inched ever closer to death, the dreams became even more vivid and frequent. It was almost as though they were headed to sleep, rather than towards death.

Getty

You might actually see a bright lightThe popular image of seeing a ‘bright light at the end of the tunnel’ may actually have an explanation in biology.

When your heart stops, your brain loses its supply of oxygen from the blood, while carbon dioxide starts to build up in your body. Increased levels of carbon dioxide can lead to stress responses and visual hallucinations, which may include flashing lights.

In fact, mountain climbers suffering from low-oxygen altitude sickness have reported seeing flashing lights as well.

Whether you think you’re coming home to God or descending into hell, the light may be nothing more than your brain’s final cries for air.

You may feel extremely calm and at peaceWhile dying might evoke a stress response, the act itself may be very peaceful.

“It turns out to be not so bad to have a dying experience, ” says Dr. Steven Laureys, who leads the Coma Science Group at the Université de Liège in Belgium. His study of people who have had near-death experiences shows that few people have negative experiences in the moments leading up to death, and most have in fact felt an “overwhelming feeling of peacefulness.”

Getty

A 2018 thread on reddit about people who have experienced clinical death revealed similar sentiments.

One redditor relayed the experience of his friend, describing it as “being surrounded by darkness and floating with some sort of warm gel-like substance covering her.![]() ” He added that she never wanted to leave.

” He added that she never wanted to leave.

Another redditor described the experience. “She said it was the most amazing feeling she’s ever experienced. It was blank black nothing, but that was perfectly fine, and she felt a comfort she can’t even explain. She remembers being angry at the man working on her when she finally came back to her body because she wanted to stay there.”

Yet another said, “Friend of mine described it as deeply relaxing and that she could feel herself drifting away, but was brought back just as she was ready to ‘leave’.”

WATCH BELOW: Grant Denyer speaks about his near death experience on I'm A Celebrity. Post continues after video...

While the notion of dying might seem terrifying, the actual experience of dying doesn’t feel so terrible. If you’re worried about death being a horrifying and painful experience, you can rest easy knowing that you’ll probably be at peace.

Now, whether there’s nothing after death, or an afterlife you can look forward to? That’s a question for another article.

Until it’s actually your time, you should do whatever it takes to stay fit and avoid those common causes of death we listed. Things that you’re not addressing, like snoring due to sleep apnea or a large potbelly, could lead to an early death by stroke or heart attack. Make sure that your life is healthy so that when the time comes, your end can be painless and peaceful!

Rhys McKay

Subscribe to Who magazine-& save!

Subscribe NowSubscribe to Who magazine-& save!

Subscribe NowWhat is it like to die? | 10/07/2022, InoSMI

The materials of InoSMI contain only assessments of foreign media and do not reflect the position of the editors of InoSMI

On December 9, 2013, doctors declared Jahi McMath brain dead. She breathed on a ventilator, but her pupils did not respond to light, and the electroencephalogram showed no brain wave activity. Thus began the ongoing ordeal of her mother Niyla to this day in fruitless attempts to prove that her daughter is alive and able to respond to external stimuli.

She breathed on a ventilator, but her pupils did not respond to light, and the electroencephalogram showed no brain wave activity. Thus began the ongoing ordeal of her mother Niyla to this day in fruitless attempts to prove that her daughter is alive and able to respond to external stimuli.

Shortly before her tonsillectomy, Jahi McMath, a thirteen-year-old African-American girl from Oakland, California, asked her doctor Frederick Rosen about his qualifications.

— How many times have you done this operation?

“Hundreds of times,” answered Rosen.

Did you sleep well last night?

“Yes, fine,” was the answer.

Jahi's mother Niyla Winkfield encouraged her daughter to keep asking questions. "It's your body," she said. “Do not be shy to ask this person about anything that interests you.”

Jahi begged her not to have this operation, but her mother said it would be better. Jahi suffered from sleep apnea, which made her very tired and unable to concentrate at school. She snored so loudly that she was ashamed to go to bachelorette parties. Nyla raised four children alone, and Jahi, the second oldest, was the most cautious of all. Seeing news on television about wars in other countries, she quietly asked: "War will come to us too?" Her classmates laughed at her plumpness, but she bore the insults silently. On several occasions, Naila personally asked the teachers to monitor the behavior of other students more carefully.

She snored so loudly that she was ashamed to go to bachelorette parties. Nyla raised four children alone, and Jahi, the second oldest, was the most cautious of all. Seeing news on television about wars in other countries, she quietly asked: "War will come to us too?" Her classmates laughed at her plumpness, but she bore the insults silently. On several occasions, Naila personally asked the teachers to monitor the behavior of other students more carefully.

The operation took place at Oakland Children's Hospital and took four hours. When Jahi woke up - around 7 p.m. on December 9, 2013 - the nurses gave her grape ice cream to relieve her sore throat. About an hour later, Jahi started spitting blood. The nurses told her not to worry and gave her a plastic bowl. One of them recorded asking Jahi to "relax and not cough as much as possible." By nine o'clock in the evening, the bandages covering the girl's nose were soaked with blood. Nyla's husband Marvin, a truck driver, repeatedly demanded the doctor's help. But the nurse said that only one family member at a time could enter the room. He agreed to leave.

But the nurse said that only one family member at a time could enter the room. He agreed to leave.

Home Depot worker Nyla said, "No one listened to us and I can't prove anything, but I feel like if Jahi was a white girl, we would get more help and attention." Crying, she called her mother Sandra Chatman, a nurse of thirty years who worked at the Kaiser Permanente Surgical Clinic in Oakland.

Sandra, a kind and calm woman who likes to wear a flower in her hair, arrived at the hospital at ten o'clock. Seeing Jahi fill a 200mm basin with blood, she told the nurse, “This is not normal. Do you really think this is the norm? In her notes, the nurse wrote that she notified the doctors on duty “several times per shift” that Jahi was bleeding. Another nurse wrote that the doctors "knew about this post-operative bleeding" but said that "immediate intervention by ENTs or surgeons is not required." Rosen has already gone home. In his medical records, he indicated that Jahi's right carotid artery was located abnormally close to the pharynx, a congenital condition with the potential to increase the risk of hemorrhage. But the nurses responsible for her recovery did not seem to know about this, and therefore did not mention it in their notes. (Rosen's lawyer said he couldn't talk about Jahi's condition; the hospital also couldn't comment on the medical privacy law, but the lawyer said staff were satisfied with Jahi's care.)

But the nurses responsible for her recovery did not seem to know about this, and therefore did not mention it in their notes. (Rosen's lawyer said he couldn't talk about Jahi's condition; the hospital also couldn't comment on the medical privacy law, but the lawyer said staff were satisfied with Jahi's care.)

The intensive care unit had twenty-three beds in three rooms. A doctor was standing at the other end of Jahi's room, and Sandra asked him: "Why don't you monitor my granddaughter's condition?" The doctor instructed the nurse on duty not to change Jahi's hospital gown in order to assess the amount of blood lost, and to splatter Afrin up her nose. Sandra, who teaches seminars at Kaiser Permanente on the "Four Habits Model," a method for improving the ability to empathize with patients, was, she says, surprised that the doctor never bothered to introduce himself. “He was frowning and crossing his arms over his chest,” she said. “It was as if he thought we were some kind of dirt. ”

”

At 12:30, Sandra saw on Jahi's monitor that her oxygen saturation had dropped to 79%. She called for help, several nurses and doctors came running and began to intubate the girl. Sandra heard one doctor say, "Damn, my heart stopped." It took two and a half hours for Jaha's heart to recover and her breathing to stabilize. Sandra said that the next morning Rosen looked like he was crying.

Two days later, doctors pronounced Jahi brain dead. She breathed with the help of a ventilator, but her pupils did not react to light, there was no gag reflex, and her eyes remained motionless despite the stimuli. She was briefly off the ventilator, but her lungs filled with carbon dioxide. The electroencephalogram did not record brain wave activity.

Like all other states, California lives by the 1981 version of the Uniform Death Act, which states that anyone subjected to "irreversible loss of all brain function, including the brain stem, is considered dead. " State law requires hospitals to give relatives some time to say goodbye before turning off the ventilator, but be mindful of the "needs of other patients and people in need of urgent care."

" State law requires hospitals to give relatives some time to say goodbye before turning off the ventilator, but be mindful of the "needs of other patients and people in need of urgent care."

At a meeting with Rosen and other medical workers, the family demanded an apology. According to a report by a social worker present at the meeting, Rosen "expressed sympathy", but this did not suit the girl's relatives. "Resign," Marvin urged him. “It was all fundamentally wrong!” And Sandra said Jahi didn't "get the treatment she deserved."

Over the next few days, the caseworker repeatedly urged Jahi's family to plan to take her off the ventilator. She also recommended that donation of her organs be considered. “We refused,” Marvin said. “Because they wanted to know what exactly happened to her first.” The family asked for Jahi's medical card, but since she was still in the hospital, the doctors could not do this. Niyla did not understand why Jahi was declared dead, because her skin remained warm and soft, and sometimes the girl moved her hands, feet and hips. Doctors called it nothing more than a spinal reflex, described in the medical literature as a "Lazarus symptom."

Doctors called it nothing more than a spinal reflex, described in the medical literature as a "Lazarus symptom."

An intensive care physician named Sharon Williams (African American) asked the hospital to give the family a little more time, adding that it would be against the family's interests to take Jahi off the ventilator so soon. A week later, Williams called Sandra to a female conversation. According to Sandra, the doctor told her that if Jahi was overexposed on the machine, she would not look very good at the funeral, "well, you know, like all of us." (Williams herself disagrees with this description of the conversation.)

“Who is ‘we’?” Sandra thought. "Are we African-Americans? I felt a terrible humiliation. Yes, a lot of black children die in Oakland, and people arrange funerals for them, but this does not mean that we are all the same. Do you think we should get used to that our children are dying, that it's okay for black people?" She said, "At that moment, I lost all confidence. "

"

Naila's younger brother, Omari Silei, slept in a chair next to Jahi's hospital bed to make sure no one would kill her. He said, "I just felt that her life is worth next to nothing in their eyes. It was as if they were trying to drive us away." that the hospital is urging them to take Jahi off the ventilator as soon as possible."They're trying to feed us legal bullshit," he wrote. "Only God decides when this ends." FUCK THIS HEALTH SYSTEM!!!” Another stated: "They want to see us either dead or in prison, as long as we are not alive."

A week after the operation, Seeley called personal injury attorney Christopher Dolan and told him, "They want to kill my niece." Dolan agreed to take this case on a pro bono basis, although he had no experience in such matters. He was guided only by a vague feeling that a child with a beating heart could not be considered completely dead. He wrote an order prohibiting the continuation of illegal actions: if the doctors disconnected Jahi from the ventilator, they would violate the civil rights of herself and her family. Seeley taped a note to Jahi's bed and pulse oximeter.

Seeley taped a note to Jahi's bed and pulse oximeter.

In his petition to the Alameda County Superior Court, Dolan asked for an independent physician to examine Jahi. He wrote about the hospital's conflict of interest because if its doctors are found guilty of malpractice, they could "drastically reduce their liability by terminating Jahi's life." For wrongful death, California will charge $250,000 for pain and suffering. But there are no restrictions on the amount that can be sued when the patient is still alive. In a separate motion, Dolan argued that the hospital violated Nailah's right to express his religious beliefs. As a Christian, she believed that her daughter's soul would be in her body for as long as her heart was beating.

On December 19, ten days after the operation, David Duran, SVP and Chief Medical Officer of the hospital, met with the family. They asked to leave Jahi on a ventilator until Christmas, hoping for a reduction in the brain tumor. Duran refused. They also asked to provide her with an artificial feeding probe. Duran turned down that request as well. He later wrote that the very idea that the procedure would help the girl recover was "completely absurd" and would only support "the illusion that she is still alive."

Duran refused. They also asked to provide her with an artificial feeding probe. Duran turned down that request as well. He later wrote that the very idea that the procedure would help the girl recover was "completely absurd" and would only support "the illusion that she is still alive."

When they persisted, Duran asked, "What don't you understand?" According to his mother, stepfather, grandmother, brother Jahi, and Dolan taking notes, Duran pounded his fist on the table, saying, "She's dead, dead, dead!" (The head physician himself denies these allegations.)

Three days before Christmas, a group of Oakland church leaders gathered outside the hospital and asked the district attorney to investigate what happened to Jahi. "Isn't Jahi worthy of proper medical care?" asked Brian Woodson Sr., the pastor of one of the local Christian churches, at a press conference.

The next day, Evelio Grillo, Judge of the Alameda County Superior Court, assigned independent expert Paul Fisher, head of neurology at Stanford University Children's Hospital, to examine Jahi. During the hearing, two hundred people marched in front of the hospital holding banners that read "Justice for Jahi!" and "Doctors can be wrong!" About a quarter of the protesters were friends and neighbors of Naila. She lived within walking distance of her mother, who lived a few blocks from her own, who had moved to East Oakland from Opelousas, Louisiana, at the height of the civil rights movement.

During the hearing, two hundred people marched in front of the hospital holding banners that read "Justice for Jahi!" and "Doctors can be wrong!" About a quarter of the protesters were friends and neighbors of Naila. She lived within walking distance of her mother, who lived a few blocks from her own, who had moved to East Oakland from Opelousas, Louisiana, at the height of the civil rights movement.

Fischer repeated the standard examination and tests for brain death and confirmed the hospital's report. He also conducted a radionuclide study of cerebral blood flow. “Only absolute emptiness is visible, a white spot in that part of the head where the brain is,” he told Judge Grillo the next day. “Usually this place is black.” Grillo ruled that the hospital could take Jahi off the ventilator after six days.

The family set up a GoFundMe page to raise funds to transfer Jahi to another hospital (“We acknowledge that the game is not going in our favor,” Niyla wrote), and received over fifty thousand dollars from complete strangers who found out about this case from the media. Terri Schiavo Life & Hope, an organization founded by Terri Schiavo's parents and brothers that had been in a vegetative state for fifteen years, offered to use their contacts to find a suitable clinic. Naila never thought about the issue of the right to life. When it came to abortion, she was a pro-choice. "I just wanted to get her out of there." And Sandra said she sometimes wonders, “Would we have to fight as hard as we had if the hospital had shown more compassion?”

Terri Schiavo Life & Hope, an organization founded by Terri Schiavo's parents and brothers that had been in a vegetative state for fifteen years, offered to use their contacts to find a suitable clinic. Naila never thought about the issue of the right to life. When it came to abortion, she was a pro-choice. "I just wanted to get her out of there." And Sandra said she sometimes wonders, “Would we have to fight as hard as we had if the hospital had shown more compassion?”

Nyla asked the Children's Hospital to perform a tracheotomy, an operation that allows air from a ventilator to be pumped directly into a breathing tube, a safer way for Jahi to breathe when transported to the new hospital. The hospital's medical ethics committee unanimously concluded that any intervention was inappropriate. “None of the possible goals of medicine—preserving life, curing disease, restoring function, alleviating suffering—can be achieved by ventilating the lungs and artificially supporting the dead patient,” they wrote. They said the doctors and nurses caring for Jahi were experiencing "tremendous mental anguish" and that granting the family's requests would raise "serious questions of fairness and fairness."

They said the doctors and nurses caring for Jahi were experiencing "tremendous mental anguish" and that granting the family's requests would raise "serious questions of fairness and fairness."

Shortly before the expiration of the protective order, Grillo extended it by eight days. Shortly thereafter, Dolan and the hospital's hospital lawyers reached the following agreement: the hospital would hand over Jahi to the Alameda County Coroner, who would declare her dead. The family would then bear "full and exclusive responsibility" for her.

On January 3, 2014, Jahi's death certificate was issued by the coroner. In the "cause of death" column, he wrote "investigation pending."

Two days later, two nurses from the air evacuation service entered Jahi's room. A doctor from a children's hospital disconnected her from the ventilator, and the nurses connected her to a portable device and put her on a gurney. They took her to an unmarked ambulance parked at the back entrance of the hospital. There was a game between the San Francisco 49ers and the Green Bay Packers that day, and Dolan hoped that this would distract the crowd of journalists who were near the hospital. Dolan didn't tell anyone where Jahi was going—not even her family—because he was afraid the hospital would find out and thwart the plan.

There was a game between the San Francisco 49ers and the Green Bay Packers that day, and Dolan hoped that this would distract the crowd of journalists who were near the hospital. Dolan didn't tell anyone where Jahi was going—not even her family—because he was afraid the hospital would find out and thwart the plan.

Niyla was the only family member allowed to board the plane hired with funds raised through GoFundMe. She was horrified by the noise her daughter's portable respirator made, seemingly drowning out the plane's engine. It wasn’t until she landed that she learned they were in New Jersey, one of two states—New York being the other—where families have the right to disagree with brain-death claims if it conflicts with their religious beliefs. In both states, the relevant laws were prescribed for Orthodox Jews, some of whom, referring to the Talmud, believe that the presence of breath is equivalent to life.

Jahi was sent to St. Peter's University Hospital in New Brunswick, New Jersey, which is administered by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Metachen. Nyla said that she "had no plan, no housing - nothing." She only had one suitcase with her. “When it comes to my child, I turn into an animal,” she told me.

Nyla said that she "had no plan, no housing - nothing." She only had one suitcase with her. “When it comes to my child, I turn into an animal,” she told me.

The Children's Hospital hired Sam Singer, an expert in reputational defense in crisis situations, to work with the media covering the case. “The atmosphere inside the hospital was like a state of siege,” Singer shared. Two days after his departure, Jahi Singer (who is described as "the best possible specialist") gave an interview to a local newspaper: "I have never seen such a reckless disregard for the truth." At a press conference, he said that Dolan "created a fake. A very sad fake. That Jahi McMath is somehow alive. This is not true. She died according to all the laws of the State of California. And every spiritual belief system imaginable will recognize that.”

Bioethicists treated the family's decision with equal disdain. In one of his articles for Newsday, Arthur Kaplan, founding director of NYU's Department of Medical Ethics and perhaps the nation's most famous bioethicist, wrote, "Keeping her alive on a ventilator is a desecration of the body. " In an interview with CNN, he stated that "there is no chance that in this state she will be able to last long." Answering questions from USA Today, he said: “well, you can’t feed the corpse,” and “it will begin to decompose.” Lawrence McCullough, a professor of medical ethics at Cornell University, believed that no hospital should accept Jahi. “What are they even thinking about?” he told USA Today. “There is only one appropriate description for all of this: insanity.”

" In an interview with CNN, he stated that "there is no chance that in this state she will be able to last long." Answering questions from USA Today, he said: “well, you can’t feed the corpse,” and “it will begin to decompose.” Lawrence McCullough, a professor of medical ethics at Cornell University, believed that no hospital should accept Jahi. “What are they even thinking about?” he told USA Today. “There is only one appropriate description for all of this: insanity.”

Director of the Center for Bioethics at Harvard Medical School, Robert Truog, said he was concerned about the way the media reported the incident. “I think members of the bioethics community felt such a strong need to support the traditional understanding of brain death that they actually treated the family with contempt, which made me feel terrible,” he told me. Truogh believed that the social context of the family's decision had been ignored. African Americans are twice as likely as whites to ask to have their lives extended as long as possible, even in cases of irreversible coma—probably due to fear of neglect. A vast body of research has shown that black patients are less likely to receive appropriate medications and surgeries than white patients, regardless of insurance or educational level, and are more likely to undergo unwanted medical interventions such as amputations. Truogh said: “I understand that when a doctor says that your loved one has died, but he does not look dead, it may seem that you are again denied proper care because of the color of your skin.”

A vast body of research has shown that black patients are less likely to receive appropriate medications and surgeries than white patients, regardless of insurance or educational level, and are more likely to undergo unwanted medical interventions such as amputations. Truogh said: “I understand that when a doctor says that your loved one has died, but he does not look dead, it may seem that you are again denied proper care because of the color of your skin.”

Until the 1960s, the only possible cause of death was cardiorespiratory failure. The notion that death could be diagnosed in the brain only arose with the advent of modern ventilators, which performed the manipulation known at the time as “oxygen therapy”: as long as the oxygen-carrying blood reached the heart, it could continue to beat. In 1967, Henry Beecher, a noted bioethicist at Harvard Medical School, wrote to one of his colleagues: "It would be very desirable if Harvard University came to some conclusion about a new definition of death. " There has been a rise in the number of “coma patients supported on ventilators across the land, and there are a number of issues that need to be addressed.”

" There has been a rise in the number of “coma patients supported on ventilators across the land, and there are a number of issues that need to be addressed.”

Beecher set up a committee of ten physicians, a lawyer, a historian, and a theologian. In less than six months, they completed the report, which they published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The only quote in the article was from the Pope. They put forward the proposal that death should be considered irreversible processes of brain destruction, motivated by the following reasons: in order to alleviate the burden of families and hospitals that provide meaningless care for hopeless patients, and to accept the fact that "outdated criteria for determining death can lead to disagreements on the issues of organ harvesting for transplantation”; in the previous five years, doctors performed the world's first transplantation of the pancreas, liver, lungs, and heart. In an earlier version of the report, the second reason was more specific: "There is a great need for tissues and organs of hopeless patients in a state of coma in order to restore the health of those who can still be saved. " (The proposal was revisited after the dean of Harvard Medical School said it was an unfortunate connotation.)

" (The proposal was revisited after the dean of Harvard Medical School said it was an unfortunate connotation.)

Over the next twelve years, 27 states redefined the definition of death to match the findings of the Harvard Committee. Thousands of lives were extended or saved each year, as patients who were declared brain dead—a form of death eventually adopted by the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and most of Europe—could now donate their organs to others. Philosopher Peter Singer called it "a concept so desirable in its implications that it is impossible to abandon it, and so shaky in its justifications that it is almost impossible to support it." The new death was "an ethical choice disguised as a medical fact," he wrote.

Legal ambiguity persisted—people thought to be alive in one region could be declared dead in another—and in 1981 the Presidential Commission on Ethical Issues proposed a unified definition and theory of death. Her report, which was approved by the American Medical Association, said that death is the point at which the body ceases to function as a "whole. " Even if life is preserved in individual organs and cells, a person can no longer be considered alive, since in this case, functioning organs are nothing more than a set of artificially maintained subsystems doomed to destruction. “Usually, the heart stops beating between two and ten days,” the report said.

" Even if life is preserved in individual organs and cells, a person can no longer be considered alive, since in this case, functioning organs are nothing more than a set of artificially maintained subsystems doomed to destruction. “Usually, the heart stops beating between two and ten days,” the report said.

Commission staff philosopher Daniel Wikler, a professor at Harvard University and the first corporate ethicist at the World Health Organization, told me that the commission's theory of death was supported by the scientific evidence it cited. “It seemed to me that this was a clear lie, but so what?” he said. “At that time, I didn’t see a single negative point.” Wikler told the commission that it would be more logical to say that death occurs at the moment of cessation of the functioning of the large brain, that is, the center of consciousness, thoughts and feelings - properties necessary for having a personal identity. His wording would "kill" even more patients, including those who were able to breathe on their own.

Despite Wickler's remarks, he prepared the third chapter of the report, "understanding the meaning of death." “I was put in a difficult position, and I did the work in bad faith,” he told me. I knew it all smacked of treachery, and I created the appearance of many unknowns and went down the path of vague facts, so that no one could say: "Hey, your philosopher thinks this is nonsense." That's exactly what I thought, but in what you wrote you will never see anything like it.”

Continuation of the material Read the Inosmi on Sunday April 15, 2018.

Seven shades of death: What does a person feel when

- Rachel Newver

- BBC Future

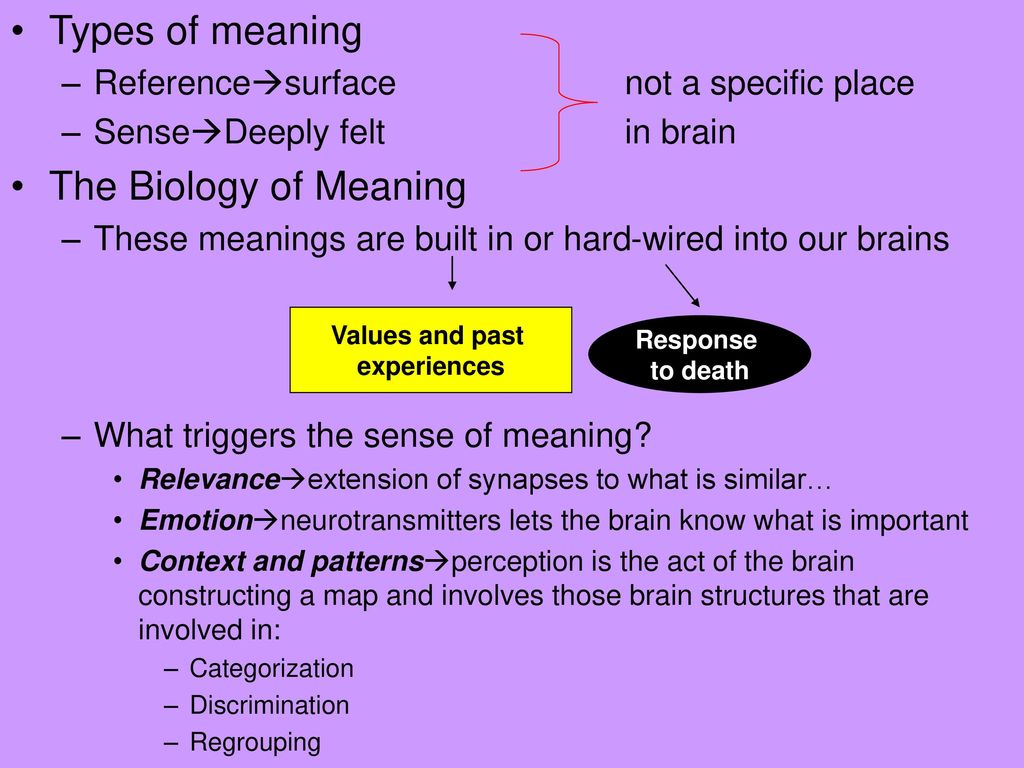

- Fear

- Images of animals or plants

- Bright light

- Violence and persecution

- dejaugu 90 90

- Persons of family members of 90AL

9 Lipnya 2015

9 - a popular idea of how we feel the transition to another world. But as BBC Future correspondent Rachel Nieuwer says, the experiences of near-death survivors are much more varied.

In 2011, a 57-year-old social worker from England - let's call him Mr A. - was taken to Southampton Central Hospital after he passed out on the job. While doctors were trying to insert a catheter into the patient, his heart stopped. Without access to oxygen, the brain instantly ceased to function. Mr A. has died.

- was taken to Southampton Central Hospital after he passed out on the job. While doctors were trying to insert a catheter into the patient, his heart stopped. Without access to oxygen, the brain instantly ceased to function. Mr A. has died.

Despite this, he remembers what happened next. Medics took an automated external defibrillator (AED), a machine that activates the heart with an electric shock. Mr. A. heard a mechanical voice repeat twice: "Discharge." Between these two commands, he opened his eyes and saw a strange woman in the corner under the ceiling, who beckoned him with her hand.

Image copyright, Thinkstock

Image caption,The light at the end of the tunnel is just one of many death scenarios

"She seemed to know me, I felt trust in her, I thought she was there for a reason, but I didn't know which one," Mr. A later recalled. "The next second I was upstairs, looking down at myself, the nurse, and some bald man. "

"

Researchers believe that it is quite possible to collect objective scientific data on potentially last moments of life. Over the course of four years, they analyzed more than 2,000 patients who survived cardiac arrest, that is, official clinical death.

Image copyright, Thinkstock

Image caption,It felt like I was being pulled deep underwater

Of this group of patients, doctors were able to revive 16%. Dr. Parnia and his colleagues interviewed a third of these patients - 101 people. “Our goal is to understand first of all what people feel at the time of death,” says Dr. Parnia. “And then to prove that what patients say they see and hear at the time of death is indeed an awareness of reality.”

Seven Shades of Death

Mr. A is not the only patient who had memories of his death. Nearly 50% of study participants could remember something. But unlike Mr. A and another woman, whose account of being out of her own body cannot be objectively proven, the experiences of the other patients did not seem to be tied to the actual events that took place at the time of their death.

Their stories were more like dreams or hallucinations, which Dr. Parnia and his colleagues divided into seven main scenarios. "Most of them didn't fit with what used to be called 'near-death' experiences," says Parnia. "It appears that the psychological experience of death is much broader than we imagined in the past."

These seven scenarios include:

Skip the podcast and continue

podcast

What was it

The main story of the day, how our journalists explain

Issues

End podcast

Mental experiences of patients range from terrible to blissful. Some patients report feelings of overwhelming terror or persecution. For example, like this. “I had to go through a burning ceremony,” recalls one participant in the study. “There were four people with me, and if one of them lied, he had to die ... I saw people in coffins who were buried in an upright position.”

Some patients report feelings of overwhelming terror or persecution. For example, like this. “I had to go through a burning ceremony,” recalls one participant in the study. “There were four people with me, and if one of them lied, he had to die ... I saw people in coffins who were buried in an upright position.”

Another person recalls being "dragged deep underwater" and another patient says that "I was told I was going to die and the quickest way to do that was to say the last little word I don't remember."

However, other respondents report rather opposite feelings. 22% recall "feeling of peace and tranquility." Some saw living creatures: "Everything and everything around, in plants, but not flowers" or "lions and tigers." Others bathed in "bright light" or reunited with family. Some had a strong sense of déjà vu: "I felt like I knew exactly what people were going to do and they really did." Heightened senses, a distorted sense of time, and a feeling of separation from one's own body are common memories of near-death patients.

Image copyright, Thinkstock

Photo caption,Some patients felt that they were separated from their own body

While "certainly people felt something at the time of death," Prof. Parnia says, how they will interpret these experiences, completely dependent on their experience of life and beliefs. Hindus may have said they saw Krishna, while a Midwesterner in the United States claimed to have seen God. “If a person who is brought up in Western society is told that when you die, you will see Jesus Christ, and he will be full of love and compassion, then he will certainly see him,” says the professor. “She will return and say:“ Father, you are right, I really saw Jesus!" But how can any of us recognize Jesus or another God? You do not know what God is. I do not know what he is. Except for the images of a man with a white beard, although everyone understands that it's a fabulous show."

"All this talk about the soul, heaven and hell - I have no idea what they mean. There are probably thousands of interpretations, depending on where you were born and how you were raised," says the scientist. "It is important to move these memories from realm of religion into the plane of reality".

There are probably thousands of interpretations, depending on where you were born and how you were raised," says the scientist. "It is important to move these memories from realm of religion into the plane of reality".

Ordinary cases

So far, the team of scientists has not determined what will affect the ability of patients to remember their feelings at the time of death. Explanations are also lacking as to why some people experience scary scenarios while others talk about euphoria. Dr. Parnia also notes that apparently more people have near-death memories than the statistics suggest. Most people lose these memories due to massive cerebral edema caused by cardiac arrest or heavy sedatives given to them in intensive care.

Even if people cannot remember their thoughts and feelings at the time of death, this experience will undoubtedly affect them on a subconscious level. The scientist suggests that this explains the very opposite reaction of patients who came back to life after cardiac arrest.