Psychology of rewards

Why Do Incentives Work? The Psychology of Motivation & Rewards

What is an incentive? Anything that motivates a person to perform an action can be considered an incentive. Incentives for eating food include delicious taste and necessary nutrients, for example. An incentive could be an outside reward someone offers you for completing a task (a $5 gift card for submitting a survey), or the reward inherent in doing something (the feeling you get after you volunteer your time at a local shelter). In this blog, I’ll namely be covering the first kind of reward, an outside reward, particularly as a tool in workplaces and customer loyalty. Digging into the question “Why do incentives work?” is fascinating. Understanding how and why incentives work can help you improve employee motivation, customer loyalty, and channel partner relationship strategies.

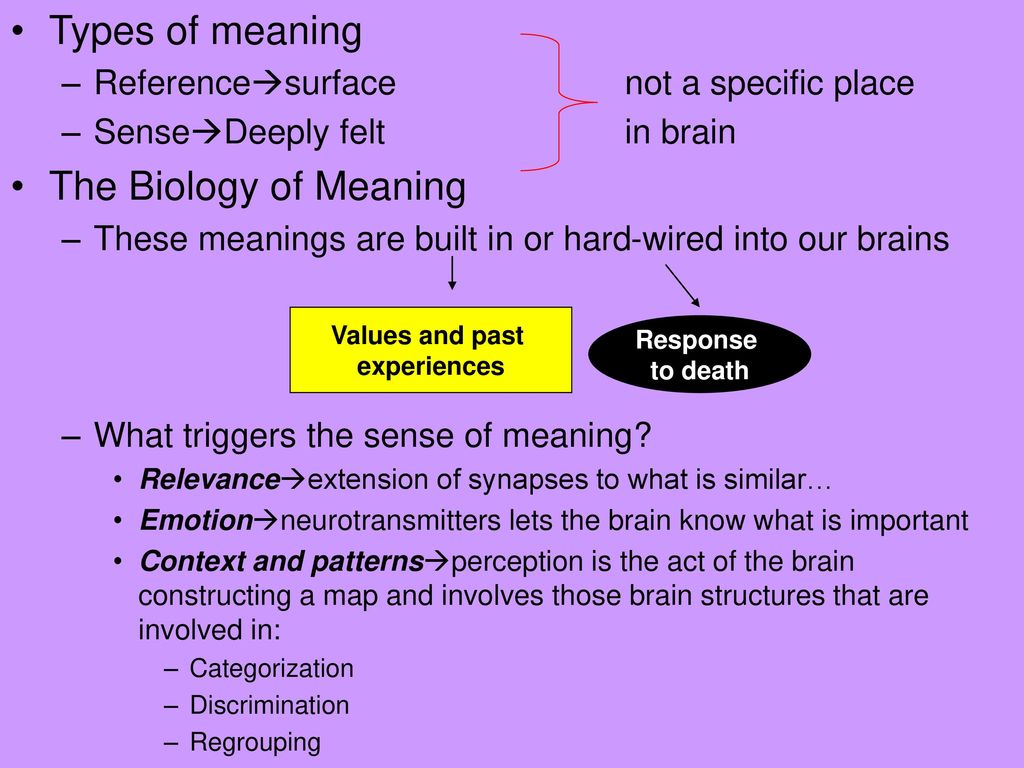

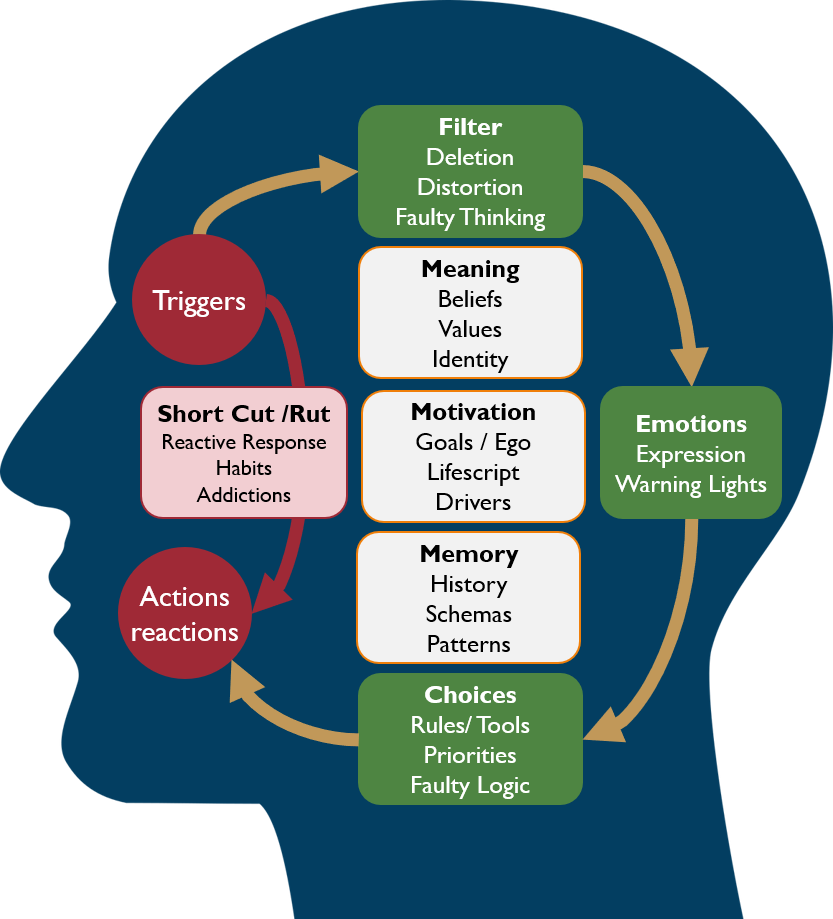

How Does the Brain React to Rewards?

The study of rewards and motivation is often said to have begun with psychologist B.F. Skinner’s research on operant conditioning in the 1930s. Skinner conducted various experiments on animals performing simple tasks such as pulling levers in exchange for rewards (namely food treats).

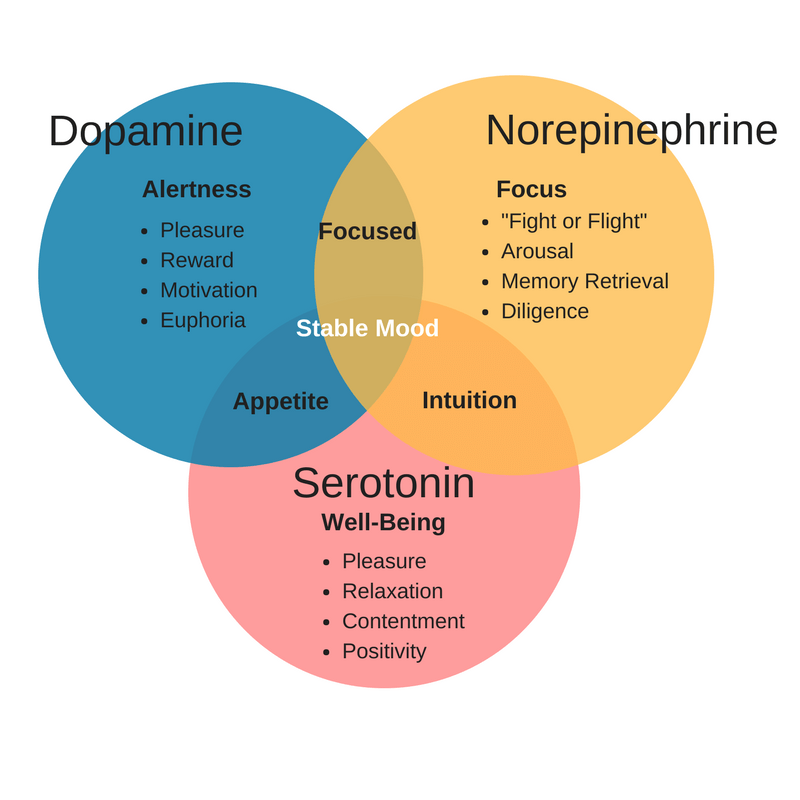

Humans are just a bit more complicated than mice, of course. Various studies since Skinner’s have revealed complex findings about humans and how our brains respond to rewards. Most importantly, scientists have a foundational explanation for why rewards work. That answer? A chemical in the brain called dopamine.

What Is Dopamine and When Is It Released?

As neuroscience professor Robert Saplosky discusses in his book Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, dopamine is the pleasure chemical released in our brains in response to enjoyable experiences, i.e. happy juice. Sex, music, and food all trigger dopamine responses in the brain. The brain also releases different amounts of dopamine depending on the circumstances. As Saplosky explains,

“Show a picture of a milkshake to someone after they’ve consumed one, and there’s rarely dopaminergic activation—there’s satiation.

But with subjects who have been dieting, there’s further activation.”

In other words, the happy juice in our brains tells us that something we don’t have is more enjoyable than something we just experienced.

There’s a downside to the brain’s reward system: it will only offer so much dopamine for the same stimulus. Saplosky colorfully describes an experiment in which “A monkey has learned that when he presses a lever ten times, he gets a raisin as a reward. That’s just happened, and as a result, ten units of dopamine are released…Now—surprise!—the monkey presses the lever ten times and gets two raisins. Whoa: twenty units of dopamine are released. And as the monkey continues to get paychecks of two raisins, the size of the dopamine response returns to ten units. Now reward the monkey with only a single raisin, and dopamine levels decline.”

This offers us our first clue in using incentives and rewards to motivate others in a workplace or sales context: the same reward offered over and over will become less effective

.

As you can see with the milkshake and raisin examples, the relationship between dopamine and rewards is already getting a bit complicated. We can’t just blindly hand out rewards and trust the fact that dopamine will do the rest of the work to motivate people. This is why you need a reward strategy to go along with your rewards.

How Do You Develop an Effective Reward Strategy?

A reward strategy (or incentive strategy) is a system of rewarding employees, customers, or channel partners for specific actions. Some companies may take an ad hoc approach to their reward strategy, but rewards are more effective if distributed as part of a formal rewards program.

Like any marketing or sales strategy, a reward strategy can get very granular and detailed. You should consider specific goals, budget, your target audience, and how you’re going to measure results or return on investment (ROI). For the purposes of this blog, let’s focus more broadly on some key psychological factors you should incorporate in your reward strategy.

Present with a show of recognition – but not too much.

Along with perceived desirability and repetition of rewards, the way a reward is presented also determines how effective the reward will be. The Incentive Research Foundation conducted an experiment to learn more about the impact of reward presentation. They compared participants’ responses to these four hypothetical reward presentation scenarios:

- “Big Show” – the CEO delivering the reward to the participant in front of the entire company

- “Little Show” – the participant’s manager delivering the reward, involving only their work group

- “Peer-to-Peer” – co-workers presenting the reward with only the work group in attendance

- “Private” – the CEO delivering the reward in private, along with a personal note

Rather than collecting the participants’ stated preference among these scenarios, neuroscientists measured their biometric response to each one. This included measuring pupil dilation and whether or not the participant responds more strongly to getting something they desire (behavioral approach system or BAS) versus avoiding something they don’t want (behavioral inhibitive system or BIS).

The results? “Little Show” was the scenario preferred by most participants, which included sales and non-sales individuals, as well as a mix of gender and age. The “Private” scenario was the least popular choice. Other interesting observations included the fact that Millennials showed more preference for “Peer-to-Peer” recognition, and women preferred “Peer-to-Peer” while men preferred “Big Show” and “Little Show.”

These findings offer some guidance on how to present rewards to your audience. Of course, not every group is the same, so you might need to conduct some research on the preferences of those you want to motivate and reward.

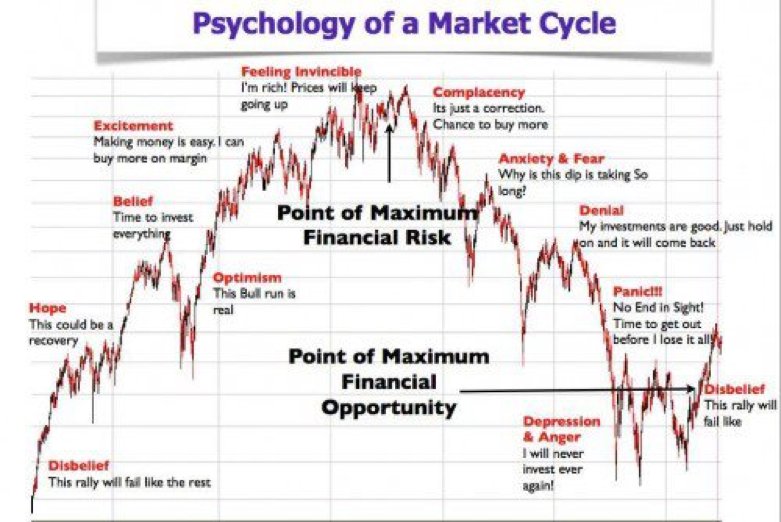

Build up anticipation and watch out for expectations.

Remember that experiment Saplosky described earlier, with the monkey pressing the lever? It turns out that, although dopamine release decreases from the act of pressing the lever, there is something else that happens after the experiment has been repeated enough times: the light that comes on, signaling the beginning of the reward trial, triggers a large dopamine release. In other words, once someone fully processes the rules and circumstances of a reward, the anticipation of a reward can be more rewarding than the reward itself.

In other words, once someone fully processes the rules and circumstances of a reward, the anticipation of a reward can be more rewarding than the reward itself.

Not only can reward recipients begin experiencing pleasure from anticipation leading up to a reward, but anticipation and expectation play a role in how much dopamine the brain releases. This is similar to how the things we don’t have (for example, a milkshake when we’re sticking to our keto diet hardcore) trigger more dopamine than things we just experienced. Except, in this instance, the larger dopamine release comes from unexpected rewards. As Saplosky explains,

“Following a reward, the dopamine system codes for discrepancy from expectation—get what you expected, and there’s a steady-state dribble of dopamine. Get more reward and/or get it sooner than expected, and there’s a big burst; less and/or later, a decrease.”

The lesson here is this: variances in reward types, reward amounts, and timing of rewards can all help make rewards more exciting and motivating. Making changes to the typical reward system (for example, offer pre-season rebates on air conditioners if you typically made the offer during summer) can make the same old reward suddenly much more appealing and effective.

Making changes to the typical reward system (for example, offer pre-season rebates on air conditioners if you typically made the offer during summer) can make the same old reward suddenly much more appealing and effective.

Utilize the Endowed Progress Effect.

The Endowed Progress Effect is a psychological phenomenon where people are more motivated to work toward a goal if progress toward the goal has already started. The effect was studied and defined by marketing professors Xavier Drèze and Joseph Nunes.

In their paper, “The Endowed Progress Effect: How Artificial Advancement Increases Effort,” Drèze and Nunes observed customers’ response to loyalty cards that offered a free car wash after ten purchases, proven by stamps on the card. Some were given cards that had two spaces already stamped as part of a “special promotion that day.” Others were given a card with eight spaces, but none stamped. The redemption rate for those who had the card endowed with two stamps was 34% , compared to a 19% redemption rate for those with the unstamped, eight-space card.

Even though customers had to make the same amount of purchases for all cards they received, those with the stamped card were motivated by the Endowed Progress Effect.

When you develop a reward strategy, you can incorporate the effect to boost engagement and participation in your program. As a caution: don’t overuse the Endowed Progress Effect or offer it without reason. As Drèze and Nunes noted in their paper, “When no reason is provided, we expect more people to perceive the endowed progress as a marketing ploy designed to lure people into enrolling in a loyalty program.”

Offer the right rewards.

So, you know that rewards will trigger happy juice, which will motivate reward recipients to perform an action. You know that psychological phenomena such as anticipation, expectation, and the Endowed Progress Effect can boost the impact of a reward. But which reward should you offer? Well, different rewards have different effects. Some are more effective in certain scenarios than others. Let me explain what I mean by looking at the three most common rewards offered in incentive and loyalty programs.

Let me explain what I mean by looking at the three most common rewards offered in incentive and loyalty programs.

What’s the reward?

When should you use them?

Why do they work?

Reward points (can be redeemed for merchandise in an online rewards catalog).

- For long-term customer loyalty and employee engagement strategies.

- For diverse reward audiences.

Everyone can choose the reward they want most, whether they prefer redeeming for big items or low-hanging fruit like movie tickets.

Debit or gift cards (virtual or physical, and can be spent in nearly any online or brick-and-mortar store; or gift cards to various stores and brands)

- As sales performance incentive funds (SPIFFS) for short-term sales promotions.

- For international reward audiences.

Everyone knows how to use cards, so there’s no learning curve. Debit and gift cards are widely versatile, so the turnaround redemption tends to be short.

Travel opportunities (group travel events, hotel stays, plane tickets, cruises, etc.)

- For top-performing sales reps or employees, as well as most valuable clients or customers.

- As a reward for achieving major milestones or goals.

Incentive travel historically has the highest return on investment (ROI) of any reward. It can also lead to long-lasting memories that build lifetime relationships and loyalty.

Why not cash?

Why isn’t cash featured in the reward options above? Cash is generally considered a less motivating and less cost-effective reward than tangible or experience rewards. Studies show that people often work harder for non-cash rewards even when they express a preference for cash. Additionally, participants tend to mentally lump cash rewards in with salary, creating a feeling of expectation and resulting disappointment when the reward isn’t earned.

To Wrap Up…

Rewards and the way humans respond to them can get complicated. Not only must you avoid making rewards feel like a manipulative bribe to start with, you also should avoid overusing the same reward or presenting the reward in a way that makes the recipient uncomfortable. But there are always ways to make rewards even more exciting. There are dozens of ways you can put a new spin on tactics such as the Endowed Progress Effect or anticipation build-up. Get creative and have fun with your reward strategy—that’s the best way to make it as effective as possible.

Not only must you avoid making rewards feel like a manipulative bribe to start with, you also should avoid overusing the same reward or presenting the reward in a way that makes the recipient uncomfortable. But there are always ways to make rewards even more exciting. There are dozens of ways you can put a new spin on tactics such as the Endowed Progress Effect or anticipation build-up. Get creative and have fun with your reward strategy—that’s the best way to make it as effective as possible.

A great launch is crucial to a successful online rewards program. From setting up the right goals and incentive rewards offering to marketing and communicating the program to your audience, the beginning is exciting but has to be planned carefully. So how do you pull off the best possible online rewards program launch? Read More!

Rewards | Psychology Wiki | Fandom

in: Pages with broken file links, Articles lacking reliable references from December 2012, Conditioning,

and 3 more

View source Assessment | Biopsychology | Comparative | Cognitive | Developmental | Language | Individual differences | Personality | Philosophy | Social |

Methods | Statistics | Clinical | Educational | Industrial | Professional items | World psychology |

Professional Psychology: Debating Chamber · Psychology Journals · Psychologists

Please help recruit one, or improve this page yourself if you are qualified.

This banner appears on articles that are weak and whose contents should be approached with academic caution.

A reward is a subjectively pleasurable or satisfying event or experience that follows the completion of a task. The attainment of reward is reinforcement for the preceding action in conditioning paradigms. The rat receives a food pellet as a reward for pressing the bar and this serves as a reinforcement for its actions.From this one can see that the two terms are not completely synonymous.

Drugs of abuse target the brain's pleasure center.[1]

Certain neural structures, called the reward system, are critically involved in mediating the effects of reinforcement. A reward is an appetitive stimulus given to a human or some other animal to alter its behavior. Rewards typically serve as reinforcers. A reinforcer is something that, when presented after a behavior, causes the probability of that behavior's occurrence to increase. Note that, just because something is labelled as a reward, it does not necessarily imply that it is a reinforcer. A reward can be defined as reinforcer only if its delivery increases the probability of a behavior.[1]

Note that, just because something is labelled as a reward, it does not necessarily imply that it is a reinforcer. A reward can be defined as reinforcer only if its delivery increases the probability of a behavior.[1]

Reward or reinforcement is an objective way to describe the positive value that an individual ascribes to an object, behavioral act or an internal physical state. Primary rewards include those that are necessary for the survival of species, such as food, sexual contact, or successful aggression.[2] Secondary rewards derive their value from primary rewards. Money is a good example. They can be produced experimentally by pairing a neutral stimulus with a known reward. Things such as pleasurable touch and beautiful music are often said to be secondary rewards, but such claims are questionable. For example, there is a good deal of evidence that physical contact, as in cuddling and grooming, is an unlearned or primary reward.[3] Rewards are generally considered more desirable than punishment in modifying behavior. [4]

[4]

Contents

- 1 Definition

- 2 Types of reward

- 3 History

- 4 Anatomy of the reward system

- 4.1 Animals vs humans

- 5 Modulation by drugs

- 5.1 Psychological drug tolerance

- 5.2 Sensitization

- 5.3 Neurotransmitters and reward circuits

- 6 See also

- 7 References

Definition

In neuroscience, the reward system is a collection of brain structures that attempts to regulate and control behavior by inducing pleasurable effects. It is a brain circuit that, when activated, reinforces behaviors. The circuit includes the dopamine-containing neurons of the ventral tegmental area, the nucleus accumbens, and part of the prefrontal cortex.[5]

Rewards induce learning, approach behaviour and feelings of positive emotions.

Types of reward

- External rewards

- Internal rewards

- Monetary rewards

- Physical rewards such as brain stimulation reward

- Preferred rewards

- Primary rewards include those that are necessary for the survival of the species, such as food, water, and sex.

Some people include shelter in primary reward.

Some people include shelter in primary reward.

- Secondary rewards derive their value from the primary reward and include money, pleasant touch, beautiful faces, music etc. The functions of rewards are based directly on the modification of behavior and less directly on the physical and sensory properties of rewards. For instance, altruism may induce a larger psychological reward, although it doesn't cause physical or sensory sensations, thus favouring such behaviour, also known as psychological egoism.

History

James Olds and Peter Milner were researchers who found the reward system in 1954. They discovered, while trying to teach rats how to solve problems and run mazes, stimulation of certain regions of the brain. Where the stimulation was found seemed to give pleasure to the animals. They tried the same thing with humans and the results were similar.

File:Skinner box scheme 01.pngSkinner box

In a fundamental discovery made in 1954, researchers James Olds and Peter Milner found that low-voltage electrical stimulation of certain regions of the brain of the rat acted as a reward in teaching the animals to run mazes and solve problems. [6][7] It seemed that stimulation of those parts of the brain gave the animals pleasure,[6] and in later work humans reported pleasurable sensations from such stimulation. When rats were tested in Skinner boxes where they could stimulate the reward system by pressing a lever, the rats pressed for hours.[7] Research in the next two decades established that dopamine is one of the main chemicals aiding neural signaling in these regions, and dopamine was suggested to be the brain's “pleasure chemical”.[8]

[6][7] It seemed that stimulation of those parts of the brain gave the animals pleasure,[6] and in later work humans reported pleasurable sensations from such stimulation. When rats were tested in Skinner boxes where they could stimulate the reward system by pressing a lever, the rats pressed for hours.[7] Research in the next two decades established that dopamine is one of the main chemicals aiding neural signaling in these regions, and dopamine was suggested to be the brain's “pleasure chemical”.[8]

Anatomy of the reward system

The major neurochemical pathway of the reward system in the brain involves the mesolimbic and mesocortical pathways. Of these pathways, the mesolimbic pathway plays the major role, and goes from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) via the medial forebrain bundle to nucleus accumbens. The VTA is the primary release site for the neurotransmitter dopamine. Dopamine acts on D1 or D2 receptors to either stimulate (D1) or inhibit (D2) the production of cAMP. [citation needed]

[citation needed]

Humans and animals seem to have a similar sense of pleasure.[9] However, pleasure is qualitatively and quantitatively different in humans than in animals.[citation needed] The human brain deciphers pleasant events and adds depth by changing the way humans pay attention and notice pleasures. The sense of pleasures differ in humans compared to animals because culture, life events, art, and other cognitive sources expand our understanding. This can make one realize how great a pleasure is or how displeasurable it may be.[10]

Animals vs humans

Based on data from Kent Berridge, the liking and disliking reaction involving taste shows similarities among humans, chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans. Most neuroscience studies have shown that dopamine alterations change the level of likeliness toward a reward, which is called the hedonic impact. This is changed by how hard the reward is worked for. Experimenter Berridge modified testing a bit when working with reactions by recording the facial expressions of liking and disliking. Berridge discovered that by blocking dopamine systems there did not seem to be a change of the positive reaction to something sweet; in other words, the hedonic impact remained the same even with this change. It is believed that dopamine is the brain's main pleasure neurotransmitter but, with these results, that did not seem to be the case. Even with more intense dopamine alterations, the data seemed to remain the same. This is when Berridge came up with the incentive salience hypothesis to explain why the dopamine seems to only sometimes control pleasure when in fact that does not prove to be happening at all. This hypothesis dealt with the wanting aspect of rewards. Scientists can use this study done by Berridge to further explain the reasoning of getting such strong urges when addicted to drugs.

This is changed by how hard the reward is worked for. Experimenter Berridge modified testing a bit when working with reactions by recording the facial expressions of liking and disliking. Berridge discovered that by blocking dopamine systems there did not seem to be a change of the positive reaction to something sweet; in other words, the hedonic impact remained the same even with this change. It is believed that dopamine is the brain's main pleasure neurotransmitter but, with these results, that did not seem to be the case. Even with more intense dopamine alterations, the data seemed to remain the same. This is when Berridge came up with the incentive salience hypothesis to explain why the dopamine seems to only sometimes control pleasure when in fact that does not prove to be happening at all. This hypothesis dealt with the wanting aspect of rewards. Scientists can use this study done by Berridge to further explain the reasoning of getting such strong urges when addicted to drugs. Some addicts respond to certain stimuli involving neural changes caused by drugs. This sensitization in the brain is similar to the effect of dopamine because wanting and liking reactions occur. Human and animal brains and behaviors experience similar changes regarding reward systems because they both are so prominent.[9]

Some addicts respond to certain stimuli involving neural changes caused by drugs. This sensitization in the brain is similar to the effect of dopamine because wanting and liking reactions occur. Human and animal brains and behaviors experience similar changes regarding reward systems because they both are so prominent.[9]

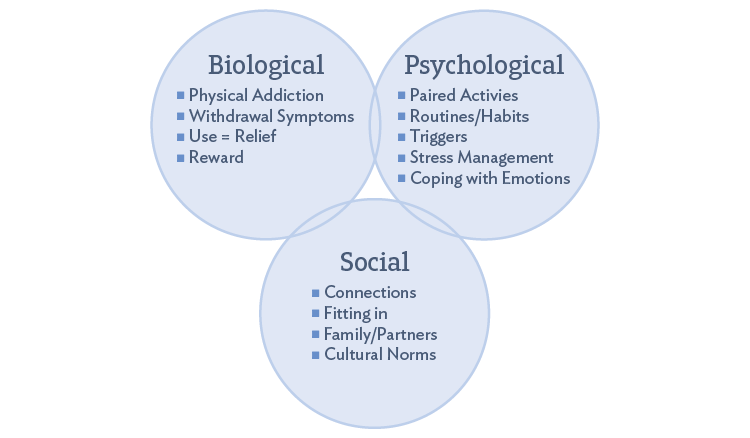

Modulation by drugs

- Main article: Drug addiction

Almost all drugs causing drug addiction increase the dopamine release in the mesolimbic pathway,[11] e.g. opioids, nicotine, amphetamine, ethanol, and cocaine. After prolonged use, psychological drug tolerance and sensitization arises.[citation needed] Drugs have many different effects on the brain; however, they all follow the same path. They stimulate the brain in various ways to receive a reward or, in this case, a high. The relationship between drugs and the reward system is rather close. Drugs provide an almost-immediate reward that often leads to addiction. For example, one drinks alcohol to feel intoxicated. This would be considered to be positive reinforcement. On the other hand, if one were to quit after long periods of binge drinking, there is a strong possibility of alcohol withdrawal symptoms. This would be identified as negative reinforcement. In “Neurobiology of alcohol dependence: focus on motivational mechanisms,” Gilpin states that the path from positive to negative reinforcement is taken as a drug's impact on the brain moves from abuse to dependence.

For example, one drinks alcohol to feel intoxicated. This would be considered to be positive reinforcement. On the other hand, if one were to quit after long periods of binge drinking, there is a strong possibility of alcohol withdrawal symptoms. This would be identified as negative reinforcement. In “Neurobiology of alcohol dependence: focus on motivational mechanisms,” Gilpin states that the path from positive to negative reinforcement is taken as a drug's impact on the brain moves from abuse to dependence.

Psychological drug tolerance

The reward system is partly responsible for the psychological part of drug tolerance. One explanation of this is a sustained activation of the CREB protein, causing a larger dose to be needed to reach the same effect.[citation needed]

Sensitization

Sensitization is an increase in the user's sensitivity to the effects of the substance, counter to the effects of CREB. A transcription factor, known as delta FosB, is thought to be involved by activating genes that causes sensitization. The hypersensitivity that it causes is thought to be responsible for the intense cravings associated with drug addiction, and is often extended to even the peripheral cues of drug use, such as related behaviors or the sight of drug paraphernalia.[12]

The hypersensitivity that it causes is thought to be responsible for the intense cravings associated with drug addiction, and is often extended to even the peripheral cues of drug use, such as related behaviors or the sight of drug paraphernalia.[12]

Neurotransmitters and reward circuits

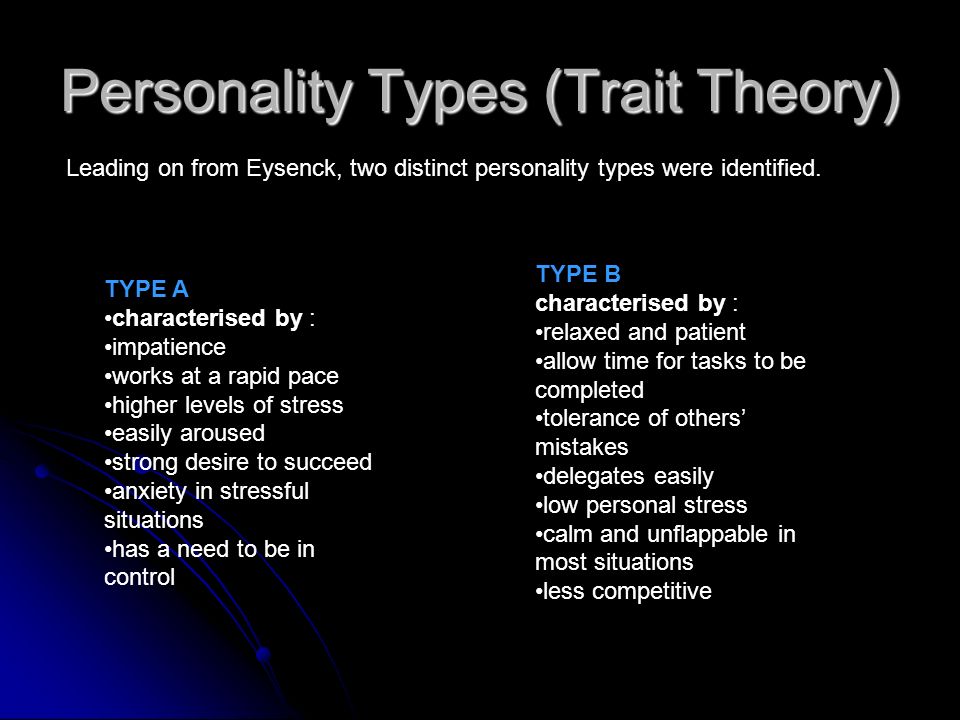

Dopamine is one of the primary neurotransmitters involved in drug consumption and addiction. Dopamine receptors are stimulated while someone is consuming a drug or when the thought of doing a drug occurs. In fact, decreases in dopamine levels occur during the withdrawal stage of quitting a drug like cocaine or alcohol. Serotonin is another neurotransmitter targeted by drugs. Endorphins are another type of neurotransmitter targeted by drugs. Endorphins are related to pain, fear, sex, and drugs. Certain drugs stimulate serotonin and endorphin receptors, which creates a type of euphoria. Neurotransmitters such as these play a major role in the reward systems of the brain. However, the manipulation of these neurotransmitters can have adverse affects on a human being. The continued use of drugs can cause degeneration of such neurotransmitters causing personality disorders and prolonged personality changes in an individual.

The continued use of drugs can cause degeneration of such neurotransmitters causing personality disorders and prolonged personality changes in an individual.

See also

- Bonuses

- Brain stimulation reward

- Classical conditioning

- Decision making

- Delay of gratification

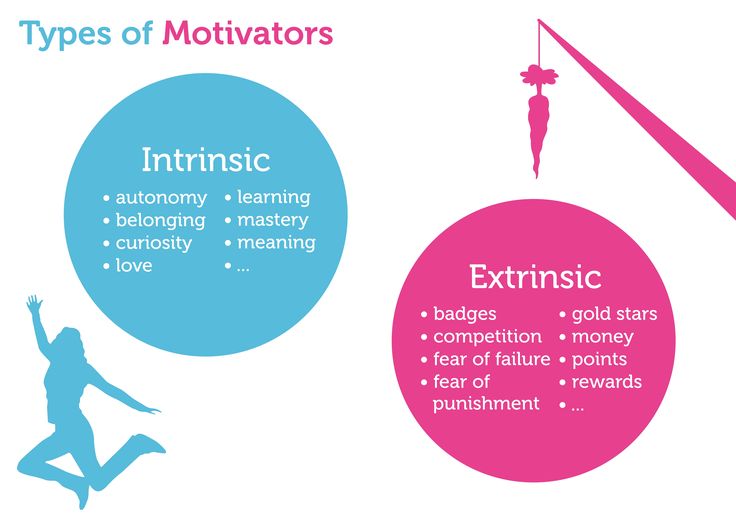

- Extrinsic motivation vs Intrinsic motivation

- Incentives

- Incentive salience

- Learned industriousness

- Monetary incentives

- Monetary rewards

- Motivation

- Pleasure center

- Preferred rewards

- Premack principle

- Reward allocation

- Drug addiction#Reward circuit

- Anterior cingulate cortex#Reward based learning theory

- Reward management

- Reward system

- Reinforcement

- Reinforcer

- Satisfaction

References

- ↑ 1.01.1 Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction. drugabuse.gov.

- ↑ includeonly>"Dopamine Involved In Aggression", Medical News Today, 2008-01-15.

Retrieved on 2010-11-14.

Retrieved on 2010-11-14. - ↑ Harlow, H. F. (1958) The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13, 679-685

- ↑ includeonly>"Smacking children 'does not work'", BBC News, 1999-01-11. Retrieved on 2010-05-22.

- ↑ Associated Behavioral Health.

- ↑ 6.06.1 human nervous system.

- ↑ 7.07.1 Positive Reinforcement Produced by Electrical Stimulation of Septal Area and Other Regions of Rat Brain.

- ↑ The Functional Neuroanatomy of Pleasure and Happiness.

- ↑ 9.09.1Berridge, Kent Affective neuroscience of pleasure: reward in humans and animals. URL accessed on 20 October 2012.

- ↑ Bear, Mark (2006). Neuroscience, 522–525, Library of Congress Cataloging.

- ↑ Rang, H. P. (2003). Pharmacology, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ Robinson TE & Berridge KC (1993).

The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Research Reviews 18 (3): 247–91.

The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Research Reviews 18 (3): 247–91.

Community content is available under CC-BY-SA unless otherwise noted.

Overjustification effect | Blog 4brain

Think about your favorite hobby. It can be playing volleyball or backgammon, knitting, reading or collecting coins. You get pure joy and pleasure from this activity, and no external reward. The activity itself is your reward.

Now imagine that you are being paid for your favorite hobby. Would you be surprised to learn that the desire to do it will decrease? But it's true. In psychology, this phenomenon is called the overjustification effect and has a serious impact on a person's motivation and behavior. Let's take a closer look at what this phenomenon is and why it occurs.

Definition and causes of the overjustification effect

Some activities, such as eating, socializing, or hobbies, are interesting in themselves, and people perform them without special encouragement. Other actions are usually performed only for the purpose of obtaining external rewards. For example, adults go to work because they are paid, and children make beds or take out the trash for praise or a modest fee from their parents. Such behavior is encouraged from outside, and when the reward stops, so does the behavior.

Other actions are usually performed only for the purpose of obtaining external rewards. For example, adults go to work because they are paid, and children make beds or take out the trash for praise or a modest fee from their parents. Such behavior is encouraged from outside, and when the reward stops, so does the behavior.

i.e. some activities are inherently satisfying, while others are extrinsic. Theoretically, in all cases, rewards should increase the likelihood of repeating a given behavior. However, something strange happens when a reward is given for activities that are interesting in their own right. At first, when both the inner desire and the outer stimulus are present, the person continues the activity. But if the reward is removed, he stops performing actions, losing his intrinsic interest. This is the over-justification effect.

The overjustification effect is a phenomenon in which being rewarded for something actually reduces intrinsic motivation to perform that task. An activity that was previously interesting in itself loses its appeal after a person is rewarded for performing it. This leads to an ironic and surprising result: the reward for the behavior prevents it from being repeated in the future.

An activity that was previously interesting in itself loses its appeal after a person is rewarded for performing it. This leads to an ironic and surprising result: the reward for the behavior prevents it from being repeated in the future.

For example, an artist is intrinsically motivated to paint because he enjoys putting paint on canvas and producing a vibrant painting. Suppose someone starts paying him for creativity. Over time, the artist will realize that he paints for the sake of money, which means that he really does not like to paint for the sake of the process itself. Accordingly, payment will reduce the internal motivation of the artist to work.

The main reason why the overjustification effect occurs is this: material incentives involve external intervention. As a consequence, the individual feels that his autonomy is compromised and hence his inner needs are not being met. The presence of encouragement from the outside can also be perceived by the psyche as a reproach for incompetence or insufficient motivation to complete the task, which gives rise to a feeling of inferiority. Finally, material incentives prevent a person from demonstrating altruistic behavior and question his ability to satisfy the need to develop relationships.

Finally, material incentives prevent a person from demonstrating altruistic behavior and question his ability to satisfy the need to develop relationships.

Classical studies of the overjustification effect

The overjustification effect has been demonstrated in many studies. Social psychology professors Mark Lepper, David Green, and Richard Nisbett were among the first to discover this pattern. In 1973, they conducted a famous experiment. Undergraduate students who showed intrinsic motivation to solve puzzles, i.e. performed them for pleasure, divided into two groups. The first group began to be paid for solving problems, and the second continued to do so without remuneration. Then the financial incentive was removed, and both groups again found themselves on an equal footing.

As a result, students who were paid money lost interest in solving puzzles when the payments stopped. And students who didn't receive rewards continued to find them fascinating. Thus, extrinsic motivation (money) has replaced intrinsic motivation (pleasure). The game has become work. The experiment confirmed that when people receive external rewards for what they like to do, their internal motivation weakens, and activities become more focused on external rewards.

The game has become work. The experiment confirmed that when people receive external rewards for what they like to do, their internal motivation weakens, and activities become more focused on external rewards.

Lepper and colleagues found a similar effect of overjustification in children. Toddlers aged 3-5 years, who love to draw with felt-tip pens, were divided into three groups. The subjects from the first group were promised to receive a Good Player ribbon for drawing. Children from the second group were not told about the reward in advance, but were given it after they finished drawing. The third group was the control group: no reward was promised or given to them. Later, the reward was canceled, and the subjects were given the opportunity to freely use felt-tip pens.

The experiment showed that children who were previously promised a reward drew much less often. Their interest has declined as the incentive to participate in this activity has disappeared due to the lack of an external stimulus. There were no changes in interest in the second and third groups. From which the conclusion was drawn: if a person performs an action and expects a reward, his internal interest in the task decreases, but an unexpected reward does not change internal motivation.

There were no changes in interest in the second and third groups. From which the conclusion was drawn: if a person performs an action and expects a reward, his internal interest in the task decreases, but an unexpected reward does not change internal motivation.

Manifestation of the effect of overjustification in everyday life

The importance of the overjustification effect lies in its wide manifestation in everyday life. Most people believe that in order to get someone to perform a certain action, they need to offer a reward. This logic is true when the activity is inherently unpleasant or unattractive, but not when the activity is intrinsically interesting.

For example, children do not need additional motivation to learn about the world around them, they explore it with enthusiasm. However, natural curiosity fades at school, and the typical student finds lessons and schoolwork burdensome. Of course, there are many reasons for the decline in interest, but the foundation is an education system focused on dependence on grades.

Although studying biology or mathematics can be interesting in itself, most students soon realize that their only motivation to study the material is the promised reward of an A or the threat of a punishment of a D. The non-grading system of education, which is used in primary schools in some countries, including Russia, contributes to the growth of internal interest in acquiring knowledge.

The same applies to adults. Many people choose a career based on love of work. When a profession is poorly paid, a specialist still has a reason to continue working - an internal interest. But as soon as the salary increases and gives its own rationale, it tends to crowd out the original internal cause and change the attitude forever. A person begins to like the salary, not the job. Financially, getting a pay raise is always a blessing, but psychologically, such luck may not have the most rosy consequences.

To live in harmony with your own psyche and learn how to manage the processes taking place in it, take the online program "Psychic Self-Regulation". It is suitable for those who want to become free from worries, fear, procrastination and stress. In 6 weeks, you will master various techniques of mental self-regulation, increase concentration, attention, social adaptation and strengthen your will.

It is suitable for those who want to become free from worries, fear, procrastination and stress. In 6 weeks, you will master various techniques of mental self-regulation, increase concentration, attention, social adaptation and strengthen your will.

How to avoid the effect of overjustification

Does external reward always generate the effect of overjustification? It turns out not. If a reward is given for the good performance of an action, it does not have a negative effect on intrinsic motivation. A reward for good work shows that a person has skills in any activity, which increases his personal interest.

If the reward is given simply because the action was performed, it is seen by the psyche as undermining autonomy and reduces interest in the activity. For this reason, parents shouldn't say, for example, "I'll only let you play on the computer after you've spent an hour on the piano." This will mean that the child can randomly tap the keys for an hour, just to pass the time. Instead, say, “If you can play all the scales at least once without mistakes, you can play on the computer,” and then praise the child for good results.

Instead, say, “If you can play all the scales at least once without mistakes, you can play on the computer,” and then praise the child for good results.

Rewards are not always bad, even if the activity for which they are given is enjoyable. However, rewards should be used carefully and only given for good performance. The same applies to verbal praise as a form of encouragement. When a person is successful, they should be praised for their efforts (“You worked so hard!”), Not their abilities (“You are so smart!”). After all, if a person believes that success depends on effort, then if obstacles arise in the future, he is more likely not to lose motivation, but to continue acting. The purpose of praise should be to evoke a sense of competence and confidence in achieving success with sufficient effort.

Punishment and the effect of overjustification

So far, to illustrate the effect of overjustification, we have given examples of rewards. However, the same conceptual process applies to punishments. Imagine that you are taking an important test and intend to get only an A. You have the opportunity to cheat the examiner and thus earn the highest score, but you do not want to do this. When you later ask yourself, "Why didn't I cheat?", the answer is likely to be, "Cheating is wrong." But in fact, you came to this conclusion only because it was easy to cheat.

Imagine that you are taking an important test and intend to get only an A. You have the opportunity to cheat the examiner and thus earn the highest score, but you do not want to do this. When you later ask yourself, "Why didn't I cheat?", the answer is likely to be, "Cheating is wrong." But in fact, you came to this conclusion only because it was easy to cheat.

Now imagine that the exam is closely watched by several examiners, and you have been warned of the serious consequences of any violations. If you ask yourself again why you didn't cheat, the main explanation is: "Because I would have been caught." As a result, your belief that “cheating is bad” will be displaced, and there is a good chance that next time you will shamelessly violate your moral principles. Thus, as the threat of punishment increases, the likelihood that a person will internalize a behavioral prohibition decreases.

This does not mean that punishment does not work. It works, but only when it is well-deserved and dosed. That is, the magnitude of the punishment should be sufficient to suppress the unwanted behavior, but not so severe as to distort the intrinsic justification for the negative behavior.

That is, the magnitude of the punishment should be sufficient to suppress the unwanted behavior, but not so severe as to distort the intrinsic justification for the negative behavior.

The over-justification effect occurs when a person decides that he has completed a potentially enjoyable task only because of external reasons, and not because he likes to do it. The reward provides sufficient justification for completing the task, so the person comes to the conclusion that he does not like this task.

Therefore, the goal of parents, teachers or employers should be to evoke intrinsic motivation in their students, since liking for the task increases hard work and performance. If rewarding or forcing an activity through external pressure leads a person to the conclusion that the activity is not pleasurable, then in the long run the reward or pressure becomes counterproductive.

This concludes the article, and in conclusion, we propose to pass a small test to check how well we managed to assimilate the information:

Friends, do what you love and love what you do. Be dedicated to your work and let decent fees increase your level of satisfaction.

Be dedicated to your work and let decent fees increase your level of satisfaction.

📖 Laws of reward. Man with money. The psychology of wealth. Stepanov SS Page 6. Read online

Salary is a measure of respect with which society treats this profession.

John Tillmon

In different parts, in every way (with the mention of different coins), they tell the same instructive parable.

One day the neighbor boys began to annoy the elderly farmer. They chose the lawn in front of his house for their noisy games. Children's running and screaming did not give the farmer peace. At first he kindly asked the boys to get out, then he began to shame, and finally burst into an angry cry. And all to no avail. Then he changed tactics.

One day the farmer kindly invited the guys to the veranda, treated them to sweets and said: “I am very glad, boys, that you are playing near my house. My children have long grown up and moved away, and I am pleased to look at you. Please come every day. For this, I will pay everyone 25 cents.”

Please come every day. For this, I will pay everyone 25 cents.”

The boys enthusiastically agreed. All the next day they ran around the lawn with a cackle, and in the evening each received the money he had earned. And so it went on for several days.

But one day the farmer called the boys again and said, “My business is not going well, and it's hard for me to pay you 25 cents a day. From tomorrow you will receive 15 cents.

The boys grumbled, but the next day they continued their games. True, already with less enthusiasm.

A few days later, the farmer announced, “I can't handle 15 cents a day either. From tomorrow you will receive five.

- Oh no, old man! the boys were outraged. - For such pennies, run around your own lawn!

From that day on, peace reigned on the farm.

This parable can be interpreted in different ways. We will clarify the most important thing. With the help of rewards, one can fundamentally manipulate human behavior, change it in the right direction, encourage or inhibit this or that activity.

However, the fact that the monetary reward has a great incentive force is not a secret for a long time. Interesting - which one?

The role of money, among other factors that motivate a person to activity, has been studied by psychologists for more than a hundred years, but to this day they have not come to unambiguous and unconditional conclusions.

The American F. Taylor is considered the first specialist in the scientific organization of labor (and, accordingly, in labor motivation). His theory was based on the main postulate: additional earnings are an incentive to increase labor efforts. That is, a person is ready to do everything that brings him more money. One of Taylor's first experiments, the hero of which was a loader named Schmidt, became a textbook. He was one of the members of the brigade, where each accounted for a frightening daily norm - it was required to load twelve and a half tons of cast-iron ingots into railway cars. The workers swore that it was very difficult to meet this norm, and it was impossible to exceed it. However, Schmidt, following Taylor's detailed instructions for organizing the labor process, managed to exceed the norm by almost four times. Accordingly, his income increased. The inspired loader adopted rational methods of labor and for three years in a row enthusiastically fulfilled the fourfold norm.

However, Schmidt, following Taylor's detailed instructions for organizing the labor process, managed to exceed the norm by almost four times. Accordingly, his income increased. The inspired loader adopted rational methods of labor and for three years in a row enthusiastically fulfilled the fourfold norm.

Here, however, it should be noted that Taylor's methods concerned mainly manual labor with a simple set of operations. Whether a material incentive can increase the productivity of more complex labor—say, mental labor—was long unclear.

When more detailed psychological studies of work motivation began, Taylor's theory required a reassessment. Large-scale surveys covering tens of thousands of people have shown that, in addition to material interest, many other factors also affect productivity and quality of work; moreover, among all stimulating factors, money is by no means in the first place. Dependence on reward certainly exists, but it should not be exaggerated.

However, the opinion of researchers does not coincide in everything with the opinion of industrial practitioners. As part of one of these surveys, workers and entrepreneurs were asked what a good job is. Moreover, the entrepreneurs were not interested in their personal opinion, but in what, in their opinion, the workers think about this. So, the workers themselves, evaluating the various parameters of their work that determine its merits, rarely started with pay. In the list of significant factors, money appeared, although not in the last, but not in the first place, somewhere in the middle. And entrepreneurs, trying to take the position of a worker, started with money. It seems that production leaders have a poor understanding of the structure of the priorities of their subordinates, exaggerate the value of material incentives and underestimate purely psychological motives. However, if you think about it, the situation is not so simple.

In any society, on the basis of age-old moral norms, an unspoken idea has developed that the pursuit of profit is reprehensible. Talking about their preferences, few people dare to frankly admit that money plays a paramount role for him. Not unimportant - certainly, but there are other, more important values. But in those around us, we willingly notice their flaws and weaknesses, moreover, we often attribute our own to them (according to the projection mechanism discovered by Freud). Probably, if one had asked the opinion of the workers about the motivation of entrepreneurs, the result would have been similar - they would have been credited with the reckless desire for profit as the leading motive.

Not unimportant - certainly, but there are other, more important values. But in those around us, we willingly notice their flaws and weaknesses, moreover, we often attribute our own to them (according to the projection mechanism discovered by Freud). Probably, if one had asked the opinion of the workers about the motivation of entrepreneurs, the result would have been similar - they would have been credited with the reckless desire for profit as the leading motive.

There is another important regularity. If in general the work is pleasant, then the payment, as a rule, suits, and this factor is considered not the most important. But when the job is not to their liking, there is a desire to change it, then the money factor moves from the middle of the list of values to one of the first places. And when comparing overall job satisfaction in groups of high-paid and low-paid workers, psychologists found that those who are well paid rate such parameters as informal relationships with colleagues, the fascination of the work process, career prospects, etc. , much higher. That is, money is implicitly present and in such aspects of a person's well-being in the workplace, which, it would seem, are not directly related to them. If the payment is high enough, the whole spectrum of non-material motivation is activated. Little pay - all other incentives are weakening.

, much higher. That is, money is implicitly present and in such aspects of a person's well-being in the workplace, which, it would seem, are not directly related to them. If the payment is high enough, the whole spectrum of non-material motivation is activated. Little pay - all other incentives are weakening.

However, the indicators themselves "little", "many" or "sufficient" are very relative. Many researchers are of the opinion that the difference between, say, one's own earnings and the earnings of others is a more stable factor of satisfaction than the size of earnings itself. As a result of a special analysis conducted in the United States, it was concluded that the most important factor in satisfaction can be considered the comparison of oneself with a "typical American". The higher the positive discrepancy (that is, the superiority over some typical image), the higher the satisfaction. With whom exactly do people prefer to compare themselves, if we are not talking about abstract “others”? As a result of a survey conducted among workers in the US state of Wisconsin, it was found that the majority tend to compare their wages with the wages of other workers, especially those who are engaged in similar work. The most tempting background for comparison are people living in the immediate environment, relatives, and former classmates.

The most tempting background for comparison are people living in the immediate environment, relatives, and former classmates.

The data of another survey show that representatives of working specialties in highly paid categories are more satisfied with their financial situation than intellectual workers who receive a similar salary. The thing is that the latter tend to compare their salary with the salary of other knowledge workers, for whom it is higher. Another study found that in the United States, people with a college education and a fairly good salary are less satisfied with their financial situation than those who do not have a college education but receive a similar salary.

In our conditions (we admit that they are far from absolute social justice), people turn out to be acutely sensitive to the “forks” of rates for different professions that have developed on the labor market (a researcher feels deprived if he gets less than a bus conductor), and within professional groups - for different skill levels and even jobs. When a teacher working in a general education public school receives significantly less than his colleague in a private lyceum, then, regardless of the absolute amount, the majority of teachers (civil servants) feel disadvantaged, and this, alas, does not have the best effect on the entire pedagogical process . Even Moscow teachers, not offended by the attention of the city government, find their salaries, flavored with a local allowance, humiliatingly low, while their provincial colleagues, comparing it with their own, find it very high. And there are many such examples.

When a teacher working in a general education public school receives significantly less than his colleague in a private lyceum, then, regardless of the absolute amount, the majority of teachers (civil servants) feel disadvantaged, and this, alas, does not have the best effect on the entire pedagogical process . Even Moscow teachers, not offended by the attention of the city government, find their salaries, flavored with a local allowance, humiliatingly low, while their provincial colleagues, comparing it with their own, find it very high. And there are many such examples.

People are no less sensitive to the ratio of salary and position. It seems only natural that top-level employees get more than their subordinates. Although, of course, the career aspirations of many are due not only to this factor. After all, climbing the career ladder, a person acquires greater social weight, the right to a respectful attitude towards himself, more scope for self-realization. Having taken a commanding position, a person gains power over people, takes control of at least some aspects of their behavior. Thus, the values that accompany wealth come to him in the most direct expression. But for a full sense of his privileged position, his monetary reinforcement is necessary. If the leader receives little more than subordinates, then he feels uncomfortable - he gets the impression that he occupies his position rather formally. He begins to be tormented by uncertainty, he begins to perceive his complex and responsible duties as burdensome. If the gap is too large, already subordinates are indignant, who will perceive this situation as an underestimation of their role and a clear injustice.

Thus, the values that accompany wealth come to him in the most direct expression. But for a full sense of his privileged position, his monetary reinforcement is necessary. If the leader receives little more than subordinates, then he feels uncomfortable - he gets the impression that he occupies his position rather formally. He begins to be tormented by uncertainty, he begins to perceive his complex and responsible duties as burdensome. If the gap is too large, already subordinates are indignant, who will perceive this situation as an underestimation of their role and a clear injustice.

In some cases, money can camouflage the real reasons for dissatisfaction with industrial relations. Psychologists who studied the internal motives of professional conflicts, including such large-scale ones as strikes, were repeatedly convinced of this. The most common demand of the strikers is an increase in wages. "We don't have enough to live on!" say the strikers, with very persuasive arguments. Characteristically, these slogans are used by workers in all parts of the world, even in the so-called developed countries, despite the fact that the salary of the average European worker would be enough to support, say, several Singaporean or Malay families. This is how this world works - there is no such person, family, people or state that would not need money. However, a careful analysis reveals that completely different motives induce decisive action. Employees can be annoyed by the arrogance of the authorities, ignoring their initiative, neglecting their personal interests, etc., etc. But how can these feelings be expressed in the form of a formal claim? "You treat us badly"? There is no such formula in business relationships. In addition, such a wording would put the protesters in a ridiculous position in the eyes of others, and even their own. Money in this case acts as a symbolic compensation for moral damage. By the way, this is another specific function of theirs [Russian teachers describe with bewilderment such a previously unthinkable phenomenon.

Characteristically, these slogans are used by workers in all parts of the world, even in the so-called developed countries, despite the fact that the salary of the average European worker would be enough to support, say, several Singaporean or Malay families. This is how this world works - there is no such person, family, people or state that would not need money. However, a careful analysis reveals that completely different motives induce decisive action. Employees can be annoyed by the arrogance of the authorities, ignoring their initiative, neglecting their personal interests, etc., etc. But how can these feelings be expressed in the form of a formal claim? "You treat us badly"? There is no such formula in business relationships. In addition, such a wording would put the protesters in a ridiculous position in the eyes of others, and even their own. Money in this case acts as a symbolic compensation for moral damage. By the way, this is another specific function of theirs [Russian teachers describe with bewilderment such a previously unthinkable phenomenon. A teenager who was rudely insulted by a classmate agreed to receive a certain amount of money as an insult inflicted on him and at the same time was very pleased with the result. From a psychological point of view, this phenomenon is absolutely transparent, it is just that it is still perceived unusually within the framework of our culture.]. Although it seems strange that we, attaching such great importance to feelings, and considering money as something lower, allow them to be directly compared. In most civilized countries, the right of citizens to receive monetary compensation for moral damage, that is, wounded feelings, is legalized. Gradually, this practice comes into use in our country, although the responses are contradictory. Sometimes one hears: the plaintiff went too far, demanding ten million in compensation - a hundred thousand would have been enough. How to measure the compensation is not clear to anyone (it seems, even the judges themselves). Nevertheless, there is clearly a deep sense of proportionality, overpricing or underpricing.

A teenager who was rudely insulted by a classmate agreed to receive a certain amount of money as an insult inflicted on him and at the same time was very pleased with the result. From a psychological point of view, this phenomenon is absolutely transparent, it is just that it is still perceived unusually within the framework of our culture.]. Although it seems strange that we, attaching such great importance to feelings, and considering money as something lower, allow them to be directly compared. In most civilized countries, the right of citizens to receive monetary compensation for moral damage, that is, wounded feelings, is legalized. Gradually, this practice comes into use in our country, although the responses are contradictory. Sometimes one hears: the plaintiff went too far, demanding ten million in compensation - a hundred thousand would have been enough. How to measure the compensation is not clear to anyone (it seems, even the judges themselves). Nevertheless, there is clearly a deep sense of proportionality, overpricing or underpricing. Whether we like it or not, the course of converting emotions into money is deeply embedded in our subconscious. Denying that happiness can be bought, we are ready to admit that it is possible to smooth out resentment, humiliation, grief with money. But, in fact, we are talking about the same thing! There is reason to think.

Whether we like it or not, the course of converting emotions into money is deeply embedded in our subconscious. Denying that happiness can be bought, we are ready to admit that it is possible to smooth out resentment, humiliation, grief with money. But, in fact, we are talking about the same thing! There is reason to think.

Finally, the most difficult pay relationship of all is interprofessional. How much should be and how should the wages of a professor and a janitor, a tractor driver and a salesman, a security guard and a teacher differ, so that both themselves and others the amounts and their ratios seem fair?

Alas, there is no perfect answer to this question. Arguments about how much an American teacher receives more than a Russian one sound not at all so pathetic, if we take into account that even overseas a school teacher occupies a far from the highest place among fellow citizens in the salary rating. Why do some activities get a big, sometimes disproportionate advantage over others? There is no logic or common sense here. All that remains is to shrug your shoulders: “It just so happened,” and point out to a representative of a low-paid profession: “After all, you knew what you were getting into. If you don't like getting pennies for posting advertisements - go win the Wimbledon tennis tournament or at least open your own shop! Can not? And who is to blame for this?

All that remains is to shrug your shoulders: “It just so happened,” and point out to a representative of a low-paid profession: “After all, you knew what you were getting into. If you don't like getting pennies for posting advertisements - go win the Wimbledon tennis tournament or at least open your own shop! Can not? And who is to blame for this?

Psychology bookap

Attempts to logically substantiate apparent inequality are generally not very intelligible. For example, in the USA such a case took place. University professors were outraged by the decision of the state governor to cut local allocations intended to increase their salaries. Having exhausted all other arguments, the governor spoke of the great "psychological benefit" that professors receive from their prestigious status, from the creative nature of their work. Sounds very unconvincing. Don't lawyers, managers, not to mention entrepreneurs get similar "benefit"? Why does this not lead to a decrease in their income? The most remarkable thing is that the public, by a majority of votes, stood up in support of the far from indisputable position of the governor. Probably, each of us in the depths of our souls has some unconscious idea about the structure of the social world and who is worth how much in it. And only the obvious contradiction to this idea arouses our indignation.

Probably, each of us in the depths of our souls has some unconscious idea about the structure of the social world and who is worth how much in it. And only the obvious contradiction to this idea arouses our indignation.

In this regard, it is important to pay attention to one dangerous illusion concerning the high incomes of representatives of certain professions, primarily creative ones. The mass media, choking with delight, regale the layman with stories about the fantastic fees of Hollywood movie stars, eminent athletes, and pop music idols. A young man who is not without talent is sometimes strongly tempted to follow these impressive examples. Here it is necessary to remind oneself that figures of the scale of Madonna or Tom Cruise are calculated in units. Well, maybe dozens, even hundreds. But this is negligible against the backdrop of a multi-million army of modest screen and stage workers, rackets and clubs, who for the most part live very poorly, or even simply live on bread and water.