What are process notes

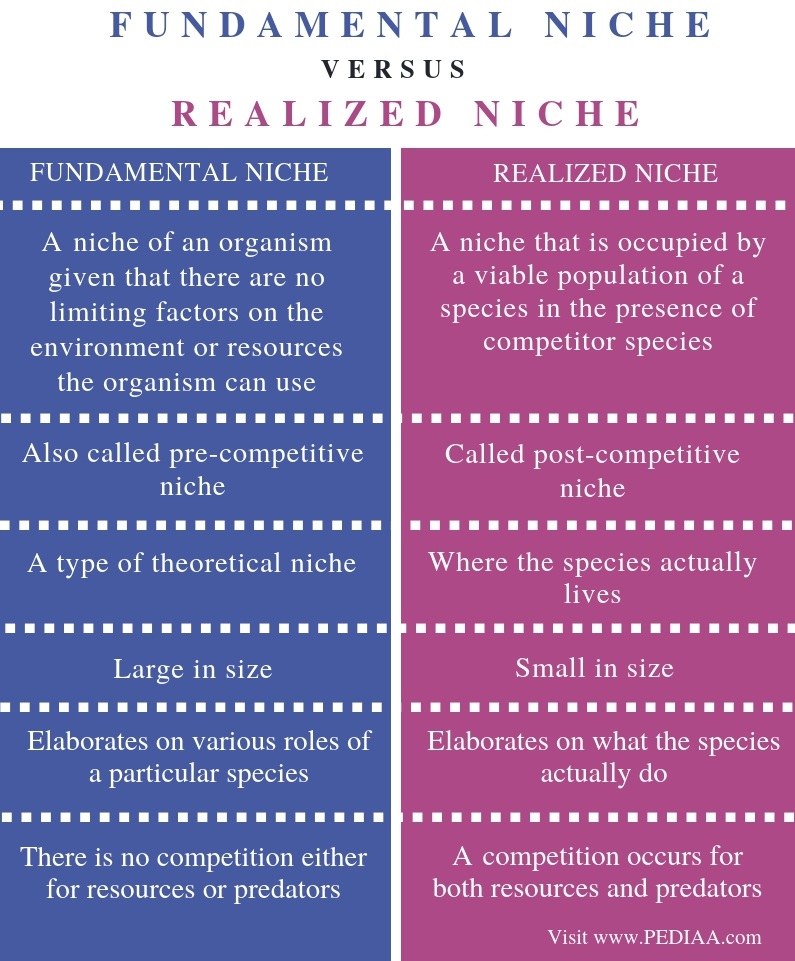

Psychotherapy Notes vs Progress Notes

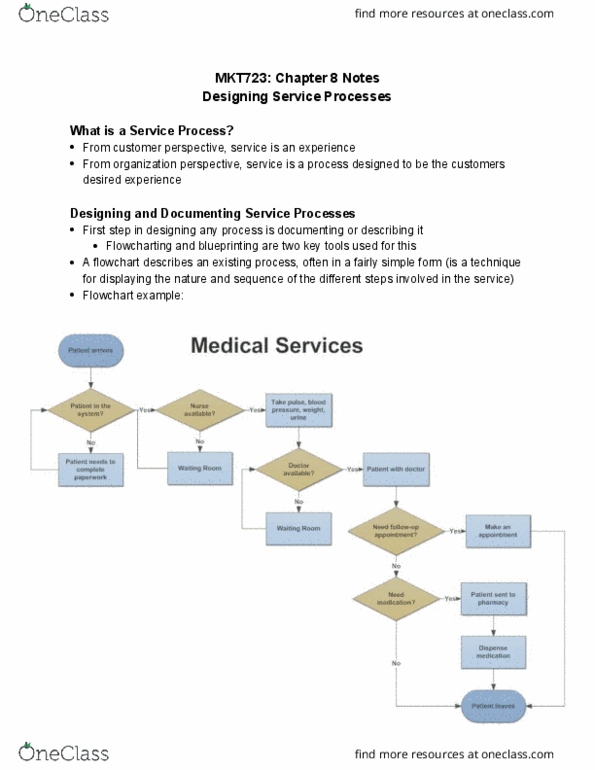

Behavioral health professionals know that note-taking is an essential component of great patient care. Detailed notes help mental health professionals diagnose and treat patients quickly and accurately. They also help patients make informed decisions about their health.

All healthcare professionals are required to properly document medical information. In the mental health field, counselors, psychologists and other professionals rely on insightful and thorough progress notes and psychotherapy notes to devise treatment plans.

Learn More About Writing Individualized Treatment Plans

Progress notes and psychotherapy notes are equally important but vastly different. They both must comply with privacy standards in their own way.

In 1996, Congress passed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) to protect the privacy and safety of health information. The Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information, or the Privacy Rule, was issued to implement HIPAA.

Since 2003, the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) has received over 177, 854 complaints and has made over 884 compliance reviews. Since a HIPAA violation is not something a healthcare practice wants for their reputation or a patient's well-being, it's important every healthcare employee is aware of HIPAA standards and the consequences of privacy violations.

In this post, we will explore HIPAA regulations and how they differ between psychotherapy notes and progress notes. We will also look at the different items psychotherapy and progress notes include, and why they are both necessary components of patient care.

What Are Psychotherapy Notes?

Psychotherapy notes, also called process or private notes, are notes taken by a mental health professional during a session with a patient. Psychotherapy notes usually include the counselor's or psychologist's hypothesis regarding diagnosis, observations and any thoughts or feelings they have about a patient's unique situation. After learning more about the patient, the counselor can refer to their notes when determining an effective treatment plan.

After learning more about the patient, the counselor can refer to their notes when determining an effective treatment plan.

These notes are kept separate from medical records and billing information, and providers are not permitted to share psychotherapy notes without a patient's authorization. The patient does not have the right to access these notes. In general, psychotherapy notes might include:

- Observations

- Hypotheses

- Questions to ask supervisors

- Any thoughts or feelings relating to the therapy session

Unlike progress notes, psychotherapy notes are private and are do not include:

- Medication details or records

- Test results

- Summary of diagnosis or treatment plan

- Summary of symptoms and prognosis

- Summary of progress

Psychotherapy notes receive special protection under the Privacy Rule because they contain sensitive information and because they are a therapist's personal notes. They do not contain information related to a patient's medical records, treatment or healthcare operations and therefore do not need to be shared with patients or staff. These types of notes are meant to help the therapist do their job the best way they can.

These types of notes are meant to help the therapist do their job the best way they can.

If a counselor sees a reason to share their psychotherapy notes, they must first obtain authorization from the patient. However the following circumstances do not require authorization and, in some cases, a counselor may be required to disclose their notes:

- To use the notes for treatment

- To defend themselves in court

- During a Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) investigation

- As required by law

- To prevent a serious threat to public health or safety

- For the lawful activities of a medical examiner or coroner

Because psychotherapy notes are not a required part of a counselor's job and are only meant to help a counselor treat a patient, there is no required format a counselor must follow. Therapists can create their psychotherapy notes however they wish. For example, the notes can be written in shorthand and be illegible to others without consequence.

However, it is still the counselor's responsibility to make sure the notes are not read by anyone else. They must keep the notes secure and confidential at all times. To avoid a HIPAA violation, a mental health professional does not want to keep a notepad filled with private information out in the open, for example.

Psychotherapy notes were not always protected. In the past, healthcare insurers made decisions based on patient information including psychotherapy notes. Now, under the Privacy Rule, patients can, in some cases, refuse to have that type of information released. Psychotherapy notes are not required for insurance purposes.

What Are Progress Notes?

Unlike psychotherapy notes, progress notes are meant to be shared with other healthcare workers who assist with a patient's treatment plan. Progress notes inform staff about patient care and communicate treatment plans, medical history and other vital information. Without accurate and up-to-date progress notes, healthcare professionals would need to start from the beginning each time they met with a patient. They would waste time and increase the risk of making a medical mistake.

They would waste time and increase the risk of making a medical mistake.

It's best for progress notes to follow a template, so all staff members document in the same way. Progress notes should be easy to access, clearly written and consistent in style to help minimize mistakes or misunderstandings. Progress notes are also essential documents in regards to billing and reimbursement.

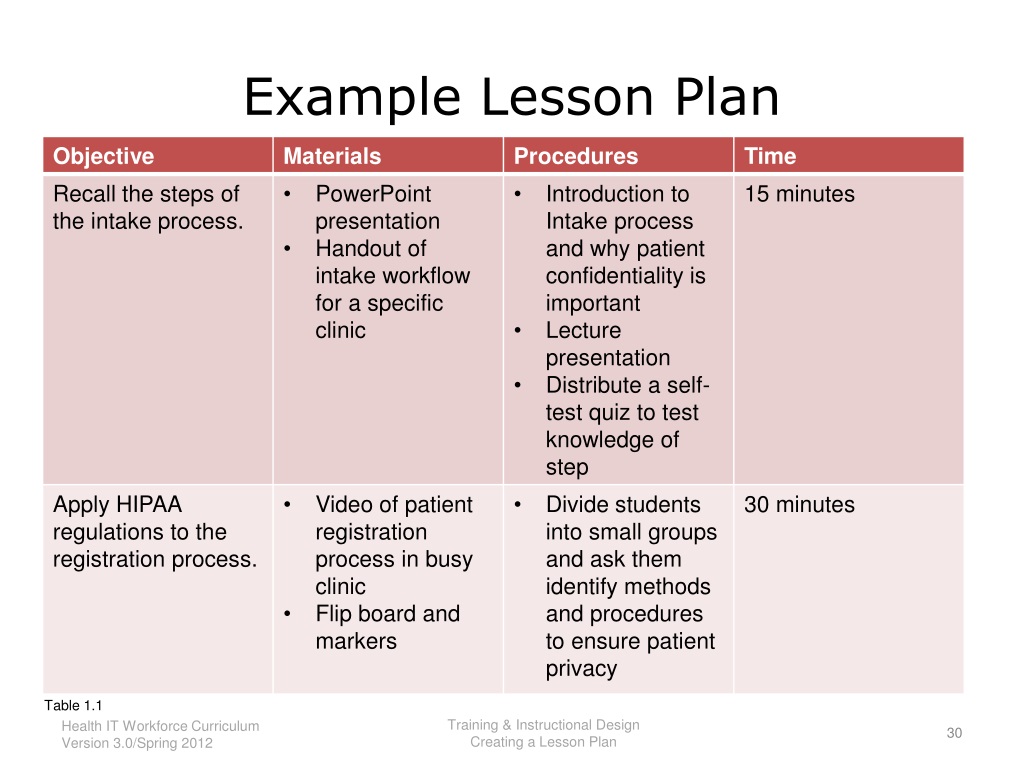

Healthcare providers are required to keep accurate progress notes to legally protect their patients and provide care for patients they see on a daily basis. Each progress note must address the following four components — subjective, objective, assessment and plan (SOAP).

- Subjective: Describes the patient's current condition as explained by the patient. The "chief complaint" is required. For example, if a patient complains of chest pain and a cough, this would be the chief complaint. A history of the patient's symptoms is also recorded here in the patient's own words.

- Objective: Includes findings from a physical examination.

- Assessment: Includes a summary of the patient's diagnosis.

- Plan: Includes what the healthcare provider will do to treat the patient. The plan portion of a progress note also includes follow-up information, referrals, lab orders and a review of all the medications a patient is taking.

Although progress notes are read by trained staff on a regular basis, they are still protected under the HIPAA Privacy Rule. In general, the following information is protected under HIPAA:

- Any individually identifiable health information relating to the individual's past, present or future physical or mental health

- The type of healthcare provided to the individual and the reasons for the care

- Information regarding the past, present or future payment for the care and treatment given to the individual

Individual identifiers include information such as name, address, birth date or social security number.

As with most rules, there are a few exceptions. A healthcare provider may disclose or use a patient's medical information or progress notes when:

- The Privacy Rule permits

- The patient authorizes use or disclosure in writing

In some cases, a healthcare provider is required to disclose patient information. This occurs when:

- The individual requests their information

- The HHS is conducting an investigation and requests the information

- Law enforcement requests the information

Sometimes a healthcare provider is permitted to disclose patient information to protect a patient or the public from harm. The following circumstances do not require a patient's authorization for disclosure:

- For treatment, payment or healthcare operations

- For public interest and benefits as required by law to prevent or control a disease

- For government authorities in cases of abuse, neglect or domestic violence

- For health oversight agencies during audits or investigations

- For judicial or administrative proceedings

- For law enforcement purposes

- For funeral directors, medical examiners or coroners as needed

- For research purposes

- When there are threats to public health or safety

- For essential government functions

- In regards to workers' compensation law

When an individual is incapacitated, in an emergency situation or not available, a healthcare professional may use their best judgment in deciding to disclose patient information to family members or personal representatives. In such a case, they could use an informal authorization from the patient if possible.

In such a case, they could use an informal authorization from the patient if possible.

Under HIPAA law, a healthcare provider must train all employees, volunteers and trainees to comply with privacy policies and procedures, and they must discipline those who violate HIPAA regulations. It is every healthcare provider's responsibility to make sure all data, like progress notes, is secure at all times, whether they need to shred paper documents or make sure electronic passcodes are set.

Because HIPAA requires highly secure record-keeping, it's best for healthcare practices to take proper precautions and store records electronically. When progress notes are stored electronically, they can be protected with passwords and virus protection. However, paper documents can be easily damaged, lost, misread or accessed by the wrong people and offer little protection for the patient.

What Are Best Practices for Psychotherapy and Progress Notes?

All protected health information (PHI) must be safeguarded according to the Privacy Rule, whether the information is stored electronically or on paper. The Security Rule, on the other hand, applies only to electronic protected health information (EPHI) and does not apply to information stored on paper or given orally.

The Security Rule, on the other hand, applies only to electronic protected health information (EPHI) and does not apply to information stored on paper or given orally.

Under the Security Rule, the following safeguards must be used to protect electronic information:

- Administrative safeguards: Refers to administrative functions implemented to ensure security, such as security training.

- Physical safeguards: Protecting data storage sources from environmental hazards and intruders by restricting access and having back up computers.

- Technical safeguards: Using automated processes to protect information and control who can access information.

To reduce the risk of a Security Rule violation, healthcare providers need to:

- Assess potential risks: Assess and identify any potential risks to the confidentiality of EPHI and implement plans to reduce risks. For example, security management needs to make sure files are protected by passwords.

Likewise, computer workstations should be located in rooms with locks on the doors.

Likewise, computer workstations should be located in rooms with locks on the doors. - Develop a sanctions policy: Make sure policies are in place, and employees are aware of the policies, to implement sanctions on those who violate security standards. Each employee must be trained in security standards. For example, employees should know not to share passwords or write down passwords and leave them in the open.

- Develop a data backup plan: Make sure to have a backup plan in case of an emergency like a fire or natural disaster to keep information protected and secure. Plan to have exact copies of retrievable information in an emergency situation.

- Practice business safety: Make sure there are contracts with outside entities to ensure security and HIPAA compliance.

- Consider the environment: All data equipment should be kept in a secure environment that is free of theft or unauthorized access. For example, make sure doors are kept lock or surveillance cameras are in place to provide protection.

- Dispose of information properly: Make sure employees know how to securely dispose of data when no longer in use, like using hardware erasure software.

- Control access: Each database user must have a unique identifier and password. It is also best to utilize automatic logoff capabilities and make sure data is encrypted.

A HIPAA violation can be detrimental to a practice's reputation and a patient's trust. Failure to comply can not only cost a healthcare practice thousands of dollars or more in fines, but they could lose clients and damage their name. For example, Fresenius Medical Care North America, a provider of products and services for people with chronic kidney failure, agreed to pay the HHS $3.5 million to settle possible HIPAA violations. Patients can also file lawsuits against healthcare providers. Common violations include:

- Unauthorized use of patient information

- Unsecured patient records

- Patients being unable to have access to their records

- Disclosing information to third parties more than necessary

- Not having any administrative or technological safeguards for EPHI

Most commonly investigated organizations include:

- Private practices

- Hospitals

- Outpatient facilities

- Insurance companies

- Pharmacies

Failure to comply can result in:

- A fine of $100 to $50,000 or more for each violation

- A calendar year cap of up to $1.

5 million

5 million - Up to ten years' imprisonment

Penalties depend on the following factors:

- Date of the violation

- Whether or not the healthcare provider or entity knew or should have known of the failure to comply

- Whether or not a failure to comply was due to willful neglect

To protect your practice, employees, patients and yourself from HIPAA violations, make sure patient data is kept secure at all times — it's an element of health care not to be overlooked.

The Benefits of EHR Software

HIPAA regulations do not need to cause daily stress in the workplace. Fortunately, there is software available to make security an effortless matter. Electronic health record (EHR) software keeps medical information and billing secure and makes sure HIPAA standards are followed without interrupting workflow.

EHR software protects important, confidential health information with a high level of security and efficiency, keeping progress notes, past medical history and demographics safe from unauthorized users. EHR software also makes information easily accessible for those with permission to use and record information. In general, EHR software helps healthcare professionals provide better patient care by:

EHR software also makes information easily accessible for those with permission to use and record information. In general, EHR software helps healthcare professionals provide better patient care by:

- Boosting accuracy and reducing medical error

- Improving communication

- Reducing billing issues

- Consolidating information

- Reducing delays in care

- Helping patients make better decisions

- Improving the quality of care

ICANotes is behavioral health EHR software ensures your electronic health records are HIPAA compliant. With ICANotes you can rest assured that all your data is secure, and you can enjoy more time with patients and less time with paperwork. Our intuitive software helps healthcare staff keep an accurate record of patient information while meeting all HIPAA standards. ICANotes features:

- Full encryption of transmitted data

- Password and username protection

- Private separation of psychotherapy notes

- Integration options

- Intuitive note templates for progress notes, therapy notes, treatment plans and more

- Billing solutions

- Organized scheduling solutions

ICANotes helps behavioral health professionals enjoy:

- Better workflow

- More time with patients

- Accessible documentation

- Greater documentation accuracy

- Secure and HIPAA-compliant data storage

- Comprehensive and customizable note-taking templates

With ICANotes you can spend more time doing what you love to do — caring for your patients. Put the focus back on patient care and enjoy your career with ICANotes. For more information, request a free trial, watch a live demo or contact us today.

Put the focus back on patient care and enjoy your career with ICANotes. For more information, request a free trial, watch a live demo or contact us today.

Related Posts:

How to Create a Group Therapy Note

How to Create a Psychotherapy Note

How to Create an Effective Psychiatric Progress Note

The 10 Essential Elements of Any Therapy Note

Tips for Writing Better Mental Health SOAP Notes

Guide to Creating Mental Health Treatment Plans

October Boyles, MSN, BSN, RN

Clinical Director October has been a Registered Nurse for over 15 years. She is board certified in Mental Health and Psychiatric Nursing. She holds a Bachelor of Arts from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She also graduated with bachelor and master degrees in Nursing from Western Governors University.

Complete a Process Note - TherapyNotes Help Center

While Progress Notes in TherapyNotes feature robust templates to ensure that your notes are organized, clear, and complete, the Process Note is a free-text note that functions differently than a Progress Note. HIPAA has a specific definition for psychotherapy notes, which are what TherapyNotes refers to as Process Notes:

HIPAA has a specific definition for psychotherapy notes, which are what TherapyNotes refers to as Process Notes:

"Psychotherapy notes” means notes recorded (in any medium) by a health care provider who is a mental health professional documenting or analyzing the contents of conversation during a private counseling session or a group, joint, or family counseling session and that are separated from the rest of the of the individual’s medical record. Psychotherapy notes excludes medication prescription and monitoring, counseling session start and stop times, the modalities and frequencies of treatment furnished, results of clinical tests, and any summary of the following items: diagnosis, functional status, the treatment plan, symptoms, prognosis, and progress to date.

Role Required: Clinician, or Clinical Administrator

Tip: Process Notes are not billable, and should contain different information than a billable Progress Note.

To Create a Process Note:

- Click Patients > Patient name > Documents tab

- Click the Create Note button.

- From the list that appears, select Psychotherapy Process Note

- Select a recent appointment, or click Create Note for an Unscheduled Appointment

To learn more about creating notes and note writing tools in TherapyNotes, read Create a Note.

Note HeaderThe note header automatically fills in information for the clinician, client, and appointment. To edit information in the note header such as the Note Title or date and time of the appointment, click anywhere on the note header or click Edit in the upper right corner.

Note Content

Note Content is blank text field with no limit to the number of characters you can enter. Use this field for any notes related to the session.

Tip: For future Process Notes, click the History button > Use to pull the text forward and keep your template consistent.

Save Your NoteNote: In order to save a Process Note, you must complete the Process Note field.

Once you have completed your Consultation Note, click the Create Note button. There is no need to sign the note, as you would a Progress Note

Keeping Process Notes Separate from the Clinical Record HIPAA requires that psychotherapy notes be kept separate from the remainder of the clinical record. They also cannot be disclosed without the express authorization from the client except in very limited circumstances. Psychotherapy notes are even exempted from the client's right of access to their record. TherapyNotes makes this easy to do. When you download notes from a client chart, you have the ability to select all notes in their record at once. If the client has any Process Notes, you will see a warning:

If the client has any Process Notes, you will see a warning:

Click the Deselect Process Notes link to remove all Process Notes from your selection, then click the Download Selected Documents button to get a PDF of all the selected notes.

Still need help? Contact Us Contact Us

How to take smart notes — What to read on vc.ru

Key ideas of the unpublished Russian bestseller "How to take smart notes" by writer and scientist Sonke Ahrens from the MakeRight.ru team.

37402 views

The method described by the author of the book, writer and scientist Sonke Ahrens, is called "Zettelkasten" (pronounced "Zettelkasten", sometimes "Zettelkasten" is found). Translated from the German "Zettelkasten" means "file cabinet" or "file cabinet". nine0003

The author of the method is the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann, known for writing more than 70 books and 250 articles during his career. He is also known for creating a systems theory of society, set out in the comprehensive work The Society of Society.

He is also known for creating a systems theory of society, set out in the comprehensive work The Society of Society.

Sonke Ahrens' book regularly ranks in the top 10 Amazon bestsellers in the sections: Learning Skills, Time Management in Business, Scientific Research.

Consider the important ideas of the book.

Idea 1: A new way of organizing notes helped Luhmann achieve impressive results

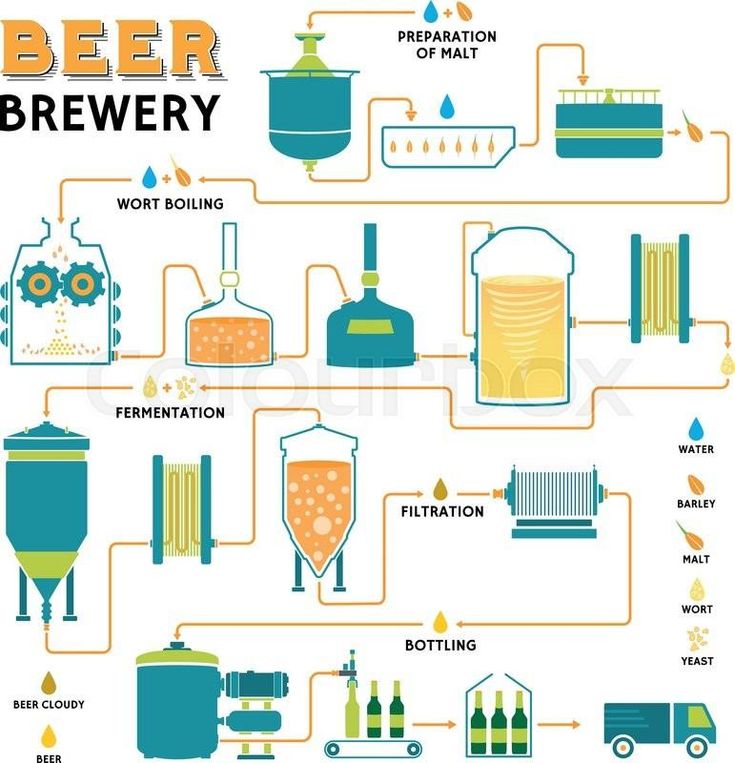

Niklas Luhmann (1927 - 1998), one of the most famous sociologists, was born in the family of a German brewer. He received a law degree, briefly worked as a civil servant, and in the evenings after work read and did research in the fields of sociology, philosophy, and organizational theory.

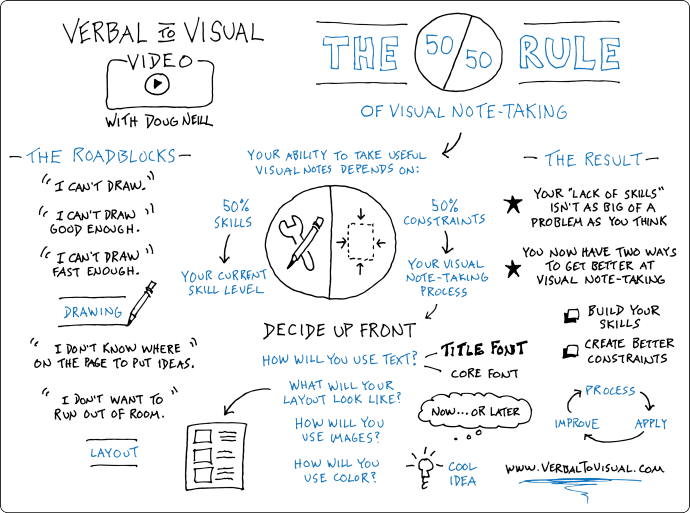

When he came across something remarkable or thought about what he had read, he, like many, made a note, a note, or wrote a comment in the margins of the book. He soon realized that such notes lead to nothing and give nothing - it is impossible to navigate in them, it is very difficult to find the right idea, they remain a scattered set of elements. nine0003

nine0003

He decided to improve the method of taking notes and took the library file as a basis. On a separate card, he wrote down the idea, indicated its source and placed it in a file cabinet. He did not sort the cards alphabetically or by topic, but gave each card a number. He realized that not only the note itself is valuable, but also its context - where the idea was taken from, which ideas complement it, which are connected with it, which develop or refute it.

Notes require a link that is not found in a regular file cabinet, grouped alphabetically or by topic. Luman began to make notes on each card, indicating with which cards it is connected in meaning. When he found an idea that complemented one already in the card file, he placed it behind that card using subnumbering. For example, the original idea was numbered 54, then the complementary idea was numbered 54/1. nine0003

If he found an idea complementary to idea 54/1, he could give it the number 54/1a. His card file of ideas grew over time (it contained about 90 thousand cards), she became his interlocutor, helped him structure and develop his thoughts, and provided him with the necessary information.

Luhmann's method of work contributed significantly to his academic success. When Luhmann gave one of his manuscripts to the renowned sociologist Helmut Schelsky, he was so impressed with it that he contacted Luhmann and offered him a professorship in sociology at the newly founded Bielefeld University. nine0003

However, Luhmann did not have the formal qualifications or doctorate to take up the post. Many would consider the offer flattering, but would reject it due to the lack of a degree. However, Luhmann accepted the offer - in less than a year (largely thanks to his file cabinet) he completed his doctoral and habilitation dissertations and soon became a professor of sociology at the University of Bielefeld.

Luhmann made no secret of his working technique. Moreover, he often explained his productivity with it, but many rejected this explanation, believing that in this way he modestly underestimates his genius. nine0003

Idea 2: Luhmann's method allows you to make connections between ideas, develop chains of thought and work from the bottom up

Luhmann had two file cabinets:

The first one was bibliographic. In it, he placed links to sources and brief notes on the content of the literature he read.

In it, he placed links to sources and brief notes on the content of the literature he read.

The second is the main one. In it, he collected his own ideas that arose in the process of work. He made notes on cards that were stored in wooden boxes. nine0003

Thus, his work consisted of several stages.

When he read something and came up with interesting ideas, he wrote down the bibliographic information on one side of the card and made brief notes revealing the ideas on the other side. These notes were included in the bibliographic card file.

In the second step, he looked through these notes and reflected on their implications for his own work and the development of his own ideas. He then turned to the main card file and wrote down his ideas, comments and thoughts on new sheets of paper, using only one for each idea and limiting himself to one side of the sheet so as not to remove the cards from the box when reading. nine0003

He usually kept his notes short enough to fit one idea on one sheet, but sometimes he added another note to expand on the idea. At the same time, the style of writing was not particularly different from his final works - he wrote down ideas in full and thoughtful sentences. He did not copy the formulations, but explained them in his own words, trying to preserve the original meaning.

At the same time, the style of writing was not particularly different from his final works - he wrote down ideas in full and thoughtful sentences. He did not copy the formulations, but explained them in his own words, trying to preserve the original meaning.

New notes became part of longer note chains, rarely remaining isolated. On cards with ideas, Luhmann indicated the numbers of cards related to them in meaning. Sometimes the connections were obvious, sometimes not so much. nine0003

The main feature of Luhmann's filing cabinet was that he organized his notes not by topic, but rather abstractly, giving them numbers.

The numbers in the numbers had no meaning and were only used to permanently identify each note. If the new note was related to an already existing note, such as a comment or correction, Luhmann would add it immediately after the previous note, giving the number associated with the original one. nine0003

Alternating numbers and letters with slashes and commas between them (for example: 78/12e5a7), he could reflect in the card index the branching of an idea into many chains of thoughts. Adding links to cards is similar to the modern use of hyperlinks on the Internet, however, you should not equate the Luhmann method with a personal Wikipedia - there are similarities, but there are also significant differences.

Adding links to cards is similar to the modern use of hyperlinks on the Internet, however, you should not equate the Luhmann method with a personal Wikipedia - there are similarities, but there are also significant differences.

Links between notes helped Luhmann create different contexts for the same idea. Luhmann did not start with a predetermined order of topics, but took a bottom-up approach, starting with a specific idea as a starting point, expanding, refining, and adjusting it over time. nine0003

Another element of his system was a pointer that helped him navigate through the cards. In it, he indicated the numbers of one or two cards that served as "entry points" to any topic.

Idea 3. To implement the system in your work, you need simple tools

What you need to work with your own file cabinet:

The first thing is something for notes during the day. It can be a pen and a notepad, applications on a smartphone, a voice recorder. nine0003

nine0003

The second is a reference system (analogous to Luhmann's bibliographic card index) for collecting bibliographic data, references and notes that you make while reading.

Third, the file cabinet itself. It can be either a real file cabinet in boxes and on paper, or a program, the principle of which is similar to a file cabinet and which allows you to set links and put down tags (For example: Evernote, zettelkasten.danielluedecke.de). You also need to have a pointer in order to navigate your notes. In it, you can write out card numbers and keywords that refer to them. nine0003

The fourth is a post editor (there are plenty of free options).

How to organize your work with these tools:

- Take quick notes. Always have a notepad or smartphone handy where you can enter an idea and a thought that comes to your mind. It doesn't matter where you take such fleeting notes - they should just be reminders. The only condition is to store or collect them in one place at the end of the day to review and work through for the filing cabinet again.

nine0084

nine0084 - Take literary notes. Every time you read something, make notes about the content of what you read. Write down things you don't want to forget, or things you think you could use to develop your own ideas. Be very concise, selective, and formulate ideas in your own words without copying the text. By formulating an idea in your own words, you improve your own understanding. Keep these records together with the bibliographic data in one place - in your bibliographic file/reference system. nine0084

- Take regular notes. They are intended for your main filing cabinet. Review the notes you made in Step 1 or 2 (preferably daily) and consider how they relate to anything related to your research, reflection, or interests. The Zettelkasten method is not aimed at collecting other people's ideas, but at developing them, formulating one's own, finding arguments, and discussing. Ask yourself questions about whether the new information contradicts what you know, corrects, supports or complements it? Can you combine ideas to create something new? Write only one note for each idea, and state the thought as if you were writing for someone else: use full sentences, disclose your sources, make references, and try to be as precise and concise as possible.

Delete the passing notes from step 1 and place the literary notes from step 2 in your reference system/bibliographic file. nine0084

Delete the passing notes from step 1 and place the literary notes from step 2 in your reference system/bibliographic file. nine0084 - Now add new permanent notes to your main file cabinet:

a) Place each of them behind one or more related notes, giving them the appropriate numbers. If the new note is not directly related to any other note, simply place it behind the last one by giving it a number that is not related to the previous ones.

b Add links to related notes in the new note. Also, additionally, on the cards, you can indicate topics (tags) related to each idea. nine0090 c) Make sure you can find this note later, either by linking to it in your index, or by linking to it in a note that you use as an entry point to a discussion or topic that is itself linked to the index. - Develop your ideas and projects from the bottom up from within the system. Study notes, ask yourself questions about what you are missing to strengthen your arguments.

Do not cling to an idea if another, more promising one is gaining momentum. The more you are interested in something, the more you read and think about it, the more notes you will collect and the more likely you will come up with your own ideas. nine0084

Do not cling to an idea if another, more promising one is gaining momentum. The more you are interested in something, the more you read and think about it, the more notes you will collect and the more likely you will come up with your own ideas. nine0084 - After a while, you will have enough ideas to decide what topic to write about or what project to delve into. Now you do not have abstract ideas about the topic, but a solid foundation. Review the links and collect all relevant notes on this topic, something will need to be clarified, added or, conversely, removed.

- Draft your notes into a logical narrative.

- Edit and proofread your text. nine0084

You can work on several projects at the same time, sticking to this plan and being at different stages of it.

Be flexible. Get in the habit of taking notes on every idea you're interested in, not just the ones you're going to write about or work on. It is unlikely that every text you read will contain exactly the information you were looking for and nothing more.

It is unlikely that every text you read will contain exactly the information you were looking for and nothing more.

Surely in every book or article you will find ideas that you did not expect to see there and that can lead you to interesting thoughts. Take notes on these ideas, and over time you'll build up a critical mass of these "chance encounters" that will help you develop original thoughts. nine0003

Idea 4: An efficiency tool will not work if it is not built into the workflow

With Zettelkasten, it's not so much the technical specifications of your tools that matter, but how well you use them and how well they fit into your workflow. Without this, even the best file cabinet will turn into a cemetery of ideas.

A good structure becomes your second brain - it makes it easier to remember and helps you quickly navigate through large amounts of information. You don't have to keep all the information in your head, it helps you focus on the main thing - ideas, arguments, content. nine0003

nine0003

It also helps to cope with psychological difficulties - procrastination and lack of motivation, the cause of which is often not laziness, but an improperly organized routine. A well-structured, systematized, and organized workflow helps you focus and focus on the right things at the right time.

Structuring work should not be confused with making plans and to-do lists. So, if you have a plan, you impose a structure on yourself, which takes away your flexibility. You need to use willpower and force yourself, as a result you can "step on the throat of your own song" - you can interfere with important reflections. nine0003

When we limit ourselves to plans, we don't see the big picture. A well-organized workflow helps to find unexpected relationships between disciplines, to go beyond limitations, to see the development of one's own knowledge.

What does a well-organized work process mean? This may seem like something complicated, but the Zettelkasten system is based on a few simple principles. Even dealing with complex information can rely on a simple system. Many people try to break complex topics into small pieces and put them in separate folders. But what seems less complex becomes more complex over time. nine0003

Even dealing with complex information can rely on a simple system. Many people try to break complex topics into small pieces and put them in separate folders. But what seems less complex becomes more complex over time. nine0003

The workflow becomes more complex: some remain underlined in books, some remain jotted down in notepads, some are memorized with acronyms, some are stored in a wide variety of productivity programs and applications. So the workflow quickly turns into a mess. When you encounter a new idea, you can't make connections between it and the ideas you already know because they can't be found. You are unlikely to be able to look through all your books, notes, applications and notebooks to find these connections. nine0003

The filing cabinet is not just another efficiency tool, but part of a comprehensive workflow that directs attention to what matters.

Good tools don't add features or extras to what we already have, but they help reduce distractions. A filing cabinet provides an external framework for thinking and helps store information, something our brains aren't very good at.

A filing cabinet provides an external framework for thinking and helps store information, something our brains aren't very good at.

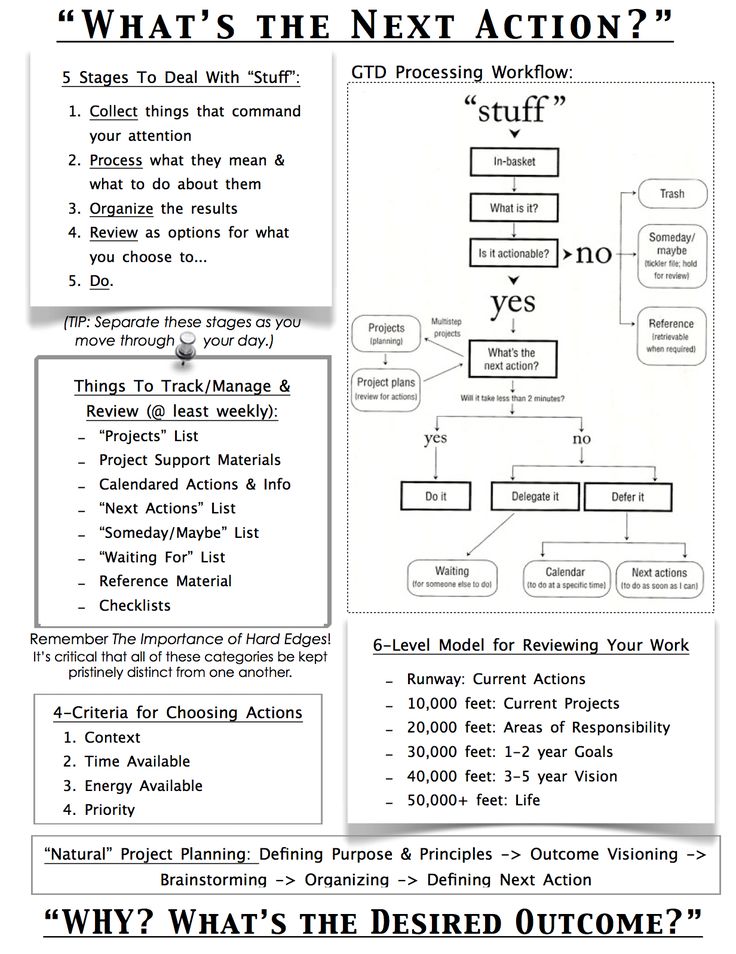

David Allen wrote about the importance of a well-organized workflow in his bestselling book Getting Things Done (GTD). He pointed out that only if nothing overloads our working memory and takes away valuable attentional resources can we enter a state of focus when we are truly productive. nine0003

The source of most distractions is not so much in our environment as in ourselves, in our own mind. It's a simple but holistic principle that we can use to create a support system for our day-to-day work, to unburden the mind and direct attention to what's most important.

However, the GTD methodology is designed primarily to work towards well-defined goals, where the project can be divided into sequential steps. But many projects, creative work, and writing are not linear—they start with vague, vague ideas that become clearer through exploration. In such work, it is extremely difficult to determine the sequence of steps, it is a non-linear process - we constantly jump back and forth, from important to insignificant. nine0003

In such work, it is extremely difficult to determine the sequence of steps, it is a non-linear process - we constantly jump back and forth, from important to insignificant. nine0003

This is why the GTD method is not used in academia, although it is effective in business. Nevertheless, the idea of the importance of a holistic perspective can be borrowed from it. Even the best tools will not work if they are used in isolation and are not built into the workflow on an ongoing basis. Zettelkasten is not only a tool for organizing notes, but also a whole philosophy of productive work and development of thinking.

Idea 5. The Zettelkasten system is based on several principles

An important principle is simplicity.

It's hard to believe that something as simple as a filing cabinet can have a significant impact on your workflow. Intuitively, most people don't expect much from simple ideas. They believe that impressive achievements are the result of the use of impressively complex means. In addition, they tend to view the filing cabinet as separate from the workflow of which it is a part.

In addition, they tend to view the filing cabinet as separate from the workflow of which it is a part.

However, simple tools can lead to amazingly large and outstanding results. The author gives the example of Malcolm McLean, an entrepreneur and former trucker who was fed up with traffic jams and wanted to improve trucking. The delivery of goods at the beginning of the 20th century was extremely complex and expensive, and at the same time did not guarantee the integrity of the cargo - the cargo was placed in bags, barrels and boxes, they were often lost, stolen and damaged on ships. Naturally, imported goods were very expensive. nine0003

McLean re-engineered the entire industry with a very simple solution: the unified freight container for transporting goods.

The author compares Luhmann's filing cabinet with McLean's shipping container. Just as different products are loaded into a uniform container, a file cabinet standardizes the format for storing ideas. It all comes down to one principle of organization. But just as McLean's solution wouldn't work without the right infrastructure, Luhmann's filing cabinet should be part of the daily workflow. nine0003

But just as McLean's solution wouldn't work without the right infrastructure, Luhmann's filing cabinet should be part of the daily workflow. nine0003

Another principle of the method is intrinsic reward. In the process of work, you do not enjoy external rewards, but from the awareness of improving your thinking and improving your skills. External rewards have a danger - they force you to fall into a vicious circle of short-term decisions.

With Zettelkasten you become a fan of your work, you don't have to come up with incentives to stay focused, it just happens. Work becomes more enjoyable than distractions. nine0003

Another principle of the system is the importance of writing. Written work is understood not as a task separated from other research processes, but as a part of the research itself, as a means of organizing thinking, memorization and research. Therefore, while learning to write, we are simultaneously learning the process of research.

The next principle is that you don't start from scratch. One often sees advice in work organization manuals to define a narrow topic for yourself, clearly formulate questions for research, and plan steps. But research, creative work cannot be so linear. To formulate a good question or find a narrow topic for research, you need to think well about the topic. To decide on a topic, you need to read quite a lot of information on different topics. nine0003

The decision to read one and not the other is also based on understanding and previous work. The new intellectual effort builds on the intellectual work already done, you don't start from scratch. When working with Zettelkasten, you start from what you know and what interests you. In the course of work, your knowledge increases, you move on to other topics, gain experience, improve understanding, find ideas for narrower research. Also, this approach helps you to notice your bias and not fall into mental traps, you remain open to the new. nine0003

nine0003

Idea 6. To make the system work, formulate ideas only in your own words, develop them and take into account the principle of interconnectedness

In the Zettelkasten note-taking process, you practice the skill of highlighting important information from less relevant information every day. Revealing the essence of the text for scientists and writers is the same as the daily training of movements for the athlete.

With practice, you improve your ability to recognize patterns and become a pro: you can read faster, grasp things faster and better, and train your thinking at the same time. There were 9 in Luhmann's file cabinet0 thousand cards. This seems like a huge number, but if you divide it by the years of his active work, it turns out that this is only 6 cards a day. Luhmann's notes are very capacious and concise at the same time.

By writing in your own words every day, you train your ability to find simple, but not simplistic, formulations. When you try to formulate an idea in your own words, you find gaps in your understanding, you find out what knowledge you lack. Such efforts are extremely beneficial for learning. By making an effort to master the material, you increase the likelihood that it will be well deposited in your memory. nine0003

When you try to formulate an idea in your own words, you find gaps in your understanding, you find out what knowledge you lack. Such efforts are extremely beneficial for learning. By making an effort to master the material, you increase the likelihood that it will be well deposited in your memory. nine0003

An extremely important principle of the system is interconnectedness. Luhmann's filing cabinet is not just a collection of notes. Working with it is not only obtaining specific information, but searching for relationships. The author cites a study by psychologist Kirsty Lonka, who compared the reading approach of the most successful doctoral students and students with those who were far less successful. A critical difference was discovered: the ability to think outside the given framework of the text.

Experienced readers usually read a text with a series of questions. They try to relate the new text to other texts, while inexperienced readers tend to take the text and its author's argument for granted, too literally. Good readers notice the limitations of a text and reflect on what it doesn't mention. They go beyond the frame. nine0003

Good readers notice the limitations of a text and reflect on what it doesn't mention. They go beyond the frame. nine0003

Another common problem for a poor reader is the inability to interpret specific information in a text within a larger context or argument. Such reading is simply a collection of scattered quotations, which is very far from a deep understanding of the meaning of information, its context and the boundaries of this context, without which it is impossible to comprehend the information. Lonka recommends what Luhmann recommended: writing brief summaries of the main ideas of the text instead of writing out quotations.

It is equally important to do something with these ideas - to think about how they are related to other ideas, whether they can answer questions from other authors. In fact, this is exactly what we do when we formulate permanent notes and add them to the file cabinet: we think about the meaning of an idea and relate it to other ideas by placing it in different contexts.

Such connections become a self-sustaining network of interconnected ideas and facts that mutually reinforce each other. The lack of sorting the card index by topic is an advantage. It helps to actively establish links between notes, better remember information by placing it in different contexts. nine0003

Free numbering of notes helps to develop ideas, freely change course when necessary. Notes are only as valuable as the relationships they are embedded in.

The file cabinet is not an encyclopedia, but a tool for reflection, so there is no need to worry about its completeness. You should only write if it helps develop a line of thought that interests you. You can take care of the gaps in the arguments already when preparing the final version of your text or project. nine0003

Organizing information according to the Zettelkasten principle helps you think creatively about ideas. As you look through your notes, you may recall long forgotten ideas and find unexpected connections between them. You do not tie ideas to one context, but immerse them in different ones.

You do not tie ideas to one context, but immerse them in different ones.

At the same time, information does not turn into a chaos that is impossible to understand - the system assumes a number of restrictions that also contribute to creativity. So, your notes should be concise and not exceed the length of a couple of sentences, all information should be organized in accordance with several basic principles, the type of notes should be unified. nine0003

Idea 7: Avoid common mistakes when creating your own filing cabinet

The first mistake is mixing notes of different types with each other. This often happens with diligent students who do not want to lose a single worthwhile idea and write everything down in a notebook. However, this approach has serious drawbacks: each new note is treated as belonging to the “permanent” category, which makes it difficult to gain a “critical mass” of quality notes and highlight really worthwhile ideas among the many secondary or those that are relevant only to a particular project. In addition, the strict chronological order of entries makes it difficult to create links between notes. nine0003

In addition, the strict chronological order of entries makes it difficult to create links between notes. nine0003

To achieve a critical mass of quality ideas, it is essential to clearly distinguish between three types of notes:

The first is fleeting notes that serve only as a reminder of information. They can be written in any way, they need to be disposed of after processing.

The second is permanent notes that are never thrown away and contain the necessary information in an accessible form. They are always stored in the same place either in the bibliographic card index or in the main card index. nine0003

The third one is notes related to one specific project only. They should be stored in a project-specific folder that can be deleted or archived after the project is completed.

Keep all three types of records separately, without mixing them together.

The second typical mistake: to collect notes only about a specific project, cutting off everything else. At first glance, this seems reasonable. You decide what you will write about, and then collect everything that will help you with this. But after the completion of each new project, you have to start all over again, you lose ideas that were not related to a specific project. At the same time, if you, not wanting to lose ideas, start your own folder for each future project, you can get bogged down in a huge number of unfinished projects and lose motivation to work. You need a supply of ideas, but it is important that they are conveniently organized. nine0003

At first glance, this seems reasonable. You decide what you will write about, and then collect everything that will help you with this. But after the completion of each new project, you have to start all over again, you lose ideas that were not related to a specific project. At the same time, if you, not wanting to lose ideas, start your own folder for each future project, you can get bogged down in a huge number of unfinished projects and lose motivation to work. You need a supply of ideas, but it is important that they are conveniently organized. nine0003

The third common mistake is to treat all notes as fleeting. With this approach, a person is buried in the chaos of records and materials. The more disorganized notes that surround you, the more you'll want to spit on everything and start from scratch.

All of the above erroneous approaches have in common that the benefit of taking notes decreases with an increase in their number. The Zettelkasten method is the opposite - the more notes you have, the more useful they become, the more ideas you get, the easier it is for you to work. nine0003

nine0003

***

Books on efficiency and organization give advice on the importance of taking notes, but little emphasis on how to take notes. In his book, Sonke Ahrens shows the importance of note-taking.

The system developed by Niklas Luhmann is based on two simple ideas:

The first one is the organization according to the card file method (taking into account digital numbering).

Second, even the best tool won't improve your productivity unless you change your daily routine to incorporate this tool into it. The tool should become part of your workflow. nine0003

Things to do for those who are interested in the book's ideas:

— Get into the habit of keeping quick notes and reviewing them regularly to decide which ones deserve special attention;

- Choose a tool for organizing your own file cabinet: a program or a regular file cabinet;

— Create two file cabinets for permanent records: a bibliographic (reference) one, where you need to write down ideas from the literature and their source, and a main one, where you need to enter your own ideas born in the process of thinking or reading; nine0003

Formulate ideas for permanent entries in your own words only;

- Use digital numbering, put down links between notes;

- Keep an index to navigate your notes, putting in it the numbers of notes and keywords for them;

- Periodically review your notes for ideas and unexpected connections between them.

Organize! Why taking notes is the easiest way to beat procrastination and become super productive

Switch

In 1968, the son of a brewer from the small German town of Lüneburg, Niklas Luhmann, was invited to the position of professor of sociology at the University of Bielefeld. He had neither the special education nor the scientific publications necessary for this work. However, he was very fond of reading and ... took notes. The system of fixing and storing information developed by him formed the basis of Luhmann's sociological theory. This system will help you cope with procrastination, no matter who you are and what you do - study at the university, write articles or just read books and study interesting information. In November, Mann, Ivanov & Ferber publishes Zonke Ahrens' book How to Take Useful Notes on how to learn how to use this system. Inc. Russia publishes an excerpt. nine0257

Inc. Russia publishes an excerpt. nine0257

Until now, writing techniques have been taught without regard to the overall workflow. This book will provide you with the note-taking tools that turned the brewer's son into one of the most productive and respected sociologists of the 20th century. It describes how he incorporated notes into his work so he could honestly say, “I never force myself to do anything I don’t feel like doing. Whenever I get stuck, I switch to something else." A good system allows you to seamlessly transition from one task to another without compromising the organization of the entire process or losing sight of the big picture. nine0003

A good system is something you can rely on. It relieves you of the burden of remembering and keeping track of everything and everything. If you trust the system, you can stop trying to keep everything in your head and focus on what really matters: content, arguments, and ideas. By breaking down an abstract task like “writing an article” into small and clearly separated subtasks, you can focus on one thing, get it done in one sitting, and move on to the next one. A good system provides a certain state in which you are so immersed in your work that you lose track of time and do not even notice that you have stopped making any effort. Something like this does not happen by itself. nine0003

By breaking down an abstract task like “writing an article” into small and clearly separated subtasks, you can focus on one thing, get it done in one sitting, and move on to the next one. A good system provides a certain state in which you are so immersed in your work that you lose track of time and do not even notice that you have stopped making any effort. Something like this does not happen by itself. nine0003

As students, researchers, and nonfiction writers, we have much more freedom than others to choose how we want to spend our time. However, we are often the ones most prone to procrastination and motivation problems. The fault, of course, is not the lack of interesting topics, but the use of unsuccessful tools that confuse us instead of directing the process in the right direction. A good structured workflow gets us back on track and empowers us to do the right thing at the right time. nine0003

Having a clear system to work with is completely different from just planning. When you make a plan, you impose a system on yourself - this deprives you of flexibility. To keep going according to plan, you have to push yourself and use willpower. This is not only demotivating, but it is also not suitable for an open and unpredictable process, such as research, thinking or learning in general. In them, we must adjust the next steps with each new idea, insight or achievement, which ideally appears regularly, and not as an exception. While planning often goes against the very idea of research and learning, this is the mantra of most academic writing textbooks and books. nine0003

When you make a plan, you impose a system on yourself - this deprives you of flexibility. To keep going according to plan, you have to push yourself and use willpower. This is not only demotivating, but it is also not suitable for an open and unpredictable process, such as research, thinking or learning in general. In them, we must adjust the next steps with each new idea, insight or achievement, which ideally appears regularly, and not as an exception. While planning often goes against the very idea of research and learning, this is the mantra of most academic writing textbooks and books. nine0003

How can you plan for a moment of insight that, by definition, cannot be foreseen? It is completely wrong to believe that the only alternative to planning is aimless doing nothing. The challenge is to structure the workflow in a way that allows sudden ideas and moments of inspiration to become the driving force that pushes us forward. We do not need to make ourselves dependent on a plan that fears such surprises.

Unfortunately, even universities try to turn students into planners. Of course, a good plan will help you succeed in your exams if you stick to it. But this does not make you an expert in the art of cognition / writing / note-taking (see 1.3 for research on this topic). Planners are also unlikely to continue their studies after completing their exams. They'd rather be glad it's over. But experts would not even think of voluntarily giving up what has become useful and exciting: learning in a way that develops insight, inventing and accumulating new ideas. The fact that you have purchased this book tells me that you want to be an expert rather than a planner. nine0003

And if you're a student who wants to learn how to write well, chances are you already set high goals for yourself, because usually the best students suffer the most. They fight for a long time with their own proposals, because it is important for them to find the exact expression. They need more time to find a good idea to write about because they know from experience that the first thought is rarely the best and topics don't just fall into their hands.

They need more time to find a good idea to write about because they know from experience that the first thought is rarely the best and topics don't just fall into their hands.

They spend more time in the library to become more familiar with the literature, they read more, which means they have to manipulate more information. Reading more does not automatically mean having more ideas, especially at the beginning. It just means you'll have even fewer ideas to work with because you know others have already thought of most of them. nine0003

Good students also look beyond the obvious. They peek out from behind the boundaries of their subject - and once they do, they can no longer go back and do the same thing that everyone else is doing. And even if now they have to deal with the most heterogeneous ideas, there are no instructions on how to connect them with each other. All this means that some kind of system is needed to keep track of the ever-increasing amount of information that will allow you to intelligently combine different ideas in order to generate new ones. nine0003

nine0003

Weak students have none of these problems. As long as they stick to the boundaries of their subject and read only as much as they are told (or less), no serious external system is required, and writing can be done by adhering to the usual formulas "how to write a scientific paper." In fact, weak learners often feel more successful (until they get to the real test) because they rarely doubt themselves. In psychology, this is called the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Weak students lack understanding of their own limitations - for this they would need to learn about the vast amount of knowledge that they do not have in order to see how little they know. This means that those who are not very good at something tend to be overconfident, while those who put in some effort tend to underestimate their abilities. It is also not difficult for weak students to find a topic to write about: they do not doubt their opinion and are sure that they have everything under control. They will also have no problem finding evidence in the literature, as they usually lack the interest and skills to find and work with disproving facts. nine0003

They will also have no problem finding evidence in the literature, as they usually lack the interest and skills to find and work with disproving facts. nine0003

On the other hand, good students constantly raise the bar by focusing on what they haven't learned yet and what they haven't mastered yet. This is why successful people who have achieved a vast amount of knowledge can suffer from what psychologists call the impostor syndrome - the feeling that you are not doing a job when it is quite the opposite [14, 24]. This book is for you good students, ambitious scientists, and curious non-fiction writers who understand that inspiration doesn't come easily and that writing is not only a vehicle for expressing an opinion, but also a major tool for achieving knowledge worth sharing. nine0003

Good solutions are simple and unexpected

There is no need to create a complex system and reorganize what you already have. You can start working and developing ideas right now by making useful notes.

You can start working and developing ideas right now by making useful notes.

However, it's all about complexity. Even if your goal is not to develop a grand theory, but simply to keep track of what you read, organize your notes and be able to develop thoughts, you will have to deal with more and more complex content, especially since we will not just be talking about collecting thoughts. but about establishing a system of connections that would ignite all new ideas. Most people try to make things easier by sorting what they have into smaller piles, stacks, or individual folders. They organize their notes into topics and subtopics, and now the notes look less complicated, but at the same time become very confusing. In addition, it reduces the likelihood of building and discovering unexpected relationships between the notes themselves, and this already means a trade-off between usability and usefulness. nine0003

Fortunately, we don't have to choose between usability and usefulness. On the contrary, the best way to deal with complexity is to keep things as simple as possible and follow a few basic principles. The simplicity of the system allows us to create complexity where we want it: at the level of content. There is a fairly extensive empirical and scientific study of this phenomenon. Taking useful notes is as easy as it gets.

On the contrary, the best way to deal with complexity is to keep things as simple as possible and follow a few basic principles. The simplicity of the system allows us to create complexity where we want it: at the level of content. There is a fairly extensive empirical and scientific study of this phenomenon. Taking useful notes is as easy as it gets.

Another piece of good news is how much time and effort you have to put into getting started. Although you will significantly change the way you read, take notes, and write, it will take almost no time to prepare (other than understanding the principle and installing one or two programs if you are going to act digitally). This is not about redoing everything you did before, but about what will change in work from now on. In fact, there is no need to reorganize what is already there. It’s just that now you will begin to approach things differently that you would have done anyway. nine0003

And some more good news. There is no need to reinvent the wheel. It is enough to combine two well-known and proven ideas. This book is based on the first idea, the simple note box technique. I will explain the principle of this system in the next chapter and show how it can be applied in everyday life. Fortunately, the applications and programs we need for all major operating systems already exist, but you can use pen and paper if you wish. In terms of performance and simplicity, you still easily outperform those who take not-very-useful notes. nine0003

There is no need to reinvent the wheel. It is enough to combine two well-known and proven ideas. This book is based on the first idea, the simple note box technique. I will explain the principle of this system in the next chapter and show how it can be applied in everyday life. Fortunately, the applications and programs we need for all major operating systems already exist, but you can use pen and paper if you wish. In terms of performance and simplicity, you still easily outperform those who take not-very-useful notes. nine0003

The second idea is equally important. Even the best tool won't improve your productivity if you don't change the daily routine that the tool is built into, just like the fastest car can't help you if there aren't roads to suit it. Like any change in behavior, changing work habits means going through a phase where you will be drawn to old habits. At first, the new way of working may seem artificial and very different from what you would intuitively do. This is fine. But once you get into the habit of taking helpful notes, it becomes so natural that you'll wonder how you could have done it differently before. Routine operations require simple, repeatable tasks that can be automated and fit together like puzzle pieces. When this becomes part of an overarching and interconnected process that eliminates dangerous spots, only then can significant change occur (which is why none of the typical "10 Mind-blowing Tools to Boost Your Productivity" that you can find on the Internet will ever work). nine0003

This is fine. But once you get into the habit of taking helpful notes, it becomes so natural that you'll wonder how you could have done it differently before. Routine operations require simple, repeatable tasks that can be automated and fit together like puzzle pieces. When this becomes part of an overarching and interconnected process that eliminates dangerous spots, only then can significant change occur (which is why none of the typical "10 Mind-blowing Tools to Boost Your Productivity" that you can find on the Internet will ever work). nine0003

The importance of a shared workflow is a great idea from David Allen's Getting Things Done. Few serious knowledge workers have not heard of the David Allen Principle, and for good reason: it works. It is about gathering everything that needs to be done in one place and dealing with it in one standard way. We don't necessarily have to actually do everything we've ever set out to do in one go, but this method forces us to make clear choices and check regularly to see if our tasks fit into the big picture. Only if we know that we have put everything in order, from the important to the mundane, can we stop thinking about them and focus on what is right in front of us. Only if nothing dangles in our working memory and takes away valuable mental resources can we experience what Allen calls "mind like water" - a state in which focusing on exactly the work that you are doing now does not distracted by unnecessary thoughts. The principle is simple, but holistic. It's not a quick fix just to patch things up, it's not a loud but empty name. nine0003

Only if we know that we have put everything in order, from the important to the mundane, can we stop thinking about them and focus on what is right in front of us. Only if nothing dangles in our working memory and takes away valuable mental resources can we experience what Allen calls "mind like water" - a state in which focusing on exactly the work that you are doing now does not distracted by unnecessary thoughts. The principle is simple, but holistic. It's not a quick fix just to patch things up, it's not a loud but empty name. nine0003

This principle does not work for you. But it does provide a system for day-to-day work that helps deal with the fact that most distractions come not so much from our environment as from our own minds.

Unfortunately, David Allen's technique cannot simply be transferred to useful notes. The first reason is that his principle rests on well-defined ends, while ideas cannot be such in principle. We usually start with rather vague ideas that are destined to change and become clearer as we explore. Therefore, writing aimed at generating an idea should be organized much more flexibly. Another reason is that the Allen principle requires projects to be broken down into small, specific “next steps.” Of course, whether you write down a thought that suddenly came to you or write a scientific work, you also go through a number of stages, but most often they are too small to be worth fixing (search for a footnote, reread a chapter, write a paragraph), or too grandiose to be able to finish in one go. In addition, it is difficult to predict what step to take next. You may have noticed a footnote that needs to be checked. You are trying to understand a paragraph and you need to dig into books for clarification. You take a note, go back to reading, and then jump up and down to write down the sentence that suddenly formed in your head. nine0003

We usually start with rather vague ideas that are destined to change and become clearer as we explore. Therefore, writing aimed at generating an idea should be organized much more flexibly. Another reason is that the Allen principle requires projects to be broken down into small, specific “next steps.” Of course, whether you write down a thought that suddenly came to you or write a scientific work, you also go through a number of stages, but most often they are too small to be worth fixing (search for a footnote, reread a chapter, write a paragraph), or too grandiose to be able to finish in one go. In addition, it is difficult to predict what step to take next. You may have noticed a footnote that needs to be checked. You are trying to understand a paragraph and you need to dig into books for clarification. You take a note, go back to reading, and then jump up and down to write down the sentence that suddenly formed in your head. nine0003

Writing is not a linear process. We constantly have to switch between different tasks. It is pointless to try to manage yourself at this level. If we look at this process more broadly, that doesn't help either, because then you move on to the next steps, such as "write the page." This does not help at all to figure out what needs to be done to write a page. Often this is a whole set of other actions that can take an hour or a month. And you have to navigate mainly by eye. These are probably the reasons why Allen's principle has never been widely accepted in scientific circles, although it is very successful in business and enjoys a good reputation among businessmen. nine0003

We constantly have to switch between different tasks. It is pointless to try to manage yourself at this level. If we look at this process more broadly, that doesn't help either, because then you move on to the next steps, such as "write the page." This does not help at all to figure out what needs to be done to write a page. Often this is a whole set of other actions that can take an hour or a month. And you have to navigate mainly by eye. These are probably the reasons why Allen's principle has never been widely accepted in scientific circles, although it is very successful in business and enjoys a good reputation among businessmen. nine0003

We can learn from Allen's book an important insight that the secret to successful organization lies in a holistic perspective. Every thing needs to be taken care of, otherwise, neglected and forgotten, they will draw energy from you until they suddenly become urgent and you take care of them. Even the best tools won't make much difference if used in isolation. Tools can only show their strengths if they are built into a well-designed workflow. And what's the point of them if they don't fit together? nine0003

Tools can only show their strengths if they are built into a well-designed workflow. And what's the point of them if they don't fit together? nine0003

When it comes to the writing process, everything from information retrieval to proofreading is intimately connected. All small steps should follow each other in such a way that you can seamlessly move from one task to another, but at the same time remain independent enough to be able to flexibly change what needs to be done in a particular situation. And this is another David Allen concept: if you trust your system, only if you really know that everything will go smoothly, your brain will relax and allow you to focus on the current task. nine0003

That's why we need a system as comprehensive as Allen's, but one that is suitable for such a flexible process of writing, learning and thinking. And here the note box will help us.

Note box

Sixties somewhere in Germany. Among the employees of the German administration is the son of a brewer. His name is Niklas Luhmann. He went to law school but decided to become a civil servant because he didn't like the idea of working for several clients at once. Fully aware that he is not suitable for a career in administration, as it requires interaction with a large number of people, every day after the work shift from nine to five, Luman goes home and does what he really likes: reading and devoting himself to his various interests in philosophy, organization theory and sociology. Every time he came across something particularly interesting or had an idea about what he had read, he made a note. Now many people read in the evenings and do something interesting, and some even take notes. But for very few people this path will lead to the same unusual result that Luhmann came to. nine0003

Among the employees of the German administration is the son of a brewer. His name is Niklas Luhmann. He went to law school but decided to become a civil servant because he didn't like the idea of working for several clients at once. Fully aware that he is not suitable for a career in administration, as it requires interaction with a large number of people, every day after the work shift from nine to five, Luman goes home and does what he really likes: reading and devoting himself to his various interests in philosophy, organization theory and sociology. Every time he came across something particularly interesting or had an idea about what he had read, he made a note. Now many people read in the evenings and do something interesting, and some even take notes. But for very few people this path will lead to the same unusual result that Luhmann came to. nine0003

For a while, Luhmann collected notes in the same manner that most people do: writing in the margins or arranging them by topic. And then he realized that this was going nowhere, so he turned the organization of the notes on its head. Instead of adding notes to pre-existing categories or related texts, he wrote each note on a separate little piece of paper, put a number in the corner, and collected them all in one place: a note box.

And then he realized that this was going nowhere, so he turned the organization of the notes on its head. Instead of adding notes to pre-existing categories or related texts, he wrote each note on a separate little piece of paper, put a number in the corner, and collected them all in one place: a note box.

Luhmann soon developed new categories for these notes. He realized that one idea, one note is as valuable as its context, but it is not necessarily the one from which it is taken. So Luhmann began to think about how one idea could relate to different contexts and contribute to their development. Simply accumulating notes in one place would not lead to anything, so he began to collect his notes in a certain way. The box became his dialogue partner, main idea generator, and productivity engine. This helped him structure and develop his thoughts. And the box was interesting to work with - because it really worked. nine0003

And brought Luhmann to the scientific world. One day he compiled some of his thoughts into a manuscript and handed it over to Helmut Schelsky, one of Germany's most influential sociologists. Shchelsky took the manuscript home, read what an outsider of the scientific world had written, and contacted Luhmann. He invited him to become a professor of sociology at the newly founded Bielefeld University. As attractive and prestigious as this position was, Luhmann was not a sociologist. He did not even have the formal qualifications to become an assistant professor of sociology in Germany. He did not go through the process of obtaining habilitation, the highest academic qualification in many European countries (a degree that follows a doctoral degree. - Approx. Per.), which consists in preparing a second post-doctoral scientific qualification work. He did not have a doctorate or even a degree in sociology. Most people would take this offer as a very flattering compliment, but they would not be able to accept it and continue to live their lives.

One day he compiled some of his thoughts into a manuscript and handed it over to Helmut Schelsky, one of Germany's most influential sociologists. Shchelsky took the manuscript home, read what an outsider of the scientific world had written, and contacted Luhmann. He invited him to become a professor of sociology at the newly founded Bielefeld University. As attractive and prestigious as this position was, Luhmann was not a sociologist. He did not even have the formal qualifications to become an assistant professor of sociology in Germany. He did not go through the process of obtaining habilitation, the highest academic qualification in many European countries (a degree that follows a doctoral degree. - Approx. Per.), which consists in preparing a second post-doctoral scientific qualification work. He did not have a doctorate or even a degree in sociology. Most people would take this offer as a very flattering compliment, but they would not be able to accept it and continue to live their lives. nine0003

nine0003