Over diagnosing mental illness

The Problem With Overdiagnosis in Psychiatry

At PCH, we witness the problems caused by overdiagnosing mental issues on a daily basis. Here’s what those problems look like and what we’re doing to solve them.

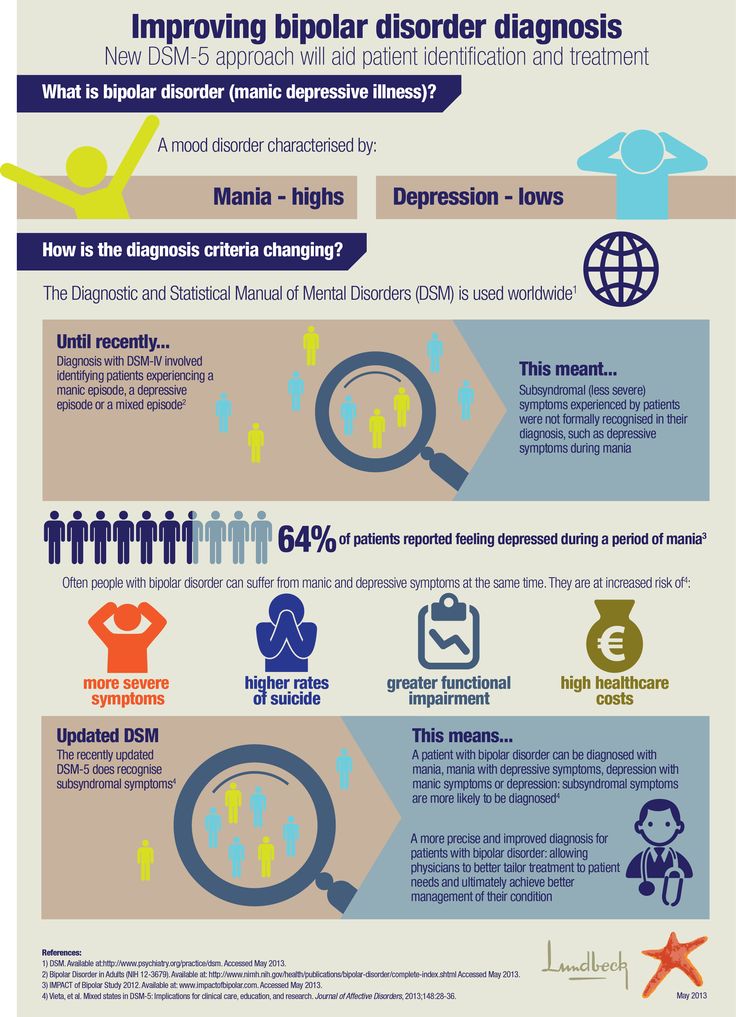

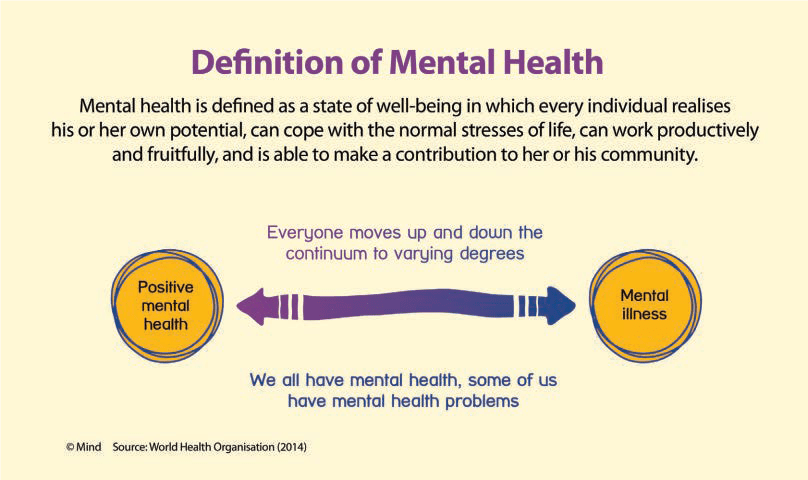

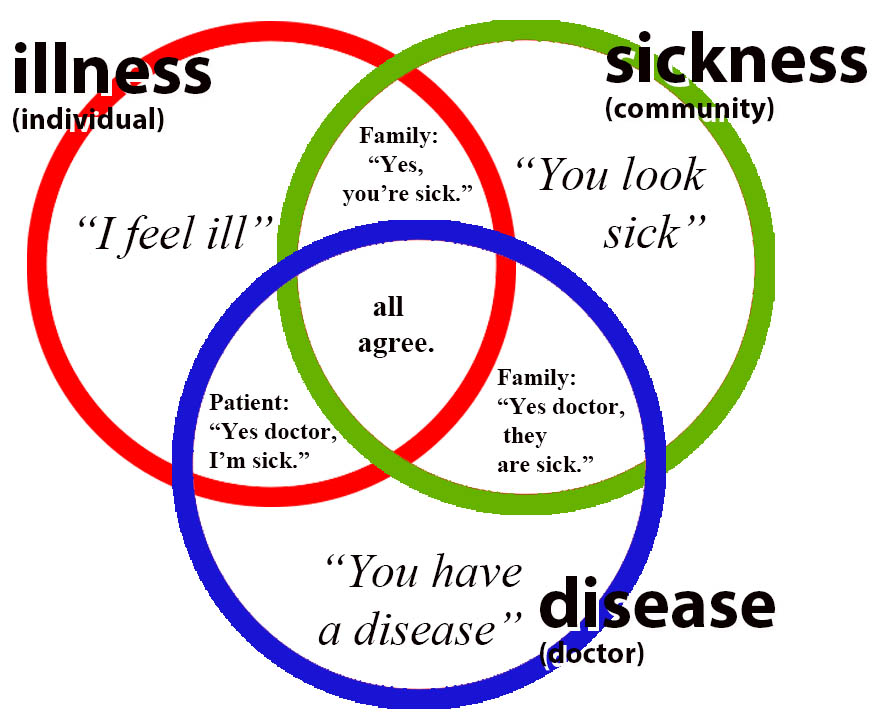

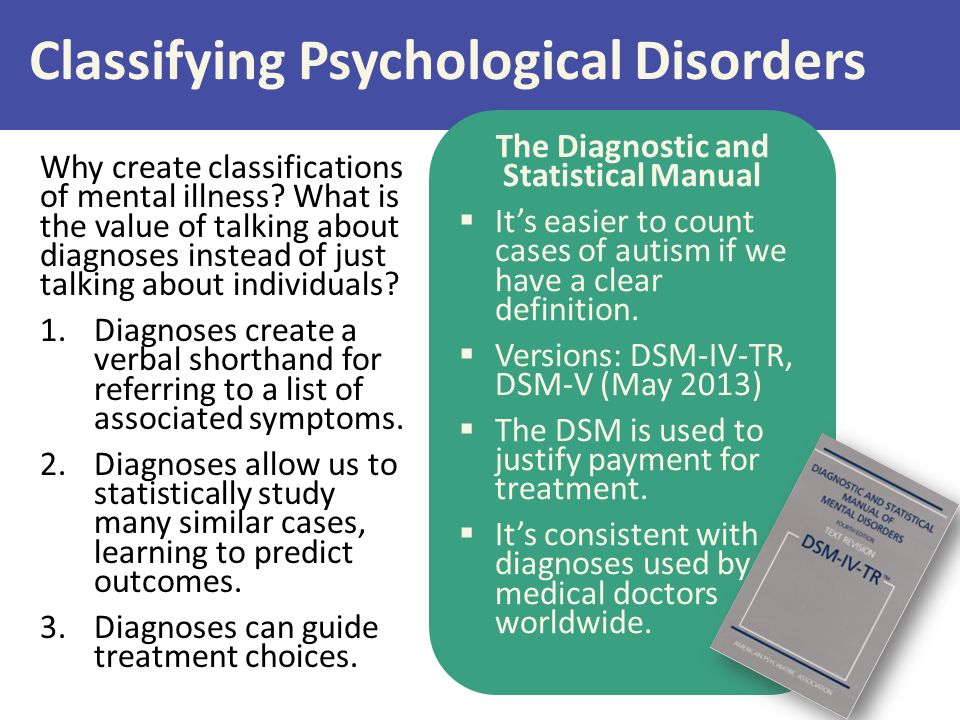

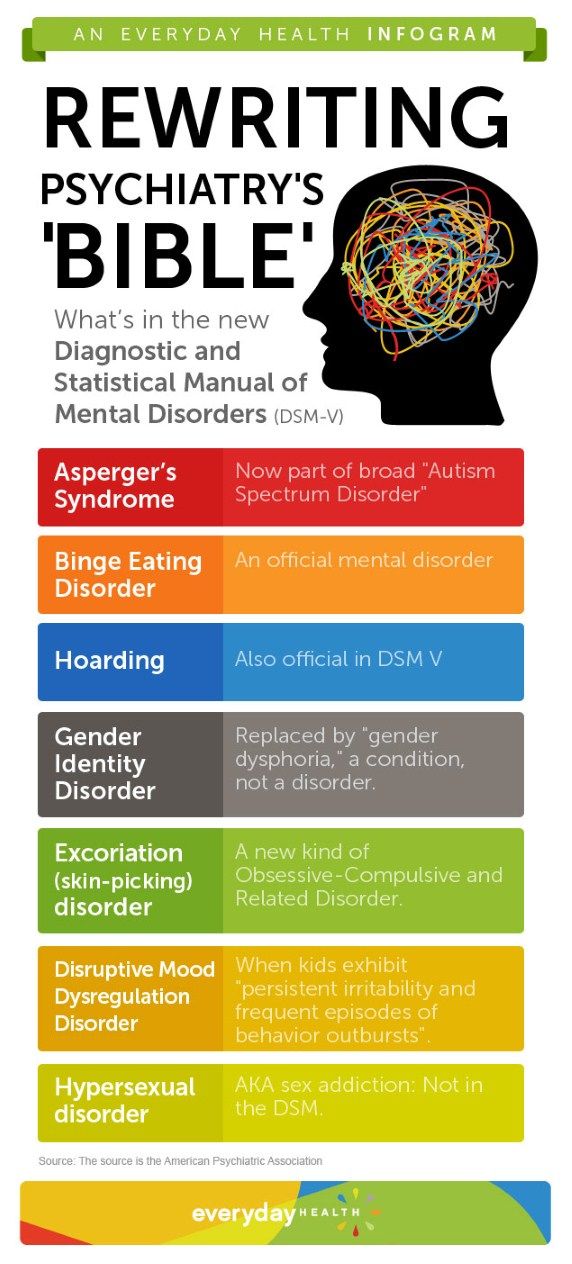

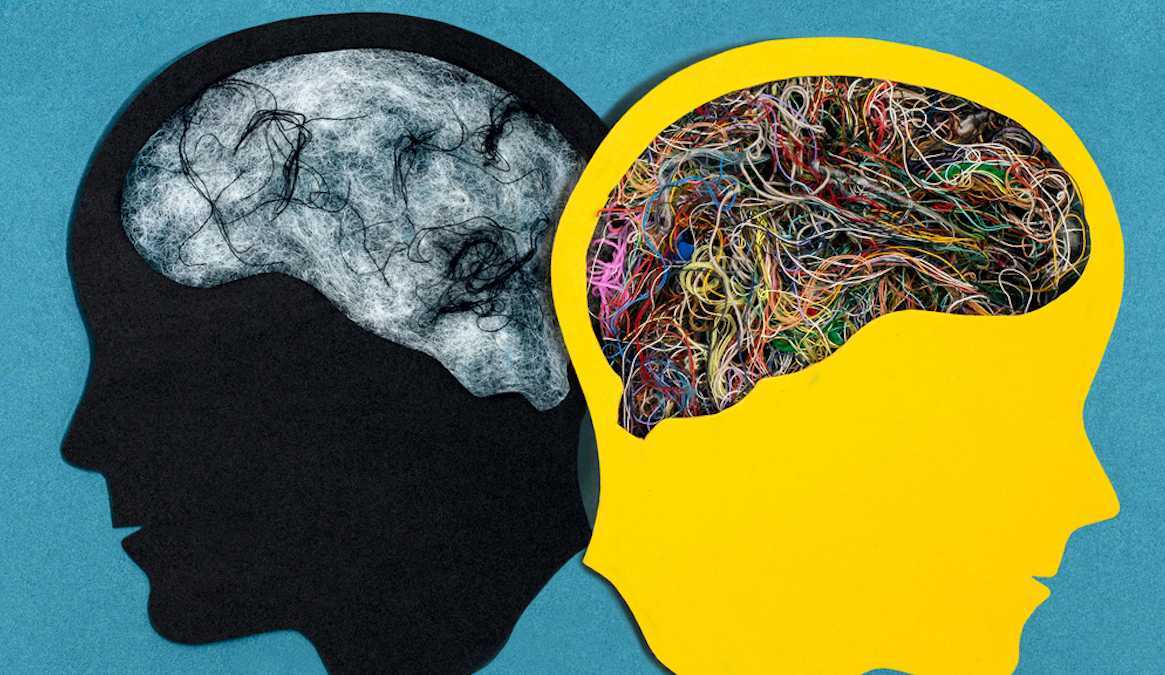

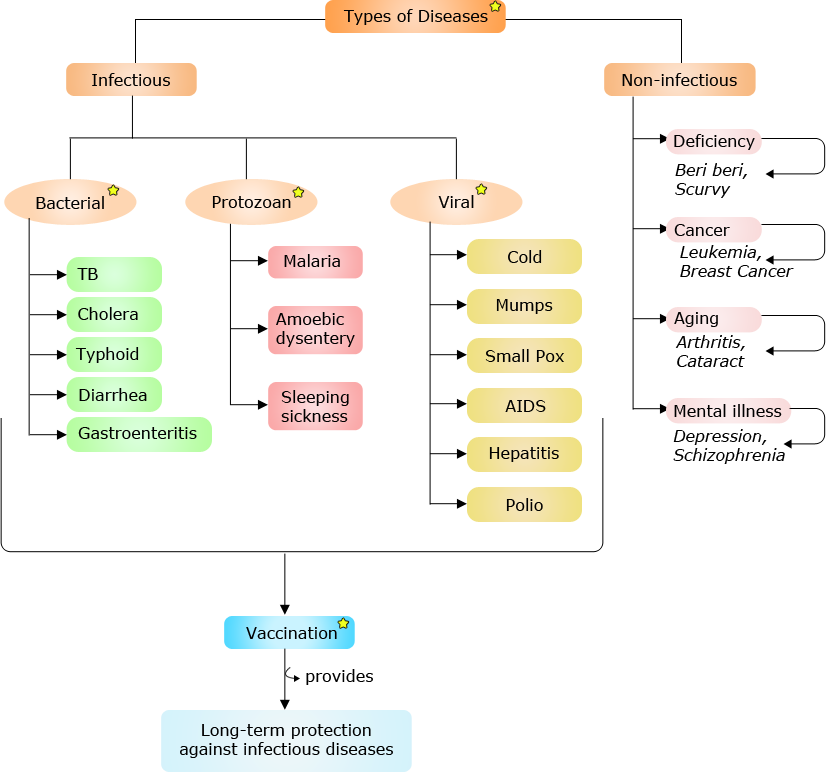

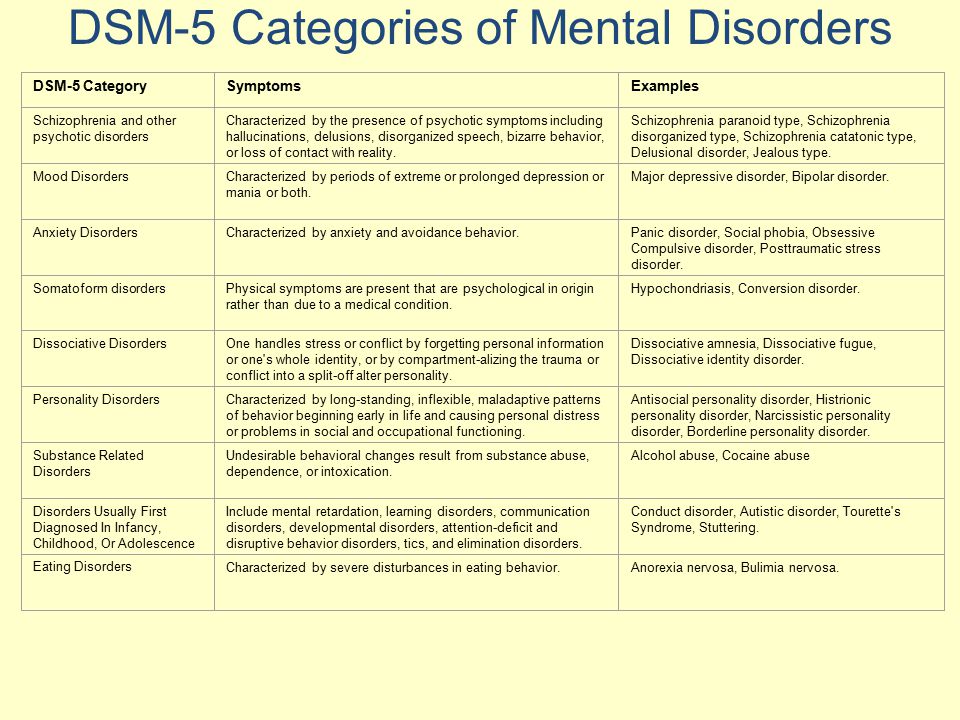

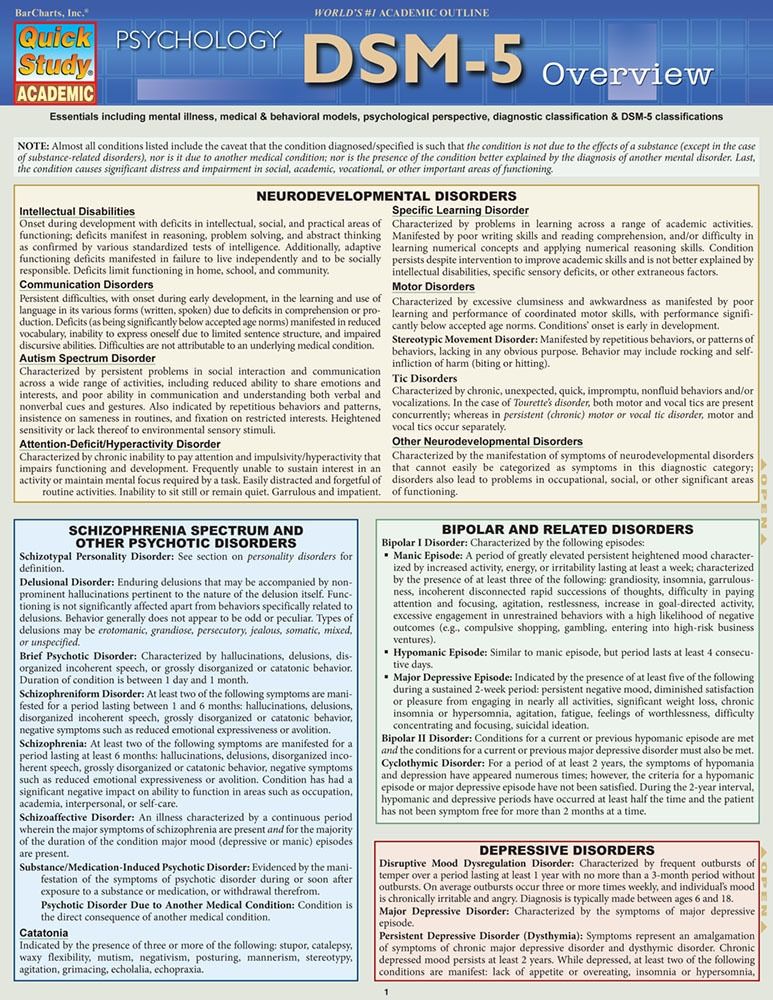

What Is Overdiagnosis?Overdiagnosis in psychiatry describes the trend of using diagnostic labels derived from the DSM-5 to assign a mental disorder that never caused the symptoms or problems in the first place, often because the diagnosis is based exclusively on a list of symptoms rather than a holistic biopsychosocial understanding of the individual. Overdiagnosis is one of the core problems with the DSM-5.

Evidence for Overdiagnosis in PsychiatryHow do we know overdiagnosis is happening? We’ve selected a handful of studies showing preliminary evidence that overdiagnosis is more prevalent than many think.

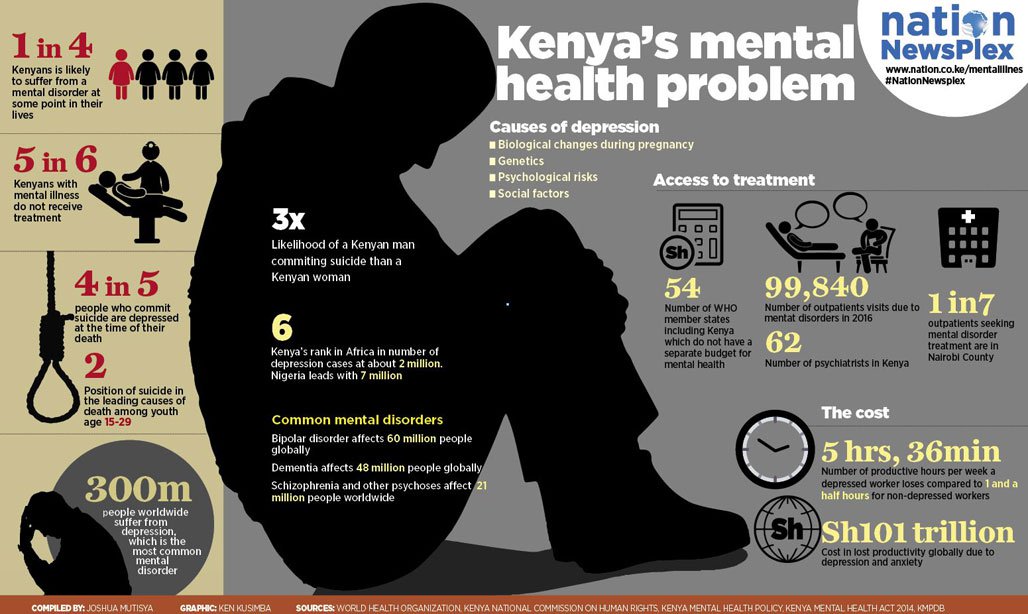

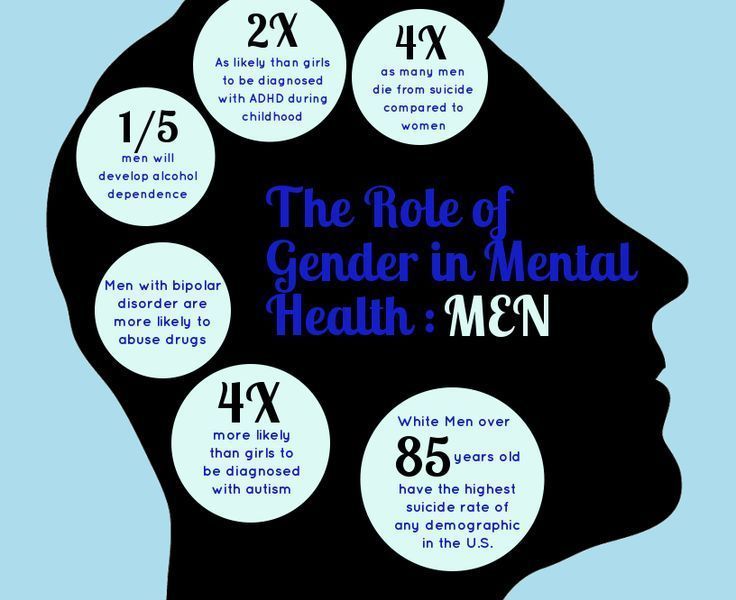

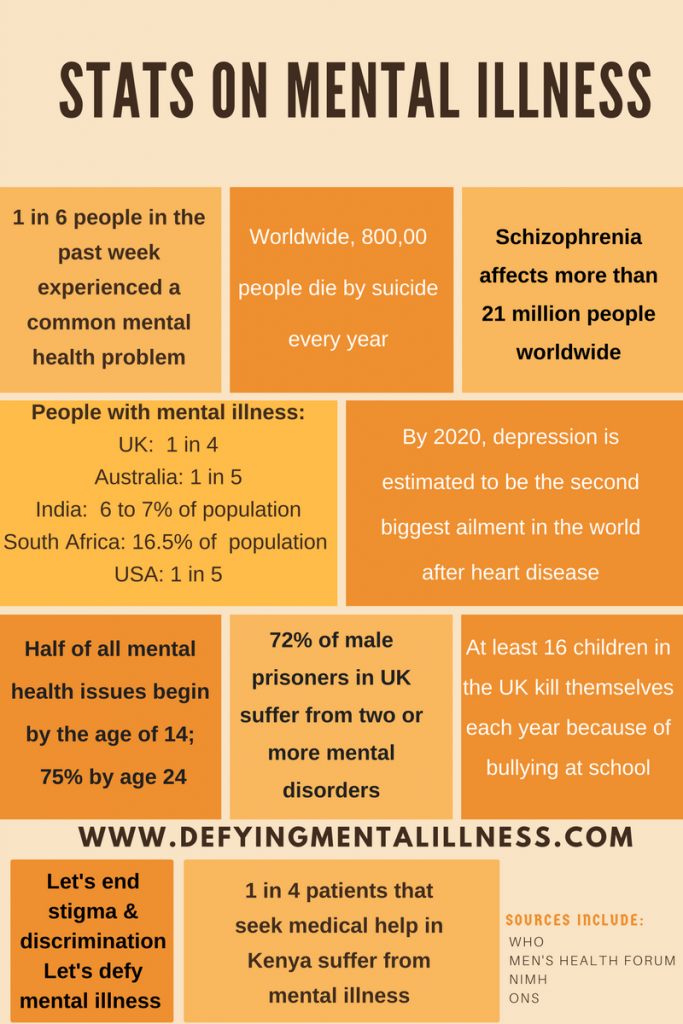

- Multiple studies have consistently shown that only 30% to 40% of individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder actually meet the criteria for the condition.

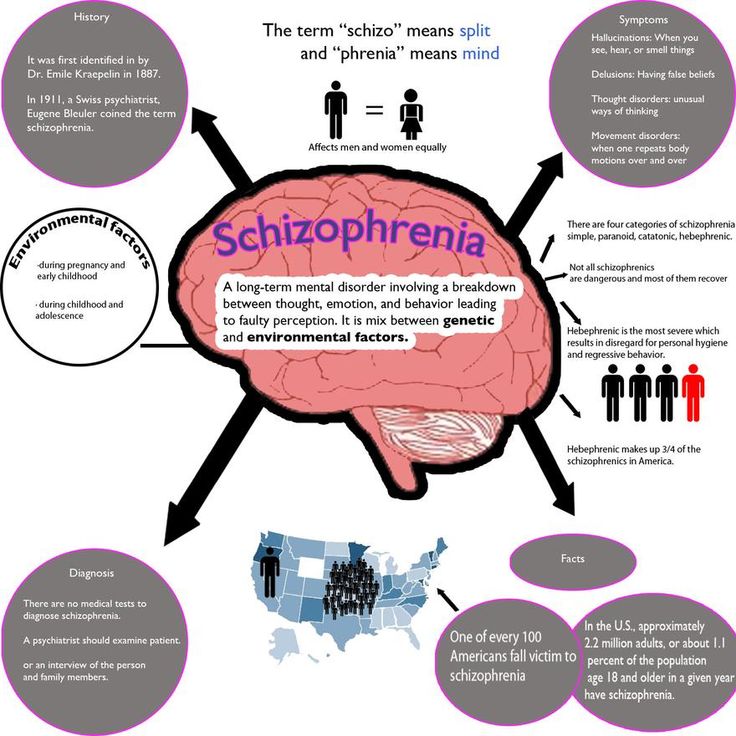

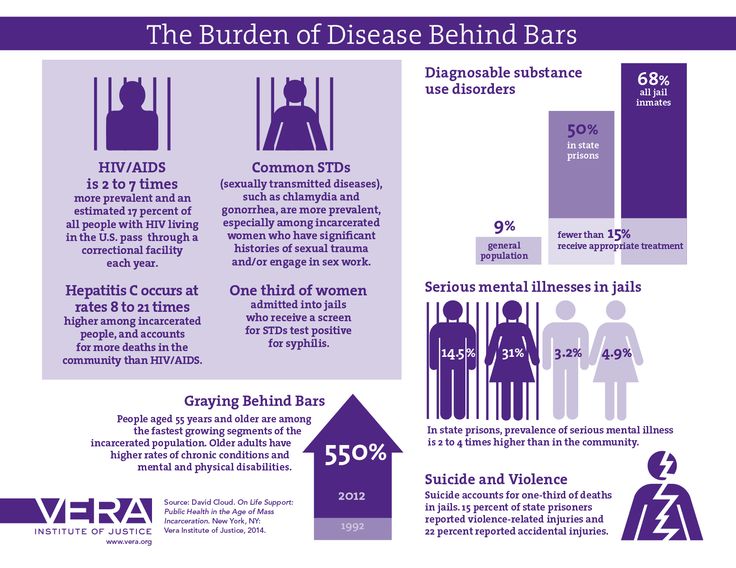

- Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers found that about half of people referred to a clinic with a schizophrenia diagnosis didn’t have schizophrenia.

- Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health also discovered that only 38.4% of adults with clinician-identified depression met the 12-month criteria for depression, despite most participants being prescribed and using psychiatric medications.

- Another study found that as many as half of obsessive-compulsive disorder cases are misdiagnosed.

Note that the evidence for overdiagnosis in psychiatry is by no means limited to these studies, but they provide an accessible entry point to understanding the scope of the issue. As always, we encourage you to do your own research before reaching any conclusions.

How Can Psychiatric Labeling Be Misused?The tendency toward overdiagnosis in the field of psychiatry is highlighted in this 2015 study examining the trend:

“Diagnoses are made rapidly—and often inaccurately. Instead of listening, and asking about current circumstances, psychiatrists focus on a checklist of symptoms, a kind of parody of the criteria listed in the DSM manual. Based on the answers to these questions, prescriptions will be written for almost every problem—and ‘adjusted’ every time a patient comes in feeling distressed.”

Instead of listening, and asking about current circumstances, psychiatrists focus on a checklist of symptoms, a kind of parody of the criteria listed in the DSM manual. Based on the answers to these questions, prescriptions will be written for almost every problem—and ‘adjusted’ every time a patient comes in feeling distressed.”

The evidence and causes behind the pattern of overdiagnosis in psychiatry raise serious questions about the consequences it can bring about.

Do you think you or someone you care about may have been inaccurately diagnosed with a mental issue? Our team can help. Let’s Talk

The Three Consequences of Overdiagnosing Mental IssuesEvery day at PCH, we see how overdiagnosed mental issues impact the lives of our clients. In our experience, these are the three things everyone should remember:

1. These Labels Never Truly Go AwayWe focus on treating OCD, anxiety, depression, bipolar, schizophrenia, and PTSD, all of which are considered lifetime diagnoses. When someone is diagnosed with one of these issues, they have to confront that they’ll have to deal with these challenges for the rest of their life because there is no “cure” for them. With guidance, individuals can learn to better manage symptoms and patterns, but there is no quick fix to make them “go away.”

When someone is diagnosed with one of these issues, they have to confront that they’ll have to deal with these challenges for the rest of their life because there is no “cure” for them. With guidance, individuals can learn to better manage symptoms and patterns, but there is no quick fix to make them “go away.”

Misdiagnosing a lifetime diagnosis can be particularly harmful for someone whose challenges and suffering are, in reality, tied to another issue. These diagnostic labels ultimately dictate treatment programs, so when someone ends up in a program for a diagnosis they don’t actually have, they rarely make progress. They may even regress or grow disillusioned with the ineffectiveness of professional treatment altogether.

Since many mental issues are lifetime diagnoses, it’s particularly challenging to get someone to see themselves as anything other than what they’ve been repeatedly told they are. The language our society uses to describe these issues also plays a significant role here. Individuals are regularly told, “You’re bipolar,” “You’re schizophrenic,” or “You’re depressed,” as though this statement is the defining feature of their identity, and many start to believe it. In reality, every person is much more than that, no matter their diagnosis.

Individuals are regularly told, “You’re bipolar,” “You’re schizophrenic,” or “You’re depressed,” as though this statement is the defining feature of their identity, and many start to believe it. In reality, every person is much more than that, no matter their diagnosis.

Getting someone who has been told they’re bipolar for years to acknowledge that they’re not actually bipolar can be as challenging—if not more so—as getting someone to reach out for help in the first place, but by then, much of the damage has already been done. They may even begin to question the usefulness of professional guidance and instead regress or turn to maladaptive self-coping mechanisms.

(For more on this, here’s why emotional dysregulation is frequently misdiagnosed as bipolar.)

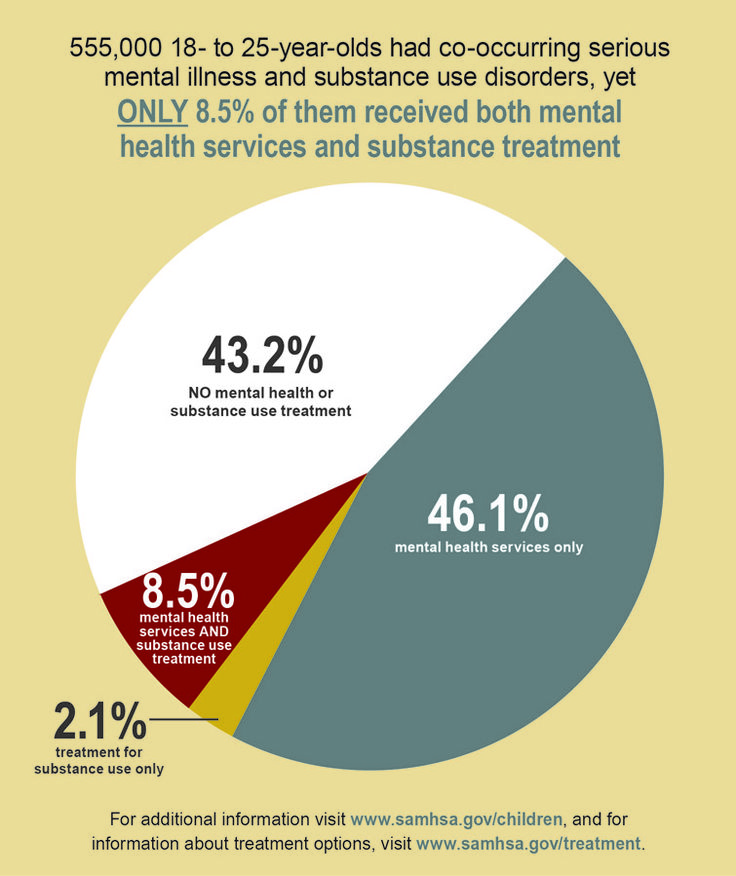

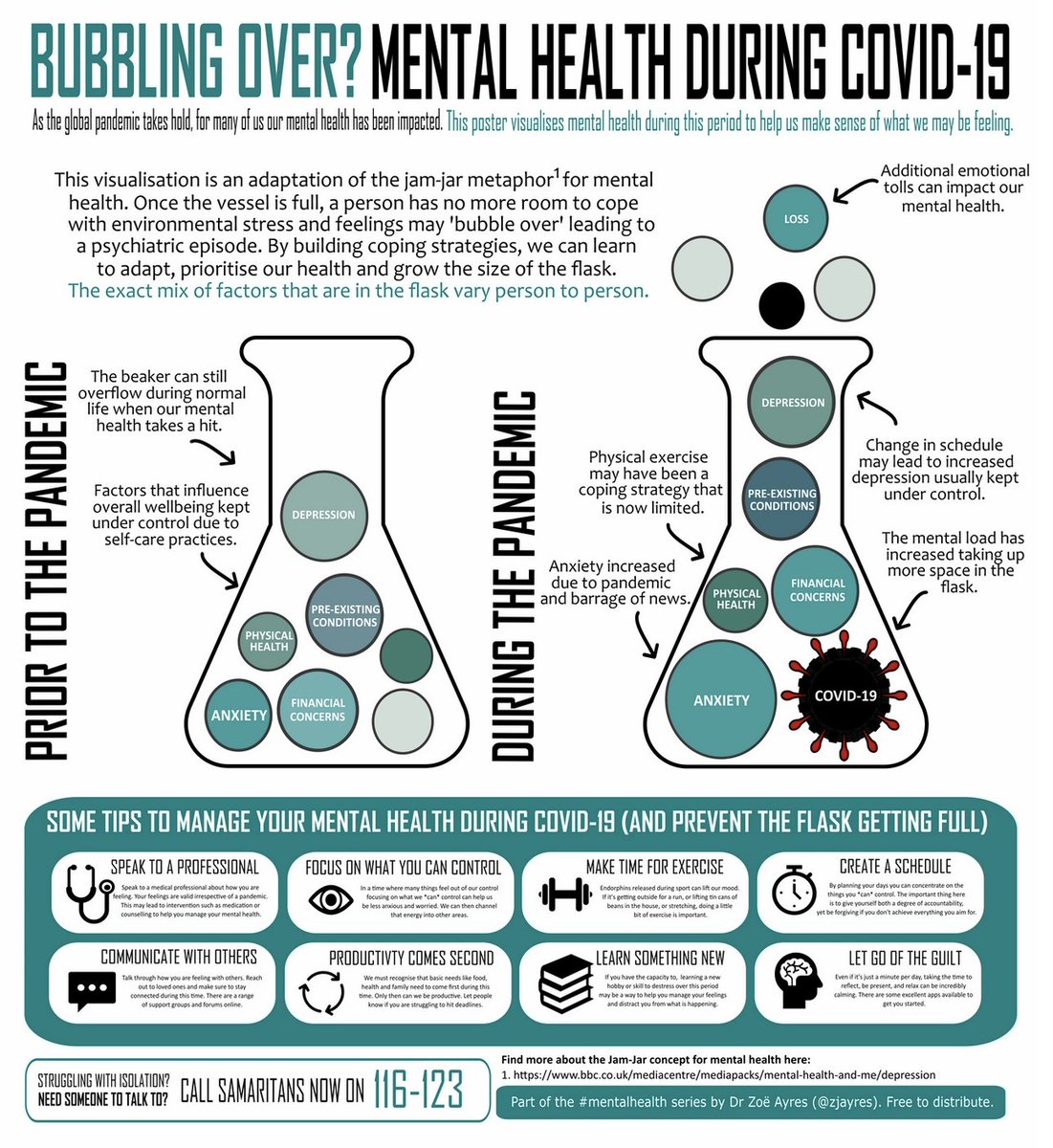

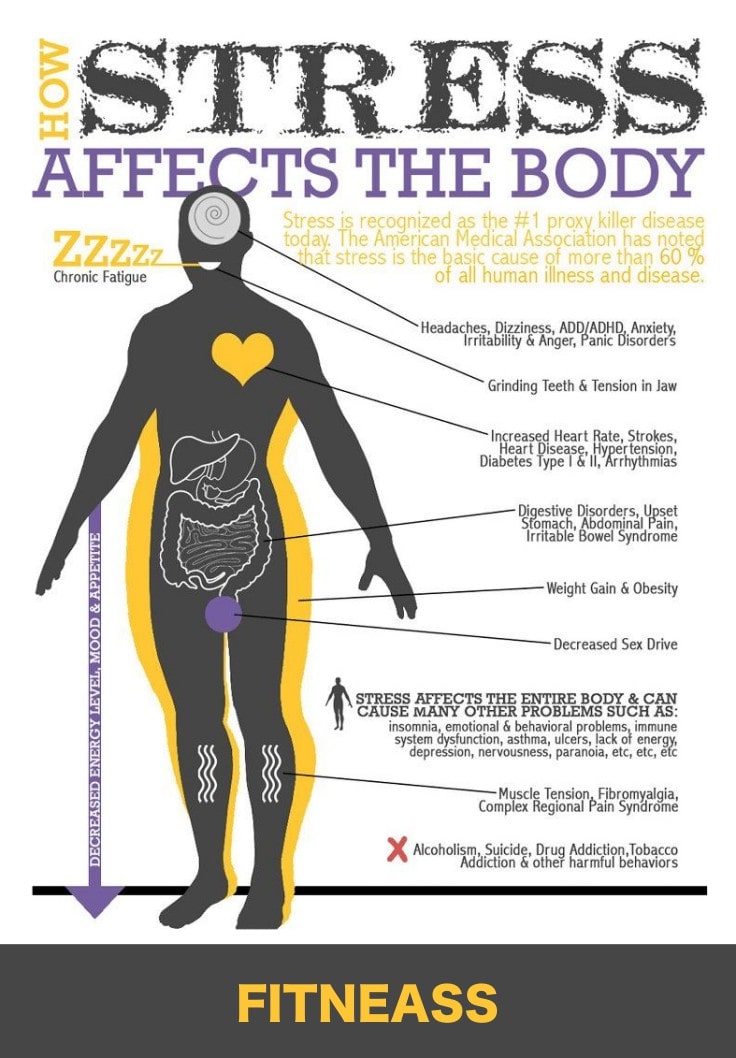

2. Overdiagnosis Leads to MismedicationTreatment programs aren’t the only thing designed around and informed by diagnostic labels—medication regimens are as well. As a result, overdiagnosing mental issues is a common cause of mismedication. When someone is medicated for an issue they don’t have, their challenges and symptoms often worsen. These medications may come with adverse side effects, exacerbate symptoms, or, as discussed above, cause an individual to give up on professional treatment altogether. Ultimately, mismedication due to overdiagnosis can do more harm than no medication at all.

When someone is medicated for an issue they don’t have, their challenges and symptoms often worsen. These medications may come with adverse side effects, exacerbate symptoms, or, as discussed above, cause an individual to give up on professional treatment altogether. Ultimately, mismedication due to overdiagnosis can do more harm than no medication at all.

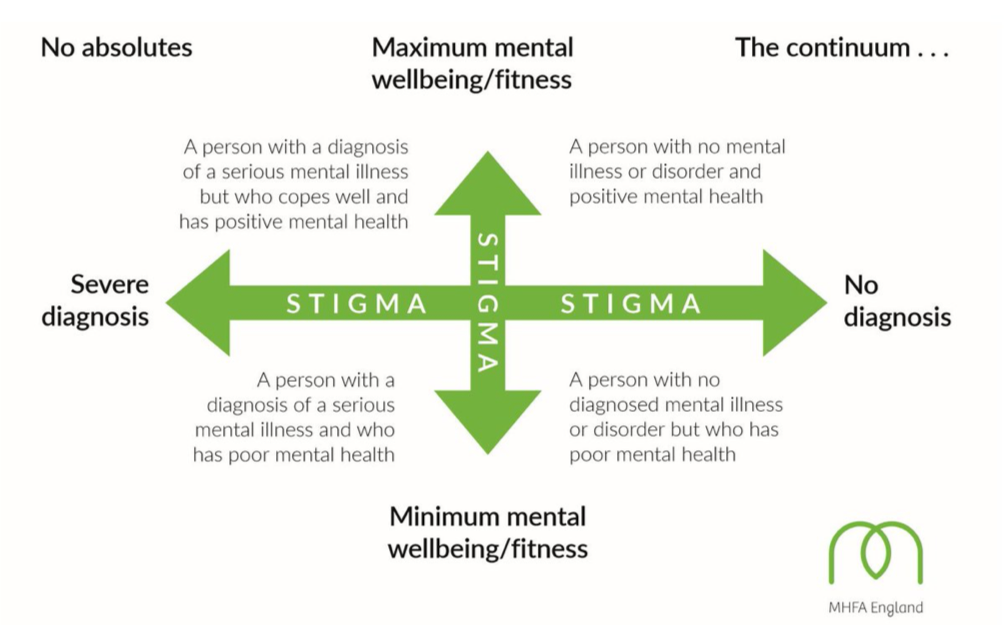

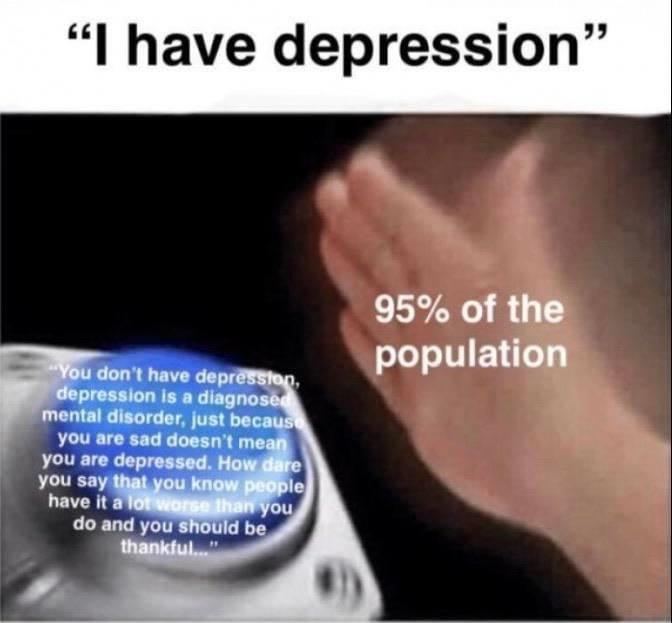

Overdiagnosing mental issues fuels social stigmas around the challenges and experiences of people struggling with them. Have you ever heard someone claim that they’re “a little OCD” because they like things in a specific order? Having an eye for detail or preferring that something be a certain way is in no way an indication of obsessive-compulsive disorder, yet social misperception often leads people to trivialize the reality of living with OCD.

When an individual is misdiagnosed (often based on symptoms alone), symptoms like these become the focus of the issue rather than the person dealing with them. In turn, mainstream society focuses on lists of symptoms instead of the ways mental issues affect normal people in their everyday lives. As a result, people struggling with them are viewed as different, less than, or outsiders, and many are afraid to seek help because they don’t want to be viewed in this light.

In turn, mainstream society focuses on lists of symptoms instead of the ways mental issues affect normal people in their everyday lives. As a result, people struggling with them are viewed as different, less than, or outsiders, and many are afraid to seek help because they don’t want to be viewed in this light.

When accurately applied, diagnostic labels can be helpful for individuals and medical professionals. They provide a shared reference point to talk about the inherent challenges, patterns, and shared perspectives that come with specific mental issues. At the same time, these labels can help individuals put words to what they’re experiencing. It’s when these diagnostic labels overshadow the individual that they do more harm than good.

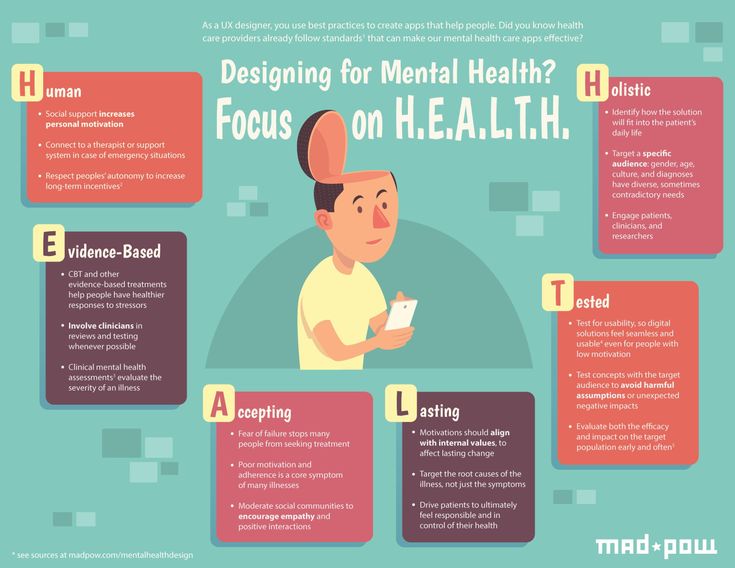

The PCH Approach to OverdiagnosisAt PCH, we strive to destigmatize mental issues, connect past trauma to present problems, and emphasize the importance of holistic treatment. A lot of the work we do in these areas involves undoing the damage caused by overdiagnosed—or misdiagnosed—mental “disorders.” While we recognize that diagnostic labels can be helpful when used responsibly, we also witness the damage overusing them can do to an individual’s psyche. Looking beyond the individual, overdiagnosis leads to misunderstanding and misrepresentation of mental diagnoses, feeding the dissemination of negative connotations across every segment of our society.

A lot of the work we do in these areas involves undoing the damage caused by overdiagnosed—or misdiagnosed—mental “disorders.” While we recognize that diagnostic labels can be helpful when used responsibly, we also witness the damage overusing them can do to an individual’s psyche. Looking beyond the individual, overdiagnosis leads to misunderstanding and misrepresentation of mental diagnoses, feeding the dissemination of negative connotations across every segment of our society.

When we say, “We want to know what happened to you, not what’s wrong with you,” what we’re really trying to say is that we view everyone who comes through our doors as more than a diagnosis. We’ve witnessed the harm overdiagnosis can do firsthand, and we’re committed to solving the problems it creates. One way we achieve that is by first validating an accurate diagnosis for everyone who walks through our doors, even if they’ve been previously diagnosed elsewhere. The fact that we have to do this is a testament to how common overdiagnosis has become in the medical community and how we’re working to solve it.

If you suspect you or someone you care about may have been misdiagnosed with a mental issue, reach out to the PCH team today.

Contact PCH Treatment Center

11965 Venice Blvd., Suite 202, Los Angeles, CA 90066

Get Directions 888-724-0040Contact Us

Understanding Social Media Effects on Mental Health

Jun 21, 2022

Understanding Social Media Effects on Mental Health Posted by Terry Krekorian, MD Posted on July 21, 2022 Categories: Depression, General Key Points: In less than two decades, social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok have...

See All

Certified by the State Department of Health Care Services

Certification number is, 190931AP

Certification expiration date is 08/31/2024

https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/

Overdiagnosis in Psychiatry: How Modern Psychiatry Lost Its Way While Creating a Diagnosis for Almost All of Life's Misfortunes, by Paris Joel

Joel Paris is a Professor of Psychiatry at McGill University in Canada, where he served as Department Chair between 1997 and 2007 and Research Associate in the Department of Psychiatry at the Jewish General Hospital. He is a former editor-in-chief of the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry and the author of many books, including Psychotherapy in An Age of Neuroscience (Oxford University Press, 2017), Stepped Care for Borderline Personality Disorder (Academic Press, 2017), The Intelligent Clinician's Guide to DSM-5 (Oxford University Press, 2015), Fads and Fallacies in Psychiatry (RC of Psych, 2013), and Half in Love with Death: Managing the Chronically Suicidal Patient (Routledge, 2006).

He is a former editor-in-chief of the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry and the author of many books, including Psychotherapy in An Age of Neuroscience (Oxford University Press, 2017), Stepped Care for Borderline Personality Disorder (Academic Press, 2017), The Intelligent Clinician's Guide to DSM-5 (Oxford University Press, 2015), Fads and Fallacies in Psychiatry (RC of Psych, 2013), and Half in Love with Death: Managing the Chronically Suicidal Patient (Routledge, 2006).

As its title suggests, Overdiagnosis in Psychiatry: How Modern Psychiatry Lost Its Way While Creating a Diagnosis for Almost All of Life's Misfortunes is a tendentious work proclaiming on its first page that psychiatrists have acquired a propensity to pathologise all manner of reactions to ordinary life circumstances: ‘Psychiatrists have forgotten the listening skills and careful attention to clinical phenomena that once made their specialty unique’ (p. xii). His concern is that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) ‘makes many of life's misfortunes diagnosable, and implicitly offers psychiatry as a cure for unhappiness’ (p. xii).

xii). His concern is that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) ‘makes many of life's misfortunes diagnosable, and implicitly offers psychiatry as a cure for unhappiness’ (p. xii).

Paris bewails the frequency with which patients are seen by psychiatrists for only ten to fifteen minutes and given little opportunity to speak about what is happening in their lives:

Diagnoses are made rapidly – and often inaccurately. Instead of listening, and asking about current circumstances, psychiatrists focus on a checklist of symptoms, a kind of parody of the criteria listed in the DSM manual. Based on the answers to these questions, prescriptions will be written for almost every problem – and ‘adjusted’ every time a patient comes in feeling distressed. (p. xiii)

He sees this form of doctor–patient relationship as one which leads to overdiagnosis and overtreatment. His motive for writing the book is to send a message that psychiatry is overstretched: ‘Instead of prescribing treatment for what Freud once called “normal human unhappiness”, we need to focus our efforts on patients who are seriously ill, and who need us the most. We do not need to diagnose the human condition’ (p. xiv).

We do not need to diagnose the human condition’ (p. xiv).

Paris identifies the phenomenon of ‘diagnosis epidemics’, a term coined by Allen Frances, as having the potential to lead to incorrect and unnecessary treatment for mental disorders. He asserts that ‘biological reductionism has come to dominate academic psychiatry’ (p. 6) and points out that until such time as neuroscience may provide explanations for psychiatric disorders, clinicians have to continue to practise their craft and treat very difficult patients. At the heart of his analysis is the acknowledgment that ‘psychiatry is more or less where the rest of medicine was a hundred years ago – at the very beginning of a long quest for valid diagnostic procedures’ (p. 11). He attempts to place within realistic parameters the quest for biomarkers for psychiatric disorders, contending that they would only provide some of the data that clinicians require, recognising that psychosocial factors in mental illness are likely to retain major importance: ‘I would say [biomarkers] are potentially highly useful but conceptually and practically incomplete’ (p. 11).

11).

Paris notes that psychiatry is no different from other areas of medicine – there is a bias towards false positives so as not to ‘miss anything’. He identifies that underdiagnosis is most likely when a disorder is unappealing – when it is chronic, making treatment complex or inaccessible. He instances the high levels of diagnosis of schizophrenia in the past but asserts that, faced with managing intractable cases, clinicians often look for ways to avoid making a diagnosis. He does not refer specifically to the stigma attaching to the ‘s’ diagnosis but could well have done so, asserting that ‘the reluctance to recognize a serious illness like schizophrenia reflects a universal human tendency to resist bad news. However, psychiatrists cannot make difficult patients go away by failing to diagnose them’ (p. 20).

Paris contrasts the modern incidence of diagnosing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and autism. However, he does not locate the problem with the DSM, Fifth Edition (DSM-5): ‘you need to focus on its practitioners, not on its manual. In short DSM-5 is not the problem, but the way we over-value it is’ (p. 32). He argues that while DSM diagnoses are convenient labels, they should not be thought of as ‘real’ diseases. He locates overdiagnosis in optimism about treatment methods and underdiagnosis in pessimism about treatability. He argues that the side effects of ‘typical’ antipsychotics have discouraged writing too many prescriptions but that the obverse is the case in the era of the ‘atypicals’.

In short DSM-5 is not the problem, but the way we over-value it is’ (p. 32). He argues that while DSM diagnoses are convenient labels, they should not be thought of as ‘real’ diseases. He locates overdiagnosis in optimism about treatment methods and underdiagnosis in pessimism about treatability. He argues that the side effects of ‘typical’ antipsychotics have discouraged writing too many prescriptions but that the obverse is the case in the era of the ‘atypicals’.

Paris reflects on the difficulties that have been encountered within psychiatry in differentiating between a ‘mental disorder’ and a condition falling short of such a classification. His argument is that most mental disorders have ‘fuzzy boundaries’ and fade gradually into normality:

When does sadness turn into depression, particularly when life stressors (grief, job loss, breakups of intimate relations) that would upset almost anyone are present? When should anxiety and worry justify diagnosis if there is something real to worry about? At what point is substance use an addiction? (p.

63)

Paris argues that major depression is seriously overdiagnosed. He notes that the term dates back to the DSM, Third Edition (DSM-III), where there was an attempt to distinguish depressive episodes with clinically significant effects on functioning from minor symptoms that are passing and not disabling. He notes that the percentage of the United States population taking antidepressants had risen to 11% by 2011, expressing concern about the frequency with which treatment for depression is pharmacological and does not incorporate psychotherapy.

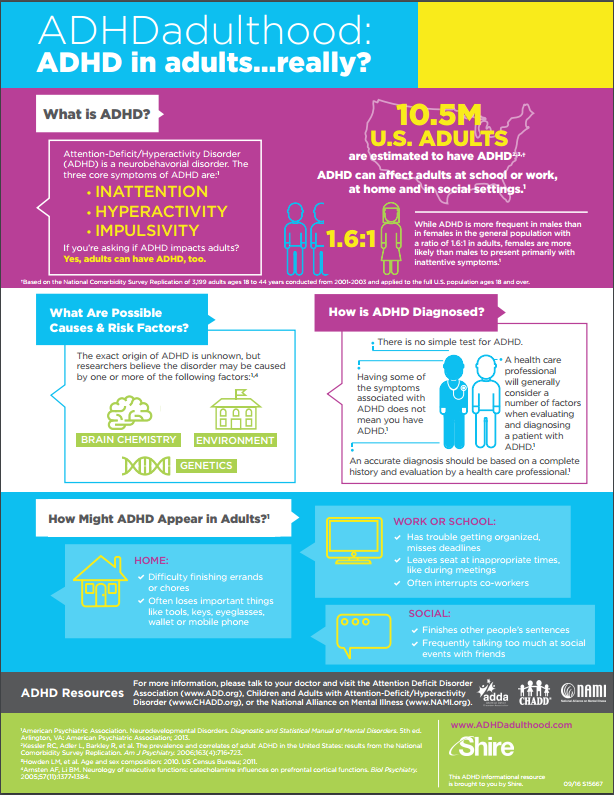

A second category of mental disorder identified by Paris as overdiagnosed is bipolar disorder. He notes that bipolar-II disorder is a new category that was inserted into the DSM, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), characterised by hypomania instead of full mania. He regards overdiagnosis of bipolarity as ‘one of the most problematic fads in contemporary psychiatry’ (p. 82). He describes the ‘miracle of lithium’ as responsible for a dramatic increase in the diagnosis of schizophrenic patients as having bipolar disorder and being prescribed lithium therapy. He comments that the marketing undertaken by ‘Big Pharma’ encourages doctors and patients alike to believe that depression which antidepressant treatment fails to resolve indicates an underlying bipolar disorder that needs to be treated with other drugs. He is especially troubled by the increase in the diagnosis of bipolarity in children.

He comments that the marketing undertaken by ‘Big Pharma’ encourages doctors and patients alike to believe that depression which antidepressant treatment fails to resolve indicates an underlying bipolar disorder that needs to be treated with other drugs. He is especially troubled by the increase in the diagnosis of bipolarity in children.

Paris singles out overdiagnosis of PTSD as the product of careless thinking and emotional bias. He observes that trauma is only a risk factor for PTSD, not a definitive cause: ‘The disorder only develops when adverse life experiences touch on temperament and vulnerability’ (p. 99). Controversially, while he does not dispute the legitimacy of the diagnosis of PTSD in principle, he argues that PTSD runs the danger of encouraging victimhood and discouraging a sense of responsibility for one's life: ‘The debate about this diagnosis is not just a matter of evaluating empirical data, but about society's concern over oppression and suffering. That cannot be good for psychiatry, which must put science ahead of politics’ (p. 103).

103).

Unsurprisingly, Paris identifies the medicalisation of attention through the diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as fraught. He describes it as one of the most striking diagnostic epidemics of our times, asserting that the diagnosis is ‘driven by the use of stimulants. There is no doubt that these drugs help children with classical cases of ADHD, particularly the hyperactive subtype, although not all patients respond to them’ (pp. 107–108). His argument is that ADHD is a syndrome, not a disease, and he expresses concern about the difficulty of distinguishing it in children from conduct disorder. He argues that it has become a catch-all diagnosis for disruptive behaviour and that current mental health practice is not rooted in science.

Paris also identifies personality disorders – especially borderline, autism spectrum, and anxiety disorders – as being at risk of overdiagnosis. He does not refer to hoarding disorder, although he might have done.

Paris notes that consumerism plays a role in patients’ expectations of receiving a diagnosis for what troubles them, arguing in favour of psychiatry embracing evidence-based diagnosis: ‘Doing so would subject the diagnostic process to the same caution and scepticism as have been applied to the results of treatment research’ (p. 151). He contends that psychiatry needs to be characterised by diagnostic humility, and that the fallacy of overdiagnosis is the delusion that we know the answers: ‘We must have the courage to admit that, at this point, we don't’ (p. 152).

Paris’ Overdiagnosis in Psychiatry is a robust tome of the type that can only be written by a senior member of the profession who does not feel constrained by latter-day orthodoxies. It is a free-ranging critique of poor diagnostic practice, concentrating on overdiagnosis but also identifying the vice of underdiagnosis. It is well referenced and compellingly historically contextualised. Its point of view is accessible and powerful. Paris combines unpretentious scholarliness and clinical experience with rare skill. Fads always afflict diagnosis in medicine – and in no area more so than psychiatry. His argument in favour of evidence-based diagnosis and diagnostic humility is powerful and relevant both clinically and forensically – over-diagnosis can lead to civil litigation, as well as issues in sentencing in criminal trials.

Paris combines unpretentious scholarliness and clinical experience with rare skill. Fads always afflict diagnosis in medicine – and in no area more so than psychiatry. His argument in favour of evidence-based diagnosis and diagnostic humility is powerful and relevant both clinically and forensically – over-diagnosis can lead to civil litigation, as well as issues in sentencing in criminal trials.

Paris’ Overdiagnosis in Psychiatry is deceptively easy to read. It contains much wisdom and highlights many clinical challenges. With the recent escalation in the diagnosis of PTSD, bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and ADHD – to name but some of the conditions he focuses on – there is a risk of over-pathologisation with all of the risks that this entails in terms of not just patients’ self-image but also the over-prescription of psychotropic medications. Paris leaves mental health practitioners, lawyers and patients with much food for thought. Overdiagnosis in Psychiatry deserves wide readership and debate.

Appendices: Latest news of Russia and the world - Kommersant Zdravookhranenie (119579)

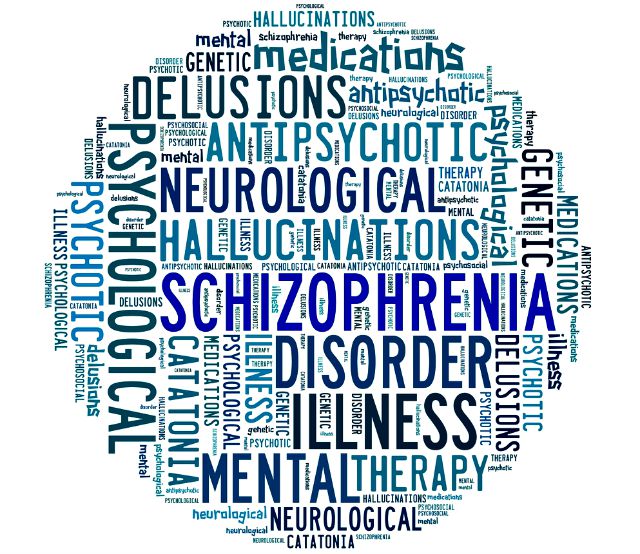

In 2013, there were 559,420 people diagnosed with schizophrenia in Russia, in 2017 - 488,500. It has become less, but still a lot. Representatives of the Russian Society of Psychiatrists are sounding the alarm: overdiagnosis of schizophrenia is observed in Russia.

Photo: Alexander Petrosyan, Kommersant / buy photo

Photo: Alexander Petrosyan, Kommersant / buy photo

Introduction to Psychiatry

In 15 years, the number of schizophrenic patients in the world has increased by 30% and today stands at 45 million people, or 0.8%. By 2020, mental disorders will be among the top five diseases that will lead in terms of the number of people lost work associated with these diseases. These are the forecasts of the World Health Organization. Public opinion in our country is such that patients with schizophrenia are considered dangerous to society.

Mental disorders will soon overtake cardiovascular diseases, which are still traditionally leading in the structure of morbidity of the world's population. Schizophrenia leads to disability more often than blindness, and only dementia and paralysis are ahead of it.

Vivid symptoms

There are three main symptoms of schizophrenia: psychotic, they are also productive, or positive, negative, and also cognitive. Psychotic symptoms are vivid, dramatic, widely described in the culture. For example, hallucinations (visual, auditory, bodily) and delusions. Although there are "true" hallucinations and pseudo hallucinations. In the first case, a person hears a voice calling him from the kitchen, or sees a heron standing on his bed. This form almost never occurs in schizophrenia, although most people are sure of the opposite, but it indicates the presence of pathology - intoxication, trauma, tumors, epilepsy. Pseudo-hallucinations are when the patient sees everything through the “receiver”, these are the very “voices” that comment on something, call for action, order and even threaten. In this case, the voices can become a spiritual mentor or, conversely, they will drive you crazy.

In this case, the voices can become a spiritual mentor or, conversely, they will drive you crazy.

Delusion is a mental disorder in which a person's thoughts, conclusions, conclusions are based on illogical judgments, it is impossible to argue with such a patient and it is impossible to dissuade what he claims. This is also a psychotic symptom. Primary delirium develops for a long time, consistently, for example, a neighbor is poisoning me, so I will defend myself. And the secondary one occurs against the background of an altered mood, hallucinations, when it is necessary to interpret what surrounds the patient. There are also delusions of the external environment, such as the induced delusions that often occur in cult founders; delusions of pardon, when the prisoner believes that he will be shot in any case, railway paranoia, when it seems that everyone is whispering, watching, discussing, wanting to do harm. The main problem is that absolutely anyone can have delusions and hallucinations, for example, in case of poisoning or blood loss, high fever, infectious diseases. And it is impossible to diagnose "schizophrenia" in such a state.

And it is impossible to diagnose "schizophrenia" in such a state.

However, according to the results of a survey of the Russian Society of Psychiatrists, in which 807 psychiatrists with an experience of about 17 years took part, only 14% diagnose "schizophrenia" in full accordance with the ICD (International Classification of Diseases), while the rest are not guided by all the principles of the ICD or remember not all the symptoms. And 3% believe that it is necessary to completely remove the main signs of schizophrenia from the ICD-10 - negative symptoms and cognitive impairment.

Negative symptoms are a decrease in energy in a person, apathy, lack of will. Cognitive impairment is a disorder of thinking, perception, attention. The patient may experience disorganization of thinking, speech, he can socially isolate himself, which is often accompanied by silence, remain in a frozen pose for a long time, or, conversely, fall into aimless excitement, which is expressed in pretentiousness, mannerisms, unnatural plasticity, endless walking and wringing of hands . However, none of the signs is sufficient for the diagnosis of schizophrenia, it can be any other disease. But the presence of all three at the same time - positive, negative and cognitive symptoms lasting at least six months - can indeed be a sign of schizophrenia.

However, none of the signs is sufficient for the diagnosis of schizophrenia, it can be any other disease. But the presence of all three at the same time - positive, negative and cognitive symptoms lasting at least six months - can indeed be a sign of schizophrenia.

Often this disease begins in adolescence or even childhood, sometimes later. According to statistics, only 50% of patients have frequent or prolonged hallucinations. According to a large study (Epidemiological Catchment Area Project, USA), 11–13% of people have hallucinations at least once in their lives. Another Dutch study found that "true pathological" hallucinations occurred in 1.7% of the population, but another 1.7% experienced hallucinations that were not considered clinically significant.

Consequences of overdiagnosis

In 2013, there were 559,420 people diagnosed with schizophrenia in Russia, in 2017 - 488,500. These data do not indicate that there are fewer patients with schizophrenia, but that the diagnosis has become more accurate. And yet, representatives of the Russian society of psychiatrists are sounding the alarm: in Russia, this diagnosis is made unreasonably often. For example, the multiplicity of discrepancies in the number of patients with bipolar personality disorder (BAD), which resembles schizophrenia in some manifestations, differs by 150 times in the world and in Russia! And the multiplicity of discrepancy between depressive and anxiety disorders, which can also be accompanied by a single psychosis, is 60 times! At the same time, world medicine indicates that the prevalence of schizophrenia is the smallest among other mental disorders. This means that patients with bipolar disorder and disorders are often treated with us as patients with schizophrenia.

And yet, representatives of the Russian society of psychiatrists are sounding the alarm: in Russia, this diagnosis is made unreasonably often. For example, the multiplicity of discrepancies in the number of patients with bipolar personality disorder (BAD), which resembles schizophrenia in some manifestations, differs by 150 times in the world and in Russia! And the multiplicity of discrepancy between depressive and anxiety disorders, which can also be accompanied by a single psychosis, is 60 times! At the same time, world medicine indicates that the prevalence of schizophrenia is the smallest among other mental disorders. This means that patients with bipolar disorder and disorders are often treated with us as patients with schizophrenia.

This situation can be changed by treating patients with schizophrenia and similar psychiatric illnesses selectively, giving people a chance for rehabilitation, and not giving up on them. After all, most often they are not dangerous, no matter how those who stigmatize these diseases try to prove it.

Ksenia Suvorova

Soviet psychohygienists and overdiagnosis in the 1930s

The global trend, which began to unfold from the 1890s, took psychiatry out of the gloomy asylums for the mentally ill, which, strictly speaking, were not perceived as proper medical institutions. Psychiatry sought not only to establish itself in the status of a full-fledged (“same as others”) medical discipline and to change outdated internal orders. The movement outward, into the world, beyond the boundaries marked by the fence of the hospital, reflected the new ambitions of the Alienist doctors.

This was not only a move away from the specifics of secure institutions towards a practice less removed from the world of ordinary people. Along with organizational boundaries, psychiatry expanded its understanding of the subject of its attention. The competence of the psychiatrist expanded in parallel with the secularization of his trade and the more secure consolidation of psychiatry in the circle of medical specialties. Psychiatrists are beginning to deal with new types of people: serial killers, sexual deviants, alcoholics, children with behavioral problems, war veterans.

Psychiatrists are beginning to deal with new types of people: serial killers, sexual deviants, alcoholics, children with behavioral problems, war veterans.

The limited capacity of the hospitals was becoming increasingly frustrating. A qualitative change in treatment was to be expected for another half century, before the psychopharmacological revolution of the 1950s. Asylums functioned as alternatives to prisons, with the cruelty inherent in repressive institutions.

It is understandable why doctors turned to the topic of preventive medicine, that is, to social work for the prevention of mental illness. In the USSR, the development of preventive psychiatry became possible due to the relative autonomy of the psychiatric community in 1920 years Mental hygiene was a project blessed by the government but invented by psychiatrists themselves. Closing of the project in 1930 due to the fact that, firstly, the attitude of the authorities towards the autonomy of psychiatric science has changed. Secondly, screening examinations carried out as part of psychoprophylaxis did not paint the radiant picture at all that was in demand during the years of the Great Break.

Secondly, screening examinations carried out as part of psychoprophylaxis did not paint the radiant picture at all that was in demand during the years of the Great Break.

Ideological pretensions in this case fell into the weak spot of the scientific method. Later, the Soviet government would take a different view of the fluidity of diagnostic criteria in "minor psychiatry", noting that blurring the boundaries of the norm had its advantages in terms of control over civil society.

But in 1930 in psychiatric overdiagnosis, the party authorities did not see anything useful for themselves. By 1936, when the Second All-Union Congress of Neurologists and Psychiatrists was held, it became clear that independent psychiatry posed a danger to the Party's monopoly on the consciousness of Soviet citizens. Officials of the People's Commissariat of Health considered that it was time for doctors to return to questions of biological psychiatry, freeing up the territory of borderline conditions, which doctors had once invaded under the banner of diagnosing "mild schizophrenia. "

"

The question of who owns this territory has its own history. In these, so to speak, territorial disputes, topics of a non-medical nature have always been raised. Therefore, the interest of the state authorities in the problem of “minor psychiatry” is quite understandable.

Mental instability, often encountered in pre-revolutionary Russian society, was liked to be used in political discussions by both the guards and the revolutionaries. For conservatives epidemic nervousness testifies to the harm that a separation from traditional values and the usual Russian way of life brings. For the revolutionaries, the reason for the mental instability of the people lies in the policy of the tsarist government.

The idea of a psychiatrist as a mental hygiene missionary is in tune with the spirit of the times. The tendency of psychiatry to expand the field of responsibility coincided with the worldwide growth of socialism in all its varieties. The socialist ideal is built on the belief in the ability to purposefully organize the life of society in accordance with reasonable, scientifically based principles, the implementation of which is entrusted to especially intelligent and responsible members of society. A psychiatrist in such a society cannot remain just a doctor. Given the nature of the diseases with which he works, he must assume the function of a social pathologist who contributes to the betterment of society.

The socialist ideal is built on the belief in the ability to purposefully organize the life of society in accordance with reasonable, scientifically based principles, the implementation of which is entrusted to especially intelligent and responsible members of society. A psychiatrist in such a society cannot remain just a doctor. Given the nature of the diseases with which he works, he must assume the function of a social pathologist who contributes to the betterment of society.

The very idea of social psychiatry was born in Germany in 1880-90, i.e. at the same time that the social insurance system appeared in Germany for the first time in Europe, which became the prototype for all government social programs. The first public organizations to promote social psychiatry arose in the USA (Committee of Mental Hygiene, 1909). In the 1920s psychohygiene fascinated Soviet psychiatrists.

Preventive psychiatry at the beginning of the 20th century. sang a duet with eugenics. About psychiatric diseases since the 19th century. used to think of as signs of "degeneration". The process of degeneration is slow and takes the lifetime of several generations. It happens that a person with a mental pathology retains intelligence and, moreover, is quite productive in creativity. All the art of the era of decadence was created, according to the proponents of the theory of degeneration, by such people, “higher degenerates,” as Morel’s student V. Magnan called them [1].

About psychiatric diseases since the 19th century. used to think of as signs of "degeneration". The process of degeneration is slow and takes the lifetime of several generations. It happens that a person with a mental pathology retains intelligence and, moreover, is quite productive in creativity. All the art of the era of decadence was created, according to the proponents of the theory of degeneration, by such people, “higher degenerates,” as Morel’s student V. Magnan called them [1].

The simplest way to stop the spread of degeneration is to stop the reproduction of carriers of bad heredity. If it is not possible to isolate everyone in the hospital, then you can try to sterilize. But mass sterilization requires precise criteria for a socially dangerous disease, the definition of which has always been a problem.

In Germany, psychiatrists were sympathetic to such eugenic practices as marriage prohibitions, sterilization and euthanasia. The Nazis banned at 1935 years of activity of societies of mental hygiene, but the ideas discussed in the context of preventive psychiatry were ruthlessly implemented [2].

The Fascists in Italy took a different path. Instead of eugenic manipulations with the population, they preferred the most primitive and most cumbersome, from the point of view of bureaucracy, method - they tried to isolate all patients in hospitals. The result of this policy was a doubling of the number of patients in the period 1900-1940. and, as a result of overcrowding in hospitals, a decrease in the quality of medical care [3].

In principle, Lev Rosenstein (1884-1934) was not against eugenics - the central figure in the plot under discussion. A doctor, a student of Serbsky, the author of the first Soviet laws on psychiatry, scientific secretary of the RSFSR People's Commissariat of Health, Rosenstein wanted to implement the ideas of social psychiatry in Soviet Russia.

Rosenstein served as director of the Institute of Neuropsychiatric Prevention, which was created by the People's Commissariat of Education. When the psychologists who worked there began to be impudent about the classics of Marxism, the Institute was transferred to the People's Commissariat of Health.

The weakness of eugenics, according to Rosenstein, is that its practical application is possible only in small communities. If “hereditary degenerative forms” are detected in a village, then “active eugenic intervention” should be carried out in such a village [4]. However, Rosenstein saw more prospects in studies of social factors, rather than hereditary ones.

There is something deeper in this preference for emphasizing than a scientific school. Since 1840 the Russian intelligentsia fell in love with the expression "environment stuck." The idea that a person can “degenerate” or lead a criminal lifestyle, simply because it is “written by birth”, that is, genetically predetermined, seems too cruel. I would like to believe that the whole trouble is that the “environment is stuck”, and if the environment is skillfully reformed, no one will “degenerate” anymore.

The classics of pre-revolutionary science (Bekhterev, Serbsky) thought so: mental health suffers from the poor socio-political structure of Russia, the state must be remade, then people will become healthier.

Rosenstein was interested in “nervousness”, a condition in which a person does not need to be isolated, as in the case of psychosis, but must be treated, paying attention to environmental factors that influenced the appearance of mental abnormalities. According to Rosenstein, psychiatrists should take up the reorganization of the life of Soviet citizens. Otherwise, people will suffer not only “nervousness”, but also more serious pathologies.

The ideal of the Soviet psychiatrist was seen as follows: “An active participant in the struggle to change people’s way of life in order to possibly completely eliminate all reasons for personal, family, property and social conflicts and in the name of the most perfect organization of human energy in the field of invigorating collective labor” [5 ].

The philosophy of this approach is simple - the psyche breaks down due to poor social conditions, and in order not to get sick, it is necessary to reorganize the environment. The position of the psychiatrist must be active. He does not wait for a patient with complaints, but he himself is engaged in the study of society, scanning the population for suspicious symptoms.

The position of the psychiatrist must be active. He does not wait for a patient with complaints, but he himself is engaged in the study of society, scanning the population for suspicious symptoms.

Psychoneurological dispensaries, which began to be created in 1925, were to serve this purpose. The essence of the dispensary method is acquaintance with the living conditions of potential patients, “psychosanitary” [6] on a countrywide scale. For this purpose, the PND had the position of “household doctor” [7].

The organization of local mental health care in every district of the city is a super-advanced idea for its time. In France, for example, such a system appeared only in the 1960s, when, thanks to new drugs, chronically ill people could be sent home and monitored at their place of residence, instead of being kept in a hospital [8].

The first results of the mass medical examination showed that Soviet people are practically on the verge of collapse. Most of the examined complained of headache, irritability, fatigue, apathy, lethargy and insomnia [9]. The identified symptom complex could be designated as a form of “mild schizophrenia”, which was later done, but most often psychiatrists spoke of “nervousness”, using not only a less stigmatizing term, but also a term that differs from the word “neurasthenia” known since pre-revolutionary times. “Nervousness” sounds ordinary and simple, in contrast to the “neurasthenia” that evokes an aristocratic flavor.

Most of the examined complained of headache, irritability, fatigue, apathy, lethargy and insomnia [9]. The identified symptom complex could be designated as a form of “mild schizophrenia”, which was later done, but most often psychiatrists spoke of “nervousness”, using not only a less stigmatizing term, but also a term that differs from the word “neurasthenia” known since pre-revolutionary times. “Nervousness” sounds ordinary and simple, in contrast to the “neurasthenia” that evokes an aristocratic flavor.

P. Gannushkin in 1926 proposed the term “acquired mental disability” [10]. Such disability is acquired at a young age, up to 30 years, as a result of brain exhaustion by hard work in poor living conditions. And if in the case of neurasthenia a fairly effective treatment can be a long, high-quality and regular sleep, then the “wear and tear” of the brain is not treated in this way.

This disease was especially to be feared by party workers, who did not spare their health at all. They forcedly, without the appropriate education, switched from manual labor or military service to mental work, which, according to the psychiatrists who observed them, did not always go without consequences for the psyche. Powerful words on this subject were said in 1930 by psychiatrist Leon Rokhlin: “What the party activist lives with – the brain and the heart – is the one that hurts him the most” [11].

They forcedly, without the appropriate education, switched from manual labor or military service to mental work, which, according to the psychiatrists who observed them, did not always go without consequences for the psyche. Powerful words on this subject were said in 1930 by psychiatrist Leon Rokhlin: “What the party activist lives with – the brain and the heart – is the one that hurts him the most” [11].

When explaining general morbidity, Rosenstein used a psychohygienic approach. People get nervous and sick because they live in bad conditions (poor food, poor housing, too much work, little rest).

Here there was an inevitable clash with the official ideological interpretation of Soviet life. Later it will be explained to psychohygienists that the social reasons for “nervousness” were relevant only under the old regime, while under the Soviet regime the working man lives well. After all, Rosenstein himself taught that the increase in the incidence of neurasthenia in the West indicates the approaching death of capitalism [12]. It turned out a logical contradiction: the same mental state, depending on specific environmental factors, occurs in different social systems. Maybe patients under capitalism suffer from completely different diseases that are impossible to get sick under socialism? It would be difficult to defend such a view without shying away from the materialistic view of the psyche. Then maybe environmental factors coincide? But this is already a dangerous heresy, denying the qualitative difference between life in a bourgeois state and life in a Soviet country. A Soviet citizen cannot suffer from work, because no one exploits him like workers in the West.

It turned out a logical contradiction: the same mental state, depending on specific environmental factors, occurs in different social systems. Maybe patients under capitalism suffer from completely different diseases that are impossible to get sick under socialism? It would be difficult to defend such a view without shying away from the materialistic view of the psyche. Then maybe environmental factors coincide? But this is already a dangerous heresy, denying the qualitative difference between life in a bourgeois state and life in a Soviet country. A Soviet citizen cannot suffer from work, because no one exploits him like workers in the West.

If desired, in the texts of psychiatrists of the 1920s. one can find quite a few moments that certainly aroused surprise in the class-conscious reader - what, in fact, is comrade psychiatrist hinting at? For example: “We see soldiers of the Red Army among the disabled with traumas of the civil war, and we have not seen at all former soldiers of the White Army who suffered the same reactions” [13].

Early 1930s the PND system flourished. In 1930, Rosenstein had the status of a successful and respected Soviet psychiatrist. But already at the end of 1931 he comes under attack from criticism.

The fact is that in a totalitarian state there can be no free science of man. The fundamental conflict lies in how the party and psychiatry see and classify people. For a party ideologist, the determining factor in a person is his class affiliation. In 1920-30s. people were divided into workers, peasants, intellectuals and “former”, those who belonged to social groups that, in theory, should not exist under communism (priests, for example). But the psychiatrist is not obliged to follow class theory in the study of the psyche. If psychiatry is “the same” medicine as other disciplines (cardiology, pulmonology, etc.), then it works with diseases, the explanation of which is meaningless to look for in the texts of Marx and Lenin.

The principle of partisanship, that is, ideological loyalty and organizational subordination to the party, was introduced in the Soviet country at different speeds. The peak of Rosenstein's activity came just at the moment when partisanship prevailed in medicine and psychiatry in particular. It is clear that partisanship is absolutely incompatible with the sciences of nature. But, as Ernest Kolman, who was in charge of ideology in the social sciences in the Agitprop of the Central Committee, taught, those who think so simply do not want to accept the infallibility of the dictatorship of the proletariat: “All attempts by any scientific discipline to present itself as an autonomous, independent scientific discipline objectively mean opposition to the general line of the party, opposition to the dictatorship of the proletariat /.../ There can be no non-party, no political apathy towards natural science.

The peak of Rosenstein's activity came just at the moment when partisanship prevailed in medicine and psychiatry in particular. It is clear that partisanship is absolutely incompatible with the sciences of nature. But, as Ernest Kolman, who was in charge of ideology in the social sciences in the Agitprop of the Central Committee, taught, those who think so simply do not want to accept the infallibility of the dictatorship of the proletariat: “All attempts by any scientific discipline to present itself as an autonomous, independent scientific discipline objectively mean opposition to the general line of the party, opposition to the dictatorship of the proletariat /.../ There can be no non-party, no political apathy towards natural science.

In 1931, the Politburo condemned those philosophers who do not carry out in their work the "partisanship of philosophy and natural science", and thereby "resurrect one of the most harmful traditions and dogmas of the Second International - the gap between theory and practice, sliding down in a number of important questions on the position of Menshevik idealism” [14].

In the same 1931, the new People's Commissar of Medicine M. Vladimirsky, who replaced N. Semashko in this post, criticized psychiatrists for daring to talk about some kind of “acquired mental disability” that threatens party workers who give too much work. Putting such concepts as party work and mental illness in one logical series, psychiatrists risked discrediting the sacred image of a communist, who theoretically can “burn out at work”, but is not capable of being damaged by the mind under any circumstances [15].

Doctors, according to Vladimirsky and his colleagues, pour water on the mill of enemies who want to slow down the pace of the Great Turn. Instead of raising the morale of citizens, they sow fear of imaginary difficulties.

N. Grashchenkov (acting People's Commissar of Health after the arrest of M. Boldyrev in 1938) condemned mental hygiene as a bourgeois phenomenon that has no place in Soviet medicine. Because of the mental hygienists, the motivation of workers weakens precisely when the workers need moral strength for "invigorating collective work. "

"

M. Krol (Director of the Clinic for Nervous Diseases of VIEM) questioned the meaning of preventive psychiatry in a country where no social risk factors exist. The mental health of workers and peasants is guaranteed by their devotion to work. The nervous system of a Soviet person, according to the logic of M. Krol and N. Gerashchenkov, heals itself in the process of building communism.

In 1932-33 psychiatrists are discussing completely different epidemiological data, not those that gave medical examination 1920 years The picture of mental health in the view of specialists like M. Krol looked very good, and the incidence of mental illness was declining [16].

There are no social prerequisites for mental illness in the Soviet country, but there are “remnants of capitalism” mentioned by Stalin at the 17th Congress. “People's consciousness in its development lags behind their economic situation” [17] – this Stalinist formula crosses out the program of Soviet preventive psychiatry. People actually live well, and if their psyche suffers for some reason, it is because of the remnants of capitalism.

People actually live well, and if their psyche suffers for some reason, it is because of the remnants of capitalism.

In 1931, Rosenstein and his associates were accused of two major sins.

Firstly, psychoprophylactic activity has developed too widely and has gone beyond the boundaries of psychiatry as such. Instead of patiently listening to the ravings of a psychotic in a hospital ward, psychiatrists suddenly began to behave like experts in social matters, and thus entered into the realm of the exclusive rights of the party and government. There should be no expert assessment of Soviet life independent of the party's opinion.

For the same reasons, pedology was persecuted at the same time. Pedologists loved to test schoolchildren. In their opinion, learning ability and other qualities can be assessed using objective methods. The test results, to the chagrin of party functionaries, did not fit into the official version of reality. The children of intellectuals received higher grades than the children of workers. From a pedological point of view, when organizing the educational process, it is necessary to focus on the results of testing, but in this case it will not be possible to follow the political line of advancing representatives of the working class up the personnel ladder. Ranking people's abilities without taking into account their class origin and without coordinating test results with the party is not compatible with Soviet ideology.

The children of intellectuals received higher grades than the children of workers. From a pedological point of view, when organizing the educational process, it is necessary to focus on the results of testing, but in this case it will not be possible to follow the political line of advancing representatives of the working class up the personnel ladder. Ranking people's abilities without taking into account their class origin and without coordinating test results with the party is not compatible with Soviet ideology.

Psychohygenists' attempts to talk about the army were regarded as a manifestation of unacceptable impudence. Psychiatric expertise in this extremely important area for the state undermined the authority of the commissars and political officers. Psychiatrists said that deliberate sabotage in the army was not as common as neuropsychiatric problems, which occur in the military no less than civilians. But all the activities of the political instructor are based on the belief in the omnipotence of political propaganda, with the help of which you can always raise the morale of a fighter without resorting to the advice of doctors.

Besides, if you look closely, who was the source of inspiration for Soviet psychohygienists? American psychiatrist Alfred Meyer (founder of the Mental Hygiene Committee), that is, a representative of the bourgeois West alien to Soviet people. The difference between American social psychiatry and Soviet, by the way, is quite noticeable. In America, mental hygiene was understood as a system for maintaining a person's personal well-being. In the USSR, the psychiatrist had to take care, first of all, that the citizen did not lose his combat readiness and did not prematurely leave the detachment of builders of communism.

The second sin of psychohygienists follows the first. In the USSR, as in Western countries where this movement developed, doctors believed that they not only knew how to assess everyday life, but were able to indicate how to change the order in society. From the party point of view, it looks as if the intelligentsia is taking on the role of a learned auditor and teaching how the workers should live. But in a state in which, according to official declarations, the working class owns everything and rules everything, doctors should obey the workers, and not herd them like foolish sheep. The workers themselves know how to transform society, and if anything happens, the comrades from the party will prompt and help.

But in a state in which, according to official declarations, the working class owns everything and rules everything, doctors should obey the workers, and not herd them like foolish sheep. The workers themselves know how to transform society, and if anything happens, the comrades from the party will prompt and help.

Especially since the recommendations of psychohygenists were not always distinguished by the weight of evidence and mostly came down to good advice like “the sun, air and water are our best friends” or clumsy life wisdom like:

“If coitus is performed without any compulsion before going to bed, after a hard day, he is completely normal; coitus after sleep and morning - always excess” [18].

Among other things, psychohygienists raised the question of the optimal amount of individual labor costs in production. To save the psyche, you need to work as much as medical science determines, and no more. During the years of the First Five-Year Plan, this recommendation sounded out of place. Propaganda said that the Soviet people should work, focusing not on the optimal, but on the maximum level, which it is desirable to exceed.

Propaganda said that the Soviet people should work, focusing not on the optimal, but on the maximum level, which it is desirable to exceed.

Rosenstein accepted the changed situation and promised that he would leave healthy people alone, focusing on serious pathologies. However, “nervousness” was not difficult to drag into the realm of serious psychopathologies, leaving everyday problems such as poor nutrition, lack of heating in living quarters, and so on, in the care of the party.

As is known, the founding fathers of the doctrine of schizophrenia, Kraepelin and Bleuler, differed in regard to prognosis. Kraepelin believed that dementia praecox was incurable. Bleuler, expanding the concept of this disease, reduced the accuracy of diagnostic criteria and introduced the encouraging idea of a 20% cure rate. The main thing is to take up the patient as early as possible and then he will be among the schizophrenics who managed to recover. It remains only to understand by what signs to calculate these seemingly normal people in order to save them from a disabling disease.

A few months after Rosenstein was pulled out of the People's Commissariat of Health, he declared that the MHP forces should be thrown into the diagnosis of "mild schizophrenia" [19]. Previously, such patients would have been diagnosed with "nervous exhaustion" or something like that. But Rosenstein took a closer look at the patients and saw something schizophrenic in their behavior. In the bourgeois West, they would have developed schizophrenia long ago, but socialism stops the course of the disease, holding it back at a “mild” stage.

It turns out that the incidence of borderline disorders does not speak of the shortcomings of Soviet society, but, on the contrary, of the preventive power of socialism. Indeed, under capitalism, those who are diagnosed with “mild schizophrenia” by Soviet psychiatrists (so mild that it can be confused with character traits) would have their psyches collapsed immediately and hopelessly.

“Mild schizophrenia” in the 1930s becomes a popular diagnosis. In Leningrad, this diagnosis is in 31% of patients in hospitals, in Moscow - in 51%. In one Moscow hospital - 81%. K 19In 1936, overdiagnosis of schizophrenia became so widespread that psychiatrists complained that psychiatry was turning into “schizophrenology” [20].

In Leningrad, this diagnosis is in 31% of patients in hospitals, in Moscow - in 51%. In one Moscow hospital - 81%. K 19In 1936, overdiagnosis of schizophrenia became so widespread that psychiatrists complained that psychiatry was turning into “schizophrenology” [20].

The situation with overdiagnosis improved, and by 1940. Soviet psychiatry settled on the fact that it was impossible to classify people with an unusual personality as schizophrenics.

The bias towards overdiagnosis became possible because Rosenstein was a typical representative of the phenomenological tradition, a follower of Jaspers and Husserl. He was a psychiatrist, for whom the main material for analysis is the narrative of the disease provided by the patient. The phenomenological approach assumes that the psychiatrist has a developed ability to "read" this narrative, finding signs of pathology, among which there may be completely imperceptible "microsymptoms", as Rosenstein called them.

The problem with phenomenological psychiatry is that the level of genius among psychiatrists always varies greatly. Rosenstein, according to eyewitnesses, had a unique talent for talking with a patient. But many Soviet psychiatrists obviously did not have such a talent.

The turn from a more phenomenological approach to a more biological one is partly explained by the fact that phenomenological psychiatry, with its broad, non-concrete approach to illness, led psychiatrists into temptation and encouraged them to deal with the interpretation not only of mental phenomena, but also of social reality.

After Rosenshtein's death, the task of the Soviet psychiatrist was formulated - to look for physiological markers of schizophrenia and come up with a treatment for the organic causes of schizophrenia [21].

Another prominent preacher of mental hygiene, Vasily Gilyarovsky (1875-1959), actively participated in the apparatus squabbles of the 1930s, from which he emerged as one of the main organizers of Soviet psychiatry. He worked as the director of the VIEM psychiatric clinic, which later became the Institute of Psychiatry of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences. At 19In 1947, when the issue of excluding the Institute of Psychiatry from the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences was raised, it was Gilyarovsky who was given the role of a lawyer for psychiatry. They wanted to remove the Institute from the Academy, because the authorities became more doubtful about whether psychiatry is a medical discipline [22].

He worked as the director of the VIEM psychiatric clinic, which later became the Institute of Psychiatry of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences. At 19In 1947, when the issue of excluding the Institute of Psychiatry from the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences was raised, it was Gilyarovsky who was given the role of a lawyer for psychiatry. They wanted to remove the Institute from the Academy, because the authorities became more doubtful about whether psychiatry is a medical discipline [22].

As in the case of overdiagnosis and psychoprophylaxis, the Stalinist government got into this topic not out of devotion to scientific truth. In 1947, a wave of struggle against bourgeois culture and groveling before the West swept over medicine. Around the fact of the publication of the work of Soviet doctors abroad, the Klyuev-Roskin Case was inflated, followed by the arrest of the president of the Academy of Medical Sciences and other personnel and organizational measures. The new medical leadership was supposed to do what the partocrats did at the beginning of the 1930 years - Strengthen the influence of party membership in psychiatry. The apotheosis of the campaign for the ideologization of psychiatry was the Pavlovian sessions, which canonized Pavlov's teachings as an unshakable truth and a source of answers to all questions.

The apotheosis of the campaign for the ideologization of psychiatry was the Pavlovian sessions, which canonized Pavlov's teachings as an unshakable truth and a source of answers to all questions.

The Institute of Psychiatry was removed from the Academy and subordinated to the Ministry of Health in 1949, because, in the opinion of the high authorities, there is nothing truly fundamental in psychiatric science. Everything fundamental is contained in the teachings of Pavlov, and psychiatry deals with the treatment of people and nothing more.

At last it was legally, ex cathedra, proclaimed what is to be considered the Marxist theory of the psyche. In the 1920s different psychological schools, which at first felt free in the USSR, like bridegrooms for a bride, fought for recognition of their own unique compatibility with Marxism. Everyone wanted to be Marxist psychologists.

There was the same problem with Marxist psychology as with Marxist genetics, it had to be invented out of nothing, forcibly inscribing the science of the psyche into Marxist political economy. But at 1920 years it was a relatively free process, and, moreover, completely unsuccessful; no unified Soviet, Marxist doctrine of the psyche and psychopathology was created. In the 1930s the party ordered that the theory that could be declared the only true one be named.

But at 1920 years it was a relatively free process, and, moreover, completely unsuccessful; no unified Soviet, Marxist doctrine of the psyche and psychopathology was created. In the 1930s the party ordered that the theory that could be declared the only true one be named.

But things did not go beyond “quoting”, that is, cluttering up psychological texts with extracts from Marx, Engels and Lenin. Pavlovian sessions 1950-51 put an end to this difficult matter.

This is a rather interesting topic, how and why Pavlov was elevated to the pedestal of the author of the only theory of the psyche adequate to Marxism. To begin with, Pavlov in the 1920s. fronded, and only towards the end of his life did he become defiantly loyal to the Soviet regime. In the 1920s and at the beginning 1930s Pavlov was often criticized as an insufficiently Marxist scientist who strives to reduce everything to physiology, as if there is nothing but physiology. In this sense, Pavlov was simply more honest about Marxism than other Soviet scholars of the day. By not confusing reflexology and Marxism, he thereby expressed respect for the existence of boundaries between the study of society and the study of the central nervous system. Why waste time on intellectual acrobatics, invent a Marxist doctrine of higher nervous activity, if Marx himself believed that the only psychology, that is, the only area where the inner world of man is scientifically studied, is “the history of industry and the emerging objective existence of industry” [ 23].

By not confusing reflexology and Marxism, he thereby expressed respect for the existence of boundaries between the study of society and the study of the central nervous system. Why waste time on intellectual acrobatics, invent a Marxist doctrine of higher nervous activity, if Marx himself believed that the only psychology, that is, the only area where the inner world of man is scientifically studied, is “the history of industry and the emerging objective existence of industry” [ 23].

Soviet government 1930s stopped the free development of preventive psychiatry and intervened in the delicate problem of overdiagnosis, damaging science and society. The plot of overdiagnosis in Soviet psychiatry is usually referred to in connection with the history of Soviet “punitive psychiatry” – the use of medicine to suppress free thought in the country. However, as the history of an earlier period shows, the mutual position of power and psychiatry in the USSR was not always the same, and the forms of control over the scientific community changed over time.

The ambitions of the psychohygienic direction and, more broadly, of the autonomous psychiatric community provoked an administrative response in the style of the time. Psychiatry was covered a little by . In 1928-31. 16 scientific journals devoted to neuropsychiatric problems were published. By 1934, this area of scientific creativity was reduced to a minimum. In the next 20 years, there were published:

0 journals about psychology,

0 journals about psychoneurology,

1 journal about psychiatry (“Journal of neuropathology and psychiatry”, not counting the journal “Soviet psychoneurology” published before 1941),

1 journal about pedagogy (“Soviet pedagogy”) [24].

The science of the psyche comes to life after the death of Stalin

Sources :

1 – Sirotkina I.E. Psychopathology and Politics: Formation of Ideas and Practice of Psychohygiene in Russia. Questions of the history of natural science and technology. 2000 #1.

Questions of the history of natural science and technology. 2000 #1.

2 – Oosterhuis H. Outpatient psychiatry and mental health care in the twentieth century: international perspectives. (ed. by M. Gijswijt-Hofstra and H. Oosterhuis) Psychiatric Cultures Compared: Psychiatry and Mental Health Care in the Twentieth Century. Amsterdam University Press, 2006

3 – ibid.

4 – Rozenshtein L. M. Psychiatry and prevention of neuropsychic health. Proceedings of the First All-Union Congress of Neurologists and Psychiatrists. M.-L.: State. medical publishing house, 1929. pp. 180–197

5 – Yu. Kannabikh “History of Psychiatry”

6 – Rosenstein L. M. op. cit.

7 – Yu. Kannabikh op.cit

8 – Dufaud G. New approach to madness: the development of the outpatient psychiatry in Soviet Russia in the 1920s and in the early 1930s. History of Medicine. 2015. Vol. 2. No. 3.

9 – Zajicek B. Soviet Madness: Nervousness, Mild Schizophrenia, and the Professional Jurisdiction of Psychiatry in the USSR, 1918–1936. Ab empire. 2014 №4

Ab empire. 2014 №4

10 – Everyday Life in Early Soviet Russia. (ed. by C. Kiaer and E. Naiman) Indiana University Press, 2005

11 – Joravsky D. The construction of stalinist psyche. (ed. by S. Fitzpatrick) Cultural revolution in Russia 1928-1931. Ontario, 1978

12 – Rosenstein L. M. op. cit.

13 – Rosenstein L. M. op. cit

14 – Kolman E.Ya. Politics, economics and mathematics // To fight for materialistic dialectics in mathematics. Ed. E. Kolman M. 1931 S. 53

15 – Decree of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks on the journal “Under the Banner of Marxism”. (Approved by the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks on January 25, 1931)

16 – Joravsky D. op. cit.

17 - Stalin I.V. Report to the 17th Party Congress on the work of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks. January 26, 1934

18 - Gilyarovsky V. Psychohygiene and psychoprophylaxis.