Mental asylums today

A Peek Inside the Modern Asylum

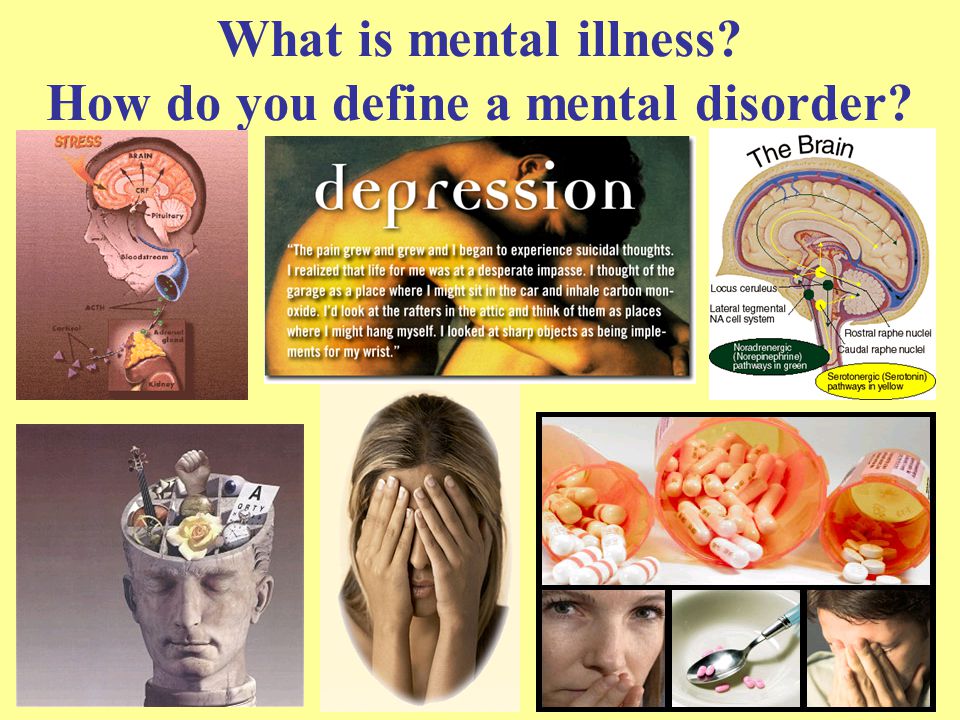

The psychiatric hospital of today might appear as a foreign, scary object to the mind who has never visited the institution. It represents the unknown, the territory that one is terrified of, but at the same time attracted to with natural human curiosity. Let’s be frank here: we want to know what is inside and who is “hiding” there.

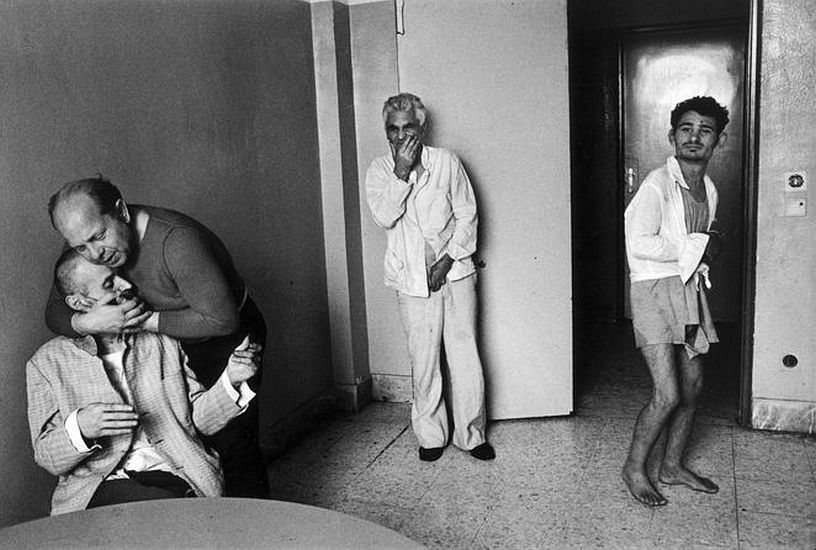

In the eighteenth century, in Europe, many mental institutions called “asylums” were open to the public. In exchange for some entrance money, interested visitors could have a peek: they could stroll in the corridors and observe the patients inside. It was a popular destination by all accounts. People found “madness”—or rather, what is assigned to the term—interesting and irresistible.

Michel Foucault wrote about it extensively, presenting a picture of a typical Sunday morning in Paris for a middle-age couple. They wake up, have breakfast, and then go for a visit to a local asylum for entertainment. Doors were open to the eager public, and the asylums never lacked in visitors.

It is indeed interesting, and probably more attractive than going to a theatre or the modern cinema. People aren’t acting there, and they are real.

Today, that same curiosity about manifestations of “madness” is satisfied via books or, more often, via movies. It isn’t by accident that such movies as Girl, Interrupted and A Beautiful Mind were such a big success: “madness” has always been fascinating, and will always attract and terrify the human mind at the same time.

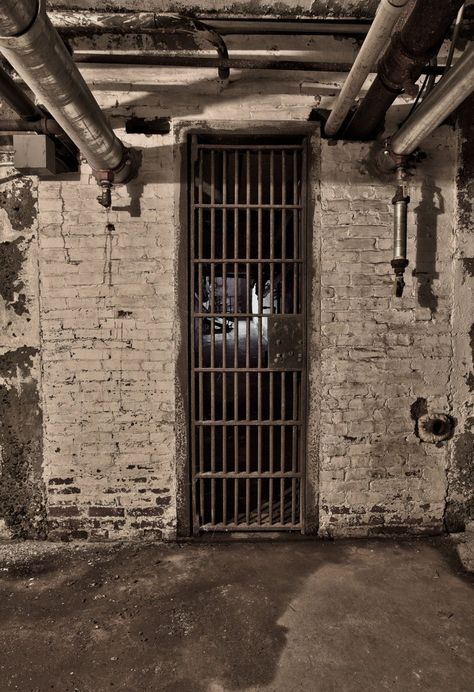

But let’s look at the psychiatric institution of today. It isn’t by accident that doors to it are closed to the curious mind, and only those who are unlucky end up being inside, on the wrong side of the equation—being a patient. The psychiatrists are the ones who walk really free there, looking, observing, analyzing, and then administering the cocktail of modern drugs. We read some stories, we get some news, but it is all presented to us as “mental illness,” part of the bigger discourse on “mental health.”

We read some stories, we get some news, but it is all presented to us as “mental illness,” part of the bigger discourse on “mental health.”

These stories hide the truth of the modern psychiatric narrative: that real, nice people end up there, and the psychiatric experience is likely to ruin one’s life for good. The drugs they prescribe don’t help with anything, and the stigma which gets attached after one receives a label or diagnosis is forever a scarlet letter on one’s life CV.

I have been unfortunate enough to deal with the psychiatry from “inside” and thus, am an unfortunate witness to the horrors behind the machine. I am also an academic and thus, am interested in the narrative—how my own personal story becomes part of a bigger picture. My story is unique, as are many others, but we all become just statistics in the psychiatric tale. We are all “patients” and we are all “insane.”

The mental health narrative of today is the continuation of the history of the psychiatry, beginning with the age they call “enlightenment,” when the doors were closed to the curious, and only the patients and treating “doctors” were allowed inside. I am not sure it was done out of good will, because it banned the witnesses of the injustices happening there. It is really taking the truth out of the terrifying tale hidden in the modern mental health narrative. People are often held against their will inside these institutions, though their only “crime” is that they dared to have weird thoughts or hear voices.

I am not sure it was done out of good will, because it banned the witnesses of the injustices happening there. It is really taking the truth out of the terrifying tale hidden in the modern mental health narrative. People are often held against their will inside these institutions, though their only “crime” is that they dared to have weird thoughts or hear voices.

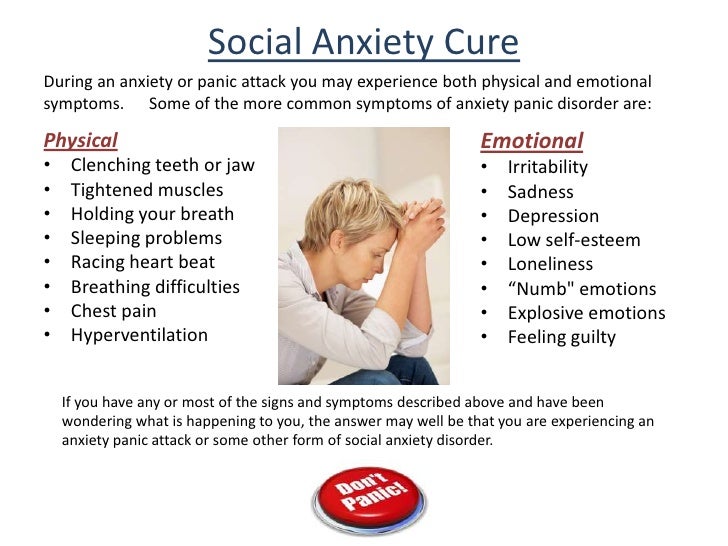

The modern mental health narrative is the recycling of the psychiatric song to present it to us as something innocent, mundane and even good. Yes, we should think about the sanity of our minds, take care of our bodies, sleep, eat well, and exercise our bodies and minds. However, this tale that appears innocent hides the fact that it simply scares people into a pattern of normality. A pattern where everyone should be the same, behave the same way, and do the same things as everyone else: think about which car to purchase, where to spend the next holiday, and whether to swipe left or right on Tinder. Once you start questioning the so-called normality of student loans, paying mortgages, marriage, kids, gym membership and the like, you will exhibit “abnormal” behavior, I can guarantee you that. You will start questioning things and stop and wonder: Why are there so many homeless people on the streets? Why is Africa so poor? How can I think of the next holiday when there is so much poverty in my otherwise rich land?

You will start questioning things and stop and wonder: Why are there so many homeless people on the streets? Why is Africa so poor? How can I think of the next holiday when there is so much poverty in my otherwise rich land?

Your weird thoughts will scare you, and you might become what they call “depressed.” Depression is definitely not an illness, but it is a fact. It is nothing else but a natural reaction of a mind that wants more from life than the boring tale of “normality.” If you dig deeper, you might even get onto the scale of what they call “bipolar,” and if you embrace your weird thoughts with zeal, and voices finally reach you (the real spirit world hiding behind our “normality” narrative disguised as “the age of reason and enlightenment”), then you might get the label of “schizophrenic.”

All these labels are just words invented by the twisted tale of psychiatry to deceive our minds and prevent us from thinking and behaving differently. There is no mental illness, and there never was. People simply get unwell, and bad things happen in life.

People simply get unwell, and bad things happen in life.

But the psychiatric institution of modern times, with its closed doors, lingers on top of our minds as the forbidden bad fruit that no one should touch, terrifying us and scaring us, because let’s be frank and honest here: no one wants to end up there. And not because one is afraid to become “ill” (we are all prone to “madness,” let me assure you), but because of the narrative of mental health.

Trump demonstrated the scariness of the narrative to perfection when he condemned all “mentally-ill” people. He showed how strong the stigma is and that the slogan “mental illness is like physical illness” is just words into the air. Trump demonstrated the real attitude toward people with “mental illness.” He simply doesn’t know who they are, and what is really taking place—behavior and thought control by the psychiatric institution.

And only a few of us know and see the truth.

The psychiatric institution is mostly an abstract body hanging over our head, sort of a bad headmaster telling us what to do and how to act—a behavioral control manager. It terrifies us with its promise of inflicting a label on the innocent mind, but at the same time, lures us for a peek inside.

It terrifies us with its promise of inflicting a label on the innocent mind, but at the same time, lures us for a peek inside.

Today we don’t have the possibility for a peek inside, but we remain, nevertheless, very curious. We do wonder what is taking place inside, who is held inside, and what it looks like. Mental health patients are your biggest celebrity story, hidden behind the bars of the psychiatric system, which doesn’t want to reveal its badly written script.

I was once inside and thus, am inviting you to have a look. I will take your hand, and encourage you to join me, on an exploration of the inside of the psychiatric institution.

Let’s open the door.

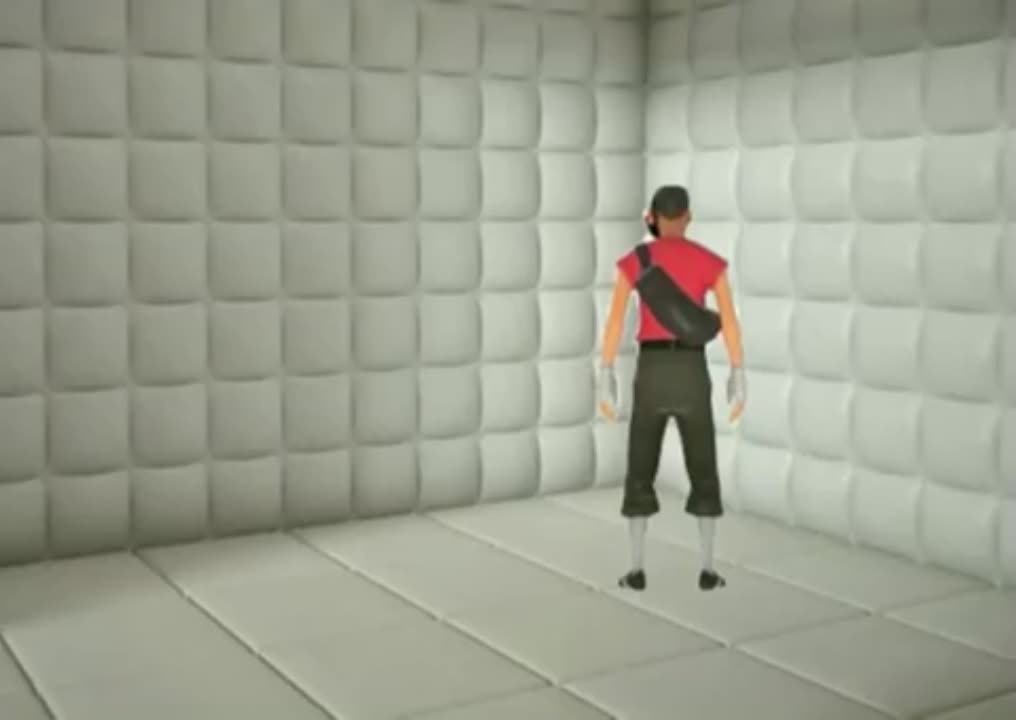

Once we manage it (and it isn’t easy as the doors are really locked), we proceed along a corridor. Psychiatric hospitals operate according to the principle of the panopticon, as Michel Foucault describes in his brilliant book, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. He tells us about the emergence of the modern prison system, operating according to the principle of surveillance. “He is seen, but he does not see; he is an object of information, never a subject in communication,” Foucault tells us, referring to the fact that in our current behavior surveillance system, we act like everyone else due to fear of being observed and punished if we do something wrong. The panopticon has a structure: you have a central vintage point through which you can see everything, scaring the subjects into compliance. The subject is always observed.

“He is seen, but he does not see; he is an object of information, never a subject in communication,” Foucault tells us, referring to the fact that in our current behavior surveillance system, we act like everyone else due to fear of being observed and punished if we do something wrong. The panopticon has a structure: you have a central vintage point through which you can see everything, scaring the subjects into compliance. The subject is always observed.

Modern psychiatry operates according to the same principle, and so do its facilities, such as mental health institutions. In each long corridor of its facilities you have a central point, where psychiatric nurses hold their watch. It is indeed a watch, and if you think that they provide care and show love, then you are wrong. Most of the time they write notes and if we glance inside the notes we will see the following: “Today M dressed more appropriately and was nice to the staff,” or “This morning G stopped his uncontrollable laughing and showed some insight into his behavior. ”

”

Trust me, school is a piece of cake to pass in comparison to what is happening in the notes and observation techniques of the staff in psychiatric hospital, and none of them ever shows any insight or comprehension into their own idiocratic stance. They simply don’t know what they are doing and why, because of the system of the psychiatric establishment. Those who show any weird thought pattern or exhibit strange behavior should be put inside the mental health institution and be re-trained as to how to behave normally.

The nurses sit at their central point, visibly bored and annoyed. They don’t like the patients who come with constant demands, which are always the same and don’t change. “Can I go out, please?” “Can I have a bath?” “Can someone, please, take me on a walk?” “Can I call my friend R?” “When can I see the doctor?” “When will I be discharged?” These are the irritating demands of the patients, taking the attention of nurses away from their notes—and notes take most of their time and attention, because of someone out of their mind who invented psychiatry: it isn’t the patient that matters, but what is written about him/her in the notes. The notes are shown to the treating psychiatrist and stored on shelves, although no one will ever glance a second time into the books and volumes describing us, describing the behavior of those unfortunate enough to step outside the scales of normality.

The notes are shown to the treating psychiatrist and stored on shelves, although no one will ever glance a second time into the books and volumes describing us, describing the behavior of those unfortunate enough to step outside the scales of normality.

But let’s move away from the central post and look at the room next to it. It is a room with a phone, where patients queue (when they are allowed) to make a call, and where the treating psychiatric consultant deals with the patients, if other rooms are occupied. It is a small, stinky room, with a closed window, where both the consultant and his patients feel suffocated and mal-at-ease. The doctor doesn’t want to be there, it is the patient who asks to see him again and again, with the same annoying demand as always: “When can I go home?” she asks.

You might think it is funny, but it isn’t funny at all for the patient on the wrong side of the equation. The power machine is firmly in the hands of the consultant psychiatrist and only he can decide on your fate. And it is indeed a fate: one day longer and the patient can be driven to such a despair that he will try to take his life. And if this happens, the cycle becomes much longer, because in that case, the patient is proclaimed as a risk to himself, and is kept behind the doors for much longer. Then it is just survival instinct that might save the patient and give her the strength to endure it all longer.

And it is indeed a fate: one day longer and the patient can be driven to such a despair that he will try to take his life. And if this happens, the cycle becomes much longer, because in that case, the patient is proclaimed as a risk to himself, and is kept behind the doors for much longer. Then it is just survival instinct that might save the patient and give her the strength to endure it all longer.

Let’s walk away from the room and have some fresh air—in the garden that is usually present (thank god) in the facilities. The garden is used for the patients to have a cigarette and to pray. It is here that most interesting conversations take place, away from the observational post of the nurses. It is here that they dare to quickly exchange their own thoughts, such as sharing the voices they hear and the visions they see. It is here that they also get advice from someone who is more advanced in their knowledge of the panopticon, such as, “Don’t say all this to the doctor.” One needs to comply, behave as normal as possible, and not reveal one’s mind to the psychiatrist. Following the rules also means being extra-nice to the nurses who are not nice back to you, wearing presentable clothes, and acting like you are at an office meeting, definitely not as if in the hospital, oh no. I feel much more relaxed in my working place than I ever was inside a psychiatric hospital.

Following the rules also means being extra-nice to the nurses who are not nice back to you, wearing presentable clothes, and acting like you are at an office meeting, definitely not as if in the hospital, oh no. I feel much more relaxed in my working place than I ever was inside a psychiatric hospital.

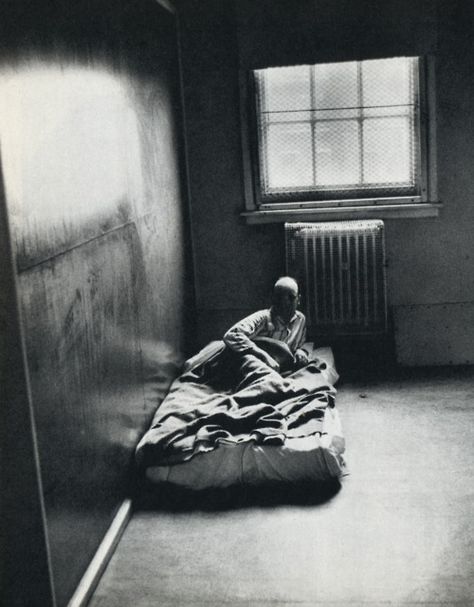

The psychiatric hospital of today, to conclude my narrative, is a panopticon, a modern prison for the daring mind and for weird behavior. We had a small peek, but in reality, it is much more distressing for the one who is being observed. In some hospitals they have cameras in the rooms to supervise the “patient,” and in some establishments, there are people who stay there for years, injected with drugs against their will, losing all hope and desire for living.

It isn’t funny, it isn’t entertaining, and it is bad.

But all who are lucky enough not to end up there march past this monstrosity, oblivious to the torture of the mind happening behind those walls.

***

Mad in America hosts blogs by a diverse group of writers. These posts are designed to serve as a public forum for a discussion—broadly speaking—of psychiatry and its treatments. The opinions expressed are the writers’ own.

These posts are designed to serve as a public forum for a discussion—broadly speaking—of psychiatry and its treatments. The opinions expressed are the writers’ own.

***

Mad in America has made some changes to the commenting process. You no longer need to login or create an account on our site to comment. The only information needed is your name, email and comment text. Comments made with an account prior to this change will remain visible on the site.

How Psychiatric Hospitals Have Evolved

Today’s psychiatric hospitals are quite different from the old asylums. The new goal: effective treatment with a short-term stay.

Psychiatric hospitals are specialized treatment facilities for people experiencing severe mental health episodes, such as psychosis, mania, or major depression.

Far from the asylums of the early 20th century, today’s psychiatric hospitals emphasize a short-term stay with highly advanced treatment options. Once clients have been stabilized and treated, they typically go home within a few days or weeks.

Once clients have been stabilized and treated, they typically go home within a few days or weeks.

A modern psychiatric hospital is the highest level of care for people with severe mental health symptoms. People who enter a psychiatric hospital may do so because they need help to:

- avoid harming themselves or another person

- monitor their behaviors during an acute episode and to stay safe

- receive an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan

- adjust or stabilize their medications

There are several types of psychiatric hospitals that offer 24-hour care:

- Psychiatric units within general hospitals (public or private). These separate units must have a specifically designated staff and space for treating people with mental health symptoms. The units may be within the hospital itself or in a separate building owned by the hospital.

- State-licensed private psychiatric hospitals. Along with 24-hour care, some of these hospitals may also offer outpatient services or partial hospitalization.

- State/public psychiatric hospitals. These hospitals provide short-term and long-term care to people who are unable to pay, for individuals requiring long-term care, and for forensic patients.

- Residential treatment centers (RTCs). These facilities are not licensed psychiatric hospitals, but the residents are still provided with mental health care. These include facilities for substance use disorders and behavioral concerns. RTCs for children must have a clinical program directed by a psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, or psychiatric nurse who has a master’s or doctoral degree.

A 2018 study found that of 129,115 clients who received mental health care in inpatient settings:

- 39% were in private psychiatric hospitals

- 31% were in general hospitals

- 26% were in public psychiatric hospitals

People may choose to check themselves into a psychiatric hospital, or they may be hospitalized involuntarily by a family member or a physician, or after an encounter with a first responder, such as a police officer or a paramedic.

Some facilities also offer partial hospitalization. These programs provide 3 or more hours of care, but clients do not stay overnight. For some people, partial hospitalization can act as an intermediate step between inpatient care and community care.

Modern psychiatric hospitals provide acute treatment to people with severe mental health symptoms, but the goal is often a short-term stay — usually only a few days or weeks until the person is stabilized.

This wasn’t always the case.

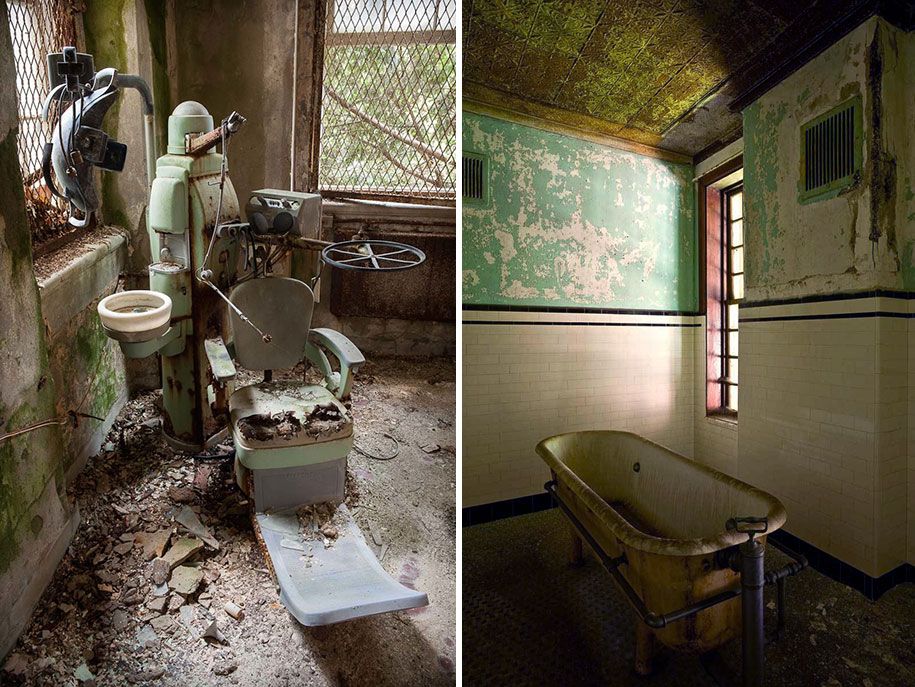

In the early 20th century, many people with severe mental health symptoms were placed indefinitely in large institutions known as asylums. These were often crowded and underfunded, and treatments at that time were essentially ineffective or even inhumane. Once a person entered these places, it was often very hard to get out.

By the early 1950s, the first antipsychotic medication, chlorpromazine, was introduced. It was soon followed by several more. These new antipsychotic drugs helped manage symptoms of psychosis, which allowed many people with severe mental health symptoms to live within their communities.

Within the next decade, a new system of mental health care — the community mental health system — slowly began to take the place of the old asylums. This model of care continued, and most mental health care is now provided by psychiatrists and therapists in outpatient clinics throughout the community.

Psychiatric hospitals still serve an important role and treat people with the most severe symptoms, but these institutions primarily play a short-term role in mental health care.

Each person’s experience in a psychiatric hospital will be different.

For some clients — especially for individuals who voluntarily admit themselves in — staying in the hospital may feel like a break from the extreme stressors of day-to-day life.

For others — particularly people who’ve been brought in during an acute episode, such as psychosis, mania, or major depression — the situation can feel quite frightening. But the staff will try their best to help alleviate the person’s fears and make them feel safe.

Many people experiencing an acute episode are taken to their local hospital’s emergency department, where they will be evaluated by a mental health professional. They may then be placed in a safe room where they’re monitored by a staff member until they’re given a placement, either in that hospital if it has a psychiatric ward or in another facility.

At first glance, a psychiatric hospital may seem relatively sterile in appearance, since decorations like plants or wall art may be considered a safety risk. On a more positive note, however, the facility is usually kept very clean.

Clients may be given their own rooms or share one with another person. Doors are often locked and clients are monitored frequently. Clothing is comfortable — this may involve scrubs or casual shirts and pants. Belts, shoestrings, hoodie strings, and similar items are not allowed.

Many psychiatric hospitals have a set schedule. The routine may involve regularly scheduled meals, recreational indoor and outdoor activities, visiting hours, group therapy, and a set bedtime.

Depending on the client’s length of stay, they will meet with a psychiatrist at regular intervals to discuss their treatment plan, as well as several multidisciplinary team members throughout their stay that may include mental health counselors, social workers, nurses, nurse practitioners, certified nurse assistants, and chaplains.

How long is the typical stay?

All psychiatric hospitals emphasize short-term stays. For example, in one 2019 research review, the average length of a hospital stay for a person with major depressive disorder was 6 days. Though, some people with severe symptoms may stay for long periods. For example, in this review, rehospitalization often occurred within 30 days of discharge.

Clients who voluntarily check themselves in may petition to leave within a day or two, even against medical advice. If the client came in involuntary, they will undergo an evaluation process to determine whether they’re able to care for themselves outside of 24-hour care.

Every facility has different policies and procedures, but discharge typically depends on a few factors:

- medication compliance

- sleeping

- eating

- showering

- lack of condition-specific symptoms

These factors weigh-in on how soon a client is discharged. The doctors and staff want to make sure each person is safe and not a danger to oneself or others before they leave.

If you’re currently experiencing a mental health crisis, please don’t hesitate to reach out to a mental health professional today.

If you feel that a psychiatric hospital is the best option for you right now, try to remember there’s no shame in asking for help and you’re not alone. About 2.2 million people in the United States received inpatient services in 2020.

The doctors and staff in these facilities are trained to deliver the most advanced treatments possible to help you feel better and stay safe.

Official website of GBUZ SO Psychiatric Hospital 3

Psychiatric Hospital No. 3 State Autonomous Healthcare Institution of the Sverdlovsk Region

3 State Autonomous Healthcare Institution of the Sverdlovsk Region

In the first person

"We, psychiatrists, in our practice are still faced with the fact that in the public mind a negative image of any psychiatric institution, leading to the unattractiveness of visiting a psychiatrist, narcologist, psychotherapist, even with the existing symptoms of the disease.The best image and a greater degree of trust have various non-scientific specialists - healers, psychics, etc.

Today, I see the formation of a more relevant image of the hospital as one of the main tasks for myself and my colleagues - it is a modern medical institution that provides a wide range of highly professional care in accordance with federal standards and recommendations, including being guided by international practice. And this is how I see Psychiatric Hospital No. 3.

Chief Physician of the Psychiatric Hospital No. 3, Anton Alexandrovich Tokar

3, Anton Alexandrovich Tokar

News of the Psychiatric Hospital No. 3

RULES FOR ACCEPTANCE OF FOOD TRANSFERS

- in clean packages, indicating: Full name patient, department, delivery date;

- products are accepted strictly in their original packaging and in accordance with the list;

- delivery of grocery transfers to stationary departments is carried out according to the schedule:.

Hotline of the Ministry of Health of the Sverdlovsk Region

8-800-1000-153

From December 1, 2019The hotline of the Ministry of Health of the Sverdlovsk Region operates around the clock without holidays and weekends.

This contact center was created to improve the quality and accessibility of medical care and allows you to provide citizens with the information they are interested in. For communication with specialists, the following numbers are provided:

1. "Hot line" of the Ministry of Health of the Sverdlovsk Region - 8-800-1000-153;

"Hot line" of the Ministry of Health of the Sverdlovsk Region - 8-800-1000-153;

2. A single telephone line for the spread of a new coronavirus infection - "122";

3. Interdepartmental Contact Center "Health of the inhabitants of the Middle Urals" - 8-800-234-0000.

Calls are also transferred to "hot lines" of state and municipal medical organizations located in the territory of the Sverdlovsk region.

We remind you that citizens of the Sverdlovsk Region can use the Hotline to:

- make an appointment with a doctor in medical organizations subordinate to the Ministry of Health of the Sverdlovsk Region;

- consult on the organization and quality of medical care;

- consult on issues related to compulsory health insurance;

- to consult on drug supply issues;

- consult on the procedure for referral to receive high-tech medical care and the status of a coupon for receiving high-tech care;

- to consult on the issues of anesthesia of people with cancer;

- to consult on the issues of "Health of the inhabitants of the Middle Urals".

Call Center operators advise citizens around the clock on a free phone number: 8-800-1000-153.

10 departments

370 beds in the hospital

100 beds in the day hospital

72 doctors

© 2017 uKit

News - Tomsk Clinical Psychiatric Hospital

Important information for patients from other regions of the Russian Federation

04/14/2023 The week of the World Health Day has ended

The week dedicated to the International Health Day has ended at the OGAU "TKPB". In the period from 04/06/2023 to 04/13/2023, the hospital held events dedicated to this issue, in which more than 290 people took part.

04/06/2023 World Health Day

Annually, April 7, on the day of creation at 19The 48th year of the World Health Organization is World Health Day. The annual health day has been a tradition since 1950.

The issues of maintaining and strengthening health in modern conditions of life are especially relevant.

Each year, WHO selects a global health theme that is relevant to all of humanity. Over the years, the themes of World Health Day have been the fight against mental illness, the promotion of an active lifestyle, the safety of motherhood and the impact of climate change on people's health.

The theme for World Health Day 2023 is Health for All. The hospital will host events dedicated to International Health Day, which will be attended by hospital staff, patients and their relatives.

04.04.2023 Action "Thank you doctor!"

The social action "Thank you doctor!" started in the Tomsk region

Residents of the Tomsk region will be able to leave thanks to doctors, nurses, pharmacists and pharmacists up to 9June.

Social action "Thank you doctor!" has been held in the Tomsk region since 2010. In 2022, residents of the Tomsk region left 16,269 "thanks" to doctors, nurses, pharmacists and pharmacists in the region. Thanks were received by 154 regional, federal and private medical institutions and pharmacies, 1780 medical workers, pharmacists and pharmacists.

Thanks were received by 154 regional, federal and private medical institutions and pharmacies, 1780 medical workers, pharmacists and pharmacists.

“We once again invite the residents of the Tomsk region to take part in this good action and thank their favorite doctor or pharmacist on the eve of their professional holiday. We know that the most important reward for people in white coats is an ordinary human thank you,” Svetlana Malakhova, director of the regional center for medical and pharmaceutical information, invited to participate in the action.

Each gratitude from the patient is counted as a vote cast by them for the institution or its employee. The institutions and professionals with the most votes will be the winners. The winners will be determined in five nominations: "People's Doctor", "People's Nurse", "People's Pharmacist", "My Favorite Hospital", "My Favorite Pharmacy". The award will take place on the eve of the Medical Worker Day; The winners will receive valuable prizes from the partners of the contest.

You can say thank you on the promotion website or by calling 8 (3822) 516-616 and 8-800-350-8850 (toll-free). The organizer of the action is the regional center of medical and pharmaceutical information with the support of the health department of the Tomsk region.

http://spasibo.tabletka.tomsk.ru/

03/29/2023 Poll

The hospital administration asks citizens to complete a short survey on the provision of medical care and manifestations of corruption in healthcare institutions.

Survey on the issues of assessing the quality of outpatient, inpatient medical care and manifestations of everyday corruption. OGAUZ "Tomsk Clinical Psychiatric Hospital"

03.03.2023 Open reception, March 6

Within the framework of the Open Reception project

head doctor of the psychiatric hospital S.M. Andreev

March 6 from 17:00 to 19:00 will hold a reception of citizens

in the main building of the hospital at the address: Tomsk, st.