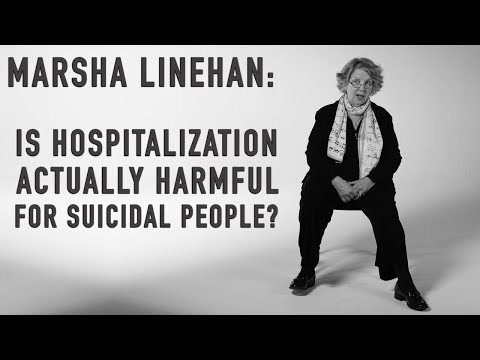

Marsha linehan story

Marsha Linehan Acknowledges Her Own Struggle with Borderline Personality Disorder

Dr. Marsha Linehan, long best known for her ground-breaking work with a new form of psychotherapy called dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), has let out her own personal secret — she has suffered from borderline personality disorder. In order to help reduce the prejudice surrounding this particular disorder — people labeled as borderline often are seen as attention-getting and always in crisis — Dr. Linehan told her story in public for the first time last week before an audience of friends, family and doctors at the Institute of Living, the Hartford clinic where she was first treated for extreme social withdrawal at age 17, according to The New York Times.

At 17 in 1961, Linehan detailed how when she came to the clinic, she attacked herself habitually, cut her arms legs and stomach, and burner her wrists with cigarettes. She was kept in a seclusion room in the clinic because of never-ending urge to cut herself and to die.

Since borderline personality disorder was not discovered yet, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia and medicated heavily with Thorazine and Librium, as well as strapped down for forced electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Nothing worked.

So how did she overcome this tragic beginning?

She was not much better 2 years later when she was discharged:

A discharge summary, dated May 31, 1963, noted that “during 26 months of hospitalization, Miss Linehan was, for a considerable part of this time, one of the most disturbed patients in the hospital.”

A verse the troubled girl wrote at the time reads:

They put me in a four-walled room

But left me really out

My soul was tossed somewhere askew

My limbs were tossed here about

She had an epiphany in 1967 one night while praying, that led her to go to graduate school to earn her Ph.D. at Loyola in 1971. During that time, she found the answer to her own demons and suicidal thoughts:

On the surface, it seemed obvious: She had accepted herself as she was.

She had tried to kill herself so many times because the gulf between the person she wanted to be and the person she was left her desperate, hopeless, deeply homesick for a life she would never know. That gulf was real, and unbridgeable.

That basic idea — radical acceptance, she now calls it — became increasingly important as she began working with patients, first at a suicide clinic in Buffalo and later as a researcher. Yes, real change was possible. The emerging discipline of behaviorism taught that people could learn new behaviors — and that acting differently can in time alter underlying emotions from the top down.

But deeply suicidal people have tried to change a million times and failed. The only way to get through to them was to acknowledge that their behavior made sense: Thoughts of death were sweet release given what they were suffering. […]

But now Dr. Linehan was closing in on two seemingly opposed principles that could form the basis of a treatment: acceptance of life as it is, not as it is supposed to be; and the need to change, despite that reality and because of it.

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) was the eventual result of this thinking. DBT combines techniques from a number of different areas of psychology, including mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and relaxation and breathing exercises. Research has demonstrated its general effectiveness for people with borderline personality disorder. She should be very proud of her work with developing and helping people learn about DBT:

In studies in the 1980s and ’90s, researchers at the University of Washington and elsewhere tracked the progress of hundreds of borderline patients at high risk of suicide who attended weekly dialectical therapy sessions. Compared with similar patients who got other experts’ treatments, those who learned Dr. Linehan’s approach made far fewer suicide attempts, landed in the hospital less often and were much more likely to stay in treatment. D.B.T. is now widely used for a variety of stubborn clients, including juvenile offenders, people with eating disorders and those with drug addictions.

Dr. Linehan’s struggle and journey is both eye-opening and inspirational. Although long, the New York Times’ article is well worth the read.

Read the full article: Expert on Mental Illness Reveals Her Own Struggle

Marsha Linehan Acknowledges Her Own Struggle with Borderline Personality Disorder

Dr. Marsha Linehan, long best known for her ground-breaking work with a new form of psychotherapy called dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), has let out her own personal secret — she has suffered from borderline personality disorder. In order to help reduce the prejudice surrounding this particular disorder — people labeled as borderline often are seen as attention-getting and always in crisis — Dr. Linehan told her story in public for the first time last week before an audience of friends, family and doctors at the Institute of Living, the Hartford clinic where she was first treated for extreme social withdrawal at age 17, according to The New York Times.

At 17 in 1961, Linehan detailed how when she came to the clinic, she attacked herself habitually, cut her arms legs and stomach, and burner her wrists with cigarettes. She was kept in a seclusion room in the clinic because of never-ending urge to cut herself and to die.

Since borderline personality disorder was not discovered yet, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia and medicated heavily with Thorazine and Librium, as well as strapped down for forced electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Nothing worked.

So how did she overcome this tragic beginning?

She was not much better 2 years later when she was discharged:

A discharge summary, dated May 31, 1963, noted that “during 26 months of hospitalization, Miss Linehan was, for a considerable part of this time, one of the most disturbed patients in the hospital.”

A verse the troubled girl wrote at the time reads:

They put me in a four-walled room

But left me really out

My soul was tossed somewhere askew

My limbs were tossed here about

She had an epiphany in 1967 one night while praying, that led her to go to graduate school to earn her Ph. D. at Loyola in 1971. During that time, she found the answer to her own demons and suicidal thoughts:

D. at Loyola in 1971. During that time, she found the answer to her own demons and suicidal thoughts:

On the surface, it seemed obvious: She had accepted herself as she was. She had tried to kill herself so many times because the gulf between the person she wanted to be and the person she was left her desperate, hopeless, deeply homesick for a life she would never know. That gulf was real, and unbridgeable.

That basic idea — radical acceptance, she now calls it — became increasingly important as she began working with patients, first at a suicide clinic in Buffalo and later as a researcher. Yes, real change was possible. The emerging discipline of behaviorism taught that people could learn new behaviors — and that acting differently can in time alter underlying emotions from the top down.

But deeply suicidal people have tried to change a million times and failed. The only way to get through to them was to acknowledge that their behavior made sense: Thoughts of death were sweet release given what they were suffering.

[…]

But now Dr. Linehan was closing in on two seemingly opposed principles that could form the basis of a treatment: acceptance of life as it is, not as it is supposed to be; and the need to change, despite that reality and because of it.

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) was the eventual result of this thinking. DBT combines techniques from a number of different areas of psychology, including mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and relaxation and breathing exercises. Research has demonstrated its general effectiveness for people with borderline personality disorder. She should be very proud of her work with developing and helping people learn about DBT:

In studies in the 1980s and ’90s, researchers at the University of Washington and elsewhere tracked the progress of hundreds of borderline patients at high risk of suicide who attended weekly dialectical therapy sessions. Compared with similar patients who got other experts’ treatments, those who learned Dr.

Linehan’s approach made far fewer suicide attempts, landed in the hospital less often and were much more likely to stay in treatment. D.B.T. is now widely used for a variety of stubborn clients, including juvenile offenders, people with eating disorders and those with drug addictions.

Dr. Linehan’s struggle and journey is both eye-opening and inspirational. Although long, the New York Times’ article is well worth the read.

Read the full article: Expert on Mental Illness Reveals Her Own Struggle

| About Marsha Linehan, creator of Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, an effective treatment for borderline personality disorder, and her struggle with her own disorder.

- Are you one of us? The patient wanted to know, and her psychotherapist, Marsha M. “That made all the difference,” says 68-year-old Dr. Linen, explaining why she decided to tell her story. “So many people begged me to perform, and I just thought I should do it. I am indebted to them, I can't die a coward." No one knows how many people with severe mental disorders live seemingly normal, successful lives, they rarely advertise the truth about themselves. They live to subdue the flurries of emotions and painful illusions that could easily overwhelm any other person. nine0014 Fortunately, today more and more of these people are taking the risk of giving away their secret. "We need to bust the myths about mental disorders, give these diseases a human face, show people that the diagnosis does not have to lead to a difficult, derailing life" - says Elyn R. What are these resources? These are drugs (usually), psychotherapy (often), a certain amount of luck (always) and, most importantly, the inner strength necessary to, if not completely expel your inner demons, cope with them. According to former patients, this strength can be born in many different places: in love, in forgiveness, in faith in God, in many years of friendship. nine0008 Dr. Linen was on a mission to save chronically suicidal people, often the result of borderline personality disorder, a mysterious condition characterized by self-destructive tendencies. “I honestly didn't realize at the time that I was trying to cope with myself” , she says. "I was in hell"She knows the hard way what a severe mental disorder is. Marsha Lainen entered the Institute of Life on March 9, 1961 at the age of 17 and soon became a regular visitor to the isolation ward in the department intended for the most critical patients. The staff saw no other way out: the girl constantly injured herself, inflicting cigarette burns on herself, deeply injuring her arms, legs, stomach, using any sharp object that she could reach. nine0008

There was nothing sharp in the isolation room, a small room with a bed, a chair and a tiny barred window. But her urge to die only grew stronger. Therefore, she did the only thing she could and what she saw sense at that time: she beat her head against the wall and, later, the floor. With all my might. “When this happened, I felt like someone else was doing it. Some clues came from her childhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma. An excellent student at an early age, a talented piano player, she was the third of six children of an oilman and his wife, a woman who combined childcare with the Junior League and Tulsa community events. People who knew the Linens at that time remember that their unpredictably developed third daughter often had problems. Dr. Linen herself recalls feeling deeply inferior in comparison to her attractive and successful siblings. But no matter how difficult the experiences that took place under the guise of apparent well-being, no one paid much attention to them until, in the last year of school, she was bedridden with terrible headaches. Her younger sister Aline Haynes says: “This was life in Tulsa in the 1960s, and I'm not sure my parents had any idea what to do with Marsha. Soon a local psychiatrist recommended that she be sent to the Institute of Life, where she was diagnosed with schizophrenia. She was treated with powerful drugs and psychoanalyzed, many hours of psychoanalysis. In addition, she was prescribed electroshock treatment. First, a course of 14 shocks, then the second - 16. This did not help, and soon the patient returned to the isolation ward of the supervision department. nine0008 “Everyone was afraid to end up there” , says Sebern Fisher, another patient at the hospital who became close friends with Marsha. "But no matter the setting" - , says Miss Fisher, - "Marsha was capable of great care for another person. Her passion was as deep as her loneliness." The discharge statement, dated May 31, 1963, states that "during her 26 months of hospitalization, Miss Linehan remained for most of the time one of the hospital's worst patients. Radical Acceptance She experienced the power of acceptance while praying in a small chapel in Chicago. It was 1967, several years had passed since she had left the institute, being a desperate twenty-year-old girl. Doctors gave her little chance of survival outside the hospital. There she went back to the hospital and became even more lost, alone and more devoted to her Catholic faith than ever. She moved to another camp, took a job as a clerk for an insurance company, began attending evening classes at Loyola University, and began to pray frequently at the Cenacle Retreat Center chapel. “I was kneeling there one night, looking up at the crucifix, and all of a sudden the whole space was filled with a golden glow — and suddenly I felt something come over me” , she says. — “It was such a fluttering feeling, and then I ran to my room and said, 'I love myself.' It was the first time in my memory that I spoke to myself in the first person. I felt like I had changed." The rise lasted for about a year, then the feeling of emptiness returned, becoming like an awakening from a novel. What has changed?It took her years of studying psychology to find the answer—and she received her Ph.D. from Loyola in 1971. On the surface, everything seemed obvious: she accepted herself for who she is. She tried to kill herself so many times because the gap between the person she wanted to be and the person she was plunged her into a desperate, hopeless, deep longing for a life she had never known. This abyss was real, and it was impossible to bridge over it. nine0008 This basic idea—she now calls it radical acceptance—became especially important when she began working with patients at the Buffalo suicide clinic and later in research work. Yes, real change is possible. Cognitive psychotherapy shows that people can learn new behaviors and new actions can change their underlying emotions over time. But people with borderline personality disorder have tried to change a million times and failed. “She was very creative. I saw it right away,” said Gerald C. Davison, who in 1972 accepted Dr. Linen into a postdoctoral fellowship in behavioral therapy at Stony Brook University. — "She could tell people what they didn't want to hear, and yet they didn't feel defeated." No psychotherapist can promise quick change, or "insight", and even more so, a bright religious insight. But now psychologist Linenan has groped for two seemingly contradictory principles that form the basis of treatment. The first principle is to accept life as it is, not as it should be. The second is the need for change, in spite of reality, but because of it. nine0008 Wandering through the days “I chose to work with hyper-suicidal people, very difficult cases, because they are the most miserable people in the world – they think they are evil itself, that they are very, very, very bad – and I understood that it was not so” , she says. She decided to treat people with a diagnosis she would have given herself - borderline personality disorder. This obscure condition is characterized by a need for emotional support, emotional outbursts, and self-destructive tendencies, often leading to self-cutting and burning. During psychotherapy, borderline patients can be terrifying—manipulative, hostile, sometimes eerily silent—and they are notorious for their violent demarches with suicide threats. nine0008 Dr. Linen has found that total acceptance at least helps keep patients in the office: patients accept themselves, accept their crazy rages, emptiness and anxiety, much more intense than most people. In turn, the therapist accepts that given all this, cuts, burns, and suicide attempts make sense. Finally, the therapist awakens in the patient the readiness to change his behavior, to make a verbal vow in exchange for a chance to live. But as she made her career and climbed the academic ladder, moving from the Catholic University of America to the University of Washington in 1977, she learned the hard way that acceptance and change are not always enough. During her early years in Seattle, she sometimes felt the urge to kill herself, and today she occasionally experiences flashes of panic, such as while driving through the tunnels. Over the years, she has occasionally turned to a psychotherapist for support and guidance (but has never taken drugs since the Life Institute). nine0008 Dr. Linen's treatment approach, now called Dialectical Behavior Therapy or D.B.T. (dialectical behavioral therapy), also includes teaching many skills. Willingness to change, after all, means little if people don't have the tools to implement it. She used behavioral therapy techniques and added many others. For example, the opposite action, when patients act opposite to what they want to do with inadequate emotions. In studies in the 1980s and 1990s, scientists at the University of Washington and elsewhere documented the success of hundreds of borderline patients who were at high risk of suicide and who received weekly sessions of dialectical psychotherapy. They made significantly fewer suicide attempts, were less likely to end up in hospitals, and were more likely to continue treatment than patients who received other types of psychotherapy. Now D.B.T. widely used to treat the most difficult clients, including juvenile delinquents, people with eating disorders, and drug addicts. nine0008 “I think D.B.T. has become so popular because it helps in what could not be treated before; when it came to borderline personality disorder, psychotherapists were at a loss,” says Lisa Onken, director of behavioral and integrative treatment at the National Institutes of Health. Perhaps the most remarkable thing is that today Dr. Linen can tell his story. "Now I'm very happy" , she says in an interview. She lives near the university where she works, along with her adopted daughter Geraldine and her husband Nate. "Of course, I still have ups and downs, but I think no more than others." After her public confession, she visited the same isolation ward, now converted into a small office. nine0015 "Wow, look, they changed the windows." she says, throwing up her hands. - "So it became much brighter" . New York Times article. Author - BENEDICT CAREY. Translation by Vladimir Snigur.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy training for people with bipolar disorder. In person and online. Read about a film about the psychotherapy of borderline personality disorder. Read about borderline personality disorder List of books written by or about those who have overcome mental or neurological illness. ©2015, Psychodynamics. When reprinting and copying texts, an active link to www.psychodinamica.ru is required. | |||||

|

Mom, we are in hell (but this is not certain). History of DBT, Part 1.

DBT - Dialectical Behavioral Therapy - is an evidence-based (i.e., scientifically proven) therapy method developed by American psychologist Marsha Linehan to treat people who were previously considered hopeless in psychiatry. These are suicidal patients with an irresistible, persistent need to commit suicide, substance addicts and alcoholics, bulimics with 4-5 or more attacks a day, those who constantly injure themselves - cut, burn, beat ...

These are suicidal patients with an irresistible, persistent need to commit suicide, substance addicts and alcoholics, bulimics with 4-5 or more attacks a day, those who constantly injure themselves - cut, burn, beat ...

DBT is a unique method of helping those who are commonly called people with borderline personality disorder, completely changing the idea of what borderline personality disorder is and how to help such people.

If it weren't for the uniqueness of Linehan's personality, her family, the historical period in which her formation took place, nothing like this would have been created. Marsha is not just an extraordinarily talented person, she is the one who has managed to melt her own problems into a system of helping others. In order to start saving other people, she first had to save herself. nine0008

MARSH

Marsha Linehan was born into a devout, strictly Catholic American family with many children, the third child of six. There is this strict, disciplined, self-sacrificing Catholic spirit in the DBT system. At a young age, Marsha discovers difficulties atypical for her brothers and sisters - she is an excellent student, plays the piano virtuoso, but constantly experiences such strong longing, despair and mental pain that the only thing that distracts her from this is burning her wrists with cigarettes and cutting herself ... In the end, her condition became so unbearable, and the need to die so strong, that she was admitted to a closed psychiatric hospital. nine0008

At a young age, Marsha discovers difficulties atypical for her brothers and sisters - she is an excellent student, plays the piano virtuoso, but constantly experiences such strong longing, despair and mental pain that the only thing that distracts her from this is burning her wrists with cigarettes and cutting herself ... In the end, her condition became so unbearable, and the need to die so strong, that she was admitted to a closed psychiatric hospital. nine0008

At the age of 17, Marsha Linehan experienced first hand what psychiatry was like in the early 60s - 14 sessions of electroshock therapy at the beginning, then 16 more (no effect), treatment with insulin coma, large doses of Thorazine and Librium, long classical analysis ( she never gets better), and, finally, spending many hours in an isolated room, where there is nothing with which she can injure herself - no cigarettes, no razors, no glass. Then she starts banging her head on the walls, on the floor. She is diagnosed with schizophrenia - because the diagnosis of "personality disorder" simply did not exist then. She will stay in the hospital for 26 months. Linehan will leave the hospital and never take a single antipsychotic pill again in her life. nine0008

She will stay in the hospital for 26 months. Linehan will leave the hospital and never take a single antipsychotic pill again in her life. nine0008

For many years, none of her patients and numerous students knew about her past. In 2011, at the age of 68, she gives a heartbreakingly candid interview with The New York Times in which she says, “I've been to hell. And I swore an oath: if I get out of here, I will come back and get the others out.” She will keep her promise.

Linehan is confident that what is happening to her is not unique - unlike many suffering people who assume that only they have experienced this torment - and devotes her life to developing a system of help for people like her. Not right away. First, after leaving the hospital, she will survive two suicide attempts, get a quiet job as a clerk and spend a lot of time in prayer. nine0008

One day while praying, Linehan experiences what she would later call "the practice of radical acceptance." Psychiatrists might call it a hallucinosis or oneiroid, religious people would call it a vision. “The room turned golden and I could feel the presence of something nearby,” Linehan says in an interview. Everything is changing. She feels love for herself. The anguish and despair do not disappear for good, but since then she has been able to endure them without cutting herself. After many years of studying psychology, Linehan herself will describe this process as accepting herself - the way she was. nine0008

“The room turned golden and I could feel the presence of something nearby,” Linehan says in an interview. Everything is changing. She feels love for herself. The anguish and despair do not disappear for good, but since then she has been able to endure them without cutting herself. After many years of studying psychology, Linehan herself will describe this process as accepting herself - the way she was. nine0008

Working as a clerk, she begins to study. Graduates with honors from the Loyola University Department of Psychology, earns a Ph.D. Those who experience an irresistible desire to commit suicide, those who were considered incurable. She collects various relaxation techniques, coping with unwanted emotions and selects the most effective ones, those that work for the majority of patients. She conducts research on people who experience life as a continuous stream of pain in order to better understand who they are, what is happening to them - and help them cope with it. Marsha does not aim to cure them - she changes the focus of psychotherapy and focuses on "survive". As a result, she creates a therapy that can be called a daily survival system for those who find life unbearable. nine0008

As a result, she creates a therapy that can be called a daily survival system for those who find life unbearable. nine0008

“She was very creative with people. She knew how to challenge them, telling them what they did not want to hear, so that they did not feel knocked down, ”one of her teachers later said.

As a theoretical basis for her system of therapy, Linehan proposes a biosocial theory, the essence of which can be described by the words “Mom, we are in hell (but this is not accurate).” Linehan makes compassion the center of her system. She refuses to interpret the behavior of these, often really insufferable, patients as "manipulative" and themselves as "unstable" and "unable to sustain relationships" Linehan says - what if they have no choice but to behave in this way?0008

BIO

Some people are born with green eyes. Some are left-handed. Some are homosexual. All these are variants of the norm, which are statistically less common than others. Some people are born hypersensitive to emotions.

Some people are born hypersensitive to emotions.

What does this mean?

1. From early childhood, these people have a psychophysiological response (reaction of the nervous system) to any emotional stimulus more often and more easily than everyone else. As Marsha writes, these are not "thin-skinned" people, they don't have any skin at all. nine0008

"Why are you so sensitive about everything?"

"Don't take everything so personally!"

"You make too much of it. put it out of your mind!"

If you have repeatedly heard something like this, then it is possible that you are a highly sensitive person.

2. Not only does this response come on too easily, it also lasts longer and declines more slowly than average. That is, when all other people have already reacted, the poor highly sensitive continues to experience the emotion. nine0008

"Calm down as much as you can!"

"When will you stop thinking about it?"

"You can't get so hung up on your feelings!"

If you've come to know yourself again, the likelihood that you're a highly sensitive person has just increased dramatically.

Meanwhile, the old women keep falling and falling - triggers that trigger emotional reactions appear constantly, throughout each day. In an ordinary person, these reactions look like this: a state of rest - a reaction to a stimulus - then again a state of rest. The poor high-sensitivity guy, who hasn't recovered from the previous stimulus, is already under the influence of the next one, and therefore the map of his emotional reactions looks like a cardiogram of a person in a state of heart attack, when all the monitors immediately begin to beep ...

This is an innate, biological trait, such as eye color, dominant hand choice, or preferred sexual identity. It cannot be changed. Highly sensitive people experience life as a constant series of painful events, as continuous suffering, and therefore look for ways to drown out emotions, stop feeling, which often use alcohol, drugs, overeating, cutting themselves or hurting themselves in other ways.

We will return to self-infliction of pain, but now let's analyze the social part of biosocial theory. nine0008

nine0008

SOCIAL

"Get together, rag!"

"Well, what are you doing?"

"If you study poorly, you will wash the floors!"

"Nothing to feel sorry for yourself!"

"And why are you whining - it's hard for everyone! Do you think it's not hard for me?"

If a highly sensitive person is placed in a stable, warm, and supportive environment, they will usually do well. He doubts himself, but relies on the faith of close people in him, he is afraid, but draws courage from the support of his relatives, but breaks down under the influence of strong feelings, but does not meet with condemnation and criticism. nine0008

Unfortunately, it is the other way around, and highly sensitive people are born into a disabled environment. It’s already difficult for them, they are already completely skinless, but in addition they find themselves among people who consider sensitivity a weakness, a manifestation of a bad character, spoiled.

A lesson in disability is easy to learn when faced with a child's first grief or failure. Ye was lucky in a sports competition. A deuce for an important test. The first love.

Ye was lucky in a sports competition. A deuce for an important test. The first love.

Maybe your favorite hamster has died. The child is crying uncontrollably. The mother doesn't know how to calm him down and feels angry and helpless - she feels like a bad mother as the baby cries. In annoyance, the mother throws him: "What, I suppose, when your grandmother died, you did not cry like that ?!" - How often do we ourselves, not knowing how to express sympathy, express reproach? - and resolutely throws the unfortunate rodent into the trash, hoping that the disappearance of the hamster solves the problem. nine0008

What does the child experience? What message is he getting?

"Your grief is not important."

"What you feel has no right to exist."

"There is something wrong with your feelings, they are wrong."

The child already feels his otherness, because he is highly sensitive. But now he knows for sure that something is wrong with him. What he feels is bad, wrong! It causes disgust, anger, annoyance in loved ones, close people! You need to immediately stop feeling it . .. But - how ?! nine0008

.. But - how ?! nine0008

Such a child will solve the problem of "stop feeling" for a long time, until he decides on psychotherapy. He will try to hide emotions, hide them, separate himself from them - and as a result he will completely lose both contact with emotions and the ability to regulate them. Then these strong, unregulated emotions will take control over him - sadness will become unbearable, jealousy terrifying, anger destructive. In relationships, at work or school, serious conflicts will increasingly occur - she swore at the dean, quarreled with a girl right on the street and hit her, although he loved more than life, without permission, took the car of her parents and crashed it ...

Everything will be melted down in a cauldron of hatred and despair - and emergency measures will be needed. Experiments with alcohol or drugs, self-cutting or burning with cigarettes, hunger strikes for several days, overeating, and suicide attempts will begin to end this continuous torment.

Linen of the University of Washington, has already prepared an answer. nine0014 — Do you mean did I suffer?

Linen of the University of Washington, has already prepared an answer. nine0014 — Do you mean did I suffer?  Saks (Elyn R. Saks), professor University of South Carolina Law School, author of a book about his own battles with schizophrenia ("The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness").

Saks (Elyn R. Saks), professor University of South Carolina Law School, author of a book about his own battles with schizophrenia ("The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness").  — “But the truth is that I have developed a method of psychotherapy that provides what I myself have needed for many years. I needed it, but I couldn't get it."

— “But the truth is that I have developed a method of psychotherapy that provides what I myself have needed for many years. I needed it, but I couldn't get it."  Something like "I know this is about to start, but I'm not in control, someone help me! God, where are you?" nine0017 she says. — “I felt completely empty, like the Tin Woodman. Not only could I not tell what was happening to me, but I could not understand it either.”

Something like "I know this is about to start, but I'm not in control, someone help me! God, where are you?" nine0017 she says. — “I felt completely empty, like the Tin Woodman. Not only could I not tell what was happening to me, but I could not understand it either.”  In fact, no one really knew what borderline personality disorder was.”

In fact, no one really knew what borderline personality disorder was.”  " Here is a poem written by a sick girl at the time:

" Here is a poem written by a sick girl at the time:  But she survived, albeit with difficulty: she had at least two suicide attempts: in Tulsa when she returned home, and another after she moved to Chicago to the Y.M.C.A. nine0015 to start over.

But she survived, albeit with difficulty: she had at least two suicide attempts: in Tulsa when she returned home, and another after she moved to Chicago to the Y.M.C.A. nine0015 to start over.  But something has changed. She was now able to weather her emotional storms without cutting or harming herself. nine0008

But something has changed. She was now able to weather her emotional storms without cutting or harming herself. nine0008  The only way to get through to them was to admit that their behavior made sense: the thought of death was a sweet release from suffering. nine0008

The only way to get through to them was to admit that their behavior made sense: the thought of death was a sweet release from suffering. nine0008  - "I understood their suffering, because I myself was there, in hell, not having the slightest idea how to get out of there" .

- "I understood their suffering, because I myself was there, in hell, not having the slightest idea how to get out of there" .  She puts it this way: "Psychotherapy does not work with those who have already died" .

She puts it this way: "Psychotherapy does not work with those who have already died" .  Or mindfulness meditation, a Zen technique in which people focus on their breath and watch emotions come and go without translating them into actions. (Now mindfulness meditation has become an important element in many types of psychotherapy.) nine0008

Or mindfulness meditation, a Zen technique in which people focus on their breath and watch emotions come and go without translating them into actions. (Now mindfulness meditation has become an important element in many types of psychotherapy.) nine0008  — “But the fact that she resonated with many professionals in our community, I think, has a lot to do with Marsha Linen’s charisma, her ability to connect with both clinicians and scientific audiences” .

— “But the fact that she resonated with many professionals in our community, I think, has a lot to do with Marsha Linen’s charisma, her ability to connect with both clinicians and scientific audiences” .