Living with someone who has aspergers

Coping With a Partner's Asperger's Syndrome - Autism Center

It takes a lot of work to make a marriage or other long-term relationship a success. And when one partner has Asperger’s syndrome, the relationship can be even more of a challenge. Given that Asperger’s makes emotional connections and social communication extremely difficult, it’s no wonder that a partnership between a person with Asperger’s syndrome and someone without it can be filled with stress, misunderstandings, and frustration.

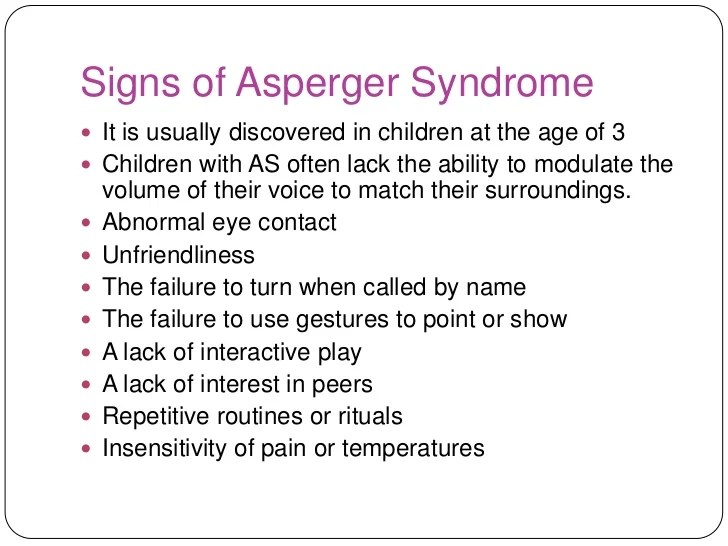

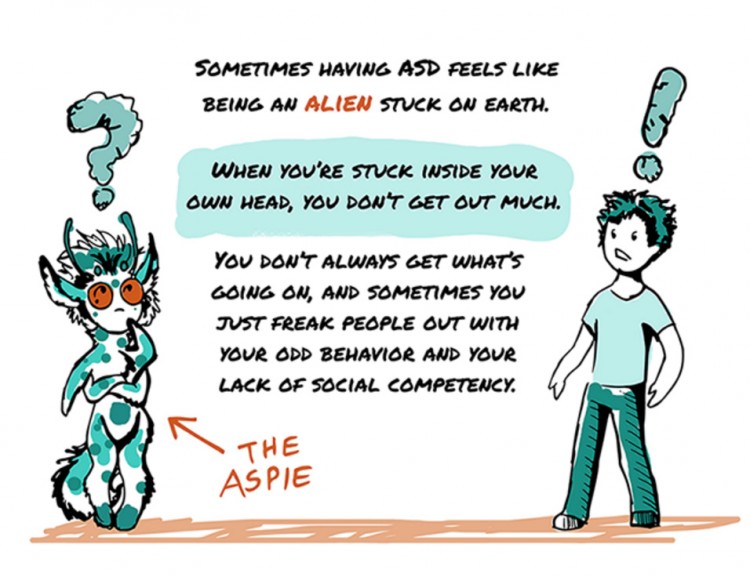

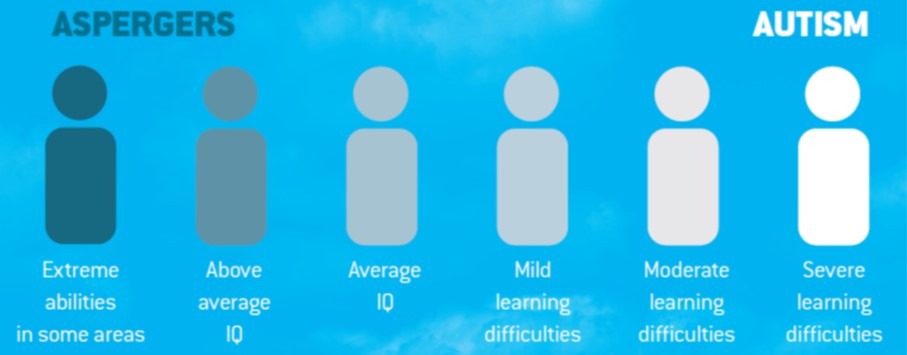

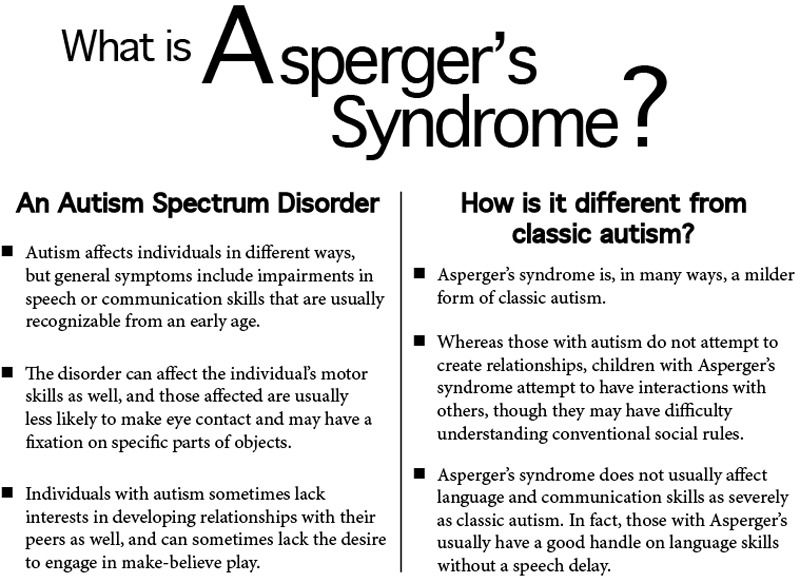

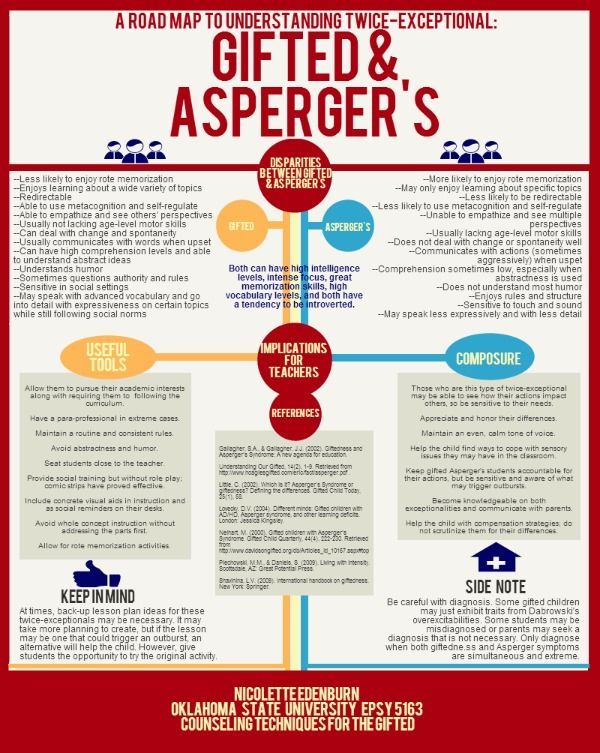

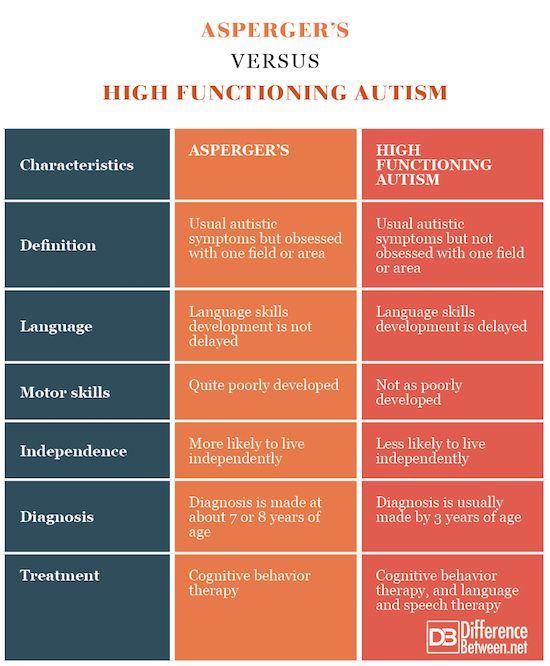

To understand how Asperger’s can create such angst in a relationship, it’s important to know how people with it are affected. Asperger’s syndrome is a developmental disorder that is part of the autism spectrum. It is considered a high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Recent statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that one in 68 American children born today has some sort of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Another study published on CDC also shows that ASD is over four times more likely to be diagnosed in males than females.

People with classic autism can have severe impairments in language development and the ability to relate to others. Those with Asperger’s syndrome are affected to a lesser degree, but often have difficulties connecting on a social and emotional level. They have a hard time reading verbal and nonverbal cues like body language and facial expressions, and may have trouble making eye contact. They sometimes don’t pick up on “how” something was said, only on “what” was said. People with Asperger’s may also lack empathy, the ability to understand the feelings of others. They may unwittingly say or do inappropriate things that offend or hurt others’ feelings.

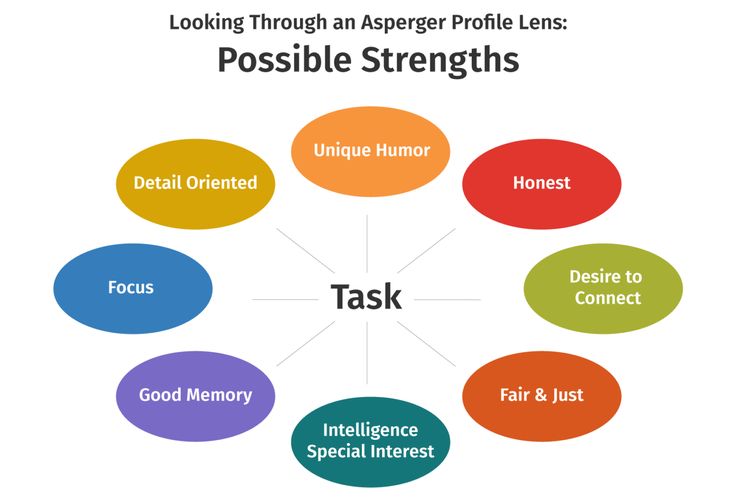

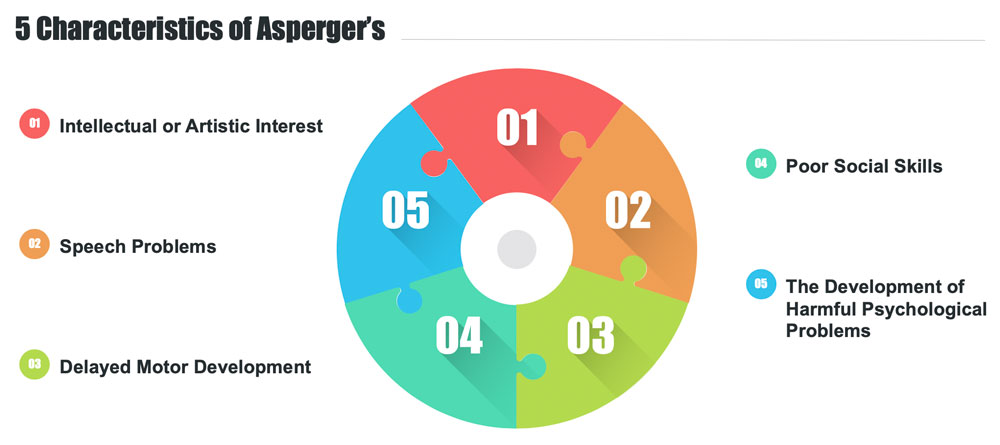

Though each person with Asperger’s syndrome is unique, some common characteristics include:

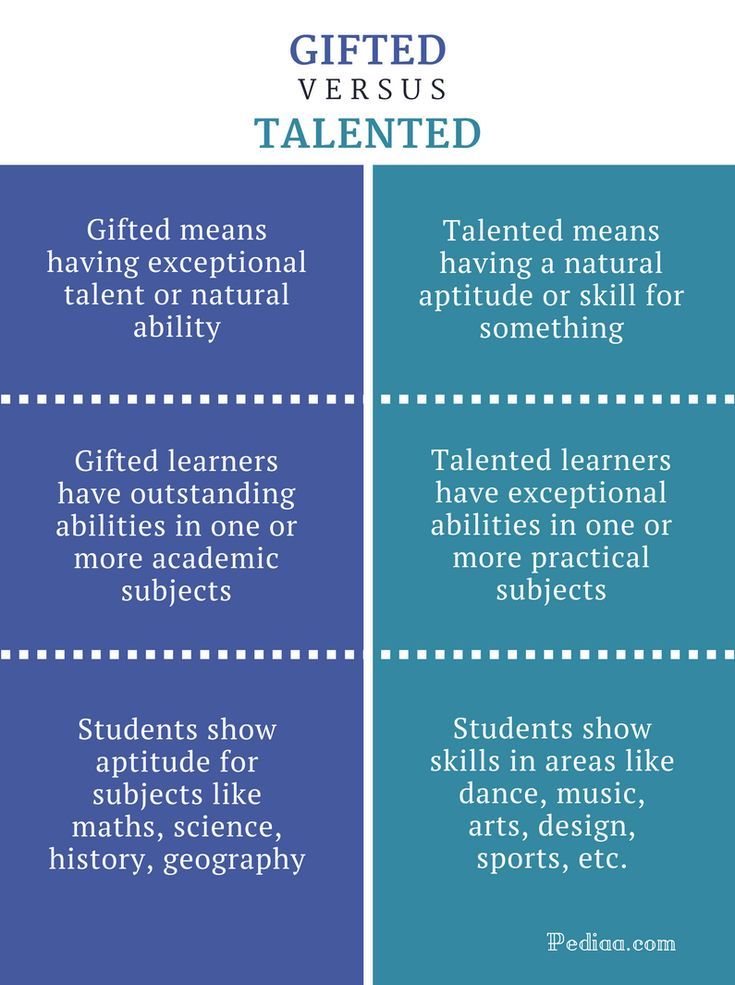

- Above-average intelligence

- A keen interest in or obsession with a particular subject — an unusual interest in trains, for example — and being a master on that subject

- Having strict routines or rituals and having a hard time with change or transitions

- Sensory issues

Because of these eccentricities and their lack of social skills, people with Asperger’s may make few friends and are often considered loners.

Lack of empathy is one of the most challenging problems for someone with Asperger's who is in a relationship, says Kathy Marshack, PhD, a psychologist in Vancouver, Wash., who works with couples affected by Asperger’s syndrome and the author of Life With a Partner or Spouse With Asperger Syndrome: Going Over the Edge? The non-Asperger’s member of the relationship gets angry and hurt by the partner’s lack of emotion and understanding, often saying things like, “You just don’t get it!” Because the person with Asperger’s does indeed “not get it,” he or she pulls away and gets angry and defensive, Marshack explains. Over time, the emotional disconnect can chip away at the relationship. The non-Asperger’s partner often feels unloved, worn down, and depressed, she says.

Asperger’s/non-Asperger’s couples also face a number of other challenges, including:

- Sexual problems. Marshack says sex is one of the first things to fall apart in these relationships.

Half of the problem arises from sensory issues, but the other half is the lack of empathy. People with Asperger’s can’t gauge what their partner enjoys (or does not enjoy) by reading their body language. Says Marshack, “Who wants to constantly talk their way through sex, saying things like, ‘Please put your hand here’?”

Half of the problem arises from sensory issues, but the other half is the lack of empathy. People with Asperger’s can’t gauge what their partner enjoys (or does not enjoy) by reading their body language. Says Marshack, “Who wants to constantly talk their way through sex, saying things like, ‘Please put your hand here’?” - Strain during social settings. Because a person with Asperger’s syndrome has difficulty with social skills, Marshack says, the non-Asperger’s partner is always ready to swoop in and “save” his or her partner from embarrassment. Socializing can become simply too much work, and the couple stops doing it or the partners start living separate lives. Sometimes the Asperger’s partner abuses alcohol to lower inhibitions and feel more “normal” in social situations.

- Parenting problems. “When children enter the picture, it’s often the demise of the relationship,” says Marshack. The non-Asperger’s partner is often devastated by the lack of empathy shown to the child: The Asperger’s parent may ignore the child, make caustic comments, and not recognize when the child needs comforting.

Sometimes the Asperger’s parent is overly strict or way too lenient, leaving much of the real parenting up to the non-Asperger’s partner. This sets up a parenting battlefield, even though both parents love the child.

Sometimes the Asperger’s parent is overly strict or way too lenient, leaving much of the real parenting up to the non-Asperger’s partner. This sets up a parenting battlefield, even though both parents love the child.

Tim Bennett, a painter living in Great Britain, is in a long-term relationship with Tray, a woman with Asperger’s syndrome. Tray refuses to move out of her small one-bedroom apartment or share it with Tim even though the couple have a son together. Francis, age 6, also has Asperger’s and related behavioral issues. Bennett says that since he and Tray have vastly different parenting styles, they find it better to parent Francis separately to avoid conflict. Tray has a particularly hard time dealing with Francis’s behavior and runs the risk of having a public meltdown if the child is difficult. On the upside, “she can enter into play with him in ways that I cannot, imaginatively creating worlds together," Bennett says. "So we complement each other in many ways as parents. "

"

Jurintha Fallon also knows the difficulties of living with an Asperger’s partner. The stay-at-home mom of two teen boys in Connecticut says life with her husband, Rob, a successful computer engineer with Asperger’s syndrome, is “like riding a roller coaster 24/7 without being strapped in.”

Jurintha and Rob have been married for 20 years, but he was formally diagnosed just two years ago. She had long suspected something was different about Rob. Jurintha’s lightbulb moment came 11 years ago when her younger son was diagnosed with Asperger’s. “Our son’s behaviors and diagnosis are what quickly led me to believe my husband also had Asperger’s," she says.

Jurintha describes Rob as functioning as an adult on an intellectual level but as a child on an emotional one. The couple has experienced many relationship pitfalls because of Asperger’s, but perhaps the most significant issue has been Rob’s lack of empathy, she says. This issue came to a head a few years ago when their older son had a life-threatening bicycle accident while staying with grandparents in Maine. Jurintha and Rob were at a business event in Boston, but Rob didn’t want to leave to be at his son’s bedside. Rob believed his parents had the situation under control so it was unnecessary to make 2.5-hour drive.

This issue came to a head a few years ago when their older son had a life-threatening bicycle accident while staying with grandparents in Maine. Jurintha and Rob were at a business event in Boston, but Rob didn’t want to leave to be at his son’s bedside. Rob believed his parents had the situation under control so it was unnecessary to make 2.5-hour drive.

Jurintha finally convinced Rob that they had to go. “The first question my son asked was ‘Did you leave work right away to come up?’" Jurintha says. "I had to lie. Rob didn’t see how upset my younger son was and how exhausted his parents were either. He started working the next day."

After that incident, Jurintha demanded that Rob see a psychologist to get an Asperger’s assessment. After the diagnosis, Rob started therapy, and he has made big strides in understanding how his Asperger’s affects the marriage. “I am very proud of him,” Jurintha says.

4 Ways to Cope When Your Partner Has Asperger’s SyndromeFor the most part, people with Asperger’s want to be loving partners and parents, but they need help learning how to do it, says Jurintha. Here’s how to make life a little easier for everyone:

Here’s how to make life a little easier for everyone:

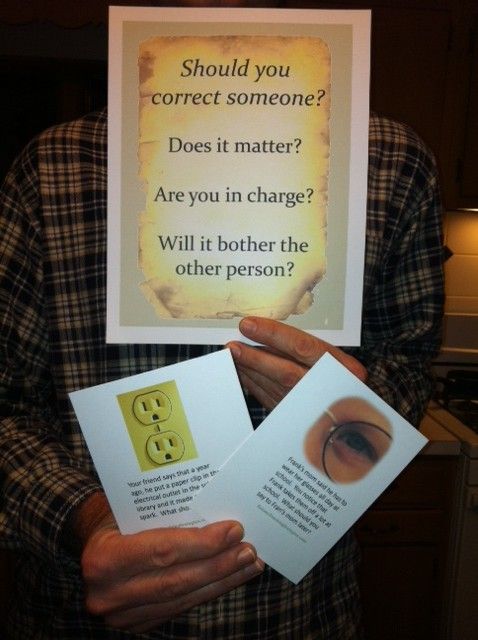

- Communicate your needs directly. Do this either verbally or in writing and without emotion. Don’t hint — they just won’t get it, Jurintha says.

- Set clear rules about parenting. Marshack says that the Asperger’s partner needs to agree to stop talking to or disciplining the child in certain situations if the non-Asperger’s parent says to. The Asperger’s partner might be missing something the other parent can pick up on. Discuss the situation as a couple and work out a solution.

- Consider therapy. Marshack suggests starting with individual therapy for both partners and then doing couples therapy. Realize you can’t “fix” your partner, but education is the first step. “Read everything you can about Asperger’s, and become an expert about the dynamics of your own relationship,” Marshack says. Jurintha adds that therapy can help you learn to cope and do more than just survive the relationship.

- Seek support. Consider joining a support group. One online option is Aspergers and Other Half, a support group for women whose partners have Asperger’s. Asperger Syndrome: Partners & Family of Adults With ASD is another community for men and women who love an adult with Asperger's.

Both Jurintha and Tim stress how much they love their partners and are committed to their relationships. “In the end, we love each other, we both know this, and are learning to cope with each other," Jurintha says. A little humor doesn’t hurt either. “We have a funny thing we say to each other: ‘You drive me crazy!’ ‘Ditto!’ It’s just as challenging for him to cope with me as it is to cope with him."

What Factors Raise Your Risk for Asperger’s Syndrome?

As with most autism spectrum disorders, researchers aren’t able to pinpoint one specific cause of Asperger’s. But, they do have some theories.

By Julie Lynn Marks

What Is Asperger’s Syndrome? Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention

By Julie Lynn MarksAre There Tests for Asperger’s Syndrome?

By Julie Lynn Marks7 Famous People You Didn’t Know Had Asperger’s Syndrome

Did you know that Courtney Love and Dan Akroyd have Asperger’s? Here are 10 influential people who will change the way you think about the syndrome.

By Nicol Natale

Resources to Help Families Cope With Asperger's Syndrome

By Julie Lynn MarksAsperger’s Syndrome: What Are the Signs and Symptoms of the Disorder?

By Julie Lynn MarksWhat Factors Raise Your Risk for Asperger’s Syndrome?

As with most autism spectrum disorders, researchers aren’t able to pinpoint one specific cause of Asperger’s. But, they do have some theories.

By Julie Lynn Marks

See AllLiving With Someone Who Has Autism Spectrum Disorder

Perhaps you are a spouse wondering if your partner has Asperger’s, a friend, acquaintance or colleague of someone you suspect has it, or perhaps you wonder if you might have it yourself. How would you know?

How would you know?

In this chapter, I will explain how the process of diagnosing someone for Asperger’s is usually carried out, both in general terms and the specific way I undertake a diagnosis. I will describe the types of information that is sought in an assessment for Asperger’s and how that information is collected. I will answer the question of how accurate a diagnosis is, the confidence one can have in a diagnosis of Asperger’s and I will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of having a diagnosis.

The Diagnostic Process

Diagnosing Asperger’s is a fairly easy process in principle. But in practice it is complicated and necessities a professional who understands thoroughly not just the characteristics of Asperger’s but how they are played out in real life. Reading about Asperger’s in a book or articles generally makes it seem that Asperger’s is a clear cut, well defined and easily identifiable condition. In truth, people with Asperger’s behave in many different ways and not always exactly how it is defined.

For example, someone with Asperger’s can be quite intelligent and have mastery over numerous facts, yet have much less comprehension emotions and how they are expressed. The person may be able to identify basic emotions, such as intense anger, sadness or happiness yet lack an understanding of more subtle expressions of emotions such as confusion, jealousy or worry.

How is it possible to tell for sure if someone doesn’t understand subtle emotions? They often don’t come up while sitting in an office speaking to a professional and because the person is not aware of their presence it’s unlikely that person would volunteer how hard it is to understand them. Relying on a spouse’s or friend’s report about how someone recognizes emotions is not always advisable since those reports are filtered through the spouse or friends’ own biases and their own ways of understanding emotions.

The only way to tell is to be around someone long enough to experience what they are like, to see how they respond in situations that test the features of Asperger’s and ask the right kinds of questions to clarify whether they have those features. There is test yet developed that can be used to make a diagnosis of Asperger’s, no instrument that measures Asperger’s nor any procedure that can objectively sort out those with Asperger’s from those without it. Brain scans, blood tests, X-rays and other physical examinations cannot tell whether anyone has Asperger’s.

There is test yet developed that can be used to make a diagnosis of Asperger’s, no instrument that measures Asperger’s nor any procedure that can objectively sort out those with Asperger’s from those without it. Brain scans, blood tests, X-rays and other physical examinations cannot tell whether anyone has Asperger’s.

The bottom line is that Asperger’s is a descriptive diagnosis. A person is diagnosed based on the signs and symptoms he or she has rather than the results of a specific laboratory or other type of test. Those signs and symptoms are often subtle and it takes someone with considerable experience to tell whether they are present and, if so, whether there is enough of a case to say confidently that the person has Asperger’s. It is all a matter of confidence, that is, with very few exceptions no one can say that someone else has Asperger’s only that one has a certain degree of certainty that a person does have Asperger’s.

Diagnosing Asperger’s

With this in mind, what is the actual process of finding out whether someone has Asperger’s?

Other professionals may take different steps but I have a clear-cut procedure that I go through when asked to assess Asperger’s. I first determine whether it makes reasonable sense to undertake an assessment of Asperger’s. The assessment process itself is time consuming and it can be costly. Why go through with it if there is no good reason to assume there might be some likelihood of finding the behaviors and signs of Asperger’s? After all, you wouldn’t go to the trouble of evaluating whether you have a broken foot if, in the first place, there is absolutely nothing wrong with your foot.

I first determine whether it makes reasonable sense to undertake an assessment of Asperger’s. The assessment process itself is time consuming and it can be costly. Why go through with it if there is no good reason to assume there might be some likelihood of finding the behaviors and signs of Asperger’s? After all, you wouldn’t go to the trouble of evaluating whether you have a broken foot if, in the first place, there is absolutely nothing wrong with your foot.

Screening Questionnaires:

Currently there are nine screening questionnaires that are used to identify adults who may have Asperger’s. Most require the respondent to indicate whether he or she agrees with a statement related to Asperger’s.

Examples of actual statements are:

- I find it difficult to imagine what it would be like to be someone else.

- The phrase, “He wears his heart on his sleeve,” does not make sense to me.

- I miss my best friends or family when we are apart for a long time.

- It is difficult for me to understand how other people are feeling when we are talking.

- I feel very comfortable with dating or being in social situations with others.

- I find it easy to “read between the lines” when someone is talking to me.

Completing one or more of these questionnaires can identify abilities, inclinations and behavior that could be indicative of Asperger’s syndrome. The results might suggest that it makes sense to investigate further if enough criteria are present to indicate a diagnosis of Asperger’s.

The questionnaires and scales for adults are as follows, in alphabetical order:

- Adult Asperger Assessment (AAA) (include link, for each test below)

- Aspie Quiz (AQ)

- Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ)

- Empathy Quotient for Adults (EQA)

- Friendship and Relationship Quotient (FQ)

- Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale (RAADS)

- Social Stories Questionnaire (SSQ)

- Systematizing Quotient (SQ)

- The Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET)

These questionnaires indicate whether a person has characteristics that match those of people with Asperger’s but that, in and of itself, doesn’t prove someone has or doesn’t have Asperger’s. The person filling out the questionnaire may be responding to the questions with the intention, conscious or not, of demonstrating that they don’t have, or for that matter they do have, Asperger’s. Often people answer these questions based on what they know about Asperger’s, they’ve read or been told about it, or what they imagine it is, and what they are indicating in their answers is not a accurate reflection of the characteristics they actually have.

The person filling out the questionnaire may be responding to the questions with the intention, conscious or not, of demonstrating that they don’t have, or for that matter they do have, Asperger’s. Often people answer these questions based on what they know about Asperger’s, they’ve read or been told about it, or what they imagine it is, and what they are indicating in their answers is not a accurate reflection of the characteristics they actually have.

Again, screening questionnaires are designed to identify potential cases of Asperger’s syndrome but they are not a substitute for a thorough diagnostic assessment.

To do that, an experienced professional needs investigate two things: the person’s medical, developmental, social, family and academic history; and how the person responds to a face-to-face assessment of social reasoning, communication of emotions, language abilities, focused interests, and non-verbal social interaction.

Personal History

Diagnoses are most valid and accurate when they are based on multiple sources of information. One highly important source are any documents, including reports, evaluations, notices, or assessments, that speak to the person’s social, emotional, language, and physical growth. An example is previous medical reports documenting signs of early language delays and/or peculiarities, coordination problems, behavioral difficulties or unusual physical problems. School reports might indicate past social and emotional difficulties, along with academic tendencies, that could be relevant to any indications of Asperger’s syndrome. Tutoring reports, evaluations of group activities, personal diaries, family recordings and other such records often provide valuable insights about the likelihood of Asperger’s.

One highly important source are any documents, including reports, evaluations, notices, or assessments, that speak to the person’s social, emotional, language, and physical growth. An example is previous medical reports documenting signs of early language delays and/or peculiarities, coordination problems, behavioral difficulties or unusual physical problems. School reports might indicate past social and emotional difficulties, along with academic tendencies, that could be relevant to any indications of Asperger’s syndrome. Tutoring reports, evaluations of group activities, personal diaries, family recordings and other such records often provide valuable insights about the likelihood of Asperger’s.

It is often the case that a person seeking an evaluation does not have any documentation, formal or informal, that is relevant to the assessment process. That is not an insurmountable problem. We work with what we have, and a diagnosis, either way, doesn’t depend upon any one piece of the assessment process. I have had many cases where I was able to conclude with confidence whether the person had Asperger’s without seeing one single piece of written evidence about that person’s past. It helps when that evidence is available but it is not critical.

I have had many cases where I was able to conclude with confidence whether the person had Asperger’s without seeing one single piece of written evidence about that person’s past. It helps when that evidence is available but it is not critical.

Clinical Interview

Sitting down and talking to someone makes the difference between an assessment of Asperger’s that has a high degree of confidence and one that is questionable. When I assess someone for Asperger’s I ask to meet face-to-face for three meetings.

The first meeting covers general facts about the person, particular those relating to his or her present life. I want to find out about the person’s significant relationships, whether they are friends, work colleagues, spouse or partner, children or anyone else with whom the person interacts regularly. I am interested in how the person gets along at work and his or her work performance, how the person manages daily living, what initiative the person takes in planning and achieving life goals, and how satisfied the person is with his or her life. These questions help me assess whether the person’s attitudes towards life, conduct in relationships, and general success in achieving life goals reveal any of the characteristics that typically are found in people with Asperger’s.

These questions help me assess whether the person’s attitudes towards life, conduct in relationships, and general success in achieving life goals reveal any of the characteristics that typically are found in people with Asperger’s.

The second meeting focuses on the person’s background, particularly information about the person’s early family life; previous school experiences; past friendships, employment and intimate relationships; childhood emotional development and functioning, and significant interests throughout the person’s life. Because Asperger’s is a condition that exists at or before birth, clues about the presence of Asperger’s are found in the history of the person’s childhood. Hence a thorough understanding of early social, emotional, family, academic and behavioral experiences are essential to the diagnostic process.

The third and final meeting is a time to clarify questions that were not completely answered in the previous meetings, gather additional information and raise additional questions that have emerged from the information collected so far. When everything has been addressed to the extent allowed in this timeframe, the final part of the clinical interview is the presentation of my findings.

When everything has been addressed to the extent allowed in this timeframe, the final part of the clinical interview is the presentation of my findings.

Presenting these findings is a multi-step process. First, I explain that certain characteristics are central to Asperger’s syndrome. If those characteristics are not present in the person then he or she doesn’t have Asperger’s and if they are present a diagnosis of Asperger’s is much more viable.

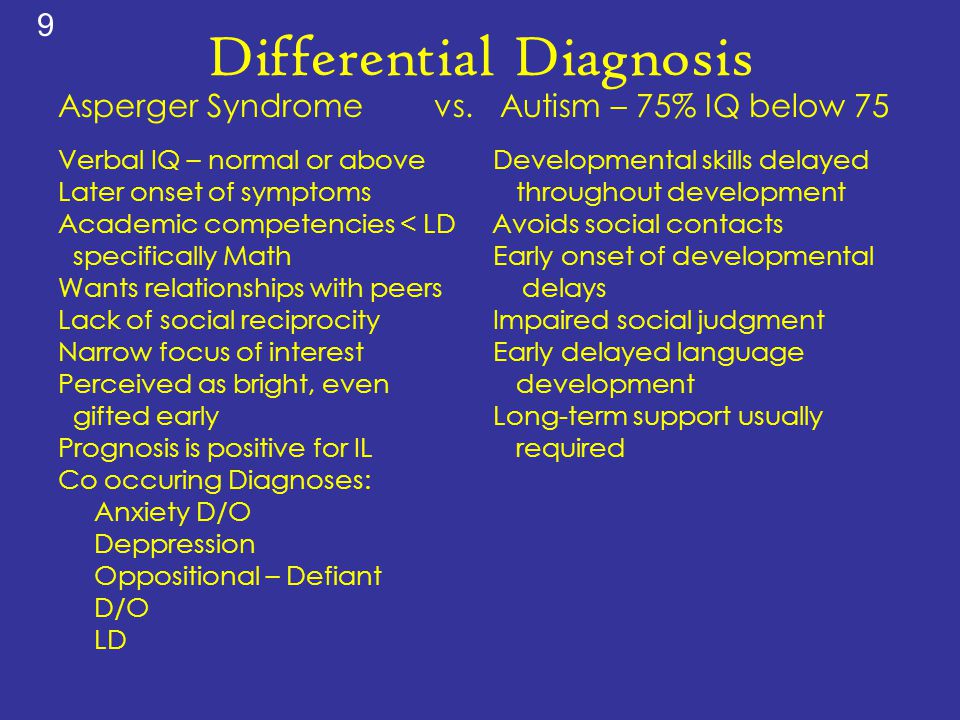

There are also characteristics that are related to Asperger’s but are also shared by other conditions. An example of this is difficulty noticing whether people are bored or not listening in conversations. Lots of people don’t pay much attention to whether people are listening to them, but that doesn’t mean they have Asperger’s. On the other hand, in combination with other signs of Asperger’s, not noticing how people respond in conversations, could be a significant confirmation of an Asperger’s diagnosis.

To diagnosis and adult with Asperger’s requires that the person have:

- Persistent difficulty in communicating with, and relating to, other people.

Their conversations have to be generally one-sided. There has to be reduced sharing of interests and a lack of emotional give-and-take. Superficial social contact, niceties, passing time with others are of little interest. Little or too much detail is included in conversation, and there is difficulty in recognizing when the listener is interested or bored.

Their conversations have to be generally one-sided. There has to be reduced sharing of interests and a lack of emotional give-and-take. Superficial social contact, niceties, passing time with others are of little interest. Little or too much detail is included in conversation, and there is difficulty in recognizing when the listener is interested or bored. - Poor nonverbal communication, which translates into poor eye contact, unusual body language, inappropriate gestures and facial expressions.

- Difficulty developing, maintaining and understanding relationships.

- Narrow, repetitive behaviors and interests. Examples of these are insisting on inflexible routines, eating the same foods daily, brushing teeth the same way, following the same route every day, repeatedly rejecting changes in one’s life style, being either very reactive or hardly reactive at all to changes in one’s environment like indifference to temperature changes, hypersensitivity to sounds, fascination with lights or movement.

- Signs of these characteristics as early as 12-24 months of age, although the difficulties with social communication and relationships typically become apparent later in childhood.

- Indications that these characteristics are causing significant problems in relationships, work or other important areas of the person’s life.

- Clear evidence that these characteristics are not caused by low intelligence or broad, across-the-board delays in overall development.

What happens if someone has some of these difficulties but not all? Do they qualify for a diagnosis of Asperger’s, or not?

The answer lies in how much these characteristics affect the person’s social, occupational or other important areas of functioning. If, for example, the core characteristics of Asperger’s lead a person to speak in few sentences, interact with people only around very narrow, special interests and communicate in odd, nonverbal ways, we can say that these are indicators that a diagnosis of Asperger’s is correct.

If, on the other hand, the person engages in limited back-and-forth communication, attempts to make friends in odd and typically unsuccessful ways, and is not especially interested in reaching out to others, a diagnosis of Asperger’s could be considered but not assured.

A diagnosis is most assured when the signs of Asperger’s are present in the person all the time, they have an obvious effect on the person’s ability to be successful in life, and don’t vary much. Additionally, when the information used to make a diagnosis comes from multiple sources, like family history, an expert’s observations, school, medical and other reports, questionnaires and standardized test instruments the diagnosis is likely to be more accurate and reliable.

Advantages and Disadvantages of an Asperger’s Diagnosis

The advantages of having an accurate, reliable diagnosis of Asperger’s are many. It can eliminate the worry that a person is severely mentally ill. It can support the idea that the person has genuine difficulties arising from a real, legitimate condition. Other people, once they are aware that the person has Asperger’s are often able to be more accepting and supportive. A new, and more accurate, understanding of the person can lead to appreciation and respect for what the person is coping with.

Other people, once they are aware that the person has Asperger’s are often able to be more accepting and supportive. A new, and more accurate, understanding of the person can lead to appreciation and respect for what the person is coping with.

Knowing someone has Asperger’s opens up avenues to resources for help as well as access to programs to improve social inclusion and emotional management. Acceptance by friends and family members is more likely. An acceptable explanation to other people about the person’s behavior is now available leading to the possibility of reconciliation with people who have had problems with the person’s behavior.

In the workplace and in educational settings, a diagnosis of Asperger’s can provide access to helpful resources and support that might otherwise not have been available. Employers are more likely to understand the ability and needs of an employee should that employee make the diagnosis known. Accommodations can be requested and a rationale can be provided based on a known diagnosis.

Having the diagnosis is a relief for many people. It provides a means of understanding why someone feels and thinks differently than others. It can be exciting to consider how one’s life can change for the better knowing what one is dealing with. There can be a new sense of personal validation and optimism, of not being defective, weird or crazy. With the knowledge that one has Asperger’s, joining a support group, locally or through the Internet can provide a sense of belonging to a distinct and valued culture and enable the person to consult members of the group for advice and support.

Acceptance of the diagnosis can be an important stage in the development of successful adult intimate relationships. It also enables therapists, counselors and other professionals to provide the correct treatment options should the person seek assistance.

Liane Holliday Willey is an educator, author and speaker. She was diagnosis with Asperger’s syndrome in 1999. In her 2001 book, “Asperger’s Syndrome in the Family: Redefining Normal in the Family, she wrote the following self-affirmation pledge for those with Asperger’s syndrome.

– I am not defective. I am different.– I will not sacrifice myself-worth for peer acceptance.– I am a good and interesting person.– I will take pride in myself.– I am capable of getting along with society.– I will ask for help when I need it.– I am a person who is worthy of others’ respect and acceptance.– I will find a career interest that is well suited to my abilities and interests.– I will be patient with those who need time to understand me.– I am never going to give up on myself.– I will accept myself for who I am.(Willey 2001. p. 164)

Are there disadvantages to a diagnosis of Asperger’s? Yes, but the list is shorter than the list of advantages.

Some people receive a diagnosis of Asperger’s with discouragement and disapproval, believing they necessarily will be severely limited in how they can lead their lives. No longer will they be able to hope to have a satisfying, intimate relationship. Instead, their future will be filled with loneliness and alienation from others with no expectation of improvement. This, of course, is an unrealistic and exaggerated depiction of what living with Asperger’s is like.

This, of course, is an unrealistic and exaggerated depiction of what living with Asperger’s is like.

Of course, it is possible that people in someone’s life will react to the diagnosis of Asperger’s by alienating themselves from that person. Stigmatizing and disapproval, based on the knowledge that a person has Asperger’s is still prevalent in our society. Damage to one’s self-esteem as a result of disapproval, ridicule, discrimination and rejection is possible when knowledge of an Asperger’s diagnosis is disseminated.

Job discrimination is a realistic possibility in the event that an applicant reveals an Asperger’s diagnosis. While it is not legally acceptable to do so, we know that silent discrimination happens, hiring decisions are not always made public and competition can leave someone with a different profile out of the picture.

Similarly, having a diagnosis of Asperger’s may lead others to assume the person will never be able to be as successful in life as neurotypical people. It is commonly assumed that Asperger’s makes someone too difficult to be around, unable to get along with people, too narrowly focused on their own interests, and too stubborn, self-absorbed and lacking in empathy to be a contributing member of society, a view that is narrow in its own right and sadly mistaken in many cases. Nevertheless, attitudes like this can arise when a diagnosis of Asperger’s is made public.

It is commonly assumed that Asperger’s makes someone too difficult to be around, unable to get along with people, too narrowly focused on their own interests, and too stubborn, self-absorbed and lacking in empathy to be a contributing member of society, a view that is narrow in its own right and sadly mistaken in many cases. Nevertheless, attitudes like this can arise when a diagnosis of Asperger’s is made public.

Dual Diagnoses

Often, people tell me when we meet to discuss an Asperger’s evaluation that the symptoms of Asperger’s they have seen, usually online, match what they notice in themselves. Just as often other people, in researching Asperger’s symptoms, believe the person coming to see me has those very characteristics and therefore must have Asperger’s.

The problem with this is that several other conditions share many of the same symptoms with Asperger’s. Just knowing how the person behaves, thinks and feels does not, in and of itself, tell you whether he or she has Asperger’s. It very well might be that some other condition is the real problem or, more likely, two or more conditions are overlapping. In this case, it is more accurate to say the person has co-existing conditions rather than it being a straightforward matter of Asperger’s.

It very well might be that some other condition is the real problem or, more likely, two or more conditions are overlapping. In this case, it is more accurate to say the person has co-existing conditions rather than it being a straightforward matter of Asperger’s.

Here is a description of the psychiatric conditions most frequently associated with Aspergers’:

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

People with ADHD typically have difficulty paying attention to what’s going on around them, they are easily distracted, they tend to do things without thinking about the results, they are often forgetful, have trouble finishing what they intended to do, are disorganized, jump from one activity to another, are restless and have poor social skills.

Many of these symptoms overlap with those of Asperger’s. Research has shown growing evidence for a connection between Asperger’s and ADHD. Genetic studies suggest the two disorders share genetic risk factors, and studies of the incidence and distribution of both conditions confirm that many people with Asperger’s have symptoms of ADHD and vice versa. Brain imaging and studies of the brain structure show similarities between the two disorders.

Brain imaging and studies of the brain structure show similarities between the two disorders.

Having said that, there are important differences between the two. People with ADHD often try to do multiple activities at the same time. They get distracted easily and jump from one interest or activity to another. Focusing on one thing for a long time is hard for them. On the other hand, people with Asperger’s tend to focus on only one activity at a time, and they focus on that activity intensely with little regard for anything else going on around them. They are hyper-focused rather than unfocused.

There is a similar difference with respect to impulsivity. People with ADHD will do things without considering the outcome of their actions. They act immediately and have trouble waiting. They interrupt, blurt out comments and seem unable to restrain themselves.

People with Asperger’s think through their actions more carefully. They may interrupt and say things without regard for whatever else is going on but it is because they don’t understand how conversations are carried out rather than not being able to restrain themselves.

There is a big difference in how adults with ADHD use language compared to adults with Asperger’s. They do not tend to have specific weaknesses in their understanding and use of language. They readily understand when a statement such as, “it’s raining cats and dogs” is being used as a figure of speak and not as a literal statement. They also speak with a normal tone of voice and inflection.

In contrast, adults with Asperger’s tend not to understand non-literal language, slang or implied meanings. They may talk a lot and have more one-sided conversations as do adults with ADHD but they do so because lacking an understanding of how the person they are talking to is grasping what they are saying they are, in effect, talking to themselves.

Difficulty interpreting non-verbal communication and subtle aspects of how people relate to each other is characteristic of adults with Asperger’s. They confuse behaviors that may be appropriate in one setting from those that are appropriate in another, so that they often act in appropriate for the situation they are in. They find it hard to interpret the meanings of facial expressions and body posture, and they have particular difficulty understanding how people express their emotions.

They find it hard to interpret the meanings of facial expressions and body posture, and they have particular difficulty understanding how people express their emotions.

Adults with ADHD, on the other hand, understand social situations more accurately and they engage much easier in social situations even though they are easily distracted and often not observant of what’s going on around them. They can consider what other people are thinking much easier than adults with Asperger’s and they participate in the give-and-take of social interactions more readily.

Adults with ADHD tend to express their feelings directly and fairly clearly whereas adults with Asperger’s do not show a wide range of emotions. When they do communicate their feelings they are often out of synch with the situation that generated the feeling.

Adults with ADHD tend to process sensory input in a typical manner. They may have preferences for how they handle sensory input like music, touch, sounds, and visual sensations but generally the way they handle these situations is much like other adults.

In contrast, adults with Asperger’s have more specific preferences about the kind of sensations they like and dislike. They may be overly sensitive to one kind of sensation and avoid that persistently. Or they may prefer a certain type of sensation and, a certain type of music, for example, and seek it over and over. Overall, sounds, temperature differences, visual images and tastes more easily overwhelm adults with Asperger’s than adults with ADHD.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders

The core features of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are frequent and persistent thoughts, impulses or images that are experienced as unwelcomed and uninvited. It occurs to the person that these intrusive thoughts are the produce of his or her own mind but they can’t be stopped. Along with these thoughts are repetitive behaviors or mental acts that the person feels driven to perform in order to reduce stress or to prevent something bad from happening.

Some people spend hours washing themselves or cleaning their surroundings in order to reduce their fear that germs, dirt or chemicals will infect them. Others repeat behaviors or say names or phrases over and over hoping to guard against some unknown harm. To reduce the fear of harming oneself or others by, for example, forgetting to lock the door or turn off the gas stove, some people develop checking rituals. Still others silently pray or say phrases to reduce anxiety or prevent a dreaded future event while others will put objects in a certain order or arrange things perfects in order to reduce discomfort.

Others repeat behaviors or say names or phrases over and over hoping to guard against some unknown harm. To reduce the fear of harming oneself or others by, for example, forgetting to lock the door or turn off the gas stove, some people develop checking rituals. Still others silently pray or say phrases to reduce anxiety or prevent a dreaded future event while others will put objects in a certain order or arrange things perfects in order to reduce discomfort.

These behaviors, to repeat the same action over and over, are similar to the repetitive routines associated with Asperger’s. Individuals with both conditions engage in repetitive behaviors and resist the thought of changing them. The difference is that people with Asperger’s do not view these behaviors are unwelcomed. Indeed, they are usually enjoyed. In addition, whereas Asperger’s occurs early in the person’s life, OCD develops later in life. People with OCD have better social skills, empathy and social give and take than those with Asperger’s.

Social Anxiety Disorder

Social Anxiety Disorder, also called social phobia, occurs when a person has a fear of social situations that is excessive and unreasonable. The dominate fear associated with social situations is of being closely watched, judged and criticized by others. The person is afraid that he or she will make mistakes, look bad and be embarrassed or humiliated in front of others. This can reach a point where social situations are avoided completely.

Asperger’s and Social Anxiety Disorder share the common element of discomfort in social situations. Typically, along with this discomfort is lack of eye contact and difficulty communicating effectively.

The difference between these two conditions is that people with Social Anxiety Disorder lack self-confidence and expect rejection if and when they engage with others. Adults with Asperger’s, on the other hand, don’t necessarily lack self-confidence or are afraid of being rejected, they are simply not able to pick up on social cues. They don’t know how to act appropriately in social situations and thus tend to avoid them. In addition, Social Anxiety Disorder may be present in children but more commonly it develops in adolescence and adulthood whereas Asperger’s can be traced back to infancy.

They don’t know how to act appropriately in social situations and thus tend to avoid them. In addition, Social Anxiety Disorder may be present in children but more commonly it develops in adolescence and adulthood whereas Asperger’s can be traced back to infancy.

Schizoid Personality Disorder

People with Schizoid Personality Disorder (SPD) avoid social relationships and prefer to spend time alone. They have a very restricted range of emotions, especially when communicating with others and appear to lack a desire for intimacy. Their lives seem directionless and they appear to drift along in life. They have few friends, date infrequently if at all, and often have trouble in work settings where involvement with other people is necessary. They are the type of person that is others think of as the typical “loner.”

A noticeable characteristic of someone with SPD is their difficulty expressing anger, even when they are directly provoked. They tend to react passively to difficult circumstances, as if they are directionless and are drifting along in life. They are withdrawn because it makes life easier. They don’t gain a great deal of happiness from getting close to people. Often this gives others the impression that they lack emotion.

They are withdrawn because it makes life easier. They don’t gain a great deal of happiness from getting close to people. Often this gives others the impression that they lack emotion.

While this may strike some as similar to Asperger’s people with SPD can interact with others normally, if they want to, and can get along with people. They don’t have the strong preference for logical patterns in things and people, an inability to read facial expressions or “blindness” to what is going on in other people’s minds that characterizes Asperger’s.

In addition, people with SPD typically do not show these features until late adolescence or adulthood. The characteristics of Asperger’s must be noticeable in infancy or early childhood to receive the diagnosis of Asperger’s.

Most importantly, Asperger’s is a form of autism whereas people with SPD have a “neurotypical” brain and have developed into a personality of extreme introversion and emotional detachment.

Antisocial Personality Disorder

Individuals with Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD) disregard and violate the rights of others. They don’t conform to social norms with respect to lawful behavior, such as destroying property, stealing, harassing others, and cheating. They are frequently deceitful and manipulative so as to obtain money, sex, power of some other form of personal profit or pleasure. They tend to be irritable and aggressive and to get into physical fights or commit acts of physical assault (including spousal or child beating).

They don’t conform to social norms with respect to lawful behavior, such as destroying property, stealing, harassing others, and cheating. They are frequently deceitful and manipulative so as to obtain money, sex, power of some other form of personal profit or pleasure. They tend to be irritable and aggressive and to get into physical fights or commit acts of physical assault (including spousal or child beating).

They are consistently and extremely irresponsible financially, in their employment, and with regard to their own safety and the safety of others. They show little remorse for the consequence of their actions and tend to be indifferent to the hurt they have caused others. Instead, they blame victims of their aggression, irresponsibility and exploitation. They frequently lack empathy and tend to be callous, cynical and contemptuous of the feelings, rights and suffering of others.

They often have an inflated and arrogant view of themselves, and are described as excessively opinionated and cocky. They can appear charming and talk with superficial ease, attempting to impress others and appear experts on numerous topics.

They can appear charming and talk with superficial ease, attempting to impress others and appear experts on numerous topics.

There may appear to be some overlap between Asperger’s and APD, but the resemblance is superficial. Individuals with Asperger’s have trouble understanding how people operate but they do respect others, whereas people with APD have no regard for people. Individuals with Asperger’s are rarely deceitful, in fact, they are often considered excessively, even naively honest, quite unlike those with APD who are predictably deceitful and unremorseful, and unlike people with Asperger’s they are incapable of feeling genuine love. Asperger’s people do show and feel remorse whereas people with APD do not.

Bipolar Disorder

People with Bipolar Disorder (BD) have distinct ups and downs in their mood. At one point, they will have extreme energy, be unusually happy, energetic, talkative, feel wonderful about themselves and “on top of the world, have little need for sleep, be drawn to unimportant or irrelevant activities, and generally act unlike themselves. When they are down, they feel sad, empty, hopeless, worthless and inappropriately guilty. They have little interest in their usual activities, have little appetite, sleep more than usual, are slowed down, have difficulty concentrating and sometimes have suicidal thoughts.

When they are down, they feel sad, empty, hopeless, worthless and inappropriately guilty. They have little interest in their usual activities, have little appetite, sleep more than usual, are slowed down, have difficulty concentrating and sometimes have suicidal thoughts.

When someone with Bipolar Disorder is in a manic state or depressed they may not interact socially as they might if they were feeling normal, they might be withdrawn, lack much emotional response to situations in their life and lose interest in relationships but the changes in their emotional condition is much different than people with Asperger’s.

Someone with Asperger’s is socially awkward, cannot read or use body language or facial expressions well, have difficulty making eye contact, cannot understand sarcasm and jokes, tend to take things literally, may display socially inappropriate behavior without realizing it, have obsessive interests and may have problems with sensory issues.

While they may feel down at times or at other times be unusually happy, their concerns have much less to do with emotional ups and downs.

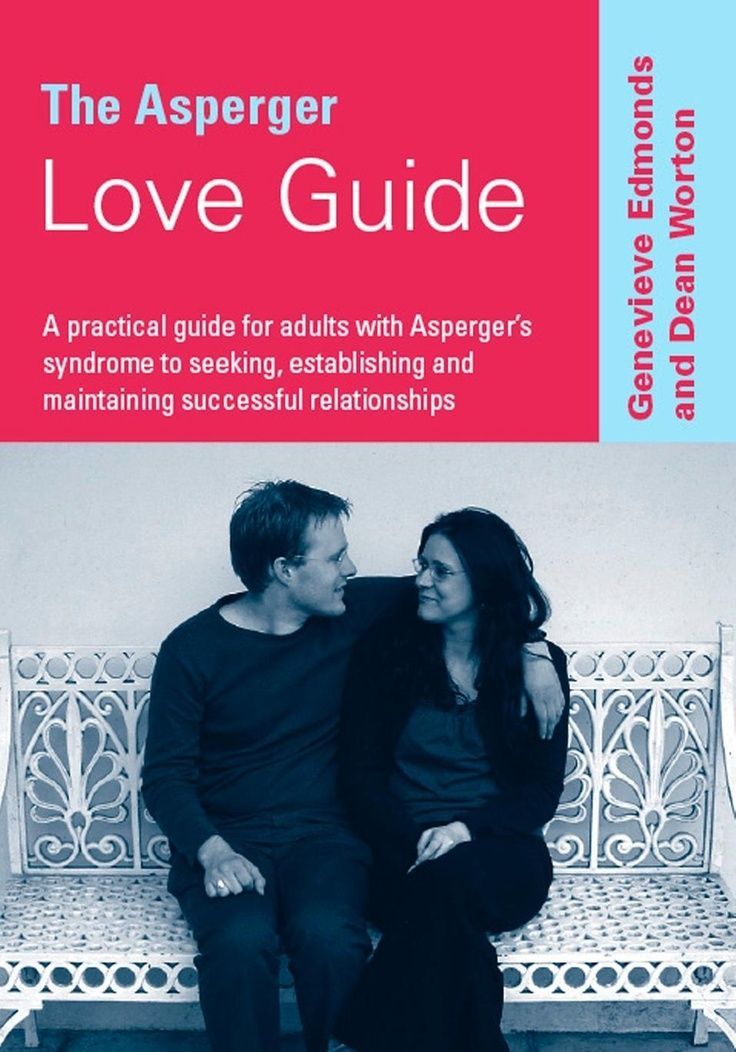

How can romantic relationships develop in young people with Asperger's syndrome and high-functioning autism?

04/19/14

Clinical psychologist, specializing in Asperger syndrome, about the features of romantic and intimate relationships in adults with RAS

Author: Tony Etwood

Translation: Tamara Solomatina

9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000.S. Autism Network

While young people with classic autism usually suffice with a solitary “hermit” lifestyle, people with Asperger's syndrome and high-functioning autism often do not. Clinical studies have shown that most of these adolescents and young adults are interested in romantic relationships. However, very little research addresses this aspect of autism spectrum disorders or strategies for successfully developing these relationships.

We know that young people with Asperger's have significant difficulty developing relationships with peers and understanding what the other person may be thinking or feeling. Ordinary children learn this naturally and practice the skills to develop relationships with family members and friends long before they use these abilities to successfully develop romantic relationships. Young people diagnosed with Asperger's and high-functioning autism have limited communication skills and may find it difficult to express emotions, especially affection. They may also have very high sensitivity to certain sensory experiences. All of these diagnostic characteristics affect relationship-forming skills as the child grows and will ultimately reduce the adult's chances of a successful long-term relationship.

Ordinary children learn this naturally and practice the skills to develop relationships with family members and friends long before they use these abilities to successfully develop romantic relationships. Young people diagnosed with Asperger's and high-functioning autism have limited communication skills and may find it difficult to express emotions, especially affection. They may also have very high sensitivity to certain sensory experiences. All of these diagnostic characteristics affect relationship-forming skills as the child grows and will ultimately reduce the adult's chances of a successful long-term relationship.

Love and affection

People with autism spectrum disorders have difficulty understanding and expressing emotions, and the most difficult emotion for such people is love. Ordinary children and adults often express their affection with pleasure, know how to express it to exchange mutual feelings of affection and love, and know how to support someone through the expression of affection. A child or adult with autism may not need the same depth and frequency of expressions of love through actions, or may not realize that the situation requires them to display their affection in a way that would please the other person. He or she may be annoyed by how "obsessed" other people are with expressing love for each other.

A child or adult with autism may not need the same depth and frequency of expressions of love through actions, or may not realize that the situation requires them to display their affection in a way that would please the other person. He or she may be annoyed by how "obsessed" other people are with expressing love for each other.

Some autistics may be obviously immature in their expressions of affection and sometimes perceive them as a negative experience. For example, a hug may feel uncomfortable and limit movement. A person may become embarrassed or overwhelmed when expected to express and accept fairly moderate expressions of love. I recently developed a cognitive behavioral therapy program for children and adolescents with Asperger's Syndrome that teaches them about the emotion of love and how to express that you love or feel sympathy for someone. The program will soon be evaluated in a study conducted by the University of Queensland in Australia.

Special interests

One of the diagnostic characteristics of Asperger's syndrome is the development of a special interest that is unusual in its object and significance. For adolescents and young adults, the target is sometimes a person, which can be interpreted as a typical teenage crush, but the degree of interest and associated behavior often lead to accusations of stalking and harassment. The propensity to develop a special interest can also influence the emergence of relationship knowledge in other ways. Special interests help people with Asperger's in many ways, including acquiring the knowledge to understand the annoying aspects of their life experiences. Adolescents with Asperger's Syndrome often seek to understand and experience in terms of communication and relationships, including romantic and sexual ones, the same as their peers, but they may have problems with sources of information about relationships and sexuality.

For adolescents and young adults, the target is sometimes a person, which can be interpreted as a typical teenage crush, but the degree of interest and associated behavior often lead to accusations of stalking and harassment. The propensity to develop a special interest can also influence the emergence of relationship knowledge in other ways. Special interests help people with Asperger's in many ways, including acquiring the knowledge to understand the annoying aspects of their life experiences. Adolescents with Asperger's Syndrome often seek to understand and experience in terms of communication and relationships, including romantic and sexual ones, the same as their peers, but they may have problems with sources of information about relationships and sexuality.

A teenager with Asperger's syndrome has few or no friends with whom to discuss topics such as romantic or sexual feelings and sexual behavior. Unfortunately, the only source of information for teens with Asperger's can be either porn movies for boys or soap operas for girls. A person with Asperger's Syndrome may decide that the actions shown in pornographic material can serve as a "script" of what to say or do on a date, but this misunderstanding can lead to allegations of harassment. Such allegations are more often related to inappropriate behavior than to violent or aggressive acts of a sexual nature. Girls with Asperger's Syndrome may use movies and TV shows as a source of knowledge about relationships and fail to recognize that TV shows do not accurately reflect the beginning and development of relationships in real life.

A person with Asperger's Syndrome may decide that the actions shown in pornographic material can serve as a "script" of what to say or do on a date, but this misunderstanding can lead to allegations of harassment. Such allegations are more often related to inappropriate behavior than to violent or aggressive acts of a sexual nature. Girls with Asperger's Syndrome may use movies and TV shows as a source of knowledge about relationships and fail to recognize that TV shows do not accurately reflect the beginning and development of relationships in real life.

Clinical studies show that unpopular girls with Asperger's syndrome, who are not accepted into any company, after the physical changes that occurred during puberty, are flattered by the attention from boys. Because of her naivety, the girl may not realize that their interest is sexual in nature, and not at all a desire to simply communicate with her and spend time in her company. She may not have female friends to take her on a first date or give her advice on social and sexual rules. Her parents may have strong concerns about her vulnerability to negative sexual experiences and possible date rape.

Her parents may have strong concerns about her vulnerability to negative sexual experiences and possible date rape.

Long-term relationship

There is a transition from acquaintance to partnership in the relationship. Individuals with Asperger's may find it difficult to cope with each step of this transition. To move from friend to partner status, a teenager or young person with Asperger's needs to understand the art of flirting in order to accurately read the signals of mutual sympathy and not get lost during dates. People with Asperger's do not understand this intuitively. These teens and young adults often ask me, “How can I find a boyfriend/girlfriend?” And this question is not easy to answer. One of the difficulties can be the correct interpretation of someone's intentions. A simple expression of kindness or sympathy can be taken much more seriously than intended. I have had to explain to men with Asperger's that the smile and attention from female flight attendants are just courtesies, not a desire to start a relationship.

Despite the relationship problems that most people with Asperger's have, some can develop relationships and form romantic and intimate relationships, even marriage. To achieve this level of relationship, partners need to initially notice the attractive qualities of each other. What is so attractive about a young person with Asperger's Syndrome?

Attractive qualities of people with Asperger's syndrome

Men with Asperger's syndrome may have a wide range of qualities that are attractive to a future partner. When I counsel couples in which one or both partners have characteristics or a diagnosis of Asperger's Syndrome, I often ask the neurotypical partner, "What qualities did your partner draw you to when you first met?" Many women describe that a partner with Asperger's syndrome initially impressed them as kind, considerate, but socially or emotionally immature. The term "silent handsome stranger" is often used to describe anyone who seems relatively quiet and likeable. Appearance and attention can become very important, especially if a woman has doubts about her own self-esteem and physical attractiveness. Lack of social and conversational skills lead to the formation of the image of the "mysterious stranger", whose naivety and immaturity the partner can compensate for by becoming an expert in empathy, socialization and communication.

Appearance and attention can become very important, especially if a woman has doubts about her own self-esteem and physical attractiveness. Lack of social and conversational skills lead to the formation of the image of the "mysterious stranger", whose naivety and immaturity the partner can compensate for by becoming an expert in empathy, socialization and communication.

I have noticed that the partners of many men and sometimes women with Asperger's are on the other end of the social and empathic spectrum. On an intuitive level, they are experts in the "model of the mental" (understanding someone else's consciousness), that is, they understand and sympathize with the experiences of other people. They have the gift of seeing the world as it appears to people with Asperger's to a much greater extent than people with average empathy. Being understanding and sympathetic, they help their partner cope with difficulties in social situations. Undoubtedly, adults with Asperger's Syndrome need these traits and want to see them in a potential partner. He or she will actively seek out someone with intuitive social skills, someone who will explain social situations to them, educate them, and care for them. However, while a socially gifted and empathetic partner may be able to understand the experiences of a person with Asperger's Syndrome, that person will have significant difficulty understanding their neurotypical partner.

He or she will actively seek out someone with intuitive social skills, someone who will explain social situations to them, educate them, and care for them. However, while a socially gifted and empathetic partner may be able to understand the experiences of a person with Asperger's Syndrome, that person will have significant difficulty understanding their neurotypical partner.

Intellectual abilities, one's own career, and increased attention to one's partner during courtship can make a person with Asperger's syndrome more attractive. Sometimes, however, this attentiveness can be perceived by others as excessive, and words and actions will seem as if they were memorized from Hollywood romantic films. A person can be admired for his straightforwardness, even if his comments hurt other people, because of his strong desire for social justice and clear moral principles. The fact that he may not be "macho" at all or not eager to spend time with other men at sports matches can also be very attractive in the eyes of some women. And the fact that a person with Asperger's syndrome entered into a relationship quite late can also be a plus. He may not have the "baggage" of previous relationships. I have also heard many women say that a partner with Asperger's Syndrome reminds them of their father. The fact that they grew up with a parent with Asperger's traits may also have influenced their choice of partner in adulthood.

And the fact that a person with Asperger's syndrome entered into a relationship quite late can also be a plus. He may not have the "baggage" of previous relationships. I have also heard many women say that a partner with Asperger's Syndrome reminds them of their father. The fact that they grew up with a parent with Asperger's traits may also have influenced their choice of partner in adulthood.

What traits do men find attractive in women with Asperger's syndrome? They may be similar to what women find attractive in men with Asperger's, especially the degree to which they are attentive. The social immaturity of a woman can attract men who are prone to guardianship and compassion. They may admire her beauty or her talents and abilities. Unfortunately, women (and sometimes men) with Asperger's have a hard time assessing a person's character and knowing when a relationship becomes "dangerous." Such women often have low self-esteem, which affects their choice of a partner for a relationship. They may become victims of various forms of violence. As one woman with Asperger's syndrome explained to me, "I had low expectations and as a result I was drawn to violent people."

They may become victims of various forms of violence. As one woman with Asperger's syndrome explained to me, "I had low expectations and as a result I was drawn to violent people."

Strategies to Improve Relationship Skills

People with Asperger's will need help developing relationships at every stage, and possibly throughout their lives. Younger children will need the help of a speech therapist to improve their conversational skills, and an educator or psychologist will help with friendship skills during their school years. Developing these skills should be a priority for an educational institution supporting a child with Asperger's Syndrome or High-Functioning Autism, as positive friendship experiences will increase self-esteem, help avoid bullying from classmates, lay the foundation for developing friendships in the future, and improve teamwork abilities. for more successful employment.

Adolescents will need truthful information about attractiveness, courtship and sexuality. While such information is readily available to typical adolescents (most often from parents, friends, and personal experiences), adolescents with Asperger's Syndrome may have difficulty obtaining it. Lack of peer help, adult information and practice will hinder the acquisition of relationship development skills. Fortunately, we now have special relationship and sexuality education programs designed specifically for teens and young people with Asperger's Syndrome that include the opportunity to get advice from a peer with the same syndrome. Several doctors and therapists in Australia are developing relationship skills training materials for adolescents and young people with Asperger's Syndrome. Such training will include everything from dating rules and a sense of style to ways to recognize and avoid dangerous partners. A valuable strategy here can be to meet socially receptive friends or relatives with a potential partner to determine if they are a good person before starting a relationship.

While such information is readily available to typical adolescents (most often from parents, friends, and personal experiences), adolescents with Asperger's Syndrome may have difficulty obtaining it. Lack of peer help, adult information and practice will hinder the acquisition of relationship development skills. Fortunately, we now have special relationship and sexuality education programs designed specifically for teens and young people with Asperger's Syndrome that include the opportunity to get advice from a peer with the same syndrome. Several doctors and therapists in Australia are developing relationship skills training materials for adolescents and young people with Asperger's Syndrome. Such training will include everything from dating rules and a sense of style to ways to recognize and avoid dangerous partners. A valuable strategy here can be to meet socially receptive friends or relatives with a potential partner to determine if they are a good person before starting a relationship.

Young people will need support and opportunities to meet new people. Here you can offer to do something or join an interest group related to their own special passion, for example, take part in Star Trek or Doctor Who fan meetings, or apply their talents, say, to taking care of animals. and join an animal welfare group. There are also opportunities to make new friends at community events, such as a local choir or adult education courses. Local support groups for parents of children with Asperger's have also established support groups for young people with Asperger's. In this case, specialists can come to the group and hold a group discussion or give advice. Such groups can provide an opportunity for the development of relationships between members of the group. The relationship between Jerry and Mary, two people with Asperger's who met at a support group in Los Angeles, has been the subject of a book and film (Crazy in Love). Some people with Asperger's Syndrome use the Internet and dating agencies to get to know someone, but this method of dating can also be used by dangerous partners, so you need to take into account the high risk when using this dating strategy.

I have noticed that adults who had prominent signs of autism in childhood (significant language delay, learning difficulties, avoidance of social situations) but progressed to high-functioning autism later in life have much less desire to develop long-term relationships. Most likely, they will be content with loneliness and will not maintain sexual relations, preferring superficial acquaintances to friendship. A sense of self-identity and self-worth in such people is achieved through a successful career and an independent life. Temple Grandin is a good example of this. Some adults with Asperger's also choose not to form close relationships for reasons that seem logical given the traits associated with the syndrome.

Jennifer explains her decision: “How can I live in the same house with a person who can touch my collection of model airplanes?” And so: "Airplane models do not want to be designed by someone else, even if it is more attractive or less dependent." However, she is quite satisfied with her life. She says, "I can assure you that falling in love and special interests are about the same feeling." For some people with Asperger's or high-functioning autism, giving up romantic relationships may be the right choice if they enjoy and fully devote themselves to their special interests, such as wildlife photography or a career in information technology. They don't fit the cultural mold that marriage and long-term relationships are the only way to achieve happiness.

She says, "I can assure you that falling in love and special interests are about the same feeling." For some people with Asperger's or high-functioning autism, giving up romantic relationships may be the right choice if they enjoy and fully devote themselves to their special interests, such as wildlife photography or a career in information technology. They don't fit the cultural mold that marriage and long-term relationships are the only way to achieve happiness.

Future Research Perspectives

We know that people with Asperger's have significant difficulties developing relationships, but there is not enough research to provide us with qualitative and quantitative data about their relationship abilities, circumstances, and experiences. A study has recently been published on the ability to maintain friendships in children with Asperger's syndrome, but there is very little research on adolescent relationships and sexuality. Dr. Isabelle Henault of Montreal is conducting a study with me on the sexual profile of people with Asperger's syndrome, and preliminary results show that this profile differs from that of ordinary people due to less sexual experience, although they develop sexual interest in the same period, which and their adolescent peers. They may also have a more relaxed attitude towards sexual diversity, such as homosexuality and bisexuality, and a rich sexual fantasy. They may be less concerned about the partner's age and cultural differences. However, further research is needed, and the Autism Interactive Network database may be useful in providing information on the romantic relationships of adolescents and young adults with Asperger's and high-functioning autism.

They may also have a more relaxed attitude towards sexual diversity, such as homosexuality and bisexuality, and a rich sexual fantasy. They may be less concerned about the partner's age and cultural differences. However, further research is needed, and the Autism Interactive Network database may be useful in providing information on the romantic relationships of adolescents and young adults with Asperger's and high-functioning autism.

Thanks to Tamara Solomatina for the translation.

Autism in adults, asperger syndrome, social skills

90,000 Aspi marriage: 25 tips for spousesTags:

Family Relations

Courtes:

Relations, Love and Creating Family

- Although ASPI (ASPI (ASPI people with Asperger's syndrome) feel attached to others, relationships are not a priority for them, unlike neurotypicals or NTs (that is, people who do not have Asperger's syndrome).

- Relations with Aspi can be characterized as a business partnership and agreements.

- Although Aspi sincerely loves her spouse, she sometimes does not know how to show it in practice.

- Aspies are often attracted to those who share their interests and passions, and this can form a good basis for a relationship.

- Aspie needs to be alone from time to time. Often the best thing a neurotypical partner can do is to give Aspie time to himself while he visits friends or goes shopping.

- Aspie often has a special interest or hobby. A neurotypical partner would do well to show interest in them, although they border on obsession. Aspie's interests may be the basis for spending time together.

- A neurotypical partner must understand Aspie's characteristics in order to work with him on their marriage. It will take patience and perseverance, as well as the understanding that Aspie exists on a different emotional level compared to the neurotypical.

- When married to an Aspie, the NT may feel frustrated by the lack of emotional and physical contact, but attention should be paid to the Aspie's strengths they bring to the relationship.

Candid communication from a neurotypical partner can help the Aspie achieve improvement in weak areas, and the Aspie spouse should also be encouraged to do what comes naturally to him.

Candid communication from a neurotypical partner can help the Aspie achieve improvement in weak areas, and the Aspie spouse should also be encouraged to do what comes naturally to him. - Aspie often has a certain weak area in marriage - does not feel the need to express love. A neurotypical partner can help him understand that this is important. Discussions about how to express love by holding hands in public and buying small gifts can be helpful, but don't be surprised if the results are funny.

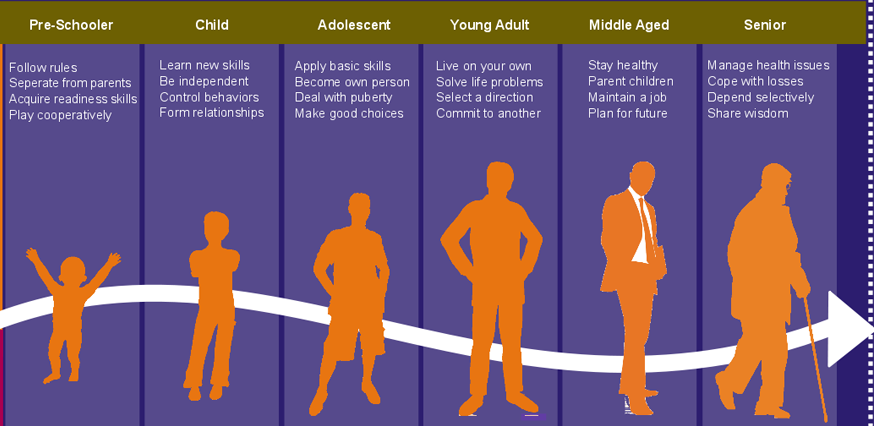

- Aspies usually mature later than neurotypicals. In their youth, they are often emotionally immature and have poor social skills. However, over time, they can develop to the point where they can enter into relationships with the opposite sex.

- Since Aspies tend to communicate and act differently from neurotypicals, they tend to attract a certain type of mate. Their spouses are focused on care and upbringing and have a strong protective instinct. In many ways, they become a link between Aspies and society.

- Since the Aspie does not have the same needs as a neurotypical partner, he may not only be unable to meet the emotional needs of his partner, but also recognize it. Thus, some dysfunctional relationship patterns develop in marriage.

- A neurotypical partner who had normal expectations of reciprocity in marriage may feel betrayed, used, and confused in a relationship with Aspie.

- In marriage, Aspie often shows great devotion to his partner, is reliable, honest and faithful.

- Neurotypical partner is often physically and emotionally exhausted, working overtime to provide for the family.

- It is important to look at Aspie's motives and not his actual behavior.

- Lowering expectations will make marriage more predictable and manageable.

- A neurotypical partner may not be satisfied with the role assigned to him by Aspie. There may also be a feeling that there is little reciprocity, equality and fairness in the relationship.

- A neurotypical partner may feel like they are sacrificing themselves on a daily basis to help achieve Aspie's priorities.

- A neurotypical partner may feel resentful of the reality of living on terms dictated by the Aspie's needs and priorities.

- Positive traits such as Aspie's fidelity and dependability are marital assets, and a neurotypical partner, praising Aspie for these qualities, strengthens the marriage.

- Sometimes relationships for Aspies are purely about practicality and convenience for him, but not about love and satisfaction of the emotional needs of a neurotypical partner.

- Aspie can sometimes be emotionally and physically withdrawn and focused on special interests to the detriment of the interests of the neurotypical partner.

- A neurotypical partner may unwittingly play the role of "personal assistant" rather than "intimate-romantic partner."

- Aspies may seem more focused on a particular interest, project, or task than on the people around them.

Learn more