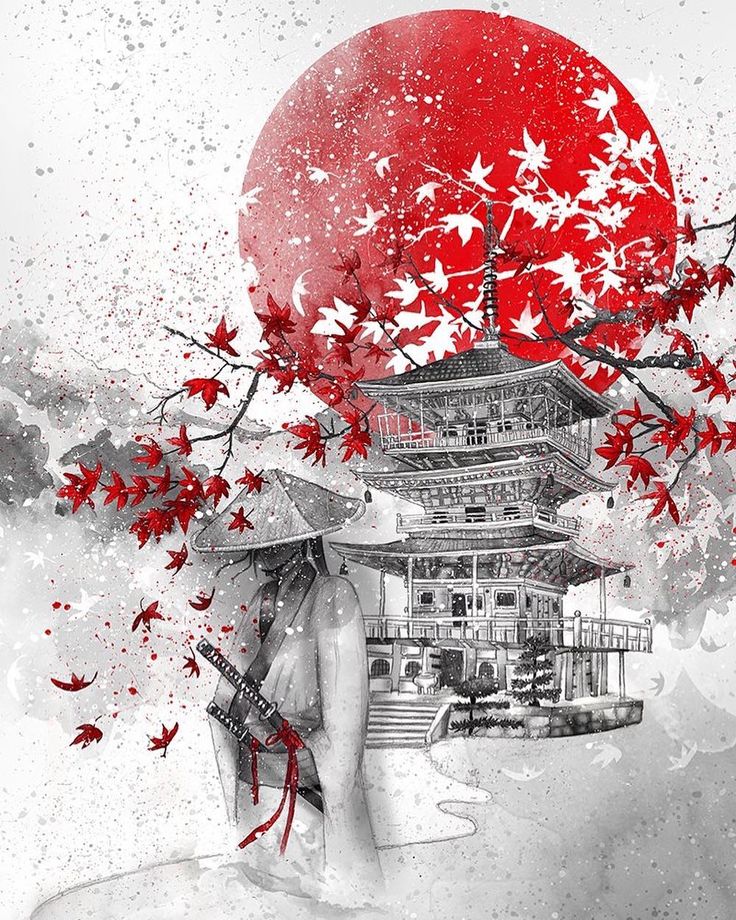

Japan introverted culture

A Country Full of Introverts? – Misha Yurchenko

Tokyo has one of the largest populations in the world but it’s also one of the loneliest cities.

The trains in Japan are usually quiet, even when packed full like a can of sardines. It’s unlikely that anyone is going to come up to you randomly and start a conversation.

Compare this to cities like San Francisco, where (even if it’s a bit uncomfortable) it’s pretty normal for you to strike up a random conversation. Whether that’s with your Uber driver or elsewhere.

How can Japan be lonely/boring? You might think of the following examples:You can hang out at a Manga cafe all day and night. Using a ticket machine or touch screen to order your food you never have to talk to another soul. You have a shower too.

You can go out to a bar by yourself and have a peaceful night without feeling any pressure to talk to anyone. No one is likely to come up to you, even in the bar.

You can go to a “tech conference” with hundreds of people and somehow not get approached by anyone, even though the point is to network. After a speaker is done giving his speech, no one will raise their hands to ask questions.

You can be passed out drunk on the train platform and nobody is going to bother you. No one is going to come to your rescue. Until the train station closes, and then the train staff will kindly escort you out.

If you take these examples at face value, it would be easy to generalize and say that, “yeh, Japan can be a very boring place!” Bullshit. I think you’d be making a big generalization.

In reality, you can have a “boring” night in any city in the world.

Here’s the deal:

Japanese people tend to keep to themselves not because they are necessarily shy or “introverted.” If you become friends with someone in Japan you’ll find out that they can be extremely talkative, super fun and extroverted.

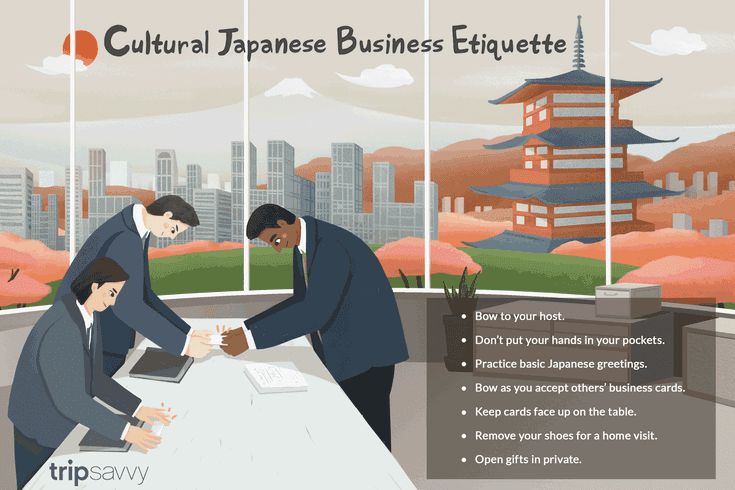

To the eyes of a more “open” or talkative Westerner, where public expression of one’s own beliefs is highly valued, Japanese people might seem quiet or reserved. Rather, not pushing one’s opinions on others and keeping to yourself is seen as a sign of humility in Japan.

Rather, not pushing one’s opinions on others and keeping to yourself is seen as a sign of humility in Japan.

If you don’t know someone, if you’re not in the “in group,” then it’s none of your business (honne and tatemae). The idea is that if we were always in each others business, conflict would arise. And on a small island nation, we’re all here together, conflict is to be avoided. Our goal is to live as harmoniously as possible. This is the fundamental difference.

But it’s not that different than where ever you’re from. There are certain things that are OK and not OK to say in public or in your workplace. We just happen to have these handy terms to refer to how we act in ingroup/outgroup situations and cool drawings like the one above.

This doesn’t mean Japanese people are “lying,” but if you cross the line and make a Japanese person feel really uncomfortable, then don’t expect to talk to them again. They will ignore you. This happens a lot if you speak your mind without taking into consideration the feelings of others and the contextual situation that might offend others around you (eh, especially on Tinder). Aka, reading in between the lines. Japan is a high-context culture.

Aka, reading in between the lines. Japan is a high-context culture.

My Japanese friends have an amazing amount of energy. They’re like the rest of us — they party hard, throw up, get angry with their bosses, and love adventures. They have no problem telling me I am wrong or calling me out on bullshit. They like going to 2-day raves and doing back-to-back karaoke sessions and wearing pasties on their nipples.

What does this all mean?If you are a traveler in Japan you have to keep in mind that the society operates in a fundamentally different way. It’s very structured. Your pick up lines aren’t going to work. Your usual approach of just “winging it” as a backpacker might not work.

Let go of those expectations and beliefs.

You are unlikely to have a super, awesome fun time unless you A) Have a local Japanese guide or friend to show you around and/or B) Properly plan out a trip rather than just winging it.

If you’re living here, I’d say Japan is a great place if you are an introvert because you don’t feel forced to do things or go out. You don’t have the fear of missing out that felt so prevalent when I was in the U.S.

You don’t have the fear of missing out that felt so prevalent when I was in the U.S.

But when you want to find those things, when you want to go to a meet up or indulge or skydive or meet people or dance at salsa bars, there are plenty of people you will find that have similar interests.

4 Reasons Why Japan is an Introverted Traveller’s Paradise – Les Talk, More Travel

Mt. Misen, MiyajimaI’m a major introvert. I like meeting new people and hanging out with friends, but need a good dose of alone time afterwards to curl up in the fetal position re-energize. When travelling solo, I will almost always choose to spend time touring around on my own, rather than with a “new friend” (i.e. person I just met who I have to make small talk with).

When I visited Japan, I was feeling particularly introverted. I hadn’t travelled across the Pacific to get there; I’d come over on an hour-long flight from Seoul, where I was living at the time. I really just wanted to see all the cool things during the day, and read or Skype my then-girlfriend in the evenings. I was a little worried about whether I would be missing out, but it turns out Japan is a great destination for solo-travelling introverts!

I was a little worried about whether I would be missing out, but it turns out Japan is a great destination for solo-travelling introverts!

Here are 4 reasons why Japan might appeal to other solitary souls:

- Eating at the counter.

My biggest worry about being on my own was that I might miss out on dining experiences. In South Korea, there are a lot of meals that simply aren’t available to people eating solo. In Japan, this wasn’t the case! Lots of restaurants have counter seating available (or as the only option), where the chef cooks right in front of you. This is awesome! You’re essentially getting front row tickets to the most rewarding cooking show ever, and there’s no need to fiddle with your phone or guidebook while you watch.

Yaki udon- Shrines, temples, and gardens.

Though there may be lots of tourists at the well-known ones, shrines, temples and gardens in Japan are all great places to quietly get lost. Most people don’t choose sanctuaries as their go-to sites for meeting new travel buddies, so you should be safe! At Fushimi Inari in Kyoto, I was able to find lots of empty walking trails and tranquil tea houses (in November). Ironically, the two times I ended up running into chatty travellers and hanging out for a bit were at a temple and a shrine, so I could be way off with this one.

Most people don’t choose sanctuaries as their go-to sites for meeting new travel buddies, so you should be safe! At Fushimi Inari in Kyoto, I was able to find lots of empty walking trails and tranquil tea houses (in November). Ironically, the two times I ended up running into chatty travellers and hanging out for a bit were at a temple and a shrine, so I could be way off with this one.

- Capsule hotels.

This was not on my radar when I was in Japan, but what could be more introvert-friendly than sleeping inside of a person-sized capsule?!? Apparently the hallways can get a bit noisy, but who cares when you are inside your own little cocoon of happiness?! That is like my dream.

Not a capsule. But also a good option.If the novelty wears off, another option (if you’re on a budget) is to stay in a small dorm in a hostel. I chose 4-person female dorms at K’s House hostels in Hiroshima and Kyoto, and had great experiences with quiet and respectful dorm mates. These hostels have great (but not obnoxiously loud) common areas, if you do feel like mingling.

These hostels have great (but not obnoxiously loud) common areas, if you do feel like mingling.

- Getting lost in the crowds.

While being an obvious foreigner isn’t exactly the key to blending in in East Asia, Tokyo’s large population makes it easy enough to do. Whether you’re hanging out at a busy Starbucks, crossing the scramble intersection in Shibuya, suffering from sensory overload in Harajuku or Shinjuku, or people watching in Yoyogi Park, you can easily spend all of your time around people, absorbing the wild vibe of the city, without letting it drain your energy.

I definitely would go back to Japan with friends or a partner. It would open the door to going out, trying things like karaoke, and splitting costs. However, I’d probably be just as happy to go back on my own! It’s a great place for an introvert (or an extrovert, or those of you who wish to remain vert-less) to be both engaged and introspective, and to can hide in crowds or get lost in quiet spaces.

Anything to add? Let me know!

Like this:

Like Loading...

Leslie

I’m Leslie (Les Talk!): an introvert (Less Talk!) who is also super gay (Lez Talk!), and loves to travel (More Travel)! Les Talk, More Travel is about local and international adventures for intrepid queers, lovers of the Pacific Northwest, and other interested humans!

Author archive Author website

Asia, Introvert, Japan, Travel

accommodation, asia, food, introvert, japan, travel

Previous post Next post

Culture - Literature - Prose

Japanese prose is characterized by a variety of ideological and artistic trends, presenting a complex picture of the interaction of socio-economic factors, a renewing cultural tradition and independent searches of individual artists. Being the fruit of more than a thousand years of development of the national artistic tradition, at the same time it is included as an important component in the modern world literary stream.

Being the fruit of more than a thousand years of development of the national artistic tradition, at the same time it is included as an important component in the modern world literary stream.

The first written monuments of Japan belong to the 7th - 8th centuries. AD These are the Taihoryo Code of Laws, the Kojiki Historical and Mythological Code, the Nihongi Historical Chronicle, and the Fudoki Historical and Geographical Descriptions of the provinces of what was then Japan. At the same time, it should be noted that the "Kojiki" and "Nihongi" in the myths, legends and songs contained in them give a lot of evidence of the existence of ancient oral prose, which, due to the lack of a national writing system, was not written down before the borrowing of Chinese characters.

IX - XI centuries were marked by the emergence of a number of narrative genres. The first prose work of fiction was Taketori Monogatari. Under the influence of poetry, a genre of lyrical story (uta - monogatari) is formed, in which poetic and prose texts are organically combined. The Tale of Ise (Ise monogatari) (X century) was recognized as the best example of this genre. A genre of essay appears - zuihitsu, the founder of which is the writer Sei Shyonagon, the author of "Notes at the Headboard" ("Makura no suck") (late 10th - early 11th century). Peru another outstanding writer - Murasaki Shikibu owns one of the first novels in world literature "Genji Monogatari" (The Tale of Genji") (beginning of the XI century). The revival of political and cultural contacts with the continent was accompanied by a wide spread of Chinese and other plots (the collection "Konjaku monogatari, 12th century).

The Tale of Ise (Ise monogatari) (X century) was recognized as the best example of this genre. A genre of essay appears - zuihitsu, the founder of which is the writer Sei Shyonagon, the author of "Notes at the Headboard" ("Makura no suck") (late 10th - early 11th century). Peru another outstanding writer - Murasaki Shikibu owns one of the first novels in world literature "Genji Monogatari" (The Tale of Genji") (beginning of the XI century). The revival of political and cultural contacts with the continent was accompanied by a wide spread of Chinese and other plots (the collection "Konjaku monogatari, 12th century).

Prolonged internecine wars (beginning from the 12th century) and the entry into the historical arena of the military-feudal estate of the samurai gave rise to the emergence of the military epic genre - gunki, in which the process of formation and transformation of the samurai ideology can be traced. The most famous among gunki are "Heike monogatari" ("The Tale of the House of Taira", XIII century) and "Taiheiki" ("The Tale of the Great World", XIV century).

In connection with the growth of cities and trade in the XVI - XVII centuries. the flowering of the literature of the third estate begins (in Japan - the third and fourth estates, i.e. artisans and merchants). The most important writer of this period is Ihara Saikaku. In his works, such as "Five women who made love", and others, the life of the Japanese townspeople of the era of the developed Middle Ages was reflected. In the field of dramaturgy, the work of Chikamatsu Monzaemon, who created the genres of historical and everyday drama - jidaigeki and sevamono, was of great importance.

In the XVIII - XIX centuries. in the work of Takizawa Bakin develops the genre of didactic novel ("The Story of Eight Dogs", 1814). Ueda Akinari made his debut as part of moralistic literature, but the novels of adventure and romantic content brought literary fame to the writer ("Moon in the Fog", 1768). An everyday novel in the genres of kibyoshi and kokkeibong, depicting scenes from urban life in comic tones, is represented by the work of Shikitei Samba, the author of the stories "Modern Bath" (1813 - 1814) and "Modern Barber", 1813 - 1814). A brilliant example of a picaresque novel was created by Jippensha Ikku ("Journey on foot along the Tokaidos highway"). The sentimental novel receives its final expression in the works of Tamenaga Shunsui ("The Plum Calendar of Love" and others).

A brilliant example of a picaresque novel was created by Jippensha Ikku ("Journey on foot along the Tokaidos highway"). The sentimental novel receives its final expression in the works of Tamenaga Shunsui ("The Plum Calendar of Love" and others).

Late 19th - early 20th century - one of the most turbulent and difficult eras in the history of Japanese culture. After the Meiji restoration, under the influence of changes in the social order and the rapid penetration of European art and literature into the country, the process of forming new types and forms of artistic vision began. One of the first to demand the creation of a new literature that meets the challenges of the era was Tsubouchi Shoyo, who outlined his views in the treatise The Essence of the Novel (1865). Among the most original artists of that period is the writer Higuchi Ichiyo, who created realistic images on the pages of her stories.

The dominant trend in the prose of the tenth - twenties of the XX century. became the current of naturalism (shizenshugi). The works of its best representatives - Futabatei Shimei, Tokutomi Roca, Natsume Soseki, Kunikida Doppo, Shimazaki Toson and others - reflect the features of critical realism. The genre of the ego novel (watakushi shosetsu - "a novel about oneself"), the founder of which is considered to be Tayama Katai, has become widespread.

became the current of naturalism (shizenshugi). The works of its best representatives - Futabatei Shimei, Tokutomi Roca, Natsume Soseki, Kunikida Doppo, Shimazaki Toson and others - reflect the features of critical realism. The genre of the ego novel (watakushi shosetsu - "a novel about oneself"), the founder of which is considered to be Tayama Katai, has become widespread.

In the second decade of the XX century. in prose, a number of new trends appear, marking a departure from the principles of naturalism. A trend of neo-romanticism is emerging, whose representatives - Nagai Tatsuo, Tanizaki Junichiro, Kinoshita Mokutaro and others - also called themselves a "group of aesthetes" (tambiha). A prominent role in literary life began to be played by writers belonging to the neo-humanism (shinjinshugi) movement - Arishima Takeo, Musyanokoji Saneatsu, Shiga Naoya and others - who founded the literary magazine and society "Shirakaba" ("White Birch").

The current of neo-sensualism (shinkankakuku) put forward such famous writers as Kawabata Yasunari, Yokomitsu Riichi, Sato Haruo and others who saw the ideal of beauty in the simplicity and naturalness of human relations, in the fusion of man with nature. One of the greatest writers of this period is Ryunosuke Akutagawa, a brilliant stylist and deep psychologist, who was keenly aware of the contradictions inherent in his contemporary society. The tragedy of modern life, the spiritual split of personality, is also filled with the work of another famous writer - Dazai Osamu. Under these conditions, an atypical creative path was chosen by Miyazawa Kenji, who entered the history of Japanese literature as a children's writer. His works are imbued with humor and optimism, as well as love for the land and rural workers. A different approach to the problems of reality is demonstrated by the work of Kikuchi Kan, who began his career by exposing the falsity of feudal morality, and later turned to the genre of "entertainment literature".

One of the greatest writers of this period is Ryunosuke Akutagawa, a brilliant stylist and deep psychologist, who was keenly aware of the contradictions inherent in his contemporary society. The tragedy of modern life, the spiritual split of personality, is also filled with the work of another famous writer - Dazai Osamu. Under these conditions, an atypical creative path was chosen by Miyazawa Kenji, who entered the history of Japanese literature as a children's writer. His works are imbued with humor and optimism, as well as love for the land and rural workers. A different approach to the problems of reality is demonstrated by the work of Kikuchi Kan, who began his career by exposing the falsity of feudal morality, and later turned to the genre of "entertainment literature".

After the rise of the leftist movement in Japan, which began after the end of the First World War and the Bolshevik putsch in Russia, a literary trend known as the "movement for proletarian literature" began to play a certain role in the cultural life of the country. Its largest representatives - Kobayashi Takiji, Tokunaga Sunao, Nakano Shigeharu and others - considered their creative activity as part of the struggle of the left wing of society. With the onset of the 30s, this movement was suppressed. In those years, many writers were forced to renounce their former views and fell under the influence of nationalist propaganda. A ban was imposed on the publication of works not only by leftists, but also by a number of authors far from politics.

Its largest representatives - Kobayashi Takiji, Tokunaga Sunao, Nakano Shigeharu and others - considered their creative activity as part of the struggle of the left wing of society. With the onset of the 30s, this movement was suppressed. In those years, many writers were forced to renounce their former views and fell under the influence of nationalist propaganda. A ban was imposed on the publication of works not only by leftists, but also by a number of authors far from politics.

The rapid restoration of the literary process came after the end of World War II. Veterans of the "movement for proletarian literature" came up with new works. Miyamoto Yuriko published the novels "Two Houses" (1947) and "Milestones" (1947 - 1949) one after another, Tokunaga Sunao wrote the story "Sleep in peace, wife!" (1946 - 1948), Nakano Shigeharu - the story "Five shaku wine" (1947).

At the same time, another group of writers united around the magazine "Kindai Bungaku", which was called "post-war" (sengoha). It included writers of the middle generation - Noma Hiroshi, Ooka Shohei, Shiina Rinzo, Nakamura Shinichiro, Umezaki Haruo, Kato Shuichi, Takeda Taijun and others. The main pathos of the work of these writers was the struggle for the rights of modern man, the condemnation of militarism. Thus, a protest against war, against obstacles to the free development of the human personality, was voiced in such works as "Zone of the Void" by Noma Hiroshi, "Lights on the Plain" by Ooka Shohei, "The End of the Viper" by Takeda Taijun and others. The epic Nogami Yaeko "Labyrinth" was devoted to the fate of youth in the prewar and war years. Anti-war themes have taken a central place in the work of Gomikawa Junpei, author of the novel The Conditions of Human Existence. Ibuse Masuji's novel Black Rain, a documented story about the Hiroshima atomic tragedy, received a wide response in society. Important social issues were raised by Ishikawa Tatsuzo in his novels "Reed in the Wind" and "Wall of Man". High artistic skill was demonstrated by Endo Shusaku in the stories "Sea and Poison" and "The Kingdom of Gold".

It included writers of the middle generation - Noma Hiroshi, Ooka Shohei, Shiina Rinzo, Nakamura Shinichiro, Umezaki Haruo, Kato Shuichi, Takeda Taijun and others. The main pathos of the work of these writers was the struggle for the rights of modern man, the condemnation of militarism. Thus, a protest against war, against obstacles to the free development of the human personality, was voiced in such works as "Zone of the Void" by Noma Hiroshi, "Lights on the Plain" by Ooka Shohei, "The End of the Viper" by Takeda Taijun and others. The epic Nogami Yaeko "Labyrinth" was devoted to the fate of youth in the prewar and war years. Anti-war themes have taken a central place in the work of Gomikawa Junpei, author of the novel The Conditions of Human Existence. Ibuse Masuji's novel Black Rain, a documented story about the Hiroshima atomic tragedy, received a wide response in society. Important social issues were raised by Ishikawa Tatsuzo in his novels "Reed in the Wind" and "Wall of Man". High artistic skill was demonstrated by Endo Shusaku in the stories "Sea and Poison" and "The Kingdom of Gold".

Old recognized masters also appeared in print. Several works were published by Nagai Kafu, including "Kafu's Diary" and "Diary of a Distressed Man", in which the writer expressed a sharply negative attitude towards the war. He published the novel "Small Snow", the publication of which was suspended even before the war because of its "lack of ideas", and Tanizaki Junichiro. In the later novels The Key and Diary of a Mad Old Man, Tanizaki turned to the theme of beauty and love, which had occupied him throughout his life, as destructive forces that bring death to those who fall under their power. The post-war period was also fruitful for Kawabat Yasunari, who created a number of outstanding works at that time, for which he was awarded at 1968 Nobel Prize.

In the 1950s, Japanese society began to move away from post-war value orientations, and nationalist sentiments intensified among some of the creative intelligentsia. They received extreme expression in the work of Mishima Yukio - writer, playwright, film director and actor, author of such novels as "Confession of a Mask", "Thirst for Love", "Golden Pavilion", "After the Banquet", "Spring Snow", "Temple on dawn", trilogy "Patriot", "Chrysanthemum". "Voice of a Fallen Hero" and "Sea of Plenty". In the same years, a generation of so-called "third new" (daisan - no shinjin) appeared on the scene - Yasuoka Shotaro, Yoshiyuki Junnosuke, Shono Junzo, Kojima Nobuo and others. In their work, socio-political issues give way to the depiction of the everyday life of an ordinary person, an analysis of his inner world, those moral conflicts that he encounters in modern life. Because of their interest in describing their "personal experience," these writers have also been called the "introverted" or "introverted generation" (naiko sedai).

"Voice of a Fallen Hero" and "Sea of Plenty". In the same years, a generation of so-called "third new" (daisan - no shinjin) appeared on the scene - Yasuoka Shotaro, Yoshiyuki Junnosuke, Shono Junzo, Kojima Nobuo and others. In their work, socio-political issues give way to the depiction of the everyday life of an ordinary person, an analysis of his inner world, those moral conflicts that he encounters in modern life. Because of their interest in describing their "personal experience," these writers have also been called the "introverted" or "introverted generation" (naiko sedai).

Major achievements in modern Japanese prose are associated with the names of Abe Kobo, Kaiko Ken and Oe Kenzaburo. In such works created by Abe Kobo as "Woman in the Sands", "Alien Face", "Man - Box" and others, the writer draws an allegorical picture of a sick world in which a person is deprived of the opportunity to lead a worthy existence. New facets of the conflict between the individual and society were reflected in his work by Kaiko Ken (the novels "Japanese Threepenny Opera", "Summer Darkness" and others). In the novels of Oe Kenzaburo "Belated Youth", "Waters Embraced Me to My Soul", "Games of Contemporaries", "Football of 1868", "A Letter in a Lovingly Remembered Year", "Quiet Life", "Last Short Story" and others, the most important philosophical and moral - ethical problems of humanity. At 1994 Oe Kenzaburo received the Nobel Prize.

In the novels of Oe Kenzaburo "Belated Youth", "Waters Embraced Me to My Soul", "Games of Contemporaries", "Football of 1868", "A Letter in a Lovingly Remembered Year", "Quiet Life", "Last Short Story" and others, the most important philosophical and moral - ethical problems of humanity. At 1994 Oe Kenzaburo received the Nobel Prize.

Every year the army of Japanese writers is replenished with new names. In the 90s, in particular, Tsushima Yuko, Murakami Ryu, Nakagami Kenji, Murakami Haruko and others joined these masters. On the whole, Japanese prose stands out for its extremely high rates of development. Its modern direction is determined by the desire of writers to find an adequate artistic form of mastering the complex problems and contradictions of our time.

Culture of guilt and culture of shame-1. Japan, the West and personality models. Igor Kon.

.... What is the specificity of the Japanese model of man?

The new European model of a person affirms his self-worth, unity and wholeness; fragmentation, the plurality of "I" is perceived here as something painful, abnormal, traditional Japanese culture, emphasizing the dependence of the individual and his belonging to a certain social group, perceives the personality rather as a plurality, a combination of several different "circles of duties": duty towards the emperor; obligations towards parents; in relation to people who have done something for you; obligations towards oneself.

The European philosophical and ethical tradition evaluates the personality as a whole, considering its actions in different situations as manifestations of the same essence. In Japan, the assessment of a person is necessarily correlated with the "circle" of the evaluated action.

"The Japanese avoid judging the actions and character of a person as a whole, but divide his behavior into isolated areas, each of which, as it were, has its own laws, its own moral code."

European thought tries to explain a person's act "from within": whether he acts out of gratitude, out of patriotism, out of self-interest, etc., that is, in moral terms, decisive importance is attached to the motive of the act. In Japan, behavior is derived from a general rule, a norm.

What is important is not why a person does this, but whether he acts in accordance with the hierarchy of duties accepted by society.

These differences are connected, of course, with a whole range of social and cultural conditions.

Traditional Japanese culture, strongly influenced by Confucianism and Buddhism, is non-individualistic. The personality appears in it not as something intrinsically valuable, but as a knot of private, particularistic obligations and responsibilities arising from the individual's belonging to the family and community.

If a European realizes himself through his differences from others, then the Japanese realizes himself only in the inseparable system "I-others", as "his part" or "his share" ("ji-bun").

The last is not an abstract substantial "I", it is present in the outer layers of the personality, in its concrete relations with others. Therefore, the Japanese do not have a division into "internal" and "external" and the opposition of feelings of "guilt" and "shame" derived from it.

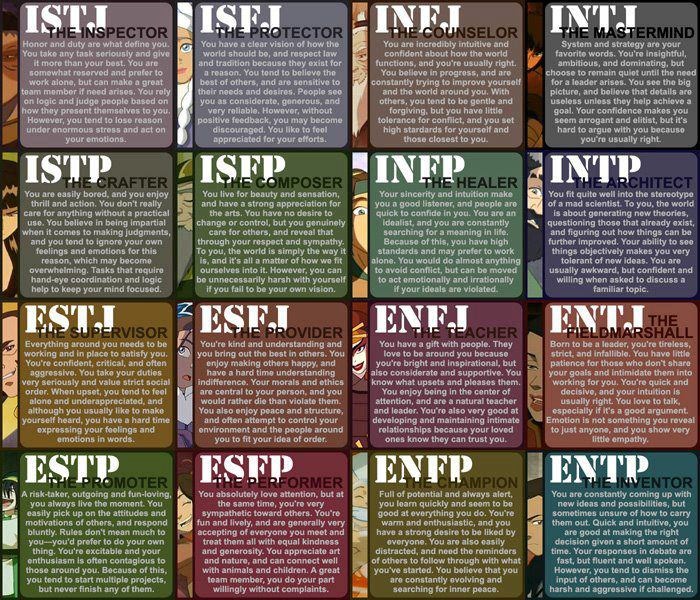

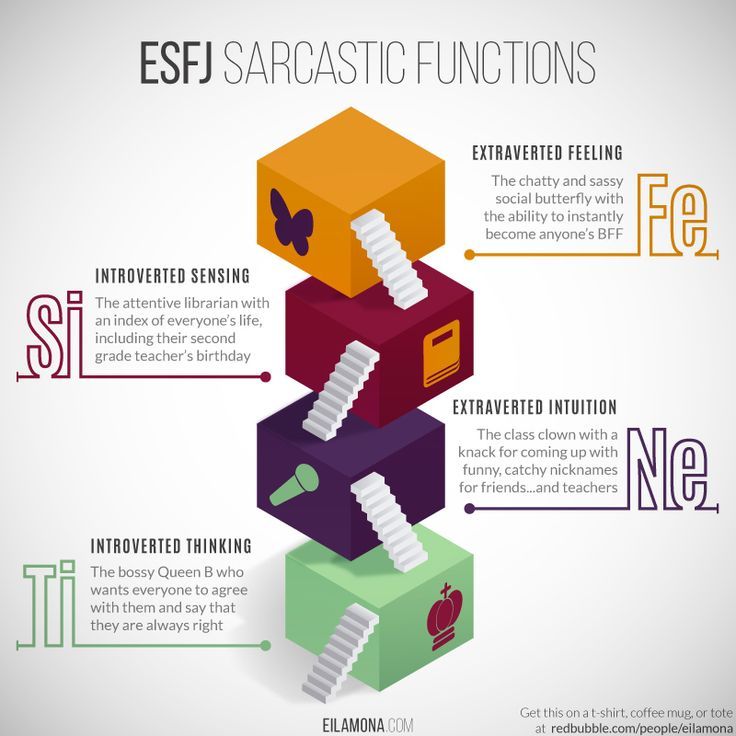

At one time, the American anthropologist R. Benedict defined Japanese culture as an extraverted "culture of shame", in contrast to the introverted Western "guilt culture". However, according to the results of psychological testing, the Japanese seem to be significantly more introverted than Europeans, and this is consistent with the value orientation of their traditional culture.

However, according to the results of psychological testing, the Japanese seem to be significantly more introverted than Europeans, and this is consistent with the value orientation of their traditional culture.

The Japanese philologist Mori Joji figuratively compared the European personality type with an egg in a shell, and the Japanese personality type with an egg without a shell.

"Egg in shell" has a hard, non-elastic outer shell. Since the inside of the egg is protected by the shell, it is difficult to break it. But when the pressure from the outside exceeds the allowable limits, the egg instantly bursts. Since the inside is enclosed in a shell, each egg looks like a separate object that can be autonomously moved in space and endowed with its own name. Dust adhering to a smooth and hard shell does not penetrate inside and is easily erased. By appearance it is impossible to recognize whether the egg is spoiled, but external protection protects it to a certain extent from contamination. In contrast, the "shellless egg" is soft and supple. Not protected by a shell, it is relatively easy to collapse, but not from a sudden blow, but slowly, succumbing to pressure from outside. Since such an egg is relatively amorphous, it cannot be given a name and carried from place to place without a vessel. Dust easily sticks to it, which is difficult to remove; but through the soft film surrounding it, it is easy to recognize the decomposition that has begun.

In contrast, the "shellless egg" is soft and supple. Not protected by a shell, it is relatively easy to collapse, but not from a sudden blow, but slowly, succumbing to pressure from outside. Since such an egg is relatively amorphous, it cannot be given a name and carried from place to place without a vessel. Dust easily sticks to it, which is difficult to remove; but through the soft film surrounding it, it is easy to recognize the decomposition that has begun.

From this point of view, for a European ("solid personality"), the inner world and his own "I" are something really tangible, and life is a battlefield where he realizes his principles. The Japanese are much more concerned with maintaining their "soft" identity, which is ensured by belonging to a group. Hence the value system. Deprived of the "shell", the personality changes form relatively easily, adapting to circumstances, but as soon as the pressure weakens, it returns to its original state.

Conformism, the desire to be "like everyone else", has never been considered a vice in Japan. Happiness is conceived here as the coordination of the external form of life with the views and assessments of others. This also corresponds to the etymology of the word "happiness" in Japanese ("happiness" - "shiawase" - derived from the verbs "suru" - "to do" and "awaseru" "to connect", "adjust", "adapt"). With the concept of "awase", adaptation to the interlocutor, the idea of \u200b\u200bliberation from selfhood is also connected.

Happiness is conceived here as the coordination of the external form of life with the views and assessments of others. This also corresponds to the etymology of the word "happiness" in Japanese ("happiness" - "shiawase" - derived from the verbs "suru" - "to do" and "awaseru" "to connect", "adjust", "adapt"). With the concept of "awase", adaptation to the interlocutor, the idea of \u200b\u200bliberation from selfhood is also connected.

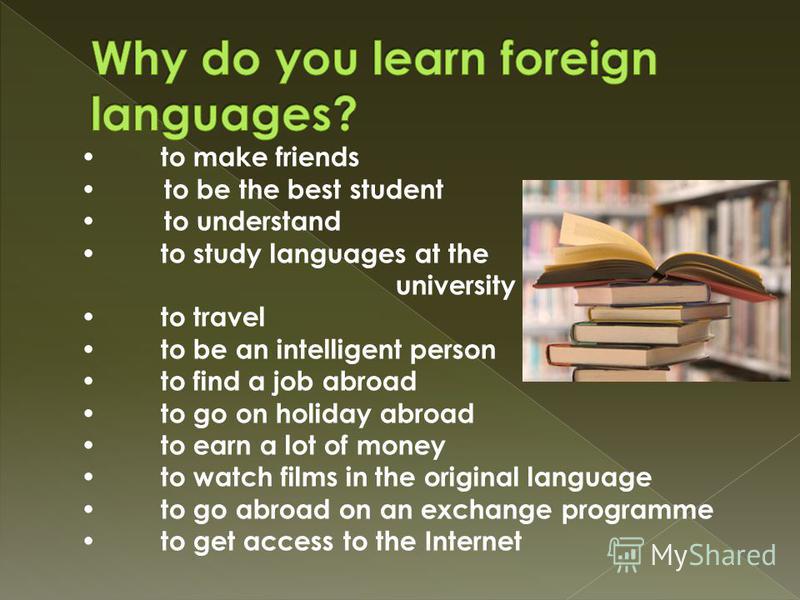

Although the Japanese language has a rich vocabulary of emotions, the Japanese do not trust verbal communication, considering words as a hindrance to true understanding. According to the Japanese writer Y. Kawabata, the truth lies not in what is said, but in what is meant.

Is it any wonder that when comparing the self-descriptions of six-, nine- and fourteen-year-old children of eleven different nationalities (Americans, French, Germans, Anglo- and French Canadians, Turks, Lebanese, Bantu, etc.), answering the questions: "Who are you like this?”, “And who else are you?”, “What else can you say about yourself?”, Japanese children differed sharply from the rest in using a smaller set of self-characteristics, which was completely unrelated to their level of mental development.