How is the dsm 5 organized

What is the DSM?

The DSM is a reference handbook that most U.S. mental health professionals use to reach an accurate diagnosis. The latest version of the manual is the DSM-5-TR.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) was released on March 18, 2022 by the American Psychiatric Association (APA).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a formal classification of mental health disorders, featuring symptoms, diagnostic criteria, culture and gender-related features, and other important diagnostic information. The DSM does not include treatment guidelines.

In other words, the DSM is a tool and reference guide for mental health clinicians to diagnose, classify, and identify mental health conditions.

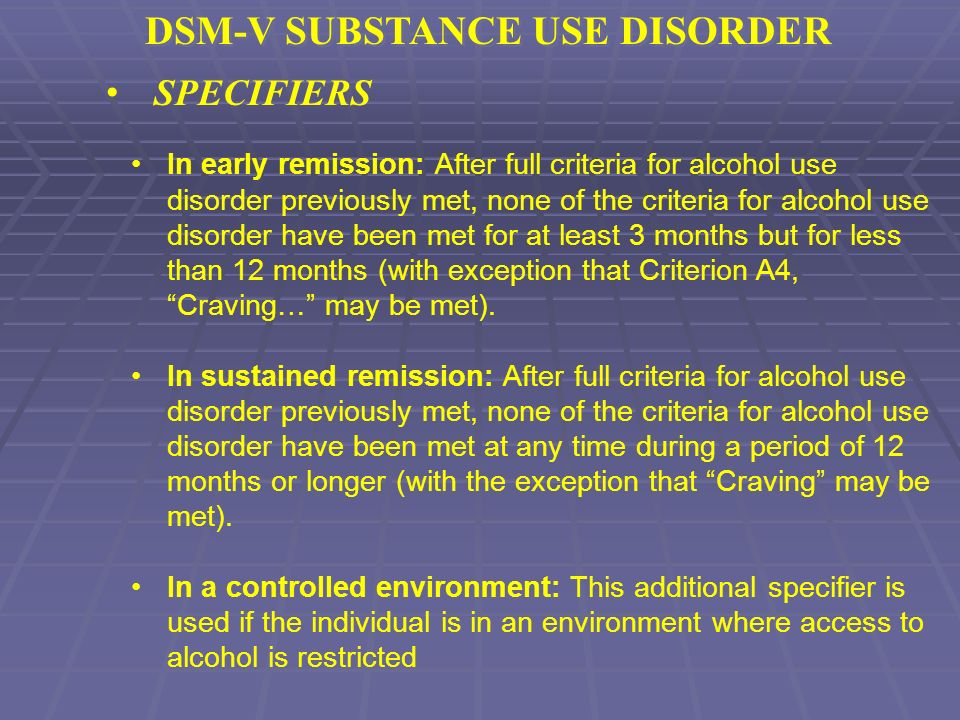

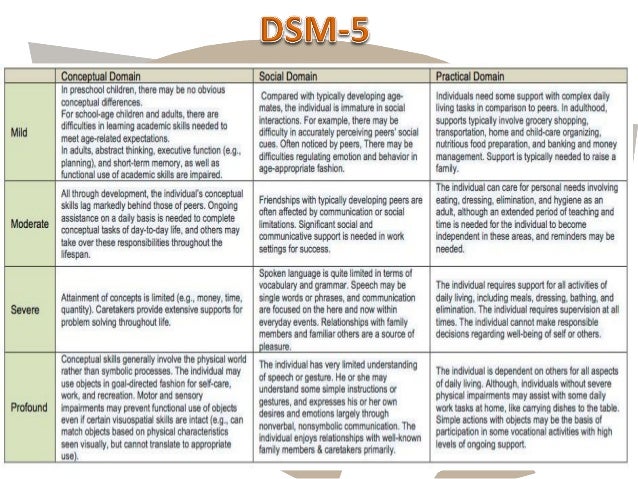

The DSM also includes “specifiers.” These are extensions to the formal diagnoses that specify one or more particular features, like onset or severity. A diagnosis can have one or more specifiers to make it more precise.

In other words, because a mental health condition doesn’t always present itself in the same way, a DSM specifier can better describe particular scenarios.

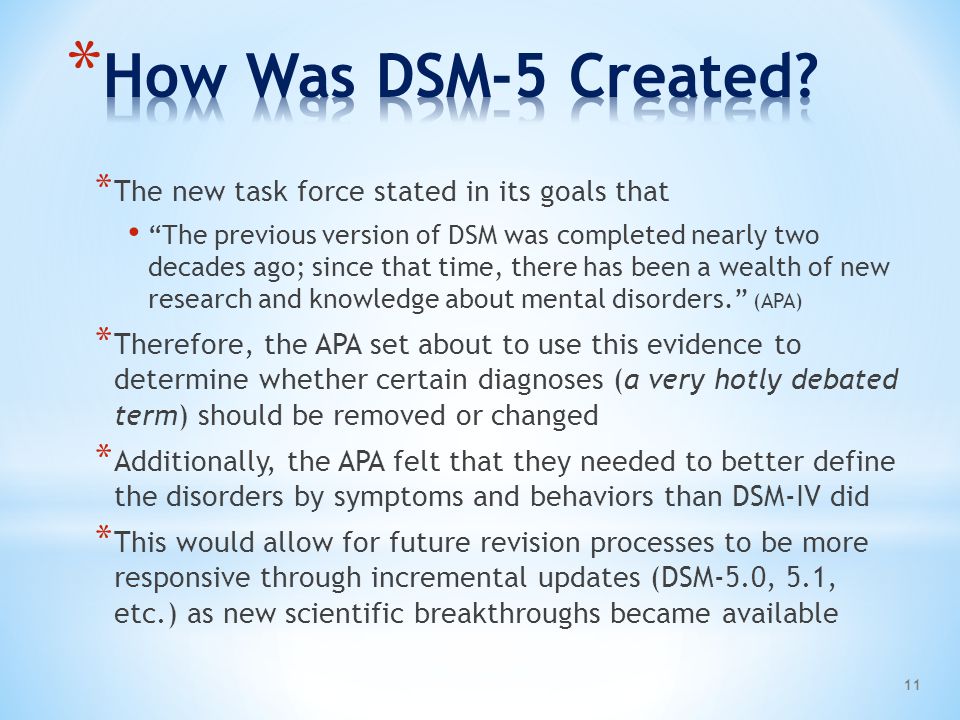

The DSM has had many revisions, to clarify, add, or remove mental health diagnoses according to the latest research and clinical consensus.

It took more than 13 years to update and finalize the book’s fifth edition and about 10 years to release the current text revision.

The DSM-5 was released in 2013 and the current version released in 2022 is the DSM-5-TR.

The difference between a new edition and a text revision is that the first one is released when new research supports the need to create, remove, or significantly revise key aspects of existing diagnoses.

A text revision, on the other hand, refers to editing the existing text to clarify some concepts, introduce inclusive language, or update statistics and references. Sometimes, like it’s the case with the DSM-5-TR, a new diagnosis might be introduced.

The first edition of the DSM was published in 1952 following an increased need to classify and define mental conditions, especially in veterans returning home after World War II.

The DSM was created to catalog mental health conditions similar to its counterpart, the International Classification of Disease (ICD).

The ICD is published by the World Health Organization (WHO) and catalogs both physical and mental conditions.

The DSM-II was released in 1968 and focused on broadening terms and definitions from the original DSM to diagnose mental health conditions better.

The biggest shift in the history of the DSM came as a result of the DSM-III, published in 1980.

This edition listed 265 categories — a big increase from 182 in the previous edition. This jump was due to an expansion of disorder subtypes, which allowed for more accurate classifications and options for a diagnosis.

The DSM-III also saw the removal of “homosexuality” as a mental condition category.

The DSM-III would later receive an update and be revised and renamed in 1987 as the DSM-III-R.

The next edition, the DSM-IV, was published in 1994 and was created alongside the WHO’s International Classification of Disease, 10th edition. This aimed to decrease inconsistencies in terminology between the two manuals.

The DSM-IV would see one final revision in 2000, named the DSM-IV-TR before the DSM-5 was released in 2013.

The latest text revision of the DSM-5 was released in 2022.

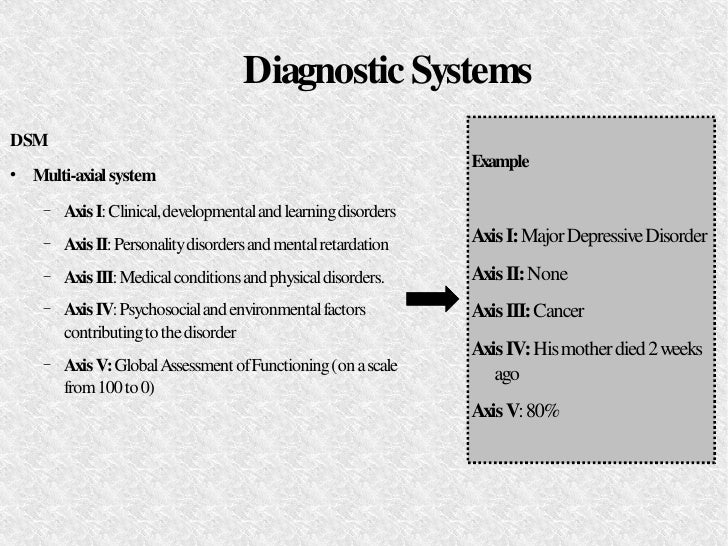

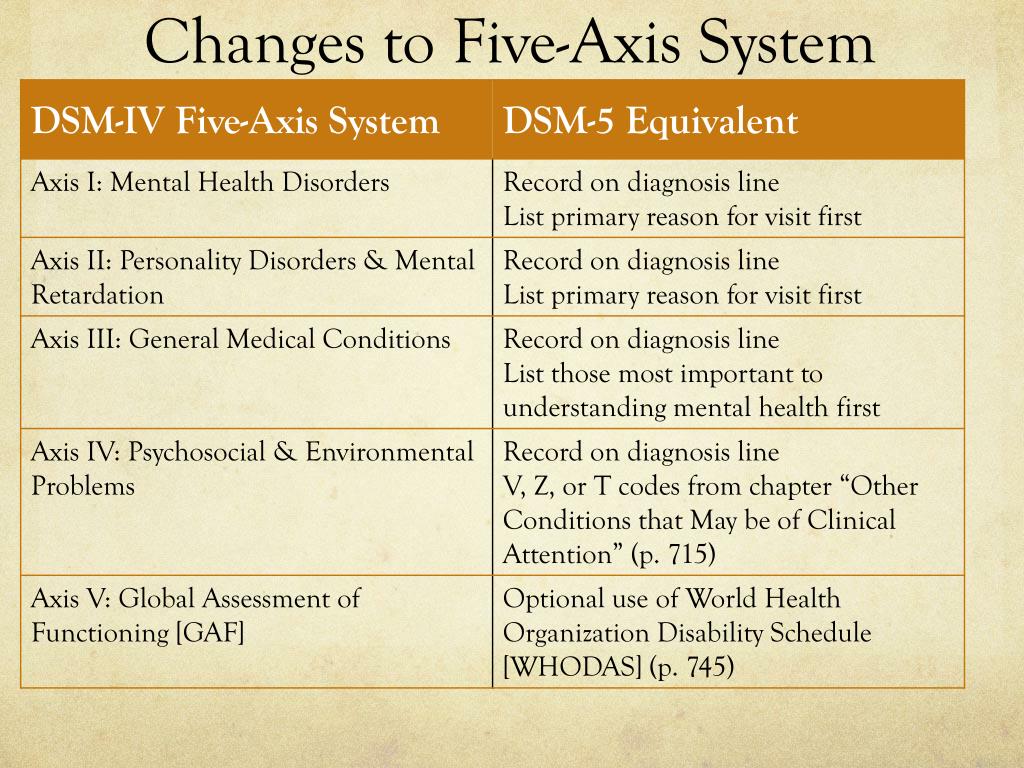

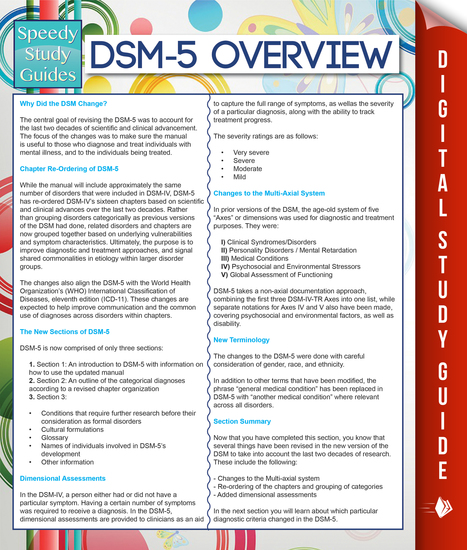

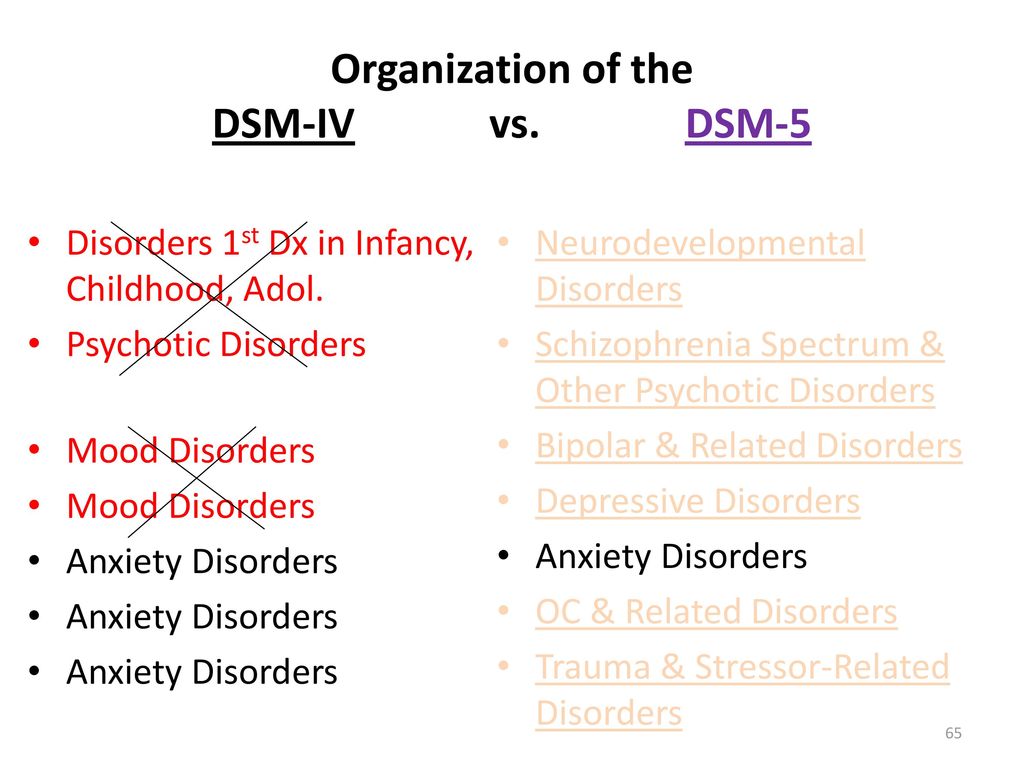

One of the biggest changes in the DSM-5 is the removal of the multiaxial assessment system to categorize diagnoses.

This evaluation method was based on multiple factors, specifically five “axes”:

- clinical disorders

- personality disorders

- general medical disorders

- psychosocial and environmental factors

- global assessment of functioning

The system was removed and replaced with a streamlined diagnostic method that combines axes I, II, and III into 1.

Additional changes in the DSM-5 include broadening the definitions to clarify certain conditions.

For example, the diagnostic label autism spectrum disorder now comprises four previously separate conditions:

- autistic disorder

- Asperger’s disorder

- childhood disintegrative disorder

- pervasive developmental disorder

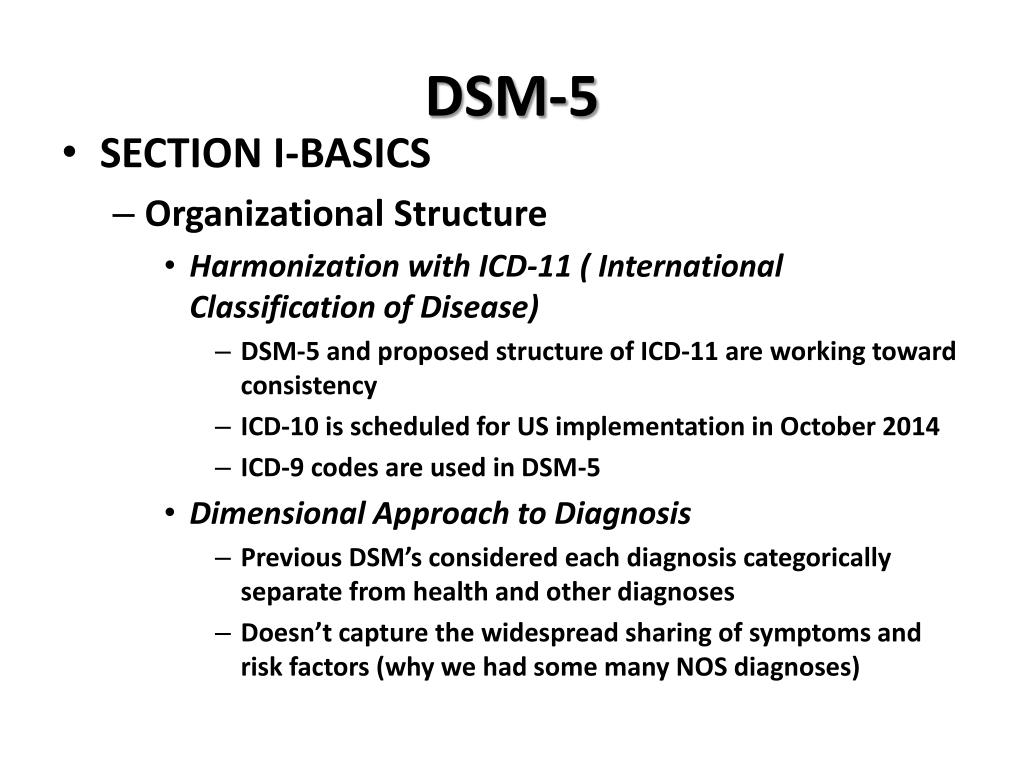

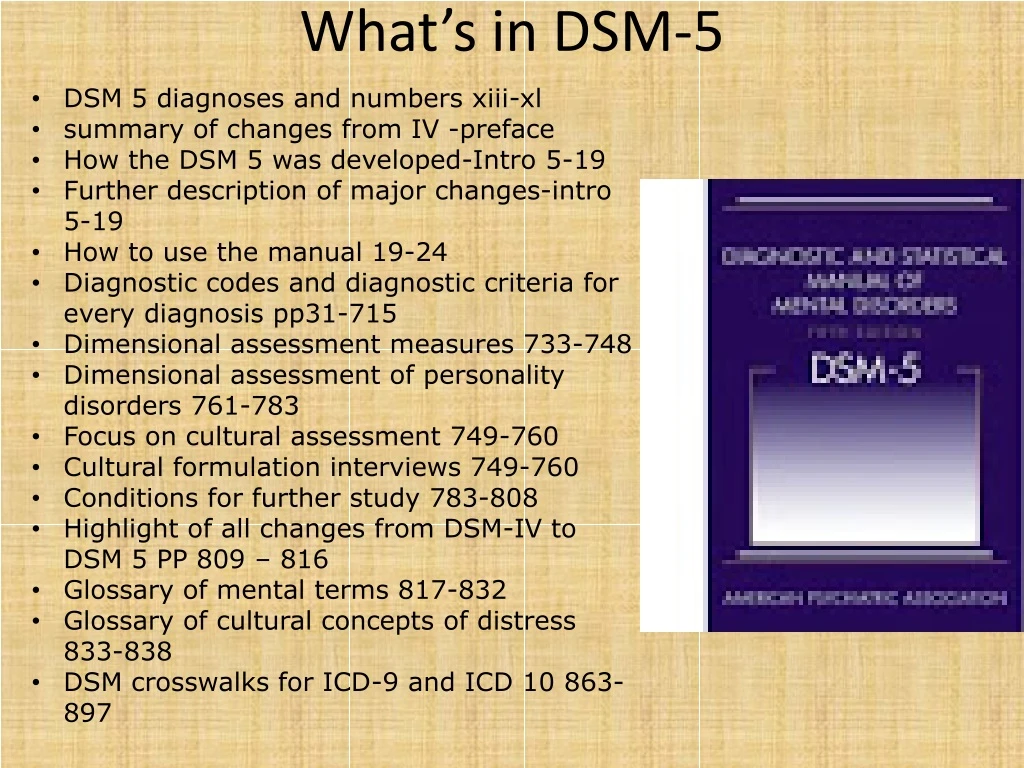

The DSM-5 is organized into three sections and an appendix.

Section II of the DSM-5 is the lengthiest because it lists all of the mental health disorders.

Here are the DSM sections:

Section I: DSM-5 Basics

This section includes an “Introduction” and “Use of the Manual” chapters, as well as a “Cautionary Statement for Forensic Use of DSM-5” chapter.

Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes

This section includes classifications and definitions of mental health disorders.

These conditions are organized alphabetically and developmentally, with all childhood conditions listed before adult on-set conditions.

Section III: Emerging Measures and Models

This section comprises chapters that discuss applying the newest mental health information — for example, assessment measures and how to account for cultural influences.

It also includes newer conditions that require further study before entering the general diagnostic classification — for example, caffeine use disorder and internet gaming disorder.

Appendix

The final section contains supplemental information such as a list of changes from the DSM-4 to the DSM-5, a glossary of technical terms, and a list of DSM-5 advisors.

Major changes in the DSM-5 from the DSM-IV

Below are links to explore additional updates and changes to the DSM-5:

- DSM-5 Released: The Big Changes

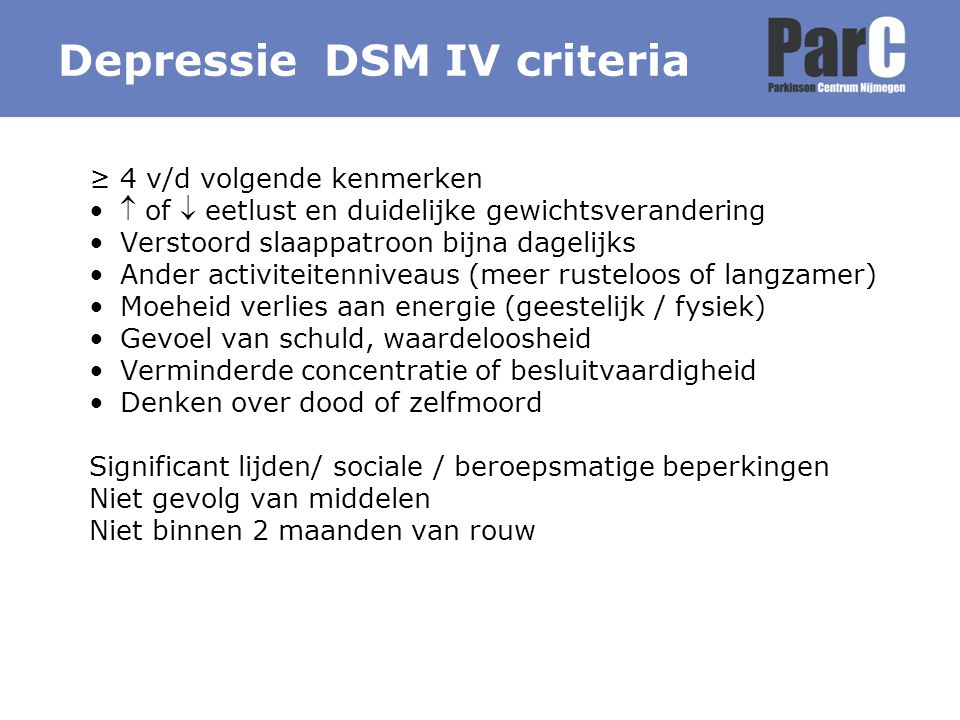

- DSM-5 Changes: Depression & Depressive Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Anxiety Disorders & Phobias

- DSM-5 Changes: Bipolar & Related Disorders

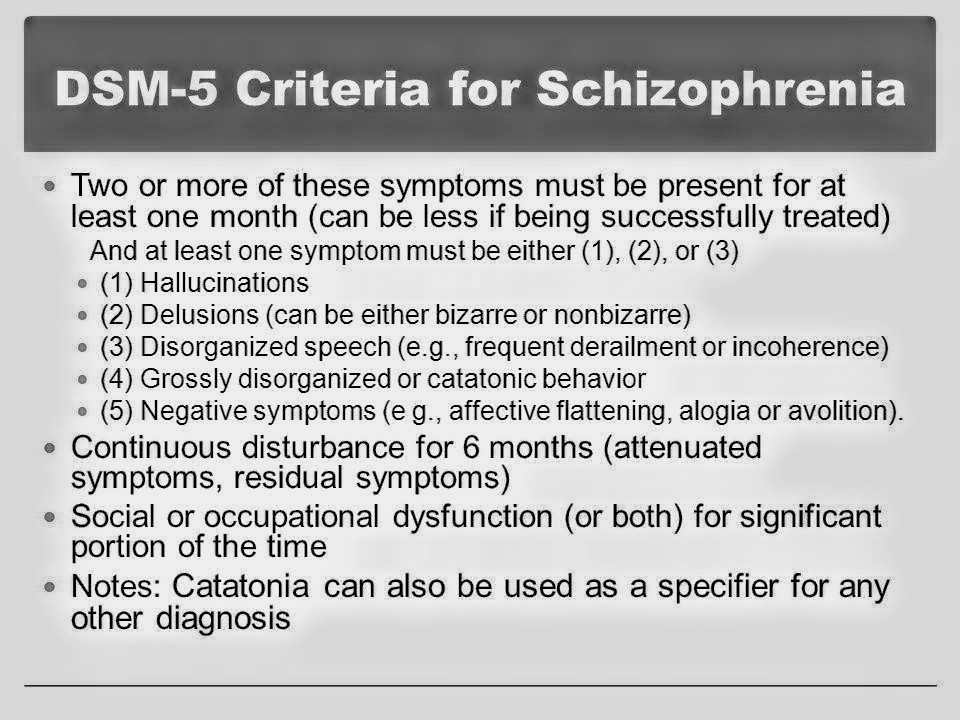

- DSM-5 Changes: Schizophrenia & Psychotic Disorders

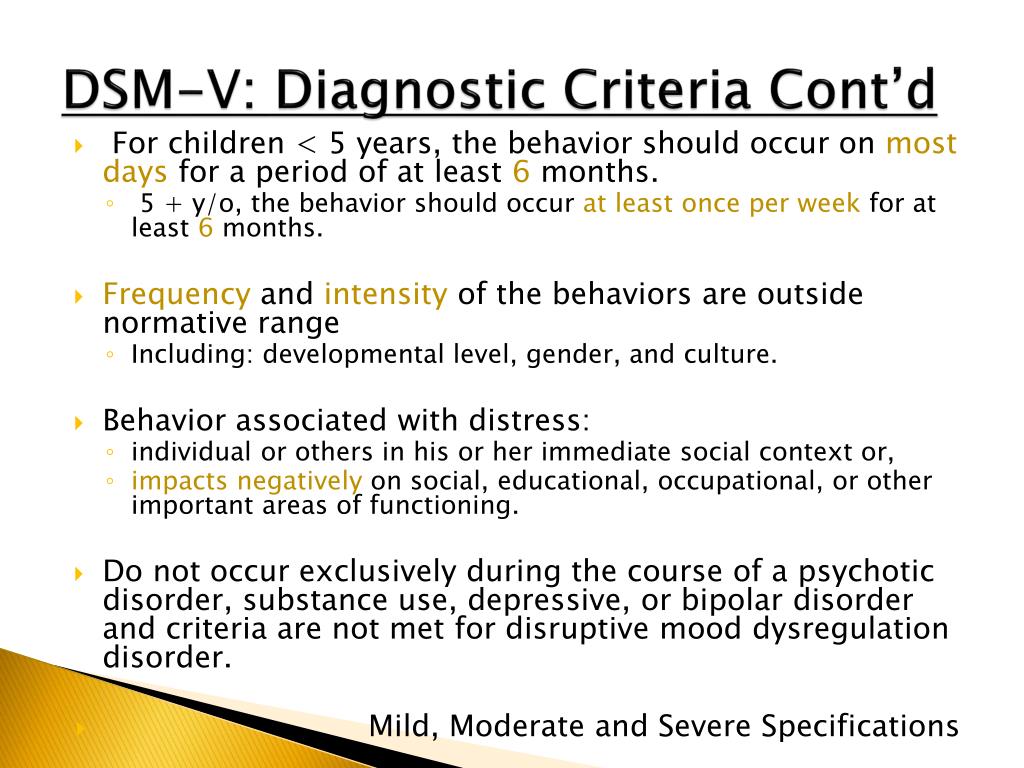

- DSM-5 Changes: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

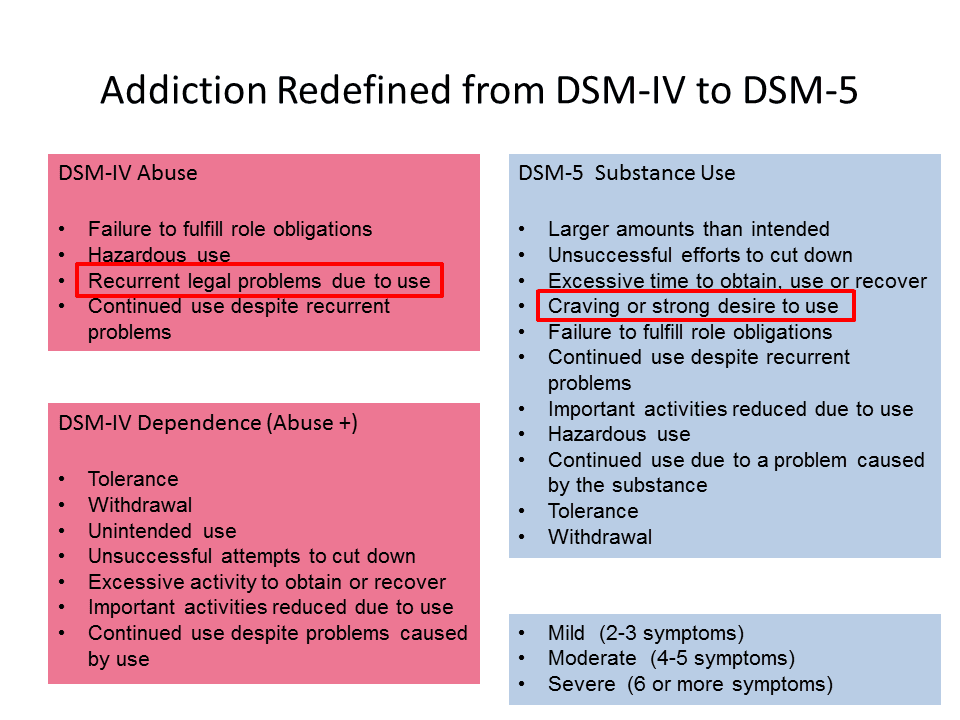

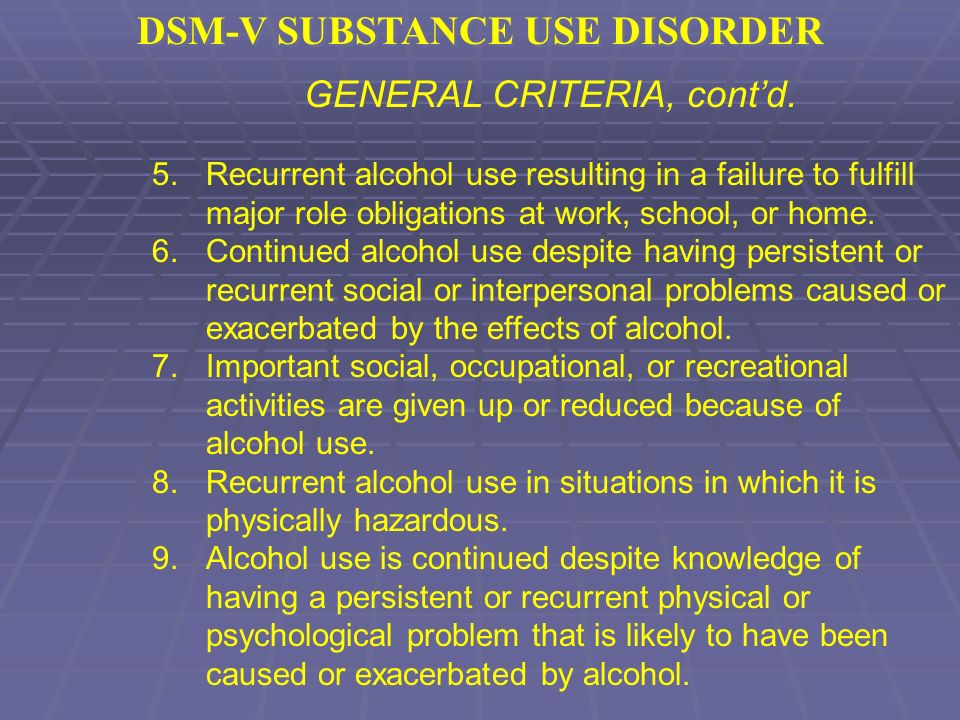

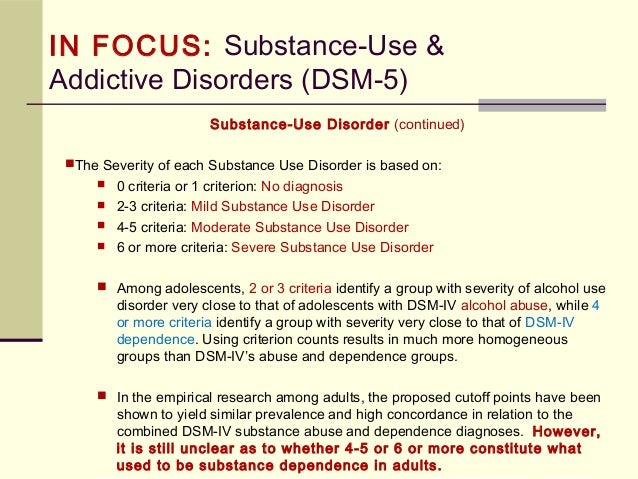

- DSM-5 Changes: Addiction, Substance-Related Disorders & Alcoholism

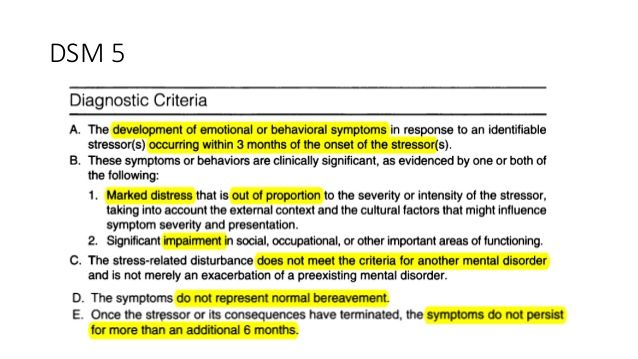

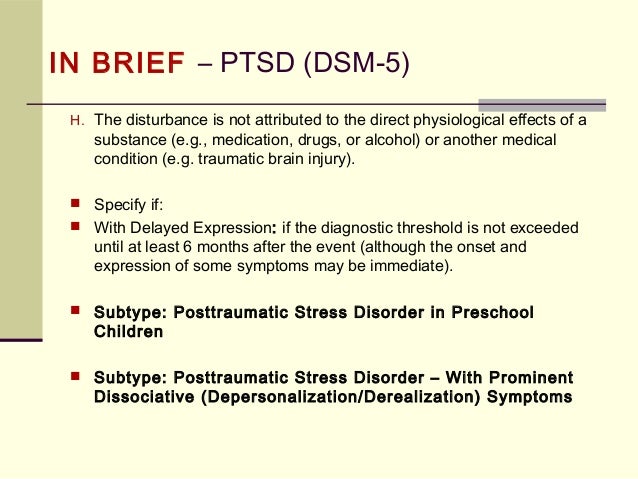

- DSM-5 Changes: PTSD, Trauma & Stress-Related Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Feeding & Eating Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

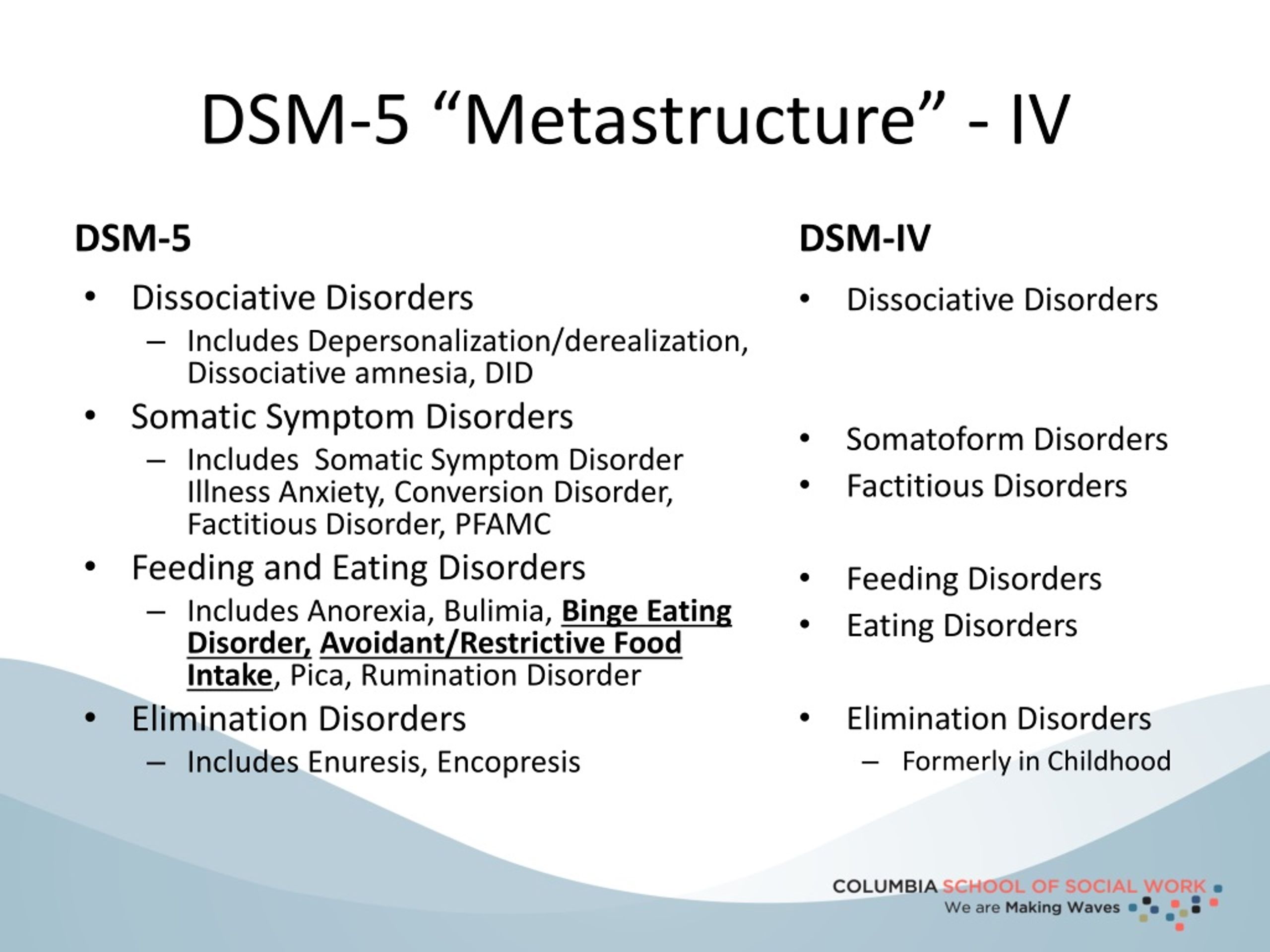

- DSM-5 Changes: Dissociative Disorders

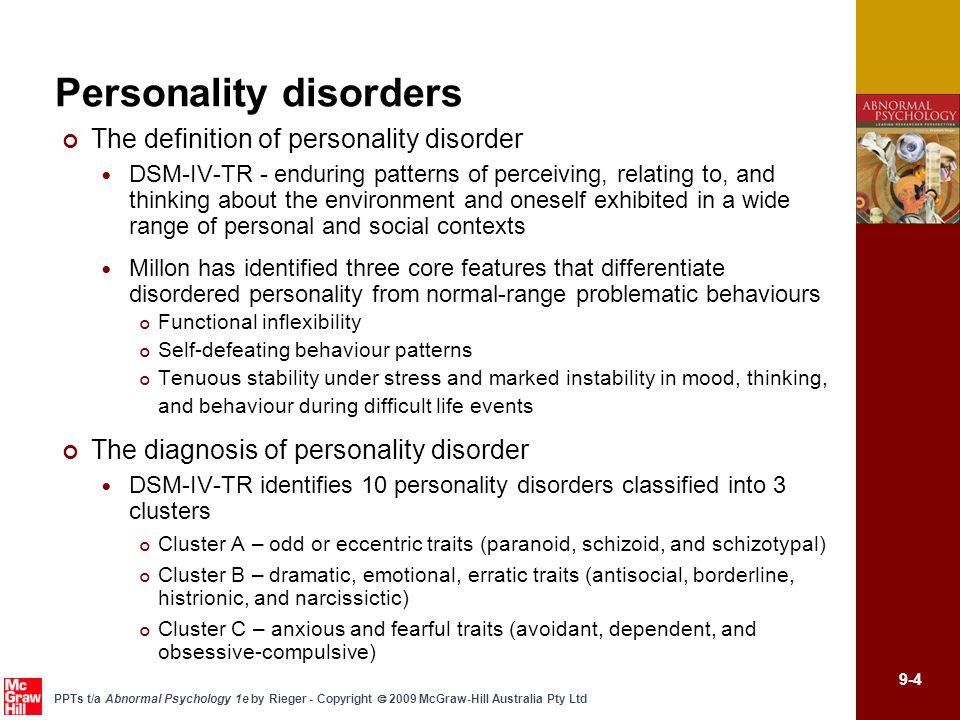

- DSM-5 Changes: Personality Disorders (Axis II)

- DSM-5 Changes: Sleep-Wake Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Neurocognitive Disorders

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) is an edit of the DSM-5 that includes:

- a revision of the original descriptive text in the DSM-5, specifically under these headings:

- recording procedures

- specifiers

- diagnostic features

- associated features

- prevalence

- development and course

- risk and prognostic factors

- culture-related diagnostic issues

- sex and gender-related diagnostic issues

- association with suicidal thoughts or behavior

- functional consequences

- differential diagnosis

- comorbidity

- new and updated references to include more recent literature

- new text regarding the impact of discrimination and racism on mental health diagnoses

- a list of updated diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, clinical modification (ICD-10-CM), including codes related to suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-harm

- one new diagnosis (prolonged grief disorder) in section II, under trauma- and stressor-related disorders

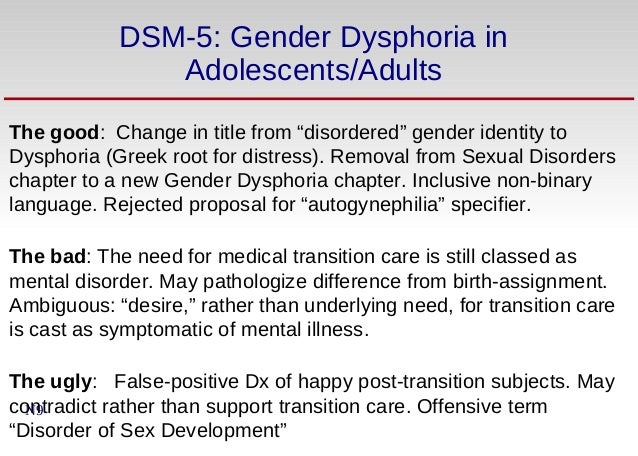

- changes in language in the gender dysphoria chapter, going from “desired gender” to “experienced gender”

- changes in language to refer to gender-related procedures, going from “cross-sex medical procedure” to “gender-affirming medical procedure”

- changes in language in sex-related assignments, going from “natal male” or “natal female” to “individual assigned male at birth” and “individual assigned female at birth”

This is how the DSM-5-TR is indexed:

- DSM-5-TR Classification

- Preface

- Section I: DSM-5-TR Basics

- Introduction

- Use of the Manual

- Cautionary Statement for Forensic Use of DSM-5-TR

- Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes

- Neurodevelopmental Disorders

- Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

- Bipolar and Related Disorders

- Depressive Disorders

- Anxiety Disorders

- Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

- Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

- Dissociative Disorders

- Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders

- Feeding and Eating Disorders

- Elimination Disorders

- Sleep-Wake Disorders

- Sexual Dysfunctions

- Gender Dysphoria

- Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Neurocognitive Disorders

- Personality Disorders

- Paraphilic Disorders

- Other Mental Disorders and Additional Codes

- Medication-Induced Movement Disorders and Other Adverse Effects of Medication

- Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention

- Section III: Emerging Measures and Models

- Assessment Measures

- Culture and Psychiatric Diagnoses

- Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personality Disorders

- Conditions for Further Study

- Appendix

- Alphabetical Listing of DSM-5-TR Diagnoses and Codes (ICD-10-CM)

- Numerical Listing of DSM-5-TR Diagnoses and Codes (ICD-10-CM)

- DSM-5 Advisors and Other Contributors

- Index

More than 200 mental health experts contributed to the DSM-5-TR.

The DSM-5 offers an extensive list of conditions and symptoms that can aid mental health professionals in reaching accurate diagnoses. The latest version is the DSM-5-TR.

The manual has come a long way since its first edition and now provides diagnostic criteria for 193 mental health conditions.

The DSM is a living document that continues to change over time as we learn more about human cognition and behavior.

Diagnosing and Classifying Mental Disorders

Learning Objectives

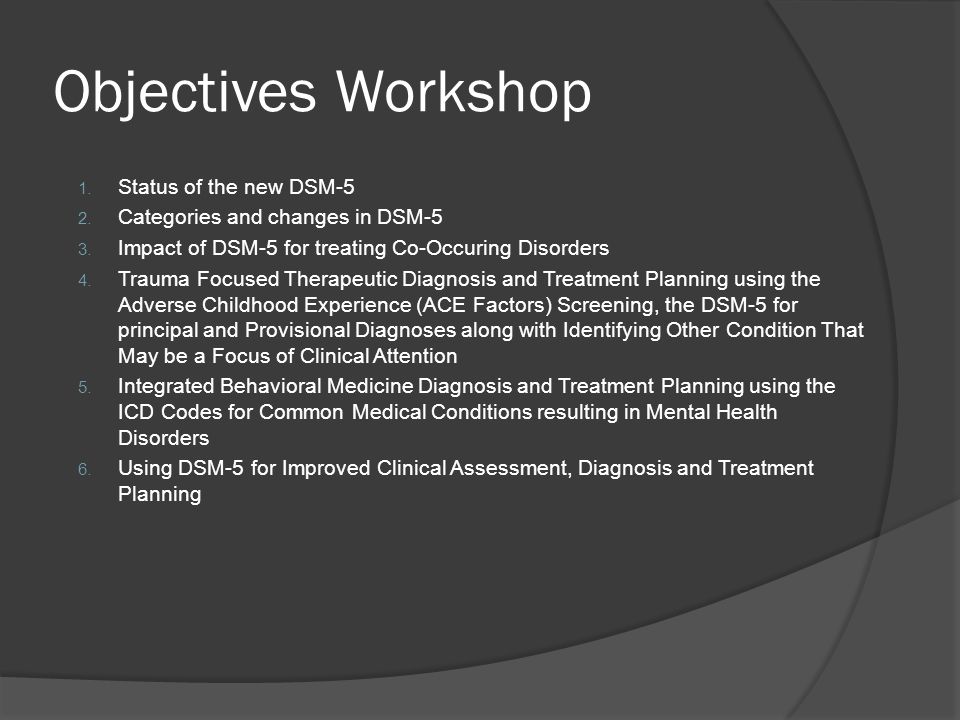

- Describe the basic features of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) and how it is used to classify disorders

- Outline the major disorder categories of the DSM-5

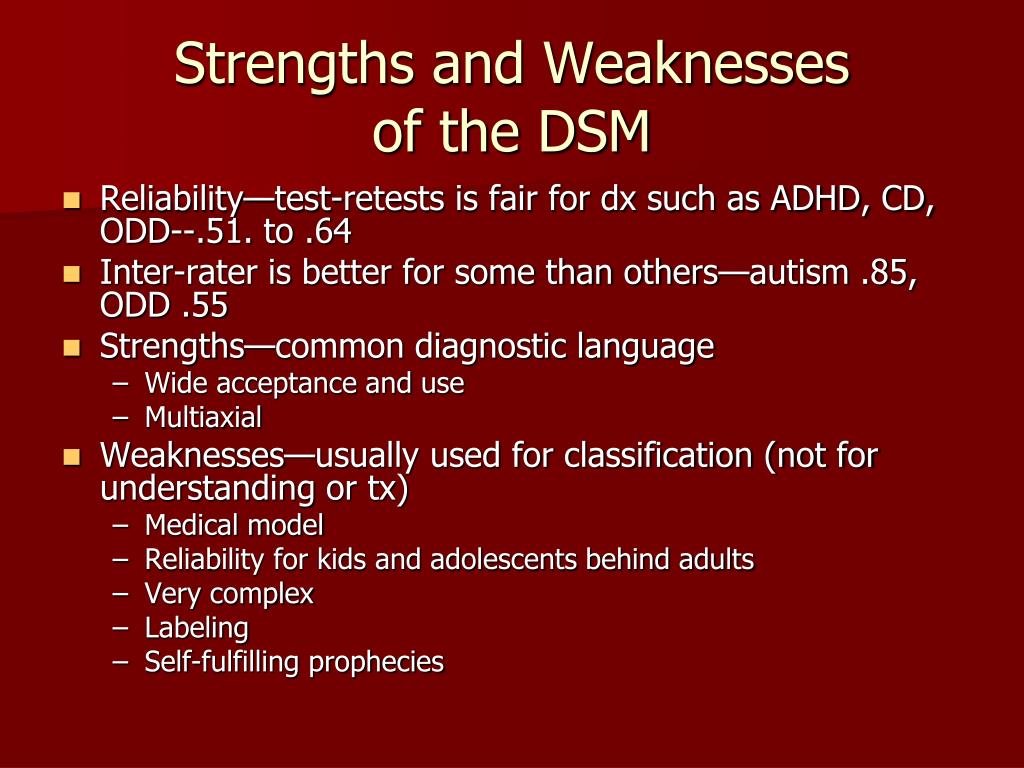

A first step in the study of mental disorders is carefully and systematically discerning significant signs and symptoms. How do mental health professionals ascertain whether or not a person’s inner states and behaviors truly represent a psychological disorder? Arriving at a proper diagnosis—that is, appropriately identifying and labeling a set of defined symptoms—is absolutely crucial. This process enables professionals to use a common language with others in the field and aids in communication about the disorder with the patient, colleagues, and the public. A proper diagnosis is an essential element to guide proper and successful treatment. For these reasons, classification systems that organize psychological disorders systematically are necessary.

This process enables professionals to use a common language with others in the field and aids in communication about the disorder with the patient, colleagues, and the public. A proper diagnosis is an essential element to guide proper and successful treatment. For these reasons, classification systems that organize psychological disorders systematically are necessary.

Although a number of classification systems have been developed over time, the one that is used by most mental health professionals in the United States is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association in 2013. Additions and revisions were made in March 2022, so the most current edition is called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). (Note that the American Psychiatric Association differs from the American Psychological Association; both are abbreviated APA. ) This textbook includes the updates from the DSM-5-TR, though we typically continue to reference the diagnostic manual simply as the DSM-5.

) This textbook includes the updates from the DSM-5-TR, though we typically continue to reference the diagnostic manual simply as the DSM-5.

The first edition of the DSM, published in 1952, classified psychological disorders according to a format developed by the U.S. Army during World War II (Clegg, 2012). In the years since, the DSM has undergone numerous revisions and editions. The DSM-5 includes many categories of disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and dissociative disorders). Each disorder is described in detail, including an overview of the disorder (diagnostic features), specific symptoms required for diagnosis (diagnostic criteria), prevalence information (what percent of the population is thought to be afflicted with the disorder), and risk factors associated with the disorder. Figure 1 shows lifetime prevalence rates—the percentage of people in a population who develop a disorder in their lifetime—of various psychological disorders among U. S. adults. These data were based on a national sample of 9,282 U.S. residents (National Comorbidity Survey, 2007).

S. adults. These data were based on a national sample of 9,282 U.S. residents (National Comorbidity Survey, 2007).

Figure 1. The graph shows the breakdown of psychological disorders, comparing the percentage prevalence among adult males and adult females in the United States. Because the data is from 2007, the categories shown here are from the DSM-4, which has been supplanted by the DSM-5. Most categories remain the same; however, alcohol abuse now falls under a broader alcohol use disorder category.

| DSM Disorder | Total | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Depressive Disorder | 17% | 20% | 13% |

| Alcohol Abuse | 13% | 7% | 20% |

| Specific Phobia | 13% | 16% | 8% |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 12% | 13% | 11% |

| Drug Abuse | 8% | 5% | 12% |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 7% | 10% | 3% |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 6% | 7% | 4% |

| Panic Disorder | 5% | 6% | 3% |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | 3% | 3% | 2% |

| Persistent Depressive Disorder | 3% | 3% | 2% |

More recent data shows that the most prevalent disorders at any given time (not over a lifetime) are anxiety disorders, as shown in the following chart. [1]

[1]

Figure 2. The prevalence of mental and substance use disorders in the United States.

The DSM-5 also provides information about comorbidity; the co-occurrence of two disorders. For example, the DSM-5 mentions that 41% of people with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) also meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (Figure 2). Drug use is highly comorbid with other mental illnesses; six out of 10 people who have a substance use disorder also suffer from another form of mental illness (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2007).

Figure 3. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and major depressive disorder frequently occur in the same person.

Comorbidity

Co-occurrence and comorbidity of psychological disorders are quite common, and some of the most pervasive comorbidities involve substance use disorders that co-occur with psychological disorders. Indeed, some estimates suggest that around a quarter of people who suffer from the most severe cases of mental illness exhibit substance use disorder as well. Conversely, around 10 % of individuals seeking treatment for substance use disorder have serious mental illnesses. Observations such as these have important implications for treatment options that are available. When people with a mental illness are also habitual drug users, their symptoms can be exacerbated and resistant to treatment. Furthermore, it is not always clear whether the symptoms are due to drug use, the mental illness, or a combination of the two. Therefore, it is recommended that behavior is observed in situations in which the individual has ceased using drugs and is no longer experiencing withdrawal from the drug in order to make the most accurate diagnosis (NIDA, 2018).

Conversely, around 10 % of individuals seeking treatment for substance use disorder have serious mental illnesses. Observations such as these have important implications for treatment options that are available. When people with a mental illness are also habitual drug users, their symptoms can be exacerbated and resistant to treatment. Furthermore, it is not always clear whether the symptoms are due to drug use, the mental illness, or a combination of the two. Therefore, it is recommended that behavior is observed in situations in which the individual has ceased using drugs and is no longer experiencing withdrawal from the drug in order to make the most accurate diagnosis (NIDA, 2018).

Obviously, substance use disorders are not the only possible comorbidities. In fact, some of the most common psychological disorders tend to co-occur. For instance, more than half of individuals who have a primary diagnosis of depressive disorder are estimated to exhibit some sort of anxiety disorder. The reverse is also true for those diagnosed with a primary diagnosis of an anxiety disorder. Further, anxiety disorders and major depression have a high rate of comorbidity with several other psychological disorders (Al-Asadi, Klein, & Meyer, 2015).

The reverse is also true for those diagnosed with a primary diagnosis of an anxiety disorder. Further, anxiety disorders and major depression have a high rate of comorbidity with several other psychological disorders (Al-Asadi, Klein, & Meyer, 2015).

The DSM has changed considerably in the half-century since it was originally published. The first two editions of the DSM, for example, listed homosexuality as a disorder; however, in 1973, the APA voted to remove it from the manual (Silverstein, 2009). While the DSM-3 did not list homosexuality as a disorder, it introduced a new diagnosis, ego-dystonic homosexuality, which emphasized homosexual arousal that the patient viewed as interfering with desired heterosexual relationships and causing distress for the individual. This new diagnosis was considered by many as a compromise to appease those who viewed homosexuality as a mental illness. Other professionals questioned how appropriate it was to have a separate diagnosis that described the content of an individual’s distress. In 1986, the diagnosis was removed from the DSM-3-R (Herek, 2012).

In 1986, the diagnosis was removed from the DSM-3-R (Herek, 2012).

WAtch It

This video provides an overview of some of the history related to the development and evolution of the DSM.

You can view the transcript for “We Were Super Wrong About Mental Illness: The DSM’s Origin Story” here (opens in new window).

Additionally, beginning with the DSM-3 in 1980, mental disorders have been described in much greater detail, and the number of diagnosable conditions has grown steadily, as has the size of the manual itself. DSM-1 included 106 diagnoses and was 130 total pages, whereas DSM-3 included more than twice as many diagnoses (265) and was nearly seven times its size (886 total pages) (Mayes & Horowitz, 2005). Although DSM-5 is longer than DSM-4, the volume includes only 237 disorders, a decrease from the 297 disorders that were listed in DSM-4. The DSM-5, includes revisions in the organization and naming of categories and in the diagnostic criteria for various disorders (Regier, Kuhl, & Kupfer, 2012), while emphasizing careful consideration of the importance of gender and cultural difference in the expression of various symptoms (Fisher, 2010). The most recent

Although DSM-5 is longer than DSM-4, the volume includes only 237 disorders, a decrease from the 297 disorders that were listed in DSM-4. The DSM-5, includes revisions in the organization and naming of categories and in the diagnostic criteria for various disorders (Regier, Kuhl, & Kupfer, 2012), while emphasizing careful consideration of the importance of gender and cultural difference in the expression of various symptoms (Fisher, 2010). The most recent

Some believe that establishing new diagnoses might over-pathologize the human condition by turning common human problems into mental illnesses (The Associated Press, 2013). Indeed, the finding that nearly half of all Americans will meet the criteria for a DSM disorder at some point in their life (Kessler et al., 2005) likely fuels much of this skepticism. The DSM-5 is also criticized on the grounds that its diagnostic criteria have been loosened, thereby threatening to “turn our current diagnostic inflation into diagnostic hyperinflation” (Frances, 2012, para. 22). For example, DSM-4 specified that the symptoms of major depressive disorder must not be attributable to normal bereavement (loss of a loved one). The DSM-5, however, has removed this bereavement exclusion, essentially meaning that grief and sadness after a loved one’s death can constitute major depressive disorder.

22). For example, DSM-4 specified that the symptoms of major depressive disorder must not be attributable to normal bereavement (loss of a loved one). The DSM-5, however, has removed this bereavement exclusion, essentially meaning that grief and sadness after a loved one’s death can constitute major depressive disorder.

Try It

Categories in the DSM

The DSM-5 is divided into 22 chapters that include sets of related disorders. This organization is evident in every chapter so that related disorders appear closer to each other, and psychological and biological diseases often relate to each other. However, if an illness that is primarily medical is not specified in DSM-5, clinicians may use the current ICD diagnoses to specify the condition.

Link to Learning

View the DSM-5 Table of Contents here. Note that the overall outline is the same in the DSM-5-TR, though the contents and some of the language have changed slightly. For example, “dysthymia” is no longer used to describe “persistent depressive disorder,” the terminology for “intellectual disability” has been replaced with “intellectual development disorder” and “conversion disorder” is better known as “functional neurological symptom disorder.” A new disorder, prolonged grief disorder, was added to the section on trauma- and stressor-related disorders.

For example, “dysthymia” is no longer used to describe “persistent depressive disorder,” the terminology for “intellectual disability” has been replaced with “intellectual development disorder” and “conversion disorder” is better known as “functional neurological symptom disorder.” A new disorder, prolonged grief disorder, was added to the section on trauma- and stressor-related disorders.

The current organization of the DSM-5 begins with neurodevelopmental disorders and then proceeds through internalizing problems (depression, anxiety, social anxiety, somatic complaints, post-traumatic symptoms, and obsession-compulsion) to externalizing problems (disruptive, impulse-control, conduct disorders and substance use, etc.). [2]

We have organized this course according to the DSM-5 and devote time in each of the modules to discuss the main features of mental disorders from each of the DSM-5 categories. Throughout these modules, you will learn the basic diagnostic criteria, the etiology (causes), epidemiology (prevalence), and treatment options for each category of disorders. In this way, you can gain a basic understanding of each category of mental disorders, including all of the following:

In this way, you can gain a basic understanding of each category of mental disorders, including all of the following:

- neurodevelopmental disorders

- schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders

- bipolar and related disorders

- depressive disorders

- anxiety disorders

- obsessive-compulsive and related disorders

- trauma- and stressor-related disorders

- dissociative disorders

- somatic symptom and related disorders

- feeding and eating disorders

- elimination disorders

- sleep-wake disorders

- sexual dysfunctions

- gender dysphoria

- disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders

- substance-related and addictive disorders

- neurocognitive disorders

- personality disorders

- paraphilic disorders

- Other mental disorders[3]

Overview of the Major Disorder categories

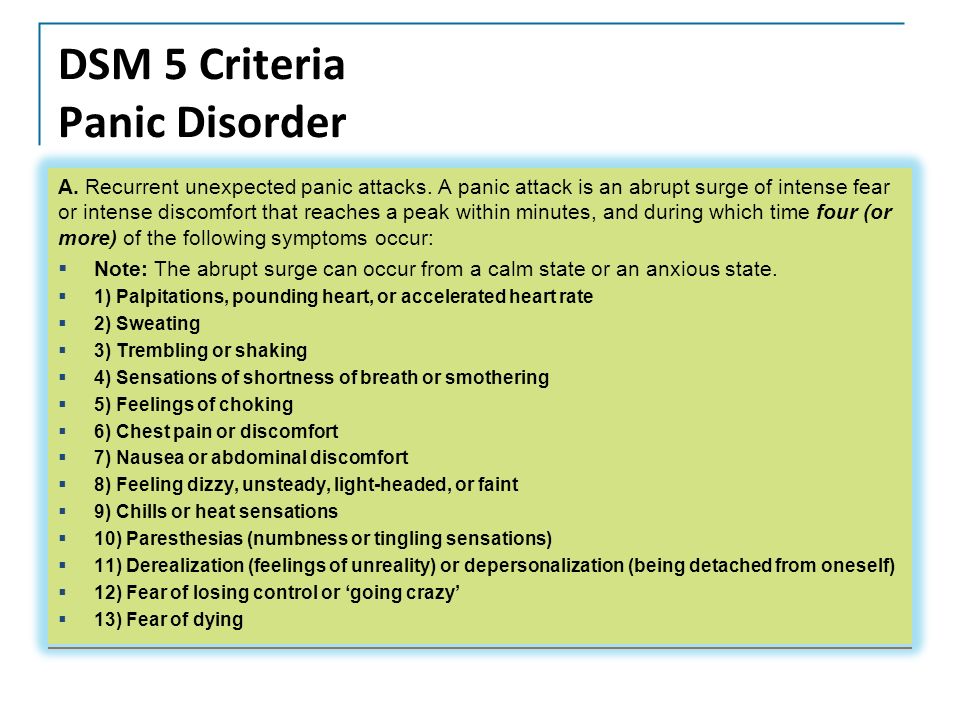

In this course, the major disorders categories begin with anxiety disorders. Any anxiety or fear that interferes with normal functioning may be classified as an anxiety disorder. Commonly recognized categories include specific phobias: a specific unrealistic fear; social anxiety disorder: extreme fear and avoidance of social situations; panic disorder: suddenly overwhelmed by panic even though there is no apparent reason to be frightened; agoraphobia: an intense fear and avoidance of situations in which it might be difficult to escape; and generalized anxiety disorder: a relatively continuous state of tension, apprehension, and dread.

Any anxiety or fear that interferes with normal functioning may be classified as an anxiety disorder. Commonly recognized categories include specific phobias: a specific unrealistic fear; social anxiety disorder: extreme fear and avoidance of social situations; panic disorder: suddenly overwhelmed by panic even though there is no apparent reason to be frightened; agoraphobia: an intense fear and avoidance of situations in which it might be difficult to escape; and generalized anxiety disorder: a relatively continuous state of tension, apprehension, and dread. Another module deals with obsessive-compulsive and related disorders and trauma- and stressor-related disorders. While similar to anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders and posttraumatic stress disorders now have their own distinct categories of classification within the DSM-5 because symptoms of anxiety are not necessarily present. With obsessive-compulsive disorder, a person is obsessed with unwanted, unpleasant thoughts and/or compulsively engages in repetitive behaviors or mental acts, perhaps as a way of coping with the obsessions. Post-traumatic stress disorder is a similar disorder, although classified as a trauma- and stressor-related disorder.

Post-traumatic stress disorder is a similar disorder, although classified as a trauma- and stressor-related disorder.

Link to Learning

Learn more about each of the psychological disorders through the National Institute of Mental Health.

Or for an interesting application of the various mental disorders, take a look at this YouTube playlist showing disorders as they are characterized in popular media. These case studies were developed by students in Dr. Caleb Lack’s psychology class.

Post-traumatic stress disorder is a disorder in which the experience of a traumatic or profoundly stressful event, such as combat, sexual assault, or natural disaster, produces a constellation of symptoms that must last for one month or more. These symptoms include intrusive and distressing memories of the event, flashbacks, avoidance of stimuli or situations that are connected to the event, persistently negative emotional states, feeling detached from others, irritability, proneness toward outbursts, and a tendency to be easily startled.

In another module, we discuss dissociative disorders, somatic symptom, and related disorders. The main characteristics of dissociative disorders are that people become dissociated from their sense of self, resulting in memory and identity disturbances. Dissociative disorders listed in the DSM-5 include dissociative amnesia, depersonalization/derealization disorder, and dissociative identity disorder. A person with dissociative amnesia is unable to recall important personal information, often after a stressful or traumatic experience. Depersonalization/derealization disorder is characterized by recurring episodes of depersonalization (i.e., detachment from or unfamiliarity with the self) and/or derealization (i.e., detachment from or unfamiliarity with the world). A person with dissociative identity disorder exhibits two or more well-defined and distinct personalities or identities, as well as memory gaps for the time during which another identity was present. Dissociative identity disorder has generated controversy, mainly because some believe its symptoms can be faked by patients if presenting its symptoms somehow benefits the patient in avoiding negative consequences or taking responsibility for one’s actions. The diagnostic rates of this disorder have increased dramatically following its portrayal in popular culture. However, many people legitimately suffer over the course of a lifetime with this disorder.

The diagnostic rates of this disorder have increased dramatically following its portrayal in popular culture. However, many people legitimately suffer over the course of a lifetime with this disorder.

Somatic symptom disorders were previously known as “somataform disorders.” These include somatic symptom disorder, illness anxiety disorder, functional neurological symptom disorder (conversion disorder), and fictitious disorder. You will read about the various symptoms, epidemiology, how individuals present with these problems, and a brief overview of possible causes. These disorders relate to a person experiencing physical ailments that are not fully explained by a medical condition.

Mood disorders are discussed in another module. A mood disorder involving unusually intense and sustained sadness, melancholia, or despair is known as major depressive disorder. Milder but still prolonged depression can be diagnosed as persistent depressive disorder. Bipolar disorder is characterized by mood states that vacillate between sadness and euphoria; a diagnosis of bipolar disorder requires experiencing at least one manic episode, which is defined as a period of extreme euphoria, irritability, and increased activity. Mood disorders appear to have a genetic component, with genetic factors playing a more prominent role in bipolar disorder than in depression. Both biological and psychological factors are important in the development of depression. People who suffer from mental health problems, especially mood disorders, are at heightened risk for suicide.

Bipolar disorder is characterized by mood states that vacillate between sadness and euphoria; a diagnosis of bipolar disorder requires experiencing at least one manic episode, which is defined as a period of extreme euphoria, irritability, and increased activity. Mood disorders appear to have a genetic component, with genetic factors playing a more prominent role in bipolar disorder than in depression. Both biological and psychological factors are important in the development of depression. People who suffer from mental health problems, especially mood disorders, are at heightened risk for suicide.

Next, we discuss feeding and eating disorders. Disordered eating can have significant health consequences, and eating disorders are a major health concern. Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by the maintenance of a bodyweight well below average through starvation and/or excessive exercise. Individuals suffering from anorexia nervosa often have a distorted body image, referenced in literature as a type of body dysmorphia, meaning that they view themselves as overweight even though they are not. People suffering from bulimia nervosa engage in binge eating behavior that is followed by an attempt to compensate for a large amount of consumed food. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder is an eating or feeding disturbance associated with an apparent lack of interest in eating or food. Pica is a disorder characterized by an appetite for substances that are largely non-nutritive, such as ice, soap, hair, paper, metal, soil, stones, glass, or chalk.

People suffering from bulimia nervosa engage in binge eating behavior that is followed by an attempt to compensate for a large amount of consumed food. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder is an eating or feeding disturbance associated with an apparent lack of interest in eating or food. Pica is a disorder characterized by an appetite for substances that are largely non-nutritive, such as ice, soap, hair, paper, metal, soil, stones, glass, or chalk.

Many people experience disturbances in their sleep at some point in their lives. Sleep-wake disorders involve problems with the quality, timing, and amount of sleep, which result in daytime distress and impairment in functioning. Sleep-wake disorders often occur along with medical conditions or other mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, or cognitive disorders.

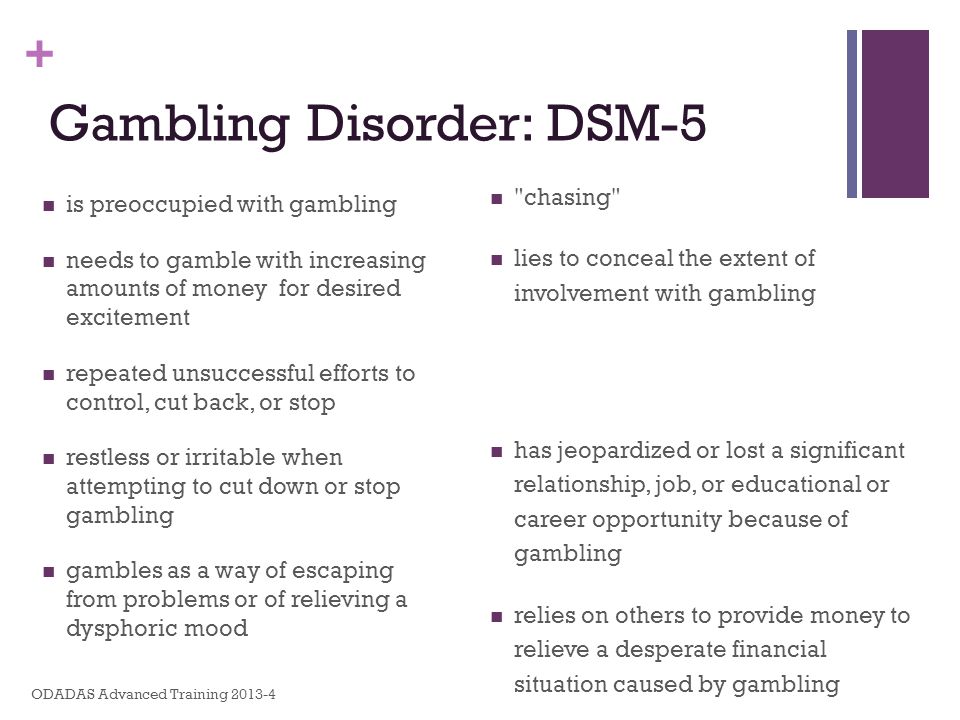

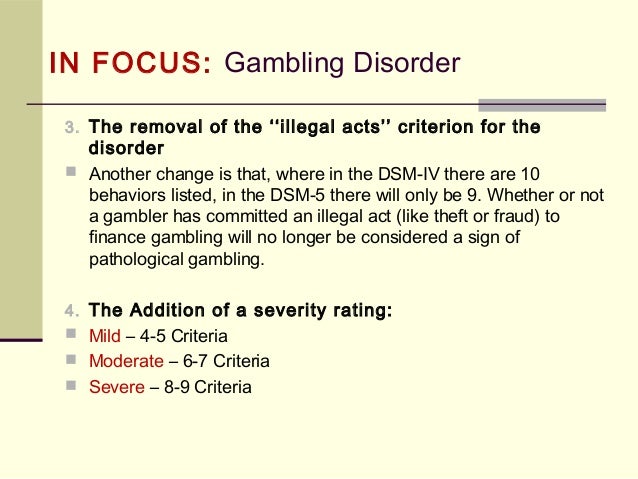

Substance–related disorders are discussed in a separate module. They result when a craving for, the development of, a tolerance to, and difficulties in controlling the use of a particular substance or a combination of different substances, as well as withdrawal syndromes when a person ceases to use the substance(s). Other addictive disorders also include gambling disorder and other behavioral addictions.

Other addictive disorders also include gambling disorder and other behavioral addictions.

Next, we cover the topics of gender dysphoria, paraphilic disorders, and sexual dysfunctions. Today more than ever before, mental health professionals are seeing patients seeking treatment in response to dissatisfaction with their sexual functioning. Such dissatisfaction most commonly stems from a sexual dysfunction, but may also be the result of a sexual deviation. Sexual dysfunction disorders include sexual desire disorders, arousal disorders, orgasm disorders, and pain disorders. From a clinical perspective, there has been some effort to define sexual deviation under the umbrella of sexual paraphilias. Dissatisfaction can also stem from gender dysphoria, or the distress a person feels due to a mismatch between their gender identity and their sex assigned at birth.

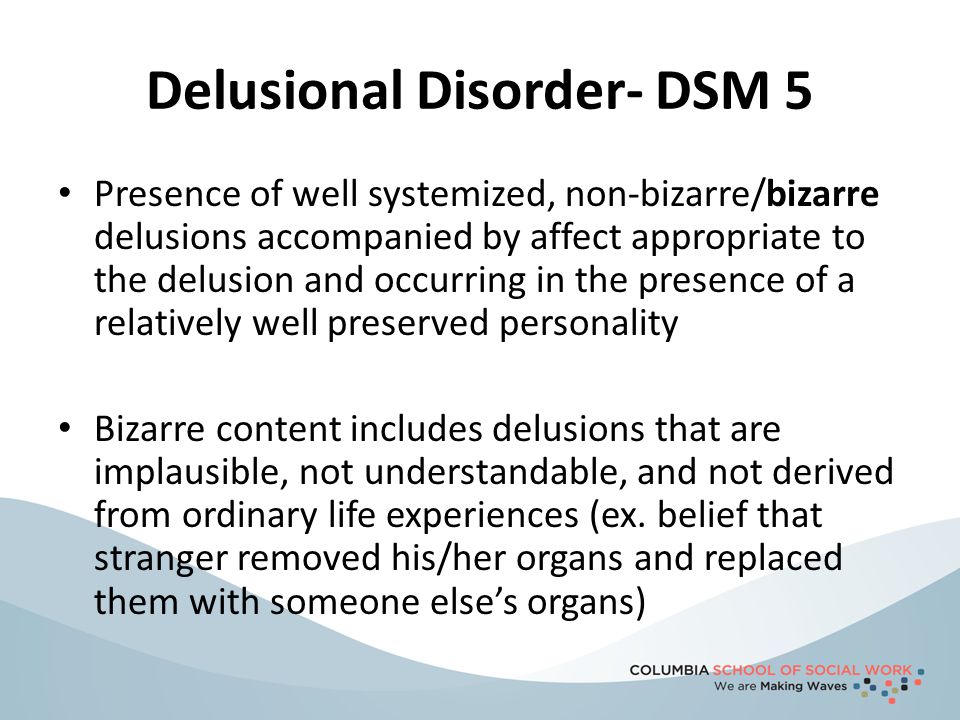

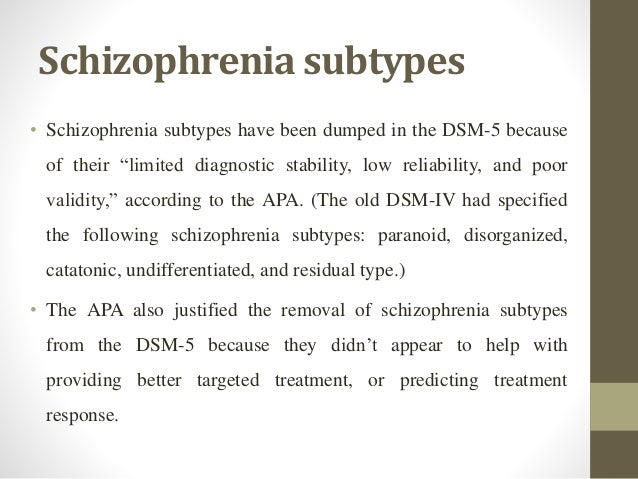

The DSM-5 classifies psychotic disorders that involve psychosis, or a break in reality, like in schizophrenia, delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, substance/medication-induced psychotic disorder, and psychotic disorder due to another medical condition. The most common psychotic disorder in this domain is schizophrenia, which is a severe disorder characterized by delusions and hallucinations, often causing a breakdown in one’s ability to function in life.

The most common psychotic disorder in this domain is schizophrenia, which is a severe disorder characterized by delusions and hallucinations, often causing a breakdown in one’s ability to function in life.

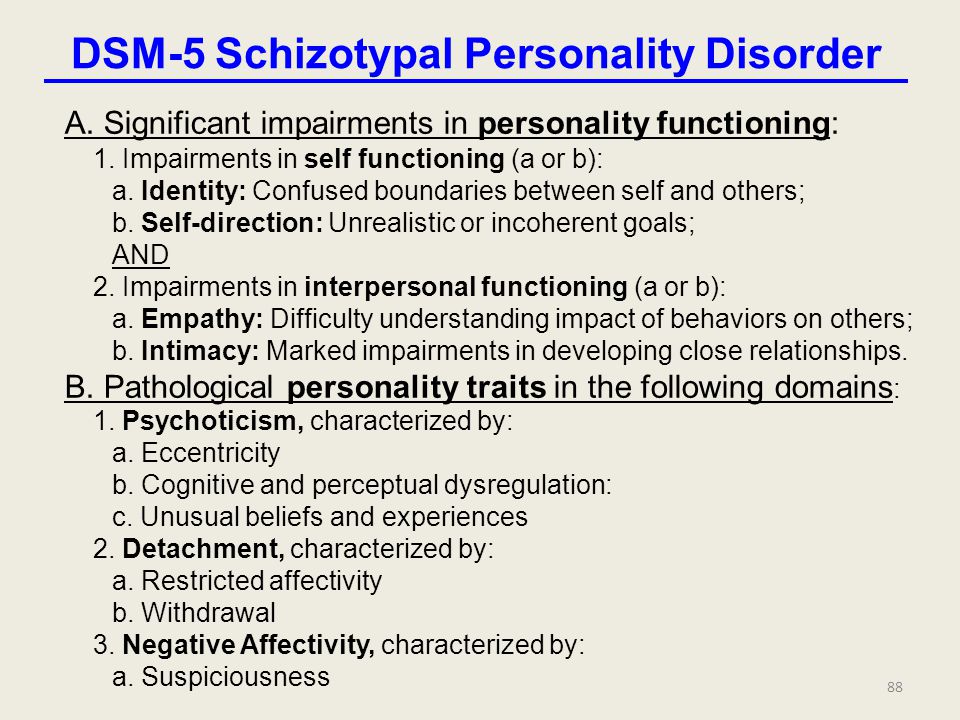

The DSM-5 recognizes 10 personality disorders, organized into three clusters. The disorders in Cluster A include those characterized by a personality style that is odd and eccentric. These include paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders. Cluster B includes personality disorders characterized chiefly by a personality style that is impulsive, dramatic, highly emotional, and erratic (antisocial, histrionic, narcissistic, and borderline), and those in Cluster C are characterized by a nervous and fearful personality style (avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive).

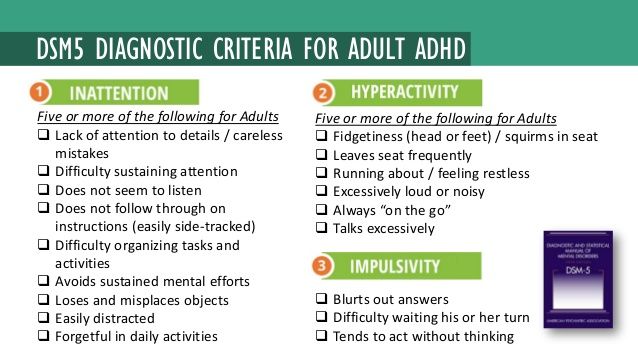

Neurodevelopmental disorders are covered in another module, along with elimination disorders and disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders. The neurodevelopmental disorders are a group of disorders that are typically diagnosed during childhood and are characterized by developmental deficits in personal, social, academic, and intellectual realms; these disorders include attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder. The major features of autism spectrum disorder include deficits in social interaction and communication and repetitive movements or interests. ADHD is characterized by a pervasive pattern of inattention and/or hyperactive and impulsive behavior that interferes with normal functioning. Genetic and neurobiological factors contribute to the development of ADHD, which can persist well into adulthood and is often associated with poor, long-term outcomes.

The neurodevelopmental disorders are a group of disorders that are typically diagnosed during childhood and are characterized by developmental deficits in personal, social, academic, and intellectual realms; these disorders include attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder. The major features of autism spectrum disorder include deficits in social interaction and communication and repetitive movements or interests. ADHD is characterized by a pervasive pattern of inattention and/or hyperactive and impulsive behavior that interferes with normal functioning. Genetic and neurobiological factors contribute to the development of ADHD, which can persist well into adulthood and is often associated with poor, long-term outcomes.

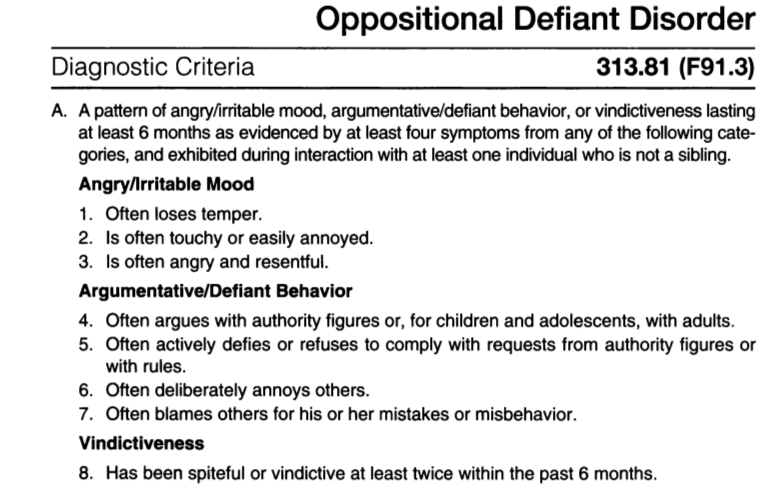

Disruptive, impulse–control, and conduct disorders refer to a group of disorders that include oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, kleptomania, and pyromania. These disorders can cause people to behave angrily or aggressively toward people or property.

These disorders can cause people to behave angrily or aggressively toward people or property.

Finally, we learn about neurocognitive disorders—disorders that describe decreased mental function due to a medical disease other than a psychiatric illness. It is often used synonymously (but incorrectly) with dementia. Although Alzheimer’s disease accounts for the majority of cases of neurocognitive disorders, several other conditions can similarly affect memory, thinking and reasoning, and the motor system. In addition to Alzheimer’s, these conditions include frontotemporal degeneration, Huntington’s disease, Lewy body disease, traumatic brain injury (TBI), Parkinson’s disease, prion disease, and dementia/neurocognitive issues due to HIV infection.

Try It

Glossary

comorbidity: co-occurrence of two disorders in the same individual

diagnosis: determination of which disorder a set of symptoms represents

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5): authoritative index of mental disorders and the criteria for their diagnosis; published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA)

externalizing problems: problems related to disruptive behavior that cause conflicts in relationships with others

internalizing problems: problems that involve emotional alterations of anxiety disorders and depression

- Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2018) - "Mental Health".

Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health' [Online Resource] ↵

Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health' [Online Resource] ↵ - Salavera, Carlos, Usán, Pablo, & Teruel, Pilar. (2019). The relationship of internalizing problems with emotional intelligence and social skills in secondary education students: gender differences. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 32, 4. Epub February 18, 2019. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s41155-018-0115-y ↵

- Regier, D. A., Kuhl, E. A., & Kupfer, D. J. (2013). The DSM-5: Classification and criteria changes. World psychiatry: official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 12(2), 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20050 ↵

Clarification of ASD diagnostic criteria in DSM-5 TR

Two changes to the criteria for diagnosing autism published in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR), published by the American Psychiatric Association . Small changes will add clarity and nuance to the definition of autism in the help text, experts say, but they are unlikely to change how the diagnosis is made.

Small changes will add clarity and nuance to the definition of autism in the help text, experts say, but they are unlikely to change how the diagnosis is made.

“I'm glad to hear that major changes to the definition of autism are not being considered at this time,” says Laura Carpenter, professor of pediatrics and psychiatry at the Medical University of South Carolina at Charleston. “Major changes like this can take years to make, so they should only be considered when absolutely necessary.”

The 2013 DSM-5 edition states that the diagnosis of autism corresponds to “permanent impairment of social interactions and social integration in various situations, which manifests itself in the following”: violations of social-emotional reciprocity, non-verbal communicative behavior that a person needs for social interactions, and to develop, maintain and understand relationships.

The first revision of the text in the new DSM-5-TR adds two words to this description of “what manifests all of those below. "

"This addition may help dispel the "serious ambiguity" that has left many clinicians confused as to whether a diagnosis requires only some or all of these deficiencies at once," says Michael Furst, professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, which serves as an editorial and coding consultant for DSM-5

The second change replaces one word describing “specifiers (1)” that may accompany a diagnosis of autism. clinicians to clarify “whether this person’s autism is associated with another neurodevelopmental (2), mental or behavioral disorder ”, the DSM-5-TR version reads: “associated with neurodevelopmental, mental or behavioral problem ”. It still directs clinicians to use additional diagnostic codes when appropriate, but no longer requires these specifiers to be diagnostic conditions.

According to Furst, this second change now allows clinicians to specify co-occurring problems, such as self-harm, that do not "elevate to the level of a disorder. "

"

"The first draft more accurately reflects what the DSM-5 working group has always envisioned," Furst says. “People are sending us emails saying, ‘I don’t understand how to interpret this,’” he notes. “And those are just people who bothered to write to us, so God knows how it actually affected” diagnosis and what are the numbers of the spread of this phenomenon.

"No data, but the impact was probably minimal," says Katherine Lord, Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry and Education at the University of California, Los Angeles. three criteria, even if it was initially unclear.” Lord is a member of the DSM-5 Committee on Developmental Disabilities, but she did not work on this revision of the text.0006

“It's more like a formality,” agrees Carpenter. "I've never heard anyone stick to the definition of 'any' of these criteria."

"The impact of change will depend heavily on the competence and experience of the clinicians who interpret it," says David Skuse, professor of behavioral science and neuroscience. University College London in the UK. “People with a lot of medical experience and confidence are unlikely to change their clinical practice.”

University College London in the UK. “People with a lot of medical experience and confidence are unlikely to change their clinical practice.”

Lord and Skewes think the second change, to expand the notion of specifiers, is obviously useful.

Skewes wrote the main text for the criteria for autism in the International Classification of Diseases, Revision 11 (ICD-11 - World Health Organization guidelines), which provides codes for health conditions and causes of death. The ICD-10, the previous version, did not allow health care providers to list comorbid diagnoses such as ADHD along with autism, as did the DSM-IV (the previous version of the DSM). The lifting of this ban was one of the smartest changes in DSM-5 compared to DSM-IV, he said.

“This takes us a bit beyond precision medicine (i.e. genetics) to the importance of many other things that affect quality of life,” Lord adds. - And soon we will be able to achieve success in this!

Some studies have shown that due to changes in the DSM-5 criteria from DSM-IV criteria, some autistic people no longer qualify for this diagnosis. Fred Volkmar, professor of child psychiatry, pediatrics, and psychology at the Yale Children's Study Center, who led one study on the subject in 2012, continues to argue that these criteria are too narrow to capture the full range of conditions.

Fred Volkmar, professor of child psychiatry, pediatrics, and psychology at the Yale Children's Study Center, who led one study on the subject in 2012, continues to argue that these criteria are too narrow to capture the full range of conditions.

According to him, these new amendments do not address such issues: “The main idea remains more or less unchanged. These changes are very minor."

(1) Details to which special attention should be paid, explanations, clarifications.

(2) Associated with the development of the nervous system and mental functions.

The above material is a translation of the text "DSM-5 revision tweaks autism entry for clarity".

Translator: Lev Alyabiev.

What role do the DSM-5 criteria for substance use and addictive disorders play in the diagnosis of addiction? | Addiction & Recovery articles | Emotional & Mental Health center

Although the DSM-5 lists numerous different addictions, their diagnostic criteria are very similar - because addictions affect a person's life and behavior in the same way, regardless of substance or behavior. What should you know?

What should you know?

Addiction is an insidious disease that can start with a number of options, but then take over the brain - and depending on what you are addicted to, and sometimes the body. Once you're in the clutches of an addiction, the all-encompassing call for more drugs, alcohol, gambling, shopping, food, sex, or whatever you're used to becomes almost impossible to refuse.

The American Society for Addiction Medicine describes addiction as a chronic and often progressive disorder that may include periods of remission and relapse. We now know that becoming an addict is not a moral failing or a permanent choice. Once you are addicted, your addiction robs you of much of your control.

Addiction can be a serious disease, but it is indeed treatable. This treatment can take many forms, but it starts with the decision that you are ready to go into remission. If you're an addict, you've likely tried - and ultimately failed - to stop using the substance or stopped participating in the behavior multiple times and realized that professional help would be needed to break your chains.

This help starts with a diagnosis, and in the US, clinicians will use the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition - DSM-5 for short - to determine if you have an addiction and how severe it is.

What do drug addicts and their loved ones need to know about the diagnostic criteria for DSM-5 addiction?

The DSM-5 is an incredibly long document filled with diagnostic criteria for many different mental and cognitive disorders, from depression to autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia to narcissistic personality disorder. Addiction is described in the chapter on Substances and Dependence Disorders. This chapter covers many different addictions, including alcohol, tobacco, opioids, sedatives, sleeping pills, cannabis, and even caffeine. It also includes gambling, but has a strong addiction to psychoactive substances and is rather devoid of behavioral addictions.

DSM-5 includes those passions that were backed by hard science at the time of publication. Not all addictions described in the medical literature, such as addictions to food, shopping, sex, gaming, and Internet use, are official diagnostic categories in the DSM-5. If you are (as you think) addicted to something that is not covered in this document, you can still get the help you need. If something is not in the DSM-5, it does not mean that it does not exist.

Not all addictions described in the medical literature, such as addictions to food, shopping, sex, gaming, and Internet use, are official diagnostic categories in the DSM-5. If you are (as you think) addicted to something that is not covered in this document, you can still get the help you need. If something is not in the DSM-5, it does not mean that it does not exist.

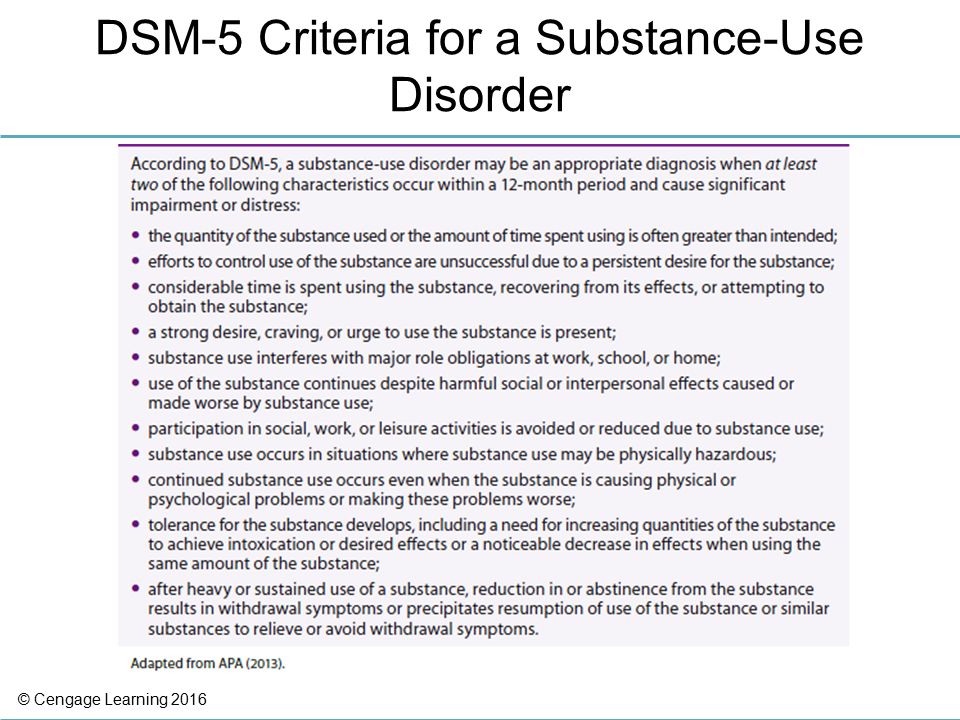

Look at the Diagnostic Criteria for Addiction

When you look at the diagnostic criteria for all the different addictions included in the DSM-5, you will begin to realize that they are all pretty similar - no matter what substance or behavior is being discussed in the document. We will make these diagnostic criteria more general so that you can get a general picture of the types of symptoms that signify addiction. Since the DSM-5 mainly deals with substance addiction, we will refer to "substance" - but very similar symptoms will be seen among people suffering from behavioral addictions.

First of all, the DSM-5 will require that at least two of the symptoms be present for one year resulting in significant distress or aggravation:

- The person uses more of the substance, or longer, than they intended.

- The person wants to reduce or stop the use of the substance, but is unsuccessful in these efforts.

- A person spends a lot of time using the substance, receiving it or recovering from it.

- The person experiences a strong craving for the substance.

- The use of a substance causes a person to fail to fulfill their important responsibilities in life.

- Substance use causes or exacerbates interpersonal problems, but does not cause the person to contract or stop.

- A person misses important events due to substance abuse.

- A person uses the substance in situations where it is physically dangerous (for example, while driving or operating heavy machinery).

Then there is tolerance - the person no longer achieves the same effect from using the same amount (or, in the case of a behavioral addiction, for example, from gambling with the same amount of money), or starts using more to return to the same effect . Finally, there is withdrawal symptoms - a person experiences withdrawal symptoms associated with the substance in question when they try to stop using the substance.

Finally, there is withdrawal symptoms - a person experiences withdrawal symptoms associated with the substance in question when they try to stop using the substance.

You also need to know that:

- When someone is diagnosed with an addiction, the doctor will indicate how serious it is. The presence of two or three of these symptoms typically indicates a milder addiction, a score of four or five for a moderately severe addiction, and a severe addiction is marked by six or more symptoms.

- If you have used within the last year but not within the last three months, you may be diagnosed with early remission. If you have previously met the diagnostic criteria for any addiction but have been abstaining from use for more than a year, you are in stable remission.

While diagnostic criteria form the basis of diagnosis, anyone an addict turns to for help doesn't just sneak down the list asking if they check the boxes. More “handy” screening tools and questionnaires can be used.