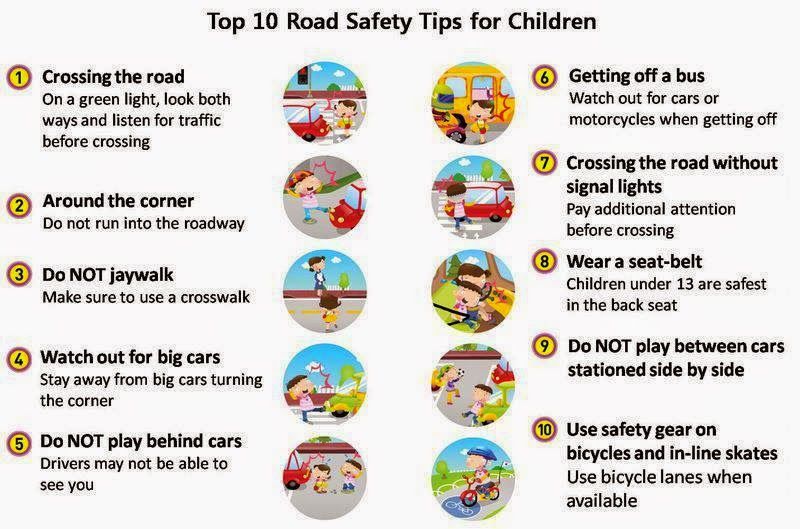

Attention getting behavior in children

Child Therapy Nashville | Understanding Your Child's Negative Behaviors

Kids’ Secret Messages: Understanding Your Child’s Negative Behaviors

When a child displays challenging behaviors, it can naturally be very overwhelming and frustrating for parents. Yet, by identifying and understanding the causes of the negative behaviors, parents can take action to resolve them or to prevent them from happening in the first place.

Why A Child Might Act OutThere are several reasons why a child may act out, the first of which is to get their parents’ attention. Many parents are overworked, plugged in 24/7 and struggle to find time to really sit down with their children and play. As a result, the child can seek out attention in negative ways. For example, when a child asks a parent to do something that the child is capable of doing independently, this is attention-seeking behavior. If the child knows how to get dressed without assistance and asks for help putting on clothes, this is attention-seeking behavior.

If a parent is on the phone for three minutes and the child is interrupting with questions for the entire time, this is attention-seeking behavior.

When a child displays attention-seeking behavior, parents feel annoyed. The best way to resolve this issue is to proactively give undivided attention to the child for a predictable amount of time at a predictable time. For example, parents may want to dedicate 10-15 minutes per day after school and before dinner to playing with their child. It can be a board game, hitting a ball, taking a walk or whatever else the child wants to play (within reason). For most families, taking this step will greatly increase the child’s sense of significance and reduce negative attention-seeking behaviors.

Control-Seeking BehaviorIf attention-seeking behavior doesn’t help a child get more attention from their parents, the child may begin to display control-seeking behavior. When a child lacks a sense of personal power or significance, they will seek out control over their environment. Control-seeking behavior may include trying to dictate how everyone in the family behaves or engaging in a power struggle. Contrasted with attention-seeking behavior which will stop when parents’ give the child attention, controlling behavior doesn’t stop when parents tell their child to stop; in fact, these situations tend to escalate.

When a child lacks a sense of personal power or significance, they will seek out control over their environment. Control-seeking behavior may include trying to dictate how everyone in the family behaves or engaging in a power struggle. Contrasted with attention-seeking behavior which will stop when parents’ give the child attention, controlling behavior doesn’t stop when parents tell their child to stop; in fact, these situations tend to escalate.

When control-seeking behavior is displayed, parents often feel angry and resentful. The focus can become about winning instead of resolving the underlying issue. The best way to address this type of negative behavior is to create an environment with choices so the child feels they can control their environment. Of course, parents set up the choices, preferably limiting the number of choices to two. If the child is given two choices and doesn’t make a choice, parents can make it clear that these are the only two choices and give them one more chance to make a choice. Ultimately, if the child doesn’t respond, the parents can make the choice on the child’s behalf.

Ultimately, if the child doesn’t respond, the parents can make the choice on the child’s behalf.

If parents know for sure that their child will not like either option, it’s best not to use this approach. It’s important to set up the child to succeed and feel in control by offering choices only when parents are confident that the child will select an option. If they aren’t confident, it’s best that the parents sit down with the child to discuss options, by saying, “I need your help in deciding what we should do next. This is what I’m thinking…what are your ideas?” Then, parents are encouraged to select a couple of options that suit them from the child’s ideas (within reason) and have the child make a choice.

Non-negotiable decisions include basics like going to sleep on time, attending school, brushing teeth, etc. A child may not be able to choose their bed time, but they may be able to decide what they want to do 10 minutes prior to going to sleep. A child may not be able to decide to skip school, but they can decide what they want to wear.

Typically, the more opportunity for decision-making by the child, the less controlling behaviors will be displayed. The child will have an increased sense of personal power and an increased confidence in being able to deal with things.

Anxiety & Control In ChildrenHowever, sometimes the child is displaying controlling behaviors for other reasons, such as if they are struggling with anxiety. When a child suffers from anxiety, they feel safe when things are predictable and they feel like they have control over the things around them. Offering choices is still a helpful approach for a child with anxiety.

When attention-seeking and control-seeking behaviors don’t work for children, they lack a feeling of personal power, significance and belonging. This often results in hurtful, revenge-seeking behavior. Children may feel like “I can’t control you, but I can hurt you.” An example of this is doing something that they know will hurt your feelings. For example, when a child tells a teacher that their parents abuse them when it’s not true – or when a child breaks or steals a treasured object. They do this only because they know it will hurt you.

For example, when a child tells a teacher that their parents abuse them when it’s not true – or when a child breaks or steals a treasured object. They do this only because they know it will hurt you.

Revenge-seeking behaviors often make parents feel confused. Why, after all, would anybody, especially your child purposely do something to hurt you? To address this, parents need to think about how they may have overlooked the two previous issues (lack of attention and lack of control) and try to fix them.

These more extreme types of negative behaviors are a clear sign that there could be some larger mental health issues, such as an attachment disorder or antisocial personality disorder, which is at the extreme end of the spectrum and is caused by individuals who have had significant trauma and issues with attachment for a long time.

Why Parents Do What They Do

Some parents are overprotective, which can lead to a child feeling like their parent doesn’t think they are capable. Other parents give children much less help and guidance, leading the children to feel like they aren’t important to their parents. So much of how parents raise their children is the result of what they experienced as a child. Did they feel ignored? They are more likely to be overprotective. Were they heavily monitored, they may want to give their child excessive freedom. Trying to achieve a perfect balance in parenting is very difficult.

Other parents give children much less help and guidance, leading the children to feel like they aren’t important to their parents. So much of how parents raise their children is the result of what they experienced as a child. Did they feel ignored? They are more likely to be overprotective. Were they heavily monitored, they may want to give their child excessive freedom. Trying to achieve a perfect balance in parenting is very difficult.

Overall, child therapy and family therapy can be beneficial for parents wanting to resolve any of these three types of negative behaviors. Children are very dependent on their parents and are deeply impacted by how a parent intentionally or unintentionally makes them feel. If you or someone you know would like support with finding a better balance, feel free to reach out to schedule an appointment at [email protected].

Until next time,

Olesya

Olesya Leskel, LPC, MHSP

Licensed Psychotherapist

child therapy, child's behaviors, negative behaviors

First Name

Zip Code

Email address:

Recommended Posts

The Most Important Lessons Learned In Child Therapy

7 Signs It May Be Time To See A Child Therapist

Nashville Psych Welcomes New Therapists, Now Offers Child Therapy

Do’s & Don’ts of Attention-Seeking Behavior

Even though she was only three years old, Mallory knew precisely how to get attention from her parents. When she wanted a cookie before dinner, she’d whine and hang on to her father’s pant leg as he cooked. She’d continue until her dad caved in and got her the cookie. Of course, by that point, he was willing to do anything to make her stop.

When she wanted a cookie before dinner, she’d whine and hang on to her father’s pant leg as he cooked. She’d continue until her dad caved in and got her the cookie. Of course, by that point, he was willing to do anything to make her stop.

When she didn’t want to go to bed, she’d run around the house as her parents chased her. Eventually, they’d give up and let her stay up an hour later.

And when Mallory wanted to watch a video, and her parents told her no, she’d scream until she got her way.

Why do young children seek attention in ways that can be so annoying? And why do we, as parents, give in so often?

There are many reasons kids seek attention: they’re bored, tired, hungry, or in need of quality time with their parents. But the reasons your child acts this way aren’t as important as learning how to respond when they do.

Keep in mind that such attention-seeking behavior is normal. Children in the 3- to 7-year-old age range are simply not able to distinguish between needs and wants. And they often don’t know how to articulate themselves without being annoying. It’s a developmental problem. So for these kids, the easiest method of communicating is to engage in attention-seeking behavior—usually loudly and frequently!

And they often don’t know how to articulate themselves without being annoying. It’s a developmental problem. So for these kids, the easiest method of communicating is to engage in attention-seeking behavior—usually loudly and frequently!

But don’t despair. These behaviors are manageable, and your child can improve if you follow these do’s and don’ts the next time your child whines, cries, or screams to get your attention.

Do Be Empathetic

For young kids, approach the problem of annoying behavior with empathy. Empathy doesn’t mean that you completely understand your child’s behavior. Rather, it means that you know it’s coming from a place of developmental immaturity.

Yes, it can be hard to muster up empathy and kindness when your child is acting obnoxious. But once you understand their developmental level, you will know what they are and are not capable of handling, and you will be able to respond more appropriately.

Do Learn to Ignore Your Child When Necessary

Sometimes you need to ignore your child when they bother you for attention. This is not to say that you should always ignore every aspect of your child’s attention-seeking behavior. But it is okay to tell your child that whining will not get them what they want and that you will only speak to them when they can speak calmly.

This is not to say that you should always ignore every aspect of your child’s attention-seeking behavior. But it is okay to tell your child that whining will not get them what they want and that you will only speak to them when they can speak calmly.

Do Explain to Your Child What an Emergency Is

Explain to your child the difference between (1) a real emergency (where your immediate attention is warranted), and (2) something that your child wants but isn’t urgent. For instance, if the sink is overflowing upstairs, or a sibling has just escaped out the front door, those are real emergencies, and your immediate attention is needed. However, if your child wants to show you a video, and you’re talking on the phone, that’s not an emergency. They can wait for your attention in that instance.

Here’s a helpful tip: have a plan in place that allows your child to signal when something is truly important. Developing a catchphrase for them to say in a real emergency (for example, “code red”) helps your child learn to differentiate between a real emergency and simply wanting your attention.

Do Display the Rules for Your Child

One of the best ways to stop attention-seeking behavior in its tracks is to let your child know your expectations and what behaviors they need to avoid.

You can do this by creating a rules chart. Have them help you create it, and then hang it at their eye level (the refrigerator is a good place for it). Even if your child doesn’t read, just looking at the chart will serve as a reminder of the agreed-upon rules.

Here are a few examples of what can go on the chart: no whining, no screaming, and no running away when called. Next to each rule, list the consequence. For instance, sit by yourself for 5 minutes, go to bed 10 minutes earlier, or lose electronics time.

Of course, your child will break the rules at times—that happens. But when the rules are listed where your child can see them, you can then point and say,

“Sorry, no screaming is on the rules list. No television tonight.”

Do Be Consistent With Consequences

The biggest hurdle parents face in stopping attention-seeking behavior stems from not consistently enforcing the consequences when their child acts out. Too often, parents are tired, frustrated, or just want their child to be quiet. In short, they’re burnt out, so they give in rather than enforce the rules through consistent consequences.

Too often, parents are tired, frustrated, or just want their child to be quiet. In short, they’re burnt out, so they give in rather than enforce the rules through consistent consequences.

While giving in if you’re burnt out is understandable, make no mistake about it: your child is taking mental notes each time you yield to their demands. And the next time they want something, they’ll redouble their attention-seeking efforts to get it.

Do Give your Child Healthy Attention

Make sure you are giving your child a healthy amount of attention. Giving attention doesn’t mean meeting all of your child’s demands at every turn. Rather, it means engaging with them consistently and lovingly each day.

Healthy attention can come in the form of quality playtime, reading together, eating family meals and talking about your day, doing homework or school activities with them, and having a consistent bedtime routine.

Each day will be different in terms of how much attention you can give your child. Your busy schedule will dictate how much time you can spend, so be realistic about what you are capable of giving.

Your busy schedule will dictate how much time you can spend, so be realistic about what you are capable of giving.

And give yourself a break if you feel guilty about not giving enough—no one wins if you berate yourself for not fitting everything in.

Related Content: “Am I a Bad Parent?” How to Let Go of Parenting Guilt.

Don’t Yell Back at Your Child

It is very tempting to reduce your emotional responses to your child’s level, especially when the whining doesn’t stop, or you’re tired and at your wits’ end.

Try to have a plan in place for removing yourself from the situation when you feel like you might explode.

If your child doesn’t end the attention-seeking behavior, say to them:

“I need a time-out right now because you won’t stop whining. I’ll be back in 5 minutes.”

Then go to your quiet place and practice some relaxation and deep breathing exercises until you are calm enough to deal with your child.

Related Content: Calm Parenting: How to Get Control When Your Child is Making You Angry.

Don’t Make Your Child Feel Guilty

Juggling the responsibilities of kids, work, and life in general leaves many parents feeling chronically exhausted and overworked. As such, it can be tempting to guilt our kids into good behavior by unloading our difficulties (an unreasonable boss, a stressful encounter with a neighbor, a fight with a co-parent) onto them.

But the issues adults face should not be shared with our kids. Kids already deal with enough stress and anxiety of their own, and it’s not fair to burden them with your problems as well. There’s nothing wrong with your child knowing that you feel exhausted, but you should skip all the gory details. Just say to your child:

“I’ve had a busy day and have a headache. So I’d like you to stop whining, or you will have to sit by yourself.”

Don’t Assume There Is Something Wrong With Your Child

Many parents mistakenly believe that their young child’s attention-seeking behaviors signify that there is a bigger problem, and they panic.

On the contrary, most kids will act out at some point in their development—and that’s okay. It doesn’t mean that there is something wrong with your child. As a parent, you should expect this behavior during childhood and respond to it with effective consequences so that, over time, your child learns how to behave appropriately when they are frustrated or want attention.

Of course, if you are following these suggestions and still have concerns, or if your child is acting out in ways that are dangerous to themselves or others, contact your pediatrician immediately. Don’t ignore your parental intuitions if something doesn’t seem right.

Don’t Hover Over Your Child

You don’t have to be present every time your child needs something. Don’t feel guilty or fear that your child will feel unloved if you don’t always respond to attention-seeking behavior. Just know that part of good parenting is teaching your child that not all of their needs can be met. If you are always on-call whenever your child needs something, your child will never learn the value of patience, the importance of waiting their turn, and the understanding that they’re not the center of the universe.

Parents that hover over their kids run the risk of reinforcing the attention-seeking behavior, and the child may carry these behaviors into adulthood.

Related Content: How to Stop Worrying and Avoid Helicopter Parenting

Conclusion

Attention-seeking behavior can be annoying and difficult for parents to handle. Indeed, it can take the pleasure out of parenting altogether. Just remember that this is a perfectly normal stage of a young child’s development, and if you follow these do’s and don’ts, your child’s behavior will improve—and you will enjoy being a parent again.

Related Content: Stop the Show: Putting a Lid on Your Child’s Attention-seeking Behavior

Features of the development of attention of older preschoolers

This article deals with the actual problem of developing the attention of older preschoolers. The psychological features of the development of attention of children at the senior preschool age are analyzed.

Keywords: voluntary attention, senior preschool age.

The development of voluntary attention in preschool age is one of the indispensable conditions for successful schooling. Without purposeful, sufficiently stable attention, neither the independent activity of the child nor the fulfillment of the tasks of an adult is possible. The ability to act without distractions, to follow instructions, and to control the result obtained are all the requirements that the school places on the arbitrariness of children's attention.

Attention is included in the work of all cognitive processes, and it is almost impossible to separate it from them, to study attention in its “pure” form. At the same time, attention is an independent cognitive process, since it has its own properties that other cognitive processes do not have.

In Russian psychology, such scientists as N. N. Lange, L. S. Vygotsky, P. Ya. Galperin, D. N. Uznadze, S. L. Rubinshtein, N. F. Dobrynin, A. N. Leontiev .

Ya. Galperin, D. N. Uznadze, S. L. Rubinshtein, N. F. Dobrynin, A. N. Leontiev .

In the concept of N. F. Dobrynin, attention was formulated as an orientation and concentration of mental activity. From the standpoint of a scientist, orientation is the choice of activity and its maintenance, and concentration is a deepening into this activity and removal, distraction from any other activity [3].

According to their origin and methods of implementation, two main types of attention are usually distinguished: involuntary and voluntary.

The simplest type of attention is involuntary attention. It is established and maintained regardless of the person's conscious intention. It is no coincidence that this type of attention is sometimes called unintentional and passive.

Involuntary, or unintentional, attention is the focus of consciousness on an object or phenomenon due to certain features. The ability for such attention turns out to be innate in a person, for this reason L. S. Vygotsky called it natural [2].

S. Vygotsky called it natural [2].

The difference between involuntary attention lies in the spontaneity of its occurrence, the absence of efforts for its appearance and preservation. Accidentally arising, it can immediately fade away.

Voluntary attention is consciously directed and regulated attention associated with volitional effort and a consciously set goal. It is also called strong-willed, active, deliberate.

Some experts distinguish another type of attention - post-voluntary. This concept was introduced into scientific circulation by N. F. Dobrynin. They speak of post-voluntary attention when the result of purposeful activity is not only interesting and significant for a person, but also its content and the process of activity itself.

When they talk about the development, education of attention, they mean the improvement of its properties, which include: volume (the number of objects that can be perceived simultaneously), concentration (the degree of concentration on an object), distribution (the ability to perform several actions at the same time, keep attention several objects), stability (duration of concentration on an object), switchability (conscious transfer of attention from one object to another).

L. S. Vygotsky analyzed the history of the development of attention in line with his cultural-historical concept. Just like voluntary perception, voluntary memory, verbal-logical thinking, voluntary attention belongs to the highest mental functions of a person.

L. S. Vygotsky wrote that the history of the child’s attention marks the history of the development of the organization of its delivery, that the basis of the genetic understanding of attention lies outside the child’s personality, and not inside.

A child can master these means only in society, in communication with an adult and joint activities with him. The cultural development of attention is contained in the fact that, with the help of an adult, the child learns a number of artificial stimuli-means (signs), through which he further directs his own behavior and attention [9].

At preschool age, there are significant changes in the development of the child's attention. Throughout the entire period of preschool childhood, the involuntary attention of the child develops - its stability increases, its volume increases.

At this age, the main achievement in the development of attention is the formation of its new type, voluntary attention. Thanks to the development of this type of attention, children acquire the ability to correctly direct their consciousness to certain objects and phenomena, fix it for some time [10].

The development of attention in older preschool age is facilitated by the emergence of new interests, broadening of horizons, mastering new activities. Thus, the transition at preschool age to more complex types of play activities, to the implementation of the simplest labor tasks, in which the child is forced to reckon with the known rules and requirements of adults and the children's team, contributes to the development of voluntary attention [7].

But in itself the development and improvement of involuntary attention does not lead to the formation of its arbitrary types. The formation of the latter is associated with the inclusion of the child by adults in new activities, where, with the help of certain means, they direct and organize his attention. Adults, directing the child's attention, give him the means by which he subsequently begins to control his attention himself [1, 469].

Adults, directing the child's attention, give him the means by which he subsequently begins to control his attention himself [1, 469].

Emotionally significant stimuli play an important role in attracting the attention of a preschool child. But, despite the predominance of the role of these stimuli, in the older preschool age, the ability of children to associate any activity with verbal instruction increases significantly.

The development of voluntary attention provides for the ability of children to accept gradually more complex instructions, to keep them in their attention, as well as the development of self-control skills.

The formation of voluntary attention in a child is first detected when he subordinates his behavior to the verbal instructions of an adult. And then, as speech is mastered, it manifests itself in the subordination of the child's behavior to his own speech instruction. First of all, voluntary attention relies on inner speech. Therefore, well-developed speech favors the earlier formation of voluntary attention.

Reasoning aloud helps the child develop voluntary attention. Therefore, in order for a preschooler to learn to voluntarily control his attention, he must be asked to think aloud more. When completing a task according to an adult's instructions, children of older preschool age pronounce it 10–12 times more often than younger preschoolers [4,8].

Understanding the significance of the upcoming activity, awareness of its purpose also contributes to the development of voluntary attention. The goal of any activity stimulates attention, includes the necessary mechanisms to achieve it.

As the child grows, so do the properties of attention.

Intellectualization, which occurs in the process of the child's mental development, is essential in the development of his attention: it begins to switch from sensory content to mental connections. As a result, the scope of the child's attention expands.

Older preschoolers can simultaneously perceive three or four subjects with sufficient completeness and detail. But, the simultaneous perception by the child of several unfamiliar objects leads to a narrowing of the amount of attention. This can also occur when the objects perceived by the child are close to each other or, conversely, are placed over a large area.

But, the simultaneous perception by the child of several unfamiliar objects leads to a narrowing of the amount of attention. This can also occur when the objects perceived by the child are close to each other or, conversely, are placed over a large area.

If an adult explains the images, compares them, looks for causal relationships between them and involves the child in this process, then the result improves.

By the age of six, not only the number of objects that the child is able to perceive at the same time increases, but the range of objects that attract his attention also changes. The attention of the child begins to attract unremarkable outwardly objects. He is more and more interested in the person himself, in whose appearance and behavior he notices details, as well as in the activities of people [5].

At this age, the stability of attention noticeably increases, which is manifested, for example, in the increasing duration of children's games. The longest duration of games for younger preschoolers is 30 minutes, while for six-year-old children it increases to two hours. This is explained by the fact that in their games, older preschoolers reflect more complex actions and relationships between people, introduce new situations, which, in turn, contributes to maintaining interest in games.

This is explained by the fact that in their games, older preschoolers reflect more complex actions and relationships between people, introduce new situations, which, in turn, contributes to maintaining interest in games.

Starting from senior preschool age, children become capable of keeping their attention on actions that acquire intellectually significant interest for them [8].

Older preschoolers, unlike younger ones, not only can do uninteresting work for a longer time, but are much less likely to be distracted by extraneous objects.

At preschool age, the concentration of attention in children is still small, as well as the switching and distribution of attention, which must be developed. And the main role in this, undoubtedly, belongs to an adult, next to whom children grow and develop.

The foregoing allows us to conclude that the development of voluntary attention in children occurs in the process of mastering different types of activities. The main line of development of attention in the older preschool age is connected with the fact that children begin to master their attention, they form the ability to control it.

The main line of development of attention in the older preschool age is connected with the fact that children begin to master their attention, they form the ability to control it.

An attentive child perceives the necessary knowledge more accurately and effectively, which enable him to successfully develop mentally. The development of voluntary attention and its individual properties in preschoolers will help children to successfully cope with school assignments in the future.

Literature:

- Vygotsky L.S. Development of higher forms of attention in childhood // Psychology of attention. - M .: CheRo Publishing House, 2001 .- P. 467–507.

- Vygotsky L. S. Collected works: In 6 volumes / Ed. A. M. Matyushkina. - M .: Pedagogy, 1983. V.3: Problems of the development of the psyche. - 368s.: ill.

- Dobrynin N.F. On the theory and education of attention // Psychology of attention. - M .: CheRo Publishing House, 2001. - S.

518-534.

518-534. - Golovey L. A. Development of the personality of a child from five to seven. - Yekaterinburg: Publishing House Rama Publishing, 2010. - 576p.

- Kurdyukova S. V., Suntsova A. V. Attention! Attention! We develop attention: games and exercises; expert advice. - M .: Eksmo Publishing House, 2010. - 80s.: ill.

- Legchakova O. A., Kurchina V. V. Ways of forming arbitrary behavior // Questions of preschool pedagogy. - 2016. - No. 3. - P. 47–49. — URL https://moluch.ru/th/1/archive/41/1331/

- Leontiev A.N. Lectures on General Psychology. - M .: Publishing House of Meaning, 2000. - 508s.

- MukhinaV. C. Developmental psychology. Phenomenology of development: a textbook for students. higher textbook institutions, 15th edition. - M .: Publishing Center Academy, 2015. - 656 p.

- Nemov R.S. Psychology: textbook for bachelors. - M .: Publishing house Yurayt, 2014. - 639 p.

- Psychology of preschool children.

Development of cognitive processes / Ed. Zaporozhets A. V., Elkonina D. B. - M .: Prosveshchenie Publishing House, 1964. - 350s.

Development of cognitive processes / Ed. Zaporozhets A. V., Elkonina D. B. - M .: Prosveshchenie Publishing House, 1964. - 350s.

Basic terms (automatically generated) : voluntary attention, senior preschool age, child, attention, preschool age, type of attention, development, type of activity, child's attention, involuntary attention.

Destructive behavior of children and methods of correction

For the first time, Alfred Adler began to study the goals of the destructive behavior of children, and later - his student and follower Rudolf Dreikurs. At present, there are a number of well-known specialists - practitioners who are seriously developing this topic as the basis for raising modern children - O. Christiansen, W. Nicholl, L. Albert, D. Dinkmayer Jr., M. Popkin, etc.

Researchers in their pure form identified four leading goals of destructive behavior, manifested in preschool and primary school age:

- to attract attention;

- power struggle;

- revenge;

- demonstrating failure, or avoiding failure.

In adolescence, three more goals appear:

- the need to belong to a group;

- the need to achieve superiority over others;

- the need to achieve psychophysiological arousal.

However, these goals are poorly studied and are always combined with the goals of destructive behavior, which manifest themselves in preschool and primary school age.

From the point of view of Adlerian psychology, these goals are at the subconscious level, and we can identify and correct them using certain technologies described below.

1. Attracting attention.

Attention-getting child behavior:

- constantly pulls his parents - “mom, play with me”, whines, complains that something is not working out for him and he needs help;

- at school, he constantly pulls at the teacher - he raises his hand, asks to leave, again asks for help, etc .;

- children may also commit more serious acts, such as stealing or skipping school.

All this the child does in order to be paid attention to.

How can an adult determine if the purpose of destructive behavior is to get attention? At this point, you should ask yourself the question: “How do I feel about this?” If you understand that this behavior annoys you or the child requires you to devote a lot of time to it, this is an indicator that the child’s goal is to attract attention. You can also test yourself by asking the child: “Sunny, maybe it’s important for you now that I pay attention to you?” In this case, it is necessary to observe the child and see the "recognition reaction", if any. On a verbal (verbal) level, the child may simply agree by saying "yes". When a child answers “no”, it is important to observe his mimic reaction. At the non-verbal level, options are possible: a nod of the head, frequent blinking, cessation of motor reactions, stop or dilation of the pupils.

Why do children demand attention in an inadequate way?

They lack attention both at home and at school.

Adults have taught children to accept negative attention, such as, “I will pay attention to you and reprimand you when you misbehave; and if you behave well, then there is no need to pay attention to you. This situation often occurs at school when the teacher constantly draws attention to the bad behavior of the student. The child concludes: "They will pay attention to me if I misbehave."

Children sometimes don't know how to get positive attention, but they do know how to get negative attention.

Recommendations for behavior correction. It must be taken into account that they will work effectively only if they are used in combination.

If the child demands attention in an inadequate way, then at that moment it is not worth giving him attention. Instead, you should say, for example: "In 10-15 minutes I will be free, and you and I will do what you want." It is important to indicate a short time, because the child does not perceive a long time, for him it is eternity.

Take the initiative to pay attention to the child.

Teach kids to be positive. It is necessary to show children their importance and value when they meet the expectations of adults.

It is advisable to observe your speech, whether you are like a stepmother from the fairy tale "Cinderella", who criticized the behavior of her stepdaughter. Your child has many strengths, but there are also disadvantages.

2. Struggle for power.

The struggle for power is active and passive. The passive one is that the child silently listens to everything that the adult tells him (“Do your homework”, “Stop talking on the phone”, etc.), but does not do anything that he is told. An active struggle for power is expressed in the fact that the child resists not only non-verbally, but also in words: “I won’t, I don’t want to,” etc.

How to determine whether the goal of destructive behavior is the struggle for power? An adult needs to ask himself the question of how he feels when a similar situation arises. If he feels angry, then this is a clear indicator of a struggle for power. You can test this hypothesis by asking the child: “Maybe it is very important for you to show me (the teacher) what you decided yourself?” or “Maybe it’s important for you to show me that I can’t force you to do what I think is right?” After the question is asked, the adult must track the recognition reaction. In fact, the child's intentions are quite understandable: growing up, he is looking for his "place in the sun", trying to try and demonstrate his strength and significance. Adults need to take into account that from a very early age the child is trying to determine his capabilities and he does this by trial and error: “Will the parents give in or not? Yep, it worked! Now we have to try to conquer even more space…” and so on.

If he feels angry, then this is a clear indicator of a struggle for power. You can test this hypothesis by asking the child: “Maybe it is very important for you to show me (the teacher) what you decided yourself?” or “Maybe it’s important for you to show me that I can’t force you to do what I think is right?” After the question is asked, the adult must track the recognition reaction. In fact, the child's intentions are quite understandable: growing up, he is looking for his "place in the sun", trying to try and demonstrate his strength and significance. Adults need to take into account that from a very early age the child is trying to determine his capabilities and he does this by trial and error: “Will the parents give in or not? Yep, it worked! Now we have to try to conquer even more space…” and so on.

How to correct the behavior of a child who is fighting for power?

Never engage in a power struggle with a child at that particular moment when he imposes it on us.

Be sure to inform the child about the rules adopted in the family, starting with the words “It is customary for us . ..”, for example, “It is customary for us to clean the apartment on Saturdays” or “It is customary for us to talk quietly when someone is working at the table.” At the same time, a rather large burden falls on the adults themselves, who should not adhere to the so-called “double standards” when following the same rules. It is not clear to the child why he should stop talking on the phone at the moment when dad demands it, and at the same time mom can talk on the phone with her friends for hours. Or why he has to clean up after himself a plate from the table if dad does not. And so on.

..”, for example, “It is customary for us to clean the apartment on Saturdays” or “It is customary for us to talk quietly when someone is working at the table.” At the same time, a rather large burden falls on the adults themselves, who should not adhere to the so-called “double standards” when following the same rules. It is not clear to the child why he should stop talking on the phone at the moment when dad demands it, and at the same time mom can talk on the phone with her friends for hours. Or why he has to clean up after himself a plate from the table if dad does not. And so on.

The next step is to give the child a choice - to act in accordance with the accepted rules or break them. Thus, responsibility for their actions is brought up - not an adult, but the child himself decides what to do, he learns to make choices and make decisions.

Next, the adult reports on the possible logical consequences of the child's choice. For example, “You have a choice - you can participate in cleaning, or you can not participate. If you manage to clean your room before (some time), we will have time to go to the cinema, you can invite someone to visit, play on the computer, etc. (Here an adult offers one of the options for pastime). “If the room is left uncleaned, well, that’s a pity, but no one will be able to come to you” or “You will have to clean the room at another time, for example, when we planned to go to the movies. You know, it is customary for us to maintain order in the apartment. So the choice is yours."

If you manage to clean your room before (some time), we will have time to go to the cinema, you can invite someone to visit, play on the computer, etc. (Here an adult offers one of the options for pastime). “If the room is left uncleaned, well, that’s a pity, but no one will be able to come to you” or “You will have to clean the room at another time, for example, when we planned to go to the movies. You know, it is customary for us to maintain order in the apartment. So the choice is yours."

If a child breaks family rules, the parent must explain the logical consequences. Followers of Alfred Adler and Rudolf Dreikurs emphasize the fundamental difference between logical consequences and punishments.

As mentioned above, one way or another, it is important for a child to fight for power, to demonstrate his strength and significance. There are three areas in which an adult can help a child express himself. These are information management, people management, financial management. Using these zones, we can help the child feel and test his own strength.

Using these zones, we can help the child feel and test his own strength.

- When we punish a child, we deliberately try to hurt him. Moreover, we may want to make the child suffer. The purpose of applying logical consequences is not to make you suffer, but to teach you to take responsibility for your actions.

- When we punish a child, we scream, we demonstrate our negative emotions in relation to the child's personality. If an adult explains the logical consequences, the child does not feel negative attitude towards himself, since it is not the child's personality that is disapproved, but his actions. Thus, we teach the child constructive actions. We can calmly talk about the problem of choice, find out what logical consequences are possible, offer the child to choose and be sure to fulfill the option we have chosen, otherwise all systematic and consistent educational efforts will come to naught.

- Punishment is sometimes completely unrelated to the offense.

For example, if a child gets a bad grade at school on Friday, then they are not allowed to go to the movies on Sunday. There is no logical connection between events. The logical consequence must be directly related to the wrongdoing.

For example, if a child gets a bad grade at school on Friday, then they are not allowed to go to the movies on Sunday. There is no logical connection between events. The logical consequence must be directly related to the wrongdoing. - For a child, the word "never" should not be. For example, "you will never go ...". Such threats are usually not carried out. The child gets used to this and, as a result, does not perceive the words as a ban. Moreover, if we, using logical consequences, limit him to playing on the computer or watching his favorite shows on TV, then such a restriction should be short-term - an evening or a maximum of one day. Otherwise, children get used to the length of the punishment and eventually stop responding to it.

- When we punish, we use our power. What is the child's conclusion? "Who is stronger is right". In the case of the implementation of logical consequences, we teach the child to make choices, make reasonable decisions and be responsible for them.

3. Revenge (violation of trust between a child and an adult).

Revengeful behavior in a child occurs if the struggle for power between him and an adult is protracted, and both sides of this struggle become painful. Again subconsciously we make the child suffer. As a rule, in order to change the vengeful behavior in a child and in an adult, the intervention of an intermediary, such as a family psychologist, is necessary.

The actions of the child: calling names, spoiling property, deceiving, stealing, trying to hurt an adult in words and deeds. Such negative behavior can be directed not only at one particular person, but also transferred to all adults. The child learns to hurt by following the example of adults.

How to determine whether revenge is the goal of a child's destructive behavior? An adult can ask himself what he feels at this moment, and if he answers that he is hurt and offended, then, most likely, the relationship between the child and the adult is based on revengeful relationships. You can also try asking the child: “Maybe it is very important for you to show me how it hurts and hurts when you are offended or not trusted?” Do not use the word "revenge" itself. Next, observe the recognition reaction.

You can also try asking the child: “Maybe it is very important for you to show me how it hurts and hurts when you are offended or not trusted?” Do not use the word "revenge" itself. Next, observe the recognition reaction.

How to correct the behavior of the child in this case?

First you need to ask the child a question: “Who offended you and how?” If the relationship is based on revenge, then resentment “sits on the tip of the tongue”, and, as a rule, the child will immediately voice it.

An adult asks for forgiveness, while it is strictly forbidden to use the word "but". It’s better to just say: “I’m sorry, I’m sorry that I offended you,” without adding, for example, “but you yourself are to blame for this.”

Definition of the conflict zone. It is necessary to discuss with the child what mutual actions cause resentment.

Definition of expectations: what we expect from each other. Unfortunately, in the family, we rarely speak our expectations to each other, assuming that a loved one should already know this. Such a delusion leads to a conflict of expectations, starting from the first days of a young family's life.

Such a delusion leads to a conflict of expectations, starting from the first days of a young family's life.

Negotiation - how to meet each other's expectations.

It must be remembered that the restoration of relations does not occur immediately, sometimes it takes at least 1 year; The younger the child, the faster trust can be restored.

4. Demonstrating failure or avoiding failure.

The basis is the loss of courage by the child: he does not believe in his own success, considers himself worse than others. Behavioral reactions: absenteeism, lies, refusal to do homework, does not go to the blackboard, hides behind the backs of others, does not complete assignments, demonstrates with all appearance: “I am worse than others, I can’t do anything.” Such children are usually conflict-free, but they actively show their own helplessness.

How to determine this goal of destructive behavior? An adult can ask himself the question: “What do I feel at this moment?”. If the answer is: “I am in despair, my hands are falling”, - most likely, the child is demonstrating insolvency. You can ask a child a question: “Maybe you don’t believe in your own strength, that you can be successful?” At the same time, we observe the manifestation of the recognition reaction.

If the answer is: “I am in despair, my hands are falling”, - most likely, the child is demonstrating insolvency. You can ask a child a question: “Maybe you don’t believe in your own strength, that you can be successful?” At the same time, we observe the manifestation of the recognition reaction.

Most likely, there are serious reasons for demonstrating failure: constant criticism of the child; family authority; frequent comparisons with the best; neglect from others; psychological trauma, physical or sexual.

Recommendations:

- Completely stop criticizing the child. If you can’t avoid criticism, then for one critical remark, praise the child at least 10 times within 8 hours (data from NLP specialists).

- For such children, it is very important to break up tasks into small parts so that they can complete them successfully. A child needs experience to feel successful.

- Recognize, celebrate, celebrate not the end result, but the process itself.