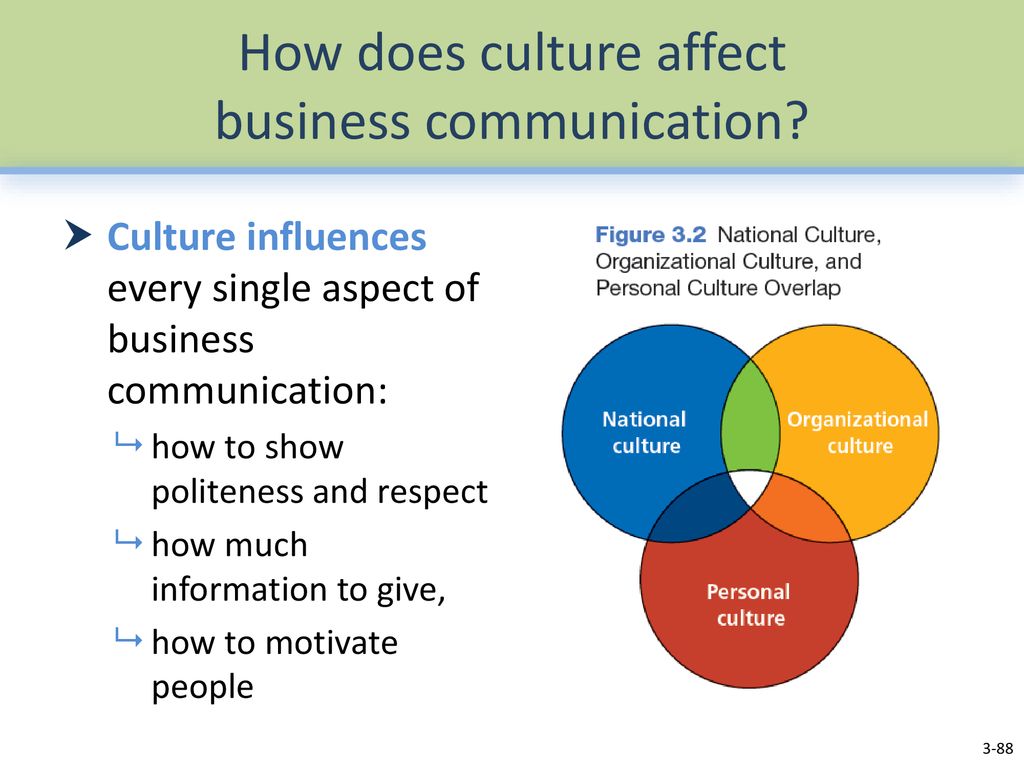

How do subliminal messages affect our behavior

How Subliminal Images Impact Your Brain and Behavior

Subliminal messaging – we’ve all heard about it. But it doesn’t really work, right?

New research from Valentin Dragoi’s lab at the University of Texas at Houston suggests that subliminal images can change our brain activity and behavior.

What does subliminal messaging entail? Subliminal messages are words or images presented below our conscious awareness. Usually we think of short frames cut into a video feed, where the subliminal message appears so quickly (usually less than one tenth of a second!) that our minds do not register their appearance. On the other hand, supraliminal messages are presented for longer periods of time, such that we can consciously see them.

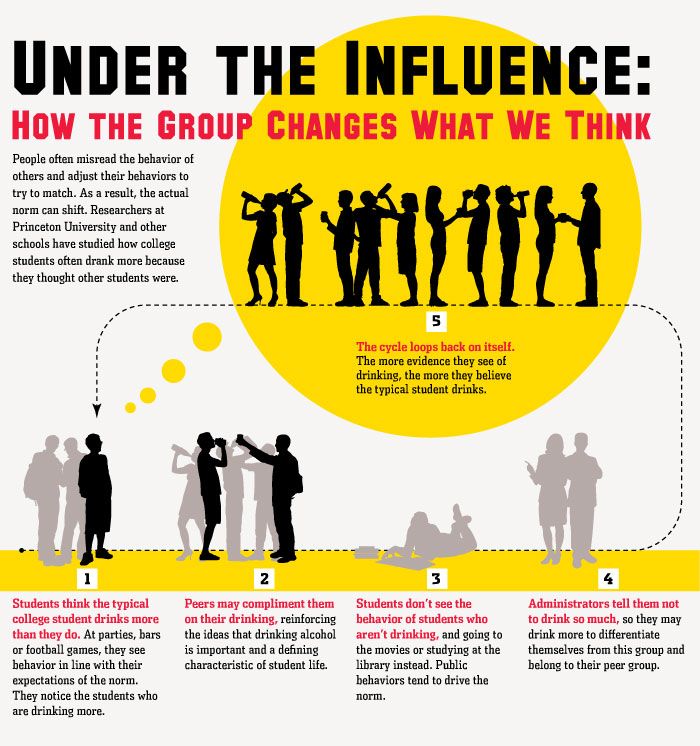

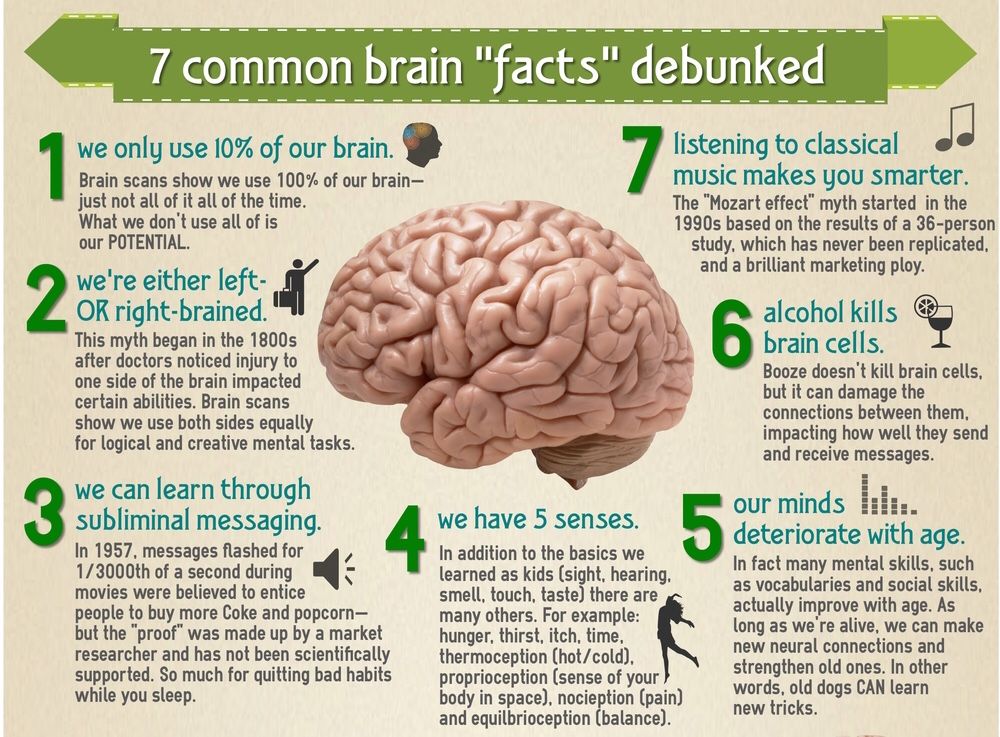

One of the most famous examples of subliminal messaging was conducted in the 1950’s. To test if subliminal messages could sway behavior, short messages stating, “Drink Coca-Cola” and “Hungry? Eat Popcorn” were played in a movie theater during a film. Although the results were later proved fraudulent, the researcher, James Vicary, claimed that presenting these suggestive messages increased concession sales.

So, does subliminal messaging actually affect us?

Importantly, and thankfully, subliminal messaging is not capable of brainwashing. However, there is evidence dating all the way back all the way to the 1960’s, which suggests that showing subliminal images improves behavioral performance.

Though the behavioral change has been established through multiple publications, we still don’t know how the brain processes subliminal images.

Sorin Pojoga, a member of Valentin Dragoi’s lab, set out to determine the neural underpinnings of subliminal images and how this brain activity changes our behavior. In a recent study, Pojoga and colleagues designed a task which would subliminally expose rhesus macaques to a set of natural images while recording from neurons in the primary visual cortex.

The natural images (such as a photograph of an animal) were imbedded in an oriented grating for either two or five consecutive frames, 33. 3 and 83.3 ms respectively. The authors found that subjects could easily identify the image when it was imbedded for five frames. However, subjects only guessed the correct image at chance level when the images were presented for two frames, meaning the images were below the subjects’ threshold for detection, making them subliminal.

3 and 83.3 ms respectively. The authors found that subjects could easily identify the image when it was imbedded for five frames. However, subjects only guessed the correct image at chance level when the images were presented for two frames, meaning the images were below the subjects’ threshold for detection, making them subliminal.

The authors had found that they could present images below the level of conscious detection. But the question remains if and how the brain registers these images. The authors addressed this in a follow-up experiment. Subjects performed tasks to test whether brain activity or behavioral performance changed due to subliminal image presentation.

Again, animals fixated on a central point on a computer screen while an oriented grating appeared. At a random point in each trial, a novel natural image was presented for two consecutive frames instead of the oriented grating. The inserted natural image was presented in its original form or rotated 5-20 degrees. Researchers could then align the trials at the time the subliminal natural image was present and analyze the data for any changes in neural activity.

Researchers could then align the trials at the time the subliminal natural image was present and analyze the data for any changes in neural activity.

Pojoga used a linear discriminant analysis (LDA) to decode neural responses to the natural images. LDA is a supervised learning model that attempts to classify data into different categories. In this case, researchers tested whether the LDA could separate trials based on which orientation the natural image was presented at. For 90% of the trials, they input firing rates from when the natural image was displayed and “trained” the model by pairing firing rates with the correct image orientation. Once the model was trained, researchers could then input the firing rates from the remaining 10% of trials and test the model, by letting the model categorize each trial by image orientation.

They found that LDA performance was significantly higher than chance level, meaning the neurons encoded the orientation of the natural image. Researchers also computed the LDA for a portion of the trial when the subliminal image was not being presented and found that LDA performance was not different from chance levels. This analysis further supports the conclusion that neurons were indeed processing the natural images.

This analysis further supports the conclusion that neurons were indeed processing the natural images.

With evidence that neurons are in some way processing the embedded natural images, the group reasoned that processing subliminal images should serve a purpose. They performed a follow-up experiment to determine if natural images, which were previously presented subliminally, would later improve neural processing during supraliminal presentation.

Subjects performed an orientation discrimination task. While animals fixated on a central point of a computer screen, a natural image was shown in the periphery. After a brief delay, the image was shown again. Subjects used a response lever had to signal whether the two images were shown at the same orientation, or if the second was shown at an angle (when the images were different, animals were trained to release the lever, but when the images were the same, subjects were expected to continue holding the lever). Importantly, 50% of the natural images used in this task were novel, but the other half were shown subliminally as natural images in the previous fixation task (described above). The natural images which were previously shown subliminally and now presented supraliminally in the discrimination task are referred to as “exposed” stimuli.

Importantly, 50% of the natural images used in this task were novel, but the other half were shown subliminally as natural images in the previous fixation task (described above). The natural images which were previously shown subliminally and now presented supraliminally in the discrimination task are referred to as “exposed” stimuli.

The authors found that neurons extract more information about exposed stimuli compared to unexposed stimuli, measured by a mutual information analysis. Additionally, they used d’ analysis and found that neurons are more sensitive to exposed stimuli.

Similar to the LDA performed during the two-frame presentation of the natural image, researchers found that LDA performance during the orientation discrimination task was significantly above chance level. Consistent with their hypothesis, the group found that LDA performance was significantly higher for exposed natural images compared to unexposed stimuli.

Together, these results suggest that subliminal priming (previously showing images subliminally) allows for improved image processing when those stimuli are later made supraliminal.

Through multiple analyses, it’s clear that single neurons show improved image processing for exposed images compared to unexposed images. But how does that happen if we’re not consciously aware of seeing the images in the first place? The authors argue that repeated viewing of subliminal stimuli activates groups of cells at the same time. As the old adage says, cells that fire together, wire together. So by activating groups of neurons simultaneously, subliminally stimulation could increase communication between neurons.

Pojoga and colleagues measured connectivity between cells by computing cross correlograms. This analysis measures the timing of spikes between two cells. The higher the number of coincident spikes, the stronger the coupling between those two neurons. The group hypothesized that higher coincident activity would occur for exposed images, signifying an increase in signaling between cells.

The group found that while both exposed and unexposed natural images produce strong cross correlograms, cross correlograms were significantly higher for exposed images compared to unexposed images. This suggests that repeated subliminal stimulation of natural images improves communication between groups of cells, making them better able to signal the image if it is shown supraliminally.

Controlling behaviorWith evidence for single neuron changes and support for a network-level mechanism, does any of this actually affect behavior?

Researchers used the same discrimination task described above, and simply computed the percentage of correct responses across all orientations for exposed compared to unexposed images. They found that animals performed significantly better on trials with exposed images. Additionally, this improvement for exposed stimuli tracked across orientations as well. For low-orientation-change trials, which are most difficult for the animal to get correct, performance was better for exposed compared to unexposed images. This suggests that single neuron and network-level changes in stimulus encoding are strong enough to alter perception.

This suggests that single neuron and network-level changes in stimulus encoding are strong enough to alter perception.

The authors found other evidence supporting behavioral changes as well. Animals took a shorter amount of time to make a response for exposed stimuli, suggesting a higher confidence in their decisions. Additionally, they found that behavioral performance was highly correlated with increased coincident spikes (measured by cross correlograms), suggesting that when neurons communicate better among themselves, improved behavior follows.

Am I being brainwashed?The short answer here – no!

As shown in this paper, subliminal imagery can significantly alter neural activity and behavior. But that doesn’t mean that if a car company flashes a subliminal message saying, “Buy this car,” that you’re instantly going to drive to a dealership and make an extravagant purchase.

Some experts suggest that subliminal messaging must be “goal-relevant” to a person. Showing a subliminal message saying “Drink Coca-Cola” won’t make you thirsty. But if you’re already thirsty and you see the same subliminal message, and you’re already thirsty, you’re more likely to buy the suggested brand. This influence is probably why subliminal messaging in advertising is banned in many countries.

Showing a subliminal message saying “Drink Coca-Cola” won’t make you thirsty. But if you’re already thirsty and you see the same subliminal message, and you’re already thirsty, you’re more likely to buy the suggested brand. This influence is probably why subliminal messaging in advertising is banned in many countries.

Subliminal messages live in our everyday lives, where we may never notice them. While behavioral studies over the years have suggested subliminal messaging can modulate our choices, this new study shows how these behavioral changes occur on a single neuron and network level.

Now you know – subliminal messaging is not a myth! Whilst it’s not going to brainwash you, maybe the next time you pick up your favorite drink, take a moment to ask yourself, “Why is this my favorite brand?”

Subliminal Messages Can Change Your Behavior – Association for Psychological Science – APS

This is a topic that is almost certain to interest students, and one that is ripe for discussion in an introductory psychology class, because the truth behind the claim is complicated. Discussion of this myth provides rich opportunities to integrate topics across research methods, memory, cognition, sensation and perception, and social psychology. It is relevant to students’ daily lives and provides opportunities to discuss applied research in social psychology, behavioral economics, and marketing. This unit is structured to get students to think critically about the claim, the kinds of evidence that would support or refute it, and the underlying psychological mechanisms that would be necessary for the claim to be true.

Discussion of this myth provides rich opportunities to integrate topics across research methods, memory, cognition, sensation and perception, and social psychology. It is relevant to students’ daily lives and provides opportunities to discuss applied research in social psychology, behavioral economics, and marketing. This unit is structured to get students to think critically about the claim, the kinds of evidence that would support or refute it, and the underlying psychological mechanisms that would be necessary for the claim to be true.

Note that many scholars (most recently Bargh, 2016) have highlighted the distinction between (a) being unaware of stimuli being present at all (e.g., those presented subliminally) and (b) being unaware of the effects of stimuli. In many priming studies, for example, individuals are consciously aware of the prime, but are nonetheless unaware of the ways in which the prime affects their subsequent cognition, affect, or behavior. Bargh and others argue that this latter unawareness still represents “unconscious” influence of the priming stimuli. Students are unlikely to make this distinction early on and are likely instead to be focused on sensationalized examples of truly subliminal influence. However, instructors should be aware of and prepared to discuss this distinction.

Students are unlikely to make this distinction early on and are likely instead to be focused on sensationalized examples of truly subliminal influence. However, instructors should be aware of and prepared to discuss this distinction.

Excellent resources for instructors to use in preparing for this unit include:

• Nick Kolenda’s website, which provides clear, evidence-based explanations of relevant phenomena: https://www.nickkolenda.com/subliminal-messages/

• An accessible review of relevant research: Bargh, J. A. (2016). Awareness of the prime versus awareness of its influence: Implications for real-world scope of unconscious higher mental processes. Current Opinion in Psychology, 12, 49 – 52. DOI: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.006

PRIOR TO DAY 1

Ask students what they’ve heard about subliminal perception and subliminal persuasion. At this point, don’t distinguish between perception and persuasion; just elicit from students everything they’ve heard. Examples students might generate and/or that you might ask about include subliminal messages in:

Examples students might generate and/or that you might ask about include subliminal messages in:

• advertising designed to get people to go buy products;

• popular films; and

• songs

Tell students that in the next unit, you will be exploring questions about what subliminal influence is, if and how it can be studied scientifically, and the extent to which we know the answer to questions about whether subliminal influence is real. Tell students that, as homework, they should find examples of attempts at subliminal influence. Many of these may have been mentioned already – the students’ job is to try to find actual examples of songs, video clips, images, and so on. Also ask students to read (or review) basic information (in the textbook or elsewhere) on the differences between sensation and perception, top-down versus bottom-up processing, and automatic versus effortful or controlled processing.

DAY 1

Goals: To help students break down the claim that we can be influenced subliminally and to begin critically thinking through evidence about the possibility of subliminal perception.

Have students share some of their examples of attempts at subliminal influence; depending on your class size, this could be done in small groups or as a whole class activity. For each example, ask students the following:

• What is the subliminal message? (e.g., a specific word, phrase, or image)

• What sensory modality(ies) are involved (sight, sound, etc.)?

• Assuming the message is real / intentional, what is the goal of the message? (e.g., to buy a specific product)

Highlight for students the range of ways in which so-called subliminal influence is being attempted in their examples, and ask them to consider what would need to happen for this influence to succeed. Use this discussion to guide students toward the following framework:

1. It would have to be possible to perceive stimuli outside of awareness.

2. Such perception would have to be capable of influencing thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors.

Explain that you will spend the rest of the class session tackling this first claim, i.e., that it is possible to perceive stimuli outside of conscious awareness — or, following Bargh’s (2016) distinction — that it is possible for our thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors to be influenced by stimuli without our awareness.

Guide students through an exploration of the following questions:

1. Based on what we know about how sensation and perception work in humans, is there any reason to think that it is possible to perceive stimuli that are outside of conscious awareness (or to be influenced by stimuli without our awareness)?

2. If the answer to question 1 is yes, how would we know?

The concepts below can all be used to help students answer these questions:

• Iconic and echoic memory

— Sperling’s (1963) classic studies showing that participants could not recall briefly flashed images (grids of letters or numbers) in their entirety, but could recall pieces of the images when immediately cued to a specific line of the grid. This demonstrated that participants sensed (and in turn perceived) the image, but could not recall it entirely because it decayed out of iconic memory too quickly. This can be used as basic evidence that people can sense and, at least for a fleeting moment, perceive briefly flashed images.

This demonstrated that participants sensed (and in turn perceived) the image, but could not recall it entirely because it decayed out of iconic memory too quickly. This can be used as basic evidence that people can sense and, at least for a fleeting moment, perceive briefly flashed images.

• Top-down processing

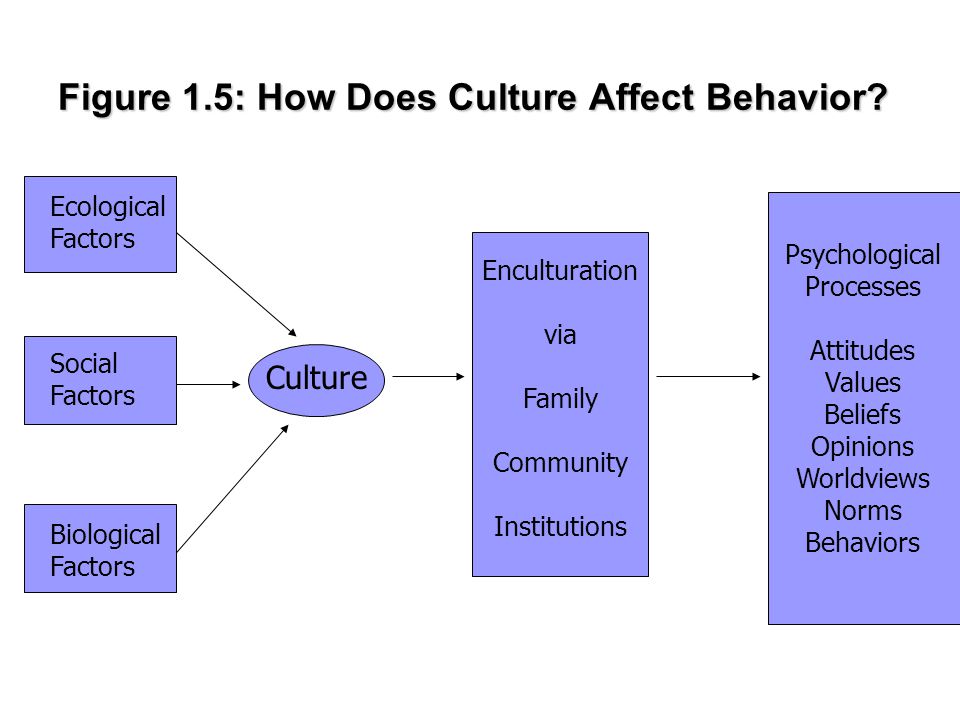

— Culture, experience, and expectations all influence our perception of stimuli, especially ambiguous stimuli. This processing occurs automatically and outside of conscious awareness, demonstrating that prior influences can indeed influence perception without our conscious awareness.

–This can be a good place to discuss back-masking in song lyrics. The website http://jeffmilner.com/backmasking/ provides several examples of clips from popular songs that can be played backwards and forwards. Typically, students cannot hear anything understandable in the backward lyrics, until told what to listen for. Suddenly, the “hidden message” seems clear. This procedure creates a memorable and relevant demonstration of how expectations influence perception.

• Schemas and schematic processing

— Schematic processing exemplifies top-down processing. You can use a classic demonstration in which you present a line drawing. Prior to showing it, tell half the class they are about to see a picture of a trained seal act, and tell the other students that they are about to see a picture of a costume ball.

Here is the drawing:

Here are some standard instructions:

Group A: You are going to look briefly at a picture and then answer some questions about it. The picture is a rough sketch of a poster for a trained seal act. Do not dwell on the picture. Look at it only long enough to “take it all in” once. After that, you will answer yes or no to a series of questions.

Group B: You are going to look briefly at a picture and then answer some questions about it. The picture is a rough sketch of a poster for a costume ball. Do not dwell on the picture. Look at it only long enough to “take it all in” once.

After that, you will answer yes or no to a series of questions.

Then show the drawing and ask these questions about it:

In the picture was there:

1. An automobile? ________

2. A man?________

3. A woman?________

4. A child?________

5. An animal?________

6. A whip? ________

7. A sword?________

8. A man’s hat?________

9. A ball?________

10. A fish?________

The schema (circus act or costume ball) affects how students perceive the subsequent image. Although the schematic frame was not presented outside conscious awareness, the effect of the framing on subsequent perception nonetheless happens automatically, without conscious control (cf. Bargh, 2016).

Priming is closely related to top-down processing and schematic processing. There are many good examples of priming, such as having students unscramble words. Ambiguous scrambles (e.g., efal) are more likely to be unscrambled as leaf than as flea after being primed with plants / flowers.

• Spreading activation or semantic network models of memory

— Reaction time tasks rely on spreading activation or semantic network models of memory: reaction times are shorter for closely associated concepts. Priming tasks and schematic processing also relate to these models of memory, in that a recently activated concept spreads activation to closely related concepts, making them temporarily more accessible and thus temporarily more likely to influence cognition, affect, or behavior.

Depending on variables such as your class size and structure, and students’ prior knowledge (including whether you have already gone over any of the concepts above in other units), there are several options for this discussion.

Here are three possibilities:

1. Present mini-lectures on some or all of the concepts above and then ask students how an understanding of those concepts helps answer the questions of whether it is possible to perceive stimuli outside of awareness and how we would know if such perception was happening.

— As described above, there are a number of excellent demonstrations of many of these concepts that could be used to help students experience priming effects, schematic processing, etc. After each demonstration, engage students in thinking about the extent to which the phenomenon they experienced is relevant to understanding subliminal perception.

2. Reverse the order of the questions and first have students derive a basic paradigm that would be needed to establish (a) that the observer was not consciously aware of the stimulus or its effects and (b) that the stimulus was nonetheless perceived or influenced perception. Elicit from students a basic paradigm such as the following:

Present the target message quickly. Establish that the target was (or its effects were) not perceived consciously

Ask participants what they saw or heard. Note that this is a great opportunity for reviewing issues related to leading questions, participants and researcher expectancy, and so on. For example, how might each of the following affect participant responses:

For example, how might each of the following affect participant responses:

• Did you notice the image that didn’t belong?

• Did you hear anything unusual?

• Describe what you saw

— Establish that the target was nonetheless perceived (e.g., through effects on subsequent perception, as in many priming tasks)

Once the basic paradigm has been thoroughly discussed, you could bring in the concepts listed above and illustrate how many of them are studied using similar paradigms. Discuss the extent to which our understanding of each concept helps us answer the question of whether stimuli can be perceived outside of conscious awareness.

3. Use a jigsaw classroom approach:

— Assign a different concept to each student group, asking them to first clearly define and describe the concept and then discuss the two guiding questions. You can ask students to use the sample worksheet provided below to structure their discussions.

— Check in with the groups to make sure they are on task and completing the worksheets correctly.

— Form new groups in which each of the assigned concepts is represented and have the students share their answers so all students see all how the concepts address the questions.

Facilitate a wrap-up discussion in which you review the answers to the overarching question:

1. Is it possible to perceive stimuli outside of awareness, or to be affected by stimuli in ways we are not aware of?

a. YES – theory and research on priming, schemas, spreading activation, and top-down processing all suggest that we can perceive visual and auditory stimuli that are presented outside of conscious awareness and/or that we can be unaware of the ways in which visual and auditory stimuli influence us.

Remind students that the existence of subliminal perception is not enough to support the kinds of dramatic alleged effects they found in the examples that they brought to class, including any meaningful influence on thoughts, feelings, or behaviors. Tell students that the next class session will be devoted to thinking critically about this key question. For homework, you might ask students to try to find evidence purporting to support the claim that subliminal perception can lead to meaningful effects on cognition, affect, or behavior; you might also ask students to read an original source article such as the one by Karremans, Stroebe, & Claus (2006).

For homework, you might ask students to try to find evidence purporting to support the claim that subliminal perception can lead to meaningful effects on cognition, affect, or behavior; you might also ask students to read an original source article such as the one by Karremans, Stroebe, & Claus (2006).

DAY 2

Goals: To help students critically think through evidence that subliminal persuasion is possible.

Begin by reviewing the work in the previous class — emphasizing that subliminal perception is possible but that the possibility of subliminal persuasion being at question. Review the examples of attempts at subliminal persuasion that students brought in last time, as well as any new evidence they have found, to identify the specific claims made (e.g., that a subliminal message in movie ads will cause patrons to go buy more popcorn or that back-masked song lyrics (messages recorded backwards) might cause some listeners to commit suicide). Highlight for students the ways in which these purported and feared outcomes of subliminal messaging compare to the kinds of dependent variables used in the research discussed in the last class. For example, how comparable is interpreting ambiguous stimuli in schematic-consistent ways after exposure to a prime to getting up out of your movie seat to go and buy popcorn?

For example, how comparable is interpreting ambiguous stimuli in schematic-consistent ways after exposure to a prime to getting up out of your movie seat to go and buy popcorn?

Briefly walk students through how researchers might test the claims being made about the effects of subliminal messaging. For example, using the classic subliminal messages in movie theater ads story, guide students to generate a study such as this:

• Randomly assign movie theater patrons to see either (a) a subliminal message encouraging snack purchase or (b) a neutral message.

• Measure snack sales.

Use this as an opportunity to review research design (random assignment, IV, DV, operationalization of variables, ethical issues, etc.)

Engage students in a discussion of the research evidence for subliminal persuasion of attitudes. Two good studies to cover are:

• the Bornstein, Leone, & Galley (1987) study on the mere exposure effect: mere exposure to a stimulus makes us like it more, even if we were not consciously aware of the exposure (the study found that subliminal exposure to abstract shapes and photographs of people lasting as little as 4 ms led to greater preference for those shapes and people).

• the Karremans, Stroebe, & Claus (2006) Lipton Ice study, in which subliminal priming of “Lipton Ice” led to greater intentions to drink Lipton Ice, but only among those who were thirsty. (The authors did not measure actual behavior.)

Discuss with students the implications – and limitations — of these studies.

• Subliminal influence on attitudes toward people, objects, and products does seem possible.

• Subliminal influence on behavioral intentions does seem possible – but only among people who were already motivated to engage in a particular behavior. Only thirsty people said they were more likely to buy a specific beverage; people who were not already thirsty showed no response to the subliminal message.

• But would such effects generalize to real-world situations? (e.g., how might differences in attention in the lab versus real world affect the effectiveness of subliminal messaging?)

• What effects on actual behavior might we see? If given the opportunity, would the participants in the Karremans et al.

study actually have purchased Lipton Ice?

If you have time, have students design a research study that would test some of the hypotheses raised in this discussion in order to help them apply their understanding of research methods and see how scientific research could help us answer these questions.

If you have a third day to spend on this unit, assign students to find additional research that has investigated these questions about subliminal persuasion, asking them to come to class next time prepared to share and discuss their findings. A list of possible sources is included below. You could also assign each student one article from this list rather than having students search for their own articles.

Regardless of whether you take 2 or 3 days on this unit, be sure to leave students with these take-home messages:

• Yes, subliminal perception is possible. We do not have to be consciously aware of or intentionally pay attention to stimuli in our environment for them to be perceived. We can observe evidence of this subliminal perception in basic priming effects, top-down processing, schematic processing, and so on.

We can observe evidence of this subliminal perception in basic priming effects, top-down processing, schematic processing, and so on.

• Yes, subliminal persuasion of attitudes is possible, but typically only for weak attitudes and behavior-consistent attitudes. For example:

— Only people already thirsty showed effects of brand priming on intent to buy a specific brand of beverage (Karremans et al., 2006)

— Only people already planning to donate to charity and who already held strong consistent values were influenced by a subliminal prime to donate more money (Andersson, Miettinen, Hytonen, Johannesson, & Stephan, 2017).

— Smarandescu & Shimp (2015) found thirsty participants were more likely to choose a primed brand when offered for free, but not when there was a brief (15-minute) delay between the prime and the choice, suggesting effects are relatively short-lived.

• Technically, then, subliminal influence is possible. However, the kinds of subliminal influence that happens (e. g., perceiving ambiguous stimuli in ways consistent with the subliminal stimulus) is a far cry from the kinds of subliminal influence people fear (e.g., losing free will, behaving in values-inconsistent ways).

g., perceiving ambiguous stimuli in ways consistent with the subliminal stimulus) is a far cry from the kinds of subliminal influence people fear (e.g., losing free will, behaving in values-inconsistent ways).

Suggested references

Andersson, O., Miettinen, T., Hytonen, K., Johannesson, M., & Stephan, U. (2017). Subliminal influence on generosity. Experimental Economics, 20, 531 – 555. DOI: 10.1007/s10683-016-9498-8

Bargh, J. A. (2016). Awareness of the prime versus awareness of its influence: Implications for real-world scope of unconscious higher mental processes. Current Opinion in Psychology, 12, 49 – 52. DOI: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.006

Bornstein, R. F., Leone, D. R., & Galley, D. J. (1987). The generalizability of subliminal mere exposure effects: Influence of stimuli perceived without awareness on social behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1070 – 1079. DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.53. 6.1070

6.1070

Karremans, J. C., Stroebe, W., & Claus, J. (2006). Beyond Vicary’s fantasies: the impact of subliminal priming and brand choice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 792 – 798.

Smarandescu, L., & Shimp, T. (2015). Drink Coca-Cola, eat popcorn, and choose Powerade: testing the limits of subliminal persuasion. Marketing letters, 26, 715 – 726. DOI: 10.1007/s11002-014-9294-1

90,000 Stories of the West and East. How "subliminal messages" affect peopleAlexei Kuznetsov leads the program. The correspondent of Radio Liberty in Prague Alexandra Wagner takes part.

Aleksey Kuznetsov: The humanities departments of two universities, Prague and Brno, recently completed research on a very interesting topic: how so-called "subliminal messages" affect people's behavior. Czech scientists came to the conclusion that under certain circumstances a person is able to turn into action a sound or visual impulse sent to him.

Alexandra Wagner: “Subliminal message”, “25th frame”, “subliminal” are different names for a method invented in the late 60s by an American marketer and analyst James Waikari. Its essence is as follows: if you include pictures with an image of an object or text that a person does not have time to recognize, but his brain has time to register, they are allegedly remembered at a subconscious level and can influence a person’s behavior. Subliminal messages can also be included in the sound range - for example, in a musical composition. For example, if the message “More Coca-Cola!” flashes several times in a movie theater during a movie, the viewer will drink twice as much as usual.

In fact, as it turned out pretty soon, not every subconscious is susceptible to such influence. For this reason, all the experiments that were carried out according to the Vaikari method in the media ended in complete failure, and he was declared a fraud. Continues Jiri Bystritsky, member of the Faculty of Humanitarian Studies, Charles University in Prague.

Jiri Bystritsky: Signals sent to the subconscious always cause some kind of reaction. Nevertheless, it is impossible to assert that the human consciousness is capable of easily succumbing to suggestion from the outside. To resist any external stimuli, whether it be an image, noise or music, the child learns from childhood. Here is a good example: a city dweller can fall asleep as a baby even if he lives near a freeway, but if a person from the countryside spends the night near the road, he will toss and turn and not close his eyes. An adult can be indifferent to the information received, and only if he treats it with interest, will he perceive it and remember it. It is enough to say to yourself, albeit unconsciously, “I will return to this topic later,” and that’s it, the brain received a signal: nothing happened. The subconscious can receive a million impulses a day, but if a person does not deal with them at the moment, then the consciousness is inactive.

Alexandra Wagner: Hidden messages are usually broadcast in a thousandth of a second. During this time, not everyone is able to perceive them. However, there are several methods that allow you to influence the actions of some people.

Jiri Bystritsky: For example, if you broadcast a hidden message and at the same time broadcast an interview with a person who enjoys great authority in society. The message in this case can be encoded into the noise of, say, a fan running in the room while the interview is being recorded. If a character evokes some emotions in you, for example, this is an actor whom you adore since childhood, then, of course, you will listen to his every word and be able to catch the message intended for the subconscious. Now imagine that in the brain information spreads like a virus, that it literally multiplies. Suppose you began to remember what your favorite actor said. Here, everything that you caught by listening to the interview, including the message for the subconscious, will be processed already in the “working memory”. In this case, the information can be dangerous for our behavior.

In this case, the information can be dangerous for our behavior.

Alexandra Wagner: The basic method of transmitting messages directed to the subconscious is still used today. For example, on Czech television. In one of the programs dedicated to sexual culture, erotic photographs flash on the screen at a very fast pace, but the viewer will never make out what is depicted on them. He can only guess. But in the intro to the children's evening program, an analogue of the Russian "Good night, kids!", Czech experts deciphered the subliminal. Continues Jaromir Volek from the University of Brno.

Jaromir Volek: Message with the text “Vote for peace!” turned out to be in the animated screensaver of an evening fairy tale for children. The cartoon was drawn in 1967, and we still do not know how this message ended up in the transmission. We had to go to TV to have this screensaver redone. We are sure that this is a signal for the subconscious, because the viewer does not notice the change in the image. The message can only be discovered after storyboarding.

The message can only be discovered after storyboarding.

Alexandra Wagner: Messages to the subconscious can also be transmitted using stereo sound: in a stereo system, a different sound is heard in each of the speakers. And electronic music is able to put a person into a state of artificial sleep, while any orders and messages can be transmitted to the brain. For this to happen, a monotonous sound must be listened to for more than 20 minutes. The complex system of human perception is an obstacle to subliminal messages. Only a few are able to respond to them, but even this is enough for the authorities to not cancel the current ban on their broadcast, prescribed in the law “On Television and Radio Broadcasting” of the Czech Republic.

What is the subconscious from a scientific point of view

The subconscious and the unconscious are still the subject of controversy in the scientific community. Understanding what is hidden outside of conscious thinking and whether it is possible to change life with the help of the subconscious

What is the subconscious

The subconscious in psychology is an area of the mind in which there are processes that are inaccessible to awareness, which it does not control. The idea of the existence of the subconscious arose in antiquity. Later Western philosophers thought about it: Spinoza, Leibniz, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. The concept of the subconscious was first formulated by the Austrian psychiatrist and founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud in the 19th century.

The idea of the existence of the subconscious arose in antiquity. Later Western philosophers thought about it: Spinoza, Leibniz, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. The concept of the subconscious was first formulated by the Austrian psychiatrist and founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud in the 19th century.

Dmitry Smyslov, candidate of psychological sciences, counseling psychologist:

“The subconscious is an outdated term. Now we use the term "unconscious". It includes both psychic phenomena and experiences that are not strongly controlled by consciousness.

How the subconscious works in Freud's theory

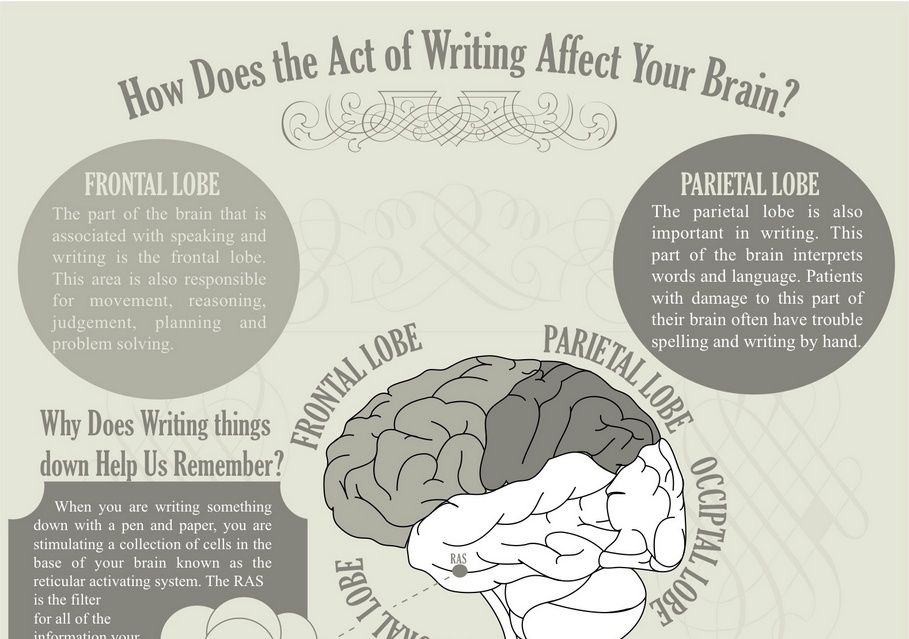

Freud divided the mind into three levels: preconscious, conscious and unconscious (subconscious). Let's look at them in more detail.

Preconscious. Consists of everything that has the potential to become conscious - thoughts or memories that we are not yet aware of, but we can if we focus. For example, we can forget how the summer went 10 years ago, but if we focus, the memory will appear in our minds.

Consciousness . It consists of thoughts, memories, feelings that we know about, that is, we are aware of. It is consciousness that is responsible for rational and logical thinking, focusing attention. Conscious experience refers to the things that we are thinking about at the moment - the information that we perceive when we read a text or have a conversation.

Subconscious. Freud believed that the subconscious is a reservoir of feelings, thoughts, impulses and memories that are beyond our conscious understanding. The subconscious mind also stores repressed feelings that are too painful or embarrassing to face consciously, such as hidden memories, habits, or desires.

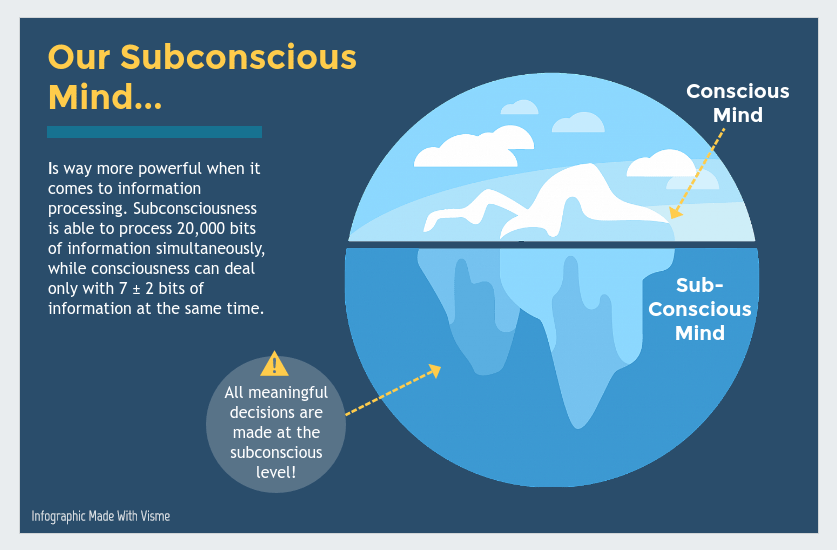

Freud liked to compare the mind to an iceberg: "The mind is like an iceberg, only a seventh of it floats above the water" (Photo: blog.infodiagram. com)

com)

At the same time, Freud was sure that the subconscious has the greatest influence on our behavior. Its contents may pop up unexpectedly, for example, in dreams or in reservations. This is how the term “Freudian slip”, familiar to many, appeared.

An example of such a clause is when a man accidentally calls the current girl by the name of the former. Someone will take this for a mistake, but according to Freud, this is the intervention of the subconscious due to unresolved internal conflicts or repressed feelings.

Freud's model of the unconscious is still the most detailed, but his conclusions cannot be considered scientific, because they are made on the basis of personal observations of a psychiatrist, and not in the course of scientific experiments. At the same time, psychology recognizes that Freud made a huge contribution to the development of the discussion about the subconscious.

The subconscious in modern psychology

“What is the subconscious responsible for, what is the consciousness responsible for?” — remains one of the key questions of modern psychology. There are several approaches to interpreting and studying the unconscious.

There are several approaches to interpreting and studying the unconscious.

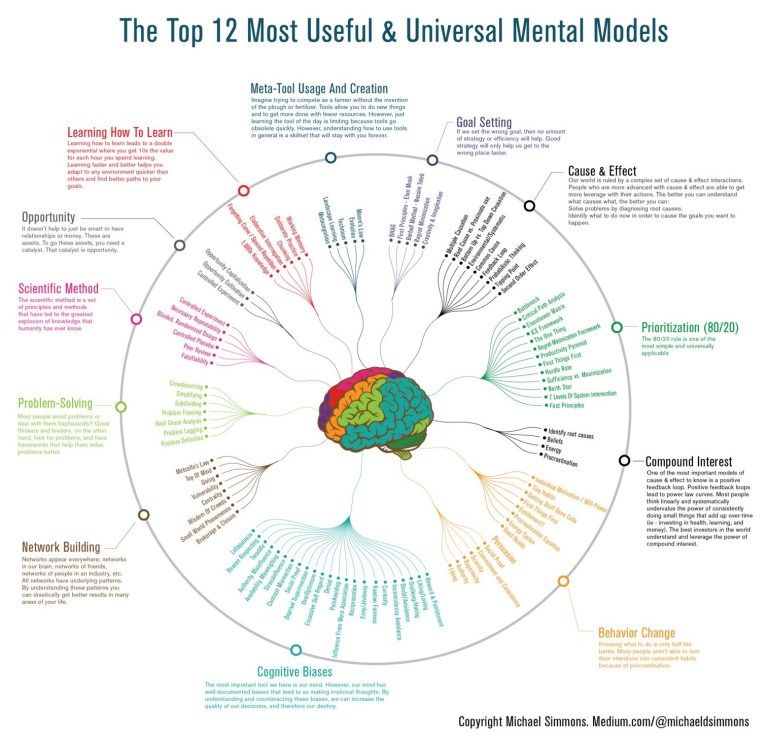

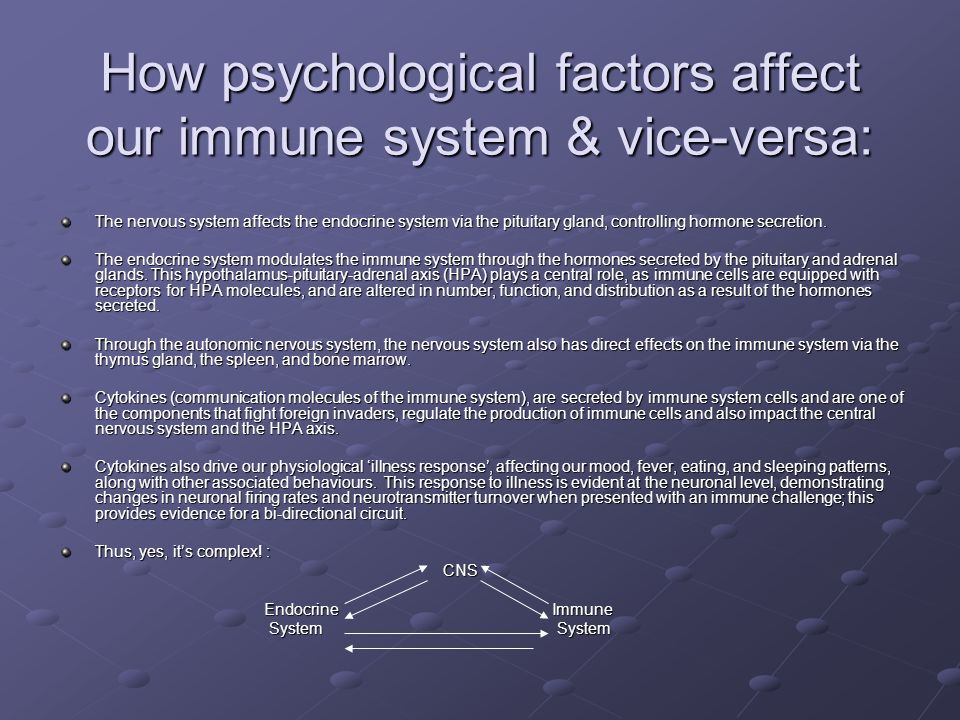

Cognitive psychology recognizes that not only conscious but also unconscious processes play an important role in cognition - they are commonly called the "cognitive unconscious". And experts in cognitive psychology note that we may not be aware of the information we perceive, but it affects our behavior.

Dmitry Smyslov believes that there are different approaches to the study of the subconscious, they depend on the psychological school and direction: “Indeed, the unconscious has a rather serious effect on a person, on his behavior. Suppose, if we read a person's behavior from the point of view of non-verbal communication, his gestures, facial expressions, pantomimes, then to a greater extent a person manifests himself unconsciously.

According to the psychologist, in classical psychoanalysis and neopsychoanalysis, dreams are also considered a manifestation of the unconscious in terms of the symbols they build, and are often the occasion for additional analysis.

The unconscious occupies about 70-75% of human behavior, the rest is consciousness. At the same time, consciousness has control mechanisms, but most often it is the unconscious that determines behavior.

Dmitry Smyslov:

“When information enters the area of consciousness, a person immediately begins to doubt, suspect, distrust — protection appears. The unconscious is always perceived as a command to act, for example, in the case of attitudes that are laid down in childhood. Therefore, consciousness always tries to control the unconscious, tries to protect it. But still, it can be said that the unconscious controls consciousness much more often than vice versa.

Where the subconscious mind resides

Neuroscientists agree that a significant amount of brain activity occurs unconsciously. A person performs some actions automatically, for example, he travels along a familiar route. Science is trying to find out exactly how this mechanism works, and how much the subconscious mind influences our actions.

Libet's experiment

Back in 1983, American scientist Benjamin Libet conducted an experiment in which participants were seated in front of a clock and asked to bend their fingers or move their wrist whenever they wanted, memorizing the position on the watch at that moment.

What happened. It turned out that brain activity occurs before a person's conscious decision to perform an action. In other words, unconscious mechanisms are triggered before we have a conscious intention to do something. Subsequently, Libet was criticized, claiming that he used inaccurate methods of measurement, but it was this experiment that gave rise to a lively discussion about the subconscious.

New Libet experiment

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Cognitive and Brain Sciences decided to conduct an updated version of the Libet experiment in 2013. This time, 36 volunteers looked at the letter in the center of the computer screen, which changed every second. Participants pressed one of two buttons whenever they felt like it. After that, four letters appeared - it was required to choose the one at the appearance of which they pressed the button.

Participants pressed one of two buttons whenever they felt like it. After that, four letters appeared - it was required to choose the one at the appearance of which they pressed the button.

What happened. Volunteers took an average of 22 seconds to press a button. They felt they had consciously decided to do it about a second or less before they made the move. But according to fMRI data, activity in the prefrontal cortex of the brain occurred 7 seconds before the subjects became aware of their decisions. It turns out that by the time of the conscious decision to make a movement, this had already been influenced by processes in the prefrontal cortex for several seconds.

Research into the subconscious continues to this day, often for medical purposes. For example, it has recently been found that unconscious changes in movement can predict Alzheimer's disease years before the onset of cognitive symptoms. Another recent study by Belgian scientists has shown that insights do indeed come from the subconscious. But, despite scientific progress, there are still more questions than answers in the study of the subconscious.

But, despite scientific progress, there are still more questions than answers in the study of the subconscious.

An interesting study was done using Ouija boards popular in the US for séances. During communication with the spirits, the participants hold the pointer together with their hands, ask questions and wait for otherworldly forces to move the pointer letter by letter. Participants of the experiments note that the pointer moves independently, answering questions. It turned out that this is due to the ideomotor phenomenon - an unconscious involuntary movement that occurs when a person thinks about the process. And the subconscious mind often helps to “think out” the answer if the conscious mind can’t cope. (Photo: Unsplash)

Is it possible to influence the subconscious

Now the concept of working with the subconscious to achieve your goals is becoming popular. The main idea is that by using special techniques of working with the subconscious, you can “direct” your thinking in the right direction, change your life and even recover from illnesses. For example, through meditation, visualization, positive affirmations.

The main idea is that by using special techniques of working with the subconscious, you can “direct” your thinking in the right direction, change your life and even recover from illnesses. For example, through meditation, visualization, positive affirmations.

Neurophysiological process researcher Joe Dispenza draws on neuroscience, biology, epigenetics and psychology in his books. At the same time, Dispenza himself works as a doctor of chiropractic, and there is no reliable information about the availability of other qualifications.

One of his main ideas is that all potential events exist in the quantum field as infinite possibilities - “when we tune our electromagnetic radiation to a wave already present in the quantum field, our body will be attracted to the desired event, we move to a new timeline, or the desired event will itself find us in a new reality. Dispenza's theory is reminiscent of the "Law of Attraction" - one of the postulates of the religious-mystical movement "New Thinking", which arose in the United States in the last quarter of the 19th century.

However, there is no scientific evidence of the effectiveness of such practices. Research has noted the benefits of meditation for several conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome, psoriasis, anxiety disorder, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. But there is no evidence that working with the subconscious and thinking can cure some kind of disease.

Associate Professor of Translational Neuroscience at Michigan State University, Alison Bernstein, says you can't magically make things happen. But a person can change their reaction to certain situations, and this is more like cognitive behavioral therapy.

Alison Bernstein:

"We can control our thoughts to some extent and we can acquire new habits - I don't have a problem with that part."

Neuroscientist Tara Swart in the book “Source. How to Rebuild the Brain to Achieve the Life of Your Dreams” explains that events do not happen through magic, but because a person begins to notice possibilities that were previously ignored.