Anxiety or hypoglycemia

How to Recognize and Treat Hypoglycemia-Related Anxiety

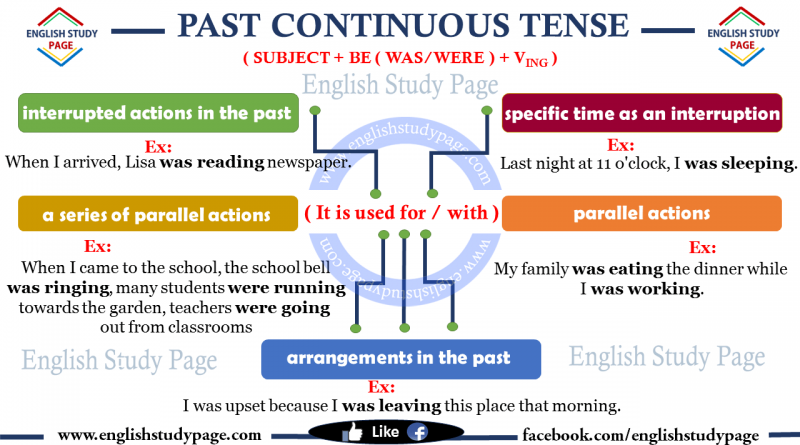

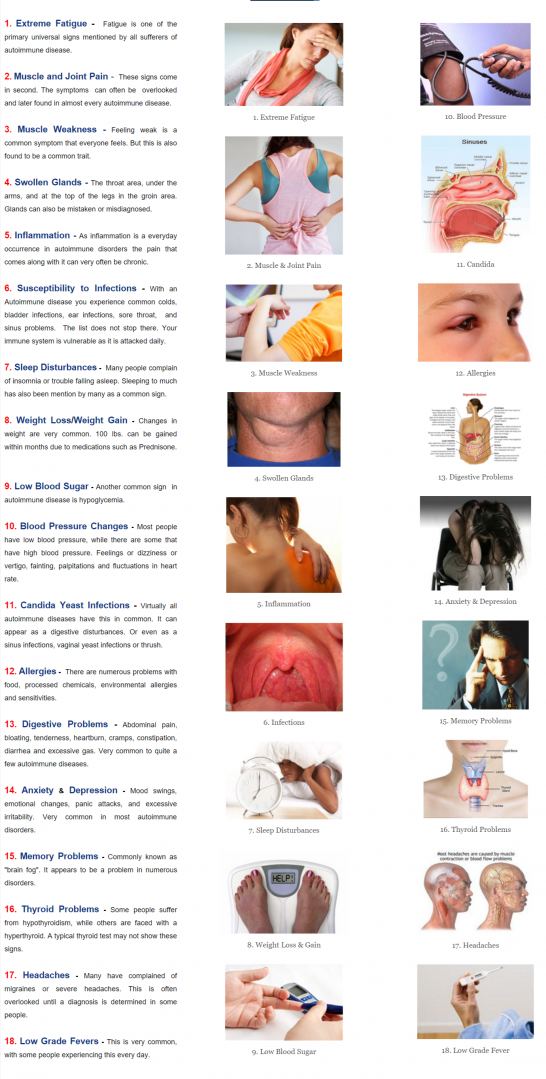

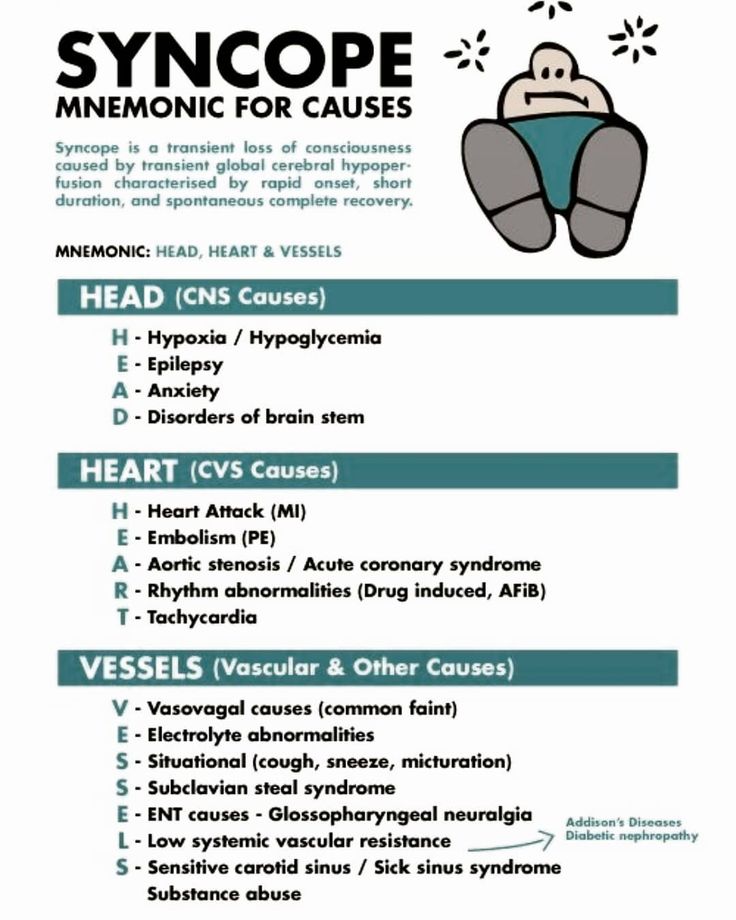

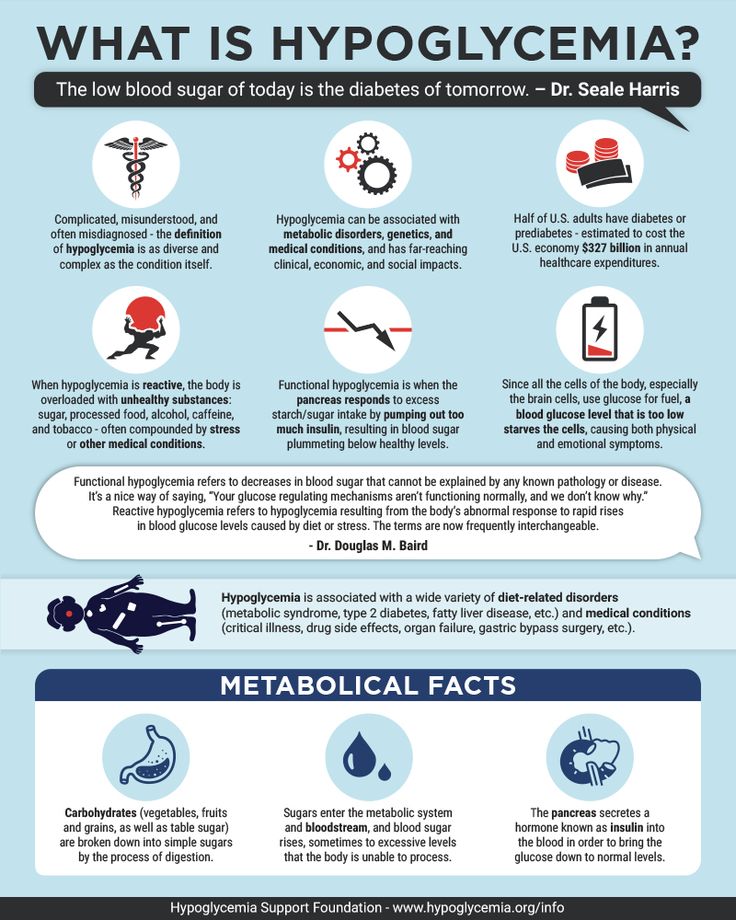

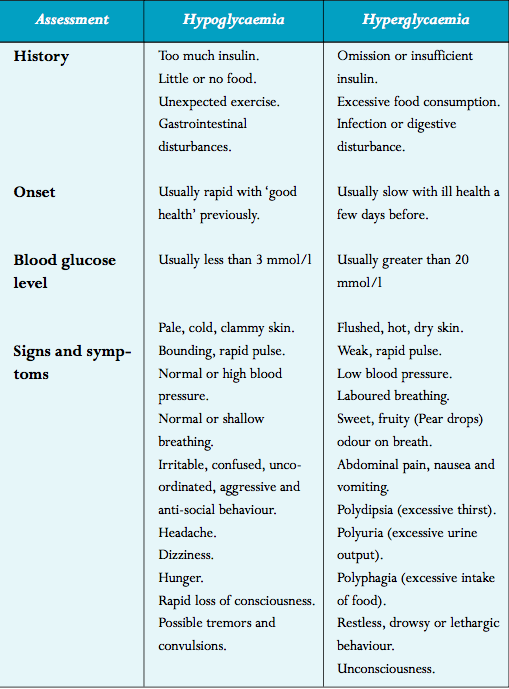

Hypoglycemia and anxiety are conditions that in some cases may be closely related. Hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar, is a condition usually accompanying diabetes. The symptoms of hypoglycemia are similar enough to those of anxiety to make it easy to mistake for hypoglycemia for an anxiety disorder or attack. While hypoglycemia symptoms are a result of the bodily stress it induces, it requires different treatment and preventative techniques than standalone anxiety.

Though anxiety and hypoglycemia are related, an anxiety disorder cannot cause hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia, however, can cause anxiety. It is important to be able to distinguish anxiety from a hypoglycemia so that your symptoms can be treated in a timely manner.

It's not uncommon to have health concerns that can be caused by, or related to, anxiety. In some cases, people believe that their anxiety symptoms must be a health problem. In others, a health problem can cause people to be anxious.

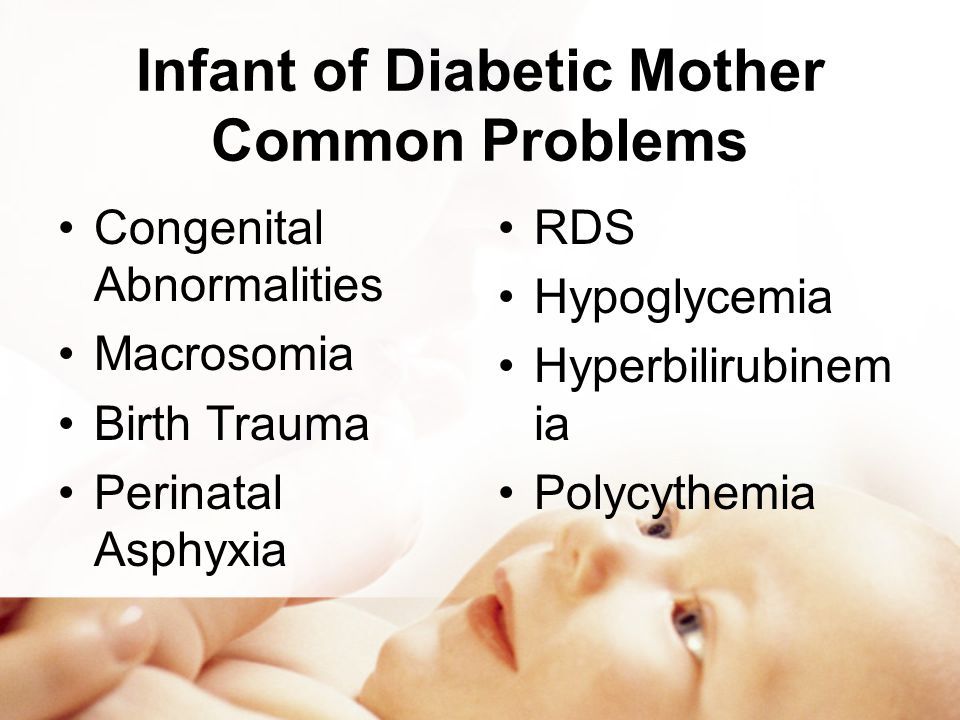

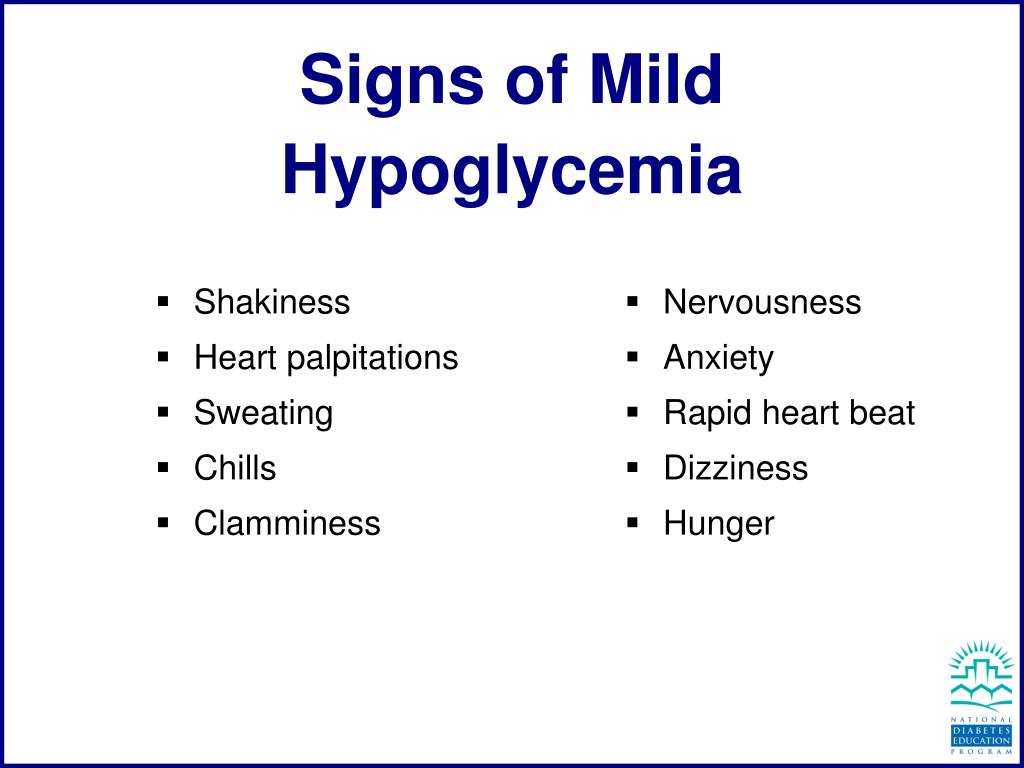

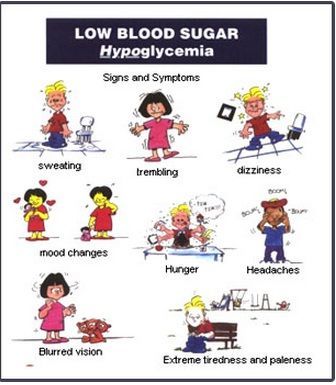

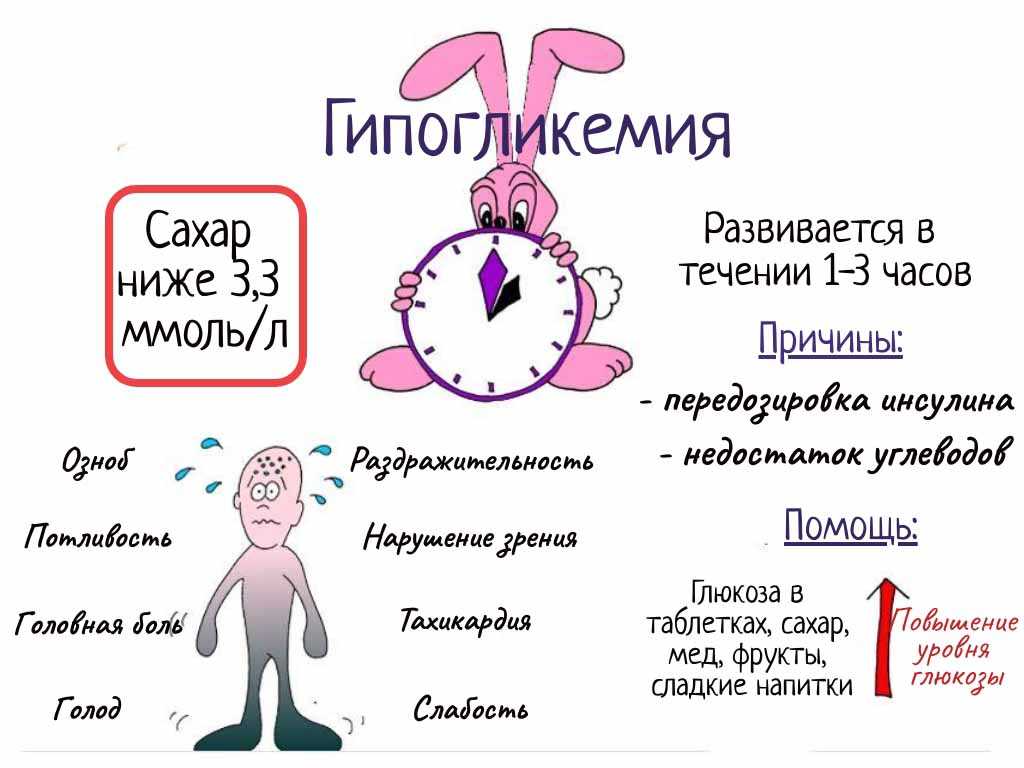

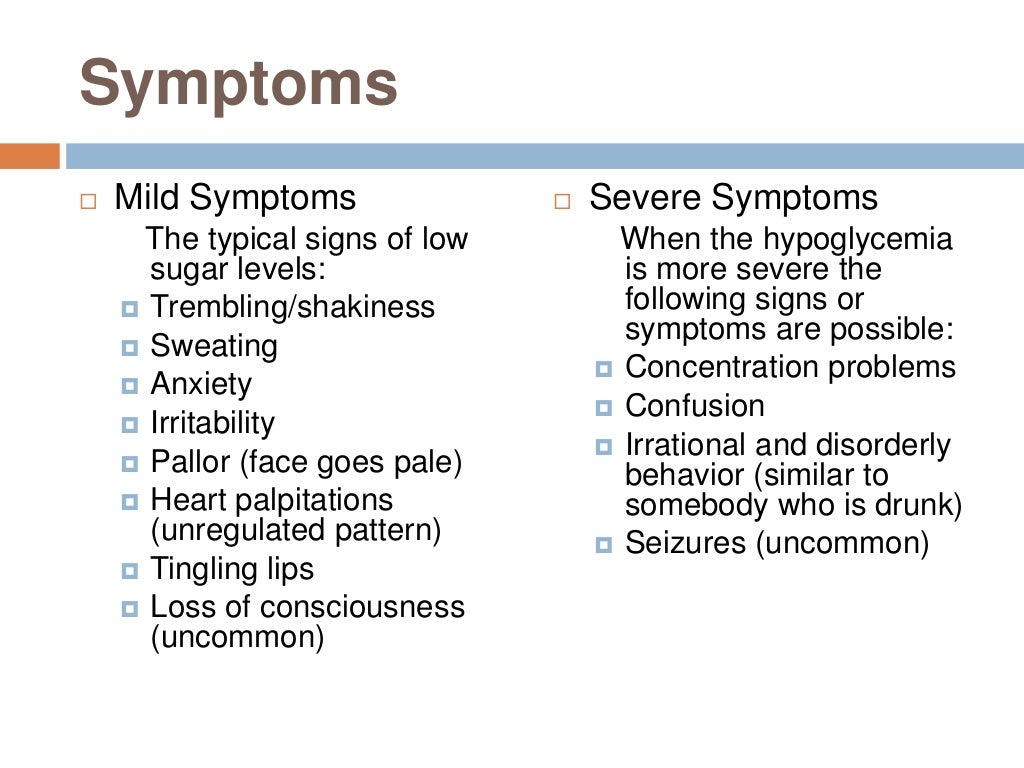

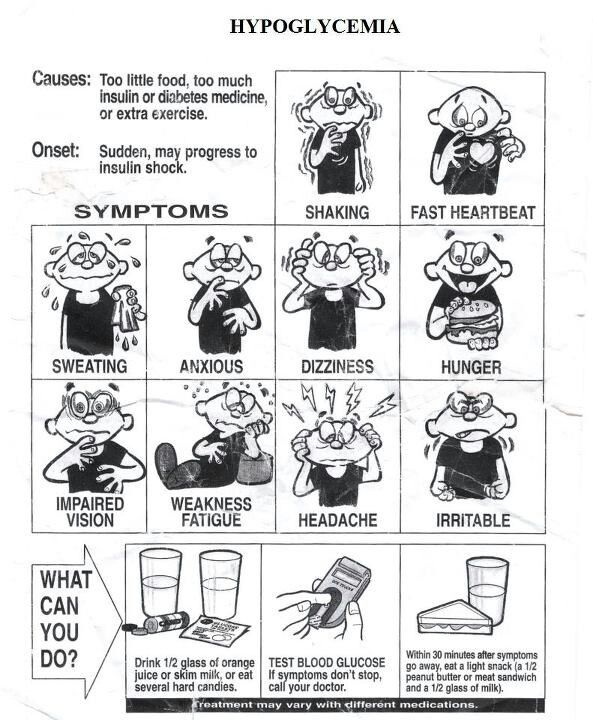

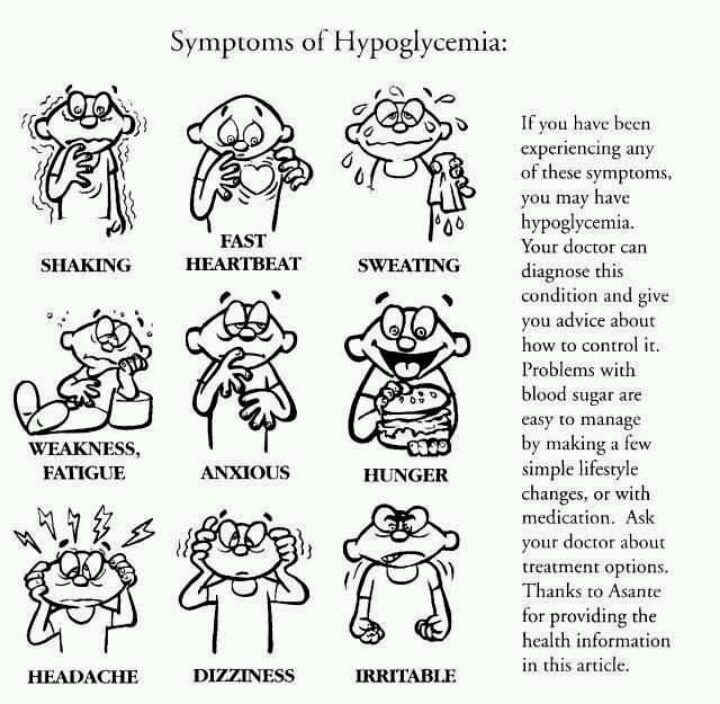

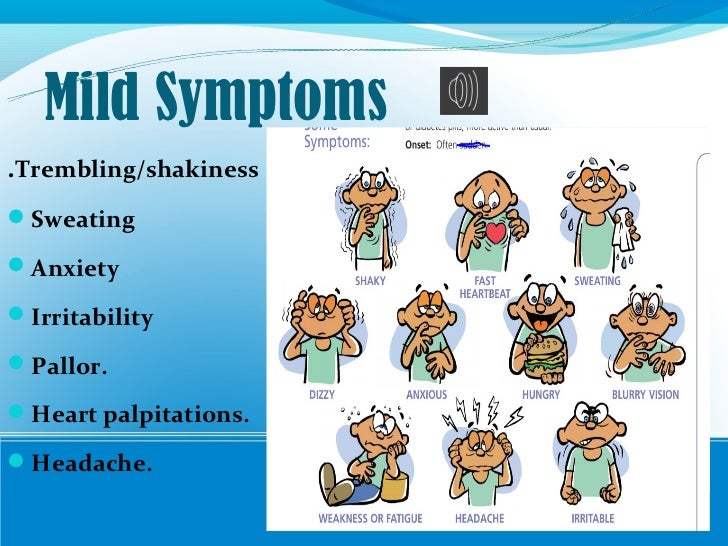

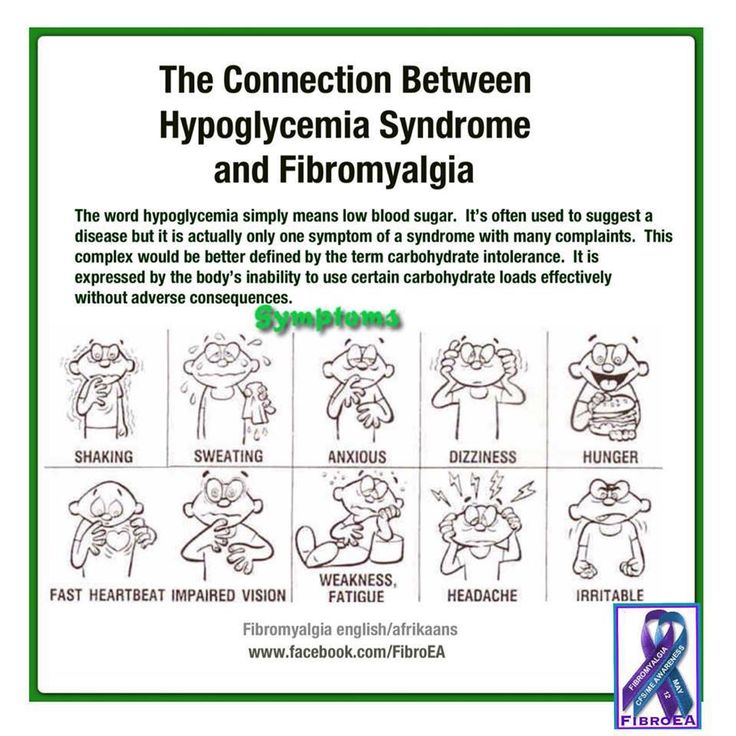

Hypoglycemia, whether severe or mild, can result in a variety of symptoms commonly recognized as the result of anxiety. These include:

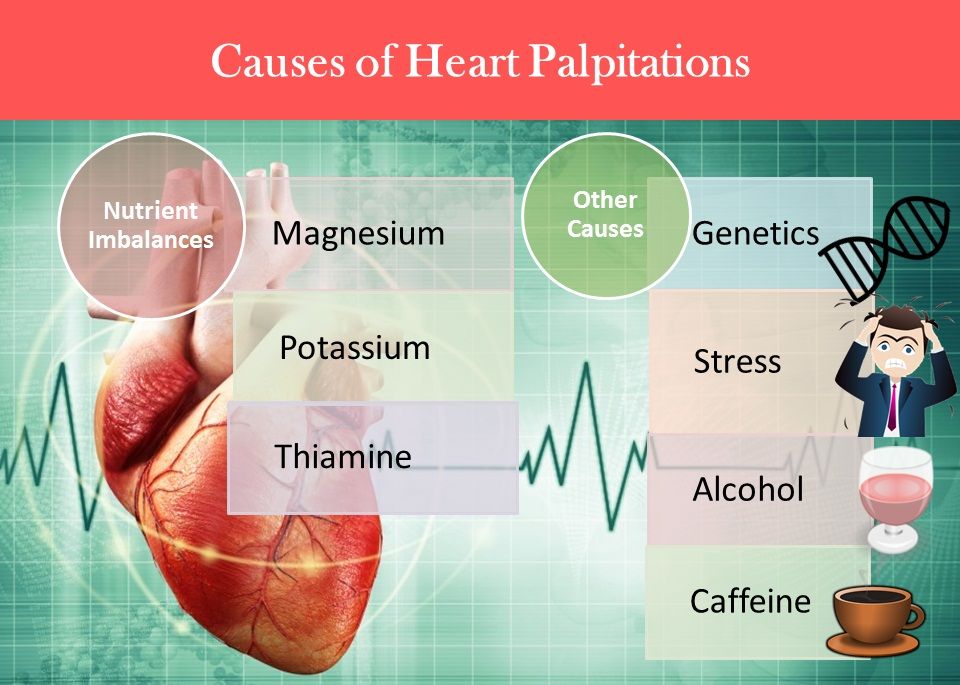

- Heart palpitations (rapid or irregular heartbeat)

- Shaking

- Sweating

- Paleness

- Cold/clammy skin

- Nausea

- Seeing flashes of light

- Dilated pupils (a common fear-response symptom)

- Moodiness

- Negative attitude

- Exaggeration of relatively minor problems

All these symptoms match up to what you would expect to see or experience during an anxiety attack. However, hypoglycemia is also often accompanied by symptoms that do not appear in regular anxiety attacks or conditions, including the following:

- Hunger

- Slurred speech similar to drunken slurredness

- Blank stare/look and “zombie-like” behavior

If you are experiencing any of these in addition to your other anxiety symptoms, you should take the preliminary step of eating something to help regulate your blood sugar. It is recommended that you go see your doctor as soon as possible to be tested for hypoglycemia.

It is recommended that you go see your doctor as soon as possible to be tested for hypoglycemia.

Ruling Out Hypoglycemia

If you are worried that your anxiety symptoms may be caused by hypoglycemia, you should check with your doctor as soon as possible in order to be sure. To officially rule out hypoglycemia, a blood test is required. However, the blood test should NOT be performed immediately after an episode of intense anxiety symptoms. This is because after one of these events, your blood sugar may already be dangerously low, and needs time to recover to prevent further attacks.

A test for hypoglycemia involves a 12-hour fast, after which the doctor can take a sample of your blood and find out whether it has reached dangerously low levels of glucose (the sugar in your blood that provides you with energy). Try to calm yourself during this time - waiting for this type of test can create its own anxiety, and often hunger and thirst contribute to anxiety as well. Try to stay relaxed and busy.

A hypoglycemic attack is no fun, and it is hard to function during it. However, whether you are having a regular anxiety attack or a hypoglycemic attack, it is perfectly safe to eat something to raise your blood sugar levels in either case.

If you find yourself having to do this often (and find that it helps), you probably have hypoglycemia, but it is always best to do to a doctor to be sure (as stress eating can also be an effect of an anxiety disorder and should not be encouraged as it can become an unhealthy coping mechanism).

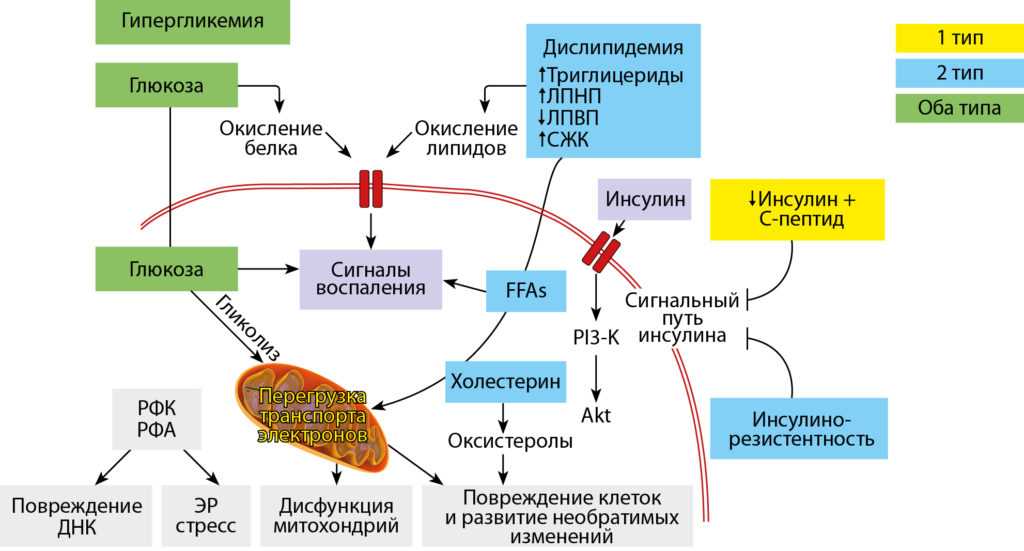

If you have either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, an excess of insulin (a medication that lowers your blood sugar) may be causing your hypoglycemia. If this is the case, talk to your doctor about adjusting your dosage of insulin.

Otherwise, eating regular, healthy meals is crucial in maintaining the correct levels of blood sugar in your body. Going on a new fad diet, excluding certain food groups from your diet, or starving yourself to lose weight are all common ways for anxiety to sneak into your life when you don't need it.

When making a dietary change, be sure that you get advice from a professional such as your primary care doctor or a nutritionist.

How to Prevent Anxiety Over Hypoglycemia

Most likely, if you haven't already been diagnosed with hypoglycemia, you're simply experiencing anxiety. It's perfectly normal to feel as though your anxiety symptoms must be the result of a health problem, and not anxiety, since in many cases anxiety mimics serious health concerns.

Anxiety is more common than many of the health disorders it mimics and unfortunately people with anxiety commonly experiencing health anxiety which may cause further concern over the symptoms they experience.

Was this article helpful?

- Yes

- No

Sources:

- Wild, Diane, et al. A critical review of the literature on fear of hypoglycemia in diabetes: Implications for diabetes management and patient education.

Patient education and counseling 68.1 (2007): 10-15.

Patient education and counseling 68.1 (2007): 10-15. - Gorman, Jack M., et al. Hypoglycemia and panic attacks. Am J Psychiatry 141 (1984): 101-102.

- Irvine, Audrey A., Daniel Cox, and Linda Gonder-Frederick. Fear of hypoglycemia: relationship to physical and psychological symptoms in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Health Psychology 11.2 (1992): 135.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Hypoglycemia Symptoms Improved with Diet Modification

Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016; 2016: 7165425.

Published online 2016 Jul 14. doi: 10.1155/2016/7165425

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Observational evidence suggests that a relationship may exist between high glycemic index diets and the development of anxiety and depression symptoms; however, as no interventional studies assessing this relationship in a psychiatric population have been completed, the possibility of a causal link is unclear. AB is a 15-year-old female who presented with concerns of generalized anxiety disorder and hypoglycemia symptoms. Her diet consisted primarily of refined carbohydrates. The addition of protein, fat, and fiber to her diet resulted in a substantial decrease in anxiety symptoms as well as a decrease in the frequency and severity of hypoglycemia symptoms. A brief return to her previous diet caused a return of her anxiety symptoms, followed by improvement when she restarted the prescribed diet. This case strengthens the hypothesis that dietary glycemic index may play a role in the pathogenesis or progression of mental illnesses such as generalized anxiety disorder and subsequently that dietary modification as a therapeutic intervention in the treatment of mental illness warrants further study.

AB is a 15-year-old female who presented with concerns of generalized anxiety disorder and hypoglycemia symptoms. Her diet consisted primarily of refined carbohydrates. The addition of protein, fat, and fiber to her diet resulted in a substantial decrease in anxiety symptoms as well as a decrease in the frequency and severity of hypoglycemia symptoms. A brief return to her previous diet caused a return of her anxiety symptoms, followed by improvement when she restarted the prescribed diet. This case strengthens the hypothesis that dietary glycemic index may play a role in the pathogenesis or progression of mental illnesses such as generalized anxiety disorder and subsequently that dietary modification as a therapeutic intervention in the treatment of mental illness warrants further study.

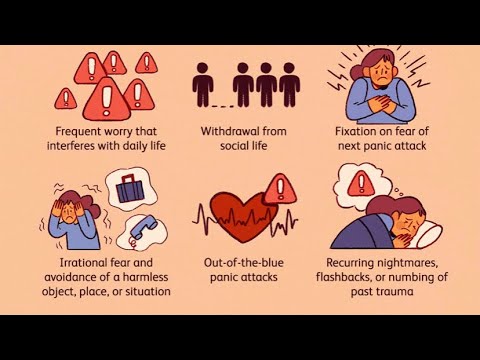

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a common and often disabling disease. It is characterized by fear, tension, and excessive worries regarding common events or problems for a minimum of six months [1] and is accompanied by physical symptoms such as heart palpitations, muscle tension, and chest tightness. Patients may experience nonspecific symptoms such as irritability and difficulty concentrating in addition to deterioration in the quality of their social, work, and personal experiences [1, 2]. Traumatic life experiences, dysfunctional serotonin, and epinephrine neurotransmitter systems and pernicious genetic influences are potentially involved in the development of GAD [3]. It is estimated that the lifetime prevalence is between 4.3% and 5.9% [1, 3] and 40–67% of patients experience comorbid depression [3].

Patients may experience nonspecific symptoms such as irritability and difficulty concentrating in addition to deterioration in the quality of their social, work, and personal experiences [1, 2]. Traumatic life experiences, dysfunctional serotonin, and epinephrine neurotransmitter systems and pernicious genetic influences are potentially involved in the development of GAD [3]. It is estimated that the lifetime prevalence is between 4.3% and 5.9% [1, 3] and 40–67% of patients experience comorbid depression [3].

Conventional treatment of anxiety involves cognitive behavioural therapy in combination with pharmacologic interventions such as serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), or benzodiazepines [2, 3]. Despite appropriate treatment, many GAD patients cannot successfully achieve short term or long term remission. After five years, remission rates may remain as low as 38% [2]. Thus, the need for nonpharmacological approaches is evident [4].

Several studies suggest a relationship between improved nutrition and better mental health outcomes, both in general and adolescent populations. Epidemiological studies, including a recent meta-analysis, have shown that a diet including fruits, vegetables, fish, olive oil, nuts, and legumes may reduce the chance of developing depression [4, 5]. A prospective study found that a Mediterranean dietary pattern at baseline reduced the risk of depressive episodes 16.5 years later [6].

Despite evidence correlating a healthy diet with the maintenance of mental health, a trend towards a reduction in the quality of adolescent diets has been observed at the global level. This trend is characterized by an increased intake of fast foods, fried foods, sweets, refined grains, processed meat, and a reduction of fruit/vegetable intake [7]. The consumption of this Western-style diet has been independently associated with a greater risk for the development of anxiety and depression [7] and associated with a decline in the mental health status of adolescents [6]. Another study found an increased likelihood of psychological problems in adolescents associated with diets high in unhealthy foods [7].

Another study found an increased likelihood of psychological problems in adolescents associated with diets high in unhealthy foods [7].

A number of possible mechanisms have been proposed for the effect of diet on mental health including a role of inflammation and oxidation [6], deficiency of micronutrients such as folate, zinc, and magnesium [7], and glycemic balance.

The increase in global consumption of refined foods such as sweetened beverages, pastries, and refined carbohydrates impacts dietary glycemic index (GI), a measurement of the rate of blood glucose generation from specific food items. Glycemic load (GL) reflects both the glycemic index value and the total carbohydrate content of the food. Foods with a higher GI or GL create greater increases in blood sugar [8].

A recent cohort study showed that increasing odds of depression and anxiety have been associated with the consumption of foods that have a progressively higher GI and this relationship is maintained after controlling for micronutrients known to play a role in mental health [8]. Cross-sectional studies have demonstrated a correlation between the occurrence of depression/stress and higher intake of sweet foods [9] and a large prospective cohort study showed a positive correlation between a diet high in sweet desserts and refined grains and the risk for depression. Conversely, it was found that high consumption of fruits and vegetables, which contain fiber that lowers GI, was associated with a lower risk for depression [9].

Cross-sectional studies have demonstrated a correlation between the occurrence of depression/stress and higher intake of sweet foods [9] and a large prospective cohort study showed a positive correlation between a diet high in sweet desserts and refined grains and the risk for depression. Conversely, it was found that high consumption of fruits and vegetables, which contain fiber that lowers GI, was associated with a lower risk for depression [9].

In addition to the observational studies, a limited number of interventional studies have explored a potential relationship between blood sugar balance and emotional and cognitive health. One clinical trial assigned healthy overweight subjects to high or low GI diets and found that the high GI diet resulted in worsening mood scores [10]. Two studies assessed the impact of high and low GI meals on cognitive performance in adults with type 2 diabetes and children, respectively, and found that the higher GI meal was related to poorer cognitive function [11, 12]. Conversely, two other intervention studies comparing high and low GI diets in patients with diabetes did not find a change in subclinical depression or cognitive function [9]. Despite this evidence that a relationship between dietary GI and emotional and cognitive functioning may exist, no interventional studies have assessed the impact of a low GI or low GL dietary intervention in psychiatric patient populations in order to assess causality of the relationship.

Conversely, two other intervention studies comparing high and low GI diets in patients with diabetes did not find a change in subclinical depression or cognitive function [9]. Despite this evidence that a relationship between dietary GI and emotional and cognitive functioning may exist, no interventional studies have assessed the impact of a low GI or low GL dietary intervention in psychiatric patient populations in order to assess causality of the relationship.

AB is a 15-year-old female student of south-Asian descent. She presented with concerns of anxiety and symptoms of hypoglycemia as well as difficulty concentrating, fatigue, headaches, asthma, and frequent urinary and vaginal infections.

Her anxiety met criteria for GAD and she rated the intensity of anxiety as 8/10, with 10 being the highest level of anxiety possible. The anxiety started three months prior to the initial appointment and had worsened in the previous month. She described excessive worry that was difficult to control and impacted her daily functioning by causing her to be absent from school on several occasions. She experienced a number of somatic symptoms including heart palpitations, shakiness, discomfort in her stomach, and muscle tension. In response to the anxiety symptoms, she would eat foods like chocolate, chips, or fruit. AB was working with a counsellor to manage the anxiety symptoms and was finding some benefit.

She experienced a number of somatic symptoms including heart palpitations, shakiness, discomfort in her stomach, and muscle tension. In response to the anxiety symptoms, she would eat foods like chocolate, chips, or fruit. AB was working with a counsellor to manage the anxiety symptoms and was finding some benefit.

AB had experienced episodes suggestive of hypoglycemia since 12 years of age. The symptoms included muscle weakness and shaking, headaches, nausea, anxiety, and loss of concentration. Her symptoms were ameliorated by eating sweet foods. AB reported that her hypoglycemia was at its worst at 12 years of age when she had to eat a granola bar hourly in order to concentrate.

2.1. Clinical Findings

A diet history revealed the following typical daily food intake:

Breakfast: fruit smoothie containing fruit, fruit juice, and water.

Morning snack: bagel with margarine.

Lunch: pasta or white rice with vegetables.

Afternoon snack: granola bar or cookies or gummy candies.

After school meal: white pasta; it may include meat.

Dinner: white rice or spaghetti; it may include meat.

Evening snack: cookies and toast.

Beverages: 2 liters of water, 1 cup of juice, 1 cup of lactose-free milk, and 1 cup of tea.

2.2. Past Medical History

Due to her difficulty concentrating, AB was prescribed dextroamphetamine 5 mg. While she found that it improved concentration, this medication caused her to lose weight. As the patient's weight was initially on the lower end of normal (weight: 115 lb., height: 5′6′′, and BMI: 18.6) the dose was reduced to 2 to 3 times per week, as needed.

2.3. Psychosocial History

AB lives with her mother, father, and sister. AB's sister experienced mental health concerns in the previous years which created elevated stress levels in the family home.

2.4. Diagnostic Focus and Assessment

Repeated assessments of random and fasting blood glucose and screening physical examination were within normal range.

2.5. Therapeutic Approach

At the initial visit, the following dietary plan was prescribed:

Breakfast: it includes a smoothie containing fruit, water, 1 scoop of protein powder, and 1 tablespoon of flax seeds or olive oil.

Lunch and dinner: they include a serving of protein (meat, legume, and soy) and a serving of vegetables.

Snacks: they include protein when possible (e.g., apple with sunflower seed butter, vegetable sticks with hummus, and pumpkin seeds).

Continue to eat carbohydrate-containing snacks as needed for the management of hypoglycemia symptoms.

She was asked to follow these dietary guidelines daily until the follow-up visit. While eggs, nuts, and fish would have normally been recommended as well, the patient had an anaphylactic allergy to these foods.

2.6. Follow-Up and Outcomes

At the first follow-up, four weeks later, AB reported that she had complied with the dietary plan since the previous visit. She reported a significant decrease in anxiety (4 to 5/10), as well as improved energy, less-frequent and less intense hypoglycemia symptoms, and fewer headaches (once per week compared to daily) in addition to improved concentration and mood. She required fewer snacks during the day and decreased her intake of granola bars, cookies, and candies (1-2 servings per day). She also reported a cessation of chronic vaginal discharge. The substantial improvement in her anxiety symptoms prompted AB to temporarily discontinue her counselling sessions.

She reported a significant decrease in anxiety (4 to 5/10), as well as improved energy, less-frequent and less intense hypoglycemia symptoms, and fewer headaches (once per week compared to daily) in addition to improved concentration and mood. She required fewer snacks during the day and decreased her intake of granola bars, cookies, and candies (1-2 servings per day). She also reported a cessation of chronic vaginal discharge. The substantial improvement in her anxiety symptoms prompted AB to temporarily discontinue her counselling sessions.

At a subsequent follow-up visit four weeks later, AB reported that she had briefly reverted back to her original diet for a period of one week and experienced a worsening of anxiety symptoms within one day. After returning to the dietary intervention prescribed, her anxiety symptoms decreased within two days.

This case illustrates an example of improved anxiety and hypoglycemia symptoms in response to changes in the macronutrient composition of the diet. It suggests that dietary GI and blood sugar balance, within a physiologic range, may play a role in the development or clinical progression of anxiety. Subsequently, modifying the diet by reducing the consumption of refined carbohydrates and including more protein, fat, and fiber may be beneficial.

It suggests that dietary GI and blood sugar balance, within a physiologic range, may play a role in the development or clinical progression of anxiety. Subsequently, modifying the diet by reducing the consumption of refined carbohydrates and including more protein, fat, and fiber may be beneficial.

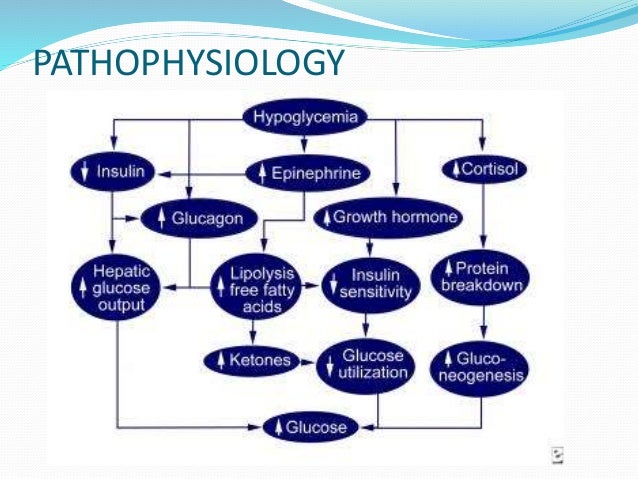

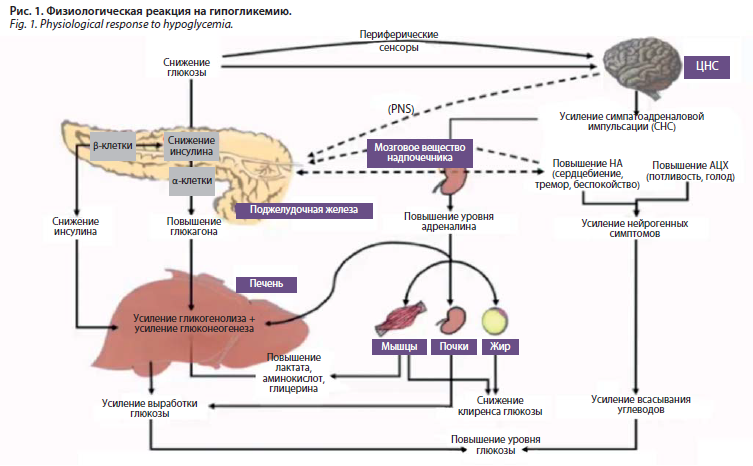

The proposed relationship is supported by observational studies demonstrating a relationship between higher GI/GL and increased incidence of mental illness as well as a potential mechanism. High GI foods result in an increase in blood glucose levels; however, a large compensatory insulin release may result in reactive hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia is associated with an acute increase in epinephrine [13] which contributes to neuropsychiatric symptoms including anxiety [14] and symptoms associated with anxiety such as shakiness, sweating, and heart palpitations. Induction of hypoglycemia in a laboratory setting has a negative impact on mood, hedonic tone, and energy levels as well as an increase in tense arousal [15]. The presence of both anxiety and hypoglycemia symptoms in AB's case, along with their concurrent response to treatment, lends support to the hypothesis that these conditions may be related.

The presence of both anxiety and hypoglycemia symptoms in AB's case, along with their concurrent response to treatment, lends support to the hypothesis that these conditions may be related.

However, it is unclear if other macronutrient or micronutrient changes were, at least in part, responsible for the patient's symptom improvement as she had made several changes concurrently. A recent study found that the individuals in the highest third of GI had lower intake of magnesium, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, omega-3 fatty acids, and protein. Evidence shows that all of these nutrients may play a role in the prevention of mental illness [9].

Evidence suggests that adequate intake of protein may be required in the maintenance of mental health. Dietary protein provides amino acids, eight of which are essential. They cannot be synthesized by the body and must be supplied through the diet. Amino acids form the building blocks of neurotransmitters. For example, the synthesis of serotonin requires the essential amino acid tryptophan and dopamine synthesis requires tyrosine, which is produced from the essential amino acid phenylalanine. The lack of tyrosine and tryptophan leads to deficiencies of the respective neurotransmitters and has been associated with psychiatric disturbances [16].

The lack of tyrosine and tryptophan leads to deficiencies of the respective neurotransmitters and has been associated with psychiatric disturbances [16].

Micronutrient factors are also involved in neurotransmitter synthesis and may be involved in the development of mood and anxiety disorders. As in this case, a diet low in meat may be low in vitamin B12 and a diet low in green vegetables may lack folate. Because both nutrients are important for neurotransmitter synthesis [17], dietary intake may play a role in the development or progression of mood and anxiety disorders.

Dietary fat may also play a role in mental health. The dry weight of the brain is 60 percent fat [18] and low levels of omega-3 fats and cholesterol are significant risk factors for major depression and suicide [19]. Omega-3 fats, which cannot be produced endogenously and must be obtained from the diet, affect the serotonergic system [19] and an inverse relationship between dietary omega-3 fatty acids and anxiety disorders has been demonstrated [7]. Preliminary evidence suggests that omega-3 supplementation may be beneficial in the treatment of anxiety [20].

Preliminary evidence suggests that omega-3 supplementation may be beneficial in the treatment of anxiety [20].

Despite these other potential factors, the concomitant improvement in both anxiety and hypoglycemia symptoms suggests that blood sugar balance may have been contributing to AB's anxiety disorder and that improvement in blood sugar management, as seen in the reduction of hypoglycaemic symptoms, may have been a significant factor in the response to treatment. In conjunction with the observational data [13], this may strengthen our understanding of the relationship between suboptimal blood sugar regulation, GI/GL, and mental illness.

One strength of this case report is that the dietary modifications were the only intervention initiated at the time during which the improvement in symptoms was observed. As well, the brief return to the patient's previous diet and subsequent worsening of symptoms lends support to the likelihood of a causal relationship.

Some limitations exist as well. No validated assessment tool was used to monitor change in anxiety symptoms, only the patient's subjective report. Additionally, the patient was receiving counselling concurrently.

No validated assessment tool was used to monitor change in anxiety symptoms, only the patient's subjective report. Additionally, the patient was receiving counselling concurrently.

Blood sugar balance and dietary GI/GL appear to be important factors in a number of chronic illnesses. A recent meta-analysis found significant positive associations between higher GI or GL and higher incidence of diabetes, coronary heart disease, gallbladder disease, breast cancer, and all diseases combined [21]. As such, implementing a diet lower in refined carbohydrates in the treatment of anxiety may have substantial additional benefit with respect to risk of chronic disease.

Dietary carbohydrates may be significantly related to emotional and cognitive symptoms such as anxiety and difficulty concentrating. Further research into the potential role of GI in the pathogenesis and progression of mental health concerns in addition to the utility of dietary interventions in the treatment of these conditions is warranted.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

1. Martin J. L. R., Sainz-Pardo M., Furukawa T. A., Martin-Sanchez E., Seoane T., Galan C. Review: benzodiazepines in generalized anxiety disorder: heterogeneity of outcomes based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2007;21(7):774–782. doi: 10.1177/0269881107077355. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Lalonde C. D., Van Lieshout R. J. Treating generalized anxiety disorder with second generation antipsychotics. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2011;31(3):326–333. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e31821b2b3f. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Bandelow B., Boerner R. J., Kasper S., Linden M., Wittchen H.-U., Möller H.-J. The diagnosis and treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Deutsches Arzteblatt International. 2013;110(17):300–310. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Opie R. S., O'Neil A., Itsiopoulos C., Jacka F. N. The impact of whole-of-diet interventions on depression and anxiety: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Public Health Nutrition. 2014;18(11):2074–2093. doi: 10.1017/s1368980014002614. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Opie R. S., O'Neil A., Itsiopoulos C., Jacka F. N. The impact of whole-of-diet interventions on depression and anxiety: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Public Health Nutrition. 2014;18(11):2074–2093. doi: 10.1017/s1368980014002614. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Lai J. S., Hiles S., Bisquera A., Hure A. J., McEvoy M., Attia J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary patterns and depression in community-dwelling adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2014;99(1):181–197. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.069880. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Ruusunen A., Lehto S. M., Mursu J., et al. Dietary patterns are associated with the prevalence of elevated depressive symptoms and the risk of getting a hospital discharge diagnosis of depression in middle-aged or older Finnish men. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;159:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.01.020. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Kulkarni A. A. , Swinburn B. A., Utter J. Associations between diet quality and mental health in socially disadvantaged New Zealand adolescents. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2015;69(1):79–83. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.130. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Swinburn B. A., Utter J. Associations between diet quality and mental health in socially disadvantaged New Zealand adolescents. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2015;69(1):79–83. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.130. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Gangswisch J. E., Hale L., Garcia L., et al. High glycemic index diet as a risk factor for depression: analyses from the Women's Health Initiative. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2015;102(2):454–463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Haghighatdoost F., Azadbakht L., Keshteli A. H., et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and common psychological disorders. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2016;103(1):201–209. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.105445. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Cheatham R. A., Roberts S. B., Das S. K., et al. Long-term effects of provided low and high glycemic load low energy diets on mood and cognition. Physiology and Behavior. 2009;98(3):374–379. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.06.015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.06.015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Ingwersen J., Defeyter M. A., Kennedy D. O., Wesnes K. A., Scholey A. B. A low glycaemic index breakfast cereal preferentially prevents children's cognitive performance from declining throughout the morning. Appetite. 2007;49(1):240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.06.009. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Papanikolaou Y., Palmer H., Binns M. A., Jenkins D. J. A., Greenwood C. E. Better cognitive performance following a low-glycaemic-index compared with a high-glycaemic-index carbohydrate meal in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2006;49(5):855–862. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0183-x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Sejling A.-S., Kjær T. W., Pedersen-Bjergaard U., et al. Hypoglycemia-associated changes in the electroencephalogram in patients with type 1 diabetes and normal hypoglycemia awareness or unawareness. Diabetes. 2015;64(5):1760–1769. doi: 10.2337/db14-1359. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.2337/db14-1359. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Paine N. J., Watkins L. L., Blumenthal J. A., Kuhn C. M., Sherwood A. Association of depressive and anxiety symptoms with 24-hour urinary catecholamines in individuals with untreated high blood pressure. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2015;77(2):136–144. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Gold A. E., MacLeod K. M., Frier B. M., Deary I. J. Changes in mood during acute hypoglycemia in healthy participants. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68(3):498–504. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.498. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Sathyanarayana Rao T., Asha M. R., Ramesh B. N., Jagannatha Rao K. S. Understanding nutrition, depression and mental illnesses. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;50(2):77–82. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.42391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Papakostas G. I. , Petersen T., Mischoulon D., et al. Serum folate, vitamin B12, and homocysteine in major depressive disorder, part 2: Predictors of relapse during the continuation phase of pharmacotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65(8):1096–1098. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v65n0811. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Petersen T., Mischoulon D., et al. Serum folate, vitamin B12, and homocysteine in major depressive disorder, part 2: Predictors of relapse during the continuation phase of pharmacotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65(8):1096–1098. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v65n0811. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Chang C.-Y., Ke D.-S., Chen J.-Y. Essential fatty acids and human brain. Acta Neurologica Taiwanica. 2009;18(4):231–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Huan M., Hamazaki K., Sun Y., et al. Suicide attempt and n-3 fatty acid levels in red blood cells: a case control study in China. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;56(7):490–496. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.028. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Su K.-P., Matsuoka Y., Pae C.-U. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in prevention of mood and anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience. 2015;13(2):129–137. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2015.13.2.129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Barclay A. W., Petocz P., McMillan-Price J., et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and chronic disease risk—a meta-analysis of observational studies. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;87(3):627–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Barclay A. W., Petocz P., McMillan-Price J., et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and chronic disease risk—a meta-analysis of observational studies. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;87(3):627–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

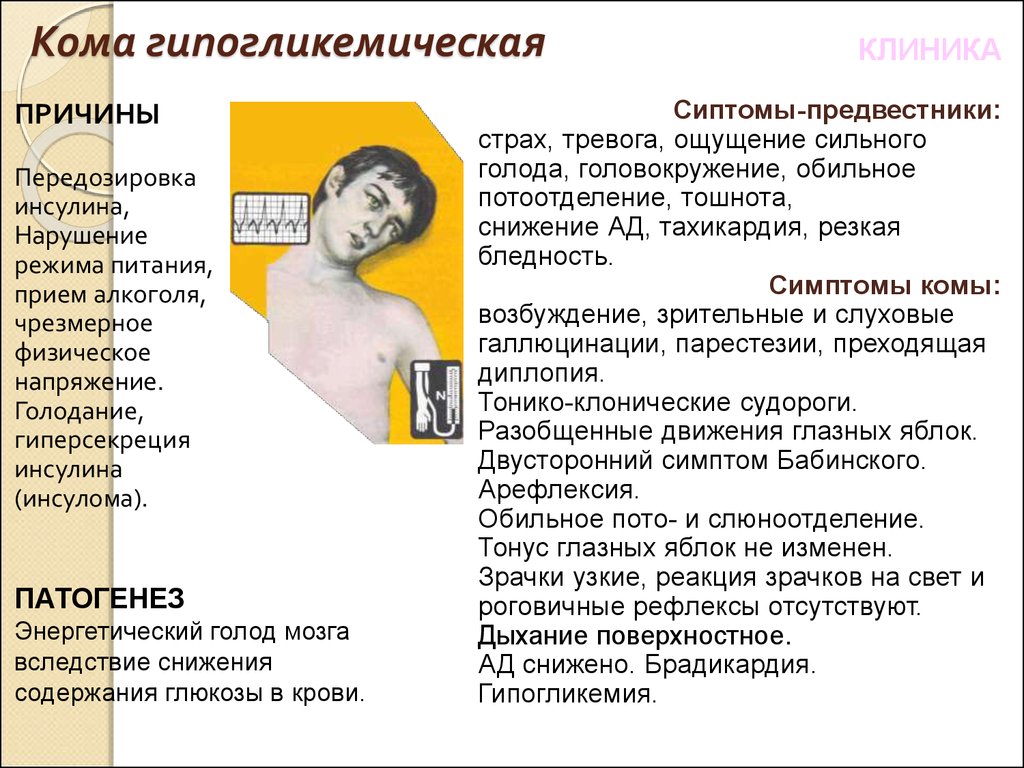

Hypoglycemia - Kirov Clinical Diagnostic Center (former Kirov Clinical Hospital No. 8)

Tuesday, eighteen November 2014

Hypoglycemia -

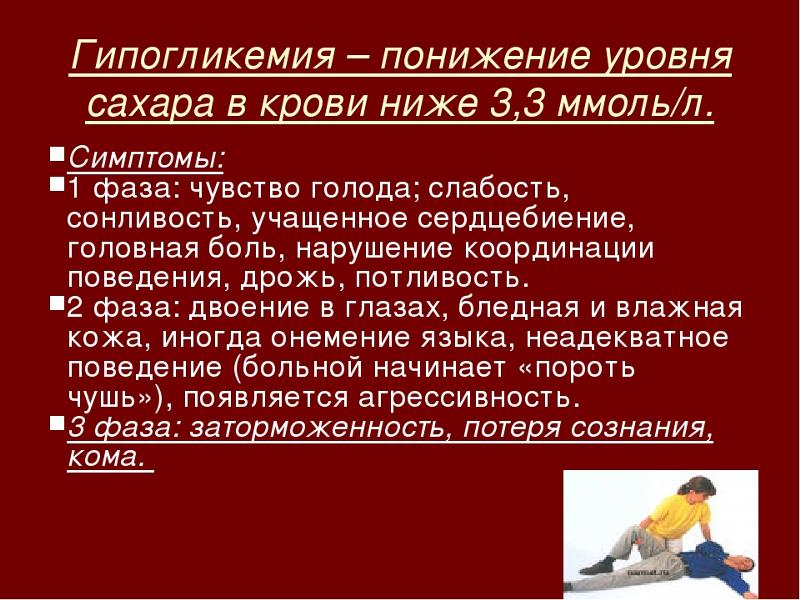

is a condition in which the level of glucose (sugar) in the blood is below normal.

This condition occurs when diabetes is treated with antidiabetic drugs (tablets or insulin).

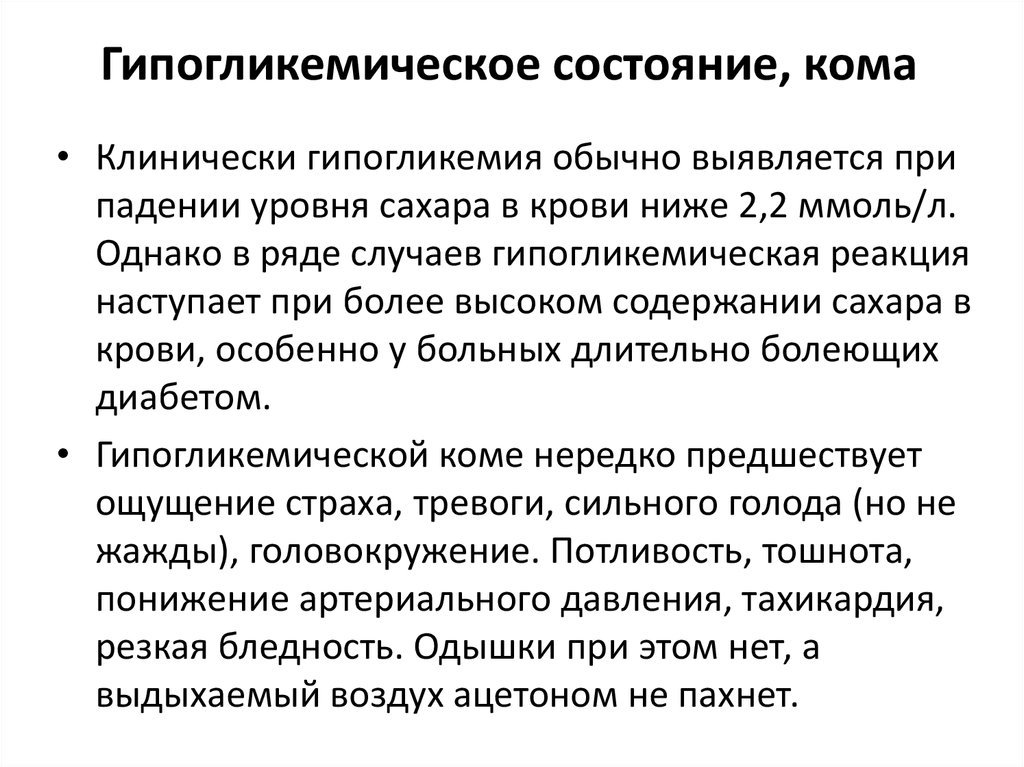

Treatment of hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes mellitus receiving hypoglycemic therapy should be started at plasma glucose < 3.9mmol/l.

Biochemical definition of hypoglycemia: Plasma glucose < 2.8 mmol/l accompanied by clinical symptoms or < 2.2 mmol/l regardless of symptoms.

Mild hypoglycemia is considered to be hypoglycemia without impairment of consciousness, which is stopped by the patient independently. Severe hypoglycemia is manifested by loss of consciousness.

Severe hypoglycemia is manifested by loss of consciousness.

Causes of hypoglycemia:

- Insulin blunders (e.g. double dose) nine0019 clear overdose (incorrect dose) of insulin or tablets

- administering insulin (or taking a glucose-lowering tablet) followed by skipping a meal

- alcohol intake (alcohol temporarily blocks hepatic glucose production)

- physical activity (sufficiently long and intense exercise requires a reduction in the dose of hypoglycemic drugs before and after it)

- failure to relieve mild hypoglycemia (eg, patient does not carry carbohydrates)

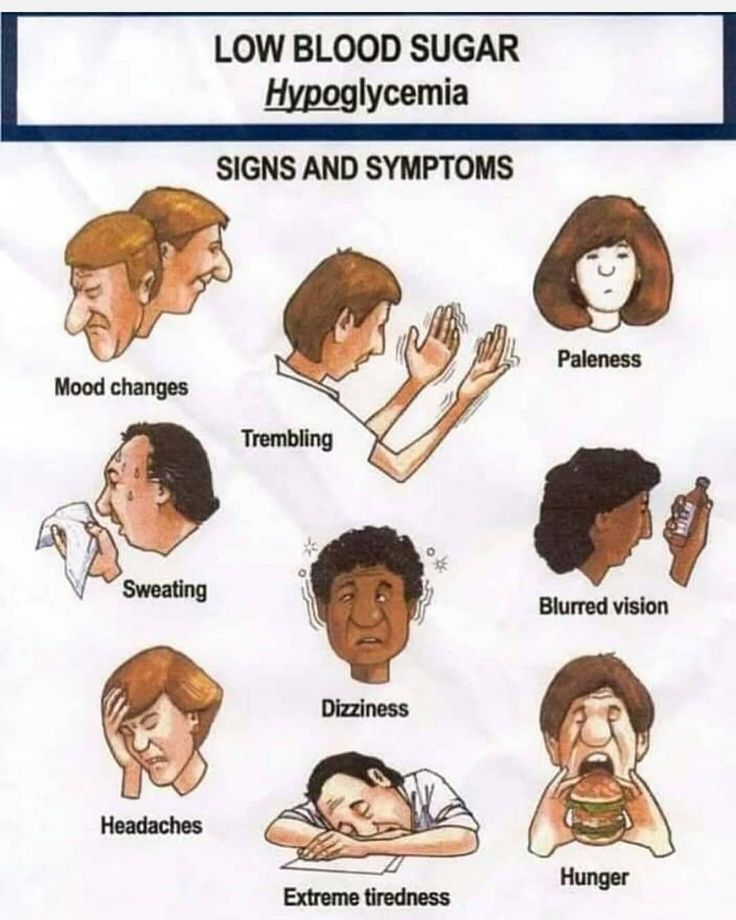

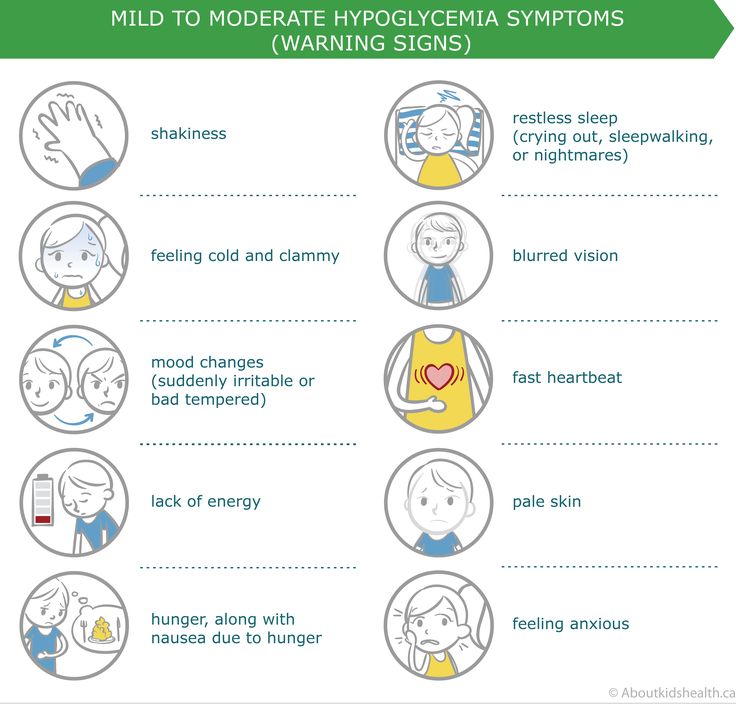

Symptoms of hypoglycemia:

1. Far heartbeat

2. Pallor of the skin

3. Shrees, sweating and humidity of the palms

4. Visual violation (clouding, the appearance of “flies” in the eyes)

5. Weakness , unsteady gait, impaired coordination of movements

6. Feeling of hunger

Feeling of hunger

7. Black in the body

8. Nausea

9. Difficulty thinking, inability to concentrate

10. Tingling in the mouth, numbness of the lips and tongue

11. Headache, dizziness

12. Anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, anxiety aggressiveness, irritability

13. Difficulty speaking, impaired concentration

14. Headache in the morning after waking up may mean hypoglycemia at night!

Night hypoglycemia can be caused:

1. High dose of extended insulin at night

2. Physical exercises after lunch or in the evening without reducing the dose of insulin before bedtime

3. The use of alcohol (the risk of development is preserved for 24 hours after consuming alcohol).

Signs of hypoglycemia in a diabetic patient:

1. sudden pallor

2. “Glazed” or frozen gaze

3. Slurious speech

Slurious speech

4. Strange behavior

5. Unusual excitement, aggressiveness or tearfulness

6. Inability to concentrate

7. Consumer

8. Loss of consciousness. /coma

A decrease in blood sugar can occur very quickly, so if you experience symptoms of hypoglycemia, you should immediately:

1. To determine the level of blood glucose

2. Quickly take one of the following:

1 glass (200 ml) of fruit (grape or apple) juice

1 glass of sweet drink (containing sugar, but no sweetener)

4 teaspoons of sugar in half a cup of water

1-1.5 tablespoons of honey, jam

4-5 large glucose tablets (15 g) or 3-5 lumps of sugar (25-30 min) so should not be used to treat hypoglycemia),

3. Measure blood glucose again

4. If the condition does not improve after 5-10 minutes or the blood sugar level remains too low, take another serving of the above products

5. If the condition improves after 5 minutes and within 30 minutes after the episode of hypoglycemia, a normal meal is not expected, a snack should be eaten (foods containing slowly digestible carbohydrates should be eaten, such as bread, fruit, biscuits, a muffin or cereal bar, a sandwich)

6. If a person has lost consciousness, in no case should you put or pour something into your mouth, but

If a person has lost consciousness, in no case should you put or pour something into your mouth, but

an ambulance must be called immediately!

7. Driving a car: if you develop a state of hypoglycemia, you must wait approximately 45 minutes after you feel better before driving. Do not drive while your blood glucose level is less than 5.0 mmol/L. If you need to cover long distances, you need to stop every 60-90 minutes and check blood glucose levels. If the glucose level is less than 5.0 mmol / l - take sugar, sweets or a sweet drink.

8. It is necessary to inform family members and relatives about the presence of diabetes, about the place of storage of drugs for the relief of hypoglycemia; always have a special card (bracelet or pendant) with you, which says that you suffer from diabetes.

Asymptomatic hypoglycemia is the development of hypoglycemia without feeling the characteristic symptoms. This condition may be due to diabetic damage to the peripheral nervous system, a large number of missed hypoglycemias, and can only be recognized when measuring blood glucose with a glucometer. Therefore, it is very important for patients with diabetes to regularly monitor their blood sugar levels. If the state of hypoglycemia develops asymptomatically, then it is necessary to avoid blood glucose values below 5.0 mmol / l. nine0003

Therefore, it is very important for patients with diabetes to regularly monitor their blood sugar levels. If the state of hypoglycemia develops asymptomatically, then it is necessary to avoid blood glucose values below 5.0 mmol / l. nine0003

How to prevent hypoglycemia:

1. Maintain regular meals and snacks.

2. Regularly adhere to the prescribed diabetes treatment regimen, take hypoglycemic drugs, observe the technique of insulin administration and the order of alternating places for its administration.

3. Regularly measure blood glucose levels with a glucometer (self-monitoring of glycemia), additionally before and after exercise.

4. Take extra food before and during unplanned or prolonged physical activity. nine0003

90,000 Alarm and hypoglycemia: symptoms, communication and much more

A little concern for hypoglycemia or low blood sugar is normal. But some people with diabetes develop severe symptoms of anxiety about episodes of hypoglycemia.

The fear may become so strong that it interferes with their daily lives, including work or school, family and relationships. Fear can even interfere with their ability to properly manage diabetes. nine0003

This excessive worry is known as anxiety. Fortunately, there are ways to manage the anxiety associated with hypoglycemia.

Read on to learn more about the link between diabetes, anxiety and hypoglycemia and what steps you can take to manage your symptoms.

What is hypoglycemia?

When you take diabetes medications, such as insulin or medications that increase insulin levels in the body, your blood sugar levels drop. nine0003

Reducing blood sugar levels after meals is important for managing diabetes. But sometimes blood sugar levels can drop too low. Low blood sugar is also called hypoglycemia.

Blood sugar is considered low when it falls below 70 mg/dl. If you have diabetes, you need to check your blood glucose frequently throughout the day, especially when you exercise or skip meals.

Immediate treatment of hypoglycemia is necessary to prevent the development of serious symptoms. nine0003

The symptoms of hypoglycemia include:

- Smissance

- Fast pulse

- Pale leather

- Tire vision

- Headache

If not treated, hypoglycemia can lead to more serious symptoms, including:

To manage hypoglycemia, you will need a small snack of about 15 grams of carbohydrates. Examples include:

- Lollipop

- juice

- dried fruit

In more severe cases, medical intervention may be required.

What is anxiety?

Anxiety is a feeling of unease, worry, or fear in response to stressful, dangerous, or unfamiliar situations. Anxiety is normal before an important event or in an unsafe situation.

Uncontrollable, excessive and persistent anxiety can interfere with your daily life. When this happens over a long period of time, it is called an anxiety disorder. nine0003

When this happens over a long period of time, it is called an anxiety disorder. nine0003

- Nervousness

- Inability to manage anxiety thoughts

- Problems with relaxation

- restlessness

- Insomnia

- irritability

- Problems 900,

- Constant fear, something bad

- Masts

- upset stomach

- rapid pulse

- avoidance of certain people, places or events

Diabetes and anxiety

It is very important to balance medication with food intake to keep diabetes under control. Failure to do so can lead to many problems, including hypoglycemia.

Hypoglycemia is accompanied by a number of unpleasant and uncomfortable symptoms.

After you have experienced a hypoglycemic episode, you may begin to worry about the possibility of future episodes. For some people, this anxiety and fear can become intense.

This is known as fear of hypoglycemia (FOH). This is similar to any other phobia, such as fear of heights or snakes. nine0003

nine0003

If you have severe FOH, you may become overly cautious or overly cautious about checking your blood glucose.

You may also try to keep your blood glucose above the recommended range and worry obsessively about those levels.

Research has shown a strong link between anxiety and diabetes.

A 2008 study found that clinically significant anxiety is 20 percent higher among Americans with diabetes compared to Americans without diabetes. nine0003

Diagnosis of diabetes can be alarming. You may worry that illness will require unwanted lifestyle changes or that you will lose control of your health.

In addition, dietary changes, complex medications, exercise, smoking cessation, and blood glucose monitoring associated with diabetes treatment can increase anxiety.

Managing Anxiety

There are many effective treatment options for anxiety. If anxiety about hypoglycemia is affecting your daily life, ask your doctor about the following. nine0003

nine0003

Get information about your risk of hypoglycemia

The better you understand your risk of hypoglycemia and the steps you can take to prepare for an episode, the easier it will be for you to manage your fears.

Talk to your doctor about your overall risk assessment. Together you can develop a plan to prepare for a possible episode of hypoglycemia.

You can ask your doctor about buying a glucagon kit in case of an emergency.

Teach family and friends how to use the kit if you are having a severe episode of low blood sugar. Knowing that others are looking after you can help you calm down and reduce your anxiety. nine0003

Blood Glucose Training

Blood Glucose Training (BGAT) is designed to help people with diabetes understand how insulin, diet choices, and physical activity levels affect their blood glucose levels .

This type of workout will help you better manage your health and blood glucose levels. In turn, this can help you not worry about things going wrong.

Psychological counseling

Talking to a psychologist or psychiatrist can also help. These medical professionals can make the correct diagnosis and prescribe treatment. This may include medications and cognitive behavioral therapy.

One approach known as graded exposure therapy has proven to be an effective way to deal with fears and manage anxiety.

Exposure therapy gradually introduces you to the situation you fear in a safe environment.

For example, if you were obsessively checking your blood glucose, your counselor might suggest that you delay checking your glucose for one minute. You gradually increase this time to 10 minutes or more each day. nine0003

Continuous Glucose Monitors

If you find yourself obsessively checking your blood glucose, a continuous glucose meter (CGM) can help.

This device measures your glucose levels at normal times during the day, including while you sleep. The CGM gives an alarm if the glucose level drops too low.

Physical activity

Physical activity can be very relaxing. Even a short walk or bike ride can be good for your mental health. nine0003

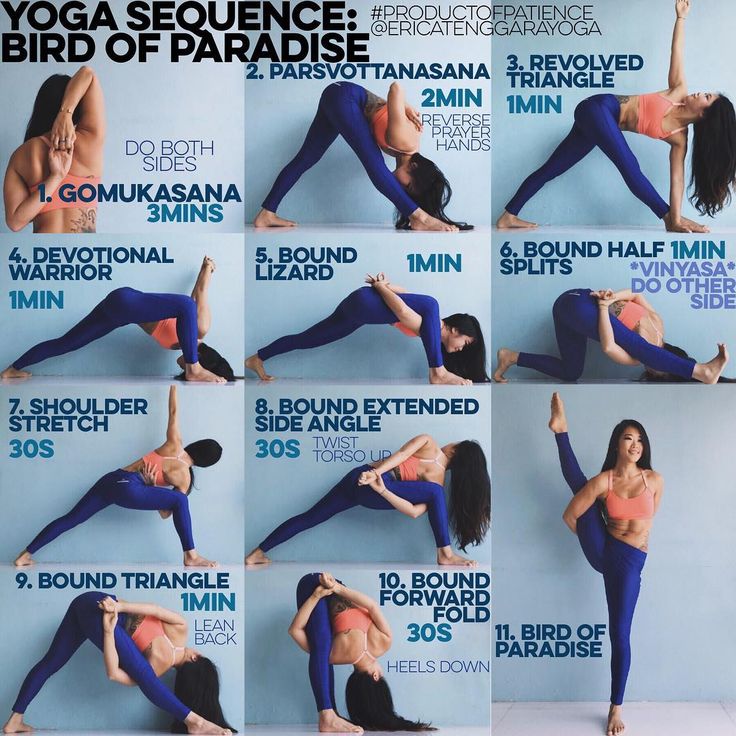

Yoga is a good way to exercise and calm your mind at the same time. There are many types of yoga, and you don't have to do it every day to see the benefits.

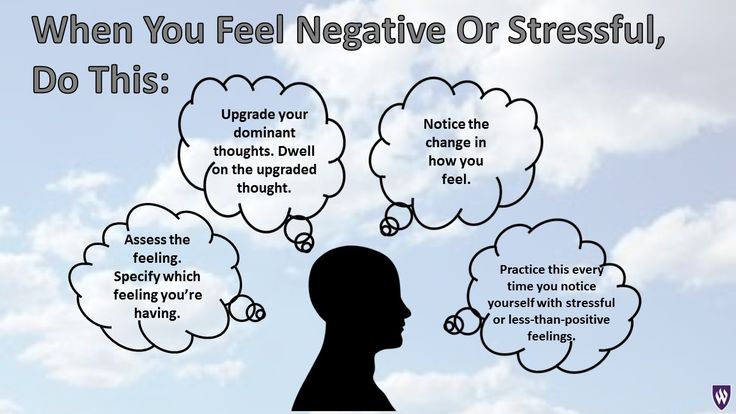

Mindfulness

Instead of ignoring or fighting anxiety, it's best to acknowledge and check your symptoms and let them go.

This does not mean that you should let the symptoms take over, but rather that you have them and that you can control them. This is called mindfulness. nine0003

When you feel anxious, try the following:

- observe your symptoms and emotions

- acknowledge your feelings and describe them out loud or silently

- take a few deep breaths

- tell yourself that strong feelings will pass

If you have diabetes, it is normal to be a little worried about possible hypoglycemia.