Yoga for ptsd

A Holistic Treatment Pathway For PTSD

Contents

- Yoga Therapy for Trauma and PTSD

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Background

- The Physiological Characteristics of PTSD

- Why Use Yoga as an Adjunct Treatment for PTSD?

Thought to be caused by a dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, PTSD affects the survivors of trauma. With growing evidence to suggest that yoga can aid in PTSD recovery, this guide offers an introductory exploration of yoga’s potential as an adjunct treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder.

It’s an unfortunate fact that many people will encounter significant trauma at some point during their lives. For most, the weeks or months of upset in the aftermath of a traumatic event will eventually pass, and they will be able to move on. For others, however, the development of post-traumatic stress disorder stands in the way of a return to normal life.

Yoga Therapy for Trauma and PTSD

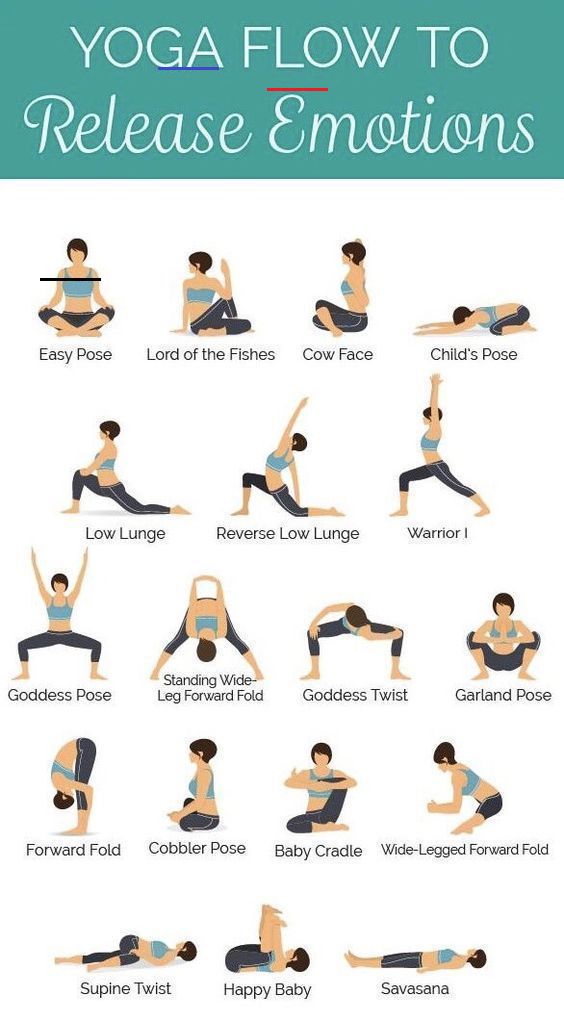

Post traumatic stress disorder is a challenging illness that can come to dominate the lives of those it affects, and a variety of strategies are often required to manage the emotional and physical symptoms that define it. The use of evidence-based techniques from yoga and mindfulness to aid in the recovery of PTSD is a promising area of yoga therapy, where emerging scientific research points toward several mechanisms through which yoga can reduce symptoms of PTSD.

“The fact is, all of us are living with the invisible wounds of some kind of war. Yoga helps you to let go of the things that don’t serve you anymore.”

Dan Nevins, yoga ambassador and US Army veteran

Yoga can be such an efficacious treatment for PTSD because it works with both the mind and the body, while also helping to forge a sense of safe community from which individuals can draw comfort and support. Alongside medication and psychotherapy, yoga therapy can be a valuable part of a person’s medical care – as well as a self-care tool they can fall back on in their own time.

By combining a comprehensive knowledge of the neuroscience, psychology and physiology of trauma with yogic techniques, yoga therapists can gently guide PTSD sufferers towards recovery in an informed and safe way. Furthermore, they can work within the framework of a wider treatment plan and help individuals fully engage with counselling or therapy.

Furthermore, they can work within the framework of a wider treatment plan and help individuals fully engage with counselling or therapy.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Background

“After a traumatic experience, the human system of self-preservation seems to go onto permanent alert, as if the danger might return at any moment.”

Judith Lewis Herman, psychiatrist

Most of us are introduced to the idea of post-traumatic stress disorder in the context of the military. While there are written descriptions of symptoms that are analogous to our modern understanding of PTSD as far back as the Ancient Greeks, the illness first entered popular consciousness through the phrase “shell shock” – a term invented to characterise the long-term effect trench warfare had on some soldiers during the First World War.

Since then, understanding and sympathy around PTSD has grown. Anyone who is frequently exposed to life-threatening or traumatic situations (such as soldiers, paramedics and firefighters) is at risk of developing PTSD, but it can also affect those who have lived through traumatic incidents such as violent/sexual assault, serious accidents or a difficult labour.

PTSD is thought to affect one in three people who experience trauma. It is still unknown why some individuals will develop this illness while others do not, but it is thought that inadequate support in the immediate aftermath of experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event may elevate the risk.

The symptoms of PTSD include:

- Re-experiencing the traumatic event through flashbacks, nightmares and physical sensations.

- Avoidance of anything that reminds the sufferer of the event. They will also push away feelings and memories, and can experience emotional numbness and dissociation.

- Hyperarousal and constantly feeling “on edge”, often associated with hypervigilance, irritability and insomnia.

- Co-occuring issues such as anxiety, depression, alcohol/substance misuse and relationship breakdown.

A variant form of PTSD can also appear when people have lived through ongoing stress or fear, which is defined as complex post-traumatic stress disorder (or c-PTSD). People are more likely to develop c-PTSD if they endured trauma at an early age, have experienced multiple traumas or if their trauma lasted a long time, such as in cases of childhood abuse.

People are more likely to develop c-PTSD if they endured trauma at an early age, have experienced multiple traumas or if their trauma lasted a long time, such as in cases of childhood abuse.

The Physiological Characteristics of PTSD

When we experience or witness a life-threatening, violent or otherwise traumatic event, our nervous system will activate a defensive biobehavioral response – an instinctive “survival mode” – which can manifest itself in two disparate ways:

The fight/flight response, where an individual’s sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is activated in order to equip the body with the means to fight or run away from a threat.

The shutdown/freeze response, which is the activation of an evolutionarily older branch of the vagus nerve. This creates stillness (in order to avoid detection or play dead) and can induce dissociation.

While the trauma itself was likely to have been unsafe, uncontrollable and unpredictable, a person may also perceive their body’s response to it as equally dangerous and unstable. The dissociation and inability to move induced by the “freeze” response can be extremely disturbing, while the rush of energy and shutdown of higher cognitive functioning associated with fight/fight may be remembered as a frightening loss of control.

The dissociation and inability to move induced by the “freeze” response can be extremely disturbing, while the rush of energy and shutdown of higher cognitive functioning associated with fight/fight may be remembered as a frightening loss of control.

This trauma – and the bio-behavioural response it provokes – can be overwhelming, leading to the memory of the event and its attendant images, sensations and emotions becoming dissociated from normal conscious experience. It is then subsequently re-experienced through flashbacks, nightmares and other sensations, accompanied by the defensive reactions the trauma originally triggered.

For those living with PTSD, the dysregulation of their body’s defensive response (1) means they release higher levels of stress hormones, and react even in benign situations as if they are under threat. Experiencing a chronic activation of the fight/flight response, they exhibit hyperactivity in the amygdala (the area of the brain that meditates fear) and changes in the hippocampus, a part of the brain associated with memory and emotions. They may also experience anhedonia (the inability to feel pleasure) and dissociation.

They may also experience anhedonia (the inability to feel pleasure) and dissociation.

Why Use Yoga for Trauma as an Adjunct Treatment for PTSD?

“Neuroscience research shows that the only way we can change the way we feel is by becoming aware of our inner experience and learning to befriend what is going inside ourselves.”

Bessel A. Van Der Kolk, psychiatrist and author.

Trauma affects individuals physiologically, cognitively and emotionally, with the ramifications felt in both mind and body. Yoga therapy acts across all these domains, leading those with PTSD to increasingly turn to this mind-body practice in their journey towards recovery.

A key challenge for someone suffering with post-traumatic stress disorder is the inability to regulate their physiological survival response. As an instinctive and unconscious reaction, a person can rationally know they aren’t in danger while still experiencing hypervigilance and even panic. Achieving stabilization of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) through yoga can help people engage with counselling and psychotherapy, allowing them to begin to process their trauma.

Achieving stabilization of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) through yoga can help people engage with counselling and psychotherapy, allowing them to begin to process their trauma.

Yoga therapy may help people return to a baseline physiological state more quickly after a distressing memory is triggered. It’s thought that regular yoga practice trains the ANS to be more dynamically adaptive (2), and that mindfulness meditation (a component of yoga) can lead to positive changes in neural functioning, including the reduction in size of the amygdala and increased hippocampal volume (3).

Trauma survivors can experience a disconnect between mind and body, and exhibit a lack of body awareness. This is both a form of avoidance as they seek to circumvent any feelings or sensations that remind them of their trauma, and a result of the hyperarousal that renders bodily reactions unpredictable and disconnected from conscious thought.

Body awareness is an intrinsic part of yoga, and can help people “build skills in tolerating and modulating physiologic and affective states that have become dysregulated by trauma exposure” (4), which is associated with lesser symptom severity. In a yoga class, people can learn to better cope with the defensive responses that proceed re-experiencing, as traumatic memories (or other triggers) arise in the internal and external environment of nonreactive mindful awareness (5).

In a yoga class, people can learn to better cope with the defensive responses that proceed re-experiencing, as traumatic memories (or other triggers) arise in the internal and external environment of nonreactive mindful awareness (5).

As people with PTSD are physiologically primed for threat, their ability to socialise and cope well around others can be severely diminished, and even their closest relationships can become strained. A yoga class gives them the opportunity to socialise in a self-directed and natural way, finding support among peers without the expectation to engage beyond their current comfort zone.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is an illness that often requires an individualised and multifaceted response, and no two people’s experience of trauma will be the same. Yoga therapy is effective tool that addresses PTSD on a variety of levels, allowing people to move forward and find a new life after trauma.

To find out more about the science behind yoga for PTSD, order your copy of Yoga for Mental Health.

(1) https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/11/071107211450.htm

(2) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22365651

(3) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3004979/

(4) https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/acm.2014.0407

(5) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178112003630

A randomized controlled trial of the influence of yoga for women with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder | Journal of Translational Medicine

- Research

- Open Access

- Published:

- Lei Yi1,

- Yunling Lian2,

- Ning Ma1 &

- …

- Ni Duan1

Journal of Translational Medicine volume 20, Article number: 162 (2022) Cite this article

-

1561 Accesses

-

1 Citations

-

Metrics details

Abstract

Background

Survivors in motor vehicle accident (MVA) may have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Yoga is a complementary approach for PTSD therapy.

Yoga is a complementary approach for PTSD therapy.

Methods

This randomized controlled trial explored whether yoga intervention has effects on reducing the symptoms of PTSD in women survived in MVA. Participants (n = 94) were recruited and randomized into control group or yoga group. Participants attended 6 45-minuite yoga sessions in 12 weeks. Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) and Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) were used to assess psychological distress.

Results

Post-intervention IES-R total score of yoga group was significantly lower than that of control group (p = 0.01). At both post-intervention and 3-months post intervention, the DASS-21 total scores of yoga group were both significantly lower than those of control group (p = 0.043, p = 0.024). Yoga group showed lower anxiety and depression level compared to control group at both post-intervention (p = 0.033, p < 0.001) and post-follow-up (p = 0. 004, p = 0.035). Yoga group had lower levels of intrusion and avoidance compared to control group after intervention (p = 0.002, p < 0.001).

004, p = 0.035). Yoga group had lower levels of intrusion and avoidance compared to control group after intervention (p = 0.002, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Results illustrate that yoga intervention may alleviate anxiety and depression and improve the symptoms of PTSD in women with PTSD following MVA.

Introduction

Having the experience of motor vehicle accident (MVA) will trigger the generation of psychosocial impacts and psychological disorders [1]. The psychosocial impacts caused by MVA include disability, chronic pain, trauma, and loss of income [2]. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) and are two major psychological disorders in MVA [3]. Research has reported that in MVA survivors, 21–67% of them suffer depressive, 47% have driving phobia, and 20–40% suffer PTSD [4]. Up to at least 12 months post-MVA, the incidence of MDD and PTSD remain elevated [5]. A systematic review has demonstrated that in people sustaining MVA, the median occurrence of PTSD was 30% after 1 month and had a declining trend to 15% after 12 months [6]. Another study illustrated that the rate of MVA survivors with probable PTSD was around 30% within 4 weeks and 20% after 6 months [7]. PTSD are associated with a dysregulation of both neuroendocrine system and renin angiotensin system [8].

Another study illustrated that the rate of MVA survivors with probable PTSD was around 30% within 4 weeks and 20% after 6 months [7]. PTSD are associated with a dysregulation of both neuroendocrine system and renin angiotensin system [8].

To reduce the risk of psychological distress caused by MVA, interventions are performed and proved to be effective. Cognitive behavior therapy which enhances the adaptive psychological, social, and behavioral skills of survivors is effective in the improvement of psychological symptoms after MVA [9].

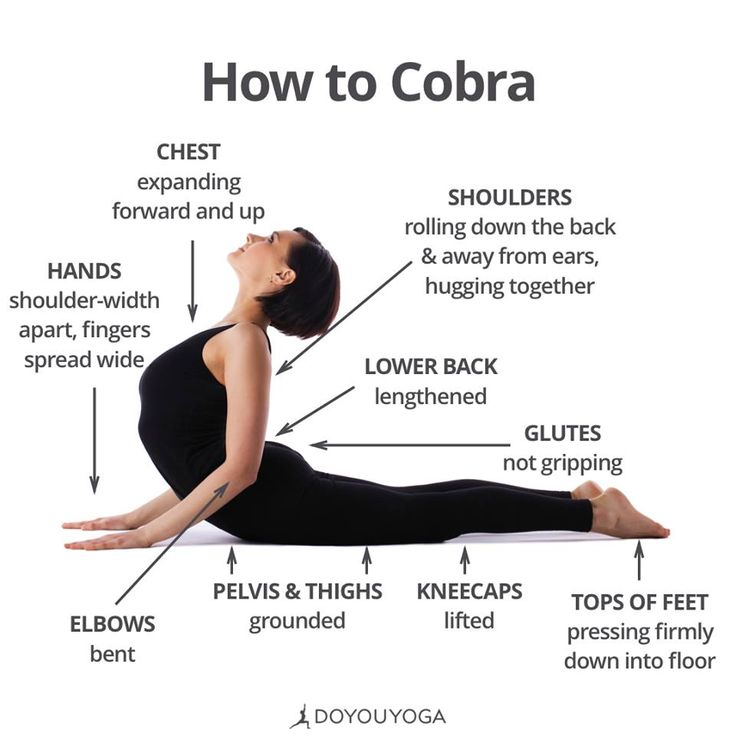

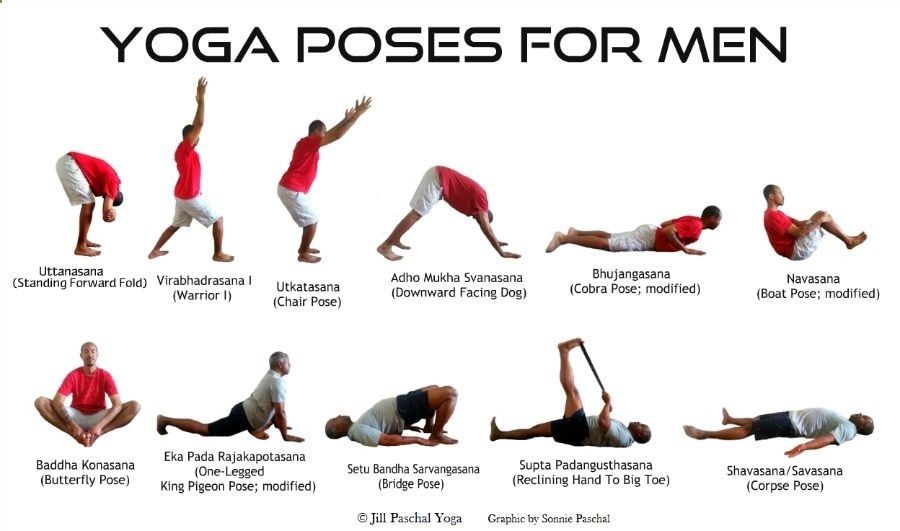

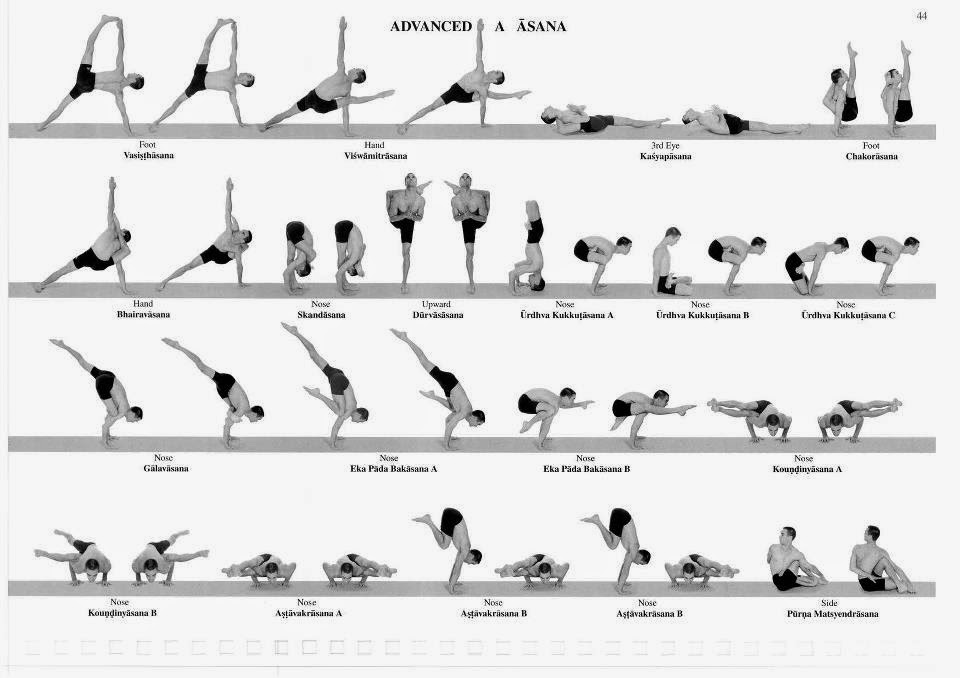

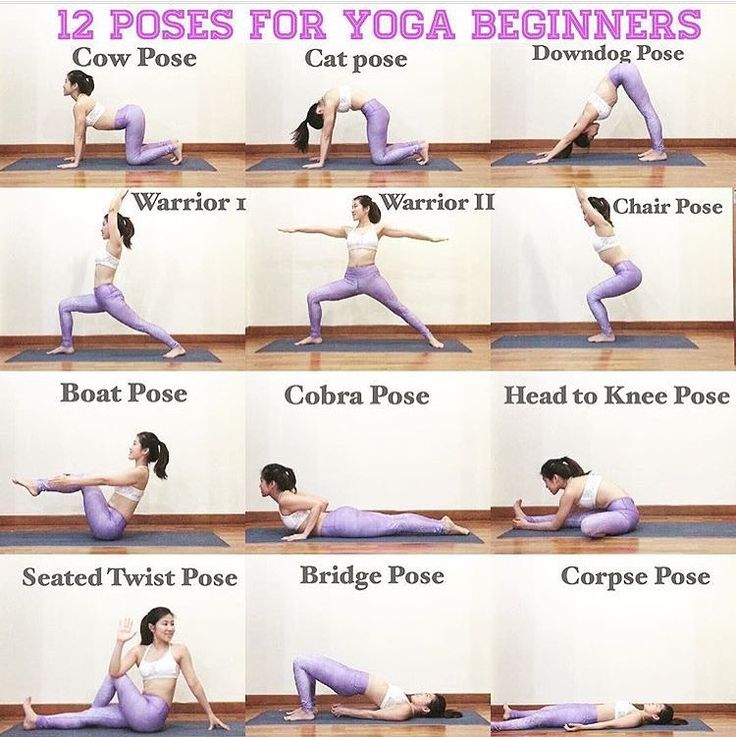

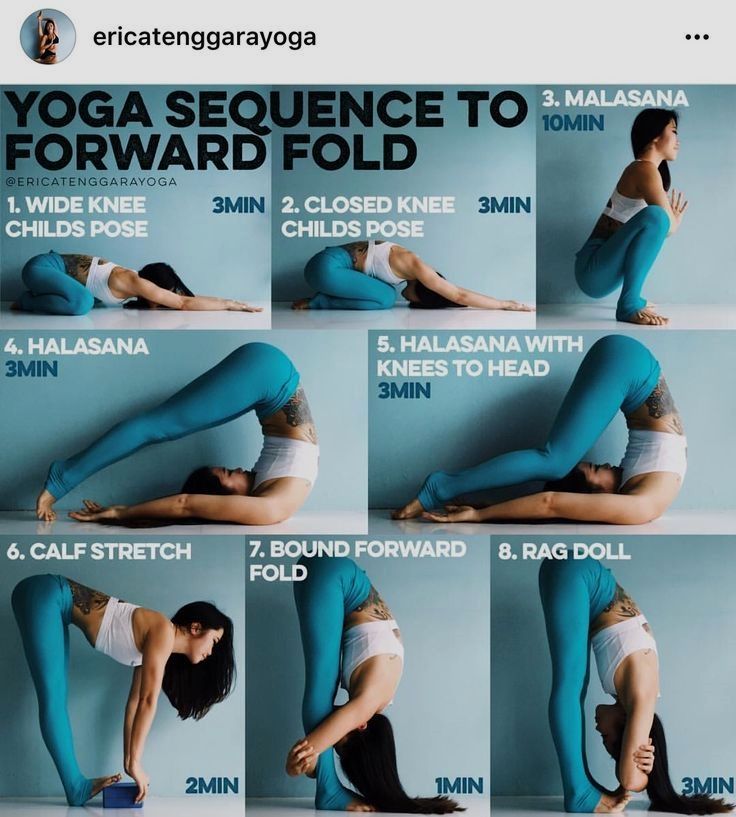

As a non-pharmacologic strategy, yoga combines the practice of meditation, physical postures, and breathing [10]. Recently, yoga has been utilized to reduce stress and improve psychological disorder [11]. In a number of populations, yoga is effective in reducing the PTSD symptoms [12]. It has been proved that in PTSD patients, the performance of yoga reduces PTSD-caused physiological arousal and inhibits PTSD pathology through improving somatic regulation and body awareness [13].

Since yoga is able to ameliorate psychological and physical conditions of PTSD patients, this randomized controlled trial aimed to evaluate the effect of yoga on reducing symptoms of PTSD in women after MVA.

Methods

Participants

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qingdao Mental Health Center. Eligible participants were adult women diagnosed with MVA-related PTSD that happened at least 3 months ago. PTSD was diagnosed by meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition (DSM-IV) PTSD criterion A1 for a traumatic event. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Having organic mental disorder, symptomatic bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder, or schizophrenia; (2) Having brain surgery history, brain damage, or neurological problems; (3) Having substance abuse or currently suicidal.

Procedures

Figure 1 showed the flow for recruitment, intervention, and assessment processes. A total of 165 individuals were assessed for eligibility, of whom 94 were included in this trail. After completing baseline measures, these 94 patients were randomly divided into yoga group (n = 47) and control group (n = 47) through a web-based randomization system. Participants in yoga group attended 6 45-minuite yoga sessions in 12 weeks. In the control group, yoga sessions were replaced by exchanging daily life experiences and playing board games in 12 weeks. After intervention and 3-month follow-up, participants in both groups were assessed. For the 47 participants in yoga group, 3 lost contact, 7 withdrew, and 37 completed. 39 participants in control group completed this trail after 8 participants withdrew.

After completing baseline measures, these 94 patients were randomly divided into yoga group (n = 47) and control group (n = 47) through a web-based randomization system. Participants in yoga group attended 6 45-minuite yoga sessions in 12 weeks. In the control group, yoga sessions were replaced by exchanging daily life experiences and playing board games in 12 weeks. After intervention and 3-month follow-up, participants in both groups were assessed. For the 47 participants in yoga group, 3 lost contact, 7 withdrew, and 37 completed. 39 participants in control group completed this trail after 8 participants withdrew.

CONSORT flow diagram

Full size image

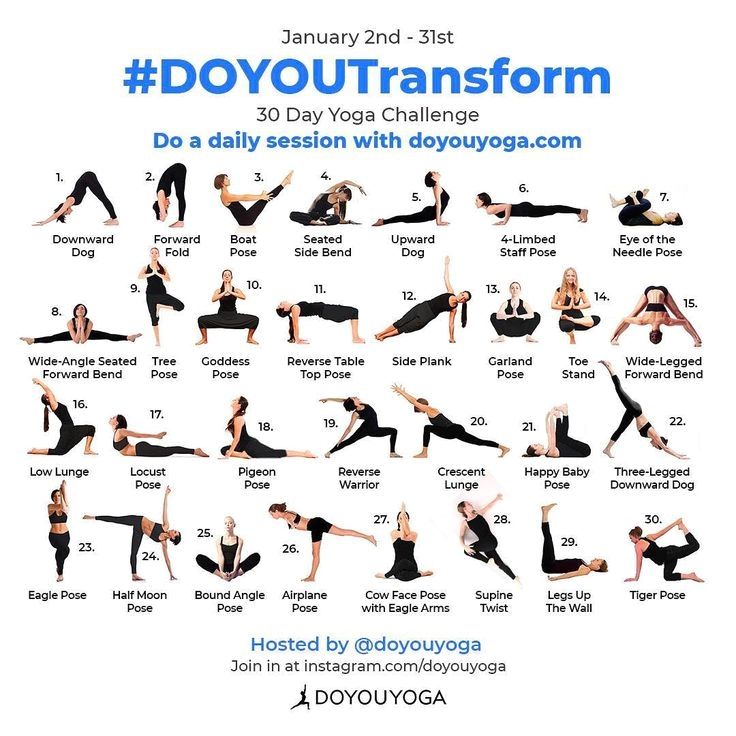

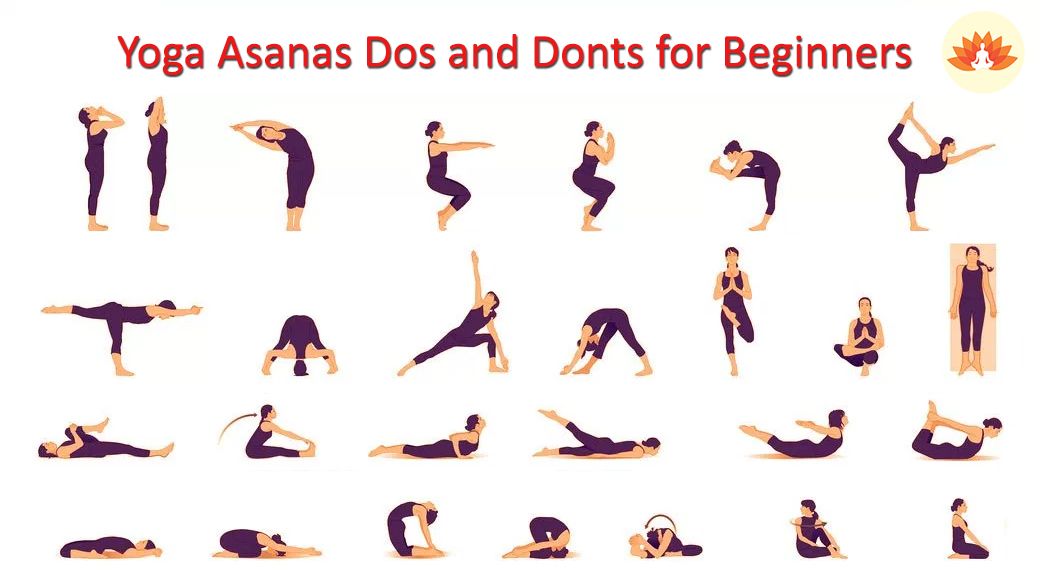

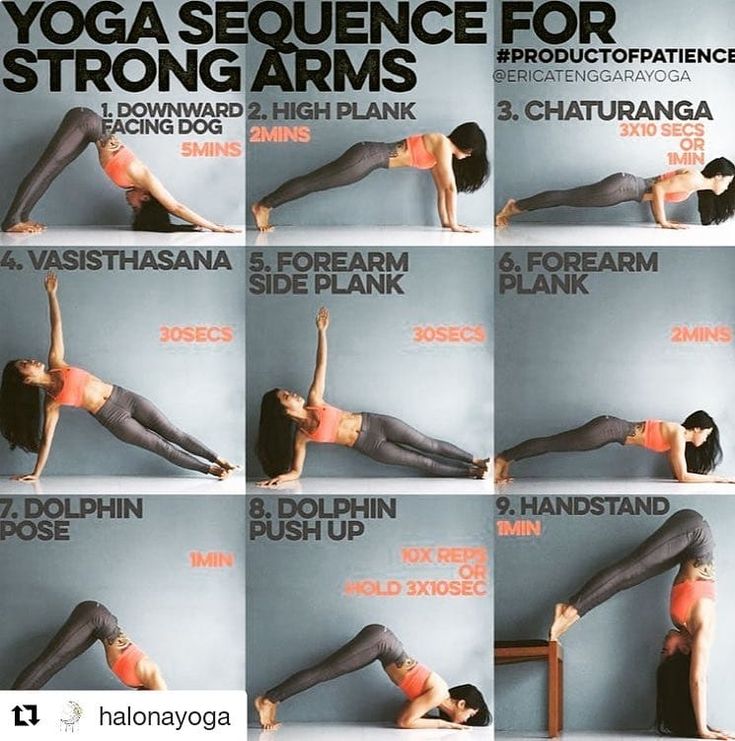

Intervention

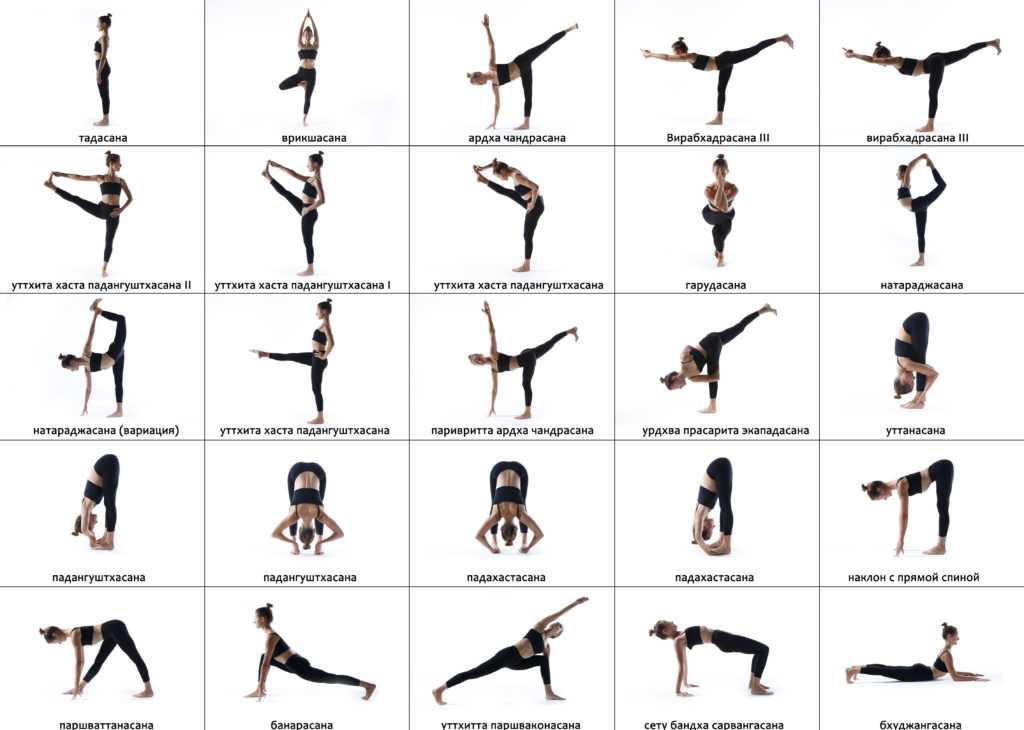

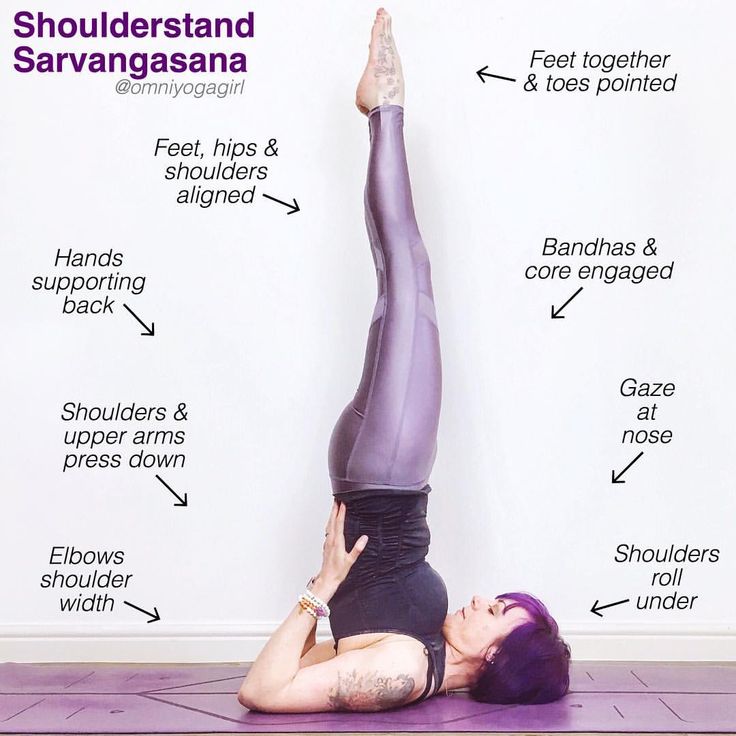

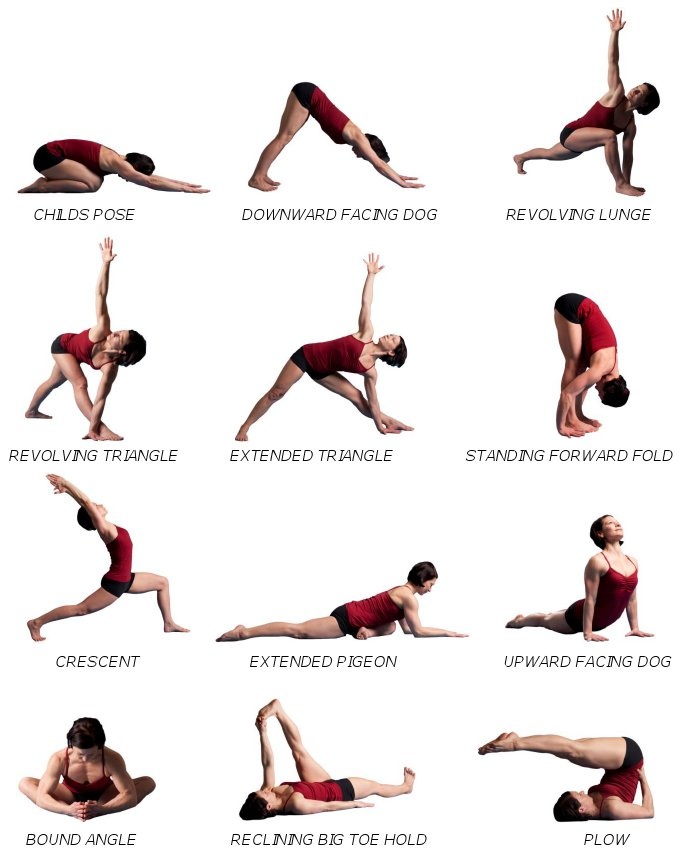

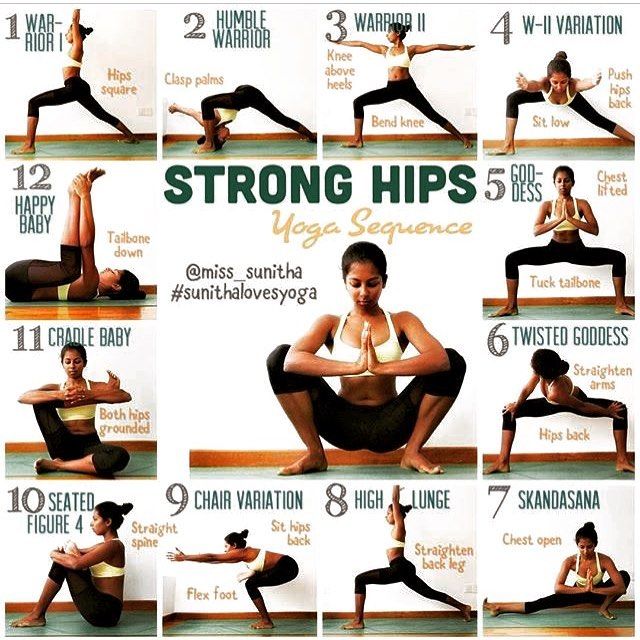

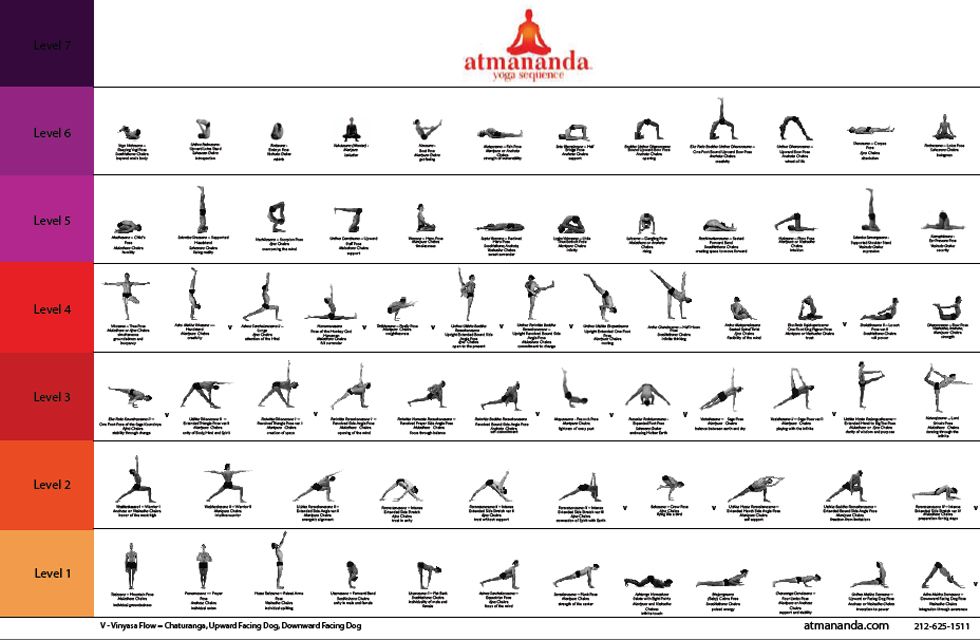

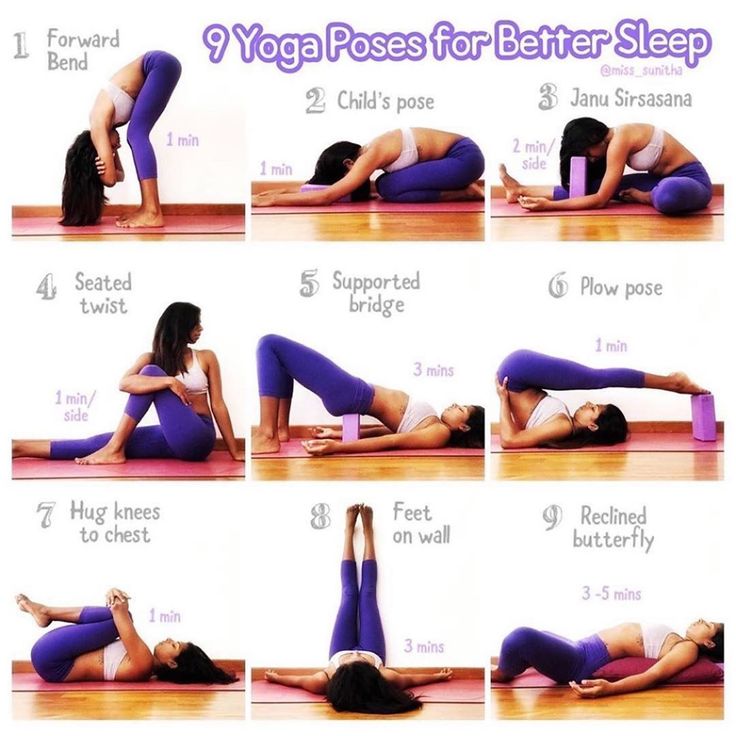

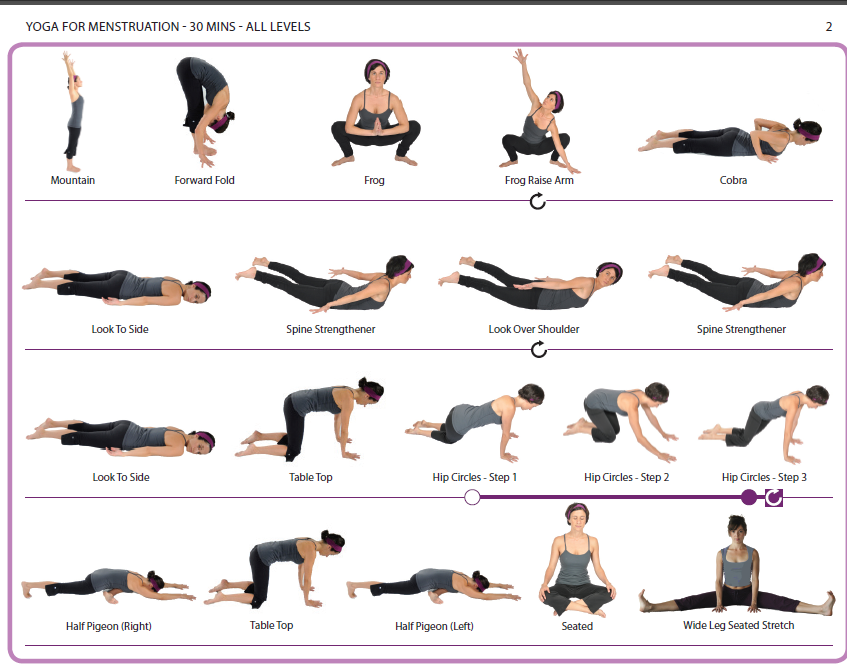

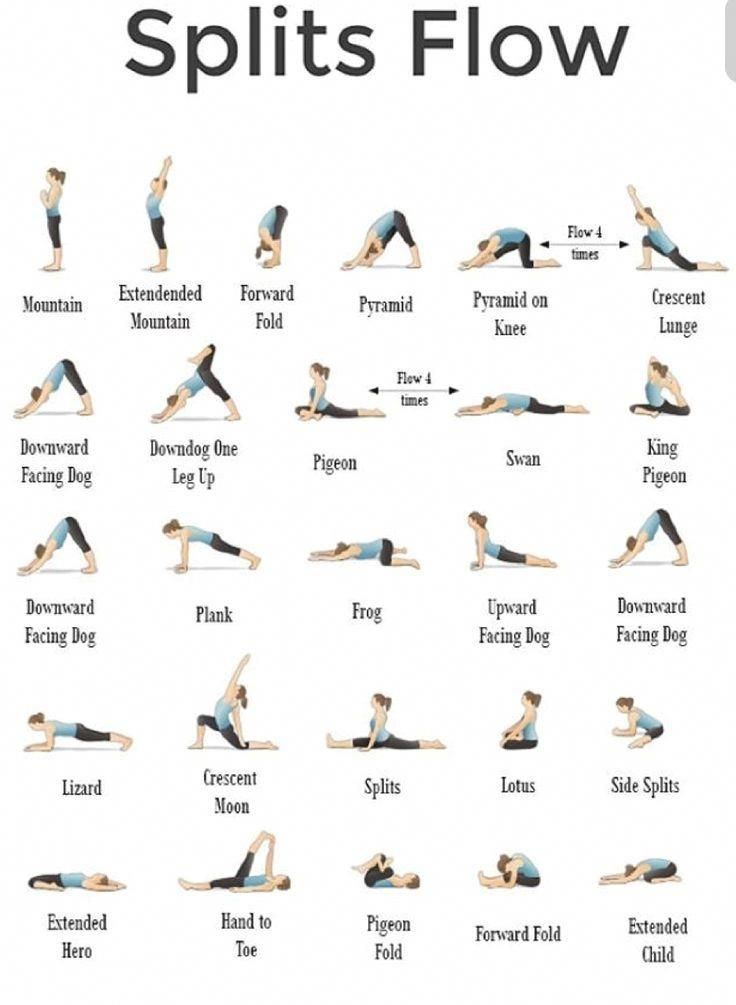

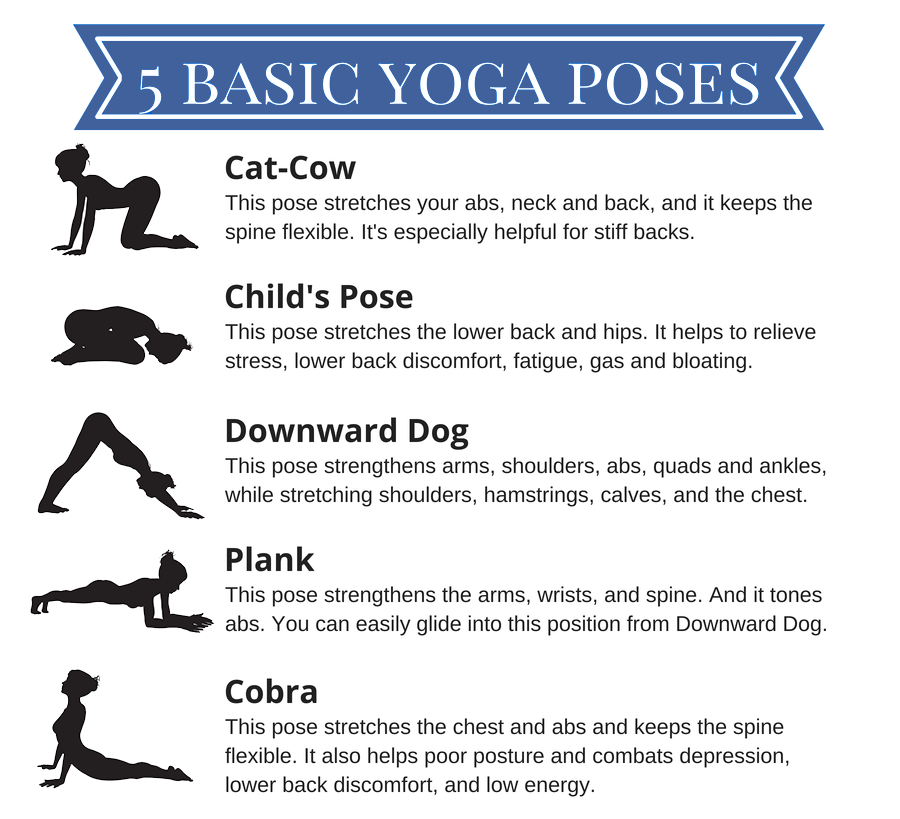

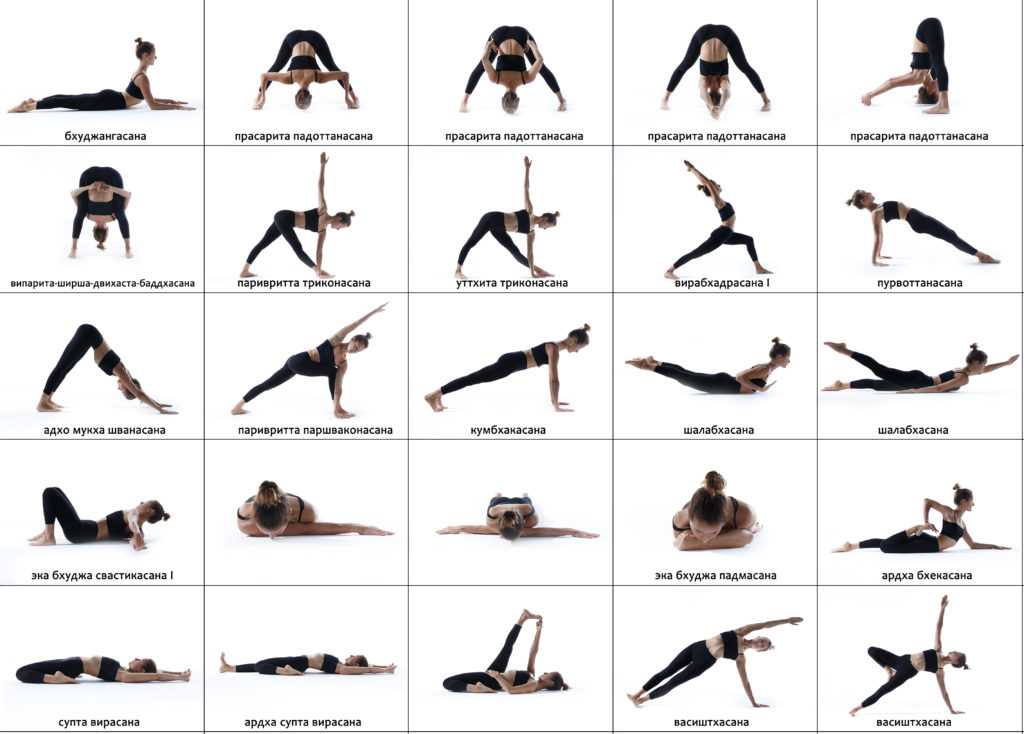

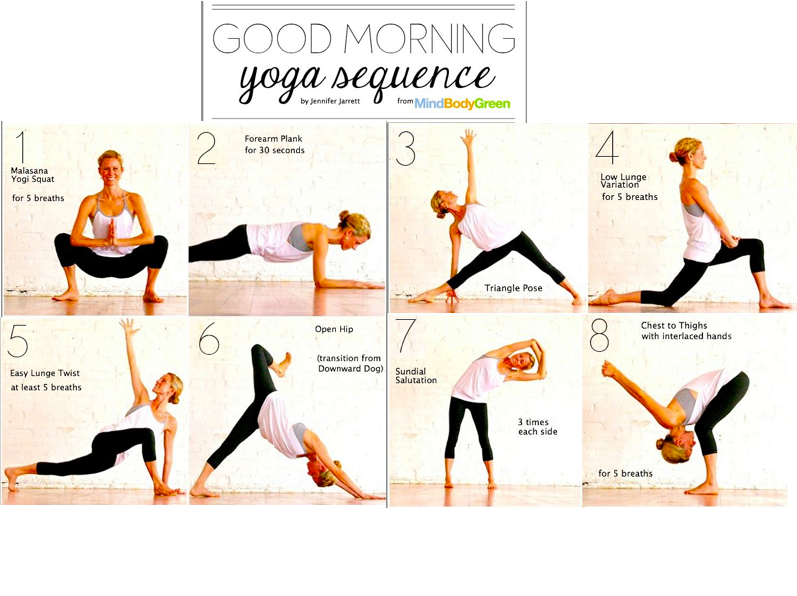

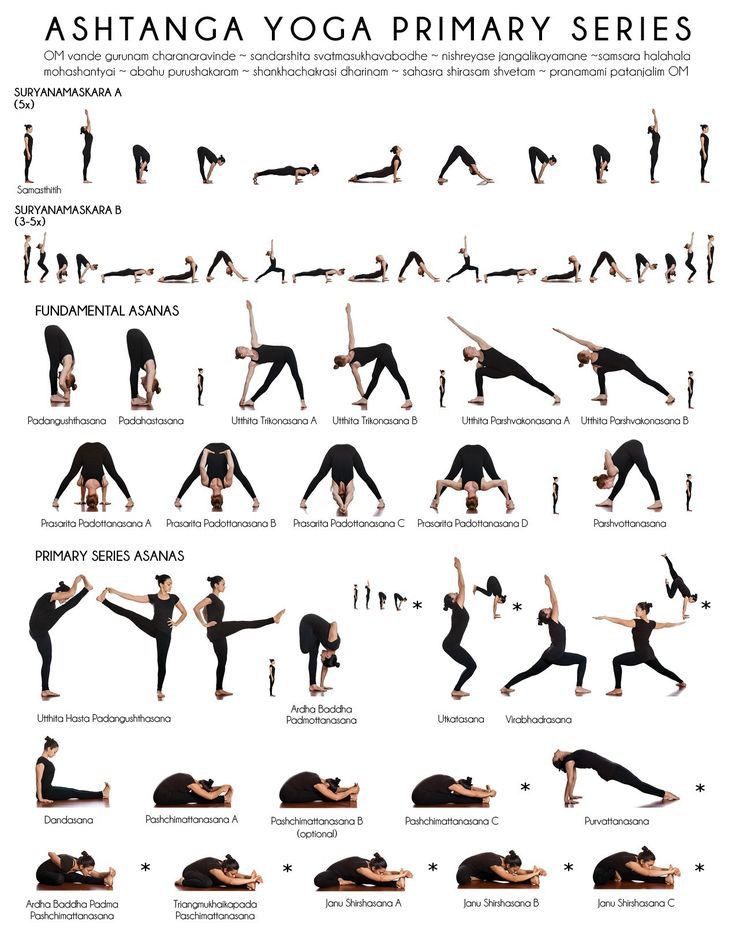

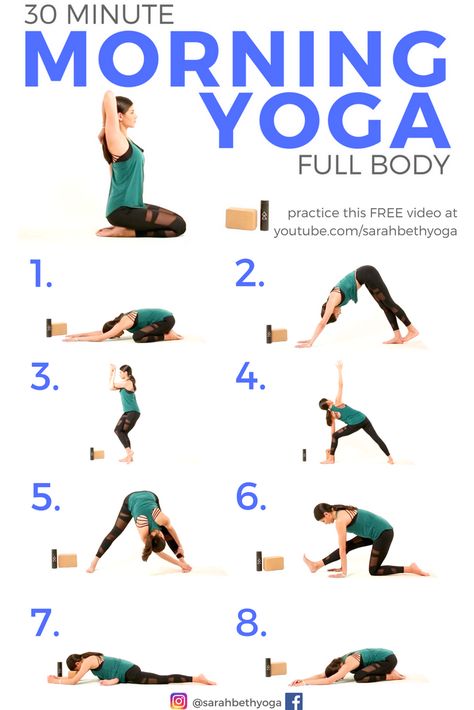

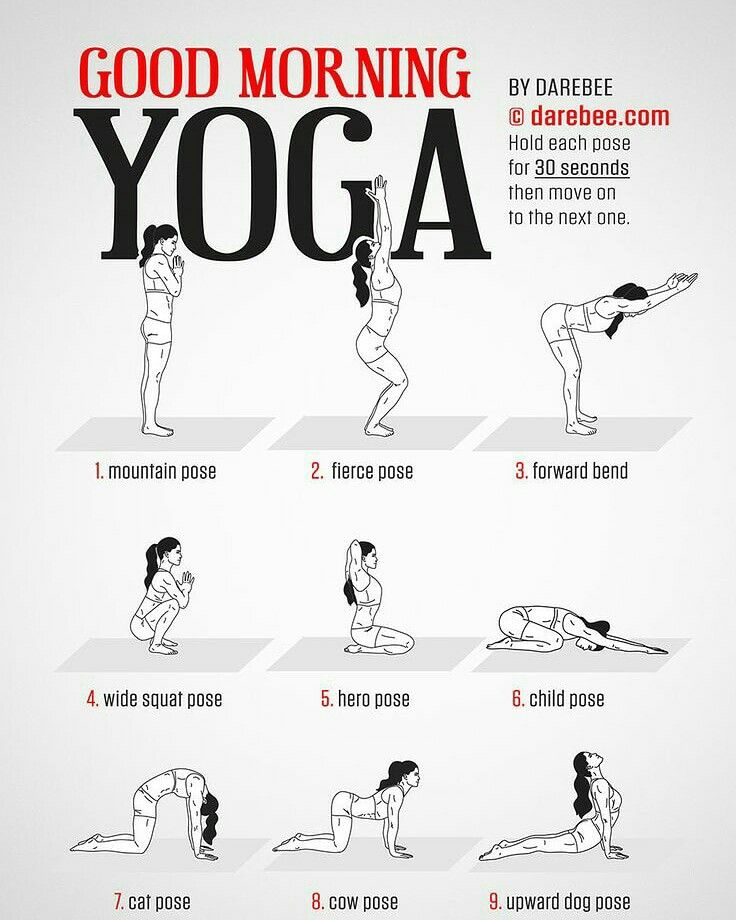

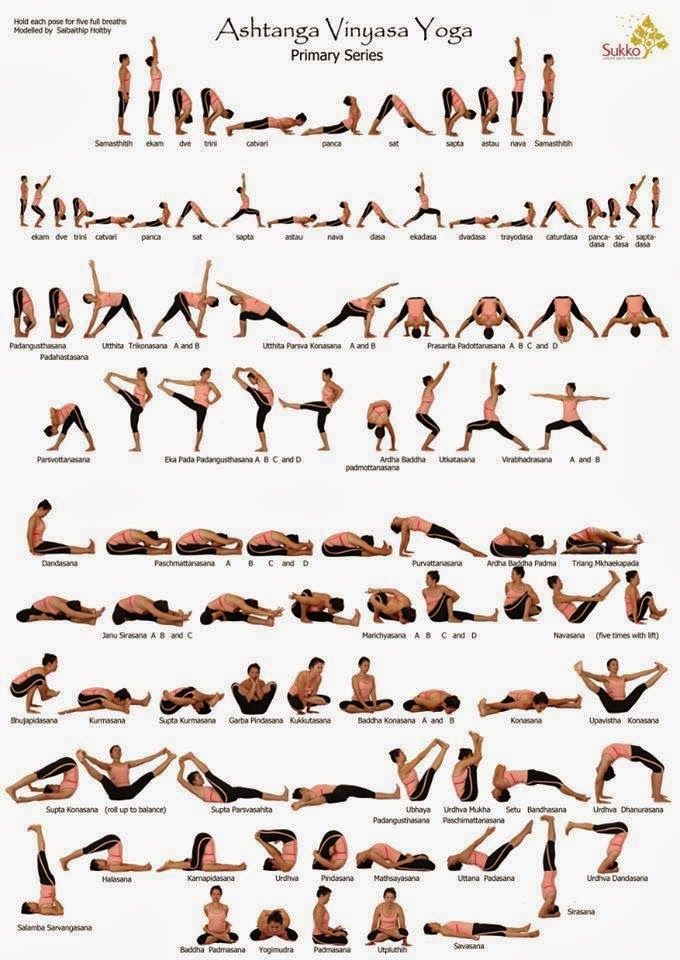

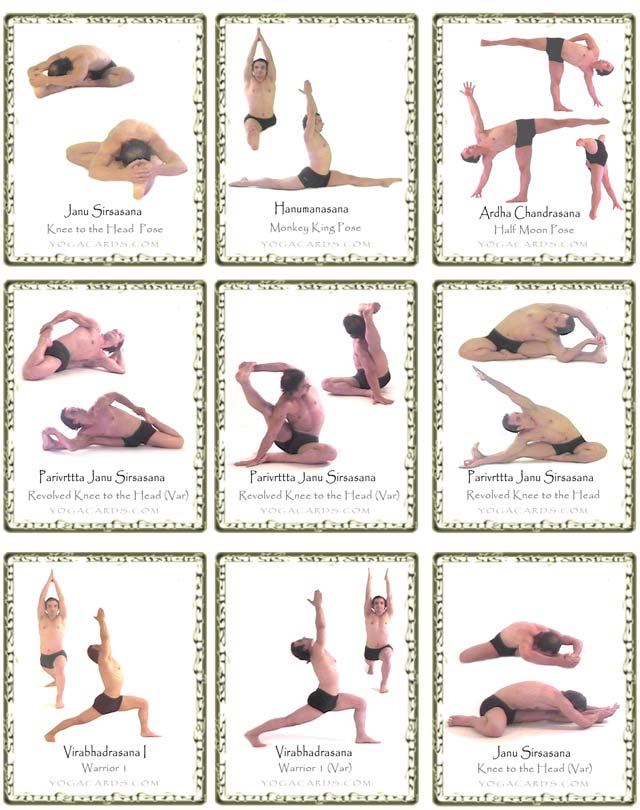

Participants in yoga group were provided 12-week yoga sessions developed by the research team, 1 session in every 2 weeks. Yoga sessions were held in a specific meeting room and performed under the instruction of a yoga instructor. The style of yoga in this trail was Kripalu. This kind of yoga focuses on compassionate self‐observation, building connections between mind and body on the present moment. The yoga sessions were designed to adapt for all body types and be noncompetitive. The contents of yoga sessions were shown in Table 1.

This kind of yoga focuses on compassionate self‐observation, building connections between mind and body on the present moment. The yoga sessions were designed to adapt for all body types and be noncompetitive. The contents of yoga sessions were shown in Table 1.

Full size table

Assessments

In this trail, psychometric assessments included the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) and the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21). All the measures were collected at baseline, post-intervention, and 3-month follow-up.

IES-R was employed to evaluate PTSD symptoms. This self-report measure consists of 22 items. The score of each item is from 0 to 4 (0 = not at all, 1 = a little bit, 2 = moderately, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = extremely). There are three subscales, avoidance, intrusion, and hyperarousal. The total score is the sum of the three subscales scores, ranges from 0 to 88. Higher IES-R score indicates worse symptom.

DASS-21 was employed to assess the severity of psychological distress. This self-report scale has 21 items to evaluate anxiety, depression, and stress. The score of each item is from 0 to 3 and the sum of the scores of items is total score. Higher score shows stronger symptom of anxiety, depression, and stress.

Data analysis

In this research, statistical analyses were performed by SPSS version 17.0 software. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or proportion (%). Differences in continuous variables between different groups were compared by ANOVA test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns: no significance.

Results

Demographics

Table 2 showed the participants’ characteristics in two groups. Based on the result of statistical analysis, no significant differences were found between the participants in two groups on any of the characteristics, such as age, body mass index (BMI), education level, marital status, employment status, role in MVA, injury severity, days since MVA, or perceived life threat to self (all p > 0. 05).

05).

Full size table

Total scores of IES-R and DASS-21

IES-R total scores of participants in these two groups were shown in Fig. 2. In both groups, IES-R total scores decreased throughout the trial. No significant differences were found between two groups on IES-R total scores at baseline and post-follow-up (all p > 0.05). However, post-intervention IES-R total score of yoga group was significantly lower than that of control group (p = 0.01).

Fig. 2IES-R total scores for the two groups by time point. Data were shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 compared with control group. IES-R impact of event scale-revised

Full size image

DASS-21 total scores were shown in Fig. 3. DASS-21 total scores showed reductions over time for both groups. At baseline, the DASS-21 total scores in both groups had no significant difference (p > 0. 05). At both post-intervention and 3-months post intervention, the DASS-21 total scores of yoga group were both significantly lower than those of control group (p = 0.043, p = 0.024).

05). At both post-intervention and 3-months post intervention, the DASS-21 total scores of yoga group were both significantly lower than those of control group (p = 0.043, p = 0.024).

DASS total scores for the two groups by time point. Data were shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 compared with control group. DASS depression, anxiety, and stress scale

Full size image

The scores of subscales in DASS-21 and IES-R

The scores of subscales in DASS-21 and IES-R were presented in Table 3. No significant differences were found between groups for baseline IES-R and DASS-21 subscales. For DASS-21, however, the level of stress was not influenced by the intervention of yoga. For IES-R, participants in yoga group had lower levels of intrusion and avoidance compared to control group after intervention (p = 0.002, p < 0.001). At 3-months post intervention, intrusion level and avoidance level in the yoga group were significantly lower than in the control group (p = 0. 037).

037).

Full size table

Discussion

This randomized controlled trail examined a 12-week yoga intervention’s effect on psychological distress in women with PTSD following MVA. The preliminary results demonstrated that both yoga group and control group showed trends for the improvement of psychological distress, while the intervention of yoga promoted the recovery of psychological disorders in women with PTSD following MVA. There were significant reductions in depression, anxiety, and intrusion in yoga group as compared to control group after 12-week intervention and 3-month follow-up. Additionally, the intervention of yoga had no notable influence on stress and hyperarousal in women with PTSD following MVA.

PTSD refers to a series of clinical symptoms shown by the patient's psychological and physical excessive stress response after personally experiencing a serious traumatic event that causes or may lead to death or physical injury [14]. With the deepening of research, PTSD is widely present in people who have experienced all serious traumas including violent events and natural disasters [15]. In modern society, more attention has been paid to the psychological disorder caused by traffic accidents, including PTSD. It has been reported that the incidence of MVA-caused PTSD ranges from 8.5% to 23.1% [16]. However, in China, the patients' physiological problems caused by traffic accidents have been effectively treated, while the psychological problems such as PTSD have not received enough attention and corresponding treatment, which often increases the patient's suffering and prolongs the treatment. PTSD has association with both dysregulation of neuroendocrine system and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone-system. Traumatization has lasting and cumulative effects on the activity of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone-system and elevated renin levels may increase the risk for developing PTSD and other disease [8, 17].

With the deepening of research, PTSD is widely present in people who have experienced all serious traumas including violent events and natural disasters [15]. In modern society, more attention has been paid to the psychological disorder caused by traffic accidents, including PTSD. It has been reported that the incidence of MVA-caused PTSD ranges from 8.5% to 23.1% [16]. However, in China, the patients' physiological problems caused by traffic accidents have been effectively treated, while the psychological problems such as PTSD have not received enough attention and corresponding treatment, which often increases the patient's suffering and prolongs the treatment. PTSD has association with both dysregulation of neuroendocrine system and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone-system. Traumatization has lasting and cumulative effects on the activity of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone-system and elevated renin levels may increase the risk for developing PTSD and other disease [8, 17].

In recent years, yoga has been considered as complementary and alternative medicine [18]. Yoga is a combination of breathing techniques, meditation, physical postures, and relaxation which have benefits for both physical and mental conditions. Yoga in the school setting is a viable and potentially efficacious strategy for improving child and adolescent health [19].

Yoga is a combination of breathing techniques, meditation, physical postures, and relaxation which have benefits for both physical and mental conditions. Yoga in the school setting is a viable and potentially efficacious strategy for improving child and adolescent health [19].

Meditation and yoga are promising complementary approaches in the treatment of PTSD among adults [20]. A study has demonstrated the preliminary efficacy and feasibility of online yoga on alleviating symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression in women who have experienced stillbirth [10]. A randomized controlled trial in women with PTSD has proved that Kripalu-based yoga intervention reduces expressive suppression and improves PTSD symptoms through increasing psychological flexibility [21]. Another research also showed that a 12-session Kripalu-based yoga intervention plays a role in the alleviation of reexperiencing and hyperarousal symptoms in women with PTSD [21]. Yoga may be an effective alternative to trauma-focused therapy for women veterans with PTSD [22]. Researchers have illustrated that yoga practice has association with decreased sympathetic activity, increased parasympathetic activity, and down-regulated hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and positive effects on cognitive activity [23, 24]. Practicing yoga triggers the adjustment of cognition and behavior through enhancing mind–body awareness, increases behavioral activation in pleasant activities, improves emotion‐regulation skill, and reduces reexperiencing and avoidance symptoms [25,26,27]. Yoga has positively impact on PTSD symptoms and may be an effective adjunctive treatment for PTSD. Thus, in this research, we explored whether Kripalu-based yoga intervention contributed to the improvement of psychological distress in women with PTSD following MVA.

Researchers have illustrated that yoga practice has association with decreased sympathetic activity, increased parasympathetic activity, and down-regulated hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and positive effects on cognitive activity [23, 24]. Practicing yoga triggers the adjustment of cognition and behavior through enhancing mind–body awareness, increases behavioral activation in pleasant activities, improves emotion‐regulation skill, and reduces reexperiencing and avoidance symptoms [25,26,27]. Yoga has positively impact on PTSD symptoms and may be an effective adjunctive treatment for PTSD. Thus, in this research, we explored whether Kripalu-based yoga intervention contributed to the improvement of psychological distress in women with PTSD following MVA.

In this trail, participants in yoga group were provided 12-week Kripalu-based yoga sessions. Sessions were held once every 2 weeks. Kripalu-based yoga emphasizes the connections between mind and body. Kripalu yoga is often described as "dynamic meditation", focusing less on the physical details of the yoga postures and more on the emotional and psychological feelings they bring to the person, thus requiring the student to maintain a gentle, compassionate and introspective attitude. This kind of yoga believes that the body has its own wisdom and sends out messages to prompt the individual to practice the yoga postures in a fluid and natural way. Each yoga pose is held for a long period of time in order to uncover or release repressed emotions. Kripalu yoga may have potential as a PTSD therapy in a veteran or military population [28].

This kind of yoga believes that the body has its own wisdom and sends out messages to prompt the individual to practice the yoga postures in a fluid and natural way. Each yoga pose is held for a long period of time in order to uncover or release repressed emotions. Kripalu yoga may have potential as a PTSD therapy in a veteran or military population [28].

In 47 participants of yoga group, only 6 dropped out during 12-week intervention. Thus, most of participants were satisfied with the intervention. Time, mood, and stress might be the major reason for not completing the study. When examined separately for the two groups, the IES-R total scores and DASS-21 total scores both decreased for both groups after 12-week intervention and 3-month follow-up. IES-R total scores in yoga group was significantly lower than in control group postintervention. DASS-21 total scores also had significant differences between groups postintervention and post-follow-up. Thus, the 12-week intervention of yoga enhanced the improvement of psychological distress in women with PTSD following MVA. Decreased scores of IES-R and DASS-21 indicated that clinical improvement in the PTSD symptoms of women also happened in control group. It was possible that the exchanging of daily life experiences and playing board games enhanced the communication between patients and contributed to the improvement of psychological distress. Alternatively, other unmeasured variables may also account for the improvement in control group. When compared with control group, there were significant reduction in anxiety and depression symptoms at post-intervention and follow-up, but not in stress. The intervention of yoga might have no significant effect on alleviating stress caused by PTSD in woman survived from MVA. Results also demonstrated the short-term effects of yoga on intrusion and avoidance symptoms and the long-term effect on intrusion in women with PTSD following MVA. These findings provided preliminary evidence to suggest that yoga may reduce psychological distress and improve PTSD symptoms among women with PTSD following MVA.

Decreased scores of IES-R and DASS-21 indicated that clinical improvement in the PTSD symptoms of women also happened in control group. It was possible that the exchanging of daily life experiences and playing board games enhanced the communication between patients and contributed to the improvement of psychological distress. Alternatively, other unmeasured variables may also account for the improvement in control group. When compared with control group, there were significant reduction in anxiety and depression symptoms at post-intervention and follow-up, but not in stress. The intervention of yoga might have no significant effect on alleviating stress caused by PTSD in woman survived from MVA. Results also demonstrated the short-term effects of yoga on intrusion and avoidance symptoms and the long-term effect on intrusion in women with PTSD following MVA. These findings provided preliminary evidence to suggest that yoga may reduce psychological distress and improve PTSD symptoms among women with PTSD following MVA.

Several limitations of the research should be noted. First, the limitation of time and funding caused a relatively small sample size. Limited sample size might influence the detection of differences both between and within groups and limit the generalizability of conclusion. Second, we only evaluated the influence of the Kripalu-based yoga intervention on the participants. Since many different styles of yoga exist, different types might have diverse effects on physical and mental health and PTSD symptom reduction. Kripalu-based yoga might not be the most beneficial type. Although Kripalu-based yoga reduced psychological distress and improve PTSD symptoms, which specific aspect of the yoga practice in this trail was most effective was not evaluated. Third, in this trail, we utilized self-report data. Data might be influenced by the expectancy effects of patients and the results were subject to biases that are inevitable with this type of data.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the intervention of a 12-week yoga practice may be an effective and feasible strategy to reduce psychological distress in women with PTSD following MVA. The results of this study suggest that alleviating PTSD after a car accident through yoga is very feasible and can be sustained in daily life. PTSD from car accidents remains a noteworthy social problem that requires effective and feasible programs to alleviate PTSD in order to prevent negative health effects. The results of this study support the use of Kripalu yoga to improve the mental health of women with PTSD who have experienced a major car accident.

The results of this study suggest that alleviating PTSD after a car accident through yoga is very feasible and can be sustained in daily life. PTSD from car accidents remains a noteworthy social problem that requires effective and feasible programs to alleviate PTSD in order to prevent negative health effects. The results of this study support the use of Kripalu yoga to improve the mental health of women with PTSD who have experienced a major car accident.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Nickerson A, Aderka IM, Bryant RA, Hofmann SG. The role of attribution of trauma responsibility in posttraumatic stress disorder following motor vehicle accidents. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:483–8.

Article Google Scholar

Craig A, Tran Y, Guest R, Gopinath B, Jagnoor J, Bryant RA, Collie A, Tate R, Kenardy J, Middleton JW, Cameron I.

Psychological impact of injuries sustained in motor vehicle crashes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011993.

Psychological impact of injuries sustained in motor vehicle crashes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011993.Article Google Scholar

Guest R, Tran Y, Gopinath B, Cameron ID, Craig A. Psychological distress following a motor vehicle crash: a systematic review of preventative interventions. Injury. 2016;47:2415–23.

Article Google Scholar

Mayou R, Bryant B. Consequences of road traffic accidents for different types of road user. Injury. 2003;34:197–202.

Article Google Scholar

Papadakaki M, Ferraro OE, Orsi C, Otte D, Tzamalouka G, von-der-Geest M, Lajunen T, Ozkan T, Morandi A, Sarris M, et al. Psychological distress and physical disability in patients sustaining severe injuries in road traffic crashes: results from a one-year cohort study from three European countries.

Injury. 2017;48:297–306.

Injury. 2017;48:297–306.Article Google Scholar

Heron-Delaney M, Kenardy J, Charlton E, Matsuoka Y. A systematic review of predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for adult road traffic crash survivors. Injury. 2013;44:1413–22.

Article Google Scholar

Craig A, Elbers NA, Jagnoor J, Gopinath B, Kifley A, Dinh M, Pozzato I, Ivers RQ, Nicholas M, Cameron ID. The psychological impact of traffic injuries sustained in a road crash by bicyclists: a prospective study. Traffic Inj Prev. 2017;18:273–80.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Terock J, Hannemann A, Janowitz D, Freyberger HJ, Felix SB, Dorr M, Nauck M, Volzke H, Grabe HJ. Associations of trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder with the activity of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone-system in the general population.

Psychol Med. 2019;49:843–51.

Psychol Med. 2019;49:843–51.Article Google Scholar

Wu KK, Li FW, Cho VW. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of brief-CBT for patients with symptoms of posttraumatic stress following a motor vehicle crash. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2014;42:31–47.

Article Google Scholar

Huberty J, Sullivan M, Green J, Kurka J, Leiferman J, Gold K, Cacciatore J. Online yoga to reduce post traumatic stress in women who have experienced stillbirth: a randomized control feasibility trial. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20:173.

Article Google Scholar

Nolan CR. Bending without breaking: a narrative review of trauma-sensitive yoga for women with PTSD. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;24:32–40.

Article Google Scholar

Macy RJ, Jones E, Graham LM, Roach L. Yoga for trauma and related mental health problems: a meta-review with clinical and service recommendations. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2018;19:35–57.

Article Google Scholar

van der Kolk BA, Stone L, West J, Rhodes A, Emerson D, Suvak M, Spinazzola J. Yoga as an adjunctive treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:e559-565.

Article Google Scholar

Qi W, Gevonden M, Shalev A. Prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder after trauma: current evidence and future directions. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18:20.

Article Google Scholar

Farooqui M, Quadri SA, Suriya SS, Khan MA, Ovais M, Sohail Z, Shoaib S, Tohid H, Hassan M. Posttraumatic stress disorder: a serious post-earthquake complication.

Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2017;39:135–43.

Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2017;39:135–43.Article Google Scholar

Wang X, Lan C, Chen J, Wang W, Zhang H, Li L. Creative arts program as an intervention for PTSD: a randomized clinical trial with motor vehicle accident survivors. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:13585–91.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ahmadian E, Pennefather PS, Eftekhari A, Heidari R, Eghbal MA. Role of renin–angiotensin system in liver diseases: an outline on the potential therapeutic points of intervention. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;10:1279–88.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Mohammad A, Thakur P, Kumar R, Kaur S, Saini RV, Saini AK. Biological markers for the effects of yoga as a complementary and alternative medicine. J Complement Integr Med. 2019;16.

Khalsa SB, Butzer B. Yoga in school settings: a research review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1373:45–55.

Article Google Scholar

Gallegos AM, Crean HF, Pigeon WR, Heffner KL. Meditation and yoga for posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;58:115–24.

Article Google Scholar

Mitchell KS, Dick AM, DiMartino DM, Smith BN, Niles B, Koenen KC, Street A. A pilot study of a randomized controlled trial of yoga as an intervention for PTSD symptoms in women. J Trauma Stress. 2014;27:121–8.

Article Google Scholar

Kelly U, Haywood T, Segell E, Higgins M. Trauma-sensitive yoga for post-traumatic stress disorder in women veterans who experienced military sexual trauma: interim results from a randomized controlled trial.

J Altern Complement Med. 2021;27:S45–59.

J Altern Complement Med. 2021;27:S45–59.Article Google Scholar

Rocha KK, Ribeiro AM, Rocha KC, Sousa MB, Albuquerque FS, Ribeiro S, Silva RH. Improvement in physiological and psychological parameters after 6 months of yoga practice. Conscious Cogn. 2012;21:843–50.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ross A, Thomas S. The health benefits of yoga and exercise: a review of comparison studies. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:3–12.

Article Google Scholar

Khalsa SB. Yoga as a therapeutic intervention: a bibliometric analysis of published research studies. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;48:269–85.

PubMed Google Scholar

Uebelacker LA, Tremont G, Epstein-Lubow G, Gaudiano BA, Gillette T, Kalibatseva Z, Miller IW.

Open trial of Vinyasa yoga for persistently depressed individuals: evidence of feasibility and acceptability. Behav Modif. 2010;34:247–64.

Open trial of Vinyasa yoga for persistently depressed individuals: evidence of feasibility and acceptability. Behav Modif. 2010;34:247–64.Article Google Scholar

Holzel BK, Carmody J, Vangel M, Congleton C, Yerramsetti SM, Gard T, Lazar SW. Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Res. 2011;191:36–43.

Article Google Scholar

Reinhardt KM, Noggle Taylor JJ, Johnston J, Zameer A, Cheema S, Khalsa SBS. Kripalu yoga for military veterans with PTSD: a randomized trial. J Clin Psychol. 2018;74:93–108.

Article Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

The Third Department, Qingdao Mental Health Center, No.

299 Nan Jing Road, Qingdao, 266034, Shandong, China

299 Nan Jing Road, Qingdao, 266034, Shandong, ChinaLei Yi, Ning Ma & Ni Duan

Department of Geriatrics, Qingdao Mental Health Center, No. 299 Nan Jing Road, Qingdao, 266034, Shandong, China

Yunling Lian

Authors

- Lei Yi

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Yunling Lian

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Ning Ma

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Ni Duan

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Data curation, analysis: LY, YL, NM, ND; Drafting of the manuscript: LY and ND; Concept, design of the study: LY and ND. All authors read and approved the publication the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the publication the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ni Duan.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qingdao Mental Health Center.

Consent for publication

All of the authors have consented to publication of this research.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Yoga for post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental disorder that can develop after exposure to a traumatic event such as violence, war, traffic accidents, child abuse, or other threats to a person's life. If post-traumatic stress disorder is long-term, serious behavioral problems can occur. Symptoms and mental health may worsen. nine0004

If post-traumatic stress disorder is long-term, serious behavioral problems can occur. Symptoms and mental health may worsen. nine0004

A growing number of the world's leading experts in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are researching the use of yoga as a therapy to help people cope with post-traumatic stress disorder and regain a sense of calm. This article touches on a discussion of the mind-body connection in trauma, how yoga works, and precautions when teaching trauma-sensitive yoga students.

The aim of the research is to find a way to allow people to regulate the main excitatory system in the brain and feel safe inside their body, understand and understand how trauma affects the brain. Yoga has proven to be a way to teach people to safely feel their physical sensations and to develop calmness. nine0004

The practice of silence in yoga

Many yoga websites have claimed that yoga can change basic brain functions, but this was based on intuition, not scientific research. Can yoga positively affect the basic regulatory mechanism of the brain? Some trauma-sensitive people may feel terribly insecure about the sensations that certain asanas evoke. What most people don't realize is that trauma is not the story of something terrible that happened in the past, but the remnant of imprints left on people's sensory and hormonal systems. Injured people are often afraid of the sensations in their own body. Most trauma-sensitive people need some form of body-oriented psychotherapy or bodywork to restore a sense of security in their body. nine0004

Can yoga positively affect the basic regulatory mechanism of the brain? Some trauma-sensitive people may feel terribly insecure about the sensations that certain asanas evoke. What most people don't realize is that trauma is not the story of something terrible that happened in the past, but the remnant of imprints left on people's sensory and hormonal systems. Injured people are often afraid of the sensations in their own body. Most trauma-sensitive people need some form of body-oriented psychotherapy or bodywork to restore a sense of security in their body. nine0004

How extreme stress affects brain function

Neuroimaging studies of people in highly emotional states show that strong emotions such as anger, fear, or sadness cause increased activity in brain regions associated with fear and self-preservation, and decreased activity in brain regions associated with a sense of full presence.

People with PTSD are losing their way in the world. Their bodies continue to live in the internal environment of trauma. We are all biologically and neurologically programmed to deal with emergencies, but for people with PTSD, time stops. This makes it difficult to enjoy the present because the body continues to reproduce the past. If you practice yoga and can develop a strong body that feels comfortable, it can go a long way in helping you get into the here and now rather than staying in the past. nine0004

We are all biologically and neurologically programmed to deal with emergencies, but for people with PTSD, time stops. This makes it difficult to enjoy the present because the body continues to reproduce the past. If you practice yoga and can develop a strong body that feels comfortable, it can go a long way in helping you get into the here and now rather than staying in the past. nine0004

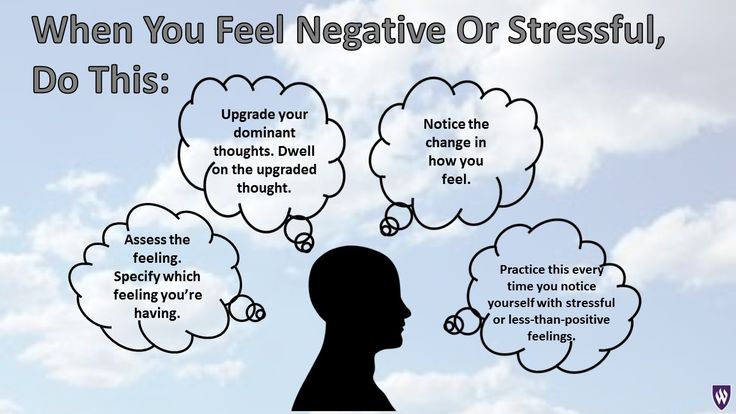

Basic call for people at risk of injury

The task is to learn to endure feelings and sensations by increasing the ability to intercept or sitting with oneself, noticing what is happening inside - the basic principle of meditation. They need to learn how to regulate arousal. Trauma-sensitive people lose track of time and think that something will last forever. Their task is to learn to notice what is happening and how things can change, instead of running away or resorting to alcohol or drugs to self-medicate. nine0004

Emotions - a guide to effective action

Emotion function - electronic movement, involvement in action. If you are afraid, you want to move away from the object of fear. If you are angry, it seems to you that you want to make contact or engage in physical resolution of the conflict with the one who makes you angry. If you love someone, you want to make some movement towards that person. This is the purpose of emotion – to spur us to action. When you are injured, your movements are paralyzed. The victim of abuse is almost always trapped, pinned to the ground, or unable to move. Later, if there is a perceived threat, the body reacts as if it needs to move, but again it feels helpless and paralyzed, unable to function effectively. All the chemicals are released to go into action, but the body doesn't know how to move. Their task is that after encountering physical helplessness, effective measures must be taken. nine0004

If you are afraid, you want to move away from the object of fear. If you are angry, it seems to you that you want to make contact or engage in physical resolution of the conflict with the one who makes you angry. If you love someone, you want to make some movement towards that person. This is the purpose of emotion – to spur us to action. When you are injured, your movements are paralyzed. The victim of abuse is almost always trapped, pinned to the ground, or unable to move. Later, if there is a perceived threat, the body reacts as if it needs to move, but again it feels helpless and paralyzed, unable to function effectively. All the chemicals are released to go into action, but the body doesn't know how to move. Their task is that after encountering physical helplessness, effective measures must be taken. nine0004

Problem with self-monitoring

The rational brain is the crown of glory of man. He helps us to participate in the life of the world, but does not help us take care of ourselves. In other words, the rational mind, while capable of organizing feelings and impulses, is not very well equipped to suppress emotions, thoughts, and impulses. People with PTSD usually lose touch with their physical sensations and, as a result, are unable to take care of themselves. At the other end of the brain, the reptilian part does not know how to soothe and care for the mind. However, when this system is harnessed, the mind becomes clearer and it becomes easier to regain perspective on your life. Surprisingly, in contrast to Asian and African cultures, Western traditions pay little attention to the development of methods of calming - we are encouraged to "live better through chemistry." nine0004

In other words, the rational mind, while capable of organizing feelings and impulses, is not very well equipped to suppress emotions, thoughts, and impulses. People with PTSD usually lose touch with their physical sensations and, as a result, are unable to take care of themselves. At the other end of the brain, the reptilian part does not know how to soothe and care for the mind. However, when this system is harnessed, the mind becomes clearer and it becomes easier to regain perspective on your life. Surprisingly, in contrast to Asian and African cultures, Western traditions pay little attention to the development of methods of calming - we are encouraged to "live better through chemistry." nine0004

Western psychotherapy paid little attention to the experience and interpretation of disturbed physical sensations and patterns of action. Yoga is one of the Asian traditions that clearly helps to restore the body and mind. To heal from PTSD, you need to learn how to control your bodily reflexes. Post-traumatic stress disorder causes memory to accumulate at a sensory level - in the body. Yoga offers a way to reprogram automatic physical responses. Mindfulness, the ability to carefully observe the ebb and flow of inner experience and notice any thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations and impulses that arise, are important components in healing from post-traumatic stress disorder. nine0004

Post-traumatic stress disorder causes memory to accumulate at a sensory level - in the body. Yoga offers a way to reprogram automatic physical responses. Mindfulness, the ability to carefully observe the ebb and flow of inner experience and notice any thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations and impulses that arise, are important components in healing from post-traumatic stress disorder. nine0004

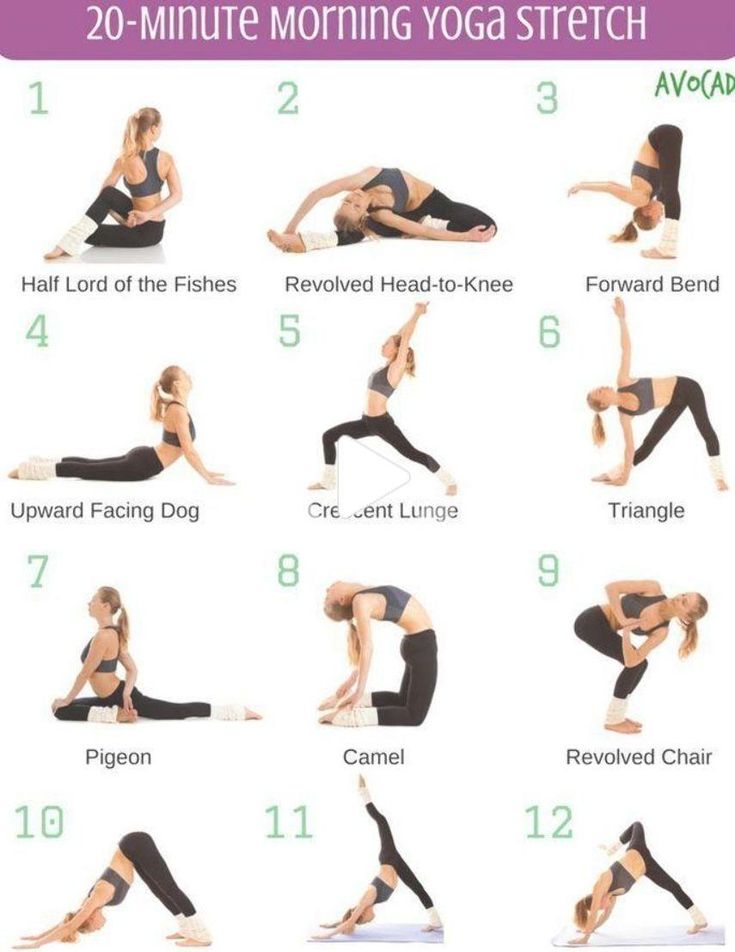

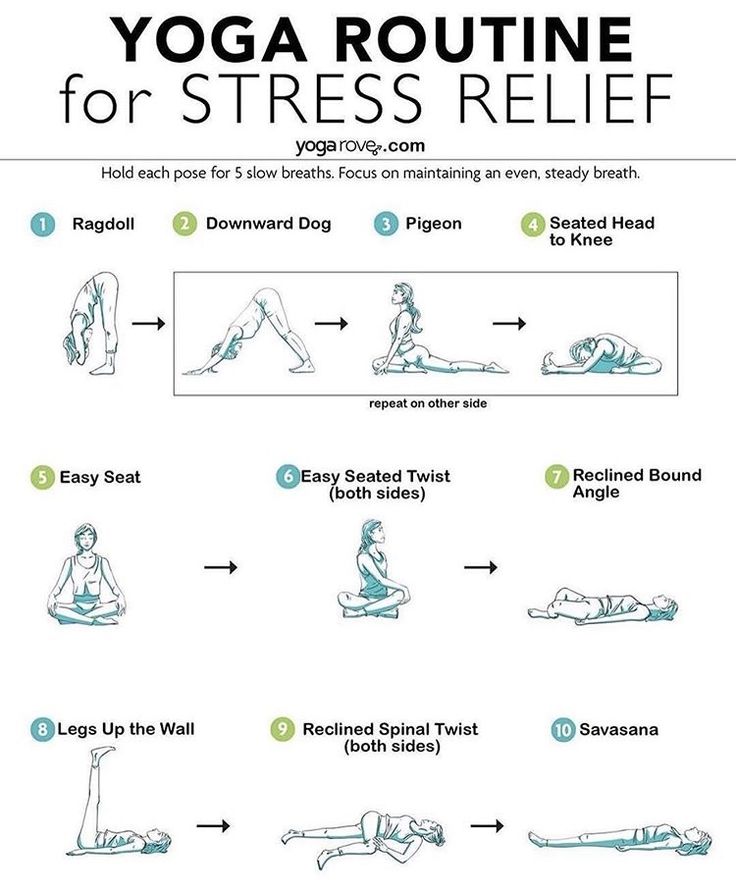

Yoga - restoration of self-regulation

Yoga helps to regulate the emotional and physiological state. It allows the body to regain its natural movement and teaches you to use the breath for self-regulation. What is beautiful about yoga is that it teaches us – and this is a critical moment for those who feel trapped in their memory experiences – that everything comes to an end. When performing some asanas, discomfort may occur. But by keeping time while they stay in the pose for a limited amount of time, they may notice that the discomfort can be tolerated until they move into another pose. The process of being in a safe place and being with whatever sensations arise and seeing how they end is a process of positive imprinting. Yoga helps them make friends with their bodies, which betrayed them without guaranteeing safety. nine0004

The process of being in a safe place and being with whatever sensations arise and seeing how they end is a process of positive imprinting. Yoga helps them make friends with their bodies, which betrayed them without guaranteeing safety. nine0004

Another important aspect of yoga is the use of the breath. It is amazing that there is nothing in Western culture that teaches us that we can learn to control our own physiology - solutions always come from outside, starting with relationships, and if they fail, with alcohol or drugs. Yoga teaches us that there are things we can do to change our brainstem arousal system, our sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, and calm the brain.

Meditation for people with PTSD

The Dalai Lama and yoga masters such as Swami Satchidananda have made meditation almost mainstream. The neuroscience of meditation, according to which the brain can grow new cells and change itself, is becoming more well known and is finding its way into mental health services. If we meditate regularly, it can modulate the fear center and help us be more focused. However, if you are traumatized, silence is often scary. The memory of the trauma is preserved, so when you calm down, the demons come out. People with PTSD should first learn to regulate their physiology through breathing, posture, and relaxation and work on meditation. nine0004

If we meditate regularly, it can modulate the fear center and help us be more focused. However, if you are traumatized, silence is often scary. The memory of the trauma is preserved, so when you calm down, the demons come out. People with PTSD should first learn to regulate their physiology through breathing, posture, and relaxation and work on meditation. nine0004

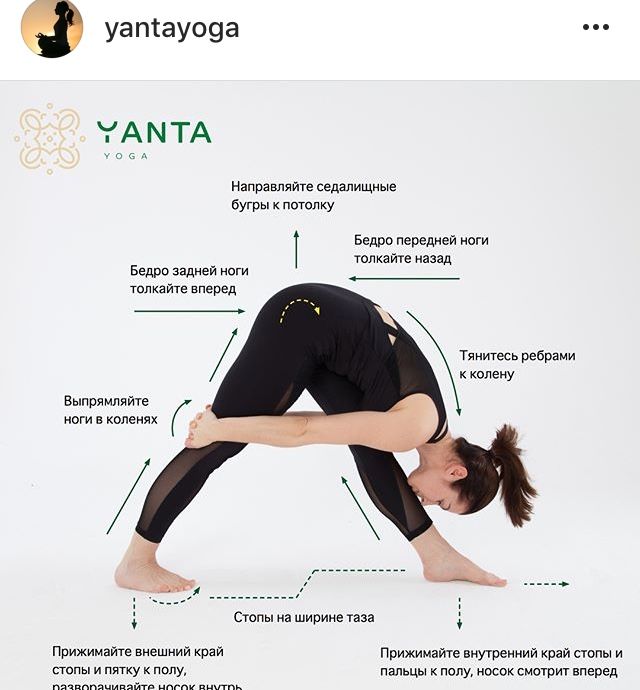

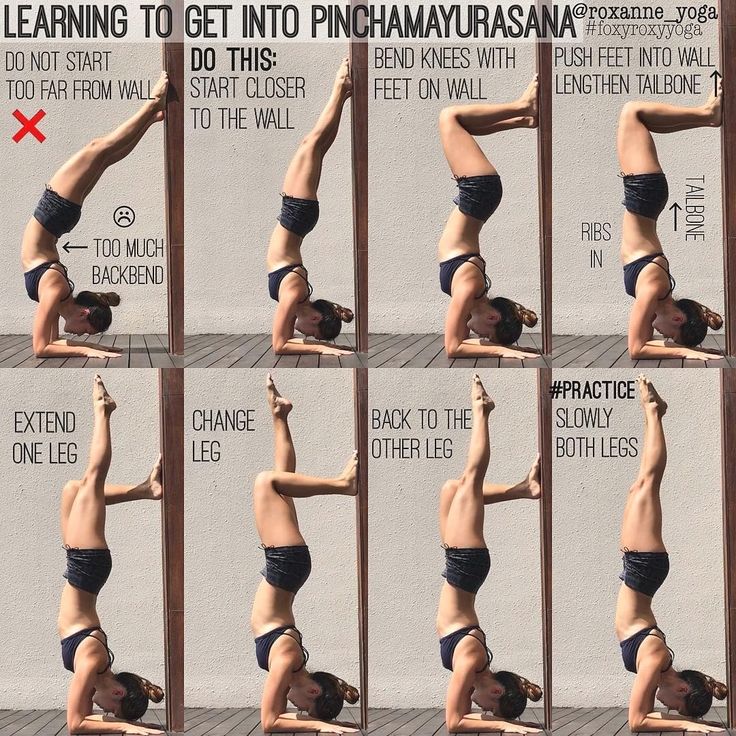

When we practice yoga, we open up and the psychological imprints are activated. Yoga teachers should be aware that the material will be revealed during the sessions and they should always be ready to help people calm their body by working with breathing and calming postures. Teachers should create a safe space in the classroom, focus on breathing and doing asanas. It is best to refrain from over-talking, explaining or preaching during the class - the job of a yoga teacher is to help people feel secure in all aspects of their personal experience. nine0004

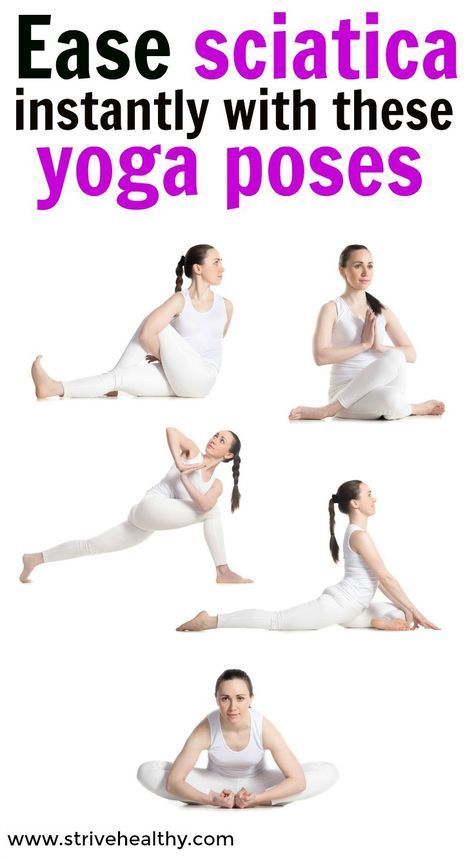

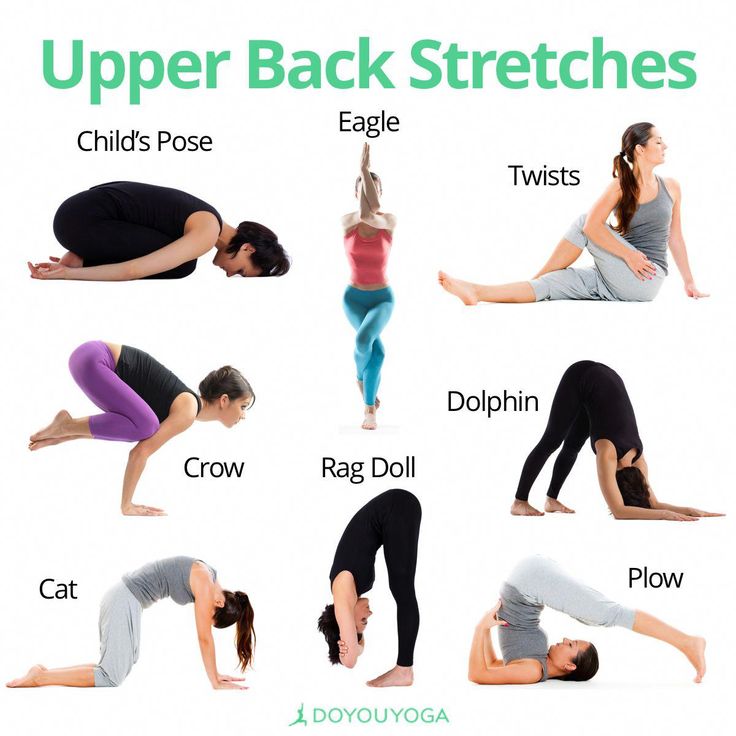

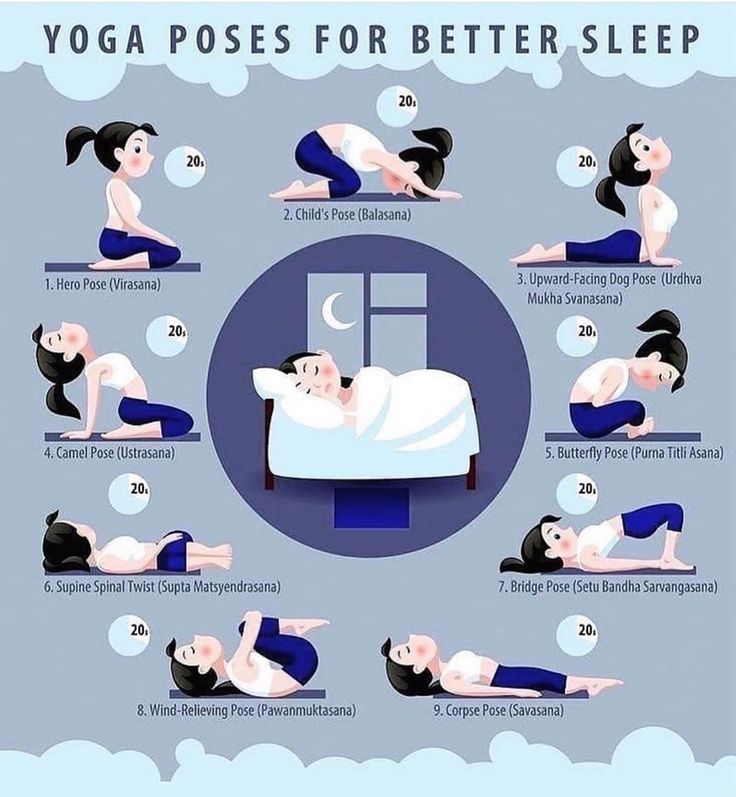

A yoga teacher should understand how people get excited and how to teach them to focus on self-regulation, no physical adjustments should be made without consulting people first. Some postures, such as Balasana (Child's Pose), can be very sensitive. It is important that trauma-sensitive students learn from teachers who are skilled in applying self-regulation techniques and who can help people use pranayama and movement to stay relaxed in the present moment. nine0004

Some postures, such as Balasana (Child's Pose), can be very sensitive. It is important that trauma-sensitive students learn from teachers who are skilled in applying self-regulation techniques and who can help people use pranayama and movement to stay relaxed in the present moment. nine0004

Yoga Therapy is an effective tool to help fight PTSD, allowing people to live after trauma with movement and stress-free situations.

- Yoga studio Vladimirskaya

- Yoga Center Sampsonievsky

How 7 Surprising Benefits of Yoga Nidra Can Help

Did you know that approximately 25% of the world's population suffers from some form of mood disorder? Or that 70% of Americans don't get enough sleep? nine0004

Enjoy the benefits of yoga nidra

These are just two of the many health problems society faces every day. But what if we told you that there is a practical solution to these and many other problems?

Yoga Nidra, also known as Yogic Sleep, is a meditative technique that dates back to the 7th to 6th centuries pre-Common Era and Buddhism. The unique process of meditation is deeply healing for the body, mind and soul.

The unique process of meditation is deeply healing for the body, mind and soul.

During sleep, brain waves begin to move from brooding beta waves, through stages of alpha waves, then theta waves, and finally enter the slowest sleep frequency - delta waves. Yoga Nidra guides practitioners into a state of relaxation between alpha and theta. This allows us to go into deep relaxation between wakefulness and sleep. nine0004

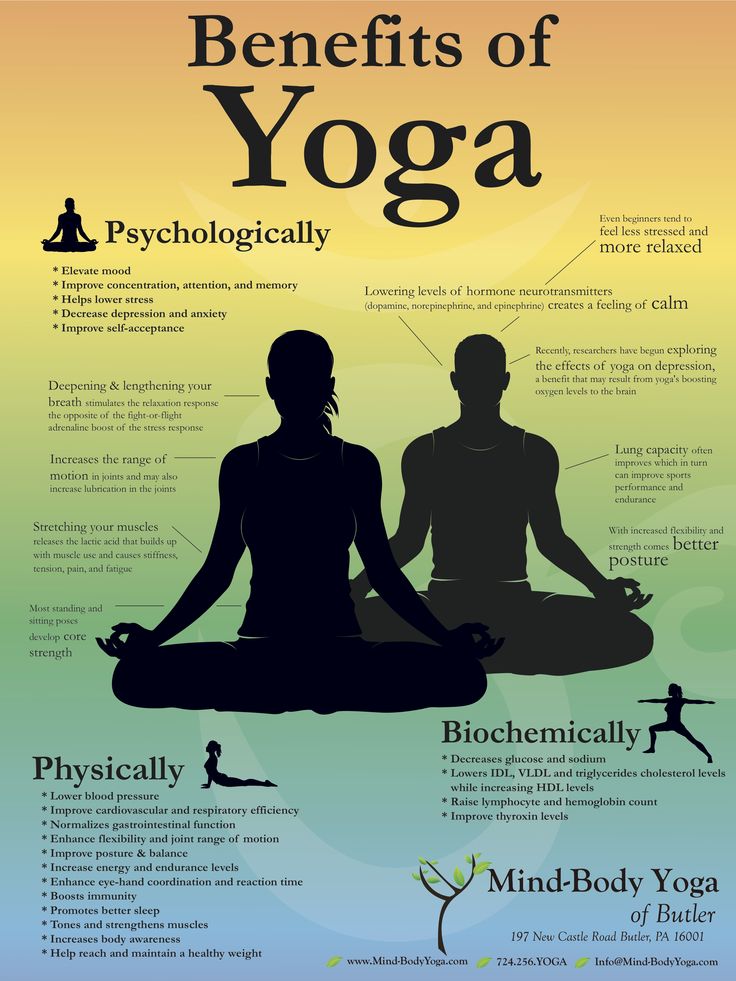

This state calms the autonomic nervous system, which regulates the processes in the body that occur without conscious effort. It also brings the parasympathetic nervous system into a state of deeper rest. By calming the nervous system, guided meditation has a profound effect on the brain and body.

Yoga Nidra offers many benefits, yet is one of the simplest yoga practices. All you have to do is put on your most comfortable clothes, find a quiet place, lie down in corpse position, and turn on the meditation soundtrack. nine0004

Read on to discover seven amazing yoga nidra benefits that can help improve your well-being.

1. Improving the way of thinking and reducing stress

During Yoga Nidra, you will enter a state of calming the mind and body through guided meditation. The practice creates physical and mental activity that changes brain waves, relieving emotional tension, slowing down the nervous system, and allowing muscles to relax. This induces a relaxation response, naturally reducing stress in the body and mind. Relieving mental and bodily stress can also relieve headaches and muscle tension. nine0004

Thought patterns are neural connections that have become stronger over time. The strength of these connections makes changing patterns very difficult - it can be compared to training a muscle. Yoga Nidra trains the brain to access thought patterns from a completely different perspective, entering an altered state of awareness. Instead of completely immersing yourself in your thoughts, you can watch them from the side. This new perspective allows you to relearn your thought patterns. nine0004

nine0004

2. Improve cognitive abilities and memory

The practice of yoga nidra improves your cognitive functions by creating space in the brain. To do this, it helps to reduce stress levels. When the brain is overwhelmed with emotions, there is little room left for it to perform its daily activities well. By reducing stress, the brain is freed to carry out its duties to the fullest. Yoga Nidra can be used to combat stress to help you filter out random thoughts that pop into your mind. nine0004

Those who regularly practice yoga nidra also notice an improvement in memory. It helps prevent aging-related cognitive decline and improves attention. Through frequent practice, you can improve your mental performance, allowing you to perform daily tasks more efficiently.

3. Increase Self-Esteem and Self-Confidence

Regular practice of Yoga Nidra can greatly increase your self-esteem and self-confidence. A recent study by two universities in Turkey supports this claim. The study examined the effect of Yoga Nidra on self-esteem and body image of burn patients and found significant improvement in these areas in the experimental group. nine0004

The study examined the effect of Yoga Nidra on self-esteem and body image of burn patients and found significant improvement in these areas in the experimental group. nine0004

The most important step in sleep meditation is setting intentions for yourself. These intentions are called sankalpa - these are the desires of your heart and the goals that you set for yourself. When you set your intentions, there is great satisfaction in achieving personal growth and progress. Achieving goals helps boost self-esteem and self-confidence.

4. Improving sleep and physical health

Yoga Nidra is very effective in improving the quality and timing of sleep. It helps to find a regular sleep pattern, allowing you to fall asleep faster at night, making it easier to fall asleep and ensuring a good night's rest. In addition, it helps treat sleep disorders such as insomnia. nine0004

Through frequent practice and learning how to relax your body and mind, you can calm your mind and body to improve your sleep cycle. Access to a state of deep sleep is critical to improving physical health and well-being. Please read our articles on yoga nidra for sleep to learn more.

Access to a state of deep sleep is critical to improving physical health and well-being. Please read our articles on yoga nidra for sleep to learn more.

5. Improving awareness in the waking state

Mindfulness is the quality and state of being aware of every moment of our lives. She rejects thoughts of the past and future, living completely in the present moment. Reasonable thinking emphasizes accepting the events that are happening in the moment, rather than condemning thoughts or denying what is happening around you. nine0004

During yogic sleep, your mind becomes quiet and enters a sleep-like state. Here you will be able to recognize when thoughts appear in your head and learn to let them go. Developing a deeper awareness will help you integrate mindfulness into your daily life. This will give you access to an improved state of wakefulness.

6. Reduces symptoms of anxiety and depression

People with anxiety disorder suffer from hypervigilance, an overactive brain, persistent negative thoughts and other stressors. The reactions of our mind are a source of suffering and can interfere with normal daily activities. Yoga Nidra helps reduce the symptoms of anxiety by teaching mental calmness and cultivating a state of deep physical and emotional relaxation. nine0004

The reactions of our mind are a source of suffering and can interfere with normal daily activities. Yoga Nidra helps reduce the symptoms of anxiety by teaching mental calmness and cultivating a state of deep physical and emotional relaxation. nine0004

In addition, the ancient practice releases pent-up emotions and stress to detoxify the brain. Yogic sleep is an effective stress reliever by helping you access thought patterns in a whole new state and even change them to become more acceptable to the changing daily life. Filtering negative thoughts from the subconscious reduces the symptoms and risk of depression and other psychological problems.

7. Treats chronic pain and PTSD

Richard Miller, founder of iRest, has developed several modern adaptations of the Yoga Nidra practice to help calm the areas of the brain responsible for negative thoughts and feelings. The use of Yoga Nidra as a treatment for chronic pain has been approved by the US Army Surgeon General as an intervention in the treatment of chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Yogic sleep brings the practitioner into a state of deep relaxation, after which he feels well rested. This calm state slows down the nervous system, giving the body time to heal. Here the body can rest, recover and bounce back. In addition, Yoga Nidra reduces inflammation and improves immune system function, which can effectively treat chronic pain. nine0004

Yogic sleep brings the practitioner into a state of deep relaxation, after which he feels well rested. This calm state slows down the nervous system, giving the body time to heal. Here the body can rest, recover and bounce back. In addition, Yoga Nidra reduces inflammation and improves immune system function, which can effectively treat chronic pain. nine0004

Other benefits of guided yoga nidra include:

- Lowers blood pressure.

- Reduces dependency.

- Increases creativity.

- Reduces post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Strengthening the immune system.

- Reduces cholesterol levels.

- Replenishes vital energy.

- Balances the nervous system.

- Reduces menstrual irregularities

- Strengthens the endocrine system.

- Reduces the need for pain medication.

For best results, practice Yoga Nidra several days a week. Even if it's only for a few minutes a day, frequent practice will help you access the important benefits of Yoga Nidra through the therapeutic healing process.

Yoga Nidra will help you feel rested, relaxed and full of energy. It can change your mood, feelings and more. Guided meditation is deeply restorative when practiced with attention and intention. Whether you suffer from a mood disorder, experience chronic pain, or simply want to improve your overall health and well-being, yoga nidra can help. nine0004

When it comes to the benefits of Yoga Nidra, the sky is the limit! What are you waiting for? Start your journey to better health today by reading our yoga nidra guide for beginners.

Disclaimer

Like any form of exercise, yoga comes with risks. Yoga should be practiced with care and respect to avoid injury.

If you suffer from any medical condition or are not sure which type of yoga or exercise is best for you and your conditions, we encourage you to consult with a healthcare professional or your physician. nine0004

Resources Yoga-Nidra Anaachana

Yoga-Niser Vicki

● Yoga-Nidra

● Yoga-Nidra script

● Questions and answers for yoga nidre

● NEGA-NIGA for sleeping

● Advantages Yoga-Nidras

Blogs about yoga nidra

● What is yoga-nizer

● Yoga-niper for beginners

● Sleep yoga

● Advantages of yoga nidra

Relax

- 0052 The State of Sleep Health in America.