According to cognitive dissonance theory

Cognitive Dissonance (Leon Festinger) - InstructionalDesign.org

Last Updated November 30th, 2018 06:55 pm

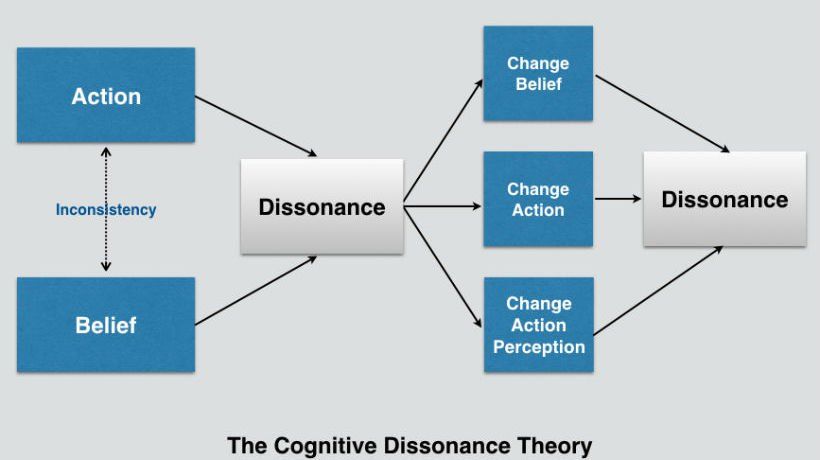

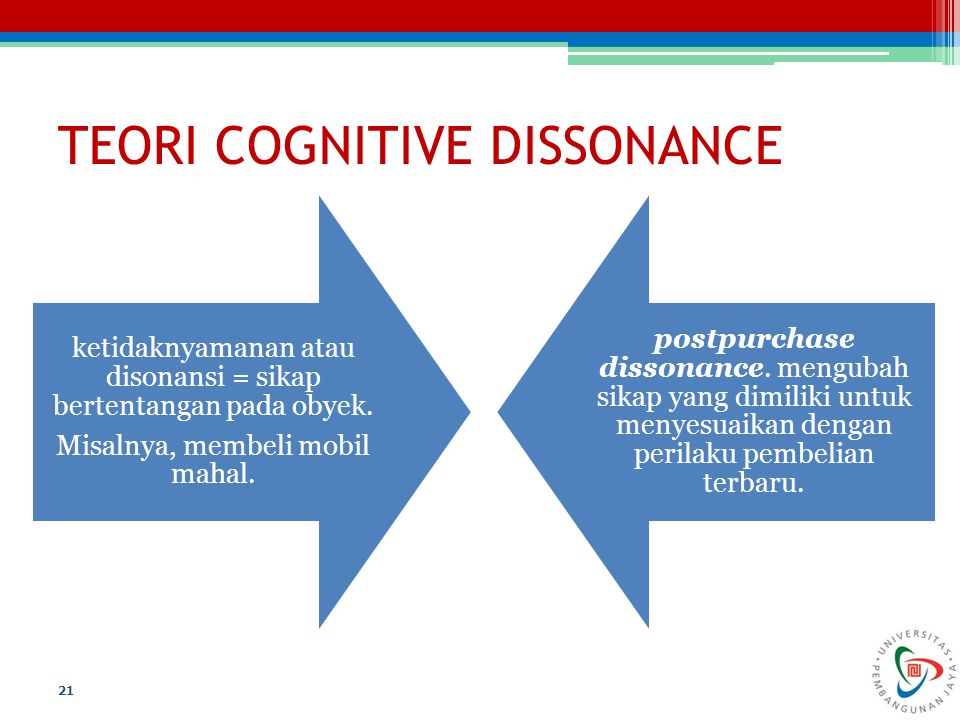

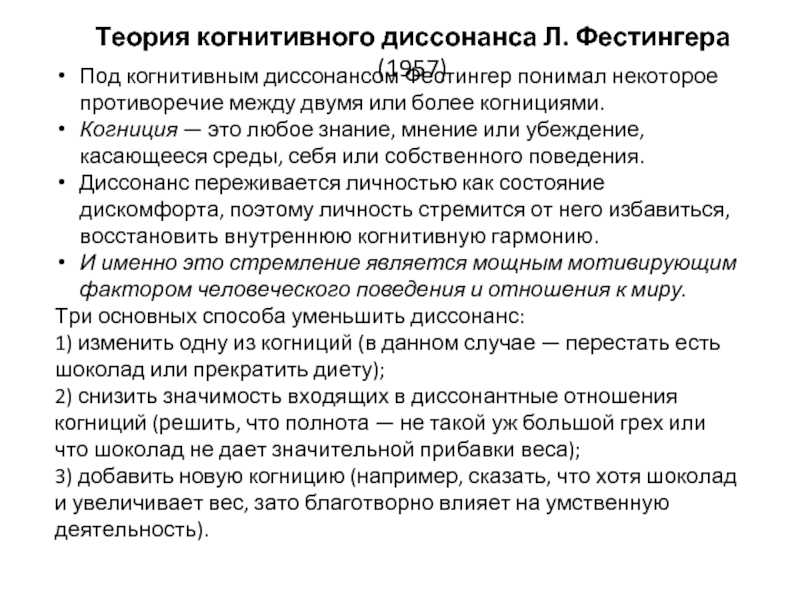

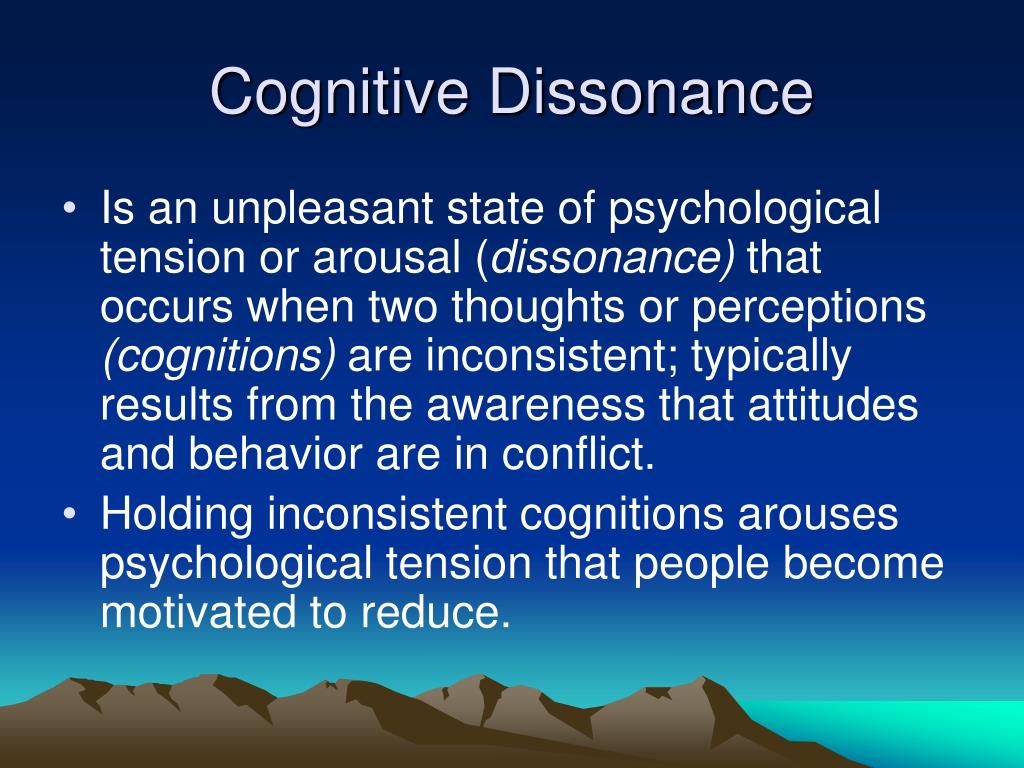

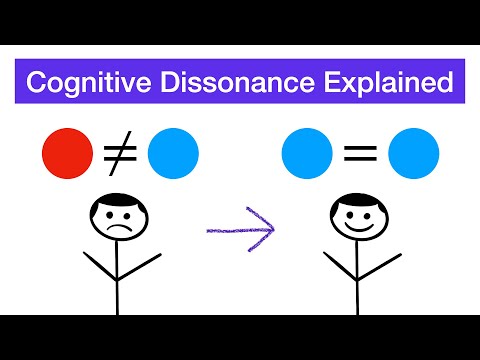

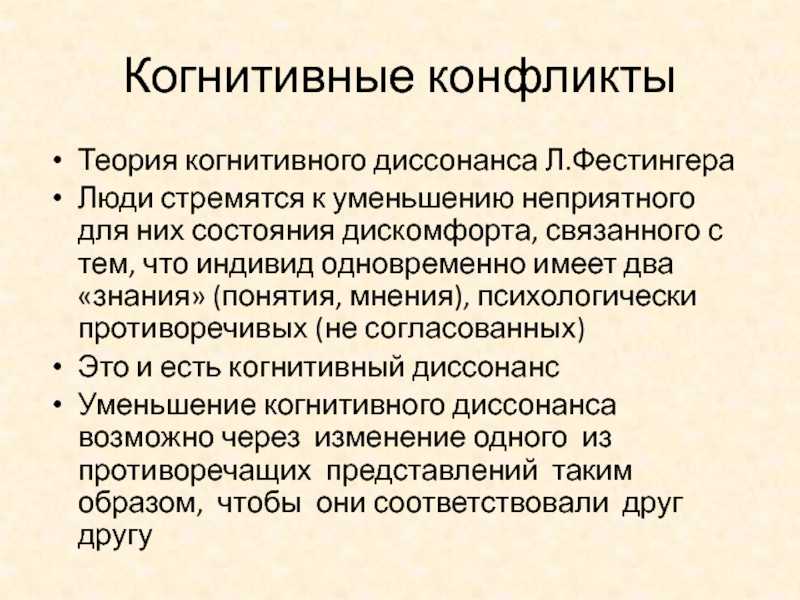

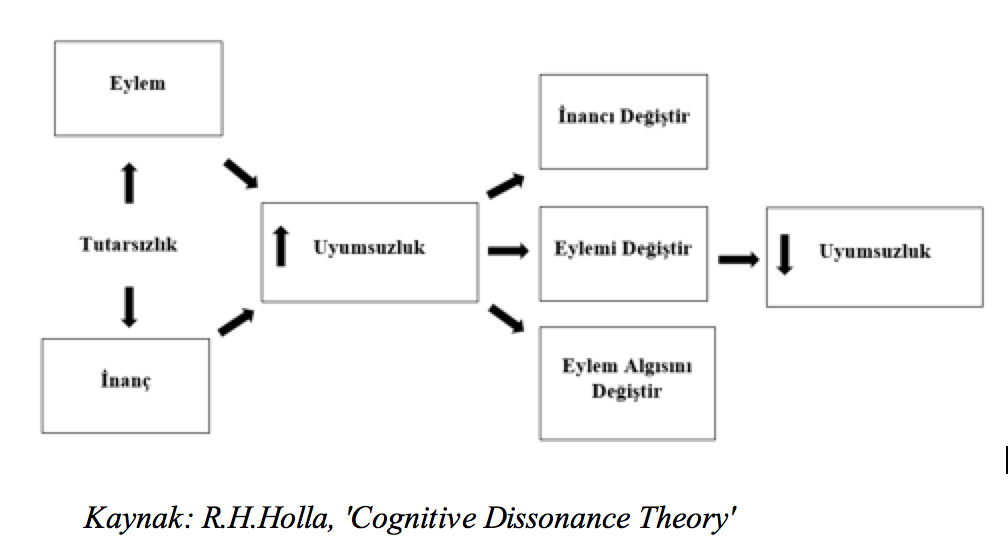

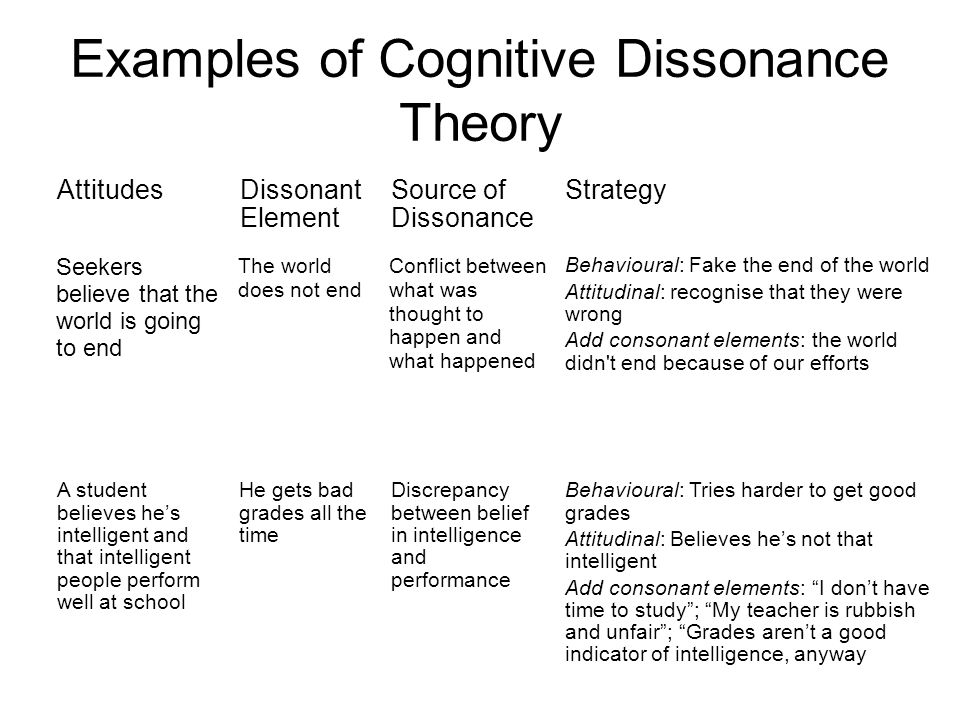

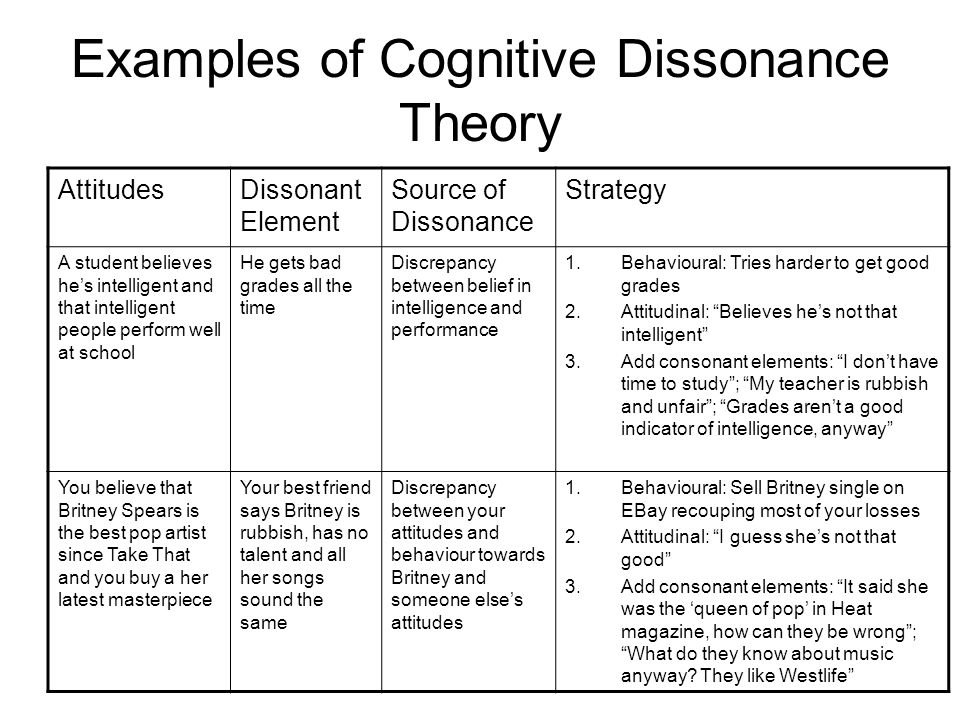

According to cognitive dissonance theory, there is a tendency for individuals to seek consistency among their cognitions (i.e., beliefs, opinions). When there is an inconsistency between attitudes or behaviors (dissonance), something must change to eliminate the dissonance. In the case of a discrepancy between attitudes and behavior, it is most likely that the attitude will change to accommodate the behavior.

Two factors affect the strength of the dissonance: the number of dissonant beliefs, and the importance attached to each belief. There are three ways to eliminate dissonance: (1) reduce the importance of the dissonant beliefs, (2) add more consonant beliefs that outweigh the dissonant beliefs, or (3) change the dissonant beliefs so that they are no longer inconsistent.

Dissonance occurs most often in situations where an individual must choose between two incompatible beliefs or actions. The greatest dissonance is created when the two alternatives are equally attractive. Furthermore, attitude change is more likely in the direction of less incentive since this results in lower dissonance. In this respect, dissonance theory is contradictory to most behavioral theories which would predict greater attitude change with increased incentive (i.e., reinforcement).

Dissonance theory applies to all situations involving attitude formation and change. It is especially relevant to decision-making and problem-solving.

ExamplePrinciples- Dissonance results when an individual must choose between attitudes and behaviors that are contradictory.

- Dissonance can be eliminated by reducing the importance of the conflicting beliefs, acquiring new beliefs that change the balance, or removing the conflicting attitude or behavior.

- Brehm, J. & Cohen, A. (1962). Explorations in Cognitive Dissonance. New York: Wiley.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Festinger, L. & Carlsmith, J.M. (1959). Cognitive Consquences of Forced Compliance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58, 203-210. [available at http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Festinger]

- Wickland, R. & Brehm, J. (1976). Perspectives on Cognitive Dissonance. NY: Halsted Press.

http://books.nap.edu/books/0309049784/html/99.html#pagetop

http://www.afirstlook.com/edition_9/theory_resources/by_theory/Cognitive_Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance: Definition, effects, and examples

Cognitive dissonance is the discomfort a person feels when their behavior does not align with their values or beliefs. It can also occur when a person holds two contradictory beliefs at the same time.

It can also occur when a person holds two contradictory beliefs at the same time.

Cognitive dissonance is not a disease or illness. It is a psychological phenomenon that can happen to anyone. American psychologist Leon Festinger first developed the concept in the 1950s.

Read on to learn more about cognitive dissonance, including examples, signs a person might be experiencing it, causes, and how to resolve it.

A note about sex and gender

Sex and gender exist on spectrums. This article will use the terms “male,” “female,” or both to refer to sex assigned at birth. Click here to learn more.

Cognitive dissonance occurs when a person holds two related but contradictory cognitions, or thoughts. The psychologist Leon Festinger came up with the concept in 1957.

In his book A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, Festinger proposed that two ideas can be consonant or dissonant. Consonant ideas logically flow from one another, while dissonant ideas oppose one another.

For example, a person who wishes to protect other people and who believes that the COVID-19 pandemic is real might wear a mask in public. This is consonance.

If that same person believed the COVID-19 pandemic was real but refused to wear a mask, their values and behaviors would contradict each other. This is dissonance.

The dissonance between two contradictory ideas, or between an idea and a behavior, creates discomfort. Festinger argued that cognitive dissonance is more intense when a person holds many dissonant views, and those views are important to them.

It is not possible to observe dissonance, as it is something a person feels internally. As such, there is no set of external signs that can reliably indicate a person is experiencing cognitive dissonance.

However, Festinger believed that all people are motivated to avoid or resolve cognitive dissonance due to the discomfort it causes. This can prompt people to adopt certain defense mechanisms when they have to confront it.

These defense mechanisms fall into three categories:

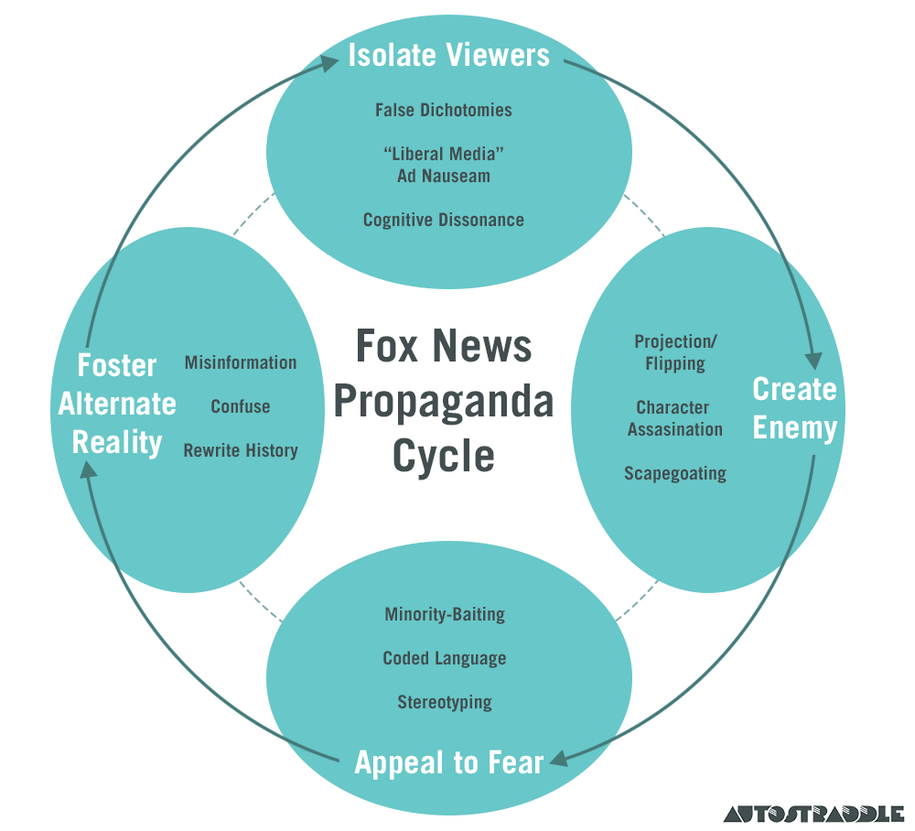

- Avoiding: This involves avoiding or ignoring the dissonance. A person may avoid people or situations that remind them of it, discourage people from talking about it, or distract themselves from it with consuming tasks.

- Delegitimizing: This involves undermining evidence of the dissonance. A person may do this by discrediting the person, group, or situation that highlighted the dissonance. For example, they might say it is untrustworthy or biased.

- Limiting impact: This involves limiting the discomfort of cognitive dissonance by belittling its importance. A person may do this by claiming the behavior is rare or a one-off event, or by providing rational arguments to convince themselves or others that the behavior is OK.

Alternatively, people may take steps to try to resolve the inconsistency. It is possible to resolve cognitive dissonance by either changing one’s behavior or changing one’s beliefs so they are consistent with each other.

Some examples of cognitive dissonance include:

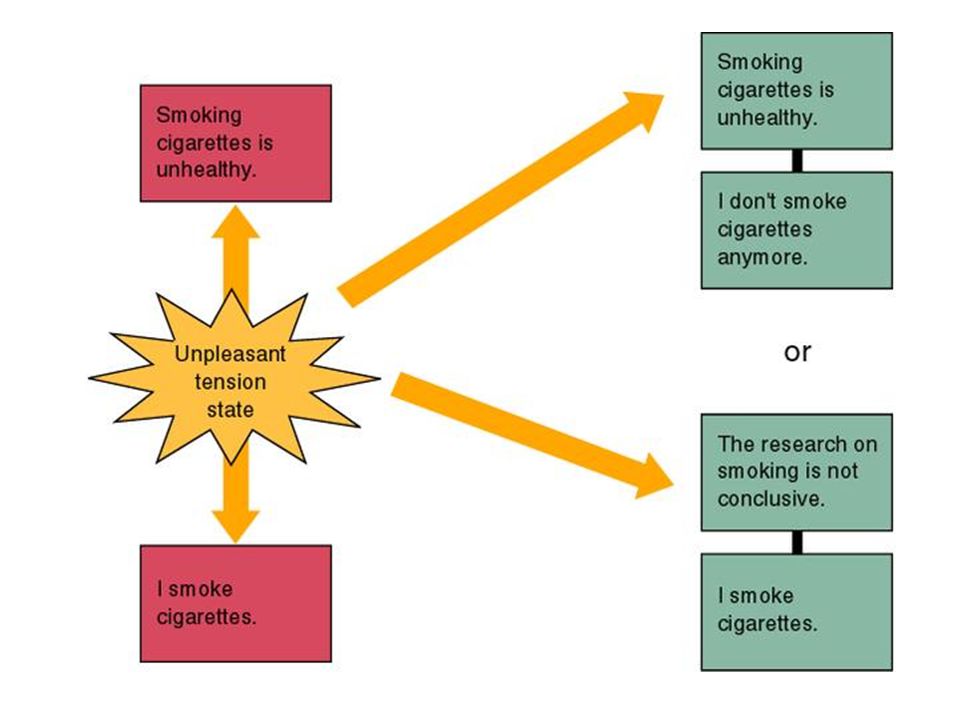

- Smoking: Many people smoke even though they know it is harmful to their health. The magnitude of the dissonance will be higher in people who highly value their health.

- Eating meat: Some people who view themselves as animal lovers eat meat and may feel discomfort when they think about where their meat comes from. Some researchers refer to this as the “meat paradox.”

- Doing household chores: A male might believe in equality of the sexes but then consciously or unconsciously expect their female partner to do most of the household labor or childrearing.

- Supporting fast fashion: A person might be aware of the effects of fast fashion on the environment and workers but still purchase cheap clothes from companies that engage in harmful practices.

Anyone can experience cognitive dissonance, and sometimes, it is unavoidable. People are not always able to behave in a way that matches their beliefs.

People are not always able to behave in a way that matches their beliefs.

Some factors that can cause cognitive dissonance include:

- Forced compliance: A person may have to do things they disagree with as part of a job, to avoid bullying or abuse, or to follow the law.

- Decision-making: Everyone has limited choices. When a person must make a decision among several options they do not like or agree with, or they only have one viable option, they may experience cognitive dissonance.

- Effort: People tend to value things they work hard for highly, even if those things contradict a person’s values. This may be because viewing something negatively after putting in a lot of hard work would cause more dissonance. So people are more likely to view difficult tasks positively, even if they do not morally agree with them.

Another factor that can create cognitive dissonance is addiction. A person might not want to engage in dissonant behavior, but addiction can make it feel physically and mentally difficult to bring their behavior into alignment with their values.

Cognitive dissonance can affect people in a wide range of ways. The effects may relate to the discomfort of the dissonance itself or the defense mechanisms a person adopts to deal with it.

The internal discomfort and tension of cognitive dissonance could contribute to stress or unhappiness. People who experience dissonance but have no way to resolve it may also feel powerless or guilty.

Avoiding, delegitimizing, and limiting the impact of cognitive dissonance may result in a person not acknowledging their behavior and thus not taking steps to resolve the dissonance. In some cases, this could cause harm to themselves or others.

However, cognitive dissonance can also be a tool for personal and social change. Drawing a person’s attention to the dissonance between their behavior and their values may increase their awareness of the inconsistency and empower them to act.

For example, a 2019 study notes that dissonance-based interventions may be helpful for people with eating disorders. This approach works by encouraging patients to say things or role-play behaviors that contradict their beliefs about food and body image. This creates dissonance.

This approach works by encouraging patients to say things or role-play behaviors that contradict their beliefs about food and body image. This creates dissonance.

The theory behind this approach is that in order to resolve the dissonance, a person’s implicit beliefs about their body and thinness will change, reducing their desire to limit their food intake.

The study found that this intervention was effective for heterosexual women but less effective for nonheterosexual women for reasons that are unclear.

The most effective way to resolve cognitive dissonance is for a person to ensure that their actions are consistent with their values, or vice versa.

A person can achieve this by:

- Changing their actions: This involves changing behavior so it matches a person’s beliefs. Where a full change is not possible, a person could make compromises. For instance, a person who cares about the environment but works for a company that pollutes might advocate for change at work, if they cannot leave their job.

- Changing their thoughts: If a person often behaves in a way that contradicts their beliefs, they may come to question how important that belief is or find that they no longer believe it. Alternatively, they might add new beliefs that bring their actions more closely in line with their thinking.

- Changing their perception of the action: If a person cannot or does not want to change the behavior or beliefs that cause dissonance, they may view the behavior differently instead. For example, a person who cannot afford to buy from sustainable brands might forgive themselves for this and acknowledge that they are doing the best they can.

Cognitive dissonance is not a mental health condition, and a person does not necessarily need treatment for it. However, if a person finds that they have difficulty stopping a behavior or thinking pattern that is causing them distress, they can seek support from a doctor or therapist.

A person may wish to consider this if:

- they have an addiction

- the behavior causes problems at work, at school, or in relationships

- they feel stressed, anxious, or low

- they feel overwhelming guilt or shame

Cognitive dissonance occurs when a person’s behavior and beliefs do not complement each other or when they hold two contradictory beliefs. It causes a feeling of discomfort that motivates people to try to feel better.

It causes a feeling of discomfort that motivates people to try to feel better.

People may do this via defense mechanisms, such as avoidance. Alternatively, they may reduce cognitive dissonance by being mindful of their values and pursuing opportunities to live those values.

A person who feels defensive or unhappy might consider the role cognitive dissonance might play in these feelings. If they are part of a wider problem that is causing distress, people may benefit from speaking with a therapist.

Cognitive dissonance theory - Psychologos

Leon Festinger - creator of the theory of cognitive dissonance

The theory of cognitive dissonance is one of the "correspondence theories" based on attributing to the individual the desire for a coherent and ordered perception of his attitude to the world. The concept of "cognitive dissonance" was first introduced by Leon Festinger, a student of Kurt Lewin, in 1956 to explain changes in opinions and beliefs as a way to eliminate semantic conflict situations.

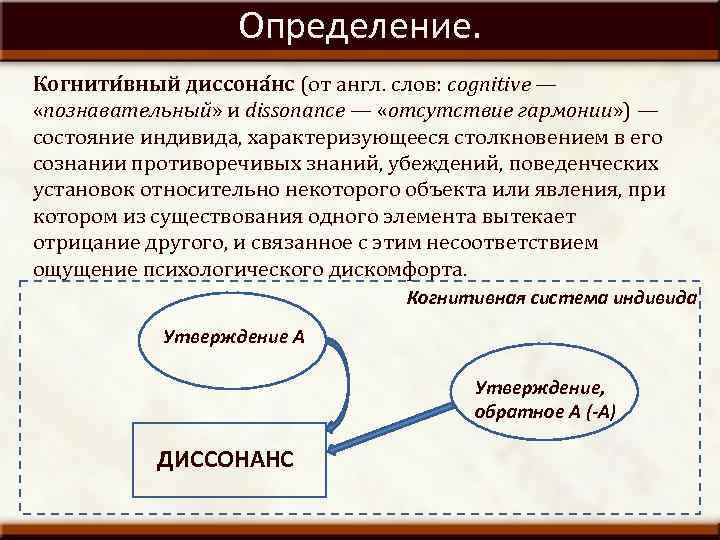

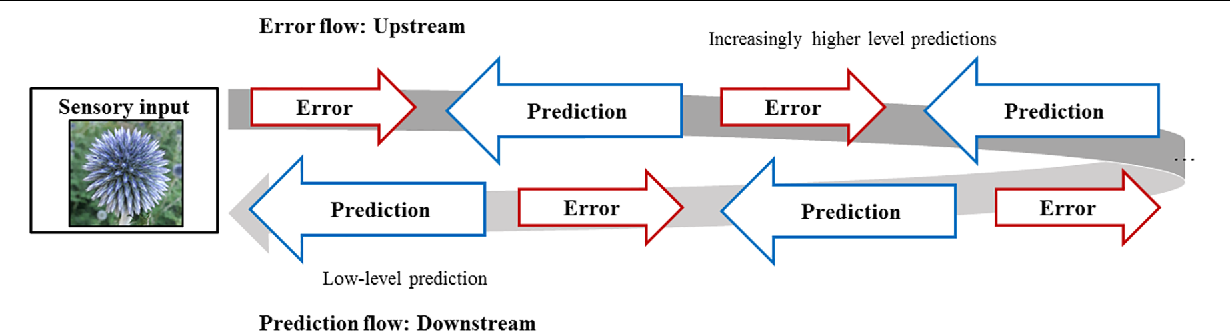

In the theory of cognitive dissonance, logically contradictory knowledge about the same subject is assigned the status of motivation, designed to ensure the elimination of the feeling of discomfort that arises when confronted with contradictions by changing existing knowledge or social attitudes. It is believed that there is a complex of knowledge about objects and people, called the cognitive system, which can be of varying degrees of complexity, consistency and interconnectedness. At the same time, the complexity of a cognitive system depends on the quantity and variety of knowledge included in it. According to the classical definition of L. Festinger, cognitive dissonance is a discrepancy between two cognitive elements (cognitions) - thoughts, experience, information, etc. - in which the denial of one element follows from the existence of another, and the feeling of discomfort associated with this discrepancy, otherwise speaking, a feeling of discomfort arises when logically contradictory knowledge about the same phenomenon, event, object collides in the mind. The theory of cognitive dissonance characterizes ways to eliminate or smooth out these contradictions and describes how a person does this in typical cases.

The theory of cognitive dissonance characterizes ways to eliminate or smooth out these contradictions and describes how a person does this in typical cases.

Leon Festinger Introduction to the theory of dissonance

It has long been noted that any person strives to preserve the inner harmony he has achieved. His views and attitudes tend to be combined into a system characterized by the consistency of its constituent elements. Of course, it is not difficult to find exceptions to this rule. Thus, a certain person may believe that black Americans are no worse than white fellow citizens, but this same person would prefer that they not live in his immediate neighborhood. Or another example: someone may think that children should behave quietly and modestly, but he also feels obvious pride when his beloved child energetically attracts the attention of adult guests. Such discrepancies between beliefs and actual behavior (and they can sometimes take quite dramatic forms) are of scientific interest mainly because they contrast sharply with the popular opinion about the tendency towards internal consistency between cognitive elements. Nevertheless - and this is a fact that has been firmly established by a variety of studies - the interconnected attitudes of a person strive precisely for consistency.

Nevertheless - and this is a fact that has been firmly established by a variety of studies - the interconnected attitudes of a person strive precisely for consistency.

There is also consistency between what a person knows and believes and what he does.

For example, a person convinced that a university education is a model of the highest quality education will in every way encourage his children to go to university. A child who knows that punishment will inevitably follow an offense will try not to commit it, or at least try to hide what he has done. All this is so obvious that we take examples of such behavior for granted. Our attention is primarily drawn to various kinds of exceptions to generally consistent behavior. A person may be aware of the harm of smoking to his health, but continue to smoke; many people commit crimes, fully aware that the probability of punishment for these crimes is very high.

Taking the individual's striving for internal coherence as a given, what can be said about such exceptions? Very rarely, cases of inconsistency are recognized by the subject himself as contradictions in his system of knowledge. Much more often the individual makes more or less successful attempts to somehow rationalize such a contradiction. Thus, a person who continues to smoke, knowing that it is harmful to his health, can rationalize his behavior in several ways. He may feel that the pleasure he gets from smoking is too great to forfeit, or that the changes in the smoker's health are not as fatal as doctors claim, because he is still alive and well. And finally, if he stops smoking, he may put on weight, which is also bad for health. Thus, he quite successfully harmonizes his smoking habit with his beliefs. However, people are not always so successful in trying to rationalize their behavior; for one reason or another, attempts to ensure consistency may fail. This is where a contradiction arises in the system of knowledge, which inevitably leads to the appearance of psychological discomfort.

Much more often the individual makes more or less successful attempts to somehow rationalize such a contradiction. Thus, a person who continues to smoke, knowing that it is harmful to his health, can rationalize his behavior in several ways. He may feel that the pleasure he gets from smoking is too great to forfeit, or that the changes in the smoker's health are not as fatal as doctors claim, because he is still alive and well. And finally, if he stops smoking, he may put on weight, which is also bad for health. Thus, he quite successfully harmonizes his smoking habit with his beliefs. However, people are not always so successful in trying to rationalize their behavior; for one reason or another, attempts to ensure consistency may fail. This is where a contradiction arises in the system of knowledge, which inevitably leads to the appearance of psychological discomfort.

So, we have come to formulate the main provisions of the theory. However, before doing so, I would like to clarify some terms. First of all, let's replace the word inconsistency with a term of lesser logical connotation, namely, the term dissonance.

First of all, let's replace the word inconsistency with a term of lesser logical connotation, namely, the term dissonance.

Similarly, instead of the word correspondence, I will use the more neutral term consonance. A formal definition of these concepts will be given below.

So, I want to formulate the main hypotheses as follows.

- The occurrence of dissonance, causing psychological discomfort, will motivate the individual to try to reduce the degree of dissonance and, if possible, achieve consonance.

- In the event of dissonance, in addition to striving to reduce it, the individual will actively avoid situations and information that may lead to its increase.

Before proceeding to a detailed analysis of the theory of dissonance, it is necessary to explain the nature of dissonance as a psychological phenomenon, the nature of the concept associated with it, as well as the possibilities of its application and development. The main hypotheses formulated above are a good starting point for this. Their interpretation has an extremely general meaning, so the term dissonance can be freely replaced by another concept of a similar nature, for example, hunger, frustration or disequilibrium. At the same time, the hypotheses themselves will fully retain their meaning.

Their interpretation has an extremely general meaning, so the term dissonance can be freely replaced by another concept of a similar nature, for example, hunger, frustration or disequilibrium. At the same time, the hypotheses themselves will fully retain their meaning.

I suggest that dissonance, that is, the existence of contradictory relationships between individual elements in a knowledge system, is itself a motivating factor. Cognitive dissonance can be understood as a condition that leads to actions aimed at reducing it (for example, hunger causes activity aimed at satisfying it). This is a completely different kind of motivation than what psychologists are used to dealing with. But, as we shall see later, this is an extremely powerful motivating factor.

By the term knowledge, I will understand any opinion or belief of an individual about the world around him, about himself, about his own behavior.

The emergence and persistence of dissonance

When and why does dissonance occur? Why do people do things that are not in line with their thoughts, that are contrary to the beliefs that are part of their value system? The answer to this question can be found in the analysis of the two most typical situations in which there is at least a momentary dissonance with the knowledge, opinion or idea of a person regarding his own behavior.

Firstly, these are situations when a person becomes an eyewitness to unpredictable events or when some new information becomes known to him.

For example, a subject is planning a picnic trip in full confidence that the weather will be warm and sunny. However, before the very departure, it may start to rain. So, knowing that it's raining will conflict with his plans to go out of town.

Or another example. Imagine that a person, completely convinced of the inefficiency of an automatic transmission, accidentally stumbles upon an article with a convincing description of its advantages. And again, in the system of knowledge of the individual, even if for a short moment, there will be dissonance.

Even in the absence of new, unforeseen events or information, dissonance is undoubtedly an everyday phenomenon. Very few things in the world are completely black or completely white. Very few situations in life are so obvious that opinions about them are not to some extent a mixture of contradictions. Thus, an American Republican farmer may disagree with his party's position on agricultural prices. A person buying a new car may prefer the economy of one model while lusting after the design of another. An entrepreneur who wants to profitably invest free funds knows well that the result of his investment depends on economic conditions that are beyond his personal control. In any situation that requires a person to formulate his opinion or make a choice, a dissonance is inevitably created between the awareness of the action being taken and those opinions known to the subject that testify in favor of a different scenario. The range of situations in which dissonance is almost inevitable is quite wide, but our task is to investigate the circumstances under which dissonance, once it has arisen, persists for some time, that is, to answer the question under what conditions dissonance ceases to be fleeting. phenomenon. To do this, consider the various possible ways in which dissonance can be reduced.

Thus, an American Republican farmer may disagree with his party's position on agricultural prices. A person buying a new car may prefer the economy of one model while lusting after the design of another. An entrepreneur who wants to profitably invest free funds knows well that the result of his investment depends on economic conditions that are beyond his personal control. In any situation that requires a person to formulate his opinion or make a choice, a dissonance is inevitably created between the awareness of the action being taken and those opinions known to the subject that testify in favor of a different scenario. The range of situations in which dissonance is almost inevitable is quite wide, but our task is to investigate the circumstances under which dissonance, once it has arisen, persists for some time, that is, to answer the question under what conditions dissonance ceases to be fleeting. phenomenon. To do this, consider the various possible ways in which dissonance can be reduced. And as an example, let's use the case of a heavy smoker who once faced information about the dangers of smoking.

And as an example, let's use the case of a heavy smoker who once faced information about the dangers of smoking.

He may have read about it in a newspaper or magazine, heard from friends or a doctor. This new knowledge will, of course, be at odds with the fact that he continues to smoke. If the dissonance reduction hypothesis is correct, what would be the behavior of our imaginary smoker in this case?

First, he can change his behavior, that is, stop smoking, and then his idea of his new behavior will be consistent with the knowledge that smoking is harmful to health.

Secondly, he may try to change his knowledge about the effects of smoking, which sounds rather strange, but it captures the essence of what is happening well. He may simply stop acknowledging that smoking is harmful to him, or he may try to find information that shows some benefit from smoking, thereby reducing the significance of information about its negative consequences. If this individual can change his system of knowledge in any of these ways, he can reduce or even completely eliminate the dissonance between what he does and what he knows.

Clearly enough, the smoker in the example above may have difficulty trying to change his behavior or his knowledge. And this is precisely the reason that dissonance, once it has arisen, can persist for a long time. There is no guarantee that a person will be able to reduce or eliminate the resulting dissonance. A hypothetical smoker may find that the process of quitting is too painful for him to endure. He may try to find specific facts or other people's opinions that smoking is not that harmful, but these searches may also end in failure. Thus, this individual will be in a position where he will continue to smoke, at the same time well aware that smoking is harmful. If such a situation causes discomfort in the individual, then his efforts aimed at reducing the existing dissonance will not stop.

Definitions of concepts: dissonance and consonance

The remainder of this chapter will be devoted to a more formal presentation of the theory of dissonance. I will try to formulate the position of this theory in the most precise and unambiguous terms. But since the ideas that underlie this theory are still far from final definition, some ambiguities will be inevitable.

But since the ideas that underlie this theory are still far from final definition, some ambiguities will be inevitable.

The terms dissonance and consonance define the type of relationship that exists between pairs of "elements". Therefore, before we determine the nature of these relations, it is necessary to define the elements themselves precisely.

These elements refer to what the individual knows about himself, about his behavior, and about his environment. These elements are therefore knowledge. Some of them relate to knowing oneself: what the individual does, what he feels, what his needs and desires are, what he is in general, and so on. Other elements of knowledge concern the world in which he lives: what gives a given individual pleasure and what pain, what is insignificant and what is important, etc.

The term knowledge has been used so far in a very broad sense to include phenomena not usually associated with the meaning of this word, such as opinions. A person forms an opinion only if he believes that it is true and, therefore, purely psychologically does not differ from "knowledge" as such. The same can be said about beliefs, values, or attitudes that serve to achieve certain goals. This by no means means that there are no important differences between these heterogeneous terms and phenomena. Some of these differences will be listed below. But for the purposes of a formal definition, all these phenomena are "elements of knowledge", and between pairs of these elements there can be relations of consonance and dissonance.

A person forms an opinion only if he believes that it is true and, therefore, purely psychologically does not differ from "knowledge" as such. The same can be said about beliefs, values, or attitudes that serve to achieve certain goals. This by no means means that there are no important differences between these heterogeneous terms and phenomena. Some of these differences will be listed below. But for the purposes of a formal definition, all these phenomena are "elements of knowledge", and between pairs of these elements there can be relations of consonance and dissonance.

In other words, the elements of knowledge correspond for the most part to what a person actually does or feels and to what actually exists in his environment. In the case of opinions, beliefs, and values, reality can be what others think or do; in other cases, the real may be what a person experiences or what others tell him.

Irrelevant relationships

Two elements may simply have nothing in common. In other words, under such circumstances, when one cognitive element does not intersect with another element anywhere, these two elements are neutral, or irrelevant, in relation to each other.

In other words, under such circumstances, when one cognitive element does not intersect with another element anywhere, these two elements are neutral, or irrelevant, in relation to each other.

The focus of our attention will be only those pairs of elements between which there are relations of consonance or dissonance.

Relevant relationships: dissonance and consonance

Two elements are dissonant with respect to each other if, for one reason or another, they do not correspond to each other.

We can now move on to attempt a more formal conceptual definition.

Let's consider two elements that exist in human knowledge and are relevant to each other. Dissonance theory ignores the existence of all other cognitive elements that are relevant to either of the two elements being analyzed, and considers only those two elements separately. Two elements taken separately are in a dissonant relationship if the negation of one element follows from the other. We can say that X and Y are in a dissonant relationship if non-X follows from Y. So, for example, if a person knows that there are only friends in his environment, but, nevertheless, feels fear or uncertainty, this means that there is a dissonant relationship between these two cognitive elements. Or another example: a person, having large debts, acquires a new car; in this case, the corresponding cognitive elements will be dissonant with respect to each other. Dissonance may exist due to experience or expectations, or because of what is considered appropriate or accepted, or for any of a variety of other reasons.

We can say that X and Y are in a dissonant relationship if non-X follows from Y. So, for example, if a person knows that there are only friends in his environment, but, nevertheless, feels fear or uncertainty, this means that there is a dissonant relationship between these two cognitive elements. Or another example: a person, having large debts, acquires a new car; in this case, the corresponding cognitive elements will be dissonant with respect to each other. Dissonance may exist due to experience or expectations, or because of what is considered appropriate or accepted, or for any of a variety of other reasons.

Motivations and desires can also be factors in determining whether two elements are dissonant or not. For example, a person playing cards for money can continue to play and lose, knowing that his partners are professional players. This last knowledge would be dissonant with the realization of his own behavior, namely that he continues to play. But in order to define these elements as dissonant in this example, it is necessary to accept with a sufficient degree of probability that this individual is striving to win. If, for some strange reason, this person wants to lose, then this relationship would be consonant.

If, for some strange reason, this person wants to lose, then this relationship would be consonant.

I will give a number of examples where the dissonance between two cognitive elements arises for various reasons.

- Dissonance may occur due to logical incompatibility. If an individual believes that in the near future man will land on Mars, but at the same time believes that people are still not able to make a spacecraft suitable for this purpose, then these two knowledges are dissonant with respect to each other. The negation of the content of one element follows from the content of another element on the basis of elementary logic.

- Dissonance may arise due to cultural practices. If a person at a formal banquet holds a chicken leg in his hand, the knowledge of what he is doing is dissonant with respect to the knowledge that determines the rules of formal etiquette during a formal banquet. Dissonance arises for the simple reason that it is this culture that determines what is decent and what is not.

In another culture, these two elements may not be dissonant.

In another culture, these two elements may not be dissonant. - Dissonance can occur when one specific opinion is part of a more general opinion. So. if a person is a Democrat but votes for a Republican candidate in a given presidential election, the cognitions corresponding to these two sets of opinions are dissonant with each other, because the phrase "to be a Democrat" includes, by definition, the need to keep candidates democratically parties.

- Dissonance can arise from past experiences. If a person gets caught in the rain and yet hopes to stay dry (without an umbrella), then the two knowledges will be dissonant with each other, because he knows from past experience that one cannot stay dry standing in the rain. If one could imagine a person who has never been exposed to rain, then the indicated knowledge would not be dissonant.

These examples are sufficient to illustrate how the conceptual definition of dissonance can be used empirically to decide whether two cognitive elements are dissonant or consonant. Of course, it is clear that in any of these situations there may be other elements of knowledge that may be in consonant relationship with any of the two elements in the pair in question. However, a relation between two elements is dissonant if, by ignoring all other elements, one of the elements of the pair leads to the negation of the value of the other.

Of course, it is clear that in any of these situations there may be other elements of knowledge that may be in consonant relationship with any of the two elements in the pair in question. However, a relation between two elements is dissonant if, by ignoring all other elements, one of the elements of the pair leads to the negation of the value of the other.

Degree of dissonance

One obvious factor that determines the degree of dissonance is the characteristics of the elements between which the dissonant relationship occurs. If two elements are dissonant with respect to each other, then the degree of dissonance will be directly proportional to the importance of these cognitive elements. The more significant the elements are for the individual, the greater will be the degree of dissonance between them. So, for example, if a person gives ten cents to a beggar, although he sees that this beggar is unlikely to really need money, the dissonance that arises between these two elements is rather weak. Neither of these two cognitive elements is important enough for a given individual. A much greater dissonance arises, for example, if a student does not strive to prepare for a very important exam, although he knows that his level of knowledge is clearly inadequate for passing the exam. In this case, the elements that are dissonant with respect to each other are much more important for this individual, and, accordingly, the degree of dissonance will be much greater.

Neither of these two cognitive elements is important enough for a given individual. A much greater dissonance arises, for example, if a student does not strive to prepare for a very important exam, although he knows that his level of knowledge is clearly inadequate for passing the exam. In this case, the elements that are dissonant with respect to each other are much more important for this individual, and, accordingly, the degree of dissonance will be much greater.

We can confidently assume that in life it is very rare to find any system of cognitive elements in which dissonance is completely absent. For almost any action a person might take or any feeling they might experience, there will almost certainly be at least one cognitive element that is in dissonance with this "behavioral" element.

Even quite trivial knowledge, such as the awareness of the need for a Sunday walk, is very likely to have some elements that are dissonant with this knowledge. A person who goes for a walk may be aware that some urgent business awaits him at home, or, for example, while walking, he notices that it is going to rain, and so on. In short, there are so many other cognitive elements that are relevant to any given element that some degree of dissonance is common.

In short, there are so many other cognitive elements that are relevant to any given element that some degree of dissonance is common.

Let us now consider a situation of the most general kind in which dissonance or consonance can arise. Assuming for the time being, for operational purposes, that all elements relevant to the cognitive element in question are equally important, we can formulate a general hypothesis. The degree of dissonance between this particular element and all other elements of the individual's cognitive system will directly depend on the number of those relevant elements that are dissonant with respect to the element in question. Thus, if the vast majority of relevant elements are consonant with, say, a behavioral element of a cognitive system, then there will be little dissonance with that behavioral element. If the proportion of elements that are consonant with respect to a given behavioral element is much smaller than the proportion of elements that are in a dissonant relationship with this element, then the degree of dissonance will be much higher. Of course, the degree of general dissonance will also depend on the importance or value of those relevant elements that have a consonant or dissonant relationship with the element in question.

Of course, the degree of general dissonance will also depend on the importance or value of those relevant elements that have a consonant or dissonant relationship with the element in question.

Reducing dissonance

The existence of dissonance gives rise to the desire to reduce, and if possible, completely eliminate dissonance. The intensity of this desire depends on the degree of dissonance. In other words, dissonance operates in exactly the same way as motive, need, or tension. The presence of dissonance leads to actions aimed at reducing it, just as, for example, the feeling of hunger leads to actions aimed at eliminating it. The greater the degree of dissonance, the greater will be the intensity of the action aimed at reducing dissonance, and the more pronounced will be the tendency to avoid any situations that might increase the degree of dissonance.

In order to concretize our reasoning as to how the desire to reduce dissonance can manifest itself, it is necessary to analyze the possible ways in which the resulting dissonance can be reduced or eliminated. In a general sense, if dissonance occurs between two elements, then this dissonance can be eliminated by changing one of these elements. What matters is how these changes could be implemented. There are many possible ways in which this can be achieved, depending on the type of cognitive elements involved in a given relationship and on the overall cognitive content of a given situation.

In a general sense, if dissonance occurs between two elements, then this dissonance can be eliminated by changing one of these elements. What matters is how these changes could be implemented. There are many possible ways in which this can be achieved, depending on the type of cognitive elements involved in a given relationship and on the overall cognitive content of a given situation.

Altering behavioral cognitions

When dissonance occurs between an environmental cognition and a behavioral cognition, it can only be resolved by changing the behavioral cognition so that it becomes consonant with the environmental element. The simplest and easiest way to achieve this is to change the action or feeling that this behavior represents. Accepting that knowledge is a reflection of reality, we believe that if an individual's behavior changes, then the cognitive element (or elements) corresponding to this behavior changes in a similar way. This method of reducing or eliminating dissonance is very common. Our behavior and feelings often change in response to new information. If a person went out of town for a picnic and noticed that it was starting to rain, he may well just return home. There are quite a few people who gave up tobacco permanently as soon as they found out that it is very unhealthy.

Our behavior and feelings often change in response to new information. If a person went out of town for a picnic and noticed that it was starting to rain, he may well just return home. There are quite a few people who gave up tobacco permanently as soon as they found out that it is very unhealthy.

However, it is far from always possible to eliminate the dissonance or even significantly reduce it, only by changing the corresponding action or feeling. The difficulties associated with changing behavior may be too great, or, for example, the change itself, carried out in order to eliminate some dissonance, may, in turn, give rise to a whole host of new contradictions. These issues will be discussed in more detail below.

Changing the cognitive elements of the environment

Just as it is possible to change behavioral cognitions by changing the behavior they reflect, it is sometimes possible to change environmental cognitions by changing their respective situation. Of course, this process is more difficult than behavior change, for the simple reason that it requires a sufficient degree of control over the environment, which is quite rare.

Of course, this process is more difficult than behavior change, for the simple reason that it requires a sufficient degree of control over the environment, which is quite rare.

Changing the environment to reduce dissonance is much easier when the dissonance is related to the social environment than when it is related to the physical environment.

If a cognitive element changes, but some reality that it represents in the individual's mind remains unchanged, then means of ignoring or counteracting the real situation must be used.

For example, a person may change his mind about a certain political figure, even if his behavior and political situation remain unchanged. Usually, in order for this to happen, it is enough for a person to find people who will agree with him and will support his new opinion. In general, approval and support from other people is necessary to form an idea of social reality. This is one of the main ways in which knowledge can be changed. It is easy to see that in cases where such social support is needed, the presence of dissonance and, as a result, the desire to change the cognitive element lead to different social processes.

It is easy to see that in cases where such social support is needed, the presence of dissonance and, as a result, the desire to change the cognitive element lead to different social processes.

Adding new cognitive elements

So, we have established that in order to completely eliminate dissonance, it is necessary to change certain cognitive elements. It is clear that this is not always possible. But even if the dissonance cannot be completely eliminated, it can always be reduced by adding new cognitive elements to the individual's knowledge system.

For example, if there is dissonance between the cognitions about the harms of smoking and quitting smoking, then the overall dissonance can be reduced by adding new cognitions that are consistent with the fact of smoking. Then, in the presence of such dissonance, a person can be expected to actively search for new information that could reduce the overall dissonance. At the same time, he will avoid information that could increase the existing dissonance. It is easy to guess that this individual will get satisfaction from reading any material that calls into question the harm of smoking. At the same time, he will critically perceive any information confirming the negative effects of nicotine on the body.

It is easy to guess that this individual will get satisfaction from reading any material that calls into question the harm of smoking. At the same time, he will critically perceive any information confirming the negative effects of nicotine on the body.

Resistance to dissonance reduction

If no cognitive elements of the individual's knowledge system offered resistance to change, then there would be no reason for dissonance to arise. A momentary dissonance might arise, but if the cognitive elements of a given system do not resist change, then the dissonance will be immediately eliminated. Consider the main sources of resistance to dissonance reduction.

Dissonance Growth Limits

The maximum dissonance that can exist between any two elements is determined by the amount of resistance to change of the least stable element. As soon as the degree of dissonance reaches its maximum value, the least persistent cognitive element will change, thereby eliminating the dissonance.

This does not mean that the degree of dissonance will often approach this maximum possible value. When strong dissonance arises, the degree of which is less than the amount of resistance to change inherent in any of its elements, the reduction of this dissonance for the overall cognitive system may well be achieved by adding new cognitive elements. Thus, even in the presence of very strong resistance to change, the overall dissonance in the system can be kept at a fairly low level.

As an example, consider a person who has spent a significant amount of money on an expensive new car. Imagine that after making this purchase, he discovers that the engine of this car is not working well and that it will be very expensive to repair it. Moreover, it turns out that the operation of this model is much more expensive than the operation of other cars, and on top of that, his friends say that this car is simply tasteless, not to say ugly. If the degree of dissonance becomes large enough, that is, correlated with the amount of resistance to change in the least stable element (which in this situation is most likely to be a behavioral element), then this individual can, in the end, sell the car, despite all the inconvenience and financial losses. associated with it.

associated with it.

Now let's consider the opposite situation, where the degree of dissonance for the individual who bought a new car was large enough, but still less than the maximum possible dissonance (that is, less than the amount of resistance to change inherent in the least change-resistant cognitive element). None of the existing cognitive elements would therefore change, but this individual could keep the degree of general dissonance fairly low by adding new knowledge that is consonant with owning a new car. This individual might conclude that the power and performance of a car is more important than its economy and design. He begins to drive faster than usual, and is completely convinced that the ability to develop high speed is the most important characteristic of the car. With such knowledge, this individual might well succeed in keeping the dissonance at a negligible level.

Conclusion

The main essence of the theory of dissonance that we have described is quite simple and, in brief, is as follows:

- There may be dissonant or incongruent relationships between cognitive elements.

- The appearance of dissonance causes a desire to reduce it and try to avoid its further increase.

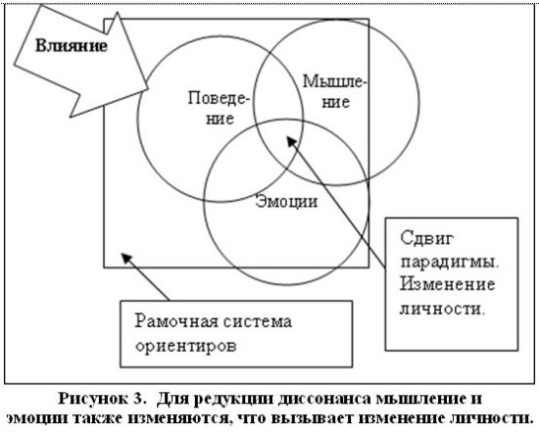

- Manifestations of this striving consist in a change in behavior, a change in attitude, or in a deliberate search for new information and new opinions about the judgment or object that has generated the dissonance.

Cognitive dissonance: what it is, examples, how to recognize it, how to overcome it

“I have cognitive dissonance,” we hear when describing any discrepancy between expectation and reality. This term has already become so widely used that not everyone thinks about its true meaning. Let's figure it out.

The author of the article is Angelina Duka, Ph.D. Advertising on RBC www.adv.rbc.ru

What is cognitive dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is an internal conflict that occurs in a person when conflicting beliefs collide. This dissonance causes a feeling of tension; a person experiences unpleasant emotions: anxiety, anger, shame, guilt - and will strive to get rid of discomfort in various ways. The concept of "cognitive dissonance" came to us from social psychology.

The concept of "cognitive dissonance" came to us from social psychology.

Theory of cognitive dissonance

The concept of cognitive dissonance was first introduced by the social psychologist Leon Festinger. He suggested that in the presence of conflicting beliefs, people would experience emotional discomfort. In his study of rumor belief, Festinger concluded that people always strive for an internal balance between personal motives that determine their behavior and information received from outside. Festinger's theory describes how people try to rationalize their behavior. Dissonance occurs when a person simultaneously encounters two incompatible, but equally significant judgments - cognitions. What it is? Sometimes thoughts are meant by cognitions, but in fact this concept is much broader: thoughts, ideas, opinions, value judgments should be included here. In some situations, they provide mental stability, protecting us from intense experiences. However, sometimes this protection is achieved in a peculiar way - by self-deception.

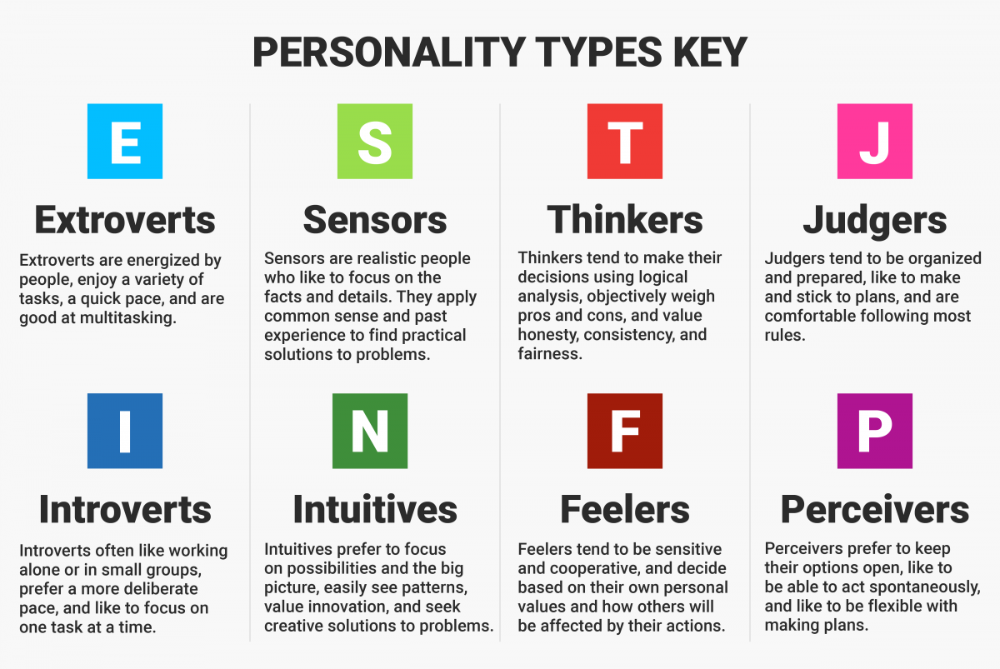

Does everyone experience cognitive dissonance the same way? No. Different people have different tolerances for uncertainty, so the degree of dissonance experienced will vary in intensity. The strength of dissonance is also affected by how strongly personal value beliefs are affected.

A frame from the TV series The Queen's Move

© Kinopoisk

Why cognitive dissonance occurs

Social behavior researchers Anthony Pratkanis and Elliot Aronson suggested that the mental activity of any person is largely determined by two principles that explain the irrationality of some actions.

The Principle of Thinking Patterns

Our brain cuts costs where possible. We strive to preserve the so-called cognitive energy, reducing its consumption to a minimum and using mental stereotypes wherever possible. This principle has both positive and negative effects. On the one hand, we, for example, create algorithms for solving typical problems and thereby simplify our work. On the other hand, in order to simplify complex problems, we often choose not a justified conclusion, but one that does not require deep reflection. Figuratively speaking, we are looking for keys not where we lost them, but where it is brighter.

On the other hand, in order to simplify complex problems, we often choose not a justified conclusion, but one that does not require deep reflection. Figuratively speaking, we are looking for keys not where we lost them, but where it is brighter.

Critical thinking requires additional resources, just as breaking any formed habit requires effort. Ignoring a comprehensive assessment of the situation, some repeat past mistakes many times and bring themselves into a state of debilitating stress.

The principle of rationalization of one's behavior, or the principle of self-explanation

It is common for any of us to give our actions a reasonable justification so that they seem logical both to ourselves and to our environment. Self-explanation acts as a guideline, as an ideological basis: “I do this because ...” - the continuation of the phrase will be different for everyone. A person must perceive his own behavior as reasonable and understandable - otherwise there is a threat to the integrity of his "I". However, the way we explain our actions does not always correspond to reality: very often, trying to calm ourselves, we wishful thinking through self-deception and rationalization.

However, the way we explain our actions does not always correspond to reality: very often, trying to calm ourselves, we wishful thinking through self-deception and rationalization.

These principles illustrate how a person rationalizes their behavior to avoid discomfort.

Shot from the movie "1+1"

© Kinopoisk

Examples of cognitive dissonance

Let's look at a simple example of how you can encounter cognitive dissonance. Choosing, say, a car, we compare different models and make a choice in favor of one of them. We are happy with our purchase and believe we made the best choice possible. If, after buying a car, we come across information that calls into question the correctness of our decision, then we will ignore it, even if it is true. Or we will justify ourselves by saying, "My car is better anyway." Or, talking about other cars, we will recall examples of how bad they are in operation, look for confirmation on forums, among friends. Thus, we strive to save ourselves from discomfort and maintain a positive attitude towards ourselves. At the same time, finding information confirming the correctness of our choice, we will certainly notice it and experience positive emotions, since we will unconsciously perceive it as speaking in favor of our positive self-image.

At the same time, finding information confirming the correctness of our choice, we will certainly notice it and experience positive emotions, since we will unconsciously perceive it as speaking in favor of our positive self-image.

Russian classical literature is full of examples of cognitive dissonance when the hero makes a difficult choice. Thus, in The Quiet Don, Sholokhov, through the prism of the families of the Melekhovs, Korshunovs and other characters, shows how individuals make difficult decisions at critical moments and cope with cognitive dissonance.

How to overcome cognitive dissonance

Typical behaviors can help you understand how to deal with the discomfort of cognitive dissonance.

Avoiding or discounting factual information

This strategy helps people continue to maintain behaviors with which they do not fully agree (for example, I know that smoking is bad, but I continue to do so). To reduce cognitive dissonance, a person can limit access to new information that does not correspond to his beliefs, devalue these facts, perceiving them as false, avoid studying additional sources and situations in which alternative points of view can be encountered.

Rationalization

Justifying oneself, trying to make sure that there is no internal conflict. People begin to seek support among those who share similar views, or try to convince the other that the new information is inaccurate; looking for ways to justify behavior that goes against their beliefs. Unfortunately, often behind explanations that seem rational to us, in fact, there are irrational beliefs containing logical errors that are not supported by facts, and this causes us suffering.

Changing one's behavior

Discomfort can lead a person to change their behavior so that actions are consistent with their beliefs. As a result of cognitive dissonance, many people are faced with a conflict of values, resolving which they can bring positive changes to their lives, move closer to the ideal in accordance with which they want to live - this is the case when cognitive dissonance can have a positive impact. For example, a person eats a lot of sugary fatty foods every day, while he is at risk of diabetes and he is aware of the consequences. Feeling discomfort from cognitive dissonance, he eventually changes his behavior: he corrects his diet, thereby taking a step towards his value - health.

Feeling discomfort from cognitive dissonance, he eventually changes his behavior: he corrects his diet, thereby taking a step towards his value - health.

A still from the film Bridget Jones's Diary

© Kinopoisk

The development of critical thinking

It is possible to establish the truth by analyzing the arguments of each side of cognitive dissonance.

To do this, you need to answer the question of whether it is logical to think so, what is the logic of judgments.

Then, with the help of empirical facts, one should weigh the two points of view and ask oneself:

- what proves my point;

- that refutes it;

- what evidence (facts, arguments) can be given in favor of the opposite point of view;

- what do I get when I think so;

- Do my thoughts help me get what I want?

As you might guess, the first two strategies are not very productive - they may bring temporary relief, but they will not relieve discomfort.