Gabapentin for anxiety and depression

Gabapentin for Depression, Mania, and Anxiety

Gabapentin is an anticonvulsant prescription drug that goes by several brand names including, Neurontin, Gralise, Gabarone, and Fanatrex. It was approved by the FDA in December 1993 for the following main uses.

Controlling certain types of seizures in people who have epilepsy

Relieving nerve pain (think: burning, stabbing, or aches) from shingles

Calming restless legs syndrome

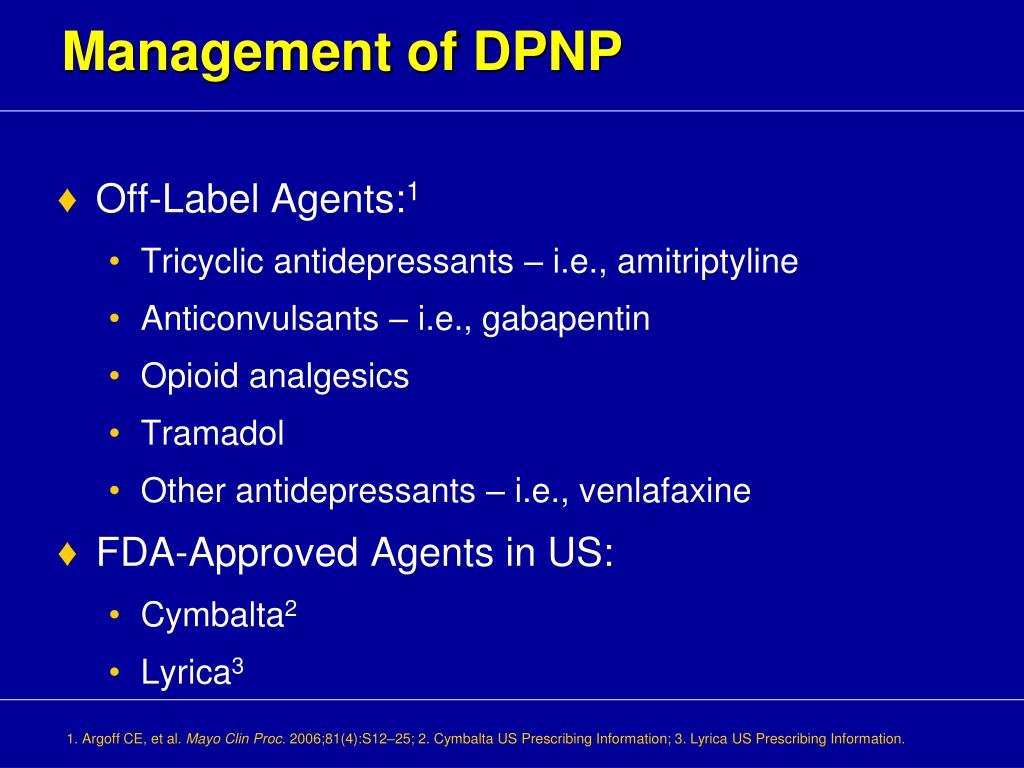

But since it’s been available, gabapentin has also been used off-label in psychiatry to treat patients with treatment-resistant mood and anxiety disorders as well as alcohol-withdrawal and post-traumatic stress. It works by decreasing abnormal excitement in the brain for seizures and changing the way the body senses pain for nerve pain. Researchers don’t know exactly how it works for psychiatric conditions. (

*Note: Some states have recently classified gabapentin as a controlled substance due to the potential for it to be abused and contribute to death from overdose. )

Treatment with Gabapentin: Important Things to Know Before Taking Gabapentin

Before you start gabapentin therapy, you should have a thorough medical exam to rule out any medical issues. This includes any blood or urine tests. Medical evaluations are important as gabapentin can induce hormonal imbalances. Like any other drug, you should not take gabapentin if you’re allergic to it.

There are side effects—more on that in a minute. But a few of the most important things your doctor will want to find out before prescribing gabapentin is if you have or have had any of the following:

Diabetes

Drug or alcohol addiction

Kidney problems (or if you’re on dialysis)

Liver or heart disease

Lung disease (see the warning above on respiratory issues)

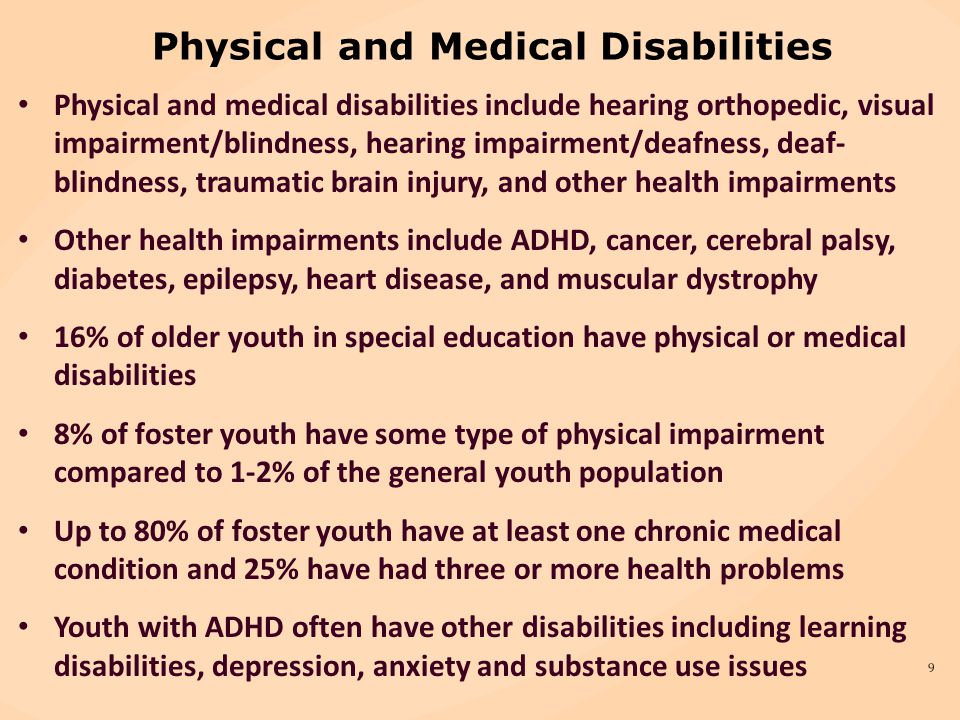

Mood disorders, depression or bipolar; or if you’ve ever thought about suicide or attempted suicide

Seizures (unless, of course, you’re taking it for seizures)

You should also know that not enough studies have been done to understand the exact risks of gabapentin if you’re pregnant or breastfeeding.

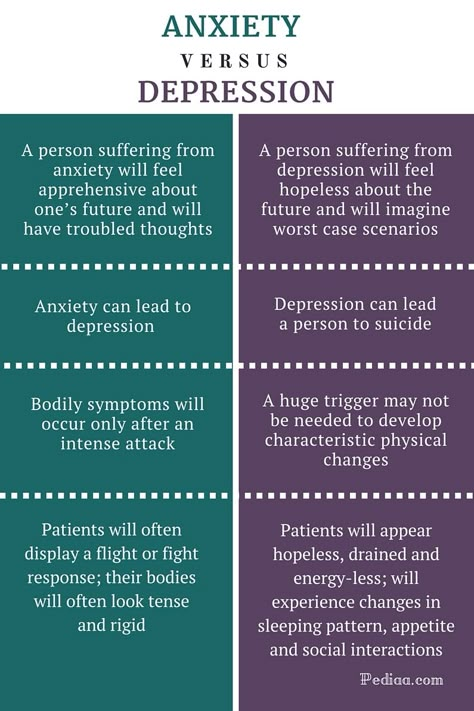

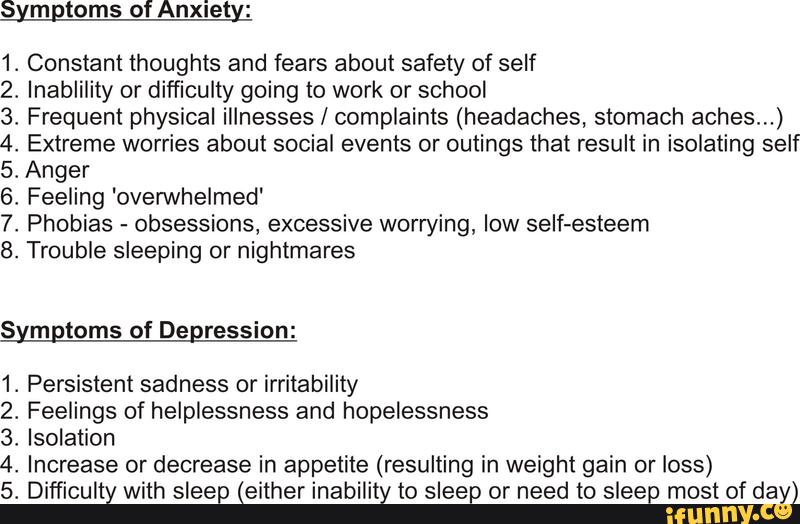

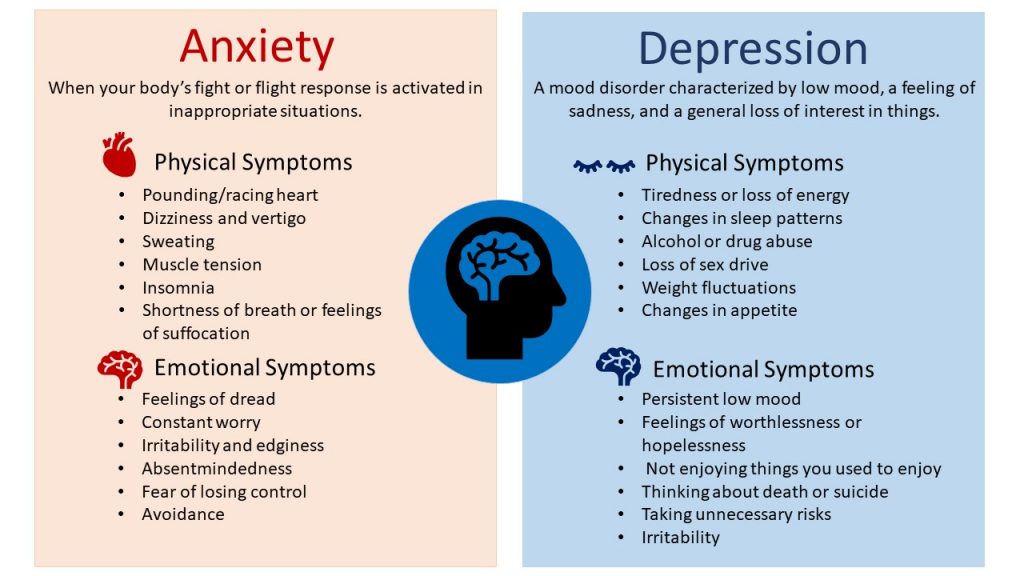

How Gabapentin Is Used to Treat Anxiety Mood Disorders Like Depression

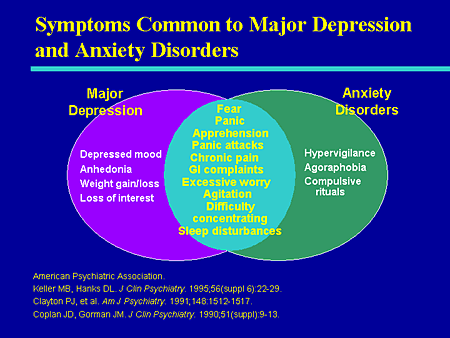

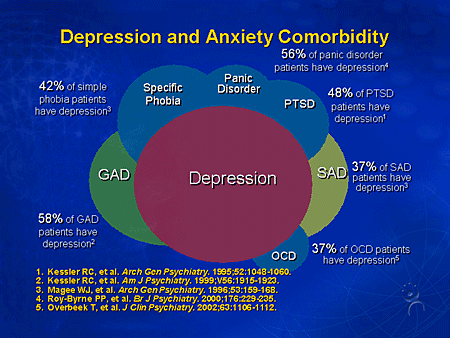

Gabapentin isn’t usually used to treat anxiety alone. More often, it’s given to ease anxiety symptoms for someone who also has depression or bipolar disorder. (Anxiety is commonly comorbid with depression and bipolar.) The reason is that it may not be effective for just anxiety. A close look comparing seven different clinical trials on how successful gabapentin is for anxiety shows that gabapentin may be better than a placebo to treat generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), but not much better. Results may be slightly more promising for social anxiety disorder.

The clinical trials for treating depression with gabapentin are also pretty lackluster. To date, there are no scientific studies showing it’s effective—either on its own or as part of some other therapy. Still, there is some anecdotal evidence that it’s helpful, especially with patients who don’t seem to improve with more standard antidepressants.

More specifically, can it prevent future episodes of mania and depression? Right now, there is no good evidence that gabapentin can be used for treating people with bipolar disorder. High-quality, randomized controlled studies found that gabapentin was not effective.¹˒²

Gabapentin and Alcohol Use Disorder

Gabapentin may be helpful in treating alcohol use disorder and withdrawal. Between 2004 and 2010, The Veterans Affairs Department conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized dose-ranging trial of 150 men and women over 18, struggling with alcohol dependence.³ The results of the study showed that gabapentin (particularly the 1800 mg dosage) was effective in safely treating alcohol dependence and relapse-related symptoms including insomnia, dysphoria, and cravings.

Side Effects of Gabapentin

As with any medication, there may be some side effects. Some of these are more likely to happen when you first start taking the medication.

Common side effects:

Less common side effects:

Abnormal stool (black and tarry)

Chest pain

Chills

Cough

Depression, irritability, or other mood or mental changes

Fever

Fatigue

Memory loss

Pain (or swelling) in the arms or legs

Painful or difficult urination

Shortness of breath

Sore throat/swollen glands

Common side effects for those with mental illness:

Agitation

Decreased libido

Depersonalization

Increased libido

Mania

Paranoia

Gabapentin Dosage and Administration

Typically, your doctor will prescribe 300 mg once a day, usually in the evening, to start. The dose will then be increased every three to five days. Some people will take 600 mg/day, others will increase to 3,600 mg/day—the maximum dose approved by the FDA.

The dose will then be increased every three to five days. Some people will take 600 mg/day, others will increase to 3,600 mg/day—the maximum dose approved by the FDA.

If used as a mood stabilizer or anti-depressant, the dose is usually between 900 and 2,000 mg a day. But, it may also be increased for better results. Some people see improvement in their symptoms about a week after starting treatment. Others need about a month before they see significant improvement.

Gabapentin has a half-life of about six hours, so it must be taken three to four times a day.

How To Discontinue Gabapentin

Like other psychotropic drugs, you should ease off gabapentin gradually. There are some known withdrawal symptoms. This mostly comes from people who take high doses of the drug and suddenly stop. You should only abruptly discontinue this drug because of a serious side effect, and even then, it should be done with your doctor’s supervision and direction.

Gabapentin Overdose and Toxicity

It's possible to fatally overdose on gabapentin. Reports of gabapentin being abused alone, and with opioids, prompted the FDA to release a warning statement (in December 2019) about the fatal risk of respiratory depression. Signs of overdose include:

Reports of gabapentin being abused alone, and with opioids, prompted the FDA to release a warning statement (in December 2019) about the fatal risk of respiratory depression. Signs of overdose include:

If you suspect an overdose, you need immediate medical treatment. The only way to remove the drug is through kidney dialysis in the emergency room.

10 Most Common Questions About Gabapentin

Is there a generic version of gabapentin available? Since its manufacturer no longer has patent protection on the drug, there are generic versions on the market. They include Neurontin, Gralise, Gabarone, and Fanatrex.

How much does gabapentin cost? According to GoodRx.com, generic Gabapentin can cost between $7-$27 for ninety 100mg or 300mg capsules and between $14-$53 for ninety 400mg capsules.

What is the difference between gabapentin and other mood-stabilizing medications?This is kind of a trick question. Technically, even though we hear the term “mood stabilizer” quite often, especially in the context of bipolar disorder, the FDA doesn’t officially recognize the term.

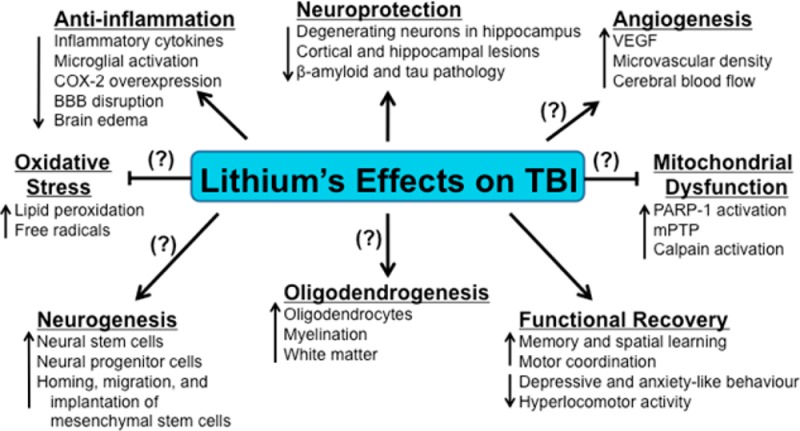

Not only that but even researchers and psychiatrists can’t come with a definition everyone agrees on. That said, lithium (which is probably the drug anyone with bipolar disorder is most familiar with) has significant differences from gabapentin. Lithium is in a class called bipolar disorder agents. Gabapentin is in a class called anticonvulsants. Their chemical structures are not the same and they work differently in the body. In addition to being used for bipolar, both have also been used for epilepsy.

Not only that but even researchers and psychiatrists can’t come with a definition everyone agrees on. That said, lithium (which is probably the drug anyone with bipolar disorder is most familiar with) has significant differences from gabapentin. Lithium is in a class called bipolar disorder agents. Gabapentin is in a class called anticonvulsants. Their chemical structures are not the same and they work differently in the body. In addition to being used for bipolar, both have also been used for epilepsy.How is gabapentin different from valproate and carbamazepine? There are claims that gabapentin was successful in helping with rapid cycling and mixed bipolar states in people who have not received relief from valproate or carbamazepine. It appeared that gabapentin helped more with anxiety and agitation than the other two drugs. Likewise, it has been shown to be beneficial with certain types of tardive dyskinesia.

Are there potential interaction issues for people taking carbamazepine, valproate or lithium? No interactions between gabapentin and valproate, carbamazepine or lithium have been reported.

Does gabapentin interact with any other prescriptions or over-the-counter medications, such as MAO inhibitors? There are only a few interaction issues that are known. Antacids have been known to decrease the absorption of the drug. Gabapentin could also increase the level of concentration of some oral contraceptives by up to 13 percent. As far as MAO’s, this particular combination doesn’t present any special issues, but you should always let your doctor and pharmacist know all the medications you are taking.

Are there any interaction issues between gabapentin and alcohol? Alcohol has been known to increase the discomfort of Gabapentin’s side effects.

Is it safe for a woman who is pregnant, about to become pregnant, or nursing to take gabapentin? The FDA placed gabapentin in pregnancy category C. According to studies done on animals, there has been evidence of fetal loss. However, there have been no studies done on humans.

Despite all this, experts believe that the benefits gained from taking gabapentin may outweigh its risks.

Despite all this, experts believe that the benefits gained from taking gabapentin may outweigh its risks.Can children and adolescents safely take gabapentin? What about the elderly? Gabapentin may be used to treat seizures in children as young as 3 years old. The dosages will be different from what you’d give an adult, and the doctor may specify a particular brand name, such as Neurontin. Similar to children, the elderly may start on a lower dose.

Why do doctors prescribe gabapentin when there are other mood-stabilizing medications that have been around for many years? True, there are medications that have been shown to be more effective in double-blind studies that are placebo-controlled. But there are two reasons why physicians prescribe Gabapentin over more established drugs. One: not everyone improves with the older, more established medications. Two: some people can’t deal with the side effects of the other drugs.

DISCLAIMER: The information contained in this article should NOT be used as a substitute for the advice of an appropriately qualified and licensed physician or other health care provider. This article mentions drugs that were FDA-approved and available at the time of publication and may not include all possible drug interactions or all FDA warnings or alerts. The author of this page explicitly does not endorse this drug or any specific treatment method. If you have health questions or concerns about interactions, please check with your physician or go to the FDA site for a comprehensive list of warnings.

This article mentions drugs that were FDA-approved and available at the time of publication and may not include all possible drug interactions or all FDA warnings or alerts. The author of this page explicitly does not endorse this drug or any specific treatment method. If you have health questions or concerns about interactions, please check with your physician or go to the FDA site for a comprehensive list of warnings.

Warning: The Food and Drug Administration issued a serious warning about gabapentin in 2019. According to the FDA, breathing difficulties may occur in patients who have underlying respiratory problems (or in the elderly) when gabapentin (Neurontin, Gralise, Horizant) or pregabalin (Lyrica, Lyrica CR) is taken with other medicines that depress the central nervous system. There is evidence of risk with gabapentinoids alone in otherwise healthy people too; though this evidence is not as strong and is still being monitored.

Additionally, note that there are not a lot of comprehensive studies that look at Gabapentin as a way to treat anxiety, mood disorders, or tardive dyskinesia (uncontrollable movements). As with any medication, always talk to your health care professional if you have any questions or concerns.

As with any medication, always talk to your health care professional if you have any questions or concerns.

- Pande AC, Crockatt JG, Janney CA, Werth JL, Tsaroucha G. Gabapentin in bipolar disorder: a placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive therapy. Gabapentin Bipolar Disorder Study Group. Bipolar Disord. 2000 Sep;2(3 Pt 2):249-55. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.20305.x. PMID: 11249802. Accessed October 22, 2020.

- Frye MA, Ketter TA, Kimbrell TA, Dunn RT, Speer AM, Osuch EA, Luckenbaugh DA, Cora-Ocatelli G, Leverich GS, Post RM. A placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000 Dec;20(6):607-14. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200012000-00004. PMID: 11106131. Accessed October 22, 2020.

- Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, Shadan F, Kyle M, Begovic A. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):70-77. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11950 Accessed October 22, 2020.

Notes: This article was originally published August 21, 2021 and most recently updated June 8, 2022.

Using Gabapentin for Anxiety and Depression

Did you know that Gabapentin might be helpful for depression and anxiety?

Gabapentin is an anticonvulsant drug that also goes by Neurontin, Gralise, or Gaborone. It’s initial purpose was to control certain types of seizures in people who have epilepsy, relieving nerve pain from shingles, or calming restless leg syndrome.

Gabapentin has also been used off-label as a treatment for anxiety disorders. It’s possible that your psychiatric provider may prescribe gabapentin to help alleviate some of the symptoms associated with these mental health disorders. Additionally, there is some evidence to suggest that gabapentin can be helpful for individuals who struggle with alcohol use disorders or alcohol dependence.

Let’s take a look at how gabapentin works and why you may be prescribed this medication for anxiety.

Want to speak 1:1 with an expert about your anxiety & depression?

Start with a free assessment

How does Gabapentin work?

Gabapentin is a synthetic version of the neurotransmitter GABA, which means it mimics the role GABA plays in the body. Neurotransmitters are chemicals that carry signals between nerve cells.

The GABA neurotransmitter can help slow down neurons firing in the brain. Gabapentin works in a similar way; it can help quiet the brain and decrease pain transmission in your nerves.

For seizures, gabapentin works by decreasing abnormal excitement in the brain. It can also change the way that the body processes pain, which can help alleviate pain caused by shingles.

While studies don’t typically show effectiveness for improving symptoms of depression, there is evidence that gabapentin may have some benefit for anxiety disorders. A rat study found that gabapentin produced behavioral changes suggestive of anxiolysis, or feelings of calmness.

Additionally, a case study of one individual found a clear inverse relationship between dosage of gabapentin and anxiety. The individual — who did not respond well to traditional antidepressant medications such as SSRIs — reported that her anxiety levels were very low on days when she took gabapentin.

So while there is some evidence that gabapentin can be used as a novel medication to treat anxiety and depression, there is not enough research to explain its therapeutic mechanisms.

Even so, your provider may determine that Gabapentin for anxiety or depression is worth prescribing. If so, here are some things you should know.

How to take Gabapentin for anxiety

If you are prescribed gabapentin for anxiety, you should follow the exact dosing prescribed by your provider — the dosing information provided below is for educational purposes only.

Gabapentin can come in a capsule, tablet, or oral solution, but you’ll likely be prescribed capsules to help with anxiety. It is usually taken with a full glass of water, with or without food.

It is usually taken with a full glass of water, with or without food.

Antacids should not be taken within two hours before or after using gabapentin. Antacids can make it harder for your body to absorb gabapentin, making it less effective.

Potential side effects of Gabapentin

As with any medication, side effects may occur when taking gabapentin for anxiety. The main side effects include:

- Dizziness

- Fatigue

- Agitation

- Changes in libido, or sex drive

- Tremors

- Unsteadiness

- Nystagmus (involuntary eye movement)

- Blurred vision

Some of these side effects may resolve after continued use, but if they become severe or long term, reach out to your psychiatric provider immediately.

Gabapentin prescriptions for anxiety

Since gabapentin is a prescription medication, you’ll need to get a prescription from a doctor or psychiatric provider — only after you’ve demonstrated symptoms of anxiety and have been screened for gabapentin allergies. Additionally, you may not be a candidate if you take other medications that have contraindications to gabapentin.

Additionally, you may not be a candidate if you take other medications that have contraindications to gabapentin.

Your provider will provide specific dosing instructions, including a guideline on how frequently you should take gabapentin for your anxiety. As Psycom explains, your dose may start small and increase over time. For anxiety, the dosage of gabapentin will often start at 300 mg once in the evening. The dose can then be increased every three to five days. Some people take 600 mg/day, others take 3,600 mg/day, the maximum dose approved by the FDA.

According to Psycom, gabapentin for depression may follow a different dosage pattern. Dosage of between 900 and 2,000 mg a day works as a mood stabilizer or antidepressant. Some people experience improvement within a week after treatment initiation, others need more time to feel significant symptom relief.

The difference in clinical results means it’s a little tricky to determine how quickly gabapentin might work to help your anxiety.

At Brightside, we use gabapentin alongside other medicines to treat:

- Generalized anxiety disorder

- Hard-to-treat depression

- Insomnia

- Nerve pain

- Panic disorder

- Social anxiety

Adding Gabapentin into your anxiety treatment plan

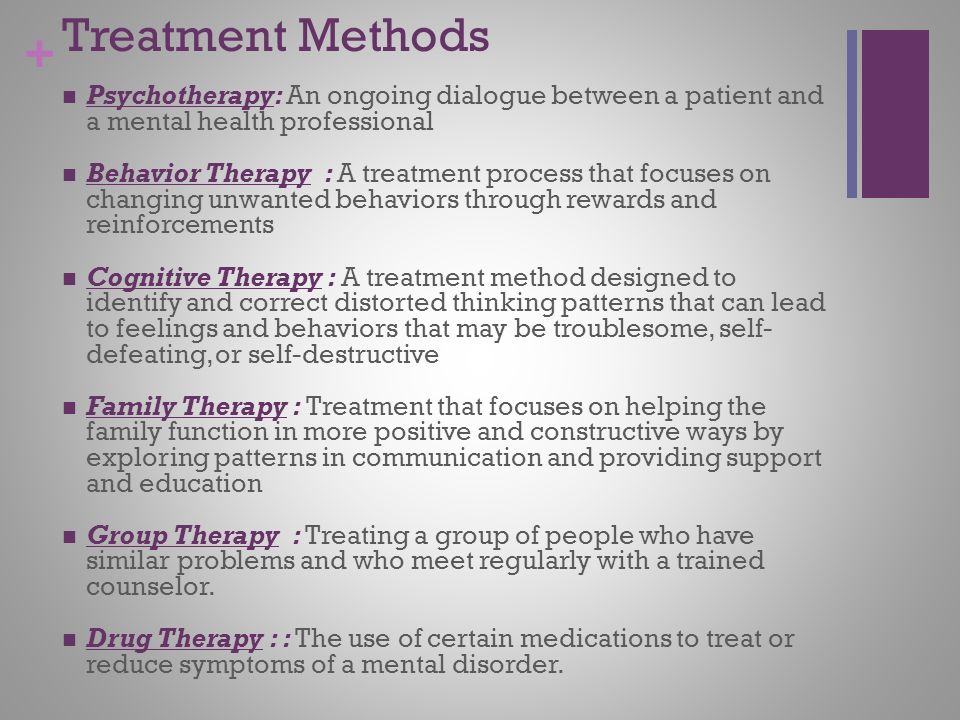

For anxiety or depression, Gabapentin is typically prescribed alongside other treatment options — here are the most common:

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI)

SSRI medications are commonly prescribed alongside gabapentin for depression and anxiety. SSRIs work by preventing the reabsorption of serotonin into your brain’s neurons, making the neurotransmitter more abundant. Serotonin is a chemical that is thought to regulate mood and anxiety levels.

There are many different types of SSRIs, but some common examples include Zoloft, Prozac, and Lexapro. SSRIs typically cause fewer side effects than many other types of antidepressants, which is one of the reasons why they’re so popular.

Talk Therapy

Therapy is widely delivered to treat anxiety and depression for those prescribed gabapentin, and it’s highly effective. Although there are many types of depression and anxiety therapy, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is particularly effective. Goal-oriented and structured, CBT addresses the source of irrational thought to alter unfavorable behaviors.

In fact, the most effective way to care for your mental health is to leverage a combination of medication and talk therapy — which enables a 60% better chance of recovery than just one treatment alone.

In conclusion

Gabapentin is an anticonvulsant medication that is prescribed for treating seizures and nerve pain associated with shingles. However, it also is known for producing anti-anxiolytic (anti-anxiety) effects, which is why gabapentin is often prescribed for treating anxiety.

Gabapentin is usually prescribed at a low dose to start but can be gradually increased as needed. While a psychiatric provider will likely not prescribe gabapentin for anxiety or depression as a first course of action, it may be used alongside other treatments to help improve symptoms.

A Brightside psychiatric provider can help you determine what treatment plan is right for you. We offer therapy and psychiatric care right from the comfort of home — including unlimited messaging with your provider and medications delivered right to your door.

Fill out your complimentary assessment to see how Brightside can help you find the right care plan.

Please note: Prescribing decisions are always at the discretion of the provider who abides by your state’s regulations and restrictions. Brightside’s providers can’t prescribe Gabapentin in the following states: Alabama, Kentucky, Michigan, North Dakota, Tennessee, Virginia, or West Virginia.

Sources:

Gabapentin Treatment for Alcohol Dependence: A Randomized Controlled Trial | NCBI

Gabapentin | MedlinePlus

The antiepileptic agent gabapentin (Neurontin) possesses anxiolytic-like and antinociceptive actions that are reversed by D-serine | National Library of Medicine

Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder with gabapentin | NCBI

Gabapentin | Michigan Medicine

Serotonin | Hormone Health Network

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) | Mayo Clinic

Gabapentin Therapy in Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review | NCBI

Gabapentin and pregabalin for bipolar disorder, anxiety and insomnia

Gabapentin is licensed in the US for the treatment of focal seizures and postherpetic neuralgia and in the UK for the treatment of focal seizures and neuropathic pain. Pregabalin has a similar indication and is also indicated for fibromyalgia in the US and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in the UK.

Pregabalin has a similar indication and is also indicated for fibromyalgia in the US and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in the UK.

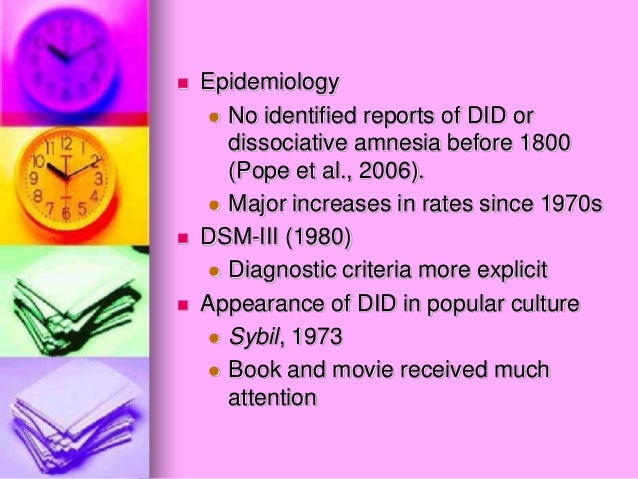

Put into practice at 1993, these drugs have become one of the most frequently prescribed drugs, with a significant proportion of prescriptions being off-label prescriptions. A 2002 American study [1] showed that 95% of gabapentin prescriptions are for off-label indications, in at least 10% of psychiatric cases. In the UK, at least half of all prescriptions for gabapentinoids are off-label, and one in five is co-prescribed with opioids. A 2021 study using the American electronic health record network Trinetx [2] showed that gabapentin was prescribed at least once in 13.6% of patients with bipolar disorder (BDD), 11.5% of patients with anxiety disorders, and 12.7 % of patients with insomnia; for pregabalin, these figures were 2.9%, 2.6%, 3.0% respectively.

Despite the widespread use of off-label gabapentin in bipolar disorder, the question of its effectiveness remains unclear. A 2011 meta-analysis of pharmacological treatments for acute mania found no superiority of gabapentin over placebo [3]. Systematic reviews of gabapentin treatment of psychiatric and/or substance use disorders have not shown conclusive evidence for its efficacy in bipolar disorder, but have identified possible efficacy in the treatment of anxiety disorders.

A 2011 meta-analysis of pharmacological treatments for acute mania found no superiority of gabapentin over placebo [3]. Systematic reviews of gabapentin treatment of psychiatric and/or substance use disorders have not shown conclusive evidence for its efficacy in bipolar disorder, but have identified possible efficacy in the treatment of anxiety disorders.

In addition to its licensed use for GAD in the UK, pregabalin is used to treat other anxiety disorders and acute anxiety conditions such as preoperative anxiety. The effectiveness of pregabalin for GAD has been established, but its effectiveness is unclear for other anxiety disorders such as social anxiety disorder. Gabapentinoids may also be useful in the treatment of insomnia, but again, firm evidence is lacking.

Overall, studies show that there is only limited evidence for the effectiveness of gabapentinoids in the disorders they are used to treat. Moreover, these drugs have potential risks, including a number of serious side effects, as well as abuse and dependence, which led to their reclassification as controlled drugs in the UK in 2019. In the US, pregabalin (but not gabapentin) has since is a federally controlled drug due to the risk of dependence and abuse.

In the US, pregabalin (but not gabapentin) has since is a federally controlled drug due to the risk of dependence and abuse.

A priori, due to their mode of action, gabapentinoids are attractive candidate molecules for use in psychiatry. They act primarily by inhibiting the activity of voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) by binding to the α2δ accessory subunit, which regulates channel traffic and function. Although the genes encoding the α2δ subunits have not yet been associated with psychiatric phenotypes, other VGCC genes, in particular CACNA1C, which encodes a protein of the same name, show strong transdiagnostic associations with various disorders, including bipolar disorder. Administration of calcium channel blockers, which block the α-1 subunit of L-type VGCC, is associated with a reduction in hospital admissions in patients with severe mental illness. Cellular calcium dysregulation has been observed in patients with bipolar disorder and some other psychiatric disorders.

Given the potential risks of gabapentinoids and their widespread off-label use, it is important to carefully assess the evidence base for their use. This systematic review and meta-analysis focuses on the efficacy and tolerability of gabapentin and pregabalin in the treatment of bipolar disorder, anxiety and insomnia.

Published studies were searched in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), EMBASE, MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process and PsycINFO in the time range from their inception to August 4, 2020. Unpublished studies were searched in international research registries ( ClinicalTrials.gov; ICTRP) and regulatory websites.

Of the 4268 studies initially identified, 70 studies were included in the review: 55 double-blind RCTs and 15 open-label studies. The risk of bias was unclear for most studies; in a significant proportion of studies, there was an increased risk of error due to dropout.

Four double-blind RCTs were found investigating the efficacy of gabapentin in bipolar disorder. 101 patients were randomized to receive gabapentin, 81 to placebo, 30 to lamotrigine, and 19- carbamazepine. The mean age of all randomized patients was 37.5 years, 64.1% were women.

101 patients were randomized to receive gabapentin, 81 to placebo, 30 to lamotrigine, and 19- carbamazepine. The mean age of all randomized patients was 37.5 years, 64.1% were women.

Three studies evaluated gabapentin in the treatment of acute bipolar disorder in heterogeneous groups of patients with manic/hypomanic, depressive and/or mixed symptoms. In each study, the efficacy of gabapentin was assessed using different outcome measures.

Gabapentin was significantly more effective than lamotrigine and carbamazepine in reducing depressive symptoms on the MMPI-2 depression subscale (50%, 33.5% and 13.6% reductions, respectively), but no difference in improvement on the MMPI mania subscale -2 was not observed. Based on the Global Clinical Impression Scale (CGI-BP), treatment response rates of 50% for lamotrigine, 33% for gabapentin, and 18% for placebo were observed in the clinical global bipolar version in the first phase of the study, but without clear statistical significance.

In a study investigating the addition of gabapentin to the main treatment, a significantly greater improvement in the total score on the YMRS Mania Rating Scale in the placebo group was reported, with no significant difference between groups on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D).

One long-term (1-year treatment) study of 25 bipolar patients in clinical remission (13 on gabapentin, 12 on placebo) showed a significant benefit of gabapentin versus placebo in terms of CGI.

Forty-two double-blind RCTs investigating anxiety disorders/conditions (GAD; social anxiety disorder; preoperative anxiety; PTSD; OCD; panic disorder) were selected. 3539 patients were randomized to receive pregabalin, 525 to gabapentin, 2280 to placebo and 937 to active comparators. The mean age of all randomized patients was 43 years, 60.4% were women. Data were analyzed on 5190 patients from eligible anxiety studies.

Gabapentinoids are more effective than placebo for a range of disorders on the anxiety spectrum.

Pregabalin is more effective than placebo in the treatment of GAD (SMD -0.37; 95% CI -0.45 to -0.29). The relative risk of withdrawal from the study for all reasons was comparable for pregabalin and placebo. Compared with placebo, pregabalin significantly reduced the relative risk of discontinuation due to failure (RR 0.44; 95% CI 0.28–0.70), but showed a trend towards an increased relative risk of discontinuation due to adverse events (RR 1, 30, 95% CI 0.99 - 1.71).

Pregabalin is more effective than placebo in treating exacerbations of social anxiety (SMD -0.25; 95% CI -0.45 to -0.04). There was no significant difference in the relative risk of dropping out of the study for all reasons or because of adverse events. Compared with placebo, pregabalin showed a trend towards a lower relative risk of dropout due to failure (RR 0.39; 95% CI 0.15 - 1.03).

A 14-week study of gabapentin in social anxiety disorder showed improvement over placebo on several rating scales. A 26-week study investigating pregabalin for relapse prevention found that a fixed dose of 450 mg/day reduced the overall relapse rate compared with placebo (27.5% vs. 43.8%, based on CGI criteria).

A 26-week study investigating pregabalin for relapse prevention found that a fixed dose of 450 mg/day reduced the overall relapse rate compared with placebo (27.5% vs. 43.8%, based on CGI criteria).

Compared to placebo, both pregabalin (SMD -0.55; 95% CI -0.92 to -0.18) and gabapentin (SMD -0.92; 95% CI -1.32 - -0.52) are more effective in reducing preoperative anxiety. Due to the heterogeneity of the studies, a subgroup analysis was performed based on empirically determined threshold doses of dose-response efficacy.

High doses (>600 mg) of gabapentin are effective in reducing preoperative anxiety (SMD -1.30; 95% CI -1.72 to -0.87), while low doses (600 mg) are ineffective. Due to the high degree of heterogeneity among studies in the high dose group, the validity of the estimate of the effect of high doses remains uncertain. Visual inspection of the gabapentin vs. placebo graph suggests possible effects from small trials, with larger effect sizes seen in high-dose gabapentin trials with smaller sample sizes. There was no significant difference between the low (≤150 mg) and high (300 mg) pregabalin dose subgroups. Interestingly, low dose pregabalin was more effective than placebo (SMD -0.29; 95% CI -0.54 - -0.05), while the high dose does not.

There was no significant difference between the low (≤150 mg) and high (300 mg) pregabalin dose subgroups. Interestingly, low dose pregabalin was more effective than placebo (SMD -0.29; 95% CI -0.54 - -0.05), while the high dose does not.

It is not possible to conduct a meta-analysis of the tolerability of pregabalin and gabapentin in studies of preoperative anxiety. The short evaluation time (lasting hours rather than weeks) means that dropouts have occurred in very few studies. In such cases, dropout was due to the practicalities of the preoperative procedures rather than the decision of the participants.

Three double-blind RCTs were included in the review, two of which evaluated the addition of pregabalin to the treatment of PTSD and OCD, and one evaluated the effect of gabapentin in the treatment of panic disorder. Pregabalin supplementation is more effective than placebo in chronic post-combat PTSD and in OCD refractory to SSRIs. However, eight weeks of flex-dose gabapentin is no more effective than placebo in patients with panic disorder.

Eight double-blind RCTs evaluated the efficacy of gabapentin in sleep disorders. In two studies, 111 patients were randomized to gabapentin and 60 to placebo (mean age 44.8 years; 44.9% women). In participants with alcohol dependence and related sleep disorders, gabapentin did not show improvement in sleep scores compared to placebo. The relative risk of withdrawal from the study for all reasons was comparable for gabapentin and placebo.

Only one double-blind RCT evaluated the efficacy of pregabalin (n=121) versus venlafaxine (n=125) and placebo (n=128) in the treatment of sleep disorders (mean age of all randomized patients 40.8 years, 60.7% women). Pregabalin significantly reduced sleep problems scores compared to placebo at weeks 4 and 8.

Compared to previous studies, this systematic review covers more disorders and databases, considers only double-blind RCTs to summarize evidence of efficacy, and includes unpublished data.

Review shows minimal evidence to support the use of gabapentinoids for bipolar disorder and insomnia.

Moderate effect size observed across the spectrum of anxiety disorders; a significant effect is observed in certain anxiety states; The effect of gabapentin on preoperative anxiety is dose dependent.

With regard to BAD, the small number of double-blinded RCTs investigating gabapentin and the lack of studies on pregabalin do not support evidence of efficacy of gabapentinoids. Quantitative synthesis was not performed due to the heterogeneity of the study population, study design, and outcome scoring systems. The evidence collected is inconclusive and does not justify the use of gabapentinoids in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

An analysis of anxiety-related studies showed a statistically significant effect size in favor of gabapentinoids across the spectrum of anxiety disorders/conditions. This transdiagnostic effect is explained by the fact that anxiety, anxiety proneness, and pathological anxiety are all mediated by the same neural network and common phenotype seen in anxiety disorders.

There is a dose-dependent effect of gabapentin on preoperative anxiety, with >600 mg required to treat acute anxiety. The analysis was performed post-hoc when examining significant study heterogeneity, and its findings should be used to develop hypotheses for future studies. The choice of dose cut-offs was based on empirical reports of dose-dependent effects in GAD, which is a limitation of this subgroup analysis.

In GAD, remission/moderate anxiety was observed at total daily doses of gabapentin ≥900 mg/day, recurrent severe anxiety at <600 mg/day. A similar approach was used for pregabalin, based on reports of differences in efficacy between 150 mg/day and 200–600 mg/day for GAD.

A meta-analysis of studies on alcohol-related insomnia found that gabapentin was no better than placebo. Gabapentinoids may improve sleep in patients with a range of clinical conditions, such as insomnia associated with GAD and neuropathic pain, but the extent to which direct or indirect effects influence sleep parameters in these conditions is unclear. While the studies of pregabalin for GAD included in this review reported improvements in HAM-A sleep, they were not included in the meta-analysis due to doubts about the validity of the HAM-A subscales for insomnia.

While the studies of pregabalin for GAD included in this review reported improvements in HAM-A sleep, they were not included in the meta-analysis due to doubts about the validity of the HAM-A subscales for insomnia.

On the one hand, there is a limited nature of evidence for the effectiveness of gabapentinoids, on the other hand, there is strong evidence for their side effects and potential harm. Gabapentinoids commonly cause central nervous system depressant side effects, such as drowsiness and dizziness, which increase the risk of accidental physical injury and traffic accidents. There is also growing concern about the addictive potential and harms of gabapentinoids when used with opioids.

An important weakness of the evidence is its methodological quality and the risk of bias in the studies. The prominent side effects of gabapentinoids make it difficult to blind study participants, possibly leading to an overestimation of effect sizes. Therefore, the results of studies indicating the effectiveness of gabapentinoids should be treated with caution, especially when such results justify their off-label use. Against this background, the widespread use of off-label gabapentinoids seems unreasonable and requires more careful study.

Against this background, the widespread use of off-label gabapentinoids seems unreasonable and requires more careful study.

Neurobiological and pharmacological considerations supporting the choice of drug target should never take precedence over empirical clinical evidence of efficacy and safety. However, they may be useful for further research.

The role of VGCC in psychiatric disorders is supported by genomic data. The strongest evidence is for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, with associations with VGCC seen in a range of psychiatric disorders (albeit not yet found in anxiety disorders). Genetic associations with VGCC are mainly associated with α-1 and β subunits; but we do not have reliable information about the genes of the α2δ subunits.

In addition, the desired nature and direction of manipulation required to achieve therapeutic benefit remains to be determined. While the current understanding of VGCC is based on channel blocking, alternative and more subtle approaches are likely to be useful as well.

For example, the VGCC genes encode several isoforms with different properties, including sensitivity to existing channel blockers, and with varying tissue expression. The impact of rare mutations also points to the need to modulate rather than simply block VGCC function in psychiatric disorders. In the case of CACNA1C, gain-of-function mutations cause Timothy Syndrome, which is characterized by autism, but autism is also known to occur with loss-of-function mutations. All of this highlights the need for therapeutic agents capable of fine-tuning function, perhaps by targeting specific isoforms or through homeostatic action, which should ultimately maximize clinical benefit and minimize side effects.

Targeting the α2δ subunits characteristic of gabapentinoids may lead to subtle modulation of VGCC function. α2δ subunits increase the density of VGCC on the plasma membrane, direct the traffic of these channels to subcellular sites, and enhance function by changing their biophysical properties. Gabapentin reduces the number of α2δ and α-1 subunits on the cell surface and attenuates VGCC activity, indicating its inhibitory role. However, the exact effect of gabapentin on calcium channels depends on the stoichiometry of the VGCC accessory subunits, which, like other VGCC subunits, vary in number in different tissues, due to which gabapentinoids may have different effects on VGCC in different cell types.

Gabapentin reduces the number of α2δ and α-1 subunits on the cell surface and attenuates VGCC activity, indicating its inhibitory role. However, the exact effect of gabapentin on calcium channels depends on the stoichiometry of the VGCC accessory subunits, which, like other VGCC subunits, vary in number in different tissues, due to which gabapentinoids may have different effects on VGCC in different cell types.

It is possible that the effect of gabapentinoids on anxiety is mediated by α2δ-dependent but VGCC-independent mechanisms. Notably, α2δ-1 interacts with NMDA receptors (NMDARs), promoting dendritic spine maturation and NMDAR traffic.

Thus, it is interesting not only to elucidate the clinical effect of gabapentinoids, but also to establish their molecular mechanisms of action in order to understand the pathophysiology and identify new therapeutic strategies. A strategy for personalized medicine should take into account genomic and other factors influencing VGCC function and psychiatric disorders.

Gabapentinoids are generally effective across the spectrum of anxiety disorders, and it is likely that this is due to pharmacological effects on transdiagnostic anxiety phenotypes mediated by α2δ-dependent mechanisms. Anxiety is the most common comorbid pathology in patients with bipolar disorder [4], which partly reflects a common genetic predisposition [5]. Comorbid anxiety is associated with greater symptom severity and worse clinical outcomes. To date, there are no clinical studies on the effectiveness of gabapentinoids in the treatment of anxiety in bipolar disorder. The development of treatments for “bipolar anxiety” using gabapentinoids or modified α2δ ligands may become a promising area of research in the future.

Systematic review and meta-analysis show that widespread psychiatric prescription of off-label gabapentinoids is not supported by reliable evidence, except for certain anxiety conditions. Thus, despite the attractive genetic and pharmacological rationale for their use, caution should be exercised until evidence of efficacy and safety is found. Presumably, it is possible to develop modified α2δ ligands that target specific subtypes or isoforms with a more favorable therapeutic profile.

Presumably, it is possible to develop modified α2δ ligands that target specific subtypes or isoforms with a more favorable therapeutic profile.

Translated by: Filippov D.S.

Source: Hong, J.S.W., Atkinson, L.Z., Al-Juffali, N. et al. Gabapentin and pregabalin in bipolar disorder, anxiety states, and insomnia: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and rationale. Mol Psychiatry (2021).

References:

[1] Hamer AM, Haxby DG, McFarland BH, Ketchum K. Gabapentin use in a managed Medicaid population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2002;8:266–71.

[2] Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236,379 COVID-19 survivors: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:416–27.

[3] Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, Rendell J, Brown R, Stockton S, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2011;378:1306–15.

Lancet 2011;378:1306–15.

[4] Spoorthy MS, Chakrabarti S, Grover S. Comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: an overview of trends in research. World J Psychiatry. 2019;9:7–29.

[5] Lopes FL, Zhu K, Purves KL, Song C, Ahn K, Hou L, et al. Polygenic risk for anxiety influences anxiety comorbidity and suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:298.

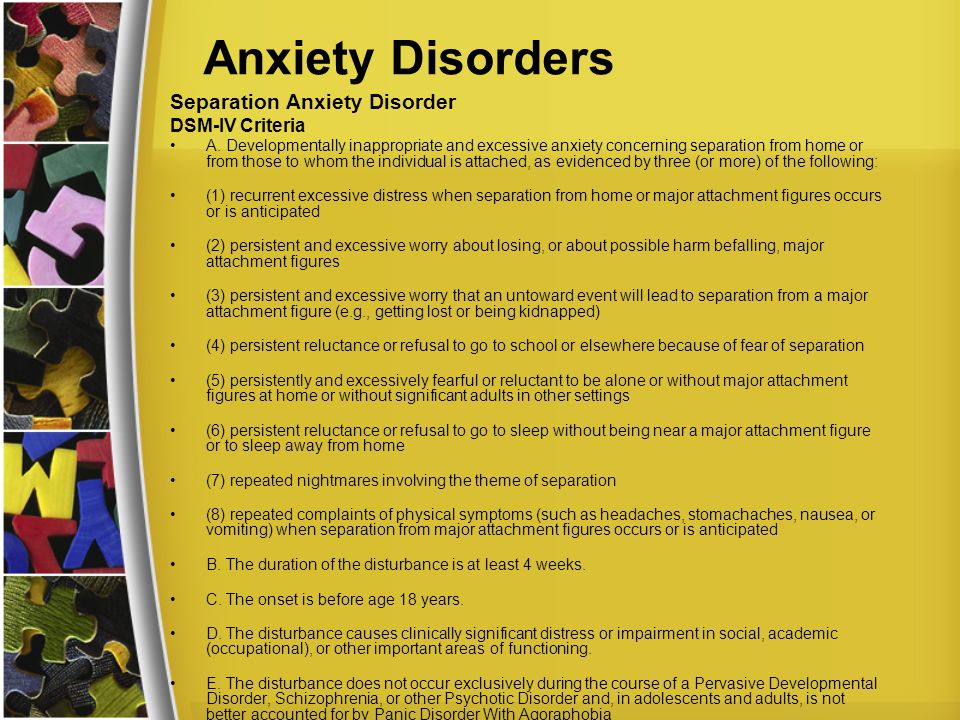

Therapy of anxiety disorders: a modern view on the problem

Summary. The International Classification of Diseases 10 group of anxiety disorders includes generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, specific phobias, and social anxiety disorder (F40 and F41). Anxiety disorders are very common in the general population and occur in every 5th inhabitant of developed countries throughout life. One of the most difficult to treat in this group is Generalized Anxiety Disorder, characterized by excessive worrying about various events or activities, resulting in significant distress and disruption of social, work, and daily functioning. The use of antidepressants is ineffective in about ⅓ of these patients. In modern clinical guidelines, other groups of drugs are indicated in first and second line therapy - anticonvulsants, atypical antipsychotics. Among them, an important place is occupied by pregabalin, a drug of the anticonvulsant group, which is also used for chronic pain syndrome. The article considers the current state of the problem of treating anxiety disorders and (using pregabalin as an example) the feasibility of using alternative drugs to antidepressants.

The use of antidepressants is ineffective in about ⅓ of these patients. In modern clinical guidelines, other groups of drugs are indicated in first and second line therapy - anticonvulsants, atypical antipsychotics. Among them, an important place is occupied by pregabalin, a drug of the anticonvulsant group, which is also used for chronic pain syndrome. The article considers the current state of the problem of treating anxiety disorders and (using pregabalin as an example) the feasibility of using alternative drugs to antidepressants.

Background

Anxiety disorders are among the most common mental health problems in the world. In addition, among all medical problems, anxiety also occupies a leading position in terms of prevalence. Within the framework of epidemiological studies, it is customary to talk about two variants of the prevalence of any condition - annual, that is, an assessment of this indicator in a small time slice (12-month prevalence), and lifelong - the proportion of people who have experienced this condition at least once. For the entire group of anxiety disorders, research has shown a 12-month prevalence of >15% and a lifetime prevalence of >20%.

For the entire group of anxiety disorders, research has shown a 12-month prevalence of >15% and a lifetime prevalence of >20%.

As a clear demonstration of the relevance of the problem, we present the results of a large-scale study on the assessment of the mental and somatic health of US residents "National Comorbidity Survey". Along with Framingham, this is one of the largest observational studies, the results of which are often used to evaluate epidemiological data and the relationship between various factors that affect health. According to him, the 12-month prevalence of anxiety disorders is 17.2%, which means that every 6th person in the United States develops an anxiety disorder within one year. The lifetime prevalence is 24.9%; this means that every 4th person during his life at least once encounters an anxiety disorder (Kessler R.C. et al., 1994). These data are approximately the same for both Caucasians and African Americans. Thus, with a sufficiently high degree of accuracy, they can be extrapolated to the Ukrainian population.

Analysis of World Health Organization data suggests that this group of mental health problems is the 6th most common cause of disability in both high-income, middle- and low-income countries, including Ukraine. For every 100 thousand inhabitants of the Earth, anxiety disorders account for 390 years of disability. Among women, anxiety disorders are responsible for 65% of all years of life lost (disabled) from all causes (Baxter A.J. et al., 2014).

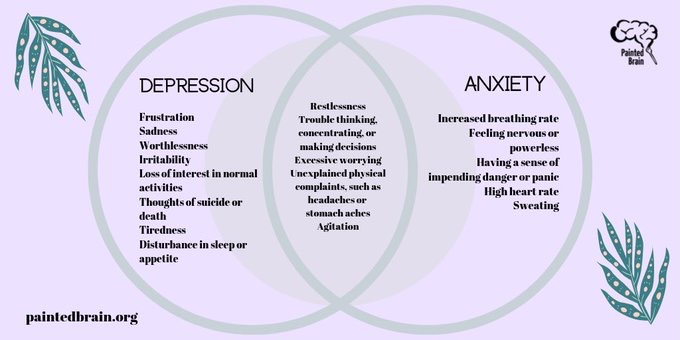

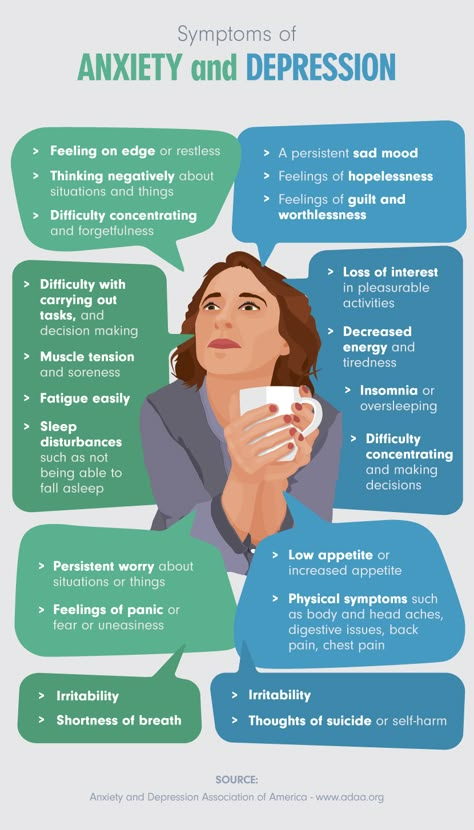

Among anxiety disorders, a special place is occupied by generalized anxiety disorder, which is characterized by excessive anxiety and feelings in relation to a large number of events or activities (for example, work), accompanied by severe anxiety, fatigue, irritability, difficulty concentrating, muscle tension and impaired sleep. This state of affairs leads to significant distress and difficulties in social, work or even normal daily functioning. For example, anxiety significantly complicates the performance of work duties, which can lead to job loss or provoke conflict in the family.

The sleep disturbance that often accompanies anxiety can be a serious problem in itself, as anxiety-induced insomnia is usually long-term and thus poorly controlled by benzodiazepines or their derivatives, as they are not recommended for long-term use. Another serious problem that deserves attention is a significant decrease in the quality of life of patients with anxiety. Given the gradual transition to patient-centered care, it is also recommended to use this indicator as a marker of the severity of the condition, in addition to standard diagnostic measures (clinical scales for assessing anxiety).

Studies have shown that anxiety is associated with a significant reduction in quality of life, especially when taking into account the widely used SF-36 quality of life scale. To a greater extent, the deterioration relates to the psychological and some characteristics of the somatic component of the quality of life. Thus, anxiety is associated with a deterioration in indicators on such a somatic scale as pain intensity. This may be due to the fact that patients with anxiety are often diagnosed with conditions associated with pain, such as chronic tension headache, nonspecific back pain, and a number of others. As an example, let's cite the results of a large-scale multinational survey, which also included Ukraine. According to the data obtained in our country, chronic pain has been noted in 19 patients over the past 12 months..7% of patients with anxiety or depression (Tsang A. et al., 2008). Thus, every 5th patient with an anxiety disorder also needs therapy aimed at eliminating pain.

This may be due to the fact that patients with anxiety are often diagnosed with conditions associated with pain, such as chronic tension headache, nonspecific back pain, and a number of others. As an example, let's cite the results of a large-scale multinational survey, which also included Ukraine. According to the data obtained in our country, chronic pain has been noted in 19 patients over the past 12 months..7% of patients with anxiety or depression (Tsang A. et al., 2008). Thus, every 5th patient with an anxiety disorder also needs therapy aimed at eliminating pain.

Evidence-based therapy

A rational approach to patient care includes both an individualized approach, taking into account the characteristics of each individual case, and reliance on the available evidence base, including clinical guidelines, meta-analyses and the results of recent randomized controlled clinical trials.

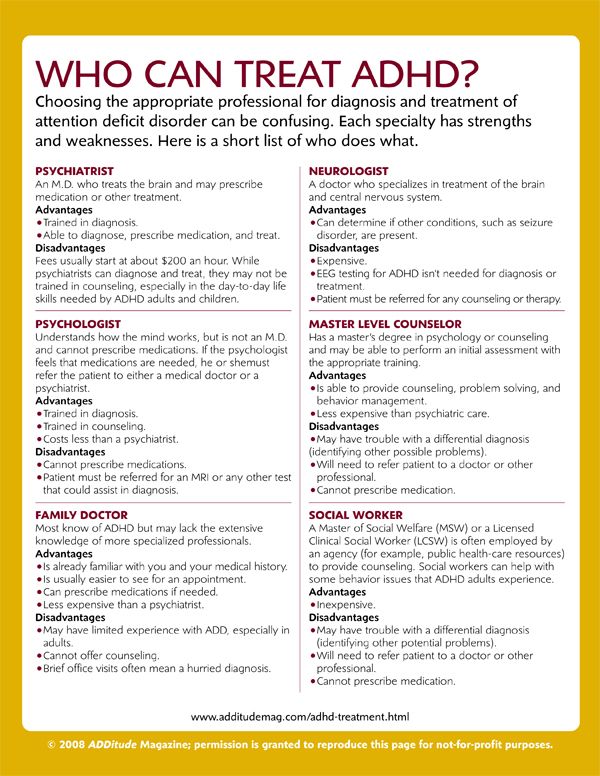

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), UK, is one of the well-known and leading providers of evidence-based clinical guidelines. In the latest guidelines on the quality standard of care for anxiety, a team of leading experts note that benzodiazepines and antipsychotics should be avoided in routine practice in patients with anxiety disorders (NICE, 2014). These recommendations are explained by the fact that taking the former is associated with the development of tolerance and dependence, and the latter with a relatively high risk of side effects. The authors recommend taking this into account, and if prescribed, then a short course in cases of exacerbation of symptoms, when other methods of treatment do not demonstrate sufficient effectiveness. Thus, antidepressants and/or cognitive-behavioral therapy are recommended as first-line therapy. For the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, in particular generalized anxiety disorder, NICE recommends selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and pregabalin. The authors of the guidelines note that one should also be aware of the possible withdrawal syndrome when using SSRIs and SNRIs, especially paroxetine and venlafaxine.

In the latest guidelines on the quality standard of care for anxiety, a team of leading experts note that benzodiazepines and antipsychotics should be avoided in routine practice in patients with anxiety disorders (NICE, 2014). These recommendations are explained by the fact that taking the former is associated with the development of tolerance and dependence, and the latter with a relatively high risk of side effects. The authors recommend taking this into account, and if prescribed, then a short course in cases of exacerbation of symptoms, when other methods of treatment do not demonstrate sufficient effectiveness. Thus, antidepressants and/or cognitive-behavioral therapy are recommended as first-line therapy. For the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, in particular generalized anxiety disorder, NICE recommends selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and pregabalin. The authors of the guidelines note that one should also be aware of the possible withdrawal syndrome when using SSRIs and SNRIs, especially paroxetine and venlafaxine.

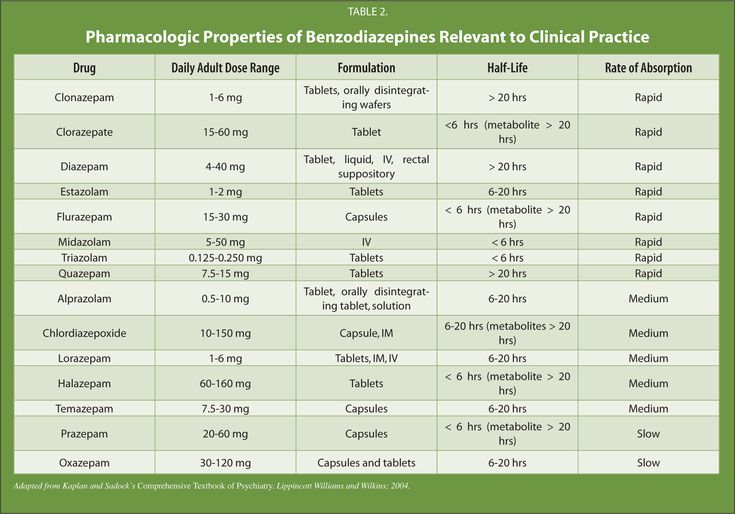

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the American Psychiatric Association (APA) are other well-known organizations that compile guidelines for the treatment of mental disorders and offer the same psychological and pharmacological treatments. We are talking, in particular, about the guidelines for the diagnosis and management of generalized anxiety and panic disorder (AAFP, 2015) and the APA clinical guidelines (2009) only for panic disorder, which practically duplicate the above, however, the regimens for prescribing drugs and psychological methods of treatment are prescribed in more detail. The list of recommended drugs is presented in the table.

Table AAFP recommended drugs for first and second line therapy

for generalized and panic disorder

| Drug | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| SSRI | |

| Escitalopram | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Fluvoxamine | Panic disorder |

| Fluoxetine | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Paroxetine | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Sertraline | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| SNRI | |

| Duloxetine | Generalized anxiety disorder |

| Venlafaxine | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Azaperone | |

| Buspirone | Generalized anxiety disorder |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | |

| Amitriptyline | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Imipramine | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Nortriptyline | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder |

| Antiepileptic drugs | |

| Pregabalin | Generalized anxiety disorder |

| Antipsychotics | |

| Quetiapine | Generalized Anxiety Disorder |

In addition to the medical communities of Great Britain and the USA, we also note the World Federation of Biological Psychiatry, which brings together specialists from different countries. In 2012, based on a review of the evidence base, this organization also published clinical guidelines for the treatment of anxiety disorders. The authors separately identified for panic, generalized disorder and social anxiety drugs included in first-line therapy:

In 2012, based on a review of the evidence base, this organization also published clinical guidelines for the treatment of anxiety disorders. The authors separately identified for panic, generalized disorder and social anxiety drugs included in first-line therapy:

- for social anxiety: escitalopram, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine;

- for panic disorder: same drugs + citalopram and fluoxetine;

- for generalized disorder: escitalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine, quetiapine, and pregabalin.

Particular attention in this list should be given to pregabalin, which belongs to the group of antiepileptic drugs. It should be noted that for a long time in the medical and pharmacological communities there has been a discussion of changing the existing approach to the classification of psychotropic drugs. Often the name of a group of drugs, such as antidepressants, antipsychotics (neuroleptics), or anticonvulsants (antiepileptic drugs), does not correspond to the diagnosis for which they are prescribed. So, antidepressants can be prescribed for anxiety, bulimia; antipsychotics - for anxiety, depression; anticonvulsants - for the same anxiety or bipolar affective disorder. Assigning a prescribed drug to any of these groups often confuses patients, which can be a cause for additional concern or reduced compliance. Discussion of the transition from the old classification model based on symptoms to the new one was one of the main topics of one of the largest annual world conferences on psychiatry and psychopharmacology "ECNP Congress" in 2014, 2015 and 2016, and it is possible that in the near future this new model will be implemented.

So, antidepressants can be prescribed for anxiety, bulimia; antipsychotics - for anxiety, depression; anticonvulsants - for the same anxiety or bipolar affective disorder. Assigning a prescribed drug to any of these groups often confuses patients, which can be a cause for additional concern or reduced compliance. Discussion of the transition from the old classification model based on symptoms to the new one was one of the main topics of one of the largest annual world conferences on psychiatry and psychopharmacology "ECNP Congress" in 2014, 2015 and 2016, and it is possible that in the near future this new model will be implemented.

Pregabalin differs in its chemical structure and mechanism of action from SSRIs and SNRIs, while remaining highly effective in generalized anxiety disorder, as evidenced by its inclusion as first-line therapy in various management guidelines for these patients. Pregabalin is a γ-aminobutyric acid derivative and was originally used and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of epilepsy and various types of chronic pain syndrome, including diabetic peripheral neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and fibromyalgia. Later evidence began to emerge for its effectiveness in anxiety disorders, especially generalized anxiety disorder and, to a lesser extent, social phobia.

Later evidence began to emerge for its effectiveness in anxiety disorders, especially generalized anxiety disorder and, to a lesser extent, social phobia.

Recently, this drug has increasingly become the subject of study specifically in the context of anxiety treatment as an alternative to SSRIs. The problem of the widespread use of the latter is mainly due to the relatively slow onset of action, the risk of withdrawal syndrome and the lack of a significant effect in relation to such often comorbid conditions as chronic pain syndrome of various origins. In addition, in about ⅓ of patients, the use of SSRIs and SNRIs does not lead to the desired effect and there is a need to look for another therapy with a different mechanism of action.

This was reflected in a systematic review of scientific studies conducted by the staff of the Villa San Benedetto Menni clinics in Rome, Maastricht University and the University of Miami. Summarizing the available evidence base for all drugs used in anxiety disorders, the researchers concluded that pregabalin is highly effective in generalized anxiety disorder. At the same time, as the authors note, the drug showed a low risk of adverse effects with long-term use and did not have a negative effect on cognitive or psychomotor functioning (Perna G. et al., 2016).

At the same time, as the authors note, the drug showed a low risk of adverse effects with long-term use and did not have a negative effect on cognitive or psychomotor functioning (Perna G. et al., 2016).

Also published this year are the results of an analysis of several randomized clinical trials that evaluated the effectiveness of pregabalin in the context of pain reduction and improvement in various areas of functioning. The authors note that taking pregabalin led to a significant reduction in pain, improved sleep quality and physical functioning. The analysis also assessed symptoms of anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). On the one hand, no significant differences were found with the control group (placebo), on the other hand, the study sample consisted of individuals with a low initial level of anxiety and depression, which did not reach the level of clinical significance (6 points each on the HADS anxiety and depression subscales at the threshold level ≥8 points and clinically significant ≥11 points) (Sadosky A. et al., 2016).

et al., 2016).

The problem of anxiety is also relevant for patients undergoing surgical treatment. This disorder often accompanies these patients both in the pre- and postoperative period. In addition, anxiety about the upcoming operation and pain has a negative effect on surgery and anesthesia. A new clinical trial conducted in 2016 demonstrated the effectiveness of pregabalin adjunctive therapy for bone surgery. In this study, patients of the experimental group were premedicated with pregabalin in different dosages before blockade of peripheral nerves. The control group did not receive any additional therapy. According to the results, the use of pregabalin significantly contributed to the maintenance of hemodynamic parameters during the intervention at a normal level and greater patient satisfaction with the quality of anesthesia. When using pregabalin at a dose of 150 and 300 mg, a significantly shorter duration of surgical intervention was also noted compared with the control (76. 5; 68.0 and 83.3 minutes, respectively).

5; 68.0 and 83.3 minutes, respectively).

Conclusions

Anxiety disorders are a common problem of our time, one of the main characteristics of which is a high comorbidity with both somatic and other mental disorders. The gradual discovery of new drugs and the study of additional properties of already long-term use has replaced benzodiazepines from the first-line therapy recommended in current guidelines for patients with anxiety disorders. Highly effective drugs are not limited to the SSRI and SNRI group; Today, there are other effective medicines classified as anticonvulsants and atypical antipsychotics. In particular, the study of the additional properties of pregabalin has demonstrated its high efficacy in generalized anxiety disorder, which is reflected in the most significant clinical guidelines and recommendations of the European Medical Agency. Experts conclude that pregabalin can be used as a first-line therapy for this disorder, and it may also be the best pharmacological alternative to SSRIs when they are ineffective or poorly tolerated.