Negative symptoms of schizophrenia flat affect

Flat Affect in Schizophrenia, Depression, Autism & More

Written by Alyson Powell Key

In this Article

- Schizophrenia

- Depression

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Your affect is the outward expression of your emotional state. If you’re happy or upset, people usually can see it on your face and hear it in your voice. But sometimes your emotions and how you express them don’t match up. You may be elated or depressed, but others can’t tell.

This is called a flat affect. People who have it don’t show the usual signs of emotion like smiling, frowning, or raising their voice. They seem uncaring and unresponsive.

Flat affect can be brought on by different conditions.

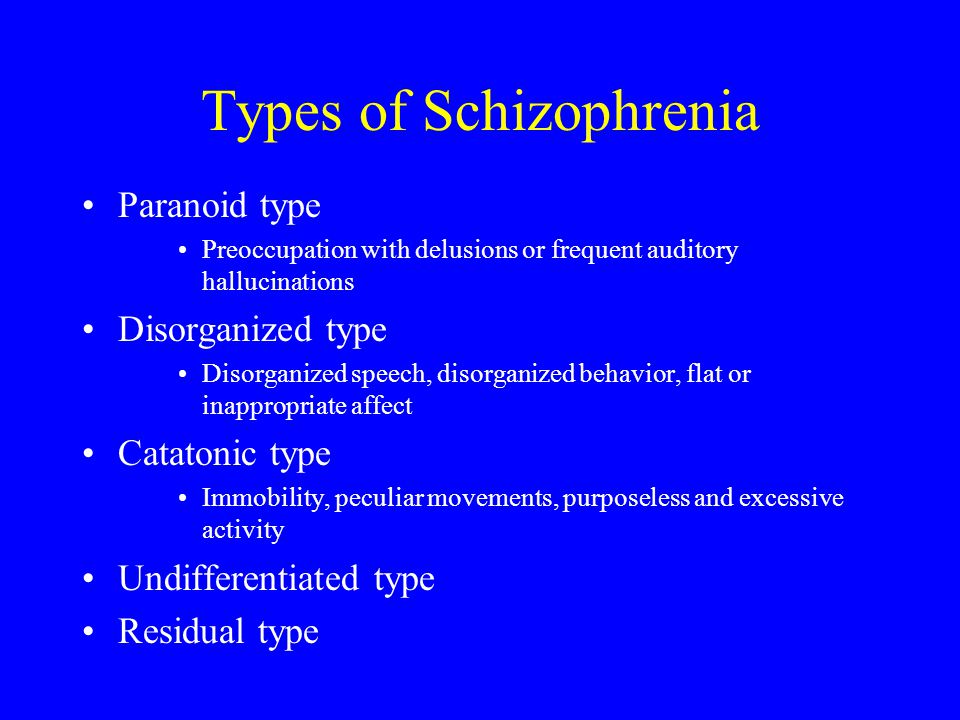

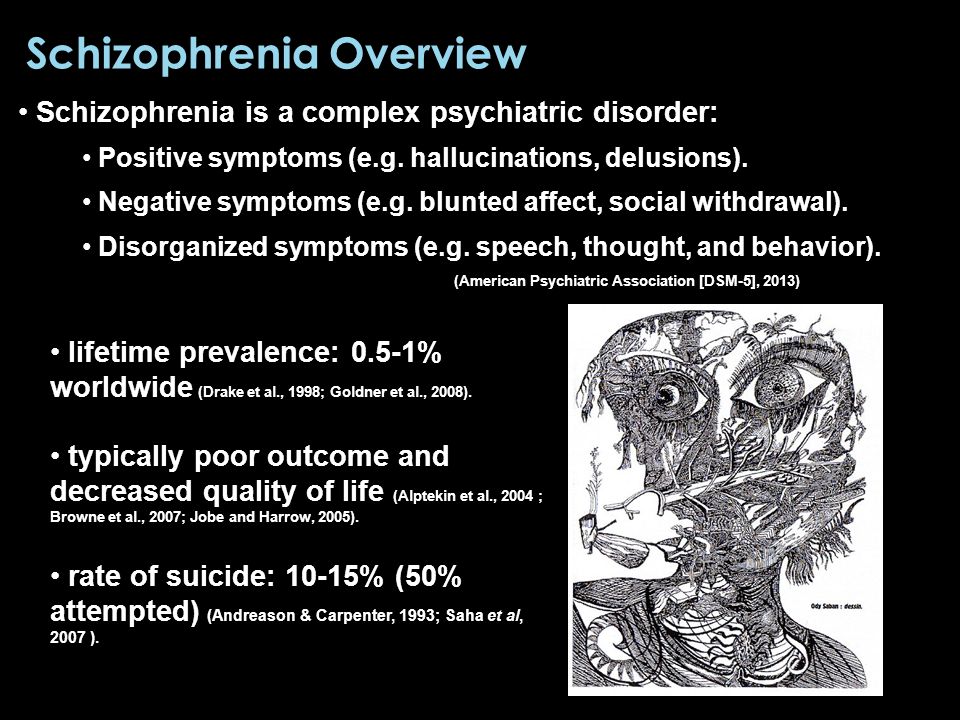

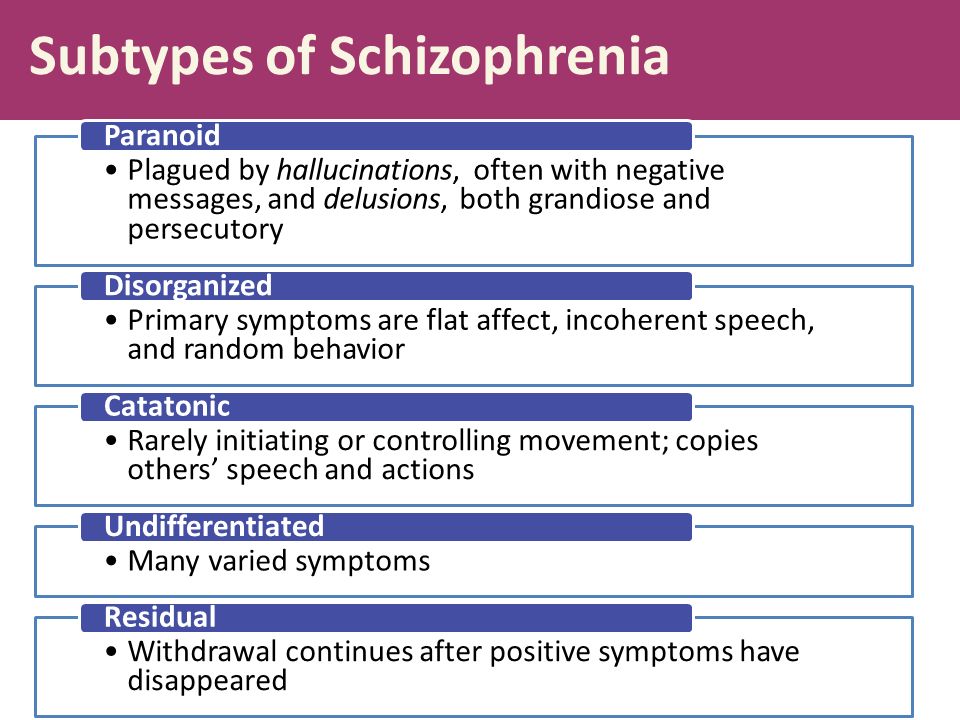

Schizophrenia

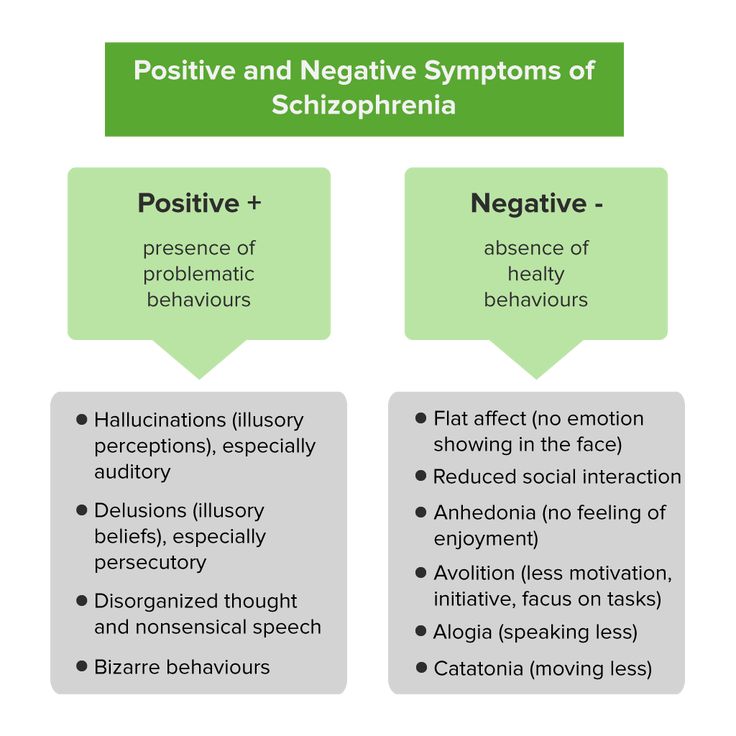

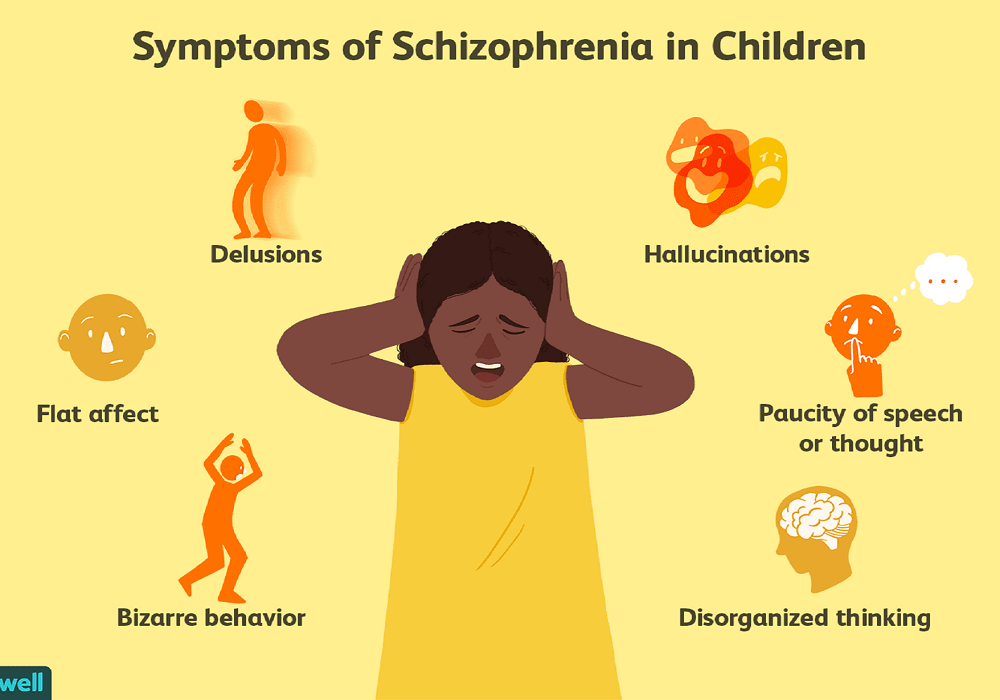

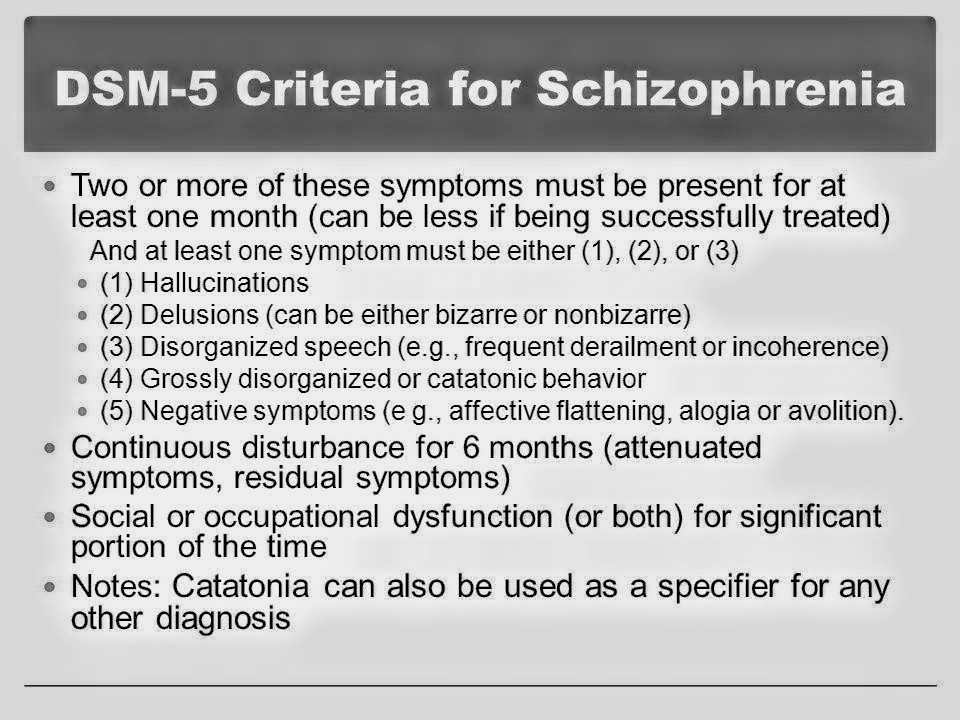

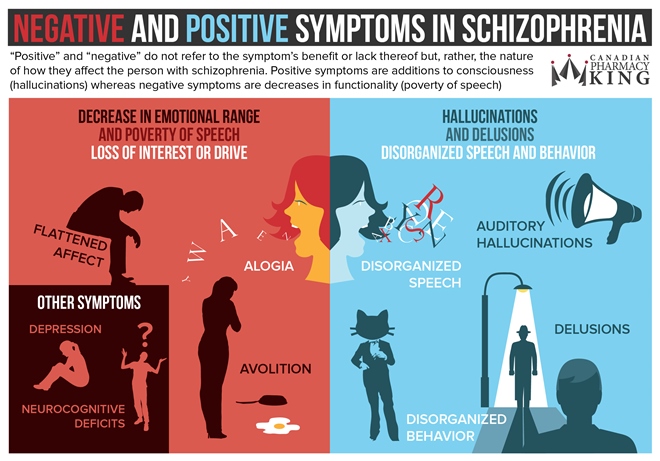

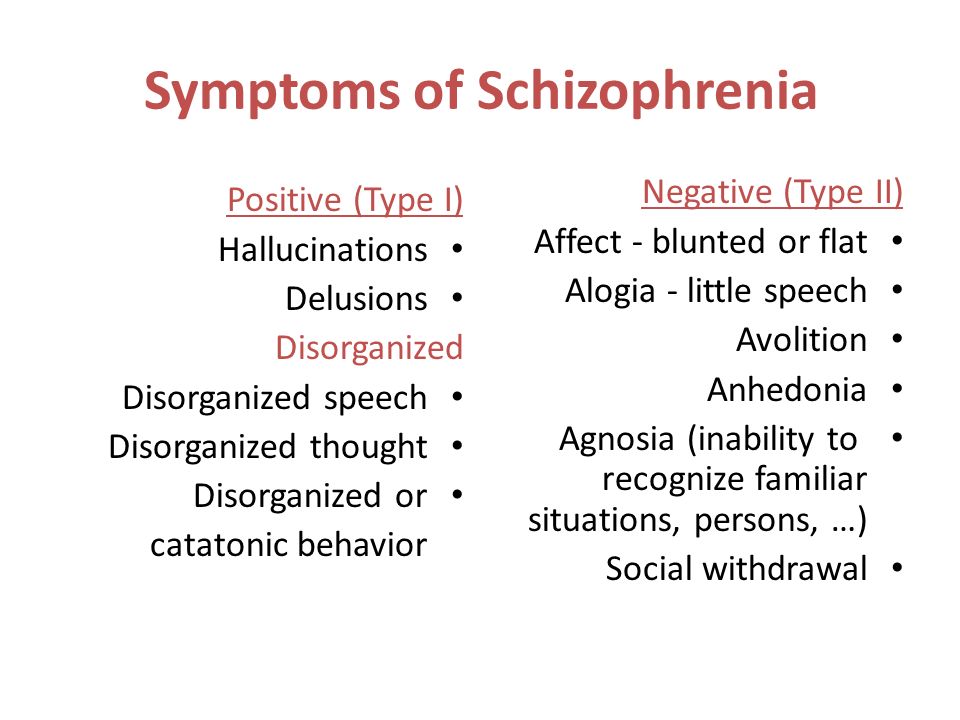

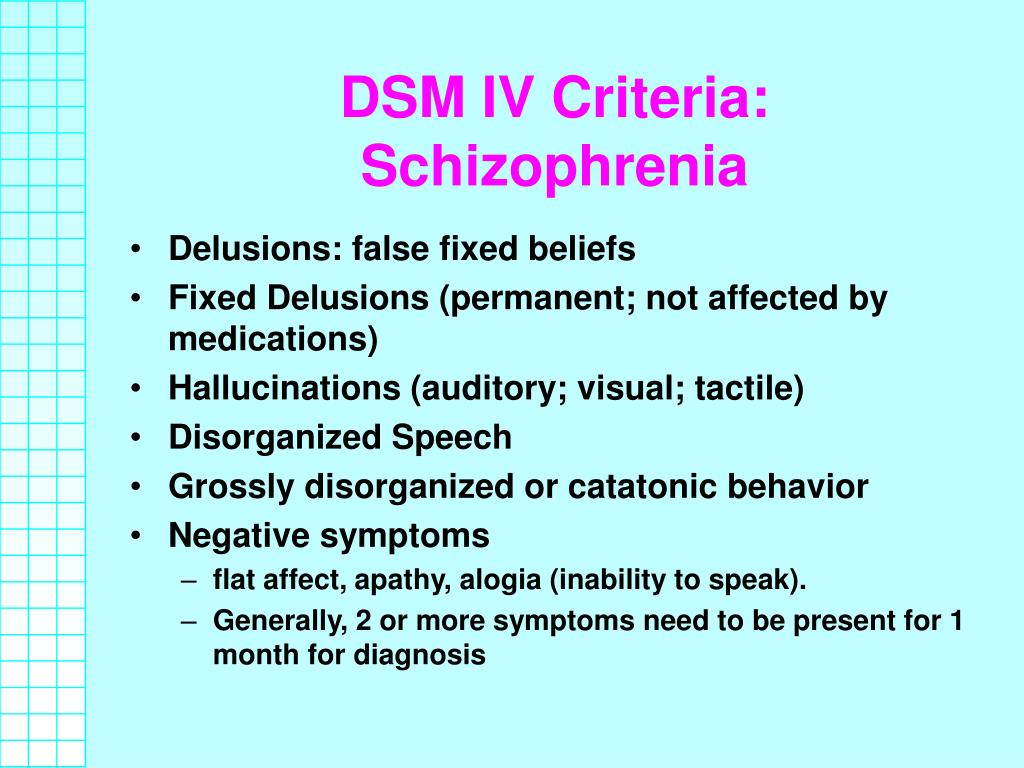

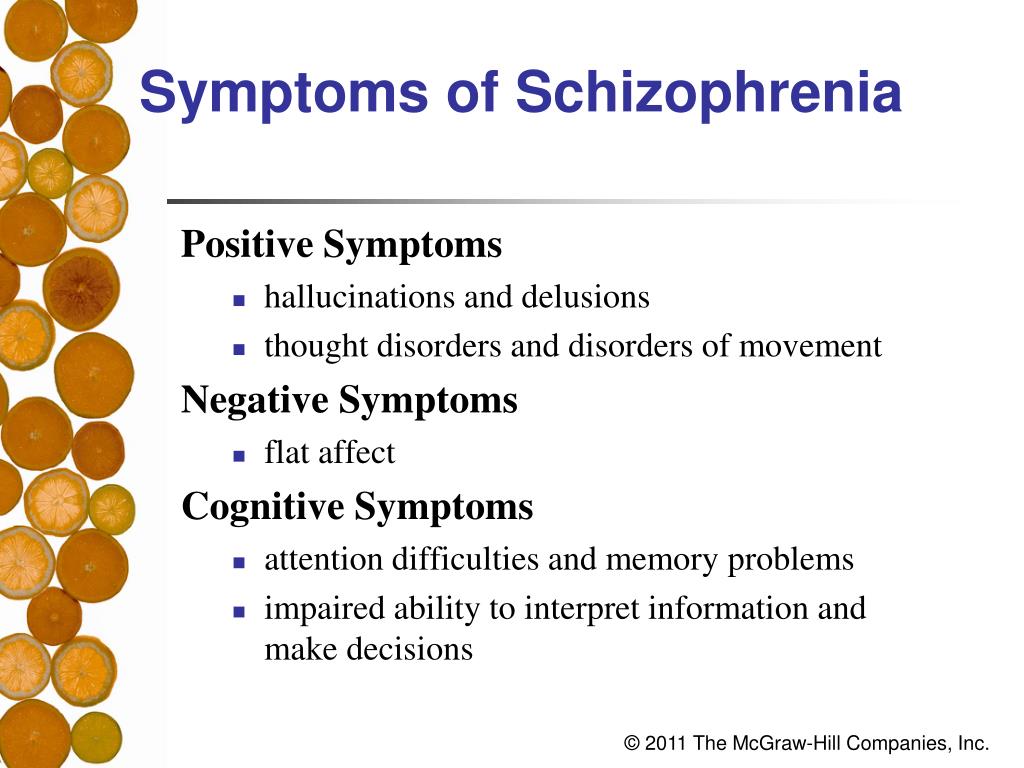

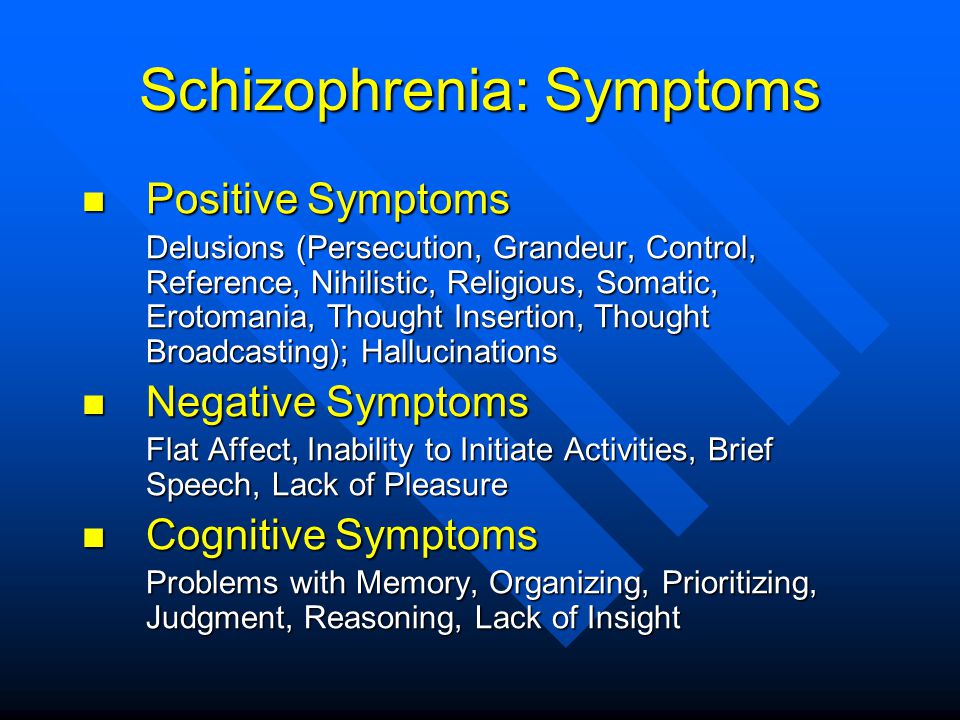

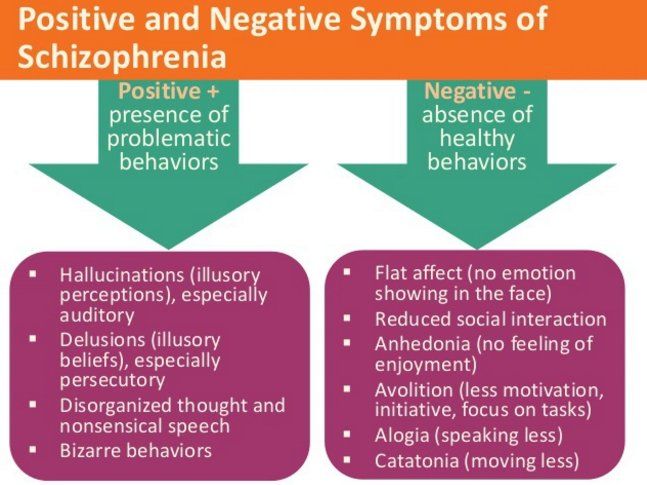

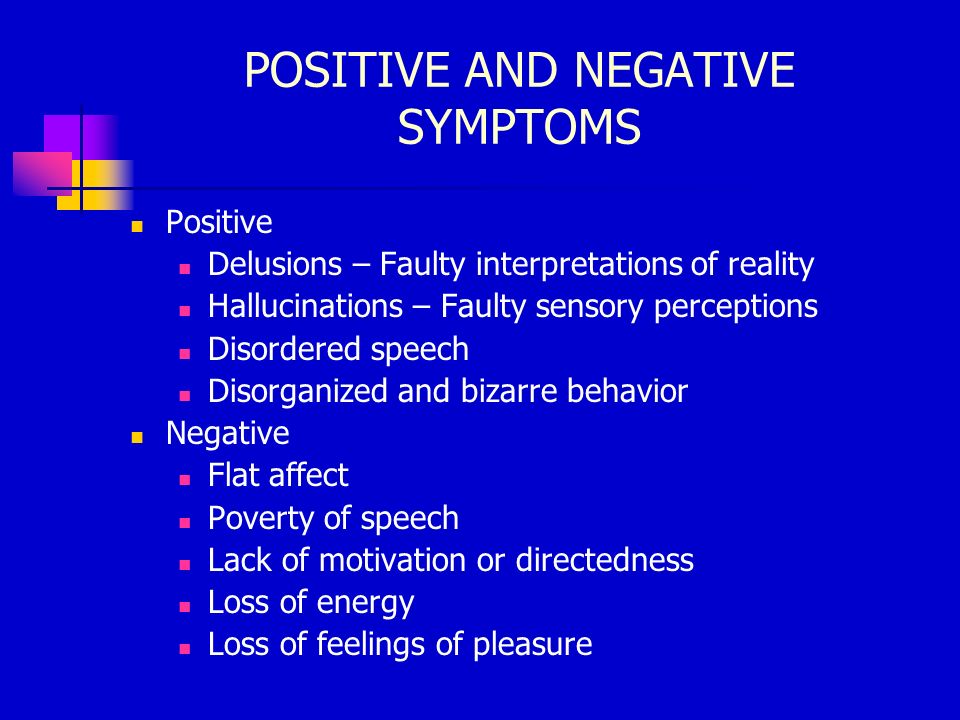

This is a serious, long-term mental illness. Some symptoms include:

- Believing things that aren’t real (delusions)

- Seeing or hearing things that don’t exist (hallucinations)

- Disorganized thinking or speech

- Sudden agitation, confusion, and other unusual behaviors

A flat affect can be a negative symptom of schizophrenia, meaning that your emotional expressions don’t show. You may speak in a dull, flat voice and your face may not change. You also may have trouble understanding emotions in other people. You might confuse happy and sad, or misjudge just how happy or sad the other person might be.

Schizophrenia is a lifelong illness. Even if your symptoms have gone away, you’ll need to stay on medication and get therapy. If your symptoms are severe, you may need to go to the hospital for your or other people’s safety.

Social skills training can help change a flat affect. This is when you work with a therapist or other mental health expert to learn how to communicate, interact with others, and manage everyday activities.

Depression

A flat effect can be one of the symptoms of this mood disorder. Researchers have used movie clips to study flat affect and depression. In one small study, they found that people who are depressed reacted less to positive scenes than people with schizophrenia did. Depressed people also reacted slightly more to negative clips.

Experts don’t exactly know why depression leads to a flattened affect. They think it may be linked to things such as a problem with your brain chemistry, your genes, and physical changes to your brain.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

This brain damage can happen after a car crash, a fall, or any other injury that causes a hard hit to the head.

The impact bounces your brain back and forth inside your skull. The trauma causes bruising and bleeding and tears the nerve fibers.

TBI can hurt a part of your brain called the frontal lobe. That’s where emotional expressions start. A damaged frontal lobe may cost you your ability to recognize or feel different emotions. The result is a flat affect. You also may miss cues in other people’s body language. A brain injury can even change your personality.

TBI can range from mild to severe. Your symptoms may go away after a few months or they may last for the rest of your life.

Your doctor will recommend a combination of treatments. A speech therapist or neuropsychologist can help you manage your flat affect and improve your relationships with family and friends.

A speech therapist or neuropsychologist can help you manage your flat affect and improve your relationships with family and friends.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Scientists know that autism and related disorders stem partly from genetics as well as differences in the brain.

People with ASD interact, behave, and communicate in unusual ways. A flat affect is one of them. Your face often may appear blank. Your voice may not change tone or may sound robot-like. People with ASD also have a hard time reading other people’s voices and body language.

It can be difficult to diagnose conditions like anxiety or depression in people with ASD because they may not give many outward signs. That’s why it’s important for caregivers and doctors to check for changes in sleep, appetite, and overall mood.

There’s no cure for ASD. But medication can help with energy level, focus, depression, and seizures. Working with a therapist can help you better relate to other people.

Flat Affect in Schizophrenia: Relation to Emotion Processing and Neurocognitive Measures

1. Bleuler E. In: Dementia Praecox. Zinkin J, translator. New York, NY: International Universities Press; 1950. [Google Scholar]

2. Kraepelin E. In: Dementia Praecox. Barclay RM, translator. Edinburgh: Scotland: Livingstone; 1919. [Google Scholar]

3. Carpenter WT., Jr Clinical constructs and therapeutic discovery. Schizophr Res. 2004;72:69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Gallacher F, Heimberg C, Cannon TD, Gur RC. Phenomenology and functioning in first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:449–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Goldstein JM, Seidman LJ, Goodman JM, et al. Are there sex differences in neuropsychological functions among patients with schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1358–1364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Gur RE, Petty RG, Turetsky BI, Gur RC. Schizophrenia throughout life: sex differences in severity and profile of symptoms. Schizophr Res. 1996;2:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schizophr Res. 1996;2:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Gallacher FV, Heimberg C, Gur RC. Gender differences in the clinical expression of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1992;7:225–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Krause R, Steimer E, Sanger-Alt C, Wagner G. Facial expressions of schizophrenic patients and their interaction partners. Psychiatry. 1989;52:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Berenbaum H, Oltmanns TF. Emotional experience and expression in schizophrenia and depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:37–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Kring AM, Kerr S, Smith DA, Neale JM. Flat affect in schizophrenia does not reflect diminished subjective experience of emotion. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;104:507–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Dworkin RH. Affective deficits and social deficits in schizophrenia: what's what? Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Archer J, Hay DC, Young AW. Face processing in psychiatric conditions. Br J Clin Psychol. 1992;31:45–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Br J Clin Psychol. 1992;31:45–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Bediou B, Franck N, Saoud M, et al. Effects of emotion and identity on facial affect processing in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2005;133:149–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Cutting J. Judgment of emotional expression in schizophrenics. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;139:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Feinberg TE, Rifkin A, Schaffer C, Walker E. Facial discrimination and emotional recognition in schizophrenia and affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:276–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Heimberg C, Gur RE, Erwin RJ, Shtasel DL, Gur RC. Facial emotion discrimination: III. behavioral findings in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1992;42:253–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Kerr SL, Neale JM. Emotion perception in schizophrenia: specific deficit or further evidence of generalized poor performance? J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102:312–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Kohler CG, Bilker W, Hagendoorn M, Gur RE, Gur RC. Emotion recognition deficit in schizophrenia: association with symptomatology and cognition. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:127–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Emotion recognition deficit in schizophrenia: association with symptomatology and cognition. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:127–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Mandal MK, Pandey R, Prasad AB. Facial expressions of emotions and schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:399–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Sachs G, Steger-Wuchse D, Kryspin-Exner I, Gur RC, Katschnig H. Facial recognition deficits and cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;68:27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Shaw RJ, Dong M, Lim KO, Faustman WO, Pouget ER, Alpert M. The relationship between affect expression and affect recognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1999;37:245–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Walker EF, McGuire M, Bettes B. Recognition and identification of facial stimuli by schizophrenics and patients with affective disorders. Br J Clin Psychol. 1984;23:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Kring AM, Neale JM. Do schizophrenia patients show a disjunctive relationship among expressive, experiential, and psychophysiological components of emotion? J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:249–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1996;105:249–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Aghevli MA, Blanchard JJ, Horan WP. The expression and experience of emotion in schizophrenia: a study of social interactions. Psychiatry Res. 2003;119:261–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Kohler CG, Gur RC, Gur RE. Emotional processes in schizophrenia: a focus on affective states. In: Borod JC, editor. The Neuropsychology of Emotion. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

26. Sweet LH, Primeau M, Fichtner CG, Lutz G. Dissociation of affect recognition and mood state from blunting in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1998;81:301–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Lewis SF, Garver DL. Treatment and diagnostic subtype in facial affect recognition in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1995;29:5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Cramer P, Weegmann M, O'Neil M. Schizophrenia and the perception of emotions: how accurately do schizophrenics judge the emotional states of others? Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155:225–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1989;155:225–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Blanchard JJ, Kring M, Neale JM. Flat affect in schizophrenia: a test of neuropsychological models. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:311–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Blanchard JJ, Neale JM. The neuropsychological signature of schizophrenia: generalized or differential deficit? Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:40–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Erwin RJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Skolnick BE, Mawhinney-Hee M, Smailis J. Facial emotion discrimination: I. task construction and behavioral findings in normals. Psychiatry Res. 1992;42:231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Schneider F, Gur RC, Gur RE, Muenz L. Standardized mood induction with happy and sad facial expressions. Psychiatry Res. 1994;51:19–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Kohler CG, Turner TH, Bilker WB, et al. Facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia: intensity effects and error pattern. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1768–1774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Kohler CG, Turner TH, Stolar NM, et al. Differences in facial expressions of four universal emotions. Psychiatry Res. 2004;128:235–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Differences in facial expressions of four universal emotions. Psychiatry Res. 2004;128:235–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Silver H, Shlomo N, Turner T, Gur RC. Perception of happy and sad facial expressions in chronic schizophrenia: evidence for two evaluative systems. Schizophr Res. 2002;55:171–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Schneider F, Gur RC, Gur RE, Shtasel DL. Neurobehavioral probes in relation to psychopathology. Schizophr Res. 1995;17:67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Meyer DE, Irwin DE, Osman AM, Kounios J. The dynamics of cognition and action: mental processes inferred from speed-accuracy decomposition. Psychol Rev. 1988;95:183–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Smith RW, Kounios J. Sudden insight: all-or-none processing revealed by speed-accuracy decomposition. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1996;22:1443–1462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Damasio AR. Emotion in the perspective of an integrated nervous system. Brain Res Rev. 1998;26:83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Rolls ET. Memory systems in the brain. Annu Rev Psychol. 2000;51:599–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Gur RE, Mozley PD, Resnick SM, et al. Relations among clinical scales in schizophrenia: overlap and subtypes. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:472–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. First M, Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV: Patient Version (SCID-P) New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department; 1996. [Google Scholar]

43. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

44. Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa; 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

46. Cannon-Spoor H, Potkin S, Wyatt R. Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1982;8:470–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Heinrichs D, Hanlon T, Carpenter WJ. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10:388–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT., Jr The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia: I. characteristics of outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972;27:739–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Mozley PD, et al. Volunteers for biomedical research: recruitment and screening of normal controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:1022–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP) New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department; 1995. [Google Scholar]

51. Chute DL, Westall RF. PowerLaboratory. Devon, Pa: MacLaboratory, Incorporated; 1997. [Google Scholar]

Chute DL, Westall RF. PowerLaboratory. Devon, Pa: MacLaboratory, Incorporated; 1997. [Google Scholar]

52. Gur RC, Ragland JD, Moberg PJ, et al. Computerized neurocognitive scanning: I. methodology and validation in healthy people. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:766–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Gur RC, Ragland JD, Moberg PJ, et al. Computerized neurocognitive scanning: II. the profile of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:777–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Kurtz MM, Ragland JD, Moberg PJ, Gur RC. The Penn Conditional Exclusion Test: a new measure of executive-function with alternate forms of repeat administration. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2004;19:191–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Glahn DC, Gur RC, Ragland JD, Censits DM, Gur RE. Reliability, performance characteristics, construct validity, and an initial clinical application of a Visual Object Learning Test (VOLT) Neuropsychology. 1997;11:602–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Benton AL, Varney NR, Hamsher K. Judgment of Line Orientation, Form V. Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Hospitals; 1975. [Google Scholar]

Benton AL, Varney NR, Hamsher K. Judgment of Line Orientation, Form V. Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Hospitals; 1975. [Google Scholar]

57. Siegel SJ, Irani F, Brensinger CM, et al. Prognostic variables at intake and long-term level of function in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Earnst KS, Kring AM, Kadar MA, Salem JE, Shepard DA, Loosen PT. Facial expression in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:556–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Kring AM, Kerr SL, Earnst KS. Schizophrenic patients show facial reactions to emotional facial expression. Psychophysiology. 1999;36:186–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Lang PJ. The varieties of emotional experience: a meditation on James-Lange theory. Psychol Rev. 1994;101:211–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Reber PJ, Squire LR. Encapsulation of implicit and explicit memory in sequence learning. J Cogn Neurosci. 1998;10:248–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Schacter DL, Norman KA, Koustaal W. The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory. Annu Rev Psychol. 1998;49:289–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schacter DL, Norman KA, Koustaal W. The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory. Annu Rev Psychol. 1998;49:289–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Gur RE, McGrath C, Chan RM, et al. An fMRI study of facial emotion processing in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1992–1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Gur RC, Sara R, Hagendoorn M, et al. A method for obtaining 3-dimensional facial expressions and its standardization for use in neurocognitive studies. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;115:137–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Verma R, Davatzikos C, Loughead J, et al. Quantification of facial expressions using high-dimensional shape transformations. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;141:61–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Walker EF, Grimes KE, Davis DM, Smith AJ. Childhood precursors of schizophrenia: facial expressions of emotion. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1654–1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Mueser KT, Doonan R, Penn DL, et al. Emotion recognition and social competence in chronic schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Kee KS, Green MF, Mintz J, Brekke JS. Is emotion processing a predictor of functional outcome in schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:487–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Negative symptoms: detailed information

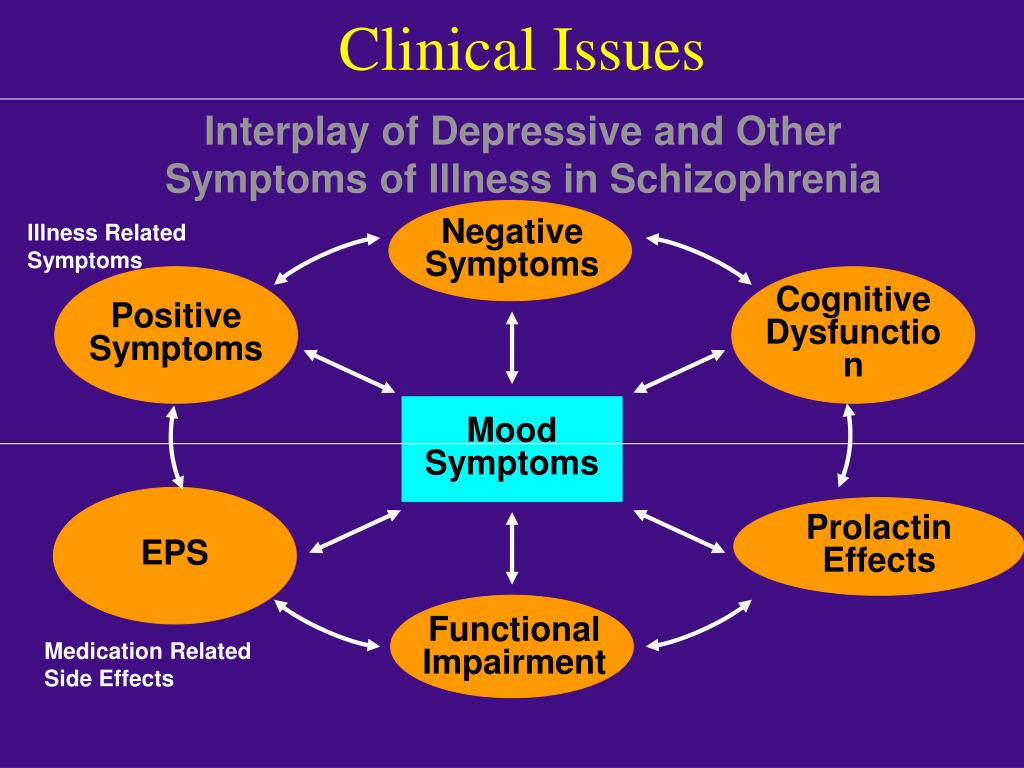

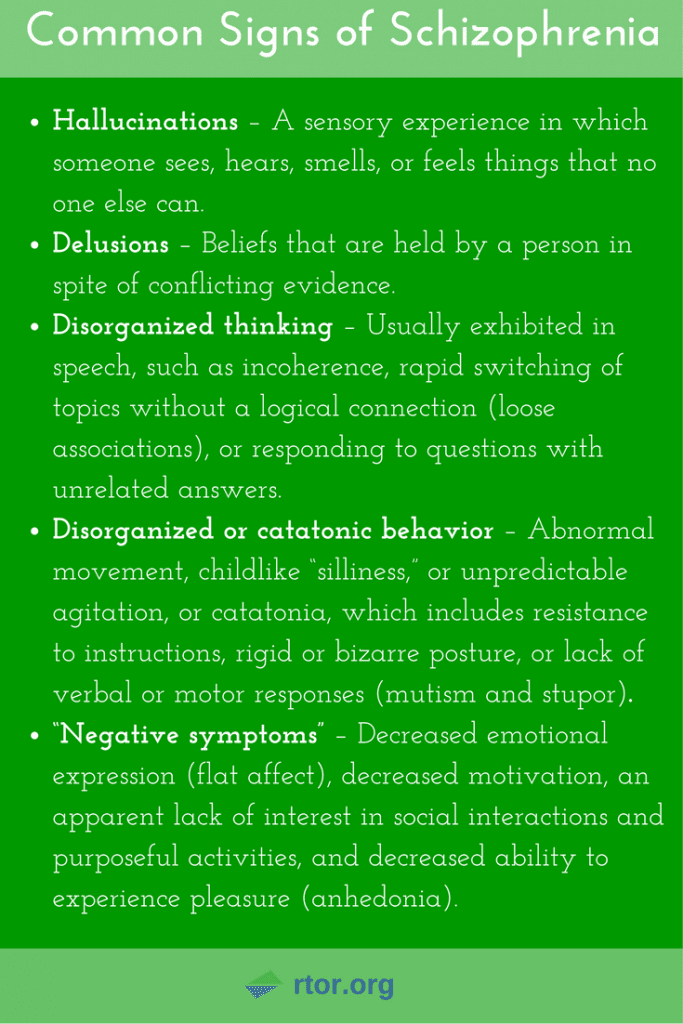

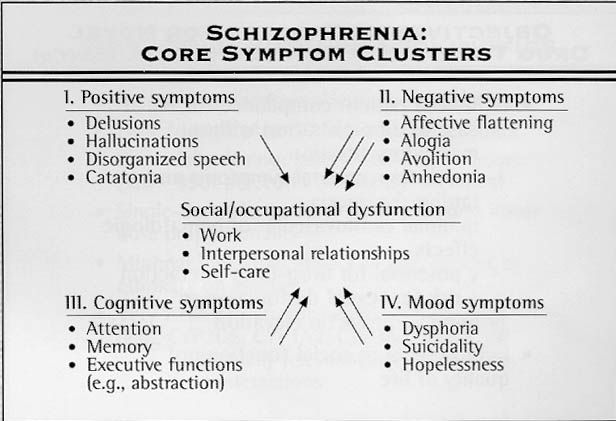

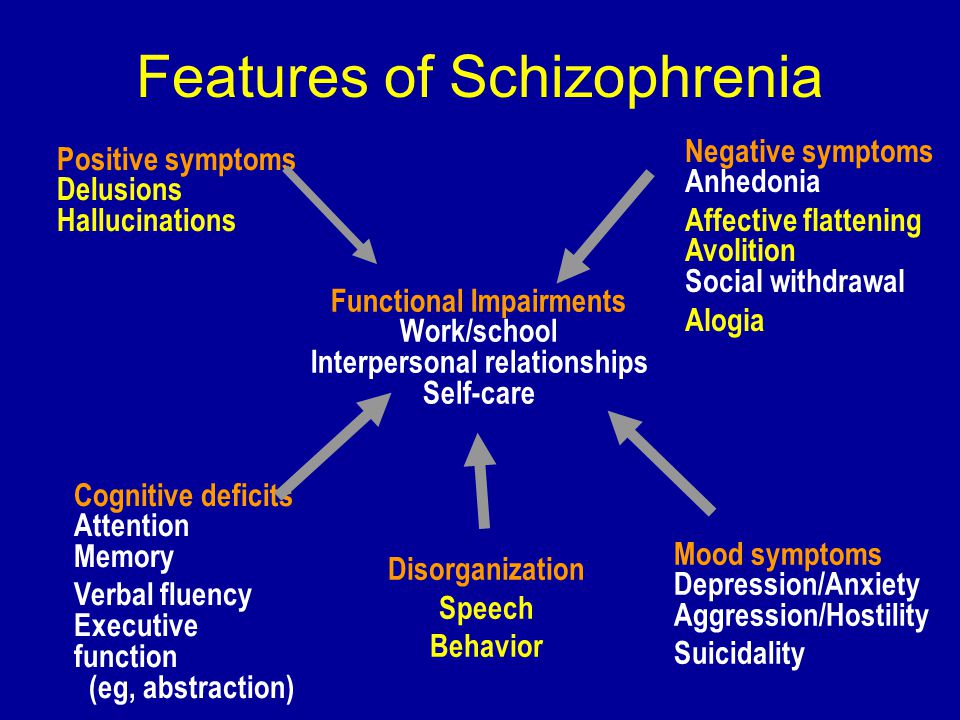

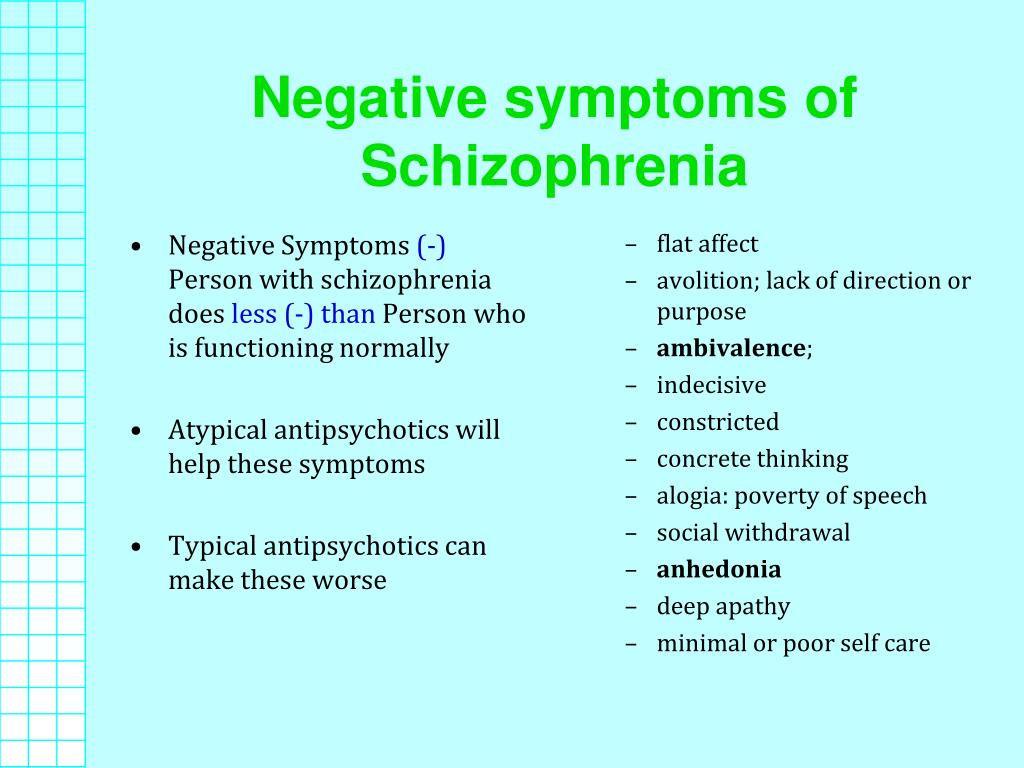

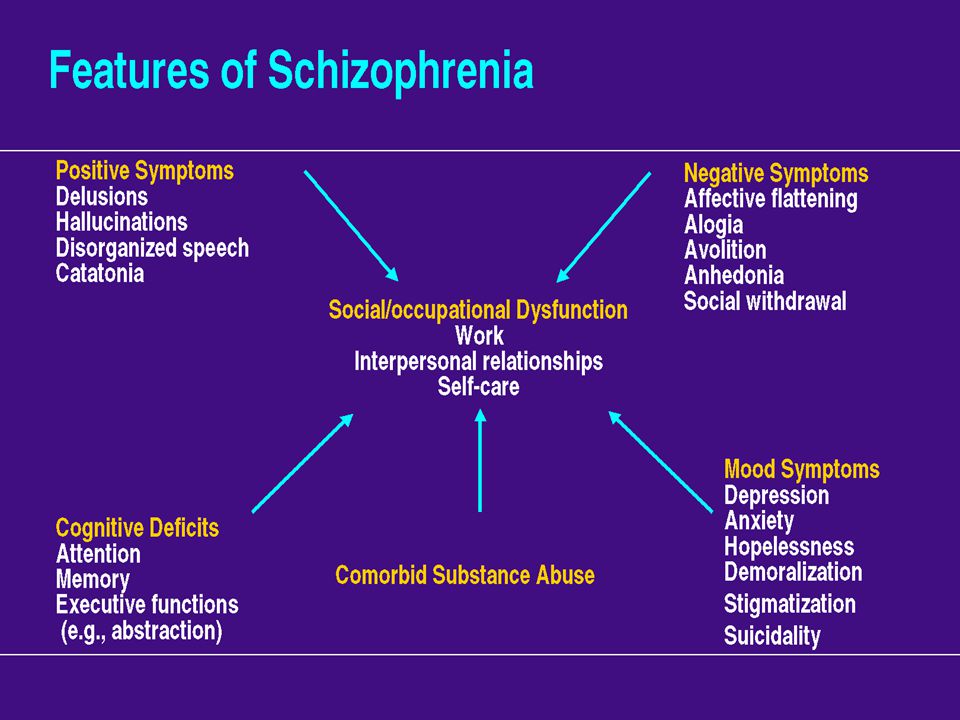

- Negative symptoms are the main symptom complex of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. It leads to social maladjustment, the prerequisites for the formation of which are a violation of the motivational, cognitive, emotional sphere.

- Although patients may appear sad, withdrawn, and immersed in anxiety, the negative symptoms of schizophrenia are not the same as symptoms of depression. On the contrary, they are symptoms that occur regardless of the presence or absence of depressive manifestations, positive symptoms, cognitive impairment and behavioral disorganization.

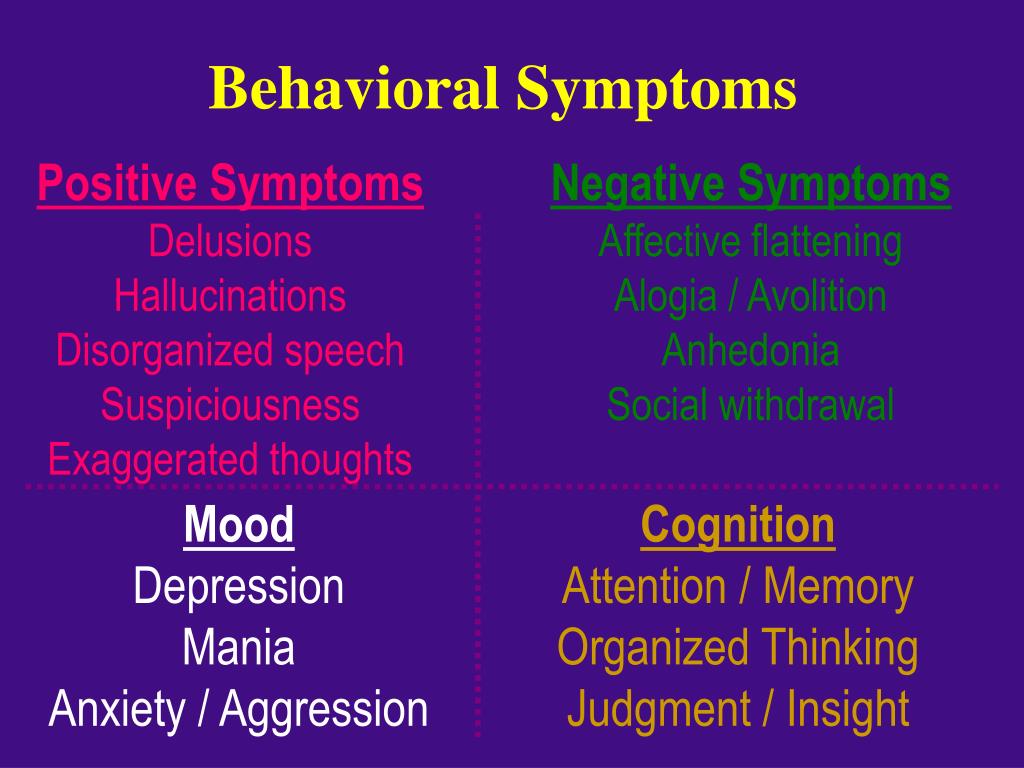

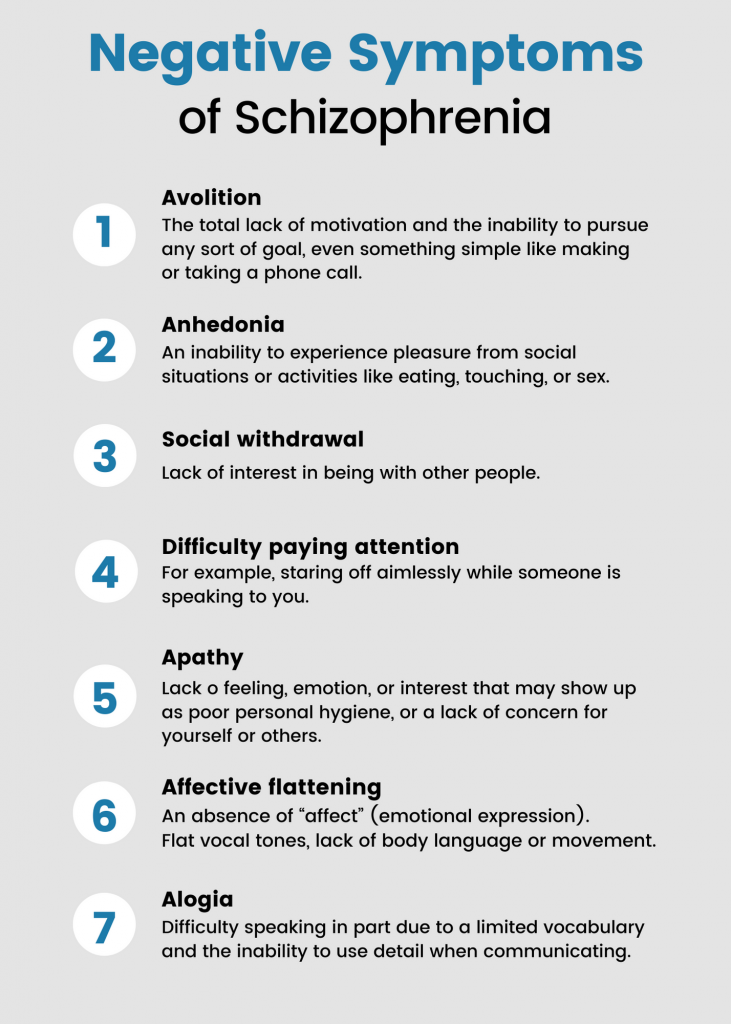

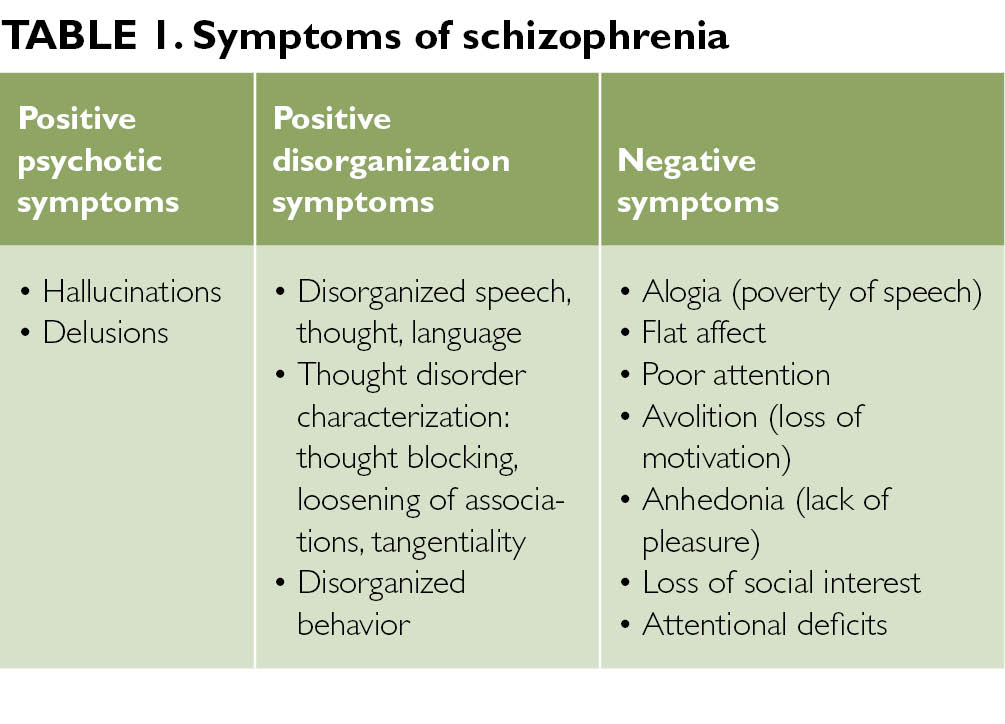

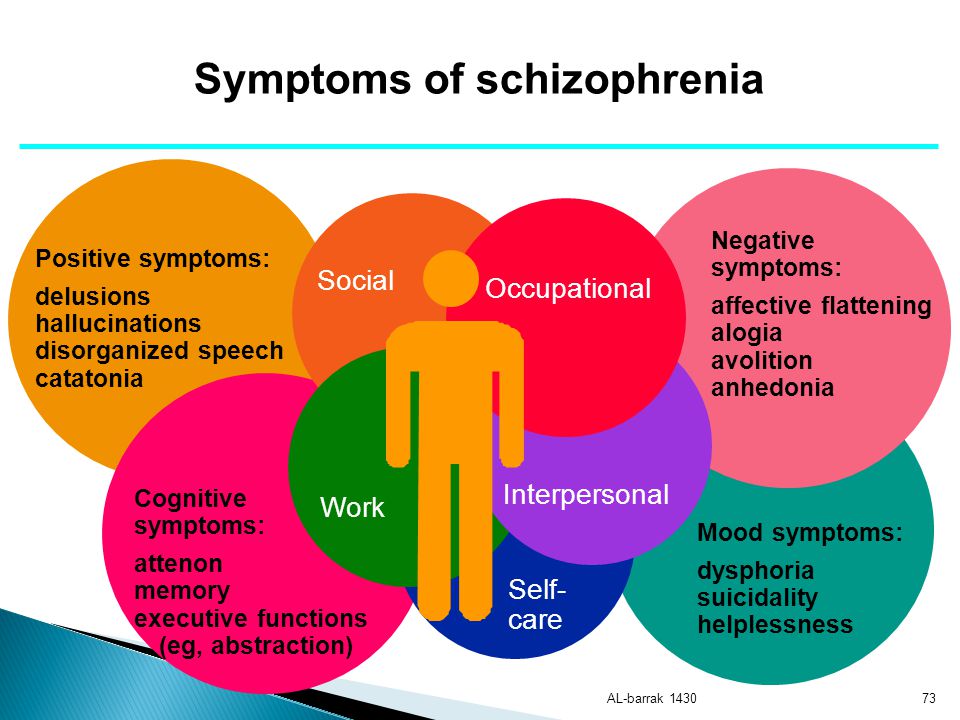

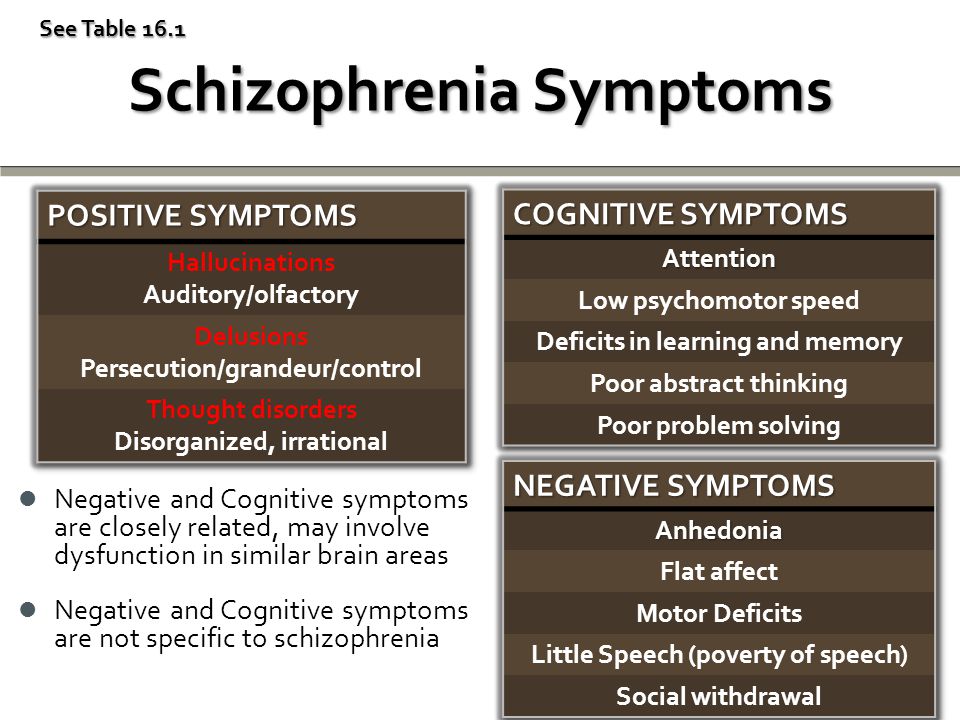

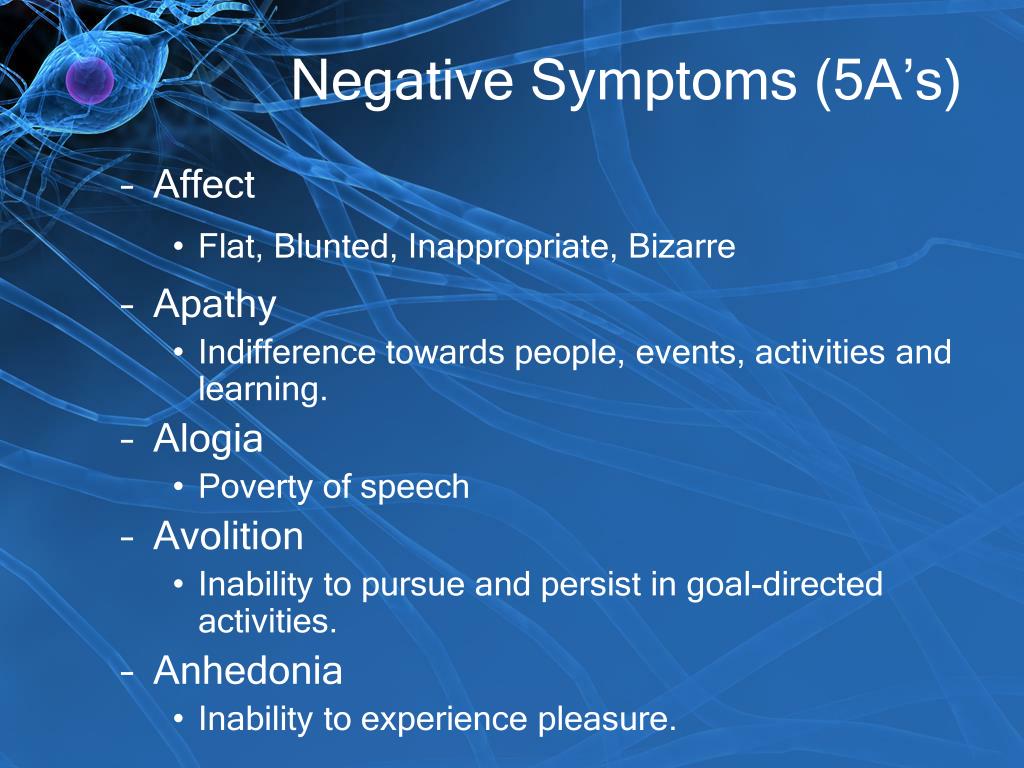

- Five conditions are considered to be the key manifestations of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia: flattened affect, alogia, anhedonia, asociality and abulia.

These conditions are grouped depending on the leading type of disorders: symptoms associated with a decrease in expression (blunted affect, alogia), symptoms caused by a violation of motivation and the inability to enjoy pleasure (anhedonia, asociality, abulia).

These conditions are grouped depending on the leading type of disorders: symptoms associated with a decrease in expression (blunted affect, alogia), symptoms caused by a violation of motivation and the inability to enjoy pleasure (anhedonia, asociality, abulia).

In this section

Main symptom complex of schizophrenia

Negative symptoms - symptoms of a violation of the patient's usual daily functioning. They arise against the background of changes in the motivational and emotional sphere, which leads to schizophrenia.

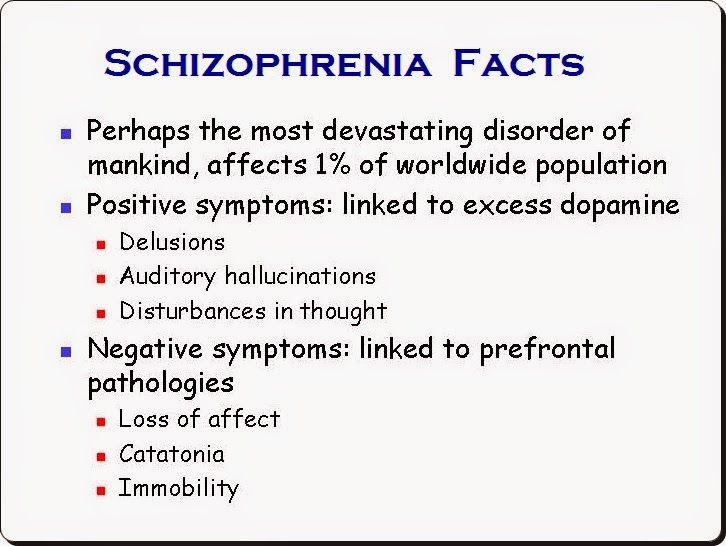

At the moment, there is no common understanding of the etiology and pathophysiology of the appearance of negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Research has also shown that negative symptoms of schizophrenia can occur independently of positive, cognitive symptoms, depression, or disorganization 1.2 .

Negative symptoms are associated with low motivation, flattening of affect, impaired social and interpersonal interaction 3 .

Negative symptoms are recognized as a key manifestation of schizophrenia. Eugen Bleuler (1857-1939) was the first to speak about them. In a 1950 edition of his work, the negative symptoms are described as:

“Indifference to everything—friends and relatives, work or pleasure, duties or rights, good or bad luck…

The face (of the patient) is inexpressive, the posture is stooped. An image of indifference…

the ability to work, to serve oneself is reduced…

Such people lose their desire to do something on their own initiative or at the direction of others” 4 .

It is important to note that negative symptoms can be difficult to recognize, especially if they are mild. But they should not be confused with sadness or just a bad mood 5.6 .

Five key negative symptoms of schizophrenia (5 "A")

Flattened affect alogia, anhedonia, asociality, abulia - five key negative symptoms of schizophrenia 7 .

The ability to express emotions

(noticeable to others)

Acted affect - This is a decrease in the expressiveness of verbal and non -verbal communications (monotony of speech, inexpressiveness of facial expressions and troops).

Studies of vocal expression showed that in patients with schizophrenia, compared with healthy volunteers, there was a violation of tonality, speed, volume, and modulation of speech. Changes were recorded both during spontaneous and arbitrary speech.

Non-verbal behavior of patients with schizophrenia is smoothed out, becomes inexpressive, not aimed at communication. These manifestations complicate the process of the patient's interaction with society, since it is expressive facial expressions, gestures, postures that are an important component of interpersonal communication 7 .

Alogia - poverty of speech, a decrease in the number of words used during a conversation, a violation of the spontaneity of speech.

Alogia revealed during clinical interview. Estimated spontaneity of speech, sentence structure. Patients are characterized by a violation of spontaneity, short answers, lack of need to independently reveal the topic of conversation.

A meta-analysis of studies showed that patients, unlike healthy people, speak with large pauses, build short sentences, their speech is not smooth.

At the same time, the scarcity of speech, the need to use a large number of words, use long sentences that do not carry a semantic load, does not belong to the concept of alogia 7 .

Reduced motivation and ability to enjoy (what the patient feels)

Asociality - lack of need for interpersonal contacts, communication.

The patient has no desire, no strength to initiate or maintain communication with others.

This state should be distinguished from the limitations of social interaction associated with positive symptoms: delusions, hallucinations. The patient may refuse to communicate because of a bad mood, fear of harming others, due to the appearance of suspicion, fears characteristic of a delusional episode.

The patient may refuse to communicate because of a bad mood, fear of harming others, due to the appearance of suspicion, fears characteristic of a delusional episode.

Also, the patient may be in forced social isolation, and simply not be able to communicate with people. This is not equivalent to asociality 7 .

Anhedonia , that is, a decrease in the ability to enjoy, experience positive emotions.

Traditionally regarded as a core feature of both depression and schizophrenia.

The anhedonia component can be divided into two components:

Reduced ability to experience pleasure during potentially pleasurable activities - consummatory anhedonia. In schizophrenia remains relatively unaffected;

Reduced ability to anticipate future pleasure - anticipatory anhedonia. It is characteristic of patients with schizophrenia and is considered a hallmark of negative symptoms.

Anticipatory anhedonia results in an inability to anticipate rewards and reduces the patient's motivation for hedonic experiences 7. 8 .

8 .

Studies have shown that schizophrenic patients with consummatory anhedonia do not differ from healthy controls in their ability to experience subjective responses to emotionally charged stimuli. With anticipatory anhedonia, the differences are pronounced.

The mechanisms underlying anhedonia can be explained as violations of the motivational component - no expectation of reward, positive reinforcement, no desire for action, and also considered from the point of view of cognitive dysfunction. When episodic memory impairments make it difficult to remember and recall hedonistic experiences 7 .

Abulia is an inability to purposeful activity. There is a decrease in involvement in work, study, hobbies, household chores. The ability to self-care is impaired.

There is no consensus on the degree of overlap between the terms abulia, decreased aspiration, lack of motivation, and apathy, and they are often considered interchangeable.

Abulia in schizophrenia is characterized by a weakening of interest in any activity: the patient does not initiate and does not support business activity. He has no such need as such. At the same time, the patient does not experience discomfort, feelings of guilt due to unfulfilled obligations.

A decrease in activity can also be a secondary manifestation associated with a depressed state (a general feeling of sadness, guilt, characteristic of abulia), due to the lack of opportunities for activity.

And yet, there is an opinion that a violation in the incentive-reward system is a key aspect of aboulia 7 .

In general, studies show that of the five negative symptoms of schizophrenia listed, patients most often show a lack of social motivation, followed by a decrease in expressiveness (flattened affect) and alogia 9-11 .

Two groups of negative symptom complexes

(factors within negative symptoms)

Factor analyzes of negative symptoms demonstrated that the structure of these symptoms is not one-dimensional. The number of identified factors ranged from 2 to 5.

The number of identified factors ranged from 2 to 5.

Usually, the division is based on how often certain combinations of symptoms occur in the clinical picture of the disease.

The most reproducible and stable structure includes two factors 12 :

A group of symptoms associated with a decrease in emotional expression (flattened affect, alogia).

A group of symptoms associated with a decrease in motivation for activity and inability to enjoy pleasure (anhedonia, asociality, abulia).

The co-occurrence of certain negative symptoms can be explained by: neurobiological pathologies and psychosocial causes (13).

For example, flattening of affect/alogia can be associated with a non-social, neuropsychological aspect (14). At the same time, aboulia/apathy is directly related to the social interaction of the patient (3).

Characteristics of negative symptoms

Negative symptoms can also be divided according to their appearance: primary, secondary; according to the degree of manifestation on: pronounced, predominant; by duration of exposure: persistent.

| Negative symptom definition | |

| Primary | Considered to be the main symptoms of schizophrenia that persist during the period of stabilization of the disease |

Primary negative symptoms of schizophrenia are considered the main symptoms of the disease, which persist even during the stabilization of the patient's condition. Their pathophysiology is specific to schizophrenia 15 .

In contrast to primary symptoms, secondary negative symptoms appear as a consequence of positive symptoms, as neurological side effects of drug therapy, as a response to negative environmental factors 16.17 .

Characteristics "severe" and "predominant" describe the degree of manifestation of negative symptoms in a particular patient.

Symptoms may be considered "severe" if the patient has more negative symptoms than positive symptoms.

Criteria:

1. Baseline score ≥4 on at least 3 items or ≥5 on at least 2 items on the PANSS Negative Symptom Subscale;

2. Score >3 on item 1 and item 6 on the PANSS Negative Symptom Subscale and at least one-third of items scoring >3 and no more than two items scoring >3 on the Positive Symptom Subscale) 18.19 .

Score >3 on item 1 and item 6 on the PANSS Negative Symptom Subscale and at least one-third of items scoring >3 and no more than two items scoring >3 on the Positive Symptom Subscale) 18.19 .

Persistent negative symptoms are defined by the PANSS as the presence of at least one moderate or severe negative symptom (not affected by depression or parkinsonism) at baseline and one year after treatment 20 . Presence of at least one negative symptom of moderate or severe severity for more than one year 20 .

For purposes of clinical trials, data is required for periods longer than 6 months 19 .

Sources:

- Kirkpatrick, B., Fenton, W. S., Carpenter, W. T. & Marder, S. R. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr. Bull . 32, 214–219 (2006).

- Wallwork, R. S., Fortgang, R., Hashimoto, R., Weinberger, D. R. & Dickinson, D. Searching for a consensus five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia.

Schizophr. Res . 137, 246–250 (2012).

Schizophr. Res . 137, 246–250 (2012). - Foussias, G., Agid, O., Fervaha, G. & Remington, G. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: Clinical features, relevance to real world functioning and specificity versus other CNS disorders. EUR. Neuropsychopharmacol . 24, 693–709 (2014).

- Bleuler, E. Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias (1950).

- National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH). Schizophrenia . (2017). Available at: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/schizophrenia-booklet/index.shtml.

- Fischer, B. A. & Buchanan, R. W. Schizophrenia: Clinical Manifestations, Course, Assessment and Diagnosis. UpToDate (2017). Available at: www.up-to-date/schizophrenia.

- Marder, S. R. & Galderisi, S. The current conceptualization of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. World Psychiatry 16, 14–24 (2017).

- Strauss, G. P., Waltz, J.

A. & Gold, J. M. A review of reward processing and motivational impairment in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull . 40, S107-116 (2014).

A. & Gold, J. M. A review of reward processing and motivational impairment in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull . 40, S107-116 (2014). - Lyne, J. et al. Prevalence of item level negative symptoms in first episode psychosis diagnoses. Schizophr. Res . 135, 128–133 (2012).

- Peralta, V. & Cuesta, M. J. Dimensional structure of psychotic symptoms: An item-level analysis of SAPS and SANS symptoms in psychotic disorders. Schizophr. Res . 38, 13–26 (1999).

- Selten, J. P., Wiersma, D. & Van den Bosch, R. J. Distress attributed to negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull . 26, 737–744 (2000).

- Fleischhacker, W. et al. The efficacy of cariprazine in negative symptoms of schizophrenia: Post hoc analyzes of PANSS individual items and PANSS-derived factors. EUR. Psychiatry 58, 1–9 (2019).

- Bucci, P. & Galderisi, S. Categorizing and assessing negative symptoms. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 30, 201–208 (2017).

- Liemburg, E. et al. Two subdomains of negative symptoms in psychotic disorders: Established and confirmed in two large cohorts. J. Psychiatr. Re s. 47, 718–725 (2013).

- Mucci, A., Merlotti, E., Üçok, A., Aleman, A. & Galderisi, S. Primary and persistent negative symptoms: Concepts, assessments and neurobiological bases. Schizophr. Res . 186, 19–28 (2017).

- Carpenter, W. T., Heinrichs, D. W. & Alphs, L. D. Treatment of negative symptoms. Schizophr. Bull . 11, 440–452 (1985).

- Hasan, A. et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, Part 1: Update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 13, 318–378 (2012).

- Rabinowitz, J. et al. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia – the remarkable impact of inclusion definitions in clinical trials and their consequences.

Schizophr. Res . 150, 334–338 (2013).

Schizophr. Res . 150, 334–338 (2013). - European Medicines Agency. Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products, including depot preparation in the treatment of schizophrenia. (2012).

- Galderisi, S. et al. Persistent negative symptoms in first episode patients with schizophrenia: Results from the European First Episode Schizophrenia Trial. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol . 23, 196–204 (2013).

Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: an unresolved problem

Stahl SM, Buckley PF.

Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007; 115:4-11.

« Negative symptoms can make the patient reserved, inert. He does not disturb others. Therefore, relatives and carers of the patient consider such a condition as a positive aspect of the disease, and not as a dangerous factor that worsens the patient's quality of life.

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: what are they?

Negative symptoms can be grouped into 2- or 5-factor patterns: decreased emotional expressiveness (flattened affect, alogia) and decreased motivation to work and inability to enjoy (anhedonia, asociality, abulia).

Download

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: primary and secondary

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: primary and secondary.

More…

Login to Unlock

Reagila: daily control… Reagila: daily control…

(Reagila® RU: LP-005405 dated 03/18/2019) In this case, treatment Relief of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia should be accompanied by an improvement in the patient's quality of life, in which case the treatment can be considered successful (2). Resistant

More…

Please confirm your consent to the use of cookies

Yes, I agree

No, I refuse

Please confirm that you are a health worker

Showing 0 result(s).

Please log in to see 0 more result(s).

Mental disorders. Schizophrenia and stress disorders

Schizophrenia ⛓

⚙️ This is a serious mental illness that falls into the category of "big psychiatry" and affects all aspects of life - how a person behaves, feels and thinks. Sometimes people with schizophrenia feel that they are losing touch with reality. Therefore, schizophrenia is often associated with depression. In some cases, depressive symptoms are so intense that a doctor may first diagnose depression rather than schizophrenia and start treating it.

⚖️ Basically, schizophrenia is diagnosed between the late teens and 30s. However, a psychiatrist can detect schizophrenia in both a child and an elderly person - the course of the disease and their treatment are arranged somewhat differently. Men are more prone to schizophrenia than women. In most cases, the diagnosis is made after the first episode of psychosis - a vivid manifestation of the symptoms of the disease.

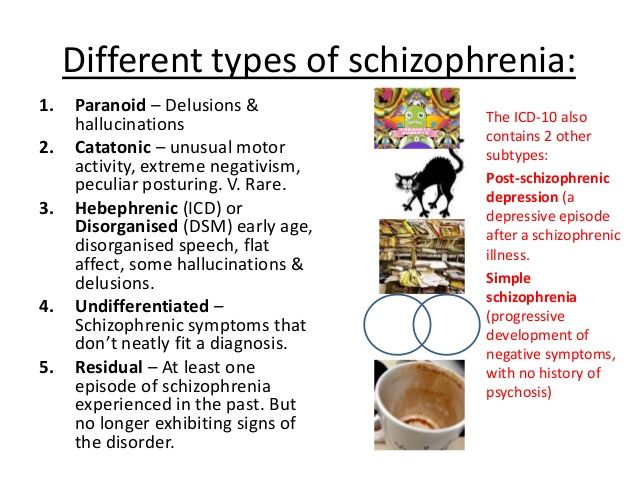

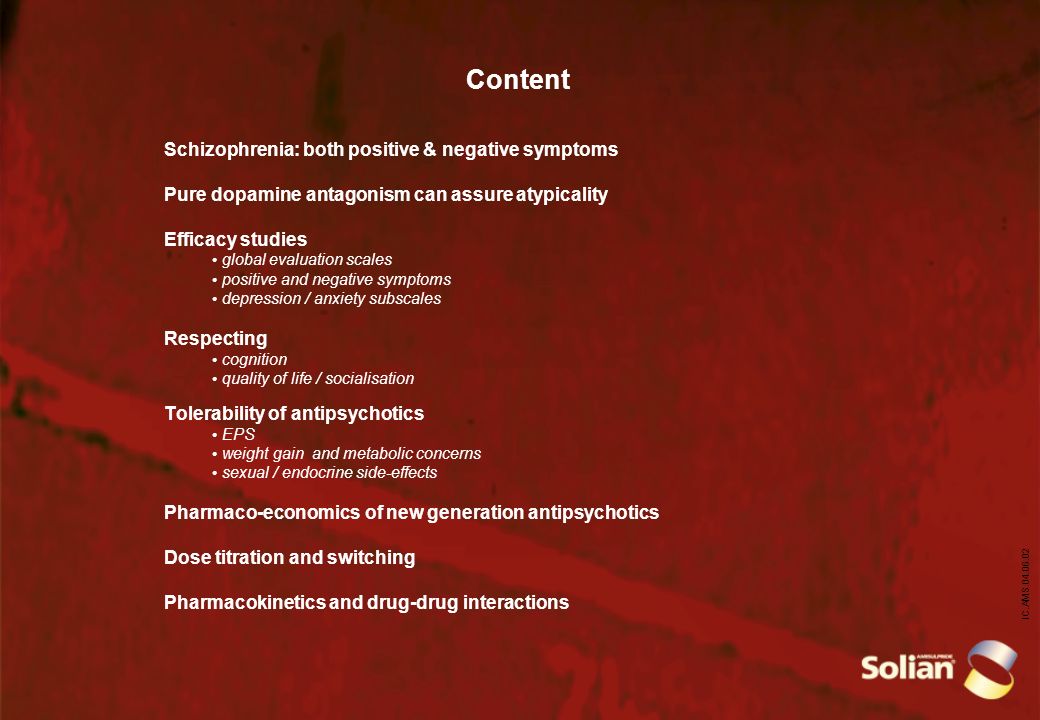

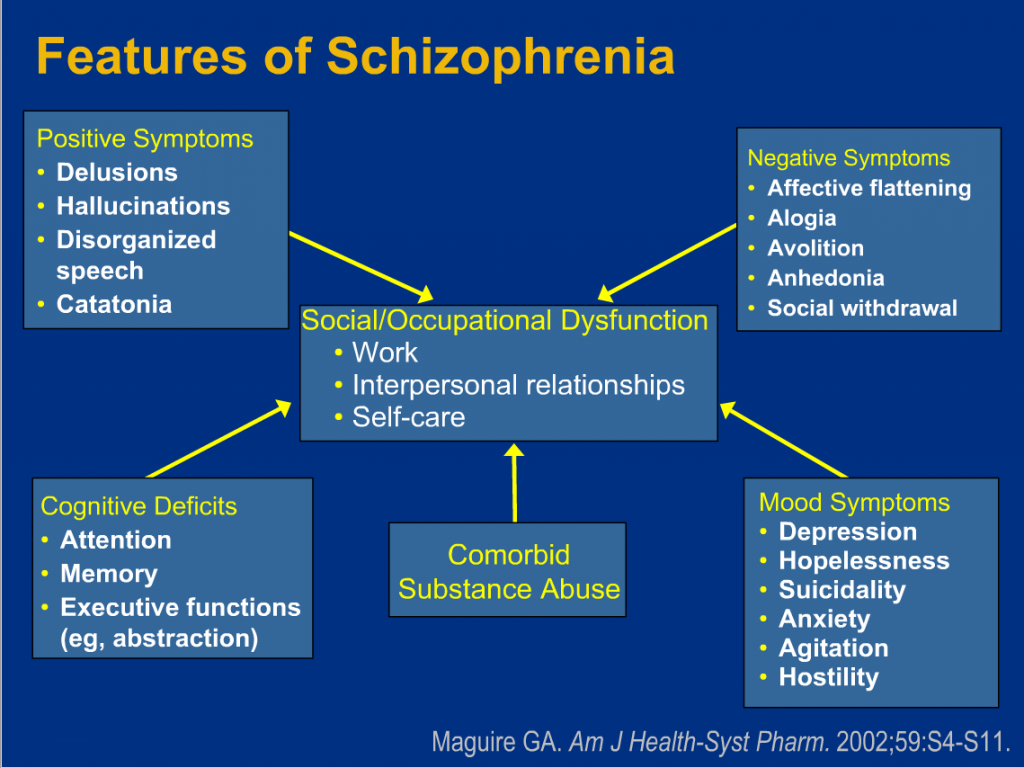

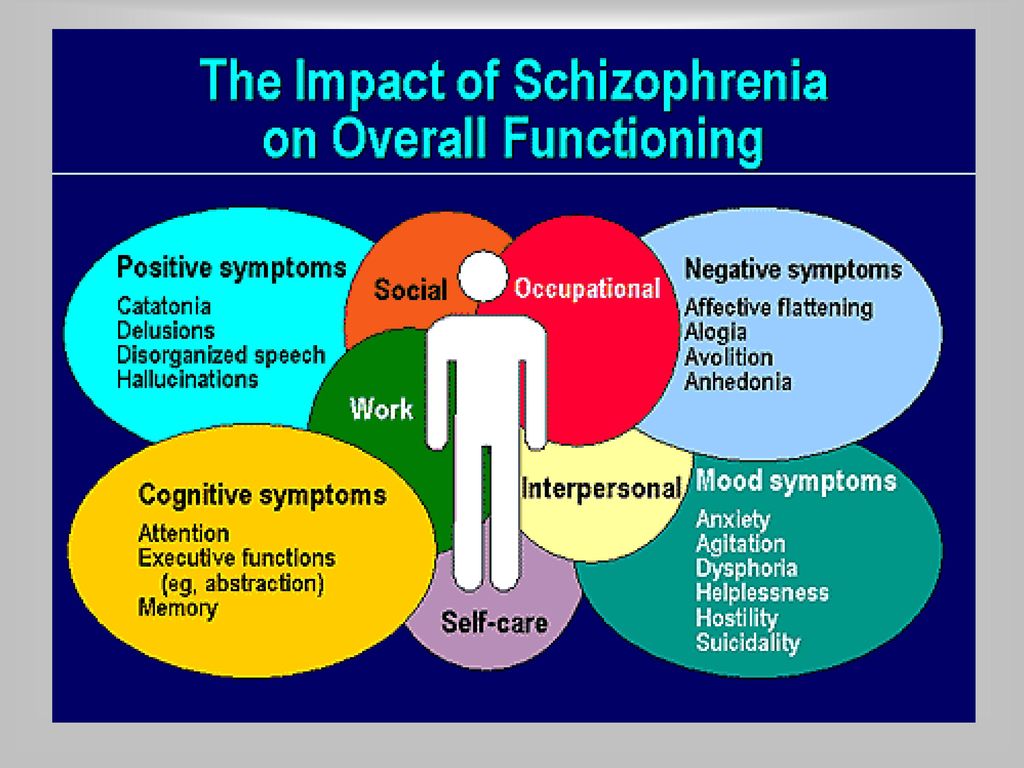

Manifestations of schizophrenia can be divided into three groups: positive, negative and cognitive. About everything in order.

💡 Positive symptoms - “add” to perception and thinking what was not there before: hallucinations, voices, detachment from reality, paranoia, solipsism (for example, radio and TV send personal messages to a person). Speech suffers greatly, becoming less organized: it is quite difficult for an outsider to trace the logical chain.

♟ Negative symptoms - limit, weaken various functions of the psyche: loss of motivation, lack of interest, social isolation, lack of emotion. The combination of these symptoms is called a flat affect - it becomes simply impossible to understand what a person feels by the expression on his face. Expression is lost, the desire to communicate and talk.

🎲 Cognitive symptoms - impaired thinking: concentration, attention, memory. They may be invisible to the patient himself, but quite obvious to others.

🌚 Adolescents and adults have very similar symptoms, but it is more difficult to recognize the disease in adolescence: some mild symptoms of schizophrenia naturally accompany growing up. Therefore, it can be difficult to distinguish, say, withdrawal due to unrequited love from isolation due to the gradual development of psychosis. The use of marijuana, methamphetamines, LSD and other drugs can cause symptoms similar to schizophrenia. Teenagers are more prone to visual hallucinations.

🌔 The main prerequisites for the development of depression are heredity, environment and structural features of the brain. Schizophrenia often manifests itself precisely in adolescence due to structural changes that occur in the brain: new connections are formed especially intensively, and old ones are destroyed.

The treatment of schizophrenia is largely based on the use of neuroleptics (antipsychotic drugs). Antidepressants and tranquilizers are also prescribed. Social integration plays a special role in treatment: support for family and loved ones.