Why do people cry when they are sad

Why Do We Cry? 6 Practical Explanations

When it comes to crying, not all tears are the same.

Basal tears help protect your eyes and keep them lubricated. Reflex tears emerge to wash away smoke, dust, and anything else that might irritate your eyes.

Then there are emotional tears, commonly triggered by rage, joy, or sorrow.

Many people dread these tears and wish they could avoid them entirely. Others have trouble even producing something, even when they feel the need for a good sob.

But no matter how you feel about crying, the fact remains: It’s completely normal. And believe it or not, it serves a purpose beyond clogging your nose and embarrassing you in public.

Turns out, “a cry for help” is more than just a saying. Whether your tears stem from fury or grief, they let other people know you’re having a tough time.

If you feel unable to ask for help directly, your tears can convey this request without words. Keep in mind that this doesn’t mean you’re crying on purpose — they’re a bodily response that most people can’t easily control.

This idea is backed up by a small 2013 study. Participants looked at pictures of sad and neutral faces with and without tears. In both categories, they indicated that people with tears on their faces seemed to have a greater need for support than those without tears.

Think about it this way: How would you respond if you saw someone crying? You might ask, “What’s wrong?” or “Is there anything I can do to help?”

Research from 2016 also suggests people often seem more agreeable and peaceful than aggressive when they cry. This may help explain your willingness to offer support to someone in tears, even if their underlying expression doesn’t necessarily suggest sadness.

If you walk into an open cabinet door or stub your toe on a sharp corner, the sudden shock of intense pain might bring a few tears to your eyes.

You’re more likely to truly cry, however, when you experience significant pain for a long period of time, especially if you can’t do much to get relief.

This type of lingering pain might come from:

- migraine

- kidney stones

- broken bones

- an abscessed tooth

- chronic pain conditions

- endometriosis

- childbirth

Pain severe enough to make you cry does offer one benefit, though. Research suggests that when you cry, your body releases endorphins and oxytocin.

These natural chemical messengers help relieve emotional distress along with physical pain. In other words, crying is a self-soothing behavior.

Crying puts you in a vulnerable position. The emotions you’re experiencing might distract you, for one, but your eyes also blur with tears, making it hard to see.

From an evolutionary perspective, this would put you at a disadvantage in a fight-or-flight situation.

If you see tears as a sign of weakness, as many people do, you might dislike crying because you want to avoid giving an impression of helplessness. But everyone has some vulnerable points, and there’s nothing wrong with letting these show from time to time.

In fact, expressing your weaknesses could generate sympathy from others and promote social bonding.

Most people need at least some support and companionship from others, and these bonds become even more important in times of vulnerability.

When you allow others to see your weaknesses, they may respond with kindness, compassion, and other types of emotional support that contribute to meaningful human connection.

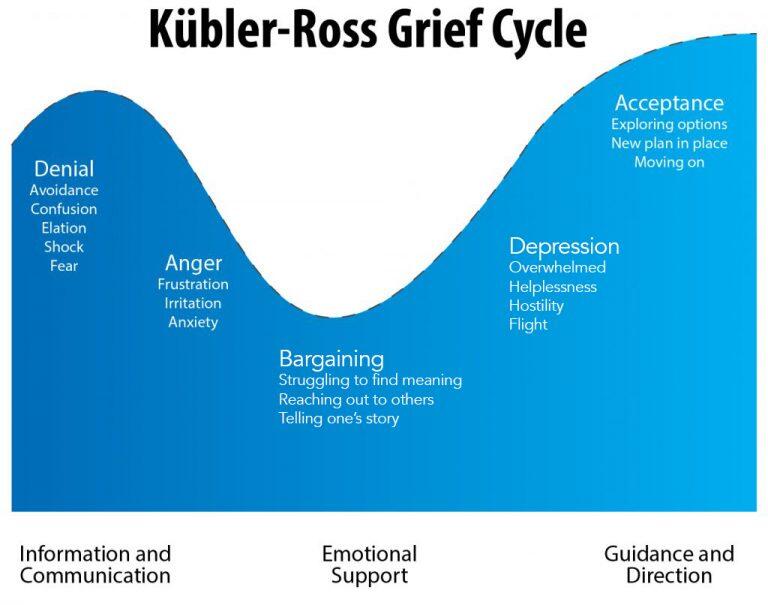

When feelings get so extreme you don’t know how to manage or cope with them, crying can be one way to express them and get relief.

It’s no secret that emotional pain can cause deep distress, so overwhelming feelings of sadness, guilt, or worry can certainly provoke tears.

But any emotions that feel overwhelming or difficult to control can also cause tears, even if they don’t feel particularly painful.

If you’ve ever been moved to tears, you’ll know even emotions typically considered positive, such as love, awe, joy, romantic longing, and gratitude, can make you cry.

Experts believe these happy tears may help you process and regulate intense emotions.

Sympathy crying is absolutely a thing.

Just as your tears might draw concern and support from others, you yourself might feel sympathy when you see another person’s tears or emotional distress. Witnessing their pain could make you cry, too.

It may not even matter whether that person is real or fictional, according to a small 2016 study that explored sympathy crying in response to emotional movies.

Crying in response to someone else’s pain isn’t a bad thing. In fact, it suggests you can take other perspectives into account and imagine a situation from someone else’s point of view. In short, it means you’re an empathetic person.

Some people do cry on purpose in order to manipulate others, but this behavior doesn’t always have malicious intentions behind it.

Instead, people might “turn on the tears,” so to speak, when they don’t know a better way to get their needs met.

Emotional support is a key human need, but it’s not always easy to fulfill.

People who experience abuse, neglect, or other trauma may struggle to make sense of what happened and cope with the resulting emotional pain and turmoil. If they don’t know how to express these unwanted feelings or ask for help, they might use tears to convey their need for sympathy and support.

Learned helplessness — the belief that you can’t do anything to improve your situation — may also prompt the use of tears as a tool.

If you feel like you can’t create change on your own, you might try to earn sympathy from others who can offer assistance. These tears may not necessarily be forced, though, as feelings of frustration and helplessness can make most people cry.

If you find yourself regularly using tears in lieu of more productive approaches to communication and conflict resolution, a therapist can help you explore potential reasons behind this behavior and find healthier ways to express your needs and feelings.

It’s important to consider bigger-picture concepts like personality traits, cultural backgrounds, and biology when it comes to thinking about why humans cry.

Certain personality traits, for example, appear to have some association with crying.

You might cry more frequently if:

- you have a lot of empathy

- your attachment style is anxious, preoccupied, or secure (if it’s dismissive, you’ll probably cry less frequently)

- you score high on Big Five measures of neuroticism

- you have trouble regulating your emotions

Someone’s cultural background can also play a big role in the context of crying. Not surprisingly, people who live in societies where crying is more accepted may cry more frequently.

Men typically cry less than women, perhaps in part because many cultures tend to consider crying a sign of weakness and often discourage boys from crying.

There’s also a biological component: Women generally have more of a hormone called prolactin, which is thought to promote crying.

Men, on the other hand, have higher levels of testosterone, a hormone that could make it more difficult to cry.

Most people cry from time to time for a variety of reasons.

If you feel hesitant about crying around others, remember: Crying doesn’t indicate weakness.

Since tears can actually help people realize you’re experiencing pain and distress, you might benefit more from letting them fall than holding them back.

So go on, cry if you want to (even if it’s not your party).

Just watch out for excessive, uncontrollable tearfulness and crying, since these can sometimes suggest depression. If you find yourself crying more than usual, especially for what seems like no reason at all, it may help to talk to a therapist.

Why Do We Cry? The Science of Crying

Michael Trimble, a behavioral neurologist with the unusual distinction of being one of the world’s leading experts on crying, was about to be interviewed on a BBC radio show when an assistant asked him a strange question: How come some people don’t cry at all?

The staffer went on to explain that a colleague of hers insisted he never cries. She’d even taken him to see Les Misérables, certain it would jerk a tear or two, but his eyes stayed dry. Trimble was stumped. He and the handful of other scientists who study human crying tend to focus their research on wet eyes, not dry ones, so before the broadcast began, he set up an email address—[email protected]—and on the air asked listeners who never cry to contact him. Within a few hours, Trimble had received hundreds of messages.

She’d even taken him to see Les Misérables, certain it would jerk a tear or two, but his eyes stayed dry. Trimble was stumped. He and the handful of other scientists who study human crying tend to focus their research on wet eyes, not dry ones, so before the broadcast began, he set up an email address—[email protected]—and on the air asked listeners who never cry to contact him. Within a few hours, Trimble had received hundreds of messages.

“We don’t know anything about people who don’t cry,” Trimble says now. In fact, there’s also a lot scientists don’t know—or can’t agree on—about people who do cry. Charles Darwin once declared emotional tears “purposeless,” and nearly 150 years later, emotional crying remains one of the human body’s more confounding mysteries. Though some other species shed tears reflexively as a result of pain or irritation, humans are the only creatures whose tears can be triggered by their feelings. In babies, tears have the obvious and crucial role of soliciting attention and care from adults. But what about in grownups? That’s less clear. It’s obvious that strong emotions trigger them, but why?

But what about in grownups? That’s less clear. It’s obvious that strong emotions trigger them, but why?

There’s a surprising dearth of hard facts about so fundamental a human experience. Scientific doubt that crying has any real benefit beyond the physiological—tears lubricate the eyes—has persisted for centuries. Beyond that, researchers have generally focused their attention more on emotions than on physiological processes that can appear to be their by-products: “Scientists are not interested in the butterflies in our stomach, but in love,” writes Ad Vingerhoets, a professor at Tilburg University in the Netherlands and the world’s foremost expert on crying, in his 2013 book, Why Only Humans Weep.

But crying is more than a symptom of sadness, as Vingerhoets and others are showing. It’s triggered by a range of feelings—from empathy and surprise to anger and grief—and unlike those butterflies that flap around invisibly when we’re in love, tears are a signal that others can see. That insight is central to the newest thinking about the science of crying.

That insight is central to the newest thinking about the science of crying.

Darwin wasn’t the only one with strong opinions about why humans cry. By some calculations, people have been speculating about where tears come from and why humans shed them since about 1,500 B.C. For centuries, people thought tears originated in the heart; the Old Testament describes tears as the by-product of when the heart’s material weakens and turns into water, says Vingerhoets. Later, in Hippocrates’ time, it was thought that the mind was the trigger for tears. A prevailing theory in the 1600s held that emotions—especially love—heated the heart, which generated water vapor in order to cool itself down. The heart vapor would then rise to the head, condense near the eyes and escape as tears.

Finally, in 1662, a Danish scientist named Niels Stensen discovered that the lacrimal gland was the proper origin point of tears. That’s when scientists began to unpack what possible evolutionary benefit could be conferred by fluid that springs from the eye. Stensen’s theory: Tears were simply a way to keep the eye moist.

Stensen’s theory: Tears were simply a way to keep the eye moist.

Few scientists have devoted their studies to figuring out why humans weep, but those who do don’t agree. In his book, Vingerhoets lists eight competing theories. Some are flat-out ridiculous, like the 1960s view that humans evolved from aquatic apes and tears helped us live in saltwater. Other theories persist despite lack of proof, like the idea popularized by biochemist William Frey in 1985 that crying removes toxic substances from the blood that build up during times of stress.

Evidence is mounting in support of some new, more plausible theories. One is that tears trigger social bonding and human connection. While most other animals are born fully formed, humans come into the world vulnerable and physically unequipped to deal with anything on their own. Even though we get physically and emotionally more capable as we mature, grownups never quite age out of the occasional bout of helplessness. “Crying signals to yourself and other people that there’s some important problem that is at least temporarily beyond your ability to cope,” says Jonathan Rottenberg, an emotion researcher and professor of psychology at the University of South Florida. “It very much is an outgrowth of where crying comes from originally.”

“Crying signals to yourself and other people that there’s some important problem that is at least temporarily beyond your ability to cope,” says Jonathan Rottenberg, an emotion researcher and professor of psychology at the University of South Florida. “It very much is an outgrowth of where crying comes from originally.”

Scientists have also found some evidence that emotional tears are chemically different from the ones people shed while chopping onions—which may help explain why crying sends such a strong emotional signal to others. In addition to the enzymes, lipids, metabolites and electrolytes that make up any tears, emotional tears contain more protein. One hypothesis is that this higher protein content makes emotional tears more viscous, so they stick to the skin more strongly and run down the face more slowly, making them more likely to be seen by others.

Tears also show others that we’re vulnerable, and vulnerability is critical to human connection. “The same neuronal areas of the brain are activated by seeing someone emotionally aroused as being emotionally aroused oneself,” says Trimble, a professor emeritus at University College London. “There must have been some point in time, evolutionarily, when the tear became something that automatically set off empathy and compassion in another. Actually being able to cry emotionally, and being able to respond to that, is a very important part of being human.”

“There must have been some point in time, evolutionarily, when the tear became something that automatically set off empathy and compassion in another. Actually being able to cry emotionally, and being able to respond to that, is a very important part of being human.”

A less heartwarming theory focuses on crying’s usefulness in manipulating others. “We learn early on that crying has this really powerful effect on other people,” Rottenberg says. “It can neutralize anger very powerfully,” which is part of the reason he thinks tears are so integral to fights between lovers—particularly when someone feels guilty and wants the other person’s forgiveness. “Adults like to think they’re beyond that, but I think a lot of the same functions carry forth,” he says.

A small study in the journal Science that was widely cited—and widely hyped by the media—suggested that tears from women contained a substance that inhibited the sexual arousal of men. “I won’t pretend to be surprised that it generated all the wrong headlines,” says Noam Sobel, one of the study’s authors and a professor of neurobiology at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. Tears might be lowering sexual arousal—but the bigger story, he thinks, is that they might be reducing aggression, which the study didn’t look at. Men’s tears may well have the same effect. He and his group are currently wading through the 160-plus molecules in tears to see if there’s one responsible.

Tears might be lowering sexual arousal—but the bigger story, he thinks, is that they might be reducing aggression, which the study didn’t look at. Men’s tears may well have the same effect. He and his group are currently wading through the 160-plus molecules in tears to see if there’s one responsible.

What all of this means for people who don’t cry is a question researchers are now turning to. If tears are so important for human bonding, are people who never cry perhaps less socially connected? That’s what preliminary research is finding, according to clinical psychologist Cord Benecke, a professor at the University of Kassel in Germany. He conducted intimate, therapy-style interviews with 120 individuals and looked to see if people who didn’t cry were different from those who did. He found that noncrying people had a tendency to withdraw and described their relationships as less connected. They also experienced more negative aggressive feelings, like rage, anger and disgust, than people who cried.

More research is needed to determine whether people who don’t cry really are different from the rest of us, and some is soon to come: those emailers who heard Trimble on the radio that morning in 2013 are now the subjects of the first scientific study of people with such a tendency.

Virtually no evidence exists that crying comes with any positive effects on health. Yet the myth persists that it’s an emotional and physical detox, “like it’s some kind of workout for your body,” Rottenberg says. One analysis looked at articles about crying in the media—140 years’ worth—and found that 94% described it as good for the mind and body and said holding back tears would result in the opposite. “It’s kind of a fable,” says Rottenberg. “There’s not really any research to support that.”

Also overblown is the idea that crying is always followed by relief. “There’s an expectation that we feel better after we cry,” says Randy Cornelius, a professor of psychology at Vassar College. “But the work that’s been done on this indicates that, if anything, we don’t feel good after we cry. ” When researchers show people a sad movie in a laboratory and then measure their mood immediately afterward, those who cry are in worse moods than those who don’t.

” When researchers show people a sad movie in a laboratory and then measure their mood immediately afterward, those who cry are in worse moods than those who don’t.

But other evidence does back the notion of the so-called good cry that leads to catharsis. One of the most important factors, it seems, is giving the positive effects of crying—the release—enough time to sink in. When Vingerhoets and his colleagues showed people a tearjerker and measured their mood 90 minutes later instead of right after the movie, people who had cried were in a better mood than they had been before the film. Once the benefits of crying set in, he explains, it can be an effective way to recover from a strong bout of emotion.

Modern crying research is still in its infancy, but the mysteries of tears—and the recent evidence that they’re far more important than scientists once believed—drive Vingerhoets and the small cadre of tear researchers to keep at it. “Tears are of extreme relevance for human nature,” says Vingerhoets. “We cry because we need other people. So Darwin,” he says with a laugh, “was totally wrong.”

“We cry because we need other people. So Darwin,” he says with a laugh, “was totally wrong.”

This is an abridged version of an article that appears in the March 07, 2016 issue of TIME.

Write to Mandy Oaklander at [email protected].

Why does a person cry when he is sad?

Is crying helpful or harmful? Do animals have emotions?

Answered by Ekaterina Antonova

analytical psychologist

If you try to offend her cub in front of a cat, you risk testing the sharpness of her claws for yourself. But this will not happen because the cat loves the kitten. The instinct associated with the protection of offspring is triggered.

If you try to take a bone from a hungry dog, you will provoke a reaction very similar to anger. Although in fact it is also an instinct.

Animals have no emotions. But there are instincts that, when triggered, resemble them. So, when a dog is abandoned by its owner, it whines because the instinct of affection is triggered. When grief occurs in a person, he most often cries. Crying is perhaps the safest way to express sadness.

When grief occurs in a person, he most often cries. Crying is perhaps the safest way to express sadness.

Under stress, the body synthesizes toxic substances: leucine-enkephalin and prolactin, which are excreted only with tears , and emotional, when tears appear during a nervous shock. Under stress, the body synthesizes toxic substances: leucine-enkephalin and prolactin, which are excreted only with tears. It is no coincidence that when a person cries, he feels lighter.

But etiquette dictates that crying in public is not good, and men should not show their emotions at all. Under the influence of public opinion, a person learns to suppress tears in himself, but this does not mean that sadness goes away. Negative emotions accumulate and sooner or later find another way to splash out. A person can vent evil on loved ones, drink an extra glass of alcohol, smoke or fight. Restraint of emotions affects the nervous system and can cause cardiovascular disease.

It turns out that tears are the best way to relieve nervous tension and remove harmful substances from the body.

In addition, they normalize blood pressure, increase the body's resistance to infections and reduce the risk of developing diseases of the gastrointestinal tract.

They have one more useful property: they influence other people. So, children often cry to get attention. And it helps! They are approached, pity, warm, fed and solve their other problems. It works for adults too. Even William Shakespeare called tears "weapons of women."

Why does a person not have a mating season?

Can animals express emotions?

The site may use materials from Facebook and Instagram Internet resources owned by Meta Platforms Inc., which is prohibited in the Russian Federation.

emotions

people

animals

Question: what is it?

Question: what is it?

Hint: purpose - household, time - from the 15th century to the present day

October 4, 2022

Question: what is it?

Question: what is it?

Hint: they are found on the beaches after storms and low tides

Daria Telegina

August 12, 2022

Question: what is it?

Question: what is it?

Hint: place - USA, time - 1940s

Julia Skopich

February 24, 2022

2500 Aussies completely naked for a photo shoot

November 27, 2022

In Australia, a 3-meter python dragged a child to the bottom of the pool

November 27, 2022

483 Celtic gold coins stolen from a German museum

November 26, 2022

The most beautiful cow was chosen in Yakutia

November 26, 2022

Top 10 largest dinosaurs in the world

What is the minimum temperature a person can tolerate?

Speed records

10 most difficult languages

10 must-see places in Tunisia

Seven facts about crows and crows

The highest mountains in the world

We use cookies

JSC "My Planet" uses cookies to improve the operation and use of the site https://moya-planeta.

ru/. More detailed information about the Policy of JSC "My Planet" on working with cookies can be found here, about the Policy of JSC "My Planet" regarding the processing of personal data can be found here. By continuing to use the site https://moya-planeta.ru/, you confirm that you have been informed about the use of cookies by the site https://moya-planeta.ru/ and agree with the Policy of JSC "My Planet" on working with cookies. files. You can disable cookies in your browser settings.

Cry, it will get easier... Or won't it? Truth and myths about tears

- Christian Jarrett

- for BBC Future

Image copyright, Getty Images

We are used to thinking that when a person cries, it becomes easier for him: something like catharsis sets in, tears purify the soul and lighten the heart ... But, on the other hand, crying in public is a sign of weakness, isn't it? ? Researchers claim that both are wrong.

When Theresa May announced her resignation as Prime Minister in Downing Street, it was noticeable: just a little more, and she burst into tears. And this did not fail to note the journalists. Photographs of Mei, barely holding back her tears, hit the front pages of newspapers.

Observers were quick to point out that the Prime Minister finally showed her human face, throwing off the mask of isolation and arrogance. Even many of May's critics admitted that they felt sympathy for her at that moment.

It seems that shedding tears in front of the TV cameras is good for a politician's reputation.

But how we perceive such scenes, with sympathy or cynical grin, depends on our own ideas about crying and its consequences for a person.

These perceptions, psychologists from the University of Queensland (Australia) emphasize, in turn affect how much you tend to cry yourself and how you feel afterwards.

"How often a person cries, how they feel afterwards, and whether it helps him cope with emotional tension, most likely depends on his ideas and expectations associated with crying, social context and past experience," emphasize in a recent study report by Lee Sharman and her colleagues.

Image copyright DANIEL SORABJI/AFP/Getty Images

Image captionOn May 25, the front pages of the British press were filled with pictures of the prime minister on the verge of tears. Some took it sympathetically, some shrugged.

To investigate this connection, Sharman and colleagues invented the first ever standardized crying attitude test.

They first asked a small group of volunteers a series of open-ended questions such as "What do you think is the effect of crying in public?"

- Why do we smile when we feel bad

- Why do people learn to cry

- Is it so bad to be British reserved?

Then, based on the responses they received, they created 40 possible statements, such as "crying makes you feel better" or "crying makes you vulnerable.

"

After that, two groups of hundreds of volunteers on the Internet assessed for themselves the validity of these statements on a seven-point scale.

Researchers led by Sharmain deduced from their responses three main types of representations of crying:

- Crying alone is good. Those who fall into this category agree with statements like "crying helps me when I'm shocked or overwhelmed by something" or "I know I'll feel better if I cry."

- Crying alone is useless. "After crying, I feel worse when I am alone." "After crying, I feel even worse."

- Crying in public is harmful . "I am ashamed when I cry in front of strangers", "It seems to me that I am judged when I cry in the presence of colleagues at work."

These are the first results of a systematic study of people's beliefs about the benefits or harms of crying and how they are influenced by various factors such as personality or gender.

It is worth noting that these are mainly representations of white people living in the West.

Participants in the study had neither an overtly negative nor overtly positive opinion about crying alone.

But still they were more inclined to disagree with the statement that it is harmful (average result - 2 points, when 0 means completely disagree, and 7 - completely agree with the harmfulness of crying).

Summarizing the results of the responses, we can say that the participants thought that crying alone is unlikely to harm you and may even be beneficial.

Image copyright James Williamson - AMA/Getty Images

Image captionCrying on the sports ground is perceived differently than tears in the meeting room (Swansea goalkeeper Lukasz Fabianski is pictured after the team's relegation match) from the Premier League

Collective beliefs about the benefits or harms of crying are often based on the stories of others.

0003

For example, American psychologist Randolph Cornelius analyzed 72 popular media articles on crying published over 140 years up to 1985 and found that 94% of them described tears as helpful.

Many well-known scientists and doctors have proclaimed the cleansing benefits of crying.

For example, Henry Maudsley (a famous British psychiatrist, after whom one of the hospitals in south London is named) argued that "sadness, which is not allowed to pour out in tears, can soon make the internal organs cry."

However, modern researchers generally come to the opposite conclusion: after crying, you often feel even worse, and there is no smell of catharsis. At best, its effect is very moderate.

It is also interesting what happens to us when a sad movie makes us cry. According to some experiments, this greatly worsened the mood of the volunteers.

However, one of the recent studies showed that tears during a sad movie worsen the mood only at first, but after an hour and a half the mood improves significantly.

In general, the picture that the results of recent research paint for us is this: tears do not lead to catharsis at all, after them we most often do not feel better.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Photo caption,When we see someone cry, we want to support them

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

End of story Podcast

What about tears in public? The results for Sharmain were close to the average here too - the participants hesitated and did not want to evaluate crying in the environment of other people too unambiguously.

Indeed, the consequences of tears in public can be different.

For example, one 2016 study found that, in general, whiny employees were considered less competent - especially men (for the purity of the experiment, participants were shown drawings, not real people).

However, an attempt by the same researchers to replicate the results in the second experiment failed.

Another study found the importance of social context: those prone to tears were rated more harshly if they were at work and if they were men.

Some studies suggest that women who cry at work are more likely to be seen as weak and manipulative.

Of the others, quite the contrary, it was tearful men who deserved a negative reputation in the team.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,From an early age, we are brought up in a certain way regarding the open expression of emotions, and these rules often depend on the sex of the child

It is important to note that women in those studies were generally viewed as less competent employees, no matter how they behaved - even compared to men who allow themselves to shed tears surrounded by work colleagues.

However, crying in public can have its benefits.

For example, people instinctively want to emotionally support a crying person - seeing a crying face, we rush to help. This is confirmed by the example of Theresa May.

Sharmain's study showed interesting differences in how people view tears.

For example, those who were accustomed to trusting their emotions, not being ashamed of them, and relying on the emotional support of others were more likely to think that crying is good both in solitude and in public.

Well, those who think that there is nothing useful in crying and are not very friendly with their emotions, these people do not control them well.

image copyrightAlexander Hassenstein - FIFA/FIFA via Getty Images

Image caption,Tears are far less cleansing than we might think (pictured is an aged Pele crying at the Ballon d'Or ceremony in 2013

Sharmain and her colleagues believe there is a link between

"It is possible that those who find crying unacceptable and think that society expects them to behave positively suppress their own emotions, embarrassed by their open expression", she says

Researchers have developed a new scale that will make it easier to find out if this is true.

It is likely that a dynamic relationship is at work here: say, if you are firmly convinced that it is shameful to cry in public, then if this happens to you, this experience will not bring you anything good.

If this hypothesis is confirmed, then it will be quite in the spirit of modern psychology to believe that how these emotions affect you depends on your views on emotions.

For example, people who see benefit in a bad mood suffer less from it when it happens to them.

Of course, we should be careful when we try to understand the thoughts and state of another person, but perhaps Theresa May's usually reserved manner is due to her own negative attitude towards the display of emotions in public.

Perhaps Theresa May learned from her sympathetic reaction to her emotional farewell speech that this kind of openness has its benefits. But it was too late to save her political career.

"It may very well be," Sharmain writes, "that attitudes toward crying change throughout life as a person experiences various social and interpersonal consequences of crying and draws appropriate conclusions for himself.

Learn more