Black box warning on antidepressants

Duty to Warn: Antidepressant Black Box Suicidality Warning Is Empirically Justified

1. Hazell P, O’Connell D, Heathcote D, Robertson J, Henry D. Efficacy of tricyclic drugs in treating child and adolescent depression: a meta-analysis. BMJ (1995) 310:897–901. 10.1136/bmj.310.6984.897 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Keller MB, Ryan ND, Strober M, Klein RG, Kutcher SP, Birmaher B, et al. Efficacy of paroxetine in the treatment of adolescent major depression: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2001) 40:762–72. 10.1097/00004583-200107000-00010 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Wagner KD, Ambrosini P, Rynn M, Wohlberg C, Yang R, Greenbaum MS, et al. Efficacy of sertraline in the treatment of children and adolescents with major depressive disorder: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA (2003) 290:1033–41. 10.1001/jama.290.8.1033 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Emslie GJ, Rush J, Weinberg WA, Kowatch RA, Hughes CW, Carmody T, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in children and adolescents with depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry (1997) 54:1031–7. 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230069010 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Gardner JF, Soeken K, Boles M, et al. Rising prevalence of antidepressants among US Youths. Pediatrics (2002) 109:721–7. 10.1542/peds.109.5.721 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Whittington CJ, Kendall T, Fonagy P, Cottrell D, Cotgrove A, Boddington E. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in childhood depression: Systematic review of published versus unpublished data. Lancet (2004) 363:1341–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16043-1 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Leslie LK, Newman TB, Chesney PJ, Perrin JM. The food and drug administration’s deliberations on antidepressant use in pediatric patients. Pediatrics (2005) 116:195–204. 10.1542/peds.2005-0074 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. Silver Spring, MD; (2007) 164:1035–43. 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1035 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. Silver Spring, MD; (2007) 164:1035–43. 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1035 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Hammad TA. Relationship between psychotropic drugs and pediatric suicidality. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration; (2004). Available at: https://www.dropbox.com/s/gto5w4qcumk9hic/2004%20FDA%20Hammad.pdf?dl=0 [Accessed September 2, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

10. Food and Drug Administration Suicidality and antidepressant drugs (2006). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/77404/download.

11. Kwon A, Song J, Yook K-H, Jon D-I, Jung MH, Hong N, et al. Predictors of suicide attempts in clinically depressed korean adolescents. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci (2016) 14:383–7. 10.9758/cpn.2016.14.4.383 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Wichstrøm L. Predictors of adolescent suicide attempts: a nationally representative longitudinal study of Norwegian adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2000) 39:603–10. 10.1097/00004583-200005000-00014 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Wichstrøm L. Predictors of adolescent suicide attempts: a nationally representative longitudinal study of Norwegian adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2000) 39:603–10. 10.1097/00004583-200005000-00014 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Psychosocial risk factors for future adolescent suicide attempts. J Consult Clin Psychol (1994) 62:297–305. 10.1037//0022-006X.62.2.297 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Marcus SM, Bhaumik DK, Erkens JA, et al. Early evidence on the effects of regulators’ suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry (2007) 164:1356–63. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030454 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Lu CY, Zhang F, Lakoma MD, Madden JM, Rusinak D, Penfold RB, et al. Changes in antidepressant use by young people and suicidal behavior after FDA warnings and media coverage: quasi-experimental study. BMJ (2014) 348:g3596. 10.1136/bmj.g3596 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1136/bmj.g3596 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Sparks JA, Duncan BL. Outside the black box: re-assessing pediatric antidepressant prescription. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2013) 22:240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Davis JM, Mann JJ. Suicidal thoughts and behavior with antidepressant treatment: reanalysis of the randomized placebo-controlled studies of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2012) 69:580–7. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2048 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Food and Drug Administration Department of health and human services food and drug administration center for drug evaluation and research psychopharmacologic drugs advisory committee with the pediatric subcommittee of the anti-infective drugs advisory committee. (2004). Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20170118093331/http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/04/transcripts/4006T1. htm [Accessed September 10, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

htm [Accessed September 10, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

19. FDA’s role in protecting the public health: Examining FDA’s review of safety and efficacy concerns in anti-depressant use by children. (2004). Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-108hhrg96099/html/CHRG-108hhrg96099.htm [Accessed September 12, 2019].

20. Apter A, Lipschitz A, Fong R, Carpenter DJ, Krulewicz S, Davies JT, et al. Evaluation of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in children and adolescents taking paroxetine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol (2006) 16:77–90. 10.1089/cap.2006.16.77 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Kobak KA, Kane JM, Thase ME, Nierenberg AA. Why do clinical trials fail?: the problem of measurement error in clinical trials: time to test new paradigms? J Clin Psychopharmacol (2007) 27:1–5. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31802eb4b7 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Engelhardt N, Feiger AD, Cogger KO, Sikich D, DeBrota DJ, Lipsitz JD, et al. Rating the raters: assessing the quality of Hamilton rating scale for depression clinical interviews in two industry-sponsored clinical drug trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol (2006) 26:71–4. 10.1097/01.jcp.0000194621.61868.7c [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J Clin Psychopharmacol (2006) 26:71–4. 10.1097/01.jcp.0000194621.61868.7c [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Kobak KA, Engelhardt N, Williams JB, Lipsitz JD. Rater training in multicenter clinical trials: issues and recommendations. J Clin Psychopharmacol (2004) 24:113–7. 10.1097/01.jcp.0000116651.91923.54 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Khan A, Faucett J, Brown WA. Magnitude of placebo response and response variance in antidepressant clinical trials using structured, taped and appraised rater interviews compared to traditional rating interviews. J Psychiatr Res (2014) 51:88–92. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.01.005 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Ignaszewski MJ, Waslick B. Update on randomized placebo-controlled trials in the past decade for treatment of major depressive disorder in child and adolescent patients: a systematic review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol (2018). 10.1089/cap.2017.0174 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Findling RL, Robb A, Bose A. Escitalopram in the treatment of adolescent depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled extension trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol (2013) 23:468–80. 10.1089/cap.2012.0023 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Escitalopram in the treatment of adolescent depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled extension trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol (2013) 23:468–80. 10.1089/cap.2012.0023 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Patrick AR, Miller M, Barber CW, Wang PS, Canning CF, Schneeweiss S. Identification of hospitalizations for intentional self-harm when E-codes are incompletely recorded. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf (2010) 19:1263–75. 10.1002/pds.2037 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Barber CW, Miller M, Azrael D. Re: Changes in antidepressant use by young people and suicidal behavior after FDA warnings and media coverage: quasi-experimental study. BMJ (2014) 348:g3596. 10.1136/bmj.g3596 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Isacsson G, Ahlner J. Antidepressants and the risk of suicide in young persons–prescription trends and toxicological analyses. Acta Psychiatr Scand (2014) 129:296–302. 10.1111/acps.12160 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1111/acps.12160 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Larsson J. Antidepressants and suicide among young women in Sweden 1999–2013. Int J Risk Saf Med (2017) 29:101–6. 10.3233/JRS-170739 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Katz LY, Kozyrskyj AL, Prior HJ, Enns MW, Cox BJ, Sareen J. Effect of regulatory warnings on antidepressant prescription rates, use of health services and outcomes among children, adolescents and young adults. CMAJ (2008) 178:1005–11. 10.1503/cmaj.071265 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Gibbons RD, Hur K, Brown CH, Davis JM, Mann JJ. Benefits from antidepressants: synthesis of 6-week patient-level outcomes from double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2012) 69:572–9. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2044 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Spielmans GI, Jureidini J, Healy D, Purssey R. Inappropriate data and measures lead to questionable conclusions. JAMA Psychiatry (2013) 70:121–3. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.747 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Inappropriate data and measures lead to questionable conclusions. JAMA Psychiatry (2013) 70:121–3. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.747 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Davis JM, Mann JJ. Inappropriate data and measures lead to questionable conclusions—reply. JAMA Psychiatry (2013) 70:121–3. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.749 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Spielmans GI, Point-Counterpoint With Gibbons (2013). Available at: https://www.dropbox.com/s/rqjvtu8eq9zpljl/Jamap_pt_ctrpt.pdf?dl=0 [Accessed September 12, 2019].

36. Walkup JT. Antidepressant efficacy for depression in children and adolescents: Industry- and NIMH-funded studies. Am J Psychiatry (2017) 174:430–7. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16091059 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Högberg G, Antonuccio DO, Healy D. Suicidal risk from TADS study was higher than it first appeared. Int J Risk Saf Med (2015) 27:85–91. 10.3233/JRS-150645 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Westergren T, Narum S, Klemp M. Critical appraisal of adverse effects reporting in the ‘treatment for adolescents with depression Study (TADS).’ BMJ Open (2019) 9:e026089. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026089 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Westergren T, Narum S, Klemp M. Critical appraisal of adverse effects reporting in the ‘treatment for adolescents with depression Study (TADS).’ BMJ Open (2019) 9:e026089. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026089 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Emslie G, Kratochvil C, Vitiello B, Silva S, Mayes T, McNulty S, et al. Treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS): safety results. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2006) 45:1440–55. 10.1097/01.chi.0000240840.63737.1d [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Vitiello B, Silva SG, Rohde P, Kratochvil CJ, Kennard BD, Reinecke MA, et al. Suicidal events in the Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS). J Clin Psychiatry (2009) 70:741–7. 10.4088/JCP.08m04607 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Silverman MM, Berman AL, Sanddal ND, O'carroll PW, Joiner TE. Rebuilding the Tower of Babel: A Revised Nomenclature for the Study of Suicide and Suicidal Behaviors Part 2: Suicide-Related Ideations, Communications, and Behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav (2007) 37(3):264–77. 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Suicide Life Threat Behav (2007) 37(3):264–77. 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, et al. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry (2011) 168:1266–77. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Matarazzo BB, Brown GK, Stanley B, Forster JE, Billera M, Currier GW, et al. Predictive validity of the columbia-suicide severity rating scale among a cohort of at-risk veterans. Suicide Life Threat Behav (2018) 5(49):1255–65 . 10.1111/sltb.12515 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Youngstrom EA, Hameed A, Mitchell MA, Van Meter AR, Freeman AJ, Algorta GP, et al. Direct comparison of the psychometric properties of multiple interview and patient-rated assessments of suicidal ideation and behavior in an adult psychiatric inpatient sample. J Clin Psychiatry (2015) 76:1676–82. 10.4088/JCP.14m09353 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J Clin Psychiatry (2015) 76:1676–82. 10.4088/JCP.14m09353 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Sheehan DV, Alphs LD, Mao L, Li Q, May RS, Bruer EH, et al. Comparative validation of the S-STS, the ISST-Plus, and the C–SSRS for assessing the suicidal thinking and behavior FDA 2012 suicidality categories. Innov Clin Neurosci (2014) 11:32–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Emslie GJ, Ventura D, Korotzer A, Tourkodimitris S. Escitalopram in the treatment of adolescent depression: a randomized placebo-controlled multisite trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2009) 48:721–9. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a2b304 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Atkinson SD, Prakash A, Zhang Q, Pangallo BA, Bangs ME, Emslie GJ. March JS. A double-blind efficacy and safety study of duloxetine flexible dosing in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol (2014) 24:180–9. 10.1089/cap.2013.0146 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Emslie GJ, Prakash A, Zhang Q, Pangallo BA, Bangs ME, March JS. A double-blind efficacy and safety study of duloxetine fixed doses in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol (2014) 24:170–9. 10.1089/cap.2013.0096 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Emslie GJ, Prakash A, Zhang Q, Pangallo BA, Bangs ME, March JS. A double-blind efficacy and safety study of duloxetine fixed doses in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol (2014) 24:170–9. 10.1089/cap.2013.0096 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Reynolds WM. Professional Manual for the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL: (1987). [Google Scholar]

50. Wagner KD, Robb AS, Findling RL, Jin J, Gutierrez MM, Heydorn WE. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of citalopram for the treatment of major depression in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry (2004) 161:1079–83. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.1079 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Jureidini JN, Amsterdam JD, McHenry LB. The citalopram CIT-MD-18 pediatric depression trial: Deconstruction of medical ghostwriting, data mischaracterisation and academic malfeasance. Int J Risk Saf Med (2016) 28:33–43. 10.3233/JRS-160671 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.3233/JRS-160671 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Atkinson S, Lubaczewski S, Ramaker S, England RD, Wajsbrot DB, Abbas R, et al. Desvenlafaxine versus placebo in the treatment of children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol (2018) 28:55–65. 10.1089/cap.2017.0099 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Weihs KL, Murphy W, Abbas R, Chiles D, England RD, Ramaker S, et al. Desvenlafaxine versus placebo in a fluoxetine-referenced study of children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol (2018) 28:36–46. 10.1089/cap.2017.0100 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

54. Hughes S, Cohen D, Jaggi R. Differences in reporting serious adverse events in industry sponsored clinical trial registries and journal articles on antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open (2014) 4:e005535. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005535 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

55. Sharma T, Guski LS, Freund N, Gøtzsche PC. Suicidality and aggression during antidepressant treatment: systematic review and meta-analyses based on clinical study reports. BMJ (2016) 352:i65. 10.1136/bmj.i65 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Sharma T, Guski LS, Freund N, Gøtzsche PC. Suicidality and aggression during antidepressant treatment: systematic review and meta-analyses based on clinical study reports. BMJ (2016) 352:i65. 10.1136/bmj.i65 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

56. https://study329.org/questions-answers/ Study 329 Quest Answ Available at: https://study329.org/questions-answers/ (accessed 2019)

57. Le Noury J, Nardo JM, Healy D, Jureidini J, Raven M, Tufanaru C, et al. Restoring Study 329: efficacy and harms of paroxetine and imipramine in treatment of major depression in adolescence. BMJ (2015) 351:h5320. 10.1136/bmj.h5320 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

58. Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Strombom IM, Dominguez S, Fawcett J, Licinio J, et al. Ecological studies of antidepressant treatment and suicidal risks. Harv Rev Psychiatry (2007) 15:133–45. 10.1080/10673220701551102 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

59. Kapusta ND, Tran US, Rockett IRH, De Leo D, Naylor CPE, Niederkrotenthaler T, et al. Declining autopsy rates and suicide misclassification: a cross-national analysis of 35 countries. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2011) 68:1050–7. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.66 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Declining autopsy rates and suicide misclassification: a cross-national analysis of 35 countries. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2011) 68:1050–7. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.66 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

60. Hoyert DL. The changing profile of autopsied deaths in the United States, 1972-2007. Natl Cent Health Stat Data Brief (2011) 67:1–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. McLoughlin AB, Gould MS, Malone KM. Global trends in teenage suicide: 2003–2014. QJM (2015) 108:765–80. 10.1093/qjmed/hcv026 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

62. Vilhelmsson A, Svensson T, Meeuwisse A, Carlsten A. Experiences from consumer reports on psychiatric adverse drug reactions with antidepressant medication: a qualitative study of reports to a consumer association. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol (2012) 13:19. 10.1186/2050-6511-13-19 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

63. Tint A, Haddad PM, Anderson IM. The effect of rate of antidepressant tapering on the incidence of discontinuation symptoms: a randomised study. J Psychopharmacol (2008) 22:330–2. 10.1177/0269881107081550 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J Psychopharmacol (2008) 22:330–2. 10.1177/0269881107081550 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

64. Olfson M, Shaffer D. SSRI prescriptions and the rate of suicide. Am J Psychiatry (2007) 164:1907–8. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07091467 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

65. Sheldon T. Dutch academics criticise suicide claims in American journal. BMJ (2008) 336:112. 10.1136/bmj.39458.561539.DB [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

66. Bachmann CJ, Aagaard L, Burcu M, Glaeske G, Kalverdijk LJ, Petersen I, et al. Trends and patterns of antidepressant use in children and adolescents from five western countries, 2005-2012. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol (2016) 26:411–9. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.02.001 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

67. Painter K. Warnings on antidepressants may have backfired. USA Today (2014). Available at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/06/18/antidepressant-suicide-warning/10767201/ [Accessed October 8, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

68. Stein R. Warnings against antidepressants For teens may have backfired. Natl Public Radio (2014). Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2014/06/18/323329892/warnings-against-antidepressants-for-teens-may-have-backfired [Accessed October 8, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

69. Dahlberg M, Lundin D. Antidepressants and the suicide rate: is there really a connection? Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res (2005) 16:121–41. 10.1016/S0731-2199(05)16006-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

70. Wheeler BW, Gunnell D, Metcalfe C, Stephens P, Martin RM. The population impact on incidence of suicide and non-fatal self harm of regulatory action against the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in under 18s in the United Kingdom: ecological study. BMJ (2008) 336:542–5. 10.1136/bmj.39462.375613.BE [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

71. Malchy B, Enns MW, Young TK, Cox BJ. Suicide among Manitoba’s aboriginal people, 1988 to 1994. CMAJ (1997) 156:1133–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CMAJ (1997) 156:1133–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Greenwood ML, de Leeuw SN. Social determinants of health and the future well-being of Aboriginal children in Canada. Paediatr Child Health (2012) 17:381–4. [Google Scholar]

73. Nelson SE, Wilson K. The mental health of Indigenous peoples in Canada: a critical review of research. Soc Sci Med (2017) 176:93–112. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.021 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

74. Gibbons RD. Dr. Gibbons replies. Am J Psychiatry (2007) 164:1908–10. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07091463r [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

75. Kafali N, Progovac A, Hou SS-Y, Cook BL. Long-run trends in antidepressant use among Youths After the FDA black box warning. Psychiatr Serv (2018) 69:389–95. 10.1176/appi.ps.201700089 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

76. Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, Barbe RP, Birmaher B, Pincus HA, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA (2007) 297:1683–96. 10.1001/jama.297.15.1683 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

JAMA (2007) 297:1683–96. 10.1001/jama.297.15.1683 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

77. Spielmans GI, Gerwig K. The efficacy of antidepressants on overall well-being and self-reported depression symptom severity in youth: A meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom (2014) 83:158–64. 10.1159/000356191 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

78. Valluri S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, Zuckerman IH, Mullins CD, Korelitz JJ. Impact of the 2004 Food and Drug Administration pediatric suicidality warning on antidepressant and psychotherapy treatment for new-onset depression. Med Care (2010) 48:947–54. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ef9d2b [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

79. Libby AM, Orton HD, Valuck RJ. Persisting decline in depression treatment after FDA warnings. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2009) 66:633–9. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.46 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

80. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics (2016) 138:e20161878. 10.1542/peds.2016-1878 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Pediatrics (2016) 138:e20161878. 10.1542/peds.2016-1878 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

81. Plöderl M, Hengartner MP. Antidepressant prescription rates and suicide attempt rates from 2004 to 2016 in a nationally representative sample of adolescents in the USA. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci (2019) 28:589–91. 10.1017/S2045796018000136 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

82. Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik S, Gay J, Brown C, Browning W, et al. Hospitalization for suicide ideation or attempt: 2008–2015. Pediatrics (2018) 141:e20172426. 10.1542/peds.2017-2426 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

83. Hall WD, Mant A, Mitchell PB, Rendle VA, Hickie IB, McManus P. Association between antidepressant prescribing and suicide in Australia, 1991-2000: trend analysis. BMJ (2003) 326:1008. 10.1136/bmj.326.7397.1008 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

84. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Shaffer D. Antidepressant drug therapy and suicide in severely depressed children and adults: A case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2006) 63:865–72. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.865 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Arch Gen Psychiatry (2006) 63:865–72. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.865 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

85. Barbui C, Esposito E, Cipriani A. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of suicide: a systematic review of observational studies. CMAJ (2009) 180:291–7. 10.1503/cmaj.081514 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

86. Silverman MM, De Leo D. Why there is a need for an international nomenclature and classification system for suicide. Crisis (2016), 37:83–7. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000419 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

87. Riddle MA, King RA, Hardin MT, Scahill L, Ort SI, Chappell P, et al. Behavioral side effects of fluoxetine in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol (1990) 1:193–8. 10.1089/cap.1990.1.193 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

88. Offidani E, Fava GA, Tomba E, Baldessarini RJ. Excessive mood elevation and behavioral activation with antidepressant treatment of juvenile depressive and anxiety disorders: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom (2013) 82:132–41. 10.1159/000345316 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Psychother Psychosom (2013) 82:132–41. 10.1159/000345316 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

89. Safer DJ, Zito JM. Treatment-emergent adverse events from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors by age group: children versus adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol (2006) 16:159–69. 10.1089/cap.2006.16.159 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

90. Reinblatt SP, dosReis S, Walkup JT, Riddle MA. Activation adverse events induced by the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluvoxamine in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol (2009) 19:119–26. 10.1089/cap.2008.040 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

91. Pompili M, Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ. Suicidal risk emerging during antidepressant treatment: recognition and intervention. Clin Neuropsychiatry (2005) 2:66–72. [Google Scholar]

92. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edition Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; (1988). [Google Scholar]

Antidepressants and the FDA’s Black-Box Warning: Determining a Rational Public Policy in the Absence of Sufficient Evidence | Journal of Ethics

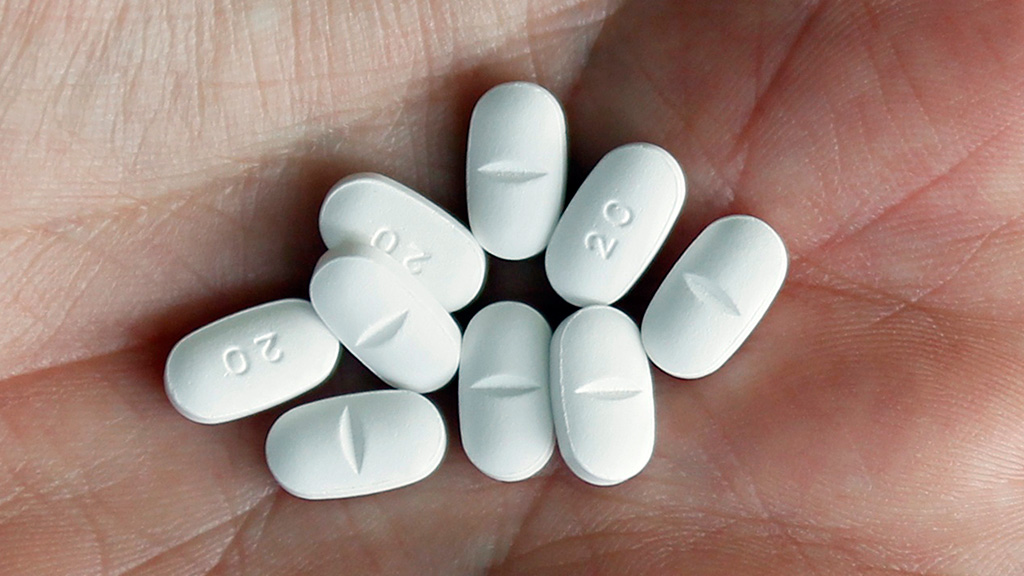

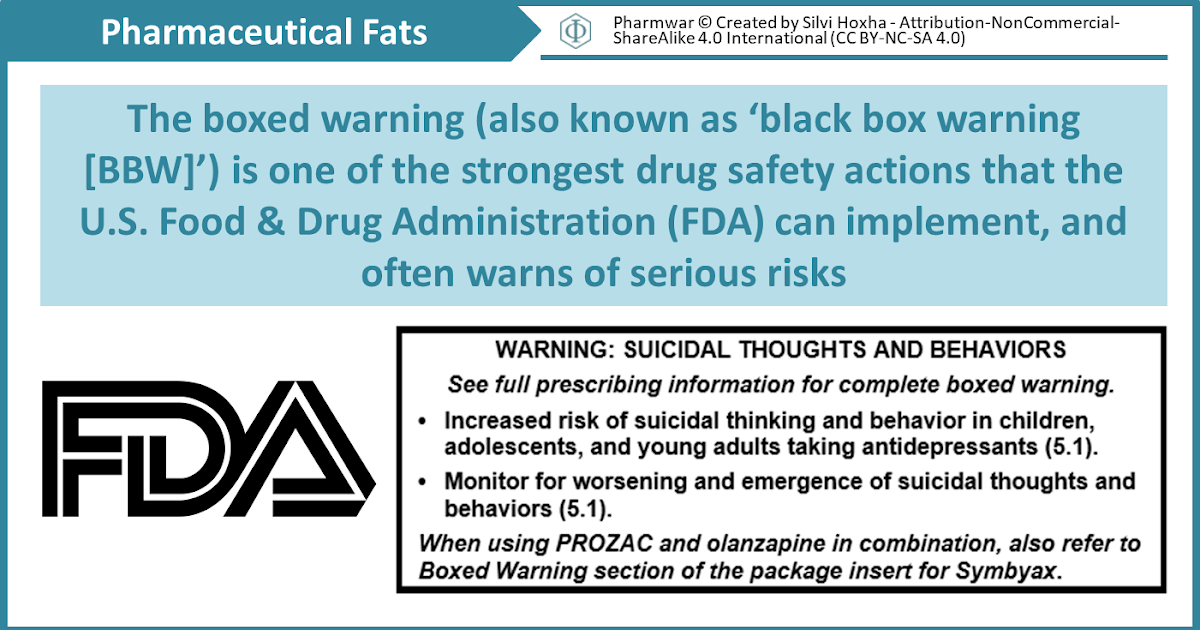

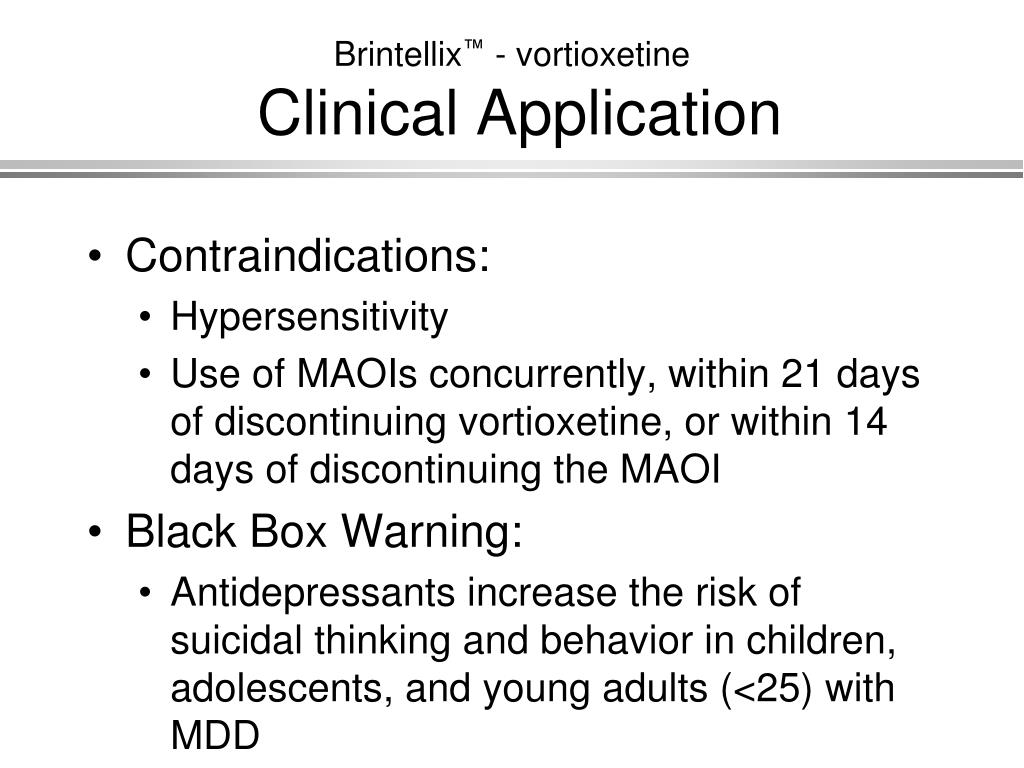

In October of 2004, the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) issued a “black-box” label warning indicating that the use of certain antidepressants to treat major depressive disorder (MDD) in adolescents may increase the risk of suicidal ideations and behaviors. The warning came shortly after the FDA’s British counterpart, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), concluded that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) with the exception of fluoxetine (Prozac) should not be used to treat adolescents with major depressive disorders.

The warning came shortly after the FDA’s British counterpart, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), concluded that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) with the exception of fluoxetine (Prozac) should not be used to treat adolescents with major depressive disorders.

The MHRA’s 2003 recommendation, based on a report by the Committee on Safety of Medicines’ Expert Working Group, states that, with the exception of fluoxetine, SSRIs have not been found efficacious in randomized clinical trials [1]. Moreover, the group also noticed an increased risk of suicidal behaviors among adolescent patients being treated with SSRIs and judged that the balance of risks and benefits did not favor the use of SSRIs for adolescents with MDD. Only fluoxetine showed significant therapeutic benefits; fluvoxamine (Luvox) lacked evidence to warrant any cost-benefit analysis.

The MHRA’s investigation into the safety of SSRIs in treating adolescents with major depressive disorder came about serendipitously. In evaluating GlaxoSmithKline’s application for approving the use of paroxetine (Paxil) to treat adolescents with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and social anxiety disorder, the MHRA requested all data including unpublished trials from GlaxoSmithKline. An examination of the data showed that rate of suicide attempts was higher among adolescent patients taking paroxetine for MDD than among the placebo-controlled group [2]. The MHRA then launched a broader investigation into the safety of SSRIs and requested all data from pharmaceutical companies. It was this meta-analysis of the newly discovered evidence that led the Expert Working Group to its recommendation [3]. In response to the MHRA’s recommendation, the FDA launched its own investigation to determine whether there was an increased risk for suicidality among pediatric patients with MDD being treated with SSRIs [4].

In evaluating GlaxoSmithKline’s application for approving the use of paroxetine (Paxil) to treat adolescents with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and social anxiety disorder, the MHRA requested all data including unpublished trials from GlaxoSmithKline. An examination of the data showed that rate of suicide attempts was higher among adolescent patients taking paroxetine for MDD than among the placebo-controlled group [2]. The MHRA then launched a broader investigation into the safety of SSRIs and requested all data from pharmaceutical companies. It was this meta-analysis of the newly discovered evidence that led the Expert Working Group to its recommendation [3]. In response to the MHRA’s recommendation, the FDA launched its own investigation to determine whether there was an increased risk for suicidality among pediatric patients with MDD being treated with SSRIs [4].

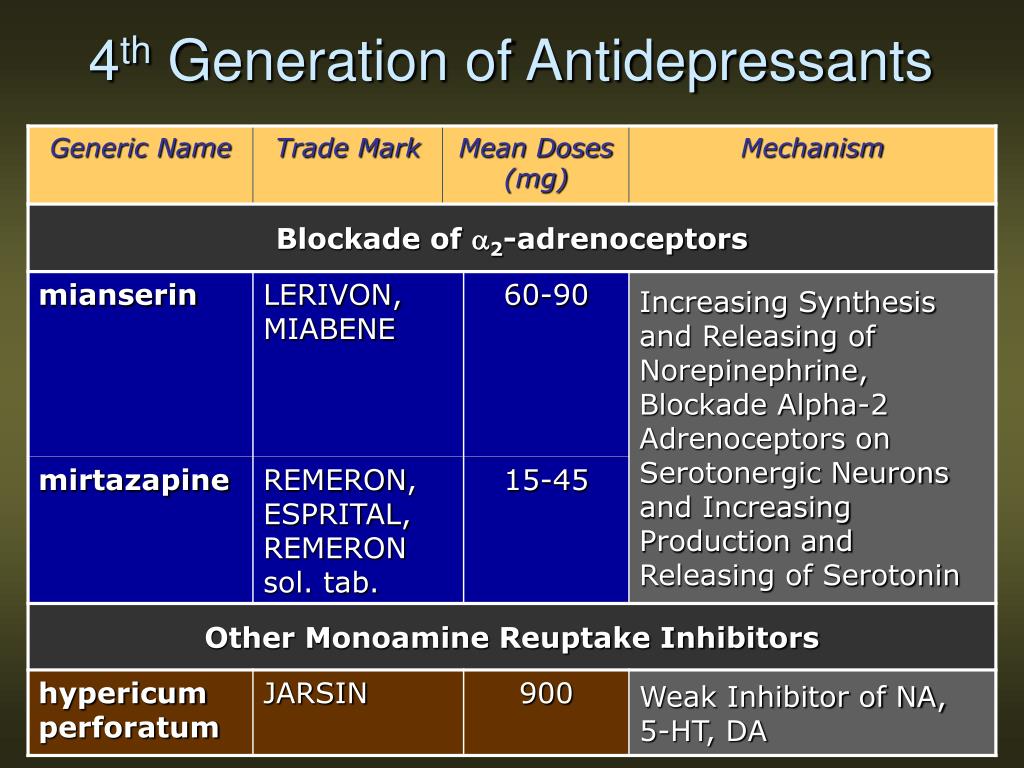

One significant difference between the FDA’s study and that of the MHRA was that the FDA conducted an independent reclassification of suicidality. Since the original trials did not explicitly study the connection between SSRIs and suicidal behaviors, the FDA was concerned that the data did not use consistent measurements of suicidality across trials. A group of 10 pediatric suicidologists organized by Columbia University led an independent and blind reclassification. The conclusion of this meta-analysis using the reclassified data was that the use of all antidepressants increased the risks of suicidality among pediatric patients with MDD [5]. As a result, the FDA issued a black-box warning for the nine antidepressants citalopram (Celexa), fluvoxamine (Luvox), paroxetine (Paxil), fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), venlafaxine (Effexor), mirtazapine (Remeron), nefazodone (Serzone), and bupropion (Wellbutrin).

Since the original trials did not explicitly study the connection between SSRIs and suicidal behaviors, the FDA was concerned that the data did not use consistent measurements of suicidality across trials. A group of 10 pediatric suicidologists organized by Columbia University led an independent and blind reclassification. The conclusion of this meta-analysis using the reclassified data was that the use of all antidepressants increased the risks of suicidality among pediatric patients with MDD [5]. As a result, the FDA issued a black-box warning for the nine antidepressants citalopram (Celexa), fluvoxamine (Luvox), paroxetine (Paxil), fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), venlafaxine (Effexor), mirtazapine (Remeron), nefazodone (Serzone), and bupropion (Wellbutrin).

The black box is the most severe warning the FDA can place on a drug short of an outright ban. The boldfaced text appears at the beginning of the package insert accompanying each prescription, warning that antidepressant usage for children and adolescents may increase the risk of suicidality. It also indicates that, with the exceptions of fluoxetine for MDD and OCD and sertraline and fluvoxamine for OCD, antidepressants are not approved for pediatric patients. Black-box warnings also prohibit the dissemination of “reminder ads” (i.e., advertisements that mention the drugs’ names but not their indications). Along with a black-box warning, a patient medication guide accompanies each prescription or refill for an antidepressant [6]. The guide warns that a child’s or adolescent’s suicide risk may increase as a result of taking antidepressants to treat MDD. In May 2006, the FDA expanded the warning to include 36 antidepressants and raised the age of potentially vulnerable patients from 18 to 24 [7].

It also indicates that, with the exceptions of fluoxetine for MDD and OCD and sertraline and fluvoxamine for OCD, antidepressants are not approved for pediatric patients. Black-box warnings also prohibit the dissemination of “reminder ads” (i.e., advertisements that mention the drugs’ names but not their indications). Along with a black-box warning, a patient medication guide accompanies each prescription or refill for an antidepressant [6]. The guide warns that a child’s or adolescent’s suicide risk may increase as a result of taking antidepressants to treat MDD. In May 2006, the FDA expanded the warning to include 36 antidepressants and raised the age of potentially vulnerable patients from 18 to 24 [7].

Evidence

The primary difficulty the FDA confronted was determining what public health policy to adopt in the absence of robust evidence; reliable and consistent data on the effects of antidepressants, especially with regards to suicidality, on pediatric patients with MDD were and continue to be scarce.

Although the FDA’s meta-analysis of data supplied by pharmaceutical manufacturers indicates that suicidality risk for the 9 antidepressants in MDD trials were 1.37 (citalopram) to 8.84 (extended-release venlafaxine) times higher than for the placebo, a number of other studies show different results [8]. In an ecologic study comparing suicide rates against antidepressant prescription rates at the county level in the United States, investigators found that higher antidepressant prescription rates correlated with lower suicide rates among children [9]. Another population-based study of suicide risk during the initial phase of antidepressant treatment for 65,103 patients (not restricted to children) did not show an elevated risk of suicide or suicide attempts that led to hospitalization [10]. More recently, a meta-analysis found that the use of fluoxetine to treat pediatric patients with MDD neither increased nor significantly decreased the risk of suicidality [11].

In addition to the unknown cost of increased suicidality risk, there is conflicting evidence about the efficacy of antidepressants in treating pediatric patients with major depressive disorder. The FDA approved fluoxetine for pediatric MDD treatment, and a number of studies offer supporting evidence [12, 13]. Nevertheless, a study on sertraline—a drug not approved by the FDA to treat pediatric depression—demonstrated that it outperformed placebos in a randomized clinical trial [14].

The FDA approved fluoxetine for pediatric MDD treatment, and a number of studies offer supporting evidence [12, 13]. Nevertheless, a study on sertraline—a drug not approved by the FDA to treat pediatric depression—demonstrated that it outperformed placebos in a randomized clinical trial [14].

With limited evidence, the FDA must determine if the therapeutic benefits of antidepressants for treating pediatric MDD outweigh the cost of an apparent elevated risk of suicidality. The dilemma is sharp: doing nothing could expose adolescents and children who are taking antidepressants to a heightened risk of suicidality for possibly meager therapeutic benefits, but premature warning on the danger of antidepressants could also discourage much needed treatment for patients with pediatric major depressive disorder.

Indeed, two recent studies identify some concerns with the FDA’s black-box warning on antidepressants. A main goal of instituting the label warning was to ensure greater supervision for pediatric patients during the initial stages of antidepressant treatment. In a postwarning study, investigators discovered that the frequency of contact between patients and clinicians did not increase [15].

In a postwarning study, investigators discovered that the frequency of contact between patients and clinicians did not increase [15].

More worrisome still is the possibility that the FDA’s warning might have led to an unforeseen decline in both depression diagnoses and treatments. In a 2009 study, investigators reported that between 2004 (the year of the emergence of the black-box warning) and 2007, there was a substantial decline in the number of MDD cases diagnosed nationwide, contrary to projections based on historic data [16]. The warning not only possibly affected pediatric cases but had a spillover effect on adult and geriatric cases as well.

The same study also noted that, while the use of antidepressants to treat major depressive disorder had decreased, there had been no corresponding increase in substitute treatments. Patients of all ages with MDD, it appears, are less likely to be diagnosed with the disease and are less likely to receive adequate treatments since the introduction of the black-box warning. Furthermore, a recent examination of teen suicide data from the National Center for Injury and Prevention and Control shows that, contrary to the downward trend prior to 2003, there was a significant increase in mortality due to teen suicide between 2003 and 2005 [17]. Although one cannot confidently draw a causal connection between the introduction of the black-box warning and the increase in teen suicides, the data raise serious concerns about unintended consequences of the FDA warning.

Furthermore, a recent examination of teen suicide data from the National Center for Injury and Prevention and Control shows that, contrary to the downward trend prior to 2003, there was a significant increase in mortality due to teen suicide between 2003 and 2005 [17]. Although one cannot confidently draw a causal connection between the introduction of the black-box warning and the increase in teen suicides, the data raise serious concerns about unintended consequences of the FDA warning.

Analysis

One can question the wisdom of the FDA’s decision to issue a black-box warning on the basis of limited evidence about both the risk of suicidality and the efficacy of antidepressants in treating MDD. The more substantive policy question is what a regulatory agency ought to do when a pressing policy decision must be made in the absence of quality evidence [18].

In his defense of theism, American philosopher William James argues in The Will to Believe that decisions do not always have to be made on the basis of evidence [19]. Indeed, under some circumstances, one would not be irrational to make decisions in the absence of supporting evidence. For James, the circumstances that justify making decisions not based on evidence must satisfy three conditions: they must be living, forced, and momentous. A living decision is one in which either choice or hypothesis contains some appeal, however small. A forced decision is a decision that cannot be avoided. James suggests that the imperative to “choose between going out with your umbrella or without it” is not a forced decision; one can simply avoid making a decision by not going out. A logically exhaustive disjunction such as “either be a theist or not” forces a decision. Finally, a momentous decision is one that entails a significant stake.

Indeed, under some circumstances, one would not be irrational to make decisions in the absence of supporting evidence. For James, the circumstances that justify making decisions not based on evidence must satisfy three conditions: they must be living, forced, and momentous. A living decision is one in which either choice or hypothesis contains some appeal, however small. A forced decision is a decision that cannot be avoided. James suggests that the imperative to “choose between going out with your umbrella or without it” is not a forced decision; one can simply avoid making a decision by not going out. A logically exhaustive disjunction such as “either be a theist or not” forces a decision. Finally, a momentous decision is one that entails a significant stake.

The dilemma confronting the FDA satisfied all three conditions. It was living in the sense that a wide range of cost-benefit results of prescribing antidepressants to pediatric patients with MDD were all plausible in light of a near-vacuum of evidence. According to James’s view of pragmatic reasoning, the lack of evidential support would mean that the belief for and the belief against the use of antidepressants to safely treat pediatric MDD patients were both equally rational. To warn or not to warn constitutes a logically exhaustive dilemma. Neither could the FDA have avoided the decision. Finally, the stakes riding on the decision were obviously high.

According to James’s view of pragmatic reasoning, the lack of evidential support would mean that the belief for and the belief against the use of antidepressants to safely treat pediatric MDD patients were both equally rational. To warn or not to warn constitutes a logically exhaustive dilemma. Neither could the FDA have avoided the decision. Finally, the stakes riding on the decision were obviously high.

The FDA faced a dilemma in which it was epistemically defensible to make a nonevidence-based decision. But was its decision morally defensible? By making a public recommendation, the FDA undermined the evidential-neutrality in the advisability of treating pediatric MDD with antidepressants. The warning now becomes, in itself, “evidence” even though the FDA’s decision was not evidence-based.

A morally preferable route might have been to present the lack of evidence plainly and to reiterate the rationality of either choice. Allowing individuals to make their own decisions demonstrates a respect for multiple rational options in a context of evidential scarcity.

- Clinical research/Vulnerable populations,

- Ethics/Practice,

- Mental health/Depression

References

-

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): overview of regulatory status and CSM advice relating to major depression disorder (MDD) in children and adolescents including summary of available safety and efficacy data. http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/Safetywarningsalertsandrecalls/Safetywarningsandmessagesformedicines/CON019494?useSecondary=&showpage=1. Accessed March 11, 2012.

-

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Committee on safety of Medicines assessment report. http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/es-policy/documents/websiteresources/con014159.pdf; 2003: 49. Accessed March 11, 2012.

- Emslie G, Kratochvil C, Vitiello B, et al. The Columbia Suicidality Classification Group, and the Tads Team. Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS): safety results.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(12):1440-1455.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(12):1440-1455. View Article PubMed

-

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency Committee on the Safety of Medicine. Report of the CSM expert working group on the safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants. http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/pl-p/documents/drugsafetymessage/con019472.pdf; 2004. Accessed March 11, 2012.

- Hammad TA, Laughren T, Racoosin J. Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(3):322-339.

View Article Google Scholar

-

Food and Drug Administration. Revisions to medication guide. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm100211.pdf; 2007. Accessed March 11, 2012.

-

Food and Drug Administration. Revisions to product labeling. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/UCM173233.pdf; 2007. Accessed March 11, 2012.

-

Hammad, Laughren, Racoosin, 337.

- Gibbons RD, Hur K, Bhaumik DK, Mann JJ. The relationship between antidepressant prescription rates and rate of early adolescent suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1898-1904.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Simon GE, Savarino J, Operskalski B, Wang PS. Suicide risk during antidepressant treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):41-47.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar

-

Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Davis JM, Mann JJ. Suicidal thoughts and behavior with antidepressant treatment: reanalysis of the randomized placebo-controlled studies of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012 Feb 9 [epub ahead of print].

View Article PubMed Google Scholar

- March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Treatment for Adolescents with Depressions Study (TADS) Team. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial.

JAMA. 2004;292(7):807-820.

JAMA. 2004;292(7):807-820. View Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;297(15):1683-1696.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Wagner KD, Ambrosini P, Rynn M, et al. Efficacy of sertraline in the treatment of children and adolescents with major depressive disorder: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2003;290(8):1033-1041.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Morrato EH, Libby AM, Orton HD, et al. Frequency of provider contact after FDA advisory on risk of pediatric suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(1):42-50.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Libby AM, Orton HD, Valuck RJ. Persisting decline in depression treatment after FDA warnings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(6):633-639.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Bridge JA, Greenhouse JB, Weldon AH, Campo JV, Kelleher KJ.

Suicide trends among youths aged 10 to 19 years in the United States, 1996-2005. JAMA. 2008;300(9):1025-1026.

Suicide trends among youths aged 10 to 19 years in the United States, 1996-2005. JAMA. 2008;300(9):1025-1026. View Article PubMed Google Scholar

-

The pressure from the public was immense for the FDA to act in light of the MHRA’s recommendations. The FDA held hearings that included passionate presentations by parents who believed their children’s suicides were related to SSRIs. Moreover, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that the FDA apparently prevented a member of the Columbia Group from speaking in public regarding the suicidality risks of SSRIs. As a result, congressional members summoned representatives to public hearings in order to determine if the FDA had acted inappropriately. Waters R. Drug report barred by FDA:scientist links antidepressants to suicides in kids. San Francisco Chronicle. February 1, 2004. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2004/02/01/MNGB64MJSP1.DTL&ao=all. Accessed March 11, 2012.

-

James W.

William James: Writings 1878-1899. New York: Library of America; 1992.

William James: Writings 1878-1899. New York: Library of America; 1992.Google Scholar

Black box warning 101: what it is and what it means for your medicines -

Drug InformationHome >> Product Information >> What is a black box warning?

Product Information

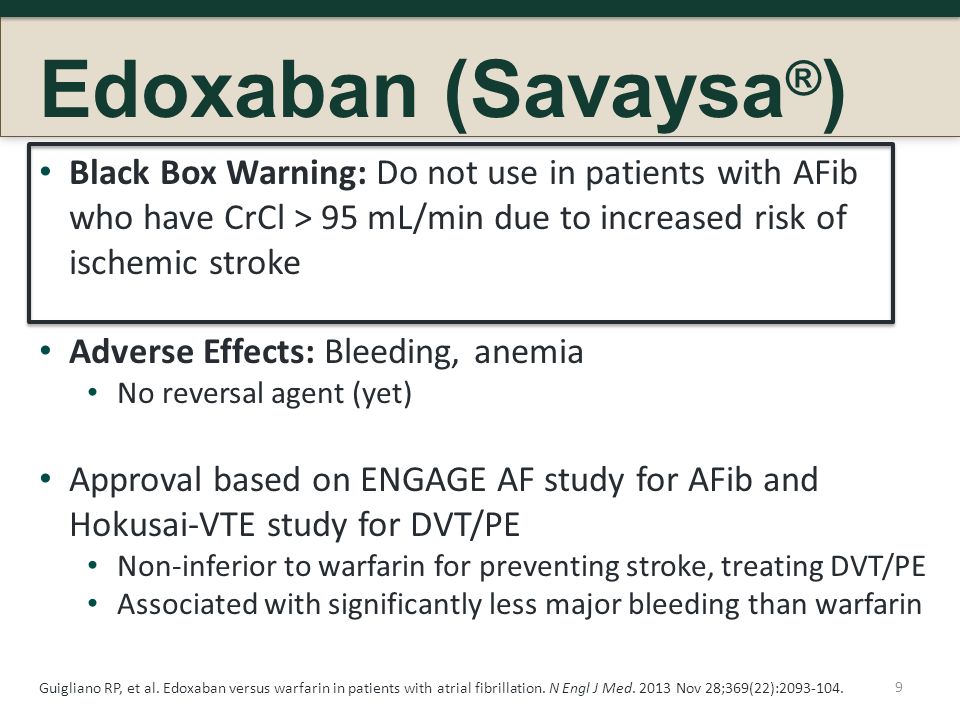

Not surprisingly, not all medicines are the same. While some drugs have minimal side effects, others have more serious side effects and a risk of side effects. If there are concerns about the safety of using a drug, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) applies warnings. The type of warnings on prescription drug labels depends on the type of side effects. The FDA's black box warning draws attention to drugs with more serious side effects, such as heart failure. A warning warns prescribers and patients that a medicine may have serious or life-threatening risks.

What is a black box warning?

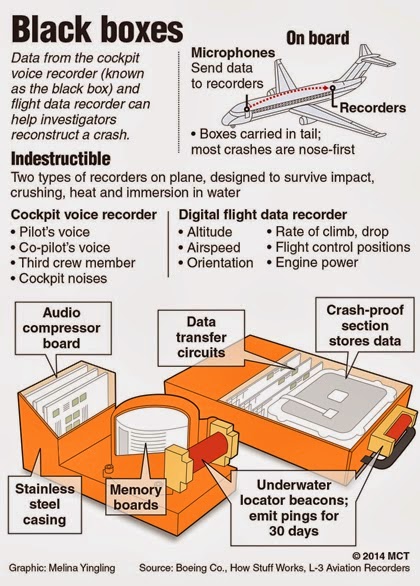

A black box or boxed warning is an FDA warning to alert consumers to serious or life-threatening side effects that a drug may cause. This is the strongest warning issued by the FDA on a prescription drug package insert.

This is the strongest warning issued by the FDA on a prescription drug package insert.

A drug receives a black box warning when it has a potentially serious adverse reaction that could result in hospitalization and death. The black box warning also explains why reactions may be worse in certain groups of people, such as pregnant women, children, or the elderly.

All drugs in the United States must be tested for FDA approval. During this testing, the drug may have side effects that require a black box warning before being placed on the market. Sometimes these clinical trials of new drugs fail to detect all side effects because testing is only done on a few thousand patients. Later, more serious side effects may be discovered when the drug has already been approved, when it is used in tens or hundreds of thousands of patients. When this happens, black box warnings may be added to the drug after it reaches the market.

When this happens, black box warnings may be added to the drug after it reaches the market.

Where can I find black box warnings?

While black box warnings will appear on the medicine bottle or package insert, the warning will also appear on the Patient Information Sheet that your pharmacy provides when filling out a prescription.

Which drugs have a black box warning?

More than 600 drugs have black box warnings, and 40% of people are taking at least one drug with a black box warning, says Rick Rail, MD, director of pharmacy at the hospital. Denton University Behavioral Health in Texas. Here are some of the most commonly prescribed medications with black box warnings listed in the medication guide.

Xanax, an anxiety medication, does not currently have a black box warning. However, this is somewhat controversial, and there are motions for all benzodiazepines to add warnings of serious withdrawal side effects when the medication is stopped.

What to do if your medicine has a black box warning

It is important to talk to your doctor or pharmacist about drug safety information before starting any new prescription. The decision to accept a prescription with an FDA black box warning should not be taken lightly and should be discussed with your healthcare provider. Talking to healthcare professionals is the best way to determine if the benefit of a drug outweighs the potential risk in these scenarios.

Rail says that, as with all drugs, there are benefits and costs. Talk to your pharmacist to help you decide if this medicine is right for you.

🎖▷ Why You Don't Have to Worry About Weight Gain with Lamictal

Psychology

3,656 2 minutes read

If you're worried that taking Lamictal (lamotrigine) might cause weight gain, there's good news. It probably won't affect your weight much. If anything, you're more likely to lose weight due to Lamictal than gain weight, but either way, the changes are likely to be pretty small.

The effect of Lamictal on weight has been little studied, and various clinical trials have found minimal effect. In fact, some researchers even considered the drug as a possible remedy for obesity and as a remedy for overeating. This information should be reassuring for people with bipolar disorder, as many of the medications used to treat this condition can cause weight gain.

Lamictal findings and weight gain or loss

Lamictal is an anticonvulsant drug that can be used to treat seizures such as epilepsy. It is also used as a mood stabilizer for bipolar disorder.

In the first clinical trials with the drug, 5 percent of adults with epilepsy lost weight while taking Lamictal, while 1 to 5 percent of patients with bipolar I disorder gained weight while taking the drug. The researchers do not disclose how much weight patients have gained or lost.

Meanwhile, a 2006 study comparing the effects on weight of Lamictal, lithium, and placebo found that some Lamictal-treated patients gained weight, some lost weight, and most remained about the same weight. Weight changes are usually not many pounds anyway. Obese patients taking Lamictal lost an average of four pounds, while the weight of non-obese patients remained virtually unchanged.

Weight changes are usually not many pounds anyway. Obese patients taking Lamictal lost an average of four pounds, while the weight of non-obese patients remained virtually unchanged.

Relationship between weight gain and other bipolar drugs

Weight gain from medications used to treat bipolar disorder is unfortunately quite common. Some mood stabilizers commonly used for bipolar disorder, especially lithium and Depakote (valproate), carry a high risk of weight gain.

In addition, the atypical antipsychotics Clozaril (clozapine) and Zyprexa (olanzapine) tend to cause significant weight gain in people who take them. Finally, some antidepressants, notably Paxil (paroxetine) and Remeron (mirtazapine), have been associated with weight gain.

Therefore, if you are already overweight, you and your psychiatrist may want to consider additional weight gain when determining your bipolar medication regimen. Based on this, Lamictal may be a good choice.

Lamictal as a possible treatment for obesity

Lamictal has also been studied as a possible treatment for obesity in people without epilepsy or bipolar disorder.

In a small 40-person clinical trial conducted in 2006, researchers randomly assigned participants to receive either lamictal or placebo for up to 26 weeks. Each participant in the study had a body mass index (BMI) between 30 and 40, placing them in the obese group to the level of severe obesity. Those who took Lamictal lost an average of just over 10 pounds. Those who took the placebo lost about 7 pounds in the meantime, so while those who took Lamictal lost more weight, they didn't lose all that much more.

Another study in 2009 looked at Lamictal as a remedy for overeating. This study involved 51 people with the condition that 26 of them received Lamictal, and 25 - placebo.

Those who took Lamictal lost more weight than those who took placebo (about 2.5 pounds versus about one-third of a pound) and did have significant improvements in blood sugar and cholesterol lab test results. However, Lamictal did not appear to affect other aspects of the eating disorder when compared to placebo.