What are the psychological effects of music

The Psychology of Music

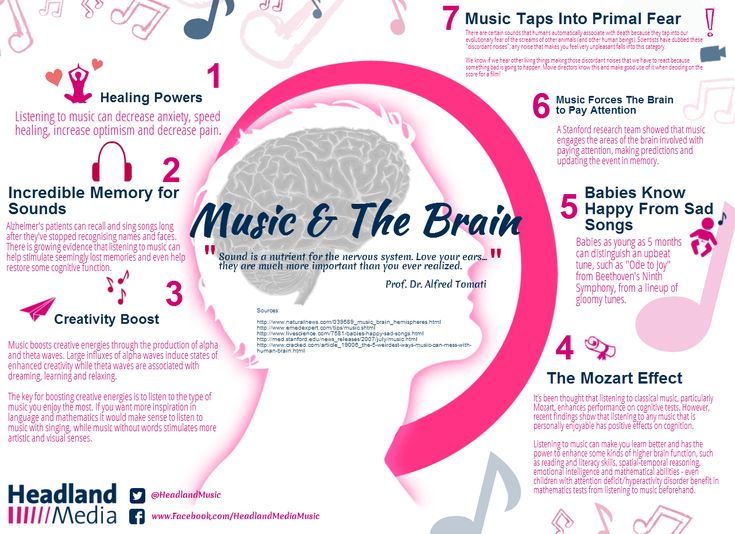

For years, researchers have studied the effects of sound on the human brain. Specifically, people have tried to understand why certain sounds alter someone’s mood, physical sensations, and even memory.

The most common example of this phenomenon is music. It’s a form of art and tradition inherent to every known culture on Earth, and in some cases music (particularly the use of chants, horns, and drums) predates organized language.

The human brain attunes to sound in the womb somewhere between 16 and 18 weeks. And a newborn’s sense of hearing develops faster than other senses, even extending to tuning out or “unlistening” to specific sounds. This suggests that humans have a predilection for sound, with certain parts of our brain prioritizing audio-triggered responses.

All of these findings have led to a heightened focus on understanding our obsession with sound, both as a component of modern cultures and also as a key piece of brain development. And this particular field of neuroscience — often grouped with psychoacoustics — has led to changes in both administered therapy and everyday self-care.

To fully appreciate the psychology of music, you can break the topic down into three key categories: how our brains process sound, how music affects the brain, and how music therapy can be used to improve anyone’s life.

How Our Brains Process Sound

Music is a powerful and often emotional experience for many people, yet so few of us fully appreciate how specific sounds affect our mood. But before we explore the physiology of music’s effect on the brain, it’s important to understand how our bodies interact with sound as a whole.

Put simply, our body perceives sound as vibrations and translates those signals to electric pulses. While that might not seem particularly “simple” — in fact it is one of the more complex things our bodies do each day — scientists have unraveled the principle stages of how sound moves from the source to the brain.

A Quick Look At Sound Waves

Everyone is familiar with the concept of sound waves, but sound can also travel as a set of pulses; these are the two primary patterns that sounds take as they travel. When these pressure variations travel through a specific material (usually air), they push and compress the molecules in their path and take a very specific shape.

Those pulses spread as they travel, growing wider and taller with time. As this cone expands, the pressure weakens and the sound becomes diluted or less powerful, which affects how clearly we are able to hear them. But that original “shape” remains.

With this mental image, it’s easy to see how “sound” quickly becomes “noise.” Crowded streets are full of competing pulses, while a single sound travels differently through air as compared to another medium like water or rock.

Music is an even more complicated set of audio signals because it can consist of sounds from multiple sources, at multiple frequencies, and sometimes even from multiple directions. And the way sound travels becomes even more complex when we think about hearing range, sound diffusion, and how different sources create different sound wave shapes.

And the way sound travels becomes even more complex when we think about hearing range, sound diffusion, and how different sources create different sound wave shapes.

The Power Of The Human Ear

“Hearing” truly begins when sound waves pass through the ear canal and reach the eardrum. Our bodies receive and process sound in three different stages: the signal of a specific sound travels into the outer ear (eardrum), is transcribed by the middle ear (ossicles), and is broadcast to the inner ear (cochlea) where it passes on to the brain.

Once sound waves reach the eardrum, a delicate set of organs and bones get to work. These pieces function similarly to a stopwatch or even a computer hard drive, with a dozen different minuscule components working in tandem over the course of a microsecond.

As each sound wave reaches the outer ear, it causes the eardrum to vibrate like a strummed rubber band. This movement shifts then three tiny bones — the smallest in the human body, in fact — which amplifies those vibrations as they pass on to the cochlea.

The cochlea, which has a shape similar to a nautilus shell, is lined with tiny hairs. And as the sound vibrations reach different sections of the cochlea, these hairs — called stereocilia — move up and town. That, in turn, opens up pores that release neurotransmitters into a nerve connecting the cochlea to the brain.

Finally, those chemicals travel along the auditory nerve and are received, processed, and recognized by the brain as specific sounds. All of that happens at near-instantaneous speeds every millisecond of every day, regardless of whether we are awake or asleep.

This video from the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communications Disorders animates the entire process from start to finish:

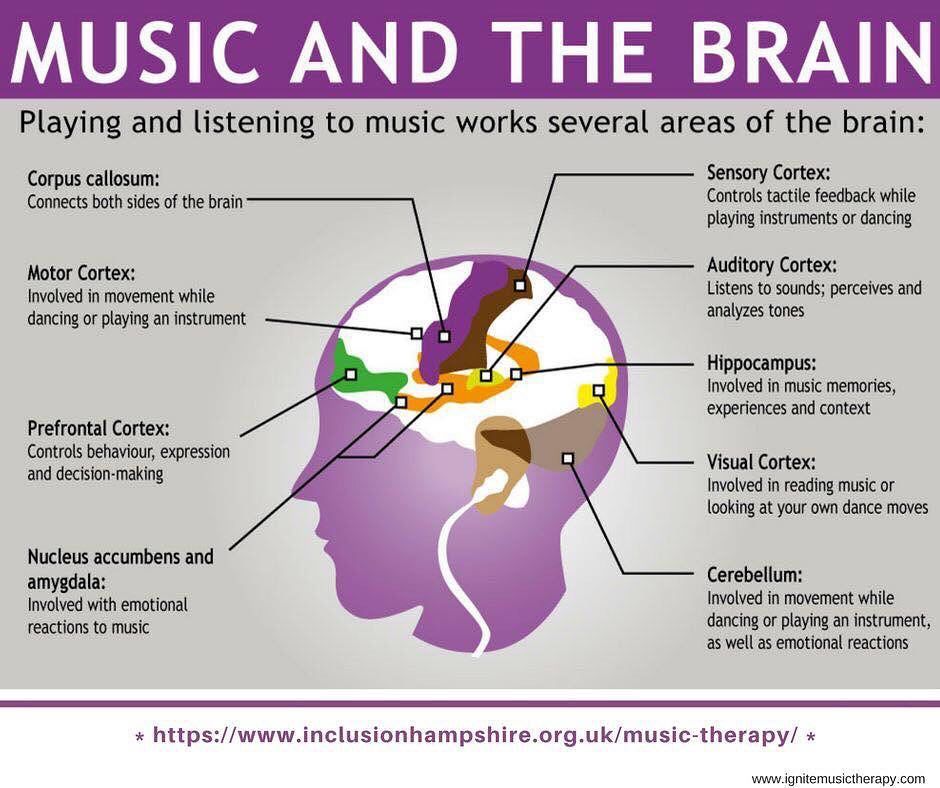

Sound signals affect many sections of the brain, but each area reacts differently based on how the brain categorizes the auditory signal. Music in particular takes full advantage of that process by generating a wide variety of mental, emotional, and physical reactions. And it is that variety that makes the psychology of music a focal point for many scientific studies.

How Our Brains Respond To Music

Multiple sound sources often create “noise” that muddy our brain’s ability to single out and process specific sounds. That is especially true with sounds at varying decibels and wavelengths, similar to the illustration of a busy city street.

Music, however, is both a simple sound and a complex amalgamation of different sounds. Yet — when properly arranged — the human brain is able to receive that signal and then separate the individual instruments and vocals. It can also recognize specific music chords or notes, understand multiple sets of lyrics, and physically react to the beat, all at the same time.

It can also recognize specific music chords or notes, understand multiple sets of lyrics, and physically react to the beat, all at the same time.

Those levels of complexity add to the artfulness of music and how songs are composed and arranged to generate emotions and pleasure. But before we can explore the art of music and the different ways it can be used to improve our lives, we need to understand the many ways that music interacts with our brains.

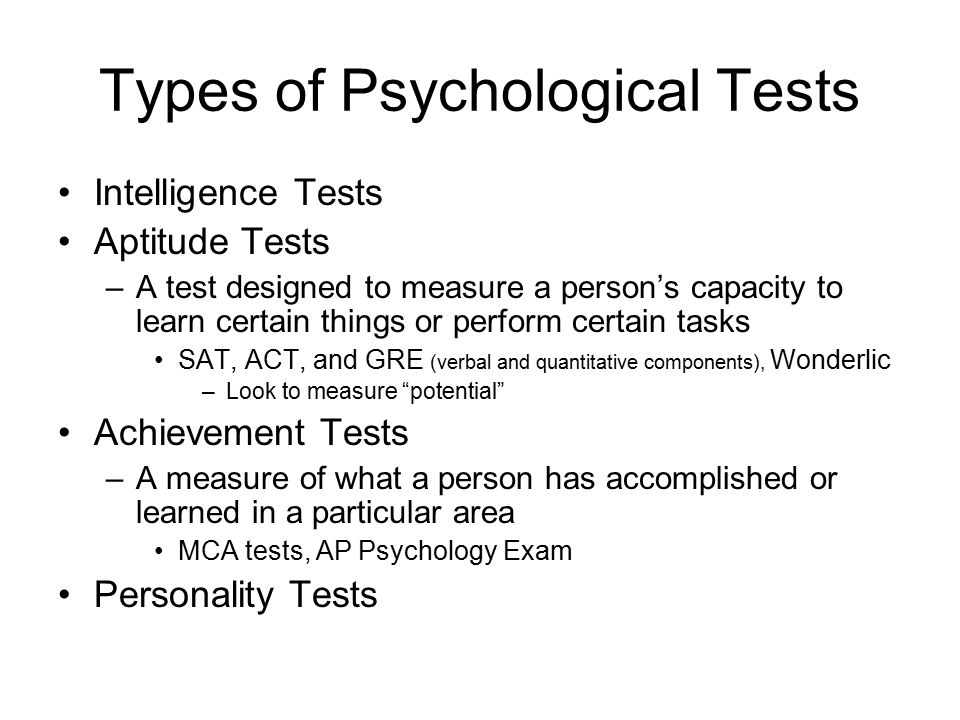

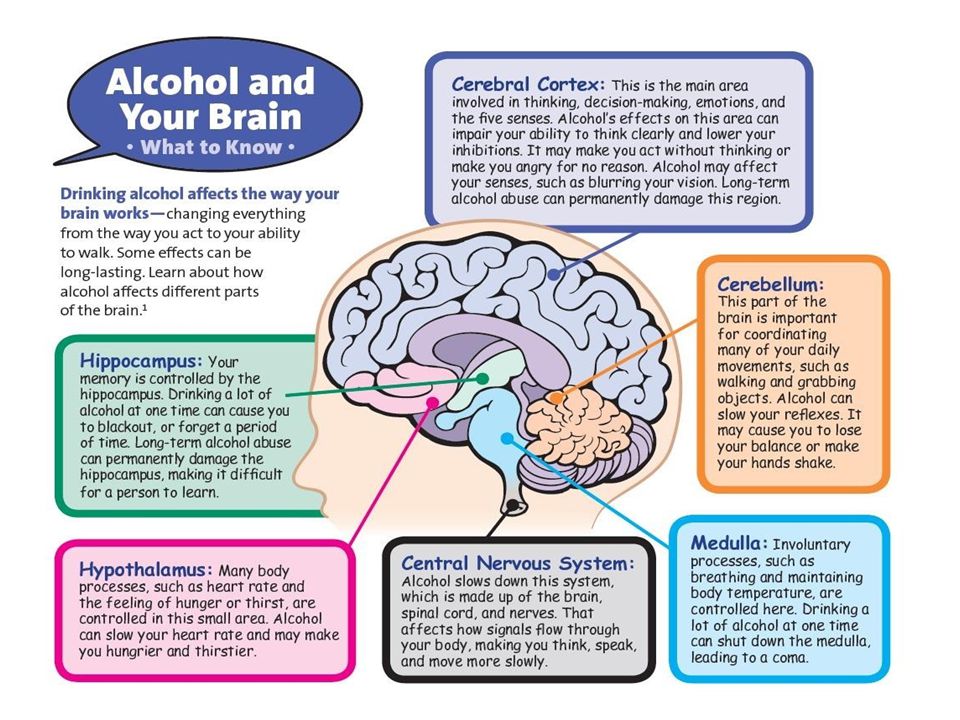

Scientists have singled out a dozen different areas of the brain that respond to music, but five regions have the most significant impact on the listener. They are the:

- Temporal lobe

- Amygdala

- Frontal lobe

- Cerebellum

- Hippocampus

We’ll look at each of these separately to see how sound (and specifically music) can affect the brain’s natural physiological purpose.

How Music Affects The Temporal Lobe

The temporal lobe serves a variety of roles, and one of them is language comprehension. This plays an important part in how we hear and react to the world around us, particularly in regards to conversation.

This plays an important part in how we hear and react to the world around us, particularly in regards to conversation.

As our brain’s language center, the temporal lobe allows us to understand song lyrics. The temporal lobe is constantly engaged when we listen to music — even songs without lyrics.

The temporal lobe functions as the processing center for music, but two of its subregions allow us to further enjoy what we hear. Wernicke’s area is the part of the brain that analyzes and comprehends what we hear, turning the words of a song into specific phrases and stories.

Meanwhile, Broca’s area gives us the ability to form our words ourselves so we can sing along with the music or discuss what we are hearing.

How Music Affects The Amygdala

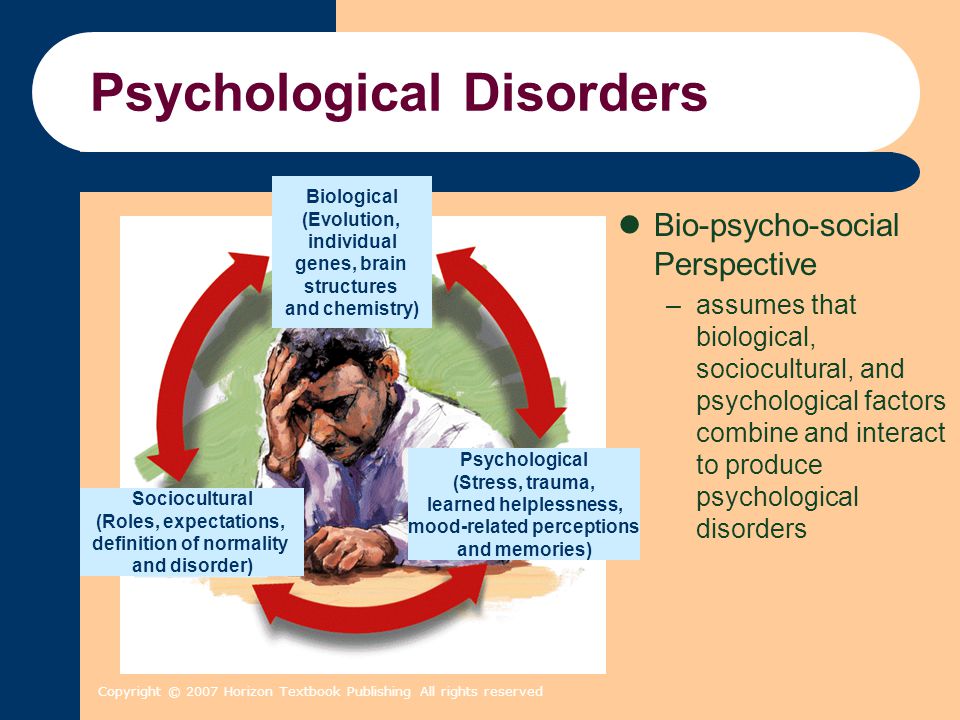

While the amygdala is tucked within the temporal lobe, it serves a purpose that makes it stand apart. The amygdala is the emotional switchboard of the brain, managing both negative emotions (fear or displeasure) as well as positive emotions (enthusiasm or tranquility).

The amygdala ties into the “fight or flight” instinct of the brain; it is the part of the brain that processes sounds and determines our emotional reactions to them. So while the amygdala can alert someone to an approaching ambulance or an angry dog, it is also the part that makes us smile when we hear a familiar voice or the calming songs of rainfall.

The amygdala’s connection to music is an obvious one, and studies show that responses to certain music genres are almost universal. Music can trigger those same emotional cues as the sounds mentioned above: a horror film soundtrack elicits an almost primal fear, while a soaring battle march can create a surge of excitement.

Similarly, meditation music can soothe the mind and body to produce a calming effect. And a plucky pop song can force an easy smile, regardless of the listener’s previous mood. All of these physiological responses to music stem from the amygdala.

How Music Affects The Frontal Lobe

The frontal lobe, on the other hand, is where we do our thinking, planning, and reasoning. While neurologists have yet to fully understand how music affects the frontal lobe, we do know that our interests and opinions about music — and specifically our tastes in genres and songs — stem from frontal lobe activity.

While neurologists have yet to fully understand how music affects the frontal lobe, we do know that our interests and opinions about music — and specifically our tastes in genres and songs — stem from frontal lobe activity.

Research shows that the frontal lobe functions as a hub for how we respond to certain music. Those specifics continue to be the focus of much study, but this area of the brain is a frequent focus for music therapists.

How Music Affects The Cerebellum

A normal byproduct to music is movement, and that is tied directly to the cerebellum. Whether that means tapping a foot, dancing a jig, or strumming an air guitar, the cerebellum is the part of the brain that triggers and coordinates movement in response to (or in time with) music.

Playing instruments also relies entirely on this part of the brain. Studies have shown that even a few weeks of piano lessons can alter the cerebellum. In fact, those functional changes aren’t restricted to playing music — listening to music or even imagining playing the piano can have the same effect.

The cerebellum also manages muscle memory. While a person’s cognitive abilities and long-term memory can fade over time, the cerebellum — as a separate part of the brain — ages differently. This has led to stories of coma victims reacting to music, Alzheimer’s patients playing instruments, and stroke victims finding their voice through song. As a result, the cerebellum is particularly valuable for many forms of music therapy.

How Music Affects The Hippocampus

Listening to music does not only have a transient effect on the brain; research shows that hearing or playing music alters both brain structure and brain function, particularly in situations where the same music is played frequently. This is because the hippocampus serves as a total contrast to the cerebellum.

As the brain’s memory center, the hippocampus is in charge of storing information. It also regulates emotional responses to certain things, which can be tied to memories associated with similar triggers.

Multiple scientific studies on the hippocampus have shown a strong tie between music listening, long-term memory, and short-term memory. The repetitive nature of music, with its motifs and phrases, activates short-term memory while simultaneously building long-term memories. That’s why people can remember a song they heard on the radio the previous day, but then 30 years later they also remember the outfit they wore and who else was in the car when they heard that song.

This effect can vary based upon the type of music being played. And that gives further credit to the idea that music can be a powerfully influential force on brain function. Music can be written to target different brain regions, which in turn elicit different reactions from the listener. While that allows musicians and composers to create truly moving pieces of music, it is proof that music can be a valuable tool for healthcare providers.

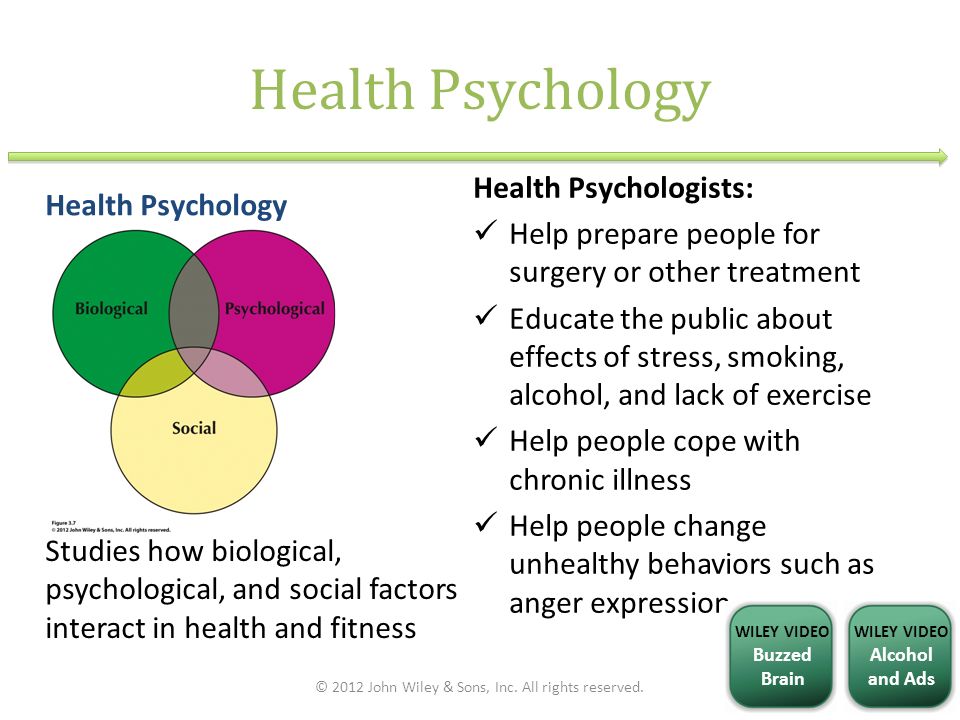

Music As A Therapy Tool

New studies continue to showcase music’s effects on the brain. As a result, music therapy has become an increasingly valuable tool for helping patients with all sorts of injuries and negative life experiences. While trauma of any sort can lead to different types of brain atrophy, we now know that music can have the opposite effect; it may not fully repair damaged brain tissue, but music therapy can help create new pathways to compensate for that loss.

As a result, music therapy has become an increasingly valuable tool for helping patients with all sorts of injuries and negative life experiences. While trauma of any sort can lead to different types of brain atrophy, we now know that music can have the opposite effect; it may not fully repair damaged brain tissue, but music therapy can help create new pathways to compensate for that loss.

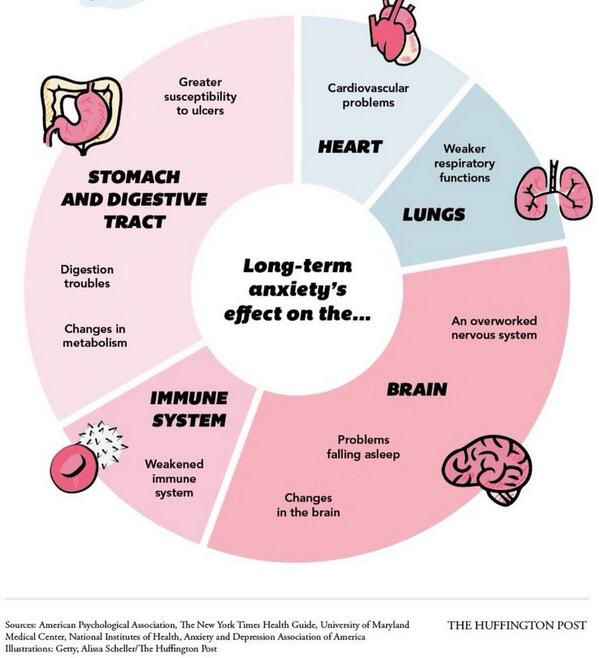

A 2018 study proved that changes in brain function (caused by listening to music) activates specific areas of the brain, which can promote healing. And that healing can take a variety of forms, such as reduced depression, improved abstract thinking, heightened motivation, etc.

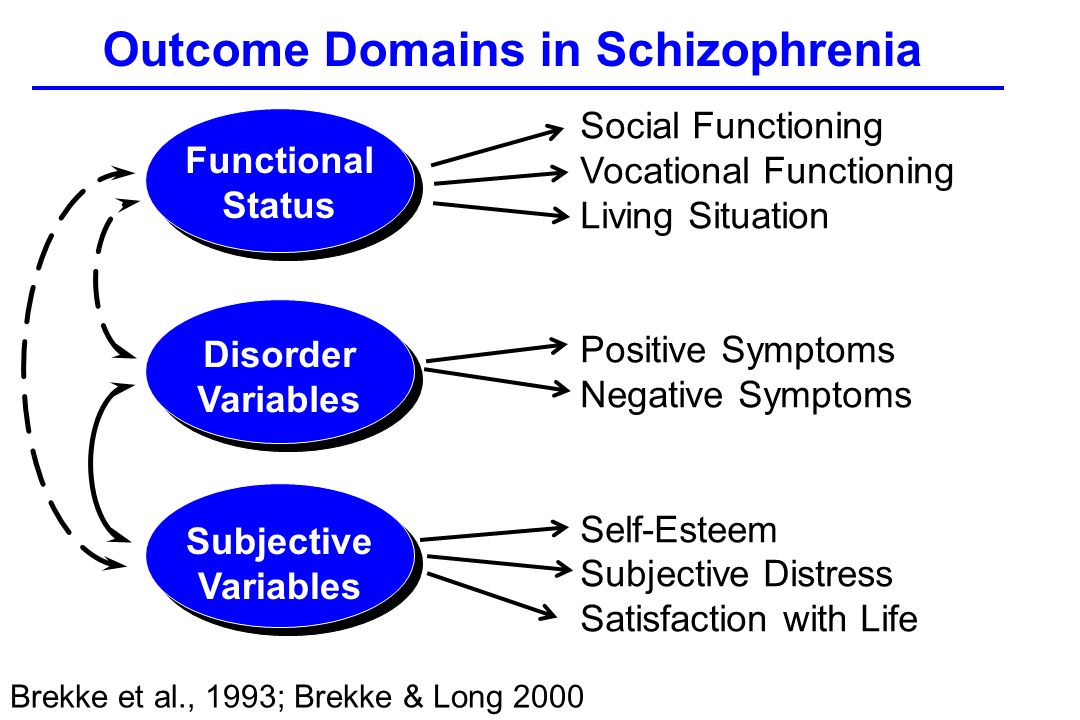

That study went on to suggest that music therapy could be used to deal with anything from “subjective distress experience in chronic pain syndromes, to the reward circuitry involved in addictive disorders, to the psychomotor pathways involved in Parkinson’s disease, and even to the functional connectivity changes that occur in autism spectrum disorders. ”

”

That is not to say that music is some sort of mystical cure-all for every ailment. But there is evidence that implementation of music therapy can succeed as a means of giving people strength as they undergo surgery, chemotherapy, and other complicated treatment regimens.

These outcomes can provide encouraging results for many people, but future studies will be required to show the lasting effects of music therapy. Creating new pathways through the brain could circumvent damaged tissue, thereby restoring previously lost functions. So while music therapy may never provide a path to reverting neurological disorders, there are still obvious benefits from incorporating music into a patient’s therapeutic habits.

The History Of Music Therapy

Music therapy dates back all the way to Ancient Greece — specifically the writings of Plato and Aristotle — and there are earlier records of music being used in ritualistic healings around the world. However, the first scientific papers on the topic began to appear in the late 1700s.

The earliest modern implementations of music therapy were immediately following World War II. Musicians would perform for hospitalized veterans as a means to raise their spirits and help them deal with psychological trauma that they carried home from those battlefields. But the benefits of these performances were so significant that doctors began to study the impact of music on mental health.

Over the next few decades, this research led many therapists to dedicate their whole careers to studying the psychology of music. Some of the music therapy pioneers were Isa Maud Ilsen (founder of the National Association of Music in Hospitals), Harriet Ayer Seymour (founder of the National Foundation of Music Therapy), E. Thayer Gaston (considered the “father of music therapy”), and Ira Altshuler, whose efforts led to the first collegiate music therapy training program.

All of those individual efforts culminated in the founding of the American Music Therapy Association in 1998. This association is an advocate for promoting music therapy across the government and academia, and it eventually grew to become the main hub for music therapy research, education, and resources throughout the United States and more than 30 other countries.

Popular Uses For Music Therapy

Music therapy can deliver a wide range of positive results, including but not limited to self-discovery, self-expression, and self-healing. But music can also bring a sense of community through performances both in-person and remote. Patients are able to practice this form of therapy long after they’ve completed their prescribed care regimen.

While music therapy is most effective when paired with other practices — like exercise, counseling, and social support — it can be used independently without sacrificing results. Popular implementations of music therapy include:

- Reducing anxiety and improving the mood of most patients

- Boosting healing through the release of specific hormones

- Improving the cognitive functions of patients with Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease

- Reducing depression and loneliness for elderly patients

- Improving psychiatric symptoms of mental illnesses like schizophrenia

- Supporting rehabilitation for patients with physical disabilities

- Building communication skills for children with developmental delays

At the core of these practices is a singular fact: Music’s ability to alter brain function provides therapists with a valuable and repeatable tool. The ability to improve a patient’s mood and create a calm environment — regardless of the patient’s health — has helped integrate music therapy into most mental health providers. It also solidifies the importance of music in our culture.

The ability to improve a patient’s mood and create a calm environment — regardless of the patient’s health — has helped integrate music therapy into most mental health providers. It also solidifies the importance of music in our culture.

Music can be used as a form of natural therapy for many different diseases, even showing benefits for those with severe physical or cognitive impairments regardless of age or mental health status. Recently, the University of Miami Health System implemented a music therapy program as part of their cancer treatment practice.

The goal of this is to use all sides of music — writing, listening, playing, and singing — to activate different parts of the brain in whatever way each patient prefers.

Because of that flexibility, patients have been able to find comfort and strength through music therapy even during COVID-induced quarantine. And as further study is done on the topic of the psychology of music, it is safe to assume that we will see new ways to implement music into therapy regimens. As a result, music therapy will only grow in importance.

As a result, music therapy will only grow in importance.

Understanding The Psychology Of Music

The psychology of music really comes down to how the brain processes sound, how music affects different parts of the brain, and how music therapy can be implemented. But perhaps the most significant and universal outcome of music therapy is that, at its core, music brings joy.

Listening to music triggers the same pleasure centers as eating a favorite food, exercising, or even having sex. This is a core reason behind why music therapy has become such a widespread inclusion from many mental health practices. And that remains true even in spite of a global pandemic; in fact, mandated quarantine made music even more important.

For many people, listening to music provided a way to manage global increases in anxiety, loneliness, and depression. So whether it is a means of reducing the effects of epilepsy, relieving the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, or even learning a new language, music has the power to improve a person’s life. And understanding how that can be implemented into mental health routines makes it a topic worth studying, understanding, and practicing.

And understanding how that can be implemented into mental health routines makes it a topic worth studying, understanding, and practicing.

The Psychological Effects Of Music On The Brain

Music’s powerful and enduring impact on our emotions, memories, and mental health cannot be understated.

You only need to refer to countless examples of people with dementia recalling their favourite songs to realise how effective music can be.

There are also plenty of examples from within the academic and professional world of music’s ability to trigger various psychological and physiological responses.

To explore all of these examples in more detail, we speak to Professor Jane Ginsborg of the Royal Northern College of Music.

Jane specialises in music psychology – she has a PhD in psychology and is a singer with a degree in music from the University of York. She has written various papers on singers’ memorising strategies, one of which won the British Voice Association’s Van Lawrence Award, and has been shortlisted for the Times Higher Education Best Research Project award.

As someone who holds the rare distinction of being both a musician and psychologist, Jane is perfectly placed to explain the psychological effects of music on the brain.

Here’s what she had to say.

Which areas of the brain perform the most crucial functions in eliciting certain emotional responses from music?

I should say up front that I’m a psychologist, not a neuroscientist. Therefore my understanding of the brain’s functions is not what you would call advanced, but it’s sufficient to teach undergraduate students what they need to know.

The temporal lobe is crucial in eliciting emotional responses from music because it processes what we hear across both the left and right hemispheres of the brain. Words are processed in the left hemisphere and music in the right hemisphere.

But whether or not we’re listening to songs with lyrics – and it’s often the lyrics that elicit the emotional response as much as the melody and harmony – we’re using both hemispheres. I want to drive this point home.

I want to drive this point home.

People often talk about right brain and left brain, but that is a metaphor. When we’re talking about neuroscience, we’re referring to the right and left hemispheres of the brain and we work across both of those hemispheres. That’s a crucial point to make.

The nucleus accumbens is very important, too, as it releases dopamine, the chemical that makes us feel good. The effect of music is to increase the amount of dopamine this part of the brain releases, and this dopamine hit makes you feel as though you’re profiting from listening to music.

When we hear music, the amygdala may be activated. In this instance, we’ll experience physiological responses such as a cold sweat, goosebumps, or the hairs standing up on the back of our neck.

I can provide a personal example here – I watched The Metropolitan Opera Centennial Gala, a televised concert that went out to millions of people across the world in 1983, and Kiri Te Kanawa was performing Dove sono from The Marriage of Figaro by Mozart.

I was learning the piece myself at the time, and Kiri Te Kanawa would likely have performed it a thousand times. And yet, she made a mistake, and it triggered a physiological response within me. The hairs on the back of my neck stood up – I knew she’d gone wrong, and it was as though I had gone wrong. I experience the same response whether I’m watching someone make a mistake or making a mistake myself whilst performing. I also get the same response if I hear something I find wonderful.

When we experience responses like this, we interpret it as an emotion. We may label it anticipation or fear, but it’s all the same thing – a form of arousal. This is a psychology-centric word for excitement.

When I teach my students about music performance anxiety, I borrow a technique I learned from a colleague who asked a group of students to write down on a piece of paper the way they felt the last time they fell in love. I say: ‘Imagine you’ve just fallen in love with somebody, and you know you’re about to meet them. Write down what it feels like.’ Then, about half an hour later, I ask them: ‘What do you feel like when you’re just about to go on stage for an important concert? Write it down and don’t tell anybody.’ Then, I ask them to compare their notes to what they wrote half an hour ago about their beloved, and they invariably say that they wrote down the same things.

Write down what it feels like.’ Then, about half an hour later, I ask them: ‘What do you feel like when you’re just about to go on stage for an important concert? Write it down and don’t tell anybody.’ Then, I ask them to compare their notes to what they wrote half an hour ago about their beloved, and they invariably say that they wrote down the same things.

I show them a Gary Larson cartoon of an elephant sitting at a grand piano on stage, and the thought bubble says ‘What am I doing here? I can’t play this thing! I’m a flutist, for crying-out loud!’ The body only has one way of being excited, and this excitement comes from the activation of the amygdala. We call this excitement stage fright or anticipation.

There are many examples of patients with Alzheimer’s disease recalling their favourite songs and responding positively to music, as the key areas of the brain which are linked to musical memory, such as the cerebellum, are relatively undamaged by the disease. Can you outline what role the cerebellum plays in processing music and just how powerful it can be?

The cerebellum is the area of the brain in which our procedural memories are stored. That is, memories of things that we find very difficult to do when we’re little, like tying shoelaces or learning to ride a bicycle. You can’t tell anyone how you do it because it’s hard to put into words.

That is, memories of things that we find very difficult to do when we’re little, like tying shoelaces or learning to ride a bicycle. You can’t tell anyone how you do it because it’s hard to put into words.

This kind of memory is not rooted in language – rather, it’s stored in the muscles we use to perform these tasks. So, once we’ve learned how to tie a shoelace or ride a bicycle, we never forget how to do it.

You can apply this principle to learning how to play an instrument. This process involves endless repetitions of the same movements – if, for example, you’re learning to play the guitar, you’re playing the same chord formations over and over again, or if you’re learning the violin, you’re practising the same scales until they become second nature to you.

Those repetitions strengthen the connections along the neural pathways that run between the synapses in the brain. Synapses are like junction boxes – think of the electric wiring inside these boxes. Procedural memories are stored in the cerebellum’s neural pathways in the same way that wiring is stored in a junction box.

Music-making is very often preserved in people who have Alzheimer’s. I spoke at a conference on music and dementia, and I bookended it by talking about my mother’s youngest cousin. This woman was in a different generation to me but not very much older than me, and she developed Lewy body dementia when she was only in her mid-70s. She was the kin keeper of the family – she knew who everybody was, when their children were born, when they got married, and when their bar mitzvahs were. She kept everybody together. And so, to lose her memory was horrendous.

But she loved music – she had played the piano as a girl and young woman, and her son has gone on to become a very talented opera singer. The family invited me over for a Hanukkah and Christmas celebration at which we sang Jewish songs and various festive carols. When we ran out of carols, we moved on to Handel’s Messiah, which her son was singing at the time. She sang everything with us – when she wasn’t singing her part, she sang the violin part. This was a woman who barely remembered people from outside her family – it was quite remarkable.

This was a woman who barely remembered people from outside her family – it was quite remarkable.

Another recent example I can cite is Paul Harvey, a composer with dementia, whom many people will have seen on TV performing a piano improvisation based on four notes.

It’s a beautiful example of the power of music-making – Mr Harvey wasn’t relying only on his procedural memory in the cerebellum to be able to do that, but all the areas of his brain that had only recently begun to be affected by dementia. For example, he will have used the frontal lobe for planning, the Broca’s area for communicating, and the hippocampus for producing and retrieving memories and regulating emotional responses.

On a related note, a study by neurologist Gottfried Schlaug found that the cerebellums of musicians were 5% larger than those who didn’t play music. How much does music’s ability to enhance memory continue to fascinate you, and what do studies like this say about its psychological effects?

Gottfried Schlaug and his colleagues compared a section of the corpus callosum, part of the cerebellum, in 30 professional musicians and 30 non-musicians. These musicians were matched for age, sex, and handedness.

These musicians were matched for age, sex, and handedness.

Schlaug and his colleagues did find a larger corpus callosum in musicians compared to non-musicians. However, this was attributable to a sub-group of musicians, who had started learning their instruments before they were seven.

This finding tells us that the larger size of the corpus callosum is related to the amount of practice musicians had done at an early age. The practice they’d done had laid down those procedural memories that I talked about to in response to the previous question.

Before you’re seven, your brain is at its most plastic or flexible, so anything you learn before the age of seven will strengthen the neural pathways and expand the cerebellum. But it isn’t only before you’re seven that you can achieve this. A study found that London taxi drivers had denser, or larger, parts of the brain that are responsible for route finding, and this result is based on their having learned the Knowledge of London. This effect mirrors a musician’s ability to perform certain melodies, harmonies, and so forth.

This effect mirrors a musician’s ability to perform certain melodies, harmonies, and so forth.

Schlaug’s study is of great interest to me because I was a professional musician before becoming a psychologist. My husband is a pianist, conductor and composer, and we brought up two children who went on to become professional musicians themselves.

Since I started working at the RNCM 15 years ago, I’ve worked explicitly with expert performers and music students seeking to pursue professional careers as singers and instrumentalists. So, I’m fascinated by the development of expertise and the role of practice in this development – we now know that practice makes permanent rather than perfect.

But whilst the size of a musician’s corpus callosum – and the reason it might be larger than those of non-musicians – is interesting, these findings don’t tell us anything about the psychological effects of music on listeners. That said, all that practice – and the motivation to do it, and to keep at it for a lifetime – certainly has a myriad of fascinating psychological effects on the musician.

Fortunately, performing has psychological effects too, and they include the release of dopamine by the nucleus accumbens.

You’ve had a successful career as a singer and have also won an award for your research on singers’ memorising strategies, which was inspired by your own experiences. Can you explain what the purpose of this research was?

Thank you for this question! The research for which I won the award was my PhD research, and you’re absolutely right to say that it was inspired by my experiences as a singer.

Singers typically perform from memory and, as well as specialising in contemporary music, I used to give a lot of song recitals. So, during my career, I spent a lot of time memorising and recalling words as well as music. I wanted to know whether the two kinds of information represented a double load on memory, so to speak, or if they interacted in such a way to be helpful. If I remembered the music, would I remember the words and vice versa?

However, the purpose of my research was not to find out what worked best for me, but what was likely to work best for all singers, and why. So, I’m not going to answer the question of which strategies were most effective based on my experience, but a different question: on the basis of the evidence from research, which strategies are most effective and why?

So, I’m not going to answer the question of which strategies were most effective based on my experience, but a different question: on the basis of the evidence from research, which strategies are most effective and why?

Based on the evidence from your research, which memorising strategies did you find to be most effective and why?

I started by reading everything I could find about the strategies that singing teachers recommend. However, there wasn’t very much because, at that time, memorisation wasn’t taught routinely in most institutions.

And I read everything I could find about the strategies recommended by instrumental teachers, going back to the end of the 19th century. Fortunately, psychologists started researching musicians’ memory in the middle of the 20th century. Yet, no one had asked my question about the relationship between words and melodies – at least not in terms of recall. I also looked at how actors memorised their lines – this was interesting because there’s a difference between memorising Shakespearean blank verse and plays in ordinary and vernacular language.

I began my own research with an interview study (as described in Aaron Williamon’s book on musical performance strategies and techniques). I asked five singers and a pianist who used to accompany himself singing cabaret songs how they went about memorising the words and melodies of songs. Unsurprisingly, I got six different answers. One respondent started with the words, another with the melody, and a third memorised them both together. The fourth respondent, my old music teacher, would speak the words to the rhythm of the melody. The fifth respondent, an opera singer, not only memorised words and melody, but also the position of his body, hands, head, and direction of eye gaze – it was a form of imaginary dance notation.

To summarise, these results weren’t very helpful. So, my next step was to conduct an observational study for which I recruited 15 singers – five amateurs, five professionals and five students. These participants learned and memorised the same song in up to six 15-minute practice sessions over two weeks and then sent me recordings of their practice sessions.

I told them to imagine they had been asked to give a concert in two weeks’ time, and they knew everything on the programme except this song, and to record all their practice sessions. I also asked them to tell me when they were and weren’t looking at the score. When they could sing the piece twice through from memory without a mistake, they could send me the tapes. Sadly, only 13 of the recordings were usable, but I had enough data to be able to write up my research.

I had thought that if I found out what the professionals did, they would have the best strategies – but this wasn’t the case. The ones who gave the most accurate performances after the shortest time weren’t all professional singers. But they all used one of two strategies: memorising the music thoroughly and then adding the words or memorising the words and music together.

How did you follow up on these findings?

I followed up with two experiments. The first one (reported in Ginsborg & Sloboda, 2007) involved sixty singers – 25 with relatively advanced musical qualifications and 35 without (I called them experts and novices).

I produced a new, unaccompanied folk song – I took the words of one folk song and put them to the melody of another. The study participants memorised the song in one of three ways during a single half-hour session:

- Words first, then melody, then both together.

- Melody first, then words, then both together.

- Words and melody together for the whole session.

I gave each participant a tape-cassette player to play the song back to themselves, and after the session was over, I asked them to sing me the song. I then interviewed them and talked to them for ten minutes about their musical qualifications and background. At the end of these conversations, I asked them to sing me the song again, and they were all caught off guard by this.

I recorded their second performances and analysed their errors and hesitations. The most accurate and fluent performances were given by the experts, as they had memorised the words and melody together. Based on the evidence I gathered, my recommendation to musicians would be not to treat the words and melody as two separate components. Providing the melody has been learned accurately in the first place, you should treat words and melody as two sides of the same coin or two facets of the same jewel. To go back to the brain, it’s processing the words and melody of the song in both hemispheres of the temporal lobe and the cerebellum.

Providing the melody has been learned accurately in the first place, you should treat words and melody as two sides of the same coin or two facets of the same jewel. To go back to the brain, it’s processing the words and melody of the song in both hemispheres of the temporal lobe and the cerebellum.

Finally, I did a second experiment (also reported in Ginsborg, 2004a) in which I tested the hypothesis that memorising words and melody together enables singers to memorise, and perform from memory, repertoire in languages they neither speak nor understand. For example, how do opera singers sing in Czech or Russian if this isn’t their native language? I did this by creating two songs that were settings, on the one hand, of semantically meaningful words in English and, on the other, of meaningless strings of numbers. The meaningless songs took longer to learn but were recalled just as accurately by the 20 expert singers who took part in the study, confirming my hypothesis.

It’s fascinating that you co-authored a study that investigated the mental representation of musical notation.

Having researched this subject in more detail, I discovered that the occipital lobe is the part of the brain which facilitates this representation. Can you explain, in a nutshell, what the occipital lobe helps musicians to do?

Having researched this subject in more detail, I discovered that the occipital lobe is the part of the brain which facilitates this representation. Can you explain, in a nutshell, what the occipital lobe helps musicians to do?The concept of mental representations is crucial to research on musicians’ memory. Way back at the beginning of the 20th century, the pedagogues Edwin Hughes and Theodor Leschetizky wrote about different ways of memorising: using visual, auditory, kinaesthetic, and analytic strategies.

Visual could be for the score, the fingers on the keyboard or any other instrument, or conductor’s cues. Auditory is for the sound of the music just sung or played, or about to be sung or played. Kinaesthetic is procedural, motor memory. But they’re all held together by an understanding of the structure of the music that is to be memorised.

Visual representations and imagery are processed in the occipital cortex. The most effective memorising strategies are those that make use of all four types of representation: visual, auditory, kinaesthetic, and analytic – and they may also make use of narrative, whereby the performer recalls the programme or the story of the music. The story may or may not be the same as that intended by the composer (see Ginsborg 2004b and Ginsborg, in press).

The story may or may not be the same as that intended by the composer (see Ginsborg 2004b and Ginsborg, in press).

I always say to my students – when you listen to a piece of music, don’t worry about how the composer would have analysed it or how an analyst would analyse it, just consider what makes sense to you.

Another piece of research that we found interesting was your most recent paper on Developing Familiarity in a New Duo. Can you talk us through the methods you used to explore the relationship between practice, rehearsal, and performance?

This piece of research was the third I’ve carried out in a series of what we call longitudinal case studies – longitudinal in the sense that they take a long time!

The first one involved repeated tests of recall over six years – and it’s called a case study because it involves only one or two musicians at a time, unlike my PhD research which involved more than 100 singers.

These three studies were also practice-led, in that – again, unlike my PhD research – they focused on my preparation for performance from memory, which I analysed myself. My colleague Roger Chaffin, a British cognitive scientist who has been based in the United States since the late 1960s, has conducted a series of longitudinal studies – principally with a pianist and a cellist – in which the musician participated in the research and he, as the cognitive scientist, conducted the analyses.

My colleague Roger Chaffin, a British cognitive scientist who has been based in the United States since the late 1960s, has conducted a series of longitudinal studies – principally with a pianist and a cellist – in which the musician participated in the research and he, as the cognitive scientist, conducted the analyses.

Roger has developed a theory of what he calls performance cues. He argues that musicians rely on landmarks in their mental representations – or maps – of the pieces they’re memorising to recall them when they perform from memory. He’d only worked with individual performers, however, whereas I was interested in joint representations, i.e., what happens when two musicians such as a singer and pianist are rehearsing together to produce a performance.

Roger and I collaborated on the design, data analysis, and interpretation of the findings of my first two studies. This collaboration involved recording my individual practice sessions, the pianist’s individual practice sessions, all our joint rehearsals, and the final performance. I then transcribed everything we sang, played, and said to each other, and we identified specific features of the words and music we thought we were likely to use as landmarks for retrieval when we performed from memory. After the performance, we noted the features that we had actually used as landmarks for retrieval, or performance cues.

I then transcribed everything we sang, played, and said to each other, and we identified specific features of the words and music we thought we were likely to use as landmarks for retrieval when we performed from memory. After the performance, we noted the features that we had actually used as landmarks for retrieval, or performance cues.

In the first study, we were able to show a relationship between what we rehearsed and how we rehearsed it and particular kinds of performance cues – especially those that we refer to as ‘expressive’. By that, I mean the locations where we wanted to convey a specific feeling or emotion to the audience.

I also carried out six free recalls over the course of the next five years – writing out the vocal line from memory – so that we could look at:

- How my memory for the piece faded over time.

- What I remembered.

- What I had forgotten.

I had always been a bit critical of one part of the theory, which proposed that performance cues are a subset of the landmarks or features of the music identified during rehearsal.

First of all, this would imply that performances are equivalent to rehearsals except that they take place in public. From my own experience, I know this isn’t so – unexpected things happen in performances, sometimes bad (such as memory lapses) but much more often good – and these may be remembered in subsequent performances of the same piece.

I also pointed out that you couldn’t call them performance cues unless they actually functioned as retrieval cues in performance. We had only looked at one performance – you wouldn’t know if something was a performance cue unless it cues performance next time.

So, in our second study, my pianist and I learned and performed another piece. We noted the features of the music we thought would function as performance cues. We gave the performance and identified the features we were actually thinking about.

That’s a very interesting approach. What were the results of this second study?

A few months later, I gave not another performance, as such, but a reconstruction of the piece from memory. I tried to sing as much as I could without the piano – not very much – and then, with the piano accompaniment, reconstructed it phrase by phrase until I could sing it all the way through from beginning to end without any mistakes. We recorded this session and transcribed it to see how I had built up the piece, and once again, the reconstruction process reflected the performance cues. But, importantly, I recalled the new thoughts I’d had while performing, as well as the features I’d prepared in rehearsal all those months before (Ginsborg et al., 2012).

I tried to sing as much as I could without the piano – not very much – and then, with the piano accompaniment, reconstructed it phrase by phrase until I could sing it all the way through from beginning to end without any mistakes. We recorded this session and transcribed it to see how I had built up the piece, and once again, the reconstruction process reflected the performance cues. But, importantly, I recalled the new thoughts I’d had while performing, as well as the features I’d prepared in rehearsal all those months before (Ginsborg et al., 2012).

This brings us to the third – and most recent – study. One potential criticism of the previous two studies is my very close relationship with my pianist – we’ve been together for 45 years and are married to each other. So, the question we asked in this most recent study was how does a new duo develop, and make use of, performance cues?

I travelled to Australia and stayed with a fellow musician, academic and researcher named Dawn Bennett, whom I didn’t know well – we had read each other’s work and met each other at conferences – and had never performed with before. We worked together every day and used the same method:

We worked together every day and used the same method:

- Recording our individual practice and joint rehearsals every day for a week.

- Transcribing everything we played and sang, and everything we said.

- Analysing them in the same ways we had done in previous studies.

We noted the features of the music that we identified as potential performance cues at the end of the rehearsal period, and those that we had actually used as cues during public performance, on two occasions at the end of the rehearsal period in March 2014, and again in a third public performance in January 2015.

The piece was new to us both and consisted of two songs for voice and viola. We both memorised one of the songs and sang or played the other using the score.

The paper outlines how certain cognitive processes are triggered by practice, rehearsal, and performance. What are these processes and, of all the results you collected from your research, which did you find most interesting?

To summarise the cognitive processes – musicians identify features of the music during individual practice and, if working with other musicians, joint rehearsal. Some of these are retained as performance cues in one, two, or more subsequent performances.

Some of these are retained as performance cues in one, two, or more subsequent performances.

Others are forgotten or assimilated. For example, taking a breath or using two down-bows instead of a down-bow and an up-bow becomes automatic, so the musician doesn’t have to think about it while performing. And some performance cues are thoughts the musician has in one performance that recur in a second performance.

For example, in one of the songs I sang in my second study, there were two canons in the piano part. I’d registered the first one during rehearsal, but I only registered the second one during the first performance. A few months later, when I sang the song again, I was consciously listening out for that second canon, and I sang my own entry differently as a result.

In the third study, when we compared Dawn’s and my use of performance cues, I had far more ‘core’ performance cues than she did. The things I prepared in rehearsal stuck during all three performances. But we think that this is because I was much more used to thinking about using them as a memorising strategy than she was. After all, I’d been thinking about them and teaching students at college to use them for nearly ten years by the time we carried out this project, so performance cues are second nature to me. Dawn is also a viola player and singers are more used to memorising than viola players.

After all, I’d been thinking about them and teaching students at college to use them for nearly ten years by the time we carried out this project, so performance cues are second nature to me. Dawn is also a viola player and singers are more used to memorising than viola players.

A lot of memorising is implicit – it comes with learning, which is why it’s so important to learn accurately. But implicit memory isn’t reliable in performance. It needs to be carried out deliberately, and you need to employ multiple strategies so that if one fails, another will kick in.

If, for example, you’re a singer and you get the words in the wrong order, it doesn’t matter if you know what it ought to sound like and can use an auditory memorising strategy to get the next set of words right.

More generally speaking, you might suddenly forget the sound of what comes next, but you can visualise the score. You might lose your place in the music, but if you have landmarks to remind you where the last section began or the next section starts, you can jump backwards or forwards as you need to, and the audience will never notice.

So, what did I find most interesting from my research? Well, one of the analyses we reported in the paper you read was of our rehearsal talk, what we said to each other in rehearsal. This turns out not to have reflected what we did in rehearsal. And it’s what we did that determined how we memorised and what we remembered. So, if you want to know how musicians prepare for performance, it’s better to watch and listen to what they play and sing than to rely on what they say!

Generally speaking, how can music have a positive impact on our cognitive ability on a day-to-day basis?

I don’t think anyone should listen to music or make music solely in order to improve their cognitive ability. I’m very distrustful of anyone who tells you that music makes you smarter, and I certainly don’t think music should be taught in schools to improve mathematical ability or social skills, even though there’s evidence that it does. Why not? Because music is important in its own right, and we should enjoy it for its own sake.

Having said that, singing is essential to communication between parents and small children, and it can foster a love of singing and music more generally. Learning to play an instrument requires discipline and practice and allows for the development of creativity through improvisation and composition. All of these characteristics can, of course, be transferred to other kinds of learned skills.

Playing music with other people develops the cognitive skills of attending, perceiving, listening, and adapting, as well as social skills to do with leadership and active membership of groups. Learning about music can provide windows into different periods of time and different cultures. All of that has got to have a positive impact on our cognitive ability.

What about music’s impact on mental health – how can music help alleviate various mental health conditions and act as a medium for processing emotions?

I’m currently editing an article on music in prison and how prisoners express difficult emotions through music, so this is a subject I’m well acquainted with.

Music can be a comfort, an escape, a way of remembering, and looking forward to happier times. Making music with other people is a way of communicating with them without having to use words and can often be a way to process emotions.

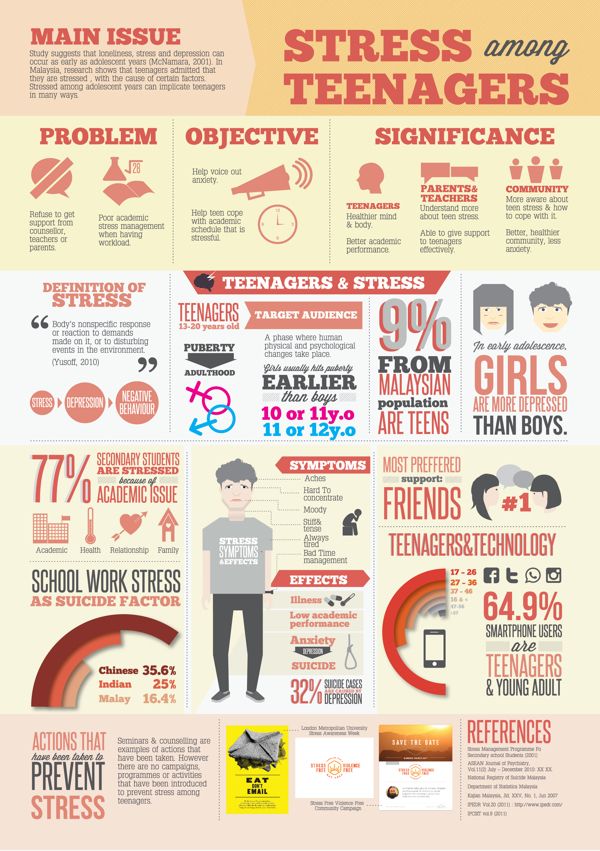

But I think we must differentiate between the mental health of musicians, and that of people who don’t identify as musicians. The way our profession has evolved, musicians have extremely stressful lives, and in some ways never more so than since the beginning of the pandemic.

That said, my colleague Susanna Cohen and I conducted a study for which we interviewed 24 freelance orchestral musicians about their experiences of the first lockdown. Some of the musicians we interviewed (Cohen & Ginsborg, 2021) said it was a great relief not to have to be away on tour all the time and working for such long hours. They can experience musculoskeletal disorders, repetitive strain anxiety, and – thinking particularly of mental health – stage fright or music performance anxiety.

They sometimes have to cope with difficult bandmates, desk partners, managers, and conductors. They have a lot to contend with, yet they’re still expected to turn out wonderful performances. Meanwhile, the wonderful music they produce is being ‘socially prescribed’ for people with mental health conditions and elderly people, for example. I gave a talk at Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts, and I began by saying that if you Google ‘music and health’, you will get a million results on how music is good for you, but if you Google ‘musician’s health’, you will get a million results on all of the bad things.

But, to end on a positive note, growing evidence shows that, for many musicians, it’s the amazing experience of performing that keeps them going. They couldn’t imagine their lives without it – and neither can I.

The influence of music on the human psyche: rock, pop, jazz and classical - what, when and why to listen?

Most people like to listen to music, not fully realizing what effect it has on a person and his psyche. Sometimes music causes excessive energy, and sometimes it has a relaxing effect. But whatever the listener's reaction to music, it certainly has the ability to influence the human psyche.

Sometimes music causes excessive energy, and sometimes it has a relaxing effect. But whatever the listener's reaction to music, it certainly has the ability to influence the human psyche.

So, music is everywhere, its diversity is incalculable, without it it is impossible to imagine a person's life, so the influence of music on the human psyche is, of course, a very important topic. Today we will consider the most basic styles of music and find out what effect they have on a person. nine0003

Rock - suicide music?

Many researchers in this field consider rock music to have a negative impact on the human psyche due to the “destructiveness” of the style itself. Rock music has been falsely accused of promoting suicidal tendencies in teenagers. But in fact, this behavior is not caused by listening to music, but even vice versa.

Some of the problems of a teenager and his parents, such as gaps in education, lack of necessary attention from parents, unwillingness to put himself on a par with his peers due to internal reasons, all this leads the psychologically fragile young organism of a teenager to rock music. And the music of this style itself has an exciting and energizing effect, and, as it seems to a teenager, fills in the gaps that need to be filled. nine0003

And the music of this style itself has an exciting and energizing effect, and, as it seems to a teenager, fills in the gaps that need to be filled. nine0003

Popular music and its influence

In popular music, the listener is attracted by simple texts and easy catchy melodies. Based on this, the influence of music on the human psyche in this case should be easy and unconstrained, but everything is quite different.

It is generally accepted that popular music has a very negative effect on a person's intellect. And many people of science claim that this is true. Of course, the degradation of a person as a person will not happen in one day or in one listening to popular music, it all happens gradually, over a long time. Pop music is mostly preferred by people prone to romance, and since it is significantly lacking in real life, they have to look for something similar in this direction of music. nine0003

Jazz and the psyche

Jazz is a very unique and original style, it does not have any negative impact on the psyche. To the sounds of jazz, a person simply relaxes and enjoys the music, which, like the waves of the ocean, rolls onto the shore and has a positive effect. Figuratively speaking, one can completely dissolve in jazz melodies only if this style is close to the listener.

To the sounds of jazz, a person simply relaxes and enjoys the music, which, like the waves of the ocean, rolls onto the shore and has a positive effect. Figuratively speaking, one can completely dissolve in jazz melodies only if this style is close to the listener.

Researchers from a medical institute conducted research on the influence of jazz on the musician himself, who plays a melody, especially improvisational playing. When a jazzman improvises, his brain turns off some areas, and on the contrary activates some, along the way, the musician plunges into a kind of trance, in which he easily creates music that he has never heard or played before. So jazz has an impact not only on the psyche of the listener, but also on the musician himself, who performs some kind of improvisation. nine0003

Is classical music ideal music for the human psyche?

According to psychologists, classical music is ideal for the human psyche. It has a good effect, both on the general condition of a person, and puts in order emotions, feelings and sensations. Classical music is able to eliminate depression and stress, helps to “drive away” sadness. And when listening to some of the works of V.A. Mozart, young children develop intellectually much faster. This is such classical music - brilliant in all manifestations. nine0003

It has a good effect, both on the general condition of a person, and puts in order emotions, feelings and sensations. Classical music is able to eliminate depression and stress, helps to “drive away” sadness. And when listening to some of the works of V.A. Mozart, young children develop intellectually much faster. This is such classical music - brilliant in all manifestations. nine0003

As mentioned above, music is the most diverse and what kind of listen a person chooses, listening to his personal preferences. This leads to the conclusion that the influence of music on the human psyche first of all depends on the person himself, on his character, personal qualities and, of course, temperament. So you need to choose and listen to music that is more to your liking, and not the one that is imposed or presented as necessary or useful.

Author – Stanislav Kolesnik

And at the end of the article I suggest listening to the wonderful work of V. A. Mozart's "Little Night Serenade" for a beneficial effect on the psyche:

A. Mozart's "Little Night Serenade" for a beneficial effect on the psyche:

The influence of music on the psychophysiological state of a person. Peculiarities of perception of music of different genres

Keywords: psychophysiology, art, music, classics, rock.

Musical art, like nothing else, can influence the physical, moral, aesthetic, cultural and moral state of a person. Studies of various scientists on the musical influence on a person force them to look for means that allow them to consider in more detail the degree of influence of various music on the behavior and condition of both a single individual and groups of people. The relevance of this issue lies in the combination of theoretical and empirical understanding of the influence of music on the emotional and physical state of a person, as well as the need to generalize and systematize theoretical knowledge regarding the problem of interaction between music and a person in order to successfully predict its influence. nine0003

nine0003

A great contribution to the study of musical acoustics was made by such famous scientists, teachers, musicians, psychologists as: V. L. Zhivova, B. V. Asafiev, N. A. Garbuzova, E. V. Nazaikinsky, V. V. Medushevsky, O. F. Sakhaltueva, N. I. Kozlova, M. Sh. Bonfeld, D. S. Merezhkovsky, E. N. Trubetskoy, S. N. Trubetskoy, P. A. Florensky, V. Khodasevich, A. S. Khomyakov, L. Shestov. Gotsdiner A. L., L. S. Vygotsky, A. V. Mudrik, D. B. Elkonina and others.

According to C. Disrens, who studied the works of many researchers, the solidarity of all works lies in the fact that the art of music enhances the metabolic mechanisms in the body; increases or decreases muscle energy; affects the rhythm and correctness of breathing, has a clear but changing effect on blood volume, rhythm and blood pressure, therefore, provides a physical basis for the genesis of emotions. [5, p.201]. agrees with his opinion and N. Cherkas, who said that "like music in general, and its individual musical tone, leads to pronounced physiological changes in the body. " [five]. nine0003

" [five]. nine0003

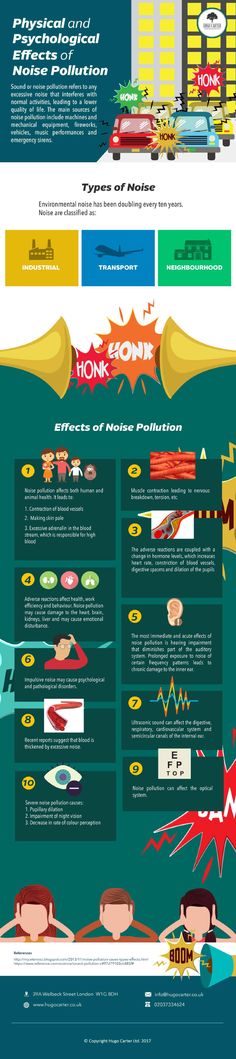

The description of the mechanism of the influence of music on the brain in the book by F. Bloom and A. Lazerson "Brain, Mind and Behavior" is interesting. It says that music, penetrating through the auricles, creates a nerve impulse that penetrates the brain, influencing the hypothalamus, and then the cerebral hemispheres, thereby creating the emotional component of the musical experience. It is also known that the pleasure center is located in the hypothalamus.

In studies devoted to the perception of music, V. S. Marakhasin and V. M. Tsekhanovsky noticed that the rhythm of a work has a special effect on the listener's body. As a result of the study, it was revealed that the rhythm of cardiac activity changes depending on the type of musical work. Studies made with the help of an electrocardiogram show a certain dominant frequency of cardiac activity that occurs at the time of listening to music. The emotional indicator of a person, like the heart, is under continuous control of the central nervous system, reflecting the processes occurring in the brain” [5, p. 204] nine0003

204] nine0003

Music, regardless of genre, has its own musical rhythm, which distinguishes it from any other work. A distinctive feature of rhythm, from melody, is that it is not recognized by an ordinary listener, however, the data of some studies show that it is rhythm that has a decisive influence on the physiological and emotional state of an individual in the process of musical experience.

The so-called pacing reaction, which is used to study the activity of the brain, contains an important feature, a direct dependence on the properties of the human nervous system, namely such a parameter as "strength-weakness". nine0003

In the course of the study, it can be assumed that the process of musical perception in people with a weak nervous system will have a different character. Unlike people with a strong nervous system, since the process of perception will develop into something more than just listening to compositions, the listener will feel much more deeply the content of the musical work, its structure, and most importantly, what the author wanted to express in this work. Individuals with a strong nervous system will prefer loud, fast paced music. nine0003

Individuals with a strong nervous system will prefer loud, fast paced music. nine0003

Musical and auditory activity has been studied in detail in domestic and foreign literature. What is the process of detailed and holistic perception of a musical work, the type of development of which is a specific sound process: what is the psychological message that provides artistic and aesthetic experience; what is the pattern of perception that reflects the musical language of specific works; what is the psychological mechanism of interaction between music and reality - all these are questions related to the understanding of problems, musical perception. Musical-auditory activity involves two levels - perceptual, associated with the perception of music and apperceptive, associated with its presentation. nine0003

Repeated perception of this or that music forms a complete picture of the work, in which such details and colors are revealed that can make a person understand the whole essence of the work, as well as feel what the author felt at the time of creating his creation.

V. D. Otromensky testifies that repeated listening to music leads to the improvement of the auditory properties of a person [8].

With the initial perception, that is, familiarization, musical and auditory activity tentatively covers the whole picture of the entire work, highlighting individual fragments. With repeated perception, prediction and anticipation occurs based on previously formed ideas. There is a process of comparison of the sounding, with the previously heard, with those standards that have already been formed in a person. The final stage is the rationally logical assimilation of musical material, the comprehensive comprehension and experience of its emotional meaning. The patterns identified by V. D. Ostromensky about the development of the dynamics of the perception of a musical work, in fact, are not, and cannot be, a generalized model of musical perception as a whole. The dynamics of the development of musical and auditory activity depends on professional, age and educational factors: a professional, with a single listening to a composition, is able to get a complete picture of a piece of music, while an amateur who does not have musical experience may not be enough for three or more listenings. nine0003

nine0003

The mechanism of musical experience has three properties - functional, motivational, operational, these three properties reflect the individual and personal qualities of a person.

For many years, scientists from different countries have been describing the influence of various trends in music on the psychophysiological and emotional state of a person. The most prominent representative of positive influence in all aspects is classical music.

It was created by brilliant people of their time, such music was written with soul and heart. That is why classical music is relevant to this day. It is pleasant to listen to such music, it is not just a pleasant perception of a piece of music, it is to some extent a desire in which one wants to know oneself, to understand how everything works. The concept of "natural harmony" is classical music. nine0003

Scientists, after research, believe that if a child at this age listens to the works of classical musicians, then the connection between his synopses will be stronger. Children who constantly listen to classical music develop spatial thinking more easily and develop a good memory. And children whose mothers listened to classical music during pregnancy are much calmer and more balanced.

Children who constantly listen to classical music develop spatial thinking more easily and develop a good memory. And children whose mothers listened to classical music during pregnancy are much calmer and more balanced.

You can find out how this or that music affects a person with the help of water. The most striking results were obtained by scientists who conducted the following experiments. A flask with water was placed between the speakers of the music center and various music was turned on. nine0003

After “listening” to the symphonies of Mozart and Beethoven with water, beautiful, regular-shaped crystals with distinct “rays” were obtained. The Department of Psychophysiology of the Faculty of Psychology of Moscow State University stated that classical music certainly affects the intellectual abilities of a person. It helps to increase the emotional activity of a person. During the period of such activity, mental abilities really increase.

As mentioned earlier, music of different genres affects the human body in different ways. One of such originality considered in this article is rock music. This music is distinguished by: nine0003

One of such originality considered in this article is rock music. This music is distinguished by: nine0003

- hard rhythm;

- monotonous repetitions;

- loudness, over frequency;

The properties of rock music are aimed at influencing the human body and his psyche. The following are the possible effects of rock music on the human brain:

- Aggressiveness.

- Rage.

- Anger.

- Forced actions.

- A state of trance of varying depth. nine0097

- Suicidal tendencies. In adolescents, this tendency begins to manifest itself from the age of 11–12, but when listening to rock music, this feature of the teenage psyche is provoked or greatly intensified at an older age.

- Involuntary muscle movement.

- Musical mania (the desire for a constant sound of rock music).

When considering styles that differ in sound, you can’t help but think that: classic is good music, but rock music is one continuous negative. nine0003

nine0003

The music of the rock genre has a half-century history, and with it many myths: amazing, and sometimes creepy. During the period of existence of rock music, an opinion has been formed in society rather negative than positive. List of the most common stereotypes found in the media:

- Rock music promotes Satanism, aggression, sexual promiscuity, drug addiction, etc.

- Rock music negatively affects the psyche (stupefies or drives you crazy) and health in general. nine0097

- Rock music is monotonous, rough, devoid of elementary melody and has very few styles.

Despite all this, in our opinion, if the lyrics and the appearance of the informals fade into the background, will there be less aggression in the musical environment? But, on the other hand, people will always find a reason for a dispute or bad behavior. It is natural. And the point here is rather not in music, but in age characteristics and in each person individually. In addition, even “ideologically correct” non-formal people wearing rock attributes rarely attack first, but rather respond with aggression to insults to their favorite music. And to judge a person by their clothes is short-sighted. All the same, in the end, you will have to see off, as the proverb says, according to the mind. nine0003

In addition, even “ideologically correct” non-formal people wearing rock attributes rarely attack first, but rather respond with aggression to insults to their favorite music. And to judge a person by their clothes is short-sighted. All the same, in the end, you will have to see off, as the proverb says, according to the mind. nine0003

Rock is a huge wall, a rock (rock actually is “rock” in English), it is an iceberg, it is a layer of world culture, it is a great phenomenon, an integral attribute of the last century. Rock music has changed the worldview of people, making them freer, more relaxed, openly expressing their opinions. At all times, rock musicians have been activists in the life of society, reacting sharply to all trends in it.

Each person chooses music to their liking individually. It is only important to understand that the influence of positive music makes an invaluable contribution to the correct moral, aesthetic, cultural, psychological and emotional state of the individual. And from the correct mass preferences of music and the development of society as a whole. nine0003

And from the correct mass preferences of music and the development of society as a whole. nine0003

Literature:

- Bloom F., Leatherson A., Iofstadter L. "Brain, mind and behavior" - M .: Mir, 2006.

- Bochkarev LL Psychology of musical activity / LL Bochkarev. - M: Publishing house "Classics-XXI", 2008. - 352 p.

- Glazkov VV Musical psychology: textbook.-method. allowance / V. V. Glazkov; ed. cand. psychologist. Sciences N. G. Abramyan; Vladim. state university im. A. G. N. G. Stoletovs. - Vladimir: Publishing House of VlGU, 2013. - 136 p.

- Kechkhuashvili G. N. On the problem of the psychology of music perception // Questions of Musicology. - M., 1960. - T. 3. A book about music: Sat. articles. - M., 1975.

- Kostyuk A.G. Culture of musical perception.//Artistic perception. - L., 1971.

- Leontiev A. N. Needs, motives and emotions. - M., 1971. - S. 1 -

- Marakhasin V. S., Tsekhanovsky V.