Seasonal affective disorder dsm

Seasonal Affective Disorders | AAFP

S. ATEZAZ SAEED, M.D., AND TIMOTHY J. BRUCE, PH.D.

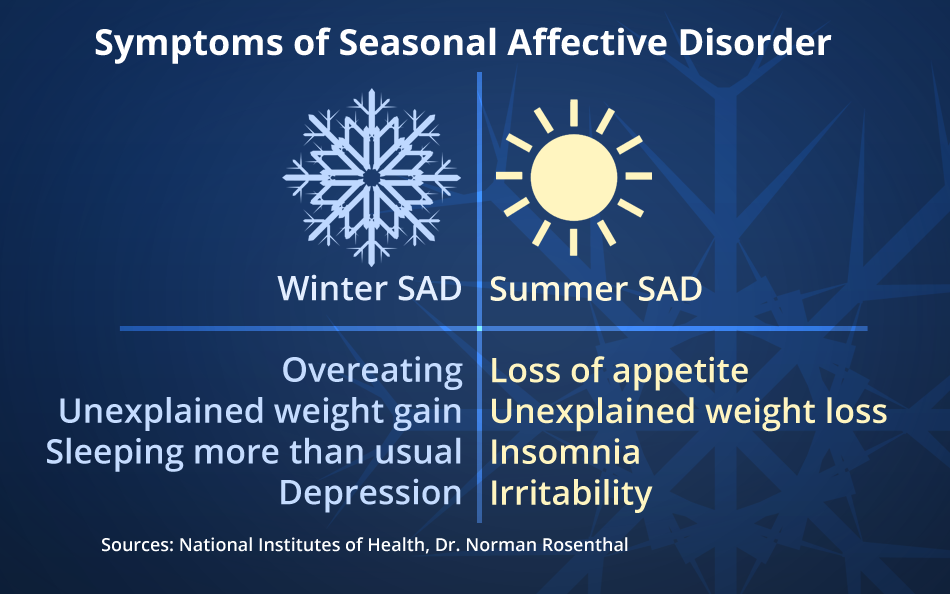

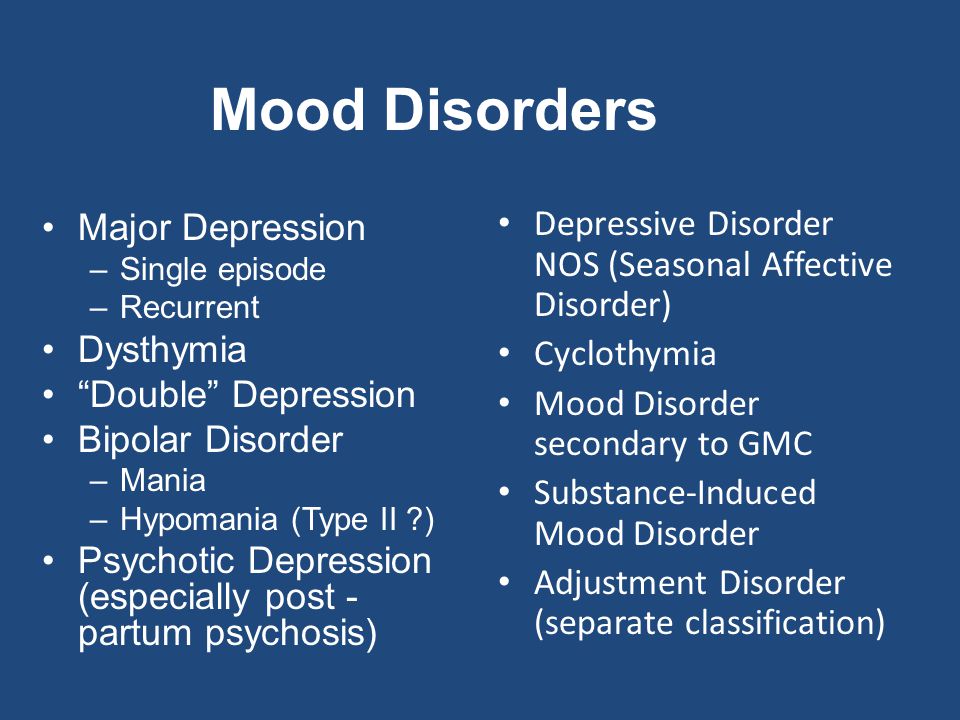

Seasonal affective disorder is a pattern of major depressive episodes that occur and remit with changes in seasons. It may be seen in major depressive or bipolar disorders, as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). The most recognized form of seasonal affective disorder, “winter depression,” is characterized by recurrent episodes of depression, hypersomnia, augmented appetite with carbohydrate craving, and weight gain that begin in the autumn and continue through the winter months.

Physicians have many options for treating seasonal affective disorder. While questions regarding the validity of seasonal affective disorder as a syndrome and the mechanism of action of light therapy continue to be investigated, the established effectiveness of light therapy in patients with winter depression supports the usefulness of assessment for this seasonal pattern and consideration of light therapy as an option in addition to existing treatment choices.

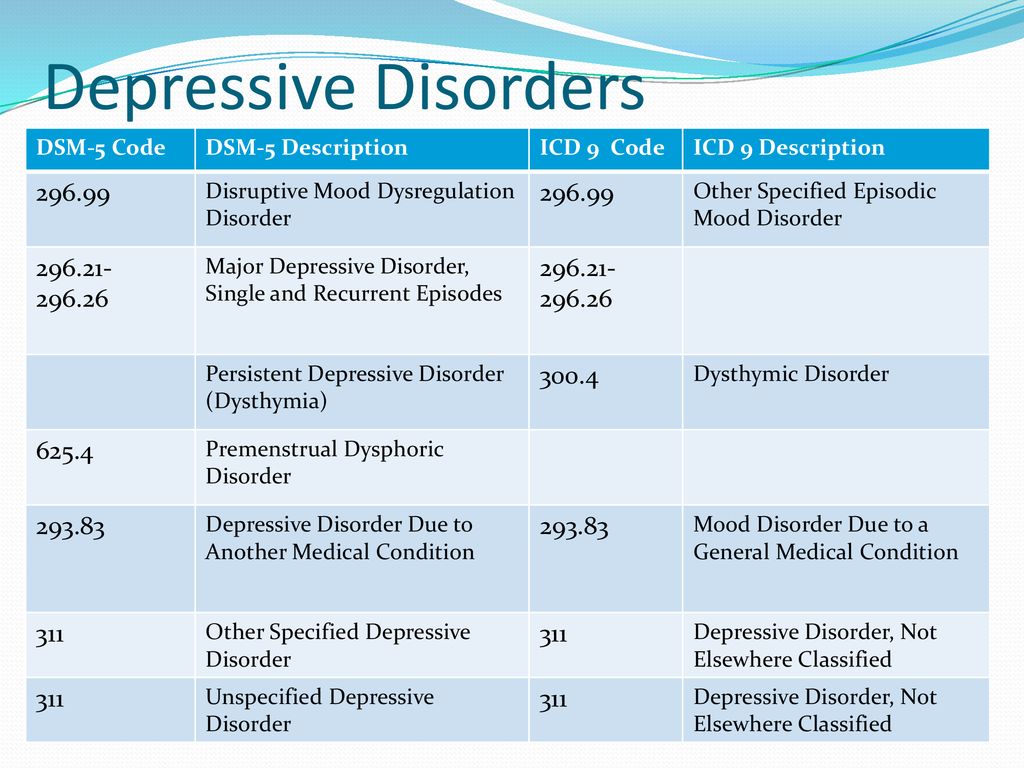

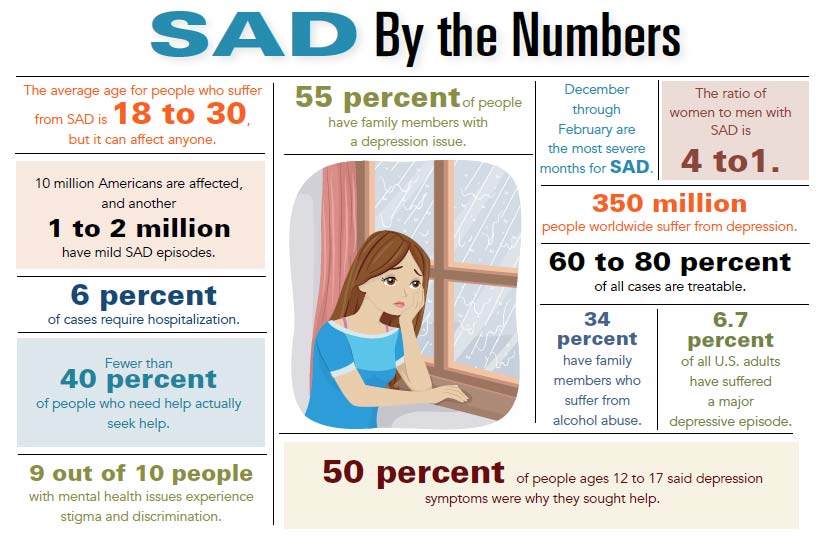

Depressive episodes are a primary public health problem and one of the most common psychiatric conditions in patients seeing family physicians, with a lifetime prevalence of 17.1 percent in the general population.1 Some of these mood disturbances follow regular seasonal patterns. These seasonal mood patterns have been termed seasonal affective disorders (SADs).

Description

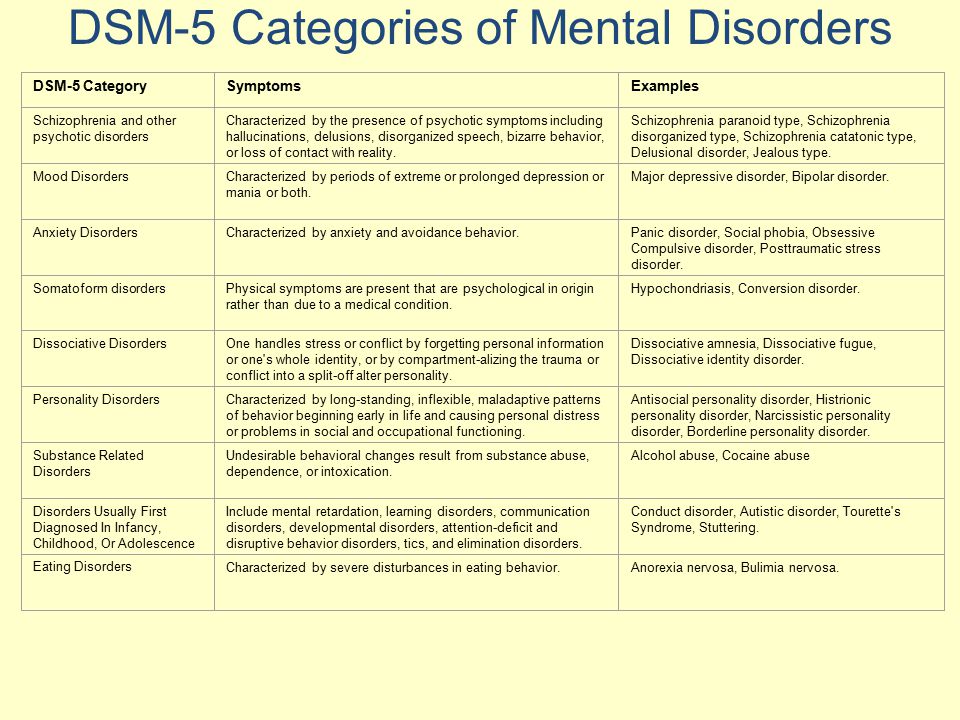

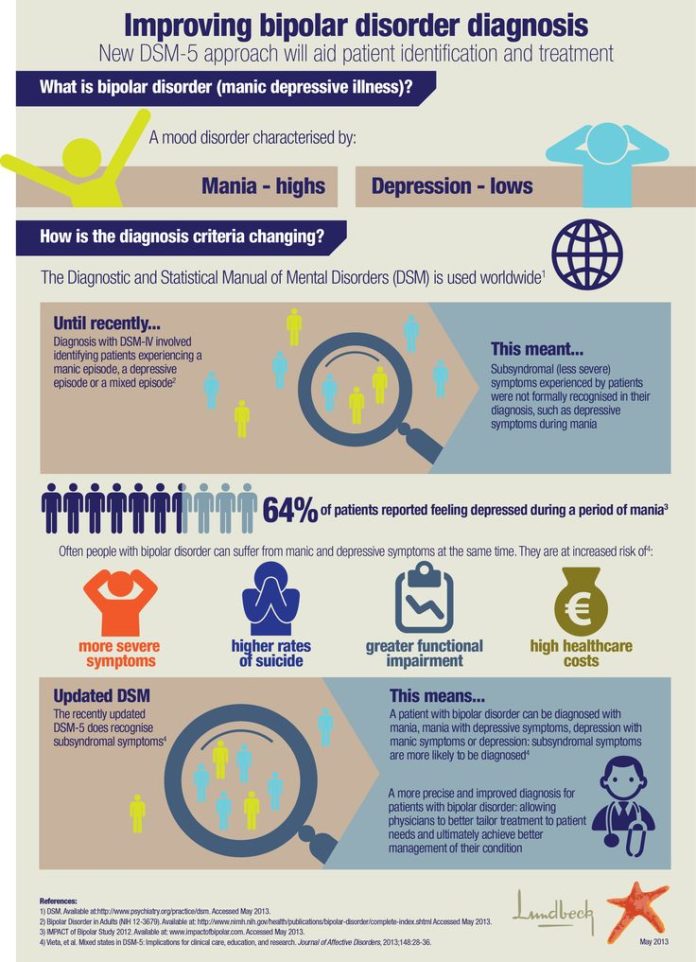

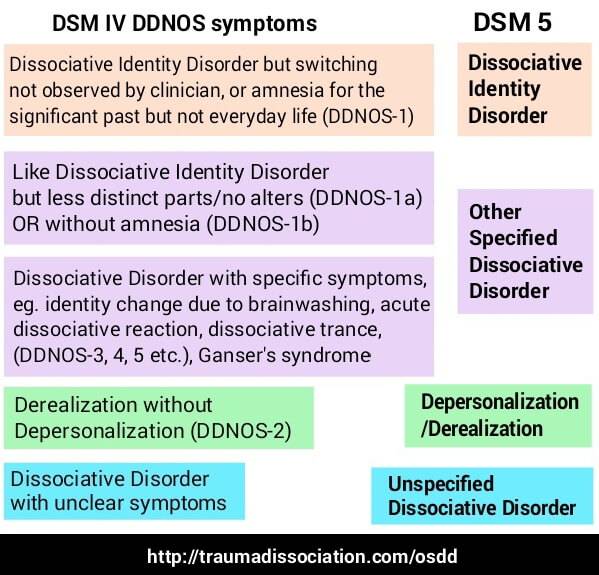

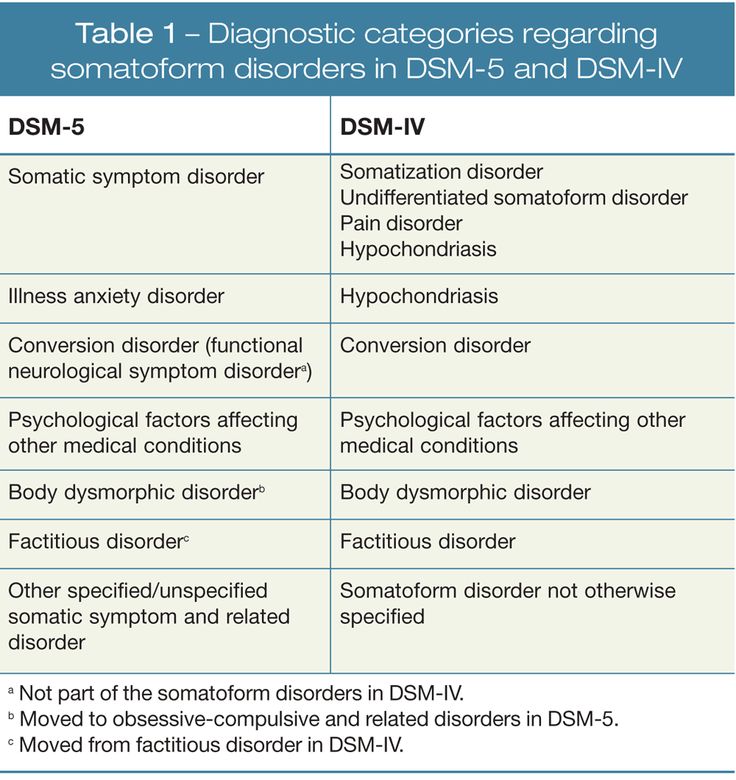

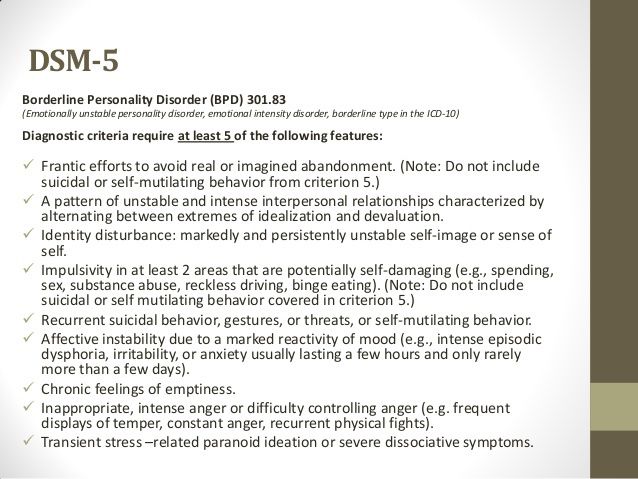

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) describes SAD not as a separate mood disorder but as a “specifier,” referring to the seasonal pattern of major depressive episodes that can occur within major depressive and bipolar disorders. 2

2

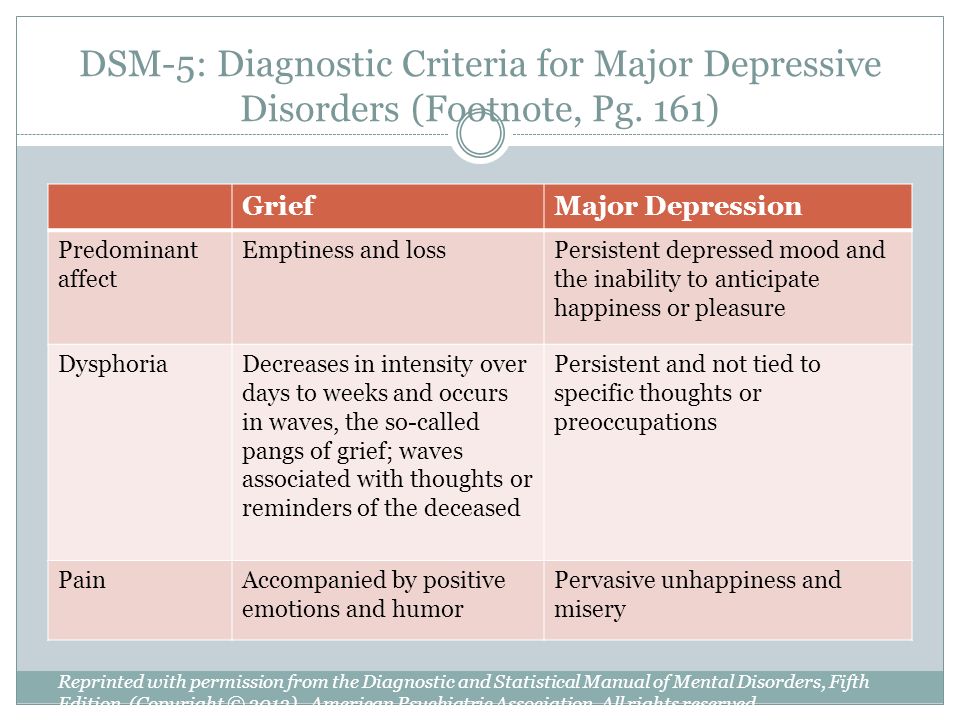

Table 1 summarizes the DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode. Table 2 describes the diagnostic criteria for “seasonal pattern specifier.”

The rightsholder did not grant rights to reproduce this item in electronic media. For the missing item, see the original print version of this publication.

The rightsholder did not grant rights to reproduce this item in electronic media. For the missing item, see the original print version of this publication.

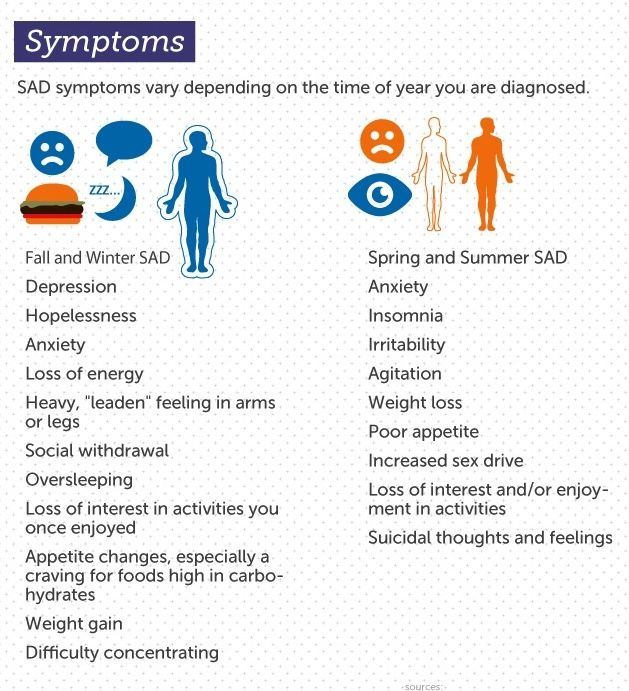

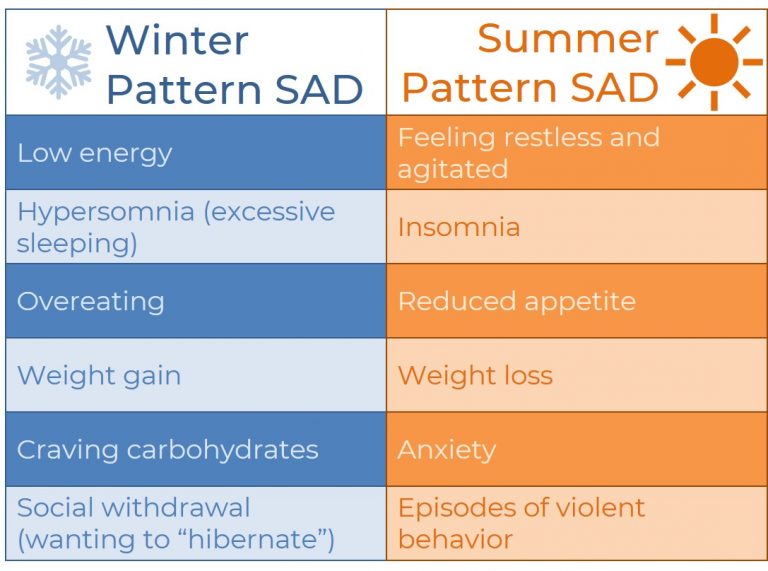

Two seasonal patterns have been identified. The most often recognized is the fall-onset type, also known as “winter depression,” in which major depressive episodes begin in the late fall to early winter months and remit during the summer months. Atypical signs and symptoms of depression2 predominate in cases of winter depression and include the following: (1) increased rather than decreased sleep; (2) increased rather than decreased appetite and food intake with carbohydrate craving; (3) marked increase in weight; (4) irritability; (5) interpersonal difficulties (especially rejection sensitivity), and (6) leaden paralysis (a heavy, leaden feeling in the arms or legs).

A spring-onset pattern (summer depression) also has been described, in which the severe depressive episode begins in late spring to early summer and is characterized by typical vegetative symptoms of depression, such as decreased sleep, weight loss and poor appetite.3

Recent studies report that most episodes of SAD occur within unipolar major depressive disorders, although a substantial minority have accompanying hypomanic episodes (bipolar II disorder, according to the DSM-IV), and very few are associated with manic episodes.4

Epidemiology

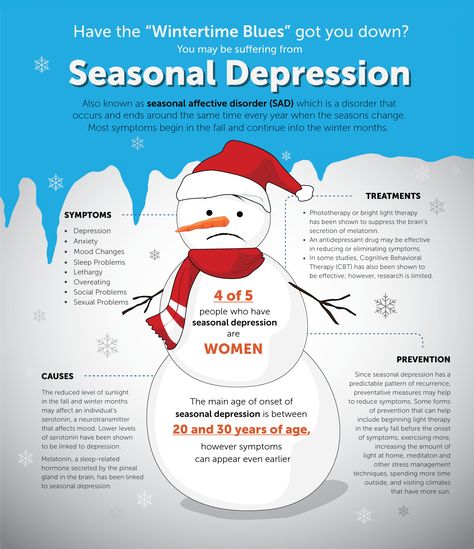

Surveys estimate that 4 to 6 percent of the general population experience winter depression, and another 10 to 20 percent have sub-syndromal features.5 Women with SAD outnumber men four to one. The average age of onset is approximately 23 years of age.4 The risk of SAD appears to decrease with age.2 Pilot studies of childhood cases of SAD suggest a prevalence rate between 1. 7 and 5.5 percent in children between the ages of nine and 19 years.6

7 and 5.5 percent in children between the ages of nine and 19 years.6

Syndromal Validity and Utility

An understanding of the features and treatment of SAD has grown within the context of a debate about the validity of SAD as a syndrome. For example, it has been suggested that seasonal variations in mood and behavior noted in the general population speak against SAD as a distinctive diagnostic entity.7 In addition, symptoms of SADs overlap with other, more established subtypes of depression—summer depressions with typical depressive episodes and winter depression with atypical depression.8,9 Winter depression responds to treatment with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs),10 as does atypical depression. Although summer depression has been studied less extensively than winter depression, it appears to respond to the same antidepressant pharmacotherapy that is used effectively to treat nonseasonal depression.

Some investigators have argued that the validity of SAD as a syndrome is supported by reports that the ratio of winter depression to summer depression increases with increasing latitude and that episodes of winter depression in particular tend to be longer and more severe at higher latitudes. 11 In addition, although manipulation of factors such as heat and humidity has not been effective in treating summer depression, winter depression has responded to artificial bright light therapy, also known as phototherapy.12 Interestingly, nonseasonal atypical depression has not responded to phototherapy.13

11 In addition, although manipulation of factors such as heat and humidity has not been effective in treating summer depression, winter depression has responded to artificial bright light therapy, also known as phototherapy.12 Interestingly, nonseasonal atypical depression has not responded to phototherapy.13

This issue is further complicated by the fact that although phototherapy has proved effective in the treatment of winter depression, its mechanism of action has not been established. Several mechanisms have been advanced, including circadian phase shifting, or reversing the increased melatonin, decreased 5-hydroxytryptamine and decreased dopamine neurotransmission observed in SAD,4 but it remains unestablished whether phototherapy achieves its well-documented effects through any of these or other mechanisms. Until further research clarifies these issues, phototherapy offers physicians an additional effective treatment option for clearly established cases of winter depression14 and justifies efforts made to identify this seasonal pattern in patients with depressive episodes.

Treatment Options and Guidelines

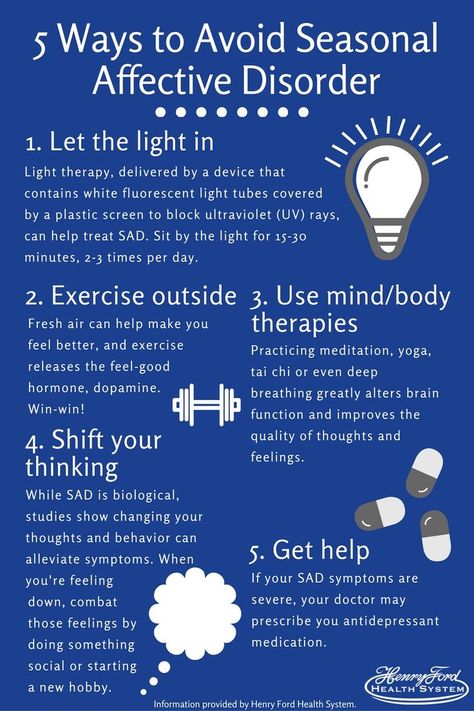

Although light therapy is uniquely effective for winter depressive episodes, treatment planning for patients with SAD should include consideration of all treatment options available, including somatic and psychosocial treatments.

The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR)14 has recently recommended practice guidelines for depression in primary care, including treatment of seasonal depression. According to these guidelines, the use of light therapy should be considered only in patients with well-documented seasonal, non-psychotic, winter depressive episodes occurring within recurrent major depressive disorder, bipolar II disorder or milder seasonal depressive episodes. It is also advised that physicians unfamiliar with light therapy consult a professional who is experienced and trained in its use. Light therapy is a first-line treatment consideration under the circumstances listed in Table 3. It is also a second-line option in patients who fail to respond to an adequate trial of medication.

| The patient is not severely suicidal. |

| There are medical reasons to avoid the use of antidepressants. |

| Patient has a history of favorable response to light therapy. |

| Patient has no history of significant negative effects to light therapy. |

| The patient requests light therapy. |

| An experienced practitioner deems that light therapy is indicated. |

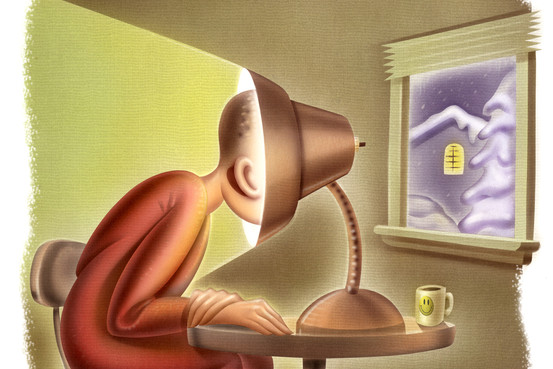

Light Therapy

Light therapy is initiated with a 10,000-lux light box directed toward the patient at a downward slant. The patient's eyes should remain open throughout the treatment session, although staring directly into the light source is unnecessary and is not advised. The patient should start with a single 10- to 15-minute session per day, gradually increasing the session's duration to 30 to 45 minutes. Sessions should be increased to twice a day if symptoms worsen. Ninety minutes a day is the conventional daily maximum duration of therapy, although there is no reason to limit the duration of sessions if side effects are not severe.15

Sessions should be increased to twice a day if symptoms worsen. Ninety minutes a day is the conventional daily maximum duration of therapy, although there is no reason to limit the duration of sessions if side effects are not severe.15

Commercially available fixtures are recommended over homemade devices to reduce electric risks associated with poor-quality construction. Commercial fixtures also include features designed to protect the eyes, such as light dispersion and screens that eliminate ultraviolet (UV) rays. Fluorescent light is preferred over incandescent because the small point source of the latter is more conducive to retinal damage. Use of “full-spectrum” light appears to be unnecessary.

No time of day is optimal for light therapy. Some studies have reported the superiority of morning sessions,16 while others have shown no significant difference between times of administration.17 In the absence of clear indications, convenience should be the prevailing consideration.

Although some patients show an immediate benefit from light therapy, most take two to four days to experience a sustained antidepressant response. However, a lack of response within the first week should not be interpreted as a treatment failure, since evidence suggests that longer durations of therapy can improve response and that the initial response to light can take several weeks to appear.18 The treatment plan should be reevaluated, however, if the patient shows any clinical worsening or if a response is not evident in four to six weeks.

Patients who respond to light therapy should continue treatment until sufficient daily light exposure is available to them through other sources, typically from springtime sun.4 Premature discontinuation can precipitate relapse.

Recently, light visors have been manufactured that can deliver similar illumination in a more convenient and portable fashion.19 However, although studies using light boxes have suggested a positive relationship between the intensity of light and the clinical response,20 results from studies of light visors have not shown such a relationship. Some investigators have concluded that light boxes operate differently from visors.21

Some investigators have concluded that light boxes operate differently from visors.21

It is important to note that no evidence indicates that tanning beds, where the eyes are generally covered and the subject's skin is exposed to light, are useful in the treatment of SAD. Furthermore, the light sources in tanning beds are relatively high in UV rays, which can be harmful to both the eyes and the skin.

When properly administered, light therapy appears to have few side effects, none of which is irreversible. Caution is required when using light therapy in patients with a tendency toward mania, or in those with photosensitive skin or medical conditions that render their eyes vulnerable to phototoxicity. Adverse effects associated with the use of light therapy22 are listed in Table 4. If side effects occur, they typically respond to a “dose” reduction (e.g., decreased duration of sessions, increased distance from the light source or periodic breaks during sessions).

| Photophobia |

| Headache |

| Fatigue |

| Irritability |

| Hypomania |

| Insomnia (if light therapy is used too late in the day) |

| Possible retinal damage (although there is no evidence to date) |

Predictors of a positive response to light therapy include disorders characterized by a history of hypersomnia, a preponderance of atypical vegetative symptoms and an increased intake of sweet foods in the afternoon, as well as a history of reactivity to ambient light.23,24

Table 5 provides patient resource information, including associations that provide support to persons with SAD and sources for light fixtures.

| Places where light fixtures may be purchased: | |

| Apollo Light Systems | |

| 352 West 1060 South | |

| Orem, Utah 84058 | |

| Telephone: 800-545-9667 | |

| Hughes Lighting Technologies | |

| 34 Yacht Club Dr. | |

| Lake Hopatcong, NJ 07849 | |

| Telephone: 973-663-1214 | |

| Northern Light Technologies | |

| 8971 Henri Bourassa West | |

| Montreal, Canada h5S 1P7 | |

| Telephone: 800-263-0066 | |

| The SunBox Company | |

| 19217 Orbit Dr. | |

| Gaithersburg, MD 20879 | |

| Telephone: 800-548-3968 | |

| Sources of information: | |

| National Organization for Seasonal Affective Disorders (NOSAD) | |

| P.O. Box 40190 | |

| Washington, DC 20016 | |

| (Correspondence handled by mail only) | |

| National Depressive and Manic Depressive Association (NDMDA) | |

730 N. Franklin, Suite 501 Franklin, Suite 501 | |

| Chicago, IL 60610 | |

| Telephone: 800-82-NDMDA (800-826-3632) | |

| Society for Light Treatment and Biological Rhythms (SLTBR) | |

| 10200 W. 44th Ave., # 304 | |

| Wheat Ridge, CO 80033-2840 | |

| Telephone: 303-424-3697 | |

| National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) | |

| Telephone: 800-421-4211 | |

| National Mental Health Association (NMHA) | |

| 1021 Prince St. | |

| Alexandria, VA 22314-2971 | |

| Telephone: 800-969-6642 | |

Pharmacotherapy

Although data are limited for the pharmacotherapeutic treatment of SADs specifically, the many studies demonstrating the efficacy of pharmacotherapy in mood disorders, none of which specifically excluded seasonal variations, have supported the use of conventional, first-line antidepressant pharmacotherapy for SADs. 14

14

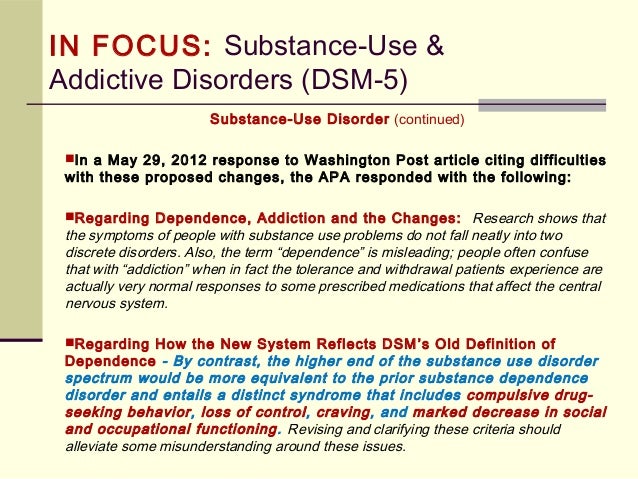

Specific studies of SAD have investigated both antidepressant and nonantidepressant drugs. Few of these studies, however, were placebo-controlled. In controlled trials, fluoxetine, propranolol, and d-fenfluramine have been found effective.12,25–27 Open trials have also shown favorable results with moclobemide,25 tranylcypromine28 and bupropion.29Table 6 lists factors suggesting the use of medications in patients with SADs.

| Prior positive response to antidepressants or mood stabilizers |

| High suicide risk* |

| Marked impairment in occupational functioning or in usual social activities or relationships with others; significant functional impairment |

| History of recurrent depression in the moderate-to-severe range |

| Severe subtypes of depression (e.g., psychotic, melancholic, chronic) |

| Patient preference |

| Failure to respond to light therapy or psychotherapy |

Since SADs may occur concurrently with bipolar or unipolar disorders, the type of disorder should guide medication selection. As with light therapy, physicians should remain sensitive to the risk of precipitating a manic episode in patients with bipolar disorder when using antidepressants.

As with light therapy, physicians should remain sensitive to the risk of precipitating a manic episode in patients with bipolar disorder when using antidepressants.

Other Treatments

To our knowledge, no controlled studies have investigated the efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy or psychotherapy for SAD specifically. However, very strong evidence supports the efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy,30 two forms of psychotherapy (interpersonal psychotherapy31 and cognitive therapy32), and combined psychotherapy and somatic therapy33 in the treatment of depression.

Accordingly, indications for the use of electroconvulsive therapy in patients with SAD are the same as those in patients with nonseasonal depression and include non-response to alternative treatments, high suicide risk, psychotic depression and previous positive response to electroconvulsive therapy.30

At this time, interpersonal therapy and cognitive therapy are not contraindicated in patients with SAD. These types of psychotherapy should be considered in patients whose depressive episodes are unipolar, non-psychotic, nonsevere and not chronic, and in those who do not respond to, who refuse or who cannot participate in phototherapy or pharmacotherapy. Patients with SAD may have personal and interpersonal issues like those occurring in patients with nonseasonal depression and may benefit from the adjunctive use of psychotherapy.

These types of psychotherapy should be considered in patients whose depressive episodes are unipolar, non-psychotic, nonsevere and not chronic, and in those who do not respond to, who refuse or who cannot participate in phototherapy or pharmacotherapy. Patients with SAD may have personal and interpersonal issues like those occurring in patients with nonseasonal depression and may benefit from the adjunctive use of psychotherapy.

The question of whether light therapy can be combined effectively with pharmacotherapy also awaits controlled study. Although several advantages can be hypothesized (e.g., their concurrent use may ease side effects of medication by allowing lower dosages), current guidelines discourage the simultaneous use of light therapy and medication before either one has been proved insufficient.14

Referral and Consultation

Family practice physicians treating patients with SAD may find specialty referral or consultation useful under some circumstances. AHCPR guidelines include circumstances in which referral or consultation is recommended. The guidelines are suggested for use in all types of depression and are not specific to SADs. Since response to light therapy is usually apparent within the first two weeks of therapy (usually within the first few days) and since safety and efficacy have not been fully established beyond two weeks, the AHCPR recommends consultation with a specialist to determine specific risks and benefits for individual patients.

AHCPR guidelines include circumstances in which referral or consultation is recommended. The guidelines are suggested for use in all types of depression and are not specific to SADs. Since response to light therapy is usually apparent within the first two weeks of therapy (usually within the first few days) and since safety and efficacy have not been fully established beyond two weeks, the AHCPR recommends consultation with a specialist to determine specific risks and benefits for individual patients.

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) - Symptoms and causes

Overview

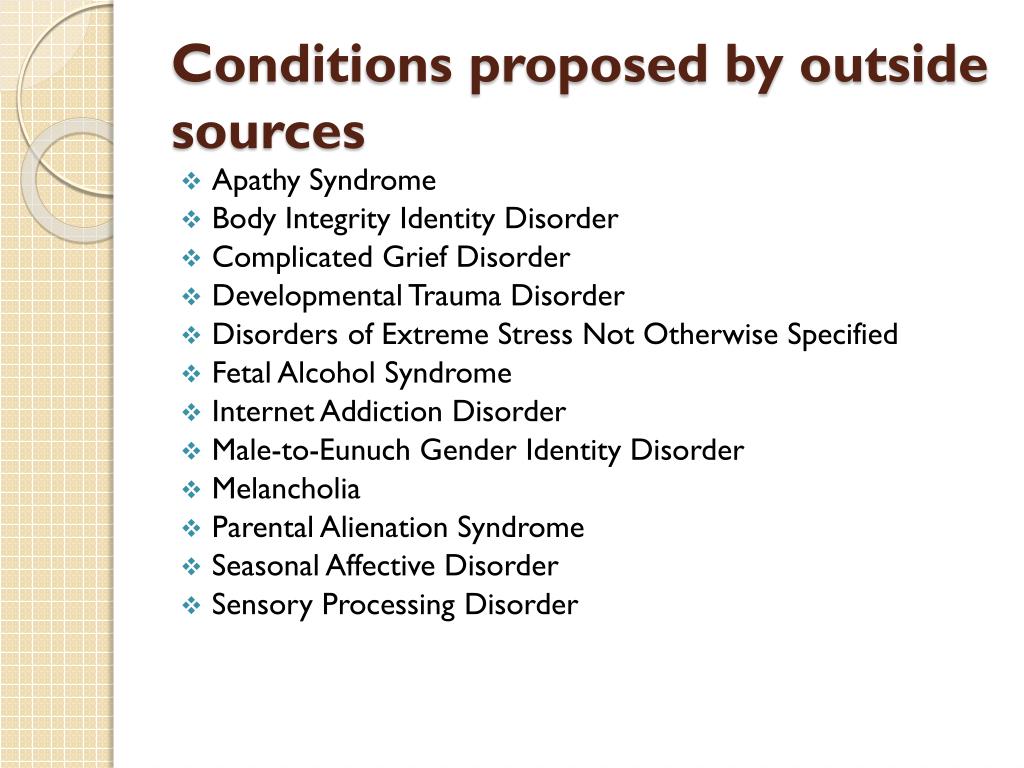

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a type of depression that's related to changes in seasons — SAD begins and ends at about the same times every year. If you're like most people with SAD, your symptoms start in the fall and continue into the winter months, sapping your energy and making you feel moody. These symptoms often resolve during the spring and summer months. Less often, SAD causes depression in the spring or early summer and resolves during the fall or winter months.

Less often, SAD causes depression in the spring or early summer and resolves during the fall or winter months.

Treatment for SAD may include light therapy (phototherapy), psychotherapy and medications.

Don't brush off that yearly feeling as simply a case of the "winter blues" or a seasonal funk that you have to tough out on your own. Take steps to keep your mood and motivation steady throughout the year.

Products & Services

- Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Symptoms

In most cases, seasonal affective disorder symptoms appear during late fall or early winter and go away during the sunnier days of spring and summer. Less commonly, people with the opposite pattern have symptoms that begin in spring or summer. In either case, symptoms may start out mild and become more severe as the season progresses.

Signs and symptoms of SAD may include:

- Feeling listless, sad or down most of the day, nearly every day

- Losing interest in activities you once enjoyed

- Having low energy and feeling sluggish

- Having problems with sleeping too much

- Experiencing carbohydrate cravings, overeating and weight gain

- Having difficulty concentrating

- Feeling hopeless, worthless or guilty

- Having thoughts of not wanting to live

Fall and winter SAD

Symptoms specific to winter-onset SAD, sometimes called winter depression, may include:

- Oversleeping

- Appetite changes, especially a craving for foods high in carbohydrates

- Weight gain

- Tiredness or low energy

Spring and summer SAD

Symptoms specific to summer-onset seasonal affective disorder, sometimes called summer depression, may include:

- Trouble sleeping (insomnia)

- Poor appetite

- Weight loss

- Agitation or anxiety

- Increased irritability

Seasonal changes and bipolar disorder

People who have bipolar disorder are at increased risk of seasonal affective disorder. In some people with bipolar disorder, episodes of mania may be linked to a specific season. For example, spring and summer can bring on symptoms of mania or a less intense form of mania (hypomania), anxiety, agitation and irritability. They may also experience depression during the fall and winter months.

In some people with bipolar disorder, episodes of mania may be linked to a specific season. For example, spring and summer can bring on symptoms of mania or a less intense form of mania (hypomania), anxiety, agitation and irritability. They may also experience depression during the fall and winter months.

When to see a doctor

It's normal to have some days when you feel down. But if you feel down for days at a time and you can't get motivated to do activities you normally enjoy, see your health care provider. This is especially important if your sleep patterns and appetite have changed, you turn to alcohol for comfort or relaxation, or you feel hopeless or think about suicide.

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free, and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips and current health topics, like COVID-19, plus expertise on managing health.

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which

information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with

other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could

include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected

health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health

information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of

privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could

include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected

health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health

information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of

privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Causes

The specific cause of seasonal affective disorder remains unknown. Some factors that may come into play include:

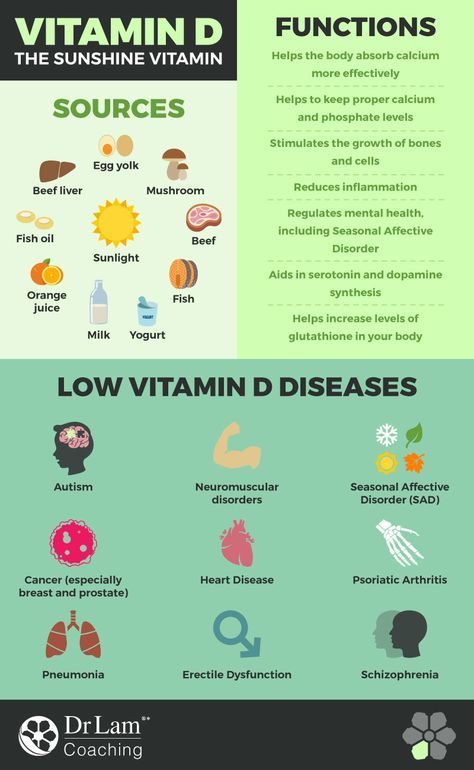

- Your biological clock (circadian rhythm). The reduced level of sunlight in fall and winter may cause winter-onset SAD. This decrease in sunlight may disrupt your body's internal clock and lead to feelings of depression.

- Serotonin levels. A drop in serotonin, a brain chemical (neurotransmitter) that affects mood, might play a role in SAD. Reduced sunlight can cause a drop in serotonin that may trigger depression.

- Melatonin levels. The change in season can disrupt the balance of the body's level of melatonin, which plays a role in sleep patterns and mood.

Risk factors

Seasonal affective disorder is diagnosed more often in women than in men. And SAD occurs more frequently in younger adults than in older adults.

Factors that may increase your risk of seasonal affective disorder include:

- Family history. People with SAD may be more likely to have blood relatives with SAD or another form of depression.

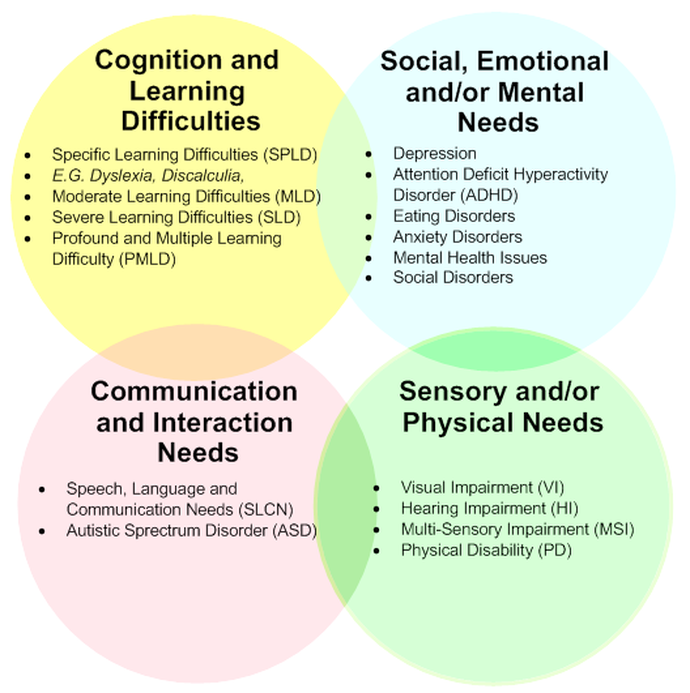

- Having major depression or bipolar disorder. Symptoms of depression may worsen seasonally if you have one of these conditions.

- Living far from the equator. SAD appears to be more common among people who live far north or south of the equator. This may be due to decreased sunlight during the winter and longer days during the summer months.

- Low level of vitamin D. Some vitamin D is produced in the skin when it's exposed to sunlight. Vitamin D can help to boost serotonin activity. Less sunlight and not getting enough vitamin D from foods and other sources may result in low levels of vitamin D in the body.

Complications

Take signs and symptoms of seasonal affective disorder seriously. As with other types of depression, SAD can get worse and lead to problems if it's not treated. These can include:

- Social withdrawal

- School or work problems

- Substance abuse

- Other mental health disorders such as anxiety or eating disorders

- Suicidal thoughts or behavior

Prevention

There's no known way to prevent the development of seasonal affective disorder. However, if you take steps early on to manage symptoms, you may be able to prevent them from getting worse over time. You may be able to head off serious changes in mood, appetite and energy levels, as you can predict the time of the year in which these symptoms may start. Treatment can help prevent complications, especially if SAD is diagnosed and treated before symptoms get bad.

However, if you take steps early on to manage symptoms, you may be able to prevent them from getting worse over time. You may be able to head off serious changes in mood, appetite and energy levels, as you can predict the time of the year in which these symptoms may start. Treatment can help prevent complications, especially if SAD is diagnosed and treated before symptoms get bad.

Some people find it helpful to begin treatment before symptoms would normally start in the fall or winter, and then continue treatment past the time symptoms would normally go away. Other people need continuous treatment to prevent symptoms from returning.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Associated Procedures

News from Mayo Clinic

Products & Services

Symptoms of seasonal affective disorder - Allianz CMH

According to various sources, about 5-7% of the population of our country suffers from various types of depression, and this figure is steadily growing every year.

Seasonal affective disorder is a type of endogenous depression. Endogenous refers to disorders that are not associated with external stressors or causes. Scientists cannot yet name the exact reason for their occurrence, but heredity and genetic breakdowns play a large role. nine0003

A feature of this type of depression is their periodicity: they occur at the same time of the year, beginning and ending in approximately the same months. Exacerbation of the disease occurs in the autumn-winter (rarely spring) period.

This disorder occurs in any age group, but is most common in individuals between the ages of 18 and 30. Women get sick 4 times more often than men. Seasonal affective disorder is rare in adolescence and almost impossible in children under 10 years of age. After the age of 30, the likelihood of developing seasonal disorders decreases. nine0003

Causes of development

There are several theories of the development of this pathology:

- Chronobiological theory, according to which there is a molecular biochemical disturbance of circadian rhythms (“internal clock” of a person).

It is believed that not the least important in this process is the decrease in the duration of daylight hours in the autumn-winter time and the lack of sunlight for the human body.

It is believed that not the least important in this process is the decrease in the duration of daylight hours in the autumn-winter time and the lack of sunlight for the human body. - The monoamine theory claims that seasonal depression is based on a decrease in the production of biologically active substances of the brain (neurotransmitters) in the autumn-winter period: serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine. nine0016

- The theory of stress diathesis consists in the presence of an organism's predisposition (diathesis) to this disease, the development of which is provoked by external adverse factors.

- Genetic theory. The cause of seasonal affective disorder may be an anomaly of certain genes on chromosome 11, as well as the presence of a genetic predisposition (heredity).

Symptoms and manifestations

There are two main types of manifestations of seasonal depression:

- The first type is characterized by drowsiness, pronounced appetite, cravings for flour and sweets, weight gain, and meteosensitivity.

- The second type, on the contrary, is manifested by a decrease in sensitivity (anesthesia) to everything that happens - a decrease in the need for sleep, lack of appetite, inhibition of the body's reactions to any external influences and stimuli.

The first type of affective disorders is more favorable, the periods of depression are shorter (up to four months) and easier to treat. nine0003

The second type is much more severe. It is characterized by long episodes of "exacerbation", in which the period of depression can last up to 6-9 months or more. In the absence of adequate treatment, so-called double depressions may occur. In such cases, seasonality is not traced, and there are one or more long periods of depression one after another. In order to prevent such conditions, it is important to seek help from a specialist in time.

If we talk about the specific manifestations of seasonal affective disorder, its symptoms are as follows:

- depressed mood, lack of positive reactions at certain times of the year - autumn, winter or spring;

- symptoms persist for two weeks or more;

- reduced ability to concentrate, remember, absent-mindedness;

- feeling unwell in the morning and feeling better in the evening;

- fatigue, decreased overall tone, lack of strength, decreased motor activity.

nine0051

nine0051 - Drug therapy consists of prescribing antidepressants. Modern antidepressants are well tolerated, safer than previous generations of drugs, but at the same time comparable to them in terms of effectiveness.

- Light therapy is a course of sessions of bright contrasting light directed into the patient's eyes. Bright light affects the retina of the eye and causes a reflex activation of serotonin production.

- Psychotherapy is an auxiliary component of complex treatment and is used at all stages of this pathology. This method helps the patient to change the attitude towards the disease - to alleviate the subjective experience of symptoms, increase the motivation for treatment. nine0016

- Number:

- Thematic issue "Neurology, Psychiatry, Psychotherapy" No. 2 (37), cherven 2016 nine0016

Symptoms of seasonal affective disorder coincide with signs of severe physical illness or manifestations of serious mental disorders. Timely differential diagnosis by a qualified specialist will allow to establish the causes of the disease and promptly begin therapy.

How to treat seasonal affective disorder

The development of seasonal depression is based on a metabolic disorder in the brain tissue, as well as a violation of human circadian rhythms due to lack of sunlight. Therefore, the main methods of treating this pathology are pharmacotherapy and light therapy. nine0003

A balanced diet, vitamin therapy, moderate exercise and an active lifestyle play an important role in treatment.

Seasonal affective disorder is successfully treated. Self-treatment does not guarantee stable and long-term results. Qualified specialists who have positive experience in the treatment of this disease will promptly conduct a differential diagnosis, clarify the diagnosis and prescribe adequate treatment.

Seasonality and atypicality in affective disorders: topical issues

Authors: I.D. Spirin, A.V. Shornikov

07/09/2016

In recent years, especially during a recession, the prevalence of mental disorders in general and depressive disorders in particular has increased. According to the forecasts of the World Health Organization, by 2020 mental illness will be among the main causes of disability in the population, and affective disorders will take second place after coronary heart disease. Despite the rather high proportion of bipolar affective disorder (BAD) both in the general population and in clinical samples, BAD is often diagnosed quite late. Unresolved problems in this area are atypical and seasonal patterns in affective disorders.

According to the forecasts of the World Health Organization, by 2020 mental illness will be among the main causes of disability in the population, and affective disorders will take second place after coronary heart disease. Despite the rather high proportion of bipolar affective disorder (BAD) both in the general population and in clinical samples, BAD is often diagnosed quite late. Unresolved problems in this area are atypical and seasonal patterns in affective disorders.

I.D. Spirin

One of the first references to the seasonality of bipolar disorder we find in S.S. Korsakov in the second edition of the "Course of Psychiatry" (1901): "In some patients, an attack appears fatally at certain intervals, as if according to a calendar, number for number."

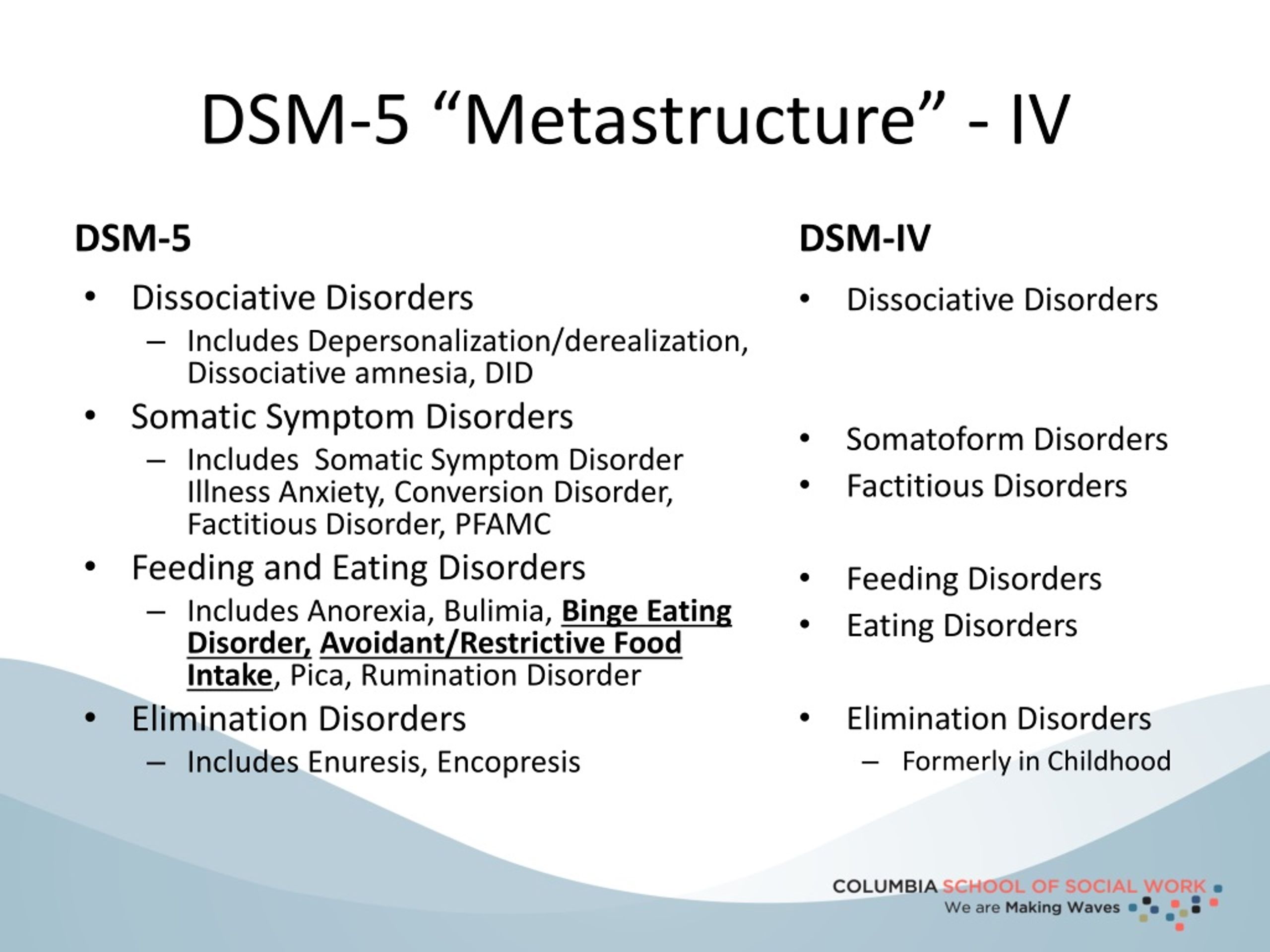

When applying the ICD-10 criteria, it is not possible to take into account some of the indicated features of BAD, including seasonality, in the diagnosis. Based on these criteria, seasonal patterns in bipolar disorder are coded under F 31.8 Other Bipolar Affective Disorders. This rubric also includes BAD type II, recurrent manic episodes, which makes this rubric extremely heterogeneous, making further research difficult [1]. nine0087 According to DSM-V, the following features of bipolar disorder are distinguished:

Based on these criteria, seasonal patterns in bipolar disorder are coded under F 31.8 Other Bipolar Affective Disorders. This rubric also includes BAD type II, recurrent manic episodes, which makes this rubric extremely heterogeneous, making further research difficult [1]. nine0087 According to DSM-V, the following features of bipolar disorder are distinguished:

• with anxiety distress;

• with mixed features;

• with fast cycles;

• with psychotic symptoms congruent to mood;

• with psychotic symptoms incongruent to mood;

• with catatonic inclusions;

• with peripartum onset;

• seasonal: refers only to the pattern of major depressive episodes [2].

By seasonality we mean the regular seasonal pattern of at least one type of episode (i.e. mania, hypomania or depression). Other types of episodes may not follow this pattern. nine0080

DSM-V seasonality criteria are considered to be:

A. A regular temporal relationship between the onset of manic, hypomanic or major depressive episodes and at certain times of the year (for example, autumn or winter) in bipolar type I and type II disorder.

Note: this does not include cases in which there is a clear effect of psychosocial seasonal stressors (eg regular unemployment every winter).

B. Complete remissions (or transition from major depression to mania or hypomania, or vice versa) that occur at specific times of the year (for example, depression disappears in the spring). nine0087 C. During the past 2 years, manic, hypomanic, or depressive episodes have been temporally seasonal, as defined above, and episodes of this polarity have not occurred out of season during this 2-year period.

D. Seasonal manias, hypomanias, or depressions outnumber any seasonal manias, hypomanias, or depressions that could occur during a person's lifetime [2].

An essential feature is the onset and course of major depressive episodes at characteristic times of the year. In most cases, episodes begin in the fall or winter and pass in the spring. Less commonly, recurrent summer depressive episodes may occur. nine0087 Major depressive episodes are often characterized by decreased energy, hypersomnia, binge eating, weight gain, and carbohydrate cravings, bringing seasonal affective disorder closer to atypical depression.

Within group bipolar disorder, seasonal patterns appear to be more likely in bipolar II than in bipolar I.

The prevalence of seasonality of the winter type of pattern may vary depending on latitude, age and gender. The prevalence of the disease increases at higher latitudes. Age is also a strong predictor of seasonality, with younger people at higher risk for winter depressive episodes. The prevalence of seasonal affective disorder in the United States ranges from 1.5 to 9% depending on the latitude, in Canada it is up to 5%, in the UK - up to 2%. There are no statistical data for Ukraine, which is primarily due to the lack of the possibility of diagnosing seasonality in affective disorders [3].

The most common seasonal affective disorders are women, the female:male ratio in this case is 9:2.

Etiological theories primarily include various genetic theories, such as polymorphism in the ARNTL gene, polymorphism in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), which disrupts circadian rhythms and causes seasonal patterns of affective disorders. Genetic predisposition becomes a more significant factor in the presence of an unfavorable environment [4]. nine0087 One of the most frequently discussed pathogenetic theories of bipolar disorder is the theory of desynchronosis (D.F. Kripke). The essence of the theory is that the seasonally dependent course of depression can be associated with early evolutionary biological forms of expression of seasonally related rhythms of behavior, which are explained by photoperiodic mechanisms. And given the dependence of the occurrence of seasonal affective disorders on geographical latitude, the study of seasonal patterns of affective disorders in the conditions of the northern regions becomes relevant [5]. nine0087 Interesting results were obtained in a number of works by T.L. Kot et al. They found that the presence of peaks of exacerbations of endogenous depressions in the winter-summer period in residents of the northern regions can be explained by the presence of pronounced photodesynchronosis during light deprivation in winter and "light pollution" during the "white nights" period and, given the low functional activity of the epiphysis in the summer period, a decrease endogenous antidepressant effect on the central nervous system, modulated by melatonin, the secretion of which decreases in summer [6].

Genetic predisposition becomes a more significant factor in the presence of an unfavorable environment [4]. nine0087 One of the most frequently discussed pathogenetic theories of bipolar disorder is the theory of desynchronosis (D.F. Kripke). The essence of the theory is that the seasonally dependent course of depression can be associated with early evolutionary biological forms of expression of seasonally related rhythms of behavior, which are explained by photoperiodic mechanisms. And given the dependence of the occurrence of seasonal affective disorders on geographical latitude, the study of seasonal patterns of affective disorders in the conditions of the northern regions becomes relevant [5]. nine0087 Interesting results were obtained in a number of works by T.L. Kot et al. They found that the presence of peaks of exacerbations of endogenous depressions in the winter-summer period in residents of the northern regions can be explained by the presence of pronounced photodesynchronosis during light deprivation in winter and "light pollution" during the "white nights" period and, given the low functional activity of the epiphysis in the summer period, a decrease endogenous antidepressant effect on the central nervous system, modulated by melatonin, the secretion of which decreases in summer [6]. nine0087 So, with affective disorders, disturbances of circadian rhythms are noted not only of melatonin, but also of others: behavioral (sleep-wakefulness, vital rhythm of activity), physiological (for example, body temperature), endocrine (melatonin, cortisol, thyroid hormones, prolactin, somatotropin ).

nine0087 So, with affective disorders, disturbances of circadian rhythms are noted not only of melatonin, but also of others: behavioral (sleep-wakefulness, vital rhythm of activity), physiological (for example, body temperature), endocrine (melatonin, cortisol, thyroid hormones, prolactin, somatotropin ).

On the one hand, the level of melatonin is a biological marker of depression, on the other hand, sleep-wake rhythm disturbances can provoke depressive disorders. Desynchronosis should include forced and permanent disturbances in the rhythm of sleep-wakefulness, for example, during long flights, during the night nature of work. It is believed that desynchronosis is a significant risk factor for affective disorders. nine0087 Causal links between serotonin, melatonin, circadian rhythms, vitamin D and seasonal affective disorders have not yet been confirmed from the standpoint of evidence-based medicine. However, associations between these key factors are present and continue to be explored.

In our clinical practice, we found it convenient to use the data of V.E. Medvedev, who, in case of seasonal affective disorders, distinguishes two types of depression with a different somatovegetative complex and a stereotype of the course. It is appropriate to consider a special personal predisposition represented by hypochondriacal or neuropathic diathesis with sensitivity to weather and climatic conditions as a factor in the development of seasonality of affective disorders and the dominance of the somatovegetative symptom complex in the structure of depression. nine0087 Both traditional pharmacotherapy and non-pharmacological methods of treatment are used as the main methods of treatment for BAD with a seasonal pattern. Here, cognitive-behavioral therapy and light therapy (bright white or narrow blue light) are favored, which, according to the results of several randomized clinical trials, show comparable effectiveness.

CBT, phototherapy, vitamin D, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and melatonergic antidepressants are indicated as prevention. nine0087 The seasonal pattern of affective disorders can be comorbid with other disorders such as attention deficit disorder, alcohol dependence, eating disorders, making it difficult to diagnose. In addition, seasonality of affective disorders can be combined with hypothyroidism, especially in endemic regions, while hypothyroidism can mask the symptoms of seasonality. We must also include shift workers, such as nurses, as a risk group, since this disorder can be caused by limited exposure to sunlight. nine0087 Another topical problem is atypical depression. Depending on the inclusion and sampling criteria, the prevalence of atypical depressive disorders ranges from 15 to 36% [7-10]. This is partly explained by the data of A.V. Serdyuk and others, according to which any "deviations" from the classical clinical picture of depression are considered as a reason to refute the diagnosis of an affective disorder. Depressive states in such cases are often classified in other headings [11].

nine0087 The seasonal pattern of affective disorders can be comorbid with other disorders such as attention deficit disorder, alcohol dependence, eating disorders, making it difficult to diagnose. In addition, seasonality of affective disorders can be combined with hypothyroidism, especially in endemic regions, while hypothyroidism can mask the symptoms of seasonality. We must also include shift workers, such as nurses, as a risk group, since this disorder can be caused by limited exposure to sunlight. nine0087 Another topical problem is atypical depression. Depending on the inclusion and sampling criteria, the prevalence of atypical depressive disorders ranges from 15 to 36% [7-10]. This is partly explained by the data of A.V. Serdyuk and others, according to which any "deviations" from the classical clinical picture of depression are considered as a reason to refute the diagnosis of an affective disorder. Depressive states in such cases are often classified in other headings [11].

The rubric "atypical depression" includes various depressive conditions characterized by reactive mood changes, sensitivity to interpersonal contacts (painful reaction to criticism or rejection by other people), inverted autonomic-somatic symptoms, such as increased appetite and hypersomnia. nine0087 Thus, in accordance with the DSM-V criteria, the diagnosis of atypical depression requires that the current criteria for a major depressive episode be met, and there must also be: 1) mood reactivity - the ability to experience at least 50% improvement in mood after exposure to a positive event, as well as more at least two other criteria; 2) increased drowsiness - sleep duration more than 10 hours a day; 3) "lead paralysis" - a feeling of heaviness in the limbs; 4) hyperphagia - increased appetite or weight gain; 5) refusal of interpersonal sensitivity - increased sensitivity to criticism or refusal as a result of functional disorders from interpersonal contacts [2]. nine0003

nine0087 Thus, in accordance with the DSM-V criteria, the diagnosis of atypical depression requires that the current criteria for a major depressive episode be met, and there must also be: 1) mood reactivity - the ability to experience at least 50% improvement in mood after exposure to a positive event, as well as more at least two other criteria; 2) increased drowsiness - sleep duration more than 10 hours a day; 3) "lead paralysis" - a feeling of heaviness in the limbs; 4) hyperphagia - increased appetite or weight gain; 5) refusal of interpersonal sensitivity - increased sensitivity to criticism or refusal as a result of functional disorders from interpersonal contacts [2]. nine0003

In our clinical practice, we are increasingly confronted with patients with bipolar disorder, in whom depressive episodes are diagnosed in the autumn-winter period, and hypomanic and manic episodes in the spring and summer.

Based on the foregoing, the main issues of diagnosing and treating BAD, promising for in-depth study, should be considered:

- development of an algorithm for interaction with primary care in order to increase the level of knowledge of general practitioners on BAD problems; nine0087 - strengthening the evidence base for diagnosing bipolar disorder, including atypical and with a seasonal pattern, as well as monitoring in this area;

- development and implementation in the practice of primary care physicians of simple and reliable standardized tools for the detection of bipolar spectrum disorders;

- prevention of this disorder in risk groups, primarily among people employed in shift work;

- clarification of the modern clinical structure of atypical depression;

- development of diagnostic tools for the detection of atypical and seasonal depressions, selection of criteria for their differentiation from non-circular depressions and bipolar disorder. nine0087 These issues are of particular importance in connection with the preparation of a new international classification of diseases (ICD-11), as discussions are underway to include BAD type II in it, the manifestation of which is considered to be atypical and seasonal depression.

nine0087 These issues are of particular importance in connection with the preparation of a new international classification of diseases (ICD-11), as discussions are underway to include BAD type II in it, the manifestation of which is considered to be atypical and seasonal depression.

References are under revision.

27.12.2022 PsychiatryTenoten in treating neurotic disorders

Neurotic, stress-associated and somatoform disorders (F40-F48) are the most widespread disorders of mental health in the practice of primary care physicians.