Schizophrenia environmental causes

[Environmental risk factors for schizophrenia: a review]

Review

. 2013 Feb;39(1):19-28.

doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2011.12.007. Epub 2012 Nov 21.

[Article in French]

J Vilain 1 , A-M Galliot, J Durand-Roger, M Leboyer, P-M Llorca, F Schürhoff, A Szöke

Affiliations

Affiliation

- 1 Inserm U 955, équipe de psychiatrie génétique, département de génomique médicale, institut Mondor de recherches biomédicales (IMRB), 94000 Créteil, France. [email protected]

- PMID: 23177330

- DOI: 10.

1016/j.encep.2011.12.007

Review

[Article in French]

J Vilain et al. Encephale. 2013 Feb.

. 2013 Feb;39(1):19-28.

doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2011.12.007. Epub 2012 Nov 21.

Authors

J Vilain 1 , A-M Galliot, J Durand-Roger, M Leboyer, P-M Llorca, F Schürhoff, A Szöke

Affiliation

- 1 Inserm U 955, équipe de psychiatrie génétique, département de génomique médicale, institut Mondor de recherches biomédicales (IMRB), 94000 Créteil, France. [email protected]

- PMID: 23177330

- DOI: 10.

1016/j.encep.2011.12.007

1016/j.encep.2011.12.007

Abstract

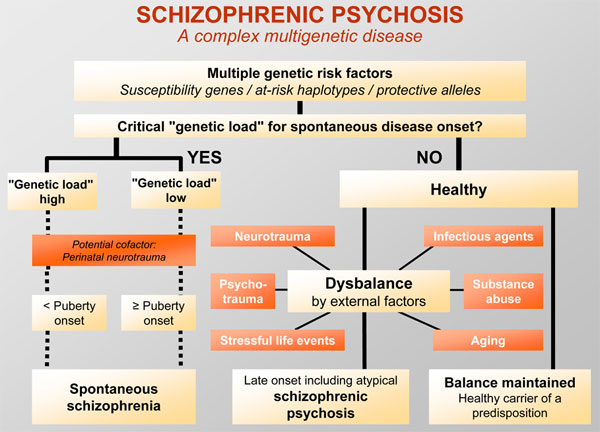

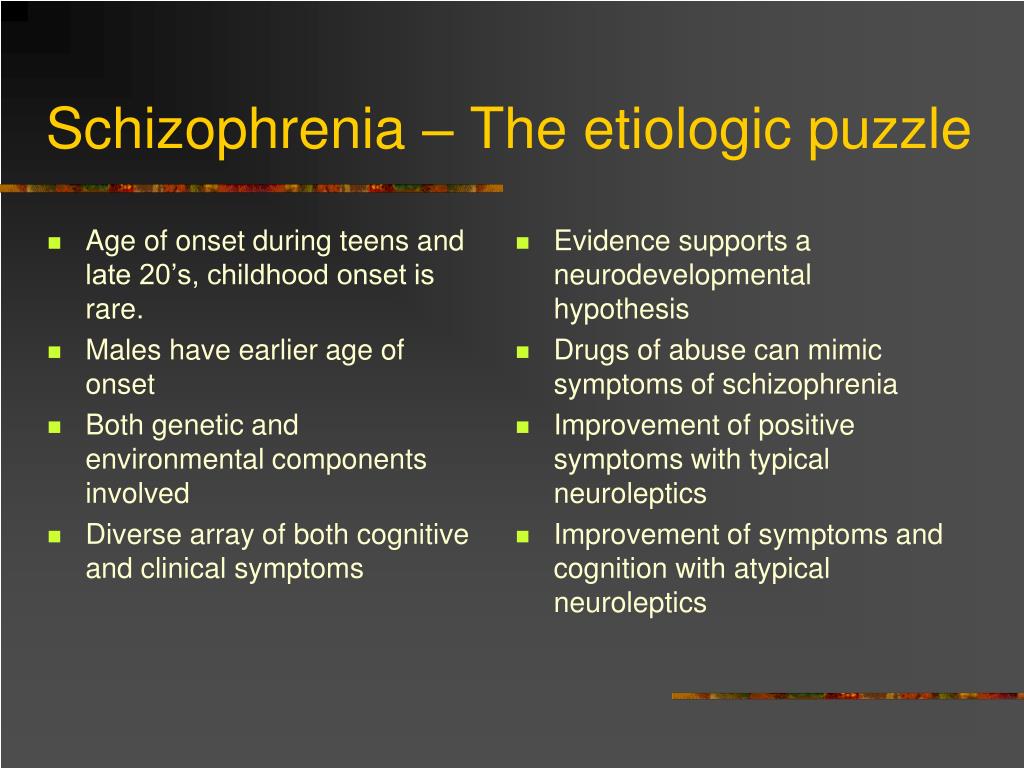

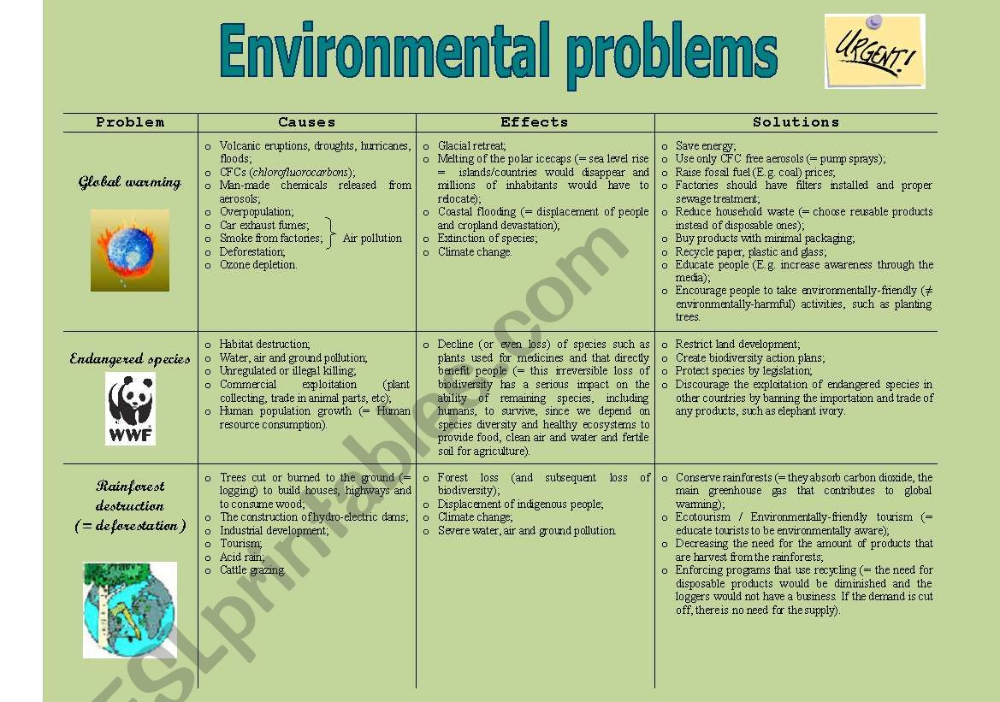

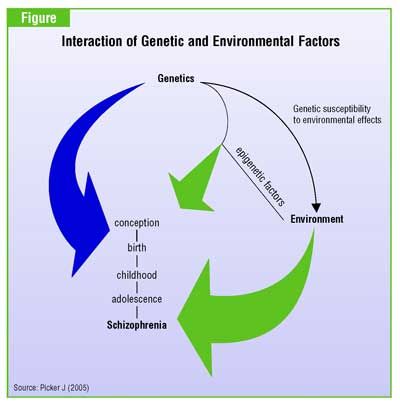

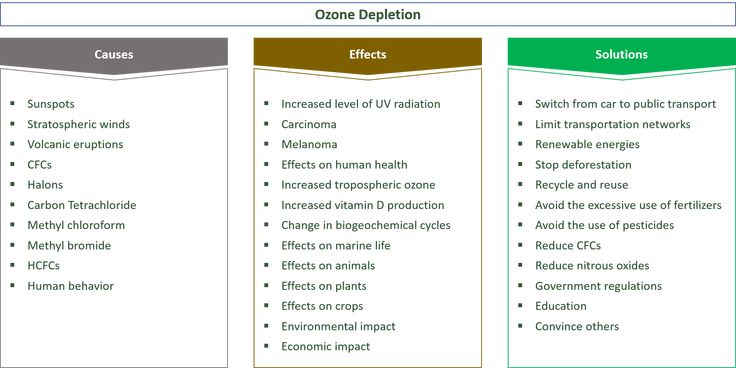

Background: Evidence of variations in schizophrenia incidence rates has been found in genetically homogenous populations, depending on changes within time or space of certain environmental characteristics. The consideration of the impact of environmental risk factors in etiopathogenic studies has put the environment in the forefront of research regarding psychotic illnesses. Various environmental factors such as urbanicity, migration, cannabis, childhood traumas, infectious agents, obstetrical complications and psychosocial factors have been associated with the risk of developing schizophrenia. These risk factors can be biological, physical, psychological as well as social and may operate at different times in an individual's life (fetal period, childhood, adolescence and early adulthood). Whilst some of these factors act on an individual level, others act on a populational level, modulating the individual risk. These factors can have a direct action on the development of schizophrenia, or on the other hand act as markers for directly implicated factors that have not yet been identified.

These factors can have a direct action on the development of schizophrenia, or on the other hand act as markers for directly implicated factors that have not yet been identified.

Literature findings: This article summarizes the current knowledge on this subject. An extensive literature search was conducted via the search engine Pubmed. Eight risk factors were selected and developed in the following paper: urbanicity (or living in an urban area), cannabis, migration (and ethnic density), obstetrical complications, seasonality of birth, infectious agents (and inflammatory responses), socio-demographic factors and childhood traumas. For each of these factors, we provide information on the importance of the risk, the vulnerability period, hypotheses made on the possible mechanisms behind the factors and the level of proof the current research offers (good, medium, or insufficient) according to the amount, type, quality and concordance of the studies at hand. Some factors, such as cannabis, are "unique" in their influence on the development of schizophrenia since it labels only one risk factor. Others, such as obstetrical complications, are grouped (or "composed") in that they include various sub-factors that can influence the development of schizophrenia.

Some factors, such as cannabis, are "unique" in their influence on the development of schizophrenia since it labels only one risk factor. Others, such as obstetrical complications, are grouped (or "composed") in that they include various sub-factors that can influence the development of schizophrenia.

Discussion: The data reviewed clearly demonstrates that environmental factors have an influence on the risk of developing schizophrenia. For certain factors - cannabis, migration, urbanicity, obstetrical complications, seasonality - there is enough evidence to establish an association with the risk of schizophrenia. This association, however, remains weak (especially for seasonality). With the exception of cannabis, no direct link can yet be established. Concerning the three remaining factors - childhood traumas, infectious agents, socio-demographic factors - the available proof is insufficient. One main limitation concerning all environmental factors is the generalization of results due to the fact that the studies were conducted on geographically limited populations. The current state of knowledge does not allow us to determine the mechanisms by which these factors may act.

The current state of knowledge does not allow us to determine the mechanisms by which these factors may act.

Conclusion: Further research is needed to fill the gaps in our understanding of the subject. In response to this need, a collaborative European project (European Study of Gene-Environment Interactions [EU GEI]) was set-up. This study proposes the analysis of those environmental factors that influence the incidence of schizophrenia in various European countries, in both rural and urban settings, migrant and native populations, as well as their interaction with genetic factors.

Copyright © 2011 L'Encéphale, Paris. Published by Elsevier Masson SAS. All rights reserved.

Similar articles

-

[Epidemiology of schizophrenic disorders, genetic and environmental risk factors].

Szoke A. Szoke A. Rev Prat. 2013 Mar;63(3):331-5. Rev Prat. 2013. PMID: 23687754 French.

-

[Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a consequence of the interaction between an individual genetic susceptibility, a traumatogenic event and a social context].

Auxéméry Y. Auxéméry Y. Encephale. 2012 Oct;38(5):373-80. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2011.12.003. Epub 2012 Jan 24. Encephale. 2012. PMID: 23062450 Review. French.

-

Schizophrenia and urbanicity: a major environmental influence--conditional on genetic risk.

Krabbendam L, van Os J. Krabbendam L, et al. Schizophr Bull. 2005 Oct;31(4):795-9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi060. Epub 2005 Sep 8. Schizophr Bull. 2005. PMID: 16150958 Review.

-

Individuals, schools, and neighborhood: a multilevel longitudinal study of variation in incidence of psychotic disorders.

Zammit S, Lewis G, Rasbash J, Dalman C, Gustafsson JE, Allebeck P. Zammit S, et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Sep;67(9):914-22. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.101. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010. PMID: 20819985

-

Schizophrenia and city residence.

Freeman H. Freeman H. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1994 Apr;(23):39-50. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1994. PMID: 8037900 Review.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

Advantages and Limitations of Animal Schizophrenia Models.

Białoń M, Wąsik A. Białoń M, et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 May 25;23(11):5968. doi: 10.3390/ijms23115968. Int J Mol Sci. 2022. PMID: 35682647 Free PMC article. Review.

-

Gene-Environment Interactions in Schizophrenia: A Literature Review.

Wahbeh MH, Avramopoulos D. Wahbeh MH, et al. Genes (Basel). 2021 Nov 23;12(12):1850. doi: 10.3390/genes12121850. Genes (Basel). 2021. PMID: 34946799 Free PMC article. Review.

-

Long-Acting Risperidone Dual Control System: Preparation, Characterization and Evaluation In Vitro and In Vivo.

Yan X, Wang S, Sun K. Yan X, et al. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Aug 5;13(8):1210. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13081210. Pharmaceutics. 2021. PMID: 34452171 Free PMC article.

-

Descriptive study of cases of schizophrenia in the Malian population.

Coulibaly SDP, Ba B, Mounkoro PP, Diakite B, Kassogue Y, Maiga M, Dara AE, Traoré J, Kamaté Z, Traoré K, Koné M, Maiga B, Diarra Z, Coulibaly S, Togora A, Maiga Y, Koumaré B. Coulibaly SDP, et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2021 Aug 20;21(1):413. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03422-9. BMC Psychiatry. 2021. PMID: 34416862 Free PMC article.

-

Oral health treatment habits of people with schizophrenia in France: A retrospective cohort study.

Denis F, Goueslard K, Siu-Paredes F, Amador G, Rusch E, Bertaud V, Quantin C. Denis F, et al. PLoS One. 2020 Mar 9;15(3):e0229946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229946. eCollection 2020. PLoS One. 2020. PMID: 32150582 Free PMC article.

See all "Cited by" articles

Publication types

MeSH terms

Environmental risk factors for psychosis

1. Bleuler E. Section IX: The causes of the disease. In: Zinkin J, trans-ed. Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias. New York, NY: International Universities Press Inc; 1950 [Google Scholar]

2. Kraepelin E. Frequency and causes. In: Barclay RM, trans-ed. Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia. Edinburgh, UK: E&S Livingstone; 1919 [Google Scholar]

3. Cardno AG., Marshall EJ., Coid B., et al. Heritability estimates for psychotic disorders: the Maudsley twin psychosis series. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:162–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Tsuang MT., Stone WS., Faraone SV. Genes, environment and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2001;40:s18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. van Os J., Sham P. Gene-environment correlation and interaction in schizophrenia. In: Murray RM, Jones PB, Susser E, van Os J, Cannon M, eds. The Epidemiology of Schizophrenia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003:235–253. [Google Scholar]

6. Murray RM., Lewis SW. Is schizophrenia a neurodevelopmental disorder? BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1987;295:681–682. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Cannon M., Tarrant CJ., Huttunen MO., Jones P. Childhood development and later schizophrenia: evidence from genetic high-risk and birth cohort studies. In: Murray RM, Jones P, Susser E, van Os J, Cannon M, eds. The Epidemiology of Schizophrenia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003:100–123. [Google Scholar]

8. Wright IC., Rabe-Hesketh S., Woodruff PW., David AS., Murray RM., BuIImore ET. Meta-analysis of regional brain volumes in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:16–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. McGrath J., EI-Saadi O., Grim V., et al. Minor physical anomalies and quantitative measures of the head and face in patients with psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:458–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McGrath J., EI-Saadi O., Grim V., et al. Minor physical anomalies and quantitative measures of the head and face in patients with psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:458–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Rosanoff A., Handy L., Plesset I., Brush S. The etiology of so-called schizophrenic psychoses: with special reference to their occurrence in twins. Am J Psychiatry. 1934;91:247–286. [Google Scholar]

11. Arseneault L., Cannon M., Poulton R., Murray R., Caspi A., Moffitt TE. Cannabis use in adolescence and risk for adult psychosis: longitudinal prospective study. BMJ. 2002;325:1212–1213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Rosso IM., Cannon TD., Huttunen T., Huttunen MO., Lonnqvist J., Gasperoni TL. Obstetric risk factors for early-onset schizophrenia in a Finnish birth cohort. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:801–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Verdoux H., Geddes JR., Takei N., et al. Obstetric complications and age at onset in schizophrenia: an international collaborative meta-analysis of individual patient data. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1220–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1220–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. McNeil TF., Cantor-Graae E., Weinberger DR. Relationship of obstetric complications and differences in size of brain structures in monozygotic twin pairs discordant for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:203–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Cannon TD., van Erp TG., Rosso IM., et al. Fetal hypoxia and structural brain abnormalities in schizophrenic patients, their siblings, and controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Stefanis N., Frangou S., Yakeley J., et al. Hippocampal volume reduction in schizophrenia: effects of genetic risk and pregnancy and birth complications. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:697–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Cantor-Graae E., Ismail B., McNeil TF. Are neurological abnormalities in schizophrenic patients and their siblings the result of perinatal trauma? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:142–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. O'Callaghan E., Larkin C., Kinsella A., Waddington JL. Obstetric complications, the putative familial-sporadic distinction, and tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:578–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Cannon TD., Rosso IM., HoIIïster JM., Bearden CE., Sanchez LE., Hadley T. A prospective cohort study of genetic and perinatal influences in the etiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:351–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Harrison PJ., Owen MJ. Genes for schizophrenia? Recent findings and their pathophysiological implications. Lancet. 2003;361:417–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Fearon P., Cotter P., Murray RM. Is the association between obstetric complications and schizophrenia mediated by glutaminergic excitotoxic damage in the foetal/neonatal brain? In: Reveley M, Deacon B, ed. Psychopharmacology of Schizophrenia. London, UK: Chapman and Hall; 2000:21–40. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

22. Fearon P., O'Connell P., Frangou S., et al. Brain volumes in adult survivors of very low birth weight: a sibling-controlled study. Pediatrics. 2004;114:367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Nosarti C., AI-Asady MH., Frangou S., Stewart AL., Rifkin L., Murray RM. Adolescents who were born very preterm have decreased brain volumes. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 7):1616–1623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Bradbury TN., Miller GA. Season of birth in schizophrenia: a review of evidence, methodology, and etiology. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:569–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. McGrath JJ., Welham JL. Season of birth and schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of data from the Southern Hemisphere. Schizophr Res. 1999;35:237–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Davies G., Welham J., Chant D., Torrey EF., McGrath J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of Northern Hemisphere season of birth studies in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:587–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:587–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Torrey EF., Miller J., Rawlings R., Yolken RH. Seasonality of births in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Schizophr Res. 1997;28:1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Bagalkote H., Pang D., Jones PB. Maternal influenza and schizophrenia. Int J Ment Health. 2001;29:3–21. [Google Scholar]

29. Brown AS. Prenatal infection and adult schizophrenia: a review and synthesis, int J Ment Health. 2001;29:22–37. [Google Scholar]

30. Dean K., Bramon E., Murray RM. The causes of schizophrenia: neurodevelopmental and other risk factors. J Psychiatr Pract. 2003;9:442–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Mednick SA., Machon RA., Huttunen MO., Bonett D. Adult schizophrenia following prenatal exposure to an influenza epidemic. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:189–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Takei N., Mortensen PB., Klaening U. , et al. Relationship between in utero exposure to influenza epidemics and risk of schizophrenia in Denmark. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:817–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

, et al. Relationship between in utero exposure to influenza epidemics and risk of schizophrenia in Denmark. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:817–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Westergaard T., Mortensen PB., Pedersen CB., Wohlfahrt J., Melbye M. Exposure to prenatal and childhood infections and the risk of schizophrenia: suggestions from a study of sibship characteristics and influenza prevalence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:993–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Torrey EF., Bowler AE., Rawlings R. Schizophrenia and the 1957 influenza epidemic. Schizophr Res. 1992;6:100. [Google Scholar]

35. Limosin F., Rouillon F., Payan C., Cohen JM., Strub N. Prenatal exposure to influenza as a risk factor for adult schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Cannon M KR., Susser E., Jones P. Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for schizophrenia. In: Murray R, Jones PB, Susser E, Van Os J, Cannon M, eds. The Epidemiology of Schizophrenia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003:74–99. [Google Scholar]

The Epidemiology of Schizophrenia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003:74–99. [Google Scholar]

37. Crow TJ., Done DJ. Prenatal exposure to influenza does not cause schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:390–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Cannon M., Cotter D., Coffey VP., et al. Prenatal exposure to the 1957 influenza epidemic and adult schizophrenia: a follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:368–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Shi L., Fatemi SH., Sidwell RW., Patterson PH. Maternal influenza infection causes marked behavioral and pharmacological changes in the offspring. J Neurosci. 2003;23:297–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Brown AS., Cohen P., Harkavy-Friedman J., et al. A. E. Bennett Research Award. Prenatal rubella, premorbid abnormalities, and adult schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:473–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Suvisaari J., Haukka J., Tanskanen A. , Hovi T., Lonnqvist J. Association between prenatal exposure to poliovirus infection and adult schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1100–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

, Hovi T., Lonnqvist J. Association between prenatal exposure to poliovirus infection and adult schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1100–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Buka SL., Tsuang MT., Torrey EF., Klebanoff MA., Bernstein D., Yolken RH. Maternal infections and subsequent psychosis among offspring. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:1032–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Brown AS., Begg MD., Gravensteïn S., et al. Serologic evidence of prenatal influenza in the etiology of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:774–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Koponen H., Rantakallio P., Veijola J., Jones P., Jokelainen J., Isohanni M. Childhood central nervous system infections and risk for schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Gattaz WF., Abrahao AL., Foccacia R. Childhood meningitis, brain maturation and the risk of psychosis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254:23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2004;254:23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Torrey EF., Yolken RH. Toxoplasma gondii and schizophrenia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1375–1380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Kinney D. Prenatal stress and risk for schizophrenia. Int J Ment Health. 2001;29:62–72. [Google Scholar]

48. Susser E., Hoek HW., Brown A. Neurodevelopmental disorders after prenatal famine: the story of the Dutch Famine Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:213–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Sacker A., Done DJ., Crow TJ., Golding J. Antecedents of schizophrenia and affective illness. Obstetric complications. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166:734–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. HoIIister JM., Laing P., Mednick SA. Rhesus incompatibility as a risk factor for schizophrenia in male adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. van Os J., Selten JP. Prenatal exposure to maternal stress and subsequent schizophrenia. The May 1940 invasion of The Netherlands. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:324–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The May 1940 invasion of The Netherlands. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:324–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Selten JP., van der Graaf Y., van Duursen R., Gispen-de Wied CC., Kahn RS. Psychotic illness after prenatal exposure to the 1953 Dutch Flood Disaster. Schizophr Res. 1999;35:243–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Huttunen MO., Niskanen P. Prenatal loss of father and psychiatric disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:429–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Selten JP., Cantor-Graae E., Nahon D., Levav I., Aleman A., Kahn RS. No relationship between risk of schizophrenia and prenatal exposure to stress during the Six-Day War or Yom Kippur War in Israel. Schizophr Res. 2003;63:131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Maki P., Veijola J., Rantakallio P., Jokelainen J., Jones PB., Isohanni M. Schizophrenia in the offspring of antenatally depressed mothers: a 31 -year follow-up of the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Schizophr Res. 2004;66:79–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2004;66:79–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Barker DJ. Mothers, Babies and Health in Later Life. Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 1998 [Google Scholar]

57. Brown AS., Susser ES., Butler PD., Richardson Andrews R., Kaufmann CA., Gorman JM. Neurobiological plausibility of prenatal nutritional deprivation as a risk factor for schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996;184:71–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Jones PB., Rantakallio P., Hartikainen AL., Isohanni M., Sipila P. Schizophrenia as a long-term outcome of pregnancy, delivery, and perinatal complications: a 28-year follow-up of the 1966 north Finland general population birth cohort. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:355–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Schaefer CA., Brown AS., Wyatt RJ., et al. Maternal prepregnant body mass and risk of schizophrenia in adult offspring. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:275–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Hoek HW., Brown AS., Susser E. The Dutch famine and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:373–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:373–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Wahlbeck K., Forsen T., Osmond C., Barker DJ., Eriksson JG. Association of schizophrenia with low maternal body mass index, small size at birth, and thinness during childhood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Susser ES., Lin SP. Schizophrenia after prenatal exposure to the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944-1945. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:983–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Susser E., Neugebauer R., Hoek HW., et al. Schizophrenia after prenatal famine. Further evidence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Hulshoff Pol HE., Hoek HW., Susser E., et al. Prenatal exposure to famine and brain morphology in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1170–1172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. McGrath J. Hypothesis: is low prenatal vitamin D a risk-modifying factor for schizophrenia? Schizophr Res. 1999;40:173–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1999;40:173–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. McGrath J., Saari K., Hakko H., et al. Vitamin D supplementation during the first year of life and risk of schizophrenia: a Finnish birth cohort study. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:237–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. McGrath J., Eyles D., Mowry B., Yolken R., Buka S. Low maternal vitamin D as a risk factor for schizophrenia: a pilot study using banked sera. Schizophr Res. 2003;63:73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Ozer S., Ulusahïn A., Ulusoy S., et al. Is vitamin D hypothesis for schizophrenia valid? Independent segregation of psychosis in a family with vitami n-D-dependent rickets type HA. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28:255–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Muntjewerff JW., van der Put N., Eskes T., et al. Homocysteine metabolism and B-vitamins in schizophrenic patients: low plasma folate as a possible independent risk factor for schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2003;121:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Mirsky AF., Silberman EK., Latz A., Nagler S. Adult outcomes of high-risk children: differential effects of town and kibbutz rearing. Schizophr Bull. 1985;11:150–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Cannon M., Caspi A., Moffitt TE., et al. Evidence for early-childhood, pandevelopmental impairment specific to schizophreniform disorder: results from a longitudinal birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:449–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Agid O., Shapira B., Zislin J., et al. Environment and vulnerability to major psychiatric illness: a case control study of early parental loss in major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4:163–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Jones P., Rodgers B., Murray R., Marmot M. Child development risk factors for adult schizophrenia in the British 1946 birth cohort. Lancet. 1994;344:1398–1402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Tïenari P., Wynne LC., Moring J., et al. The Finnish adoptive family study of schizophrenia. Implications for family research. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1994:20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tïenari P., Wynne LC., Moring J., et al. The Finnish adoptive family study of schizophrenia. Implications for family research. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1994:20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Read J., Perry BD., Moskowitz A., Connolly J. The contribution of early traumatic events to schizophrenia in some patients: a traumagenic neurodevelopmental model. Psychiatry. 2001;64:319–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Garety PA., Kuipers E., Fowler D., Freeman D., Bebbington PE. A cognitive model of the positive symptoms of psychosis. Psychol Med. 2001;31:189–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Mullen PE., Martin JL., Anderson JC., Romans SE., Herbison GP. Childhood sexual abuse and mental health in adult life. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:721–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Read J., Argyle N. Hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder among adult psychiatric inpatients with a history of child abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:1467–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Janssen I., Krabbendam L., Bak M., et al. Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Sachdev P. Schizophrenia-like psychosis following traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13:533–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Nielsen AS., Mortensen PB., O'Callaghan E., Mors O., Ewald H. Is head injury a risk factor for schizophrenia? Schizophr Res. 2002;55:93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Wilcox JA., Nasrallah HA. Childhood head trauma and psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 1987;21:303–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. AbdelMalik P., Husted J., Chow EW., Bassett AS. Childhood head injury and expression of schizophrenia in multiply affected families. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:231–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Murray RM., Grech A., Philips P., Johnson S. The relationship between substance abuse and schizophrenia. In: Murray R, Jones PB, Susser E, van Os J, Cannon M, eds. The Epidemiology of Schizophrenia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003:317–342. [Google Scholar]

In: Murray R, Jones PB, Susser E, van Os J, Cannon M, eds. The Epidemiology of Schizophrenia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003:317–342. [Google Scholar]

85. Chen CK., Lin SK., Sham PC., et al. Pre-morbid characteristics and co-morbidity of metamphetamine users with and without psychosis. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1407–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Mathers DC., Ghodse AH. Cannabis and psychotic illness. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:648–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. D'Souza DC., Abi-Saad W., Madonick S., Wray Y., et al. Cannabinoids and psychosis: evidence from studies with iv THC in schizophrenia patients and controls. Schizophr Res. 2000;41 (special issue):33. [Google Scholar]

88. Hall W., Degenhardt L. Is there a specific “cannabis psychosis”? In: Castle DJ, Murray RM, eds. Marijuana and Madness. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]

89. Andreasson S., AHebeck P., Engstrom A. , Rydberg U. Cannabis and schizophrenia. A longitudinal study of Swedish conscripts. Lancet. 1987;2:1483–1486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

, Rydberg U. Cannabis and schizophrenia. A longitudinal study of Swedish conscripts. Lancet. 1987;2:1483–1486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90. Zammit S., AHebeck P., Andreasson S., Lundberg I., Lewis G. Self-reported cannabis use as a risk factor for schizophrenia in Swedish conscripts of 1969: historical cohort study. BMJ. 2002;325:1199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Weiser M., Knobler HY., Noy S., Kaplan Z. Clinical characteristics of adolescents later hospitalized for schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114:949–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Fergusson DM., Horwood LJ., Swain-Campbell NR. Cannabis dependence and psychotic symptoms in young people. Psychol Med. 2003;33:15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. van Os J., Bak M., Hanssen M., Bjjl RV., de Graaf R., Verdoux H. Cannabis use and psychosis: a longitudinal population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:319–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Arseneault L., Cannon M., Witton J., Murray RM. Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arseneault L., Cannon M., Witton J., Murray RM. Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Smit F., Bolier L., Cuypers P. Cannabis use and the risk of later schizophrenia: a review. Addiction. 2004;99:425–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Veen ND., Selten JP., van der Tweel I., Feller WG., Hoek HW., Kahn RS. Cannabis use and age at onset of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:501–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Kapur S. Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: a framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:13–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Lamelle M., Abi-Dargham A., van Dyck CH., et al. Single photon emission computerized tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in drug-free schizophrenic subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9235–9240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Wolf ME., White FJ., Nassar R., et al. Differential development of autoreceptor subsensitivity and enhanced dopamine release during amphetamine sensitisation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;264:249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. Bartlett E., Hallin A., Chapman B., Angrist B. Selective sensitization to the psychosis-inducing effects of cocaine: a possible marker for addiction relapse vulnerability? Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;16:77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101. Berridge KC., Robinson TE. What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;28:309–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Selten JP., Cantor-Graae E. Schizophrenia and migration. In: Gattaz WF, Hafner H, eds. Search for the Causes of Schizophrenia. Berlin, Germany: Steinkopff Verlag; 2004:3–25. [Google Scholar]

103. Kiev A. Psychiatric morbidity of West Indian immigrants in an urban group practice. Br J Psychiatry. 1965;111:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Br J Psychiatry. 1965;111:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Harrison G., Owens D., Holton A., Neilson D., Boot D. A prospective study of severe mental disorder in Afro-Caribbean patients. Psychol Med. 1988;18:643–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Cochrane R., Bal SS. Mental hospital admission rates of immigrants to England: a comparison of 1971 and 1981. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1989;24:2–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Castle D., Wessely S., Der G., Murray RM. The incidence of operationally defined schizophrenia in Camberwell, 1965-84. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:790–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Harrison G., Glazebrook C., Brewin J., et al. Increased incidence of psychotic disorders in migrants from the Caribbean to the United Kingdom. Psychol Med. 1997;27:799–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Mortensen PB., Pedersen CB., Westergaard T., et al. Effects of family history and place and season of birth on the risk of schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:603–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

N Engl J Med. 1999;340:603–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Zolkowska K., Cantor-Graae E., McNeil TF. Increased rates of psychosis among immigrants to Sweden: is migration a risk factor for psychosis? Psychol Med. 2001;31:669–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

110. Sharpley M., Hutchinson G., McKenzie K., Murray RM. Understanding the excess of psychosis among the African-Caribbean population in England. Review of current hypotheses. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2001;40:s60–s68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

111. Hutchinson G., Takei N., Bhugra D., et al. Increased rate of psychosis among African-Caribbeans in Britain is not due to an excess of pregnancy and birth complications. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:145–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112. Boydell J., van Os J., McKenzie K., et al. Incidence of schizophrenia in ethnic minorities in London: ecological study into interactions with environment. BMJ. 2001;323:1336–1338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

113. Mallett R., Leff J., Bhugra D., Pang D., Zhao JH. Social environment, ethnicity and schizophrenia. A case-control study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37:329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mallett R., Leff J., Bhugra D., Pang D., Zhao JH. Social environment, ethnicity and schizophrenia. A case-control study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37:329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

114. Eaton W., Harrison G. Ethnic disadvantage and schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2000:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

115. Freeman H. Schizophrenia and city residence. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1994:39–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

116. Lewis G., David A., Andreasson S., AHebeck P. Schizophrenia and city life. Lancet. 1992;340:137–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

117. Sundquist K., Frank G., Sundquist J. Urbanisation and incidence of psychosis and depression: follow-up study of 4.4 million women and men in Sweden. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

118. Pedersen CB., Mortensen PB. Evidence of a dose-response relationship between urbanicity during upbringing and schizophrenia risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:1039–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2001;58:1039–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

119. Mortensen PB. Urban-rural differences in the risk for schizophrenia, int J Ment Health. 2000;29:101–110. [Google Scholar]

120. Van Os J. Does the urban environment cause psychosis? Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:287–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

121. Harrison G., Gunnell D., Glazebrook C., Page K., Kwiecinski R. Association between schizophrenia and social inequality at birth: case-control study. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:346–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

122. Mulvany F., O'Callaghan E., Takei N., Byrne M., Fearon P., Larkin C. Effect of social class at birth on risk and presentation of schizophrenia: case-control study. BMJ. 2001;323:1398–1401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

123. Byrne M., Agerbo E., Eaton WW., Mortensen PB. Parental socio-economic status and risk of first admission with schizophrenia- a Danish national register-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:87–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2004;39:87–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

124. Van Os J., Drïessen G., Gunther N., Delespaul P. Neighbourhood variation in incidence of schizophrenia. Evidence for personenvironment interaction. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

125. Leff J., Vaughn C. The interaction of life events and relatives' expressed emotion in schizophrenia and depressive neurosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136:146–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

126. Malla AK., Norman RM. Relationship of major life events and daily stressors to symptomatology in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180:664–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

127. Norman RM., Malla AK. Stressful life events and schizophrenia. I: a review of the research. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

128. Castine MR., Meador-Woodruff JH., Dalack GW. The role of life events in onset and recurrent episodes of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32:283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32:283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

129. Ventura J., Nuechterlein KH., Subotnik KL., Hardesty JP., Mintz J. Life events can trigger depressive exacerbation in the early course of schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

130. Heila H., Heikkinen ME., Isometsa ET., Henriksson MM., Marttunen MJ., Lonnqvist JK. Life events and completed suicide in schizophrenia: a comparison of suicide victims with and without schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:519–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

causes, forms, symptoms, signs, stages, diagnosis, treatment

Causes

Classification

Symptoms

Complications

Diagnosis

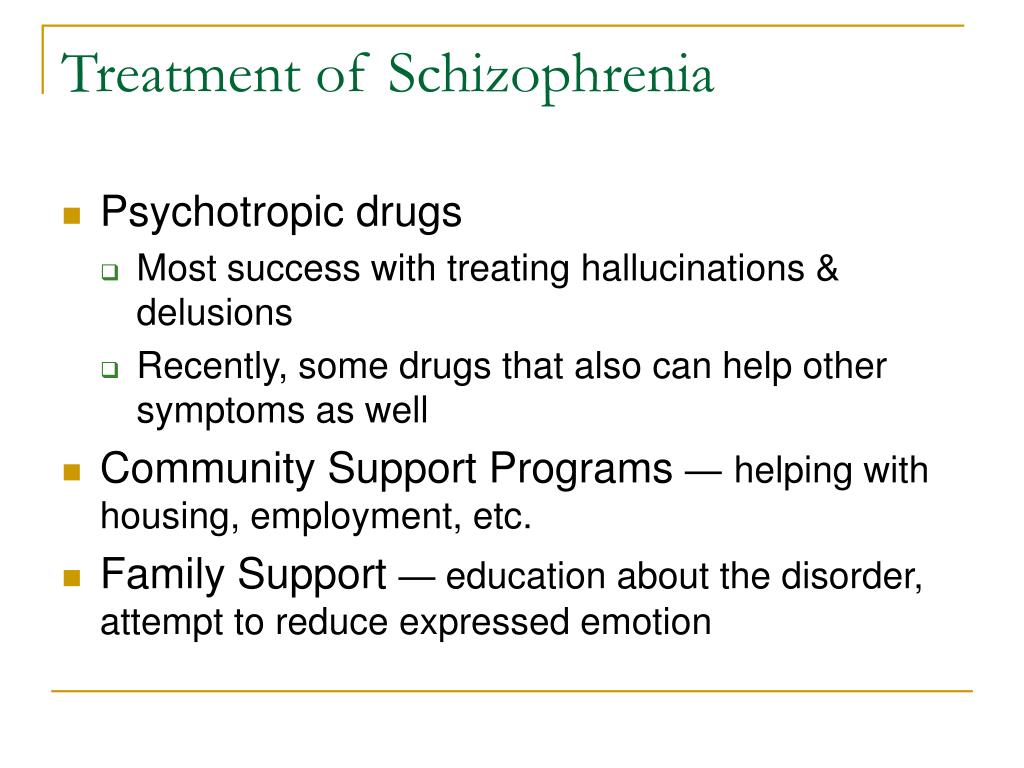

Treatment

Prevention

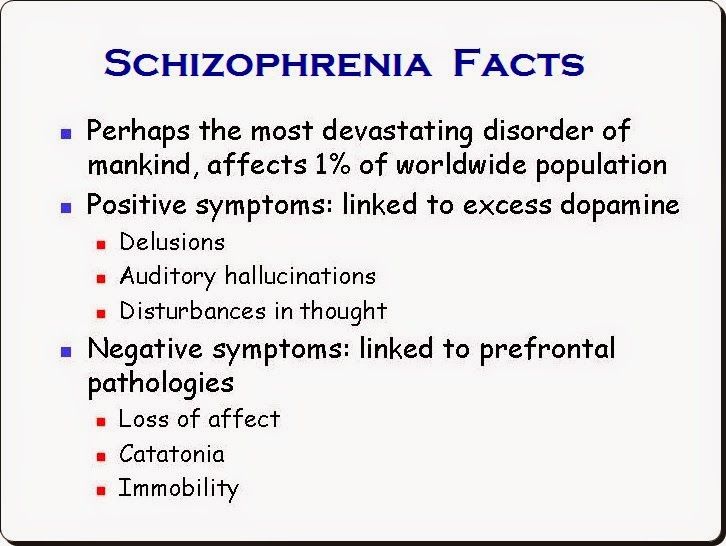

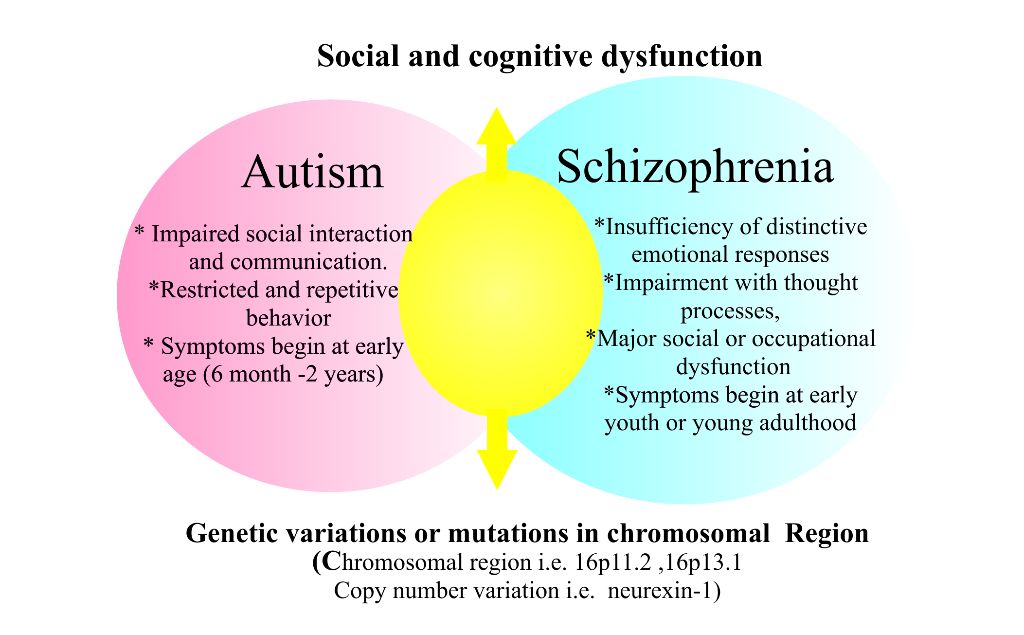

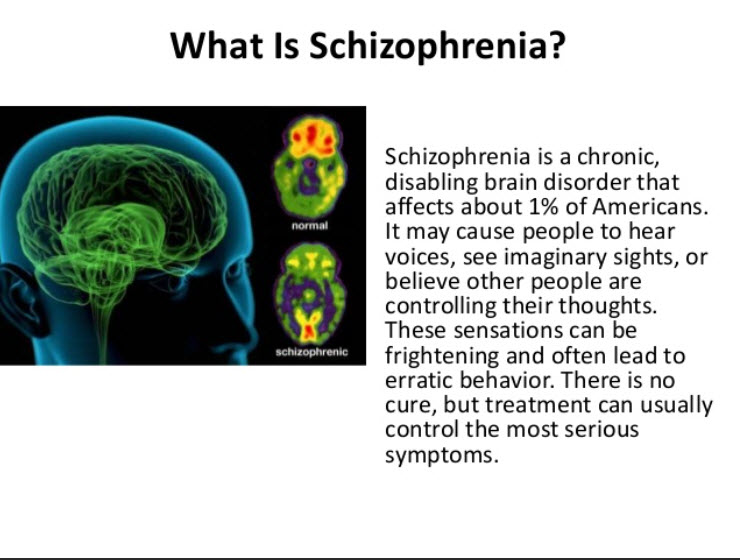

Schizophrenia is a chronic mental disorder characterized by a disturbance in the process of thinking, emotional reactions, and a distorted perception of the outside world.

Without treatment, the disease progresses, the patient's social maladjustment increases, followed by disability. nine0003

nine0003

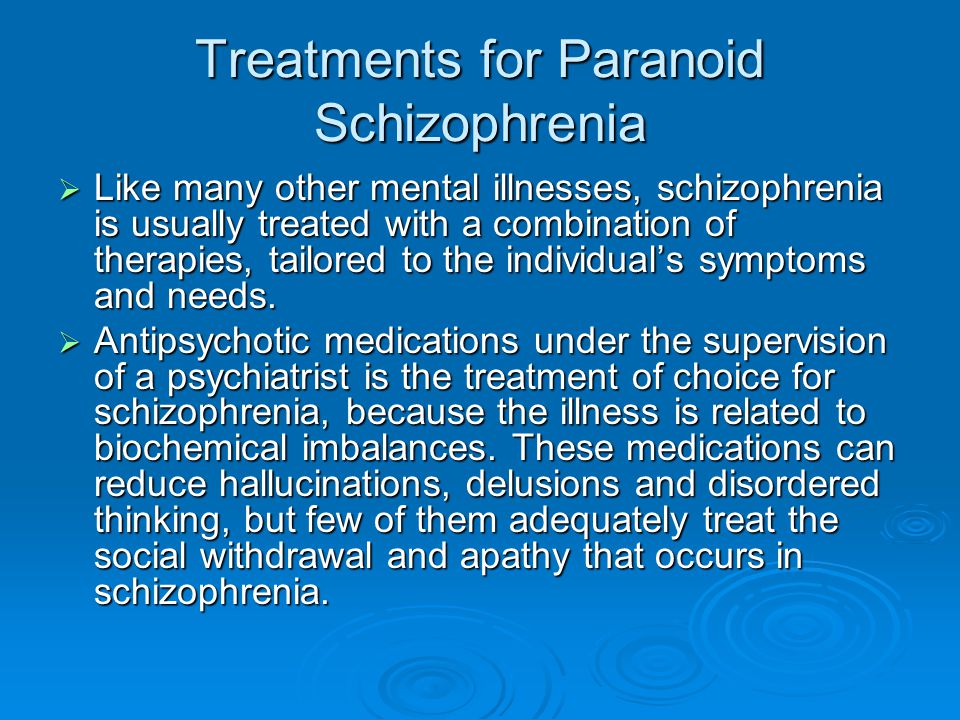

In order to relieve symptoms and establish a long-term remission, drugs are used, psychotherapeutic and physiotherapeutic methods are used.

Causes

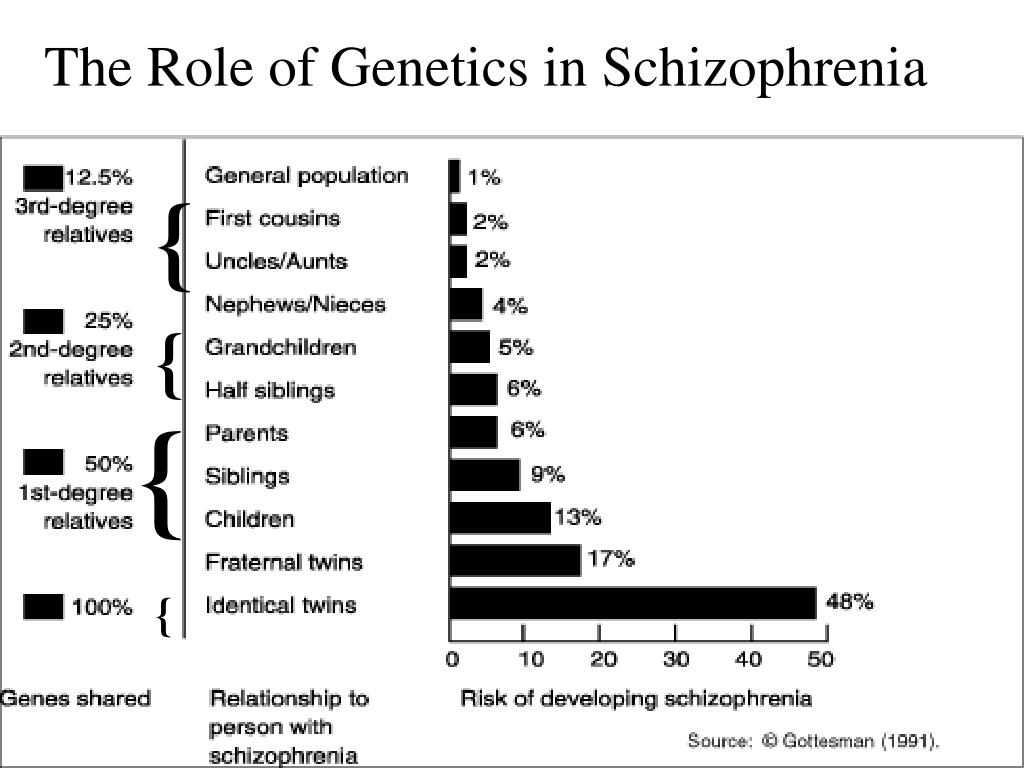

Most scientists adhere to the version that schizophrenia is caused by a whole range of factors, including hereditary burden, adverse social and environmental living conditions.

Predispose to the development of the disease:

- the presence of mental disorders in close relatives; nine0032

- complicated childbirth in the mother;

- past infection or poor nutrition during pregnancy;

- psychological trauma experienced in childhood;

- violation of the laying of a number of brain structures even before birth;

- age from 18 to 30 years.

Schizophrenia in men appears earlier than in women. It is also worth noting that it is more common among urban residents than rural ones. nine0003

nine0003

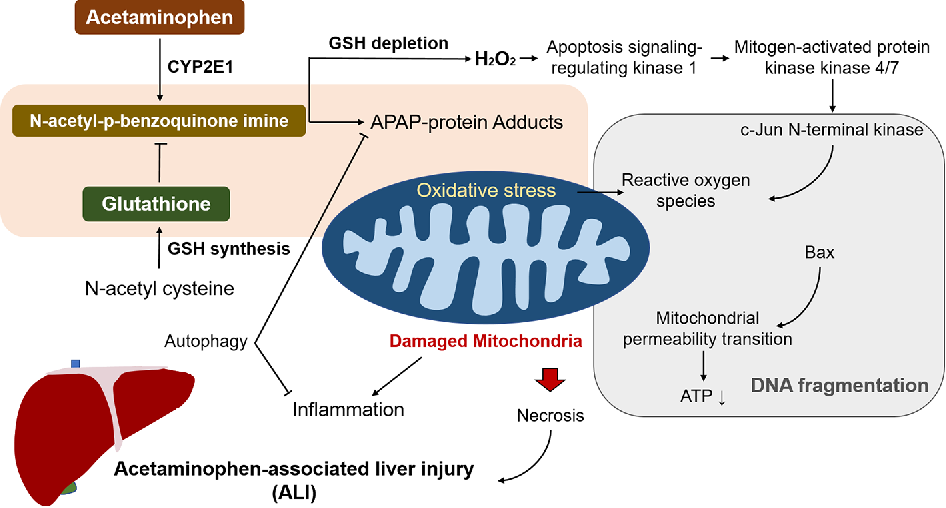

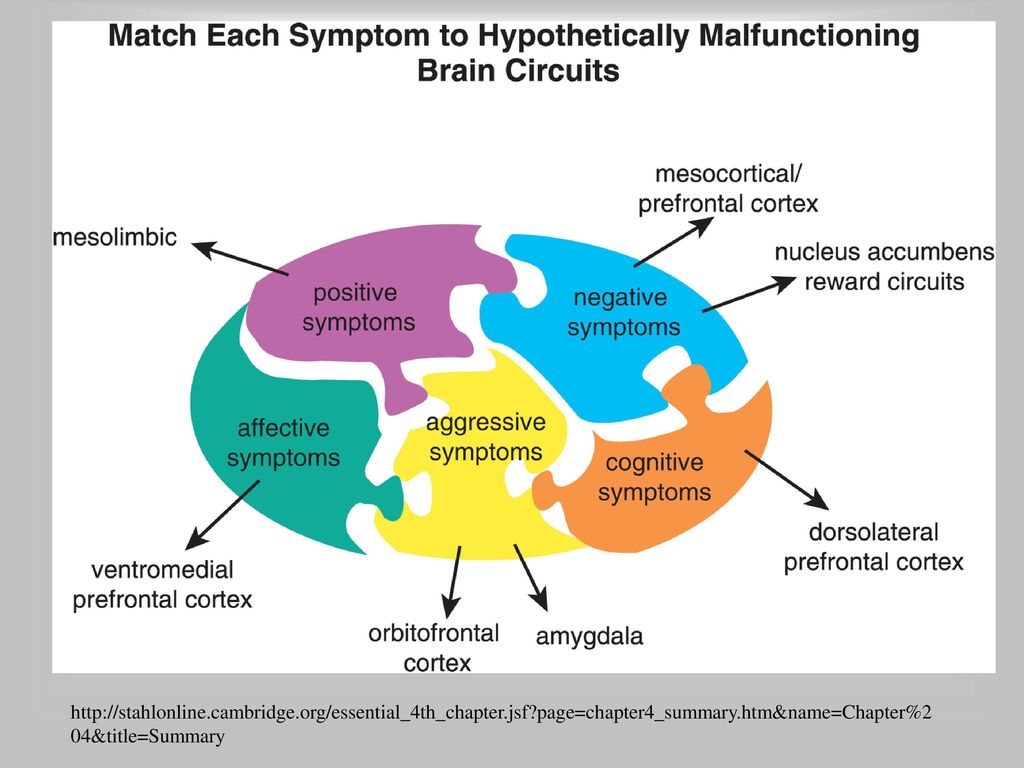

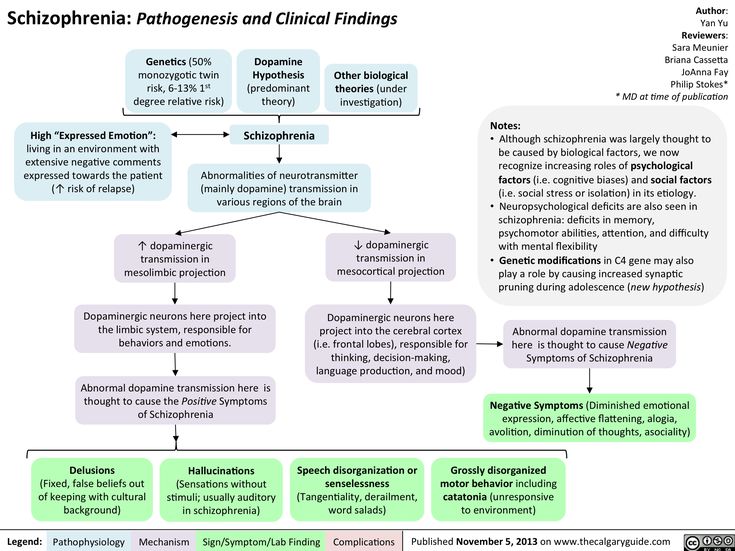

The neurotransmitter theory of the onset of the disease states that, in essence, schizophrenia is a consequence of impaired activity of neurotransmitters in the dopaminergic and glutamatergic synapses of the brain. The debut of the disease is often preceded by a long pathological process in the central nervous system, which lasts for several months or years.

The first psychosis can be provoked by the use of narcotic substances, psycho-emotional shock, prolonged experiences and nervous overload. In women, schizophrenia often manifests during pregnancy or after childbirth. nine0021

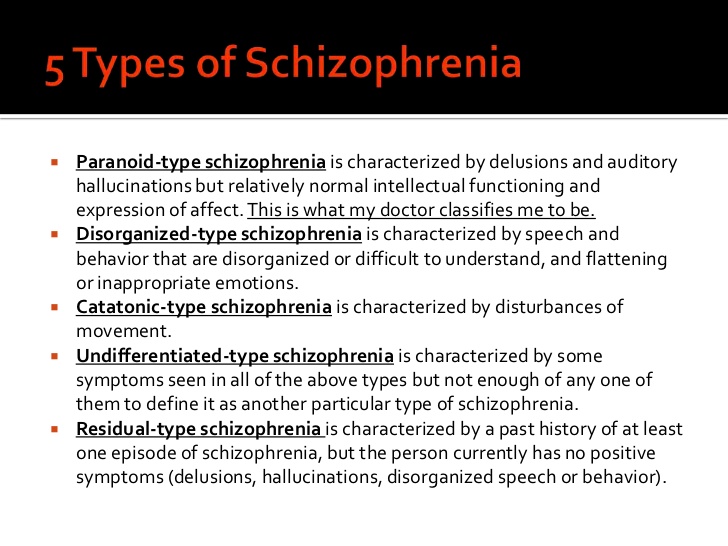

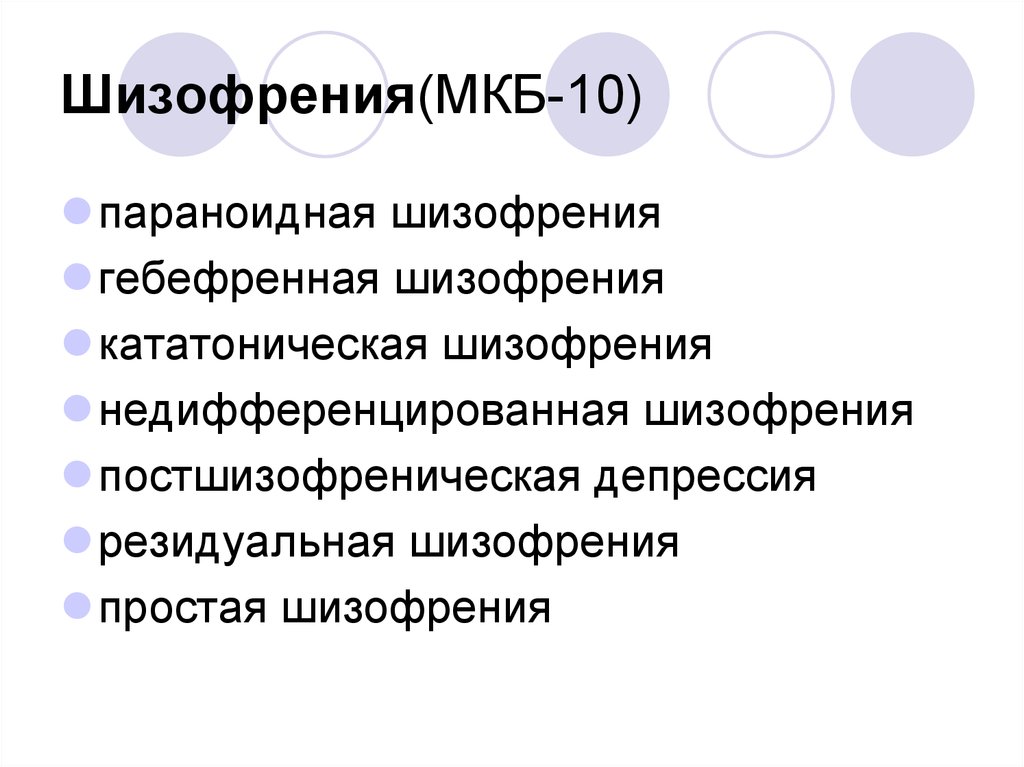

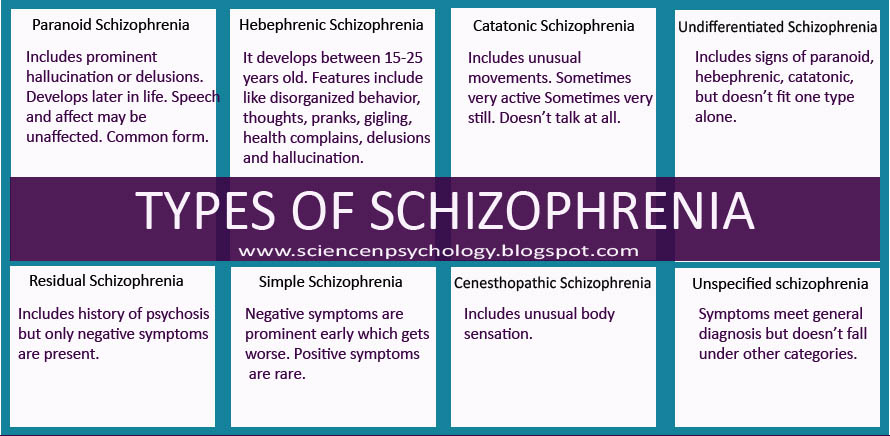

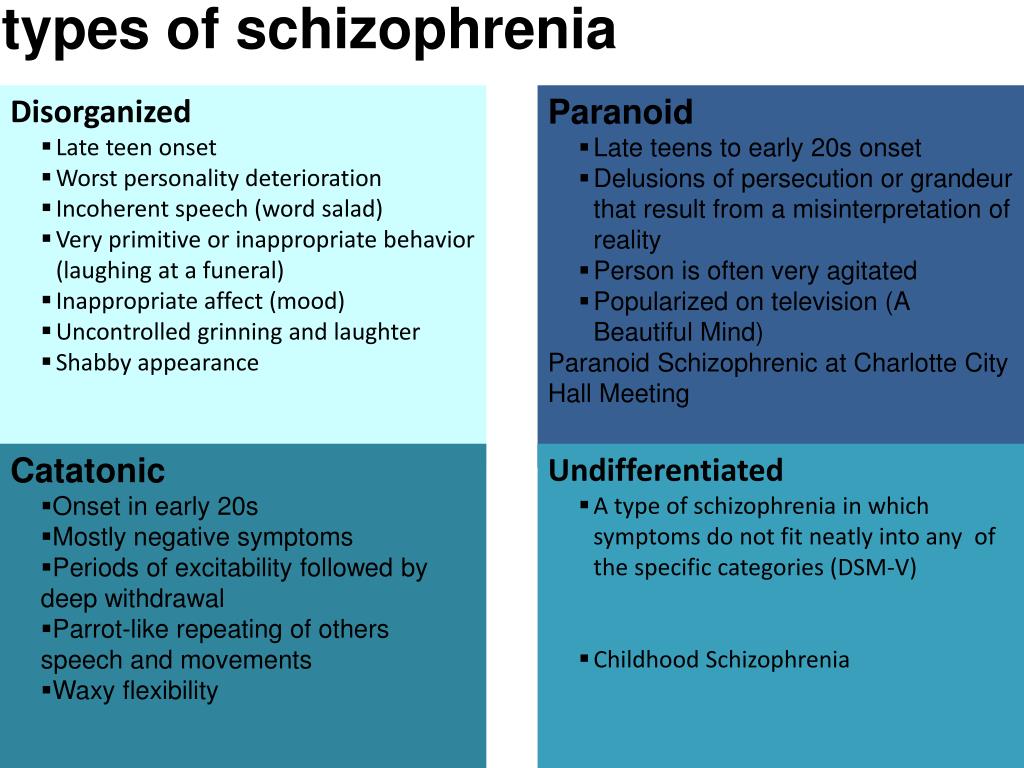

Classification

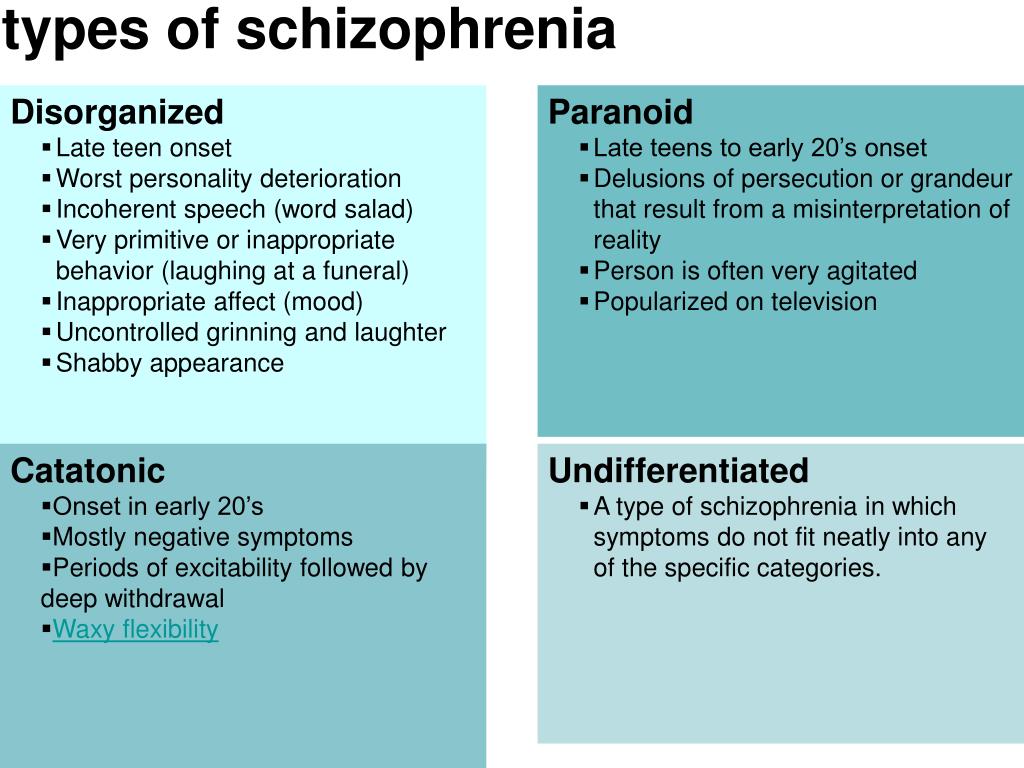

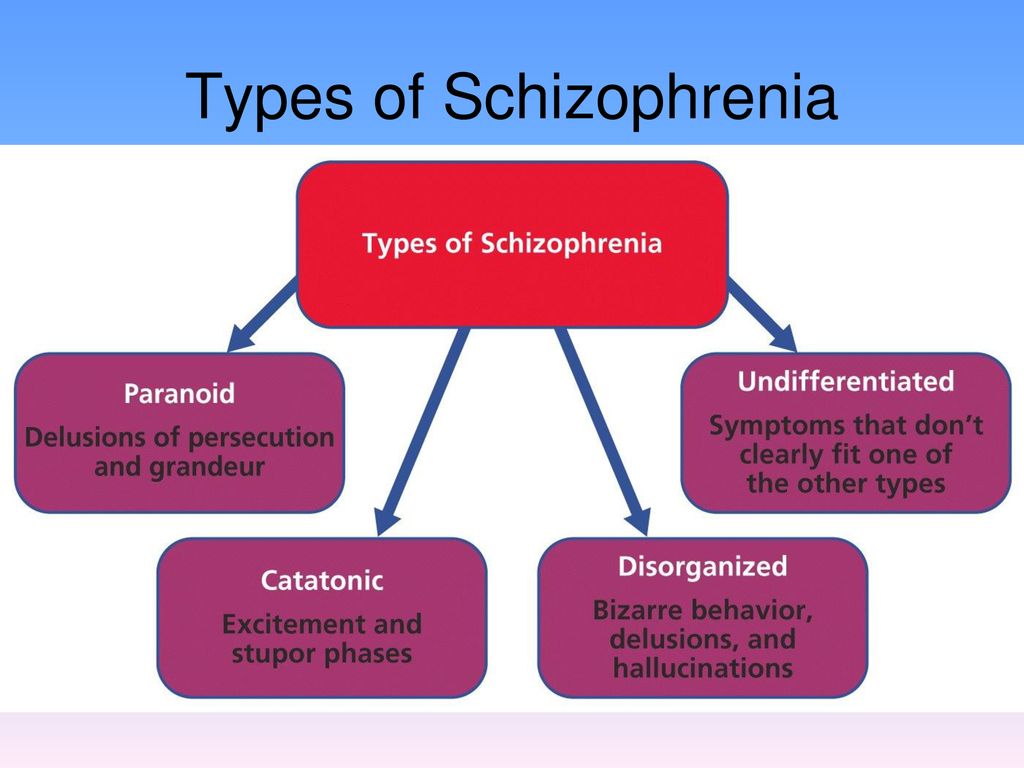

According to the international classification of diseases, there are seven forms of schizophrenia with different manifestations and prognosis.

The hebephrenic variant of the disease often debuts in adolescence or youth, is characterized by foolishness, pretentious, mannered behavior, disorganized thinking and speech disorders.

Paranoid schizophrenia is the most common. Positive symptoms come to the fore with its exacerbation. In most cases, paranoid delusions and auditory hallucinations predominate. nine0003

The catatonic form is characterized by the predominance of movement disorders. Among the latter there may be stupor, lack of speech, episodes of freezing, sometimes with complete submission and the possibility of giving the sick person any posture (wax flexibility), periodically interrupted by short-term psychomotor agitation.

Simple schizophrenia proceeds slowly, without acute psychosis, with progressive negative symptoms. Apathy, emotional coldness, loss of initiative, drives and interests are growing. The patient becomes passive, uncommunicative, "withdraws into himself." nine0003

In cases where the scarcity or, conversely, the abundance of symptoms does not allow attributing schizophrenia to one of the known forms, it is diagnosed as undifferentiated.

Residual schizophrenia can be observed in patients who previously had episodes of acute psychosis with hallucinations and delusions, followed by a chronic mental disorder with the progression of negative symptoms. Post-schizophrenic depression appears immediately after psychosis and is characterized by a persistent decrease in mood along with mild residual manifestations of the disease. nine0003

Post-schizophrenic depression appears immediately after psychosis and is characterized by a persistent decrease in mood along with mild residual manifestations of the disease. nine0003

Forms of childhood schizophrenia depend on the time of manifestation of the disease. At preschool age, negative symptoms predominate, autism increases, lack of interest in gaming activities, communication. Schizophrenia in children of primary school age is also manifested by isolation and emotional coldness, alienation from others. Patients can immerse themselves in their fantasies, live in a fantasy world. As they grow older, productive symptoms may appear, such as delusions, hallucinations, obsessions. Adolescents often have a hebephrenic variant, not only behavior changes dramatically, but also the social circle. nine0003

Conditions corresponding to various types of indolent schizophrenia (neurosis-like, psychopathic, "poor symptoms") are considered in the ICD-10 under the heading "Schizotypal disorder". They have manifestations similar to classical schizophrenia, but are more favorable in terms of prognosis, and are not accompanied by such profound personality changes.

They have manifestations similar to classical schizophrenia, but are more favorable in terms of prognosis, and are not accompanied by such profound personality changes.

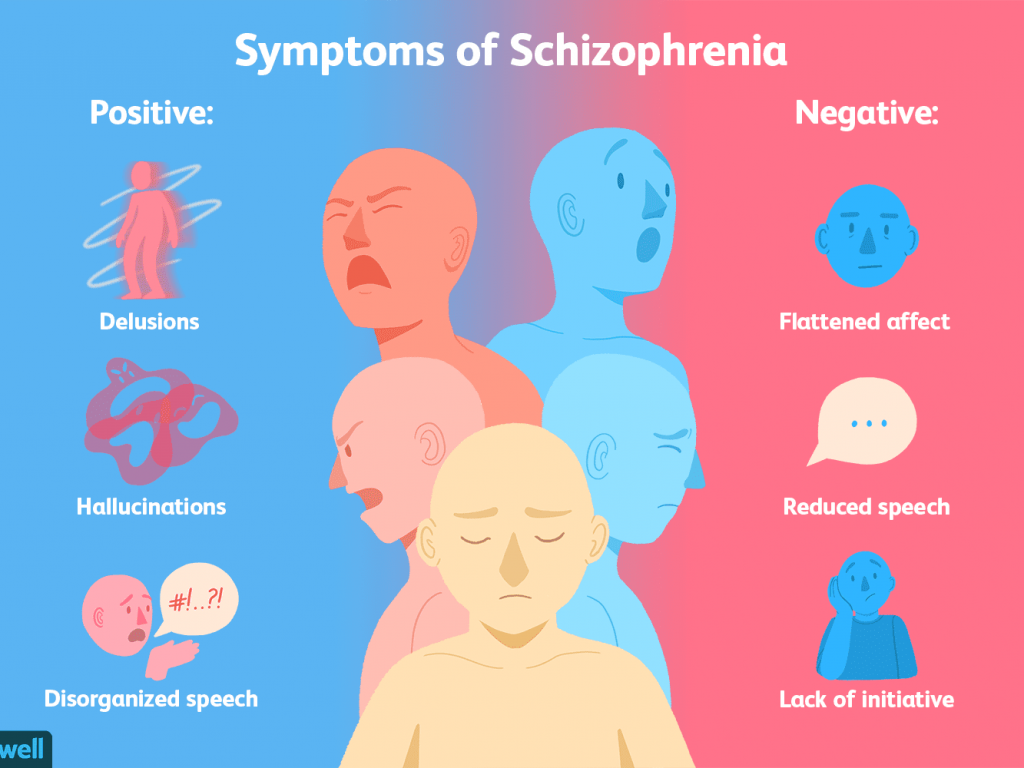

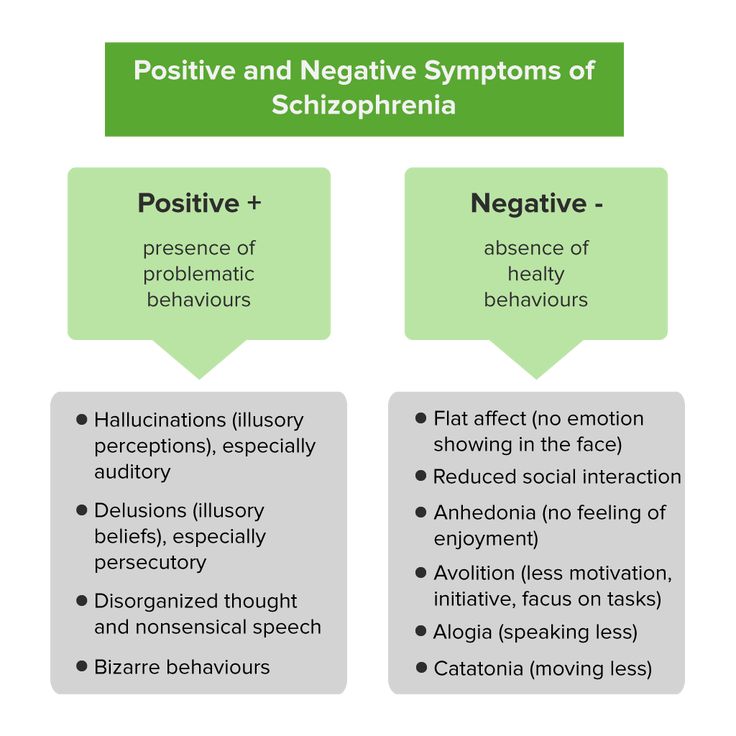

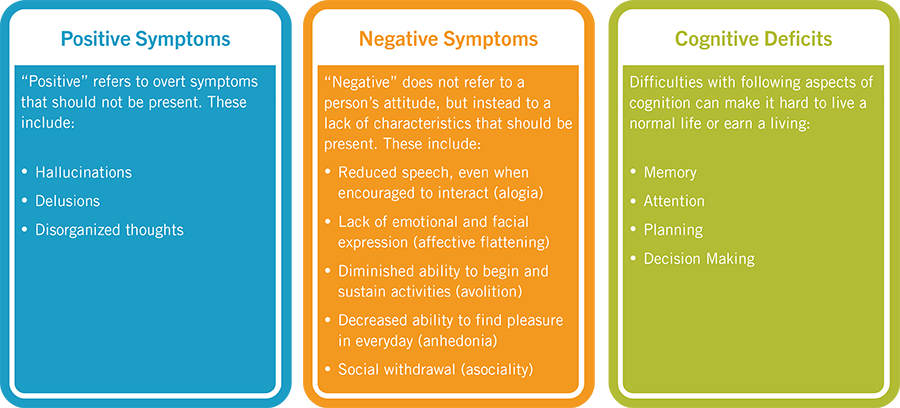

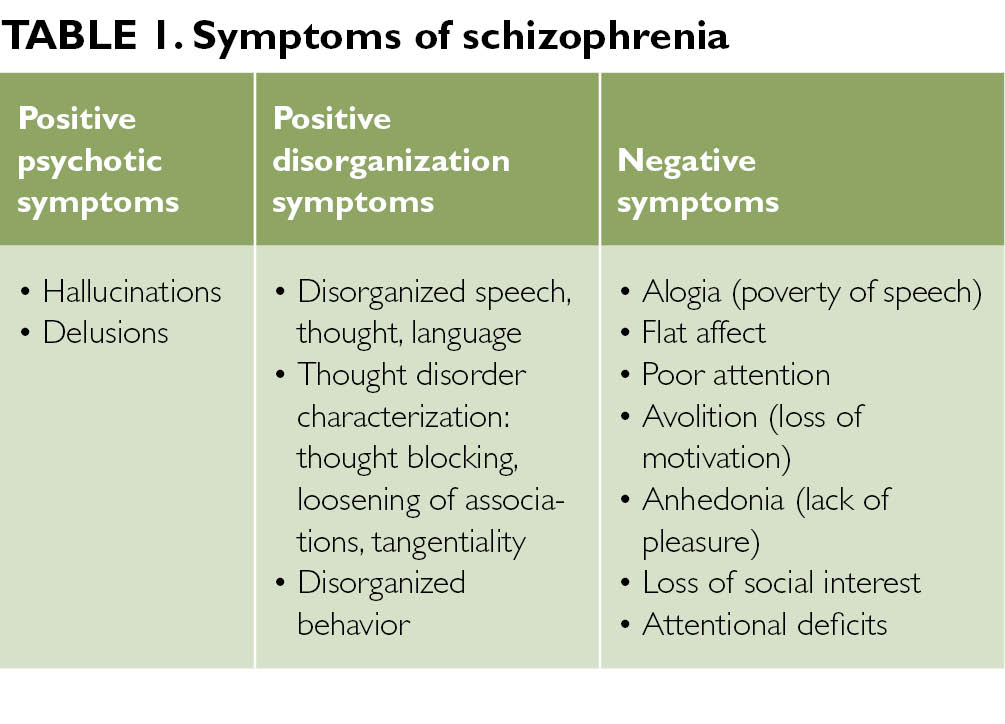

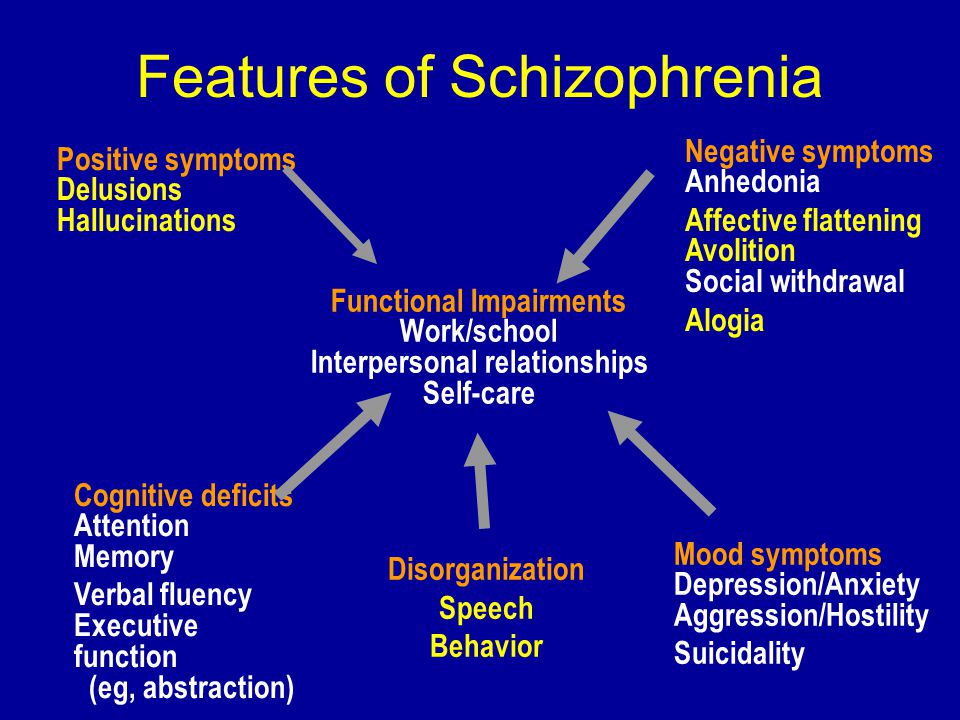

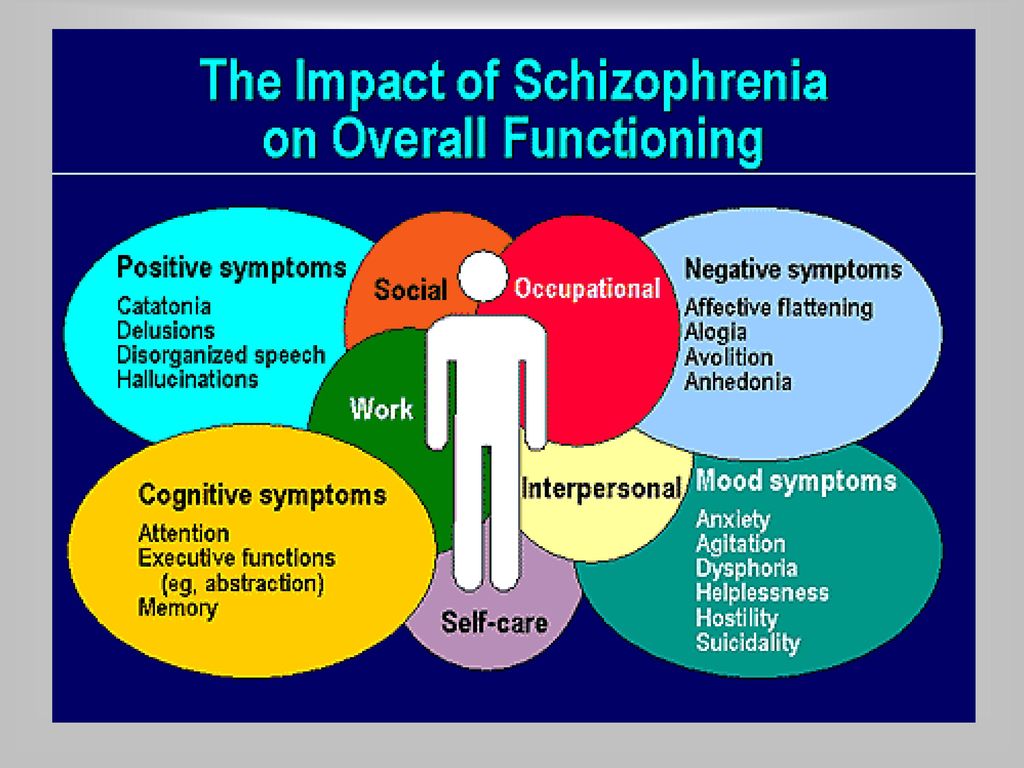

Symptoms

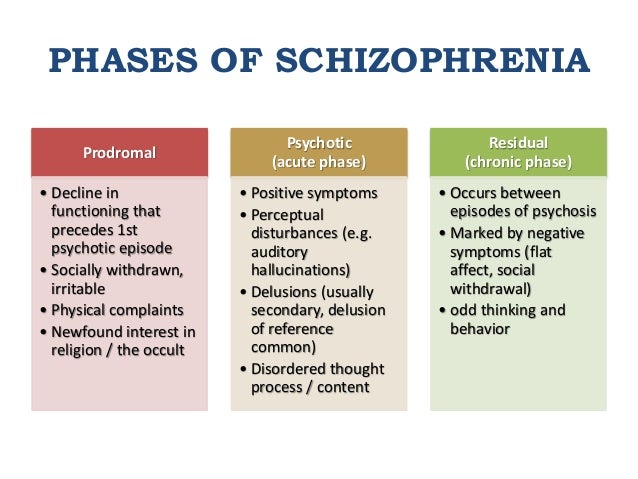

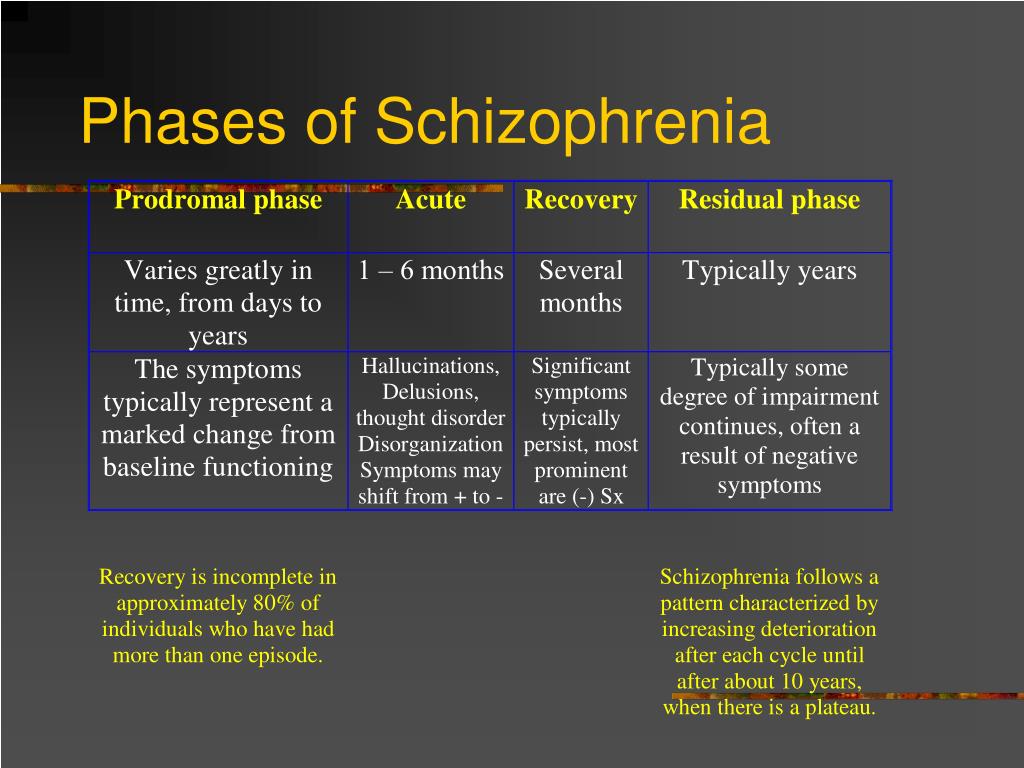

Schizophrenia proceeds in several stages. Before the manifestation of the disease, the patient may have a prodromal period for months or years. At this time, the patient gradually loses interest in work, social life, and his own appearance. There may be non-specific disturbances in memory, thinking, speech, absent-mindedness, unexplained anxiety, mild depression. Characterized by introversion, perhaps a passion for philosophy, religion, the appearance of addiction to alcohol or drugs. nine0003

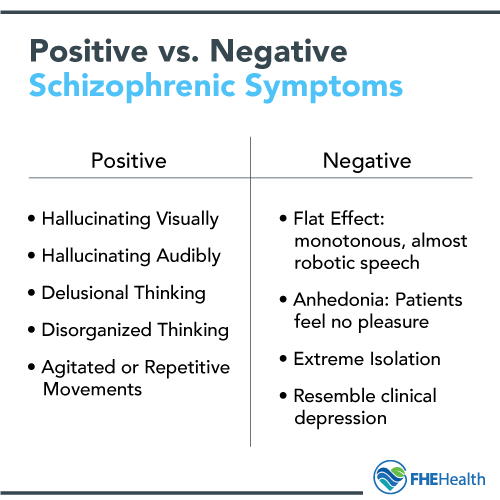

Symptoms of an exacerbation of schizophrenia or its manifestation depend on the form of the disease. During psychosis, the following phenomena may be present:

- delusional thoughts and obsessions, more often delusions of persecution;

- hallucinations, mostly auditory, often with a complete separation from reality;

- disorganization of speech and thinking;

- the appearance of suicidal tendencies;

- unreasonable fear, increased anxiety; nine0032

- behavior inappropriate to the situation;

- psychomotor agitation or limitation of mobility.

The residual stage in the interictal period is characterized by complete or partial remission of the disease. In the first case, there are no obvious signs of schizophrenia, the patient's critical attitude towards the psychosis he has suffered is usually restored, and personality changes are minimally pronounced. With incomplete relief, less obvious symptoms of a mental disorder persist. The patient is able to maintain orderly, socially acceptable behavior. nine0021 the moment of falling asleep.

Complications

The disease can progress with aggravation of negative symptoms, a growing personality defect. People with this course of schizophrenia are emotionally empty, not interested in the feelings of others, absorbed in their own experiences, being in a bad mood most of the time.

At the same time, the social isolation of such patients increases, they stop going to work or study, prefer a solitary pastime. nine0003

nine0003

Ultimately, there may be loss of self-care skills and ability to function. During acute psychosis, a person can be dangerous to himself and others, commit suicide or murder.

Diagnosis

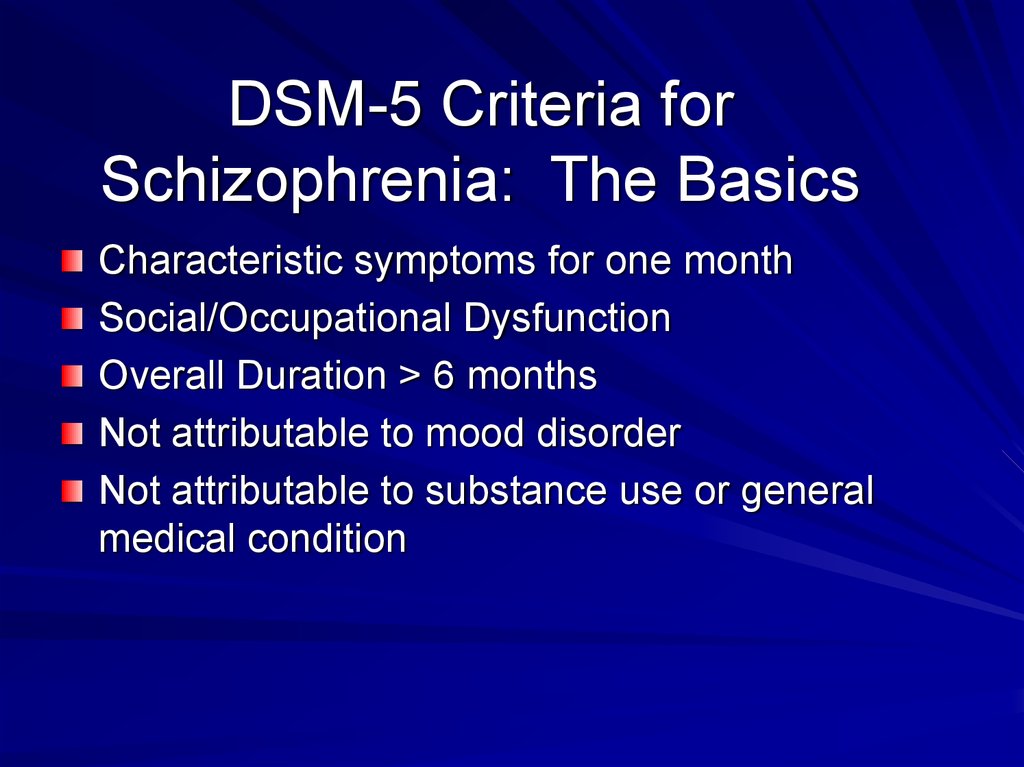

A psychotherapist or psychiatrist is engaged in the identification and treatment of the disease. Diagnosis of schizophrenia includes a conversation with the patient, and, if possible, his relatives and close associates. The patient's behavior, hereditary anamnesis, social status, existing complaints are analyzed. Symptoms of a mental disorder must be present for a month or more. nine0003

Specially designed questionnaires, tests, scales are used to correctly assess the emotional and psychological status, determine suicidal tendencies, depressive disorders and clarify other parameters. For the purpose of differential diagnosis of schizophrenia with other diseases and the exclusion of an organic cause of psychotic disorders, a consultation with a neurologist can be prescribed, laboratory and instrumental studies have been carried out.

Treatment

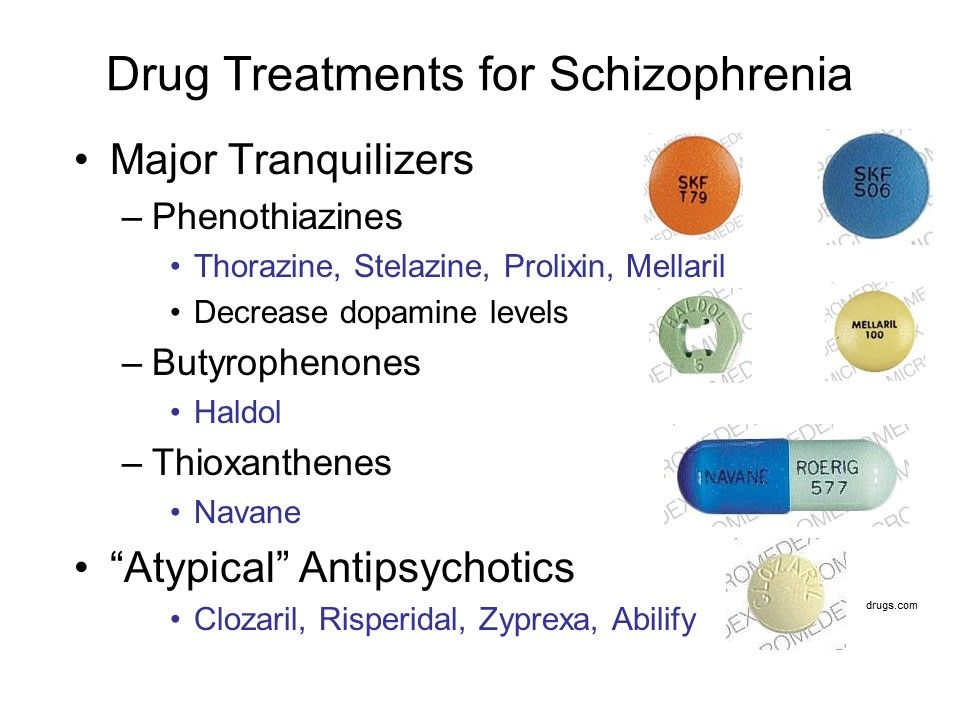

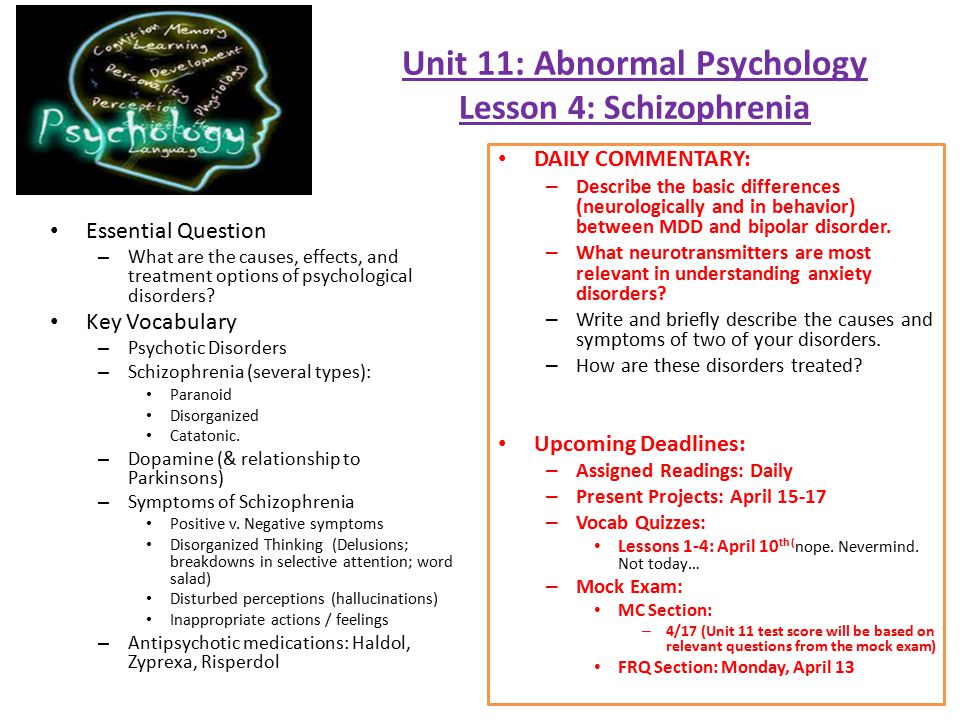

When a diagnosis of schizophrenia is established, drug therapy is recommended to relieve acute psychotic symptoms and achieve long-term remission. Antipsychotics are the first choice drugs. Additionally, tranquilizers and mood stabilizers can be used. nine0003

Physiotherapeutic methods are used when medicines are ineffective. They involve the effect of an electric current or magnetic field on the brain.

Psychotherapy sessions are carried out outside the exacerbation of the disease. An important place in the treatment of schizophrenia is occupied by the social rehabilitation of such patients, education, psychological support by the patient's relatives and friends.

It is necessary to exclude factors that can cause a relapse of the disease and aggravate negative symptoms:

- alcohol and drug use;

- lack of family and social support;

- condemnation from others;

- stress;

- insufficient sleep;

- nicotine addiction.

Prophylaxis

Since the cause of schizophrenia has not been established, specific prevention measures have not been developed. Patients should be informed about the increased risk of developing mental disorders in their children. Early detection and treatment of the disease increases the patient's chances of establishing a long-term remission. nine0003

The author of the article:

Novikov Vladimir Sergeevich

psychotherapist, clinical psychologist, kmn, member of the Professional Psychotherapeutic League

reviews leave feedback

Clinic

m. Frunzenskaya

Reviews

Services

- Title

- Primary appointment, consultation with a psychotherapist (up to 1 hour) 4000 905 years. Red Gates. AvtozavodskayaPharmacy. Glades. Sukharevskaya. st. Academician Yangelam. Frunzenskaya Zelenograd

Sorokin Maxim Vladimirovich

psychotherapist

reviews Make an appointment

Clinic

metro Frunzenskaya

Not Found (#404)

hide menu

Issues of the current year

-

7-8 (136)

-

5-6 (135)

-

3-4 (134)

-

2 (133)

-

1 (132)

7-8 (136)

Contents of issue 7-8 (136), 2022

-

War Wikis: help in crisis situations

nine0031

Ethical and legal problems of mental health: Ukraine at the focus of international respect

Yu.

-