Therapy intake questions

Therapy Questions Every Therapist Should Be Asking

Healing conversations are an art form in peril of being lost to our busy lives.

The ultimate goal of talk therapy is to enable the process of psychological and emotional healing along the continuum from the problematic toward a sense of greater mental wellbeing.

Although we often come to therapy with a problem, we also come as people who want to be heard and understood, feel like we matter, wish to learn self-compassion, and want to find partnership in helping us heal and see ourselves and our life situation in a different light.

I would rather have questions that can’t be answered than answers that can’t be questioned.

Richard Feynman

Progress in a therapeutic relationship cannot be made unless the client feels safe to speak their mind, and it is on the practitioner to create that climate of openness and transparency.

The process also often requires the clinician’s willingness to work diligently to help clients understand what they want, the patience to help them learn to own all aspects of themselves, including contradictory feelings, and the ability to create a safe space to allow for transformation to occur.

Most of what happens in talk therapy is accomplished through the skillful use of questions, but only second to a lot of active listening.

This article surveys different approaches to asking therapeutic questions meant for both practitioners and their clients and gives examples of how the quality of questions we ask can improve our lives. For more common therapy questions, see our related post: Classic Therapy Questions Therapists Tend to Ask.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

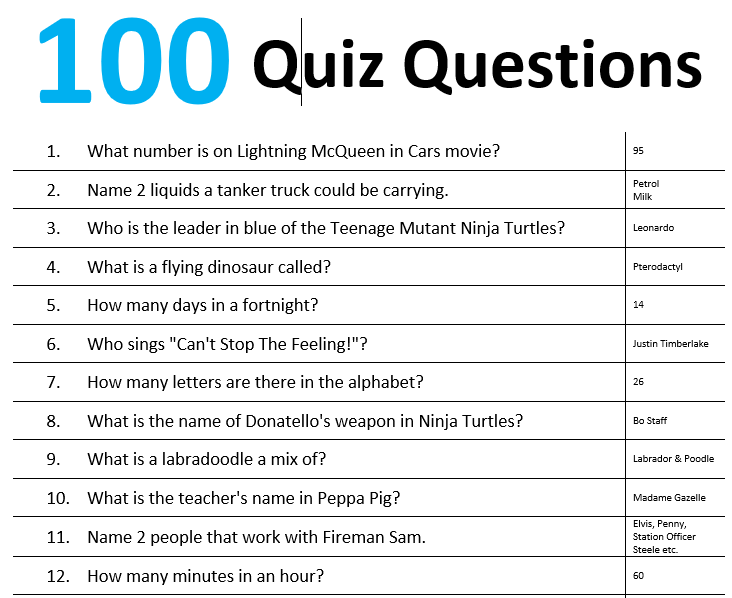

- 7 Questions Designed for the First Therapy Session

- Therapy Intake Questions to Ask Patients

- 15 Useful Therapy Questions to Ask Yourself

- 20 Couples Therapy Questions Designed to Improve Relationships

- 30 Family Therapy Assessment Questions

- The Family Therapy Questions Game

- Therapeutic Questions for Youth

- 15 Therapeutic Questions for Group Therapy Discussions

- A Take-Home Message

- References

7 Questions Designed for the First Therapy Session

The first therapy session must focus on relationship building and creating rapport, which are necessary to establish an effective foundation for a practitioner–client relationship, often referred to as the therapeutic alliance. The outcomes of therapy are heavily dependent on the quality of this relationship (Lambert & Barley, 2001).

The outcomes of therapy are heavily dependent on the quality of this relationship (Lambert & Barley, 2001).

Ideally, the first therapy session should be a form of positive inception so the practitioner can set the stage for future interactions. Carl Rogers (1961) used to say that the therapist must create an environment where everyone can be themselves.

Courage doesn’t happen when you have all the answers. It happens when you are ready to face the questions you have been avoiding your whole life.

Shannon L. Alder

The very first question in therapy is usually about the presenting problem or the chief complaint for which the client comes to therapy, often followed by an exploration of the client’s past experience with therapy, if any, and their expectations of future outcomes of therapy.

1. What brings you here today?

For clients who need encouragement to open up, it may be helpful to remark on their bravery in seeking therapy.

For those who are at the other extreme and go into a lengthy and detailed explanation of their issues, perhaps having been in therapy before, it is best to listen empathically first before complimenting them on how well they appear to know themselves and how they have thought a lot about what they would like to talk about in therapy.

2. Have you ever seen a counselor before?

For those who are in therapy for the first time, observing how comfortable and confident they are in talking about the challenges in their life can help set the stage for further disclosure.

It may be helpful to set some expectation of what is going to happen in the therapeutic process by explaining how asking questions is at the core of the process and reassuring the client that they should feel free to interrupt at any time and to steer the conversation to where they need it to go.

If the client has seen a counselor before, it can prove very valuable to inquire further about their previous experience in therapy by asking about frequency, duration, and issues discussed during their previous engagements, as well as one thing they remember most that a former counselor told them.

An important aspect for gauging clients’ engagement in the process of therapy is asking them about what went right or didn’t turn out the way they would have liked in their previous therapeutic engagement, as this can point to where they place the sense of responsibility for their situation.

Inquiring if the client achieved the results they sought and if they have been successful in maintaining them outside of the therapeutic relationship can also provide valuable insight into their motivation for change.

3. What do you expect from the counseling process?

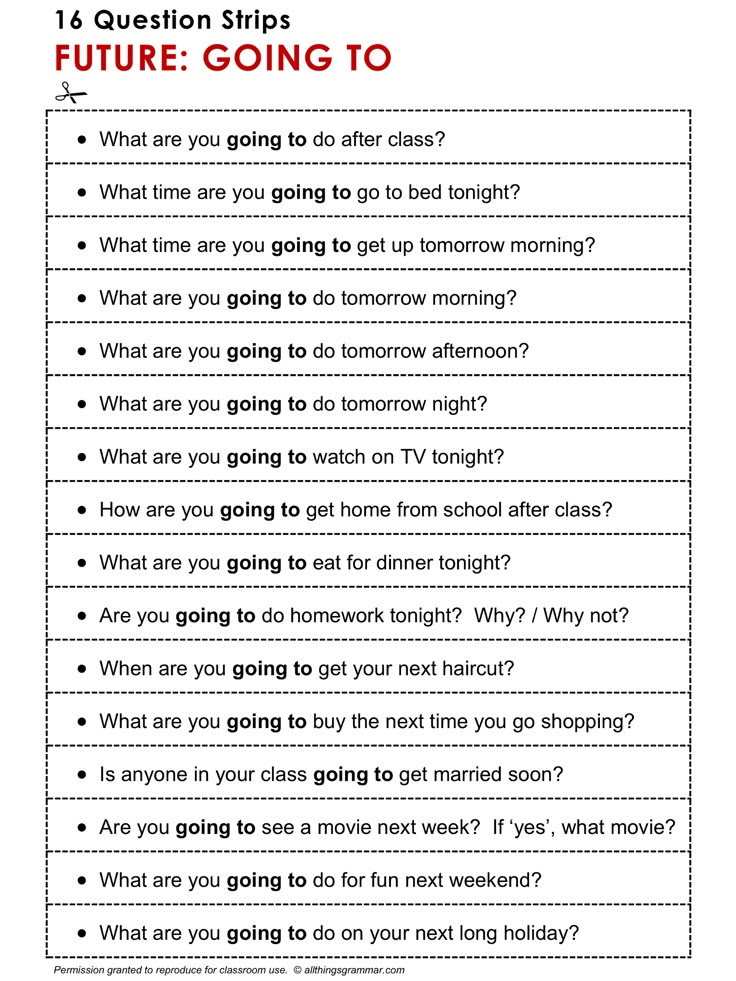

Establishing a mutual agreement and setting expectations for the engagement is crucial to making progress. Clients’ goals and preferences for the format and level of interaction need to be taken into consideration.

Some clients like to vent and have the counselor listen; others want a high level of interaction and a spirited back-and-forth. It is also important to inquire how the client learns best and if they like to receive homework.

Other examples of questions that can point to the tone and flow of future communications can include the following:

- How many meetings do you think it will take to achieve your goals?

- How might you undermine achieving your own goals?

- How do you feel about using good advice to grow from?

- How will we know when we have been successful in achieving your goals for therapy?

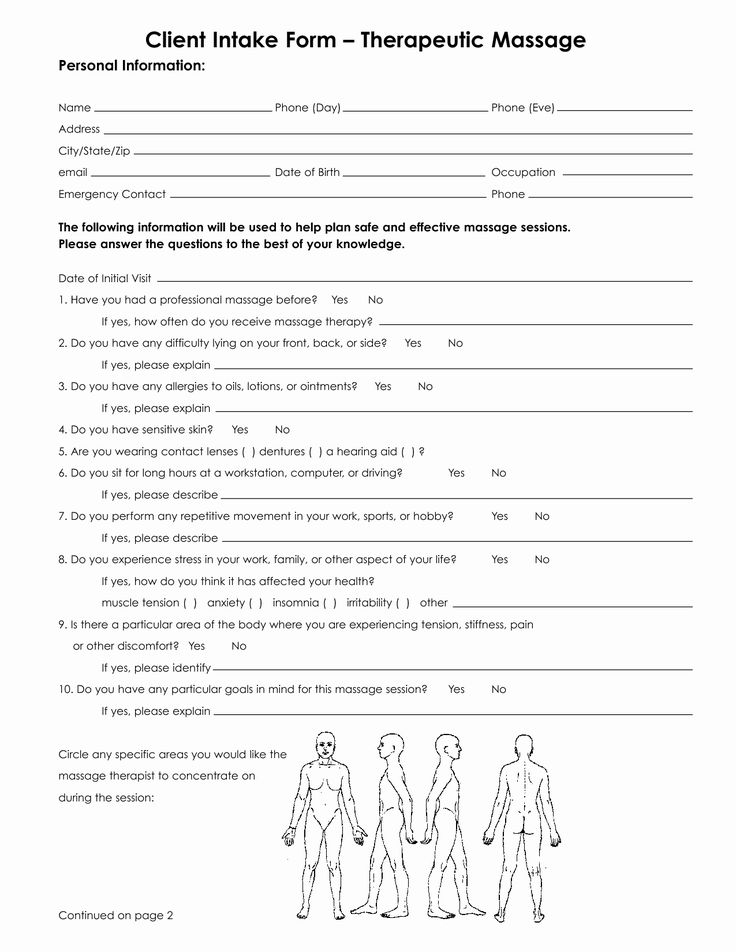

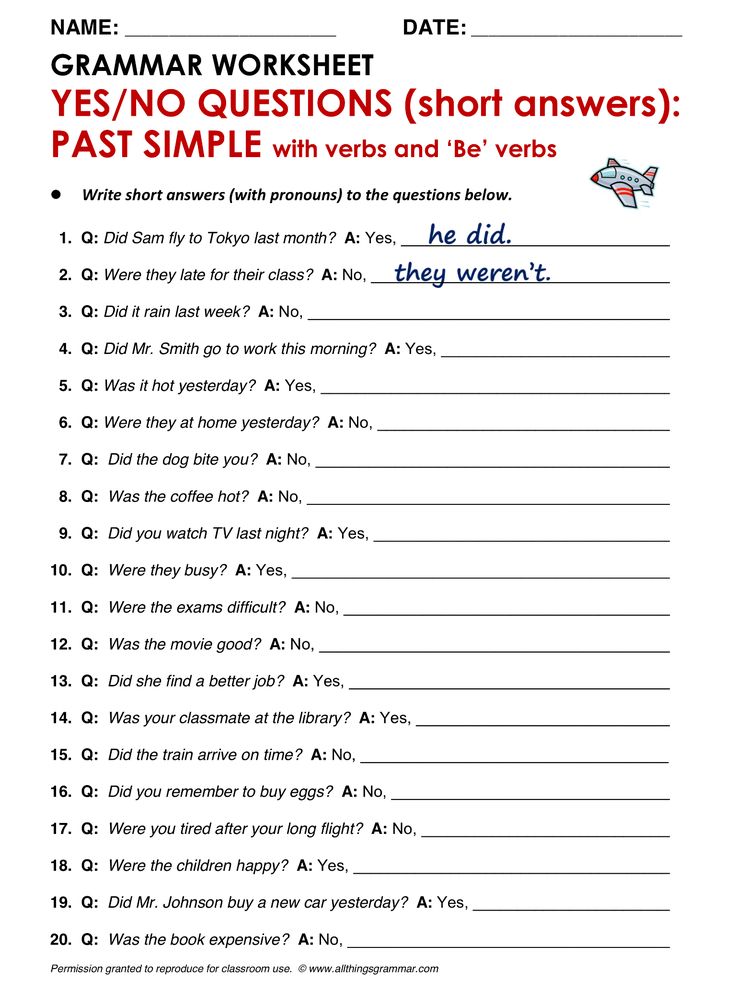

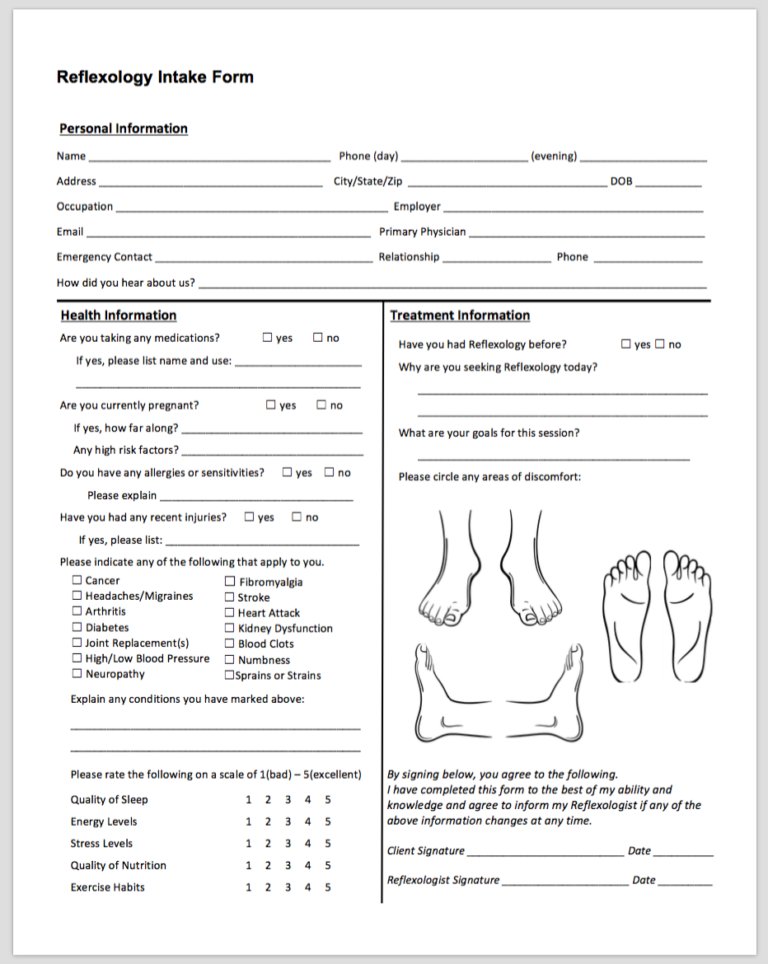

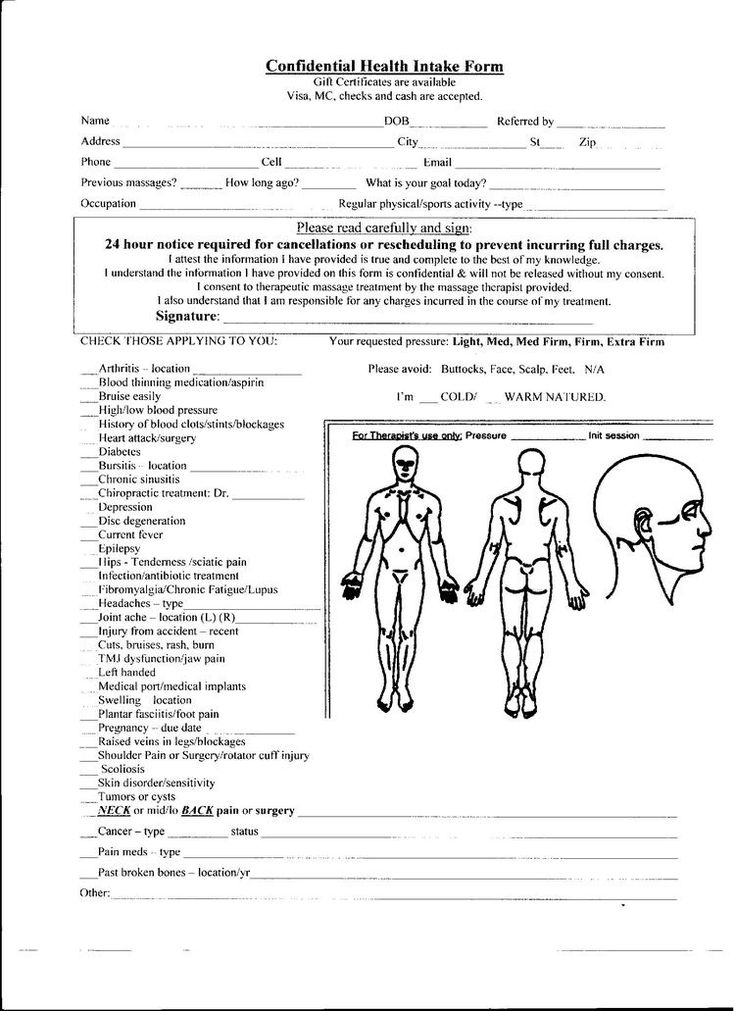

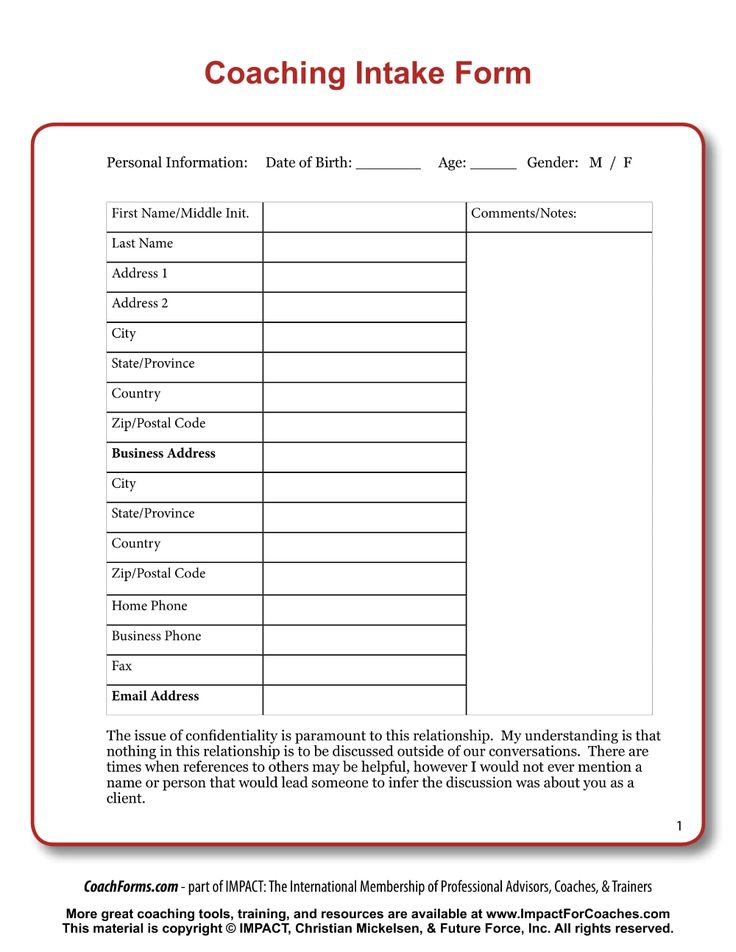

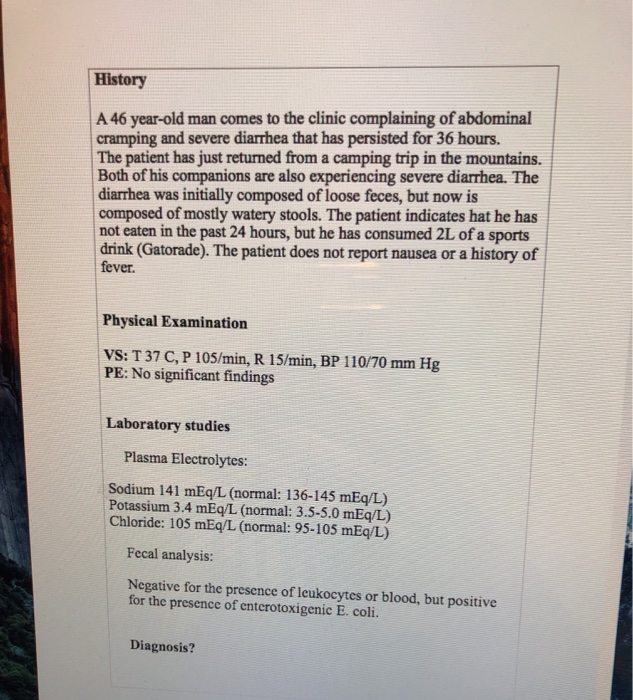

Therapy Intake Questions to Ask Patients

Levy et al. (2018) analyzed records from healthcare providers and found that:

- 45.7% of adults avoided telling their providers that they disagreed with their care recommendations.

- 81.8% of adults withheld information because they didn’t want to be lectured or judged.

Many aspects of clients’ lives can influence their engagement and progress in therapy.

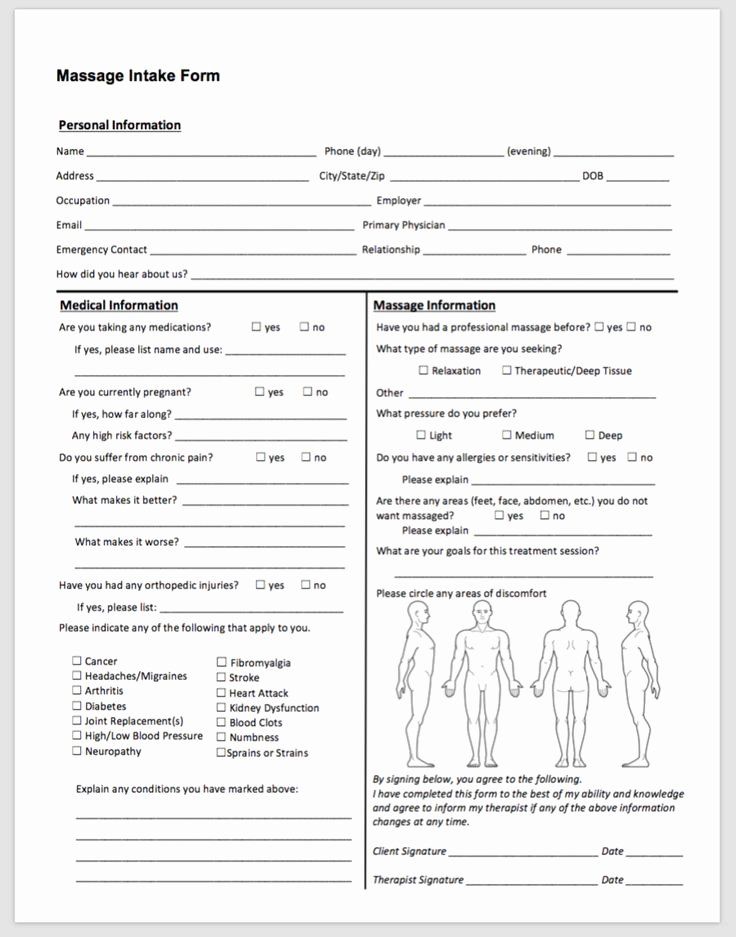

Indeed, questions about preexisting medical conditions, current and past treatments, medications, and family history are essential to the effective assessment of needs and the successful provision of therapeutic treatment. Therefore, having a clear picture of these details is a critical part of the initial intake process.

Therefore, having a clear picture of these details is a critical part of the initial intake process.

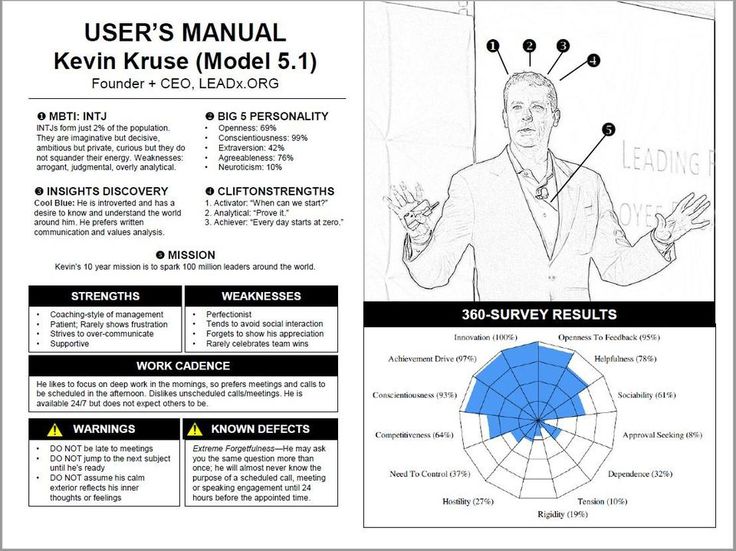

In order to gather this information securely and efficiently, therapists are increasingly drawing on digital technologies. For instance, using a blended care platform such as Quenza (pictured here), therapists can design and distribute standardized sets of intake materials, such as forms and agreements, that clients can complete on their own devices and at a time that suits them.

The benefits of providing intake forms digitally is that they can facilitate better documentation and record keeping for practitioners. Additionally, and unlike paper forms, they can be programmed to ensure no critical questions are accidentally missed.

It is important to note that while most therapists do not prescribe medication, many often partner with other medical professionals by making recommendations, particularly in instances when clients have been referred for therapy.

An intake form is attached and can be a useful guide for some of the issues that may require further exploration.

15 Useful Therapy Questions to Ask Yourself

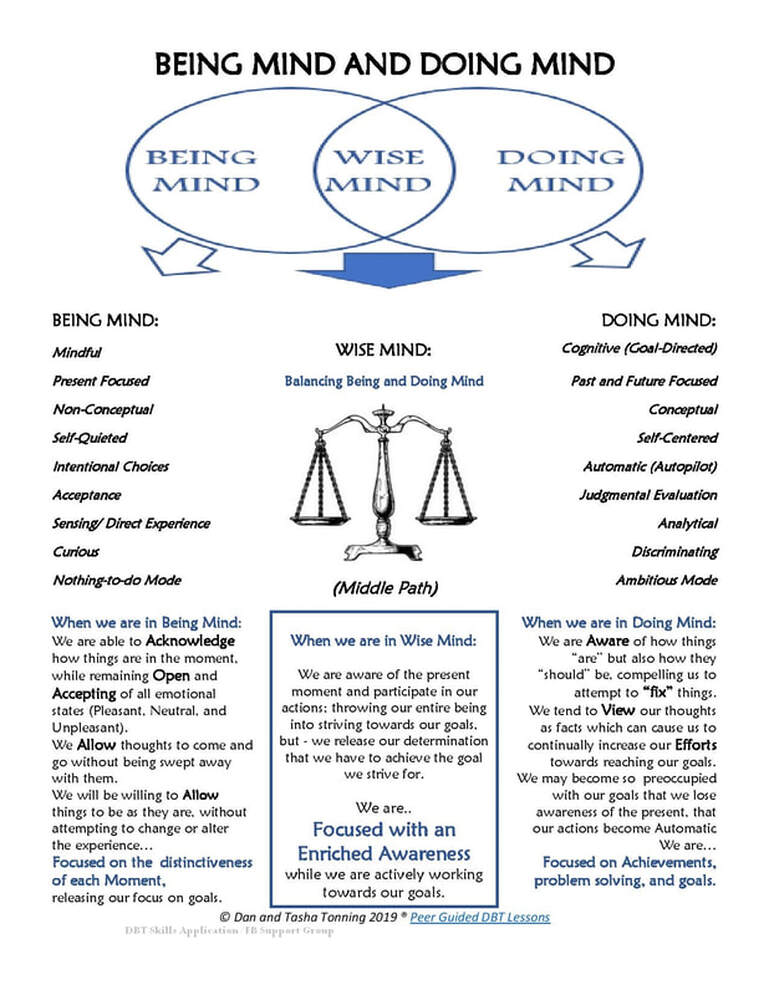

We get into thinking ruts and routines and often function on autopilot without giving much consideration to the way we go about our day or spend our time and energy.

We can break this mindless cycle by asking meaningful questions of ourselves and reflecting deeply on our thoughts, emotions, and behavior. Many self-help therapy books have popularized a way of doing just that.

One such approach can be found in vastly popular notebooks that provide inspirational therapy quotes or reflective writing prompts that get our cognitive wheels spinning.

The most important questions in life can never be answered by anyone except oneself.

John Fowles, The Magus

Another important form of self-inquiry is to ask yourself questions that we can’t answer honestly in the presence of anyone else, probing and burning questions that we can often only answer for ourselves. They may require some reflection, examination of values, and perhaps writing, if only to organize our thoughts.

Here is a list of important questions we should revisit periodically:

- Assessing our life satisfaction – Tools like the Wheel of Life (accessible via the linked post) or one of the many Happiness Assessments are a great place to start.

- Exploring meaning in our lives – Our masterclass in Meaning and Valued Living is a great place to start.

- Defining our values – value exploration exercises

- Finding character strengths – VIA Strengths Assessment

- Visualizing goals – SMART goal setting, tracking how we invest our time with experience sampling method or Miracle Question (included below)

- Cultivating gratitude – Three good things exercise

- Practicing forgiveness – Empty chair technique (included below)

- Making bucket lists

Other useful questions are those that we can use to motivate ourselves. For example, appreciative inquiry questions focus on strengths and the propelling power our past successes can have on self-efficacy and motivation toward goal pursuit.

Here are a few examples of questions and prompts based on appreciative inquiry:

- Think back through your career. Locate a moment that was a high point, when you felt most productive and engaged. Describe how you felt and what made the situation possible.

- Without being humble, describe what you value most about yourself and your work.

- Describe your three concrete wishes for your future.

- Describe the most energizing moment, a real “high” from your professional life. What made it happen?

- How do you stay professionally affirmed, renewed, enthusiastic, and inspired?

Sometimes, self-therapy can feel like chasing our tail, particularly for those who already live in their heads a bit too much and may feel a bit stuck.

The most important questions to ask ourselves at this point are those that allow us to evaluate whether we should be reaching for help and if our situation warrants considering therapy.

- Have I struggled to be myself lately?

- Has daily life felt harder lately?

- Do I have a confidante who I can trust to be impartial?

- Is there a big choice in my life I have been struggling with?

- Is my worry increasing, and are my thoughts less logical?

- Have I lost interest in things I used to love lately?

- Have friends been avoiding me or saying they have been worried about me?

- Am I just not bouncing back from something?

- Do I have a habit that I keep secret from others that causes me ongoing shame and life problems?

- Do I spend most of my time feeling worthless compared to others?

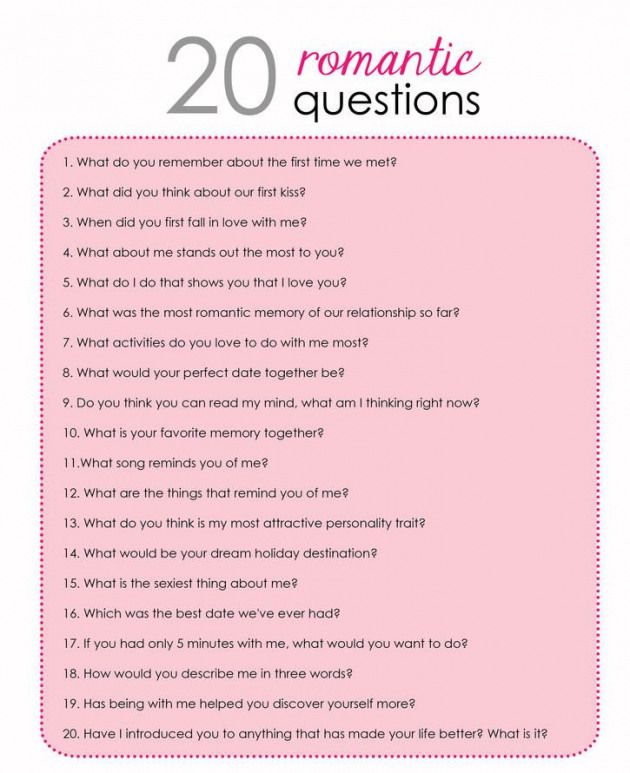

20 Couples Therapy Questions Designed to Improve Relationships

Dr. John Gottman, an expert marriage therapist who has observed couples for over 40 years, tells us that we have a very high chance for miscommunication in close relationships (Gottman & Silver, 2015).

John Gottman, an expert marriage therapist who has observed couples for over 40 years, tells us that we have a very high chance for miscommunication in close relationships (Gottman & Silver, 2015).

How do we cope with those unfavorable odds? Through acceptance, the practice of active listening, and the realization that relational conflict is an opportunity for growth.

Lack of acceptance is often an important component of relationship gridlock, as it causes both people to feel criticized or rejected (Gottman & Silver, 2015). There are always two points of view, both valid and right, from within each perception.

The need to be right prevents us from actively listening to each other. Communicating fundamental acceptance instead of rejection of the other person’s personality is therefore basic to all effective problem solving.

Active listening requires practice and comes down to moving from self-informed certainty to curiosity about the other person. It helps to adopt an “and stance,” where both stories are valid, the world is complex, both partners can get angry, both contribute to the situation, and both are doing their best.

Couples can improve their odds of having a productive talk by (Gottman & Silver, 2015):

- Finding things in common (Gottman and Silver recommend having good Love Maps of each other)

- Getting to know each other’s flexible and inflexible areas for negotiations

- Offering to help meet the core needs of another person

- If gridlock seems unavoidable, figuring out if we need a temporary compromise

What often happens in couples therapy is an equivalent of the two people getting to know each other in a different way, improving communications, and learning that conflict can be an opportunity for growth.

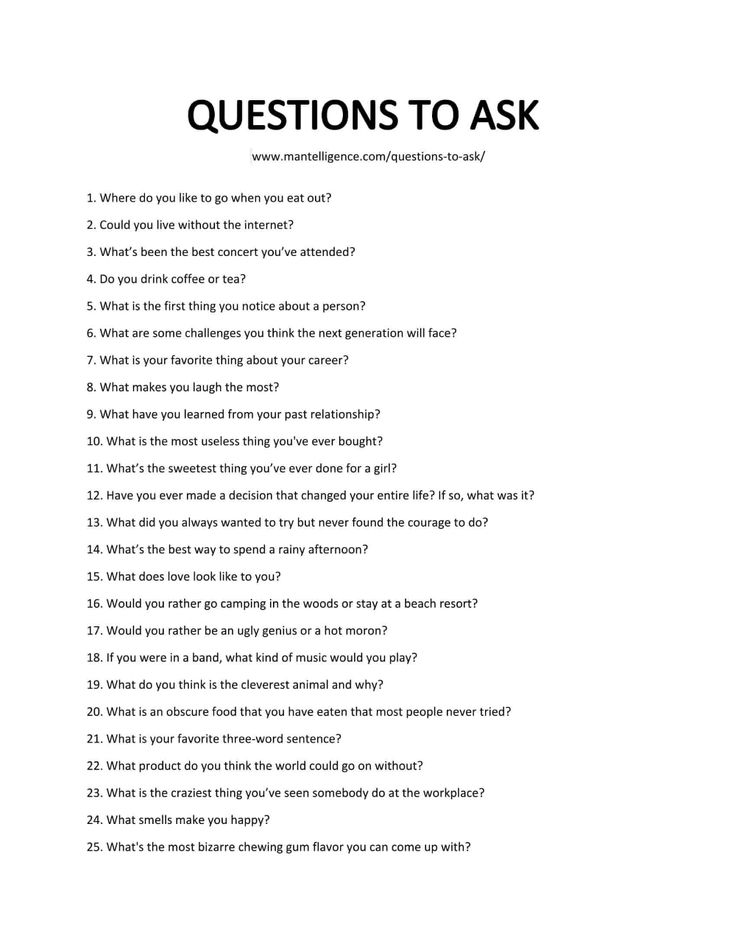

Some of the most common questions explored in couples therapy include:

- Why choose today?

- How did you decide to come to therapy?

- What brought you together in the first place?

- How does your relationship affect your levels of joy?

- What do you wish your partner would do more?

- How do you cultivate trust in your relationship?

- Describe your level of satisfaction with intimacy in your relationship.

- How would you rate your communication skills: negative, neutral, or positive?

- What positive relationship rules do you follow?

- In the recent past, what did you do when your partner disappointed you?

- How much can you recall about what your partner did last week?

- How would you describe your other relationships, like those with family and friends?

- What family conflicts have you been embroiled in recently?

- What relationship have you been in that you judged to be a failure?

- Who do you call upon when your heart is hurting?

- What is your most significant vulnerability or Achilles heel in relationships?

- What is your relationship forecast for both now and in the future?

- What counseling questions do you hope aren’t asked?

30 Family Therapy Assessment Questions

Some of the most important relationships in our lives can be both a source of happiness and the greatest struggle at the same time. The closest people in our lives influence in no small degree who we become as a person and shape our view of the world around us in significant ways we often underestimate.

The closest people in our lives influence in no small degree who we become as a person and shape our view of the world around us in significant ways we often underestimate.

Some approaches to family therapy employ systemic interpretations; for example, depression may be viewed as a symptom of a problem in the larger family.

When a family seeks counseling, the questions focus on the relationship’s dynamics, everyone’s met and unmet needs, and goals for the relationships. Assessing these factors, while it may seem complicated at first, is nevertheless worth the time.

Dysfunctional communication patterns within the family can be identified and corrected through teaching family members how to listen, ask questions, and respond non-defensively.

The genogram is one such tool used in family therapy. It’s mostly a family tree that provides a visual representation of three to four generations and explores how patterns or themes within families influence their current behavior and identifies whether relationships in the family have been close, distant, or ridden with conflicts.

It asks about values, beliefs, traditions, characteristics, and habits of family members, including health issues, alcohol and drug use, physical and mental health, violence, crime and trouble with the law, employment, and education. See Simple Guide to Genograms.

Some of the questions about relationships between family members include:

- Who are you closest to?

- What is/was your relationship like with… ?

- How often do you see… ?

- Where does … live now?

- Is there anyone here that you really don’t get along with?

- Is there anyone else who is very close in the family? Or who really don’t get along?

When exploring patterns and themes, good questions are:

- Who are you most like?

- What is … like? Who else is like them?

- Did anyone else leave home early?

- Is anyone else interested in art/science/etc.?

The following questions may also help explore the family background and family dynamics:

- Who is important to you in your life? Why are these particular people important?

- Who provides the most support in your life?

- How have members of your family reacted to the problems that you are currently experiencing?

- Are members of your extended family aware of what you have been experiencing?

- What was it like growing up in your family?

- Perhaps you could talk about some of the memories, both good and not so good.

- What is it like for you right now living in your family?

- How do you think your family might describe you? What qualities or strengths might they say you have?

- Are there members of your extended family who you feel close to or feel that you have something in common with?

- Did you feel safe in your family?

- How does your family handle disagreements?

- Is it okay to express your emotions in your family? To feel happy, sad, frustrated, angry, content, etc.?

- Tell me about your different family members and how they express their emotions.

- Were there times when you were worried about any of your family members? Why were you worried? How were these concerns handled?

- What qualities do you bring to your family that are special or unique?

- Were there any special activities that you did together?

- Did your family mix with other families?

- What other information would you like me to know about your family that will be helpful during our time together?

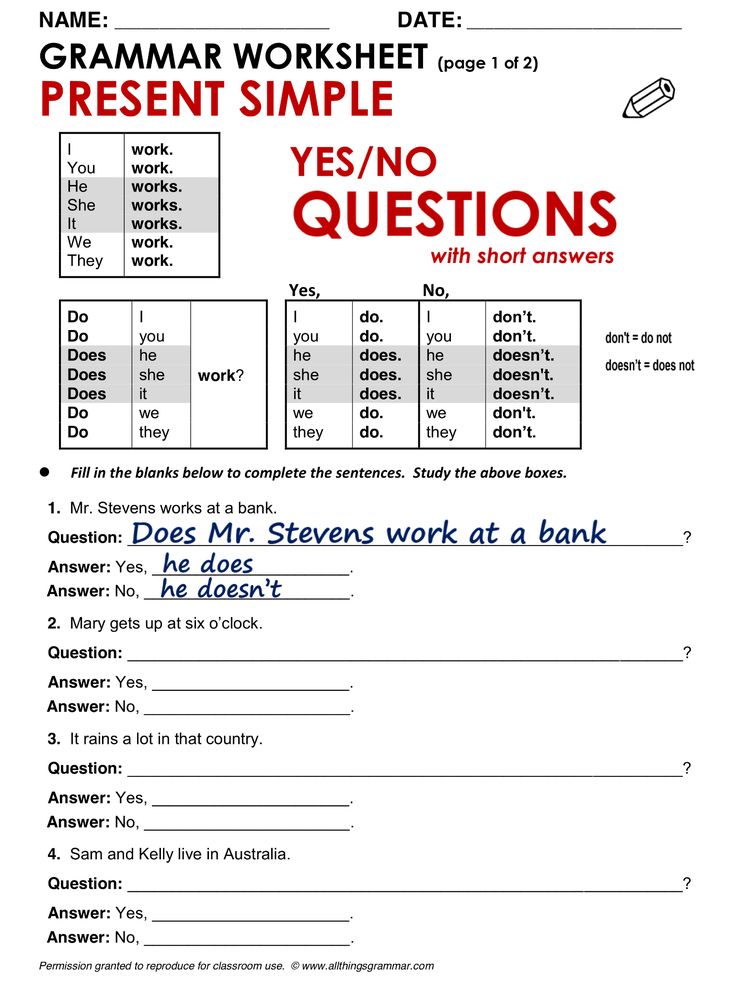

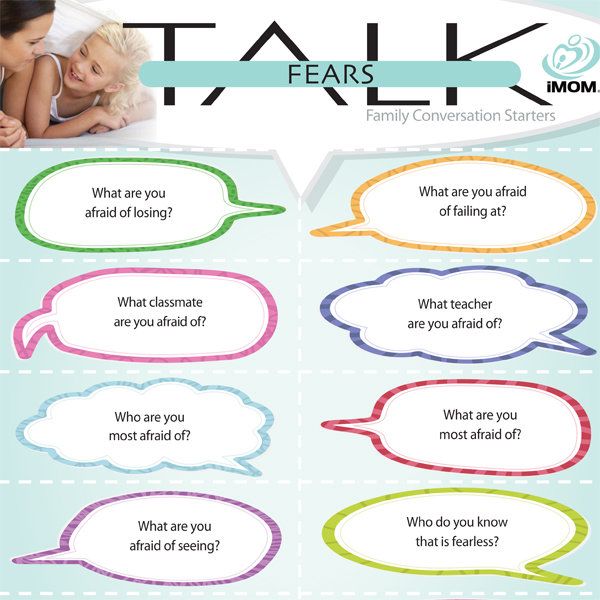

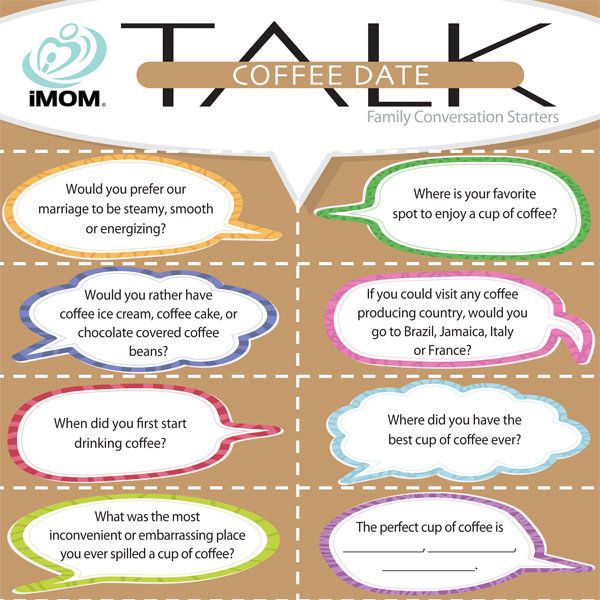

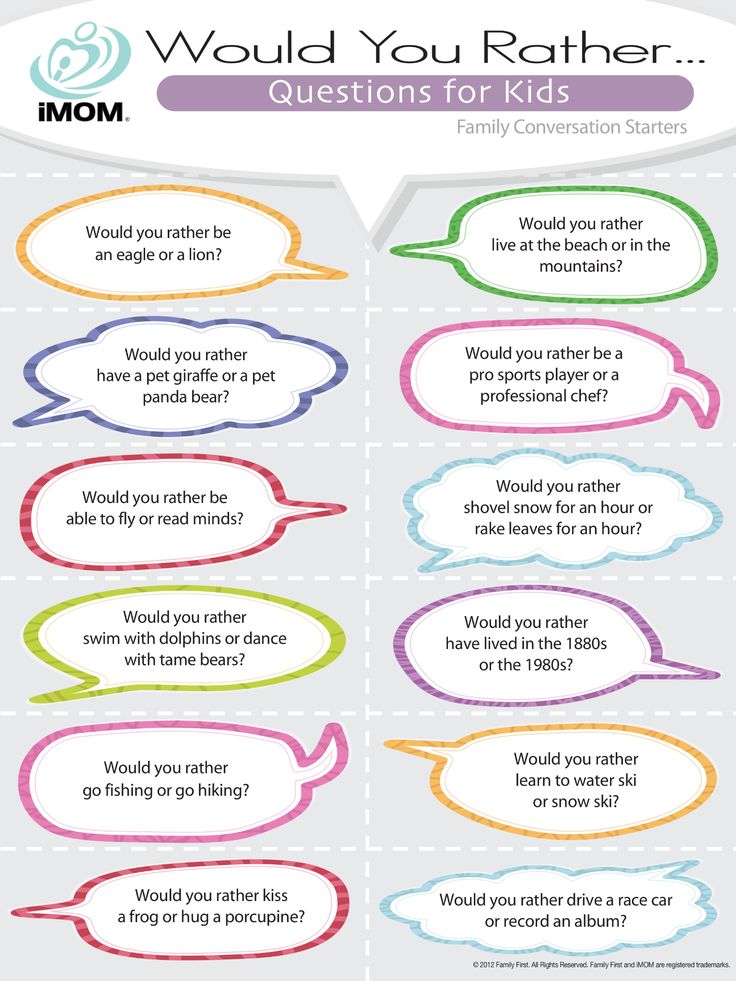

The Family Therapy Questions Game

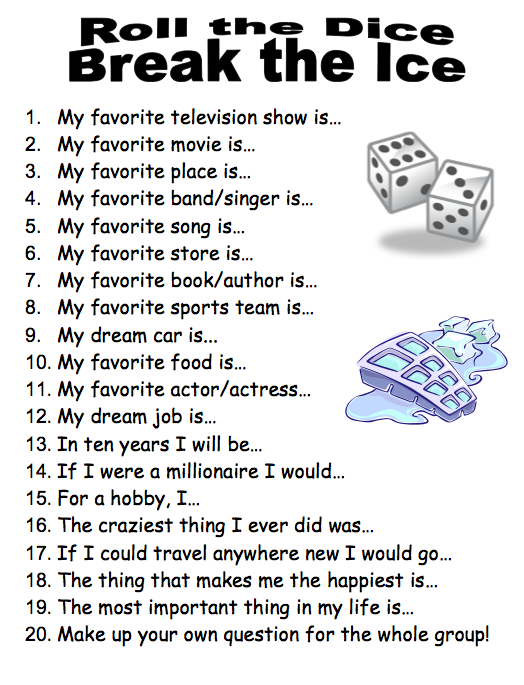

One of the most effective ways to address family dynamics, particularly when it involves children, is by playing games. It removes the formality and allows for interaction to unfold in a nonthreatening way that often brings out the best in all participants.

It removes the formality and allows for interaction to unfold in a nonthreatening way that often brings out the best in all participants.

While it is fun for the children, it also allows the adults to regress for a moment and get down to the level of being playful and spontaneous. In the end, we find out that we don’t know as much as we thought we did about the most important people in our lives.

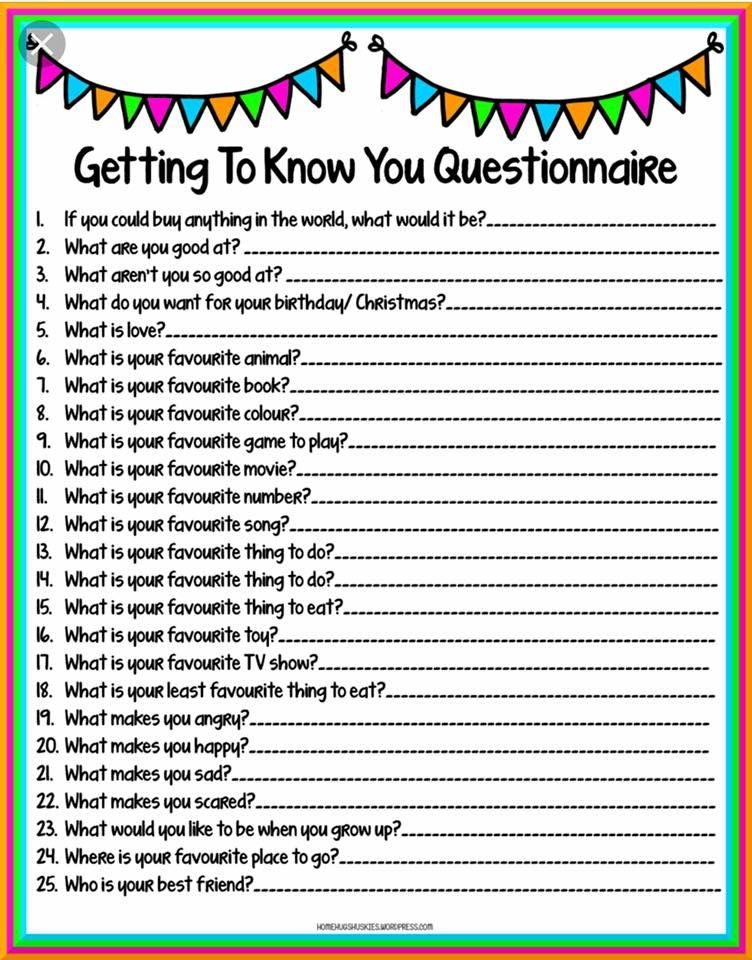

The family conversation starters below can be used in a family therapy session as well as at home. They can and should be personalized in a way that is age appropriate and has a specific goal in mind: to bring family members together, help them communicate effectively, express their emotions, or move toward constructive problem solving.

Another great activity known as ‘What will they say?‘ encourages family members to guess what another family member will say in response to a question (Lowenstein, 2010).

It allows family members not only to get to know each other better, but also to develop skills in asking each other questions, understanding that there are things that are similar between family members and things that are different. Finally, it helps make the point that family members, especially parents, may not know as much about each other as they think they do.

Finally, it helps make the point that family members, especially parents, may not know as much about each other as they think they do.

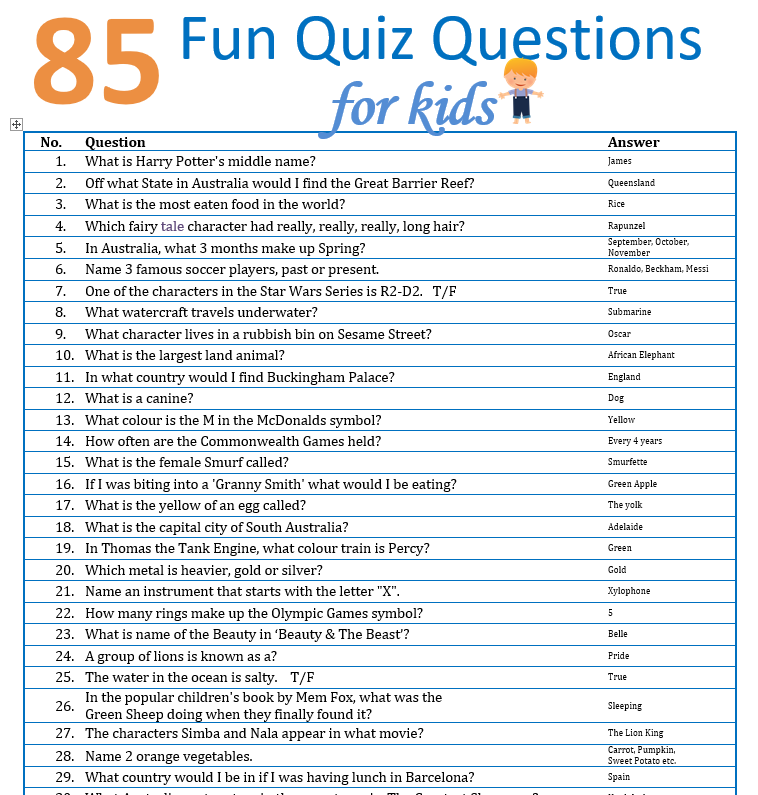

Create at least 20 questions, such as:

- What is your favorite color?

- What is your favorite dessert?

- Who do you think gets angry the most in the family?

- Who cries the most in the family?

- Who laughs the most in the family?

- Who watches TV the most in the family?

- Who gives the most support to you?

- Who gives Mom/Dad the most support?

- What would the family member on your left like to get for their birthday?

- Who is the best at following the rules?

- Who sets the most rules?

To use these games effectively, it helps to make sure the questions connect to a family goal. The game can move reasonably quickly, giving everyone a turn and ending the session on a high note. Finally, many existing games, especially games and activities the family is already familiar with, can be adapted to provide an opportunity for a meaningful conversation.

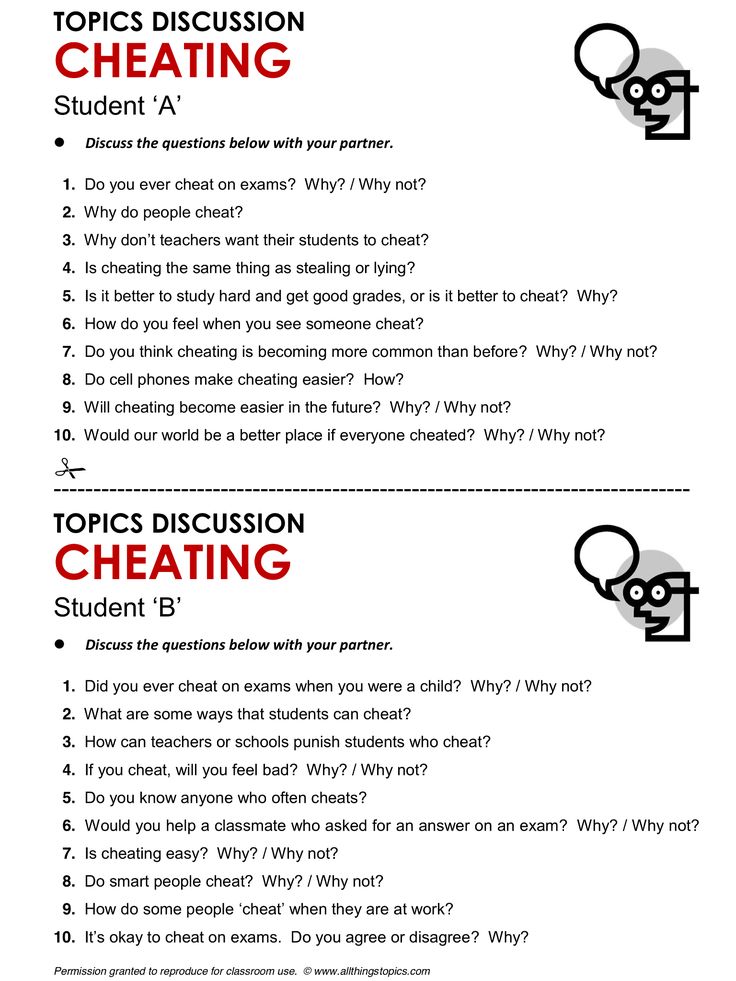

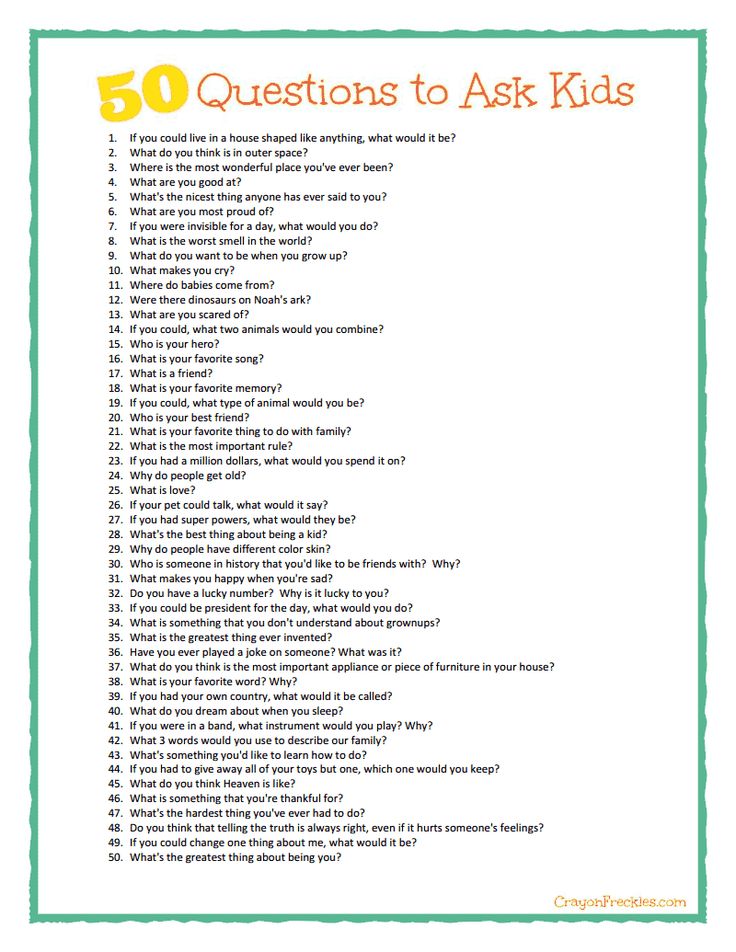

Therapeutic Questions for Youth

There is no time more ridden with unanswered questions and throbbing with urgency as in our youth.

As teens grapple with discovering their identities and setting directions for their lives, it is an excellent opportunity to set standards for a self-reflective and inquisitive mind that is open to honest discussions and not afraid to ask questions.

As the saying goes, if we ask good questions, we get better answers. Below is a list of questions most frequently used in therapy with pre-teens to young adults and that anyone might find interesting.

- What is the best compliment you have received?

- In your opinion, what is the best song ever written?

- If you could know one thing about the future, what would it be?

- What is something you feel nervous about right now?

- What is your happiest memory?

- What is something that you did that you are proud of?

- If someone’s underwear were showing, would you tell them?

- I get mad when…

- What calms you down when you get angry or upset?

- What is your favorite animal and why?

- My favorite sound is…

- What is your favorite green thing?

- If you could travel anywhere in the world, where would you go and why?

- If your house was burning down, what one item would you grab and why?

- Name two anger management techniques.

- Name two positive values.

- Name two ways you can show self-control in the school setting.

- What would be the title of your autobiography?

- Do you think people talk differently online than they do in person? Why?

- What is one item you can’t live without?

- What would you do if you were hungry and a lunchbox was left open and unattended?

- What is better, giving your money or giving your time?

- If you could add, change, or cancel one rule in your school, what would it be?

- What does “habit” mean, and why is it hard to change?

- Who do you trust the most and why?

- Where do you feel the safest and why?

- If you could change one rule that your family has, what would it be and why?

- What is one word you would use to describe your family and why?

- How do you think others view you and why?

- If you could travel back in time to years ago and visit your younger self, what advice would you give yourself?

- What five words best describe you?

- If you could make one rule that everyone in the world had to follow, what would it be and why?

- What does respect mean to you? Give an example.

- What do you like the most about yourself?

- If you could give one gift to every child in the world, what would it be and why?

- What do you think is the most important job in the world? Why?

- Tell us about a time when you felt sad. What helped get you through it?

- What is the first symptom you notice when you feel mad?

- Give two examples of acts of kindness.

- Who is someone you consider a real-life hero and why?

- Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

- Who do you wish you had a better relationship with, and what would make it better?

- Share a time where you sought attention in an appropriate way. And in a negative way?

- Choose one person in this room and compliment them.

- Give two examples of communication with a teacher who accuses you of something you didn’t do.

- Talk about a time when you witnessed someone being teased. What effect did the teasing have on that person?

One assessment tool that is particularly useful in work with young people with complex needs is the ecomap. It is a visual representation of current family relationships and also community and social networks where clients are encouraged to identify whether their relationships with their peers, school, social clubs, professionals, are strong, weak, or stressful. See these templates.

It is a visual representation of current family relationships and also community and social networks where clients are encouraged to identify whether their relationships with their peers, school, social clubs, professionals, are strong, weak, or stressful. See these templates.

15 Therapeutic Questions for Group Therapy Discussions

Group therapy serves two distinct goals. While it addresses exploration of issues very much in the same way that individual therapy does, it also serves the purpose of finding ourselves in the environment where we feel less isolated from other people because many of those in the room share similar struggles.

Just as in individual therapy, clients often enact the same tendencies they bring to all their other relationships, and the client interaction within a group can often be a good reflection of how they show up in the relationships with other people in their lives (Yalom, 1983).

While the therapist is trained in delivering structure for the discussion and guiding the questions, the biggest benefit lies in the exchange between participants. Leaders within the group are usually appointed and tasked with looking for commonalities among members and encouraging everyone to be supportive of each other.

Leaders within the group are usually appointed and tasked with looking for commonalities among members and encouraging everyone to be supportive of each other.

Most group therapies are done in a round-robin discussion format. Rules of conduct are established and adhered to, roles assigned for leaders of the group, and the room set up usually in a circle to encourage collaboration and everyone having a voice. Questions used in group therapy often focus on very much the same themes as individual therapy and include the reasons for being there and the expectations for the future.

- Let’s start by spending a few minutes talking about the benefits of group therapy and what positive psychology groups are about.

- Let’s go around and have each member tell us what you expect to get out of the group

- Where else might you have been at this moment if you hadn’t come to this group session today?

- What might you have chosen to do?

- Is it your own decision to come here, or did someone else encourage you to do so?

- How do you feel about coming here each week?

- What do you like best about this session?

- Is there something you don’t enjoy about this group session?

- Are you particularly looking forward to anything?

Depending on the purpose of the group, be it anger management, bereavement, substance abuse, etc. , the content and the topics of discussion may vary. Although in a typical session, several topics and questions are provided, group leaders need not ask all questions or address all topics; instead, questions and topics should be selected as they relate to what is happening in the group. Some general questions could include:

, the content and the topics of discussion may vary. Although in a typical session, several topics and questions are provided, group leaders need not ask all questions or address all topics; instead, questions and topics should be selected as they relate to what is happening in the group. Some general questions could include:

- What brought each of you into the group?

- Tell us two or three words that best describe you.

- Now, thinking about those words, how do they relate to why you are here?

- What is your favorite thing about yourself, something that makes you feel positive and proud to be you?

- Is there something new that has happened in your life recently?

Homework assignments and progress logs can be used between sessions, and educational material and handouts may be distributed. Many sessions start with reviews of progress and end with a recap of the activities.

A Take-Home Message

The value of deep, probing questions need not be reserved for the therapy session. There is no reason why we can’t have more of these healing conversations in our lives, but it is both an art and science and requires some practice. We can all get better at asking questions we want answers to, and applying the therapeutic approach to the process of self-discovery can prove a worthwhile endeavor.

There is no reason why we can’t have more of these healing conversations in our lives, but it is both an art and science and requires some practice. We can all get better at asking questions we want answers to, and applying the therapeutic approach to the process of self-discovery can prove a worthwhile endeavor.

The scientist is not a person who gives the right answers, he’s one who asks the right questions.

Claude Levi-Strauss

What questions do you think are important to ask, in therapy or not?

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

- Gottman, J. M., & Silver, N. (2015). The seven principles for making marriage work: A practical guide from the country’s foremost relationship expert. Harmony.

- Lambert, M., & Barley, D. E. (2001). Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(4), 357–361.

- Levy, A. G., Scherer, A. M., Zikmund-Fisher, B. J., Larkin, K., Barnes, G. D., & Fagerlin, A. (2018). Prevalence of and factors associated with patient nondisclosure of medically relevant information to clinicians. JAMA Network Open, 1(7).

- Lowenstein, L. (2010). Creative family therapy techniques: Play, art, and expressive activities to engage children in family sessions. Champion Press.

- Rogers, C. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy.

- Yalom, I. D. (1983). Inpatient group psychotherapy. Basic Books.

4 Scales to Measure Satisfaction with Life (SWLS)

Reflecting on our sense of happiness in different key areas of life can be difficult, especially if our life is seemingly all going well.

Sometimes feelings of unhappiness or dissatisfaction just seem to find us, and it’s up to us to take the time to explore why this might be.

How you do that will depend on a number of different things, but if you’re struggling to get to grips with it, there are plenty of psychology tools and resources to help.

One of those tools is the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS), and in this article, we’re going to take a closer look at what this is and what it can do for you.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

- The Satisfaction With Life Scale

- What Does the Questionnaire Measure Exactly?

- How Does the Scoring Work?

- A Look at the Reliability and Validity of the Test

- About Ed Diener and the Authors

- The Wheel of Life by PositivePsychology.com

- Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS)

- The Multidimensional Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS)

- A Take-Home Message

- References

The Satisfaction With Life Scale

The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) was first created by researchers Diener, Emmons, Larsen, and Griffin (1985) and published in an article in the Journal of Personality Assessment.

The scale was developed as a way to assess an individual’s cognitive judgment of their satisfaction with their life as a whole. The SWLS is a very simple, short questionnaire made up of only five statements.

Participants completing the questionnaire are asked to judge how they feel about each of the statements using a seven-point scoring system, with 1 being “strongly disagree” and 7 being “strongly agree.”

Below, I’ve outlined what these statements are:

- In most ways, my life is close to my ideal.

- The conditions of my life are excellent.

- I am satisfied with my life.

- So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life.

- If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing.

Once you’ve assigned a score from 1 to 7 to each of the statements, you tally up your final score for an indication of how satisfied you are overall with life.

As you can see, the SWLS won’t take up a lot of your time to complete! But it can be a really useful instrument in supporting you to reflect on your life, overall satisfaction, and in beginning to think about areas you might need to spend a bit more time exploring.

You can download a full copy of the SWLS, including how to tally and score.

What Does the Questionnaire Measure Exactly?

When it comes to a sense of subjective wellbeing, researchers have asserted that it consists of two main components: the emotional component and the cognitive component (Diener, 1984; Veenhoven, 1984).

The cognitive component has been more closely conceptualized with life satisfaction (Andrews & Withey, 1976), yet despite this, had not previously received much attention for research. Diener et al. (1985) sought to address this and through developing the SWLS, they created a strong tool in the measurement of the cognitive components they felt reflected a subjective sense of wellbeing and life satisfaction.

The SWLS is not designed to help you understand satisfaction in any one specific domain of life, such as your job or relationships; instead, it has been developed to help you get a sense of your satisfaction with your life as a whole.

Although the questionnaire doesn’t measure individual components, it can be an excellent starting point, encouraging deeper thought and exploration of the specific areas of life that may be causing you a sense of dissatisfaction.

How Does the Scoring Work?

The scoring for the SWLS works quite simply, by adding up the total of the numbers you score against each of the statements. So, remembering that 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree, the higher your score, the higher your sense of life satisfaction as a whole.

As a guide, your total score means:

- 31–35 = Extremely satisfied

- 26–30 = Satisfied

- 21–25 = Slightly satisfied

- 20 = Neutral

- 15–19 = Slightly dissatisfied

- 10–14 = Dissatisfied

- 5–9 = Extremely dissatisfied

Pavot and Diener (2013) created a more in-depth description of what your score means for your sense of life satisfaction. Very briefly, we’ve written up what they had to say, but it’s worth accessing the original documents.

- 31–35 Extremely satisfied

If you score this high on the SWLS, it means you have a strong love of your life and feel that things are going really well for you. This does not mean to say that you feel your life is perfect, but you are content with how things are and/or feel any challenges are temporary and can be managed.

A high score does not indicate that you are complacent about your sense of satisfaction, and it is likely you understand that challenge is a pathway to growth and greater satisfaction.

- 26–30 Satisfied

If you score in this range, you likely feel that most things in your life are going really well, but there may be one or two key areas you wish to change. You understand that your life is not perfect and respect that any challenges are also an area for further growth and exploration.

- 21–25 Slightly satisfied

If you score in this margin, you’re in good company. The researchers assert that this is where the majority of people score themselves. This score means you are generally satisfied, on an average day-to-day basis; however, there are areas you’d really like to improve.

This score means you are generally satisfied, on an average day-to-day basis; however, there are areas you’d really like to improve.

Rather than there being one or two things that you feel would give you greater satisfaction, you might feel that small improvements across all domains of your life would lead to a higher sense of life satisfaction.

- 20 Neutral

A score of 20 – bang in the middle of the scale – means you’re likely pretty neutral about your sense of satisfaction about your life. You might not give too much thought to what does or doesn’t need improving, and you’re quite content where you are.

- 15–19 Slightly dissatisfied

A score in this range might mean that you tend to feel dissatisfied more than satisfied on a day-to-day basis, and there are several significant areas for improvement. It might also indicate that you’re generally content, but there is one area of life where you feel deeply unsatisfied, which is creating a lower score.

A score in this margin requires further thought and reflection on where improvements need to be made to increase your sense of satisfaction.

- 10–14 Dissatisfied

A dissatisfied score tends to mean you’re feeling substantially dissatisfied about your current circumstances. This might be deep dissatisfaction across all areas of life or that two or three areas are far worse than the others.

It’s worth reflecting to see if your dissatisfaction is due to a recent event or situation, which may be temporary, or if this is a chronic experience because you are not living the life you truly want.

- 5–9 Extremely dissatisfied

As you may have guessed, a score at the very low end of the scale means that you are extremely dissatisfied with your current life circumstances. Again, if this score is due to a recent hard blow in life, such as bereavement, then things may get better over time with the right support.

However, a score this low tends to be an indication of dissatisfaction across multiple areas of life and is a good starting point to begin reflecting on why that might be.

A Look at the Reliability and Validity of the Test

The SWLS is one of the most widely used measurements for life satisfaction. The shortness and ease of being able to administer the scale to achieve foundation results is key to this, but how reliable does that actually make it?

In developing the scale, Diener et al. (1985) tested it widely and reported that it does have good psychometric properties, as well as a high test–retest coefficient (meaning participants who completed the scale more than once demonstrated the same results consistently).

Further research has confirmed this reliability against other measures of life satisfaction (Pavot et al., 1991, Pavot & Diener, 2008) as well as other measures for happiness (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999). It has also correlated well with scales measuring the meaning of life (Steger et al., 2006) and scales measuring hope (Bailey & Synder, 2007).

Several other studies have also sought to use the scale across different cultural groups to test its validity, with positive results. Galankis et al. (2017) used the scale across a sample of 1,797 Greek natives and found their results in line with the original researcher’s studies, as well as other studies exploring cross-cultural uses for the SWLS.

Galankis et al. (2017) used the scale across a sample of 1,797 Greek natives and found their results in line with the original researcher’s studies, as well as other studies exploring cross-cultural uses for the SWLS.

The only part of the scale that has been questioned in the research is the use of the fifth statement, as researchers believe it has a weaker association with life satisfaction and instead causes participants to reflect on the desire to change rather than their current sense of life satisfaction (Pavot & Diener, 1993).

About Ed Diener and the Authors

Lead researcher for the SWLS, professor Ed Diener, was sometimes referred to by his nickname ‘Dr. Happiness,’ owing to his astonishing body of research and academic contributions to the study of happiness and wellbeing.

He was a professor of psychology at the University of Virginia and University of Utah, as well as a senior scientist with the Gallup Organization. He published over 350 academic articles and books and was also the editor of three scientific journals.

As well as happiness and life satisfaction, Diener studied the factors that influence these two areas, including financial health, family upbringing, personality, relationships, and work. He studied these topics across 166 different nations and explored some of the cultural components behind individual happiness.

The other researchers and authors of the SWLS include:

- Robert A. Emmons: A global leading expert and researcher on gratitude. He is currently a professor of psychology for the University of California and the founding editor-in-chief for The Journal of Positive Psychology. Emmons has also authored several books, including The Little Book of Gratitude.

- Randy J. Larsen: A highly regarded expert and academic in the field of positive psychology, Larsen is the William R. Stuckenberg Professor of Human Values and Moral Development, as well as the chair of the psychology department with Washington University. His research has focused on emotions, specifically exploring how we experience emotions differently as individuals.

Where Can You Find the SWLS?

The SWLS is widely available for free online, and while there are a few slight variations, each has the same outcome or measurement at its heart.

One of the best places to find the scale and its scoring is on the Ed Diener Lab website.

The Wheel of Life by PositivePsychology.com

While the SWLS can offer you an indication of your life satisfaction on a more overall scale, there are other tools and resources that can help you to further explore your sense of satisfaction in specific domain areas of your life.

One such tool is the wheel of life (Whitworth et al., 1998).

Once you have your score from the SWLS, you can then begin to reflect more fully on where you might like to make changes to build a greater sense of life satisfaction.

This tool will help you do that, as it requires that you identify the different life domains that are important to you – such as career, family, and relationships – and to then give each of these individual domains a rating from 1 to 10, with 1 being “not at all satisfied” and 10 being “completely satisfied. ”

”

PositivePsychology.com has put together a free ready-to-use resource with a Wheel of Life containing 10 key domains for life satisfaction.

These are:

- Money & finance

- Career & work

- Health & fitness

- Fun & recreation

- Environment

- Community

- Family & friends

- Partner & love

- Growth & learning

- Spirituality

The wheel is a fantastic resource from the SWLS, as not only does it encourage you to think more deeply about where you might be dissatisfied with life, it also creates a great visual representation.

Once you have your scores for each of the 10 domains, you can reflect on where you have given the lowest scores, why these are low scores, and what you might be able to do to start making positive changes and improve your sense of life satisfaction.

Ask yourself:

- Why does this domain need attention?

- What would it take to raise your satisfaction with one score in this domain?

- What can you do to raise your satisfaction in this domain?

Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS)

The Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS) is relatively similar to the SWLS, except it was purposefully designed to be used with children and young people aged 8–18 years old (Huebner, 1991).

It contains seven statements and asks young people to give each statement a score from 1 to 6, with 1 being “strongly disagree” and 6 being “strongly agree.”

The exception with the SLSS is that the last two questions are reverse scored (so 1 becomes “strongly agree” and 6 becomes “strongly disagree”).

There are a few different variants, but the statements are along the following lines:

- My life is going well.

- My life is just right.

- I would like to change many things in my life.

- I wish I had a different kind of life.

- I have a good life.

- I have what I want in life.

- My life is better than most kids.

As with the SWLS, when each statement has been assigned a score, a summary total is calculated to provide a numerical guide to the student’s sense of life satisfaction.

The Multidimensional Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS)

Following on from the SLSS, Huebner (1994) went on to create the Multidimensional Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS). The MSLSS is a longer scale assessment for measuring students’ satisfaction with life.

The MSLSS is a longer scale assessment for measuring students’ satisfaction with life.

It contains 40 items/statements and can be used either with individuals or in a group setting.

Participants are asked to rate their response to the statements using the following numerical grading scale:

1 = Never

2 = Sometimes

3 = Often

4 = Almost always

The MSLSS was developed in response to a growing interest in promoting positive psychological wellbeing among young people and students (Sarason, 1997). With its use, Huebner hoped to:

- Create an individualized profile of a child’s life satisfaction across specific domains

- Provide an assessment of general life satisfaction

- Demonstrate acceptable and reliable psychometric properties

- Show the meaningfulness of the five specific domains it covers: family, friends, school, living environment, and self

- Provide a tool that can be used effectively with a wide range of young people, across different ages

Below, I have provided a brief outline of the types of statements that it includes:

- Family:

- I enjoy being at home with my family.

- My family gets along well together.

- I enjoy being at home with my family.

- Friends:

- My friends are nice to me.

- My friends are great.

- School:

- School is interesting

- I learn a lot at school.

- Living environment:

- I like where I live.

- I like my neighbors.

- Self:

- I am fun to be around.

- I like myself.

To score the MSLSS, you tally up the total score for each specific domain. A higher score indicates a higher level of life satisfaction – similar to the SWLS.

You can also compare domains by tallying the individual scores and then dividing the score by the number of statements in that specific section, to create a mean score.

You can find out more about the MSLSS and get a copy of the full 40 statements and scoring instructions.

A Take-Home Message

I hadn’t come across the SWLS before researching and writing this article, and I have found it a great tool to use personally. Its ease and accessibility mean everyone can benefit from the foundational insights it might offer you about how you feel about your current life situation.

Its ease and accessibility mean everyone can benefit from the foundational insights it might offer you about how you feel about your current life situation.

If there’s one thing I’d like you to take away from this article, it’s that the SWLS and the wheel of life are just the beginning. Use them as resources to help your thought processes and be sure to reflect on your results. We are all in control of our own life satisfaction; if yours isn’t quite where you’d like it to be, you have the ability to change that.

What did you think of the SWLS, and has it helped you? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

- Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being America’s perception of life quality. Plenum Press.

- Bailey, T. C., & Snyder, C. R. (2007). Satisfaction with life and hope: A look at age and marital status.

The Psychological Record, 57(2), 233–240.

The Psychological Record, 57(2), 233–240. - Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575.

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

- Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial development of the Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale. School Psychology International, 12(3), 231–240.

- Huebner, E. S. (1994). Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychological Assessment, 6(2), 149–58.

- Galankis, M., Kakioti, A., Pezirkianidis, C., & Karakasidou, E. (2017) Reliability and validity of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) in a Greek sample. The International Journal of Humanities & Social Studies, 5(2).

- Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation.

Social Indicators Research, 46(2), 137–155.

Social Indicators Research, 46(2), 137–155. - Pavot, W., Diener, E., Colvin, C. R., & Sandvik, E. (1991). Further validation of the Satisfaction With Life Scale: Evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57(1), 149–161.

- Pavot, W. & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 164–172.

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152.

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2013). Happiness experienced: The science of subjective well-being. In S. A. David, I. Boniwell, & A. Conley Ayers (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 134–151). Oxford University Press.

- Sarason, S. D. (1997). Forward. In R. Weissberg, T. P. Gullotta, R. L. Hampton, B. A. Ryan, & G. R.

Adams (Eds.), Enhancing children’s wellness (vol. 8, pp. ix–xi). Sage.

Adams (Eds.), Enhancing children’s wellness (vol. 8, pp. ix–xi). Sage. - Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93.

- Veenhoven, R. (1984). Conditions of happiness. Kluwer Boston Academic.

- Whitworth, L., Kimsey-House, H., & Sandahl, P. (1998). Co-active coaching. Davies-Black.

questions for the first consultation and preparation for it

home / Blog / Cheat sheet for a psychologist: questions for the first consultation and preparation for it

Reading time: 6 minutes

|

April 27, 2022

Receive our articles in messengers

The article was created with the participation of an expert

Lesnitskaya Olga Nikolaevna

Master of Psychology, practicing psychologist, specialist in the field of individual counseling, gestalt therapy, systemic phenomenological psychotherapy, musical art therapy.

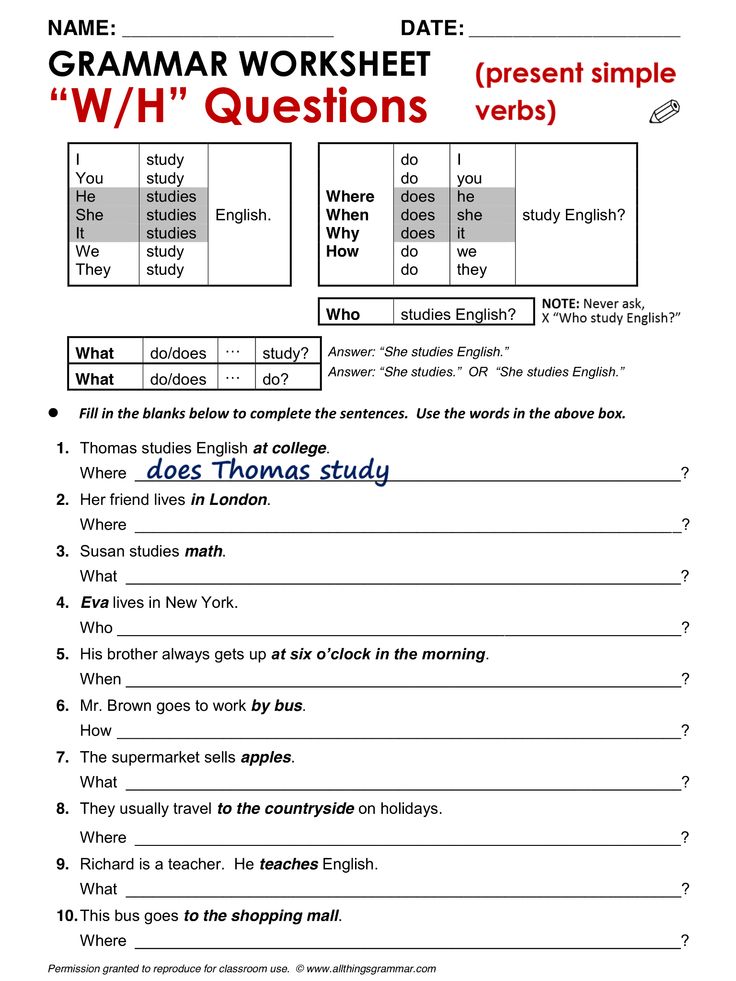

Questions are the main tool in the work of a psychologist of any direction. With their help, the specialist helps the client to open up and clarify the request. Consider a sample list of questions that you can ask before and during the first consultation.

Questions before the session: when calling or chatting in instant messengers

It is important to determine the client's request even before the consultation in order to understand whether you work in this niche, with this category of clients and whether you can help at all. These questions can be asked by phone / text prior to the consultation, or at the first free session if you have one:

- What is your name / how can I contact you?

- How old are you?

- Who needs help - adult, child, couple?

- What made you turn to a psychologist? nine0030

The answers give a first impression of the client and his problem.

Questions for consultation will always be at hand

Get them by mail

Olga Lesnitskaya, our teacher-expert, Master of Psychology and a practicing psychologist, told us how to communicate with clients in instant messengers.

Now the majority of clients do not call, but write to instant messengers. The world is changing, that's normal. And it is important for us, psychologists, to take this into account and build it into our practice. Through messages, a specialist can also find out primary information, agree on meeting conditions and make an appointment with a client. nine0003

You can ask the person to write briefly about what brought them to you. If the topic falls under your specialization, you can set the conditions for the first meeting.

After this, it is important to give the person the opportunity to ask questions. Organizational questions must be answered. Questions that relate to the client's difficulties can be answered briefly or offered to be discussed during the consultation.

It happens that a person needs to think about the working conditions, and he does not answer or writes: "I need to think." It happens that the conditions are not suitable - this is normal. nine0003

What to do if a person does not answer, the psychologist decides based on personal ethics. In any case, you should not write to the client about your intentions and expectations in the forms: "When will you come?", "Waiting for you on Wednesday." Sometimes you can politely ask and offer your help, for example: “Hello, if my conditions do not suit you, write about what would suit you, and I will try to recommend colleagues.”

In any case, you should not write to the client about your intentions and expectations in the forms: "When will you come?", "Waiting for you on Wednesday." Sometimes you can politely ask and offer your help, for example: “Hello, if my conditions do not suit you, write about what would suit you, and I will try to recommend colleagues.”

The main task of a specialist in writing through messages is to navigate the possible topic of the client's difficulties, to give information about his work. It is important to stay within the boundaries and not start therapy. nine0003

Lesnitskaya Olga Nikolaevna

At the end, you can ask: “How did you hear about my services?” This question will help you understand which channel for promoting the services of a psychologist works best. In the future, you can exclude channels with low efficiency. It will also help to better understand the audience: where clients “live” and how they find a psychologist.

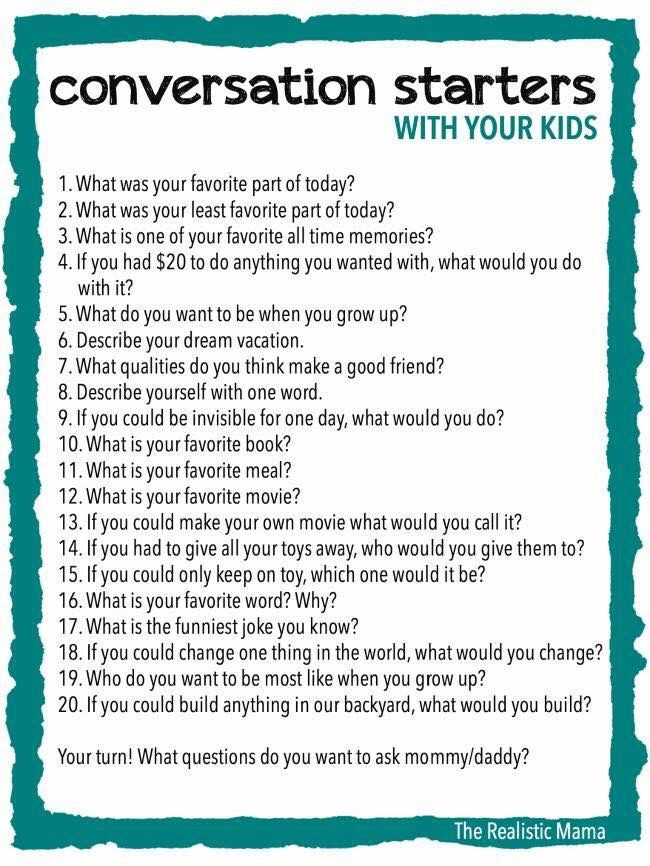

Questions to start a conversation and create a relaxed atmosphere

Let's analyze separately the introductory questions for the first online consultation and face-to-face session. nine0003

Questions for the first online consultation:

- Can you hear and see me well?

- Is it convenient for you to talk, nothing interferes, does not distract?

- How do you feel?

It is important to make sure that nothing interferes with the consultation on the technical side. And the question about well-being is an introductory one that sets you up for a conversation.

See also:

Difficulties of psychological online counseling. Dealing with an expert how to solve problems nine0003

Questions for face-to-face meeting:

- How did you get there?

- Is it easy to find an office?

- Are you comfortable sitting?

- Would you like water, tea, coffee?

You can ask or say something neutral, for example: “It's such a nice weather today, isn't it?” It is important not to rush right off the bat, but to smoothly approach the topic of the consultation.

Seeing a psychologist is a stressful situation for most clients. Opening questions help ease anxiety and tension. nine0003

Clarification Questions

Take about 5 minutes for an introductory part and proceed to clarify the query:

- What brought you to me / what is bothering you?

- How long ago did this start?

- At the time this started, were there any changes in your life?

- Have you already consulted a psychologist and what was the outcome of your appeal?

- What did you try to solve the problem?

- Has the problem always manifested itself the way it does now, or has something changed? nine0030

- How often does the problem come up? When does it get stronger and when does it get weaker?

- How does the problem affect your life, its individual areas?

- How do you feel when you talk about a problem?

- What has already been done to solve the problem? What helped and how, and what did not help.

- Have you told anyone about your experiences?

- Is there anyone who supports you?

- Why did you decide to turn to a psychologist right now? nine0030

- What do you expect from today's consultation and therapy in general?

- How do you see our work and what are you ready to do to solve the problem?

- How do you see the result of therapy, are there any criteria by which you can determine that the problem has been solved?

- How long do you expect to solve the problem?

Ask any questions that will help you better understand the client, their condition and problem. All questions can be divided into 3 groups: how, why and what. They help to understand the processes that take place in the life of the client and inside him, his needs and desires, specific manifestations. nine0003

Example. The client is worried that he often yells at others. HOW it happens: “When they don’t understand me the first time, I turn to screaming. ” WHY the client shouts: "To be heard and understood." WHAT the client feels: “Powerlessness and resentment when they don’t notice me, they don’t understand me.”

” WHY the client shouts: "To be heard and understood." WHAT the client feels: “Powerlessness and resentment when they don’t notice me, they don’t understand me.”

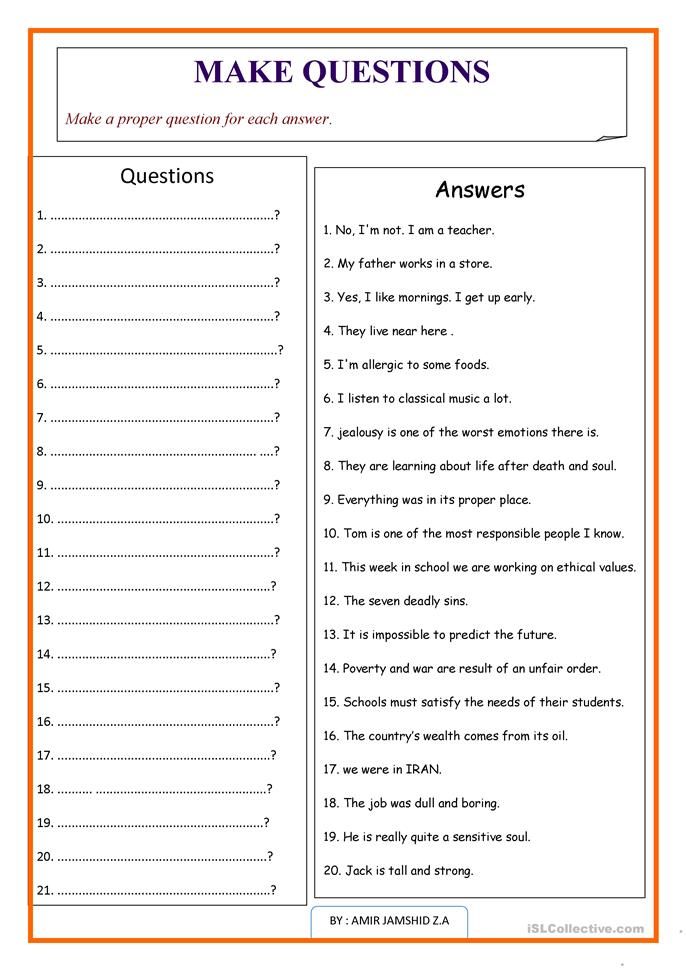

Questions for debriefing

The purpose of the first consultation is to get to know the client, to determine the true request with which you will work. It happens that in the process the request changes. For example, a client came up with the problem “I can’t build a relationship”, and during the consultation it turned out that there was a fear of intimacy behind this - this is a request that needs to be worked on. nine0003

Also at the first consultation it is necessary to determine the possibilities of therapy specifically for this client. Therefore, at the end of the session, it is important to summarize:

- What was the consultation about for you?

- What did you leave with, what did you learn?

- Has your condition changed? If so, how?

- Maybe you want to say something else, remember something important?

- Do you want to continue working?

- What would you like to discuss next? nine0030

- Do you want to ask me something?

Remember that psychological counseling is a creative process. It is important to follow the client, and not tailor the consultation strictly to the algorithm. It is important to pay attention not only to the client's responses, but also to his facial expressions, gestures, tone of voice, rate of speech and other non-verbal signs.

It is important to follow the client, and not tailor the consultation strictly to the algorithm. It is important to pay attention not only to the client's responses, but also to his facial expressions, gestures, tone of voice, rate of speech and other non-verbal signs.

Useful materials:

- Algorithm for the first consultation with a psychologist: with examples and advice from practitioners nine0029 Psychologist and client: how to build relationships correctly

- 6 ethical principles that will keep the reputation of a psychologist. With examples

- Interview with Olga Lesnitskaya: about Gestalt therapy, self-discovery and fear of the unknown

- Who is a Gestalt therapist and how to become one

The article was created with the participation of an expert

Lesnitskaya Olga Nikolaevna

Master of Psychology, practicing psychologist, specialist in the field of individual counseling, gestalt therapy, systemic phenomenological psychotherapy, musical art therapy.

what to do, what to say and how to behave

So, you have decided to go to psychotherapy. How not to be afraid of the first dose, prepare for it and get the maximum effect? We share information and advice.

- What does it look like in practice? nine0030

- How to prepare for the first appointment with a psychotherapist?

- A few days before the first appointment:

- A few hours before admission:

- During the reception

"Therapist's appointment" can sound intimidating. I still remember stories about punitive psychiatry in the USSR, when people were registered and deprived of legal capacity. It may seem that the task of this doctor is to diagnose you and prescribe pills, which, moreover, cause addiction. And in the worst case - "upech" in a psychiatric clinic. nine0003

nine0003

Reality is very far from horror stories. Not only people with serious disorders go to a therapist. A professional psychotherapist always observes three conditions in his work: security client, confidentiality and evidence-based approach .

What does it look like in practice?

Psychotherapy is not like consulting with an ordinary doctor. Strictly speaking, a psychotherapist is not a doctor. He may have a medical degree, but this is not a prerequisite. nine0003

Moreover, having such an education does not guarantee better help. Even if a person graduated from a medical university, he needs to additionally study to become a psychotherapist. Working with the mental state of a person, his emotions and thoughts is not a “treatment”.

The appointment takes place in person, in a specially equipped office, or online. The psychotherapist's office also does not look like a doctor's office - it looks more like a small living room. There are several comfortable chairs and tables in it, soft comfortable lighting is set up. If you plan to work with a therapist online, try to recreate a similar atmosphere in the room. nine0003

There are several comfortable chairs and tables in it, soft comfortable lighting is set up. If you plan to work with a therapist online, try to recreate a similar atmosphere in the room. nine0003

Psychotherapy is a conversational practice. This means that most of the time you will be talking to a specialist. But this will not be an ordinary conversation, as with a friend - therapeutic methods, exploration of your inner world and work on yourself will be woven into it. Everything you talk about is confidential. This means that the therapist does not disclose information even that you came to him. Even if close relatives ask.

Some approaches require homework . Since therapy is always a two-way process, it is very important to work on yourself outside of the office. For example, a therapist may ask you to keep a diary of emotions as you work on understanding and expressing them. If you are working with others, your homework may be to apply the new communication skills you learned in therapy.

How to prepare for the first appointment with a psychotherapist?

You may be nervous before your first appointment - this is normal. How to prepare for it in order to reduce stress levels and make psychotherapy more productive? nine0003

A few days before the first appointment:

1. State what is bothering you

No one requires you to state your request to a psychotherapist in a clear, psychological language. But still try to determine what you do not like and what you would like to change. Try not to limit yourself to the phrases "I feel bad" or "I think I'm going crazy." What exactly are you feeling?

2. Think about what result you would like to achieve

Psychotherapy does not have a universal goal. Each person imagines happiness, success and comfort in his own way. Imagine how life has to change for you to enjoy it. What would you like to get rid of, and what would you like to integrate? How will you know that it worked?

3. Find out everything you need to know about psychotherapy

Find out everything you need to know about psychotherapy

It is better to dispel the myths in advance and find out how therapy works and what happens in it. They can help with this:

- The podcast “I'm listening to you” is a real recording of therapy sessions with comments from a client and a psychologist. nine0030

- A guide to the areas of psychotherapy - to understand what areas exist, how they differ, with what and how they work.

- Blog and Instagram Alter - simply and honestly about psychotherapy, psychology, relationships and self-care.

- The experience of your friends and family. Talk to them if they are willing to share: why they decided to see a therapist, how the work was structured and what was achieved.

Hours before appointment:

1. Do not use anything that alters consciousness

Even "50 grams for courage". Sobriety is a very important condition of therapy.

2. Refresh something you would like to talk about

Refresh something you would like to talk about

It is not necessary to have a clear plan. Just keep in mind the most basic things you think a therapist should know.

3. Tune in to a conversation

Try to relax and tune in to an open conversation. You don't have to tell your therapist everything right away, but it's not in your best interest to shut yourself up either. If you find it difficult to talk about yourself, warn the specialist about it. He will adjust the pace and the therapy techniques used for you. nine0003

During your appointment

1. Track your condition

The best way to know if a specialist is right for you is to listen to yourself. How comfortable are you? Are there any feelings of shame, guilt, constraint? Do you want to share personal information specifically with this person, or is there some kind of internal block?

2. Give the therapist feedback

If you don't like something, talk about it directly.