Stages of grief definition

How to Understand Your Feelings

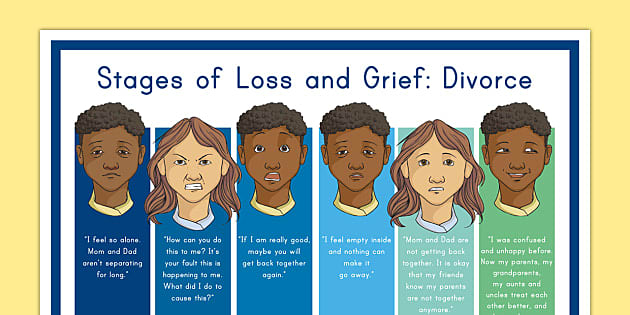

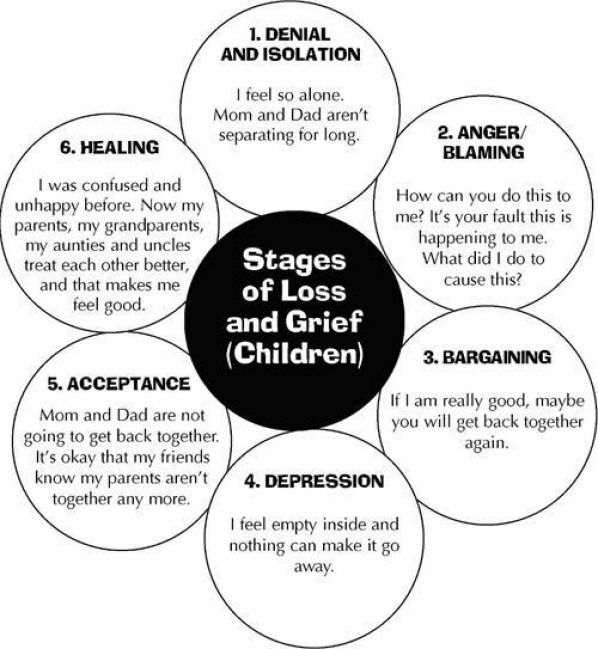

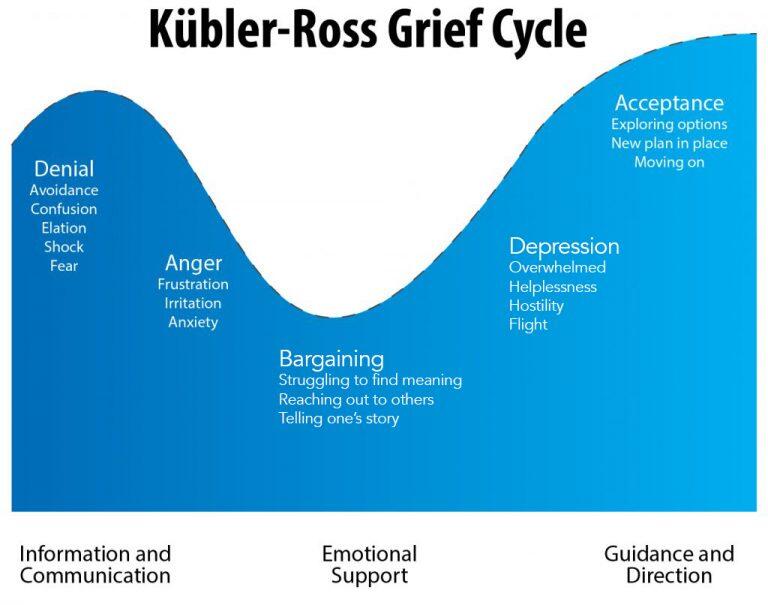

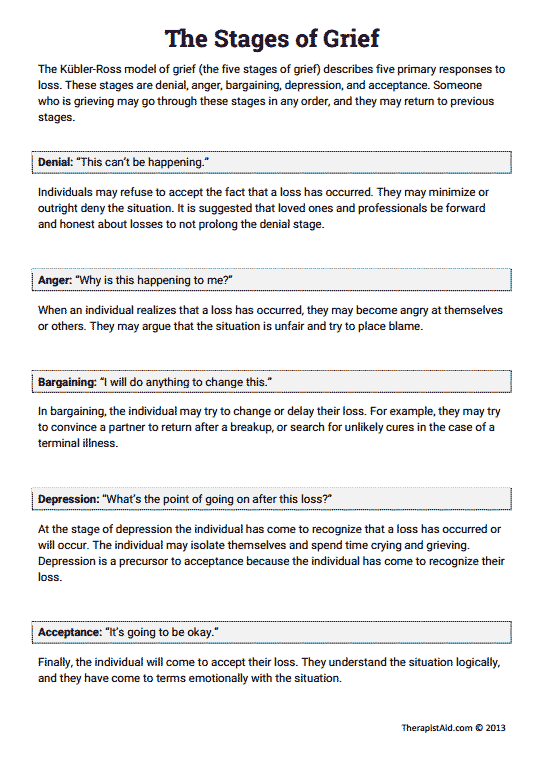

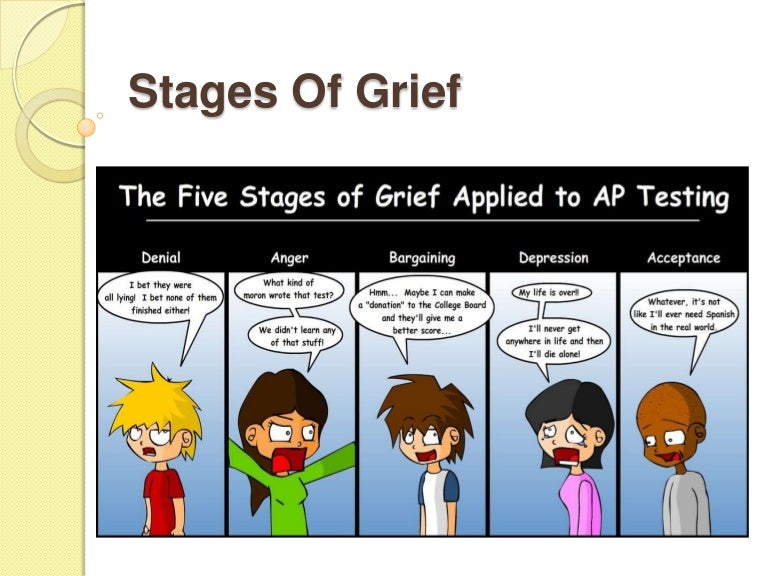

Grief is universal. At some point, everyone will have at least one encounter with grief. Elizabeth Kbler Ross wrote in her book “On Death and Dying” that grief could be divided into five stages. They were originally devised for people who were ill, but these stages have been adapted for coping with grief in general.

Grief is universal. At some point, everyone will have at least one encounter with grief. It may be from the death of a loved one, the loss of a job, the end of a relationship, or any other change that alters life as you know it.

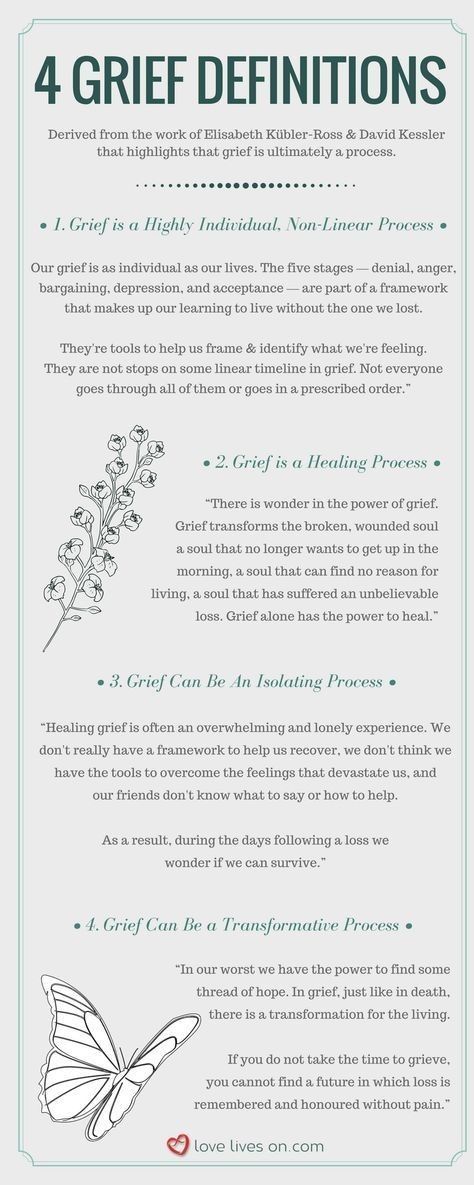

Grief is also very personal. It’s not very neat or linear. It doesn’t follow any timelines or schedules. You may cry, become angry, withdraw, or feel empty. None of these things are unusual or wrong.

Everyone grieves differently, but there are some commonalities in the stages and the order of feelings experienced during grief.

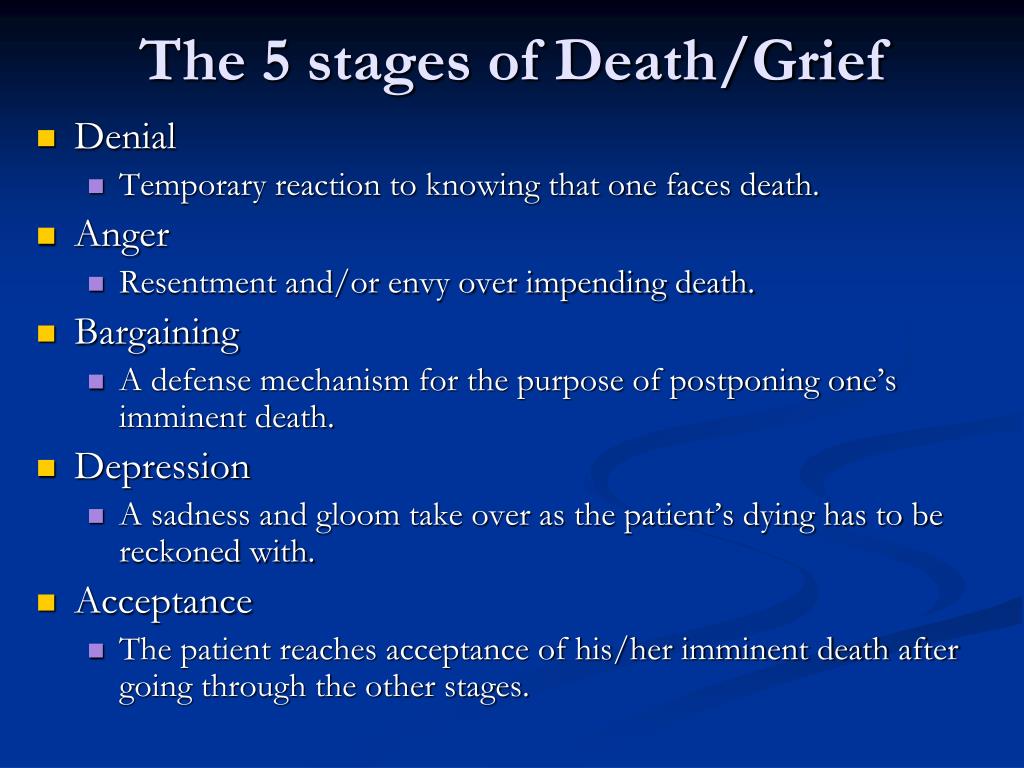

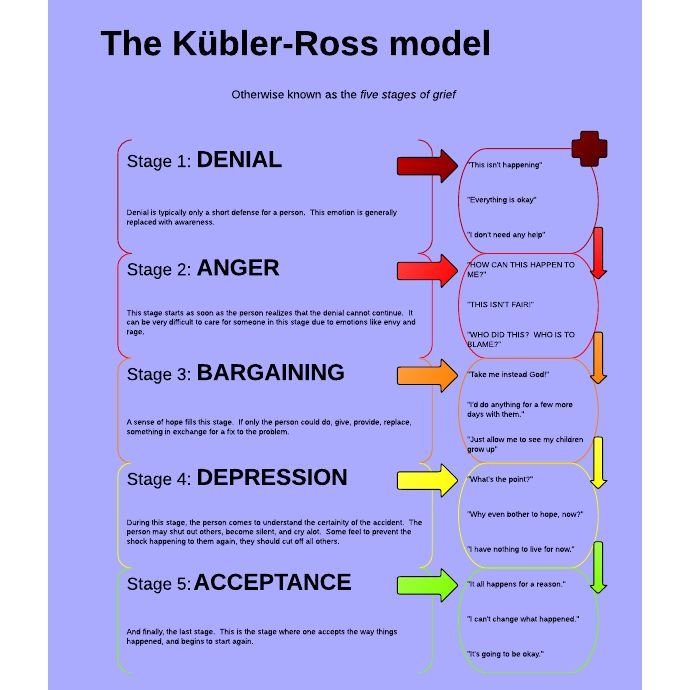

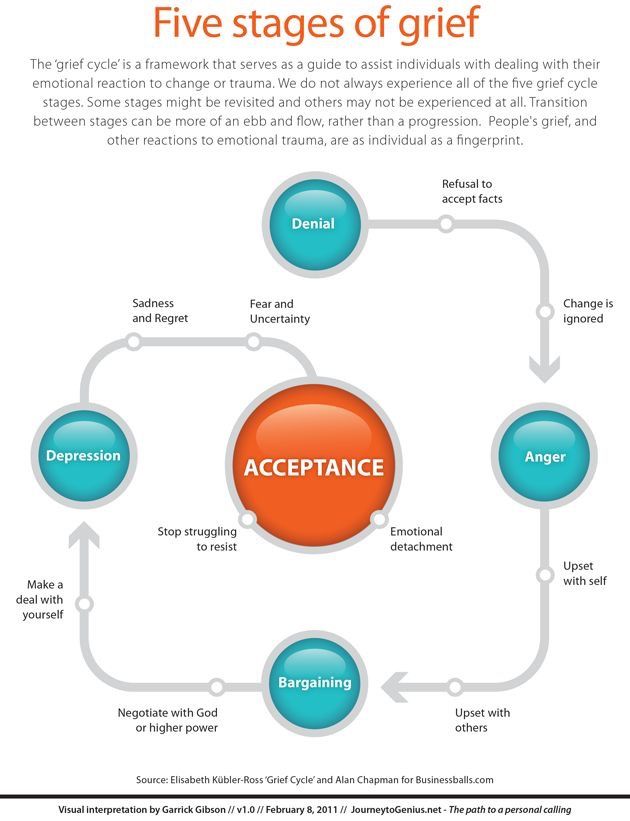

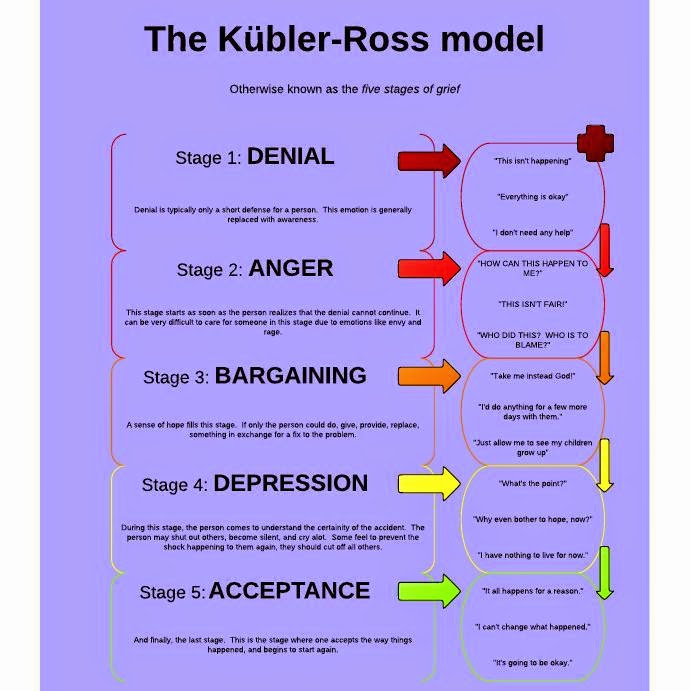

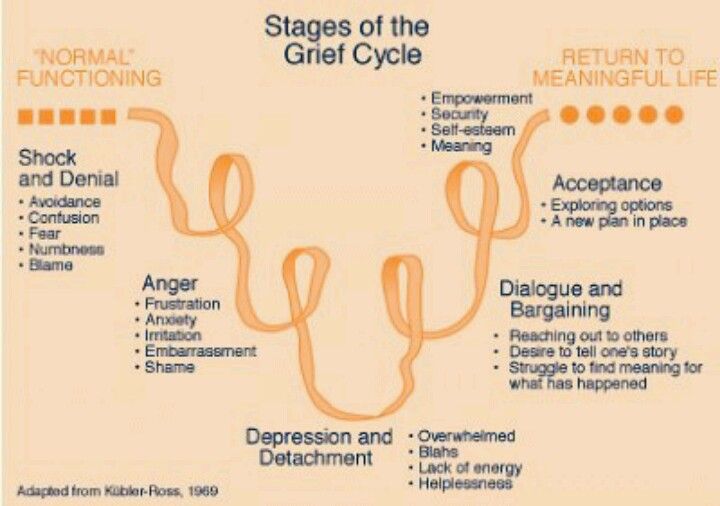

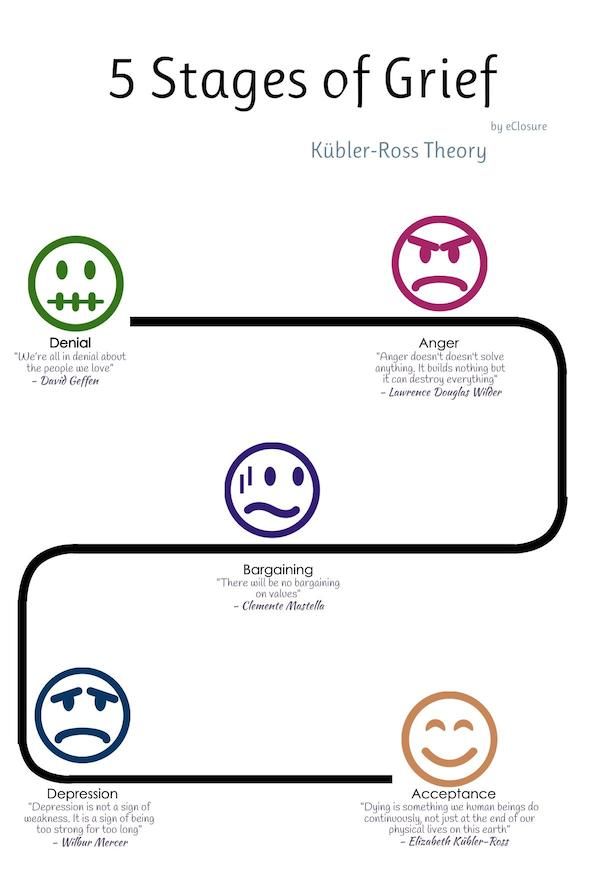

In 1969, a Swiss-American psychiatrist named Elizabeth Kübler-Ross wrote in her book “On Death and Dying” that grief could be divided into five stages. Her observations came from years of working with terminally ill individuals.

Her theory of grief became known as the Kübler-Ross model. While it was originally devised for people who were ill, these stages of grief have been adapted for other experiences with loss, too.

The five stages of grief may be the most widely known, but it’s far from the only popular stages of grief theory. Several others exist as well, including ones with seven stages and ones with just two.

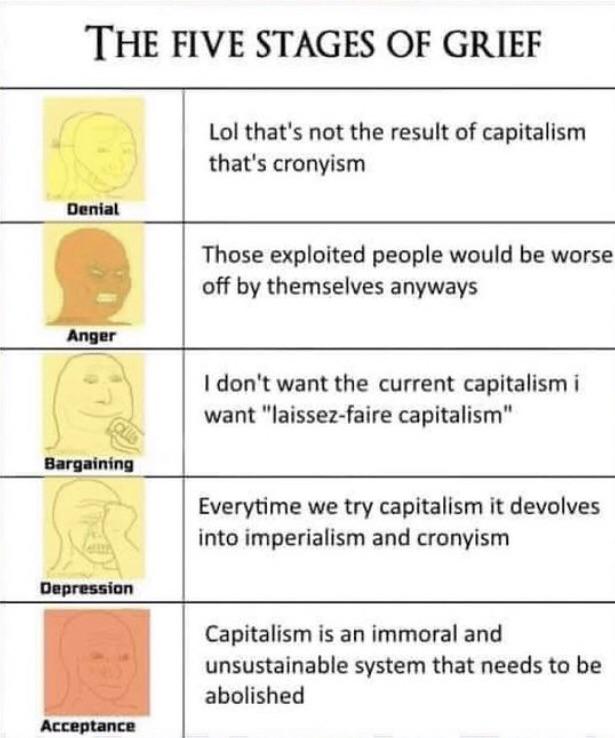

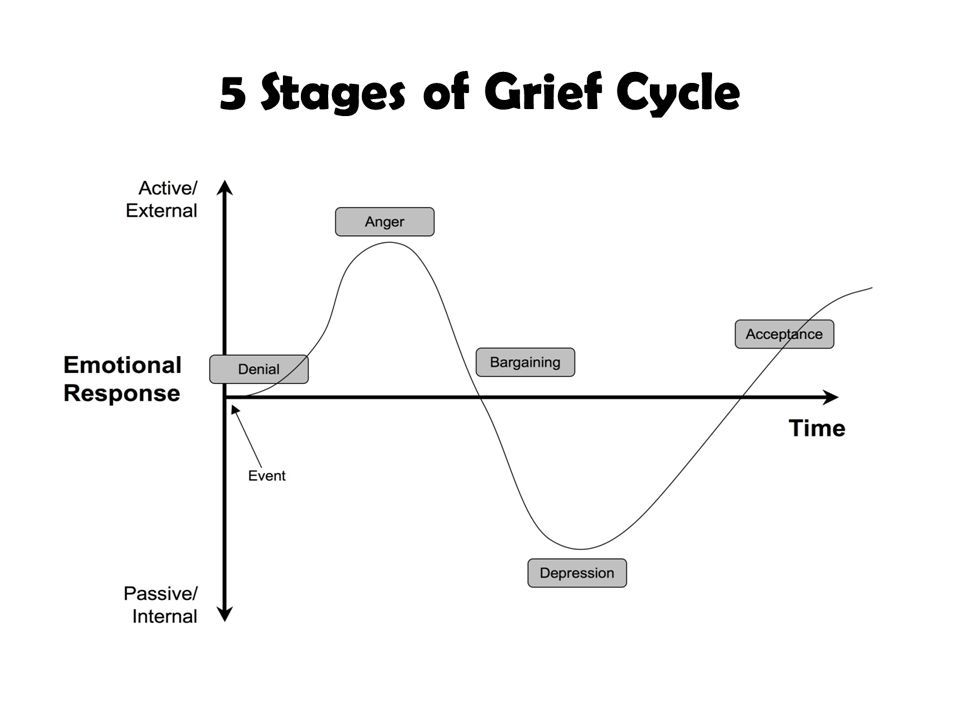

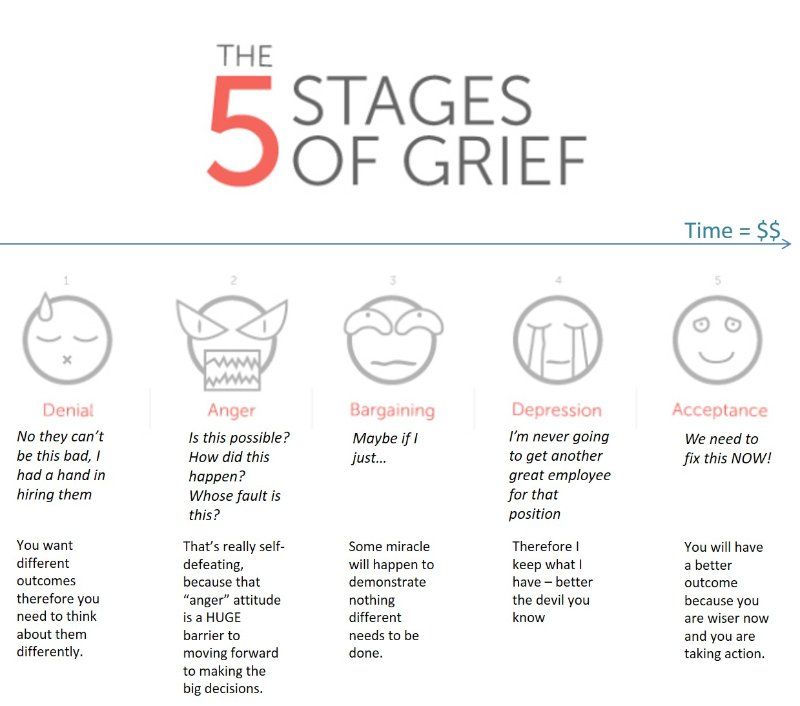

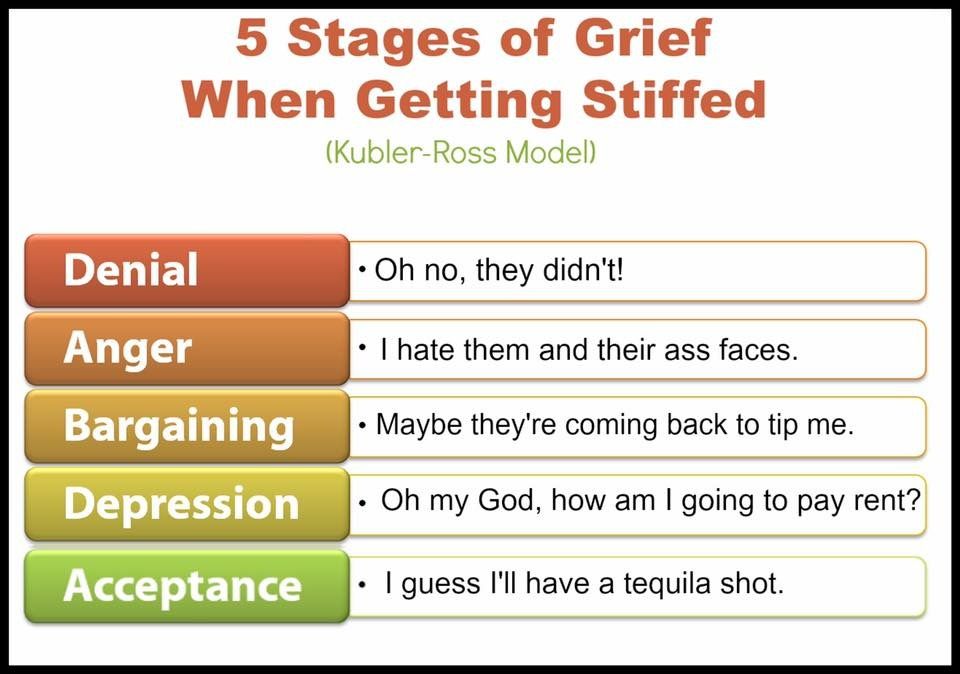

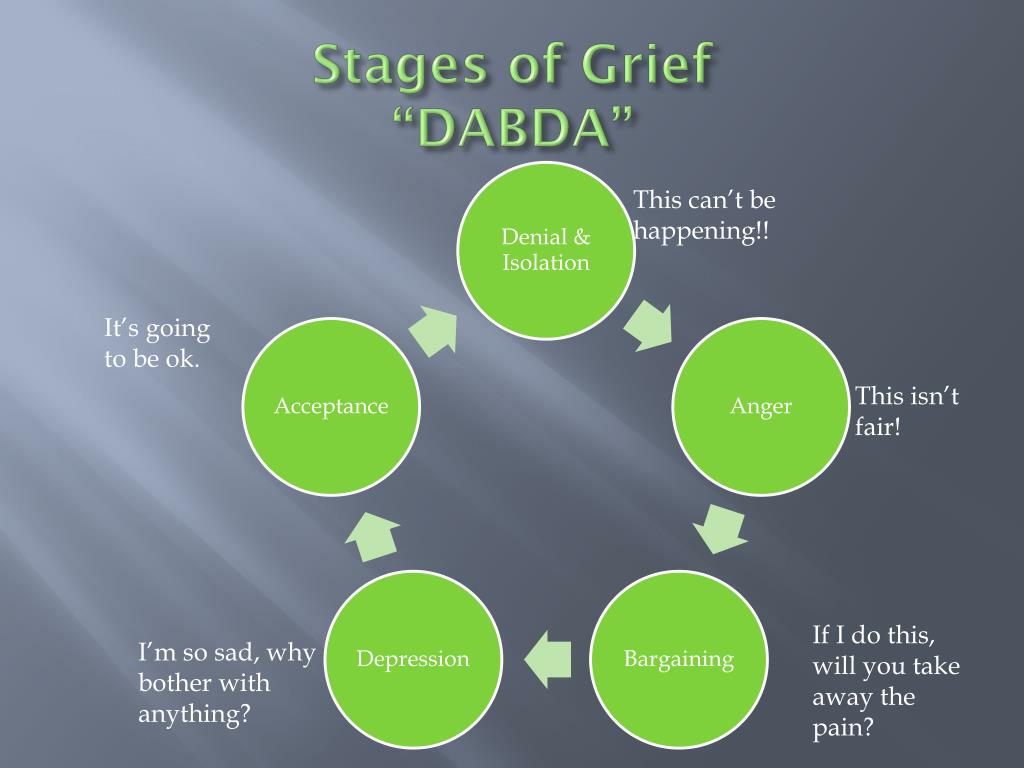

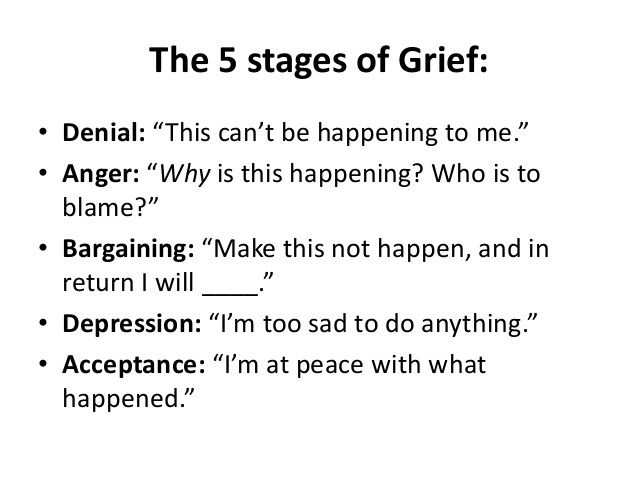

According to Kübler-Ross, the five stages of grief are:

- denial

- anger

- bargaining

- depression

- acceptance

Here’s what to know about each one.

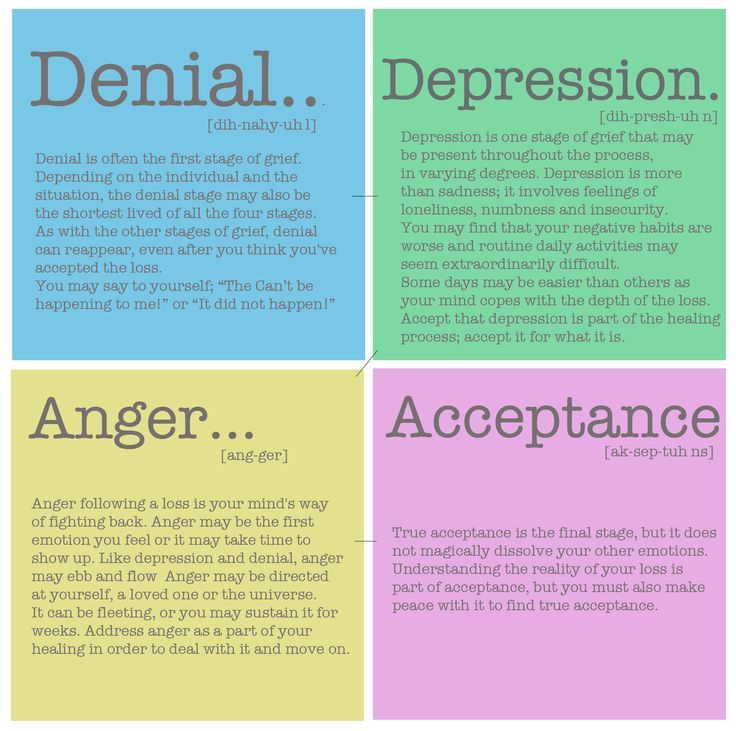

Stage 1: Denial

Grief is an overwhelming emotion. It’s not unusual to respond to the strong and often sudden feelings by pretending the loss or change isn’t happening.

Denying it gives you time to more gradually absorb the news and begin to process it. This is a common defense mechanism and helps numb you to the intensity of the situation.

As you move out of the denial stage, however, the emotions you’ve been hiding will begin to rise. You’ll be confronted with a lot of sorrow you’ve denied. That is also part of the journey of grief, but it can be difficult.

Examples of the denial stage

- Breakup or divorce: “They’re just upset. This will be over tomorrow.”

- Job loss: “They were mistaken. They’ll call tomorrow to say they need me.”

- Death of a loved one: “She’s not gone. She’ll come around the corner any second.”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “This isn’t happening to me. The results are wrong.”

Stage 2: Anger

Where denial may be considered a coping mechanism, anger is a masking effect. Anger is hiding many of the emotions and pain that you carry.

This anger may be redirected at other people, such as the person who died, your ex, or your old boss. You may even aim your anger at inanimate objects. While your rational brain knows the object of your anger isn’t to blame, your feelings in that moment are too intense to act according to that.

While your rational brain knows the object of your anger isn’t to blame, your feelings in that moment are too intense to act according to that.

Anger may mask itself in feelings like bitterness or resentment. It may not be clear-cut fury or rage.

Not everyone will experience this stage of grief. Others may linger here. As the anger subsides, however, you may begin to think more rationally about what’s happening and feel the emotions you’ve been pushing aside.

Examples of the anger stage

- Breakup or divorce: “I hate him! He’ll regret leaving me!”

- Job loss: “They’re terrible bosses. I hope they fail.”

- Death of a loved one: “If she cared for herself more, this wouldn’t have happened.”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “Where is God in this? How dare God let this happen!”

Stage 3: Bargaining

During grief, you may feel vulnerable and helpless. In those moments of intense emotions, it’s not uncommon to look for ways to regain control or to want to feel like you can affect the outcome of an event. In the bargaining stage of grief, you may find yourself creating a lot of “what if” and “if only” statements.

In the bargaining stage of grief, you may find yourself creating a lot of “what if” and “if only” statements.

It’s also not uncommon for religious individuals to try to make a deal or promise to God or a higher power in return for healing or relief from the grief and pain. Bargaining is a line of defense against the emotions of grief. It helps you postpone the sadness, confusion, or hurt.

Examples of the bargaining stage

- Breakup or divorce: “If only I had spent more time with her, she would have stayed.”

- Job loss: “If only I worked more weekends, they would have seen how valuable I am.”

- Death of a loved one: “If only I had called her that night, she wouldn’t be gone.”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “If only we had gone to the doctor sooner, we could have stopped this.”

Stage 4: Depression

Whereas anger and bargaining can feel very active, depression may feel like a quiet stage of grief.

In the early stages of loss, you may be running from the emotions, trying to stay a step ahead of them. By this point, however, you may be able to embrace and work through them in a more healthful manner. You may also choose to isolate yourself from others in order to fully cope with the loss.

That doesn’t mean, however, that depression is easy or well defined. Like the other stages of grief, depression can be difficult and messy. It can feel overwhelming. You may feel foggy, heavy, and confused.

Depression may feel like the inevitable landing point of any loss. However, if you feel stuck here or can’t seem to move past this stage of grief, you can talk with a mental health expert. A therapist can help you work through this period of coping.

Examples of the depression stage

- Breakup or divorce: “Why go on at all?”

- Job loss: “I don’t know how to go forward from here.”

- Death of a loved one: “What am I without her?”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “My whole life comes to this terrible end.

”

”

Stage 5: Acceptance

Acceptance is not necessarily a happy or uplifting stage of grief. It doesn’t mean you’ve moved past the grief or loss. It does, however, mean that you’ve accepted it and have come to understand what it means in your life now.

You may feel very different in this stage. That’s entirely expected. You’ve had a major change in your life, and that upends the way you feel about many things.

Look to acceptance as a way to see that there may be more good days than bad. There may still be bad — and that’s OK.

Examples of the acceptance stage

- Breakup or divorce: “Ultimately, this was a healthy choice for me.”

- Job loss: “I’ll be able to find a way forward from here and can start a new path.”

- Death of a loved one: “I am so fortunate to have had so many wonderful years with him, and he will always be in my memories.”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “I have the opportunity to tie things up and make sure I get to do what I want in these final weeks and months.

”

”

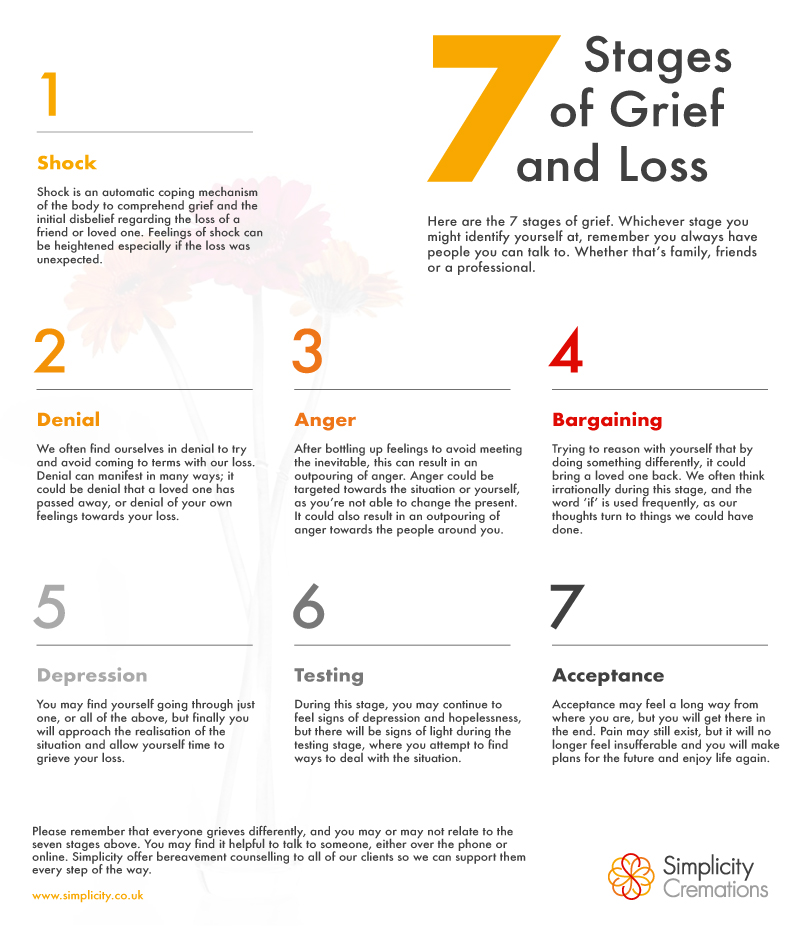

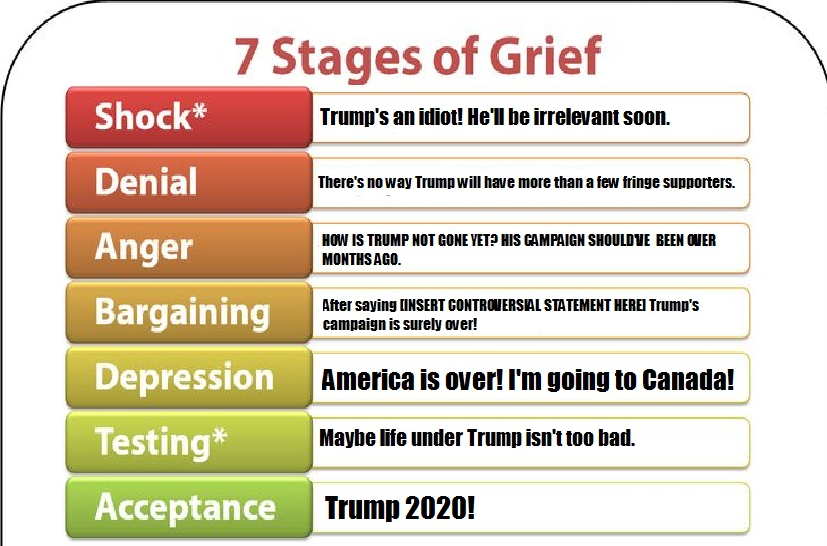

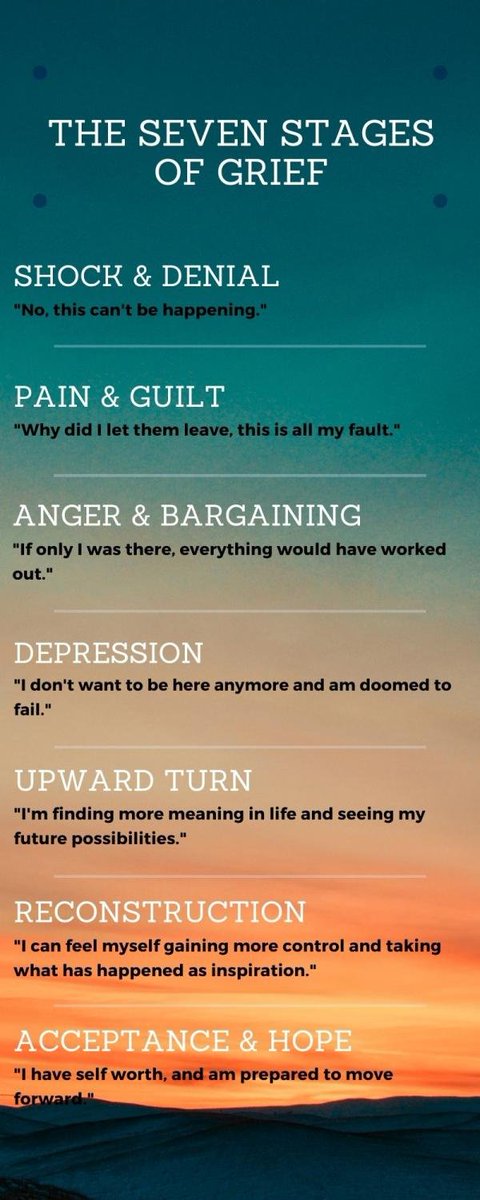

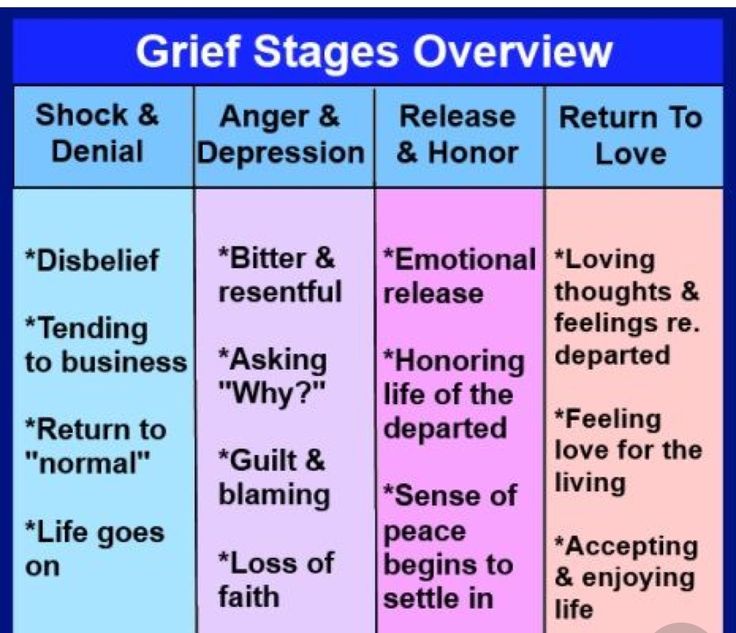

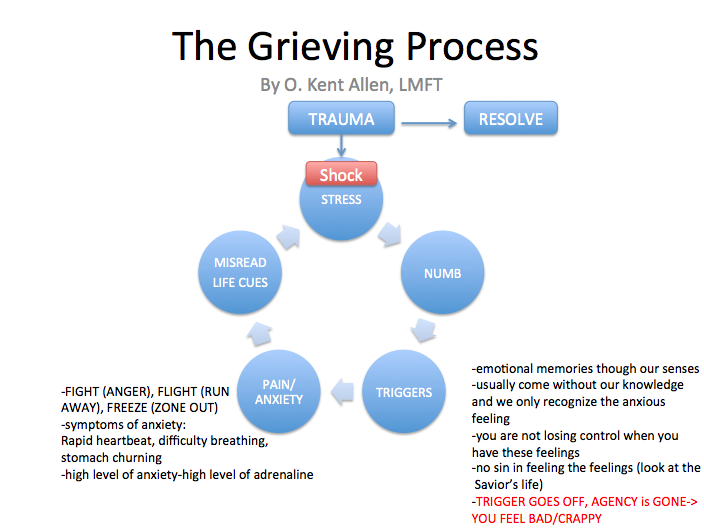

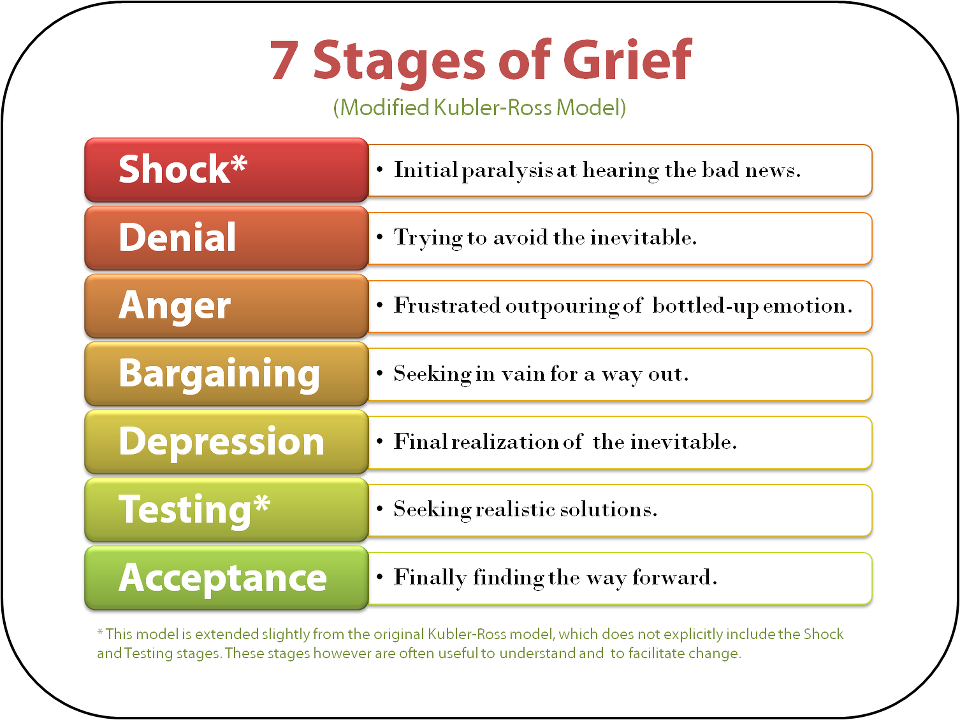

The seven stages of grief are another popular model for explaining the many complicated experiences of loss. These seven stages include:

- Shock and denial: This is a state of disbelief and numbed feelings.

- Pain and guilt: You may feel that the loss is unbearable and that you’re making other people’s lives harder because of your feelings and needs.

- Anger and bargaining: You may lash out, telling God or a higher power that you’ll do anything they ask if they’ll only grant you relief from these feelings or this situation.

- Depression: This may be a period of isolation and loneliness during which you process and reflect on the loss.

- The upward turn: At this point, the stages of grief like anger and pain have died down, and you’re left in a more calm and relaxed state.

- Reconstruction and working through: You can begin to put pieces of your life back together and move forward.

- Acceptance and hope: This is a very gradual acceptance of the new way of life and a feeling of possibility for the future.

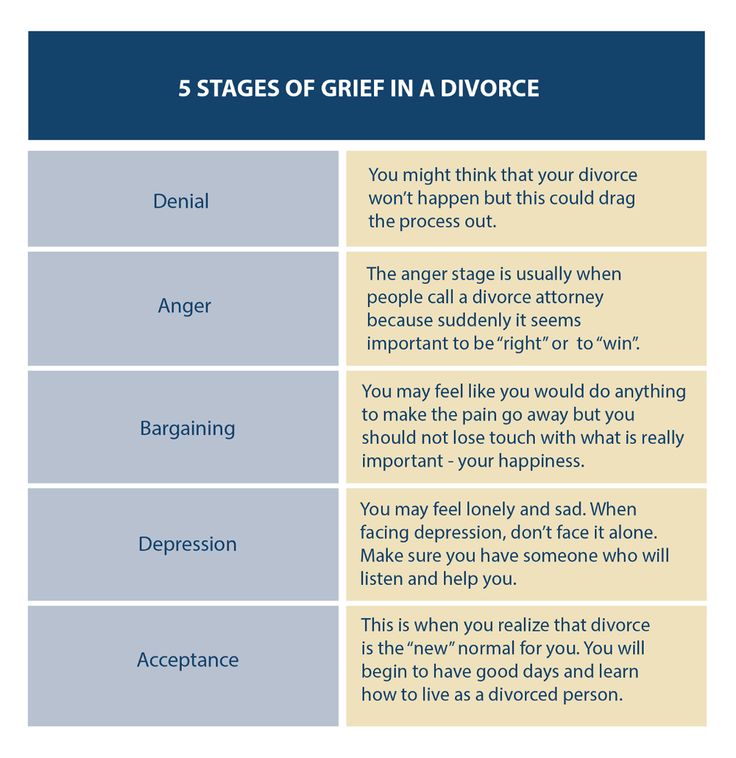

As an example, this may be the presentation of stages from a breakup or divorce:

- Shock and denial: “She absolutely wouldn’t do this to me. She’ll realize she’s wrong and be back here tomorrow.”

- Pain and guilt: “How could she do this to me? How selfish is she? How did I mess this up?”

- Anger and bargaining: “If she’ll give me another chance, I’ll be a better boyfriend. I’ll dote on her and give her everything she asks.”

- Depression: “I’ll never have another relationship. I’m doomed to fail everyone.”

- The upward turn: “The end was hard, but there could be a place in the future where I could see myself in another relationship.”

- Reconstruction and working through: “I need to evaluate that relationship and learn from my mistakes.

”

” - Acceptance and hope: “I have a lot to offer another person. I just have to meet them.”

There’s no one stage that’s universally considered to be the hardest to endure. Grief is a very individual experience. The toughest stage of grief varies from person to person and even from situation to situation.

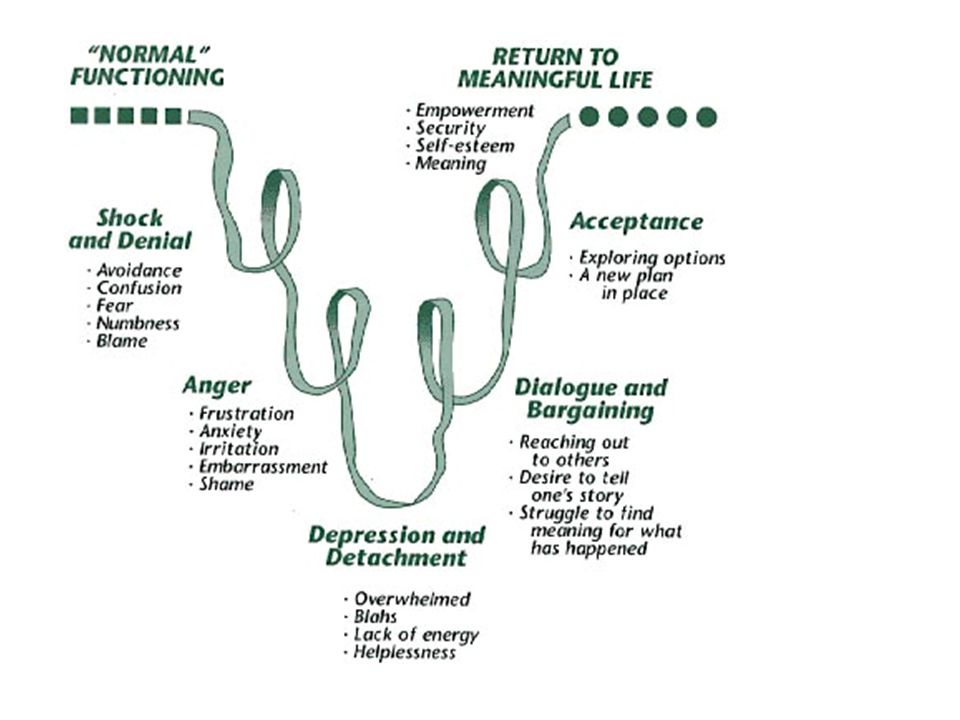

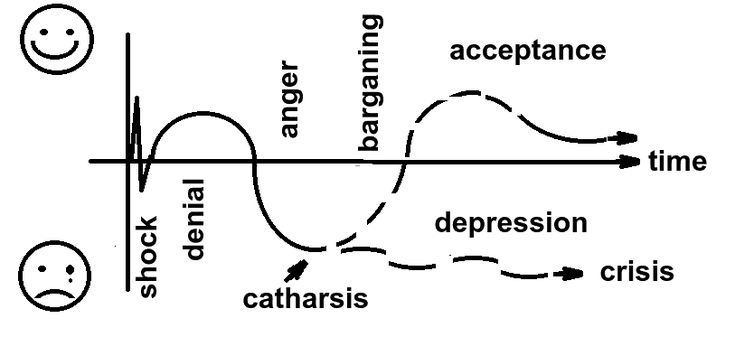

Grief is different for every person. There’s no exact time frame to adhere to. You may remain in one of the stages of grief for months but skip other stages entirely.

This is typical. It takes time to go through the grieving process.

Not everyone goes through the stages of grief in a linear way. You may have ups and downs and go from one stage to another, then circle back.

Additionally, not everyone will experience all stages of grief, and you may not go through them in order. For example, you may begin coping with loss in the bargaining stage and find yourself in anger or denial next.

Avoiding, ignoring, or denying yourself the ability to express your grief may help you dissociate from the pain of the loss you’re going through. But holding it in won’t make it disappear. And you can’t avoid grief forever.

But holding it in won’t make it disappear. And you can’t avoid grief forever.

Over time, unresolved grief can turn into physical or emotional manifestations that affect your health.

In order to heal from a loss and move on, you have to address it. If you’re having trouble processing grief, consider seeking out counseling to help you through it.

Grief is a natural emotion to experience when going through a loss.

While everyone experiences grief differently, identifying the various stages of grief can help you anticipate and comprehend some of the reactions you may experience throughout the grieving process. It can also help you understand your needs when grieving and find ways to have them met.

Understanding the grieving process can ultimately help you work toward acceptance and healing.

The key to understanding grief is realizing that no one experiences the same thing. Grief is very personal, and you may feel something different every time. You may need several weeks, or grief may be years long.

If you decide you need help coping with the feelings and changes, a mental health professional is a good resource for vetting your feelings and finding a sense of assurance in these very heavy and weighty emotions.

These resources can be useful:

- Depression Hotline

- Suicide Prevention Lifeline

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization

How to Understand Your Feelings

Grief is universal. At some point, everyone will have at least one encounter with grief. Elizabeth Kbler Ross wrote in her book “On Death and Dying” that grief could be divided into five stages. They were originally devised for people who were ill, but these stages have been adapted for coping with grief in general.

Grief is universal. At some point, everyone will have at least one encounter with grief. It may be from the death of a loved one, the loss of a job, the end of a relationship, or any other change that alters life as you know it.

Grief is also very personal. It’s not very neat or linear. It doesn’t follow any timelines or schedules. You may cry, become angry, withdraw, or feel empty. None of these things are unusual or wrong.

It’s not very neat or linear. It doesn’t follow any timelines or schedules. You may cry, become angry, withdraw, or feel empty. None of these things are unusual or wrong.

Everyone grieves differently, but there are some commonalities in the stages and the order of feelings experienced during grief.

In 1969, a Swiss-American psychiatrist named Elizabeth Kübler-Ross wrote in her book “On Death and Dying” that grief could be divided into five stages. Her observations came from years of working with terminally ill individuals.

Her theory of grief became known as the Kübler-Ross model. While it was originally devised for people who were ill, these stages of grief have been adapted for other experiences with loss, too.

The five stages of grief may be the most widely known, but it’s far from the only popular stages of grief theory. Several others exist as well, including ones with seven stages and ones with just two.

According to Kübler-Ross, the five stages of grief are:

- denial

- anger

- bargaining

- depression

- acceptance

Here’s what to know about each one.

Stage 1: Denial

Grief is an overwhelming emotion. It’s not unusual to respond to the strong and often sudden feelings by pretending the loss or change isn’t happening.

Denying it gives you time to more gradually absorb the news and begin to process it. This is a common defense mechanism and helps numb you to the intensity of the situation.

As you move out of the denial stage, however, the emotions you’ve been hiding will begin to rise. You’ll be confronted with a lot of sorrow you’ve denied. That is also part of the journey of grief, but it can be difficult.

Examples of the denial stage

- Breakup or divorce: “They’re just upset. This will be over tomorrow.”

- Job loss: “They were mistaken. They’ll call tomorrow to say they need me.”

- Death of a loved one: “She’s not gone. She’ll come around the corner any second.”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “This isn’t happening to me.

The results are wrong.”

The results are wrong.”

Stage 2: Anger

Where denial may be considered a coping mechanism, anger is a masking effect. Anger is hiding many of the emotions and pain that you carry.

This anger may be redirected at other people, such as the person who died, your ex, or your old boss. You may even aim your anger at inanimate objects. While your rational brain knows the object of your anger isn’t to blame, your feelings in that moment are too intense to act according to that.

Anger may mask itself in feelings like bitterness or resentment. It may not be clear-cut fury or rage.

Not everyone will experience this stage of grief. Others may linger here. As the anger subsides, however, you may begin to think more rationally about what’s happening and feel the emotions you’ve been pushing aside.

Examples of the anger stage

- Breakup or divorce: “I hate him! He’ll regret leaving me!”

- Job loss: “They’re terrible bosses.

I hope they fail.”

I hope they fail.” - Death of a loved one: “If she cared for herself more, this wouldn’t have happened.”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “Where is God in this? How dare God let this happen!”

Stage 3: Bargaining

During grief, you may feel vulnerable and helpless. In those moments of intense emotions, it’s not uncommon to look for ways to regain control or to want to feel like you can affect the outcome of an event. In the bargaining stage of grief, you may find yourself creating a lot of “what if” and “if only” statements.

It’s also not uncommon for religious individuals to try to make a deal or promise to God or a higher power in return for healing or relief from the grief and pain. Bargaining is a line of defense against the emotions of grief. It helps you postpone the sadness, confusion, or hurt.

Examples of the bargaining stage

- Breakup or divorce: “If only I had spent more time with her, she would have stayed.

”

” - Job loss: “If only I worked more weekends, they would have seen how valuable I am.”

- Death of a loved one: “If only I had called her that night, she wouldn’t be gone.”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “If only we had gone to the doctor sooner, we could have stopped this.”

Stage 4: Depression

Whereas anger and bargaining can feel very active, depression may feel like a quiet stage of grief.

In the early stages of loss, you may be running from the emotions, trying to stay a step ahead of them. By this point, however, you may be able to embrace and work through them in a more healthful manner. You may also choose to isolate yourself from others in order to fully cope with the loss.

That doesn’t mean, however, that depression is easy or well defined. Like the other stages of grief, depression can be difficult and messy. It can feel overwhelming. You may feel foggy, heavy, and confused.

Depression may feel like the inevitable landing point of any loss. However, if you feel stuck here or can’t seem to move past this stage of grief, you can talk with a mental health expert. A therapist can help you work through this period of coping.

However, if you feel stuck here or can’t seem to move past this stage of grief, you can talk with a mental health expert. A therapist can help you work through this period of coping.

Examples of the depression stage

- Breakup or divorce: “Why go on at all?”

- Job loss: “I don’t know how to go forward from here.”

- Death of a loved one: “What am I without her?”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “My whole life comes to this terrible end.”

Stage 5: Acceptance

Acceptance is not necessarily a happy or uplifting stage of grief. It doesn’t mean you’ve moved past the grief or loss. It does, however, mean that you’ve accepted it and have come to understand what it means in your life now.

You may feel very different in this stage. That’s entirely expected. You’ve had a major change in your life, and that upends the way you feel about many things.

Look to acceptance as a way to see that there may be more good days than bad. There may still be bad — and that’s OK.

There may still be bad — and that’s OK.

Examples of the acceptance stage

- Breakup or divorce: “Ultimately, this was a healthy choice for me.”

- Job loss: “I’ll be able to find a way forward from here and can start a new path.”

- Death of a loved one: “I am so fortunate to have had so many wonderful years with him, and he will always be in my memories.”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “I have the opportunity to tie things up and make sure I get to do what I want in these final weeks and months.”

The seven stages of grief are another popular model for explaining the many complicated experiences of loss. These seven stages include:

- Shock and denial: This is a state of disbelief and numbed feelings.

- Pain and guilt: You may feel that the loss is unbearable and that you’re making other people’s lives harder because of your feelings and needs.

- Anger and bargaining: You may lash out, telling God or a higher power that you’ll do anything they ask if they’ll only grant you relief from these feelings or this situation.

- Depression: This may be a period of isolation and loneliness during which you process and reflect on the loss.

- The upward turn: At this point, the stages of grief like anger and pain have died down, and you’re left in a more calm and relaxed state.

- Reconstruction and working through: You can begin to put pieces of your life back together and move forward.

- Acceptance and hope: This is a very gradual acceptance of the new way of life and a feeling of possibility for the future.

As an example, this may be the presentation of stages from a breakup or divorce:

- Shock and denial: “She absolutely wouldn’t do this to me. She’ll realize she’s wrong and be back here tomorrow.

”

” - Pain and guilt: “How could she do this to me? How selfish is she? How did I mess this up?”

- Anger and bargaining: “If she’ll give me another chance, I’ll be a better boyfriend. I’ll dote on her and give her everything she asks.”

- Depression: “I’ll never have another relationship. I’m doomed to fail everyone.”

- The upward turn: “The end was hard, but there could be a place in the future where I could see myself in another relationship.”

- Reconstruction and working through: “I need to evaluate that relationship and learn from my mistakes.”

- Acceptance and hope: “I have a lot to offer another person. I just have to meet them.”

There’s no one stage that’s universally considered to be the hardest to endure. Grief is a very individual experience. The toughest stage of grief varies from person to person and even from situation to situation.

Grief is different for every person. There’s no exact time frame to adhere to. You may remain in one of the stages of grief for months but skip other stages entirely.

This is typical. It takes time to go through the grieving process.

Not everyone goes through the stages of grief in a linear way. You may have ups and downs and go from one stage to another, then circle back.

Additionally, not everyone will experience all stages of grief, and you may not go through them in order. For example, you may begin coping with loss in the bargaining stage and find yourself in anger or denial next.

Avoiding, ignoring, or denying yourself the ability to express your grief may help you dissociate from the pain of the loss you’re going through. But holding it in won’t make it disappear. And you can’t avoid grief forever.

Over time, unresolved grief can turn into physical or emotional manifestations that affect your health.

In order to heal from a loss and move on, you have to address it. If you’re having trouble processing grief, consider seeking out counseling to help you through it.

If you’re having trouble processing grief, consider seeking out counseling to help you through it.

Grief is a natural emotion to experience when going through a loss.

While everyone experiences grief differently, identifying the various stages of grief can help you anticipate and comprehend some of the reactions you may experience throughout the grieving process. It can also help you understand your needs when grieving and find ways to have them met.

Understanding the grieving process can ultimately help you work toward acceptance and healing.

The key to understanding grief is realizing that no one experiences the same thing. Grief is very personal, and you may feel something different every time. You may need several weeks, or grief may be years long.

If you decide you need help coping with the feelings and changes, a mental health professional is a good resource for vetting your feelings and finding a sense of assurance in these very heavy and weighty emotions.

These resources can be useful:

- Depression Hotline

- Suicide Prevention Lifeline

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization

what happens at each of the five stages

All people face losses: lose their jobs, bury loved ones, experience a breakup of relationships. Today we will talk about what grief is, what stages it has and how knowing about them will help to cope with a black streak in life.

Website editor

Tags:

Psychology

Psychology of Personality

Death of a loved one

loss

Getty images

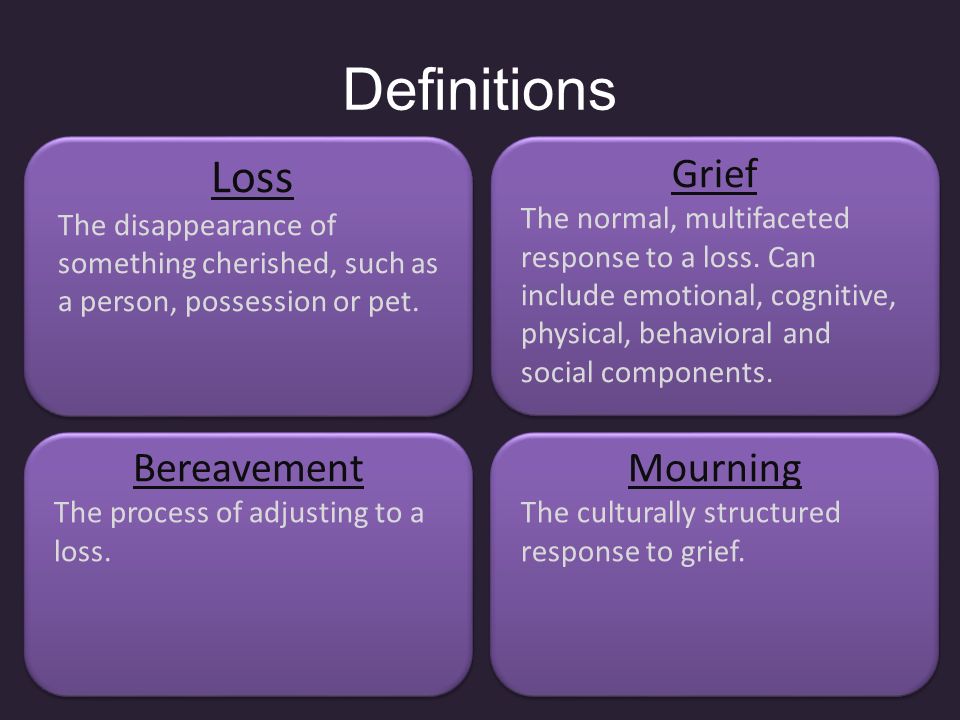

Grief is a very personal experience. Each of us goes through it in our own way: some close in on themselves, others cry, others get angry. There is no right or wrong way to deal with loss—everyone behaves differently. But there are some common features of mourning, known as the stages of mourning.

But there are some common features of mourning, known as the stages of mourning.

How did the theory of five stages of grief come about

In 1969, Swiss-born American psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross published On Death and Dying, in which she identified five stages of grief. The book was based on the observations of Elizabeth, who worked with terminally ill people for many years.

The five stages of mourning described by the scientist were later called the Kübler-Ross model. Initially, it was about the experiences of terminally ill patients, but in the later stages of grief, they were adapted to emotions experienced due to other losses. nine0003

Five stages of grief: from denial to acceptance

In total, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross identified five stages of grief:

- denial;

- anger;

- bargain;

- depression;

- acceptance.

Not every person goes through all five stages, and they do not necessarily follow each other in that order. You can stay on one of them for months and skip the others. It is possible that everything will start with bargaining and only then the person will plunge into anger and denial. Everyone will go their own way, and it is worth knowing what steps you will probably have to take along it. nine0003

First stage of grief: denial

Grief is overwhelming. It is natural to respond to strong and often sudden feelings by pretending nothing happened. Denial gives us time to gradually digest the news and incorporate it into our lives. This is a common defense mechanism to deal with stress.

However, as a person emerges from the stage of denial, the emotions from which he was hiding begin to grow. At such moments, the mourner is confronted with intense sadness, which previously went unnoticed. This is part of the journey and it can be very difficult. nine0003

This is part of the journey and it can be very difficult. nine0003

Second stage of grief: anger

If denial is a survival mechanism, then anger is a way to mask feelings. It hides other feelings and pain that a person faces. Rage can be directed at other people - from relatives who come to the hospital to a former boss. Sometimes even inanimate objects can become the object of anger.

Reason at such moments prompts: the one on whom you are breaking down is not to blame for what happened. But the emotions are too strong for the rational side of the personality to take over. Sometimes anger is “disguised” and does not look like a pronounced rage, but like bitterness and indignation. Not all people go through the anger stage, but there are those who linger on it for a long time. nine0003

Third stage of grief: bargaining

Grief makes people vulnerable and helpless. At such moments, they often look for ways to regain control over life, they want to feel that they can influence the outcome of events. It's time for internal dialogues with endless questions: "What if? .."

At such moments, they often look for ways to regain control over life, they want to feel that they can influence the outcome of events. It's time for internal dialogues with endless questions: "What if? .."

Those who are religious often try to make a deal with God or higher powers, giving them various promises in exchange for healing or pain relief. In essence, a deal is an attempt to delay the inevitable, to hide from confusion or sadness. People expect that they will be rewarded for "exemplary behavior" and take oaths that they are not going to fulfill. nine0003

Fourth stage of grief: depression

Anger and bargaining can be very active, depression is experienced as a quiet stage of grief. At first, a person tries to run away from emotions, but by this stage he is already able to accept and process them. At such times, people may choose to isolate themselves to cope with the loss.

However, this does not mean that depression is mild or well defined. Like other stages of mourning, it can be complex and confusing. It may seem to you that everything around you is in a fog, and the only thing you feel is confusion and sadness. nine0003

Like other stages of mourning, it can be complex and confusing. It may seem to you that everything around you is in a fog, and the only thing you feel is confusion and sadness. nine0003

Depression can be felt as the inevitable "landing point" of any loss: deprivation becomes clear and inevitable. But if you understand that you are bogged down in depression and do not move on to acceptance, then you should talk to a psychotherapist: he will help you go through this stage and not get stuck in it for a long time.

Fifth Stage of Grief: Acceptance

Acceptance is not necessarily a happy or uplifting stage of mourning. It does not mean that a person experienced a loss. This is an understanding of how what happened affects his life. nine0003

At this stage, you may feel very different. This is normal, because there have been changes that affect all relations with the world. Acceptance should be looked at as a way of realizing that there are more good days than bad ones, but there are also black streaks in life.

7 stages of grief

The Kübler-Ross model of five stages of grief is the best known, but it is far from the only one. Another one that helps explain the experience of loss involves seven stages. nine0003

- Shock and denial. This is a time of distrust and numb feelings.

- Pain and guilt. The loss seems unbearable to a person, he believes that he complicates the life of others with his feelings and needs.

- Anger and bargaining. At this moment, the mourner promises God and the higher powers anything, if they grant him relief.

- Depression. At this stage, a person becomes isolated, choosing loneliness in order to comprehend and accept the loss. nine0036

- Turn up. Anger and pain subside, and the one faced with loss becomes calmer and more relaxed.

- Reconstruction and development.

At this stage, the pieces of life come together again and the forward movement begins.

At this stage, the pieces of life come together again and the forward movement begins. - Acceptance and hope. At this stage, there is an acceptance of a new way of life, there is an understanding that new opportunities await in the future.

7 stages of grief example

Here's what the seven stages of grief would look like in the case of a divorce:

- Shock and denial: “He can't do this to me. He will realize that he made a mistake and will return.”

- Pain and guilt: “How could he do this? Is he that selfish? How could I ruin everything?"

- Anger and bargaining: “If he gives me another chance, I will be an ideal wife. I love him and I will give him whatever he wants!”

- Depression: “I will never have a relationship again. I'm doomed to always let everyone down." nine0036

- Turn up: "It was hard, but I might meet someone else in the future.

"

" - Reconstruction and working through: "I need to analyze these relationships in order to learn from my mistakes."

- Acceptance and hope: “I can give a lot to another person. Sooner or later I will meet him.”

Whatever the model of grief, there is one important point: everyone experiences it in their own way. Even you, faced with different losses, each time you go through a new, still unfamiliar path. Sometimes it takes several weeks, but it also happens that mourning drags on for years. To cope with feelings and regain self-confidence, it is worth contacting a psychotherapist who will help you cope with pain and emotions. nine0003

Have you experienced loss?

Four tasks of grief | Journal of Practical Psychology and Psychoanalysis

Year of publication and journal number:

2001, №1-2

Grief is a reaction to the loss of a significant object, part of an identity, or an expected future. It is well known that the reaction to the loss of a significant object is a specific mental process that develops according to its own laws. The essence of this process is universal, unchanging and does not depend on what exactly the subject has lost. The experience of grief always proceeds in the same way. Only its duration and intensity differ, which depend on the significance of the lost object and on the personality traits of the grieving person. Many attempts have been made to describe the process of grief in a formal way in order to facilitate practical work with it. nine0003

The essence of this process is universal, unchanging and does not depend on what exactly the subject has lost. The experience of grief always proceeds in the same way. Only its duration and intensity differ, which depend on the significance of the lost object and on the personality traits of the grieving person. Many attempts have been made to describe the process of grief in a formal way in order to facilitate practical work with it. nine0003

Initially, they tried to describe grief as a series of successive stages. The number of stages in different authors ranged from four to twelve. The therapist was supposed to help the client move from stage to stage. However, as it turned out, the stages do not have clear boundaries and sometimes an already lived stage gives relapses at later stages. In addition, sometimes certain stages were missing or were so poorly expressed that they could not be traced and worked out accordingly. In addition, the manifestations of grief at all stages are very individual, therefore, it often remained unclear where the efforts of the psychotherapist should be directed. All this made the practical application of these descriptions of the grief process difficult and inconvenient. nine0003

All this made the practical application of these descriptions of the grief process difficult and inconvenient. nine0003

J. William Vorden's new approach to dealing with a grieving client has recently become widespread. Worden's concept, while not the only one, remains the most popular among people working with loss today. It is very convenient for diagnosing and working with actual grief, as well as if you have to deal with grief that was not experienced many years ago and was revealed during therapy started at a completely different request.

Vorden proposed a variant of describing the grief reaction not in terms of stages or phases, but in terms of four tasks that must be performed by the mourner during the normal course of grief. These tasks are essentially similar to those tasks that a child solves as he grows up and separates from his mother. Vorden considers this approach to be the most convenient for clinicians and the closest to Freud's theory of grief at work. nine0003

Vorden believes that although the forms of grief and their manifestations are very individual, the immutability of the content of the process allows us to highlight those universal steps that the mourner must take in order to return to normal life, and to the implementation of which the attention of the therapist should be directed. The tasks of grief are unchanged, because they are determined by the process itself, and the forms and methods of their solution are individual and depend on the personal and social characteristics of the grieving person. Four tasks of grief are solved by the subject sequentially. This is convenient for diagnosis, since it is much easier to understand which psychological problem has been solved and which has not, than to determine a poorly expressed stage of grief. In addition, since it is clear that there is a solution to this problem, it is clear where the psychotherapeutic process should be directed. nine0003

The tasks of grief are unchanged, because they are determined by the process itself, and the forms and methods of their solution are individual and depend on the personal and social characteristics of the grieving person. Four tasks of grief are solved by the subject sequentially. This is convenient for diagnosis, since it is much easier to understand which psychological problem has been solved and which has not, than to determine a poorly expressed stage of grief. In addition, since it is clear that there is a solution to this problem, it is clear where the psychotherapeutic process should be directed. nine0003

If the tasks of grief are not solved by the grieving person, the grief will not develop further and tend to end, therefore, problems may arise in connection with this even after many years. The grief reaction can be blocked on any of the tasks, and behind this there can be a different level of pathology. Stopping the reaction at the stage of solving each of the problems of grief has certain symptoms.

In this article, I would like to make a summary of the four tasks that the grieving person must solve, based mainly on Warden's seminal book Counseling and Grief Therapy, using the example of the reaction to the death of a loved one. This example most fully illustrates the reaction of loss, and it is important to remember that any reaction of loss will always develop in a similar way in content, only the duration and intensity differ. The forms of manifestation of the process are purely individual. nine0003

So, obviously, it is impossible to begin to experience loss until the very fact of loss is recognized. Thus, the first task is recognition of the loss of .

When someone dies, even in the event of an expected death, it is normal to feel as if nothing has happened. Therefore, first of all, you need to recognize the fact of loss, to realize that a loved one has died, he left and will never return. During this period, just as a lost child is looking for a mother, a person mechanically tries to get in touch with the deceased - mechanically dials his phone number, "sees" among passers-by on the street, buys food for him, etc. This "searching" behavior described by Bowlby and Parks is aimed at reconnecting. Normally, this behavior should be replaced by behavior aimed at refusing to communicate with the deceased loved one. A person who performs the actions described above normally catches himself and says to himself: "What am I doing, because he (she) is dead." Quite often there is the opposite behavior - denial (denial) of what happened. If a person does not overcome denial, then the work of grief is blocked in the earliest stages. Denial can be used at different levels and take many forms, but generally involves either denying the fact of the loss, or its significance, or irreversibility. nine0003

This "searching" behavior described by Bowlby and Parks is aimed at reconnecting. Normally, this behavior should be replaced by behavior aimed at refusing to communicate with the deceased loved one. A person who performs the actions described above normally catches himself and says to himself: "What am I doing, because he (she) is dead." Quite often there is the opposite behavior - denial (denial) of what happened. If a person does not overcome denial, then the work of grief is blocked in the earliest stages. Denial can be used at different levels and take many forms, but generally involves either denying the fact of the loss, or its significance, or irreversibility. nine0003

Loss denial can range from mild to severe psychotic, where the person spends several days in the apartment with the deceased before noticing that the person has died. Gardiner and Pritcher described six such cases as extreme forms of the psychotic reaction to death.

The most common and less pathological form of manifestation of denial was called mummification by the English author Gorer. In such cases, a person keeps everything as it was with the deceased, in order to be ready for his return all the time. For example, parents keep the rooms of dead children. This is normal if it does not last long, thus creating a kind of "buffer" that should soften the most difficult stage of experiencing and adjusting to the loss. But if such behavior drags on for years, the experience of grief stops and the person refuses to recognize the changes that have occurred in his life, "keeping everything as it was" and not moving from his place in his mourning, this is a manifestation of denial. An even milder form of denial is when a person "sees" the deceased in someone else - for example, a widowed woman sees her husband in her grandson. "Poured grandfather." Such a mechanism can alleviate the pain of loss, but rarely completely satisfies - the grandson is still not a grandfather, and if "he continues to live in children", then you still cannot enter into the same relationship with them (children) as with the deceased.

In such cases, a person keeps everything as it was with the deceased, in order to be ready for his return all the time. For example, parents keep the rooms of dead children. This is normal if it does not last long, thus creating a kind of "buffer" that should soften the most difficult stage of experiencing and adjusting to the loss. But if such behavior drags on for years, the experience of grief stops and the person refuses to recognize the changes that have occurred in his life, "keeping everything as it was" and not moving from his place in his mourning, this is a manifestation of denial. An even milder form of denial is when a person "sees" the deceased in someone else - for example, a widowed woman sees her husband in her grandson. "Poured grandfather." Such a mechanism can alleviate the pain of loss, but rarely completely satisfies - the grandson is still not a grandfather, and if "he continues to live in children", then you still cannot enter into the same relationship with them (children) as with the deceased. And in the end, this situation ends with the acceptance of the reality of loss. nine0003

And in the end, this situation ends with the acceptance of the reality of loss. nine0003

Another way people avoid the reality of loss is to deny the significance of the loss. In this case, they say things like "we weren't close", "he was a bad father" or "I don't miss him". Sometimes people hastily remove all the personal belongings of the deceased, all that can remind of him is the opposite behavior of mummification. In this way, bereaved ones keep themselves from coming face to face with the reality of loss. Those who exhibit this behavior are at risk of developing pathological grief reactions. nine0003

Another manifestation of denial is "selective forgetting". In this case, the person forgets something concerning the deceased. For example, Gorer's client, a 35-year-old man who lost his father at the age of fifteen, could not remember his appearance, not even his height or hair color. After successful grief therapy, he remembered the appearance of his father, lived through all the feelings associated with the loss and was able to return to normal life.

The third way to avoid awareness of the loss is to deny the irreversibility of the loss. Vorden gave an example from his practice - a woman who lost her mother and twelve-year-old daughter in a fire, repeated aloud for two years, like a spell: "I don't want you to die." She spoke as if her loved ones had not yet died and she could save their lives with this spell. Another example is when, after the death of a child, parents console each other - "we will have other children and everything will be fine." It is understood that we will give birth to a dead child again and everything will be as it was. Another variant of this behavior is the fascination with spiritualism. The irrational hope of reuniting with the deceased is normal in the first weeks after the loss, when behavior is directed to reconnect, but if this hope becomes stable, this is not normal. For religious people, this behavior looks a little different, because they have a different picture of the world. Then the critical attitude of the grieving to what is happening will be the norm, he understands that in this life he will never be with the deceased and will reunite with him only after living his life in this world the way a good Christian or a respectable Muslim should live it. This expectation of reunion after death does not need to be destroyed, since it is part of the normal picture of the world of deeply religious people. nine0003

This expectation of reunion after death does not need to be destroyed, since it is part of the normal picture of the world of deeply religious people. nine0003

The second task of grief, according to Vorden, is to survive the pain of losing . This means that you need to go through all the complex feelings that accompany the loss.

If a grieving person cannot feel and live the pain of loss, which is absolutely always there, it must be identified and worked through with the help of a therapist, otherwise the pain will manifest itself in other forms, for example, through psychosomatics or behavioral disorders.

Parkes wrote: "If the grieving person must experience the pain of loss in order for the work of overcoming that loss to be done, then anything that avoids or suppresses that pain will prolong the period of mourning." Pain reactions are individual and not everyone experiences pain of the same intensity. nine0003

A grieving person often loses contact not only with external reality, but also with inner experiences. “I don’t seem to feel anything, it’s even strange,” “I thought it happens differently, some strong feelings, but here - nothing.” The pain of loss is not always felt, sometimes loss is experienced as apathy, lack of feelings, but it must be worked through.

“I don’t seem to feel anything, it’s even strange,” “I thought it happens differently, some strong feelings, but here - nothing.” The pain of loss is not always felt, sometimes loss is experienced as apathy, lack of feelings, but it must be worked through.

This task is made difficult by others. Often people around are uncomfortable with the intense pain and feelings of the grieving, they do not know what to do with it and consciously or unconsciously tell him: "You should not grieve." This unspoken wish of others often interacts with the bereaved person's own psychological defenses, leading to a denial of the necessity or inevitability of the grief process. Sometimes it is even expressed in the following words: "I must not cry for him" or "I must not grieve", "Now is not the time to grieve." Then the manifestations of grief are blocked, emotions do not react and do not come to their logical conclusion. nine0003

The second task is avoided in different ways. This may be denial (negation) of the presence of pain or other painful feelings. In other cases, it may be the avoidance of painful thoughts. For example, only positive, "pleasant", in Vorden's words, thoughts about the deceased, up to complete idealization, can be allowed. It also helps to avoid unpleasant experiences associated with death. It is possible to avoid all sorts of memories of the deceased. Some people start using alcohol or drugs for this purpose. Others use the "geographical way" - continuous travel or continuous work with great tension, which does not allow you to think about anything other than everyday affairs. I know of a case where a man went to work on the day his mother died, even though he was a lecturer. Such public work does not allow you to relax for a second. He did the same on the day of the funeral, and specifically asked to change the schedule. It was a very purposeful behavior to avoid the experience of the mother's death. Parks described cases where the reaction to death was euphoria. Usually it is associated with a refusal to believe that death has occurred and is accompanied by a constant feeling of the presence of the deceased.

In other cases, it may be the avoidance of painful thoughts. For example, only positive, "pleasant", in Vorden's words, thoughts about the deceased, up to complete idealization, can be allowed. It also helps to avoid unpleasant experiences associated with death. It is possible to avoid all sorts of memories of the deceased. Some people start using alcohol or drugs for this purpose. Others use the "geographical way" - continuous travel or continuous work with great tension, which does not allow you to think about anything other than everyday affairs. I know of a case where a man went to work on the day his mother died, even though he was a lecturer. Such public work does not allow you to relax for a second. He did the same on the day of the funeral, and specifically asked to change the schedule. It was a very purposeful behavior to avoid the experience of the mother's death. Parks described cases where the reaction to death was euphoria. Usually it is associated with a refusal to believe that death has occurred and is accompanied by a constant feeling of the presence of the deceased. These conditions are usually unstable. Bowlby wrote: "Sooner or later, everyone who avoids the feelings associated with grief breaks down, most often falling into depression." One of the goals of therapeutic work with loss is to help people solve this difficult task of mourning, to open up and live the pain without collapsing in front of it. It must be lived so as not to be carried through life. If this is not done, therapy may be needed later and it will be more painful and difficult to return to these experiences than to immediately experience them. The delayed experience of pain is also more difficult because if the pain of loss is experienced after a considerable time, the person can no longer receive the sympathy and support from others who usually appear immediately after the loss and who help to cope with grief. nine0003

These conditions are usually unstable. Bowlby wrote: "Sooner or later, everyone who avoids the feelings associated with grief breaks down, most often falling into depression." One of the goals of therapeutic work with loss is to help people solve this difficult task of mourning, to open up and live the pain without collapsing in front of it. It must be lived so as not to be carried through life. If this is not done, therapy may be needed later and it will be more painful and difficult to return to these experiences than to immediately experience them. The delayed experience of pain is also more difficult because if the pain of loss is experienced after a considerable time, the person can no longer receive the sympathy and support from others who usually appear immediately after the loss and who help to cope with grief. nine0003

This protective behavior has its own reasons, and they need to be dealt with separately before starting to work with feelings. It is necessary to find out the reasons why a person avoids experiences associated with the pain of loss, and first work through them. For example, work with the fear of difficult feelings. In other cases, it is necessary to change the stereotype of behavior associated with the earlier ban on the open expression of feelings, or you need to understand how to deal with the resistance of others who are uncomfortable being close to a person in acute grief. nine0003

For example, work with the fear of difficult feelings. In other cases, it is necessary to change the stereotype of behavior associated with the earlier ban on the open expression of feelings, or you need to understand how to deal with the resistance of others who are uncomfortable being close to a person in acute grief. nine0003

The next task that the mourner must cope with is adjusting the environment where the absence of the deceased is felt. When a person loses a loved one, he loses not only the object to which feelings are addressed and from which feelings are received, he loses a certain way of life. The deceased loved one participated in everyday life, demanded the performance of some actions or certain behavior, the performance of any roles, took on part of the duties. And it goes with him. This void must be filled and life organized in a new way. nine0003

Organizing a new environment means different things to different people, depending on the relationship they had with the deceased and the roles the deceased played in their lives. Parkes wrote: “In all mourning, it is not always clear what constitutes a loss. The loss of a husband, for example, may mean, for example, - or not mean - the loss of a sexual partner, companion, accountant, gardener, jester, etc., in depending on the roles that the husband usually performed. The mourner may or may not be aware of the roles that the deceased played in his life. Even if the client is not aware of these roles, the therapist needs to map out for himself what the client has lost and how it can be made up for. Sometimes it's worth talking to the client. Often the client spontaneously starts doing this himself during the session. My client after the death of her mother, feeling very helpless and unprotected, began to reason - what have I lost? An affectionate word, a look, a voice, a touch - yes, this is irreplaceable. But a lot of what my mother did for me and what gave me a sense of security, I can do for myself. I can learn to sew - my mother sewed it, - I can learn to cook and create comfortable conditions for myself when I come home from work - my mother used to meet her with dinner - for example, dinner can be put in the microwave in the morning and all that remains is to press a button .

Parkes wrote: “In all mourning, it is not always clear what constitutes a loss. The loss of a husband, for example, may mean, for example, - or not mean - the loss of a sexual partner, companion, accountant, gardener, jester, etc., in depending on the roles that the husband usually performed. The mourner may or may not be aware of the roles that the deceased played in his life. Even if the client is not aware of these roles, the therapist needs to map out for himself what the client has lost and how it can be made up for. Sometimes it's worth talking to the client. Often the client spontaneously starts doing this himself during the session. My client after the death of her mother, feeling very helpless and unprotected, began to reason - what have I lost? An affectionate word, a look, a voice, a touch - yes, this is irreplaceable. But a lot of what my mother did for me and what gave me a sense of security, I can do for myself. I can learn to sew - my mother sewed it, - I can learn to cook and create comfortable conditions for myself when I come home from work - my mother used to meet her with dinner - for example, dinner can be put in the microwave in the morning and all that remains is to press a button . It helped so much in our work that I started using it as an exercise with other clients. The mourner must acquire new skills. The family can provide support in acquiring them. Vorden cited his client, a young widow, as an example. Her late husband was the type of person who tends to take full responsibility for what is happening and solve all problems on his own. His wife lived with him "like behind a stone wall." Her husband did everything for her. After his death, the widow withdrew and, not knowing how to interact with the outside world and solve problems that arise outside the family world, she practically abandoned social activity. But when one of her children started misbehaving at school, it required her to meet with school staff and social workers. Willy-nilly, she had to overcome her inner resistance and leave the house for the outside world. She learned how to interact with the school staff, solved the problem that arose, and this gave her the necessary experience and the feeling that difficulties of this kind can be overcome.

It helped so much in our work that I started using it as an exercise with other clients. The mourner must acquire new skills. The family can provide support in acquiring them. Vorden cited his client, a young widow, as an example. Her late husband was the type of person who tends to take full responsibility for what is happening and solve all problems on his own. His wife lived with him "like behind a stone wall." Her husband did everything for her. After his death, the widow withdrew and, not knowing how to interact with the outside world and solve problems that arise outside the family world, she practically abandoned social activity. But when one of her children started misbehaving at school, it required her to meet with school staff and social workers. Willy-nilly, she had to overcome her inner resistance and leave the house for the outside world. She learned how to interact with the school staff, solved the problem that arose, and this gave her the necessary experience and the feeling that difficulties of this kind can be overcome. Often, the grieving person develops new ways to overcome the difficulties that have arisen and new opportunities open up before him, so that the fact of loss is reformulated into something that also has a positive meaning. This is a frequent option for successful completion of the third task. For example, a client of mine who lost her mother, with whom she was in a very close symbiotic relationship, once said: "My mother died, and now I began to live. She did not allow me to become an adult, and now I can build my life as I want. I like it." nine0003

Often, the grieving person develops new ways to overcome the difficulties that have arisen and new opportunities open up before him, so that the fact of loss is reformulated into something that also has a positive meaning. This is a frequent option for successful completion of the third task. For example, a client of mine who lost her mother, with whom she was in a very close symbiotic relationship, once said: "My mother died, and now I began to live. She did not allow me to become an adult, and now I can build my life as I want. I like it." nine0003

In addition to the loss of the object, some people simultaneously experience the feeling of losing themselves, their own Self. Recent studies have shown that women who define their identity through interactions with loved ones or caring for others, having lost the object of care, experience a feeling of losing themselves. Working with such a client should be much more than just developing new skills and the ability to cope with new roles.

Grief often leads a person to a strong regression and the perception of himself as helpless, unable to cope with difficulties and inept, like a child. The attempt to play the role of the deceased may fail, and this leads to even deeper regression and damage to self-esteem. Then you have to work with the client's negative self-image. This takes time, but gradually, relying on a becoming more positive self-image, the client learns to successfully operate in those areas of life that he previously avoided. nine0003

Maintaining a passive, helpless position helps to avoid loneliness - friends and loved ones should help and participate in the life of a bereaved person. At first, after the tragedy, this is normal, but in the future it begins to interfere with returning to a full life. Sometimes inability to adapt to changed circumstances and helplessness serve the family. Other family members must come together to care for someone who has been hit hardest by the loss, and only because of this they feel strong and wealthy. Or the status quo is maintained - the family does not have to change their lifestyle. For example, a grandfather died after a long illness. While he was ill, a certain way of life developed in the family, including caring for the sick, and for some reason this state of affairs suits everyone. In this case, the family begins to disable the widowed grandmother, and with the best of intentions. "You survived such a tragedy. Why do you need to work, we will support you." nine0003

Or the status quo is maintained - the family does not have to change their lifestyle. For example, a grandfather died after a long illness. While he was ill, a certain way of life developed in the family, including caring for the sick, and for some reason this state of affairs suits everyone. In this case, the family begins to disable the widowed grandmother, and with the best of intentions. "You survived such a tragedy. Why do you need to work, we will support you." nine0003

The last, fourth task is to build a new relationship with the deceased and continue to live . In his early writings, Warden formulated this task as "taking the emotional energy out of the old relationship and placing it in the new relationship." However, he later abandoned this formulation, firstly, because of some of its mechanistic nature and, secondly, because it was understood by many as the disappearance of an emotional relationship to a deceased loved one. Therefore Vorden considered it necessary to clarify that the solution of the fourth task does not imply either oblivion or the absence of emotions, but only their restructuring. The emotional attitude towards the deceased must change in such a way that it becomes possible to continue living, to enter into new emotionally rich relationships. nine0003

The emotional attitude towards the deceased must change in such a way that it becomes possible to continue living, to enter into new emotionally rich relationships. nine0003

Many misunderstand this problem and therefore need therapeutic help to solve it, especially in the event of the death of one of the spouses. It seems to people that if their emotional connection with the deceased weakens, then by doing so they will offend his memory and this will be a betrayal. In some cases, there may be a fear that new close relationships may also end and have to go through the pain of loss again - this is especially common if the feeling of loss is still fresh. In other cases, the fulfillment of this task may be opposed by the close environment, for example, conflicts begin with children in the event of a new attachment from a widowed mother. There is often resentment behind this - a mother has found a replacement for her dead husband for herself, and for a child there is no replacement for a dead father. Or vice versa - if one of the children has found a partner, the widowed parent may have a protest, jealousy, a feeling that the son or daughter is going to lead a full life, and the father or mother is left alone. Often, the completion of the fourth task is hindered by the romantic belief that one loves only once, and everything else is immoral. This is supported by culture, especially in women. The behavior of the "faithful widow" is approved by society. According to the Harvard Grief Study, only 25% of older widows remarried, slightly higher percentage of young widows and widowers. And this despite the fact that 75% of divorced people remarry. nine0003

Or vice versa - if one of the children has found a partner, the widowed parent may have a protest, jealousy, a feeling that the son or daughter is going to lead a full life, and the father or mother is left alone. Often, the completion of the fourth task is hindered by the romantic belief that one loves only once, and everything else is immoral. This is supported by culture, especially in women. The behavior of the "faithful widow" is approved by society. According to the Harvard Grief Study, only 25% of older widows remarried, slightly higher percentage of young widows and widowers. And this despite the fact that 75% of divorced people remarry. nine0003

This task is interrupted by a ban on love, fixation on a past connection, or avoidance of the possibility of re-experiencing the loss of a loved one. All these barriers are usually accompanied by guilt.

A sign that this task is not being solved, grief does not subside and the period of mourning does not end, there is often a feeling that "life stands still", "after his death I do not live", anxiety grows. The completion of this task can be considered the emergence of a feeling that you can love another person, love for the deceased has not become less because of this, but after the death of, for example, a husband, you can love another man. That it is possible to honor the memory of a deceased friend, but at the same time adhere to the opinion that new friends may appear in life. Vorden cites as an example a letter from a girl who lost her father to her college mother: "There are other people to love. This does not mean that I love my father less." nine0003

The completion of this task can be considered the emergence of a feeling that you can love another person, love for the deceased has not become less because of this, but after the death of, for example, a husband, you can love another man. That it is possible to honor the memory of a deceased friend, but at the same time adhere to the opinion that new friends may appear in life. Vorden cites as an example a letter from a girl who lost her father to her college mother: "There are other people to love. This does not mean that I love my father less." nine0003

The moment that can be considered the end of mourning is not obvious. Some authors name specific time periods - a month, a year or two. Vorden believes that it is impossible to determine a specific period during which the experience of loss will unfold. It can be considered complete when a person who has experienced a loss has taken all four steps, solved all four tasks of grief. A sign of this, Vorden considers the ability to direct most of the feelings not to the deceased, but to other people, to be receptive to new impressions and life events, the ability to talk about the deceased without severe pain.