Psychology conspiracy theorists

Why people believe in conspiracy theories, with Karen Douglas, PhD

Kim Mills: Over the past year as COVID-19 rocketed around the world, conspiracy theories quickly followed. Last spring, dozens of cell phone towers were set a flame across Europe, amid conspiracy theories that the 5G towers were spreading COVID-19. In January, a Wisconsin pharmacist was charged with deliberately destroying hundreds of doses of the newly available COVID 19 vaccine because he believed a conspiracy theory that the vaccine would change human DNA. And some people are asserting that the virus itself was engineered by the Chinese.

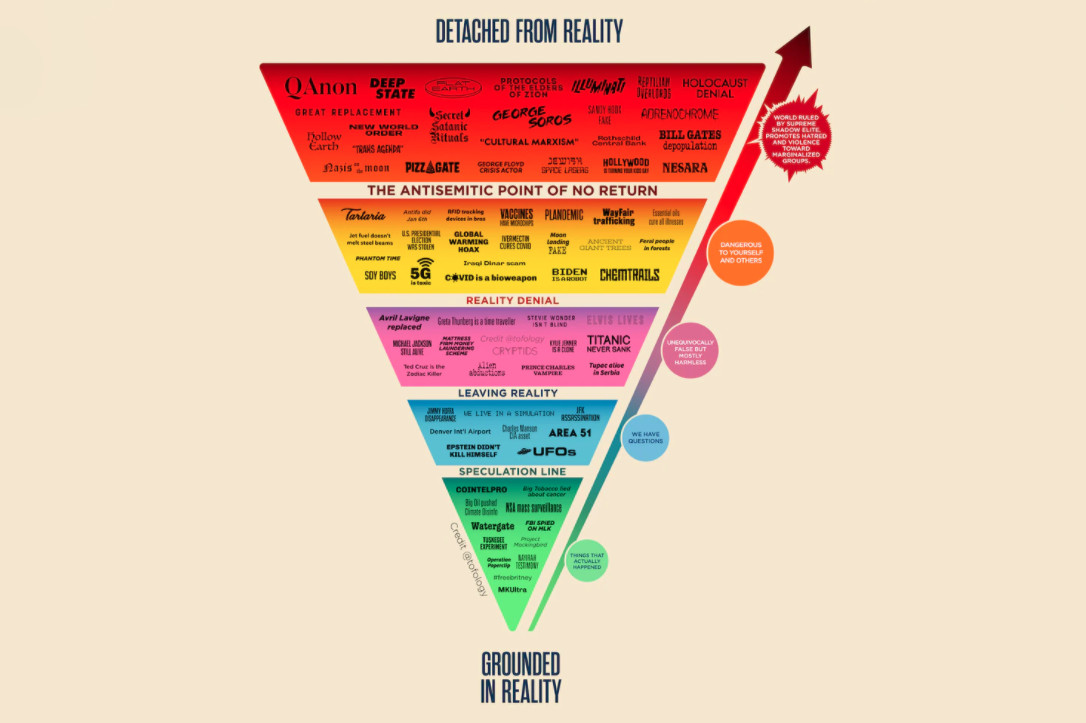

These aren't the only conspiracy theories making inroads right now. A September Pew Research Center survey found that more than half of Americans have heard at least a little about QAnon, the complicated web of pro-Trump conspiracy theories that originated on the message board 4chan. In November, two candidates who voiced support for QAnon theories were elected to Congress.

So how do conspiracy theories like these get started and why do they persist?

Who is most likely to believe them and why? Is there any way to combat conspiracy theories once they're out there? And what are the consequences for individuals and societies when they spread? Welcome to Speaking of Psychology, the flagship podcast of the American Psychological Association that examines the links between psychological science and everyday life.

I'm Kim Mills. Our guest today is Dr. Karen Douglas, a professor of social psychology at the University of Kent in the UK. Dr. Douglas has spent more than a decade studying conspiracy theories, and she joins us to talk about their history, causes, and consequences. Thank you for joining us, Dr. Douglas.

Karen Douglas, PhD: Hi Kim. Thank you very much for your invitation. Hi everybody.

Mills: So let's start with a definition. That's always a good place to launch. What counts as a conspiracy theory? I gave a few examples in the introduction, but how do you define conspiracy theories in your research? What are their common characteristics?

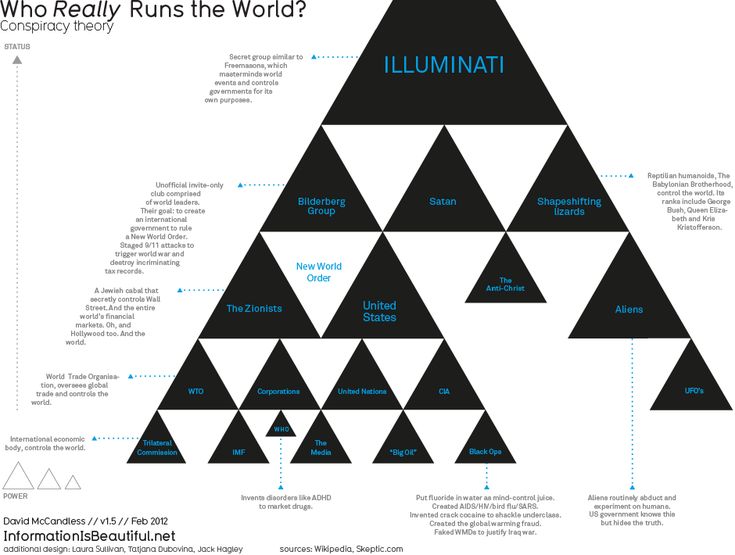

Douglas: Well, a conspiracy theory can normally be defined as a proposed plot carried out in secret, usually by a powerful group of people who have some kind of sinister goal. So something to gain from what they're doing and they usually don't have people's best interests at heart. Usually, their own interests at heart.

So something to gain from what they're doing and they usually don't have people's best interests at heart. Usually, their own interests at heart.

Mills: Some people think that the belief in conspiracy theorists has been on the rise in recent years fueled by social media, but in a paper a few years ago, you concluded that wasn't necessarily true. Instead, you found that conspiracy theories have always thrived during times of crisis and social upheaval with examples going back as far as the burning of Rome while Nero was away, and that the last decade hasn't been particularly more conspiracy prone than the past. Can you talk about that and how do researchers measure this?

Douglas: Sure. Yes, it is definitely the case that the conspiracy theories have ways being with us. Believing in conspiracy theories and being suspicious about the actions of others is in some ways quite an adaptive thing to do. We don't necessarily want to trust everybody and trust everything that's happening around us. And so they have always been with us and to some extent, people are all, I guess you could call everybody a conspiracy theorist if you want to use that term at one point or another.

And so they have always been with us and to some extent, people are all, I guess you could call everybody a conspiracy theorist if you want to use that term at one point or another.

And so yeah, they've always been there. People have always believed in conspiracy theories. As far back as we can remember, people have been having these conspiracy beliefs and having these suspicions about the actions of hostile collectives of individuals. This is just the way that we are wired up to some degree. And in terms of how we measure the extent to which people believe in conspiracy theories, you can do this in a variety of different ways. And as a social psychologist now, we would normally measure a belief in conspiracy theories by simply asking people questions about the extent to which they endorse a particular idea or the extent to which they believe a particular statement is true.

And you can measure these sorts of beliefs on specific issues. So for example, if you want to know how much somebody believes in anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, then you can ask people to read a bunch of statements about anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. So for example, that the pharmaceutical companies are hiding information about vaccine efficacy and safety. And then you ask them how much they believe that statement or how much they agree with it, how much they think it's plausible. There are various different ways that you can do this. And another way to tap into what some would argue is an underlying tendency to just believe conspiracy theories more generally.

So for example, that the pharmaceutical companies are hiding information about vaccine efficacy and safety. And then you ask them how much they believe that statement or how much they agree with it, how much they think it's plausible. There are various different ways that you can do this. And another way to tap into what some would argue is an underlying tendency to just believe conspiracy theories more generally.

You can ask more general questions or ask people to rate the extent to which they believe in statements such as governments often hide secrets from people to suit their own ends. So more general notions of conspiracy like that. So we'll just ask participants to read these sort of segments and write the extent to which they agree with them. Usually on a scale from I strongly disagree to I strongly agree that kind of thing. And then usually what we will do is come up with an average conspiracy belief measure or score I suppose total for each individual. And then we'll look for associations between that kind of belief and various other psychological factors as well.

Mills: So the belief is generally, always out there. The conspiracies may change over time, but I'm wondering, have there been times in history that you've seen when conspiracy theories have spiked?

Douglas: Not necessarily, it's not something I really research in my own studies, but naturally a lot of people are very concerned at the moment that we're seeing a bit of a spike and believing conspiracy theories with the whole coronavirus situation and also in the USA with the recent presidential election. And I guess time will tell if conspiracy theories have I guess, been on the rise in this particular point in time compared to times in the past or times in the future.

But there is definitely quite a lot of concern that conspiracy theories are on the rise. It's difficult for me to say whether or not they are, because I don't really have the data to support one way or another. But I think that it is definitely the case that even if we can't say for sure that social media has increased conspiracy theories, it's certainly changed the way in which people access this information, the ways in which they share this information, and also I feel that in many cases, for people who do have, I guess, an underlying tendency to believe in a particular conspiracy theory or conspiracy theories in general, it's much easier for people to find this sort of information now than it ever has been before.

And people can become consumed by this information. They can only seek out this information online. So they can go to particular sources, disregard other sources that contradict their views so that they end up, if anything, their attitudes about these particular alleged conspiracies rather sorry, can become even more polarized. So people's attitudes might become stronger. So I guess what I'm trying to say is that even if we don't have evidence that conspiracy theorizing has increased, and time will tell whether or not that's true. I do think that people's attitudes have become stronger as a result of interacting and sharing and consuming this information on social media and on the internet generally.

Mills: I'm just wondering, I think I read that there may have been a measurable increase in conspiracy theorizing around the turn of the 20th century because of the industrial revolution. And then also around the end of the Second World War in the beginning of the Cold War. Is that accurate?

Is that accurate?

Douglas: I think I have come across one study which suggests that that's the case. But yeah the evidence is really quite limited and only drawn from a particular type of sources, like letters to newspapers and that sort of thing. So it's really difficult to tell, but it does make sense to me that there would have been particular periods in history that conspiracy theories would have been more prominent. And personally, I think we might be in one of those periods right now.

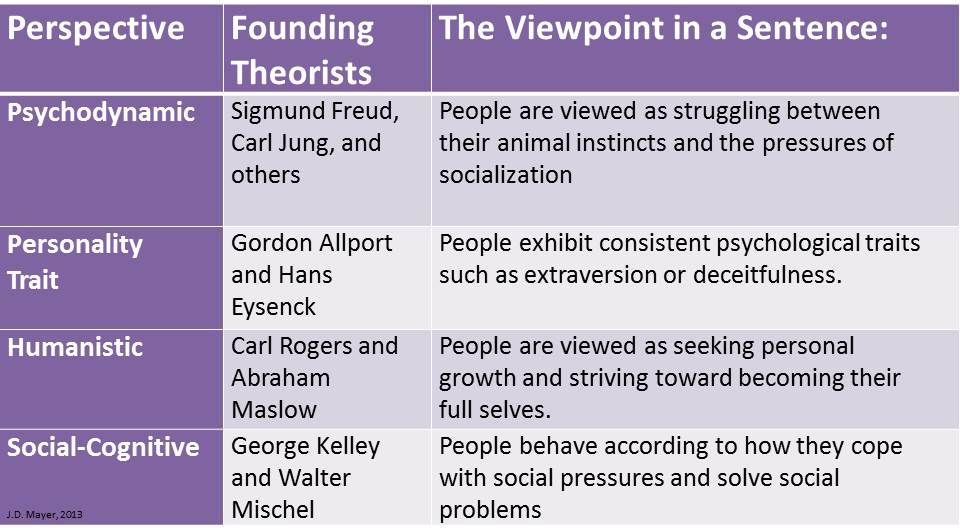

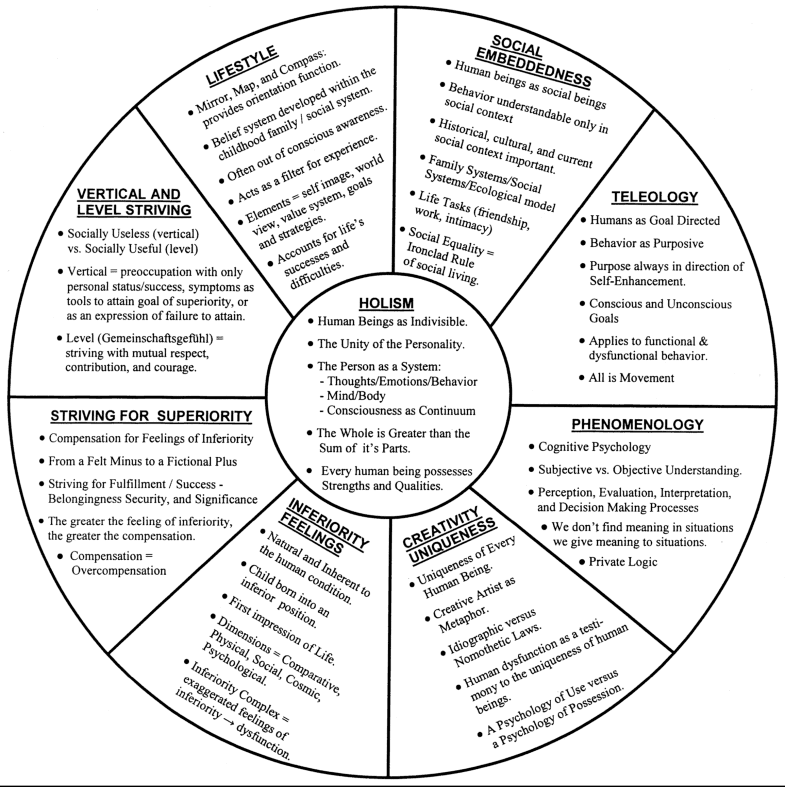

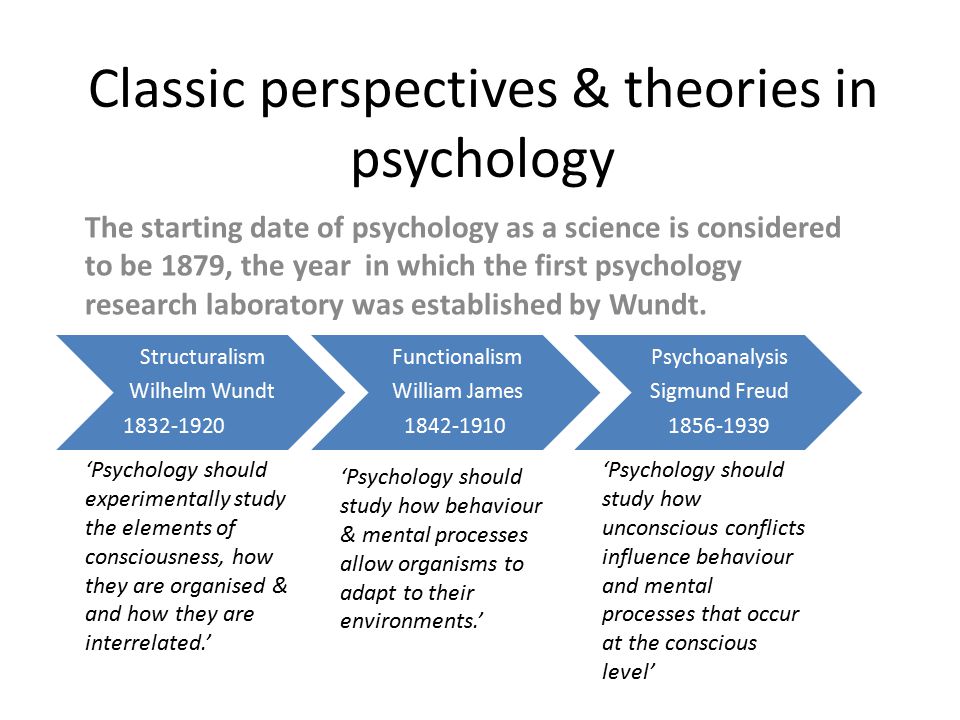

Mills: Let's talk a little bit about the psychological factors that motivate people to believe in conspiracy theories. I know you've laid out in your research three areas that you call epistemic, existential and social motives. Can you explain what they are, what those terms mean?

Douglas: Yes, of course. We argue that people are drawn to conspiracy theories in order to satisfy or in an attempt to satisfy three important psychological motives. The first of these motives are epistemic motives. I guess in a nutshell, epistemic motives really just refer to the need for knowledge and certainty and I guess the motive or desire to have information. And when something major happens, when a big event happens, people naturally want to know why that happened. They want an explanation and they want to know the truth. But they also want to feel certain of that truth.

The first of these motives are epistemic motives. I guess in a nutshell, epistemic motives really just refer to the need for knowledge and certainty and I guess the motive or desire to have information. And when something major happens, when a big event happens, people naturally want to know why that happened. They want an explanation and they want to know the truth. But they also want to feel certain of that truth.

And some psychological evidence suggests that people are drawn to conspiracy theories when they do feel uncertain either in specific situations or more generally. And there are other epistemic reasons why people believe in conspiracy theories as well in relation to this sort of need for knowledge and certainty. So people with lower levels of education tend to be drawn to conspiracy theories. And we don't argue that's because people are not intelligent. It's simply that they haven't been allowed to have, or haven't been given access to the tools to allow them to differentiate between good sources and bad sources or credible sources and non-credible sources. So they're looking for that knowledge and certainty, but not necessarily looking in the right places.

So they're looking for that knowledge and certainty, but not necessarily looking in the right places.

The second set of motives, we would call existential motives. And really they just refer to people's needs to be or to feel safe and secure in the world that they live in. And also to feel that they have some kind of power or autonomy over the things that happen to them as well. So again, when something happens, people don't like to feel powerless. They don't like to feel out of control. And so reaching to conspiracy theories might, I guess, at least allow people to feel that they have information that at least explains why they don't have any control over this situation. Research has shown that people who do feel powerless and disillusioned do tend to gravitate more towards conspiracy theories.

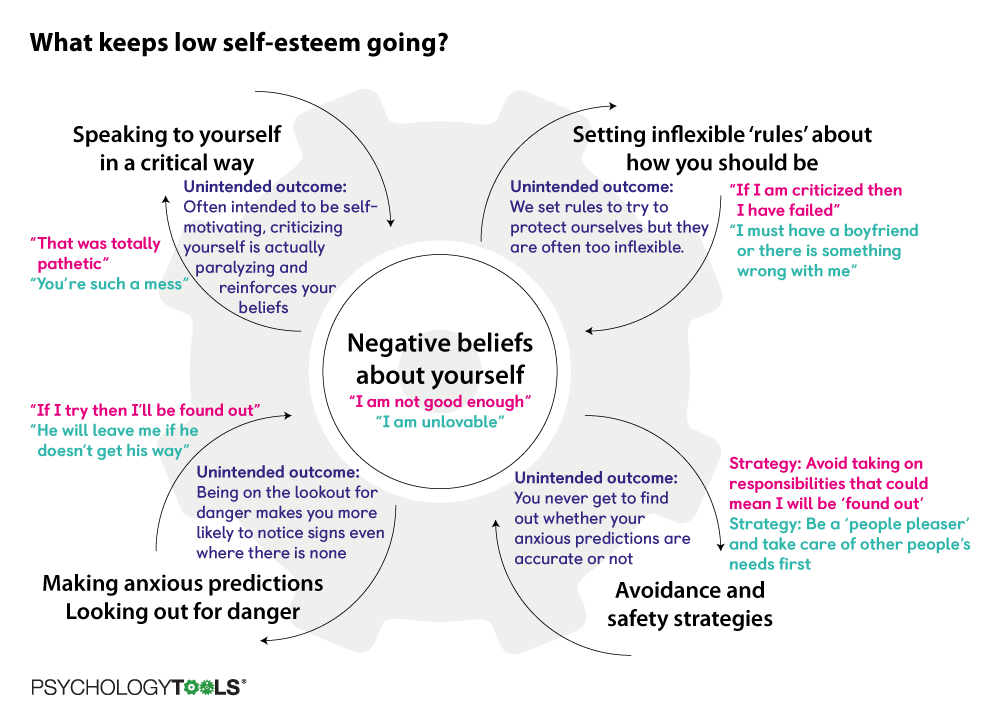

The final set of motives we would call social motives and those refer to people's desire to feel good about themselves as individuals and also feel good about themselves in terms of the groups that they belong to. And I guess at the individual level, people like to feel... Well, they like to have high self-esteem. They like to feel good about themselves. And potentially one way of doing that is to feel that you have access to information that other people don't necessarily have.

And I guess at the individual level, people like to feel... Well, they like to have high self-esteem. They like to feel good about themselves. And potentially one way of doing that is to feel that you have access to information that other people don't necessarily have.

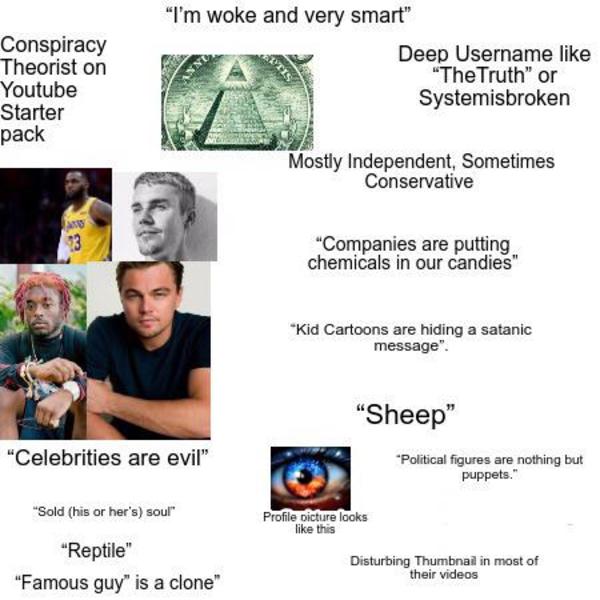

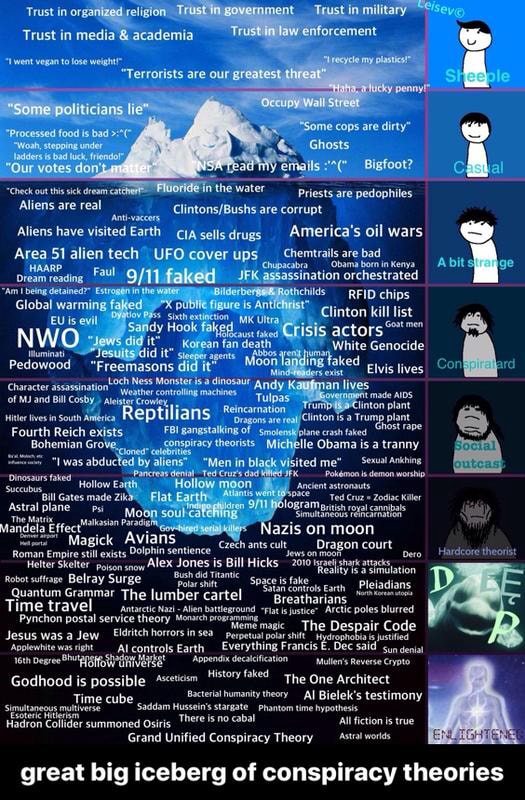

And this is quite a common rhetorical tool that people use when they talk about conspiracy theories, that everybody else is some kind of sheep, but that they know the truth. They have the truth. And having that kind of belief, I guess, feeling that you're in possession of information that other people don't have, can give you a feeling of superiority over others. And we have found, and others have shown as well that a need for uniqueness and a need to have, I guess, stand out from others is associated with belief in conspiracy theories.

And this happens at the level of the group as well. So people who have an overinflated sense of the importance of the groups that they belong to, but at the same time, the feeling that those groups are underappreciated, those kinds of feelings as well, draw people towards conspiracy theories, especially conspiracy theories about their groups. So in having those sorts of beliefs, you can maintain the idea that your group is good and moral and upstanding, whereas others are the evil doers out there who are trying to ruin it for everybody else.

So in having those sorts of beliefs, you can maintain the idea that your group is good and moral and upstanding, whereas others are the evil doers out there who are trying to ruin it for everybody else.

Those three main motives... Those three psychological motives, the epistemic, existential and social, it's possible to summarize, I guess, the psychological literature on conspiracy theories into those three motivations. So yeah, that's what we argue.

Mills: What role, if any, does narcissism play in belief in conspiracy theories? People who tend to be more narcissistic also believe in these theories as a means of getting the social capital?

Douglas: Yes, absolutely. That is true. And that's kind of what I was referring to. It's linked to the idea of need for uniqueness, as well. That's another, I guess, narcissistic notion that you have. You're in possession of information that other people don't have. You're different to other people and it makes you stand apart. But yes, narcissism at an individual level has been associated in quite a few studies now with belief in conspiracy theories.

But yes, narcissism at an individual level has been associated in quite a few studies now with belief in conspiracy theories.

And also this narcissism at the group level as well, so an over inflated sense of the importance of your own group. That kind of insecure feeling about your own group is also associated with belief in conspiracy theories. So yes, narcissism is one of those individual differences, variables that correlate with belief in conspiracy theories.

Mills: So a few moments ago, you talked about education level as being a factor. And I'm wondering what about other demographic categories such as age or gender? Do you see any associations between those and tendency to believe in conspiracy theories?

Douglas: Yes. In terms of age, we do. In our research, we generally find that older people believe in conspiracy theories less than younger people do. That tends to show up in most of the studies that we have run. So there's simply a correlation between conspiracy belief and age. That is a negative correlation, so the older you are, the less you believe in conspiracy theories. Or the other way around the younger you are, the more you believe in conspiracy theories. And that does tend to show up pretty much all of the time. In terms of gender, at least in the research that myself and my colleagues have conducted, we've never found any gender differences in terms of conspiracy belief. So as we measure belief in conspiracy theories using these psychological scales, we have never found that men believe more than women or women believe more than men or whatever. We've never found anything like that.

That is a negative correlation, so the older you are, the less you believe in conspiracy theories. Or the other way around the younger you are, the more you believe in conspiracy theories. And that does tend to show up pretty much all of the time. In terms of gender, at least in the research that myself and my colleagues have conducted, we've never found any gender differences in terms of conspiracy belief. So as we measure belief in conspiracy theories using these psychological scales, we have never found that men believe more than women or women believe more than men or whatever. We've never found anything like that.

I think one or two studies may have shown gender differences for specific conspiracy theories. I know of a recent study that, and I can't remember which direction it went in actually, but that showed that in terms of COVID-19 conspiracy theories, there was some kind of gender difference. But personally, I've never found that, which I think is very interesting and counter-intuitive in a way. Because if people think about the prototypical conspiracy theorist, again, if you want to use that term to describe people, then they do tend to think of a middle-aged white man, usually. And that may be the case for the prominent conspiracy theorists. Your well-known people who propagate these conspiracy theories, but not necessarily your everyday person who's consuming this information on the internet and deciding whether or not it's true. We don't really find those gender differences there.

Because if people think about the prototypical conspiracy theorist, again, if you want to use that term to describe people, then they do tend to think of a middle-aged white man, usually. And that may be the case for the prominent conspiracy theorists. Your well-known people who propagate these conspiracy theories, but not necessarily your everyday person who's consuming this information on the internet and deciding whether or not it's true. We don't really find those gender differences there.

Mills: That's really interesting. I mean, because it is when we just had this overrun of the U.S. Capitol here in Washington and it looked like there were a lot of younger and middle-aged men out there. I mean, certainly there were women involved, but that was the sense. And of course that is the conspiracy theory that the Trump election was stolen.

Douglas: Yes. Yeah, that's true. That's extremely interesting. And of course I was watching this on the news as well and thinking very much the same thing. But I think that there probably is a difference in the person who sits at home and reads this information on the internet and then decides whether or not it's true and the individuals who are prepared to actually go and storm a building or to go out and actively cause trouble based on these conspiracy beliefs. So there's probably a lot going on there, but in terms of the way we measure belief in conspiracy theories, we just don't, with these sorts of gender differences that might seem obvious, don't seem to play out really in the research that we do on the everyday population, I suppose.

But I think that there probably is a difference in the person who sits at home and reads this information on the internet and then decides whether or not it's true and the individuals who are prepared to actually go and storm a building or to go out and actively cause trouble based on these conspiracy beliefs. So there's probably a lot going on there, but in terms of the way we measure belief in conspiracy theories, we just don't, with these sorts of gender differences that might seem obvious, don't seem to play out really in the research that we do on the everyday population, I suppose.

Mills: Another of your studies found that people who believe in one conspiracy theory are more likely to believe in others, even when those theories directly contradict each other. So for instance, the more your participants believe that Princess Diana faked her own death, the more they also believe that she was murdered. And of course, that doesn't make any sense. Can you help explain that?

Douglas: Yeah, of course. Yes. We feel that is a very interesting finding. Obviously we kind of, I guess, started from the point that in the literature it's often been found that if people believe in one conspiracy theory, then they're likely to believe in others. So in other words, there's something that kind of holds these beliefs together. So we were interested to find out, well, what is this? This underlying belief system or underlying attitude that might mean that these conspiracy beliefs are held at the same time, even if they do contradict one another.

Yes. We feel that is a very interesting finding. Obviously we kind of, I guess, started from the point that in the literature it's often been found that if people believe in one conspiracy theory, then they're likely to believe in others. So in other words, there's something that kind of holds these beliefs together. So we were interested to find out, well, what is this? This underlying belief system or underlying attitude that might mean that these conspiracy beliefs are held at the same time, even if they do contradict one another.

So we set to do these studies, and so we asked participants in these studies to rate the extent to which they agree with different conspiracy theories. One, for example, that Princess Diana was assassinated by the royal family. Another one that she was assassinated by MI5, nothing to do with the royal family or others, also, but crucially, I think, one that she was assassinated and is dead. And another, that she was helped to fake her own death and that she's sort of living it up somewhere on an island having a great time. So basically, it's not possible to be dead and alive at the same time. And also, participants-

So basically, it's not possible to be dead and alive at the same time. And also, participants-

Mills: Unlike Schrodinger's cat.

Douglas: Yeah, well, that's it. We thought people would not entertain these two conspiracy theories at the same time, but it turned out that they did, or at least they were prepared to entertain the idea that both of those things might be true.

But we also measured the extent to which people believed in, I guess, an underlying conspiracy theory that something just isn't right. Something's up and something is being covered up. And what we found was that some people did indeed endorse these contradictory conspiracy theories, or again, at least were likely to entertain those two ideas at the same time. But once we also took into account the extent to which they believed that there was just something up, then that relationship actually disappeared. So it was the relationship between the contradictory beliefs was explained by the, I guess, underlying belief that just something is being covered up.

So you can explain why people will entertain these contradictory ideas, because both of those ideas are consistent with the underlying idea that there's just something not quite right. So it's not necessarily to say that they will definitely believe that Princess Diana is dead and at the same time believe that she's still alive, but they'll be happy to entertain the idea that those two things are possible, as long as they also entertain the belief that there was just something that wasn't right about those events.

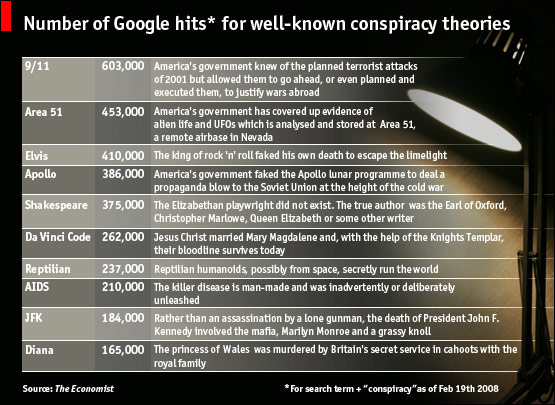

Mills: Yeah. That helps explain it, at least a little bit. Well, what makes a conspiracy theory catch on and have staying power? Are there certain types of theories that are stickier than others or some that are more enduring? Like the earth is flat has been around since forever. So are there characteristics that make them stickier?

Douglas: That's not something that I've done research on myself, to be honest, but I think it's a fascinating question. It's very true that some conspiracy theories stand the test of time and others just disappear. I think that there must be certain features of conspiracy theories, the ones that last and the ones that don't. I don't personally know exactly what they are, but I guess one thing that tends to be very, very common is that the event is very, very large. The event that is explained by the conspiracy theory is very, very large and important and usually involving something of great political or social significance. A lot of other conspiracy theories that you might come across just sort of disappear. I guess a lot of the time we just don't really know why they don't catch on. But plenty of them do. Yeah. It's a really interesting question.

It's very true that some conspiracy theories stand the test of time and others just disappear. I think that there must be certain features of conspiracy theories, the ones that last and the ones that don't. I don't personally know exactly what they are, but I guess one thing that tends to be very, very common is that the event is very, very large. The event that is explained by the conspiracy theory is very, very large and important and usually involving something of great political or social significance. A lot of other conspiracy theories that you might come across just sort of disappear. I guess a lot of the time we just don't really know why they don't catch on. But plenty of them do. Yeah. It's a really interesting question.

Mills: It's a line of research for you to pursue.

Douglas: Yeah, yeah. Oh, yeah. There definitely is. Yeah. I think that other researchers have started to ask these sorts of questions, and I have tried myself to, I guess, not taxonomize, but sort of almost, I guess, not even categorize conspiracy theories, but try to isolate some of these features. But it's actually very difficult, because there are so many of them about so many different events.

But it's actually very difficult, because there are so many of them about so many different events.

And you pointed out the flat earth conspiracy theory, which has been around forever but kind of died away for a long time and then in recent years just seems to have gotten popular again, and I do find it quite difficult to explain that. I mean, I have a theory about that conspiracy theory, that just generally people are becoming less trustful of science and scientists at the present time, which is why we might be seeing these sorts of ideas making a bit of a comeback. But yeah, no. I think it's a really, really fascinating question, because it's not that even though some of them disappear, they go away, but then they come back again or come back again in a different form or certain conspiracy theories about particular things, like say anti-vaccine or health-related conspiracy theories can kind of reinvent themselves for new things that happen, like 5G conspiracy theories about people getting sick from [inaudible 00:25:10] masks and things like that.

So these sorts of conspiracy theories have always been there. They kind of mutate, I suppose, if you like. They change. But yeah, I think it is a really fascinating question and one that I can't, as a social psychologist, can't really answer very well, unfortunately.

Mills: Is there any way to effectively debunk a conspiracy theory once it's out there? I mean, can you just present the facts? Like you talked about the anti-vaxxers, the fact that the Lancet article that led to a lot of beliefs that children were becoming autistic as a result of vaccines. And then it turned out that that article was bogus. It was based on faulty data and it was retracted, and yet some people are still hanging on to that. So is there a way to stop these theories from continuing to swirl?

Douglas: Yes. There are ways to do this, but of course, it's extremely challenging. It's very, very difficult. Once these conspiracy theories are out there and people believe them, then sometimes people can very, very strongly hold on to these beliefs and defend them very, very strongly as well. And once these attitudes are very, very strong, of course, from other areas of psychology we know that attitudes that are very strongly held are difficult to dispute, I guess. Difficult to change. It's very difficult to change these sorts of attitudes.

And so, yes, it is a challenge, but there are things that that can be done. And a lot of research that, especially in very, very recent years as well, has started to come out in terms of how do you address misinformation? How do you address conspiracy theories? And giving people the facts does work under certain situations. In some of our own research, we've actually found that it's quite effective to provide people with factual information, provide people with the facts. And this was particularly about vaccines before they're exposed to conspiracy theories, and then the conspiracy theory fails to gain traction. But once the people have been exposed to the conspiracy theory, they're giving them the, I guess,... Sorry, the appropriate or correct information afterwards doesn't really work. So, others have taken this information and have started to look at ways to inoculate people against misinformation and to inoculate people against conspiracy theories and fake news and all sorts of other things, which seems to be working as well. So, in other words, you give people either the correct information or some piece of weak misinformation before they're exposed to the worst of it, then that helps them to be able to resist it.

There are other techniques that people have used, that researchers have used, as well, and just to give you one other example, some researchers have looked at the idea of presenting people with a pre-warning or a forewarning that they might be exposed to misinformation. And if people believe that information that they might receive could be misleading, and they have that information up front, then that can sometimes help them to resist the misinformation as well. Now, I think these are all really, really valuable tools, but of course, sometimes the misinformation is all ready out there so it's difficult to get to people beforehand. So, then, you have to resort to, I guess, traditional debunking techniques, such as going in with consistent, strong counter arguments.

So, then, you have to resort to, I guess, traditional debunking techniques, such as going in with consistent, strong counter arguments.

But I think that these other techniques provide real opportunities to help people to resist conspiracy theories in general that they might come across in the future. So, if you give people these sorts of, I guess, ways to critically think about information and think, "Well, okay, I could be exposed to misinformation. That misinformation is out there, so I'm going to be on the lookout for it," then it might actually help people to resist it when they come across it next time. If that makes sense.

Mills: Yeah. It sounds like the techniques that they're trying to use right now with the COVID-19 vaccines, telling people up front that if you happen to be particularly allergic, you might have a reaction. This is what to expect. And yet, it's like a game of whack-a-mole because they talk about all of this and they're trying to be as transparent as possible, and yet, along comes somebody who says that the mRNA that's involved in this is actually going to change the DNA in your body. How do you fight that?

How do you fight that?

Douglas: Yeah. It is very, very difficult, and there are new conspiracy theories all the time. It is exactly like that game. You've got one and then you're constantly trying to hit another one away. It is very, very challenging. There's a lot out there, a lot going on out there.

Mills: And of course, this is all complicated by the fact that sometimes conspiracies do exist and sometimes people may have deep-seated, valid reasons to distrust authority. So, for example, public opinion polls have found that Black Americans are less likely to say they'll take the COVID vaccine and more wary of its safety because they have a long history of being abused and mistreated by the medical establishment. So, is there a way for people to balance this awareness with a healthy skepticism of conspiracy theories?

Douglas: Yes. Again, this is extremely challenging, and you're absolutely right, that some people have very good reasons to be suspicious of these sorts of things because of past events. And so, the challenge becomes even greater. And I don't know the solution to this, apart from the fact that people who are attempting to fight the misinformation will need to be sensitive to these concerns and perhaps be more targeted in their efforts to debunk misinformation, being sensitive to these historical events as well.

And so, the challenge becomes even greater. And I don't know the solution to this, apart from the fact that people who are attempting to fight the misinformation will need to be sensitive to these concerns and perhaps be more targeted in their efforts to debunk misinformation, being sensitive to these historical events as well.

So, it can't necessarily be a one size fits all approach to misinformation, just can't be because everybody's circumstances are different, and we know that different communities feel differently about vaccines and various other things as well, for very good reasons. So, that, of course, is a huge challenge for anybody trying to deal with potential misinformation about vaccines and other things, but also, yeah, particularly with COVID, a reluctance to take the vaccine.

Mills: So, what aspects of conspiracy theory are you looking at today? What's your research heading toward?

Douglas: Quite a few things going on at the moment, actually. I'm really interested in, I guess, the deliberate use of conspiracy theories as a political device. So, I've been doing some research, I guess, looking at how people perceive others who seem to use conspiracy theories, and whether or not they see those actions as intentional or deliberate, and also what the effects are of that. I've also been interested in the term conspiracy theory itself and the term conspiracy theorist and how people use those terms, whether they use them to, I guess, specifically put down other people's ideas, or if they simply use these terms when they just don't believe... that they don't believe a particular idea, and also the effects of these terms on whether or not someone will actually believe something.

I'm really interested in, I guess, the deliberate use of conspiracy theories as a political device. So, I've been doing some research, I guess, looking at how people perceive others who seem to use conspiracy theories, and whether or not they see those actions as intentional or deliberate, and also what the effects are of that. I've also been interested in the term conspiracy theory itself and the term conspiracy theorist and how people use those terms, whether they use them to, I guess, specifically put down other people's ideas, or if they simply use these terms when they just don't believe... that they don't believe a particular idea, and also the effects of these terms on whether or not someone will actually believe something.

What else have I been doing? Oh, quite quite a few things going on. I've been writing quite a bit about COVID-19 conspiracy theories, and also, quite generally, my research is focused a lot on the consequences of believing in conspiracy theories as well. So, in different areas like in vaccines, climate change, politics in various different domains, specifically what impact do conspiracy theories have on people's attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. So, I've been doing a lot on that sort of thing.

So, in different areas like in vaccines, climate change, politics in various different domains, specifically what impact do conspiracy theories have on people's attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. So, I've been doing a lot on that sort of thing.

Mills: Well, it's an amazing area for a scrutiny, and appreciate the work that you're doing here and helping us to better understand some of the ways that people's minds work. So, thank you so much for joining us today, Dr. Douglas.

Douglas: Well, thank you. It's been a pleasure.

Mills: If you'd like to learn more about psychological research on conspiracy theories and other types of misinformation, check out the Monitor on Psychology, the magazine of the American Psychological Association. You can find it at www.apa.org/monitor. You can find previous episodes of Speaking of Psychology on our website at www.speakingofpsychology.org, or wherever you get your podcasts. If you have comments or ideas for future podcasts, email us at speakingofpsychology@apa. org. That's speakingofpsychology, all one word, @apa.org. Speaking of Psychology is produced by Lea Winerman. Our sound editor is Rob Aneiva. Thank you for listening to the American Psychological Association. I'm Kim Mills.

org. That's speakingofpsychology, all one word, @apa.org. Speaking of Psychology is produced by Lea Winerman. Our sound editor is Rob Aneiva. Thank you for listening to the American Psychological Association. I'm Kim Mills.

Why Do People Believe Them?

A conspiracy theory is an idea that a group of people is working together in secret to accomplish evil goals.

Now, sometimes in the real world, people indeed do wicked things. We just have to look at criminal networks like the mafia, terrorist groups, and sex trafficking rings, for example. Even high-level political figures and celebrities get involved from time to time.

In other words, real conspiracies do exist.

So, how do you tell the difference between real plots and conspiracy theories? Well, sometimes you don’t know right away, but there are ways to find out.

Criminal cases are built on solid and provable evidence — not hunches, coincidences, or fabricated information like memes or social media posts.![]()

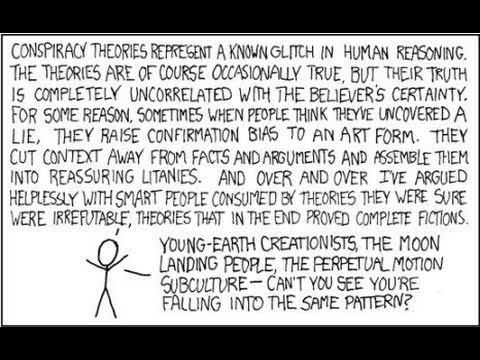

On the other hand, when you closely examine the facts, conspiracy theories don’t hold up.

What makes conspiracy theories more deceptive is that they are woven into real-life events — all strung together in a fictional way. So, in some instances, they might make sense. But when you dig deeper, you start noticing the lack of consistency and fact-based proof.

And no, lack of proof shouldn’t be taken as evidence for the conspiracy. That’s the whole point.

Conspiracy theories often take flight during unsettling times.

For example, in a pandemic, during a close election in a politically divided country, or after a terrorist attack.

Why is that?

Painful and uncertain times might lead many people to find alternative ways to make sense of such a shocking or painful situation.

Following a conspiracy theory might help you feel you understand the events, and, in turn, this could alleviate some uncertainty and anxiety.

There’s more to conspiracy theories than the need to make sense of shocking events, though.

Personality traits of conspiracy theorists

Is everyone vulnerable to conspiratorial thinking? Not necessarily.

Conspiracy theory experts have found that certain cognitive styles and personality traits might be common among people who believe in them.

According to a 2018 study, people who believe in conspiracy theories tend to show personality traits and characteristics such as:

- paranoid or suspicious thinking

- eccentricity

- low trust in others

- stronger need to feel special

- belief in the world as a dangerous place

- seeing meaningful patterns where none exist

The strongest predictor of belief in conspiracy theories, according to the study, is having a personality that falls into the spectrum of schizotypy.

Schizotypy is a set of personality traits that can range from magical thinking and dissociative states to disorganized thinking patterns and psychosis.

Examples of mental health conditions in the schizotypy spectrum include schizotypal and schizoid personality disorders and schizophrenia.

Not all schizotypy personality traits translate into a personality or psychiatric disorder, though.

Many people have one or two symptoms of schizotypy but don’t qualify for a full diagnosis.

Preliminary research also suggests that belief in conspiracy theories is linked to people’s need for uniqueness. The higher the need to feel special and unique, the more likely a person is to believe a conspiracy theory.

Other personality traits commonly linked to the tendency to believe or follow conspiracy theories include:

- narcissism

- low agreeableness

- Machiavellianism

- openness to experience

The link between personality traits and personal beliefs is a complex one that cannot be explained by isolating social and cultural factors, though. Research on the topic is still limited.

Suspicion: An evolutionary advantage?

Humans seem to be prone to suspicious thoughts and paranoia.

In fact, some experts have studied paranoia and suspicious thoughts as an important evolutionary advantage.

One of them is professor of clinical psychiatry Richard A. Friedman, MD, who writes in his viewpoint paper, “Why Humans Are Vulnerable to Conspiracy Theories”:

“Having the capacity to imagine and anticipate that other people might form coalitions and conspire to harm one’s clan would confer a clear adaptive advantage: a suspicious stance toward others, even if mistaken, would be a safer strategy than carefree trust.”

In other words, from an evolutionary perspective, a conspiracy theory might help you stay safer if your rival attacks, as you have already anticipated their moves.

“The paranoia that drives individuals to constantly scan the world for danger and suspect the worst of others probably once provided a similar survival edge,” Friedman adds.

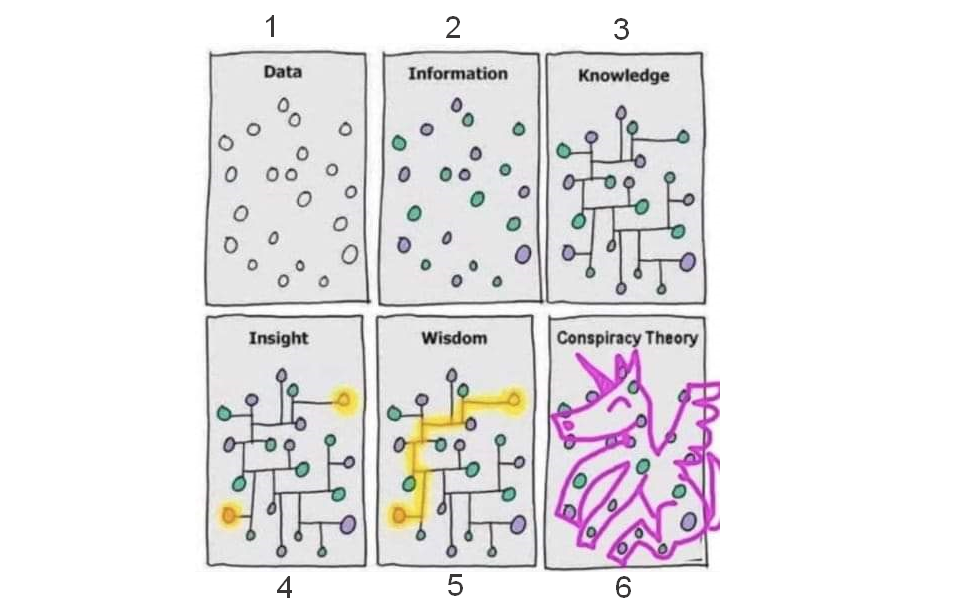

Illusory patterns

Believing in conspiracy theories can also be linked to distortions in cognitive processes.

Illusory pattern perception refers to perceiving meaningful or coherent connections between nonrelated events.

In other words, a distortion in how you think might make you prone to seeing patterns between events where there are none.

A 2018 study tested this theory and found that distortions of normal cognitive processes were repeatedly associated with conspiracy and irrational beliefs.

In the study, under controlled circumstances, participants detected patterns in randomly generated stimuli. This helped them make sense of their environment and respond well to each situation, even when the connections didn’t really exist.

A 2008 study found that lacking control in a situation increased a person’s likelihood to perceive nonexistent patterns, including developing superstitions and believing in conspiracies.

Participants who felt they lacked control connected unrelated events more often than participants who felt they understood and had some degree of control in a situation.

Apophenia: The tendency to connect the dotsThe human tendency to seek and find patterns everywhere is indeed something that has often been linked to believing in conspiracy theories.

The human brain has evolved into seeing patterns in just about everything. It’s an evolutionary advantage but also a natural tendency.

We recognize animal figures in the clouds or uncover creepy faces in the bathroom wallpaper at night. If we meet three new friends — all named Bill — we tend to notice.

It doesn’t mean that every time we connect the dots we are right, though.

In fact, Friedman explains that humans detect patterns in randomness in an effort to make sense of the world quickly. This process, though, makes us prone to cognitive errors, such as “seeing connections between events when none exist.”

“For a species so intent on connecting the dots and making sense of the world, this information-rich environment is fertile ground for confusion and conspiracy theories,” Friedman explains.

There’s actually a name for this phenomenon: apophenia. This is the tendency to perceive a meaningful connection within random situations.

In other words, you take elements that are near each other by chance, and you see a meaningful and purposeful connection between them.

Experienced game designer Reed Berkowitz says that apophenia is common in the gaming world.

Take one of his games, for example. The goal is to find a clue in a basement to move to the following phase of the game.

The real clue placed by gamers was obvious. However, many of the players overlooked it and instead noticed a few loose floorboards. Then, they concluded their shape was an arrow pointing toward a wall. Consequently, they started tearing down the wall.

“These were normal people, and their assumptions were normal and logical and completely wrong,” Berkowitz wrote in a 2020 column.

There are different types of apophenia. These include:

Pareidolia, or connecting different visual elements and stimuli to form a nonexistent pattern. For example, seeing a face on the bark of a tree, or a specific sign in a light projected on the White House.

Clustering, or the tendency to find a pattern in a random sequence of data. For example, finding logic in a randomly generated sequence such as xvvxvvxxxvx, or seeing a trend in stock market fluctuations.

For example, finding logic in a randomly generated sequence such as xvvxvvxxxvx, or seeing a trend in stock market fluctuations.

Gambler’s fallacy, or the inaccurate belief that if an event repeatedly happens during a certain time period, it will then occur less often in the future (or vice versa.) For example, if you toss a coin and get heads four times in a row, you’ll likely bet it’ll be tails next time.

Confirmation bias, or the “my way bias,” refers to the process of disregarding information that might disprove a belief while seeking information that supports it. For example, believing someone often sends secret messages in their speech will make you more likely to find secret messages in such speeches, even when that’s not the case.

A mathematical explanation

Following apophenia, there’s the Ramsey theory. This theory states that any large structure will implicitly contain patterns if you really pay attention.

That way, even in mathematics and geometry, patterns can be found whenever there are enough elements to connect.

So, according to the Ramsey theory, if you were to line up the text of just about any book, you’d find “hidden” words and sometimes several “meaningful” ones in a row.

In other words, if you’re looking for clues somewhere, you’re bound to find some!

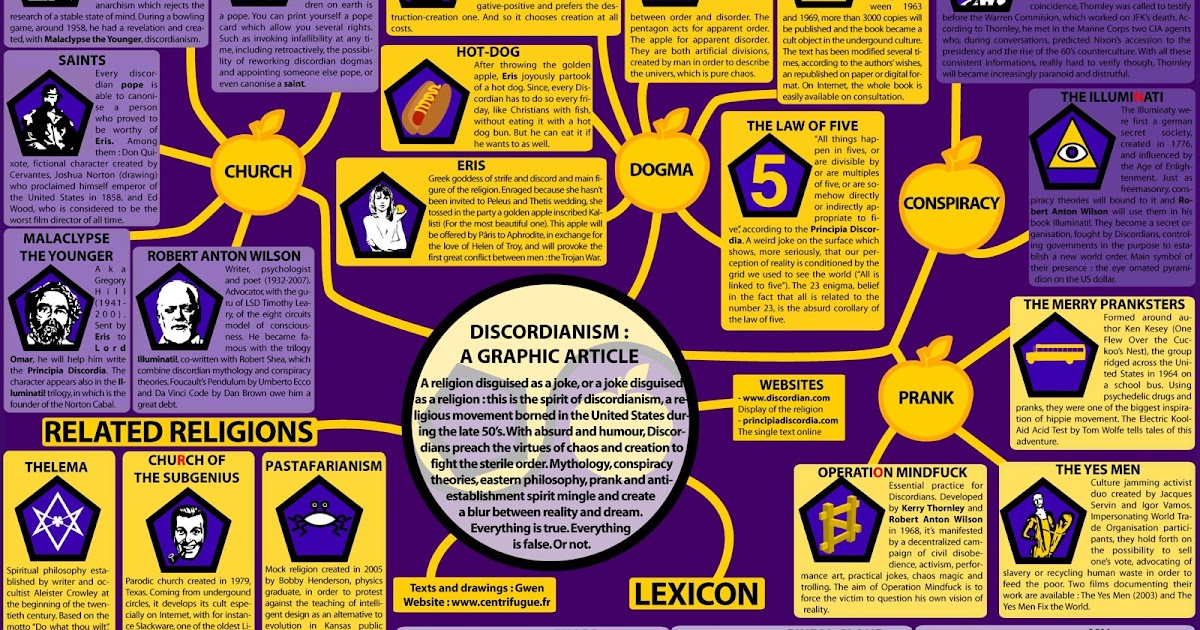

QAnon: The excitement of living in ‘fiction’

QAnon, an internet conspiracy theory, has recently captured a large segment of the public’s attention.

It might be a strong indicator of another possible reason underneath some people’s tendency to follow conspiracy theories: the thrill of being the one who knows the secret.

QAnon has become so mainstream you may know at least one believer.

Followers of this conspiracy theory believe that an anonymous government insider, known as “Q,” often drops mysterious clues and riddles to expose the “deep state” apparatus.

According to QAnon believers, these clues range from the color of the lights the White House uses on a specific date to coded messages posted in internet forums.

For QAnon followers, former President Donald Trump is a secret agent fighting to save the world.

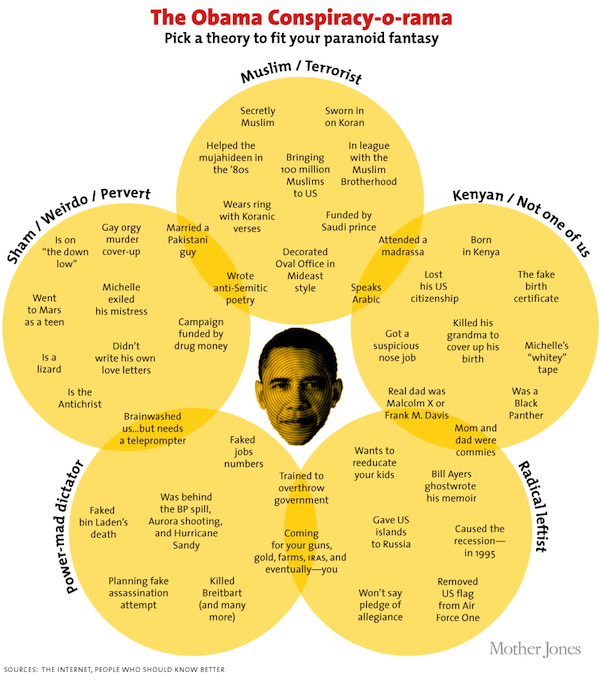

Who is he fighting against? A satanic cult of cannibals, pedophiles, and sex traffickers, led by Democratic politicians, such as Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama.

Why is QAnon so popular?

For some people, learning more about QAnon might just be a matter of curiosity.

For followers, QAnon might be convincing because its theories often play on:

- people’s fears

- the need to feel one is an empathetic person (e.g., saving the children)

- a natural thrill to solve mysteries

- a desire to be part of a like-minded group

- an explanation and a possible hopeful future for things not going “your way” right now

Also, QAnon might offer the thrill of a game.

Yes. The constant search for secret clues in mysterious places might give you the dopamine rush of “unlocking levels” in a video game.

In fact, when Berkowitz saw what QAnon was all about, he immediately recognized Q’s tactics.

Berkowitz has vast experience creating stories and games that begin on a computer and move to the real world. To him, QAnon has a very “game-like feel.”

“When I saw QAnon, I knew exactly what it was and what it was doing. I had seen it before. I had almost built it before,” he said in his column. “It was gaming’s evil twin. A game that plays people.”

When asked by Psych Central why he thought QAnon was so alluring, Berkowitz summed it up:

“QAnon explains the world in terms of vibrant fictions and gives its members ‘permission’ to believe in these fictions as facts.”

It’s like living in a movie or a game.

“It offers an accepting community of like-minded people and a worldview that puts members in the center of an exciting ‘reality’ that they have an active role in affecting,” Berkowitz tells Psych Central. “QAnon is alluring because it gives life the intensity and emotional vibrancy of living in a fiction.”

He adds: “It’s about being in a community of people all working together to help save the world and solve a mystery that is always just about to be revealed. ”

”

Are conspiracy theories dangerous? Are they harmful to the mental health of those who follow them?

It depends.

Believing in conspiracy theories can make a person who is already untrusting and suspicious even more so. But that’s not always the case.

It might be that for some people, firmly believing in one conspiracy theory might make them prone to believing in another one after that, and so on. It might also lead them to disregard real evidence to find one where none exists.

Some unproven theories can appear relatively harmless and even fun. But conspiracy theories, like QAnon, can lead people to actions that may harm themselves and others.

Some of these elaborate conspiracy theories could also promote distrust in institutions like the government or events like climate change, although other factors could also lead to this.

While not everyone is prone to believing conspiracy theories, many people are or can become prone to believing them.

We’ve discussed some possible reasons why people believe conspiracy theories.

So, what do you do if you tend to believe them?

- Fact check. Who is posting this information? Is the source a reputable one? Do all reputable sources show the same data and draw the same conclusions? Is there video evidence?

- Practice healthy skepticism. Taking everything with a grain of salt can actually help you process information differently.

- Critical thinking. Develop your critical thinking skills by questioning all the information you get and its sources. Draw your own conclusions.

- Diversify your network. Hang out with people of all beliefs, religions, races, and political parties. We can all learn something from each other.

- Open your mind. Be open to other points of view and consider alternative explanations for events. Being exposed to other people’s experiences can provide you with information you haven’t had the chance to access yourself.

There are many popular conspiracy theories. Some have been going around for years, and others have just recently surfaced.

Some have been going around for years, and others have just recently surfaced.

One of the big ones of 2020 — and there were quite a few — is the idea that COVID-19 was a hoax.

People who believe in the COVID-19 hoax theory are convinced the coronavirus never existed, and that the illusion of a pandemic was created to damage former President Trump politically.

Despite having a new president in the White House and the more than 586,000 deaths to date in the United States alone, some people are still firm believers in this conspiracy theory.

This isn’t the only COVID-19-related conspiracy theory.

Others include:

- Hydroxychloroquine, an antimalarial drug, is a cure-all drug for the coronavirus.

- COVID-19 vaccines plant a tracking chip in your body.

- Certain flu vaccines carry the coronavirus instead.

- Wearing a mask increases your chances of getting COVID-19.

All false claims.

Other popular conspiracy theories include:

- The 1969 moon landing was fake and recorded in a Hollywood studio.

- Barack Obama wasn’t born in the United States and may secretly be Muslim.

- The chemtrail conspiracy theory claims that the water condensation trails (contrails) emitted from aircraft are actually a toxic concoction of chemicals released by the government for nefarious purposes.

- “Lizard people” are running the world.

- The Disney movie title “Frozen” was purposefully named to cover up internet searches for claims that said Walt Disney’ was cryogenically frozen to be reanimated sometime in the future.

- The “SpongeBob SquarePants” TV show characters are based on the seven deadly sins.

Why do people believe in conspiracy theories? There might actually be a few psychological reasons that go from a need to control events that cause anxiety to having schizotypy tendencies.

Even if some theories seem rather harmless, others can affect the way people function in the world and respond to other people and events.

This is why it’s important to always double-check your sources and practice critical thinking.

Why do conspiracy theories attract people?

During the pandemic, many conspiracy theories have been linked to the name of Bill Gates. In the photo: a demonstration in Berlin. Copyright 2020 The Associated Press. All Rights ReservedAccording to a study by the University of Basel, approximately 30% of respondents in Germany and German-speaking Switzerland believe at least to some extent in one or another conspiracy theory related to the coronavirus pandemic. Why is it so, and even in our time of total availability of any information? We turned to a professor of social psychology for clarification. nine0003 This content was published on May 03, 2021 - 07:00

Igor Petrov prepared the original Russian version of the material.

Coronavirus was created in a laboratory by the world government in order to put everyone in the world under its control. No, you do not understand anything, the virus does not exist at all. The real motive behind the lockdown is to stop massive immigration from the global South to the global North and implement a mass human surveillance system along the way. Yes, it's all bullshit! It is clear that it was Bill Gates who created the virus in order to reduce the population of the planet in alliance with the reptilians who have long ruled over humanity. nine0003

No, you do not understand anything, the virus does not exist at all. The real motive behind the lockdown is to stop massive immigration from the global South to the global North and implement a mass human surveillance system along the way. Yes, it's all bullshit! It is clear that it was Bill Gates who created the virus in order to reduce the population of the planet in alliance with the reptilians who have long ruled over humanity. nine0003

Approximately 10% of respondents strongly believe in at least one of the conspiracy theories just listed. These are the results of the surveyExternal link , which was attended by approximately 1,600 people from Germany and German-speaking Switzerland. The survey was conducted by a team of experts from the University of Basel led by Sarah Kuhn and Thea Zander-Schellenberg. The survey also showed that another 20% of respondents support one of these theories at least "to some extent", 70% of respondents do not believe in any of these theories. nine0003

nine0003

“Not surprising,” says Pascal Wagner-Egger ( Pascal Wagner-EggerExternal link ), a professor at the University of Fribourg (Switzerland) who studies conspiracy theories as a social psychology phenomenon. Similar polls conducted at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020 showed approximately the same percentages: 10% of respondents are convinced of the truth of at least one of the similar theories, and 20% believe in them "to some extent." Moreover, even before the start of the pandemic, all sociological studies of conspiracy theories showed approximately the same, if not higher, numbers. nine0003

Show more

Show more

“After a year of the pandemic, I'm even surprised that the percentage has not increased. Perhaps this is good news for us,” says Pascal Wagner-Egger, who nevertheless warns against overestimating this kind of data. No matter how interesting and tempting these figures are from a journalistic and political point of view, it would not be too responsible to simply extrapolate these proportions to the whole of society as a whole. Sociology as a science does not trust such surveys too much, because when someone answers “I believe”, you first need to understand what the respondent means. nine0003

Sociology as a science does not trust such surveys too much, because when someone answers “I believe”, you first need to understand what the respondent means. nine0003

How dangerous are conspiracy theories?

But even without scientific research, one only needs to look at social networks to understand how widespread this phenomenon is. When it comes to news related to the coronavirus, it's hard not to find at least one commentary based on at least one of these crazy theories. And it's not nearly as harmless as it might seem. “In the course of our research, we found that these kinds of beliefs often go hand in hand with generally anti-scientific attitudes towards reality, correlating, for example, with a negative attitude towards vaccination. During a pandemic, of course, this becomes a particular problem, because we all want to end the pandemic as soon as possible, and this can only be done with the help of vaccinations,” says P. Wagner-Egger. nine0003

Show more

The sphere of politics and democracy in general also suffers. If you think that the majority of the media lie, and not only those media that I personally trust, if politicians are bought and experts are corrupt, then this is a sign of a systemic loss of trust in the institutions and structures of society, which is both a cause and a consequence of strengthening really extremist forces in society, both extreme right and extreme left, striving not just, say, to overcome the “climate crisis” or release the conditional “Assange”, but immediately “dismantle the system”, destroy democracy with its own, democracy, tools. The same thing happens with the so-called "coronaskeptics". nine0003

If you think that the majority of the media lie, and not only those media that I personally trust, if politicians are bought and experts are corrupt, then this is a sign of a systemic loss of trust in the institutions and structures of society, which is both a cause and a consequence of strengthening really extremist forces in society, both extreme right and extreme left, striving not just, say, to overcome the “climate crisis” or release the conditional “Assange”, but immediately “dismantle the system”, destroy democracy with its own, democracy, tools. The same thing happens with the so-called "coronaskeptics". nine0003

Online defamation and slander

At this point, it is important to be clear: we are talking about how dangerous belief in conspiracy theory is, but both history and current events show that conspiracies of various kinds do exist in reality. A lot of things in society really "go wrong." Switzerland, for example, cannot finally establish a normal vaccination process. An ammunition depot blows up in the Czech Republic. But is it possible on this basis to conclude that any event is the result of a "conspiracy of the world government"? If you believe in "Occam's razor", then, probably, such conclusions should not be drawn. nine0003

An ammunition depot blows up in the Czech Republic. But is it possible on this basis to conclude that any event is the result of a "conspiracy of the world government"? If you believe in "Occam's razor", then, probably, such conclusions should not be drawn. nine0003

Show more

Moreover, it is worth taking this or that theory and considering it more carefully, as it will most likely turn out that there are simply no rational proofs here. But on the other hand, such theories help, without particularly studying anything and without reading any texts “where there are a lot of letters”, not only quickly create a scientific picture of the world, but also try to earn political capital on this. “Such coronaskeptic beliefs lead nowhere and are counterproductive, even if you are truly sincerely opposed to the system. Why? nine0003 Pascal Wagner-Egger is Professor of Social Psychology and Statistics at the University of Friborg (Switzerland). He has been studying conspiracy theories for twenty years. His first book on the subject will be published in French by PUG editions on May 6, 2021 under the title Psychologie des croyances aux théories du complot. University of Friburgo

He has been studying conspiracy theories for twenty years. His first book on the subject will be published in French by PUG editions on May 6, 2021 under the title Psychologie des croyances aux théories du complot. University of Friburgo

“Because such beliefs are usually not based on any evidence, and therefore here, as nowhere else, the risk is that you will adhere to false positions and beliefs,” says P. Wagner-Egger. In other words, suspicions of a conspiracy may turn out to be true (even if most of these suspicions turn out to be, as a rule, false assumptions), but specific accusations of conspiracy without presenting specific evidence are already slander, that is, a crime. nine0003

“If a real conspiracy is revealed somewhere, it almost always happens thanks to the work of law enforcement officers or investigative journalists, and certainly not thanks to people who sit in their “information bubbles” in networks and believe in all possible and conceivable conspiracies ”, says P. Wagner-Egger.

Wagner-Egger.

Where do conspiracy theories come from?

Despite the fact that the phenomenon of "conspiracy theory" today is at the very center of public attention, it is not something completely new. “Conspiracy theories began to appear immediately after human society moved to a settled life, and immediately after stable structures and institutions appeared in these societies and the struggle for power began,” explains P. Wagner-Egger. nine0003

In his opinion, there are three factors that explain the current success of all these unsubstantiated conspiracy theories. The first is the socio-political factor, already mentioned earlier. People who are hostile to public institutions and to the existing "system" tend to justify their actions with conspiracy theories.

Our manual: "How to talk to a conspiracy theorist"?

How should social media comments that spread conspiracy theories be treated? Pascal Wagner-Egger regularly communicates with such "theorists" on social networks, and he admits that it is usually simply impossible to convince someone. “It's like arguing with a religious fanatic. If you tell him that dinosaur fossils exist in defiance of creationism, he will reply that the devil put them there to make us believe that everything in the Bible is a lie. The consciousness of a radical person cannot be changed,” he says. nine0003

“It's like arguing with a religious fanatic. If you tell him that dinosaur fossils exist in defiance of creationism, he will reply that the devil put them there to make us believe that everything in the Bible is a lie. The consciousness of a radical person cannot be changed,” he says. nine0003

Nevertheless, P. Wagner-Egger continues to engage in a dialogue with these people on the Internet, pointing out inconsistencies in their reasoning and warning them that serious allegations without evidence can become the subject of criminal proceedings. And even if the opinion of such an interlocutor is usually impossible to change, still P. Wagner-Egger does not consider the time spent talking with them lost. Why? For two reasons. Firstly, some “vague doubts” can be sown in the subconscious of conspiracy theorists with their arguments. Secondly, debates affect those who do not participate in them, but look at them from the side. Such people, as a rule, have not yet decided which camp to belong to and they are looking for the best arguments in favor of one side or another. nine0003

nine0003

“People who tend to take a moderate position tend to react negatively to conspiracy theories,” says P. Wagner-Egger. The situation becomes noticeably more complicated if such a supporter of the "conspiracy theory" is someone close, for example, a family member or acquaintance. Sometimes the split line separates even spouses and parents with children on opposite sides of the barricades. In this case, you can use the technique of " epistemologicalExternal link interview", a kind of Socratic dialogue. The art here is to lead the discussion without expressing your own opinion. nine0003

“You do not state your own position, but you ask the interlocutor questions, forcing him to justify his position. Very often, these people themselves admit in the end that their beliefs have a rather fragile basis. Epistemological interview is often used in humanistic psychology, it is a method that allows you to treat another person with respect, while creating a positive atmosphere, in contrast to social networks, where those who are only looking for something to “offend” dominate - summarizes P. Wagner-Egger. nine0003

Wagner-Egger. nine0003

End of insertion

Such beliefs are sometimes fueled by real social imbalances and real problems (the climate is indeed changing, and the problem of racism is real). It has already become a commonplace the thesis that the higher the degree of social inequality in society, the more prepared and fertilized the ground for the flourishing of the most incredible conspiracy theories, often combined with radical and extremist dreams of “revenge”, characteristic of the supposedly “infringed or "discriminated" social groups. “Although poverty in the world has been noticeably reduced, it still and by no means disappeared anywhere, and with the pandemic, its scale even began to grow again. In addition, the gap between the richest and the poorest is growing again. And this also feeds the so-called “conspiracy discourse,” says P. Wagner-Egger. nine0003

Show more

The second factor is psychological in nature. Despite all the technological advances, we humans as a species tend to have a naive, anti-scientific mindset, especially in fearful situations such as a terrorist threat or a pandemic. P. Wagner-Egger gives the example of a man walking alone through the forest at night: if he hears some kind of noise, then he is inclined to immediately think that it is a predator or someone who wants to harm him. Such thinking was "hardwired" into the matrix of human consciousness in the course of evolution. Our most paranoid ancestors survived precisely because they preferred to react in case of a possible danger and not rely on chance! We inherited this character trait as a genetic gift, for which we should actually be thankful. nine0003

Despite all the technological advances, we humans as a species tend to have a naive, anti-scientific mindset, especially in fearful situations such as a terrorist threat or a pandemic. P. Wagner-Egger gives the example of a man walking alone through the forest at night: if he hears some kind of noise, then he is inclined to immediately think that it is a predator or someone who wants to harm him. Such thinking was "hardwired" into the matrix of human consciousness in the course of evolution. Our most paranoid ancestors survived precisely because they preferred to react in case of a possible danger and not rely on chance! We inherited this character trait as a genetic gift, for which we should actually be thankful. nine0003

“Cognitive distortions due to evolution fuel the belief not only in conspiracies, but also in the paranormal. Seeing ghosts or seeing some hidden motives in people's actions - all this was relevant a hundred and two hundred years ago, ”explains P. Wagner-Egger. The third factor is the Internet, in which conspiracy theories can not only spread with great speed, but also remain forever in the “global cache”, so to speak. Does the Internet forget anything? Sometimes this property is very useful, and sometimes not. As soon as you start searching for information about a particular conspiracy theory, you can very easily and quickly stumble upon materials that seem to have already been deleted from everywhere. But they still remain, whereas without the Internet they would be firmly forgotten. nine0003

The third factor is the Internet, in which conspiracy theories can not only spread with great speed, but also remain forever in the “global cache”, so to speak. Does the Internet forget anything? Sometimes this property is very useful, and sometimes not. As soon as you start searching for information about a particular conspiracy theory, you can very easily and quickly stumble upon materials that seem to have already been deleted from everywhere. But they still remain, whereas without the Internet they would be firmly forgotten. nine0003

Return to normal life?

How to deal with conspiracy theories? P. Wagner-Egger advises, in a Marxist way, “to start from the root causes and try to reduce the degree of social inequality, strengthen the fight against corruption, ensure the availability of impartial, competent and enlightened professional journalism, achieve a real implementation of the principle of separation of powers, when each of the branches of power (legislative, executive and judicial) is independent and independent in the exercise of its powers”. It is also desirable to have feedback between society and the authorities in the form of elections, the change of power, and even, as in Switzerland, in the format of direct democracy. nine0003

It is also desirable to have feedback between society and the authorities in the form of elections, the change of power, and even, as in Switzerland, in the format of direct democracy. nine0003

Show more

These are all important things in themselves, but they are also very useful and effective methods of dealing with such a phenomenon as conspiracy theory. From the point of view of mentality, according to P. Wagner-Egger, the most effective way to develop immunity to conspiracy theories is modern education and educational activities: this is the only way to teach young people, and not only people, to think critically, not to believe everything at once and check the information . Terribly interesting is everything that is unknown, who would argue! But without concrete evidence, trusting incomprehensible "British scientists", we run the risk of falling into an endless dead end of obscurantism and lies. nine0003

The end of the pandemic will of course lead to fewer conspiracy theories on social media, but "fake news" and government propaganda, including foreign propaganda, will remain a problem for a very long time, if not forever. Social networks, being private companies, are already taking some kind of countermeasures, blocking the profiles of people who specifically distribute problematic content. “Censorship was and remains a negative phenomenon, but in this case I don’t think that we can talk about real censorship here, rather it is about media hygiene,” says P. Wagner-Egger. nine0003

Social networks, being private companies, are already taking some kind of countermeasures, blocking the profiles of people who specifically distribute problematic content. “Censorship was and remains a negative phenomenon, but in this case I don’t think that we can talk about real censorship here, rather it is about media hygiene,” says P. Wagner-Egger. nine0003

Show more

Social networks are private companies, in addition, blocked people can very quickly move to other networks or create new accounts. “It is therefore about banishing the ideas of conspiracy theories from public discourse and returning them to where they were before the advent of the Internet, that is, in pamphlets and books of various kinds of esoteric sects. That would be a return to normal life." But how real is this and isn’t the scientist naive, because, as you know, “minced meat cannot be scrolled back”, and social networks will remain with us forever? nine0003

In accordance with JTI

standards Show more: JTI certificate for SWI swissinfo. ch

ch

Show more

How to argue with conspiracy theorists

How to argue with conspiracy theorists? Don't yell at them and don't laugh at them.

Coronavirus vaccine will be available soon. But conspiracy theorists will not want to be vaccinated and will dissuade others. How to argue with them? First, don't yell. Secondly, do not question the mental abilities of the interlocutor. Third, look for common ground. What else needs to be done? Psychologist explains Jovan Byford in his article on the CNN website.

The prospect of a COVID-19 vaccine soon brings attention to the issue of anti-vaccination sentiment. According to a recent survey, one in six Britons will opt out of a COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available. Vaccination uncertainty is a complex problem with many causes, and the numerous conspiracy theories about the coronavirus are not helping to overcome it.

Fight against conspiracy theories about COVID-19 will be fought on several fronts. Controlling the spread of disinformation requires a broad public health campaign and the involvement of social media companies. According to Jovan Byford, Senior Lecturer in Psychology at the Open University, everyone has a role to play in this fight. A conspiracy theorist who has studied the subject for over two decades has made six recommendations for dealing with people who have succumbed to conspiracy ideas about the COVID-19 pandemic. Perhaps you can change their minds and thus serve science. nine0003

1. Realize the scope of the task

Talking to people who support conspiracy theories can be difficult. Simply presenting the evidence or pointing out logical inconsistencies in the conspirators' arguments is rarely enough. Conspiracy theories are, by definition, irrefutable.

The lack of evidence of a conspiracy or clear evidence against its existence is taken by believers as confirmation of the cunning of those behind the conspiracy and their ability to deceive the public. So arm yourself with patience and be prepared to fail. nine0003

So arm yourself with patience and be prepared to fail. nine0003

2. Recognize the emotional aspect

Conspiracy theories captivate not so much by the strength of the argument, but by the intensity of the passions they arouse. The foundation for them is feelings of resentment, indignation and disappointment in the world around. Conspiracy theories are stories about good and evil and what is true. Therefore, they have a strong emotional dimension. In the process of a dispute, you can flare up and break into a scream. It is important to prevent this. Be ready to de-escalate the conflict situation and continue the dialogue, without necessarily retreating from your position. nine0003

3. Find out what the other person believes

Before trying to convince someone, find out the nature and content of their beliefs. When it comes to conspiracy theories, the world is not strictly divided into "believers" and "skeptics" - there are many stages in between.

A minority of convinced "believers" view conspiracy theories as indestructible truth and are especially resistant to persuasion. Many others may not consider themselves "believers" but are willing to admit that conspiracy theorists might know something and at least ask the right questions. Establishing the exact nature and extent of the other person's conviction will allow you to better tailor your response. nine0003

Many others may not consider themselves "believers" but are willing to admit that conspiracy theorists might know something and at least ask the right questions. Establishing the exact nature and extent of the other person's conviction will allow you to better tailor your response. nine0003

Try to find out what specific conspiracy theory they support. Do they think 5G or Bill Gates is behind the coronavirus? Or both? What videos or websites did they watch? Once you figure this out, gather as much supporting evidence as you can from reliable sources, including numerous independent fact-checking sites.

Knowing the bottom line will help you focus the conversation on the very essence of the claims. Never question someone's intelligence or moral values as this is the quickest way to end a conversation. nine0003

4. Find common ground

One of the main problems with conspiracy theories is that they are not limited to fanatics in foil hats or political extremists. In times of crisis and uncertainty, they can pollute the worldview of even otherwise intelligent people.

Conspiracy theories make reality seem less chaotic and address broader, often well-founded fears about the world's problems, such as the concentration of financial and political power, mass surveillance, inequality, or lack of political transparency. So when talking about conspiracy theories, start by acknowledging these broader concerns and reduce the conversation to the question of whether conspiracy theories can provide an adequate or meaningful answer. nine0003