Sharon salzberg website

About - Sharon Salzberg

Navigation

Sharon's latest book REAL CHANGE is now available to pre-order in paperback coming out 11/30/21

a very young Sharon (far right) in India in 1972

Born in New York City in 1952, Sharon Salzberg experienced a childhood involving considerable loss and turmoil. An early realization of the power of meditation to overcome personal suffering determined her life direction. Her teaching and writing now communicates that power to a worldwide audience of practitioners. She offers non-sectarian retreat and study opportunities for participants from widely diverse backgrounds. Sharon first encountered Buddhism in 1969, in an Asian philosophy course at the State University of New York, Buffalo. The course sparked an interest that, in 1970, took her to India, for an independent study program. Sharon traveled motivated by “an intuition that the methods of meditation would bring me some clarity and peace.” In 1971, in Bodh Gaya, India, Sharon attended her first intensive meditation course.

She spent the next years engaged in intensive study with highly respected meditation teachers. She returned to America in 1974 and began teaching vipassana (insight) meditation. In 1976, she established, together with Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfield, the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) in Barre, Massachusetts, which now ranks as one of the most prominent and active meditation centers in the Western world. Sharon and Joseph Goldstein expanded their vision in 1989 by co-founding the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies (BCBS). In 1998, they initiated the Forest Refuge, a long-term retreat center secluded in a wooded area on IMS property. Today she leads teaches a variety of offerings around the globe. Sharon resides in Barre, Massachusetts, and New York City. Sharon has also emerged as a featured speaker and teacher at a wide variety of events. She served as a panelist with the Dalai Lama and leading scientists at the 2005 Mind and Life Investigating the Mind Conference in Washington, DC.

She also coordinated the meditation faculty for the 2005 Mind and Life Summer Institute, an intensive five-day meeting to advance research on the intersection of meditation and the cognitive and behavioral sciences. At the 2005 Sacred Circles Conference at the Washington National Cathedral, Sharon served as a keynote speaker. She has addressed audiences at the State of the World Forum, the Peacemakers Conference (sharing a plenary panel with Nobel Laureates His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Jose Ramos Horta) and has delivered keynotes at Tricycle’s Buddhism in America Conference, as well as Yoga Journal, Kripalu and Omega conferences. She was selected to attend the Gethsemani encounter, a dialogue on spiritual life between Buddhist and Christian leaders that included His Holiness the Dalai Lama. The written word is central to Sharon Salzberg’s teaching and studies. She is the author of eleven books including Lovingkindness, the NY Times best seller Real Happiness, and her 2017 work, Real Love: The Art of Mindful Connection

and her newest book, Real Change: Mindfulness To Heal Ourselves and the World, coming in September of 2020 from Flatiron Books.

She also coordinated the meditation faculty for the 2005 Mind and Life Summer Institute, an intensive five-day meeting to advance research on the intersection of meditation and the cognitive and behavioral sciences. At the 2005 Sacred Circles Conference at the Washington National Cathedral, Sharon served as a keynote speaker. She has addressed audiences at the State of the World Forum, the Peacemakers Conference (sharing a plenary panel with Nobel Laureates His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Jose Ramos Horta) and has delivered keynotes at Tricycle’s Buddhism in America Conference, as well as Yoga Journal, Kripalu and Omega conferences. She was selected to attend the Gethsemani encounter, a dialogue on spiritual life between Buddhist and Christian leaders that included His Holiness the Dalai Lama. The written word is central to Sharon Salzberg’s teaching and studies. She is the author of eleven books including Lovingkindness, the NY Times best seller Real Happiness, and her 2017 work, Real Love: The Art of Mindful Connection

and her newest book, Real Change: Mindfulness To Heal Ourselves and the World, coming in September of 2020 from Flatiron Books. In her early Buddhist studies at the University of Buffalo, she discovered Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s book, Meditation in Action. She later heard him speak at a nearby school: he was the first practicing Buddhist she encountered. While studying in India, Shunryu Suzuki’s book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind profoundly influenced the direction of her meditation practice. Sharon’s writing can be found on Medium, On Being, the Maria Shriver blog, and Huffington Post and she was a contributing editor of Oprah’s O Magazine for several years. She has appeared in Time Magazine, Yoga Journal, msnbc.com, Tricycle, Real Simple, Body & Soul, Mirabella, Good Housekeeping, Self, Buddhadharma, More and Shambhala Sun, as well as on a variety of radio programs. Various anthologies on spirituality have featured Sharon Salzberg and her work, including Meetings with Remarkable Women, Gifts of the Spirit, A Complete Guide to Buddhist America, Handbook of the Heart, The Best Guide to Meditation, From the Ashes—A Spiritual Response to the Attack on America, and How to Stop the Next War Now: Effective Responses to Violence and Terrorism.

In her early Buddhist studies at the University of Buffalo, she discovered Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s book, Meditation in Action. She later heard him speak at a nearby school: he was the first practicing Buddhist she encountered. While studying in India, Shunryu Suzuki’s book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind profoundly influenced the direction of her meditation practice. Sharon’s writing can be found on Medium, On Being, the Maria Shriver blog, and Huffington Post and she was a contributing editor of Oprah’s O Magazine for several years. She has appeared in Time Magazine, Yoga Journal, msnbc.com, Tricycle, Real Simple, Body & Soul, Mirabella, Good Housekeeping, Self, Buddhadharma, More and Shambhala Sun, as well as on a variety of radio programs. Various anthologies on spirituality have featured Sharon Salzberg and her work, including Meetings with Remarkable Women, Gifts of the Spirit, A Complete Guide to Buddhist America, Handbook of the Heart, The Best Guide to Meditation, From the Ashes—A Spiritual Response to the Attack on America, and How to Stop the Next War Now: Effective Responses to Violence and Terrorism. Sharon is the host of her own podcast, The Metta Hour, featuring 100+ interviews with the top leaders and voices in the meditation and mindfulness movement.

Sharon is the host of her own podcast, The Metta Hour, featuring 100+ interviews with the top leaders and voices in the meditation and mindfulness movement.

How I found kindness as my compass

SHARON SALZBERG: Joseph seems to radiate equanimity and balance. Of course the difference between Joseph and me is that he’s been meditating for four years, and I’ve been meditating for maybe four days.

So when Joseph says “Yeah, it was a hard morning. But that’s okay, ” it isn’t the voice of apathy. It’s the voice of experience. It’s saying, “Some difficulty is normal.” And this is exactly what I’m here to learn. I’m just so desperate to figure it out fast — to beat down my sorrow. And he’s like, “Give yourself a break.”

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: By the time Sharon Salzberg is 16 years old, she knows the people around her don’t admit to suffering, much less talk about it. A year later, she makes a life-changing decision to travel alone to India to study meditation. It doesn’t all go as expected. Through the journey’s disappointments, discomforts, and surprise lessons, she finds an unexpected friend: herself. In today’s Meditative Story, Sharon — who I must confess to being a hero of mine — talks about how being kind, especially to herself, became her biggest mountain to climb.

It doesn’t all go as expected. Through the journey’s disappointments, discomforts, and surprise lessons, she finds an unexpected friend: herself. In today’s Meditative Story, Sharon — who I must confess to being a hero of mine — talks about how being kind, especially to herself, became her biggest mountain to climb.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories, breathtaking music, and mindfulness prompts so that we may see our lives reflected back to us in other people’s stories. And that can lead to improvements in our own inner lives.

From WaitWhat, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

SALZBERG: When I board the train from New Delhi to Gaya, I have no idea how to find my seat. Families crowd into the cars and peple keep trying to sell me chai. It’s really hot. I finally find my seat: a wooden bench in third class where I’ll spend the next 17 hours.

It’s my first time in India, and really — my first time almost anywhere. It’s 1970; I’m 18 years old. And before this trip, the longest train I’ve ever taken was the subway from one part of Manhattan to another.

The old man next to me keeps trying to start a conversation about philosophy. He has a long white beard and large, intense eyes.

“What’s your purpose?” he asks me.

I have no idea what to say. I mumble something and look out the window. Yes, I’ve come to India to study, but I’m not really interested in philosophy. It’s the how-to I want. I’ve heard about how powerful meditation is, and I’m looking for instruction. I’m hoping it might be like paint-by-numbers: “Do this and then this” — and you’ll have the keys to releasing unhappiness.

So far, though, I’m not having much luck. I’ve been in India for several weeks and nothing is working. I thought there’d be teachers on every corner who’d teach me meditation. There are not. I feel the pressure of time passing. Why can’t I find someone to teach me?

Why can’t I find someone to teach me?

So now I’m riding this train with a few other students I’ve met along the way. We’re traveling together from New Delhi to Bodh Gaya for an intensive 10-day retreat we heard about.

As the train pulls into Gaya the sun is setting, and my back hurts from being on that wooden plank all night and day. We pour out of the train into the station. People crowd around us. Women wear saris the color of eggplant and persimmon. Men in loose pants steer bicycles through the station. The station smells like smoke and tea and ripe fruit. It’s a press of humanity — and I’m not at all sure that this is a good idea. How did I get here?

A year earlier, I’m sitting in a college classroom in Buffalo, New York. Outside, on the university green, you can hear the chants of students protesting the Vietnam war. Inside, the girls wear flowered skirts and the boys have long hair and ripped jeans. There’s maybe 30 of us. We’re really a bunch of hippies.

It’s my sophomore year, and I’m in an Asian philosophy class. I’m taking it by accident, really. It fills my philosophy requirement. It fits my schedule.

I’m taking it by accident, really. It fills my philosophy requirement. It fits my schedule.

Much of the course focuses on the tenets of Buddhism. The professor paces at the front of the room and tells us: “The Buddha taught that suffering is natural and universal.”

He says this as if it’s the most obvious thing in the world. I look around; the rest of the class seem unfazed. But I’m suddenly very attentive. I have not been holding the idea that suffering is universal. I tend to think it’s just me.

My childhood is difficult. My mother dies when I’m 9. By then my father is gone too. He has a breakdown. He’s in psychiatric hospitals. So I’m left in the care of grandparents who don’t really tell me what’s going on. My world is full of secrets. I’m sure every other family is perfect, like the ones on TV. I feel deficient. I turn down entrance to a special high school because I’m too afraid to go. I feel alone, afraid, frozen. I’m always waiting for the other person to take action, to get the prize.

So when I hear the professor say that suffering is universal — that it’s even a natural part of life — it wakes me up. It starts to change the way I see myself. I begin to wonder what’s going on behind the closed doors in all those other houses. For the first time, a new thought crosses my mind: I might be normal.

GUNATILLAKE: Being normal. How do you relate to that? Is there a sense of aspiration here like Sharon? Or is there something else?

SALZBERG: The teacher introduces the idea of meditation. He explains that there are practical things you can learn to do with your mind that will help you be happier. I’m intrigued. But it’s 1970 in Buffalo, New York. And there isn’t anywhere I can find for me to learn more.

My curiosity about meditation is powerful enough that it propels me to do something I’ve never done before: I make a bold move. I propose an independent study project in India — one year abroad where I’ll learn to meditate. Four days before I’m set to leave, I learn that a Buddhist teacher is coming to town.

It’s Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and I go to hear him lecture. At the end, he asks for questions. I write mine down on a piece of paper, fold it up into a triangle, and hand it in. There’s this big pile of questions in front of him, and he pulls out my piece of paper. It asks: I’m about to leave for India. Where should I go to study Buddhist meditation? I’m hoping for a recommendation.

He glances at the paper and looks up. He’s quiet for a few moments. Then he says, “Perhaps you’d best follow the pretense of accident.” The pretense of accident. What does that even mean? I guess it means mostly: He’s not giving me any addresses. And also, he doesn’t want it to be easy.

I fly from New York to London and take the train — the Orient Express — to Istanbul to travel overland to India.

I travel first to Daramshala because I hear the Dalai Lama lives there, and I know he’s a Buddhist. But I don’t find an actual meditation class happening regularly there. In a Tibetan restaurant, I overhear a conversation about a yoga conference in New Delhi. So I think: “Oh, I’ll go there. And I’ll find my teacher.” The conference is terrible. But one of the speakers is an American named Dan Goleman. Years later, he’ll popularize the term “Emotional Intelligence.” But right now, he’s a grad student in psychology, learning what he can in India. Dan mentions that he’s headed to a place called Bodh Gaya for an intensive 10-day meditation retreat. Bodhgaya is the very site where the Buddha reached enlightenment under the Bodi tree. Maybe this is the “pretense of accident” I’m looking for. I take Dan’s advice and buy the train ticket to Gaya.

So I think: “Oh, I’ll go there. And I’ll find my teacher.” The conference is terrible. But one of the speakers is an American named Dan Goleman. Years later, he’ll popularize the term “Emotional Intelligence.” But right now, he’s a grad student in psychology, learning what he can in India. Dan mentions that he’s headed to a place called Bodh Gaya for an intensive 10-day meditation retreat. Bodhgaya is the very site where the Buddha reached enlightenment under the Bodi tree. Maybe this is the “pretense of accident” I’m looking for. I take Dan’s advice and buy the train ticket to Gaya.

The streets of India can’t be more different from my own experience growing up in the U.S. In my family, we never say a word like “cancer” out loud. We whisper it. But here, life just spills out before us, joys and sorrows both. Here, I see people in the station who are terribly poor, who are terribly sick. And they’re not hiding anything from anyone. I’m frightened. But I also feel the rumblings of something different. The thrill of being somewhere with no apparent secrets — where there’s permission to acknowledge suffering.

The thrill of being somewhere with no apparent secrets — where there’s permission to acknowledge suffering.

We walk out of town along a dry river bed and arrive at the gate marking the Burmese Temple. Shuffling through the gate with our backpacks, we find a garden growing banana plants as tall as a house. There’s a two-story, brick building with a large veranda, and the place is already crowded with students. The men go up to the roof where they sleep under a large tent. The women, we unroll our sleeping bags in the hallways where we’ll sleep for the next week. There are no rugs. Eventually we hang up saris on clothes lines between us for a little privacy.

I’m new to meditation, but I know some of the people here are important — for example Ram Dass, the former Harvard professor who’s now a spiritual seeker. He’s only 39, but he seems old to me with his shiny, balding head and full graying beard.

Our first meditation session takes place in the temple library. Book shelves lean against most of the walls with baskets and boxes piled on top. The room is crowded — about 70 of us sitting on the floor in circles around the teacher, who sits cross-legged at the front. I sit way in the back on the bare wood floor, leaning against a bookcase.

The room is crowded — about 70 of us sitting on the floor in circles around the teacher, who sits cross-legged at the front. I sit way in the back on the bare wood floor, leaning against a bookcase.

Our teacher, Goenka, welcomes us in his opening talk. He says. “The Buddha did not teach Buddhism. The Buddha taught a way of life. And so everyone is welcome here. You don’t have to become a Buddhist.”

Then we start to meditate. And it’s so painful. I sit cross-legged on my rolled-up sleeping bag, and I’m incredibly uncomfortable. It feels like we sit for 6,000 years, but it’s just 45 minutes. By the end, I’m exhausted and hot, and my knees hurt. But I know, underneath that, this is where I need to be.

I think back to what Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche told me in Buffalo: “follow the pretense of accident.” I’ve followed a series of accidents here. An overheard conversation in a restaurant. A disappointing conference, yet with one speaker who changed my life. The only thing I can stay close to is my intention: I’m going to learn some way to be happier.

GUNATILLAKE: Have periods of your life ever felt like a series of accidents? Let’s remember these times and join Sharon in her reflection.

SALZBERG: A few days into the retreat, our teacher tells us: “This session, we’re going to sit with determination. We’re not going to move.” And I move within seconds. This is impossible for me. I’m doing it all wrong. I can’t concentrate. I’m so frustrated. I need this to work, to fix me. And I only have a few days left in the retreat to get it right. I actually say to myself, “The next time your mind wanders you should just bash your head against the wall.” I’m just so disappointed with myself.

Just then the lunch bell rings. I get in line, and someone behind me asks this other guy: “How was your morning?” An American voice replies in the calmest possible way:

“Oh I couldn’t focus at all in my meditation. But this afternoon I’ll probably be better.”

I’m horrified. I think, “What’s wrong with him? He’s so cavalier. ” I feel worried for him. Like, “Don’t you understand? You can become liberated if you take this seriously.” I spin around, full of judgment, to see this tall gangly American with short dark hair and an unshakable calm. And this is how I meet Joseph Goldstein.

” I feel worried for him. Like, “Don’t you understand? You can become liberated if you take this seriously.” I spin around, full of judgment, to see this tall gangly American with short dark hair and an unshakable calm. And this is how I meet Joseph Goldstein.

Joseph seems to radiate equanimity and balance. Of course the difference between Joseph and me is that he’s been meditating for four years, and I’ve been meditating for maybe four days. So when Joseph says “Yeah, it was a hard morning. But that’s okay,” it isn’t the voice of apathy. It’s the voice of experience. It’s saying, “Some difficulty is normal.” And this is exactly what I’m here to learn. I’m just so desperate to figure it out fast to beat down my sorrow. And he’s like, “Give yourself a break.”

I don’t know it at the time, but Joseph will become one of my dearest lifelong friends and collaborators. And it starts with these conversations in the lunch line and the hallways.

One morning during meditation, I feel a tide of anger rising inside me. It feels in my body like a rush of energy. This is the first time in my life I’ve been deeply introspective, so of course when I sit still and look inside, I unearth fear and anger. I don’t know yet that fear and anger are the same emotion in different forms. So it just consumes me. And then I get mad at myself for feeling angry. I think, “What kind of person meditates in this beautiful place and comes away angry? Everyone here is in rhapsody, they’re in bliss! And I’m in fury. What the hell is wrong with me?’”

It feels in my body like a rush of energy. This is the first time in my life I’ve been deeply introspective, so of course when I sit still and look inside, I unearth fear and anger. I don’t know yet that fear and anger are the same emotion in different forms. So it just consumes me. And then I get mad at myself for feeling angry. I think, “What kind of person meditates in this beautiful place and comes away angry? Everyone here is in rhapsody, they’re in bliss! And I’m in fury. What the hell is wrong with me?’”

After the meditation, I storm up to my teacher, Goenka, and say, “I never used to be an angry person before I started meditating!” — thereby laying blame exactly where I feel it belongs: on him. Clearly, it’s all his fault.

Goenka has this big head of thick gray hair and a round, soft, incredibly sweet face. But still I manage to scowl at him. And he looks at me, and he starts laughing. It’s not what I expect. But it doesn’t make me angrier. It just sort of lets the air out of my hot angry balloon. It makes me feel normal.

It makes me feel normal.

The laughter seems his way of saying, “Of course, you feel anger. It is part of the process. There’s nothing wrong with it. There’s nothing wrong with you. The question is: What do you do with that anger? How do you act?” I understand all of this, even though he doesn’t say it.

And I also understand that he’s telling me: ‘’Feeling the anger is good. It’s good progress.” Because now I can actually notice the emotion.

It will take a while before I learn that the skillful response to feeling anger is to feel it. And then even to take an interest in it. I don’t have to let it carry me into action that I may regret.

But I already feel the lesson that life is teaching me over and over again: We all face challenges. It’s how we become who we are. You don’t have to judge yourself all the time. Give yourself a break.

I stay in India for more than a year. I return to the U.S. feeling I have something precious feel I have a path. It’s not totally fulfilled. And I know I’ll mess up along the way. But I have a path, a north star to guide my life.

And I know I’ll mess up along the way. But I have a path, a north star to guide my life.

When I get back to the states, I finish college and go right back to India to continue studying. Within a couple of years — after returning to the U.S. again — Joseph and I start leading retreats.

Kindness toward ourselves becomes central to my teachings. But it’s still one of my biggest mountains to climb. In 1976, Joseph and I — along with Jack Kornfield — open our retreat center in Barre, Massachusetts. At this point, I’ve never received formal instruction in loving-kindness meditation, so I just decide to do it myself for a month before we start teaching. Every day for a week, I meditate to: “May I be happy. May I be healthy and safe. May my heart know peace.”

I basically feel nothing, but I just keep doing it.

One day, after a week, I’m in an upstairs bathroom at our retreat center. And I’m rushing. It’s this small bathroom, no windows and dingey white tile. It feels tight and enclosed. As I get ready, I whirl around, and I suddenly knock this big glass jar of bath salts onto the tile floor. The jar shatters and stuff goes everywhere. And in this moment, the thought that comes up in my mind is: “You’re really a klutz, but I love you.”

As I get ready, I whirl around, and I suddenly knock this big glass jar of bath salts onto the tile floor. The jar shatters and stuff goes everywhere. And in this moment, the thought that comes up in my mind is: “You’re really a klutz, but I love you.”

And I think, “Look at that!” I thought nothing was happening, during all my loving-kindness meditations. But something was happening.

The problem of incessant self criticism is not just mine alone, of course. So many people suffer from it. Over time, we start suggesting to other people that they give their inner critic a name, give it a persona. Because everything is going to depend on how you relate to that inner critic.

Many years after starting the retreat center, I name my own inner critic Lucy — after the character in the Peanuts comic strip. I had seen a cartoon where Lucy is talking to Charlie Brown. She says to him, “You know, Charlie Brown, what your problem is? The problem with you is that you’re you.”

Not long after I see that cartoon — and name my inner critic Lucy — something really good happens for me. I flow effortlessly into a yoga posture that had eluded me for years. The first thought I have is: “It’s never going to happen again.”

I flow effortlessly into a yoga posture that had eluded me for years. The first thought I have is: “It’s never going to happen again.”

And then I breathe. I respond to the thought with: “Hi Lucy. Chill, Lucy. Just chill out.”

It’s not, “You’re right Lucy. You’re always right.”

It’s not, “I can’t believe Lucy is still here after all this work.”

It’s: “Hi Lucy. Chill.”

I’m now aware of Lucy. And I know that my awareness is stronger than she is.

Nearly 50 years later, I’m still on this path. The North Star of awareness and kindness I found so long ago is deliberate and clear. Even when I lose sight of it for a bit, or overlook it, it’s ok. Because I have a direction. And I’ve learned that when I lose it, or fall down, I don’t have to call it a failure. I can see what has to be done to reconnect to my sense of purpose, to reorient to my North Star, and begin again. And the North Star is, truthfully, pretty simple to find again: Be patient, be kind, including — no, especially — to myself.

GUNATILLAKE: Thank you Sharon.

Ok full disclaimer: As I said up top, Sharon is a bit of a hero of mine. No actually, she’s a massive hero of mine. That I (and others like me) do what we do is in large part because she did what she did. The first generation of Western teachers such as Sharon and Joseph Goldstein, who trained in Asia and brought it all back to North America and Europe, are genuine pioneers. Modern mindfulness just wouldn’t exist as it does now without them. So when I say thank you Sharon, I can’t actually express the level of my gratitude to her.

So, all that means, leading a meditation to complement Sharon’s story feels a bit like writing a story for Salman Rushdie or cooking for Gordon Ramsey (without the swearing). But I’ll give it a go.

Oh yeah, maybe I should give myself a break right?

And what we’ll do together is something quite close to what Sharon would have done in that first retreat of hers. Her teacher for that time, SN Goenka, is a hugely influential figure, and so let’s do a short meditation inspired by his core practice style.

And if you like, you can imagine yourself in that center in Bodh Gaya. I’ve been out there, and it’s a very inspirational place. It’s also really quite hot. So sit as comfortably as you can. Knowing that I am sitting with you, as is everyone else listening, all the other members of this community.

We’re here. Together. Our energy’s a warm glow.

When outside is a bit quiet, and inside is a bit quiet, we can sometimes know our breathing by the sensations at the tip of the nose. The subtle rush of air as it leaves the nostrils, warm. The intake of the air as it comes in.

It is subtle but let’s put our attention here, and see if we can locate it with our awareness.

And if we can, resting our awareness, our attention here, at the tip of the nose. With face and shoulders relaxed. Our vast vast awareness in this relatively small area.

Setting this intention of resting our awareness at the tip of the nose, and noticing what happens.

Giving ourselves a break if needs be. And if there is a sense of stability here, however small, enjoying it.

And if there is a sense of stability here, however small, enjoying it.

Now, we’re going to do what is called a body scan. Moving our attention from here at the tip of our nose, here on our nostrils.

Moving it down the body, as slowly as feels ok for you. Knowing what is happening all along the way to the tips of our toes. Just knowing, not judging. Just knowing, with stability as our foundation. Interested in the detail, the fine structure. Moving the attention down to our toes.

Resetting. And slowing bringing the awareness back up through the body. Bringing as much awareness game as you can right now. Sensitive to the fine structure of sensations, knowing them and moving on.

Jaw soft. Self-judgment soft. And continuing to move your awareness through the body, slowly, with mind bright. Your mind knowing as much detail as it flows.

In meditation, giving ourselves a break is as much a skill as concentration or fine awareness. I remember a time when I quit a retreat in despair, angry at myself for not making the progress that I wanted, angry that I wasn’t doing it right.

Looking back at that time, I wish I had been more open, open to learning from what was there, not getting upset about what was not.

So thank you Sharon for reminding me about how kindness to ourselves is that which holds all wisdom together. And for your kindness over the years. You didn’t have to teach, but you did, and it changed everything. Made everything.

And thank you. You’re alright too.

Online Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) (Free)

Online Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)

This free online course is designed by a certified Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) instructor. The course is based on the program of John Kabat-Zinn, which he created at the Medical School of the University of Massachusetts.

Welcome!

I am very glad that you have visited this site. Here is a complete 8-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction course, specially designed for those who, for one reason or another, cannot complete the MBSR in person. In free access you will find all the materials that I use in my full-time course, including meditations, articles, videos. I thank the graduates of the program who translated the site materials into Russian: Natalia Fedunina, Oksana Laskovsky-Zabaznovski, Evgenia Askenazi, Ekaterina Gakova, Yuri Arustamyan, Margarita Lev, Sergey Makarkin, Elena Berdinkova. – Dave Potter

In free access you will find all the materials that I use in my full-time course, including meditations, articles, videos. I thank the graduates of the program who translated the site materials into Russian: Natalia Fedunina, Oksana Laskovsky-Zabaznovski, Evgenia Askenazi, Ekaterina Gakova, Yuri Arustamyan, Margarita Lev, Sergey Makarkin, Elena Berdinkova. – Dave Potter

Today, free software is viewed with some distrust. I keep getting emails asking if the course is free. Here are some of the most popular questions.

Is it true that the online MBSR course is completely free?

Yes. There is no catch here: no fee, no spam, no registration requirement or personal data (including email).

What are your qualifications and why do you not charge for the course?

I am a certified MBSR instructor trained at the University of Massachusetts School of Medicine. Conducted full-time MBSR courses for 12 years. Before that, I worked as a psychotherapist, and also practiced daily meditation for a quarter of a century. When I discovered MBSR, I wanted to share this practice with my clients and others. In 2004, I started teaching two face-to-face courses a year, and for the convenience of the students, I posted some parts of the course online. I soon realized that a little refinement and transfer to an online format could be very useful for people who would never come to a face-to-face course due to financial, territorial or other reasons.

When I discovered MBSR, I wanted to share this practice with my clients and others. In 2004, I started teaching two face-to-face courses a year, and for the convenience of the students, I posted some parts of the course online. I soon realized that a little refinement and transfer to an online format could be very useful for people who would never come to a face-to-face course due to financial, territorial or other reasons.

Creating and improving this resource has been a matter of love, creativity, freedom, and I am happy to share these materials free of charge. This was made possible thanks to the economy of the Internet, the structure of the course, and the generosity and generosity of other teachers. I am pleased to know that anyone with access to the Internet can find and use the wealth of material collected here, whether they live in Moscow (Idaho) or Moscow (Russia).

How effective is the online MBSR format?

Of course, the full-time fortam MBSR program is the best way to master mindfulness practices. In particular, the likelihood of passing the program to the end increases due to live communication and support in the group. However, full-time course completion is not always possible. This online course has exactly the same structure and provides the same resources as my in-person course. Mastering all the practical exercises, working with the site materials can make the learning process no less deep. In fact, feedback from online learners at the end of the program shows that it is just as productive for them as it is for those who took it in person.

In particular, the likelihood of passing the program to the end increases due to live communication and support in the group. However, full-time course completion is not always possible. This online course has exactly the same structure and provides the same resources as my in-person course. Mastering all the practical exercises, working with the site materials can make the learning process no less deep. In fact, feedback from online learners at the end of the program shows that it is just as productive for them as it is for those who took it in person.

It is not easy to complete the program on your own for all 8 weeks, so I tried to make it interesting and varied, which became possible, in particular, thanks to the generosity of recognized masters whose videos and articles are posted on the site, including John Kabat-Zinna (Wherever you go, you are already there), Pema Chodron , Tara Brach (Radical acceptance), Sylvia Burshtein (Not to do, but to Be), Sharon Salzberg (A heart as big as the world), Robert Sapolsky (Why zebras don't get ulcers), Marshall Rosenberg (Nonviolent Communication) Jack Combild (The Way to the Heart). *

*

Is it possible to know a little more about what this course is

The introduction describes what awareness is and how the course is structured. The materials for each of the eight weeks are divided into several blocks: videos, reading materials, tasks for formal and informal practice, additional materials, which helps to integrate knowledge and experience. The “About the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction” section provides a brief description of the program.

Everything you need is freely available on this site. Whether you complete the entire course or not is up to you. But all the wealth of materials, including video materials and articles by the above and other authors, all this is presented to your attention free of charge.

Registration is not required. You can start when you're ready

This is a completely self-guided course (no registration, verification, tracking, etc.). In case of successful completion of all eight weeks of the course and the provision of the materials indicated in the Certificate of Completion section, I will write you a personal letter of congratulations and send you a certificate. There is also no charge for it. You will be required to provide seven completed tables describing the passage of formal and informal practices, as well as one page of reflection on what you have learned and how you can bring new knowledge and skills to life.

There is also no charge for it. You will be required to provide seven completed tables describing the passage of formal and informal practices, as well as one page of reflection on what you have learned and how you can bring new knowledge and skills to life.

If you are ready to start, or would like to learn more about mindfulness and this program, please go to Introduction .

* Many course materials are provided by other teachers, researchers, practitioners, writers. I thank them for their help. Their generosity and generosity made this free online course possible.

5 Things You Should Know About Mindfulness and Work / Sudo Null IT News0001

According to famed meditation expert Sharon Salzberg, meditation may seem like a "superstition" at first glance, but it can help you improve your productivity at work. Mindfulness and meditation will make you more productive by increasing concentration and helping to control impulses, and will not take much time . It works when you do more than 5 minutes a day and weave this practice into your routine.

It works when you do more than 5 minutes a day and weave this practice into your routine.

This conversation was with Sharon Salzberg, eight New York Times best-selling author and, more notably, a meditation coach credited with introducing Buddhism to the West in the 60s and 70s. I think you'll like it.

Sharon was late. There was no traffic around, and she sat in the back seat of the taxi, worried that the driver would not have time to change lanes. Then he turned to her and said the phrase that she still remembers: "Madame, the number of cars on the road is not your fault and not mine."The taxi driver retained a rare self-awareness and, even more unusually, he carried it over to his job. Sharon believes we can cultivate this attitude through mindfulness meditation.

I recently asked Sharon about meditation and work. Below are the 5 most powerful lessons we've talked about.

But first, it’s worth dispelling a couple of myths about what meditation is.

What is meditation

Sharon explains that contrary to popular belief, meditation has nothing to do with "superstition and anything paranormal."

The study of meditation is beneficial: it can shake your preconceptions and give you a better understanding of mindfulness. According to Sharon, one of the reasons people turn to meditation is to see what the scientists are fussing about, given that there is a growing body of research surrounding meditation.

One of the myths, for example, is that when you meditate, you should try to stop all your thoughts. It is not true. Sharon explains: “The purpose of meditation is not to stop thinking… but to change your attitude towards thoughts, to stop constantly getting lost in them and to fight them.”

Meditation simply means a deep awareness of the present moment, a constant return of attention to what you choose to focus it on (for example, breathing). In fact, it does not interfere with a result-oriented work environment and can even increase your productivity.

1. Meditation increases concentration at work

It didn’t take a year of crazy experiments to realize that focus is the key to productivity. The better you can concentrate, the more you can do.

Mindfulness and meditation can help in this matter. Sharon told me that concentration is "one of the fundamental skills of meditation" . As lifting weights trains the arms, so meditation enhances concentration .

Sharon says that by meditating, "you learn to collect unbridled energy and distribute it, so you become more focused and have more forces at your disposal that can be used purposefully" . Meditation does require serious concentration - by focusing on the present moment, you are actually training your ability to maintain attention, improving it.

One of the main reasons why meditation helps you focus is this: it creates a mood less susceptible to stimuli. Thinking about the past, for example, usually distracts us from our current work and reduces our productivity.

Another factor here is the negative internal dialogue: fixation on ruthless self-criticism is the path to absent-mindedness. But Sharon notes that through meditation, “we gracefully put everything out of our heads and start from scratch, which is one way to work. As a result, you stop wandering among such clichés: I am so bad. I am a loser. I'm so terrible. This will never change."

Attention to our way of thinking will allow us to get rid of such accusatory internal dialogue, making us not only more productive at work, but also happier.

2. Meditation helps to control impulsiveness

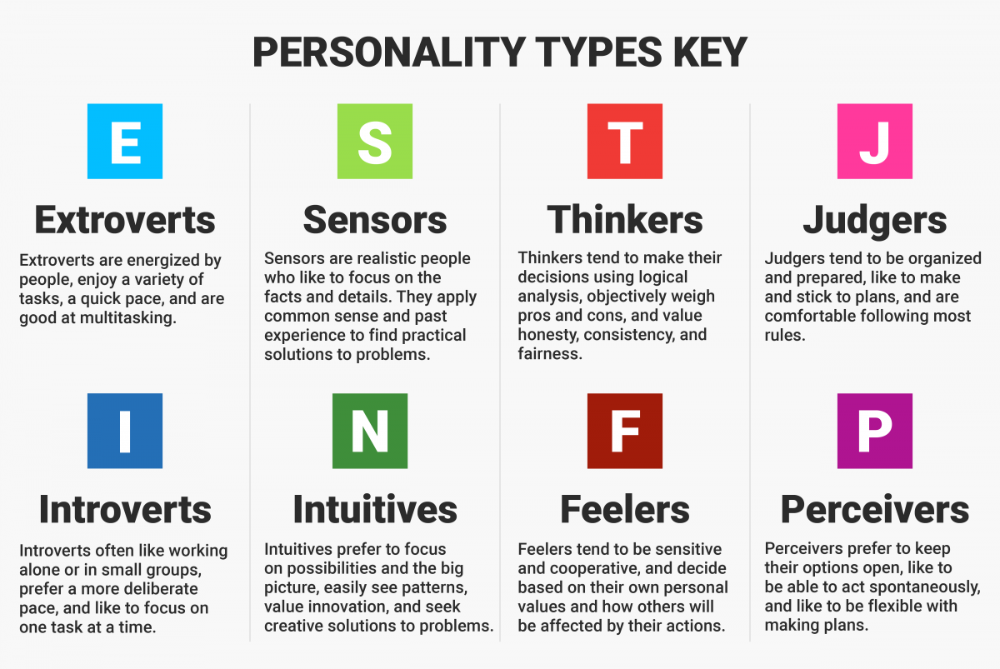

According to Sharon, meditation improves the ability for purposeful activity, which is directly related to impulse control.

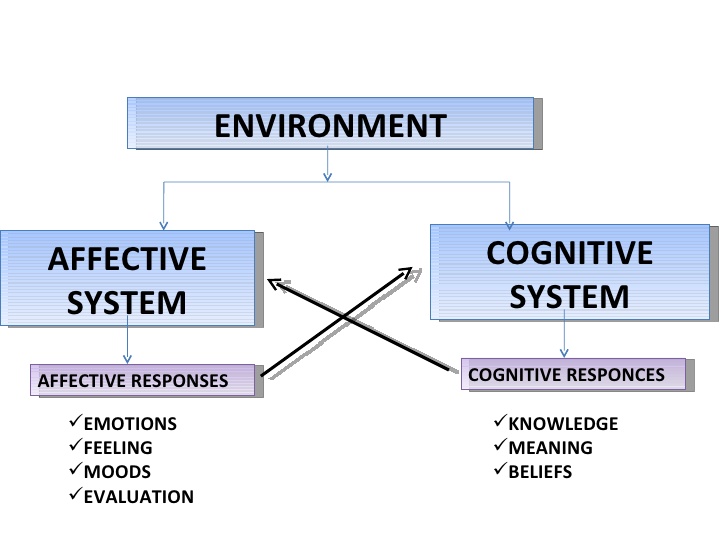

Attention to oneself is the ability to be aware of momentary feelings, which, in turn, frees one from the need to control these feelings. There is even evidence0130 ★ that mindfulness contributes to an increase in the areas of the brain responsible for controlling impulses.

One 2012 study did indeed find ★ that "a short period of mindfulness meditation can serve as a quick and effective strategy to promote self-control in under-resourced settings" . Meditation can recharge your self-control battery.

According to Sharon "research shows that meditation has a strong effect on executive function" and "improved executive function is a sign of decreased impulsivity in people" .

Impulses can be distracting from work, so we want to reduce them. Whether you just want your boss to not catch you doing non-work related activities, or you really want to increase your efficiency, meditation and mindfulness can help you.

What I find interesting is that not only do we have scientific proof of these facts, but we are beginning to understand why. A 2013 study in Psychological Science explains that "attention to the present moment and non-judgmental perception of what is happening, which are cultivated by mindfulness training" , certainly increase our ability to notice small changes in our own emotions. This prepares us to manage them and reduce the number of impulses.

This prepares us to manage them and reduce the number of impulses.

3. Meditation does not take much time

Some people fear that once they start their workouts, the time they spend on meditation will increase, making them even less productive than before. Although even a strenuous practice will undoubtedly save time, you can shorten it by limiting the duration of your sessions. The limit will be even tighter if you try to combine meditation with an intense work process.

Sharon remembered a conversation from some time ago in which her friend mentioned that he wanted to meditate.

Sharon asked, "How much time can you realistically devote to this?""10 minutes a day for a month," he replied.

"That will be enough," Sharon replied.

A little bit of meditation is better than no meditation at all, so you should start with an exercise duration that is comfortable for you—even if it's 5, 10, or 20 minutes a day.

The idea that even short episodes of mindfulness meditation can be beneficial is supported by research ★ .

4. Meditation can be woven into routine activities

You can painlessly incorporate meditation into your day by linking mindfulness episodes to normal activities.

Sharon began to understand this idea clearly when her Tibetan teacher encouraged brief moments of mindfulness throughout the day along with officially recognized periods of meditation. They called it "short moments many times."

For her book Real Happiness at Work ★ Sharon asked the question about short moments many times: "What would it look like if you were at work?"

The answer is that it will seem like you are doing something ordinary, just add awareness to it. Sharon recommends picking an activity you're already doing and using it as a cue to spend a few seconds on the exercise.

For example, when the phone rings, you should skip 3 beeps before answering. Use the free time to involve your consciousness in the current moment. She notes that the same principle works with email: "after writing a letter, do not immediately click on" send ". Take a few breaths in and out, reread it, and then decide if you want to send it out.” .

Use the free time to involve your consciousness in the current moment. She notes that the same principle works with email: "after writing a letter, do not immediately click on" send ". Take a few breaths in and out, reread it, and then decide if you want to send it out.” .

5. Meditation works best if you practice more than 5 minutes a day

Sharon meditates daily for 30 or 40 minutes, but of course this is not for everyone. She recommends making at least 20 minutes of practice a day a goal, although she admits that it may take time to get there. This is especially true if you have a responsible job.

“Why did I say exactly 20 minutes a day? The reason is that many people sitting at home will be completely in the power of thoughts for the first 5 or so minutes, , she says. It can take time to "settle" in the present moment, so meditation for at least 5 minutes is optimal.

But if it seems impossible, don't give up.