Sensory eating disorders

Exploring Sensory Process Disorders Connection to Eating Disorders:

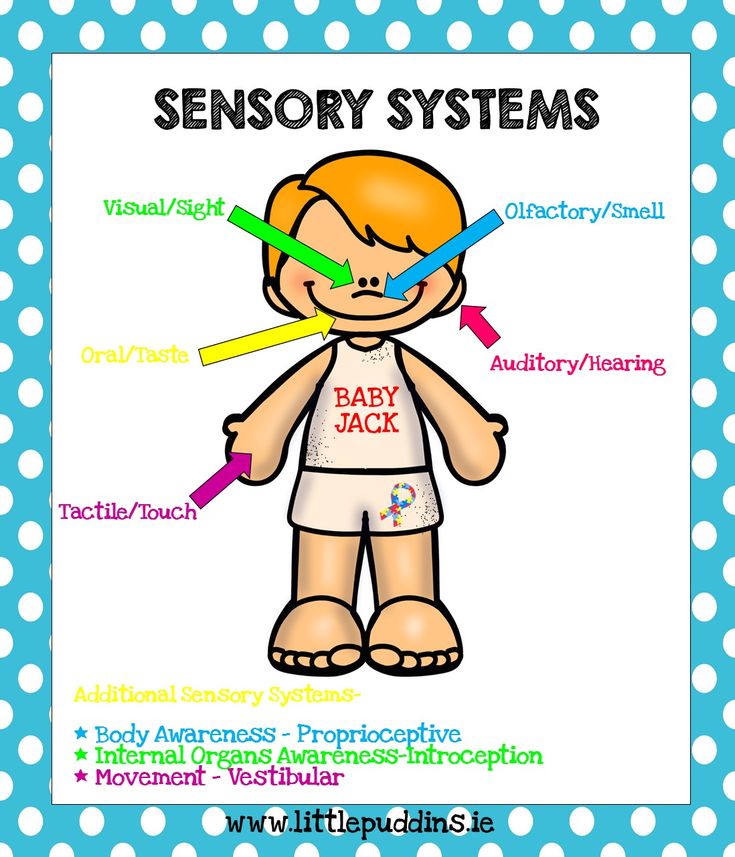

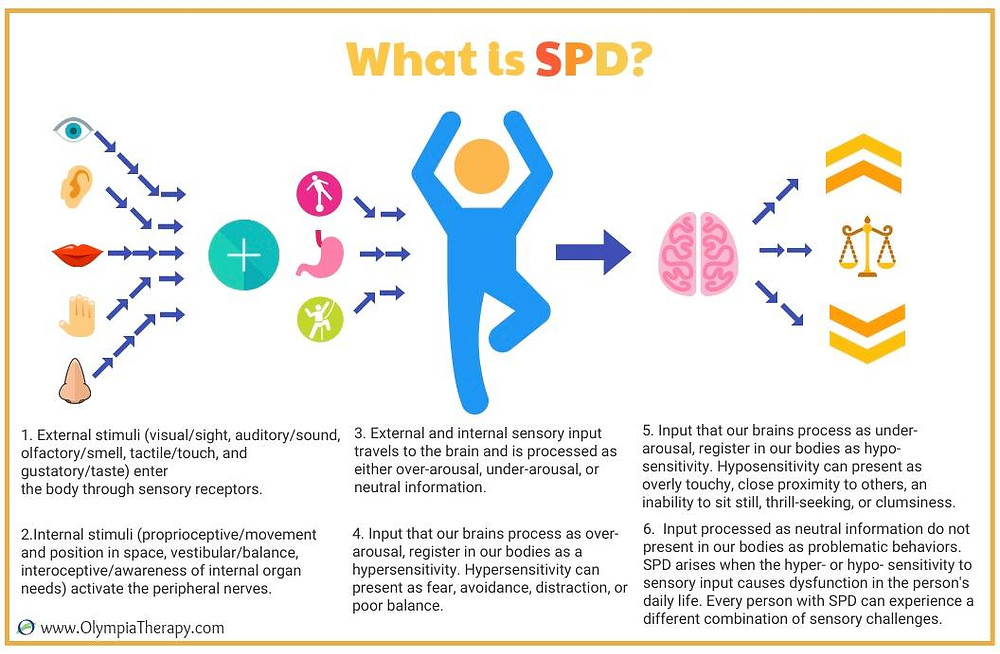

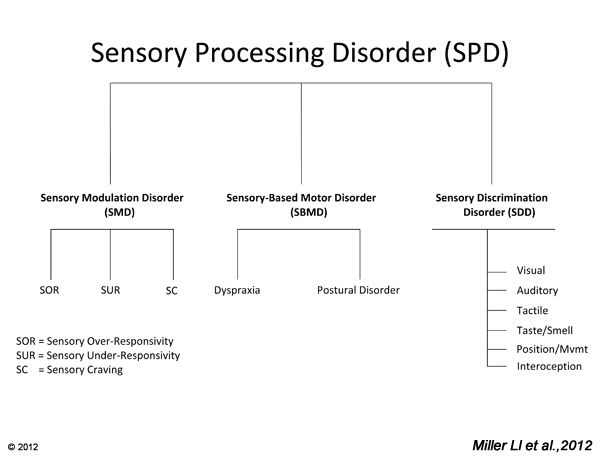

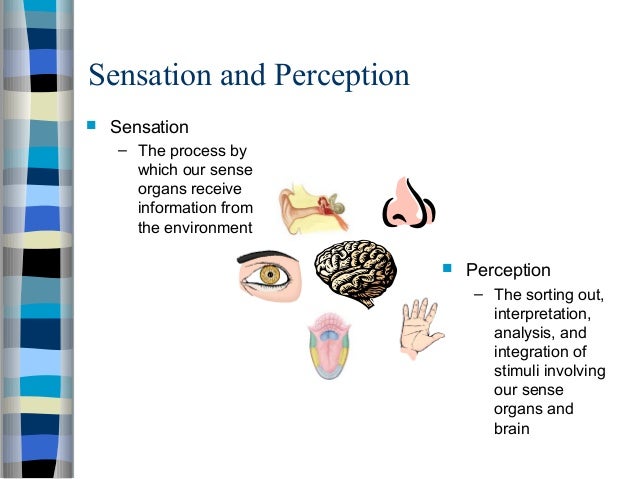

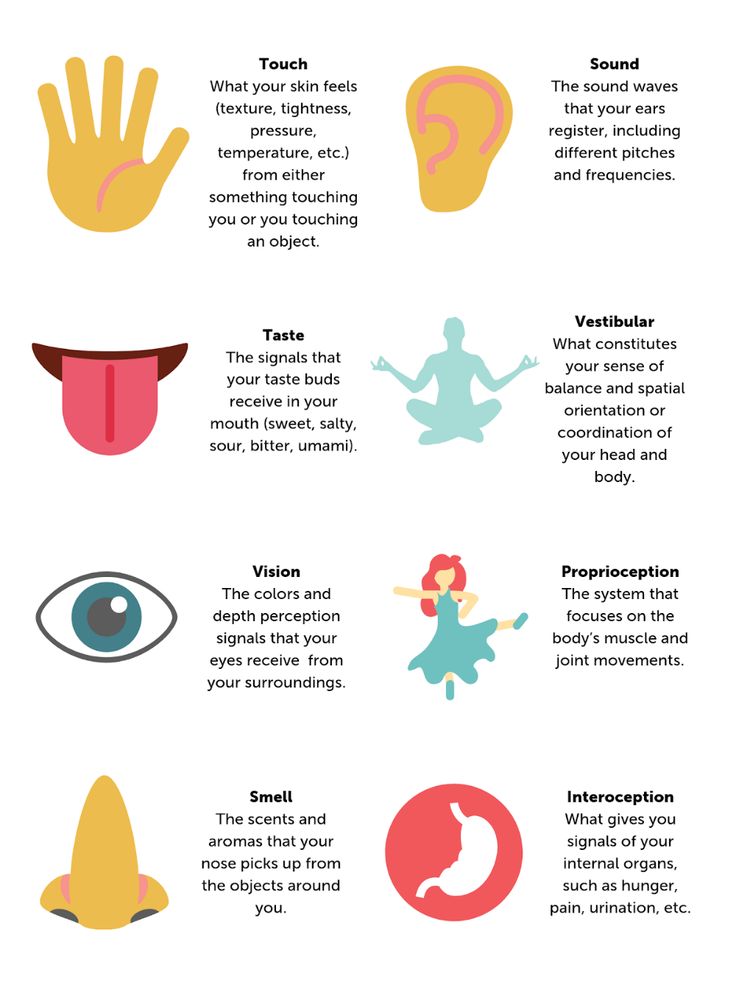

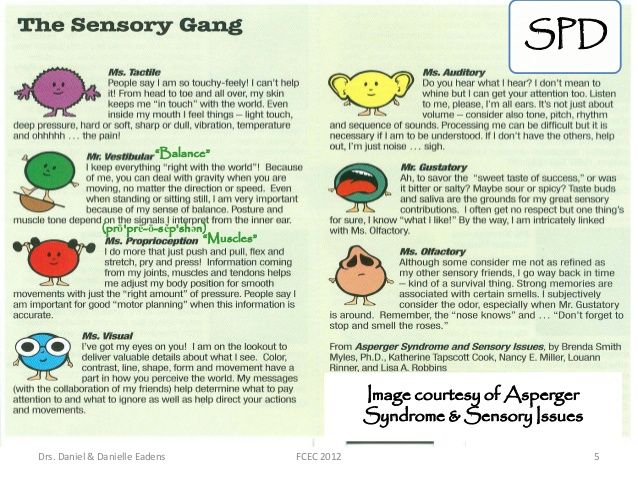

A sensory processing disorder (SPD) alters typical food responses. You’re more likely to notice how something tastes, feels, or sounds. And during mealtimes, your senses could keep you from enjoying some types of food.

Children with ADHD or autism are sometimes diagnosed with SPD. But adults can have the problem too, and if you do, you’ve probably lived with your disorder for years.[1] You may have an arsenal of tools you can use to keep people from noticing your unusual reaction to food.

Up to 16% of school-age children have sensory processing disorder, and since the issue can’t be cured, the same percentage of adults likely have problems too.[2] If you’re one of them, know that your eating patterns could cause health issues, but d treatment programs can help.

Sensory Processing Disorder & Eating

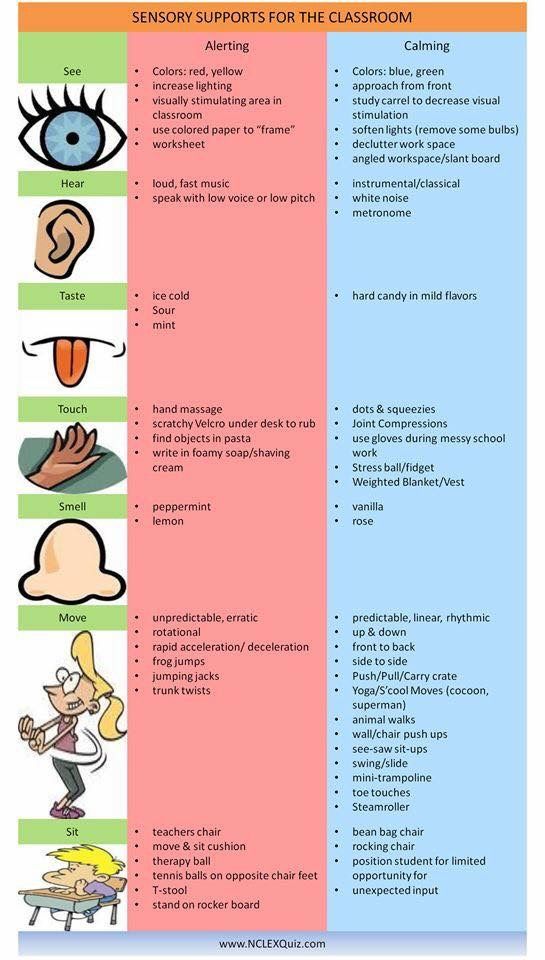

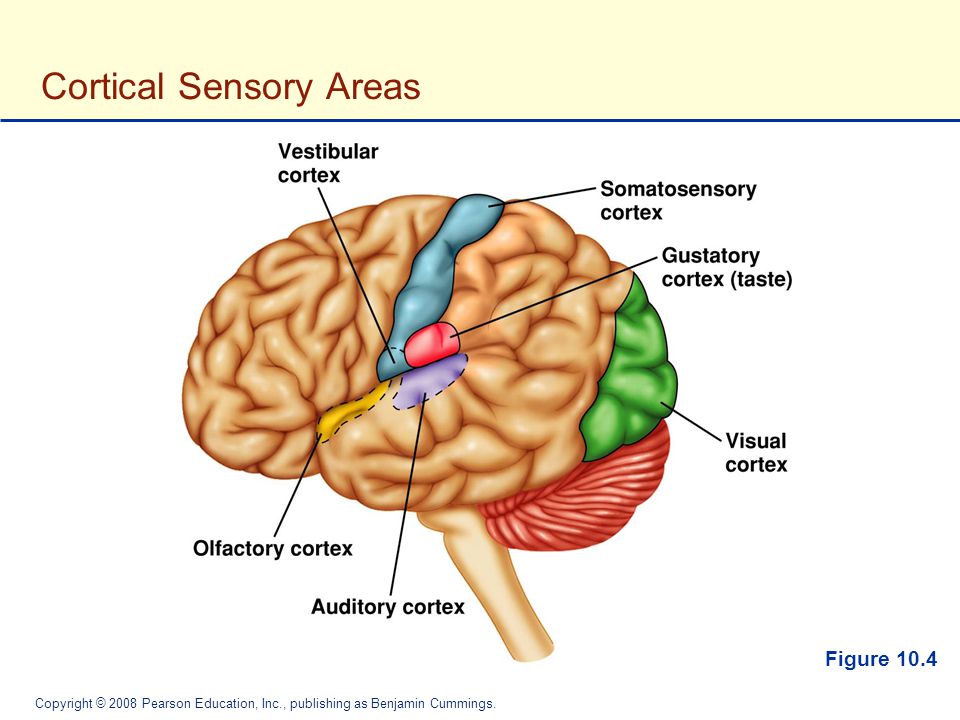

Eating a meal is a complex sensory experience consisting of foods with ranging appearances, odors, textures, and tastes.

If you eat with others, they may contribute sounds that further impact your sensory system. You may feel overwhelmed by your senses, and you may eat very little or nothing at all as a result.

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) shares characteristics with SPD eating. People with both issues fit the following criteria:[3]

- Picky eating: You may only eat from a small list of approved foods.

- Inflexibility about food: Deviations from the approved food list aren’t allowed.

- Inability to try new foods: You eat about 20 foods (or less), and you don’t want to add anything else to this list.

People with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder have more of these symptoms than people with SPDs.[3] Their lives are deeply impacted by them. But the stronger your symptoms, the more likely it is that you’re moving from SPD to ARFID.[5]

A Common Sensory Processing Disorder Diet

Disordered eating related to sensory processing is variable. You may have favorite foods that someone else won’t touch. But most people with SPD share preferences.

You may have favorite foods that someone else won’t touch. But most people with SPD share preferences.

Your distinguished palate and food sensitivity may draw you to high-calorie, palatable foods.[5] You might enjoy things like chocolate, as it’s smooth and relatively consistent from batch to batch.

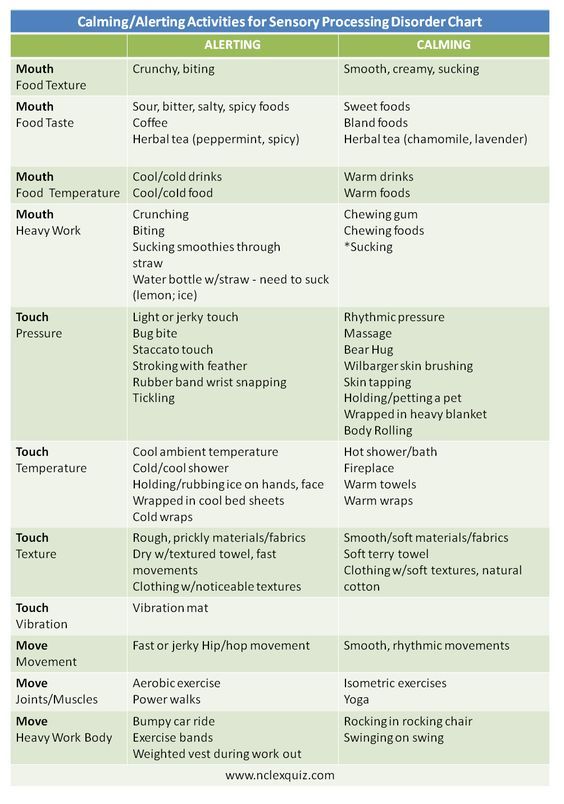

You may also have strong preferences about the following:[6]

- Texture: You may only like foods that are smooth and pureed. Or you may only like things that are crunchy and crispy.

- Flavor: You might like bland foods (like potatoes) and stay away from strongly flavored meals (like curries).

- Smell: You may like buttery things (like swiss cheese) but avoid things with a strong smell (like blue cheese).

You may like to keep your food groups separate rather than allowing items to touch on your plate. You may also want to eat while away from other people, as talking or hearing others while you’re eating can make you more uncomfortable.

What Causes Sensory Processing Disorder?

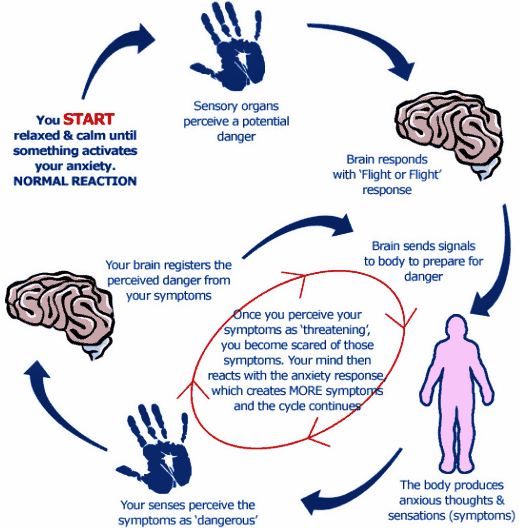

If you have sensory processing disorder as an adult, you’ve probably had symptoms throughout your life. A traumatic episode or difficult conversation can’t spark the disorder. But your symptoms may wax and wane throughout your life, depending on your stress level.

A traumatic episode or difficult conversation can’t spark the disorder. But your symptoms may wax and wane throughout your life, depending on your stress level.

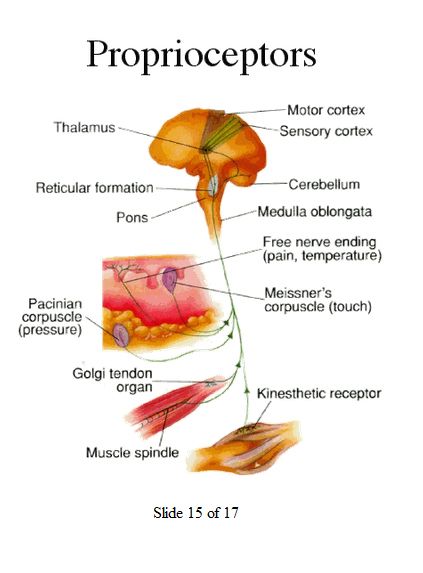

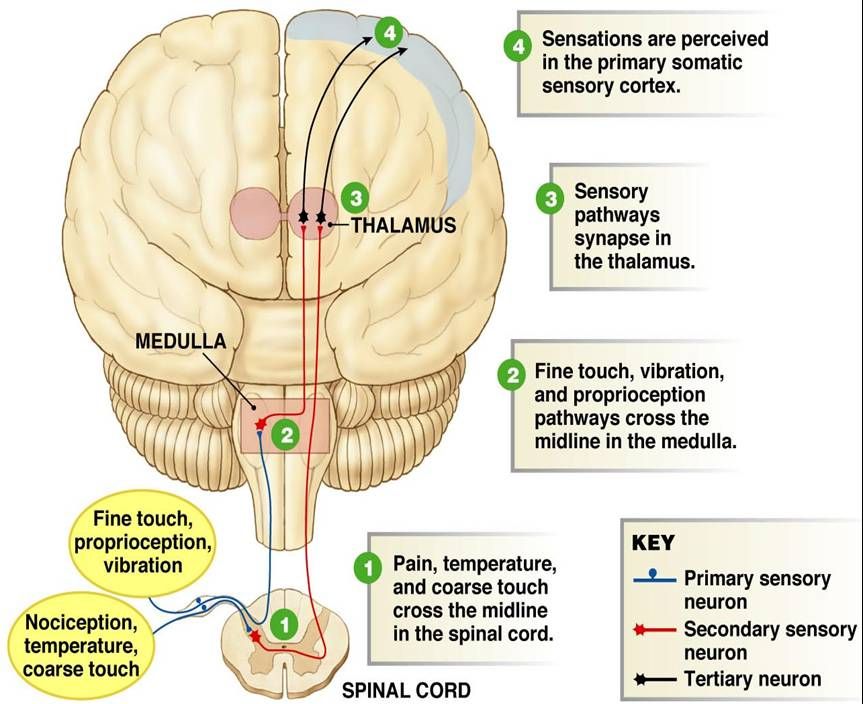

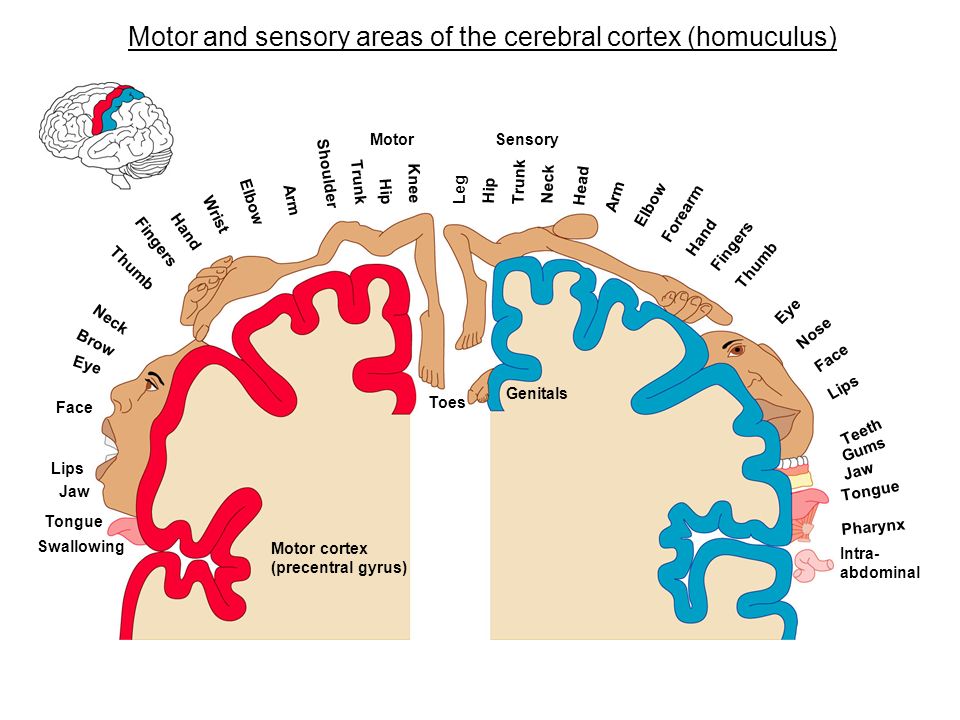

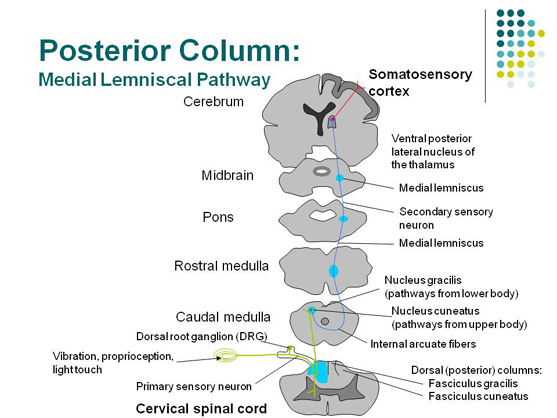

Researchers say people with SPD have abnormal tissues in their brains that might block communication between the left and right sides of the brain.[7] In essence, your body takes in data, but it can’t communicate the information properly and make sense of it.

Psychological factors include perfectionism, anxiety, depression, difficulty regulating emotions, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, and a rigid thinking style. Sociocultural risk factors can include cultural promotion of the thin ideal, size and weight prejudice, an emphasis on dieting, and ideal body definitions that include a narrow range of shapes and sizes.

Biological risk factors for eating disorders include having close family members with an eating disorder; a family history of mental health issues, such as depression, anxiety, and/or addiction; a personal history of depression, anxiety, and/or addiction; food allergies that contribute to picky or restrictive eating; and type 1 diabetes.

Related Reading

- Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder

- Autism and anorexia

- ADHD and co-occurring eating disorders

Risks for a Sensory Picky Eater

When you’re unable to tolerate specific foods, sensory processing disorder can produce symptoms that are similar to those seen in eating disorders. Situations such as long, drawn-out meal times combined with a small appetite can lead to poor nutrition and significant weight loss.

Those with SPD often report gastrointestinal issues or digestion problems, including stomach pain, diarrhea, constipation, acid reflux, vomiting, or bloating, which can also occur in those with eating disorders. Food allergies are also common in both disorders.

Treatment for a Sensory Eating Disorder

A limited diet is dangerous, and while it might seem normal to you, it’s not healthy. Treatment can help you get back on track.

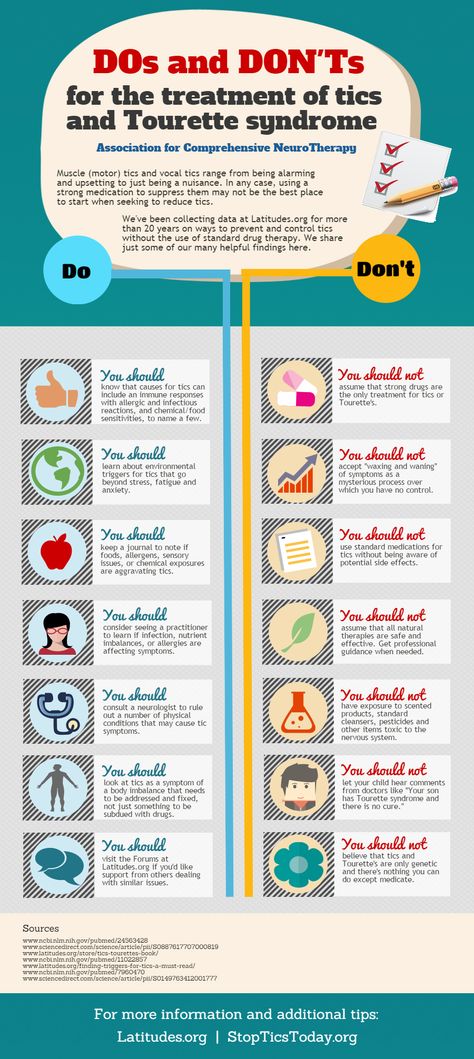

Some therapists use sensory integration to challenge your senses and help you feel a sense of accomplishment when you try something new. [8] You might also use therapy to explore how foods you’ve avoided make you feel, and you might be exposed to them in very small increments to help you adjust to them.

[8] You might also use therapy to explore how foods you’ve avoided make you feel, and you might be exposed to them in very small increments to help you adjust to them.

While you may always have sensory processing disorder, therapy can help you maintain a healthy weight and enjoy meals once again.

References

-

- Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD). American Academy of Family Physicians. https://familydoctor.org/condition/sensory-processing-disorder-spd/. August 2021. Accessed July 2022.

- Picky vs. Problem Eater: A Closer Look at Sensory Processing Disorder. Food and Nutrition. https://foodandnutrition.org/september-october-2014/picky-vs-problem-eater-closer-look-sensory-processing-disorder/. August 2014. Accessed July 2022.

- Adult Picky Eaters with Symptoms of Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder: Comparable Distress and Comorbidity but Different Eating Behaviors Compared to Those with Disordered Eating Symptoms. Journal of Eating Disorders.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5086050/. October 2016. Accessed July 2022.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5086050/. October 2016. Accessed July 2022. - Atypical Sensory Processing is Associated with Lower Body Mass Index and Increased Eating Disturbance in Individuals with Anorexia Nervosa. Psychiatry. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.850594/full. March 2022. Accessed July 2022.

- Food Intake is Influenced by Sensory Sensitivity. PLOS ONE. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3423386/. August 2012. Accessed July 2022.

- It’s Not ‘Picky Eating’: Five Strategies for Sensory Food Sensitivities. Organization for Autism Research. https://researchautism.org/its-not-picky-eating-5-strategies-for-sensory-food-sensitivities/. March 2017. Accessed July 2022.

- Breakthrough Study Reveals Biological Basis for Sensory Processing Disorders in Kids. University of California San Francisco. https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2013/07/107316/breakthrough-study-reveals-biological-basis-sensory-processing-disorders-kids.

July 2013. Accessed July 2022.

July 2013. Accessed July 2022. - How to Treat Sensory Processing Disorder. ADDitude. https://www.additudemag.com/sensory-processing-disorder-treatment/. July 2021. Accessed July 2022.

Popular Categories

© Copyright 2022 Eating Disorder Hope. All Rights Reserved. Sitemap.Privacy Policy.Terms of Use.

MEDICAL ADVICE DISCLAIMER: The service, and any information contained on the website or provided through the service, is provided for informational purposes only. The information contained on or provided through this service is intended for general consumer understanding and education and not as a substitute for medical or psychological advice, diagnosis, or treatment. All information provided on the website is presented as is without any warranty of any kind, and expressly excludes any warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose.

Call a specialist at Timberline Knolls for help (advertisement)

(888) 206-1175

ARFID, ADHD, SPD and Feeding Difficulties in Children

Picky eating is a common and normal behavior, starting between ages 2 and 3, when many children refuse greens, new tastes, and practically anything non-pizza. They are at the developmental stage where they understand the connection between cause and effect, and they want to learn what they can control. For others, feeding difficulties and selective eating are not a phase but symptoms of conditions like sensory processing disorder (SPD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD or ADD), autism, and/or, at the extreme end, Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID).

They are at the developmental stage where they understand the connection between cause and effect, and they want to learn what they can control. For others, feeding difficulties and selective eating are not a phase but symptoms of conditions like sensory processing disorder (SPD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD or ADD), autism, and/or, at the extreme end, Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID).

To successfully address picky eating and related food issues, parents must first recognize possible underlying factors so they can seek the appropriate professional help and treatments.

Picky Eating and Feeding Difficulties: Common Causes and Related Conditions

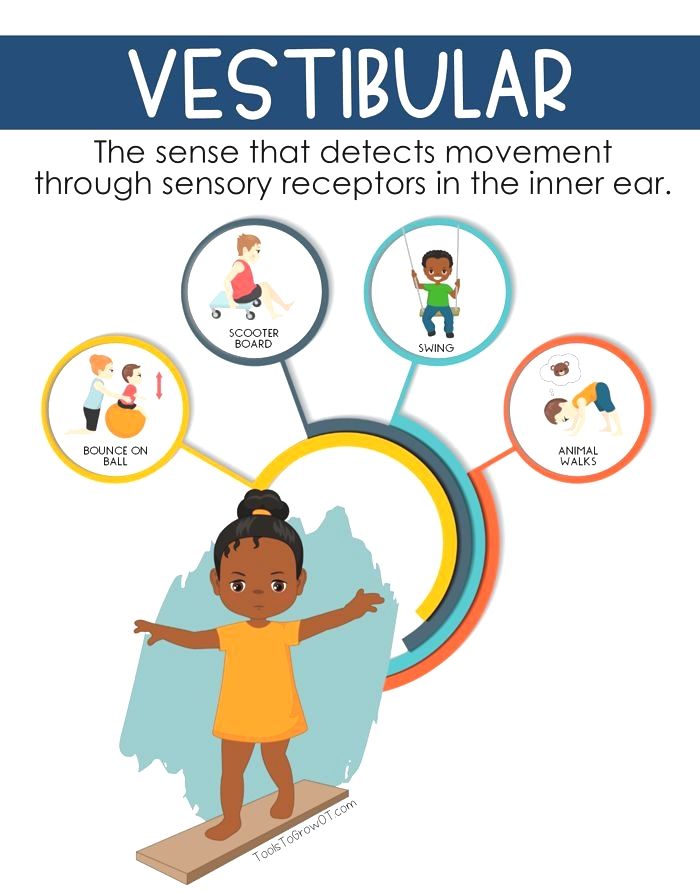

SPD and Eating Problems

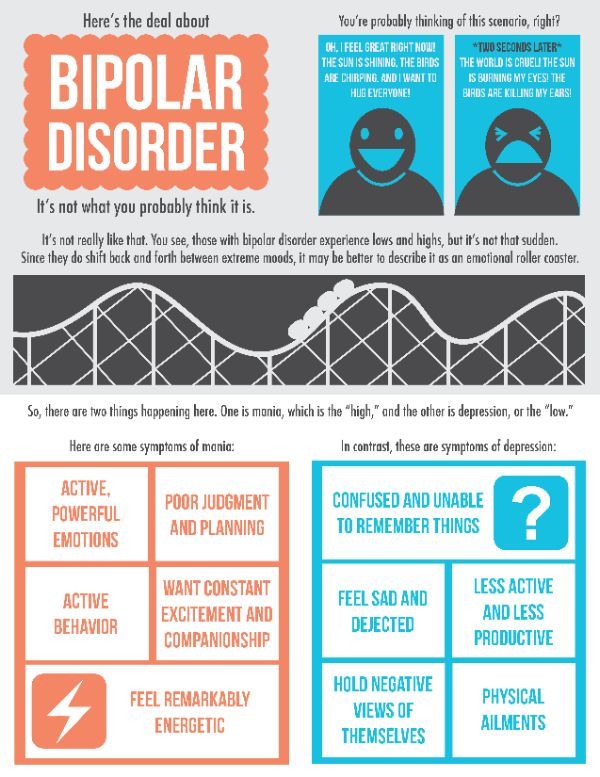

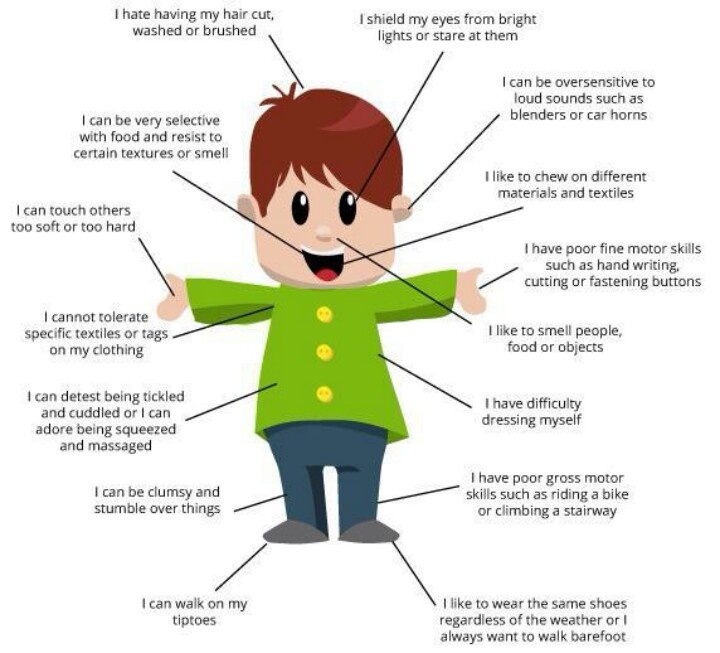

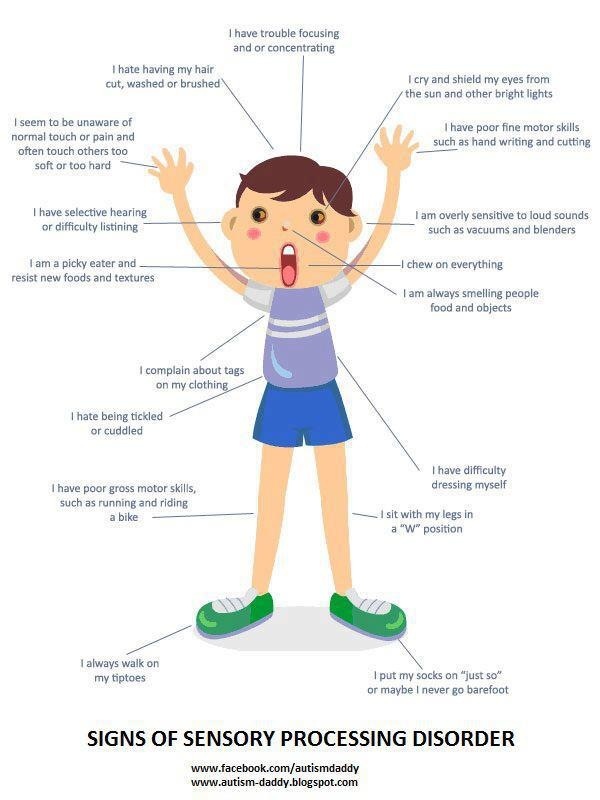

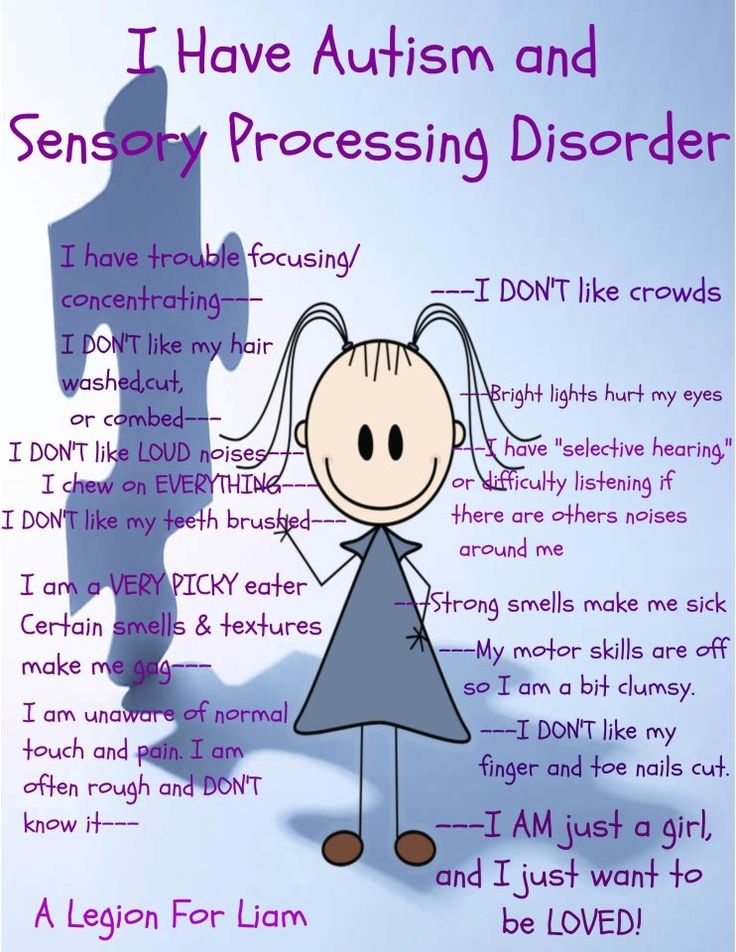

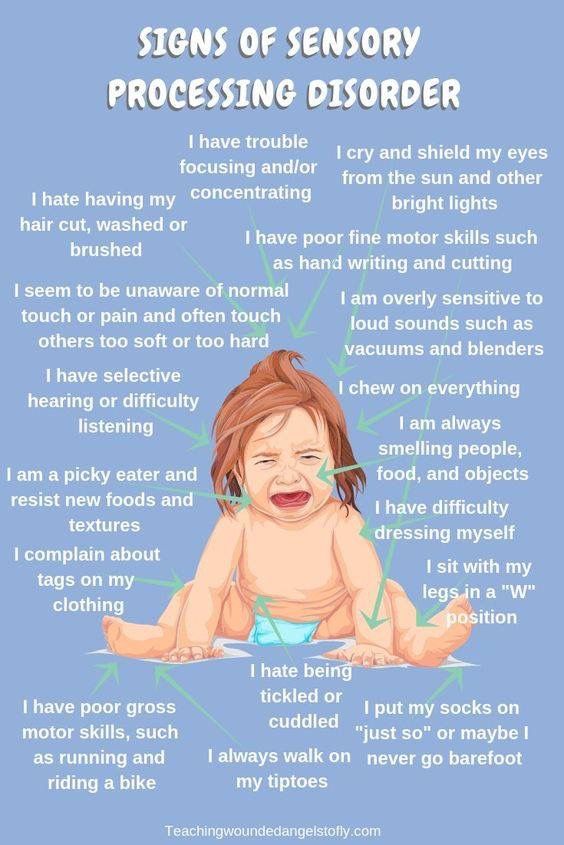

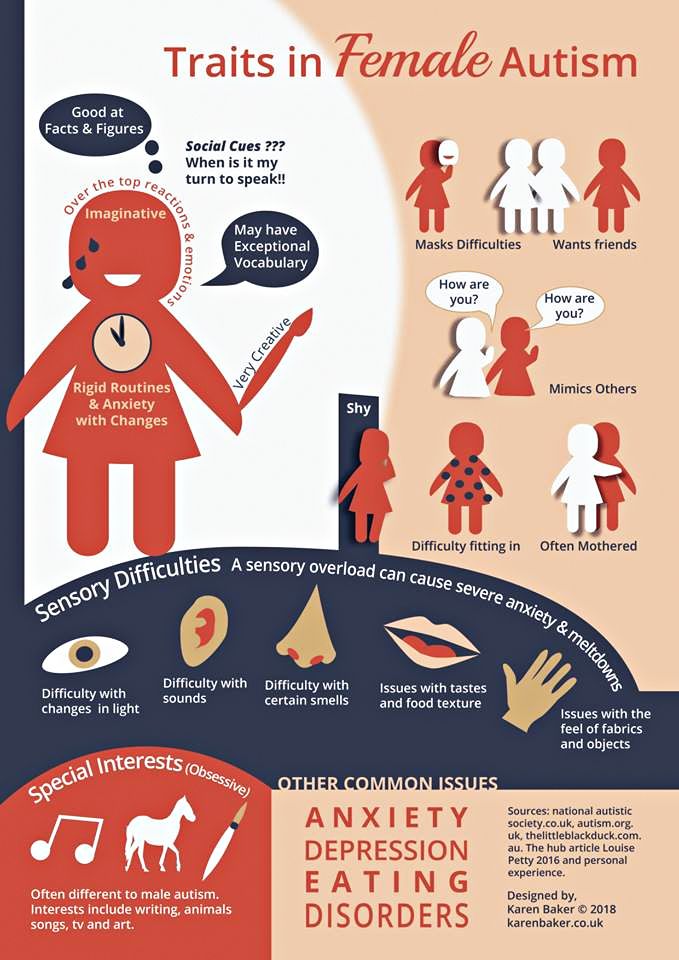

While not an official medical diagnosis, sensory processing disorder is tied to immature neurological development and characterized by faulty processing of sensory information in the brain. With SPD, the brain can misread, under-read, or be overly sensitive to sensory input. Typical symptoms include heightened or deadened sensitivity to sound and light; extreme sensitivity to clothing and fabrics; misreading social cues; and inflexibility. The stress caused by sensory dysregulation can affect attention, behavior, and mood.

Typical symptoms include heightened or deadened sensitivity to sound and light; extreme sensitivity to clothing and fabrics; misreading social cues; and inflexibility. The stress caused by sensory dysregulation can affect attention, behavior, and mood.

Eating is a key SPD problem area, as all aspects of food – from preparation to ingestion – involve reading and organizing data from all of the senses. SPD-related eating issues include:

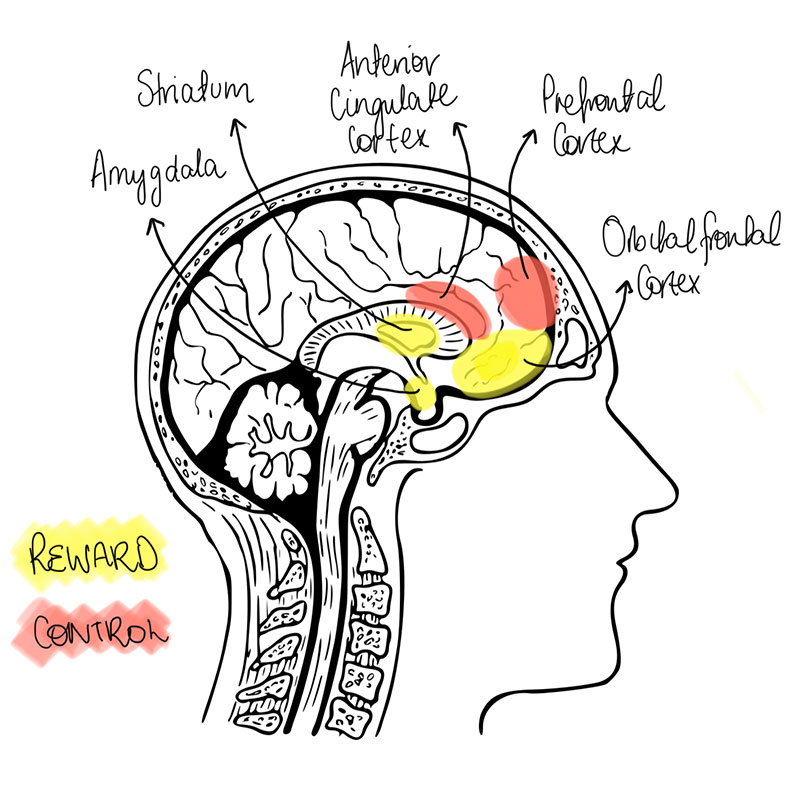

- Appetite: Sensory overload stimulates the release of stress hormones. Mild to moderate stress increases desire for starches and sweets but chronic or high levels of stress reduces the appetite and interferes with digestion.

- Hunger signals. Young children often miss hunger cues when they are playing. They want to stay at the park for just 10 more minutes when it is obvious that without an immediate influx of food, the afternoon will be shot. When elevated to SPD, children rarely notice they are hungry as the hunger signal is lost amidst a mass of misread and disorganized sensory data.

When they do ask for food, they may refuse items that are not to their exact specifications. A small percentage misread satiety, chronically feel hunger and ask continuously for food.

When they do ask for food, they may refuse items that are not to their exact specifications. A small percentage misread satiety, chronically feel hunger and ask continuously for food. - Food sensory characteristics. How the brain makes sense of smell, taste, temperature, color, texture, and more impacts the eating experience. Because food has so many sensory characteristics, there are many areas where children can get thrown off.

[Read: What’s Causing My Child’s Sensory Integration Problems?]

The most common symptom of SPD is psychological inflexibility. Individuals with SPD attempt to limit sensory discomfort by controlling their external environment in the areas where they are overloaded. With eating, this rigidity can mean only one brand of acceptable chicken nuggets (not the homemade ones), the same foods repetitively, strict rules about foods not touching, and random demands about and rejection of core favorites. (e.h. “The apple is bad because of a tiny brown spot,” or suddenly, noodles are on the “don’t like” list. )

)

Autism

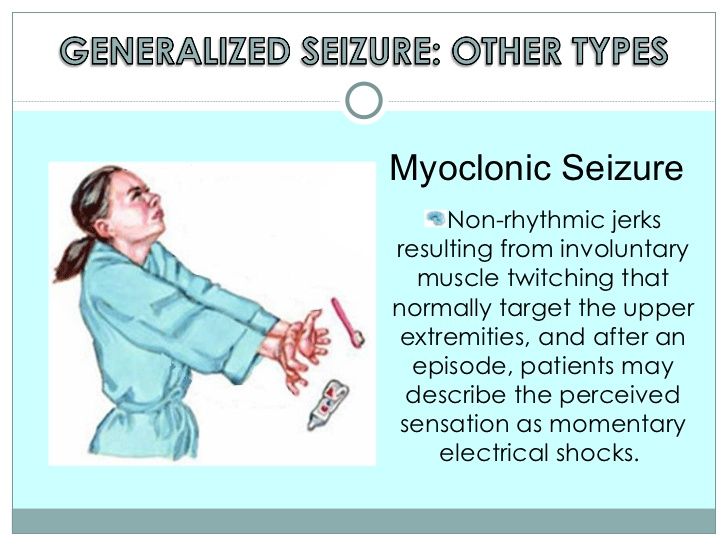

Many people on the autism spectrum identify as having strong or diminished responses to sensory information. If delays in motor planning and oral motor issues are also present, in addition to the sensory aspects of food and eating, children on the spectrum may have trouble chewing and swallowing some foods.

ADHD

ADHD symptoms and behaviors may also contribute to problems with food.

- Impulse control and self-regulation problems can cause overeating and make it difficult to notice and respond to satiety.

- Poor executive functioning can derail meal planning and preparation in adolescents and young adults who prepare their own foods.

- Distractibility and inattention can lead to missed hunger signals or even forgetting to eat.

- Stimulant medications can dull the appetite.

- Mood stabilizers can increase appetite.

[Read: 9 Nutrition Tricks for Picky Eaters]

ARFID

Also known as “extreme picky eating,” ARFID is described in the DSM-5, the guide clinicians use to diagnose health conditions, as an eating or feeding disturbance that can include:

- Lack of interest in eating or food

- Avoiding foods based on sensory characteristics

- Avoiding foods out of concern over aversive experiences like choking or vomiting

These disturbances result in failure to meet appropriate nutritional and/or energy needs, as manifested by one of more of the following:

- Significant weight loss or faltering growth and development

- Significant nutritional deficiency

- Dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements

- Marked interference with psychosocial functioning

To merit a diagnosis, the disturbance must not be better explained by a lack of available food or a culturally sanctioned practice, and it must not be associated with body image concerns or a concurrent medical condition/treatment (like chemotherapy).

Children with ARFID may experience certain foods, such as vegetables and fruit, as intensely unpalatable and take great care to avoid them.1 They may be fearful of trying new foods and rely on highly processed, energy-dense foods for sustenance.1 Common feeding advice like hiding and disguising vegetables in food, relying on your child to “give in” to avoid starving, or repeating requests to eat does not work with children who have ARFID. This disorder is associated with extreme nutritional and health deficiencies.

Research on the prevalence of ARFID is limited, but findings from studies on patients with eating disorders estimate ARFID rates between 5%2 and 23%.3 Notably, ARFID appears to be most common in young males and more strongly associated with co-occurring conditions than are other eating disorders. One study on young patients with ARFID, for example, found that 33% had a mood disorder; 72% had anxiety; and 13% were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. 3

3

In my view, the extreme eating behaviors in ARFID are sensory processing disorder symptoms. (Maybe one manifestation of SPD is quietly in the DSM-5 after all.) If you see your child in this description, get professional help. Parents of those with ARFID are usually as frustrated and discouraged as the children they are trying to help.

Picky Eating and Feeding Difficulties: Solutions

Parents can take small daily steps to better fulfill a child’s nutritional needs and reduce stress around meals. Serious feeding difficulties and eating problems warrant professional help. Occupational therapists, speech therapists, nutritionists, GI specialists, and psychologists are several of the professionals who can help evaluate and treat youngsters that resist your best efforts.

1. Assess the Severity of Sensory and/or Behavioral Challenges

These symptoms may point to challenges that require therapeutic intervention:

- Only eating one type of texture (e.

g. crunchy, mushy or foods that require limited chewing, like crackers)

g. crunchy, mushy or foods that require limited chewing, like crackers) - Avoiding food at certain temperatures (e.g. will only eat cold food)

- Exaggerated reactions to new food experiences. (e.g. vomiting and/or lengthy, explosive temper tantrums)

- Extreme sensitivity to smells

- Brand loyalty, only eating products made by a certain company. (Processed foods may have more sugar and salt to boost flavor, which can exacerbate feeding problems)

- Refusing to eat foods if small changes are made, including in the packaging or presentation

- Refusing to eat or excessive fussing over unpreferred foods on the same plate or table when eating

- Takes 45 minutes or more to finish a meal

- Is losing weight over several months (and is not overweight)

Physical and biological problems can also contribute to feeding difficulties, including:

- Reflux; esophagitis

- Allergies and aversive food reactions

- Poor digestion and gut issues including excessive gas, bloat, constipation, diarrhea, and abdominal pain

- Underdeveloped oral motor skills.

Symptoms include frequent gagging, pocketing food, takes forever to get through a meal, difficulty transitioning from baby food to solid food, drooling.

Symptoms include frequent gagging, pocketing food, takes forever to get through a meal, difficulty transitioning from baby food to solid food, drooling. - Chronic nasal congestion.

2. Keep Nutritious Foods at Home

Try not to keep any foods at home that you do not want your child to eat. That includes certain snack foods, which are designed to be extremely appealing to the senses, but often offer paltry nutritional value. (It’s easier to remove these foods than to introduce new ones.) Consider saving leftover lunch or dinner for snacks instead.

It is also better for your child to eat the same healthy meals over and over again than to try to vary meals by filling in with snack foods or different versions of white bread (such as muffins, pancakes, bagels, noodles, rolls and crackers). Find a few good foods that your child enjoys and lean into them.

Rather than make drastic changes at once, focus on one meal or time of day, like breakfast, and start on a weekend so the initial change doesn’t interfere with school and other activities. Breakfast is a good meal to tackle, as most kids are home and this meal sets the tone for the day. These tips can help make the most of the day’s first meal:

Breakfast is a good meal to tackle, as most kids are home and this meal sets the tone for the day. These tips can help make the most of the day’s first meal:

- Limit sugary, processed items like cereal, frozen waffles, breakfast pastries, and the like. These foods fuel sudden spikes and drops in your child’s energy levels through the school day. If your child also has ADHD and takes medication for it, it’s important to serve breakfast before the medicine kicks in, as stimulants can dampen appetite.

- Focus on protein. Protein provides long-lasting energy and fullness. A protein-rich breakfast can include eggs, smoothies, paleo waffles, salmon, hummus, beans and nut butters.

- Think outside of the box. Breakfast doesn’t have to look a certain way. Leftover dinner can be an excellent meal to start the day.

3. Consider Supplements

Nutritional deficiency is a common outcome of restricted, picky eating. These deficiencies can impact appetite and mood and, in the severe cases, exact long-term consequences on development and functioning. Vitamins, minerals, and other supplements can close the gap on these deficiencies while you work with your child on eating a more varied diet.

These deficiencies can impact appetite and mood and, in the severe cases, exact long-term consequences on development and functioning. Vitamins, minerals, and other supplements can close the gap on these deficiencies while you work with your child on eating a more varied diet.

Among the body’s many required nutrients, zinc appears to have the greatest impact on feeding difficulties, as poor appetite is a direct symptom of zinc deficiency. Insufficient zinc intake is also associated with altered taste and smell, which can impact hunger signals and how your child perceives food. Zinc is found in meat, nuts, oysters, crab, lobster, and legumes. “White” foods like milk and rice are not rich in zinc.

4. Stay Calm and Carry On

Family collaboration can play an important role in addressing picky eating and reducing stress around new foods. Even if only one person in the family has feeding difficulties, ensure that everyone is following the same plan for creating and maintaining a positive, cooperative environment at home.

How to Introduce New Foods

- Concentrate on one food at a time to reduce overwhelm. Give your child a limited set of new food options from which to choose. Consider keeping a kid-friendly food chart in the kitchen. If your child won’t choose, pick one for them.

- Introduce one bit of the same food for at least two weeks. Repetition is a sure way to turn a “new” food into a familiar one. Sensory processing issues means new things are bad things, because new means more potentially overwhelming data to read and sort.

- Do not surprise your child – make sure they know what’s coming.

- Offer choices that are similar to foods they already eat. If your child likes French fries, consider introducing sweet potato fries. If they like crunchy foods, consider freeze-dried fruits and vegetables. If they like salty and savory flavors, try preparing foods with this taste in mind.

- Set up natural consequences using when:then to increase buy-in and avoid the perception of punishment.

Say, “When you finish this carrot, then you can go back to your video game.” As opposed to, “if you don’t eat your carrot, you can’t play your game.”

Say, “When you finish this carrot, then you can go back to your video game.” As opposed to, “if you don’t eat your carrot, you can’t play your game.”

No matter the plan or your child’s challenges, stay calm in the process. Losing your temper can cause your child to do the same (especially if they are sensory sensitive) and create undue stress around an already tough situation:

- Start with the assumption that you and your child will be successful

- Explain expectations in simple terms

- It’s OK if your child fusses, gags, and complains about a new food in the beginning

- Give yourself time-outs when needed

- Always keep feedback positive

Picky Eating Problems: Next Steps

- Download: Best Vitamins and Supplements for People with ADHD

- Symptom Test: Sensory Processing Disorder in Children

- Read: The Parent’s Guide to Mealtime with Picky Eaters

The content for this article was derived from the ADDitude Expert Webinar Got a Picky Eater? How to Solve Unhealthy Food Challenges in Children with SPD and ADHD [podcast episode #355] with Kelly Dorfman, M. S., LND, which was broadcast live on May 18, 2021.

S., LND, which was broadcast live on May 18, 2021.

SUPPORT ADDITUDE

Thank you for reading ADDitude. To support our mission of providing ADHD education and support, please consider subscribing. Your readership and support help make our content and outreach possible. Thank you.

View Article Sources

1 Brigham, K. S., Manzo, L. D., Eddy, K. T., & Thomas, J. J. (2018). Evaluation and Treatment of Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) in Adolescents. Current pediatrics reports, 6(2), 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40124-018-0162-y

2 Norris, M. L., Robinson, A., Obeid, N., Harrison, M., Spettigue, W., & Henderson, K. (2014). Exploring avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in eating disordered patients: a descriptive study. The International journal of eating disorders, 47(5), 495–499. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22217

3 Nicely, T. A., Lane-Loney, S., Masciulli, E., Hollenbeak, C. S., & Ornstein, R. M. (2014). Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a cohort of young patients in day treatment for eating disorders. Journal of eating disorders, 2(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-014-0021-3

A., Lane-Loney, S., Masciulli, E., Hollenbeak, C. S., & Ornstein, R. M. (2014). Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a cohort of young patients in day treatment for eating disorders. Journal of eating disorders, 2(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-014-0021-3

Previous Article Next Article

90,000 eating disorders (table) nervous

anorexia

nervous

Bulimia

BINGEE EATING (VE) Epivocious Overhaul

Obesity no disorder

eating disorder

F 50.0,50.1

restrictive type

Cleaning type

F 50. 2

2

In diagnostics and

Planning

therapy-the level of

violations is more significant, and

NOT a picture of the disorder

DSM-5

was allocated as a separate disorder

in ICDS in ICD 10 BE

presented:

F50.9

indeterminate

eating disorder ,

F50.3.

atypical bulimia

Atypical anorexia, Temporary instability of clinical syndromes, a change in clinical signs of weight of the body (IMT ) low Body weight (BMI) normal, Body weight (BMI) high, Body weight (BMI) low, Body weight (BMI) high restrictions (denial) in nutrition, a special way of handling food, significant loss of body weight and an overwhelming fear of obesity and any weight gain. Bulimia nervosa is characterized by recurrent bouts of binge eating and measures to compensate for the fattening effect of food eaten. Binge eating (BE) is characterized by attacks during which a person loses control over the amount eaten. He eats unusually quickly and unusually much, most often secretly from others, after which he experiences a feeling of shame and self-loathing. It is common for this disorder to eat before symptoms of nausea and heaviness in the stomach appear, often in a state of mental distress. Cases of "overeating" are characterized by the fact that the amount of food consumed in a certain period of time is more than most people are able to eat during a similar period in a similar situation. Atypical anorexia and bulimia: Anorexia and bulimia with insufficient symptoms for a diagnosis. Compulsive overeating is characterized by the following symptoms: Regular bouts of increased appetite. Eating is often accompanied by a loss of control. As a result, more food is consumed than necessary. And, accordingly, excess weight is gained. Difficulty with satiety, a measure of food intake. The need to "chew and gnaw" without feeling physiological hunger. Predisposing factors for obesity: Summary of the differential diagnosis BE differs from pure obesity in the following ways: Summary of differential diagnosis BE differs from 9002 in the following ways: 9002: No regular compensatory behaviors In general, more heterogeneous client groups in relation to socio-demographic and psychopathological characteristics. Summary of Differential Diagnosis Mood disorders. Obsessive-compulsive. Depression. Violation of impulse control. The use of psychoactive substances. PTSD. Anxiety disorders. affective disorders. DIAGNOSIS AND TARGETS OF THERAPY Part II Tatyana Nazarenko Eating disorders include anorexia, bulimia and binge eating. As well as the so-called non-specific disorders. These include compulsive overeating, purging disorder, night eating syndrome, atypical anorexia, and bulimia. In the process of therapy, attention from the weight and shape of the body is refocused on inner experiences and one's own personality. For binge clients, this is less of an issue, but for those with an eating disorder (who are more likely to focus on body shape and weight), this shift reduces anxiety and builds resilience. If the client is really interested in the inner world and has regular therapy, the need for countermeasures is greatly reduced. (For anorexia and bulimia, this may be vital). It is worth noting that in working with bulimia and Binge Eating, stability, "grounding", and calmness of the therapist are especially important. Anxiety and tension bring these clients back to their usual way of organizing the experience. In Binge Eating, the conscious self is felt to be weak and helpless. The polar experience of strength and security is assigned to that part of the body, to those kilograms that they want to get rid of. In Binge Eating, the conscious self is felt to be weak and helpless. If a stabilizing and protective function is not provided, the client is likely to remain closed, hiding his vulnerability, and will try to take care of the therapist, to take control of the situation. One of the main reasons for not supporting the "weight loss" request is that the protective power is projected onto the bodily forms. Without extra pounds, the vulnerability is too exposed, there is a need to “build them up” again. However, if cooperation with a nutritionist is not available for any reason, a psychologist, psychotherapist can master and implement an individual nutrition plan in work with a client. Customers with bulimia not as stabilized as with Binge Eating. They tend to insatiably seek contact, then sharply and unexpectedly reject it. And no matter what pole a person appears in the session, the task of the therapist is to return another one to him. It is important not to intrude or withdraw, but to be present, to help to be aware of these polarities. Support in seeking opportunities for intimacy without losing individuality. Develop the ability to approach and withdraw despite the fear of destruction of relationships, absorption and rejection. In long-term therapy for bulimia and binge eating, the place of impulsivity and acting out is gradually replaced by reflection, the opportunity to meet feelings and verbalization. It is important to return the opportunity to comprehend what is happening with the client and to help form their own assessment of their behavior and personal selection criteria . Psychogenic overeating Emotional binge eating is not an eating disorder. Rather, it is a way of satisfying needs through food. It is especially common in binge eating and compulsive overeating. During psychogenic transdation, the need for is not explicit for the client Food , Situation Providing hunger so and remains unfinished . Satisfaction is short -term , and as , Pucking will acquire 9000 During psychogenic transdation, the need for is compensated for Food , 9000 incomplete . Awareness of the "jammed" need, as well as avoided emotions (often anger, anger, despair, sadness) makes it possible to satisfy and experience them without the help of food substitutes. Body image Clients with eating disorders have a negative subjective perception of their body . As a rule, this is a consequence of the reactions of others and their assessment of the body, comparison with others, with an ideal image (especially in adolescence), experience of violence. Such work, among other things, makes it possible to realize the resources "here and now", to notice oneself in a new way, and not postpone life for "there and then", when the body will correspond to the symbol of a successful and worthy person. Working with negative body image requires trust. Since there is quite a lot of shame and vulnerability in this aspect. It is more likely to be acquired in a long-term closed therapy group or in a long-term individual therapy option Ability K Regulation affects and Ambassy . When planning therapy for a person suffering from an eating disorder, special attention should be paid to the ability to cope with impulses and self-comfort. In repetitive behavior, in the exhaustion of the body by mechanical, automatic behavior with monotonous actions, and especially in compensation, techniques are used by which a person achieves temporary peace, but not satisfaction. Sometimes one process can replace another, as long as it remains at the behavioral level. Such self-soothing processes indicate that a person is in a state of regression from the level of the psyche to the level of behavior. That the system of protection against despair is damaged. Such self-soothing processes indicate that a person is in a state of regression from the level of the psyche to the level of behavior. That the system of protection against despair is damaged. It is also presumed that the introjection of the positive experience of alleviating the fears of her child by the comforting mother was partial or did not occur at all. A person who is completely overwhelmed by self-soothing, compulsively repetitive behavior can be difficult to establish a connection with, and it is difficult for him to make contact and talk about what is happening to him. output voltage . This is , which will be Improve Quality Life and will be less than 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000.

atypical bulimia, compulsive

overeating, cleansing disorder,

Night Syndrome

9000

high

rarer normal

normal, high

stages of anorexia. Ideas about being overweight, dieting, other weight loss measures (vomiting, laxatives, diuretics, enemas, exercise), slight weight loss. Perhaps the use of antidepressants that suppress appetite. Fixation on the idea of fullness, fasting is hidden, countermeasures are more intense, it is possible to form dependence on diuretic or laxative medicines. Rubicon - amenorrhea.

stages of anorexia. Ideas about being overweight, dieting, other weight loss measures (vomiting, laxatives, diuretics, enemas, exercise), slight weight loss. Perhaps the use of antidepressants that suppress appetite. Fixation on the idea of fullness, fasting is hidden, countermeasures are more intense, it is possible to form dependence on diuretic or laxative medicines. Rubicon - amenorrhea.

Lack of appetite, aversion to food develops. The phenomena of dystrophy begin. Catastrophic deterioration of the somatic condition. No criticism . Restrictive type: restriction in food intake, while not reaching the feeling of fullness. Next, inducing vomiting. Cleansing type:

Regular overeating or eating until you feel full with loss of control. This is followed by the intensive use of countermeasures (inducing vomiting, taking laxatives, diuretics, etc.).

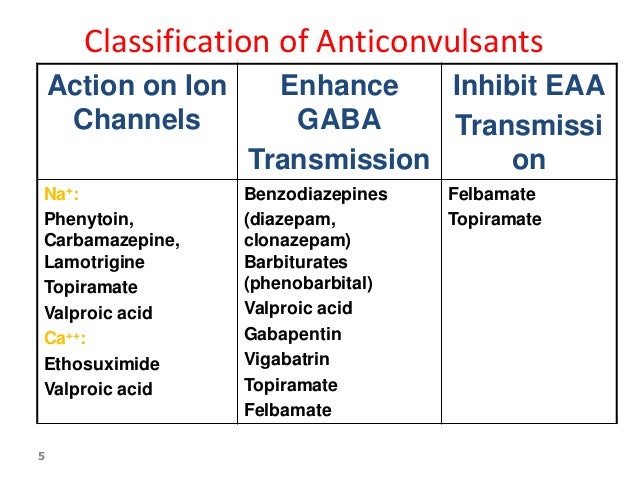

Accompanied by excessive concern and control of body weight. The main diagnostic signs of bulimia. Excessive preoccupation with food and an irresistible craving for food. Uncontrolled overeating of large amounts of food. Active use of countermeasures: self-induced vomiting, abuse of laxatives, diuretics, use of appetite suppressants, alternate periods of fasting, exhausting exercise.

Accompanied by excessive concern and control of body weight. The main diagnostic signs of bulimia. Excessive preoccupation with food and an irresistible craving for food. Uncontrolled overeating of large amounts of food. Active use of countermeasures: self-induced vomiting, abuse of laxatives, diuretics, use of appetite suppressants, alternate periods of fasting, exhausting exercise.

Accompanied by a morbid fear of obesity. Often the desired weight limit is below the normal body mass index.  And there is no sense of control over food during an attack. In cases of "attacks of hunger" food intake occurs much faster than usual, to the point of an unpleasant feeling of heaviness; a large amount of food is consumed even in the absence of physical hunger. Eating occurs in solitude due to confusion about the amount of food. After overeating, feelings of self-loathing, depression, or intense guilt.

And there is no sense of control over food during an attack. In cases of "attacks of hunger" food intake occurs much faster than usual, to the point of an unpleasant feeling of heaviness; a large amount of food is consumed even in the absence of physical hunger. Eating occurs in solitude due to confusion about the amount of food. After overeating, feelings of self-loathing, depression, or intense guilt.

"Hunger attacks" are not associated with the regular use of inappropriate compensatory behavior and cause obvious distress.  History of diets/failures and weight fluctuations. As well as a significant influence of body shape and weight on self-esteem and the quality of social contacts. Purging disorder: repetitive episodes of purging behavior to regulate body shape and weight. Fear of gaining weight. compensatory behavior. Night Eating Syndrome: An increased amount of food consumed after dinner or at night (more than 25% of the daily food intake). Decreased quality of life. Morning anorexia.

History of diets/failures and weight fluctuations. As well as a significant influence of body shape and weight on self-esteem and the quality of social contacts. Purging disorder: repetitive episodes of purging behavior to regulate body shape and weight. Fear of gaining weight. compensatory behavior. Night Eating Syndrome: An increased amount of food consumed after dinner or at night (more than 25% of the daily food intake). Decreased quality of life. Morning anorexia.

- Sedentary lifestyle.

- Genetic factors.

- Certain diseases, in particular endocrine diseases.

- Tendency to stress.

- Lack of sleep.

- Psychotropic drugs.

➢ Frequent episodes of severe hunger

➢ Early onset and more severe obesity, frequent weight fluctuations

➢ Clinically significant over-attention to body shape and weight

➢ High prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders

➢ Eating disorders

➢ Overeating

➢ Subjective experience of binge eating: BE clients may enjoy but tension follows

➢ Late onset

➢ Large body weight

➢ High proportion of affected males

Purging anorexia differs from bulimia in the following ways:

➢ Lower body weight, lower BMI

➢ Often earlier onset

Greater ability to regulate impulses.

Personality disorders.

PTSD. Eating disorders. Diagnosis and Targets of Therapy

psychologist, psychotherapist, supervisor

The polar experience of strength and security is assigned to that part of the body, to those kilograms that they want to get rid of.

The polar experience of strength and security is assigned to that part of the body, to those kilograms that they want to get rid of.

Secondly, to try new ways of stabilizing, overcoming, approaching not through food and talking about it (which is habitual and under control), but somehow differently.  This part of the work will be aimed at structuring eating behavior and stabilizing the condition.

This part of the work will be aimed at structuring eating behavior and stabilizing the condition.

Satisfaction turns out to be short-term , and as Condition , Pucking will acquire Building Character .

Satisfaction turns out to be short-term , and as Condition , Pucking will acquire Building Character .

The negative body image formed in this way determines behavior, thoughts and feelings. This leads to the rejection of social contacts, hiding one's own body, avoiding movements and prying eyes. It entails shame, anger, sadness, fear, disappointment. The value of a person as a whole begins to depend on the appearance and weight of the body.

The negative body image formed in this way determines behavior, thoughts and feelings. This leads to the rejection of social contacts, hiding one's own body, avoiding movements and prying eyes. It entails shame, anger, sadness, fear, disappointment. The value of a person as a whole begins to depend on the appearance and weight of the body.

With prolonged anorexic behavior, it is extremely difficult to open it. In addition, structural changes in the brain as a result of the disease remain. Accordingly, there is no criticism of the state. Therefore, in working with clients suffering from anorexia, work with body image has a character that supports their idea. At least at the beginning.

The task that can be agreed upon is to maintain the weight and shape of the body at a level compatible with life. It will also be effective to compensate for anxiety and depressive states to reduce dysmorphic symptoms and a more positive perception of oneself. Accordingly, the earlier (as a rule, parents) turn to a specialist, the greater the chances for restoring the mental and somatic health of the client.

We can also assume that such a client is highly dependent on the actions of other people. In this connection, non-integrable excitement and actualization of experiences associated with traumatic experience will systematically provoke obsessive self-consolation.

Learn more