Phineas gage case

The Curious Case of Phineas Gage's Brain : Shots

The Curious Case of Phineas Gage's Brain : Shots - Health News In 1848, a railroad worker survived an accident that drove a 13-pound iron bar through his head. The injury changed his personality, and our understanding of the brain.

Your Health

Heard on Weekend Edition Sunday

Why Brain Scientists Are Still Obsessed With The Curious Case Of Phineas Gage

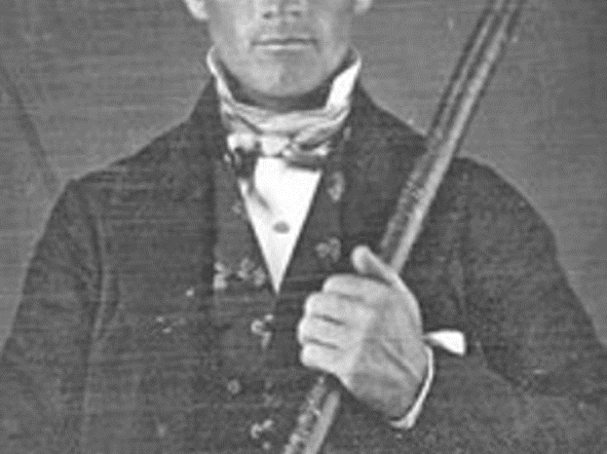

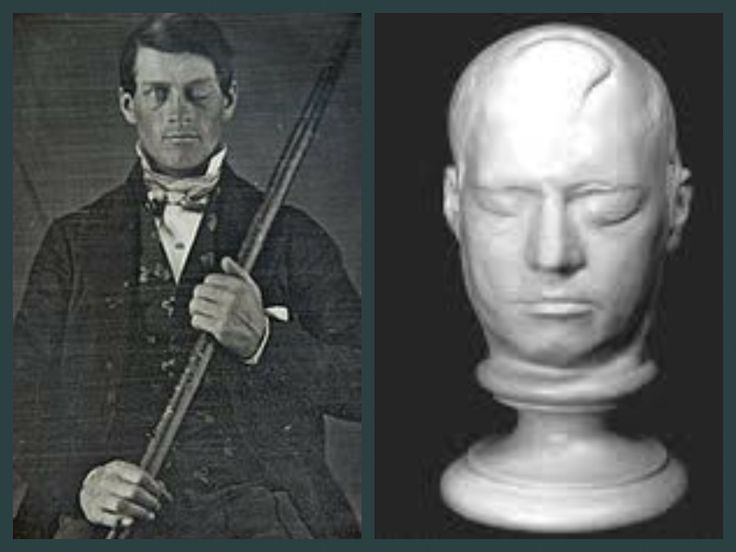

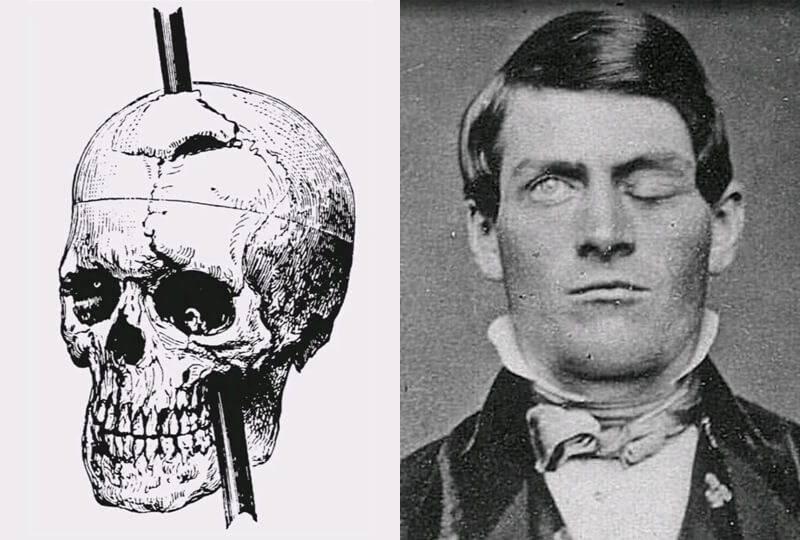

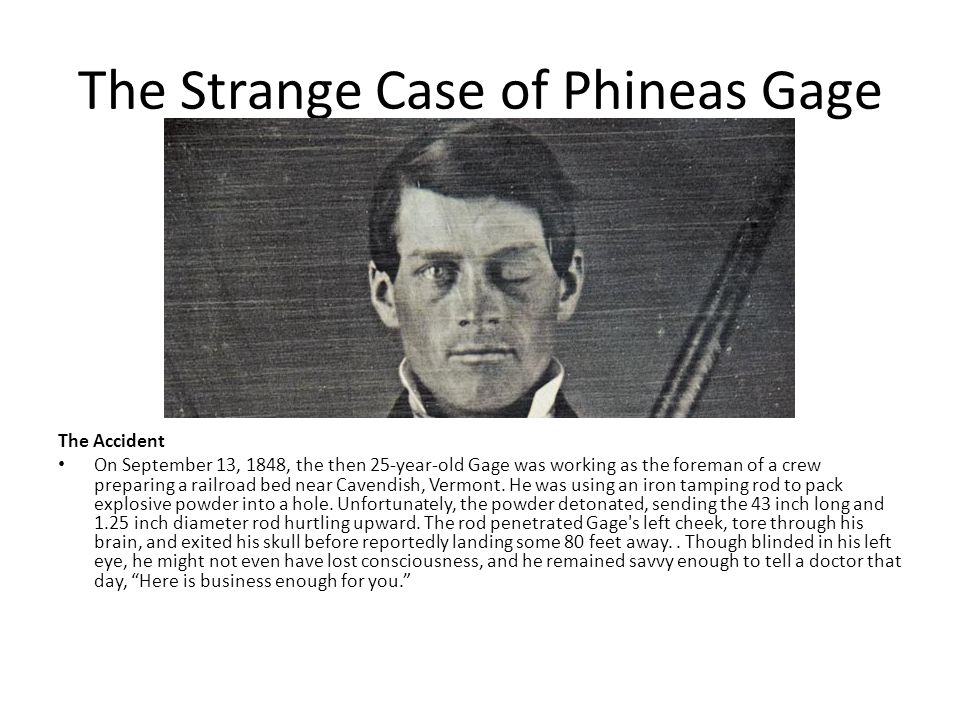

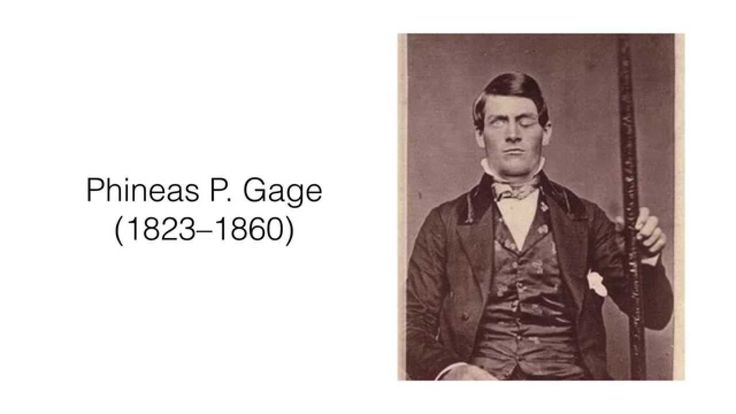

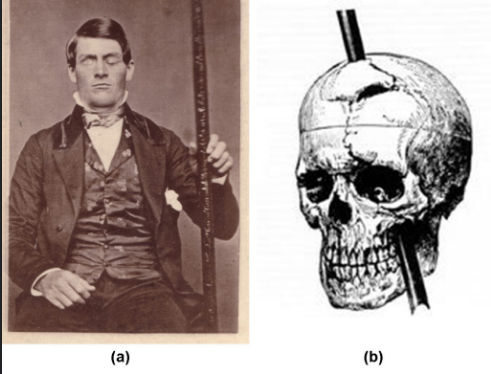

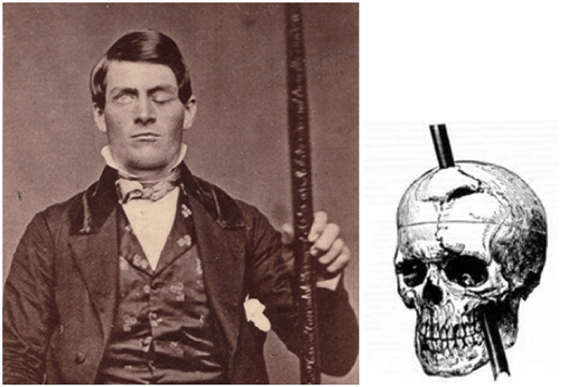

Cabinet-card portrait of brain-injury survivor Phineas Gage (1823–1860), shown holding the tamping iron that injured him. Wikimedia hide caption

toggle caption

Wikimedia

Cabinet-card portrait of brain-injury survivor Phineas Gage (1823–1860), shown holding the tamping iron that injured him.

Wikimedia

It took an explosion and 13 pounds of iron to usher in the modern era of neuroscience.

In 1848, a 25-year-old railroad worker named Phineas Gage was blowing up rocks to clear the way for a new rail line in Cavendish, Vt. He would drill a hole, place an explosive charge, then pack in sand using a 13-pound metal bar known as a tamping iron.

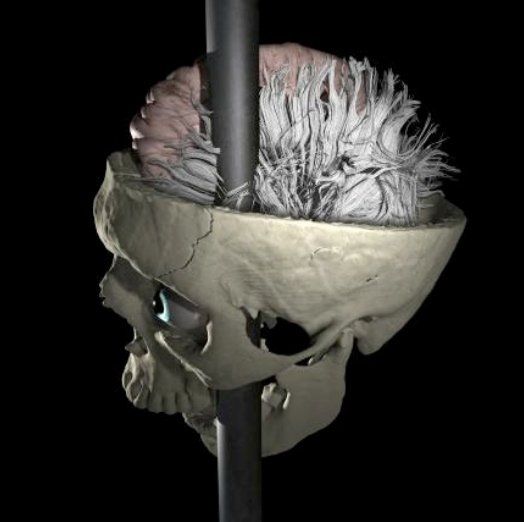

But in this instance, the metal bar created a spark that touched off the charge. That, in turn, "drove this tamping iron up and out of the hole, through his left cheek, behind his eye socket, and out of the top of his head," says Jack Van Horn, an associate professor of neurology at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California.

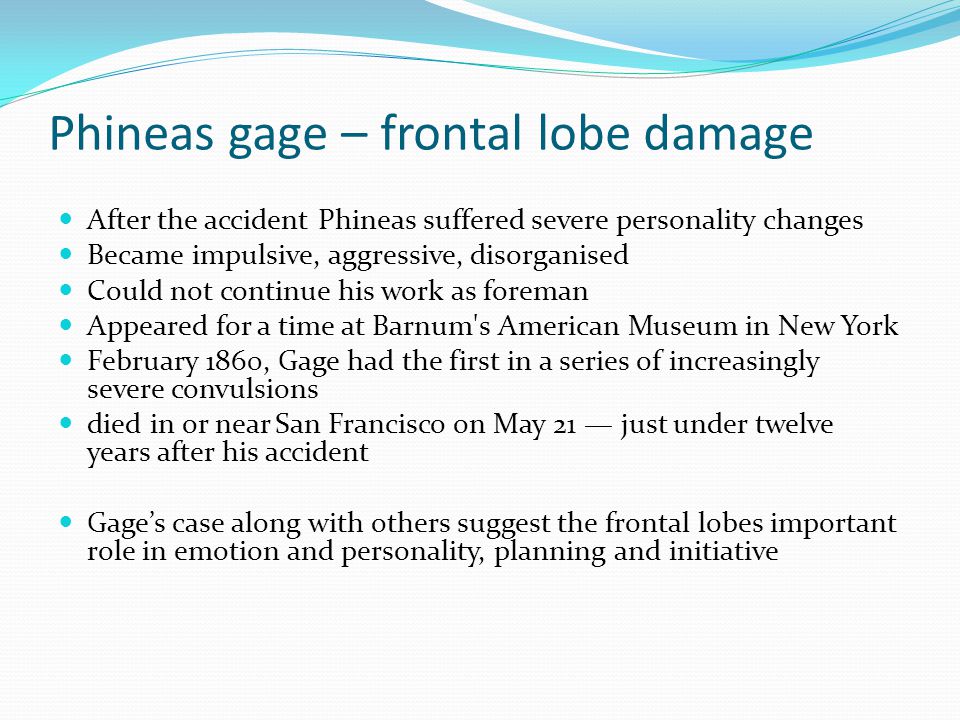

Gage didn't die. But the tamping iron destroyed much of his brain's left frontal lobe, and Gage's once even-tempered personality changed dramatically.

"He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity, which was not previously his custom," wrote John Martyn Harlow, the physician who treated Gage after the accident.

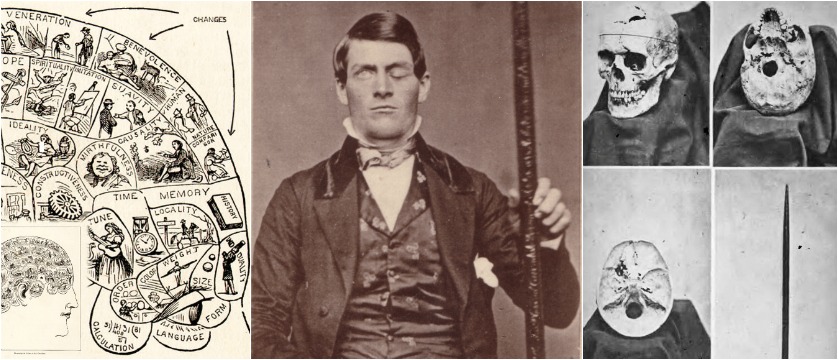

This sudden personality transformation is why Gage shows up in so many medical textbooks, says Malcolm Macmillan, an honorary professor at the Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences and the author of An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage.

"He was the first case where you could say fairly definitely that injury to the brain produced some kind of change in personality," Macmillan says.

And that was a big deal in the mid-1800s, when the brain's purpose and inner workings were largely a mystery. At the time, phrenologists were still assessing people's personalities by measuring bumps on their skull.

Gage's famous case would help establish brain science as a field, says Allan Ropper, a neurologist at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital.

Dr. John Harlow, who treated Gage following the accident, noted his personality change in an 1851 edition of the American Phrenological Journal and Repository of Science.

The American Phrenological Journal and Repository of Science, Literature and General Intelligence, Volumes 13-14

The American Phrenological Journal and Repository of Science, Literature and General Intelligence, Volumes 13-14

"If you talk about hard core neurology and the relationship between structural damage to the brain and particular changes in behavior, this is ground zero," Ropper says. It was an ideal case because "it's one region [of the brain], it's really obvious, and the changes in personality were stunning."

It was an ideal case because "it's one region [of the brain], it's really obvious, and the changes in personality were stunning."

So, perhaps it's not surprising that every generation of brain scientists seems compelled to revisit Gage's case.

For example:

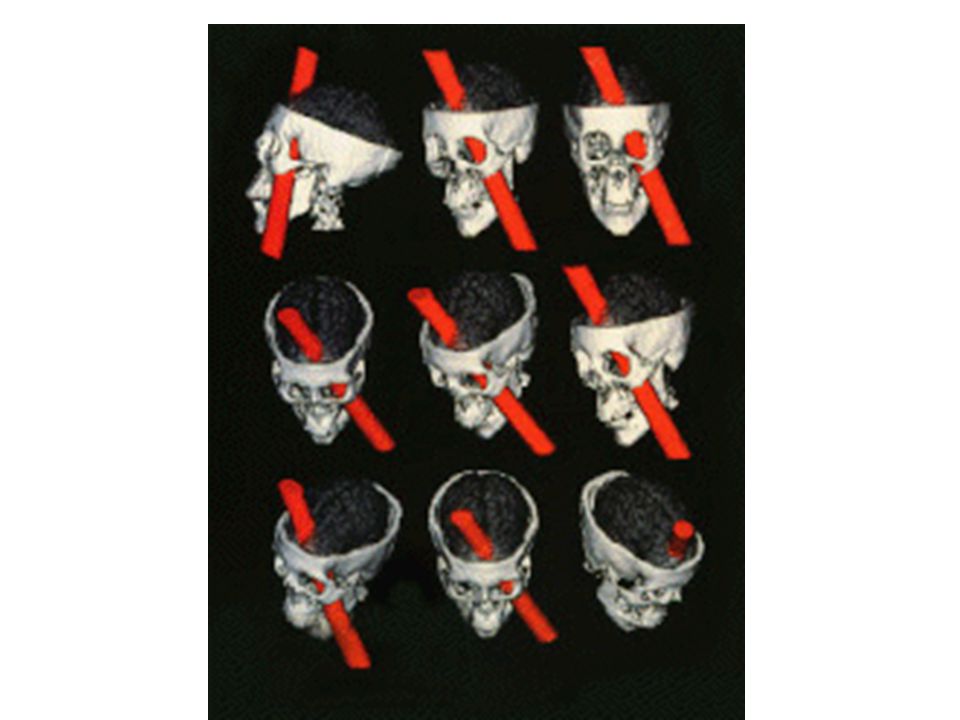

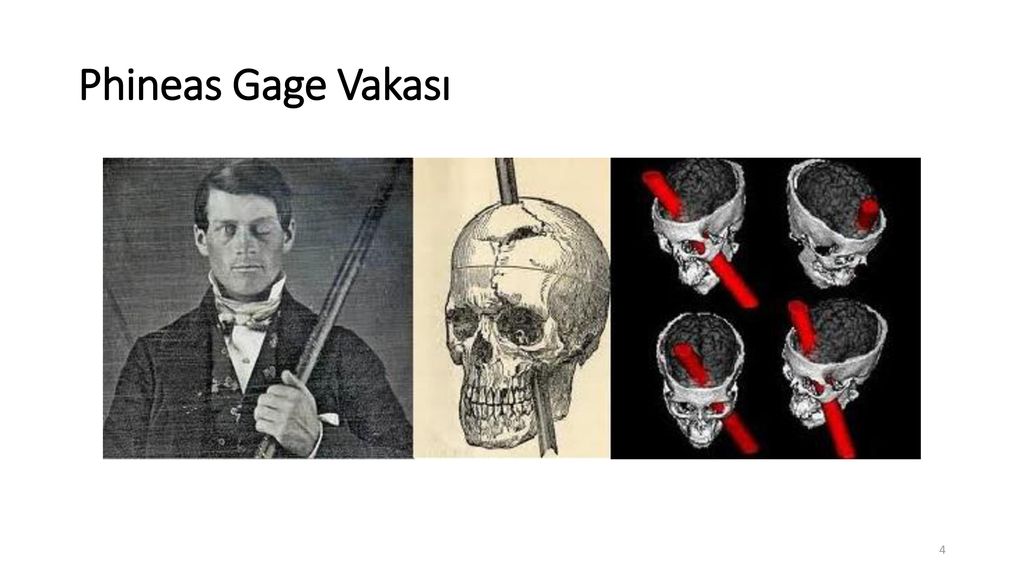

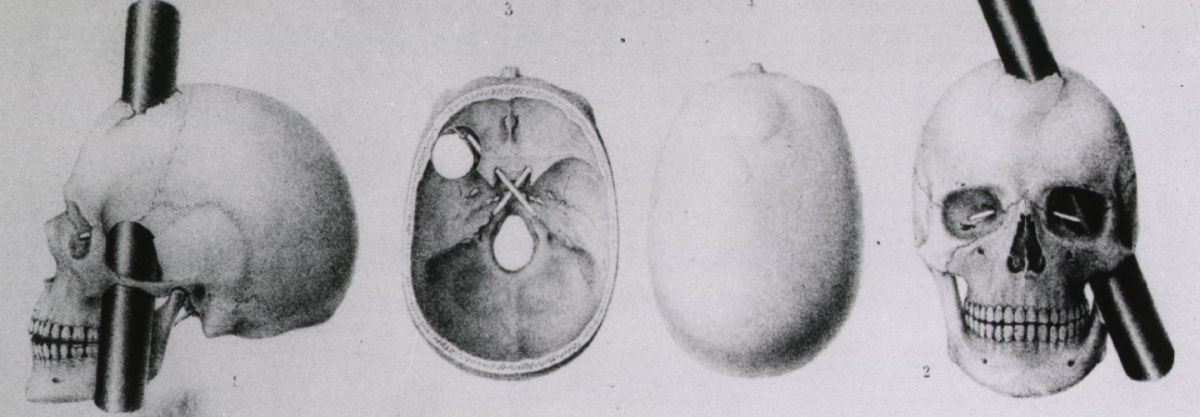

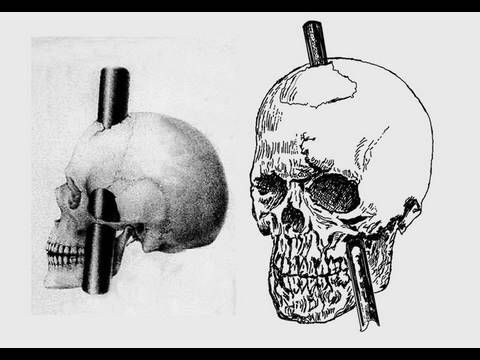

- In the 1940s, a famous neurologist named Stanley Cobb diagrammed the skull in an effort to determine the exact path of the tamping iron.

- In the 1980s, scientists repeated the exercise using CT scans.

- In the 1990s, researchers applied 3-D computer modeling to the problem.

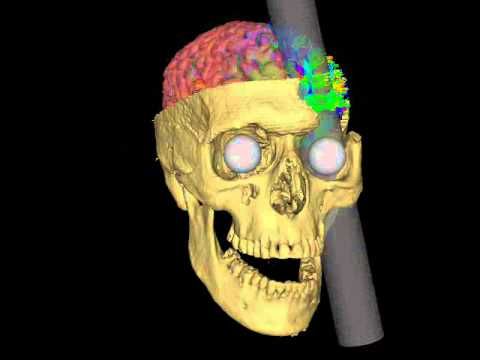

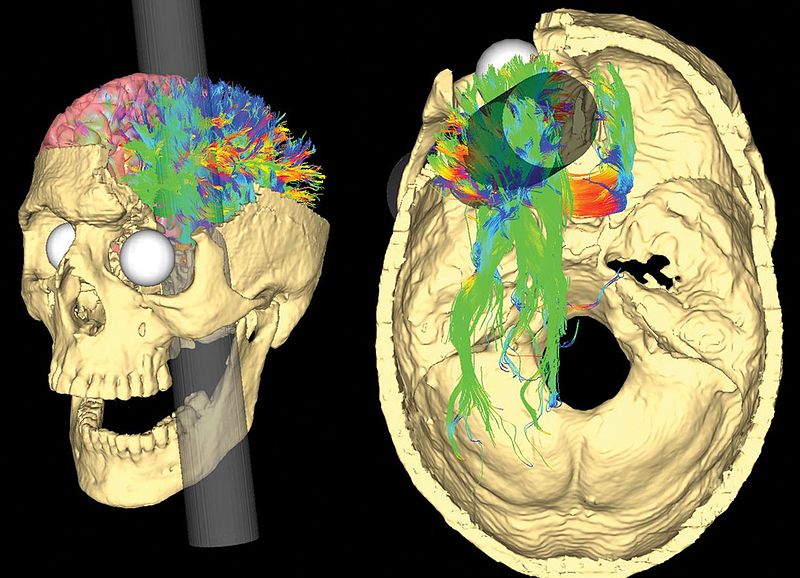

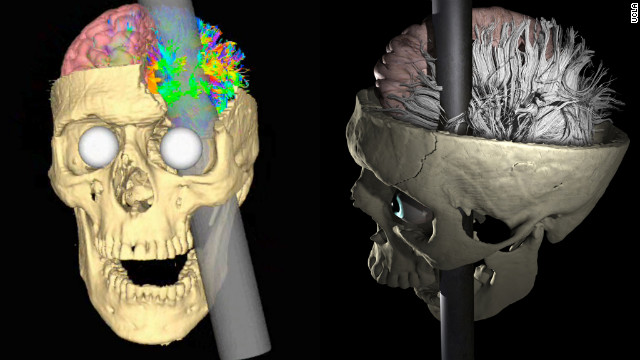

And, in 2012, Van Horn led a team that combined CT scans of Gage's skull with MRI scans of typical brains to show how the wiring of Gage's brain could have been affected.

"Neuroscientists like to always go back and say, 'we're relating our work in the present day to these older famous cases which really defined the field,' " Van Horn says.

And it's not just researchers who keep coming back to Gage. Medical and psychology students still learn his story. And neurosurgeons and neurologists still sometimes reference Gage when assessing certain patients, Van Horn says.

Medical and psychology students still learn his story. And neurosurgeons and neurologists still sometimes reference Gage when assessing certain patients, Van Horn says.

"Every six months or so you'll see something like that, where somebody has been shot in the head with an arrow, or falls off a ladder and lands on a piece of rebar," Van Horn says. "So you do have these modern kind of Phineas Gage-like cases."

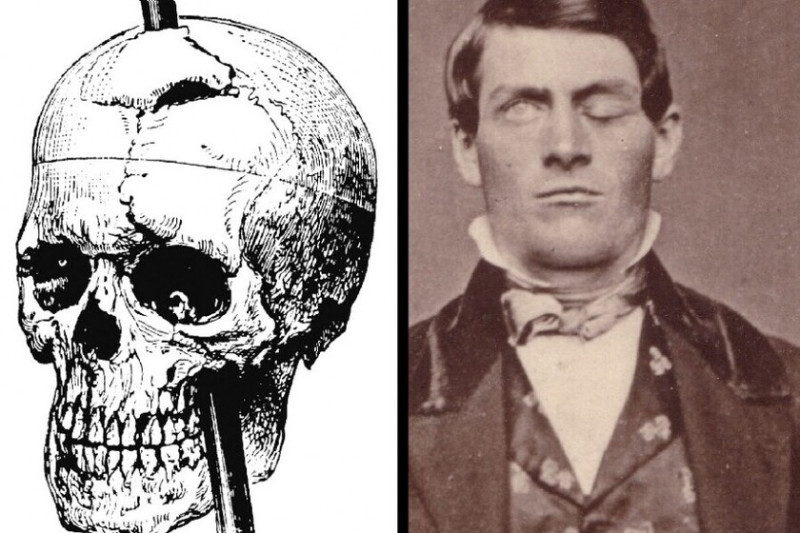

Two renderings of Gage's skull show the likely path of the iron rod and the nerve fibers that were probably damaged as it passed through. Van Horn JD, Irimia A, Torgerson CM, Chambers MC, Kikinis R, et al./Wikimedia hide caption

toggle caption

Van Horn JD, Irimia A, Torgerson CM, Chambers MC, Kikinis R, et al. /Wikimedia

/Wikimedia

Two renderings of Gage's skull show the likely path of the iron rod and the nerve fibers that were probably damaged as it passed through.

Van Horn JD, Irimia A, Torgerson CM, Chambers MC, Kikinis R, et al./Wikimedia

There is something about Gage that most people don't know, Macmillan says. "That personality change, which undoubtedly occurred, did not last much longer than about two to three years."

Gage went on to work as a long-distance stagecoach driver in Chile, a job that required considerable planning skills and focus, Macmillan says.

This chapter of Gage's life offers a powerful message for present day patients, he says. "Even in cases of massive brain damage and massive incapacity, rehabilitation is always possible."

Gage lived for a dozen years after his accident. But ultimately, the brain damage he'd sustained probably led to his death.

He died on May 21, 1860, of an epileptic seizure that was almost certainly related to his brain injury.

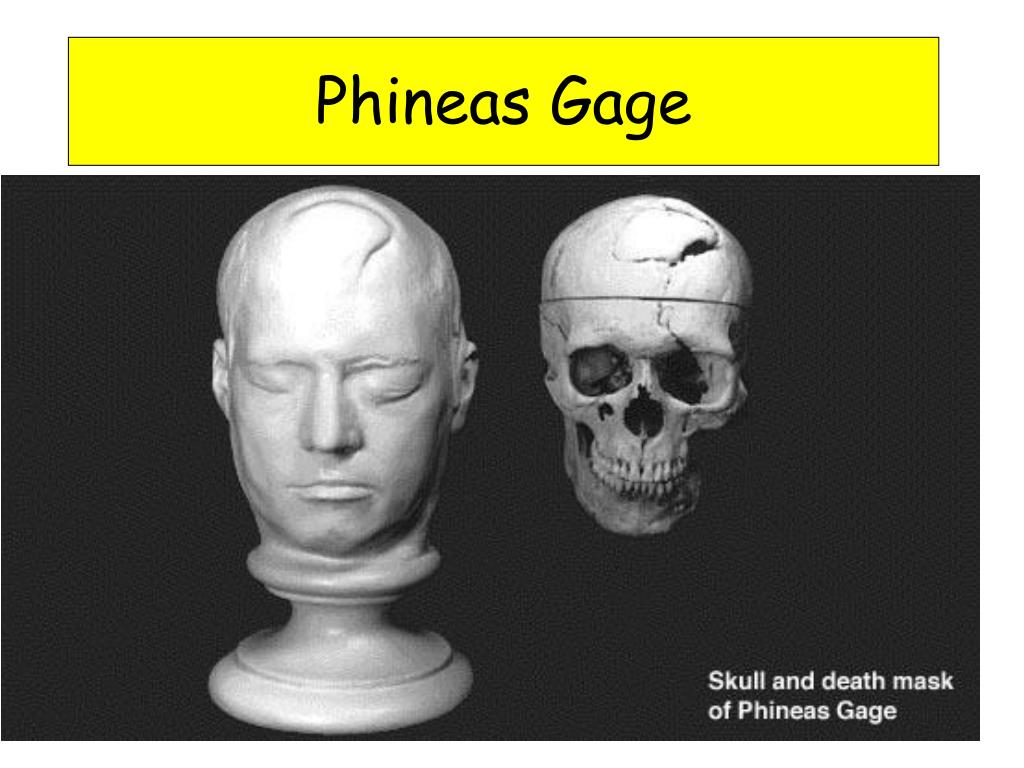

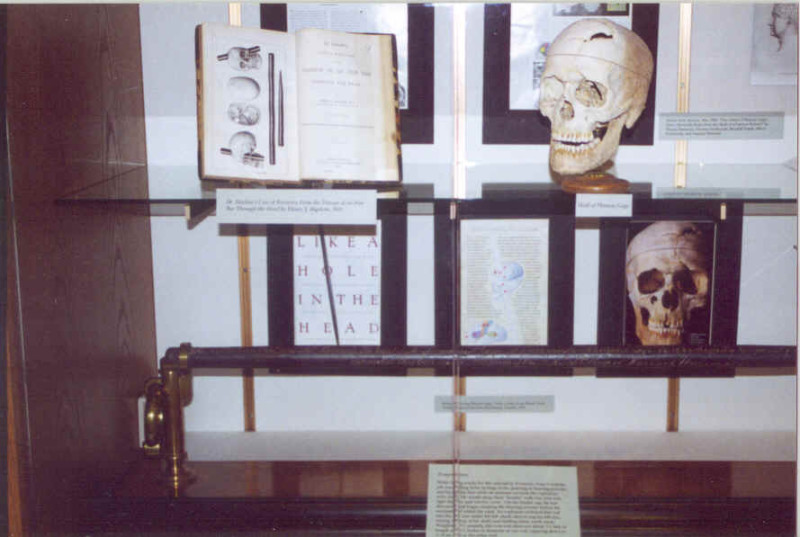

Gage's skull, and the tamping iron that passed through it, are on display at the Warren Anatomical Museum in Boston, Mass.

Sponsor Message

Become an NPR sponsor

The University of Akron, Ohio

The Phineas Gage case made an important but indirect contribution to the development of brain surgery. Although there had been operations for abscesses of the brain before 1885, it was in that year that the first brain surgery for the removal of a tumour was carried out. What made this and later operations possible were aseptic methods of operating and knowledge of where some of the functions of the brain were localised. It was to this latter that the Gage case contributed.

By about that time, in 1884, the American neurologist, M. Allan Starr, had collected the first large series of cases in which injury or damage to reasonably distinct areas of the brain could be related to particular symptoms. His cases included a number in which there was injury to or tumours of the frontal lobes. Starr's comparisons began with the frontal lobes and actually used Gage as a standard. As he said:

Starr's comparisons began with the frontal lobes and actually used Gage as a standard. As he said:

"Lesions affecting the three frontal convolutions may be classed together. Ever since the occurrence of the famous American crowbar case it has been known that destruction of these lobes does not necessarily give rise to any symptoms. That case is given in order to compare others with it."

For Starr the absence of symptoms simply meant no impairment in Gage's ability to use his senses and to move his muscles (e.g. no paralysis). But Starr granted that there were some mental symptoms. In his summary he said that Gage's "disposition was altered, and ... he was irritable, easily excitable, and emotional." He advocated using such mental changes to diagnose frontal tumours.

Nine years later, in 1894, Starr acted on his own diagnostic recommendation. McBurney and he operated on a patient who had noticed himself gradually becoming dull in his thinking, generally weak, lazy, slow in mental activity, and unable to express his ideas reasonably quickly. Although there were also physical symptoms, his was, they claimed, "the first case ... in which operative interference has been so directly dictated by the existence of mental symptoms." They drew a direct comparison with the mental changes shown by Gage in planning the site of the operation and removed a tumour from the patient's left frontal lobe.

Although there were also physical symptoms, his was, they claimed, "the first case ... in which operative interference has been so directly dictated by the existence of mental symptoms." They drew a direct comparison with the mental changes shown by Gage in planning the site of the operation and removed a tumour from the patient's left frontal lobe.

In 1879, well before the McBurney and Starr operation, the Scots surgeon William Macewen diagnosed and operated for a tumour lying outside of the brain proper. He thought it was pressing on the left frontal lobe mainly because the patient's mental symptoms included "obscuration of intelligence, slowness of comprehension, [and] want of mental vigour." There is a very slight possibility that Macewen used knowledge of Gage in planning to operate on the frontal lobes.

However, it soon became clear that in only about half the cases of frontal tumour were there any 'mental symptoms' and only in a minority of those did the symptoms resemble Gage's. Partly for that reason these symptoms ceased to be used for planning frontal operations. At about the same time, in the early 1920's, Walter Dandy, the American brain surgeon, developed a more radical method of removing tumours. He had found that about 60% of brain tumours could not be removed because they were not sufficiently differentiated from the tissue around them. Dandy's new method removed the lobe containing the abnormal tissue.

Partly for that reason these symptoms ceased to be used for planning frontal operations. At about the same time, in the early 1920's, Walter Dandy, the American brain surgeon, developed a more radical method of removing tumours. He had found that about 60% of brain tumours could not be removed because they were not sufficiently differentiated from the tissue around them. Dandy's new method removed the lobe containing the abnormal tissue.

Radical surgery like this was not performed often and was restricted to those patients who would otherwise have died from the effects of the tumours. But, as cases accumulated, it was noted with more than a little surprise that the effects on the patient's behaviour of the removal of such large areas were minimal. This lack of effect led Dandy to make a passing comparison with Gage. By the early 1930's, a number of such radical frontal operations had been performed, and it is noticeable that Gage seems to be mentioned only once, again in passing, in the discussions of them. (See also 'Gage and lobotomy' on this site).

(See also 'Gage and lobotomy' on this site).

What seems to have happened in the history of brain surgery is that 'mental symptoms,' supposedly resembling Gage's, were first used to diagnose frontal tumours. Later, after that method was abandoned, Gage may have come into consideration when the operations for the resection of whole lobes were developed. His surviving his injury may have reinforced the belief that large areas of the brain could be removed with relative impunity. It seemed that the brain could be operated on without causing death or major impairment of psychological functions.

Further reading:

Macmillan, M. (2004). Localisation and William Macewen's early brain surgery. Part I: The controversy. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 13, 297-325

Macmillan, M. (2005). Localisation and William Macewen's early brain surgery. Part II: The cases. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 14, 24-56.

famous patients. No. 1: Phineas Gage

Hippocrates, Sklifosovsky, Botkin, Pavlov - many people know great doctors, but what about their patients? Has history preserved the names of the patients? Yes, and some of them, unwittingly, influenced the development of science no less than doctors. And others in their fame even surpassed doctors. With this article, we open a cycle of five articles "Famous Patients". Let's start with the story of Phineas P. Gage - a story about a worker with a metal bar in his skull has become rumored, and we will tell you how it really happened. nine0003

Phineas Gage is remembered in textbooks and popular science books, ballads are sung about him and videos are made. Fame played a cruel joke on Gage: acquiring more and more details, his story almost turned from a scientific fact into a myth. You may have heard of an American who has completely changed after a severe brain injury - if so, you will be wondering what we really know about him.

Scrap Incident

Twenty-five year old Phineas Gage worked on a railroad. He poured explosive powder into the holes in the rock and rammed it with a metal rod. When the man was distracted, the rod struck a spark, provoked an explosion - and the piece of iron rammed through Gage's skull. Gage was immediately taken to town to see Dr. John M. Harlow. The doctor had to tinker a lot: firstly, to remove the pin, and secondly, to cure the secondary infection. A week later, the patient's condition seemed hopeless; the relatives prepared the coffin and asked Harlow to leave the patient alone. After two months, Gage started going out and soon went home. nine0003

He poured explosive powder into the holes in the rock and rammed it with a metal rod. When the man was distracted, the rod struck a spark, provoked an explosion - and the piece of iron rammed through Gage's skull. Gage was immediately taken to town to see Dr. John M. Harlow. The doctor had to tinker a lot: firstly, to remove the pin, and secondly, to cure the secondary infection. A week later, the patient's condition seemed hopeless; the relatives prepared the coffin and asked Harlow to leave the patient alone. After two months, Gage started going out and soon went home. nine0003

Journalists learned about the incident. They wrote articles for newspapers in Vermont and Boston, which were reprinted by other publications - sometimes three or four times. Relying on this fame, Gage traveled around America for some time, speaking to the public as a "live exhibition", but soon abandoned this occupation and hired himself to work at the stable. Meanwhile, Harlow described the unusual case to the professional press—and from that moment on, Phineas Gage's story took on a life of its own.

Gage found himself in the pages of textbooks, where the facts were overgrown with colorful details. In these books, Phineas did not work anywhere after the injury - he wandered, begged, traveled with a circus troupe, or could not lead an independent life at all. Some wrote that Gage lived another twenty years with a piece of iron in his skull. Everyone agreed on one thing - after the injury, the character of the man completely changed. True, there was no agreement about what these changes were: somewhere Gage became an alcoholic, somewhere an egoist, somewhere an unreliable person with problems in his sexual life. nine0003

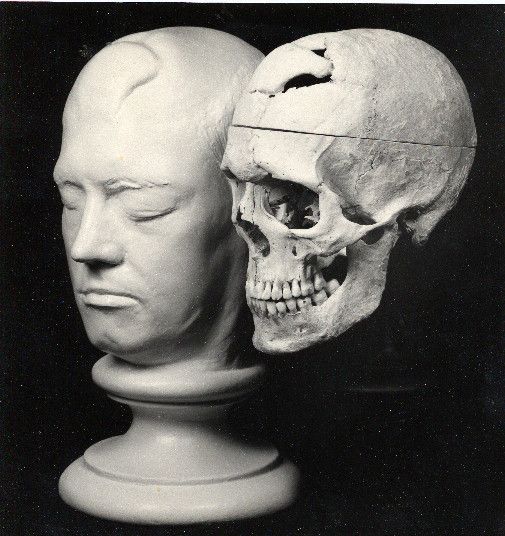

The real Phineas Gage, after working for a year and a half at the stable, went to Chile, where he became a stagecoach driver. Seven years later, he returned to his family in San Francisco due to health problems. Soon Gage began to have seizures. Now he could not find a permanent place, but he craved activity and constantly worked part-time on farms. Phineas Gage died of epilepsy in 1860. We know all this thanks to John Harlow: the doctor lost sight of the patient, but in 1866 he established contact with his mother. Two years later, the doctor published a new article. It was then, 20 years after the incident, that he spoke about how the fate and character of Gage had changed. nine0003 Photograph of Phineas Gage's skull by Dr. John Harlow. When Harlow learned of the patient's death, he had the skull exhumed and wrote an afterword article.

Now he could not find a permanent place, but he craved activity and constantly worked part-time on farms. Phineas Gage died of epilepsy in 1860. We know all this thanks to John Harlow: the doctor lost sight of the patient, but in 1866 he established contact with his mother. Two years later, the doctor published a new article. It was then, 20 years after the incident, that he spoke about how the fate and character of Gage had changed. nine0003 Photograph of Phineas Gage's skull by Dr. John Harlow. When Harlow learned of the patient's death, he had the skull exhumed and wrote an afterword article.

When Harlow first wrote about the unusual case, he was not believed. Worse, his work went largely unnoticed. Doctors got to know Phineas thanks to another specialist, the famous Boston surgeon Henry Jacob Bigelow. Bigelow invited Gage to his place, examined him and dispelled the skepticism of the scientific community. When Harlow learned of the patient's death, he secured an exhumation, examined the skull, and presented the public with a "sequel" to his article. In the first publications, there was no talk of a change in character: both Harlow and Bigelow noted that, in general, the patient recovered safely - both physically and mentally. This fact was even used as an argument in a dispute with phrenologists. nine0003

In the first publications, there was no talk of a change in character: both Harlow and Bigelow noted that, in general, the patient recovered safely - both physically and mentally. This fact was even used as an argument in a dispute with phrenologists. nine0003

Phrenology - as it turned out later, a pseudoscience - was very popular in the 40s of the 19th century. Her followers believed that the brain is divided into 27 areas, each of which is responsible for one function or property: for example, hearing, counting, language, love of life, kindness, self-esteem or hope. The more active part of the brain, the larger it is - according to phrenologists, the size could be calculated by examining the outer part of the skull. Opponents argued that the brain works as a whole: this is confirmed by the fact that Gage damaged a region of the brain, but nevertheless recovered, they said. nine0003

Twenty years later, it turned out that he had only partially recovered. According to Harlow, after the injury, Phineas became impulsive, stubborn and moody, he began to use foul language and "showed little respect for his comrades. " “A child in his intellectual abilities and manifestations, he possessed the animal passions of a strong man,” and when he came up with plans for the future, he immediately abandoned them for new, more attractive ones. “He is no longer Gage,” friends said. The change was so dramatic that previous employers who had the man in good standing decided not to contact him. Why did the doctor withhold such important details? Why wait so many years? We don't know this. We only know that doctors had to rethink the famous "crowbar case". nine0003

" “A child in his intellectual abilities and manifestations, he possessed the animal passions of a strong man,” and when he came up with plans for the future, he immediately abandoned them for new, more attractive ones. “He is no longer Gage,” friends said. The change was so dramatic that previous employers who had the man in good standing decided not to contact him. Why did the doctor withhold such important details? Why wait so many years? We don't know this. We only know that doctors had to rethink the famous "crowbar case". nine0003

Gage and Science

Phineas Gage's skull is now in the Warren Anatomical Museum at Harvard Medical School. When Harlow's second paper came out, phrenology was no longer popular. In the 1960s, the French surgeon Paul Broca discovered the "speech center", and scientists became convinced that certain areas of the brain are indeed associated with certain functions. Now Phineas Gage and his sudden change are seen in a new light. However, Harlow's new article did not cause any fundamental upheaval: too much remained unknown. Gage's brain was not preserved, and it was not possible to accurately assess the extent of the damage, and there was not enough data on the patient's mental state. nine0003

Gage's brain was not preserved, and it was not possible to accurately assess the extent of the damage, and there was not enough data on the patient's mental state. nine0003

On the other hand, the “crowbar incident”, as the incident was called in the medical press, became a kind of standard: other traumatic brain injuries were compared with it. Harlow's first article once again refuted the misconception that brain damage always leads to death - in the 40s it was not completely eliminated, although there were plenty of examples to the contrary. The history of Gage has occupied scientists for more than 150 years. And all this time, research is replenished with new details, and the picture changes as our ideas about the world change. At 1968 we learned about a change in character, in 1994 doctors reconstructed brain damage from the skull, in 2004 they clarified these data, in 2009 they found the first portrait of Phineas Gage, and in 2012 the injury was recreated, by other methods. It is unlikely that we will know what really happened to Gage, but it is likely that new exciting studies await us.

In the next issue: how the dispute about whether the brain is one or a set of centers with different functions was resolved, and what role a person who could pronounce a single syllable played in this. nine0032

Ilyinskaya Hospital - a modern outpatient hospital center :: 11 percent of the brain was taken out by an American with a crowbar. The Amazing Story of Phineas Gage.

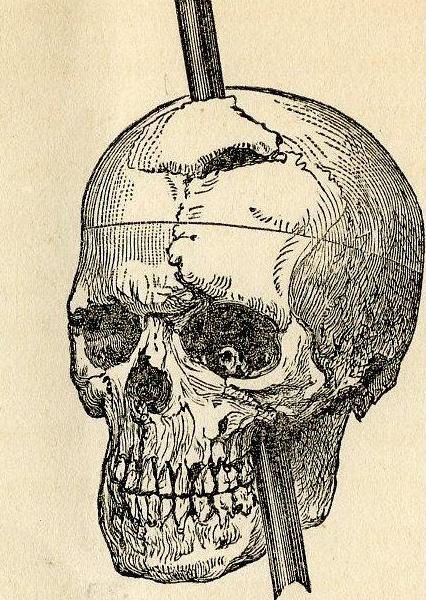

Iron rod entered Phineas Gage's head above the left cheekbone, pierced the brain, passing behind the left eye, and exited the top of the skull, breaking through the frontal bone. After that, smeared with blood and brain tissue, the tamping pin flew another 25 meters.

Phineas Gage was the eldest of five children born to farmer Jesse Eaton Gage and his wife Hannah from New Hampshire. Almost nothing is known about his early years - yes, in in general, and it doesn’t matter, because until the age of 25, when this happened to him an amazing story, Gage was of no interest to others. nine0003

nine0003

By the age of 25, this was "a perfectly healthy, strong and active young man, five feet six inches tall (168 cm) and weighing 150 pounds (68 kg), with an iron will and unusually developed muscular system, ”according to the description of the observer Dr. John Martin Harlow. At the time described, Phineas earned his living life, leading a team of workers on the construction of railways - the USA then experienced a boom in railroad construction. Gage's specialty was demolition work - even in his youth he often practiced using explosives in the mines and quarries of his native New Hampshire. This occupation was rather nervous: industrial explosives did not exist then, they had to work with black (smoky) powder. Gage developed a consistent - and how it seemed to him safe - the procedure for using explosives to laying railway tunnels in the rocks. First in hard rock a deep hole was drilled - a pit - where gunpowder was poured. Gage carefully leveled the gunpowder, after which his assistant set the fuse and poured sand or clay into the hole. Then the most crucial stage began - Gage rammed the sand with a special tamping pin, which was made according to his custom order at a forge in Cavendish, Vermont. It was iron a rod 110 cm long, 3.2 cm in diameter and weighing about 6 kg. With the help of this tool Gage formed a "cork" of viscous materials over a charge of gunpowder: as a result, the main blast wave went under the base of the rock. nine0003

Then the most crucial stage began - Gage rammed the sand with a special tamping pin, which was made according to his custom order at a forge in Cavendish, Vermont. It was iron a rod 110 cm long, 3.2 cm in diameter and weighing about 6 kg. With the help of this tool Gage formed a "cork" of viscous materials over a charge of gunpowder: as a result, the main blast wave went under the base of the rock. nine0003

Fatal for day September 13, 1848. Phineas Gage led the work brigade, tunneling for the Rutland-Burlington Railroad in Vermont. It was already evening; a charge of gunpowder was laid in the pit, but for some reason the assistant did not pour sand on top. Not knowing this, Gage went to the pit and began to carefully tamp what he considered a sand cushion, an iron rod. AT At that moment, behind his back, the workers were arguing loudly about something. Gage turned to him, leaning on a tamping pin - and already opened his mouth to call on the workers to the order, but did not have time to utter a word. Somewhere under his feet resounded a monstrous roar, a blinding flash flashed, something flew out of the pit into clubs of black smoke and flying a decent distance, crashed with a ringing on stones. nine0003

Somewhere under his feet resounded a monstrous roar, a blinding flash flashed, something flew out of the pit into clubs of black smoke and flying a decent distance, crashed with a ringing on stones. nine0003

When the smoke scattered, the workers saw that their foreman, covered in blood, was sitting on the edge shaft torn apart by the explosion. Approaching the living, but swearing at what the light is on, Gage, they were horrified to find that there was a gaping hole in his head.

As it turned out later, Gage's ramming pin struck a spark from the rock deep in the pit. If gunpowder was sealed with a sand or clay cork, nothing would have happened, but as we remember, there was neither sand nor clay in the pit that day. Gunpowder exploded pushing the iron bar on which Gage was leaning like a bullet from a barrel revolver. And the bullet hit the target. nine0003

The skull of Phineas Gage. Warren Anatomical Museum

Iron Rod entered the head of Phineas above the left cheekbone, pierced the brain, passing behind the left eye, and exited the top of the skull, breaking through the frontal bone. After that, smeared with blood and brain tissue, the tamper rod flew another 80 feet (about 25 meters)

After that, smeared with blood and brain tissue, the tamper rod flew another 80 feet (about 25 meters)

Gage remained in alive only because the blacksmith, to whom he ordered a tamping pin, made pointed at one end - so that the tool did not look like a crowbar, but rather, a spear. The tip of this spear is 27 centimeters long and 7 mm wide. passed through Phineas' skull like a needle through a sheet of paper. nine0003

Gage was shaking from pain and nervous shock - still, just flashed through his head 6 kilograms of iron - but he was alive and did not seem to be going to die. Him laid on his back in an ox-cart and taken to a nearby town, where he rented a hotel room. There and rushed caused by alarmed workers Dr. Edward H. Williams.

"When I drove up, - Williams recalled, - Mr. Gage shouted to me: “Doctor, here for you enough business!" He was sitting in a chair in the hotel garden, but I noticed a wound on his head even before he got out of the carriage. The brain pulsations were very distinct. The top of the head was a bit like an inverted funnel, as if some kind of wedge-shaped body passed from the bottom up ... While I was examining the wound, Mr. Gage told me how the accident happened. Then I didn't believe him, thinking that he had been deceived. Then Mr. Gage got up and vomited. This the effort pushed a piece of his brain the size of half a teacup through a hole in the top of the skull, and he fell to the floor…”

The brain pulsations were very distinct. The top of the head was a bit like an inverted funnel, as if some kind of wedge-shaped body passed from the bottom up ... While I was examining the wound, Mr. Gage told me how the accident happened. Then I didn't believe him, thinking that he had been deceived. Then Mr. Gage got up and vomited. This the effort pushed a piece of his brain the size of half a teacup through a hole in the top of the skull, and he fell to the floor…”

Soon to Williams was joined by Dr. Harlow, who observed Gage until the unfortunate case. Together they tried to provide Phineas with the necessary assistance. Gage was in conscious, but was rapidly losing strength due to blood loss. The whole bed which they laid him down was literally soaked in blood.

Using Williams Harlow shaved Gage's head around the wound, removed the gore, small fragments of bone and about an ounce (30 grams) of marrow, protruding above the edges of the opening in the skull. The wound was sealed with a band-aid, leaving small hole for drainage. The wound on the cheek was bandaged, on the head of the patient put on a nightcap and bandaged again. From the point of view of neurosurgery of the 21st century such manipulations look barbaric, but it should be borne in mind that the doctor Harlow was an experienced military surgeon. Among other things, Harlow ordered Gage should never lower his head and even sleep while sitting in pillows. Hours passed, and Gage, despite his terrible wound, was conscious and even showed signs of improvement. During the night, Harlow wrote in his diary: “The patient's mind is clear. Constant excitement of the legs, he bends them one by one and pulls out ... He says that he does not want to see his friends, as he will return to work in a few days. nine0003

The wound was sealed with a band-aid, leaving small hole for drainage. The wound on the cheek was bandaged, on the head of the patient put on a nightcap and bandaged again. From the point of view of neurosurgery of the 21st century such manipulations look barbaric, but it should be borne in mind that the doctor Harlow was an experienced military surgeon. Among other things, Harlow ordered Gage should never lower his head and even sleep while sitting in pillows. Hours passed, and Gage, despite his terrible wound, was conscious and even showed signs of improvement. During the night, Harlow wrote in his diary: “The patient's mind is clear. Constant excitement of the legs, he bends them one by one and pulls out ... He says that he does not want to see his friends, as he will return to work in a few days. nine0003

However, recovery Gage dragged on. Although the next morning he recognized those who had come to him from New Hampshire mother and uncle, on the second day after the Phineas incident, by according to Dr. Harlow, “lost control of his mind and fell into madness". Two days later, Gage seemed to come to his senses - he again became "rational, recognized his friends." The patient's condition improved very quickly, and Harlow acknowledged for the first time that Phineas could make a full recovery - but then, 12 days after the incident, Gage fell into a semi-comatose condition. He became drowsy, answered questions rarely and in monosyllables. Cause complication of his condition, apparently, was an infection that got into the wound - according to according to Harlow, a "fungus" appeared in the eye socket and along the edges of the wound. "The smell of of the mouth and from the wound in the head, terribly fetid. Answers in monosyllables only if he force it. Will not eat unless force-fed. Friends and Ministers hotel expect his death from hour to hour and have already prepared a coffin and a suit, "- the doctor wrote in his diary. nine0003

Harlow, “lost control of his mind and fell into madness". Two days later, Gage seemed to come to his senses - he again became "rational, recognized his friends." The patient's condition improved very quickly, and Harlow acknowledged for the first time that Phineas could make a full recovery - but then, 12 days after the incident, Gage fell into a semi-comatose condition. He became drowsy, answered questions rarely and in monosyllables. Cause complication of his condition, apparently, was an infection that got into the wound - according to according to Harlow, a "fungus" appeared in the eye socket and along the edges of the wound. "The smell of of the mouth and from the wound in the head, terribly fetid. Answers in monosyllables only if he force it. Will not eat unless force-fed. Friends and Ministers hotel expect his death from hour to hour and have already prepared a coffin and a suit, "- the doctor wrote in his diary. nine0003

However, Harlow is not gave up. He cut out the fungus-affected tissue that filled the opening of the wound and burned its edges with a lapis pencil (silver nitrate). Then cut with a scalpel soft tissues of the head from the wound outlet to the upper part of the nose: from eight ounces (250 ml.) of fetid, blood-mixed pus flowed from the incision. This operation saved Gage's life.

Then cut with a scalpel soft tissues of the head from the wound outlet to the upper part of the nose: from eight ounces (250 ml.) of fetid, blood-mixed pus flowed from the incision. This operation saved Gage's life.

"Gage was lucky that he met Dr. Harlow, - wrote one of the modern researchers this amazing case. - Few doctors in 1848 had experience surgical treatment of brain abscess, and Harlow specialized in him at Jefferson Medical College. nine0003

From now on Gage's real recovery began. On the 24th day, for the first time, he managed get up from a chair on your own. A month later, he was already moving freely and around the house and on the streets. Harlow left town for a week, leaving his an amazing patient in the care of friends, and this almost crossed out all of his Proceedings: Gage ran away from the "nannies" and stumbled all day in the pouring rain, got his feet wet and caught a cold. However, if the metal pin did not kill him, then the fever was all the more beyond the power. Returning Harlow noticed that Gage would likely recover if only he could be kept control. nine0003

Returning Harlow noticed that Gage would likely recover if only he could be kept control. nine0003

And Phineas Gage really recovered! It seems incredible, but it only took him two and a half months to return to normal after meter iron rod weighing 6 kg. deprived him of a decent part of the brain. He returned to his parents' home in New Hampshire and within a few weeks began to do the usual work on the farm: he looked after horses and cows, worked in the field. The family tried not to overload him with work, but Phineas did not wanted to be treated as an invalid, and even got angry if he noticed that he is being "favoured". But he loved to gather his little ones around him. nephews and nieces (he had no children of his own) and entertained them incredible stories of miraculous deeds (fictitious) and battles with bandits, in who allegedly received his terrible wounds. nine0003

Spring The following year, Gage returned to Cavendish to see Dr. Harlow. He noted that, despite the loss of the left eye and partial paralysis of the left side of the face, the patient's physical condition is "good", and it can be considered that he is generally healthy. However, Gage suffered from depression, and although Gage did not complained, he confessed to Harlow that he was experiencing some kind of "strange feeling", which cannot be described.

However, Gage suffered from depression, and although Gage did not complained, he confessed to Harlow that he was experiencing some kind of "strange feeling", which cannot be described.

Gage titled physicians became interested. Gage made famous throughout America Henry Jacob Bigelow is Professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School. AT within the walls of this school, the “Gage phenomenon” was studied for several weeks by both professors and and medical students. nine0003

Some time Gage made his living playing the role of a "living museum exhibit" in Barnum American Museum in New York (but not Barnum Circus, which later traveled all over America showing curiosities like bearded women and mermaids). Anyone who wanted to pay a quarter could admire a man with a hole in his skull and the famous ramming pin that he held in his hands. Whatever irresponsible journalists wrote, Gage still did not spoke - but with lectures about his amazing cure, he really traveled to most major cities in New England. Bigelow recalled that Gage “I was quite inclined to do something like that to earn a couple of honest penny", but the audience was not too interested in lectures, and Phineas refused speeches. nine0003

Bigelow recalled that Gage “I was quite inclined to do something like that to earn a couple of honest penny", but the audience was not too interested in lectures, and Phineas refused speeches. nine0003

Monstrous However, the injury did not go unnoticed for him. Gage's character has deteriorated. He became intolerant, aggressive and rude, fickle, easily changing his plans, disrespectful to others, capricious and stubborn. Phineas started swearing - he had never had such a tendency before. Easily insulted family and friends. The only beings he's still with found a common language, there were horses and dogs. Before the injury, the examiner wrote Bigelow, although he did not go to school, he had a developed mind and a balanced character; those who knew him spoke of Phineas as shrewd and intelligent business person, very energetic and persistent in achieving his goals. Everybody these wonderful qualities disappeared after an accident with a metal with a pin, as if they had leaked out, along with part of the brain, from the hole in Gage's skull. Friends bitterly said that he was "no longer Gage." nine0003

Friends bitterly said that he was "no longer Gage." nine0003

After examinations at Boston Medical School and performances at the Barnum Gage Museum became known throughout America. Couplets were sung about him:

Virtuous Gage, Vermont

Rammed gunpowder using the probe

The probe sped off will,

Having broken his left frontal lobe -

Gage now swearing and drinking.

However, Gage did not remain without work: his talent for dealing with horses in the eyes owners of large stables atoned for all the newly acquired shortcomings of his character. After all, one of his employers recommended him Chilean transport company, and Gage left for Chile. He's been there for seven years. worked as a coachman of a stagecoach drawn by six horses and cruising on the route Valparaiso-Santiago. Mid 1859he felt that his health is deteriorating sharply, and returned to the United States. Gage settled in California and there, patronized by his mother and sister, he was on the mend again - but in February 1860 he began to have epileptic seizures. During one of these Gage's seizures and died on May 21, 1860 - almost 12 years after an iron tamping pin pierced his head.

During one of these Gage's seizures and died on May 21, 1860 - almost 12 years after an iron tamping pin pierced his head.

Six more passed years, and Dr. Harlow, who all these years unsuccessfully tried to find out at least anything about the fate of his former patient, found out that Gage had died in California, and wrote to his family. At the request of the doctor who has done so much for her son, Gage's mother agreed to the exhumation and gave Harlow the grave skull of a son with a hole from an iron rod, as well as the rammer itself a pin with which Gage did not part until his last day (according to legend, this instrument was placed with him in the coffin). Carefully examining the skull and rod, Harlow donated them to the Warren Anatomy Museum at Harvard School medical research, where they are kept to this day. nine0003

Case of Gage remained one of the greatest mysteries of medicine for over a hundred years. years. How did the loss of a large piece of brain tissue not kill Gage, but completely changed his character? Only in 2012 a group of American neurologists led by John Van Horn from of the University of California simulated the injury received by Gage, and received answers to these questions.