Operationally defined examples

Operational Definition Psychology - Definition, Examples, and How to Write One

Every good psychology study contains an operational definition for the variables in the research. An operational definition allows the researchers to describe in a specific way what they mean when they use a certain term. Generally, operational definitions are concrete and measurable. Defining variables in this way allows other people to see if the research has validity. Validity here refers to if the researchers are actually measuring what they intended to measure.

Definition: An operational definition is the statement of procedures the researcher is going to use in order to measure a specific variable.

We need operational definitions in psychology so that we know exactly what researchers are talking about when they refer to something. There might be different definitions of words depending on the context in which the word is used. Think about how words mean something different to people from different cultures.

To avoid any confusion about definitions, in research we explain clearly what we mean when we use a certain term.

Operational Definition Examples

Example One:

A researcher wants to measure if age is related to addiction. Perhaps their hypothesis is: the incidence of addiction will increase with age. Here we have two variables, age and addiction. In order to make the research as clear as possible, the researcher must define how they will measure these variables. Essentially, how do we measure someone’s age and how to we measure addiction?

Variable One: Age might seem straightforward. You might be wondering why we need to define age if we all know what age is. However, one researcher might decide to measure age in months in order to get someone’s precise age, while another researcher might just choose to measure age in years. In order to understand the results of the study, we will need to know how this researcher operationalized age. For the sake of this example lets say that age is defined as how old someone is in years.

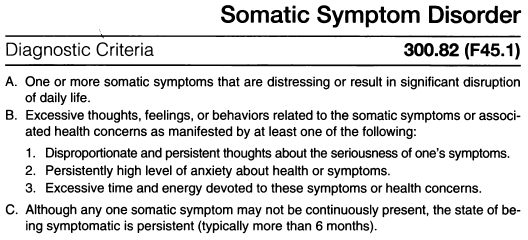

Variable Two: The variable of addiction is slightly more complicated than age. In order to operationalize it the researcher has to decide exactly how they want to measure addiction. They might narrow down their definition and say that addiction is defined as going through withdrawal when the person stops using a substance. Or the researchers might decide that the definition of addiction is: if someone currently meets the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for any substance use disorder. For the sake of this example, let’s say that the researcher chose the latter.

Final Definition: In this research study age is defined as participant’s age measured in years and the incidence of addiction is defined as whether or not the participant currently meets the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for any substance use disorder.

Example Two

A researcher wants to measure if there is a correlation between hot weather and violent crime. Perhaps their guiding hypothesis is: as temperature increases so will violent crime. Here we have two variables, weather and violent crime. In order to make this research precise the researcher will have to operationalize the variables.

Variable One: The first variable is weather. The researcher needs to decide how to define weather. Researchers might chose to define weather as outside temperature in degrees Fahrenheit. But we need to get a little more specific because there is not one stable temperature throughout the day. So the researchers might say that weather is defined as the high recorded temperature for the day measured in degrees Fahrenheit.

Variable Two: The second variable is violent crime. Again, the researcher needs to define how violent crime is measured. Let’s say that for this study it they use the FBI’s definition of violent crime. This definition describes violent crime as “murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault”.

However, how do we actually know how many violent crimes were committed on a given day? Researchers might include in the definition something like: the number of people arrested that day for violent crimes as recorded by the local police.

Final Definition: For this study temperature was defined as high recorded temperature for the day measured in degrees Fahrenheit. Violent crime was defined as the number of people arrested in a given day for murder, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault as recorded by the local police.

How to Write an Operational Definition

For the last example take the opportunity to see if you can write a clear operational definition for yourself. Imagine that you are creating a research study and you want to see if group therapy is helpful for treating social anxiety.

Variable One: How are you going to define group therapy? here are some things you might want to consider when creating your operational definition:

- What type of group therapy?

- Who is leading the therapy group?

- How long do people participate in the therapy group for?

- How can you “measure” group therapy?

There is no one way to write the operational definition for this variable. You could say something like group therapy was defined as a weekly cognitive behavioral therapy group led by a licensed MFT held over the course of ten weeks. Remember there are many ways to write an operational definition. You know you have written an effective one if another researcher could pick it up and create a very similar variable based on your definition.

Variable Two: The second variable you need to define is “effective treatment social anxiety”. Again, see if you can come up with an operational definition of this variable. This is a little tricky because you will need to be specific about what an effective treatment is as well as what social anxiety is. Here are some things to consider when writing your definition:

- How do you know a treatment is effective?

- How do you measure the effectiveness of treatment?

- Who provides a reliable definition of social anxiety?

- How can you measure social anxiety?

Again, there is no one right way to write this operational definition. If someone else could recreate the study using your definition it is probably an effective one. Here as one example of how you could operationalize the variable: social anxiety was defined as meeting the DSM-5 criteria for social anxiety and the effectiveness of treatment was defined as the reduction of social anxiety symptoms over the 10 week treatment period.

Final Definition: Take your definition for variable one and your definition for variable two and write them in a clear and succinct way. It is alright for your definition to be more than one sentence.

Why We Need Operational Definitions

There are a number of reasons why researchers need to have operational definitions including:

- Validity

- Replicability

- Generalizability

- Dissemination

The first reason was mentioned earlier in the post when reading research others should be able to assess the validity of the research. That is, did the researchers measure what they intended to measure? If we don’t know how researchers measured something it is very hard to know if the study had validity.

The next reason it is important to have an operational definition is for the sake of replicability. Research should be designed so that if someone else wanted to replicate it they could. By replicating research and getting the same findings we validate the findings. It is impossible to recreate a study if we are unsure about how they defined or measured the variables.

Another reason we need operational definitions is so that we can understand how generalizable the findings are. In research, we want to know that the findings are true not just for a small sample of people. We hope to get findings that generalize to the whole population. If we do not have operational definitions it is hard to generalize the findings because we don’t know who they generalize to.

Finally, operational definitions are important for the dissemination of information. When a study is done it is generally published in a peer-reviewed journal and might be read by other psychologists, students, or journalists. Researchers want people to read their research and apply their findings. If the person reading the article doesn’t know what they are talking about because a variable is not clear it will be hard to them to actually apply this new knowledge.

Examples of Operational Definitions

An operational definition is a detailed specification of how one would go about measuring a given variable. Operational definitions can range from very simple and straightforward to quite complex, depending on the nature of the variable and the needs of the researcher. Operational definitions should be tied to the theoretical constructs under study. The theory behind the research often clarifies the nature of the variables involved and, therefore, would guide the development of operational definitions that would tap the critical variables.

Clearly Stating the Operational Definition

There is an old saying that you can never be too rich. When it comes to operational definitions, you can never be too detailed. The more clearly you specify the procedures, the more likely that the procedures will be carried out precisely and the more likely that researchers who attempt to replicate your work will use the same procedures.

Even for simple things, it it best to specify procedures in detail. For example, if you want to weigh people in a study, you could just say "weigh them." That procedure seems obvious on the surface, but how do you guarantee that the scale is working properly (standardizing the measure) and what should you have your participants wear when they are being weighed. The weight of street clothes can vary significantly depending on how cold it is or what you might be carrying in your pockets. Those variation add error variance.

If you are having your participants take a psychological measure, you want to specify the conditions under which the measure should be given. Some measures, for example, will be answered differently depending on whether they are filled out privately or in a group. Some measures are affected by distractions in the environment. That is one reason why admissions exams like the SAT are often given under very strict conditions that are spelled out in detail for the examiners.

If you are unsure of whether certain variations in procedures will affect the scores, err on the side of caution and try to hold the procedures constant by specifying precise instructions for measurement. You can often learn what factors are known to affect a measure by doing a thorough library search of how that measure, or similar measures, have been used in the past.

Examples of Operational Definitions

The best way to illustrate the process of developing operational definitions for variables is to identify several theoretical constructs and develop multiple operational definitions of each. This not only illustrates how the process is done, but also shows that most constructs can be measured in more than one way. The research literature also shows that it is common for different operational definitions to tap different aspects of a construct and thus react differently to experimental manipulations.

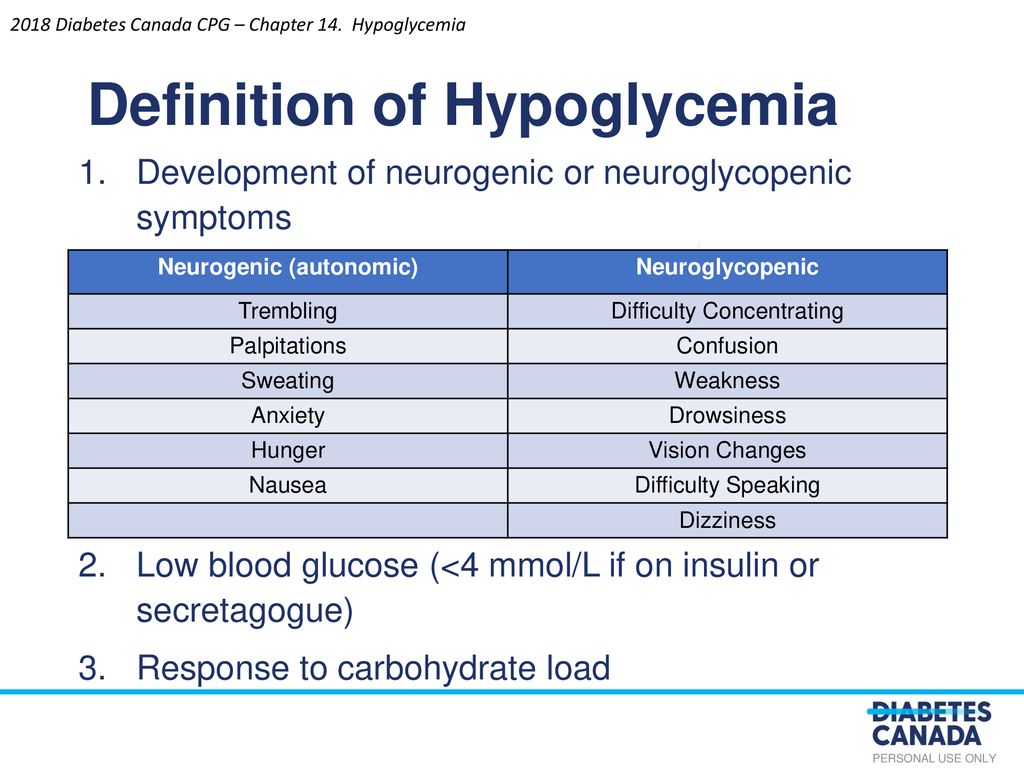

Anxiety is a concept that most of us are all too familiar with. It is an unpleasant feeling that occurs in certain situations. It can disrupt our functioning if it is excessive, but it also motivates behavior.

So how do you measure anxiety? How do you operationally define anxiety? Now this is a problem that has challenged researchers for years, and many fine operational definitions of anxiety are already available for our use. For the sake of this exercise, however, we will assume that we have to develop our own measure without benefit of much of this existing research.

Since this is a concept that we have first-hand knowledge of, we might start the process of operationally defining anxiety by asking ourselves what it is like. What do we feel? How do we react? How do others react? What features in other people would suggest to us that they are anxious? These are all excellent ways to start this process. It is especially useful to focus on factors that indicate anxiety in others, because those are likely to be more objective and observable factors and would provide higher reliability.

When we think of anxiety, we think first about the "feeling" of being anxious. We know what it is like and we can easily tell when we are experiencing it. It is less clear whether others would be able to tell that we are anxious just by looking at us. If fact, our own experience suggests that we may be effectively hiding our anxiety, because some people have told us they were impressed with how calm we were at a time when we felt anything but calm. Furthermore, others have told us they were very anxious in a situation in which we had observed them and they did not look anxious to us. Nevertheless, the feeling of anxiety is distinctive, even if it is not always public, so it provides one way of measuring anxiety.

Since feelings are internal events, apparently without consistent external features, we will have to rely on self-reports to find out whether a person is feeling anxious. We could simply ask people to rate their level of anxiety on a 100-point scale, a technique that is commonly used. These are often referred to as SUDS (subjective units of distress) ratings. We could instead ask people a number of questions about their feelings, questions that tap elements of anxious feelings. These might include things like "I am worried about what might happen." or "I can feel my heart pound." The number of such items endorsed by the person would likely indicate the level of anxiety. With mild anxiety, a few might be endorsed, but as the anxiety became more intense, more and more of the items would be endorsed, because more of the anxiety symptoms would be intense enough that the person noticed them.

We just mentioned something that probably resonated with many of you. When you are anxious, your heart feels as if it is pounding, and when you are very anxious, you almost always experience this sensation. This is a real effect. Anxiety is not just a feeling; it is also a physiological response. When we are anxious, our heart beats faster and stronger, our muscles tense and we shake, our palms sweat and sometimes even our face sweats, our voice may crack or our face flush. Sometimes these effects are visible to others; often they are not unless the anxiety is very strong.

We all have witnessed someone giving a talk in class who was visibly shaking, whose voice was cracking, and whose face lit up the entire room with a red glow. We can use these responses to provide another set of ways of operationally defining anxiety. We can measure the physiological changes in people as an indication of their anxiety. If their heart rate increases, we would take that as a sign of anxiety. If their palm sweats, that is another sign of anxiety. Without going into the complexities of how one measures each of these things, we will just say that it is relatively easy to do so, and that these measures have often been used to index the anxiety level of participants in studies. With modern telemetry, it is even possible to monitor many of these physiological responses while the person is carrying out everyday activities in his or her natural environment.

Most of the people who were obviously nervous about giving a talk in school somehow got through the talks, but a few quit in the middle, sometimes even leaving the room. This is yet another indicator of anxiety--in this case, the behavior of fleeing the situation. We do not see it often in classroom situations, but people who are anxious of snakes will often run away or at least step back from the object of their fear. Furthermore, we often see avoidance of situations that produce anxiety. Someone who has been very anxious giving talks in public may chose to only take classes that do not require a presentation. He or she may even chose jobs later that are unlikely to require a presentation, even though it may mean making considerably less or having a less prestigious job. So behavior, both escape and avoidance, is yet another indicator of anxiety.

We have outlined three separate strategies for operationally defining anxiety. They include (1) asking people how anxious they are feeling, (2) measuring their physiological response, and (3) observing their behavior, especially their escape and avoidance behavior. The natural question for most students is which of these is the BEST measure of anxiety. In essence, which of the measures captures true anxiety most precisely.

The answer to this question for anxiety is often frustrating to students, but reflects the complex reality of human emotions. The answer is "It depends. " Most students seem to prefer the physiological measures, because they seem more "basic." Certainly, the physiological measures have the advantage that we cannot deliberately lie about them. If we are anxious and we don't want people to know that we are anxious, we can always lie about how we feel, provided our anxiety is not so obvious that everyone can see signs of it. We can also stay in situations in spite of intense anxiety to avoid losing face or to do something that we feel is critical. Many nervous parents have spoken up at PTO meetings, because they thought it was important to the well being of their children.

But physiological measures also have their problems. The heart rate will indeed go up when we are anxious, but it also goes up for lots of other reasons as well. Walk up a flight of stairs and your heart rate will have increased several beats a minute to meet the aerobic demand. Your palms will sweat from nervousness, but they also sweat, along with the rest of your body, when you are hot. The same is true of face flushing. Your muscles will tighten when nervous, but they also tighten when you are expecting to act or are engaged in physical action. So none of our measures of anxiety is ideal.

If none of our measures of anxiety is ideal, which one should we use. The best answer is "as many as we can." The truth is that each of these measures capture a different aspect of the construct of anxiety, and therefore they do not always agree with one another. For example, people can avoid a situation without showing visible signs of anxiety, but the avoidance is a strong indicator of their feeling about the situation. Even though there may be little physiological arousal and they may claim to not be anxious, their avoidance is telling another story. The validity of that other story can often be confirmed if the person is required to face what they have been avoiding.

Looking at it from another perspective, we often see people with considerable anxiety, as measured by their physiological responses, performing all of the things required of them. Golfers might calmly sink a 10-foot putt to win a tournament, even though their heart might be racing and their palms are dripping wet. So are they anxious or not? Scientifically, the fact that these various measures of anxiety do not always agree has led to a much more thorough understanding of anxiety. We now know that it is not a single construct, but rather represents a complex collection of responses, and that the pattern that we will see will depend on the situation that the person is in. We would never have been able to recognize that if we had not operationally defined anxiety in several different ways and used all of those various definitions in our research studies.

Civic responsibility seems like a clear construct. People who are civic-minded are likely to do what is expected of them by society. But what is it that is expected of a responsible citizen? Do responsible citizens vote regularly? Do they agree to serve on juries? Do they donate time to the Scouts or Little League baseball? Do they drive within the speed limit? Do they work to help solve world hunger? Do they pay all the taxes that they owe? Must they do all of these things in order to be a responsible citizen, or would a certain subset of these activities be sufficient? Should some of these activities be considered mandatory of responsible citizens, like voting for example? Would the late Harry Chapin, a well known song writer and performer, be considered a responsible citizen? He gave as many as a hundred benefit concerts a year to combat world hunger, but by most accounts drove like a maniac, collecting frequent speeding tickets. His reckless driving eventually took his life in a fiery crash on the Long Island Expressway.

This rather clear construct suddenly gets fuzzy when you start wondering about how to measure it? What behaviors should be included? What should be excluded? Do some behaviors bias you against certain people. For example, would doctors who try to avoid jury duty, because of the demands of caring for their patients, be responsible or irresponsible for their decision? Would people who avoid activities, because they are uncomfortable around large groups of people, appear to be irresponsible because they do not engage in important civic activities? The best solution is to provide a standard set of behaviors that will be taken into account. As we will see, these behaviors either can be taken from the person's everyday life or can be determined by specified laboratory procedures.

Natural Environment Measures. Many psychological measures are based on looking at samples of relevant behavior in natural environments. Sometimes these measure rely on the self-report of behavior. Other times the behavior can be measured through standardized observations of activities. For example, we could construct a measure of civic responsibility with 10 items that represent things that one believes that a responsible citizen would do. We could ask people to rate on a scale how frequently they do each of those behaviors. The behaviors may include things like voting, learning about the qualifications of candidates running for office, staying informed about civic matters, supporting the activities of those who are working for the community, and so on.

The more clearly we specify the items, the more likely each participant taking the measure will interpret it the same. For example, an item like "I vote in most elections" is more ambiguous than "I have voted in at least 4 of the last 5 elections." Items such as "I support the efforts of community leaders" is so vague and open to interpretation that you would have no idea what endorsing that item would say about the individual. If measures of this construct already existed and the reliability and validity data for those measures were adequate, you would definitely want to go with them. If not, you would have to develop your own measure, and then it would be your responsibility to gather reliability and validity data as part of that process.

You might be asking yourself what would stop people from lying about their activities? The answer is "not much," and of course some people would lie, or at least would try to put their activities in the best possible light. There are ways to deal with this problem. One way is to have some items that measure this tendency to place oneself in an overly favorable light. For example, including items such as "I thoroughly investigate the qualifications of all candidates before voting" would likely pick up the extent of such self-promotion. It is unlikely that anyone THOROUGHLY investigates the qualifications of ALL candidates before voting, so those who claim to do that are probably claiming other things that are less than accurate.

Some questionnaires are much more effective in giving an accurate indication of behavior if they are completed anonymously. Structuring the research study so that such anonymous responses are possible may dramatically improve the effectiveness of some measures. Clearly in this situation, the operational definition includes not only the items of the psychological measure, but also the conditions under which the measure should be administered.

Another way to guard against participants presenting themselves more favorably than is warranted is to base your measure on publicly recorded data. For example, voting records and jury participation records can often be accessed. We won't be able to know how people voted, but we will know if they voted. Some public service activities, such a being on advisory boards, are a matter of public record. Detailing a list of such public service activities as your operational definition of civic responsibility, and then doing the leg work to track down the requisite information, can provide a measure that is not contaminated by a tendency to inflate one's actual civic-minded activity level. Of course, a disadvantage of this approach is that many civic-minded activities are not public and therefore could not be included in this measure.

Laboratory Measures. If one thinks of civic responsibility as a trait, one would expect that it would occur in many different settings. Therefore, one does not have to sample every possible setting to get an idea of how civic-minded a person is. This opens the possibility that a laboratory analogue could prove to be a very satisfactory measure of this construct.

Laboratory analogues are laboratory tasks that represent behavior that is believed to be similar conceptually to the natural behavior in the community. The task need not take place in the laboratory, but it will be under the control of the researcher. For example, the researcher could call participants in the study to see if they are willing to do something that one would expect a civic-minded individual to do. It might be something like agreeing to help on a project or lending their name to a worthy cause. Of course, people may be unwilling to help on a particular project, whereas they are willing to help on other projects, so such a standardized measure will not be a perfect indicator of civic-mindedness. Nevertheless, it is a reasonable operational definition of this construct, and it has the advantage of being under the control of the researcher.

The Perfect Operational Definition

One must accept that there is no perfect operational definition for a given construct. Each operational definition will have advantages and disadvantages. A self-report measure is often quick and easy, but it is subject to presentational biases by the participants who take it. Actual counts of behavior are less affected by presentational biases, but they are much more time consuming and often miss critical behavior that is private. Physiological measures can tap some constructs, but physiological changes occur for many different reasons; therefore, it is hard to know if observed physiological changes are an indication of the construct of interested. Laboratory analogues have the advantage of experimental control, but there is always the question of how closely they relate to real world behavior.

Because no single operational definition is likely to provide the perfect measure of the construct of interested, it is wise to consider using more than one operational definition in a given research study. If you randomly select a dozen research studies from the best journals, you may be surprised to see how often this approach is used. Multiple operational definitions help us to zero in on the constructs that we are studying, and they often give us insights into the complexity of those constructs. We already discussed how anxiety researchers now recognize that the feelings, behavior, and physiology of anxiety are not just alternate ways of tapping anxiety, but represent distinctly different aspects of anxiety. By recognizing this basic fact, we can begin to identify how these various aspects of anxiety fit together. This is science at its best--a concerted effort at zeroing in on the workings of nature.

Operational definition, E. Deming.

Back List Next

"According to many industrialists, there is nothing more important to business than operational definitions. And nothing in production is not as neglected as operational definitions.

[1] W. Edwards Deming,

(from Henry R. Neave, "The Organization as a System"

Henry R. Neave, "The Deming Dimension")

The material was prepared by the scientific director of the AQT Center Grigoriev S. P.

Free access to articles does not in any way reduce the value of the materials presented in them.

In many companies in the service sector, trade and production, there is often no documented descriptions of certain problematic procedures that are unambiguous for understanding by all employees of the company - operational definitions, it only increases the variability in the system. There is an assumption that procedures are completely and without it defined and everyone follows them. How exactly are they following? Which version of the paraphrase from one employee to another correspond to the actions of employees (as in the game of broken phone)?

It's amazing how many years it will take humanity to accept new knowledge. Another 350 years?! Compare quotes Rene Descartes and Edwards Deming:

Edwards Deming and Walter Shewhart, considered the work of creating operational definitions as in the highest degrees are important and put their value on a par with the theory of variations and control charts. After all, the use operational definitions is directly related to the reduction of variability.

"Operational definitions are definitions with which a reasonable person can agree and use them in practice. Operational definitions are not at all open to interpretation and do not allow ambiguity - on the contrary, they themselves interpret, interpret.

[2] E. Deming, "Out of the Crisis"

(W. Edwards Deming, "Out of the Crisis")

Deming often asked his students, “What is 'pure'? But we must know this if our work is to wipe the tables. Does this mean that the table is clean enough to was it possible to either dine, or use it as a counter, or operate on a patient? What's happened satisfactorily? Satisfactory for what? Satisfactory for whom? What test procedure should we use?

"Operational definitions are the language of business. The operational definition of concepts such as "safe", "round", "reliable", or any other qualitative definitions should be equally clear both for the seller and for the buyer, have the same meaning yesterday and today for the production worker. For example:

1. A specific test method for a sample of a material or subassembly.

2. Criterion (or criteria) for making a decision.

3. Decision: yes or no, the object or material meets or does not meet the criterion (criteria).".

[2] E. Deming, "Out of the Crisis"

(W. Edwards Deming, "Out of the Crisis")

“The production specialist has other reasons for concern. He knows that the requirements for quality, including conditions of fixed accuracy and reproducibility, may be included in the contract and that the uncertainty of the meaning of any term used in establishing a tolerance, including "accuracy" and "reproducibility" can lead to mutual misunderstanding and even have legal consequences. Therefore, the practitioner tries so precisely to establish certain and appropriate operationality of the terms as far as it makes sense".

- [2] W. Shewhart

The following is an excerpt from E. Deming's book "Out of the Crisis". [2] - W. Edwards Deming, "Out of the Crisis: A New Paradigm for Managing People, Systems, and processes" / "Out of the Crisis", W. Edwards Deming - M.: Alpina Publisher, 2017. Scientific editors Yu. Rubanik, Yu. Adler, V. Shper. You can buy the book from the Alpina publishing house. Publisher.

Everyone thinks they know what pollution is until they try to explain it to someone else.

An operational definition of river pollution, soil pollution, street pollution is required. These phrases do not make sense until they are statistically determined. For example, it is not enough to say that air, containing 100 parts per million of carbon monoxide is dangerous. Need to be specific:

a) a greater quantity is dangerous if it is present at any time, or

b) this or more is dangerous if it is present in the air during a work shift. And how is this concentration should be measured?

Does pollution mean that (for example) carbon monoxide at this concentration will cause disease after three breaths, or if you breathe it constantly for five days? And in any case, how will this influence revealed? What procedure will be used to detect carbon monoxide?

How to diagnose or what is the criterion of poisoning? In people? In animals? If ecology is investigated person, how will people be selected? How many will be required? How many people in the sample should meet the criteria for carbon monoxide poisoning in order to be able to claim unsafe air with several breaths or with constant inhalation? The same questions are relevant for experiments on animals.

Even the adjective "red" has no meaning for business purposes unless it is defined operationally in terms of tests and criteria (especially important in polygraphy - approx. S. Grigoriev). "Clean" has one meaning for plates, knives and forks in a restaurant and another in the production of hard drives for computer or transistors.

A businessman or civil servant cannot afford to be superficial in understanding the specifications (specifications) for products, medicines, production rates.

What is the meaning of the standard that commercial butter must have 80% milkfat? does it mean a requirement of 80 percent or more milkfat in every pound of butter you buy? Or that means 80% on average? What would you mean by 80% milkfat on average? Average over all your purchases of oil during the year? You meant the average production of all oil per year or purchase, made by you or other people in a certain place? How many pounds would you check to calculate average? How would you choose an oil for proof testing? Would you be concerned about content variation milk fat from pound to pound?

Obviously, any attempt to determine operationally what 80% milk fat is requires the use of statistical methods and criteria.

Again, the words "80% milkfat" by themselves are meaningless.

Operational definitions are important for economy and reliability.

Without operational definitions of (for example) unemployment, pollution, product safety and devices, efficacy (e.g. drugs), side effects, duration of dose before they appear side effects, all these concepts are meaningless unless they are statistically determined.

Without operational definitions, problem research will be costly and inefficient, almost certainly leading to endless disputes and contradictions.

Laws passed by Congress and regulations by federal agencies are characterized by a lack of clarity in definitions and costly confusion (anyone can draw a parallel with the situation in our country - approx. S. Grigoriev).

What does the 50% wool label mean? The label on the duvet reads "50% wool". What does this mean? Perhaps you are not really care about this inscription? You are much more interested in color, texture and price. However, some worried about what the label means. The Federal Trade Commission is one of them, but what operational sense does it investing in it?

Suppose you told me that you wanted to buy a 50% wool blanket and I sold you a blanket, one half of which is made entirely of wool and the other half of cotton.

This blanket is, by one definition, 50% wool. But maybe you prefer something else. definition: you can say that 50% wool means something different to you. If so, then what? You can to say that they meant that the wool would be distributed over the blanket. Could you suggest operational a definition like the following:

Cut 10 holes in the blanket with a diameter of 1 or 1.5 cm in random places. Number the cut samples from 1 to 10 and send them for examination.

The chemist will follow established procedures in the analysis. Ask him to write down the value of X; For weight fraction of wool in each sample.

Calculate X sr. - average value for 10 shares of cut samples of a woolen blanket.

Evaluation criteria developed by us (technical requirements):

X cf. ≥0.50;

x max -X min ≤0.02

If the sample does not meet any of the criteria, the blanket does not meet your specifications.

Conclusion: This blanket does not meet our requirements.

Either of the above two definitions of 50% wool is neither true nor false. You have a right and a duty set a definition that suits your purposes. Later, you may have another goal and a new definition. There is no true value for the proportion of wool in a blanket. However, you can get a number after a certain test. So far we have been talking about a single blanket. Now there's a problem lots of blankets. Perhaps you are buying blankets for a hospital or for the army. Here we are faced with fundamental difference: a one-time purchase versus a recurring purchase.

You could state that for every 10 kg of pure wool a manufacturer should use 10 kg of pure cotton. This would be one possible definition of 50% wool, neither right nor wrong, but satisfying your goals.

"The meaning of any instruction, set norm, instruction, statement or rule given to another person message is determined not at all by what its author had in mind, but by what is obtained as a result of its use".

[2] E. Deming, "Out of the Crisis"

(W. Edwards Deming, "Out of the Crisis")

An example of neglecting the operationality of the definition

Article: "Visualization example: board with sling rejection samples", Source: up-pro.ru

A board with samples sling rejections. On it you can see and even check by touch what happened to the rope - squeezing, stratification, inflection.

The foreman of the site became the initiator of the placement of visual information. He made an offer through the Idea Factory and implemented along with a colleague. Now everyone here knows what an out-of-service line looks like.

Lifting work is potentially hazardous. Crane operators and slingers have to take into account many nuances. Main safety requirement - check the equipment before each use. Not allowed to use damaged lines, this may lead to accidents.

As the foreman of the site explained, out of 48 of his subordinates, about half have a related profession of a slinger. Therefore it was it was decided to design a stand with a visual reminder of which ropes to use during loading and unloading it is forbidden. Board with samples of defective slings appeared in November last year.

– Until now, we had a lot of questions in the work of crane operators and slingers about the correctness of the rejection slings, especially metal ones, which are used most often,” says the head of the metal finishing and shipments of finished products SPC No. 1. - There are a number of standards and requirements, and the authors of the project relied on them, during a certain time, collecting samples of defective ropes and drawing up visual information on the board.

Our comment

Beautiful stand, but unfortunately, it does not give a clear operational definition of when to reject sling.

I am sure that this stand only reduced the number of voiced questions from slingers, voiced, but not arising. Yes, now it will be inconvenient for them to ask such questions (ashamed) - after all, now "only a stupid person does not can figure it out."

Let's try to figure it out!

For example, the knot must be tightened or not. How to define operationally what is a "node"? But as measure tightness?

How many strands of wire should be extruded from the strand? As in the sample one to one or one is enough threads?

What is extrusion? Is it any change in the shape of the thread or loop, wave, etc.? If the size of this is important "extrusion", then how to measure it? If this extrusion can be measured, what are the criteria for acceptance decision to marry or not?

These questions are not for the foreman. How could he know about the requirements for the operationality of definitions?! These questions should be asked to the management of the company.

back List More

-

Popular sections

- Open Solutions

- Fundamental knowledge

- Bibliography

- Products and services

- Contacts

Operational definition of concepts - Psychologos

Operational definition of concepts - definition of a concept through clear procedures that tell us "it is" or "it is not". As a rule, an operational concept has two features: a clear definition with a list of the main features and the ability to check their presence or absence with the help of understandable, specific actions.

"Operational - a definition that gives a concept a transferable meaning, indicating how the concept is measured and applied in specific circumstances. " - Deming, 1986.

Unfortunately, in practical psychology, many concepts do not have an established meaning in principle, and each psychologist seems to put essentially different content into one and the same word.

For example, the term "introvert" has at least three different and commonly used meanings. A similar situation with the word "frustration" (frustration). This word is used in at least three different meanings: a) to denote a blocking effect, which prevents a motivated organism from reaching a goal or continuing a goal-directed behavior; b) to refer to the behavior that occurs when a goal-oriented organism encounters such a blocking influence; c) to designate a hypothetical internal process that supposedly explains the observed behavioral responses to a blocking effect.

Talk about the need for an operational definition of concepts comes from physics. The researchers agreed that for better mutual understanding it is necessary to impose more stringent requirements for the definition of concepts. Namely, concepts must be defined strictly in terms of the operations that are used to measure what they stand for. “A concept is a synonym for a corresponding set of operations” (Bridgeman).

According to Bridgman, nothing is as simple and unambiguous as it seems at first sight. Over time, he allowed himself several tactical digressions from his originally monolithic position, such as recognizing the temporary permissibility of "paper" (not yet implemented in hardware) operations and the usefulness of abstract concepts.

The idea that the meaning of all concepts should be limited only to the necessary operations underlying them immediately attracted psychologists. S.S. Stevens quite early began to promote operationalism in psychology, but the wave of enthusiasm for operationalism was brought down by the fact that operationalism was not seriously applicable to psychology, and the gradual movement towards more precise definitions did not suit anyone at that time. The principle of "all or nothing" killed the enthusiasm that arose among psychologists.

No discussions about operationalism, no matter how many times they are renewed, can neglect the fact that psychologists are too often unable to adequately communicate with each other simply by virtue of the loose definition and ambiguous use of basic terms. Some fundamentally important provisions should be emphasized. First, O. o. concepts are not subject to the law "all or nothing"; rather, one can speak of a continuum of operational clarity of definitions, i.e., of the extent to which it was possible to eliminate uncertainty and redundant values in them. or experiment. research, it must be objective; the fact of coming to terms with ambiguity must be seen in many situations as a necessity, but hopefully not as a permanent factor. It is also important that the scientists in communication openly acknowledge the current state of affairs, rather than ignoring it and simply skimming the surface. Thirdly, one should not intrude into questions concerning the essence of already defined concepts and confuse them with the predominantly methodological criteria associated with od.