Anxiety disorders dsm 5 codes

Anxiety Disorders and Related DSM-5 Diagnostic Codes:

Anxiety Disorder

Paul Susic Leave a comment

Anxiety Disorders

According to the American Psychiatric Association, each of the anxiety disorders share the features of fear and anxiety. Fear is a healthy, rational response to either a real or perceived threat whereas anxiety is anticipatory and is in response to a possible perceived threat in the future.

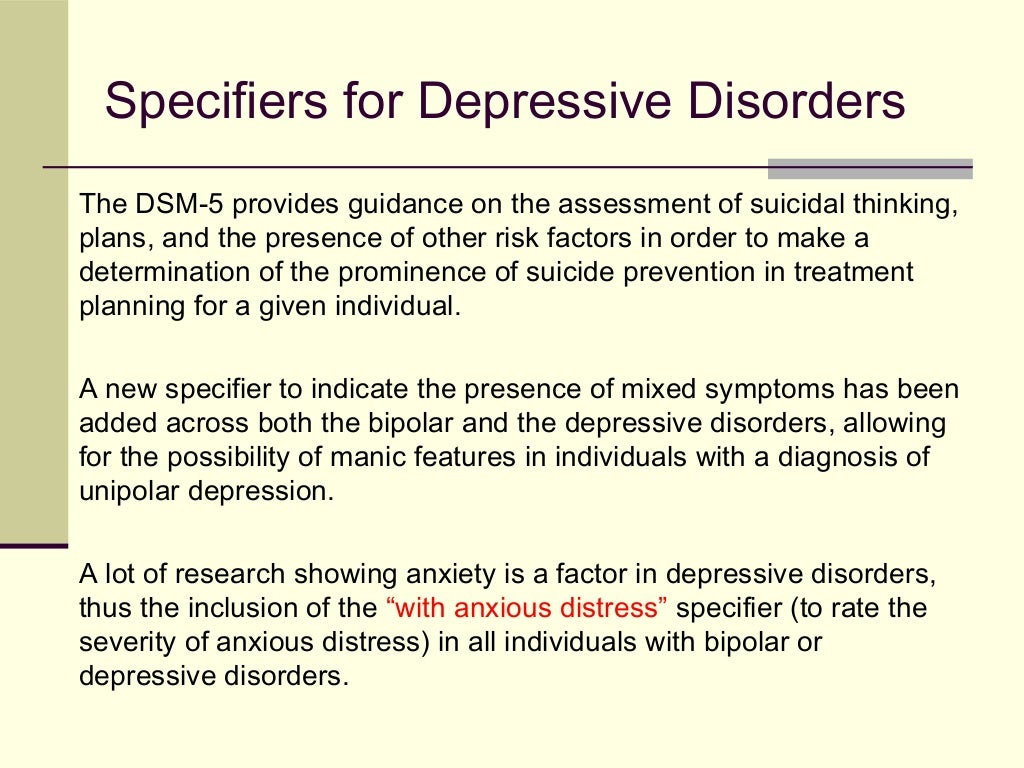

Anxiety among the general population is very high with estimates as high as 18% or 40 million American adults experiencing anxiety disorders each year. Some researchers feel that the lifetime prevalence rate may be as high as 30%. Almost 50% of people who experience anxiety disorders also meet the criteria for depressive disorder. Clinicians recognize that there is a very high level of comorbidity (shared symptoms) between depressive disorders and anxiety disorders, and believe that there may be a possible shared genetic predisposition.

Anxiety disorders frequently persist over time. Because anxiety disorders are so uncomfortable and often disabling, they are frequently the focus of clinical attention. Anxiety disorders are very responsive to psychotherapeutic treatment modalities as well as medications geared toward their specific symptoms. Please see the following specific diagnostic criterion information related to the anxiety disorders.

Specific Anxiety Disorders and Related DSM-5 Diagnostic Codes:

309. 21 (F93 0) Separation Anxiety Disorder

312. 23 (F94.0) Selective Mutism

300. 29 ( . ) Specific Phobia

Specify if:

(F40.218) Animal

(F40.228) Natural Environment

( . ) Blood Injection-injury

(F40.230) Fear of Blood

(F40.231) Fear of Injections and Transfusions

(F40.232) Fear of Other Medical Care

(F40.233) Fear of Injury

(F40. 248) Situational

248) Situational

(F40.298) Other

300. 23 (F40. 10) Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia) Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment

Specify if: Performance only

300. 01 (F41.0) Panic Disorder

( . ) Panic Attack

300. 22 (F40. 00) Agoraphobia

300. 02 (F41.1) Generalized Anxiety Disorder

( . ) Substance/Medication – Induced Anxiety Disorder

293. 84 (F06. 4) Anxiety Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition

300. 09 (F41. 8) Other Specified Anxiety Disorder

300. 00 (F41. 9) Unspecified Anxiety Disorder

Diagnostic Information and Criterion for Anxiety Disorders adapted from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition American Psychological Association by Paul Susic Ph. D. Licensed Psychologist

D. Licensed Psychologist

| GAD | |

|---|---|

| A. Excessive anxiety and worry (apprehensive expectation), occurring on more days than not for at least 6 months, about a number of events or activities (such as work or school performance) | A. A period of at least six months with prominent tension, worry and feelings of apprehension, about every-day events and problems |

| B. The person finds it difficult to control the worry | B. At least four symptoms out of the following list of items must be present, of which at least one from items 1 to 4 At least four symptoms out of the following list of items must be present, of which at least one from items 1 to 4Autonomic arousal symptoms

|

C. The anxiety and worry are associated with three (or more) of the following six symptoms (with at least some symptoms present for more days than not for the past 6 months). Note that only one item is required in children

| C. The disorder does not meet the criteria for panic disorder, phobic anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder or hypochondriacal disorder The disorder does not meet the criteria for panic disorder, phobic anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder or hypochondriacal disorder |

| D. The focus of the anxiety and worry is not confined to features of an Axis I disorder, e.g. the anxiety or worry is not about having a panic attack (as in panic disorder), being embarrassed in public (as in social phobia), being contaminated (as in obsessive–compulsive disorder), being away from home or close relatives (as in separation anxiety disorder), gaining weight (as in anorexia nervosa), having multiple physical complaints (as in somatization disorder), or having a serious illness (as in hypochondriasis), and the anxiety and worry do not occur exclusively during PTSD | D. Most commonly used exclusion criteria: not sustained by a physical disorder, such as hyperthyroidism, an organic mental disorder or psychoactive substance-related disorder, such as excess consumption of amphetamine-like substances, or withdrawal from benzodiazepines |

E. The anxiety, worry or physical symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning The anxiety, worry or physical symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning | |

| F. The disturbance is not caused by the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g. a drug of abuse, a medication) or a general medical condition (e.g. hyperthyroidism) and does not occur exclusively during a mood disorder, a psychotic disorder, or a pervasive developmental disorder | |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | |

| A. Either obsessions or compulsions: Obsessions as defined by (1), (2), (3) and (4):

| A. Either obsessions or compulsions (or both), present on most days for a period of at least 2 weeks |

| B. At some point during the course of the disorder the person has recognised that the obsessions or compulsions are excessive or unreasonable. Note that this does not apply to children | B. Obsessions (thoughts, ideas or images) and compulsions (acts) share the following features, all of which must be present: Obsessions (thoughts, ideas or images) and compulsions (acts) share the following features, all of which must be present:

|

| C. The obsessions or compulsions cause marked distress, are time-consuming (take more than 1 hour a day, or significantly interfere with the person’s normal routine, occupational (or academic) functioning or usual social activities or relationships | C. |

| D. If another Axis I disorder is present, the content of the obsessions or compulsions is not restricted to it (e.g. preoccupation with food in the presence of an eating disorder; hair pulling in the presence of trichotillomania; concern with appearance in the presence of body dysmorphic disorder; preoccupation with drugs in the presence of a substance use disorder; preoccupation with having a serious illness in the presence of hypochondriasis; preoccupation with sexual urges or fantasies in the presence of a paraphilia; or guilty ruminations in the presence of major depressive disorder) | D. Most commonly used exclusion criteria: not caused by other mental disorders, such as schizophrenia and related disorders, or mood (affective) disorders |

| E. | |

| Panic disordera | |

A. Both (1) and (2):

| A. Recurrent panic attacks that are not consistently associated with a specific situation or object and often occurring spontaneously (i. |

| B. Absence of agoraphobia/presence of agoraphobia | B. A panic attack is characterised by all of the following:

|

| C. The panic attacks are not caused by the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g. a drug of abuse, a medication) or a general medical condition (e.g. hyperthyroidism) | C. |

| D. The panic attacks are not better accounted for by another mental disorder, such as social phobia (e.g. occurring on exposure to feared social situations), specific phobia (e.g. exposure to a specific phobic situation), OCD (e.g. on exposure to dirt in someone with an obsession about contamination), PTSD (e.g. in response to stimuli associated with a severe stressor) or separation anxiety disorder (e.g. in response to being away from home or close relatives) | |

| PTSD | |

A. The person has been exposed to a traumatic event in which both of the following were present:

| A. Exposure to a stressful event or situation (either short or long lasting) of exceptionally threatening or catastrophic nature, which is likely to cause pervasive distress in almost anyone |

B. The traumatic event is persistently re-experienced in one (or more) of the following ways:

| B. Persistent remembering or ‘reliving’ the stressor by intrusive flash backs, vivid memories, recurring dreams or by experiencing distress when exposed to circumstances resembling or associated with the stressor |

C. Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma and numbing of general responsiveness (not present before the trauma), as indicated by three (or more) of the following:

| C. Actual or preferred avoidance of circumstances resembling, or associated with, the stressor (not present before exposure to the stressor) |

D. Persistent symptoms of increased arousal (not present before the trauma), as indicated by two (or more) of the following:

| D. Either (1) or (2):

|

| E. | E. Criteria B, C and D all occurred within six months of the stressful event or the end of a period of stress (for some purposes, onset delayed more than six months may be included but this should be clearly specified separately) |

| F. The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning | |

| Social anxiety disorder | |

| A. A marked and persistent fear of one or more social or performance situations in which the person is exposed to unfamiliar people or to possible scrutiny by others. | A. Either (1) or (2):

|

| B. | B. At least two symptoms of anxiety in the feared situation at some time since the onset of the disorder, as defined in criterion B for agoraphobia and in addition one of the following symptoms:

|

| C. The person recognises that the fear is excessive or unreasonable. Note: in children, this feature may be absent | C. |

| D. The feared social or performance situations are avoided or else are endured with intense anxiety or distress | D. Recognition that the symptoms or the avoidance are excessive or unreasonable |

| E. The avoidance, anxious anticipation, or distress in the feared social or performance situation(s) interferes significantly with the person’s normal routine, occupational (academic) functioning, or social activities or relationships, or there is marked distress about having the phobia | E. Symptoms are restricted to, or predominate in, the feared situation or when thinking about it |

| F. | F. Most commonly used exclusion criteria: Criteria A and B are not caused by delusions, hallucinations or other symptoms of disorders such as organic mental disorders, schizophrenia and related disorders, affective disorders or OCD, and are not secondary to cultural beliefs |

| G. The fear or avoidance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or a general medical condition and is not better accounted for by another mental disorder (e.g., panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, separation anxiety, body dysmorphic disorder, a pervasive developmental disorder, or schizoid personality disorder) | |

| H. | |

ICD-10 and DSM-V: differences in the diagnosis of eating disorders

“Today there are 2 main guidelines that specialists from different countries rely on to classify and diagnose all existing diseases, including eating disorders. These are the ICD (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) and the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders).

Of course, there are also national guidelines and classifications. For example, in Soviet psychiatry, such a type of schizophrenia as sluggish schizophrenia was separately distinguished, although such a diagnosis is generally absent in international classifications.

Nevertheless, qualified specialists are guided by the ICD or DSM in their work.

The ICD has more than three hundred years of history and is currently the official regulatory document of the World Health Organization.

ICD went through 10 editions. The current ICD-10 is used, which has been in use in WHO Member States since 1994. And work is already underway on the ICD-11, which is planned to be introduced after 2018.

It is important to note that ICD-10 covers all diseases. Mental and behavioral disorders are presented there only in a separate chapter. And eating disorders are not singled out in a separate rubric in this chapter, but are included in a broader rubric - Behavioral Syndromes Associated with Physiological Disorders and Physical Factors.

This heading has a subheading "Eating Disorders" (code F50), which includes:

- anorexia nervosa

- bulimia nervosa

- overeating associated with other psychological disorders

- Vomiting associated with other psychological disorders

- other eating disorders

- Eating disorder, unspecified

The fundamental point is that in the ICD-10 there is only a classification and key features of eating disorders. And that's it! Data on detailed description of criteria, prevalence, differential diagnosis, etc. in the ICD, unfortunately, you will not find.

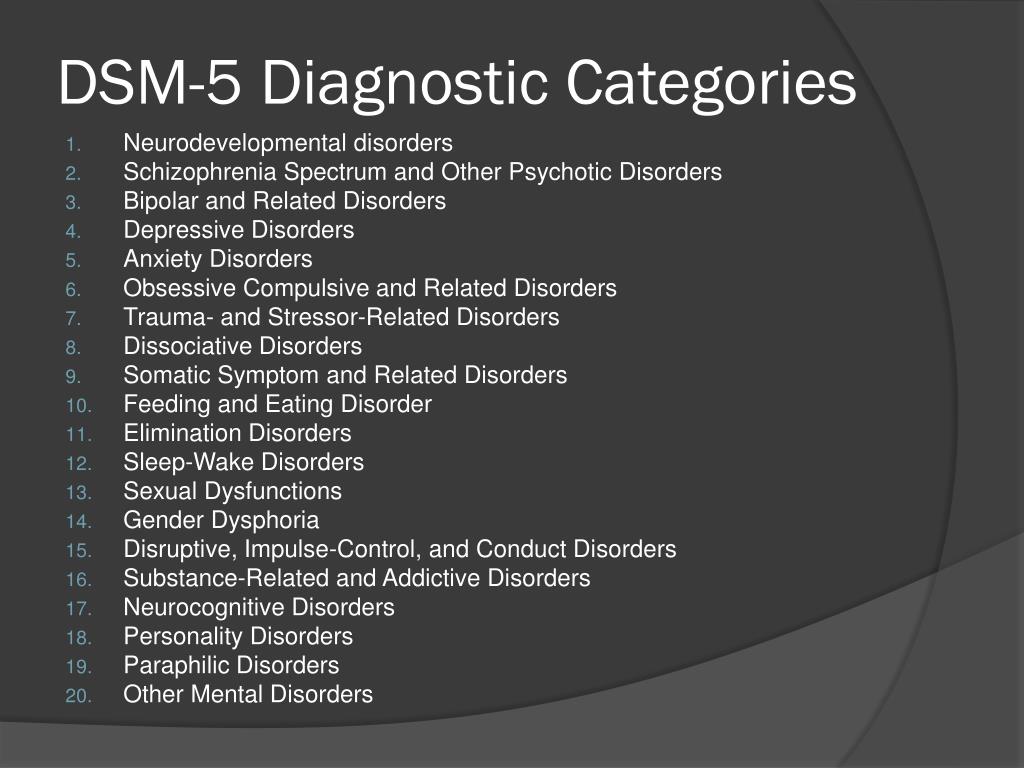

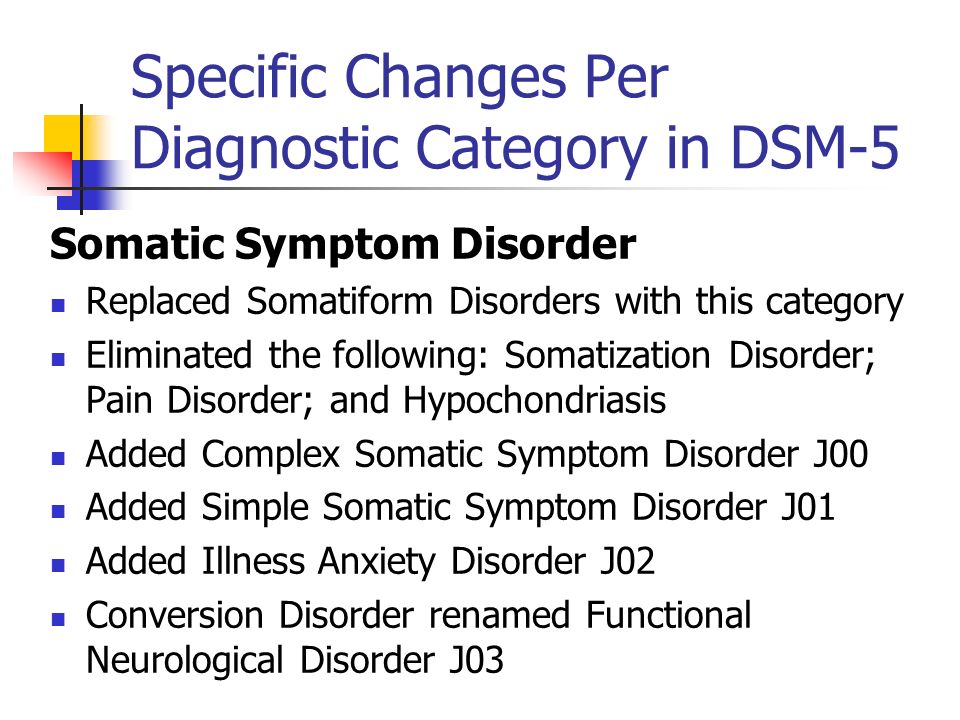

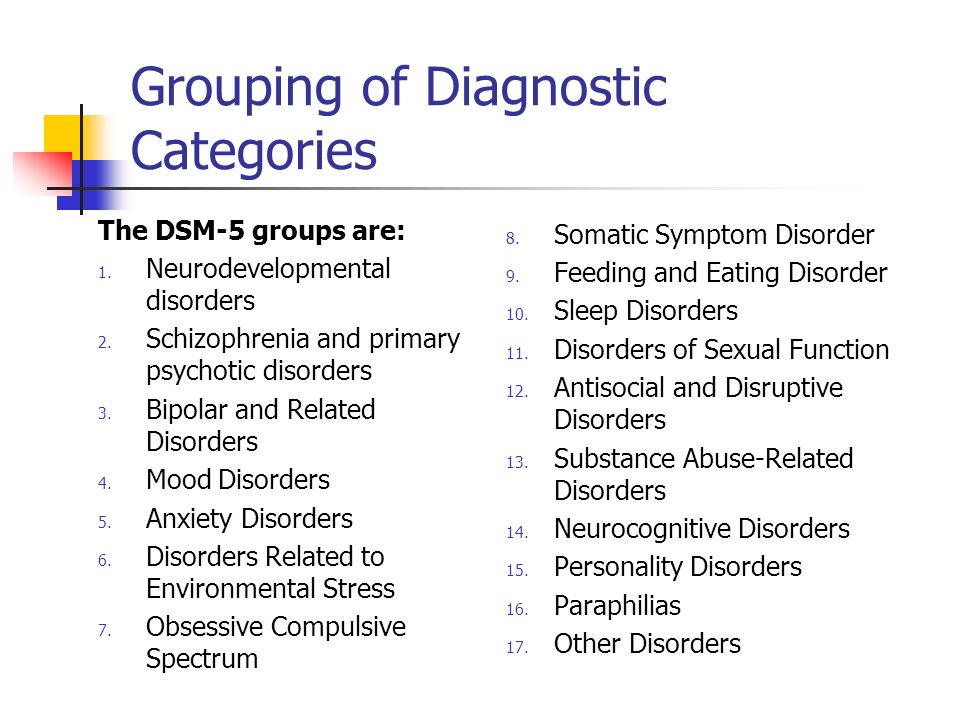

Regarding the DSM, this guide was originally developed by the American Psychiatric Association. The first edition (DSM-I) was in 1952. Now the 5th edition (DSM-V), released in 2013, is already in use. This edition is not available in Russian.

A distinctive feature of this manual is the detailed classification and, most importantly, the description of mental disorders (hence the name).

In particular, a separate section is devoted to eating disorders.

The following eating disorders are distinguished in it:

- “peak” (perverted appetite)

- chewing disorder

- avoidant/restrictive eating disorder

- anorexia nervosa

- bulimia nervosa

- overeating

- other specific eating or eating disorders

- non-specific eating or eating disorders

An important difference of the DSM-V is that, unlike the ICD-10, for each of the major eating disorders are given:

- criteria for diagnosing eating disorders

- extended explanation for each criterion

- subtypes or severity of disorder

- diagnostic features

- data on the prevalence of the disorder

- information on the course and development of the disease

- risk factors

- specific diagnostic markers

- suicide risk data

- consequences of an eating disorder

- differential diagnosis

- relationship with other psychiatric disorders (not related to eating disorders).

In addition, DSM-V is the most current version released in 2013. It presents the latest data on the criteria for mental disorders, some of which differ from those in earlier versions of the guide.

This also applies to eating disorders.”

The author of the article is Sergei Leonov, source https://www.b17.ru/article/mkb10-i-dsm5-otlichiya-v-diagnostike/

* — required fields

By submitting an application, you agree to the terms

of the privacy policy

Read also

Interview of the head physician to anorexia.pro

Maksim Sologub, head physician of the Moscow Center for the Study of Eating Disorders, tells…

Read more »

Anorexia. The plot of the program "Live healthy" on Channel One

We are on the first!

Read more »

Release of the Good Morning program on Channel One

Watch the episode of the Good Morning program on Channel One dedicated to the Day of Struggle against …

Read more »

Live Healthy program on Channel One

On October 13, the program “Live Healthy” was released, where the psychiatrist of the Center took part . ..

Read more »

The program “Beyond” on NTV channel

In October, psychiatrist Marina Evgenievna Kotik took part in the filming of the program “For …

Read more”

Kill the Dragon: the experience of parents struggling with their child’s eating disorder

Our daughter was 12 years old when she was diagnosed with anorexia, and it turned our world upside down …

Read more »

Clinical features of the combination of agoraphobia and non-psychotic mental disorders | Kovalev

Introduction

Russian and English articles were searched in the databases ELibrary.ru, Web of Science, Scopus, Clinical Case, PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Articles were searched using the keywords "agoraphobia", "anxiety disorders", "borderline mental disorders". Inclusion criteria — full-text articles in Russian and English, original research, Cochrane reviews, clinical observations, publication date from 1994 to 2020 Exclusion criteria - abstracts, abstracts, publication date before 1994. A total of 734 publications were found. 43 publications met the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Agoraphobia is a disorder characterized by the appearance of fear when the patient is in open space or in crowded places (shops, bus stops) with the subsequent formation of behavior to avoid situations that caused fear. According to the classification given in the ICD-10, it can be divided into two groups: agoraphobia without anamnestic data for panic disorder and panic disorder with agoraphobia (ICD-10). Some researchers distinguish agoraphobia with early and late (after 65 years) onset [1].

The prevalence of panic disorder is estimated at about 2% of the population per year, or about 2–5% of the population during a lifetime [2][3]. Among these patients, one-third to one-half have agoraphobic symptoms, although the percentage is even higher in clinical samples [4]. Such a fairly high percentage of agoraphobia in the population makes this topic relevant for research.

Recent research results show a comorbidity between agoraphobia and other anxiety spectrum disorders. In particular, agoraphobia occurs in 0.8% of people who have had a panic attack, in 1.1% with panic disorder [2]. It has also been shown that a third of patients with panic disorder and major depressive disorder develop agoraphobia [5].

It is important to note that comorbidity increases the severity of the disease and reduces the effectiveness of the treatment. The nosologies listed above are combined into a group of borderline mental disorders that have a high percentage of occurrence in the population [6]. Some of them, in particular PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), may be factors that shape the development of agoraphobia, so it is important to strive to reduce the prevalence of these nosologies [7].

Another factor in the importance of work in this direction is the fact that agoraphobia significantly aggravates the course of panic disorder and worsens the quality of life of patients, assessed on the SF-36 scale [8].

Taking into account the prevalence of the disease and the decrease in the quality of life in patients, the selection of effective therapy for panic-agoraphobic states plays an important role [9][10].

Panic attacks and panic disorder as the basis for the formation of agoraphobic symptoms

It can be said that the position of agoraphobia as a separate nosology was very "shaky" for a long time. In particular, there was a question about the secondary formation of agoraphobia in relation to panic disorder. Or is it a separate nosological unit, as it was originally indicated in the ICD? 99 neurosis ) . Subsequently, agoraphobia was included in the ICD-9 as an independent syndrome, manifested by multiple fears, and in the ICD-10 it occupies the same status (ICD-10, 1995).

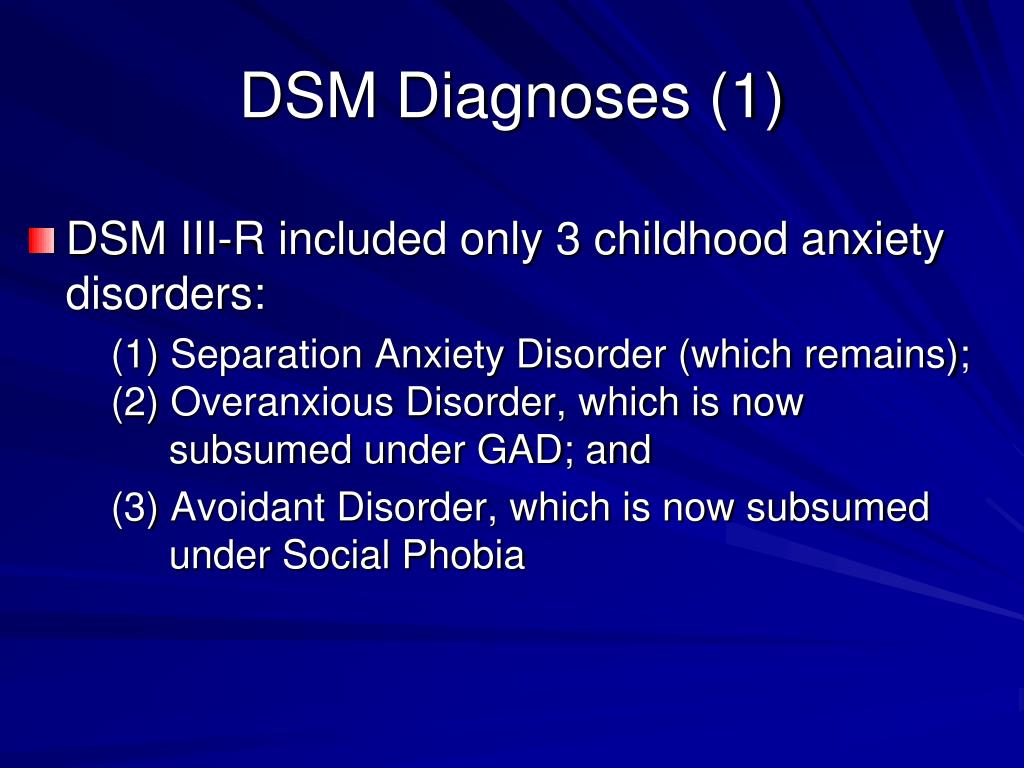

In the United States, where the DSM is the main system for classifying mental disorders, agoraphobia is defined as "feelings of fear with avoidant behavior, formed when you are alone or among people in places from which it is difficult to get out or get medical help in an emergency." It can be said that this definition is similar to the definition of panic disorder and the definition of agoraphobia given in ICD-10. However, the DSM definition of agoraphobia is closer to panic disorder than to phobias. Agoraphobia with panic attacks should be coded as its initial phase, when there are recurrent panic attacks, which in turn leads to the development of fear of such an attack and, accordingly, the avoidance of situations and places that can provoke such an attack. If there is no history of panic attacks, then the diagnosis is agoraphobia without panic attacks, but according to the DSM, avoidance behavior is required to be the result of anxiety about the development of a panic attack, that is, in any case, an association is indicated between a panic disorder or attack and agoraphobia , which is the difference between this classification and ICD-10. Thus, with the DSM-III-R, agoraphobia was defined as a response to situations in which a panic attack occurred. However, the evolution of subsequent revisions of the DSM has been towards greater acceptance of agoraphobia outside of the construct of panic attacks or panic disorder.

The DSM-V classification, released in 2013, has undergone significant changes to the heading of anxiety disorders, including agoraphobia and panic disorder. In particular, they were divided into two separate diagnoses, that is, when formulating a diagnosis, two different codes should be used. It can be said that the diagnostic criteria for agoraphobia have undergone only minor changes. In particular, it is necessary to confirm the occurrence of fear in two or more situations in order to exclude other phobias (APA, 2013).

Panic disorder is a chronic disease, resulting in patients requiring long-term therapy [11]. At the same time, agoraphobia has been shown to be a predictor of poor outcome in individuals with panic disorder [11]. The presence of agoraphobia in such patients exacerbates the clinical course of panic disorder and increases the likelihood of having one or more comorbid psychiatric disorders compared with patients with panic disorder but without agoraphobia. It has been shown that after a panic attack, 37% of patients exhibit moderate avoidance behavior, with 81% of these patients developing such behavior in less than a year [12]. Researchers have identified risk factors that increase the risk of developing agoraphobic symptoms, such as early age at onset of panic attacks [13], female gender [14], and belonging of the underlying disease to the anxiety spectrum group [12]. According to the data of domestic researchers, the predominant sex of patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia is female, and the age of the onset of the disease is 21–30 (32.4%) and 31–40 (35.3%) years, which corresponds to the data of foreign scientists [15 ].

Features of the clinical picture of anxiety spectrum disorders in combination with agoraphobia

Generalized anxiety disorder is a mental pathology that demonstrates a high degree of comorbidity with other nosologies. In particular, it has been shown that the lifetime incidence of major depressive disorder in generalized anxiety disorder is 62.4%, agoraphobia is 25.7%, and panic disorder is 23.5% [16].

Domestic studies have shown the comorbidity of agoraphobia and somato-vegetative type of generalized anxiety disorder, which is manifested by short-term somatized anxiety reactions during the day 1 . Among other disorders that are comorbid with anxiety disorder, of interest is irritable bowel syndrome, which leads to the development of agoraphobia. This is due to the fact that patients are afraid to experience the manifestations of this syndrome in public, which forms avoidant behavior [17].

The impact of agoraphobia on the course of depressive disorders

Studies have shown that the comorbidity of depression and panic disorder with agoraphobia is associated with increased anxiety, hypochondria, feelings of “inadequacy”, social isolation, as well as with treatment failure, difficulties in psychosocial rehabilitation, and an increase in the frequency of hospitalization [ 18]. Also, the severity of depressive symptoms (feelings of guilt, hopelessness) increases in the presence of panic disorder with agoraphobia [19]. Sareen J. et al., 2005 [20] showed that panic disorder with agoraphobia is associated with a history of suicide attempts. This is very important because a history of a suicide attempt is regarded as a predictor of further suicide attempts. Some researchers believed that the presence of a suicide attempt in patients suffering from major depressive disorder is not associated with the presence of panic disorder, since the presence of anxiety, hypochondria was regarded as a protective factor against suicidal behavior, since these patients were more afraid of death [21]. Other researchers believed that there is a link between psychomotor agitation and suicidal ideation, which contradicts the hypothesis of anxiety as a protective factor against suicide [22]. The key point in these hypotheses is the existence of a link between depressive and anxiety spectrum disorders.

It has been studied for a long time what factors associated with panic-agoraphobic symptoms can lead to an increased risk of suicidal behavior, in addition to the influence of depression. Patients with comorbidity of anxiety and depression may commit suicide more often than patients without anxiety, as this is a way to get rid of the symptoms that worry them [20]. Panic attacks during depression significantly impair social functioning, which in turn can lead to suicidal ideation.

It should be noted that there is an inverse effect of depression on agoraphobia, in particular, there is an increase in the severity of phobic symptoms [23].

Thus, there is a complex pathogenetic relationship between panic-agoraphobic symptoms and depression. In this regard, the study of this issue is very important, as it will help reduce the likelihood of suicidal behavior.

PTSD as an etiological factor in agoraphobia

Studies have shown a high comorbidity between panic disorder and PTSD. Thus, panic disorder occurs in 7.3-18.6% of men and 12.6-17.5% of women suffering from PTSD [24]. More recent studies have shown that 35% of patients with PTSD experienced panic attacks within a year, leading to increased comorbidity with other anxiety spectrum disorders and impaired social functioning [25].

The relationship between PTSD and panic disorder is emphasized in connection with the emergence of a circular model of the development of fear, which postulates a similar etiology of anxiety disorders based on this emotion [26]. Applying this hypothesis to PTSD and panic disorder, we can say that in a situation that triggers a reminder of a physical threat, a person experiences tachypnea, heart pain and fear of death. The hypothesis of the circular formation of a feeling of fear is in good agreement with the assumption that panic during a traumatic event becomes part of a conditioned reflex that can start at a certain moment, demonstrating the above symptoms [27]. In this case, agoraphobic symptoms can form, when patients avoid those places that cause a panic attack and experience anxiety about its likely development [13].

The impact of personality disorders on the clinical picture of agoraphobia

Understanding how personality traits are associated with panic disorder and agoraphobia is an important step in understanding the etiology of the latter. Researchers have shown that cluster C (“anxiety” group) of psychopathy, especially avoidant and dependent, are associated with anxiety disorders, in particular with panic disorder and agoraphobia [28]. It should be noted that some researchers dispute the view that these types of personality disorders are predisposing factors for panic disorder and agoraphobia, based on retrospective data on the premorbid personality structure of patients with anxiety disorders. Other researchers believe that in the early stages of the course of a panic disorder, the symptoms of the disease cannot affect the deformation of the personality [29]. This point of view can be supported by the fact that effective treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia can neutralize pathocharacterological personality traits [30].

It is known that the personal characteristics of patients can have a significant impact on the prognosis of therapy. Thus, in the study by M. Ozkan and A. Altindag, 2005 [31] it was shown that those patients in whom characterological features reach the severity of psychopathic, panic disorder is characterized by a more severe course, agoraphobic symptoms are more often associated, and the risk of suicide is higher.

Among the factors that form personality, in addition to genetically determined personality traits, upbringing plays an important role. Domestic researchers have shown that a disharmonious type of upbringing was very often applied to patients with agoraphobia. The most common style is “hyperresponsibility and hyperprotection” (50.98%), which correlates with social anxiety and social phobia. The next most common (24.11%) parenting style was "Cinderella", as a result of which patients have a complex of guilt and addiction, and the ban on the manifestation of negative emotions led to somatization of anxiety 2 .

Influence of the type of hypochondria on the dynamics of agoraphobia

After a panic attack, patients often develop anxiety in anticipation of a second attack, which is updated if it is necessary to stay in a situation that can trigger a phobic reaction (anxiety, a feeling of tension in the body, tachycardia, shortness of breath). These manifestations could be accompanied by the development of hypochondriacal disorders. Fear for health was in the nature of obsessive hypochondria with an understanding of the morbidity and groundlessness of the phobia and the fight against it, but sometimes hypochondria can take on the character of overvalued. The latter option is distinguished by the absence of a critical attitude to one's condition [18].

In the work of I. B. Poze 3 it was also found that all patients suffering from agoraphobia have comorbidity with hypochondriacal disorders: from the degree of fixation to obsessive nature. Neurotic hypochondria was characterized by the specificity of nosophobia with somato-vegetative manifestations. The clinical picture was characterized by a change of syndromes, such as hypochondriacal manifestations and pathocharacteristic changes in personality overlapped the picture of phobia. Subsequently, the clinic of neurotic development was determined by a complex obsessive-phobic and hypochondriacal complex. Interestingly, according to the results of this work, it was revealed that the overvalued type of hypochondriacal disorders was formed in patients with personality disorders. So, in anxiety, anancaste and dependent personality disorders, hypochondriacal development was revealed with an accentuation of perfectionism, a change in priorities and values, and a “break in the life curve”. The hysterical personality showed a more favorable course. There was a partial reduction of hypochondria with the restoration of the previous level of functioning. Thus, we can say that the presence of a hysterical radical in the personality structure is prognostically favorable, while an anacastic, anxious and dependent one is unfavorable. At the same time, the clinical picture of hypochondria determines the dynamics of the course of agoraphobia. With neurotic hypochondria, long-term remissions without psychopathological disorders were observed, and with overvalued hypochondria, a continuous course with generalization and complication of the clinical picture due to the formation of comorbid relationships was observed.

Research in this direction abroad took place in the eighties. Hypochondria was seen as a somatic manifestation of a violation of self-perception, and agoraphobia as a defensive reaction and an attempt to restore a disturbed self-perception. It has also been shown that patients can endure panic attacks earlier without understanding their psychological etiology, but that they may be the key moment in the formation of hypochondria or an anxious temperament.

Agoraphobia as part of sluggish schizophrenia

Although most of the study of the comorbidity of anxiety disorders and schizophrenia dates back to the early years of the nosological approach in psychiatry, for a long time this topic was ignored by both clinicians and researchers [32]. This was probably due to the fact that for a long time in the DSM diagnostic criteria it was indicated that an anxiety spectrum disorder can be diagnosed if there is no connection with the disorder of the first axis, in particular schizophrenia, which led to a low diagnosis of this nosology in patients with schizophrenia. [33]. However, with the advent of the DSM-III-R, the diagnosis of comorbid anxiety disorder was allowed if its manifestations were not associated with an underlying mental illness. The second reason for the increased interest in this problem at the moment is that the presence of a comorbid anxiety disorder negatively affects the rehabilitation of patients and their degree of functioning [34]. Thus, the treatment of anxiety spectrum disorders in patients with schizophrenia is necessary, as it increases the likelihood of achieving a favorable outcome [35]. In a meta-analytic study by A. M. Achim et al., 2009, which included 52 studies with a total of 4,032 patients, examined the frequency of anxiety spectrum disorders in patients with schizophrenia. The authors showed that the average prevalence of agoraphobia in this cohort of patients is 5.4%, 95% confidence interval lies in the range from 0.2% to 10.6% [36].

In the Russian school of psychiatry, it is customary to single out a sluggish type of schizophrenic process, which in the American school is regarded as a schizotypal personality type. The endogenous process in this case is characterized by the absence of pronounced positive symptoms, but against the background of a “delayed” course [37]. Some researchers consider agoraphobia as part of a defect formed as a result of a sluggish process 4 [40].

According to Russian studies, the onset of agoraphobia in patients with schizophrenia occurs in adulthood. The main plot of the phobia is the fear of being alone in a confined space and the fear of independent movement on the street. Interestingly, agoraphobic symptoms were formed not only against the background of panic disorder, but also in patients with synesthesia [38].

Effect of agoraphobia on the clinical picture of chronic alcoholism

In Germany, U. Schneider and A. Altman, 2001 conducted a large retrospective epidemiological study MUCPA (Multicentre Study of Psychiatric Comorbidity in Alcoholics - Multicenter Study of Comorbidity with Psychiatric Diseases among Alcoholics), the purpose of which was to determine the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders among people suffering from alcoholism . The study included 556 patients suffering from alcoholism (patients who also used other psychoactive substances were excluded from the study). Anxiety disorders were found in 42.3% of those surveyed. Generalized anxiety disorder was diagnosed in 42.3%, agoraphobia in 12.9%.%, social phobia — in 13.1%, panic disorder — in 13.7% of the examined [39].

According to K. Tomasson and P. Vaglum (1996), in the presence of agoraphobia/panic disorder, the risk of re-treatment for alcoholism after detoxification is 6 times higher in individuals with less than two previous visits [40].

Domestic studies have shown that the picture of panic disorder with agoraphobia worsens if the patient has chronic alcoholism (in particular, the frequency of attacks increases), while the presence of agoraphobic symptoms leads to a relapse of alcoholic disease, which is explained by the use of alcohol to relieve symptoms [35 ]. The same authors showed that in the presence of chronic alcoholism, agoraphobic symptoms in panic disorder develop faster, and the quality of remission is significantly lower than in patients without alcohol dependence.

Domestic researchers have revealed a high incidence of dependence on tranquilizers, while this phenomenon is more common in people with an unfavorable course of agoraphobia 5 .

Conclusion

Summarizing the above, it can be noted that agoraphobia is still an urgent problem for both the clinician and the researcher. An analysis of the literature showed that, probably due to the dominance of "American" views on this nosology, it was inextricably considered secondary to panic disorder. In turn, this has led to a lack of data on agoraphobic symptoms. However, even from this material it is clear that this disorder is a serious problem for a psychiatrist due to the fact that it is not rare, while it aggravates the clinical picture of other mental illnesses. In particular, as mentioned above, it increases the risk of suicidal behavior in depression, reduces the effectiveness of therapy for schizophrenia spectrum disorders and the quality of life of patients, leads to a relapse of chronic alcoholism, and also increases the likelihood of developing dependence on tranquilizers.

1. Less Yu.E. Typology of generalized anxiety disorder (clinic, comorbidity): Abstract of the thesis. dis. for the degree of Ph.D. GNTSSSP named after V.P. Serbian. Moscow, 2008. 123 p.

2. Pose. I.B. Clinical and psychological predictors of an unfavorable course of agoraphobia with panic disorder: Abstract of the thesis. dis. for the degree of Ph.D. Moscow State Medical University named after A.I. Evdokimov. Moscow, 2012. 177 p.

3. Poze. I.B. Clinical and psychological predictors of an unfavorable course of agoraphobia with panic disorder: Abstract of the thesis. dis. for the degree of Ph.D. Moscow State Medical University named after A.I. Evdokimov. Moscow, 2012. 177 p.

4. Kolyutskaya E.V. Obsessive-phobic disorders in schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders: Abstract of the thesis. dis. for the degree of Ph.D. NCPZ RAMS. Moscow, 2001. 152 p.

5. Poze. I.B. Clinical and psychological predictors of an unfavorable course of agoraphobia with panic disorder: Abstract of the thesis. dis. for the degree of Ph.D. Moscow State Medical University named after A.I. Evdokimov. Moscow, 2012. 177 p.

1. Seguij, Salvador-Carulla L, Marquez M, Garcia L, Canet j, et al. Differential clinical features of late-onset panic disorder. J Affect Discord. 2000;57(1-3):115-124. DOI: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00082-8

2. Kessler RC, Chiu wT, jin R, Ruscio AM, Shear K, walters EE. The epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(4):415-24. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.415

3. Carlbring P, Gustafsson H, Ekselius L, Andersson G. 12-month prevalence of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in the Swedish general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37(5):207-11. DOI: 10.1007/s00127-002-0542-y

4. weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino Gj, Faravelli C, Greenwald S, et al. The cross-national epidemiology of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(4):305-9. DOI: 10. 1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160021003

5. wittchen HU, Nocon A, Beesdo K, Pine DS, Hofler M, et al. Agoraphobia and panic. Prospective-longitudinal relations suggest a rethinking of diagnostic concepts. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(3):147-57. DOI: 10.1159/000116608

6. Aleksandrovsky Yu.A. Borderline mental disorders. M.: Medicine; 2000.

7. Pfaltz MC, Michael T, Meyer AH, wilhelm FH. Reexperiencing symptoms, dissociation, and avoidance behaviors in daily life of patients with PTSD and patients with panic disorder with agoraphobia. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(4):443-50. DOI: 10.1002/jts.21822

8. Carrera M, Herrán A, Ayuso-Mateos jL, Sierra-Biddle D, Ramírez ML, et al. Quality of life in early phases of panic disorder: predictive factors. J Affect Discord. 2006;94(1-3):127-34. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.03.006

9. Croft A, Hackmann A. Agoraphobia: an outreach treatment programme. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2013;41(3):359-64. DOI: 10.1017/S135246581200077x

10. Kozlov V.V., Vlasov N.A. Models of short-term psychotherapy of agoraphobia. Human factor: Social psychologist. 2020;1(39):356-363. eLIBRARY ID: 42969608

11. Carpiniello B, Baita A, Carta MG, Sitzia R, Macciardi AM, et al. Clinical and psychosocial outcome of patients affected by panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: results from a naturalistic follow-up study. Euro Psychiatry. 2002;17(7):394-8. DOI: 10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00701-0

12. Katerndahl DA. Predictors of the development of phobic avoidance. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(8):618-23; quiz 624. DOI: 10.4088/jcp.v61n0813a

13. Goodwin RD, Hamilton SP. The early-onset fearful panic attack as a predictor of severe psychopathology. Psychiatry Res. 2002;109(1):71-9. DOI: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00357-2

14. Yonkers KA, Zlotnick C, Allsworth j, warshaw M, Shea T, Keller MB. Is the course of panic disorder the same in women and men? Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(5):596-602. DOI: 10.1176/ajp.155.5.596

15. Statsenko O.A., Ivanova T.I. Clinical and dynamic features of agoraphobia with panic disorder of neurotic origin. Siberian Bulletin of Psychiatry and Narcology. 2011;(1):27-30. eLIBRARY ID: 16158300

16. wittchen HU, Zhao S, Kessler RC, Eaton ww. DSM-III-R generalized anxiety disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(5):355-64. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950050015002

17. Golden wL. Cognitive-behavioral hypnotherapy in the treatment of irritable-bowel-syndrome-induced agoraphobia. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2007;55(2):131-46. DOI: 10.1080/00207140601177889

18. Statsenko O.A., Usov G.M. Symptom complex of agoraphobia with panic disorder, comorbid with depression. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. Special issues. 2021;121(5-2):49-54. DOI 10.17116/jnevro20211210549

19. Frank E, Shear MK, Rucci P, Cyranowski jM, Endicott j, et al. Influence of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms on treatment response in patients with recurrent major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(7):1101-7. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.7.1101

20. Sareen j, Cox Bj, Afifi TO, de Graaf R, Asmundson Gj, et al. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(11):1249-57. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249

21. Placidi GP, Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Brodsky B, Ellis SP, Mann jj. Anxiety in major depression: relationship to suicide attempts. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1614-8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1614

22. Bernstein IH, Rush Aj, Yonkers K, Carmody Tj, woo A, et al. Symptom features of postpartum depression: are they distinct? Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(1):20-6. DOI: 10.1002/da.20276

23. Allen LB, white KS, Barlow DH, Shear MK, Gorman jM, woods Sw. Cognitive-Behavior Therapy (CBT) for Panic Disorder: Relationship of Anxiety and Depression Comorbidity with Treatment Outcome. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32(2):185-192. DOI: 10. 1007/s10862-009-9151-3

24. Feldner MT, Smith RC, Babson KA, Sachs-Ericsson N, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky Mj. Test of the role of nicotine dependence in the relation between posttraumatic stress disorder and panic spectrum problems. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22(1):36-44. DOI: 10.1002/jts.20384

25. Cougle jR, Feldner MT, Keough ME, Hawkins KA, Fitch KE. Comorbid panic attacks among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder: associations with traumatic event exposure history, symptoms, and impairment. J Anxiety Discord. 2010;24(2):183-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.10.006

26. Andrews G., Charney D. S., Sirovatka P. j., Regier D. A., eds. Stress-induced and fear circuitry disorders: Refining the research agenda for DSM-V. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2009. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09071033

27. Hinton DE, Hofmann SG, Pitman RK, Pollack MH, Barlow DH. The panic attack-posttraumatic stress disorder model: applicability to orthostatic panic among Cambodian refugees. Cogn Behav Ther. 2008;37(2):101-16. DOI: 10.1080/16506070801969062

28. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Patricia Chou S, et al. Co-occurrence of 12-month mood and anxiety disorders and personality disorders in the US: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Psychiatrist Res. 2005;39(1):1-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.05.004

29. Cassano GB, Michelini S, Shear MK, Coli E, Maser jD, Frank E. The panic-agoraphobic spectrum: a descriptive approach to the assessment and treatment of subtle symptoms . Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(6 Suppl):27-38. DOI: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.27

30. Marchesi C, Cantoni A, Fontò S, Giannelli MR, Maggini C. The effect of pharmacotherapy on personality disorders in panic disorder: a one year naturalistic study. J Affect Discord. 2005;89(1-3):189-94. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.07.007

31. Ozkan M, Altindag A. Comorbid personality disorders in subjects with panic disorder: do personality disorders increase clinical severity? Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46(1):20-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.015

32. Ulas H, Alptekin K, Akdede BB, Tumuklu M, Akvardar Y, et al. Panic symptoms in schizophrenia: comorbidity and clinical correlates. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61(6):678-80. DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01724.x

33. Voges M, Addington j. The association between social anxiety and social functioning in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2005;76(2-3):287-92. DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.01.001

34. Seedat S, Fritelli V, Oosthuizen P, Emsley RA, Stein Dj. Measuring anxiety in patients with schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(4):320-4. DOI: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253782.47140.ac

35. Niehaus Dj, Koen L, Muller j, Laurent C, Stein Dj, et al. Obsessive compulsive disorder—prevalence in xhosaspeaking schizophrenia patients. S Afr Med J. 2005;95(2):120-2. PMID: 15751207

36. Achim AM, Maziade M, Raymond E, Olivier D, Mérette C, Roy MA. How are prevalent anxiety disorders in schizophrenia? A meta-analysis and critical review on a significant association.

hot flushes or cold chills

hot flushes or cold chills g. hand washing, ordering, checking) or mental acts (e.g. praying, counting, repeating words silently) that the person feels driven to perform in response to an obsession, or according to rules that must be applied rigidly

g. hand washing, ordering, checking) or mental acts (e.g. praying, counting, repeating words silently) that the person feels driven to perform in response to an obsession, or according to rules that must be applied rigidly