How do ssris work for depression

Overview - SSRI antidepressants - NHS

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a widely used type of antidepressant.

They're mainly prescribed to treat depression, particularly persistent or severe cases, and are often used in combination with a talking therapy such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

SSRIs are usually the first choice medicine for depression because they generally have fewer side effects than most other types of antidepressant.

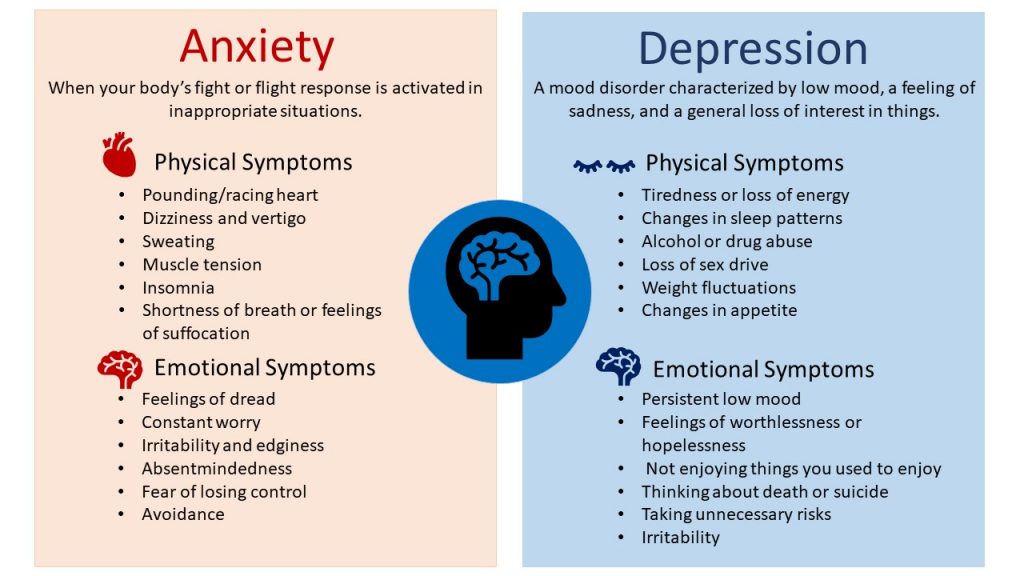

As well as depression, SSRIs can be used to treat a number of other mental health conditions, including:

- generalised anxiety disorder (GAD)

- obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)

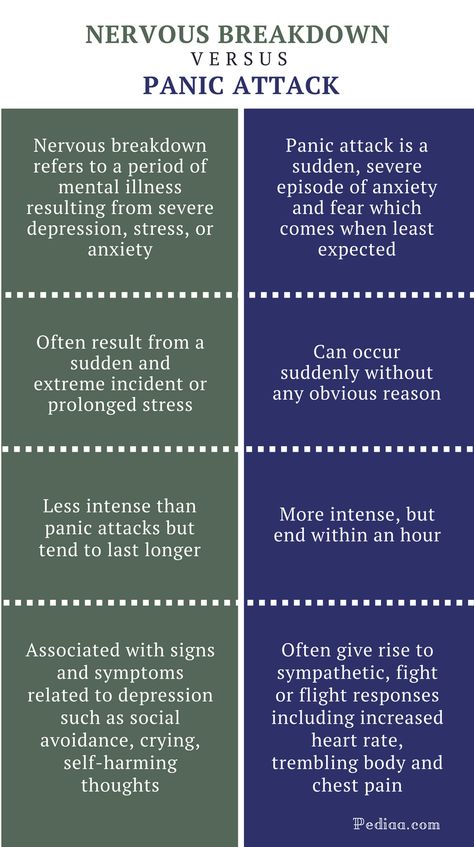

- panic disorder

- severe phobias, such as agoraphobia and social phobia

- bulimia

- post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

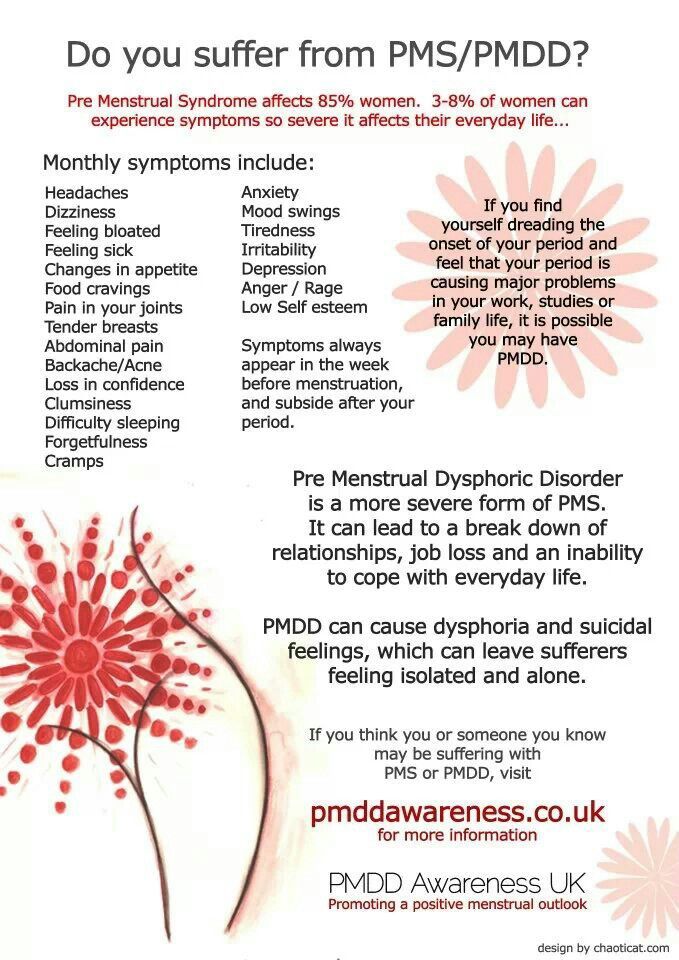

SSRIs can sometimes be used to treat other conditions, such as premenstrual syndrome (PMS), fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Occasionally, they may also be prescribed to treat pain.

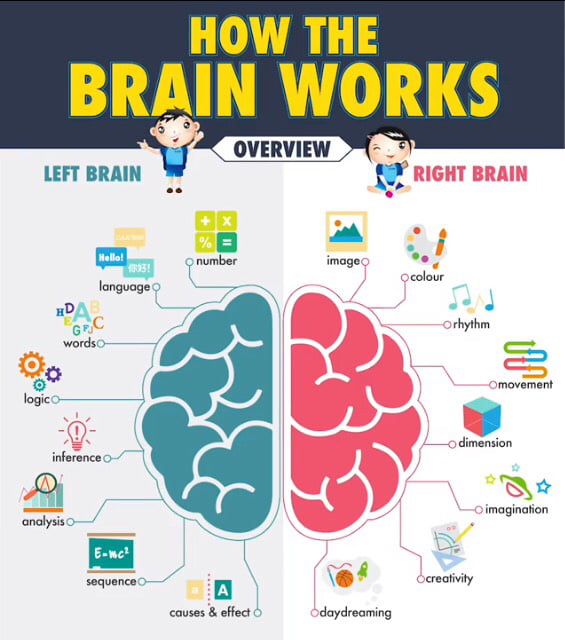

How SSRIs work

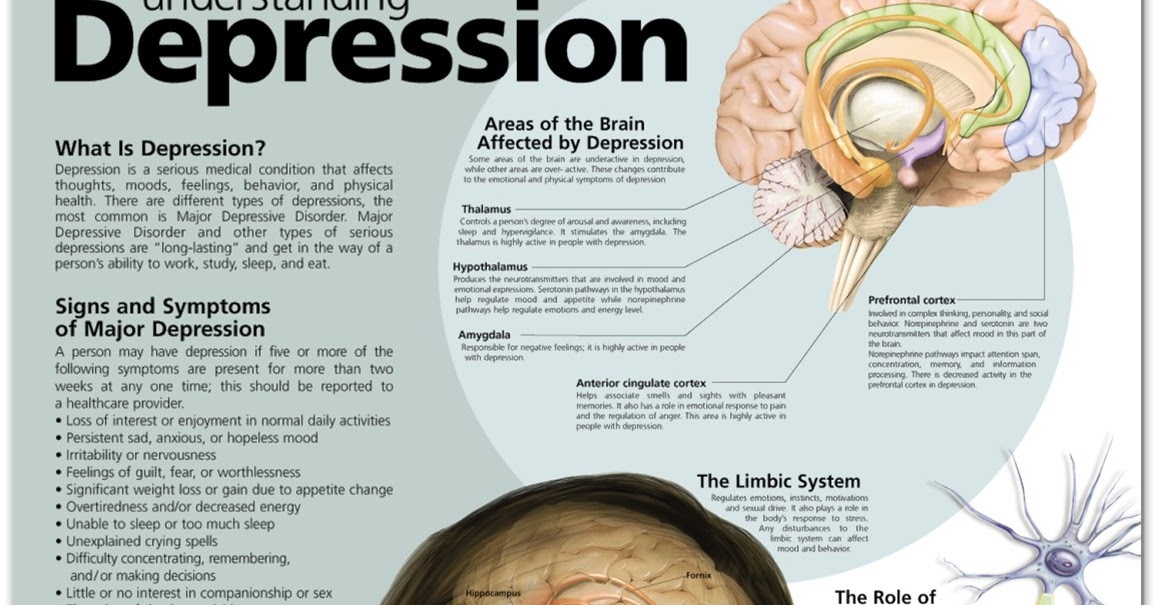

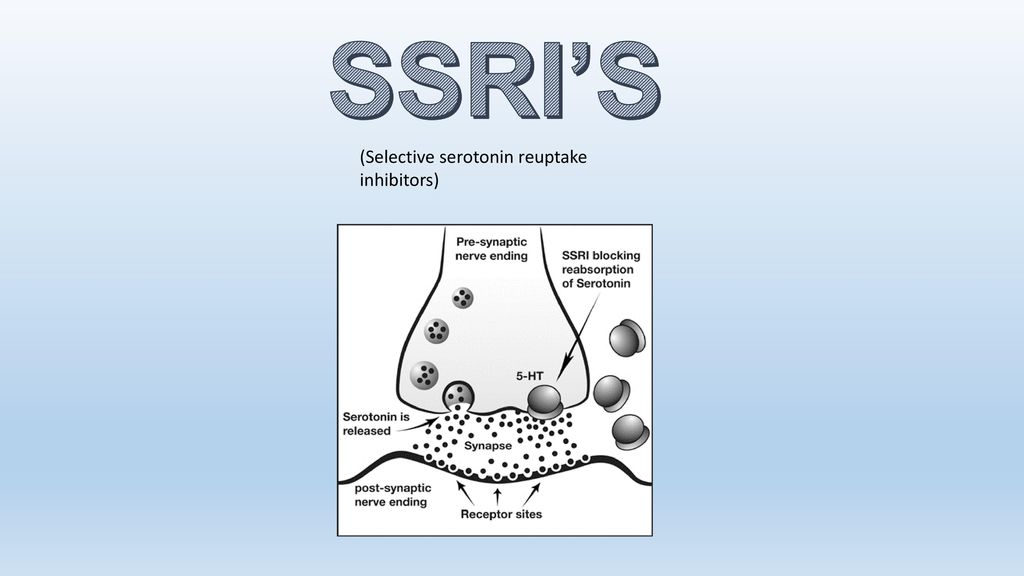

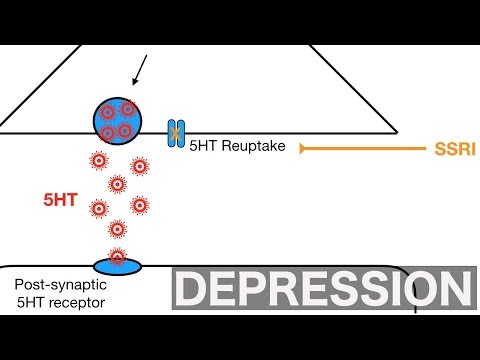

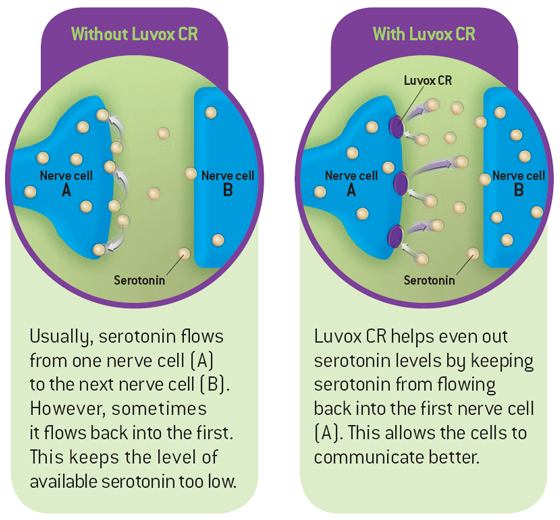

It's thought that SSRIs work by increasing serotonin levels in the brain.

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter (a messenger chemical that carries signals between nerve cells in the brain). It's thought to have a good influence on mood, emotion and sleep.

After carrying a message, serotonin is usually reabsorbed by the nerve cells (known as "reuptake"). SSRIs work by blocking ("inhibiting") reuptake, meaning more serotonin is available to pass further messages between nearby nerve cells.

It would be too simplistic to say that depression and related mental health conditions are caused by low serotonin levels, but a rise in serotonin levels can improve symptoms and make people more responsive to other types of treatment, such as CBT.

Doses and duration of treatment

SSRIs are usually taken in tablet form. When they're prescribed, you'll start on the lowest possible dose thought necessary to improve your symptoms.

When they're prescribed, you'll start on the lowest possible dose thought necessary to improve your symptoms.

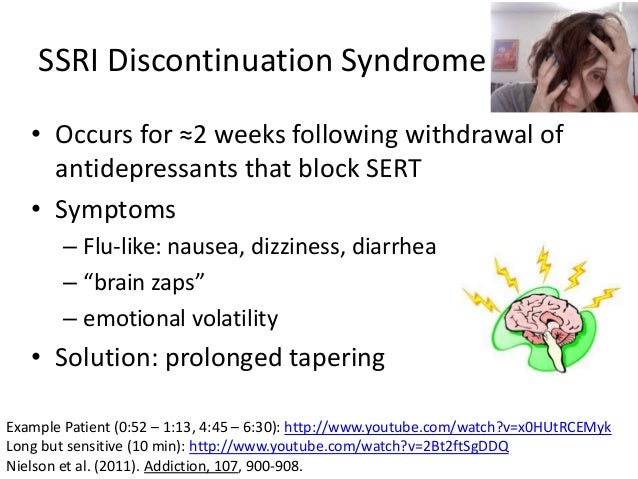

SSRIs usually need to be taken for 2 to 4 weeks before the benefit is felt. You may experience mild side effects early on, but it's important that you don't stop taking the medicine. These effects will usually wear off quickly.

If you take an SSRI for 4 to 6 weeks without feeling any benefit, speak to your GP or mental health specialist. They may recommend increasing your dose or trying an alternative antidepressant.

A course of treatment usually continues for at least 6 months after you feel better, although longer courses are sometimes recommended and some people with recurrent problems may be advised to take them indefinitely.

Things to consider

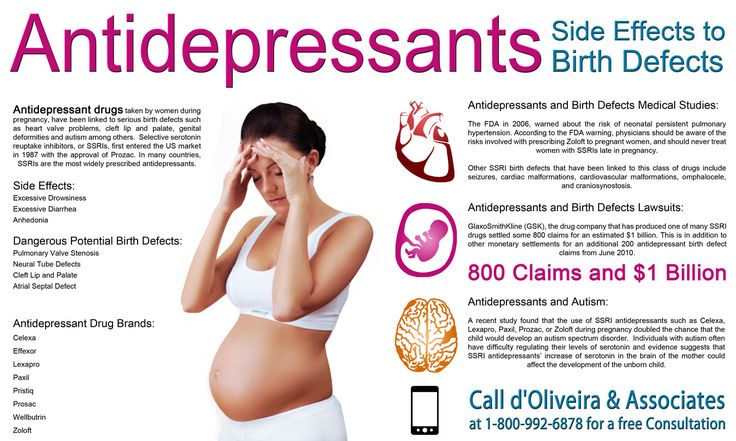

SSRIs aren't suitable for everyone. They're not usually recommended if you're pregnant, breastfeeding or under 18, because there's an increased risk of serious side effects. However, exceptions can be made if the benefits of treatment are thought to outweigh the risks.

However, exceptions can be made if the benefits of treatment are thought to outweigh the risks.

SSRIs also need to be used with caution if you have certain underlying health problems, including diabetes, epilepsy and kidney disease.

Some SSRIs can react unpredictably with other medicines, including some over-the-counter painkillers and herbal remedies, such as St John's wort. Always read the information leaflet that comes with your SSRI medicine to check if there are any medicines you need to avoid.

Side effects

Most people will only experience a few mild side effects when taking SSRIs. These can be troublesome at first, but they'll generally improve with time.

Common side effects of SSRIs can include:

- feeling agitated, shaky or anxious

- diarrhoea and feeling or being sick

- dizziness

- blurred vision

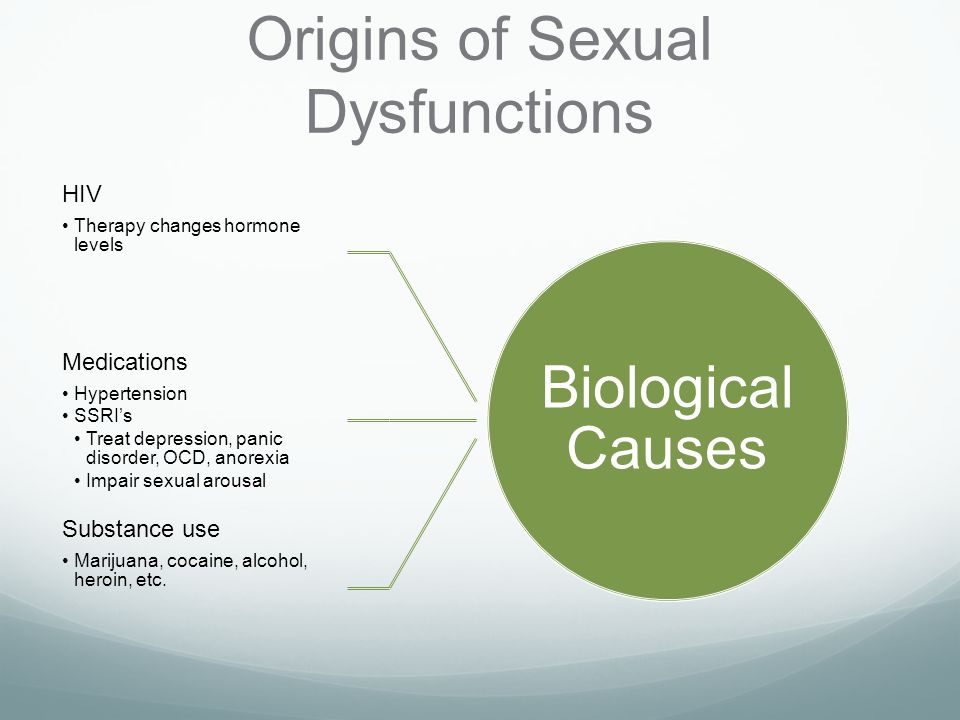

- loss of libido (reduced sex drive)

- difficulty achieving orgasm during sex or masturbation

- in men, difficulty obtaining or maintaining an erection (erectile dysfunction)

You'll usually need to see your doctor every few weeks when you first start taking SSRIs to discuss how well the medicine is working. You can also contact your doctor at any point if you experience any troublesome or persistent side effects.

You can also contact your doctor at any point if you experience any troublesome or persistent side effects.

Types of SSRIs

There are currently 8 SSRIs prescribed in the UK:

- citalopram (Cipramil)

- dapoxetine (Priligy)

- escitalopram (Cipralex)

- fluoxetine (Prozac or Oxactin)

- fluvoxamine (Faverin)

- paroxetine (Seroxat)

- sertraline (Lustral)

- vortioxetine (Brintellix)

Page last reviewed: 8 December 2021

Next review due: 8 December 2024

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors - StatPearls

Continuing Education Activity

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a class of medications most commonly prescribed to treat depression. They are often used as first-line pharmacotherapy for depression and numerous other psychiatric disorders due to their safety, efficacy, and tolerability. This activity will highlight the mechanism of action, adverse event profile, and other key factors (e.g., off-label uses, dosing, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, monitoring, relevant interactions) pertinent for members of the interprofessional team in the care of patients with depression and other psychiatric disorders for which SSRIs are indicated.

They are often used as first-line pharmacotherapy for depression and numerous other psychiatric disorders due to their safety, efficacy, and tolerability. This activity will highlight the mechanism of action, adverse event profile, and other key factors (e.g., off-label uses, dosing, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, monitoring, relevant interactions) pertinent for members of the interprofessional team in the care of patients with depression and other psychiatric disorders for which SSRIs are indicated.

Objectives:

Identify the indications for SSRIs.

Describe the most common adverse effects of SSRIs.

Review the mechanism of action of SSRIs.

Explain the importance of collaboration and communication amongst the interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients receiving SSRIs.

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Indications

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a class of medications most commonly prescribed to treat depression. They are often used as first-line pharmacotherapy for depression and numerous other psychiatric disorders due to their safety, efficacy, and tolerability. They are approved for use in both adult and pediatric patients.[1]

They are often used as first-line pharmacotherapy for depression and numerous other psychiatric disorders due to their safety, efficacy, and tolerability. They are approved for use in both adult and pediatric patients.[1]

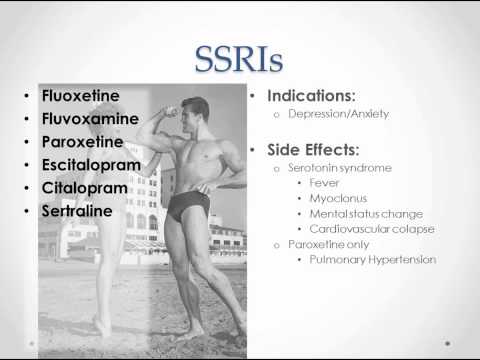

The current SSRIs in use in the United States are:

Fluoxetine

Sertraline

Paroxetine

Fluvoxamine

Citalopram

Escitalopram

Vilazodone

SSRIs currently have FDA labeled indications to treat the following conditions:

Major depressive disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder

Bulimia nervosa

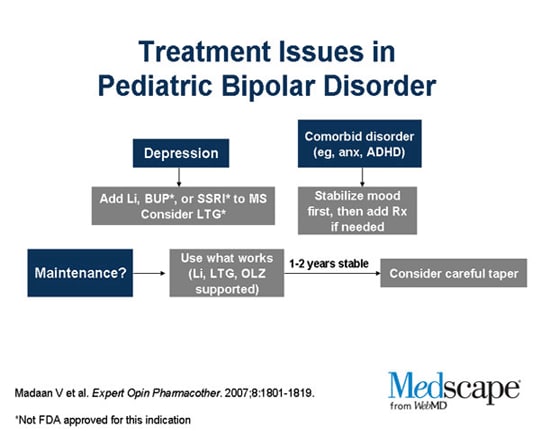

Bipolar depression[2]

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Panic disorder

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

Treatment-resistant depression

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Social anxiety disorder

Other off-label uses include but are not limited to: Binge eating disorder, Body dysmorphic disorder, fibromyalgia, premature ejaculation, paraphilias, autism, Raynaud phenomenon, and vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. [3]

[3]

Mechanism of Action

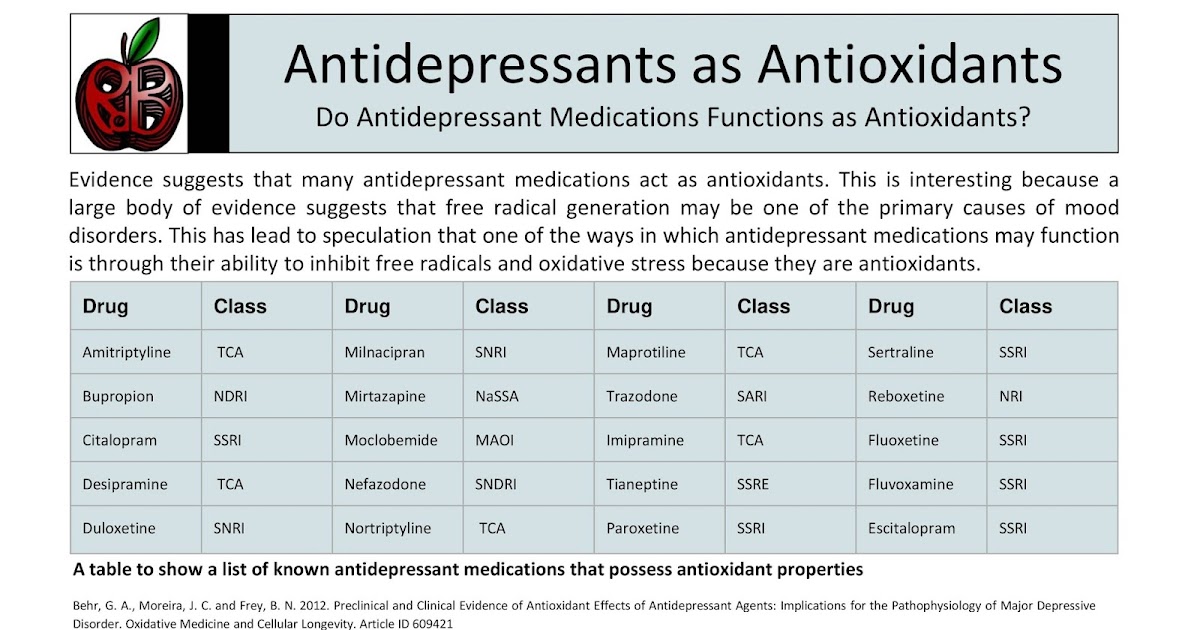

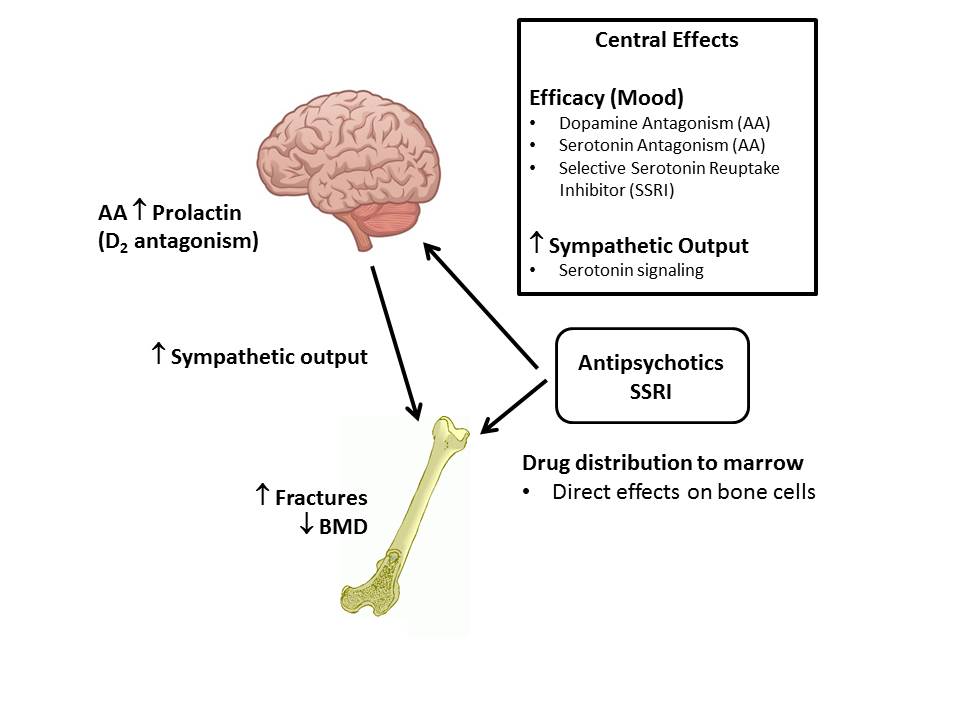

The therapeutic actions of SSRIs have their basis on increasing deficient serotonin that researchers postulate as the cause of depression in the monoamine hypothesis. As the name suggests, SSRIs exert action by inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin, thereby increasing serotonin activity. Unlike other classes of antidepressants, SSRIs have little effect on other neurotransmitters, such as dopamine or norepinephrine. SSRIs also have relatively fewer side effects than TCAs and MAOIs due to fewer effects on adrenergic, cholinergic, and histaminergic receptors.

SSRIs inhibit the serotonin transporter (SERT) at the presynaptic axon terminal. By inhibiting SERT, an increased amount of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5HT) remains in the synaptic cleft and can stimulate postsynaptic receptors for a more extended period.[4][5][6]

Administration

SSRIs are only available orally and come in multiple forms, including tablets, capsules, or liquid suspension/solution. There are currently no parenteral (IV, IM, SubQ), rectal, or other forms of SSRIs. SSRI administration is typically once-daily medication in the morning or nighttime. Except for vilazodone, SSRIs may be taken without regard to food. Vilazodone should be administered with food.[6]

There are currently no parenteral (IV, IM, SubQ), rectal, or other forms of SSRIs. SSRI administration is typically once-daily medication in the morning or nighttime. Except for vilazodone, SSRIs may be taken without regard to food. Vilazodone should be administered with food.[6]

Adverse Effects

The popularity and widespread use of SSRIs is due in part to their relatively fewer side effects than prior commonly used antidepressants such as TCAs and MAOIs. SSRIs have little or no effect on dopamine, norepinephrine, histamine, or acetylcholine (except for paroxetine). This characteristic leads to fewer complaints of side effects such as xerostomia, sedation, constipation, urinary retention, and cognitive impairments.[7][8]

Increased tolerability compared to other classes of medications make SSRIs first-line options for their indicated uses. Although relatively safer due to their selectiveness for serotonin, SSRIs are not without risks.

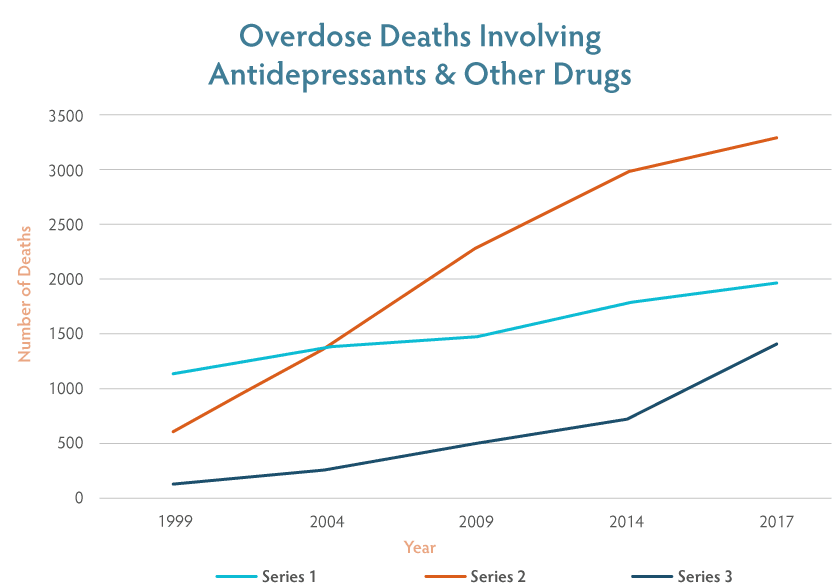

In 2004, the FDA issued a black box warning for SSRIs and other antidepressant medications due to a possible increased risk of suicidality among pediatric and young adult (up to age 25) populations. The risk and benefits of initiating SSRI therapy on acutely suicidal patients must be weighed, keeping in mind that depression itself is a large risk factor for suicidality and requires treatment. Common side effects from SSRIs include sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbances, weight changes, anxiety, dizziness, xerostomia, headache, and gastrointestinal distress.[9][10]

The risk and benefits of initiating SSRI therapy on acutely suicidal patients must be weighed, keeping in mind that depression itself is a large risk factor for suicidality and requires treatment. Common side effects from SSRIs include sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbances, weight changes, anxiety, dizziness, xerostomia, headache, and gastrointestinal distress.[9][10]

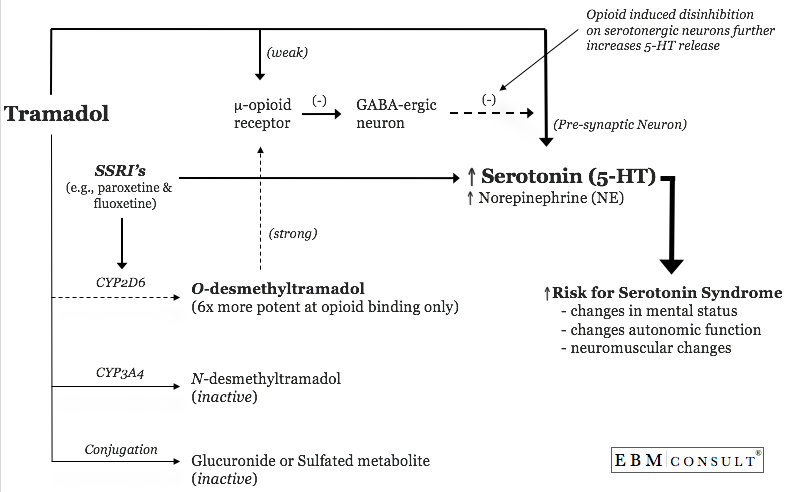

SSRIs also have the potential to prolong the QT interval, which can lead to fatal arrhythmia, torsade de pointes. Citalopram has correlations with a longer QT duration than the other medications in this class.[11][12] Coagulopathy also correlates with SSRI use.[13] Although infrequent, as with all medications that increase serotonin activity, it is important to be aware of the risk of serotonin syndrome, particularly when prescribing multiple medications that may have serotonergic effects.

SSRIs are metabolized by and have effects on the cytochrome P450 system. Fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram are inhibitors of CYP2D6. Fluoxetine and fluvoxamine are inhibitors of CYP2C19. Fluvoxamine is an inhibitor of CYP1A2.[6]

Fluoxetine and fluvoxamine are inhibitors of CYP2C19. Fluvoxamine is an inhibitor of CYP1A2.[6]

Contraindications

SSRIs are contraindicated with the concurrent use of MAOIs, linezolid, and other medications that increase serotonin levels and could put patients at risk for life-threatening serotonin syndrome.

Paroxetine is contraindicated in pregnancy and is classified as category D/X due to its teratogenic effects in causing cardiovascular defects, specifically cardiac malformations if prescribed in the first trimester.[14]

Monitoring

The effect of SSRIs may take up to 6 weeks before the patients feel the effects of treatment.[15] If patients tolerate the current dose well, the clinician can consider an increase in dosage after several weeks.

All patients under the age of 25 should be continually assessed for suicidal ideation and other unusual behaviors, as highlighted in the FDA black box warning for all SSRI medications.

For patients with cardiac risk factors, an EKG may be an option to monitor for QT prolongation and arrhythmias.

Weight should be regularly measured and tracked to determine any adverse metabolic changes, and vital signs should also be regularly measured to monitor for adverse changes.

Anxiety, insomnia, and sexual dysfunction (delayed ejaculation, decreased sexual desire, and anorgasmia) require regular assessment.

Toxicity

SSRI overdose is relatively infrequent due to their increased safety profile and tolerability compared to other classes of antidepressants. SSRI overdoses are rarely fatal and usually do not have serious consequences. Out of all the SSRIs, citalopram and escitalopram are more likely to cause overdose due to differences in their structures. Citalopram and escitalopram have an increased risk of cardiotoxicity due to QT prolongation, which can progress to serious arrhythmias such as Torsades.

Serotonin syndrome is a life-threatening consequence of increased serotonergic activity. It can result from overdosing on SSRIs or from combining multiple medications that increase serotonin levels. Serotonin syndrome is characterized by mental status changes, autonomic dysfunction, and dystonias. Findings may include agitation, tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, hyperreflexia, tremor, nausea, vomiting, and clonus.[16] Serotonin syndrome may present similarly to neuroleptic malignant syndrome and malignant hyperthermia. This is especially important to keep in mind since commonly prescribed psychiatric medications can cause both serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. In general, serotonin syndrome is distinguishable by taking a thorough history. Serotonin syndrome also has a rapid onset and resolution. There is no definitive treatment for serotonin syndrome aside from discontinuing the offending agent, supportive measures, and benzodiazepines for agitation. Cyproheptadine has shown some success in several small studies and case reports for patients who do not respond to initial treatment.

Serotonin syndrome is characterized by mental status changes, autonomic dysfunction, and dystonias. Findings may include agitation, tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, hyperreflexia, tremor, nausea, vomiting, and clonus.[16] Serotonin syndrome may present similarly to neuroleptic malignant syndrome and malignant hyperthermia. This is especially important to keep in mind since commonly prescribed psychiatric medications can cause both serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. In general, serotonin syndrome is distinguishable by taking a thorough history. Serotonin syndrome also has a rapid onset and resolution. There is no definitive treatment for serotonin syndrome aside from discontinuing the offending agent, supportive measures, and benzodiazepines for agitation. Cyproheptadine has shown some success in several small studies and case reports for patients who do not respond to initial treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

SSRIs are currently some of the most commonly prescribed medications. They are used to treat numerous conditions and may be used in many settings, not just in primary care or psychiatry. Patients may be on these medications for the long term. Therefore, it is essential to have accurate medication reconciliation by the entire interprofessional team, including clinicians, pharmacists, nursing staff, and other health professionals. This interprofessional approach to SSRI therapy will lead to better patient outcomes with fewer adverse events. [Level 5]

They are used to treat numerous conditions and may be used in many settings, not just in primary care or psychiatry. Patients may be on these medications for the long term. Therefore, it is essential to have accurate medication reconciliation by the entire interprofessional team, including clinicians, pharmacists, nursing staff, and other health professionals. This interprofessional approach to SSRI therapy will lead to better patient outcomes with fewer adverse events. [Level 5]

Serotonin syndrome is important to keep in mind due to the widespread use of SSRIs. If suspected by a triage nurse in an emergency setting, it is important that the emergency medicine physician immediately begin supportive treatment. Coordinating with the intensivist and ICU nursing staff may also be required as treatment may require immediate sedation and intubation. A neurologist may also be important for ongoing care. Although there is no definitive treatment for serotonin syndrome, researchers have trialed cyproheptadine with some success in small studies and case reports. [17][18][19][20] [Level 4]

[17][18][19][20] [Level 4]

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

References

- 1.

DeLucia V, Kelsberg G, Safranek S. Which SSRIs most effectively treat depression in adolescents? J Fam Pract. 2016 Sep;65(9):632-4. [PubMed: 27672691]

- 2.

Antosik-Wójcińska AZ, Stefanowski B, Święcicki Ł. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant's use in the treatment of depressive episodes in bipolar disorder - review of research. Psychiatr Pol. 2015;49(6):1223-39. [PubMed: 26909398]

- 3.

Coleiro B, Marshall SE, Denton CP, Howell K, Blann A, Welsh KI, Black CM. Treatment of Raynaud's phenomenon with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001 Sep;40(9):1038-43. [PubMed: 11561116]

- 4.

Feighner JP. Mechanism of action of antidepressant medications. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60 Suppl 4:4-11; discussion 12-3.

[PubMed: 10086478]

[PubMed: 10086478]- 5.

Xue W, Wang P, Li B, Li Y, Xu X, Yang F, Yao X, Chen YZ, Xu F, Zhu F. Identification of the inhibitory mechanism of FDA approved selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: an insight from molecular dynamics simulation study. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2016 Jan 28;18(4):3260-71. [PubMed: 26745505]

- 6.

Preskorn SH. Clinically relevant pharmacology of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. An overview with emphasis on pharmacokinetics and effects on oxidative drug metabolism. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32 Suppl 1:1-21. [PubMed: 9068931]

- 7.

Hirschfeld RM. Efficacy of SSRIs and newer antidepressants in severe depression: comparison with TCAs. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999 May;60(5):326-35. [PubMed: 10362442]

- 8.

Kocsis JH. Review: SSRIs and TCAs equally effective at treating chronic depression and dysthemia; SSRIs are associated with fewer adverse events than TCAs. Evid Based Ment Health. 2013 Aug;16(3):82.

[PubMed: 23604275]

[PubMed: 23604275]- 9.

David DJ, Gourion D. [Antidepressant and tolerance: Determinants and management of major side effects]. Encephale. 2016 Dec;42(6):553-561. [PubMed: 27423475]

- 10.

Hu XH, Bull SA, Hunkeler EM, Ming E, Lee JY, Fireman B, Markson LE. Incidence and duration of side effects and those rated as bothersome with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment for depression: patient report versus physician estimate. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004 Jul;65(7):959-65. [PubMed: 15291685]

- 11.

Funk KA, Bostwick JR. A comparison of the risk of QT prolongation among SSRIs. Ann Pharmacother. 2013 Oct;47(10):1330-41. [PubMed: 24259697]

- 12.

Beach SR, Kostis WJ, Celano CM, Januzzi JL, Ruskin JN, Noseworthy PA, Huffman JC. Meta-analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-associated QTc prolongation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014 May;75(5):e441-9. [PubMed: 24922496]

- 13.

Laporte S, Chapelle C, Caillet P, Beyens MN, Bellet F, Delavenne X, Mismetti P, Bertoletti L.

Bleeding risk under selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Pharmacol Res. 2017 Apr;118:19-32. [PubMed: 27521835]

Bleeding risk under selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Pharmacol Res. 2017 Apr;118:19-32. [PubMed: 27521835]- 14.

Susser LC, Sansone SA, Hermann AD. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for depression in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Dec;215(6):722-730. [PubMed: 27430585]

- 15.

Taylor MJ, Freemantle N, Geddes JR, Bhagwagar Z. Early onset of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant action: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Nov;63(11):1217-23. [PMC free article: PMC2211759] [PubMed: 17088502]

- 16.

Perry PJ, Wilborn CA. Serotonin syndrome vs neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a contrast of causes, diagnoses, and management. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012 May;24(2):155-62. [PubMed: 22563571]

- 17.

Graudins A, Stearman A, Chan B. Treatment of the serotonin syndrome with cyproheptadine. J Emerg Med.

1998 Jul-Aug;16(4):615-9. [PubMed: 9696181]

1998 Jul-Aug;16(4):615-9. [PubMed: 9696181]- 18.

Baigel GD. Cyproheptadine and the treatment of an unconscious patient with the serotonin syndrome. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2003 Jul;20(7):586-8. [PubMed: 12884999]

- 19.

Horowitz BZ, Mullins ME. Cyproheptadine for serotonin syndrome in an accidental pediatric sertraline ingestion. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999 Oct;15(5):325-7. [PubMed: 10532660]

- 20.

McDaniel WW. Serotonin syndrome: early management with cyproheptadine. Ann Pharmacother. 2001 Jul-Aug;35(7-8):870-3. [PubMed: 11485136]

The effect of antidepressants was predicted by changes in brain connections

How an antidepressant will act on a particular person can be determined by changes in the connections between different parts of his brain in the first days of using the drug, reported in iScience . According to the authors of the study, this method works for drugs with different mechanisms of action and is especially useful for assessing the effect of antidepressants, the therapeutic effect of which usually does not appear until a few weeks after the start of treatment.

Since the middle of the 20th century, it has been known that during depressive states, signaling is often impaired due to monoamine neurotransmitters, in particular serotonin. A large percentage of modern antidepressants normalize it by blocking the capture of serotonin molecules by neurons from the synaptic cleft, where this substance binds to the corresponding receptors. This, ultimately, ensures the normalization of the emotional state.

The concentration of many serotonin reuptake inhibitors already after the first doses rises to such values that should provide the desired effect, but it does not appear in the first few weeks of use. To explain this, different teams of scientists have determined which targets in cells are affected by certain drugs. However, significant links between the molecular mechanisms of action of specific antidepressants and the time after which their effect becomes noticeable (and whether it will manifest itself at all) have not yet been found.

Researchers at Yale and Manchester Universities, led by Chadi G. Abdallah, have proposed a different approach to predict the effectiveness of antidepressants by looking at how these drugs change the state of connections between different areas of the brain.

Abdallah and colleagues took as a basis the results of several studies by other groups of scientists, as well as their previous work. They showed that clinical depression weakens connections within the frontoparietal network involved in the control of attention and emotions, as well as between the frontoparietal network and the parietal areas of the dorsal attention network, which together provide attention to the environment. On the contrary, the connections within the network of passive brain work, which works when “immersed in oneself,” when a person has little interest in the outside world, are strengthened in clinical depression.

According to the hypothesis of Yale scientists, antidepressants, if they are effective for a particular person, should change the connections of the frontoparietal network and the network of passive brain work in the opposite way: strengthen them within the first and weaken them within the second. The researchers collected data on sertraline, one of the most commonly prescribed antidepressants that takes weeks to show effects, ketamine, a fast-acting potential antidepressant, and either placebo or lanicemin (which is similar in structure to ketamine) as controls.

The researchers collected data on sertraline, one of the most commonly prescribed antidepressants that takes weeks to show effects, ketamine, a fast-acting potential antidepressant, and either placebo or lanicemin (which is similar in structure to ketamine) as controls.

Researchers were interested in fMRI data obtained from patients with depression one week after the start of sertraline or placebo (99 and 103 people, respectively) or ketamine, lanicemin, or placebo (21, 20, and 19 people, respectively). The databases from which these data were taken also indicated how the behavior of patients changed during treatment, and in the case of sertraline, for the first seven days or more, it remained the same as before the start of the antidepressant course.

Scientists applied several predictive machine learning models to a sample of 1261 fMRI scans. The models analyzed the connectome (a set of connections) of the entire brain (not individual neurons, since the complete connectome of the human brain has not yet been read due to its complexity), or the connections of specific areas of the cortex and subcortical structures with each other, or only the connections of different parts of the cortex, and compared changes their strengths with changes in the behavior of patients during treatment.

Indeed, after the first dose of the drug, even before the patients' mood improved, sertraline strengthened connections between attention networks and weakened connections within the passive brain network. Similar was observed in the case of ketamine, but its effect was predicted by models with less accuracy. Placebos, which in some cases act on behavior in the same way as antidepressants (and this is one of the problems with drug testing for depression), did not have such effects.

The authors suggest that the strength of the connections within (and between) various brain systems that provide attention to the outside world or "withdrawal into oneself" is similarly affected by other slow-acting antidepressants like sertraline. And since this happens even before the therapeutic effect of these drugs is manifested, fMRI readings can determine the future effectiveness of a particular drug for a particular person.

The effect of antidepressants was also predicted in other ways: by electroencephalogram readings, blood tests, and even with the help of questionnaires.

Svetlana Yastrebova

Found a typo? Select the fragment and press Ctrl+Enter.

Serotonin, stay

Why the serotonin theory of depression is sinking, but antidepressants continue to work

Hippocrates and Galen believed that temperament, and even the mood of a person, depend on the balance of four fluids: black bile, yellow bile, lymph and blood. Black bile makes you sad, yellow makes you irritable, lymph makes you slow, and blood inspires confidence and optimism. In the Middle Ages, depression and other mental illnesses were attributed to demons and fought with them as with demons: prayer and asceticism. The Baroque "Anatomy of Melancholy" names poverty, fear and loneliness among the causes of the painful blues, the Enlightenment connects it with hereditary weakness of character. Then modernity begins: Emil Kraepelin includes melancholy among the symptoms of manic-depressive psychosis, and Freud declares pathological grief a consequence of "the loss of one's own "I"".

In 1952, Jean Delay and Pierre Deniker used chlorpromazine to treat psychosis and schizophrenia, and the era of psychopharmacology began. The first two antidepressants became cures for melancholia by accident. Imipramine was synthesized in 1951 as an antihistamine, but it turned out that the antiallergic drug eliminates tearfulness of a completely different nature. And iproniazid should have treated tuberculosis, but it cured sadness (we talked about it and other drugs that, in the end, do not treat what they were supposed to, in the material "Spin, wheel").

Studies have shown that both drugs act on biogenic amines, in particular norepinephrine and serotonin. Ipronizaide stops the enzyme monoamine oxidase, which breaks down serotonin and similar chemicals. Imipramine blocks the reuptake of serotonin after it is released into the synapse between neurons, allowing more serotonin to remain freely available in the brain. So, with the beginning of the "biological revolution" in psychiatry, the ancient theory of humor homeostasis came in handy - it was very well laid out in pills. Do antidepressants affect the level of amines in the brain and help patients? This means that these affective disorders are associated with a deficiency of substances that drugs make up for.

Do antidepressants affect the level of amines in the brain and help patients? This means that these affective disorders are associated with a deficiency of substances that drugs make up for.

The monoamine hypothesis was proposed by Joseph Schildkraut and Seymour Cathey in 1967. It was formulated very carefully: psychiatrists stipulated that amine metabolism disorders could be a consequence of depression, and not its cause; that is, it was a correlational rather than a causal hypothesis. And they concluded that "the confirmation of this hypothesis must ultimately depend on the direct demonstration of a biochemical abnormality [in patients]."

Attempts to produce such a demonstration, however, were not particularly successful: some experiments were carried out on small samples, others suffered from methodological flaws, and still others were not reproduced in people without a history of mental disorders.

Nevertheless, the myth of serotonin lived on and grew stronger.

Dreary simulacrum

In 1974, fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, was synthesized. In 14 years, he will reach the shelves under the name "Prozac". Popular culture will already be quite supportive of the idea of decomposing a person into chemicals in his brain, and the metaphysical soul will find a substrate in a dozen neurotransmitters. Dopamine, serotonin, endorphins, oxytocin, norepinephrine and others will become the molecules of happiness, euphoria, motivation, affection, attention and love. And if the aspirations of the soul are the "neurochemical self", then the diseases of the soul, obviously, are its imbalance. At 19in the 1990s, the pages of newspapers and street banners rustled in unison: “when there is not enough serotonin, you can suffer from depression”; "The cause of depression may be related to an imbalance of natural brain chemicals, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) correct this imbalance. "

"

The news of silver bullets for melancholy spread across the Earth. By the beginning of this century, psychologists estimated that most of their clients believed that depression was caused by a chemical imbalance of serotonin and other neurotransmitters that could be corrected with pills. Textbooks devoted sweeping sections to neurochemical theory, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) echoed marketers, and the bestseller Listening to Prozac popularized the idea of cosmetic psychopharmacology - the use of prescription drugs not to compensate for a pathological condition, but to "improve" the normal. And while critics of this idea were discussing with its supporters the ethics of drug control of the human psyche, practitioners continued to load passengers on board the serotonin liner. Since 2009By 2018, the use of antidepressants in the United States had increased by a third. And in Europe from 2000 to 2020 - and at all two and a half times.

And in 2022, the respected scientific journal Nature published an umbrella review, that is, a meta-analysis of meta-analyses, which fired a volley under the waterline of the majestic four-deck serotonin hypothesis. The relationship of depression with serotonin and its metabolites in blood plasma has not been confirmed. Wounded. In patients with depression, prior to the start of a course of SSRIs, the volume of serotonin in synapses may be higher than the healthy norm. Wounded. Experiments with tryptophan depletion, which leads to a decrease in serotonin, did not cause any outstanding sadness in the volunteers. Wounded. Searches for a link between serotonin transporter (SERT) gene variants and depression have also been unsuccessful. Killed.

The relationship of depression with serotonin and its metabolites in blood plasma has not been confirmed. Wounded. In patients with depression, prior to the start of a course of SSRIs, the volume of serotonin in synapses may be higher than the healthy norm. Wounded. Experiments with tryptophan depletion, which leads to a decrease in serotonin, did not cause any outstanding sadness in the volunteers. Wounded. Searches for a link between serotonin transporter (SERT) gene variants and depression have also been unsuccessful. Killed.

Killed?

In response to all this, the psychiatric community responds that the theory has long, if not always, been nothing more than an urban legend and a convenient metaphor for patients. And he adds that this is not the first time we are celebrating the funeral of a hypothesis: inconsistencies between the optimism of pharmaceutical companies and the skepticism of scientists were pointed out back in 2005. But while psychiatrists accuse each other of semantic tricks — that this is not even a hypothesis, but just a guess, and certainly not a full-blown scientific theory — the tens of millions of people aboard the ship that turned into a convenient metaphor are somewhat puzzled.

Why pills don't work

If the serotonin hypothesis fell into disgrace, does that mean antidepressants don't work? The review itself does not question the safety or efficacy of serotonergic drugs. Although, when discussing its results, many - including the authors of the meta-analysis themselves - move from the theory of chemical imbalance to the question of the effectiveness of pharmacological treatment.

This question makes no sense, if only because there is no agreed-upon way to distinguish a clinically significant treatment effect from a clinically insignificant one. The most common tool for evaluating the effectiveness of antidepressants in clinical trials is the Hamilton test (HDRS). This is a questionnaire that quantifies the severity of a depressive disorder by the severity of 21 of its symptoms: anxiety, low mood, insomnia and the like, up to suicidal tendencies and delirium.

Once endorsed by the US National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), an antidepressant effect of clinical significance is a three-point improvement on the Hamilton Scale (NICE does not presently present this threshold of clinical significance on its website, but this 3-5 point cut-off with a link to the institute wanders from article to article). At the same time, some researchers believe that the threshold of three points is too small, as it corresponds to the "lack of changes" in the patient's condition - the minimum improvement should be at least seven points. Others doubt the seven-point criterion, as it is unnecessarily overestimated, and instead of absolute values, they suggest that a 25-35 percent descent on the scale compared to the initial indicators be considered significant.

At the same time, some researchers believe that the threshold of three points is too small, as it corresponds to the "lack of changes" in the patient's condition - the minimum improvement should be at least seven points. Others doubt the seven-point criterion, as it is unnecessarily overestimated, and instead of absolute values, they suggest that a 25-35 percent descent on the scale compared to the initial indicators be considered significant.

Talking about the criteria for the effectiveness of antidepressants is also complicated by the fact that the traditional version of the Hamilton scale has acquired variations: the 17-item version of HAM-B17, the short version of HAM-D6, and the long versions of HAMD21 and HAMD24. And one can also argue about the validity of using different versions of the scale when determining remission indicators.

But the effectiveness of SSRIs, even in the midst of confusion over the boundaries of clinical significance, falls short of the most modest of them, achieving a difference with placebo of only two points.

This may be because, instead of correcting some imbalance, antidepressants cause conditions whose symptoms overlap those of depression and thus alleviate them. In the same way that alcohol can relieve the symptoms of social phobia - which does not mean that it eliminates the root cause of the phobia, which most certainly does not arise from a lack of ethanol in the body. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors often have a sedative effect, causing emotional numbness and indifference. And the Hamilton test, among other things, measures insomnia, anxiety, and arousal. Any drug with a pronounced sedative effect affects these indicators better than a placebo - and only due to this it can reduce the assessment of a person's state according to Hamilton by those same two points.

In addition to problems with efficacy criteria for pills, pharmacologists continue to have difficulties with the criterion of their ineffectiveness - placebo. The gap between the action of antidepressants and the placebo effect in clinical trials is getting narrower (read more about the placebo effect in the material "Lie to me if you can"). And it's not just that new drugs are bad.

And it's not just that new drugs are bad.

The proportion of patients responding to placebo in antidepressant trials has steadily increased over the past twenty years. Since the expansion of the diagnostic criteria for depression in DSM-III, clinical trials have begun to include patients with less severe symptoms - and they are more susceptible to the placebo effect. The myth of chemical imbalance reinforces the belief in melancholy pills. And the further, the more research participants hope for help from the pill, thereby endowing the dummy with effective power. (Similarly, placebo effects increase with cognitive behavioral therapy.)

Quite often, the side effects of antidepressants spoil the research data: their manifestation blinds clinical studies. If the control group gets just sugar balls, then the experimental group will very quickly understand what's what by the side effects. And experience an enhanced placebo effect: people believe that they suffer side effects not for nothing, but because the medicine works.

But even when differences in effect between drug and placebo approach zero, the effects themselves can be significant. In one of the experiments, patients were divided into three groups: some received antidepressants and underwent therapy, others received a placebo along with therapy, and others only went to therapy and did not take any pills. The mean improvement was 10.05, 7.59, respectively.and only 1.37 points on the Hamilton scale. The difference between a placebo and an antidepressant is negligible, but the difference between "there is a pill" or "there is no pill" is very noticeable.

So it's not worth writing off the placebo effect in the treatment of depression. Because even treatment with empty pills works with the feeling of hopelessness, which is one of the symptoms of depression. Although modern antidepressants are not as effective as many of us (medics included) think they are, they are. It's just that this efficiency is provided not only and not entirely biochemically.

We still don't really know exactly how antidepressants work. However, understanding the principle of drug operation is not always necessary for effective treatment; tablets often enter clinical practice long before the mechanism of their action is substantiated. We, for example, do not have a clear idea of how general anesthetics work, but this does not stop surgeons.

So, despite the solemn funeral of the serotonin hypothesis, in medical practice, most likely, nothing will change. On the contrary, this funeral should further spur the search for explanations of why serotonergic antidepressants work. That is, descriptions of the mechanisms of development of depression, based on which it would be possible to develop therapy.

All the more fortunate that the "post-serotonin" hypotheses of depression do not throw monoamines off the ship of history. And they are simply looking for the causes of the disease at a lower level.

Somewhat nervously

The failure of the monoamine hypothesis of Schildkraut and Katie eventually gave rise to a wave of new hypotheses. Ideas about a local disturbance in brain biochemistry have been replaced by versions about the role of brain-derived neurotrophic factors, neuroplasticity, excessive activation of the stress (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis, the participation of inflammatory cytokines, the intestinal microbiota, and the gut-brain axis. All of them are intertwined with each other into a ball, which can be unraveled from almost anywhere. In our case, the easiest way is to continue from the thread that stretches from the article that gave rise to the serotonin hypothesis, and the review that killed this hypothesis.

Ideas about a local disturbance in brain biochemistry have been replaced by versions about the role of brain-derived neurotrophic factors, neuroplasticity, excessive activation of the stress (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis, the participation of inflammatory cytokines, the intestinal microbiota, and the gut-brain axis. All of them are intertwined with each other into a ball, which can be unraveled from almost anywhere. In our case, the easiest way is to continue from the thread that stretches from the article that gave rise to the serotonin hypothesis, and the review that killed this hypothesis.

If you open the original article by Schildkraut and Katie, you can see that they are not talking about directly reducing depression to biochemistry, but rather adding biochemistry to all other causes of this disease - in general, laying the foundation for a biopsychosocial model of depression. According to her, depression and other mental disorders are caused by a complex interplay of genetic, neurochemical, and social factors.

View quote ↓

“... a catecholamine abnormality does not necessarily imply a genetic rather than an environmental or psychological etiology of depression [...] it is equally possible that early experiences [...] may cause permanent biochemical changes and may predispose some people to depression in adulthood [...] any comprehensive formulation of the physiology of the condition must include many other concomitant biochemical, physiological and psychological factors ".

Half a century later, the authors of the "anti-serotonin" article invite their colleagues to take a closer look at the social causes of depression, from the study of which they were distracted by the search for a chemical recipe for sadness.

The number of stressors—such as job loss, relationship breakdown, or illness—predicts the likelihood of developing depression. At the same time, a stressful event is enough to increase the probability of a depressive episode by one and a half times. In addition, it is assumed that stress can negate the effect of treatment, be associated with a worse prognosis for depression and an increased risk of relapse.

In addition, it is assumed that stress can negate the effect of treatment, be associated with a worse prognosis for depression and an increased risk of relapse.

The role of stress in the development of melancholia is also indirectly indicated by the presence of secondary depression in endocrine diseases. For example, in Cushing's syndrome, the level of stress hormones in the blood is chronically elevated: cortisol or related glucocorticoids. Approximately half of patients with Cushing's syndrome experience symptoms of depression.

The physiological basis for this version is the glucocorticoid hypothesis of depression, first formulated in 1976. The causal chain between stress and depression looks like this:

- When a person finds himself in a stressful situation, a large amount of cortisol enters the bloodstream and this is not very useful for hippocampal neurons. Under the influence of cortisol, fewer neurons, synapses and processes are formed, and nerve cells begin to die more often.

- The death of neurons leads to disruption of important mechanisms of the hippocampus: long-term potentiation, that is, a steady increase in signal transmission between neurons, and depression, a weakening of signal transmission.

- Due to the fact that the hippocampus is acting up, inhibition of the stress axis is reduced. The axis unwinds more and more, cortisol becomes more and more, it acts more and more persistently on the hippocampus - this is how the vicious circle closes and moves in a downward spiral with each cycle, exhausting the hippocampus.

- In addition, chronic stress also thins the prefrontal cortex and blunts dopamine, also known as the “happiness hormone.”

Cortisol-induced brain changes are consistent with what is seen on functional MRI in patients with major depressive disorder: the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex are depleted, and the amygdala is an emotional processing center often associated with anxiety, fear and unpleasant experiences, - on the contrary, it becomes overly active and grows. Stress drives the brain to despair, slowing down the maturation of neurons, destroying nerve cells and disrupting the connection between them. And, therefore, the glucocorticoid hypothesis becomes neuroplastic.

Stress drives the brain to despair, slowing down the maturation of neurons, destroying nerve cells and disrupting the connection between them. And, therefore, the glucocorticoid hypothesis becomes neuroplastic.

Why pills work

The nervous system is plastic - it can adapt to stimuli. Somewhere it creates new neurons, somewhere it changes the length and branching of their processes, it can strengthen or weaken synaptic signal transmission, or even completely destroy some nerve endings. All this division, branching and maturation is regulated and maintained by special neurotrophin proteins - in particular, the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).

Neuroplasticity is indispensable for adapting the brain to stress, and its failures may underlie various mental disorders. In depression with neuroplasticity, it is not too smooth: in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, the gray matter of the brain becomes thinner in patients, the connectivity and branching of nerve endings decrease. In addition, the concentration of neurotrophic factors also decreases.

In addition, the concentration of neurotrophic factors also decreases.

The neuroplastic hypothesis is primarily based on the assumption that "cortisol" depression caused by stress is associated with a decrease in the level of the BDNF factor in the hippocampus. This idea is also attractive because drugs that target BDNF have similar effects to antidepressants.

The neuroplastic hypothesis has a second merit — it explains why serotonergic antidepressants do work.

BDNF synthesis is regulated by serotonin. And serotonergic antidepressants increase the release of serotonin into the synaptic cleft, where it acts on monoamine receptors. This is how a whole cascade of reactions begins that reach the nucleus of nerve cells and start the synthesis of brain-derived neurotrophic factor there. It, in turn, spurs the processes of plasticity and resistance to damaging influences. By acting on serotonin receptors in the hippocampus, antidepressants also spur the formation of new neurons and enhance signaling between them.

An increase in the synthesis of neurotrophic factors in the brain, an increase in signals between neurons, neurogenesis - all this is not a quick thing, so the neuroplastic theory well explains the long, up to eight weeks, period of unfolding the effect of antidepressants.

But there is a weakness in this argument ↓

BDNF promotes neuroplasticity and neurogenesis indiscriminately, and in addition to helping depression sufferers in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, it would also help the amygdala. And the activity of this structure can provoke depressive behavior or aggravate symptoms.

The very possibility of getting into the mechanism of work of serotonergic antidepressants through the activation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor suggests where it is worth looking for a faster and more unbranched path in the treatment of depression.

Nasal joy

Monoamine receptors, which are affected by serotonin, include glutamate receptors. Glutamate is one of the main mediators that regulate brain neuroplasticity. The release of glutamate can cause a rapid increase in neuronal connectivity (long-term potentiation), promote the formation of synapses. Blocking some glutamate receptors (NMDA) and activating others (AMPA) promote the expression of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene.

Glutamate is one of the main mediators that regulate brain neuroplasticity. The release of glutamate can cause a rapid increase in neuronal connectivity (long-term potentiation), promote the formation of synapses. Blocking some glutamate receptors (NMDA) and activating others (AMPA) promote the expression of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene.

The fact that 85 percent of the mass of the brain consists of the neocortex, and glutamate is its main neurotransmitter, can also speak in favor of the glutamate hypothesis. So, to put it simply, the brain is a glutamatergic machine, and cognitive functions and emotions in such an optics become derived from the excitation of neurons by glutamate or their inhibition by gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). At the same time, studies reveal in patients with depression disturbances in the level of glutamate in the blood, cerebrospinal fluid and brain, anomalies in the level of expression of subunits of glutamate receptors.

In 2000, the relatively well-known club dissociative ketamine, the glutamate receptor agonist (NMDA), was first demonstrated to have an antidepressant effect. It acts directly on the receptor, while serotonin reuptake inhibitors only indirectly regulate its work. Simply put, ketamine follows the same path as SSRIs, but cut corners. An injection of ketamine relieves melancholy in just a few hours, and the effect itself lasts from several days to weeks.

It acts directly on the receptor, while serotonin reuptake inhibitors only indirectly regulate its work. Simply put, ketamine follows the same path as SSRIs, but cut corners. An injection of ketamine relieves melancholy in just a few hours, and the effect itself lasts from several days to weeks.

The ketamine enantiomer esketamine ((S)-ketamine) is now being used as adjunct therapy to oral antidepressants. In clinical studies, esketamine nasal spray reduced suicidal thoughts in depressed patients. Since 2019, its use has been approved in the United States as an additional treatment for treatment-resistant depression, and since 2020 for the treatment of patients at risk of suicide.

Esketamine faces the same criticism as serotonergic antidepressants. We do not have an exact explanation of its mechanism of action. Potential but unproven mechanisms include: release of glutamate, inhibition of NMDA receptors, inhibition of spontaneous NMDA currents in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, activation of AMPA glutamate receptors with subsequent expression of the brain trophic factor. Clinical trials are also not smooth: the FDA approved the drug despite the fact that four out of five phase 3 clinical trials did not reveal differences in the effect of esketamine with placebo.

Clinical trials are also not smooth: the FDA approved the drug despite the fact that four out of five phase 3 clinical trials did not reveal differences in the effect of esketamine with placebo.

But even if the silver bullets for melancholy aimed at glutamate don't hit right on target, that's not too bad either. Just like with the serotonin hypothesis, failure will tell us something new about depression.

A tangle of ideas and data, wound around the monoamine hypothesis of Schilkraut and Katie, has become intertwined with the chronic stress hypothesis and has come down to the idea of a violation of neuroplasticity in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. From neuroplasticity, the thread stretched to neurotrophins. And from neurotrophins - led back to serotonin and glutamate. The glutamate hypothesis has given us new antidepressants that start almost immediately and seem to last long enough.

If this thread doesn't lead us anywhere else, we'll unwind another one.