Myside bias example

Only My Opinion Counts: Myside Bias

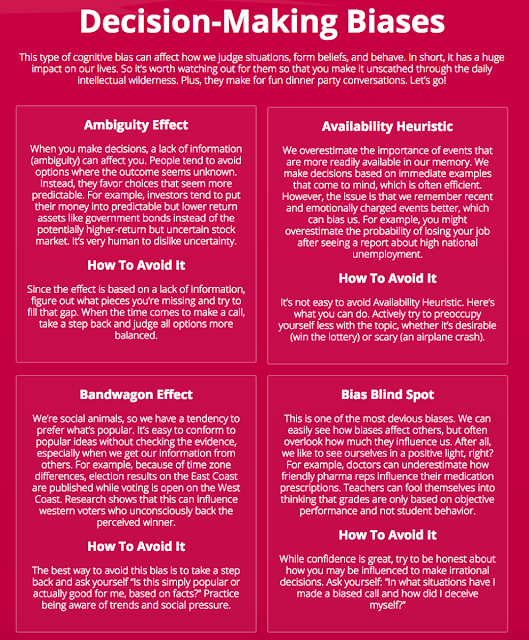

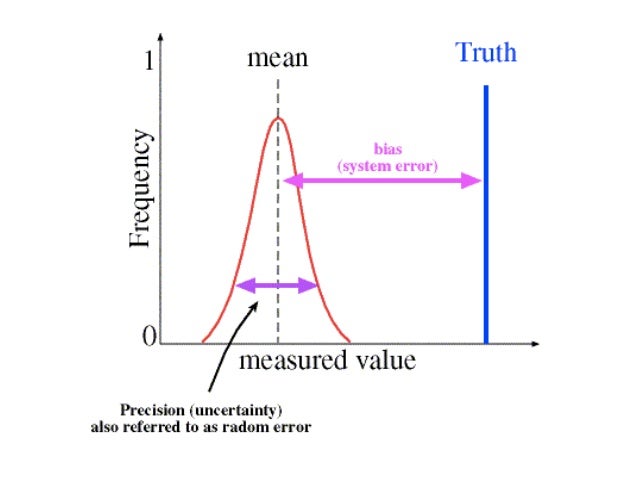

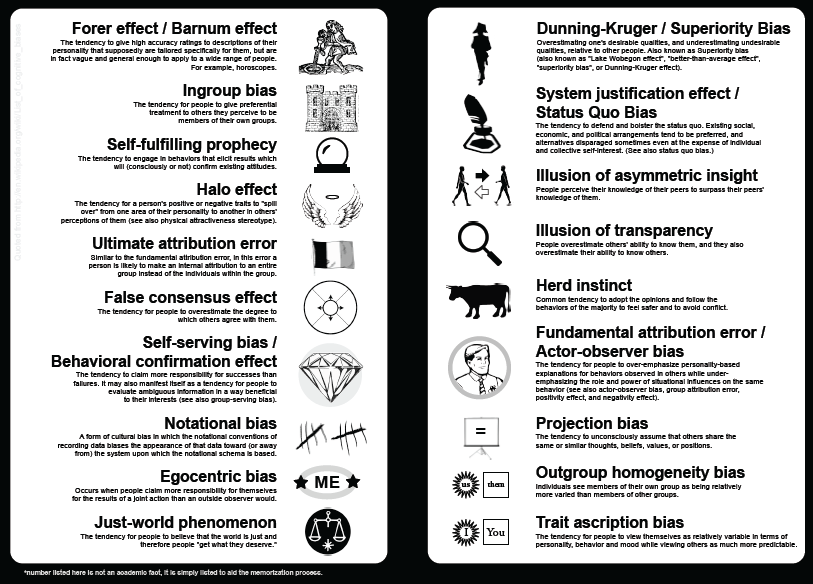

A common error that occurs with everyday thinking is Myside Bias — the tendency for people to evaluate evidence, generate evidence, and test hypotheses in a manner biased toward their own opinions.

Measures of intelligence, often considered synonymous with good thinking, do not assess the avoidance of myside bias (Stanovich & West, 2008; Sternberg, 2001). Intelligence (as measured by popular intelligence tests and their proxies) shows a weak association with avoidance of myside bias, and in some instances, particularly under conditions where explicit instructions have not been given to avoid myside bias, shows no association with the avoidance of this thinking error.

Intelligence & Myside Processing

Toplak & Stanovich (2003) presented 112 undergraduate university students with an informal reasoning test in which they were asked to generate arguments both for and against the position they endorsed on three separate issues.

Performance on the task was evaluated by comparing the number of arguments they generated which endorsed (myside arguments) and which refuted (otherside arguments) their own position on that issue. Participants generated more myside arguments than otherside arguments on all three issues, thus consistently showing a myside bias effect on each issue. Differences in cognitive ability were not associated with individual differences in myside bias. However, year in university was a significant predictor of myside bias. The degree of myside bias decreased systematically with year in university. Year in university remained a significant predictor of myside bias even when both cognitive ability and age were statistically partialled out.

Myside bias was displayed on all three issues, but there was no association in the level of myside bias shown across the different issues.

The researchers suggested that stronger myside bias is shown when issues are related to current beliefs:

[P]articipants showing a large myside bias on one issue did not necessarily display a large myside bias on the other two issues.

An explanation of this finding might be found in the concepts of the emerging science of memetics — the science of the epidemiology of idea-sized units called memes that are analogized to genes. Beliefs already stored in the brain are likely to form a structure that prevents contradictory beliefs from being stored (sometimes referred to over-assimilation).

Toplak and Stanovich suggested that, “it is not people who are characterized by more or less myside bias but beliefs that differ in the degree of belief bias they engender — that differ in how strongly they are structured to repel contradictory ideas.”

A negative correlation was found between year in school and myside bias. Lower myside bias scores were associated with length of time in university. This finding seems to suggest that higher education can meliorate rational thinking skills (at least some rational thinking skills) and lessens myside bias.

Stanovich and West (2007) conducted two experiments that investigated natural myside bias. In the two experiments involving a total of over 1,400 university students and eight different comparisons, very little evidence was found that participants of higher cognitive ability displayed less natural myside bias. Natural myside bias is the tendency to evaluate propositions in a biased manner when given no instructions to avoid doing so.

In the two experiments involving a total of over 1,400 university students and eight different comparisons, very little evidence was found that participants of higher cognitive ability displayed less natural myside bias. Natural myside bias is the tendency to evaluate propositions in a biased manner when given no instructions to avoid doing so.

Macpherson and Stanovich (2007) examined the predictors of myside bias in two informal reasoning paradigms. The results showed cognitive ability did not predict myside bias. It was concluded that “cognitive ability displayed near zero correlations with myside bias as measured in two different paradigms.”

In Part Two, we look at more research and factors that contribute to myside bias.

Is Myside Bias Irrational? A Biased Review of The Bias that Divides Us, Neil Levy

By SERRC on • ( 0 )

The Bias That Divides Us (2021) is about myside bias, the supposed bias whereby we generate and test hypotheses and evaluate evidence in a way that is biased toward our own prior beliefs. Myside bias prevents convergence in beliefs: if people evaluate evidence divergently, due to divergent prior beliefs, then two agents faced with exactly the same evidence may move further apart. Keith Stanovich thinks that this kind of divergence explains partisan polarization and prevents resolution of important political issues. He also thinks that myside bias is irrational. He offers solutions to the problems he diagnoses: we should set our priors at 0.5 in the kinds of circumstances in which myside bias is irrational…. [please read below the rest of the article].

Myside bias prevents convergence in beliefs: if people evaluate evidence divergently, due to divergent prior beliefs, then two agents faced with exactly the same evidence may move further apart. Keith Stanovich thinks that this kind of divergence explains partisan polarization and prevents resolution of important political issues. He also thinks that myside bias is irrational. He offers solutions to the problems he diagnoses: we should set our priors at 0.5 in the kinds of circumstances in which myside bias is irrational…. [please read below the rest of the article].

Image credit: MIT Press

Article Citation:

Levy, Neil. 2021. “Is Myside Bias Irrational? A Biased Review of The Bias that Divides Us.” Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective 10 (10): 31-38. https://wp.me/p1Bfg0-6d6.

🔹 The PDF of the article gives specific page numbers.

The Bias that Divides Us: The Science and Politics of Myside Thinking

Keith E. Stanovich

Stanovich

The MIT Press, 2021

256 pp.

These proposals are difficult to implement, as Stanovich no doubt would agree. Unsurprisingly, the book is shot through with his own biases. The last chapter, where the book is most overtly political, falls well below the standard of the rest: it is credulous toward crude take downs of contemporary ‘woke’ thought and to culture wars polemic. In other words, it exhibits the errors that can arise when someone gathers and evaluates evidence in ways that favor their own prior (political) beliefs. But the book is one worth taking very seriously, even if parts of it are not. The discussion of myside bias brings to it all the sophistication and intelligence that Stanovich has displayed throughout a long and influential career in psychology and the arguments and the conclusions it reaches deserve a wider hearing.

Myside Bias

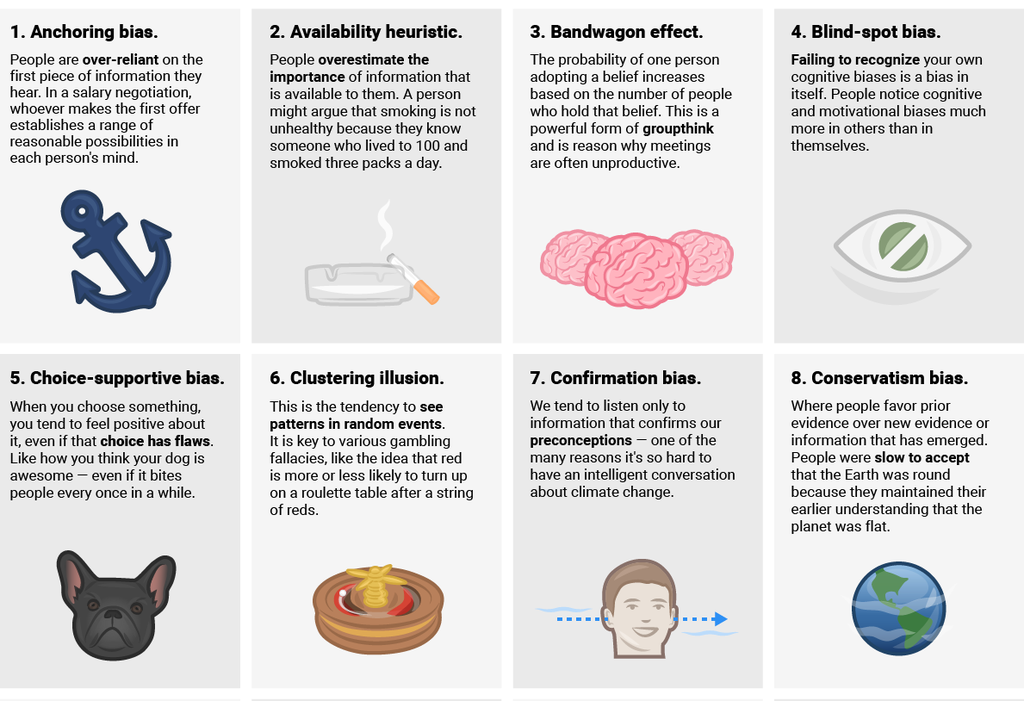

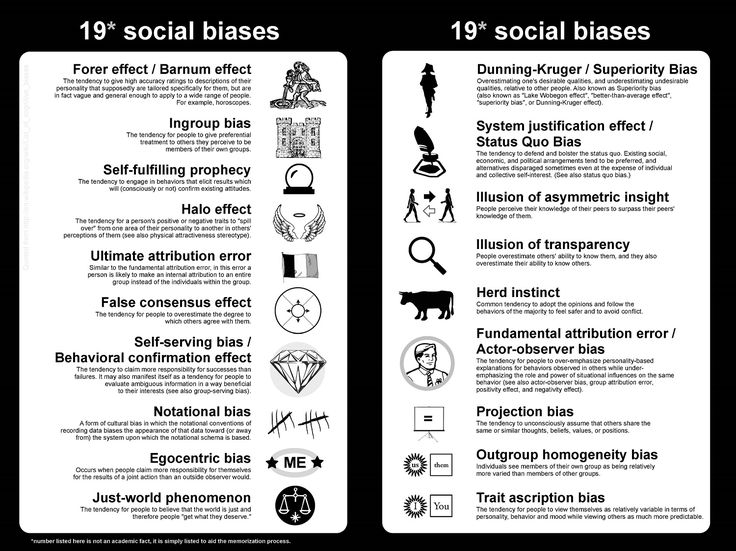

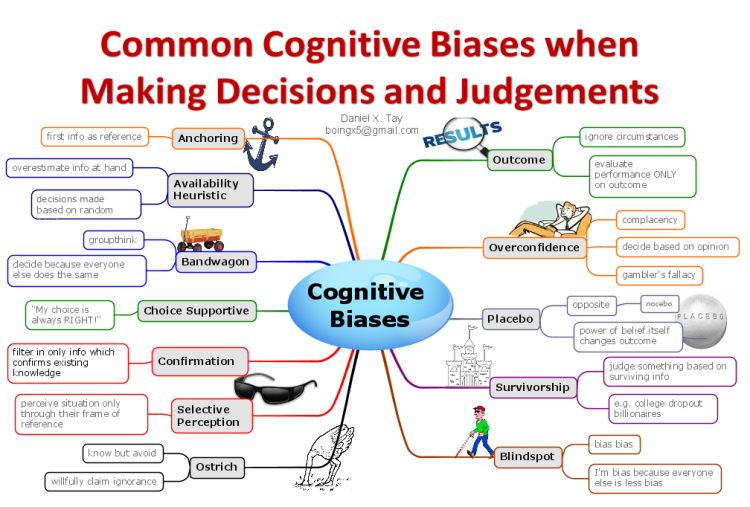

Myside bias is an especially important bias for us to consider, Stanovich argues. We, the readers of a forum like this, belong to what Stanovich calls the “cognitive elites. ” Most of us are very highly educated and we tend to score well above median on tests of intelligence. There’s good news for us elites: most biases correlate negatively with measures of cognitive functioning. Cognitive elites tend to do better on tests of belief bias (the bias whereby the validity of an argument is influenced by the truth of its conclusion). Similarly, cognitive elites display less anchoring bias and less hindsight bias. But cognitive elites do not display less myside bias (on some studies, cognitive elites actually display more myside bias). Myside bias is not only a very important bias, Stanovich argues, it is also a bias which rages at full strength in the readers of his book.

” Most of us are very highly educated and we tend to score well above median on tests of intelligence. There’s good news for us elites: most biases correlate negatively with measures of cognitive functioning. Cognitive elites tend to do better on tests of belief bias (the bias whereby the validity of an argument is influenced by the truth of its conclusion). Similarly, cognitive elites display less anchoring bias and less hindsight bias. But cognitive elites do not display less myside bias (on some studies, cognitive elites actually display more myside bias). Myside bias is not only a very important bias, Stanovich argues, it is also a bias which rages at full strength in the readers of his book.

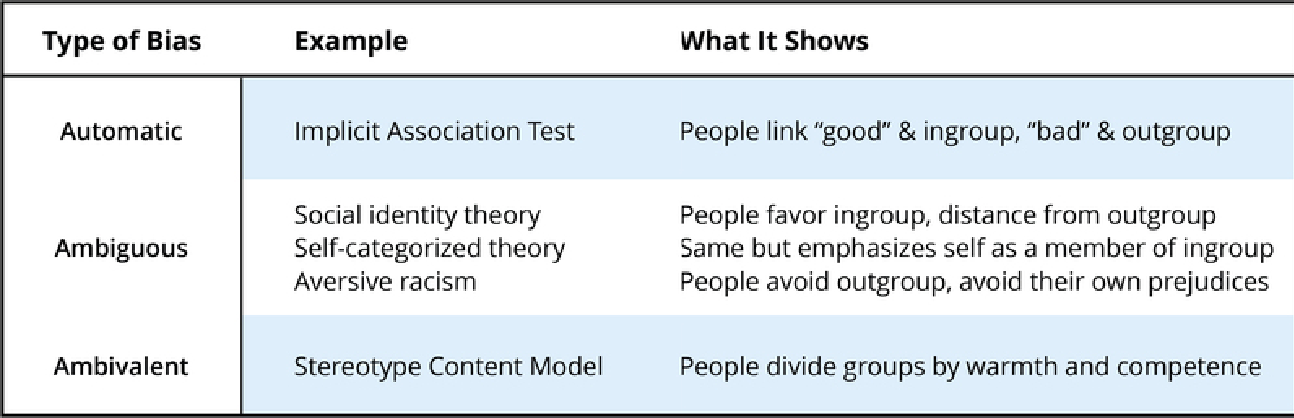

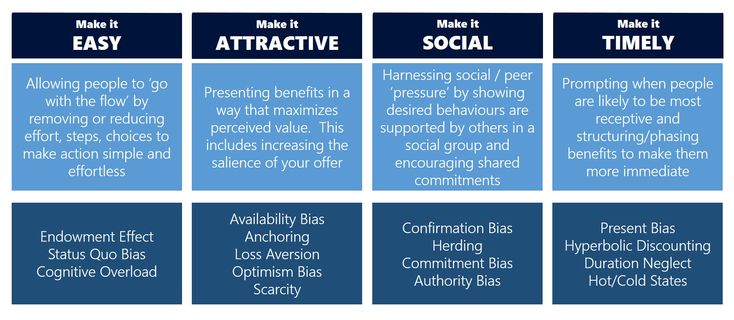

Stanovich stipulates he will use ‘myside bias’ to refer to a psychological disinclination to abandon a favored hypothesis. He distinguishes this from confirmation bias, which is often conflated with or held to be identical to myside bias. As he uses the term, the confirmation bias is a testing strategy: someone with that bias looks for evidence supportive of a focal hypothesis. As Stanovich points out, the confirmation bias (so understood) can be perfectly rational. There’s nothing wrong with looking for confirming evidence. It’s only when the confirmation bias leads to or is combined with myside bias that we see departures from rationality: that is, when we no longer deal appropriately with disconfirming evidence. Or so Stanovich suggests.

As Stanovich points out, the confirmation bias (so understood) can be perfectly rational. There’s nothing wrong with looking for confirming evidence. It’s only when the confirmation bias leads to or is combined with myside bias that we see departures from rationality: that is, when we no longer deal appropriately with disconfirming evidence. Or so Stanovich suggests.

But is he right? Is myside bias genuinely irrational? It’s hard to shake the idea that something is going wrong when people diverge in the face of one and the same body of evidence. A set of evidence can’t support p and ~p at one and the same time, it seems, yet such divergences occur time and time again in the lab, and seem ubiquitous outside it as well. As Stanovich shows, however, it’s surprisingly difficult to identify any rational failing on the part of any of the agents in many of the parade ground examples of divergent belief updating.

The key to seeing how divergent beliefs update on the same set of evidence may be rational is to apply Bayesian thinking. When an agent gets unexpected evidence that apparently disconfirms their prior belief, they must update their credences. But such updating is sensitive not only to their estimate of how likely the belief is, given the evidence, but also how likely the evidence is, given the belief. They may have stronger reason to regard the evidence as highly unreliable given their confidence in the belief than to appreciably lower their confidence in it. All by itself, this mechanism can explain why two agents may rationally move further apart in the face of the same evidence. If the agents have widely divergent credences in a hypothesis, then the one with lower confidence may move much further in response to apparently disconfirming evidence than the one with higher confidence. Many iterations of such occurrences can leave the party with widely divergent beliefs.

When an agent gets unexpected evidence that apparently disconfirms their prior belief, they must update their credences. But such updating is sensitive not only to their estimate of how likely the belief is, given the evidence, but also how likely the evidence is, given the belief. They may have stronger reason to regard the evidence as highly unreliable given their confidence in the belief than to appreciably lower their confidence in it. All by itself, this mechanism can explain why two agents may rationally move further apart in the face of the same evidence. If the agents have widely divergent credences in a hypothesis, then the one with lower confidence may move much further in response to apparently disconfirming evidence than the one with higher confidence. Many iterations of such occurrences can leave the party with widely divergent beliefs.

Moreover, such incidents can lead to evidence being preempted (see Begby, 2020) on future occasions. If a particular class of agents (say scientists, or Democrats, or opinion writers for Breitbart) regularly offer you evidence that you have good reason to think is unreliable in light of your priors, you may come to expect such (apparent) evidence from them. Expected evidence gives you no reason at all to update your beliefs. Accordingly, different groups of agents may rationally respond very differently to one and the same set of evidence. One agent may see the evidence as a strong reason to lower their confidence that p, another as a strong reason to lower their confidence that the source of the evidence is reliable and a third as presenting no reason to change their beliefs at all.

Expected evidence gives you no reason at all to update your beliefs. Accordingly, different groups of agents may rationally respond very differently to one and the same set of evidence. One agent may see the evidence as a strong reason to lower their confidence that p, another as a strong reason to lower their confidence that the source of the evidence is reliable and a third as presenting no reason to change their beliefs at all.

It follows, Stanovich points out, that myside processing can be rational. It can be rational to doubt the veracity of evidence rather than to update one’s credence in the focal hypothesis. He suggests that myside bias isn’t rational when probabilities are presented numerically, but that’s too quick. Participants in experiments may (rationally) discount the information experimenters provide them with. In such cases, they may not actually be asking the answering the question asked of them (“which conclusion does this data support”) but rather assessing the conclusion in the light of the plausibility, to them, of the evidence.

In any case, Stanovich recognizes that such experiments, with probabilities that are supposed to be accepted by all parties, are not good models for partisan polarization in the world outside the laboratory. Of course, Fox viewers and MSNBC viewers don’t accept the same data (about vaccine efficacy, say), so we can’t use these experiments to model their belief updating.

Nevertheless, Stanovich insists that myside bias is often irrational. Myside biased processing is rational only when the agent came by their priors honestly. In such cases, it’s rational to engage in what he calls “knowledge projection”; that is, in assessing new evidence in a way that is sensitive to your credences. But, too often, we don’t come by our priors honestly. They don’t arise from genuine evidence but rather reflect our ‘worldview’ or ‘convictions’. In such a case, knowledge projection is not rational, and such updating is not justifiable.

Honest Priors and Convictions

Stanovich never clearly spells out the distinction between honest priors and convictions. He seems to treat it as identical to another distinction he borrows from Abelson (1986), between testable and distal beliefs. The idea, roughly, is that testable beliefs are those that have arisen from evidence for or against them whereas distal can “neither be directly verified by experience, nor can they easily be confirmed by turning to evidence or scientific consensus” (8). In the latter class, Stanovich appears to lump all normative beliefs. Philosophers will of course be quick to point out that scientific theorising is itself shot through with normative assumptions. For instance, there is no normatively neutral way to balance the risk of false negatives versus that of false positives, so even when designing experiments or assessing evidence for some non-normative issue, we need to make decisions about which risk matters more, and this is an inherently normative task (Douglas, 2000).

He seems to treat it as identical to another distinction he borrows from Abelson (1986), between testable and distal beliefs. The idea, roughly, is that testable beliefs are those that have arisen from evidence for or against them whereas distal can “neither be directly verified by experience, nor can they easily be confirmed by turning to evidence or scientific consensus” (8). In the latter class, Stanovich appears to lump all normative beliefs. Philosophers will of course be quick to point out that scientific theorising is itself shot through with normative assumptions. For instance, there is no normatively neutral way to balance the risk of false negatives versus that of false positives, so even when designing experiments or assessing evidence for some non-normative issue, we need to make decisions about which risk matters more, and this is an inherently normative task (Douglas, 2000).

For this reason (but not for this reason alone), Stanovich’s claim that myside processing is rational when it reflects priors come by honestly seems vulnerable to a regress argument. How did I come to acquire my current credence that p? It may be true that it reflects many episodes of updating on evidence in the kind of way he approves of, but my initial credence was not a function of evidence. Rather, it is a function of some combination of developmentally canalized expectations and the social context which was formative for me.

How did I come to acquire my current credence that p? It may be true that it reflects many episodes of updating on evidence in the kind of way he approves of, but my initial credence was not a function of evidence. Rather, it is a function of some combination of developmentally canalized expectations and the social context which was formative for me.

Perhaps Stanovich would accept this point and distinguish between testable and distal beliefs on the basis of (often multitudinous) further episodes of updating that have occurred since this first shaping. It’s reasonable to believe that for a wide range of initial priors, we will approach a credence that matches reality given enough (good enough) evidence, so we needn’t worry too much about how our initial priors are set. Our testable beliefs will come to reflect good evidence, but our convictions may float free, insensitive to such evidence.

Stanovich situates the distinction between convictions and testable beliefs within a broader theory of what he calls memeplexes. Memes are selfish, in the same way that genes are selfish: the properties and conditions that favor their replication may dissociate from their hosts’ interests. Memeplexes are sets of memes that have an immune system: they are hostile to new credences that might conflict with them. I found this idea intriguing but both unnecessary and wholly unpersuasive. It is unnecessary because it doesn’t seem to do any explanatory work that the distinction between testable and distal beliefs doesn’t already do. Unpersuasive because Stanovich doesn’t provide, and I am unable to imagine, a mechanism whereby memeplexes with the capacity to recognize and fight off undesirable credences could develop (the only mechanism would seem to be myside bias itself, but insofar as memeplexes are supposed to underlie myside bias or explain its properties, we can’t invoke it without circularity).

Memes are selfish, in the same way that genes are selfish: the properties and conditions that favor their replication may dissociate from their hosts’ interests. Memeplexes are sets of memes that have an immune system: they are hostile to new credences that might conflict with them. I found this idea intriguing but both unnecessary and wholly unpersuasive. It is unnecessary because it doesn’t seem to do any explanatory work that the distinction between testable and distal beliefs doesn’t already do. Unpersuasive because Stanovich doesn’t provide, and I am unable to imagine, a mechanism whereby memeplexes with the capacity to recognize and fight off undesirable credences could develop (the only mechanism would seem to be myside bias itself, but insofar as memeplexes are supposed to underlie myside bias or explain its properties, we can’t invoke it without circularity).

Perhaps the true value of the memeplex idea for Stanovich isn’t explanatory. He believes that we can best avoid myside bias, in its irrational form, by distancing ourselves from our convictions, and thinking of them as memes that serve their own interests and not ours might provide the necessary distance. When we recognize we’re dealing with a conviction and not a testable belief, we should set our prior probability at 0.5 and evaluate new evidence accordingly.

When we recognize we’re dealing with a conviction and not a testable belief, we should set our prior probability at 0.5 and evaluate new evidence accordingly.

Science vs. Social Learning

The core of Stanovich’s view, then, is a distinction between credences which we formed on the basis of reliable evidence, either evidence we’ve gathered or the testimony of a scientific community, and those which we have not “thought our way to”; the distal beliefs we hold “largely as a function of our social learning within the valued groups to which we belong and our innate propensities to be attracted by certain types of ideas” (94). A great deal rests, therefore, on the claim that we have not “thought our way” to these distal convictions. Why should we believe that?

One reason Stanovich gives for thinking that we do not think our way to our convictions is that they are rarely things we have “consciously thought through and made an intentional decision to believe” (87). This, he suggests, is the ordinary view of our convictions: they are beliefs we hold as the upshot of conscious reflection and decision. I’m sceptical that this is the folk view: ordinary people are well aware that nonconscious cognition is common, and the thesis that beliefs cannot be voluntarily willed seems quite intuitive. In any case, there’s no reason for us, who are well aware that beliefs are often formed as the upshot of “largely unconscious social learning” (87), sometimes on the basis of developmentally canalized priors, to conclude that they are therefore irrational. For all that’s been said, largely unconscious social learning might lead to credences just as accurate as those shaped by conscious reflection.

This, he suggests, is the ordinary view of our convictions: they are beliefs we hold as the upshot of conscious reflection and decision. I’m sceptical that this is the folk view: ordinary people are well aware that nonconscious cognition is common, and the thesis that beliefs cannot be voluntarily willed seems quite intuitive. In any case, there’s no reason for us, who are well aware that beliefs are often formed as the upshot of “largely unconscious social learning” (87), sometimes on the basis of developmentally canalized priors, to conclude that they are therefore irrational. For all that’s been said, largely unconscious social learning might lead to credences just as accurate as those shaped by conscious reflection.

In fact, I suggest this is indeed the case. While Stanovich recognizes the importance of testimony (from scientists and other experts), his focus is largely on first-order evidence. We ought to form beliefs for ourselves, he suggests, not defer to the consensus. Much of the last chapter is devoted to exhorting us cognitive elites to be inconsistent, in the way in which non-elite people are. That is, rather than taking the lead of political actors and adopting the views they espouse across a range of (often very disparate) issues, we ought to follow the example of those who pay much less attention to political cues and adopt policy positions that mix and match conservative and liberal strands. We might agree with Democrats on climate change, but that’s no reason to follow their lead on gun control and the minimum wage and mandatory vaccines and affirmative action. Those people who identify strongly with political parties and are also political junkies defer across the board, but that’s irrational (Stanovich claims). Since partisan views reflect political necessity and jostling for votes, we do better either to follow the evidence for ourselves, or when we can’t gather it to set our priors at 0.5.

Much of the last chapter is devoted to exhorting us cognitive elites to be inconsistent, in the way in which non-elite people are. That is, rather than taking the lead of political actors and adopting the views they espouse across a range of (often very disparate) issues, we ought to follow the example of those who pay much less attention to political cues and adopt policy positions that mix and match conservative and liberal strands. We might agree with Democrats on climate change, but that’s no reason to follow their lead on gun control and the minimum wage and mandatory vaccines and affirmative action. Those people who identify strongly with political parties and are also political junkies defer across the board, but that’s irrational (Stanovich claims). Since partisan views reflect political necessity and jostling for votes, we do better either to follow the evidence for ourselves, or when we can’t gather it to set our priors at 0.5.

However, there are good reasons to think social referencing—taking epistemic cues from people who are not epistemic authorities, as well as those who are—is rational. There is plentiful evidence we defer to prestigious individuals (Chudek et al. 2012; Henrich and Gil-White 2001), to consensus or majority opinion and to individuals we identify with (Harris 2012; Levy 2019; Sperber et al. 2010). We defer in these kinds of ways because the opinions of others provide us with genuine evidence.

There is plentiful evidence we defer to prestigious individuals (Chudek et al. 2012; Henrich and Gil-White 2001), to consensus or majority opinion and to individuals we identify with (Harris 2012; Levy 2019; Sperber et al. 2010). We defer in these kinds of ways because the opinions of others provide us with genuine evidence.

The Epistemic Significance of Disagreement

We might best be able to bring this out through a consideration of the literature on the epistemic significance of disagreement (Christensen and Lackey 2013; Matheson 2015). The recognition that your epistemic peer disagrees with you about some moderately difficult issue provides you with a reason to lower your confidence in your belief. The disagreement is evidence that at least one of you has made a mistake, and you have no reason to think that it’s more likely that they’re mistaken than you are. Conciliationism—the thesis that we ought to reduce our confidence in the face of peer disagreement—has some seemingly unpalatable consequences, and philosophers have often tried to resist these implications by defining ‘epistemic peer’ narrowly. These philosophers accept that we should lower our confidence in peer disagreement cases, but argue that each of us has few epistemic peers, because few agents have precisely the same evidence and reasoning skills as you do (or, on another account, who are equally likely to be correct about the disputed issue, setting it and the issues it implicates aside).

These philosophers accept that we should lower our confidence in peer disagreement cases, but argue that each of us has few epistemic peers, because few agents have precisely the same evidence and reasoning skills as you do (or, on another account, who are equally likely to be correct about the disputed issue, setting it and the issues it implicates aside).

But this move is unsuccessful, because non-peer disagreement also provides us with some reason to conciliate. Suppose I add up a row of numbers and come to the conclusion they total 945. The discovery that the 28 individuals who have also attempted the sum have each independently come to the conclusion the total is 944 places me under rational pressure to conciliate, even if I am a maths whiz and they are all 5th graders. The numbers count, which indicates that each individual instance of dissent by a non-peer often provides me with some evidence (in Bayesian terms, I should reduce my confidence in my belief to some, perhaps small, degree even in one person cases, because I am not fully confident in my conclusion and my credence that this person is unreliable on problems like this is not sufficiently high). Conversely, peer and non-peer agreement also provides me with evidence (if those 28 5th graders each came to the same conclusion as me, my confidence in my response should rise).

Conversely, peer and non-peer agreement also provides me with evidence (if those 28 5th graders each came to the same conclusion as me, my confidence in my response should rise).

Of course, there are many complications to consider in assessing whether and how much non-peer disagreement provides us with evidence. Is the question one on which there is a body of specialized expertise that makes individuals who possess it significantly more reliable than those who do not? If so, does dissent or agreement stem from such an expert? If the person is a non-expert, to what degree is the question one on which non-experts are more likely than chance to be correct? Was their opinion reached independently of others? If not, are they at least somewhat discerning in echoing opinions (see Coady 2006 and Goldman 2001 for differing perspectives on this question)? Are they embedded in testimonial networks that contain or are anchored in expert opinion? I don’t have the space to discuss these many complications here. Nevertheless, it is very plausible that when political elites come to a view on an opinion outside the sphere of my expertise, I do better to defer to them than either to research the matter on my own or to be agnostic. These elites share my broad values, and therefore are likely to filter and weigh expert testimony in the sorts of ways in which I would, were I knowledgeable about the sources and implications of that testimony. They are likely plugged into testimonial networks that include or are sensitive to genuine expertise. Their public expression of their view exposes it to potential dissent by my fellow partisans, such that a lack of dissent indicates its plausibility. In adopting their view on the matter, I’m responding rationally to evidence.

Nevertheless, it is very plausible that when political elites come to a view on an opinion outside the sphere of my expertise, I do better to defer to them than either to research the matter on my own or to be agnostic. These elites share my broad values, and therefore are likely to filter and weigh expert testimony in the sorts of ways in which I would, were I knowledgeable about the sources and implications of that testimony. They are likely plugged into testimonial networks that include or are sensitive to genuine expertise. Their public expression of their view exposes it to potential dissent by my fellow partisans, such that a lack of dissent indicates its plausibility. In adopting their view on the matter, I’m responding rationally to evidence.

In response, Stanovich will surely and plausibly insist that this kind of deference must often lead us astray. He points out that political parties yoke together a variety of disparate and sometimes conflicting currents, such that those who are attracted to a party because they share some of its values but not others (say they share the GOP’s high valuation of traditional institutions, but not the same party’s high valuation of free markets) would find themselves adopting positions contrary to their own values in deferring to party elites. He also points to the fact that it’s highly unlikely that such party elites have true beliefs across the board, given the extrinsic pressures under which they adopt positions. All of this is true, but it shows neither that we do better epistemically to be agnostic or do our own research, on the one hand, or—more pointedly—that we’re not being rational in deferring.

He also points to the fact that it’s highly unlikely that such party elites have true beliefs across the board, given the extrinsic pressures under which they adopt positions. All of this is true, but it shows neither that we do better epistemically to be agnostic or do our own research, on the one hand, or—more pointedly—that we’re not being rational in deferring.

First accuracy. I can be confident that there are some issues on which my party is wrong and the opposition is right. But—since I’m an expert in so few of the topics on which they disagree—I have little to no sense which particular issues might be affected. On any particular issue, I do better—by my own lights—by adopting the party position than by being agnostic (I also do better, by my own lights, to defer than to do my own research, I believe: see Levy, forthcoming, for a defence).

In any case, we’re concerned here with the rationality of deference and not its accuracy. While rational cognition is non-accidentally linked to accurate cognition—the norms of rationality are justified because they are truth-conducive—rationality and accuracy often dissociate in particular cases. If my evidence is misleading, then rational belief update may lead me astray. We saw above how Bayesian reasoning may lead different agents rationally to diverge in response to one and the same set of evidence, after all. So pointing out that being guided by our convictions is guaranteed sometimes to lead us astray does not show that we’re irrational to be so guided. The opinions of party elites constitute genuine evidence for me, and it is rational for me to be guided by them. What goes for deference to party elites is true much more generally: we defer rationally when we engage in social referencing; that is, when our convictions are shaped by such cues (again, see Levy forthcoming).

If my evidence is misleading, then rational belief update may lead me astray. We saw above how Bayesian reasoning may lead different agents rationally to diverge in response to one and the same set of evidence, after all. So pointing out that being guided by our convictions is guaranteed sometimes to lead us astray does not show that we’re irrational to be so guided. The opinions of party elites constitute genuine evidence for me, and it is rational for me to be guided by them. What goes for deference to party elites is true much more generally: we defer rationally when we engage in social referencing; that is, when our convictions are shaped by such cues (again, see Levy forthcoming).

We see the dissociation between accuracy and rationality in The Bias that Divides us Itself. As I’ve already noted, the final chapter contains little of value. A big part of the problem is that Stanovich defers to sources like James Lindsay and Peter Boghossian; sources that those who have genuine expertise in his bêtes noires, like “critical race theory,” know to be extremely low quality. In so deferring, he goes badly wrong. But it certainly doesn’t follow he’s guilty of irrationality. He may well be deferring appropriately, given his own priors.

In so deferring, he goes badly wrong. But it certainly doesn’t follow he’s guilty of irrationality. He may well be deferring appropriately, given his own priors.

Myside Bias, Irrationality, and Academic Psychology

In this opinionated review, I’ve focused on Stanovich’s claim that myside bias is often irrational. I’ve ignored many of his other claims. One of his aims in the book is to demonstrate the academic psychology is often inadvertently biased against conservatives, because it suffers from the same flaw that many of the experimental studies that purport to demonstrate irrationality in participants exhibit: confounding prior beliefs with processing errors (see Tappin and Gadsby 2019 for a discussion of how pervasive this error is in psychological research on bias and irratonality). Just as participants may give the ‘wrong’ answer not because they fail appropriately to process the evidence given but because they regard it as unreliable, so conservatives may show more resistance to change (say) than liberals because the items selected for a scale are those that conservatives don’t want to change and liberals do. Change the selection of items and it is liberals who become change resistant. He is convincing in suggesting there is no strong evidence that conservatives exhibit more psychological bias than liberals. He is somewhat less convincing in arguing that conservatives show no more out-group dislike than liberals (he is surely right that to some extent the data is confounded by the groups toward which attitudes are measured), and less convincing again in arguing there’s no strong evidence of more racism on the conservative side. Still, his points here are valuable and ought to be taken on board both by psychologists and those who consume their work.

Change the selection of items and it is liberals who become change resistant. He is convincing in suggesting there is no strong evidence that conservatives exhibit more psychological bias than liberals. He is somewhat less convincing in arguing that conservatives show no more out-group dislike than liberals (he is surely right that to some extent the data is confounded by the groups toward which attitudes are measured), and less convincing again in arguing there’s no strong evidence of more racism on the conservative side. Still, his points here are valuable and ought to be taken on board both by psychologists and those who consume their work.

There is much of value in The Bias that Divides Us. Stanovich succeeds to a considerable degree in demonstrating bias against conservatives in psychological research. His defence of the irrationality of myside bias is to my mind less convincing, but it is one that deserves a serious hearing. It’s a pity that the book exhibits the very phenomenon it decries, at least in the form it manifests here. If I’m right, though, in deferring to such unreliable sources Stanovich nevertheless behaves rationally.

If I’m right, though, in deferring to such unreliable sources Stanovich nevertheless behaves rationally.

Author Information:

Neil Levy, [email protected], Macquarie University.

References

Abelson, Robert P., 1986. “Beliefs Are Like Possessions.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 16 (3): 223–250.

Begby, Endre. 2020. “Evidential Preemption.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 102 (3). https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12654

Christensen, David and Jennifer Lackey. 2013. The Epistemology of Disagreement: New Essays. Oxford University Press.

Chudek, Maciej, Sarah Heller, Susan Birch, Joseph Henrich 2012. “Prestige-Biased Cultural Learning: Bystander’s Differential Attention to Potential Models Influences Children’s Learning. Evolution and Human Behavior.” 33: 46–56.

Coady, David. 2006. “When Experts Disagree.” Episteme 3 (1-2): 68–79.

Douglas, Heather. 2000. “Inductive Risk and Values in Science.” Philosophy of Science 67 (4): 559–579.

Goldman, Alvin I., 2001. “Experts: Which Ones Should You Trust?” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 63 (1): 85–110.

Harris, Paul L. 2012. Trusting What You’re Told. Harvard University Press.

Henrich, Joseph, and Francisco J Gil-White. 2001. “The Evolution of Prestige: Freely Conferred Deference as a Mechanism for Enhancing the Benefits of Cultural Transmission.” Evolution and Human Behavior 22 (3): 165-196.

Levy, Neil. forthcoming. Bad Beliefs: Why They Happen to Good People. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Levy, Neil 2019. “Due Deference to Denialism: Explaining Ordinary People’s Rejection of Established Scientific Findings.” Synthese 196: 313–327.

Matheson, Jonathan. 2015. The Epistemic Significance of Disagreement. Palgrave Macmillan.

Sperber, Dan, Fabrice Clement, Christophe Heintz, Olivier Mascaro, Hugo Mercier, Gloria Origgi, and Deirdre Wilson. 2010. “Epistemic Vigilance.” Mind & Language 25 (4): 359–393.

2010. “Epistemic Vigilance.” Mind & Language 25 (4): 359–393.

Tappin, Ben M. and Stephen Gadsby. 2019. “Biased Belief in the Bayesian Brain: A Deeper Look at the Evidence.” Conscious Cogn 68: 107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2019.01.006.

‹ Towards a Knowledge Socialism: A Digital Sedition, Des Hewitt

Symposium in Honor of Joseph Agassi, Nov 17-18, 2021 ›

Categories: Books and Book Reviews

Tags: academic psychology, bias, credences, divergent beliefs, epistemic significance of disagreement, honest priors, irrationality, Keith E. Stanovich, myside bias, myside thinking, Neil Levy, prior beliefs, testable beliefs

"What was that?": how to deal with prejudice

"What was that?": how to deal with prejudice | Big Ideas CommunicationsArticle published in Harvard Business Review Russia Joseph Granny , Judith Onesti , David Maxfield

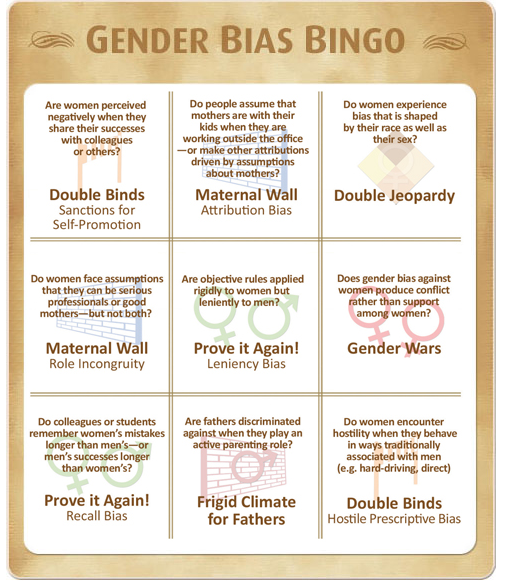

Prejudice in the office can be both overt and covert, causing shock and outrage in people. However, most often it becomes the cause of subtle signals, the essence of which fits into one phrase - “So, wait, what was that now?”. Let's give some examples. The client does not take you seriously because of your age. A potential customer only exchanges glances with your “white” colleague. A co-worker sees you as angry, and calls another co-worker who is as determined as you strong (women are much more likely to experience this attitude, according to one of four studies).

However, most often it becomes the cause of subtle signals, the essence of which fits into one phrase - “So, wait, what was that now?”. Let's give some examples. The client does not take you seriously because of your age. A potential customer only exchanges glances with your “white” colleague. A co-worker sees you as angry, and calls another co-worker who is as determined as you strong (women are much more likely to experience this attitude, according to one of four studies).

At such times, you begin to doubt other people's intentions and your own judgment. Your inner voice tells you: “It's a shame, of course, but is it worth it to be upset about this? And why all of a sudden? At best, such an attitude, the manifestation of which you will not immediately guess, will exhaust you, and at worst, poison your soul.

Due to its sometimes non-obvious nature, this phenomenon is quite difficult to eradicate in the workforce. Leaders set rules that prohibit discrimination against certain social groups. But what about prejudice that manifests itself randomly and unconsciously? Is it possible to legally prohibit speculation about the status of a person, exchange views or make erroneous conclusions?

But what about prejudice that manifests itself randomly and unconsciously? Is it possible to legally prohibit speculation about the status of a person, exchange views or make erroneous conclusions?

Clearly the corporate culture needs to change. However, until they come, the question remains: what should a person who daily faces barely noticeable manifestations of injustice do? Putting an additional burden of responsibility on the victims of prejudice would be wrong. If they are not armed with transition protection while the company changes its corporate culture, the current situation will only get worse.

We believe that in this case one should act in two directions - "cultivate the seed" and "cultivate the soil." The seed refers to a person who needs to learn how to resist prejudice, survive and thrive no matter what "soil" under his feet.

Soil is a company that has not completely outlived prejudice. It must be processed so that a wide variety of seeds can germinate in it.

Prejudice: what's the point?

This year we asked people who have experienced prejudice at work to give details about what happened to them. In two weeks, they sent us 498 full of bitter stories that will not leave anyone indifferent. In most cases, the manifestations of bias were undisguised. Let's give examples.

“One day I was having lunch with my comrades when two gay men walked by us. Some of my colleagues sneered contemptuously, expressing their distaste for them. As a gay man, I was extremely annoyed that these employees, brought up in an atmosphere of multiculturalism and tolerance, behaved rudely and unprofessionally. One of my colleagues, who was aware that I was gay, made a corresponding remark to them, but they ignored him and continued the conversation as if nothing had happened.

Sometimes people reported that their offenders, realizing they were wrong, tried to apologize, but usually it was too late.

“I am the only woman in a group of ten men. Being 11 weeks pregnant, I decided to report my situation to my boss. This news pissed him off. “Yes, so that I hire a woman at least once!” he blurted out. His reaction shocked me to the core. On Monday, the manager apologized to me for his comment, saying that he was just joking. I accepted them, while clearly understanding that these words were spoken by him seriously. Unfortunately, I couldn't stand up for myself."

Being 11 weeks pregnant, I decided to report my situation to my boss. This news pissed him off. “Yes, so that I hire a woman at least once!” he blurted out. His reaction shocked me to the core. On Monday, the manager apologized to me for his comment, saying that he was just joking. I accepted them, while clearly understanding that these words were spoken by him seriously. Unfortunately, I couldn't stand up for myself."

Paradoxically, the rarest examples describe the most common cases of unfair treatment, which is random and unconscious. The lack of such stories in our sample is probably due to the fact that the hidden behaviors underlying them are difficult to recognize, describe and stop.

“I'm the only woman on the software engineering team. Leading specialists, selecting candidates for work in new cool and breakthrough projects, as a rule, do not notice me. It seems to me that this is happening because I violate their male idyll.

The problem lies not only in the fact that people have to experience tendentiousness, but also in the fact that it is not customary to talk about such cases. Victims do not want to be blamed or attacked for "playing the card of multiculturalism" as this approach could negatively impact their careers. That's why they prefer not to stick out.

Victims do not want to be blamed or attacked for "playing the card of multiculturalism" as this approach could negatively impact their careers. That's why they prefer not to stick out.

We asked the respondents to answer us the following question: are such incidents at work permanent, all-encompassing and uncontrollable? It is by these three criteria that psychologist Martin Seligman assesses a person's helplessness, the hopelessness of the situation in which he finds himself, and even the severity of depression. The results were disappointing, but quite expected.

recommended reading

Jane Fonda: “I became an actress out of desperation”

Gabriel Joseph-Dezeyz

Why incompetent people occupy leadership positions

Josh Bersin, Thomas Chamorro-Premusic

Ferguson's Lessons on How to Win and Benefit from Failure

Alex Ferguson, Michael Moritz

When bureaucracy became a dirty word

William Starbuck

Sign in to read full article

We advise you to read

hidden signs of a failed project

Gretchen Gatele Gatett

Four signs of corporate lies

Ron Karucci

Five reasons, because of which the investments in the technology do not pay off the Thomas Comorro-Premurro

, how much should CEO

22Sarah Greene Carmichael

Confirmation bias: why we are never objective

November 22, 2021 Education

We are programmed to fit facts to our own theories.

People by their nature are prone to delusions, and sometimes to massive ones. Take homeopathy, for example: there is no scientific evidence that it works. But if one day a person coped with the disease using such means, he is irrevocably convinced that this is the merit of magic pills.

Now he ignores the arguments of scientists, and interprets the evidence of the futility of homeopathy in his own way: all medicine is bought, and such studies are ordered by competitors.

On the other hand, he will consider the stories of friends, acquaintances and colleagues who overcame the flu while taking dummy pills as confirmation of his theory. Because their arguments are “It helped me!” are consistent with his own ideas.

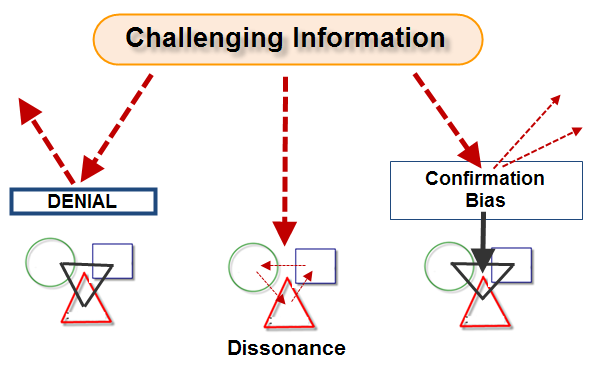

This is called confirmation bias.

What is confirmation bias

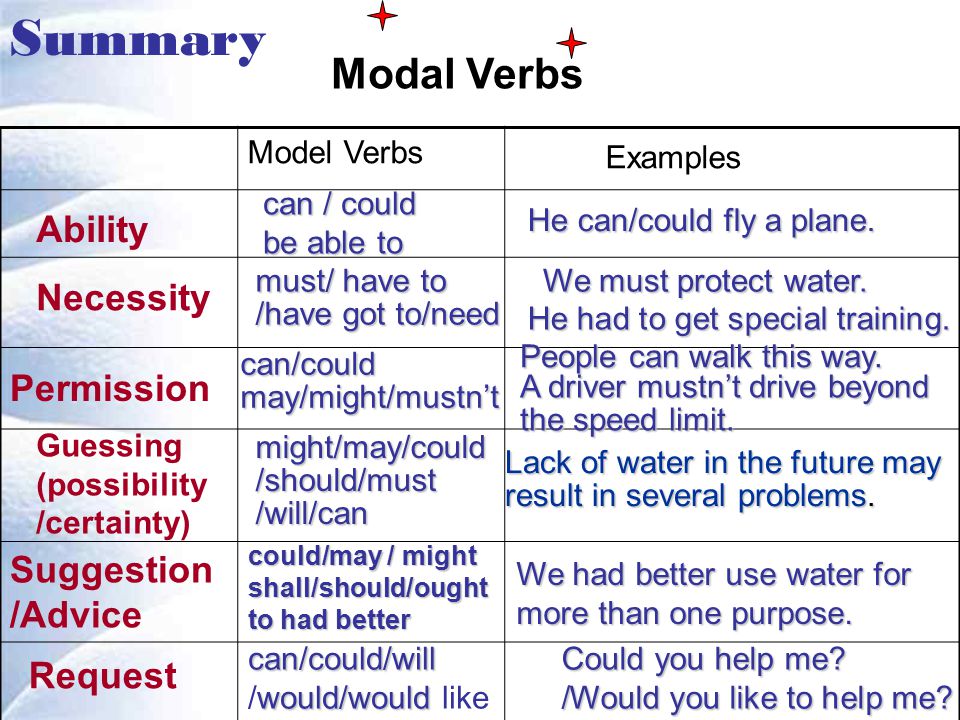

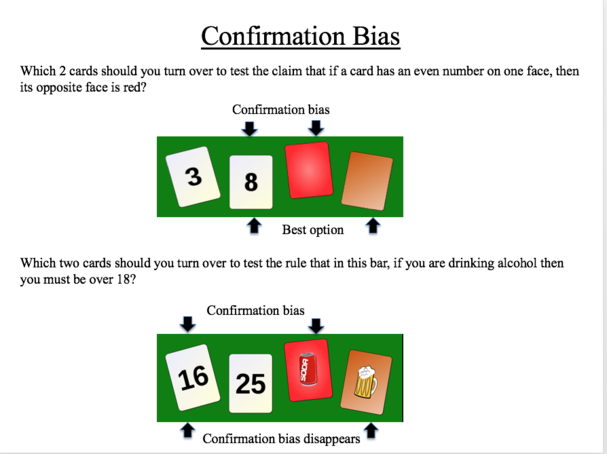

The scientific term "confirmation bias" was coined by cognitive psychologist Peter Cathcart Wason in the 1960s. He conducted a series of experiments that confirmed the existence of this vicious inclination of people. We are always looking for evidence of our point of view and ignore information that refutes it.

We are always looking for evidence of our point of view and ignore information that refutes it.

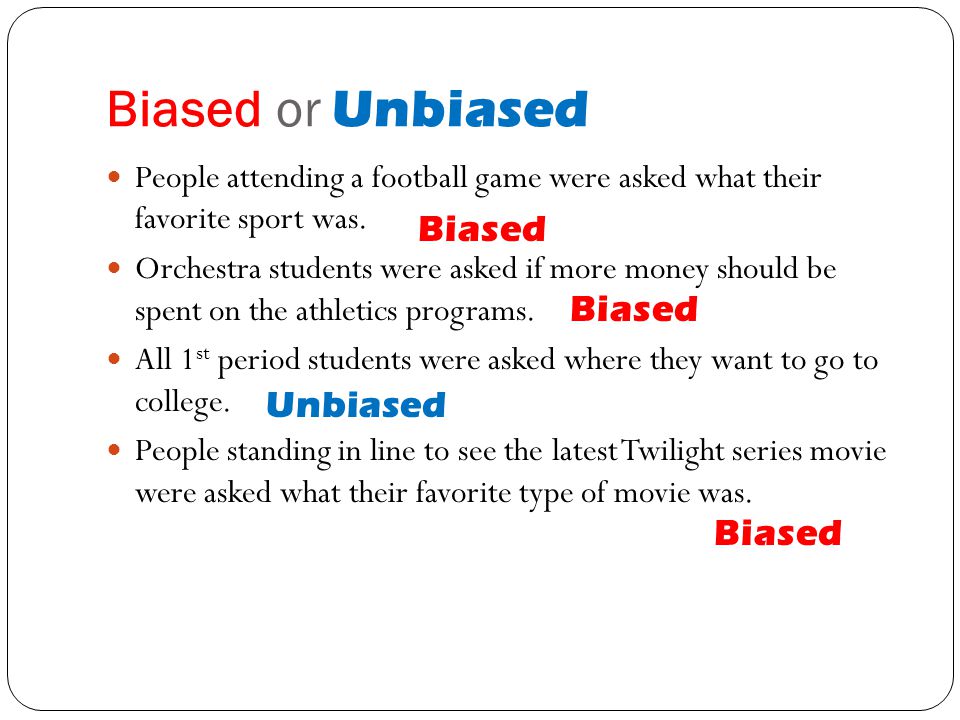

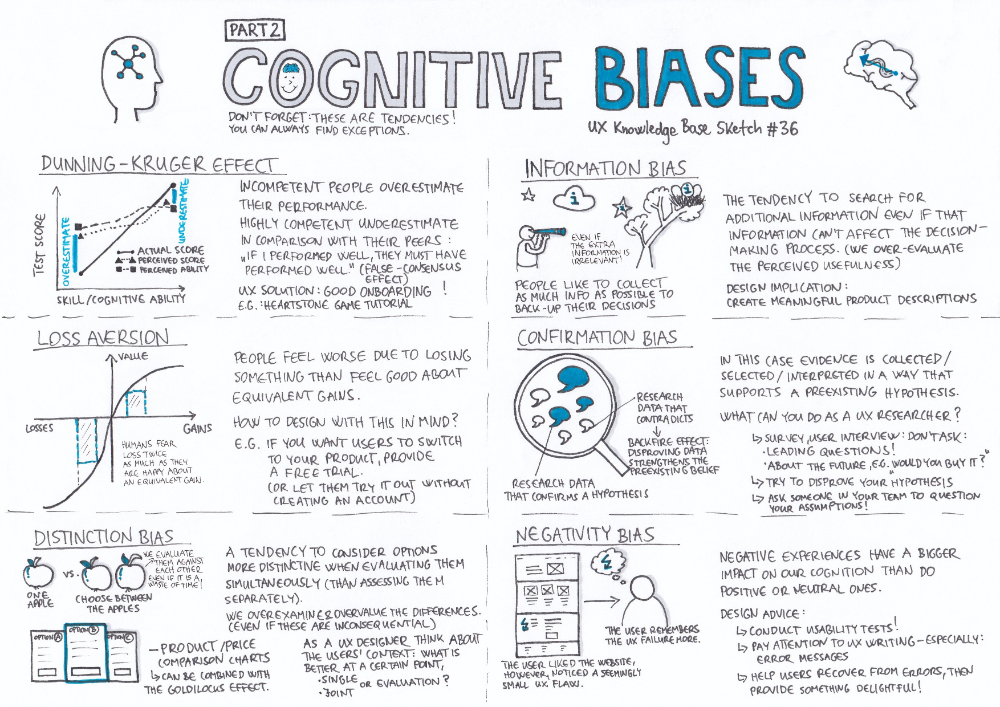

Confirmation bias consists of three mechanisms: information retrieval bias, interpretation bias, and memory bias. They can act individually or all together.

Biased search for information

Believing that we are right, we try to find confirmation of our idea, not its refutation. And in the end, we begin to see only what makes our theory true.

In one experiment, participants were introduced to characters who were to be interviewed. The subjects were told that some of the characters were introverts and some were extroverts.

As a result, for the interviewees, the participants chose only those questions that were supposed to confirm their tendency to introversion or extroversion. It never occurred to them to doubt her. For example, they asked supposedly introverts: “What do you dislike about parties?” And they didn't even give them the opportunity to refute this theory.

Similarly, a person who believes in homeopathy will only look for evidence of its benefits. He will begin by all means to avoid those people and that information that claims the opposite. Then he will find a group of like-minded people and will be interested only in the stories of people "who helped." Arguments against will remain out of his field of vision.

Biased interpretation

This distortion mechanism is based on the fact that everything heard and seen can be understood in two ways. A person usually tries to interpret new information in favor of what he is already convinced of.

This distortion was studied at Stanford University. A team of scientists conducted an experiment for which two groups of participants were invited. One of them was against the existence of the death penalty, and the other was for it. Each group was given two studies. The first of them confirmed their point of view, and the second - refuted.

As expected, participants rated the studies consistent with their beliefs as more convincing. They pointed out the details that matched their opinion and ignored the rest. The material that refuted their beliefs was criticized by the participants for insufficient data, a small sample, and the absence of strong arguments. In fact, all studies were fiction.

They pointed out the details that matched their opinion and ignored the rest. The material that refuted their beliefs was criticized by the participants for insufficient data, a small sample, and the absence of strong arguments. In fact, all studies were fiction.

Preconceived memories

In addition to incorrect processing of new information, we are also not very reliable in our memories. We extract from our consciousness only what is beneficial to us at the moment.

In another experiment, the researchers asked participants to read a description of one week in the life of a woman named Jane. It told what Jane did things. Some described her as an extrovert, while others described her as an introvert.

After that, the participants were divided into two groups. One of them was asked to evaluate whether Jane would be a good fit for a librarian position. The second was asked to determine her chances of becoming a realtor.

As a result, the participants in the first group remembered more of Jane's features that describe her as an introvert. And the “pro realtor” group characterized her mainly as an extrovert.

And the “pro realtor” group characterized her mainly as an extrovert.

Memories of Jane's behavior that do not correspond to the desired qualities, as if they did not exist.

How dangerous this trap of thinking is

All people like it when their desires coincide with reality. However, prejudice bias is bias and unreliability.

University of Illinois professor Dr. Shahram Heshmat says the consequences can be very bad.

The psyche and relationships with others suffer

If a person is not self-confident, anxious and suffers from low self-esteem, he can interpret any neutral reaction in his address negatively. He begins to feel that he is not loved or that the whole world is mocking him. He becomes either very sensitive, taking everything too personally, or aggressive.

Development and growth become impossible

Prejudice can result in real self-deception. A person sincerely believes that he is right in everything, ignores criticism and reacts only to praise. He simply does not need to learn new things and rethink something.

He simply does not need to learn new things and rethink something.

Health and finances are at risk

For example, if someone is convinced that marijuana does not harm his health in any way. Or that you can make money on sports predictions. Then the confirmation bias can literally ruin his life.

Dealing with confirmation bias

Don't be afraid of criticism

There's nothing wrong with it, as long as it's not rude or meant to offend you. Take it as advice or an idea, not as a personal insult. Listen to what most people think is wrong.

You may indeed be doing something wrong. This does not mean that you need to immediately change your behavior or thoughts. Rather, you should think about them. And remember that it is the results of your actions that are most often criticized, not yourself.

Do not avoid disputes

Truth is born in an argument, and this is the truth. If people agreed with each other in everything, it is unlikely that humanity would have made any progress. And if they did not agree - too.

And if they did not agree - too.

An argument is not a reason to humiliate or insult someone, but a way to get to the bottom of the truth. And this is far from a quarrel, but rather cooperation. It is only important to learn not only to speak, but also to listen.

Look at things from different angles

Do not rely only on your own vision. Try to look at the problem through the eyes of your friends, opponents, and even those who are not interested in it at all.

Don't ignore arguments that differ from yours and look closely at them - perhaps the truth lies there. Do not take any side until you have studied all the points.

Do not trust only one source

Watch different channels. Read different authors. Look at different books. The more divergent opinions you gather about a problem, the more likely it is that one of them will be correct.

And don't stop at allegations, but always look for scientific research.

Be curious

Curiosity makes you ask questions and seek answers.