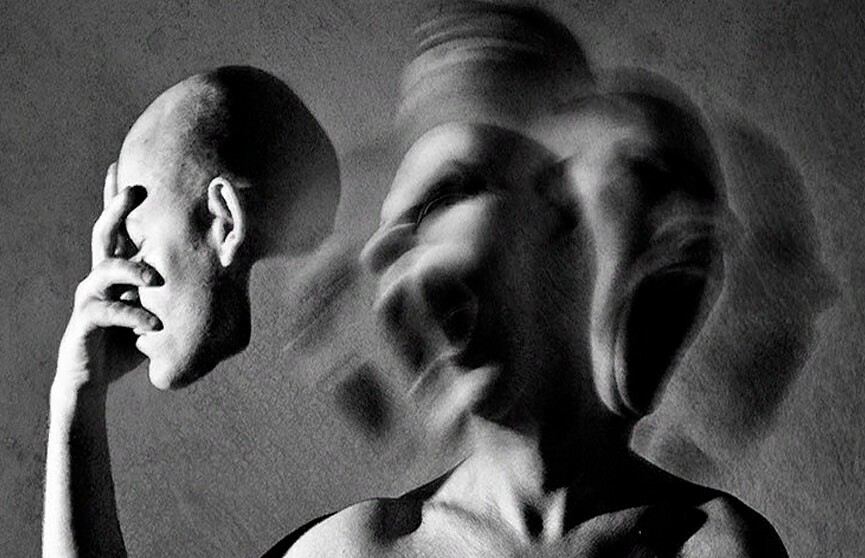

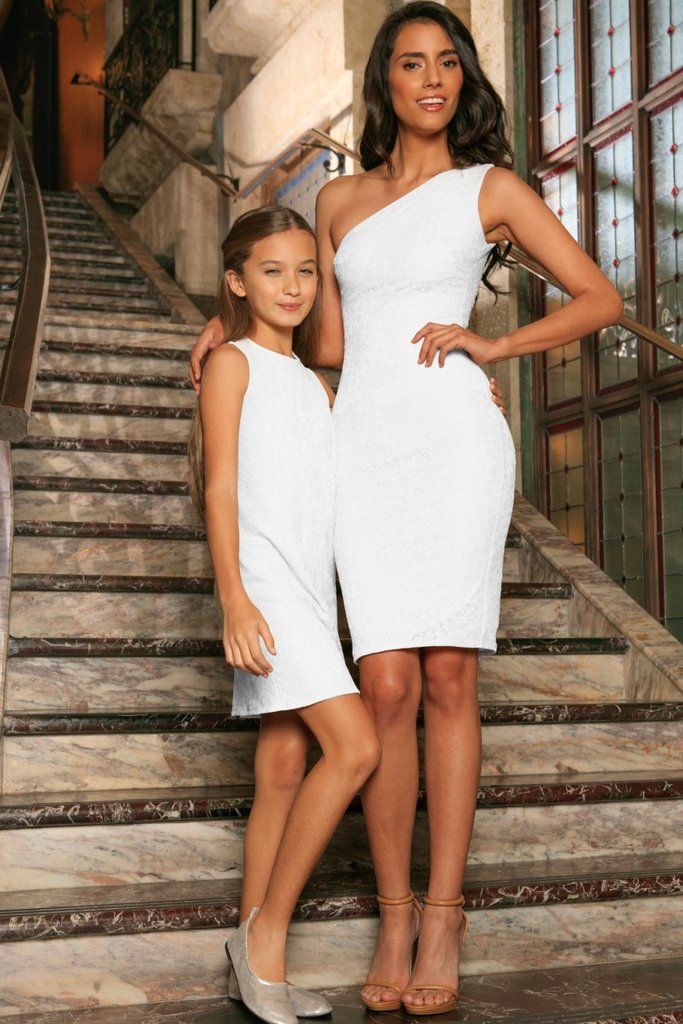

Mother daughter codependency

Parent Codependency: Recognizing the Signs

You may be familiar with the idea of codependency from the world of alcohol and chemical misuse. In fact, that’s where the term “codependency” was born.

Today, though, the term has broadened to include relationships. It’s sometimes connected with other kinds of codependency.

For example, a 2009 study of 171 adult females suggested that parental alcohol misuse or history of childhood abuse may make relationship-based codependency — such as the parent-child variety — more likely to happen.

But it can also occur all on its own. Here’s what you need to know about being a codependent parent — and how it puts your children at risk.

A codependent parent is one who has an unhealthy attachment to their child and tries to exert excess control over the child’s life because of that attachment.

Codependency can be found in the full range of parental relationships: A codependent father may rely on his daughter or son to keep him mentally stable and emotionally happy. A codependent mother may rely on her son or daughter to take responsibility for her physical well-being.

While codependent parents may claim that the close relationship they covet is a sign of a well-functioning family, their preoccupation with each other is a sign of dysfunction.

It’s important to realize that codependency isn’t easy to spot, according to a 2014 research article. Biological, psychological, and social elements can all contribute to codependency.

If you think you may be a codependent parent, here are some signs to look out for.

In a codependent relationship, your sense of self depends on your relationship with your child.

Codependent relationships feed on a cycle of neediness: One person needs the other. Sometimes, but not always, it works both ways and the other person wants to be needed too.

Parents who are codependent may try to control their child’s life. This control can show up in different ways:

- Over-involvement.

For example, if a parent sees that something painful is happening in their child’s life, they’ll try to gain control by getting involved — often too involved. That’s because the child’s pain is the parent’s pain. (This is, of course, true for all parents… within reason. We don’t like to see our kids hurting. It’s when it’s taken to the extreme that it crosses the line into codependency.)

For example, if a parent sees that something painful is happening in their child’s life, they’ll try to gain control by getting involved — often too involved. That’s because the child’s pain is the parent’s pain. (This is, of course, true for all parents… within reason. We don’t like to see our kids hurting. It’s when it’s taken to the extreme that it crosses the line into codependency.) - Inappropriate caretaking. Codependent parents will do more for their child than what is age-appropriate. For example, an 8-year-old child should be choosing their clothes to wear each morning on their own. A 16-year-old should be managing their own class schedule and homework.

- Incorrect shouldering of responsibility. Codependent parents often feel responsible for their child’s feelings and take the blame for their child’s mood swings.

Do you believe that you need to be available 24/7 for your child? If you’re a codependent parent, the first relationship that’ll likely suffer is your relationship with your partner.

Instead of investing time and energy into building a meaningful romantic relationship, you may choose to focus solely on your child. As time goes on, you may find that your sexual relationship with your partner has stagnated.

You may also find that you’re isolating yourself from your family members and friends. You’re prepared to cancel a coffee date with your BFF because your child insists that you need to take them shopping for soccer shoes.

Codependent parents may unknowingly (or knowingly but not maliciously) use many psychological strategies to get their child to do what they want:

- Passive-aggressive behavior. This is when a parent is being indirectly aggressive toward their child.

- Projection. This happens when a parent can’t handle their feelings or believes that the feelings are unacceptable. Unable to work through the feelings, the parent projects them onto their child. In this way, the parent avoids feelings of guilt, shame, or regret.

- Generating guilt. This occurs when a parent attempts to make their child feel guilty about something to pressure them into behaving how they want them to behave. An example is when a parent complains their child rarely talks about what happened at school. Remaining the victim, the parent may then say that a daily summary isn’t necessary. Often, feeling guilty, the child will reassure the parent that this isn’t a big deal and that they really want to do it. The result? The parent gets the play-by-play without having to feel guilty about it because the child reassured them it wasn’t a big deal.

Do you believe that, no matter what, you’re always right? Do you feel attacked if someone questions what you’re doing?

Codependent parents often won’t accept that they’ve done something wrong. This is because any sign of disagreement is a show of rebellion. It threatens the parent’s authority and sense of control.

We all like to share our childhood memories with our children. When done in a positive way, we can teach our children important coping skills.

When done in a positive way, we can teach our children important coping skills.

For example, when you reminisce about how you drove over your neighbor’s geranium pots and then tell your child that you knocked on the neighbor’s door to offer to replace them, you’re teaching your child an important lesson about responsibility.

However, if you frame it as your neighbor making you feel ashamed and careless for years after that — despite your new driver status at the time — you may be unconsciously trying to garner sympathy from your child.

Codependent parents rely on their children to give to them, instead of giving to their children. This is known as parentification.

By continually showing your child that you were a victim, you’re relying on them to give you the emotional support you need.

Codependent parents may have a hard time disciplining their children.

Fearful that their child will reject them, they choose to let them break the boundaries they’ve set up. In these cases, the parent prefers to endure disrespect rather than risk trying to enforce boundaries and making their child angry.

In these cases, the parent prefers to endure disrespect rather than risk trying to enforce boundaries and making their child angry.

In some cases, a parent may even resent it when their partner asks the child to follow the rules. For example, Dad may get angry with Mom for trying to enforce a bedtime curfew even though their child should have been in bed a good few hours earlier.

Codependent parents often have low self-esteem. Their self-esteem is dependent on their child: If their child is happy with them, they’re happy about themselves. And if their child is troubled, they’re troubled.

While it’s totally normal for a parent to have hopes and dreams for their child, codependent parents take things a step further: They expect their child to live the life and achieve the goals that they themselves fell short of.

If you immediately see red when someone suggests that you may be a codependent parent, there’s a good possibility that they’re onto something. Why is that? Denial is a defense mechanism that protects you from painful or threatening thoughts, feelings, and information.

If your relationship with your child is on track, you’re not as likely to feel threatened by someone suggesting that something is wrong.

The saddest part about denial is that it will stop you reaching out for help. And as we’re about to see, it’s important to get help.

Parent-child codependency can be emotionally abusive. The child learns that their feelings and needs are unimportant and never has the chance to develop their own personality.

An adolescent’s sense of identity is built through the choices and commitments that they make. When a codependent parent stifles the child’s ability to commit to their chosen beliefs and values, the adolescent remains with a diffused identity and never forms their own.

In addition, because parents are a child’s role models, children naturally pick up on their parents’ behaviors. This includes codependency. A child who has been controlled is more likely to become a controlling parent.

The first step in stopping codependency is to admit that it’s present.

When parents have emptied the family emotional bank account with codependent behaviors, they’ll need to be especially respectful and sensitive to their child. Especially when the child starts to express the pent-up anger that has collected.

Here are some tips to get you started.

- Practice self-care. Instead of relying on your child to take care of your needs, take steps to fulfill your own needs. As you learn to give to yourself, you’ll be able to give to your child.

- Step back. Allow your child the independence to solve age-appropriate challenges. This will give them the self-confidence to trust themselves and stretch further.

- Listen actively. Give your child your full attention when they talk to you. Reflect back what you heard. Then ask them if you heard what they wanted to say.

Where do codependent parents turn to when reaching out for help? The best practice is to dedicate time for counseling sessions with a licensed therapist who’s experienced in codependency or addiction.

But for a variety of reasons, that’s not always possible. You may also find online support groups, books, or organizations that offer helpful resources.

Be patient with yourself when you make the decision to move on to better parenting. You’re on a learning curve. Allow yourself to have some bad days, but keep moving forward.

Parent Codependency: Recognizing the Signs

You may be familiar with the idea of codependency from the world of alcohol and chemical misuse. In fact, that’s where the term “codependency” was born.

Today, though, the term has broadened to include relationships. It’s sometimes connected with other kinds of codependency.

For example, a 2009 study of 171 adult females suggested that parental alcohol misuse or history of childhood abuse may make relationship-based codependency — such as the parent-child variety — more likely to happen.

But it can also occur all on its own. Here’s what you need to know about being a codependent parent — and how it puts your children at risk.

A codependent parent is one who has an unhealthy attachment to their child and tries to exert excess control over the child’s life because of that attachment.

Codependency can be found in the full range of parental relationships: A codependent father may rely on his daughter or son to keep him mentally stable and emotionally happy. A codependent mother may rely on her son or daughter to take responsibility for her physical well-being.

While codependent parents may claim that the close relationship they covet is a sign of a well-functioning family, their preoccupation with each other is a sign of dysfunction.

It’s important to realize that codependency isn’t easy to spot, according to a 2014 research article. Biological, psychological, and social elements can all contribute to codependency.

If you think you may be a codependent parent, here are some signs to look out for.

In a codependent relationship, your sense of self depends on your relationship with your child.

Codependent relationships feed on a cycle of neediness: One person needs the other. Sometimes, but not always, it works both ways and the other person wants to be needed too.

Parents who are codependent may try to control their child’s life. This control can show up in different ways:

- Over-involvement. For example, if a parent sees that something painful is happening in their child’s life, they’ll try to gain control by getting involved — often too involved. That’s because the child’s pain is the parent’s pain. (This is, of course, true for all parents… within reason. We don’t like to see our kids hurting. It’s when it’s taken to the extreme that it crosses the line into codependency.)

- Inappropriate caretaking. Codependent parents will do more for their child than what is age-appropriate. For example, an 8-year-old child should be choosing their clothes to wear each morning on their own. A 16-year-old should be managing their own class schedule and homework.

- Incorrect shouldering of responsibility. Codependent parents often feel responsible for their child’s feelings and take the blame for their child’s mood swings.

Do you believe that you need to be available 24/7 for your child? If you’re a codependent parent, the first relationship that’ll likely suffer is your relationship with your partner.

Instead of investing time and energy into building a meaningful romantic relationship, you may choose to focus solely on your child. As time goes on, you may find that your sexual relationship with your partner has stagnated.

You may also find that you’re isolating yourself from your family members and friends. You’re prepared to cancel a coffee date with your BFF because your child insists that you need to take them shopping for soccer shoes.

Codependent parents may unknowingly (or knowingly but not maliciously) use many psychological strategies to get their child to do what they want:

- Passive-aggressive behavior.

This is when a parent is being indirectly aggressive toward their child.

This is when a parent is being indirectly aggressive toward their child. - Projection. This happens when a parent can’t handle their feelings or believes that the feelings are unacceptable. Unable to work through the feelings, the parent projects them onto their child. In this way, the parent avoids feelings of guilt, shame, or regret.

- Generating guilt. This occurs when a parent attempts to make their child feel guilty about something to pressure them into behaving how they want them to behave. An example is when a parent complains their child rarely talks about what happened at school. Remaining the victim, the parent may then say that a daily summary isn’t necessary. Often, feeling guilty, the child will reassure the parent that this isn’t a big deal and that they really want to do it. The result? The parent gets the play-by-play without having to feel guilty about it because the child reassured them it wasn’t a big deal.

Do you believe that, no matter what, you’re always right? Do you feel attacked if someone questions what you’re doing?

Codependent parents often won’t accept that they’ve done something wrong. This is because any sign of disagreement is a show of rebellion. It threatens the parent’s authority and sense of control.

This is because any sign of disagreement is a show of rebellion. It threatens the parent’s authority and sense of control.

We all like to share our childhood memories with our children. When done in a positive way, we can teach our children important coping skills.

For example, when you reminisce about how you drove over your neighbor’s geranium pots and then tell your child that you knocked on the neighbor’s door to offer to replace them, you’re teaching your child an important lesson about responsibility.

However, if you frame it as your neighbor making you feel ashamed and careless for years after that — despite your new driver status at the time — you may be unconsciously trying to garner sympathy from your child.

Codependent parents rely on their children to give to them, instead of giving to their children. This is known as parentification.

By continually showing your child that you were a victim, you’re relying on them to give you the emotional support you need.

Codependent parents may have a hard time disciplining their children.

Fearful that their child will reject them, they choose to let them break the boundaries they’ve set up. In these cases, the parent prefers to endure disrespect rather than risk trying to enforce boundaries and making their child angry.

In some cases, a parent may even resent it when their partner asks the child to follow the rules. For example, Dad may get angry with Mom for trying to enforce a bedtime curfew even though their child should have been in bed a good few hours earlier.

Codependent parents often have low self-esteem. Their self-esteem is dependent on their child: If their child is happy with them, they’re happy about themselves. And if their child is troubled, they’re troubled.

While it’s totally normal for a parent to have hopes and dreams for their child, codependent parents take things a step further: They expect their child to live the life and achieve the goals that they themselves fell short of.

If you immediately see red when someone suggests that you may be a codependent parent, there’s a good possibility that they’re onto something. Why is that? Denial is a defense mechanism that protects you from painful or threatening thoughts, feelings, and information.

If your relationship with your child is on track, you’re not as likely to feel threatened by someone suggesting that something is wrong.

The saddest part about denial is that it will stop you reaching out for help. And as we’re about to see, it’s important to get help.

Parent-child codependency can be emotionally abusive. The child learns that their feelings and needs are unimportant and never has the chance to develop their own personality.

An adolescent’s sense of identity is built through the choices and commitments that they make. When a codependent parent stifles the child’s ability to commit to their chosen beliefs and values, the adolescent remains with a diffused identity and never forms their own.

In addition, because parents are a child’s role models, children naturally pick up on their parents’ behaviors. This includes codependency. A child who has been controlled is more likely to become a controlling parent.

The first step in stopping codependency is to admit that it’s present.

When parents have emptied the family emotional bank account with codependent behaviors, they’ll need to be especially respectful and sensitive to their child. Especially when the child starts to express the pent-up anger that has collected.

Here are some tips to get you started.

- Practice self-care. Instead of relying on your child to take care of your needs, take steps to fulfill your own needs. As you learn to give to yourself, you’ll be able to give to your child.

- Step back. Allow your child the independence to solve age-appropriate challenges. This will give them the self-confidence to trust themselves and stretch further.

- Listen actively. Give your child your full attention when they talk to you. Reflect back what you heard. Then ask them if you heard what they wanted to say.

Where do codependent parents turn to when reaching out for help? The best practice is to dedicate time for counseling sessions with a licensed therapist who’s experienced in codependency or addiction.

But for a variety of reasons, that’s not always possible. You may also find online support groups, books, or organizations that offer helpful resources.

Be patient with yourself when you make the decision to move on to better parenting. You’re on a learning curve. Allow yourself to have some bad days, but keep moving forward.

When the relationship between mother and daughter is like madness

Special relationship

Someone idealizes his mother, and someone admits that he hates her and cannot find a common language with her. Why is this such a special relationship, why do they hurt us so much and cause such different reactions?

A mother is not just an important character in a child's life. According to psychoanalysis, almost the entire human psyche is formed in the early relationship with the mother. They are not comparable to any others.

According to psychoanalysis, almost the entire human psyche is formed in the early relationship with the mother. They are not comparable to any others.

The mother for the child, according to psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, is actually the environment in which it is formed. And when relationships do not develop in the way that would be useful for this child, his development is distorted.

In practice, the relationship with the mother determines everything in a person's life. This places a great responsibility on a woman, because a mother never becomes a person for her adult child with whom he can build equal trusting relationships. The mother remains an incomparable figure in his life with nothing and no one.

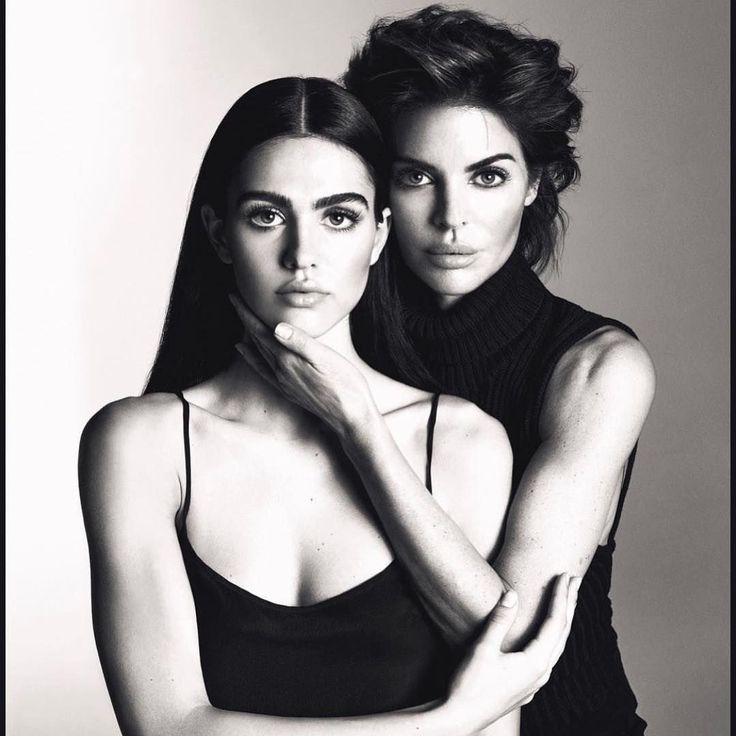

What does a healthy relationship between mother and adult daughter look like?

This is a relationship in which adult women can communicate and negotiate with each other, live a separate life - each of her own. They can be angry with each other and disagree, dissatisfied with something, but at the same time aggression does not destroy love and respect, and no one takes away their children and grandchildren from anyone.

But the daughter-mother relationship is the most complex of the four possible combinations (father-son, father-daughter, mother-son, and mother-daughter). The fact is that the mother for the daughter is the primary object of affection. But then, at the age of 3–5 years, she needs to transfer her libidinal feelings to her father, and she begins to fantasize: “When I grow up, I will marry my father.”

This is the same oedipal complex that Freud discovered, and it is strange that no one before him did this, because the attraction of the child to the parent of the opposite sex was noticeable at all times.

And it is very difficult for a girl to go through this obligatory stage of development. After all, when you start to love dad, mom becomes a rival, and both of you somehow need to share dad's love. It is very difficult for a girl to compete with her mother, who is still loved and important to her. And the mother, in turn, is often jealous of her husband for her daughter.

But this is only one line. There is also a second one. For a little girl, her mother is an object of affection, but then she needs to identify with her mother in order to grow and become a woman.

There is some contradiction here: the girl has to simultaneously love her mother, fight her for her father's attention and identify with her. And here a new difficulty arises. The fact is that mother and daughter are very similar, and it is very easy for them to identify with each other. It is easy for a girl to mix her own and her mother's, and it is easy for a mother to see her continuation in her daughter.

Many women really have a hard time distinguishing themselves from their daughters. It's like psychosis. If you ask them directly, they will object and say that they distinguish everything perfectly and do everything for the good of their daughters. But at some deep level, this boundary is blurred.

Is taking care of your daughter also taking care of yourself?

Through her daughter, the mother wants to realize what she has not realized in life. Or something that she herself loves very much. She sincerely believes that her daughter should love what she loves, that she will like to do what she herself does. Moreover, the mother simply does not distinguish between her own and her needs, desires, feelings.

Or something that she herself loves very much. She sincerely believes that her daughter should love what she loves, that she will like to do what she herself does. Moreover, the mother simply does not distinguish between her own and her needs, desires, feelings.

Do you know jokes like “put on a hat, I'm cold”? She really feels for her daughter. I remember an interview with artist Yuri Kuklachev, who was asked: “How did you raise your children?” He says: “And this is the same as with cats.

No tricks can be taught to a cat. I can only notice what she is inclined to, what she likes. One is jumping, the other is playing with a ball. And I develop this tendency. Likewise with children. I just looked at what they are, what they naturally come out with. And then I developed them in this direction.

This is the sensible approach when a child is viewed as a separate being with its own personality traits.

And how many mothers do we know who seem to take care: they take their children to circles, exhibitions, concerts of classical music, because, according to their deep feeling, this is exactly what the child needs. And then they also blackmail them with phrases like: “I put my whole life on you,” which cause an enormous feeling of guilt in adult children. Again, this looks like psychosis.

And then they also blackmail them with phrases like: “I put my whole life on you,” which cause an enormous feeling of guilt in adult children. Again, this looks like psychosis.

In essence, psychosis is the inability to distinguish between what is happening inside you and what is outside. The mother is outside the daughter. And the daughter is outside of her. But when a mother believes that her daughter likes what she likes, she begins to lose this boundary between the inner and outer world. And the same thing happens to my daughter.

They are the same sex, they are really very similar. This is where the theme of shared insanity comes in, a kind of mutual psychosis that only extends to their relationship. If you do not observe them together, you may not notice any violations at all. Their interaction with other people will be quite normal. Although some distortions are possible. For example, this daughter with women of the maternal type - with bosses, female teachers.

What is the cause of this psychosis?

Here it is necessary to recall the figure of the father. One of his functions in the family is to stand between mother and daughter at some point. This is how a triangle appears, in which there is a relationship between the daughter and the mother, and the daughter with the father, and the mother with the father.

One of his functions in the family is to stand between mother and daughter at some point. This is how a triangle appears, in which there is a relationship between the daughter and the mother, and the daughter with the father, and the mother with the father.

But very often a mother tries to make sure that her daughter's communication with her father goes through her. The triangle collapses.

I have met families where this model is reproduced for several generations: there are only mothers and daughters, and the fathers are removed, or they are divorced, or they never existed, or they are alcoholics and have no weight in the family. Who in this case will destroy their closeness and merging? Who will help them separate and look somewhere else but at each other and "mirror" their madness?

By the way, did you know that in almost all cases of Alzheimer's or some other type of dementia, mothers call their daughters "moms"? In fact, in such a symbiotic relationship, there is no distinction between who is related to whom. Everything merges.

Everything merges.

Should a daughter be "daddy's"?

Do you know what people say? In order for the child to be happy, the girl must be like her father, and the boy must be like her mother. And there is a saying that fathers always want sons, but love more than daughters. This folk wisdom fully corresponds to the psychic relations prepared by nature. I think that it is especially difficult for a girl who grows up as a "mother's daughter" to separate from her mother.

The girl grows up, enters childbearing age and finds herself, as it were, in the field of adult women, thereby pushing her mother into the field of old women. This is not necessarily happening at the moment, but the essence of the change is there. And many mothers, without realizing it, experience it very painfully. Which, by the way, is reflected in folk tales about an evil stepmother and a young stepdaughter.

Indeed, it is difficult to bear that a girl, a daughter, is flourishing, and you are getting old. A teenage daughter has her own tasks: she needs to separate from her parents. In theory, the libido that awakens in her after a latent period of 12–13 years should be turned from the family outward, to her peers. And the child during this period should leave the family.

A teenage daughter has her own tasks: she needs to separate from her parents. In theory, the libido that awakens in her after a latent period of 12–13 years should be turned from the family outward, to her peers. And the child during this period should leave the family.

If a girl's bond with her mother is very close, it is difficult for her to break free. And she remains a "home girl", which is perceived as a good sign: a calm, obedient child has grown up. In order to separate, to overcome attraction in such a situation of merger, the girl must have a lot of protest and aggression, which is perceived as rebellion and depravity.

It is impossible to realize everything, but if a mother understands these peculiarities and nuances of relationships, it will be easier for them. I was once asked such a radical question: “Is a daughter obliged to love her mother?” In fact, a daughter cannot help but love her mother. But in close relationships there is always love and aggression, and in the mother-daughter relationship of this love there is a sea and a sea of aggression. The only question is what will win - love or hate?

Always want to believe that love. We all know such families where everyone treats each other with respect, everyone sees in the other a person, an individual, and at the same time feels how dear and close he is.

dependent mother and dependent daughter, Psychology - Gestalt Club

Emotional dependence: dependent mother and dependent daughter

- Author of the article: Tatyana Linnik

Tatyana Linnik

Psychology - August 16, 2019at 20:13

Emotional dependence: dependent mother and dependent daughter.

Let's continue the theme of the relationship between mother and child,

today about the emotional mutual dependence of mother and daughters.

I am now talking about the time when I was already an adult daughter, say, 20+ years old.

Which of them is emotionally dependent and does not allow the other to live?

There are two in the situation: a daughter and a mother, respectively, are possible different options between them dependency and independence:

- dependent mother - independent daughter,

- dependent daughter and independent mother.

The most difficult situation of unhealthy relationships,

when the mother is dependent on the daughter and the daughter is dependent on the mother.

Today I will tell you exactly about such a case, when it was not possible to complete to separate

neither daughter from mother, nor mother from daughter.

Again, I'm talking about a situation where the daughter is an adult 20+.

**And then the mother, with varying degrees of annoyance, will get into business daughters, advise, insist that they do as she tells, make decisions for your daughter.

**Can criticize and evaluate her man (if her daughter has one). She can even choose and recommend a man in her own way choice.

She can even choose and recommend a man in her own way choice.

**Perhaps the mother will buy things without the consent of her daughter, in a variety of ways to return it to a state dependent on her child.

Mom cannot accept her adult daughter ADULT,

cannot let go of herself, from her care, cannot DO NOT control and DO NOT take care of her, CANNOT!

Mom is emotionally dependent on her daughter, she can’t break away on her own maybe.

She plans her future with her daughter, plans to live with her and spend time with her.

She has few or no girlfriends of her own.

At the same time, the daughter may also be insufficiently separated from mother.

And with all the desire for independence - does not find in himself strong enough to get away from mom.

She can live separately and in another city, but call her mother several times a day, talking for several hours, with her and just consult with her and resolve all issues.

Often a mother is her daughter's only friend, and her daughter's mothers.

There are often reproaches, depreciation, guilt and resentment between them, criticism, dissatisfaction with each other in a very different form.

And the daughter, despite her apparent adulthood, fully claims her mother and keeps long grievances from the past, that she gave something wrong and gave something wrong in upbringing and growing up, didn’t say so, etc.

They are unable to build adult partnerships, communicate in measure,

at the level of You are an adult and I am an adult, and we are equal with each other friend.

You can see the inequality: there is more in the life of the mother's daughter than her life.

And in the life of a mother, the life of a daughter is greater than her life.

They are busy with each other's lives, not their own.

The daughter can also quite filter the suitors of the mother and her friends.